Abstract

Research on natural fiber composites often prioritizes fiber composition over manufacturing parameters, leaving a gap in optimizing the compression molding process critical for interfacial adhesion and mechanical performance in hybrid composites. This study addresses this by applying a Grey-Fuzzy Logic approach to optimize the compression molding parameters for kenaf/Jute hybrid composites, a material chosen for its complementary strength and sustainability yet challenged by hydrophilicity and poor fiber-matrix bonding. An L16 Taguchi design was used, varying Kenaf fiber (10–25 wt%), Jute fiber (10–25 wt%), NaOH treatment (0–8 wt%), molding pressure (10–16 MPa), and temperature (100–120 °C). The results identified a singular optimal parameter set (20 wt% kenaf (KF), 25 wt% jute, 5 wt% NaOH, 10 MPa molding pressure, and a temperature of 120 °C), achieving a Grey-Fuzzy Grade of 0.888 and yielding maximum mechanical properties (48.8 MPa tensile, 90.1 MPa flexural, 33.7kJ/m2 impact). Crucially, ANOVA revealed molding pressure as the second-most significant factor (29.47% contribution), a novel finding underscoring that process parameters are as vital as fiber selection. This research uniquely demonstrates that superior hybrid composite performance is not attained through fiber treatment alone but requires the synergistic optimization of material and process parameters. The validated Grey-Fuzzy model provides a robust framework for manufacturing high-performance, sustainable composites for automotive and structural applications. Material characterization further confirmed that the 5% NaOH treatment effectively removed non-cellulosic components (Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy) (FTIR); increased crystallinity by 12% (X-Ray Diffraction); enhanced thermal stability, raising the maximum degradation temperature by 5 °C (Thermogravimetric Analysis).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing emphasis on renewable resources has driven significant interest in developing polymer composites using natural-based reinforcements (NFRCs) as viable substitutes for synthetic counterparts. While traditional synthetic reinforcements offer higher performance, their non-renewable nature and poor biodegradability pose considerable environmental challenges1. In this context, NFRCs exhibit superior characteristics such as a high strength-to-weight ratio, renewability, and biodegradability, making them attractive for automotive and structural applications.

Recent advances have focused on enhancing the properties and expanding the repertoire of natural fibers. Research has progressed from common fiber like jute and kenaf to exploring novel sources, demonstrating the continuous innovation in this filed. For instance, new such as C. humilis palm trunk2, Chamaerops humilis rachis3, Syagrus romanzoffiana4, Vicia faba plant waste stems5, Strelitzia Juncea6, Dracaena draco plant7, Strelitzia Juncea Plant Fibers8, Syagrus romanzoffiana, Agave plant9, have characterized, showing promising potential reinforcement in bio composites. Furthermore, treatment and hybridization are being refined to enhance performance, as evidenced by studies on the role biofiber in bio composites10,11,12, in their interfacial mechanics13, and their thermal and chemical properties.

Despite these advancements, inherent challenges persist. The hydrophilic nature of natural fibers leads to compatibility issues with hydrophobic polymer matrices, resulting in poor interfacial adhesion, which diminishes mechanical properties and moisture absorption. To address this, researchers have employed chemical treatments, fiber hybridization, notably alkalization with NaOH, have proven highly effective.

Vinod et al.14 investigated the influence of chemically treating jute/hemp epoxy hybrid natural composites on the mechanical characteristics. The addition of 5 wt% NaOH to jute increased yield strength and bending strength by 14.15% and 37.94%, respectively. Similarly, Muthalagu et al.15 produced a hybrid green composite, consisting of kenaf and jute reinforced epoxy hybrid composite, and investigated their mechanical and thermal properties. Based on their investigation, the addition of kenaf fiber into the composite shows excellent tensile, flexural, and impact strength. In a similar way, Rashid et al.16 in their study recommended that treated bamboo/Olive hybrid composites with 5% NaOH exhibited exceptional mechanical characteristics. Likewise, Khan et al.17 examined the effect of chemical treatment on tensile flexural and impact strength of Kenaf/Jute hybrid composite. It was observed that higher aspect ratio of kenaf and jute showed the superior in tensile, flexural and impact strength. Ghori et al.18, demonstrated that optimum process parameters 5% NaOH, the tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and interfacial sheer strength of the date palm fibre and kenaf fibre are better than the untreated fibers.

Major findings show that treatment around 5 wt% NaOH significantly enhance interfacial adhesion by removing non-cellulosic components, leading to marked improvements in tensile, flexural and impact strength. Furthermore, hybridizing two or more natural fiber can create a synergistic effect, balancing the performance characteristics of individual fibers to achieve superior overall properties19.

For manufacturing these composites, compression molding is preferred technique due to its suitability for mass production, high reproducibility and ability to produce composites with excellent surface finish18,20. The quality of the final product is profoundly influenced by critical process parameters such as molding temperature, pressure and time17,21. In this regard, Rangaswamy et al.22 adopted compression molding technique for fabrication of glass/Kevlar/epoxy filled MWCNT hybrid composites. They investigated the effect of molding parameters on the mechanical and tribological properties of the hybrid composite by varying the processing parameters. The mechanical properties are primary governed by molding parameters like pressure, temperature, and time, with pressure, which deciding the quality and strength of resulted composite. It was discovered that appropriate handling of these parameters enhanced mechanical properties. Manalu et al.23 investigated the effective process parameters (pressure, temperature, time) on the mechanical and thermal characteristics of composites during compressed molding process. The findings of enhanced mechanical and thermal characteristics of composite for automotive structural applications. Maji et al.24examined the quality of the composite by considering the different factors such as resin shrinkage, warpages of fibers, initial vacuuming duration, gelation, infusion pressure, and compaction pressure. Additionally, employing a low-viscosity matrix was discovered to enhance the surface wetting of the fibers. In conclusion, it was observed that collectively, these parameters impacted the magnitude and distribution of surface porosity, warpages of fibers, and micro voids. Yallew et al.25 studied the tensile strength of hemp/sisal/jute reenforced polypropylene composite with different processing aids such as pressure, temperature, and curing time. It was observed that the optimum molding temperature of 185 °C resulted in a 33.3% improvement in tensile and bending performance and properties, highlighting the necessity for better management of processing aids.

Extensive studies consistently shown that optimal pressure is essential for minimizing voids and ensuring proper resin flow, while precise temperature control is crucial for achieving complex matrix curing without degrading the natural fibers. These results highlight fiber and molding parameters determine the mechanical and thermal characteristics of hybrid composites in compression molding. The appropriate selection of process parameters influences the bonding between reinforcing fibers and the matrix resin. Strong interfacial adhesion enhances mechanical properties and thermal stability. Conversely, poor parameter selection can result in weak interfaces and inferior properties. Optimizing these factors ensures strength and quality in the fabrication of hybrid composites26,27,28,29.

Numerous researchers have utilized various Design of Experiment (DoE) strategies, including the Taguchi method, RSM, GRA, artificial neural networks and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems, to study and optimize the mechanical properties of manufactured composites30. Few studies have focused on optimizing the compression molding process parameters of manufacturing of NFRC. In this regard, Binoj et al.31employed Taguchi’s experimental technique to design the experiments for the areca fruit husk fiber composites, considering various fiber lengths and gauge distances. The samples were fabricated using compression molding technique according to ASTM standard. To determine the individual effect of input parameters that affected the variation of responses, ANOVA was utilized. The adequacy of the developed model was checked by confirmation experiments.

Li et al.32 designed the three factor and five level orthogonal design to explore the effect of process parameters on mechanical and thermal characteristics of bamboo fiber-reinforced polypropylene composite. The experimental trials runs were conducted with molding pressure, molding temperature, molding time, preheating time.

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a statistical technique that is used to design experiments, analyze the effects of process variables, establish the empirical relationship between inputs and outputs, and identify the optimal conditions. The two most commonly used RSM-based methodologies for modeling process parameters (control variables) in order to produce high-quality composite products are Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD). He L33, have applied response surface methodology to investigate the molding processing aids on mechanical properties of jute reinforced polypropylene composite and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to check the adequacy of the mathematical model. Thanikodi et al.34 applied RSM for optimal planning of experiments in the fabrication of hybrid composite composited of jute and kenaf fiber. The study used the central composite design (CCD) in RSM to examine to impact of mechanical characteristics in the composite formulation.

Likewise, Chauhan & Gope et al.35 designed the experiments for three factors at four levels by utilizing Taguchi method. The results showed that a combination of chemical treatment and improved yielding strength, bending strength, and energy absorption by 336.32%, 136.93%, and 308.28%, respectively, over epoxy alone. The significance of process parameters was determined by F-test of ANOVA. Mann et al.36 have performed the parametric analysis of jute/sisal reinforced polylactic hybrid composite using Taguchi L9 orthogonal model. SEM analysis revealed failure mechanisms in the fabricated samples. Furthermore, ANOVA was utilized each input variable significantly impacted the outcome, with a 95% confidence level. However, it is observed that most of the results are not favourable due to the uncertainty associated with the process variable.

A few researchers have used grey fuzzy optimization techniques to determine the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber–reinforced composite accurately. The fuzzy logic technique is used to predict the output responses by framing the fuzzy logic rule-based models. The rule-based framing depends on the relation between input and output responses.

Murugan et al.37 employed grey-fuzzy technique to analyse the effect processing parameters on mechanical properties of kenaf/snakegrass hybrid composite. To check the validity of the model, ANOVA was employed to analyse the individual impact on response and %reinforcement is the most influencing parameter followed by NaOH, molding pressure and molding temperature. Kafaltiya et al.38 developed the Grey-fuzzy algorithm to obtain the most optimal process parameters in enhancing strength and toughness for biodegradable composite. The experiments were carried out based on Taguchi L16 orthogonal array. ANOVA analysis was used to find out the most influencing process parameters in fabrication of biodegradable composite. Gangwar et al.39 used Taguchi L27 orthogonal technique followed by Grey fuzzy technique to investigate the mechanical properties of kenaf epoxy composite and found that GFG minimizing ambiguity and producing outcomes that closely correspond to a positional value.

Mounika et al., Mounika et al., 2024 optimized the machining operations using Taguchi approach followed by fuzzy linguistic reasoning for enhancing the quality-productivity. Bhowmik et al.40 adopted the grey fuzzy algorithm to optimize the multiple Reponses. They reported that the fuzzy model accurately predicted the desired performance of hybrid composite with error percentage of 2.29% through carefully selected membership functions. Guo et al.41, had employed fuzzy reasoning technique to find the optimal combination of input variable. They reported that fuzzy logic is effective in addressing the uncertainties and vagueness associated with inappropriate process variables. The author implemented the grey-fuzzy technique to optimize process parameters42. They found that grey-fuzzy reasoning grade had improvement in reducing fuzziness compared to the grey relational grade value.

While significant research has optimized fiber-related parameters (type, treatment, hybridization ratio), a critical gap remains in the systematic optimization of the compression molding process parameters. Most studies utilize hand lay-up techniques and focus on a single response. Furthermore, while statistical DoE methods like Taguchi and RSM are common, the multi-response optimization of mechanical properties (tensile, flexural and impact) involves inherent uncertainty and subjective trade-offs. Advanced technique like Grey-Fuzzy Logic, which effectively handle such uncertainty and vagueness, have seen limited applications in optimizing the compression molding process for natural hybrid composite29,31.

Therefore, this study aims to bridge this gap by

-

To fabricate Kenaf/Jute fiber-reinforced epoxy hybrid composite via compression molding by systematically varying key parameters: Kenaf/jute weight fraction and process parameters (molding pressure and molding temperature) for compression molding of hybrid composite.

-

To employ an integrated Grey-Fuzzy logic optimization approach to determine the single optimal parameters combination that simultaneously maximizes tensile strength, flexural strength and impact strength.

-

To identify and rank the relative significance of each input parameter on the overall mechanical performance using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).

-

To Validate the optimized results through confirmation tests and characterize the morphological, chemical and thermal properties of the untreated and optimal sample to elucidate the underlying improvements mechanism.

Materials and methods

Materials

LY556 epoxy resin and HY951 hardener (Huntsman Advanced Materials) were used as matrix system, mixed at a weight ratio of 10:1 as per the manufacturers datasheet. The resin has a density of 1.15 and 1.20 g/cm³ and a viscosity of 10,000–12,000 mPa.s at 25 °C. Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) and jute (Corchorous olitirius) stems were sourced from a local supplier in tamilnadu, india.

Fiber extraction and alkali treatment

The fiber extraction and treatment procedure was conduced as follows, with all process repeated for three separate batches to ensure consistency.

Water Retting

The collected Kenaf and Jute stems were bundled and fully submerged in static water tank. The retting was conducted at ambient temperature (25 ± 2° C) for 20 days to allow microbial action to breakdown the pectins and gums binding the fibers to the stem. The water is not heated and circulated.

Fiber washing and drying

After retting, the bundles were removed and the fiber were manually separated from the degraded bark. The fibers were then thoroughly washed under running tap water to remove all residual organic debris and were subsequently rinsed with distilled water. The washed fibers were first air-dried for 48 h in shaded area to remove surface moisture. They were then oven-dried at 70 °C for 2 h in a hot-air oven (Make: Bio Technics India, Model: BTI-75) to achieve a constant weight and reduce the moisture content to below 5%.

Alkali (NaOH) treatment

The dried fibers were treated with sodium hydroxide solutions of varying concentrations (0,3,5,8 wt%). The treatment was performed with the following precise parameters.

Solution temperature:

25 °C (Room Temperature).

Immersion time:

3 h under constant gentle mechanical agitation.

-

Solid-to-Liquid Ratio: A ratio of 1:15 was maintained (e.g., grams of fiber per 300 ml of NaOH solution) to ensure consistent and sufficient chemical exposure for all fibers.

-

Post-Treatment Washing: After treatment, the fibers were neutralized by washing with a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution for 5 minutues to remove any residual NaOH adhered to the fiber surface. This was followed by a final rinsing with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved in the wash water.

-

Drying: The treated fibers were agin over-dired at 70 °C for 2 h to achieve a constant weight. Table 1 presents the physical and mechanical properties of kenaf and Jute fiber.

Experimental design and plan of investigation

Taguchi’s methodology is an effective strategy for improving system quality in diverse domains through the optimization of process parameters. Formulated by Dr. Genichi Taguchi, this methodology employs orthogonal array experiments to reduce experimental errors and determine the optimal combination of variables. Table 2 depicts the factor and its level. In contrast to the complete factorial design, which examines all potential variable combinations, the Taguchi design selectively evaluates a limited number of combinations, thereby considerably decreasing the required number of experiments. Taguchi analysis employs systematic experimental design and data analysis to effectively identify optimal process parameters, hence enhancing performance and quality while minimizing resource expenditure. According to the literature, the interfacial strength and compatibility of hybrid composites are governed by fiber weights, NaOH and molding parameters, and molding temperature. Alkaline treatment eliminates hydroxyl groups from the surface of the fiber by reacting with NaOH to produce water molecules43. Nevertheless, too high a concentration of NaOH might result in problems such as the removal of lignin, breakage of fibers, and difficulties in controlling the process. In this study, NaOH (0, 3, 5, 8%) was selected to ensure the alkaline treatment’s biocompatibility with matrix and enhance the characteristics. Likewise, based on previous studies, inadequate pressure can lead to voids or porosity, affecting the composite’s quality, while excessive pressure can cause cellulose damage, fiber deflection, and matrix rich areas. Research shows that pressures beyond 17 MPa can cause fiber deterioration, cellulose damage, and resin overflow, compromising the composite’s mechanical strength44. it was It was decided to use molding pressures of 10, 12, 14, and 16 MPa to maintain the quality and prevent excessive matrix impregnation. On the other hand, the optimal processing temperature for compression molding in NFRHCs should be higher than the polymer matrix’s melting point but lower than the temperature at which fiber deterioration begins, typically around 200 degrees. Lower mold temperatures may impede the epoxy matrix from fully melting and achieving optimal flow, resulting in increased resin viscosity. however, higher viscosity hinders smooth matrix material flow, leading to incomplete impregnation of reinforcing fibers. Conversely, excessively high mold temperatures can significantly impact fiber degradation, negatively affecting mechanical properties. Maintaining the appropriate temperature is essential for ensuring thorough fusion of the matrix, allowing proper infiltration of fiber bundles and enhancing adhesion between interfaces, ultimately increasing mechanical strength. the chosen molding temperature range (100 to 120 °C) aims to keep the epoxy resin in a sufficiently molten state for effective molding and shaping processes45,46. This temperature is sufficient to maintain a low resin viscosity for effective fiber impregnation but is below the ~ 200 °C threshold at which significant thermal degradation of cellulose-based kenaf and Jute fibers begins47,48. Furthermore, studies have shown that curing epoxies at temperatures above their final Tg is necessary to achieve a high degree of conversion and strong polymer network49. These parameters play a significant role in enhancing desired performance during the fabrication of hybrid composites. The assessment of response variables is classified according to three criteria: lower-the-better, larger-the-better, and nominal-the-best. Table 3 presents the Taguchi L16 orthogonal array for fabrication.

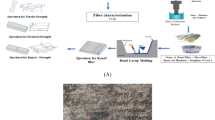

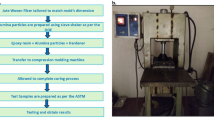

Fabrication of hybrid composites

The manufacturing process of kenaf/jute hybrid composites follows a systematic procedure to ensure high-quality output. The fibers are oven-dried for 5 h, and each blend incorporates 300 g of epoxy resin and 30 g of hardener. A 300 × 300 × 5 mm mold is used to compress the fibers along with the epoxy-hardener mixture. Initially, wax is applied to the bottom mold surface to prevent adhesion. The fibers are then manually laid and compressed, followed by the uniform application of the resin mixture. The mold is closed and heated, during which the resin-impregnated fibers are consolidated under controlled pressure and temperature. The composite is then pressure-cooled, which solidifies the structure and enhances its mechanical properties. After cooling, the composite is demolded and allowed to cure at ambient temperature. The samples are precisely trimmed using a CNC cutting machine to meet ASTM standards, ensuring consistent and reliable testing. Figure 1 illustrates the experimental fabrication process of the kenaf/jute hybrid composite.

Optimization steps using grey-fuzzy logic

Grey Relational Analysis (GRA), introduced by Prof. Deng, is a method for multi-response optimization in uncertain, incomplete data, and multi-variable systems. It measures the grey relational grade, a degree of approximation among sequences, and is particularly useful in composite material analysis for optimizing multiple response variables such as Tensile strength, flexural strength, and impact strength. GRA consists of data preprocessing, response characteristic normalization, grey relational coefficient calculation, and grey relational grade evaluation. Normalization provides comparability across data scales and prepares data for analysis. The coefficients determine the relationship between experimental results and target values and reduce the multi-response optimization problem to a single-response problem. The Taguchi approach determines optimal factor settings to identify optimal settings, making grey relational grade analysis to define the configuration having the highest performance. The Taguchi approach discovers key factors playing a role towards desired composite attributes and confirms outcomes, improving efficiency and reliability in the optimization procedure.

Step 1: Data pre-processing

GRA data preprocessing consists of normalization in order to reduce variability in response. Various methods are used based on the nature of the data sequence. Two major types exist: “lower-the-better” and “higher-the-better.” The “lower-the-better” feature is employed in normalizing data sequences when smaller values signify better performance. The normalized value is determined using Eq. (1) in order to properly represent and compare data.

\(\:{y}_{j}\) = original value, \(\:\text{max}{y}_{j}\) and \(\:{min\:y}_{j}\left(t\right)\)= Maximum and minimum value in the output response, t=quality function j= trial numbers

\(\:{x}_{j}\left(t\right)\) represents normalized data after processing the output responses. The “higher-the-better” characteristic is used to normalize data when the goal is to maximize a response. This approach ensures that higher values indicate better performance. It enables accurate and consistent evaluation across multiple response variables.

Step 2: Deviation Sequence

The Grey Relational Coefficient (GRC) is computed for every response in Taguchi’s L16 orthogonal array following data processing or normalization, evaluating the relationship between each response and the ideal reference between each factor on overall performance. The deviation sequence is a crucial component in GRA, which decides the level of similarity between a reference and a data sequence. It is measured by comparing the absolute difference between each data point and the reference value, enabling comparisons to be made consistently across measurements and sequences using Eq. (3)

where \(\:{\varDelta\:}_{0j}\) = \(\:{x}_{0}\left(t\right)\) − \(\:{x}_{i}\left(t\right)\) represents the After normalization, the difference among the original quantification \(\:{x}_{0}\left(t\right)\)and normalized quantification \(\:{x}_{j}\left(t\right)\) is the absolute value

In general, \(\:{\xi\:}_{i}\) has been set to 0.5 for most cases.

In GRA, \(\:{\varDelta\:}_{0j}\) is the variation in original responses with time. The differentiation factor µ, typically set to 0.5, which is usually equal to 0.5, provides equal weightage to factors. Δmin and Δmax are the minimum and maximum of the data prepared. This method aids in the efficient analysis of deviation sequences.

Step 3: Grey Relational Grade

Grey Relational Grade (GRG) is a performance measure based on the mean of the aggregated Grey Relational Coefficients (GRCs) for every response. GRG in GRA simplifies multi-objective optimization problems to a single-objective problem. GRG measures range from 0 to 1, and values closer to 1 mean better performance. In this research, GRG for every response in Taguchi’s L16 orthogonal array was determined using a particular Eq. (4)

\(\:{y}_{i}\) = signifies the overall GRG. \(\:\eta\:\) = total number of output results;\(\:\:{y}_{i}^{2}\) = Each response of GRG.

Grey-Fuzzy logic

The grey-fuzzy system, a combined framework developed by Zadeh and fuzzy logic, addresses inherent uncertainty in GRA by simplifying multi-response optimization and enabling more precise decision-making. This approach accounts for inherent uncertainties in data evaluation, enabling the optimization of multi-variate systems and enhancing the effectiveness of multi-response methods compared to traditional methods. Grey-fuzzy analysis includes converting grey relational coefficients into fuzzy values via membership functions. This conversion facilitates the interpretation of fuzzy data using linguistic variables. These inputs are processed by a fuzzy inference engine (FIE) based on fuzzy rules developed by experts to allow proper evaluation of outcomes in sophisticated multi-variable scenarios. These rules are trained and processed to enhance the effectiveness of decision-making capabilities in uncertain and unclear data. Figure 2 depicts the processes of the grey-fuzzy model for multiple-response optimization. The if–then statement rule of the Mamdani model (Table A1) can be represented as follows,

Rule 1: if x1 is A1 and x2 is B1 and x3 is C1, then y is D1; Else

Rule 2: if x1 is A2 and x2 is B2 and x3 is C2 then y is D2; Else

Rule n: if x1 is An and x2 is An and x3 is Cn, then y is Dn; Else

In fuzzy logic, X1, X2, X3 inputs are processed through unique fuzzy subsets represented by An, Bn, Cn, Dn, while y denotes output result. The fuzzy subsets, characterized as µAi, µBi, µCi, µDi are a direct result of the membership functions such as Ai, Bi, Ci, Di. The defuzzifier is ultimately rather important since it converts the fuzzy value into a crisp, non-fuzzy one called the multiperformance index (MPI). In view of the membership function, multi-objective response fuzzy values are determined as follows Eq. (5)

This process involves finding the most representative, readable, and crisp value based on the fuzzy output distribution (Table A2). It subsequently helps in mapping input to output by converting the fuzzy output into a clear and interpretable multi-performance index (MPI) expressed as an unfuzzy value (GFG)40 using Eq. (6)

This approach enhances accuracy and robustness in making predictions, especially in complex and uncertain real-world scenarios. Figure 3 presents a triangular membership function for input variables and output variables.

Testing and characterization techniques

Tensile test

Tensile tests were performed with the help of Universal Testing Machine (AG-X Plus, Japan) with a 20 kN load cell, according to ASTM D 638–03 standards. Specimens were 165 mm in length, 20 mm in width, and 3 mm thick. The cross-head speed was kept constant at 5 mm/min throughout the test. Results were meant, and standard errors were calculated from a minimum of five specimens. This provided accuracy and reliability to the tensile strength testing.

Flexural test

Three-point bending tests were done on composite specimens of 125 mm × 20 mm × 3 mm utilizing the Universal Testing Machine (AG-X Plus, Japan) with a 10 kN load cell, following ASTM D790 criteria. The bending support length (load span) was fixed at 50 mm, and the cross-head speed was maintained at 1.4 mm/min throughout the test. The average values and standard errors were computed based on at least five test specimens to ensure accuracy and consistency.

Impact testing

The Charpy impact test was conducted following ASTM D256 standards to evaluate the impact resistance of the manufactured composite specimens. V-notched specimens with dimensions of 64 mm × 13 mm × 3 mm were precisely cut for the testing process. A 2.634 kg pendulum was released at a 150° angle to strike the specimen, with an indicator used to accurately determine the exact angle of impact. The impact energy absorbed by the specimens was calculated using the chart provided with the impact tester. To ensure reliability and accuracy, at least five specimens were tested, and the average value, along with the standard error, was reported.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The fracture surfaces of tensile-tested specimens were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, SU1510, Hitachi, Japan) to investigate their internal microstructure. Cross-sectional views were prepared to accurately represent the internal features of the specimens. The samples were mounted on brass bits or aluminum stubs to ensure stability during analysis. To enhance electron conductivity, all specimens were coated with a thin layer of gold particles for approximately 20 min using an AGAR sputter coater. Following this preparation, SEM micrographs were captured to observe the morphological characteristics and fracture behavior of the specimens.

Characterization techniques

The chemical, crystalline and thermal properties of untreated and optimally treated kenaf/Jute hybrid composites were characterized to elucidate the mechanism behind the improved mechanical performance.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was used to identify the functional groups and chemical changes in the fibers after the alkaline treatment. The analysis was performed using a shimadzu IRspriet spectrometer. Sample were prepared in the form of fine powder mixed with spectroscopic-grade KBr and pressed into pellets. The spectra were recorded in the wavelength range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans per sample.

X-Ray diffraction (XRD)

X-Ray Diffraction analysis was conducted to determine the effect of 5 wt% NaOH treatment on the crystallinity of kenaf/jute hybrid composite. The XRD patterns were obtained using a Rigaku smartLab X-Ray diffractometer with CuK (k = 1.54, 40 kV, 40 mA) in the range of 2θ = 5–50° with a scanning rate of 2°/min. The structural composition of the hybrid composites can be determined using the Segal equation, as shown in Eq. (1), and its crystalline nature can be inferred from the diffraction pattern.

where I200 is the maximum peak intensity at the 200-lattice plane (crystalline area) and Iam is the peak at 2 h = 18° (amorphous area). We utilized Bragg’s equation to determine the d-spacings and the Scherrer equation to calculate the crystallite sizes, as shown in Eq. (8).

Where, K - Scherrer’s constant (0.9) or correction factor

λ - radiation wavelength

β1/2 - peak width at half maximum intensity

D - crystallite size (in nanometres)

θ - diffraction angle (degree)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The thermal stability and decomposition behaviour of the untreated and optimally treated composites sample were investigated using Thermogravimetric Analysis. The tests were performed on a TA instruments TGA Q50 analyzer. Approximately 5-20 mg of sample was placed in a platinum crucible and Heated from ambient temperature to 700 °C at a constant Heating rate of 20 °C/min under a nitrogen purge gas flow of 60mL.min. The weight loss (wt%) as a function of temperature was recorded. The derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves were obtained to identify the temperature of maximum degradation rate for the different components.

Results and discussion

The study focuses on optimizing the process parameters for fabricating kenaf/jute hybrid composites using the grey-fuzzy approach. Taguchi’s L16 orthogonal array was employed to design experiments efficiently. The multi-objective optimization problem was transformed into a single-objective framework, and the optimal parameters were validated through confirmatory experiments. The results collected are analyzed in the next subsections.

Grey relational grade (GRG)

The necessity of obtaining increased tensile strength, impact strength, as well as flexural strength, is of great importance for the greater performance of kenaf/jute reinforced hybrid composites for effective use in applications. Table 4 shows the analysis process of experimental data for obtaining normalized data and calculating grey relational coefficients. Using Equation (1), the normalization process employed the higher-the-better technique, resulting in normalized experimental results that were consistent across the different runs. Then, the grey relational coefficients for the performance characteristics were calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4). Subsequently, Table 5 also depicts corresponding grey relational coefficients and the combined grey relational grade, along with their respective rankings. Significantly, experiment no. 12 exhibited the maximum grey relational grade of 0.9139, which meant that the best combination of input factors for overall tensile, impact, and flexural strengths. Interestingly, the grey relational coefficients for impact and flexural strength were at unity, which meant that they had attained the maximum performance levels, while that of tensile strength was not the same. This discrepancy accentuates the need to apply the grey relational grade method to properly balance and optimize the mechanical properties of the hybrid composites. The grey relational grade thus becomes a critical element in optimizing the global mechanical performance, such that the composites serve to meet the high demands of various industrial applications.

Grey fuzzy analysis (GFG)

This grey-fuzzy reasoning grade (GFG) for kenaf fiber/jute hybrid composite formulations was predicted and analyzed successfully using the MATLAB interface. The grey relational coefficients for tensile strength, impact strength, and flexural strength were included in the input parameters of the system. An ideal triangular membership function was used to achieve these inputs by dividing each of the parameters into three forms of linguistic sub-sets, namely low, medium, and high, as shown in Fig. 3. This output variable, known as the Multi Performance Index (MPI), was expressed using seven different linguistic subsets Very Very Low (VVL), Very Low (VL), Low (L), Medium (M), High (H), Very High (VH), Very Very High (VVH) as represented in the corresponding Fig. 3. This combination allowed a more systematic and exact examination of uncertainty and vagueness in the fabrication hybrid composite. Also, sixteen fuzzy rules were developed to ensure consistency and validity in assessing the three mechanical properties. These guidelines allowed a complete prediction of the grey-fuzzy reasoning grade for every trial environment by establishing their principles on the combinations of the linguistic subsets. Combining these fuzzy logic principles allowed the system to evaluate and improve the mechanical characteristics of the composite in a sophisticated manner, therefore promising the best performance results.

Figure 4 shows a graphic representation of the rule sets, subsequently displaying the link between grey relational coefficients of mechanical characteristics as inputs and the grey-fuzzy reasoning grade as output. Whereas the fourth column indicates the outcome variable, the grey-fuzzy reasoning grade (GFRG), the first three columns in the picture match the input parameters tensile strength, impact strength, and flexural strength. For instance, the result value for experiment 12, after defuzzification, is recorded as 0.888, as seen in Table 6. Similarly, grey-fuzzy reasoning grades for all 16 experiments were predicted using the fuzzy logic modeling approach and are reported in Table 6. Corresponding, Fig. 5 provides a comparison study between the original grey relational grades (GRG) and the associated GFRG values across all experimental situations. These results clearly indicate that GFRG values continuously beat the classic GRG values, Hence eliminating ambiguity and boosting result accuracy. Furthermore, experiments 14 and 7 were placed second and third, with GFRG values of 0.8236 and 0.782, respectively. The corresponding Optimal mechanical properties were achieved with a composite formulation of 20wt.% KF, 25wt.% Jute, 5% NaOH, 10 MPa pressure, and 120 °C temperature, as determined by the response outcome in Fig. 6 and response Table 7 (Higher the better). Grey-Fuzzy based multi-response framework developed in our current study has pinpointed optimal configurations with a GFG value exceeding 0.8, which aligns well with the 0.75–0.85 range found in similar multi-response optimizations50,40. This alignment reinforces the effectiveness of our method for modeling and optimizing the mechanical behavior of hybrid composites. This complete approach demonstrates the efficiency of fuzzy logic modeling in optimizing the mechanical features of kenaf/jute hybrid composites, ensuring higher performance and more dependable outcomes.

Response of grey-fuzzy for kenaf/jute hybrid composite

The grey-fuzzy reasoning grade response table and corresponding graph are given in Table 7; Fig. 6 for varied input composite fabrication parameters and their subsequent levels. such as kenaf wt%, jute wt%, NaOH wt%, molding pressure, and molding temperature. The optimal properties of NFRHCs can be achieved through 20wt.% KF, 25wt.% Jute, 5% NaOH, 10 MPa pressure, and 120 °C temperature was determined to yield the best results as shown in Fig. 7. The inclusion of KF and jute at 20 and 25 wt% significantly enhanced the tensile, flexural, and impact strength of the hybrid composite. Surface treatment with 5% NaOH increased the aspect ratio by decreasing the diameter of the fiber, while higher concentrations resulted in poor interfacial adhesion.

High and low temperatures affect composite properties differently. Low mould temperatures cause the epoxy matrix to not fully melt or flow, leading to inadequate fibre impregnation effect, non-uniform flow, and micro voids. High molding temperatures enable consistent matrix flow and activate the three-dimensional network between fiber and matrix. Likewise, high and low pressures also affect the composites’ properties. High compression pressures force the fiber inside the matrix, reducing micro-voids, but excessive pressure can lead to damage to the hollow structure and its cellulose structure, resulting in loss of tensile, flexural, and impact strength. Conversely, low pressure resulted to insufficient consolidation and void entrapment. The optimal compression pressure for enhancing material strength was identified as 10 MPa, but beyond this threshold, there was a decrease in tensile, flexural, and impact strength with an increase in molding pressure. This positive outcome can be attributed to the synergistic effect between optimized fiber processing techniques and controlled molding conditions, leading to an improved even distribution of matrix material throughout the laminate structure, resulting in significantly enhanced tensile, flexural, and impact strength. Optimizing the temperature to 120 °C thermally activates intermolecular interactions, resulting in a stronger and more interconnected network within the composite.

Morphology of fabricated samples

The study examined the mechanical properties of NFRHCs under three magnifications, providing insights into phase alterations. Morphology of fabricated specimens showed variations in compression pressure, resulting in different results for untreated, high, and optimal molding conditions. Figure 8 shows the morphology of fabricated specimens: (a) 10 wt% KF and 10 wt% Jute fiber, 0% NaOH, 10 MPa pressure, and 100 °C temperature; (b) 15 wt% KF, 10 wt% Jute fiber, 3% NaOH, 12 MPa pressure, and 120 °C compression temperature; (c) 20 wt% KF, 25wt% Jute fiber, 5% NaOH, 10 MPa pressure, and 120 °C temperature.

Untreated with low molding conditions

Figure 8a shows fiber pullout, indicating poor adherence between fiber and matrix is caused by non-cellulosic components like hemicelluloses, lignin, and wax, which hinder the effective bonding. The presence of resin-rich zones and micro-voids, and uneven matrix distribution, facilitates crack initiation and propagation. Upon closer inspection revealed that insufficient low molding conditions cause the epoxy matrix to fail to melt or flow correctly, increasing resin viscosity. This impairs fiber impregnation, promotes void formation, resin rich area significantly degrades the overall performance of the composite.

Treated with high molding conditions

As illustrated in Fig. 8b, low concentration treatment of fibers was insufficient to eliminate non-cellulosic content, resulting in poor biocompatibility between fiber and matrix interfacial adhesion. Conversely, excessive molding conditions damaged cellulose structure, inducing fiber deformation, interfacial delamination, and matrix rupture. These failures affect fiber wetting out and impregnation, lowering composite mechanical performance. Moreover, elevated molding temperature and pressure may accelerate resin gelation, leading to incomplete matrix flow and agglomeration. High pressure also increases the mold-release difficulty, negatively affecting the laminate quality and effectiveness.

Treated with optimum molding conditions

Figure 8c demonstrates that the optimized alkaline treatment effectively disintegrates fiber bundles into smaller fibrils, produce a clean and rough surface that makes it easier for the fiber matrix to mechanically interlock with other fibers. The 5 wt% alkaline treatment makes the interface very wettable and lets loads move across it easily. But too much treatment can make biocompatibility weaker and cause too much cellulose to be released. Also, the best molding pressure and temperature, which is 10 MPa and 120 °C, work together to make sure that the resin flows evenly, that it penetrates better, and that the bonds between the two materials are strong. additionally, the presence of more microfibrils on the surface increase the surface area even more, which enhances interlocking points. Treated fiber had much higher tensile, flexural, and impact strength 53.72%, 41.74%, 64.03%, and 34.44%, 18.06%, and 65.86%—when compared to untreated fiber with low molding and treated fiber with high molding.

Interfacial adhesion mechanism

The enhancement in mechanical properties observed in the optimally treated composite fundamentally governed by the improved interfacial adhesion between the fiber and epoxy matrix. The mechanism for this improvement is twofold, stemming from both chemically treatment and optimal processing conditions.

Figure 9 represents the 5 wt% NaOH treatment plays a critical chemical role. It effectively hydrolyzes and removes amorphous constituents like hemicellulose, lignin, waxes and surface impurities from the fiber surface. This purification process confirmed by reduction of C = O peak (1730 cm⁻¹) and the broad O-H peak (3200–3500 cm−1) in the FTIR analysis (Fig. 10), exposes more reactive cellulose OH groups and creates a cleaner, rougher surface topography. This increased surface roughness as visible in the SEM micrograph (Fig. 8c), enhances mechanical interlocking by providing more sites for epoxy resin anchor onto the fiber43,51. optimized molding parameter (10 MPa, 120 °C) are crucial for facilitating and realizing this enhanced adhesion. The elevated temperature (120 °C) reduces the viscosity of the epoxy resin, allowing it to effectively wet the newly exposed and roughed fiber surface52,53. Concurrently, the applied pressure (10 MPa) forces the low-viscosity resin to infiltrate the micro voids the spaces between the fibrils, ensuring complete encapsulation of the fibres54. This synergistic effect of temperature and pressure minimizing defect-forming air pockets and promotes intimate contact at the fiber-matrix interface.

The combination of these factors ensured that the fibers were embedded within the matrix, with clear resin adherence on their surface. The predominant failure mode shifts from interfacial debonding to fiber fracture itself, confirming that the interface was strong enough to tranfer the applied load effectively55. These mechanisms prevent premature failure modes such fiber pullout and minimal voids and gaps and interfacial debonding as seen in Fig. 9, thereby leading to the observed simultaneous maximization of tensile, flexural and impact strength.

Analysis of variance

The objective of conducting an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is to determine the variable that has the most significant impact on the multi-responses of fuzzy output. ANOVA results for the grey-fuzzy reasoning grade (GFRG) as shown in Table 8. ANOVA is a statistical approach used to analyze results in of variation within a dataset and discover the components that contribute most to the observed differences. The results in Table 8 reveal that the jute content (P = 0.05) has the most noteworthy impact on GFRG, reflected by its high F-value of 44.33. This shows that jute fiber is the most critical factor determining the mechanical performance of the composite followed by important characteristics are molding pressure (F = 25.44), kenaf fiber weight% (F = 9.70), NaOH treatment (F = 5.85), and molding temperature (F = 0.96), each resulting to changes in the multi-response outputs. The model’s quality of fit is evaluated using the determination coefficient (R²), which in this case is 0.99. Figure 10 displays the residual plot for the grey fuzzy grade. This high R² result reveals a good correlation between the experimental data and the model predictions, suggesting that the model accurately captures the variability in the data41,42,56.

Multiple linear regression model analysis

A multivariate Linear regression model was employed to illustrate the relationship between the independent variable and a single grade. This involved formulating a Linear equation that precisely represents the data collected, Grey-fuzzy multi-response optimization. The construction of the multiple Linear regression model was carried out using MINITAB 15 software, utilizing the experimental data as a foundation. Through regression analysis, the grey fuzzy grade can be forecasted based on predetermined levels of factors.

Confirmation test

The enhancement of the grey-fuzzy reasoning grade (GFRG) is validated by performing a confirmation test. To validate the expected outcomes, it is vital to check the appropriate parameter levels A3, B4, C3, D1, and E1. The GFRG can then be tested using the stated equation, confirming the correctness and dependability of the optimal manufacturing parameters for better composite performance.

A confirmation test was conducted to verify the optimal combination of process parameters A3B4C3D1E2 as determined by MINITAB. The observed value of the GFG is greater than the expected value for this optimal parameter set. Table 9 demonstrates a substantial correlation, with a minor percentage error of 2.96% between the experimental and expected outcomes.

where \(\:{Z}_{z}\:\)is the average mean of the GFG at a level, \(\:{Z}_{i}\) – optimized value of average GFG, and η is the processing impact on the output responses.

FTIR analysis of untreated and optimal condition of hybrid composites

Fourier-Transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to analyse the chemical modifications in both untreated and optimally treated (5 wt% NaOH) Kenaf/jute hybrid composite as represented in Fig. 11. The spectra provide detailed insight into the structural changes occurring in key lignocellulosic components like cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin following alkaline treatment.

The broad absorption band observed at 3200–3500 cm−1 in the untreated fibers correspond to O-H stretching vibration from hydroxyl groups in cellulose and hemicellulose. A noticeable reduction in the intensity of this band was observed in the treated composite spectrum, indicating effective removal of hemicellulose and partial dissolution of lignin due to NaOH induced disruption of hydrogen bonds57. This reduction also signified decreased hydrophilicity, enhanced compatibility with hydrophobic epoxy matrix.

The peak near 1730 cm−1, attributed to C = O stretching of acetyl and ester groups in hemicellulose and lignin, showed significant attenuation after treatment. This confirms the substantial removal of non-cellulosic components, which aligns with findings by Ghori S52-, who reported similar decreases in carbonyl band intensity following alkaline treatment of date palm/Kenaf hybrid composite. The reduction of this peak is critical, as it correlates with enhanced cellulose exposure and improved fiber-matrix adhesion. Likewise, Bekele A et al.58reported that alkaline treatment reduced hydrophilicity while preserving crystalline cellulose. The typical FTIR signature of these modification include the disappearance of carbonyl band near 1730 cm⁻¹ (acetyl/ester groups in hemicellulose and lignin), and decrease in the broad O-H stretching band 3200–3500 cm−1 and persistence of cellulose specific peaks such as the C-O-C stretching vibration around 1050 cm−1. Likewise, Islam M et al.59observed the 1730 cm−1 carbonyl band vanish in alkali-treated lignocellulosic fibers, indicating hemicellulose/lignin extraction and enhanced compatibility.

In the fingerprint region (600–1500 cm−1), alterations in C-O, C-H and C-C vibrations were observed, indicating modifications within the polysaccharide structure. Similar changes have been observed in earlier studies, where alkaline treatment disrupted amorphous hemicellulose and lignin phase, leading to spectral variations in this region60. These changes suggest reorganization of the cellulose microfibrils and removal of amorphous content, further supporting the crystallinity enhancement observed in XRD analysis. The stability of cellulose-specific bands (e.g., C-)-C stretching at 1050 cm−1) confirming that the core cellulose structure remained intact under the optimized treatment conditions, preserving the mechanical integrity of the fibers61.

Notably, no emergence of new peaks was detected, confirming that the alkali treatment cleans the fiber surface without introducing new functional groups. The optimal treatment with 5% NaOH effectively balances the removal of amorphous components with preservation of crystalline cellulose, avoiding excessive degradation that could compromise fiber strength62.

These chemical modifications are directly linked to the mechanical properties of the composite. The removal of hemicellulose and lignin reduces weak interfacial layers, while the increased cellulose crystallinity and surface roughness promotes mechanical interlocking and interfacial bonding with the epoxy matrix63. This corroborates the enhancement in tensile, flexural and impact strength in this study and validates the efficacy of the grey-fuzzy optimized treatment parameters.

Crystalline behaviour of untreated and optimal sample of hybrid composites

The crystallinity of the kenaf/Jute fiber both untreated and after NaOH treatment, was investigated using X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) as shown in Fig. 12. The selection of the optimal treatment condition (5 wt% NaOH) for this discussion is based on the comprehensive multi-response optimization (Grey Fuzzy Logic) which identified this concentration as yielding the superior balance of tensile, flexural and impact strength in the final hybrid composite.

The XRD pattern of the untreated hybrid fibres exhibits the characteristics profile native cellulose I at 2θ angles of 22.24°, which correspond to the 002 crystallographic planes. The pattern confirms the successful extraction of fibers with robust inherent crystalline structure. The broad hump underlying these peaks is indicative of a significant presence of amorphous non-cellulosic components such as hemicellulose, lignin and pectin. This pattern is consistent with native cellulose I structure present lignocellulosic fibers of kenaf and jute fibers64, Moreover, Keshk S65 has established natural fibers a sustainable resource for eco-friendly composites, highlighting their inherent crystalline structure.

Cellulose, the primary component of plant cell walls, generally exhibits an orderly arrangement in the form of crystals66. When X-rays interact with untreated fibers, they are diffracted by the crystalline planes of cellulose arranged in an orderly manner. This phenomenon demonstrates that hybrid fibers in the composite retain the crystalline structure of cellulose to a significant extent, even without specific treatments such as alkali67. The degree of crystallinity observed in the diffraction peak reflects the regularity and density of atomic arrangements within the fibers, directly influencing their mechanical properties68.

High-crystalline fibers in composites have greater stiffness, strength, and improved elastic modulus due to their efficient resistance. They enhance the interaction between crystalline fibers and the polymer matrix, providing more contact points for adhesion. Untreated kenaf and jute fibers retain the crystalline structure of cellulose, contributing significantly to the composite’s mechanical properties and stiffness without additional treatment. The XRD analysis of untreated fibers shows a prominent diffraction peak at 2θ ≈ 22.34◦, indicating a natural crystalline structure. After alkali treatment, peak sharpness and intensity increase, confirming enhanced crystallinity due to selective removal of amorphous hemicellulose and lignin, confirming effective cellulose structural order improvement.

The diffractogram of the optimally alkali-treated sample shows a notable sharpening and increased intensity of the cellulose I peaks, particularly the dominant (002) peak at 22.44°, indicating that the 5% NaOH treatment has influenced the crystalline structure. Table 10 shows the Crystallinity parameters of untreated and alkali-treated Kenaf/Jute Hybrid fibres. This enhancement in peak definition and reduction of the amorphous background hump are direct evidence of the treatment efficacy. The main mechanism removes amorphous components increasing cellulose crystallinity and resulting in sharper diffraction peaks. Such treatment optimization enhances the relative proportion of crystalline material, thereby leading to a higher crystallinity index (cr1). This phenomenon is well documented; for instance, Siti Syazwani et al.69 and Guo A et al.70noted that after alkaline treatment of kenaf and jute, the removal of these components resulted in an enhanced crystallinity index. The crystallinity structure of cellulose is more resistant to chemical degradation, which leads to a relative increase in crystallinity as the amorphous fraction is eliminated. Likewise, the characteristics diffraction patterns observed in cellulosic materials, particularly the distinction between crystalline and amorphous regions, have been comprehensively reviewed by Islam M71 and Samaei S72, confirming that the crystalline domains primarily contribute to the mechanical strength natural fibers.

This increase in CrI plays a crucial role in enhancing the mechanical performance of the composite. Furthermore, the treatment disintegrates fiber bundles into finer fibrils, producing a cleaner and rougher surface topography, as confirmed by SEM analysis (Fig. 8c). The combination of higher crystalline content and increased surface are promoting superior mechanical interlocking interfacial adhesion with the epoxy matrix73. This allow for more efficient stress transfer from the matrix to the stronger reinforcement fiber, thereby explaining the significant improvement of 53.72%, 41.74% and 64.03%.

It is important to note that the treatment concentration was optimized to avoid excessive degradation. While moderate alkali treatment increases crystallinity, overly severe conditions can attack crystallinity domains, cause cellulose degradation, and potentially convert cellulose I to cellulose II, ultimately compromising the fibers mechanical integrity. The Grey-Fuzzy optimization that identified 5 wt% NaOH as ideal parameter successfully struck this balance, maximizing the beneficial structural changes while preserving the individual strength of the fibers, consistent with findings by Gangwar S39 for Kenaf/epoxy composite The XRD analysis quantitatively supports the optimization process, confirming that 5wt% NaOH treatment effectively increases the crystallinity and structural intergrity of the kenaf/Jute hybrid composites.

Thermal behaviour of untreated and optimal condition of hybrid composites

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) were employed to evaluate the thermal degradation characteristics of both untreated and optimally treated (5wt% NaOH) Kenaf/Jute hybrid composite as shown in Fig. 13. The analysis exhibits distinct degradation profiles that provide crucial insights into the thermal stability and compositional changes resulting from alkaline treatment.

As shown in Fig. 13, both untreated and optimal condition exhibit three-stage degaradation behaviour typical of linguacultural based material. The initial mass loss (∼5–7%) occurring below 150 °C corresponds primarily to moisture evaporation and loss of volatile components. The marginally higher moisture content observed in untreated composites indicates greater hydrophilicity due to the presence of accessible hydroxy groups in hemicellulose and lignin components74.

The principal degradation stage occurring between 250 and 400 °C represents the thermal decomposition of cellulosic and non-cellulosic constituents75. DTD analysis reveals a maximum degradation temperature (Tmax) of 385 °C for untreated, while optimally treated composite demonstrates enhanced thermal stability (Tmax) of 390 °C. This elevation of 5 °C elevation in degradation temperature signifies substantial enhancement in thermal resistance, attributable to: (1) effective removal of thermally unstable hemicellulose and amorphous region, (2) increased cellulose crystallinity as confirmed by XRD analysis, and (3) improved fiber-matrix interfacial adhesion creating a more thermally stable composite architecture76.

The final degradation stage above 400 °C involves progressive decomposition of stable components and char formation. Treated composites demonstrated significantly higher residual char content (∼20% at 600 °C) compared to untreated samples (15%), showcased enhanced thermal stability and flame retardancy. Table 11 Thermal degradation parameters of untreated and treated composite. This increased char residue suggests that alkali treatment promotes the formation of more stable carbon structures during thermal decomposition, potentially acting as protective barriers against further degradation.

The improved thermal performance correlates directly with the thermal property enhancement observed in this study. The removal of amorphous constituents, coupled with increased cellulose crystallinity and superior fiber-matrix interface quality, creates a more thermally stable network structure77. These comprehensive improvements validate the efficacy of the grey-fuzzy optimized 5% NaOH treatment protocol for developing high performance natural fiber composites suitable for automotive and structural applications requiring enahcned thermal stability.

The findings of this study are consistent with recent literature, where Hindi J et al.78 et al. reported that alkaline treatment effectively removes amorphous constituents, thereby enhancing the thermal and mechanical performance of natural fiber composites. Similarly, Fang X and79 and Sasikumar et al.80demonstrated that NaOH treatment increases the thermal stability of lignocellulosic composites by increasing cellulose crystallinity and modifying fiber- matrix interface. In agreement, Yiga V et al.81 et al. highlighted role alkaline treatment in promoting higher char yield and flame retardancy, while Mulla M et al.82 further confirmed that thermal degradation mechanism of alkaline-treated fibers are dominated by the stabilization of cellulose-rich structure, which contribute to superior resistance.

The TGA results confirms that the NaOH treatment significantly enhances the thermal stability of Kenaf/jute hybrid composites by increasing their resistance to decomposition, reducing early-stage thermal degradation, and improving their overall durability in high temperature environments. This makes the optimizes composites particularly suitable for applications demanding thermal resistance such as automotive components and construction material where elevated temperature performance is crucial.

Conclusions

This study successfully optimized the compression molding process parameters for Kenaf/jute hybrid composites using an integrated Grey-Fuzzy Logic Approach. The Key findings, supported by concrete numerical evidence, are summarized as follows:

-

The Grey-Fuzzy logic identified the optimal parameter combination as 20 wt% Kenaf fiber, 25 wt% Jute fiber, 5 wt% NaOH treatment, 10 MPa Molding pressure and a temperature of 120 °C. This setting achieved the highest Grey-Fuzzy Grade (GFG) of 0.888, corresponding to a balanced enhancement of all three mechanical properties. The confirmation experiment under these optimal condtion yielded tensile, flexural and impact strength of 48.8 MPa, 90.1 MPa, and 33.7 kJ/m2, respectively.

-

ANOVA analysis of GFG revealed the quantitative significance of each parameter on the overall multi-response performance. Jute fiber content was the most influential factor, contributing 51.35% (F-value = 44.33, P = 0.022), followed by followed by molding pressure (29.47% contribution, F-value = 25.44). Kenaf fiber wt% (11.24%) and NaOH treatment (6.77%) had moderate effects, while molding temperature was least significance (0.37%).

-

The predicted results from the Grey-Fuzzy model showed an excellent correlation with experimental values, with a low prediction error of just 2.96% in the confirmation test. This validates the model robustness and accuracy in solving the multi-response optimization problem and mitigating uncertainties inherent in the process.

-

SEM analysis conformed that optimal parameters enhanced tensile, flexural, and impact strength by 53.72%, 41.74%, and 64.03, respectively, compared to untreated with low molding condtion. This improvement is attributed to the 5 wt% NaOH treatment effectively removing non-cellulosic components, creating a rough surface topography for superior mechanical interlocking and optimal pressure (10 MPa) and temperature (120 °C) ensuring through resin fusion and infiltration without damaging the cellulose structure. FTIR and XRD analysis confirmed the removal of hemicellulose/lignin (evidenced by the reduction of the 1730 cm-1 peak) and increase in cellulose crystallinity, which directly contributed to enhanced the mechanical and thermal properties.

-

TGA analysis demonstrated that the optimally treated composite exhibited enhanced thermal stability, with a 5 °C increase in maximum degradation temperature (Tmax = 390 °C) and a 33% increase in residual char content (20% at 600 °C) compared to the untreated composites, confirming enhanced thermal resistance.

Strength and limitation of the study

The study provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing the fabrication of natural fiber hybrid composites. However, like any research, it possesess inherent strength and limitation.

-

The primary strength of this work is the application of an integrated Grey-Fuzzy logic. This method effectively handles the uncertainty and subjectivity in balancing multiples, often competing, mechanical performance goals (tensile, flexural and impact strength), providing a more robust and reliable optimization compared to tradition single response or Grey Relation Analysis methods.

-

The study simultaneously investigates the impact of both material composition parameter (fiber weight fractions, chemical treatment) and Key manufacturing process parameters (molding pressure and temperature). This provides a more complete understanding of the factors governing composite performance, which is often missing in studies that focus solely on material variables.

-

The findings are robustly validated through confirmation experiments, which showed a strong correlation between predicted and experimental results with minimal error (2.96%). Furthermore, statistical significance of the model was confirmed through ANOVA.

-

The optimization is supported by extensive characterization (SEM, FTIR, XRD, TGA) to elucidate the fundamental chemical, morphological, and thermal mechanisms behind the performance improvements, moving beyond statistical report.

The study was conducted within specific ranges of the chosen parameters (e.g., pressure upto 16 MPa), temperature up to 120 °C, while these were selected based on literature to prevent fiber degradation, exploring wider ranges or additional parameters (e.g., molding time, fiber length/orientation) could yield further insights.

Future applications

The findings and optimized model presented in this work have direct applications in the automotive and construction industries, where the developed kenaf/jute hybrid composite can be utilized to manufacture lightweight, non-structural components such as interior door panels, parcel shelves, headliners, architectural cladding, contributing to weight reduction and improved sustainability. For successful implementation, it is recommended that the optimal parameters set (A3B4C3D1E2) serves as robust baseline for scaling up production via compression molding. However, practitioners should conduct pilot runs to fine-tune parameters specific to their mold design and press characteristics. The future scope of this research should focus evaluating the environmental durability of these optimized composites, including their long-term performance under moisture, UV exposure, and thermal cycling. Furthermore, research can be extended by applying the established Grey-fuzzy framework to other natural fibers combinations, thermoplastic matrices, and additional performance matrices like wear resistance and acoustic properties. Finally, a detailed validate the life cycle assessment (LCA) would be invaluable to quantitatively validate the environmental benefits of composites produced with this optimized process. The integration of bio-based reinforcements not only reduces the environmental footprint but also aligns with Sustainable development goal (SDG) toward green manufacturing.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASTM:

-

American Society for Testing and Materials

- CO2 :

-

Carbon Dioxide

- DTG:

-

Derivative Gravimetric Analysis

- µDo (Zo):

-

FIE output

- FIE:

-

Fuzzy Interference Engine

- FL:

-

Fuzzy Logic

- GFL:

-

Grey Fuzzy Logic

- GFA:

-

Grey Fuzzy Analysis

- GFG:

-

Grey Fuzzy Grade

- GRA:

-

Grey Relational Analysis

- GRC:

-

Grey Relational Coefficient

- GRG:

-

Grey Relational Grade

- H:

-

High

- KF:

-

Kenaf Fiber

- L:

-

Low

- V:

-

Maximum operation

- M:

-

Medium

- MPa:

-

Megapascal

- ∧:

-

Minimum operation

- t:

-

Quality function

- Y:

-

Quantification factor

- SEM:

-

Scanning Electron Microscope

- SF:

-

Sisal Fiber

- S:

-

Small

- SGF:

-

Snake Grass Fiber

- NaOH:

-

Sodium Hydroxide

- SPF:

-

Sugar Palm Fiber

- J:

-

trail number

- TGA:

-

Thermo Gravimetric Analysis

- TL:

-

Triangular Membership Function

- VH:

-

Very High

- VL:

-

Very Low

- VVH:

-

Very Very High

- VVL:

-

Very Very Low

- \(\:{y}_{i}\) :

-

Overall GRG

- \(\:\eta\:\) :

-

Total number of output results

- Δmin:

-

Minimum value of the absolute difference

- Δmax:

-

Maximum value of the absolute difference

References

Gideon, R. & Atalie, D. Mechanical and water absorption properties of jute/palm leaf Fiber-Reinforced recycled polypropylene hybrid composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 1–8 (2022).

Kir, M. et al. Extracting and characterizing of a new vegetable lignocellulosic fiber produced from C. humilis palm trunk for renewable and sustainable applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 281, 136495 (2024).

Atoui, S. et al. Extracting and characterizing novel cellulose fibers from Chamaerops humilis rachis for textiles’ sustainable and cleaner production as reinforcement for potential applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 276, 134029 (2024).

Meddour, A., Belaadi, A., Boumaaza, M., Bourchak, M. & Ghernaout, D. Enhancing Syagrus Romanzoffiana lignocellulosic fibers’ properties by ecological treatment with sodium bicarbonate for applications in sustainable lightweight biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 298, 140062 (2025).

Benarab, M., Belaadi, A., Bedjaoui, A., Boumaaza, M. & Ghernaout, D. Characterizing novel cellulosic fibers extracted from vicia Faba plant waste stems as a promising reinforcement for applications in sustainable textile and lightweight biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 307, 141940 (2025).

Teyar, S. et al. Analyzing the Strelitzia juncea cellulosic fibers mechanical properties’ experimental data using various statistical methods. J. Nat. Fibers. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2024.2394142 (2024).

Hadou, A., Belaadi, A., Alshahrani, H. & Khan, M. K. A. Extraction and characterization of novel cellulose fibers from Dracaena Draco plant. Mater. Chem. Phys. 313, 128790 (2024).

Gheribi, H. et al. Statistical study of the mechanical behavior of the new fiber from the Strelitzia juncea plant fibers: application in ecological yarns. J. Nat. Fibers. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2024.2396905 (2024).

Lalaymia, I., Belaadi, A., Bedjaoui, A., Alshahrani, H. & Khan, M. K. A. Extraction and characterization of fiber from the flower stalk of the Agave plant for alternative reinforcing biocomposite materials. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 32271–32287 (2024).

Mokhena, T. C., Mtibe, A., Mokhothu, T. H., Mochane, M. J. & John, M. J. A review on Bast-Fibre-Reinforced hybrid composites and their applications. Polym. (Basel). 15, 3414 (2023).

Mohammed, M. et al. Comprehensive insights on mechanical attributes of natural-synthetic fibres in polymer composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 25, 4960–4988 (2023).

Saha, A. & Kumari, P. Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa Tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites. Polym. Compos. 44, 2449–2473 (2023).

Sharma, H. et al. Critical review on advancements on the fiber-reinforced composites: role of fiber/matrix modification on the performance of the fibrous composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 2975–3002 (2023).

Vinod, A. et al. Jute/Hemp bio-epoxy hybrid bio-composites: influence of stacking sequence on adhesion of fiber-matrix. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 113, 103050 (2022).

Muthalagu, R., Srinivasan, V., Sathees Kumar, S. & Krishna, V. M. Extraction and effects of mechanical characterization and thermal attributes of jute, prosopis Juliflora bark and Kenaf fibers reinforced bio composites used for engineering applications. Fibers Polym. 22, 2018–2026 (2021).

Rashid, B. et al. Improving the thermal properties of olive/bamboo fiber-based epoxy hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 43, 3167–3174 (2022).

Khan, T., Sultan, M. T. H., Shah, A. U. M., Ariffin, A. H. & Jawaid, M. The effects of stacking sequence on the tensile and flexural properties of kenaf/jute fibre hybrid composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 18, 452–463 (2021).

Ghori, S. W., Rao, G. S. & Rajhi, A. A. Investigation of physical, mechanical properties of treated date palm fibre and Kenaf fibre reinforced epoxy hybrid composites. J. Nat. Fibers. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2022.2145406 (2023).

Devarajan, B. et al. Recent developments in natural fiber hybrid composites for ballistic applications: a comprehensive review of mechanisms and failure criteria. Facta Universitatis, Series: Mechanical Engineering 343 (2024).

Sasi Kumar, M. et al. Effect of various manufacturing techniques on mechanical properties of Biofiber-Reinforced composites. In: Sustainable Machining and Green Manufacturing. Editor(s): S. Thirumalai Kumaran, and Tae Jo Ko. Wiley (2024).

Rubio-López, A., Olmedo, A., Díaz-Álvarez, A. & Santiuste, C. Manufacture of compression moulded PLA based biocomposites: A parametric study. Compos. Struct. 131, 995–1000 (2015).

Rangaswamy, H., Gowdru Chandrashekarappa, M. H. H., Pimenov, M. P., Giasin, D. Y., Wojciechowski, K. & S Experimental investigation and optimization of compression moulding parameters for mwcnt/glass/kevlar/epoxy composites on mechanical and tribological properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 327–341 (2021).

Manalu, J. et al. Characterization of eco-friendly composites for automotive applications prepared by the compression molding method. Polym. Compos. 45, 8104–8118 (2024).

Maji, P. et al. Characterization of effective permeability of Prepreg fibers under autoclave molding process conditions using process model simulations. J. Text. Inst. 112, 1–7 (2021).

Yallew, T. B., Kassegn, E., Aregawi, S. & Gebresias, A. Study on effect of process parameters on tensile properties of compression molded natural fiber reinforced polymer composites. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 338 (2020).

Ying, Q. et al. Effect of molding process parameters on the mechanical properties of CGFRPP products. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 38, 2949–2959 (2024).

Jaafar, J., Siregar, J. P., Tezara, C., Hamdan, M. H. M. & Rihayat, T. A review of important considerations in the compression molding process of short natural fiber composites. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 105, 3437–3450 (2019).

Karuppiah, G. et al. Tribological analysis of jute/coir polyester composites filled with eggshell powder (ESP) or nanoclay (NC) using grey rational method. Fibers 10, 60 (2022).

Hiwa, B., Ahmed, Y. M. & Rostam, S. Evaluation of tensile properties of Meriz fiber reinforced epoxy composites using Taguchi method. Results Eng. 18, 101037 (2023).

Alshukur, M. Review of optimisation of advanced textiles using the design of experiment methodology: part II: fibre-reinforced polymer composites and advanced treatments of textiles. Multiscale Multidisciplinary Model. Experiments Des. 8, 102 (2025).

Binoj, J. S. et al. Taguchi’s optimization of Areca fruit husk fiber mechanical properties for polymer composite applications. Fibers Polym. 23, 3207–3213 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Optimization of compression molding parameters and lifecycle carbon impact assessment of bamboo Fiber-Reinforced polypropylene composites. Polym. (Basel). 16, 3435 (2024).

He, L. et al. Optimization of molding process parameters for enhancing mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 42, 446–454 (2023).

Thanikodi, S., Rathinasamy, S. & Solairaju, J. A. Developing a model to predict and optimize the flexural and impact properties of jute/kenaf fiber nano-composite using response surface methodology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 136, 195–209 (2025).

Chauhan, S. & Gope, P. C. Optimization of mode-I fracture toughness using the Taguchi method in cellulosic fiber‐ Grewia optiva reinforced biocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.54395 (2023).

Mann, G. S. et al. Effect of process parameters on the fabrication of hybrid natural fiber composites fabricated via compression moulding process. J. Nat. Fibers. 19, 14803–14812 (2022).

Murugan, A., Selvaraj, S., Sivanantham, G. & Ponnambalam, A. Taguchi fuzzy multi-response optimization of process parameters in compression molding of natural hybrid composite. Iran. Polym. J. 32, 811–828 (2023).

Kafaltiya, S. et al. Multi-response optimization of characteristics for graphite reinforced biodegradable < scp > pva ‐fumaric acid cross‐linked composite: A gray‐fuzzy logic‐based hybrid approach. J. Vinyl Add. Tech. 30, 1190–1206 (2024).