Abstract

Bullets, shot, and other projectiles from firearms can fragment inadvertently when they strike a target. The fragmentation process is concerning for hunting, where the projectiles are often lead-based, and the targets are animals that will likely be ingested by people and/or scavenging wildlife. Medical radiography (lab-based polychromatic X-ray imaging instruments routinely used in hospitals and for dental exams) has been the most widespread and accepted method to reveal these fragments within thick, hydrated tissue sections. It is also deployed at some food banks to screen packages of donated game meat for lead contamination in the form of projectile fragments. We present the first synchrotron-based X-ray images of rifle and shotgun wounds in biological tissue from hunted wild game animals, and contrast them against medical radiographs. Micro- and nanoscale fragments, undetectable in medical radiographs, were directly observed within tissue for the first time and conclusively identified as lead using X-ray absorption and emission spectroscopies. The mass of just those lead fragments that were below the detection limit of medical radiography was quantified and found to exceed levels set by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for protection of human health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fragmentation of projectiles from firearms within living tissue has been observed for over 100 years1. The topic has taken on new significance in the context of hunting, because the element lead is commonly used for hunting bullets and shot2. Projectiles from firearms must transfer a certain level of energy to at least penetrate the target and be effective over long distances. Due to the high speeds and forces required, fragmentation of the metallic projectiles is often observed within the target animals, including deer3,4, birds5,6, or other hunted game7,8, even though most types are designed to hold together and not fragment. Consumption of hunted game meat or the remains of harvested animals with embedded lead fragments is an established lead exposure pathway that continues to negatively impact human and wildlife health worldwide2.

Medical X-ray imaging instruments, primarily radiography1,3,5,7,8,9,10 and computed tomography4,6, have been the dominant tools to reveal the projectiles and their fragments embedded within thick, hydrated tissue sections. These instruments typically have a large field of view to investigate whole limbs and organs, but in imaging and microscopy, field of view is inversely proportional to magnification. In addition, these instruments have relatively large X-ray source sizes, short source-to-sample distances, and the X-rays that produce the image are polychromatic. As a result, medical X-ray imaging instruments rarely have a minimum spatial resolution better than 0.1 mm half pitch (5 line pairs/mm)11, which is about equal to unaided human vision. Millimeter to sub-millimeter scale fragments are commonly observed within gunshot wounds using these instruments, but not smaller1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The possibility of firearm projectiles shedding micro- or even nanoscale fragments within biological tissue is largely unexplored, and to our knowledge the process has never been directly observed because the lab-based X-ray imaging methods previously applied did not have the spatial resolution necessary to answer the question. There are however several other established X-ray imaging techniques that have much higher spatial resolution and can penetrate through thick hydrated tissue samples, but they have not been applied to this problem until now. Our motivation was to apply these advanced imaging methodologies to (1) observe whether or not projectile fragmentation well below 0.1 mm occurs within biological tissues under real hunting conditions, and if they are resolvable, (2) to quantify the amount of lead contained within these previously invisible fragments. Recently, we applied synchrotron X-ray imaging with significantly higher spatial resolution to bullet fragmentation within ballistic gelatin, a tissue simulant material12. Here we extend synchrotron X-ray imaging to bullet as well as shot impacts on real biological tissues from hunted wild game, and to even higher spatial resolution using scanning X-ray and scanning electron microscopes coupled with energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence detection. These results are directly compared against medical radiographs, demonstrating how harmful amounts of lead in the form of micro- and nanoparticles or fragments can be present within tissues of animals struck by lead ammunition while being undetectable by medical radiography.

Results

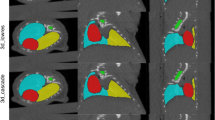

X-ray images of an excised rib cage section of a white-tailed deer impacted by a lead-core bullet (55% w/w lead) from a rifle under real hunting conditions are presented in Fig. 1. A medical radiograph (Fig. 1a) of the impact area revealed numerous highly absorbing (radio-dense) fragments. This example displays the typical fragmentation of lead-core hunting bullets in tissue and tissue simulants which has been reported in dozens of previous studies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,12. A lead K edge subtracted (KES) image of a region of this sample in the same orientation is presented in Fig. 1b. Briefly, monochromatic X-ray images of the sample were collected at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron13, at 88.8 keV and 86.8 keV, above and below the lead 1s electron or K shell absorption edge. Then the 86.8 keV image was subtracted from the 88.8 keV image, which removes the absorption contribution from all non-lead objects from the image12.

X-ray images of a 7 mm-08 lead-core bullet impact on the rib cage of a white-tailed deer. (A) Medical radiograph. Four rib bones are oriented vertically in this image. (B) Synchrotron-based lead K edge subtracted image of the sample region indicated by the red dashed rectangle within (A). (A) and (B) are on the same spatial scale. Supplementary Fig. 1 contains a high resolution X-ray projection image of the area indicated by the blue dashed rectangle within (A).

Both the KES image and the medical radiograph are X-ray images. The key difference is the contrast mechanism: the former requires monochromatic X-rays tuned to the region near an inner shell electron absorption edge (lead K in this study), while the latter only requires polychromatic X-rays which can be generated by commercially available lab sources based on electron impact. The contrast in the radiograph (Fig. 1a) is proportional to density and thickness variations from all elements in the sample, whereas the contrast in the KES image (Fig. 1b) is specific and quantitative for lead only. The KES technique allows for conclusive identification and quantification of lead in-situ, and at higher spatial resolution well beyond lab-based medical radiography. The KES image was thresholded at the Rose criterion (signal to noise ≥ 5, where noise is the standard deviation of absorption values from image regions which do not contain lead)14, and the area of each fragment was tabulated, then converted to a mass of lead assuming a spherical shape. 1809 fragments were counted within the imaged area (Fig. 1b), totaling 847 mg of lead. 1626 of the fragments had a diameter less than 150 μm, and those accounted for 2.0 mg, or 2.4%, of the total lead mass. Lastly, the CLS synchrotron beamline was reconfigured for high resolution X-ray imaging at 30 keV. A 17.5 mm × 28.8 mm region of this sample was imaged, indicated by the blue dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a, revealing many more fragments with diameters less than 10 μm (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Images of the breast of a sharp-tailed grouse impacted by lead shot from a shotgun under real hunting conditions are presented in Fig. 2. The photograph (Fig. 2a) reveals six perforations in the bottom half of the breast from the #6 lead shot used, all of which passed through this region intact: no pellets were observed in a medical radiograph of this sample (Fig. 2b). Upon close inspection of the radiograph, we observed a single suspicious object (Fig. 2c). The object was right at the resolution and contrast limits of the instrument: just 4 pixels of the object were distinguished from the surrounding tissue by the Rose criterion (signal to noise = 7.5, 6.5, 5.8 and 5.2). Although we do have a priori information that the projectiles that struck the grouse were only lead (unlike the rifle bullets), there is no evidence within the radiograph alone to conclude this is a lead fragment, as medical radiographs (i.e., two-dimensional polychromatic X-ray projection images) do not contain elemental information15.

Images of several #6 lead shot impacts on a sharp-tailed grouse breast. (A) Photograph. (B) Medical radiograph. The white arrow indicates the location of a sub-millimeter scale suspicious object. (A) and (B) are the same object from the same perspective and are on the same spatial scale. (C) Digital zoom in on the suspicious object within the medical radiograph (B). (D) High resolution X-ray projection image at 30 keV of the suspicious object, now resolved as a cluster of micro-scale lead fragments. (C) and (D) are the same object from the same perspective and are on the same spatial scale.

A KES image was collected of the same sample (Supplementary Fig. 2). The object displayed significant contrast in the KES image, which provides proof, rooted in X-ray absorption spectroscopy, that the object contains lead. The higher spatial resolution of the KES configuration, relative to the medical radiograph, resolved additional lead fragments in the immediate area. The CLS beamline was again reconfigured for high resolution X-ray imaging at 30 keV, and a sub-region of this sample indicated by the arrow in Fig. 2b was interrogated at 1.6 μm half pitch spatial resolution, presented in Fig. 2d. Now numerous lead fragments could be resolved, and the area in which fragments could be clearly resolved by the Rose criterion increased to about 5 mm V × 3 mm H (Supplementary Fig. 3). Even the oriented myofibril (1–2 μm diameter) structure of the breast muscle tissue is resolved in Fig. 2d, owing to phase-shift contrast. We resolved 159 fragments within the Rose criterion thresholded high resolution X-ray projection images. The thresholded area of each fragment was converted to a mass of lead assuming a spherical shape, for a combined total of 131 µg of lead within this sample.

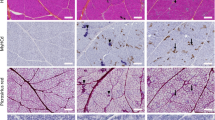

As magnification increased, smaller fragments were revealed and in increasingly greater number. The high-resolution X-ray projection images were collected near the minimum possible spatial resolution of the CLS beamline, which is ultimately limited by factors including penumbral blurring, Compton scattering, and the finite scintillator thickness of the detector11. However, higher spatial resolution can be achieved with X-rays using scanning X-ray microscopes16. In these instruments, a Fresnel zone plate lens is used to focus monochromatic X-rays to a small spot (about 100 nm being state of the art), and then the sample is raster scanned to build up an image one line at a time. Multi-channel detection is common, including combined X-ray transmission and energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence. We imaged two thin sections (~ 0.5 mm) of gunshot samples using X-ray microscopes at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) synchrotron16, and the results are presented in Fig. 3. Scanning X-ray micrographs of a tissue section of the deer rib sample, taken from within the region indicated by the blue dashed rectangle in Fig. 1a, are presented in Fig. 3a (X-ray transmission) and Fig. 3b (X-ray fluorescence, lead Lɑ1). Although the focus of this work is imaging fragments within biological tissue, we also measured a thin section of ballistic gelatin extracted from a block impacted by a lead-core bullet from our previous study12 (sample details reproduced in Supplementary Material), and present these images as Fig. 3c (X-ray transmission) and Fig. 3d (X-ray fluorescence, lead Lɑ1). Many micro- and nanoscale fragments were easily resolved in both samples. The X-ray fluorescence spectra of these objects (not shown) was dominated by a peak at 10.55 keV, which corresponds to the characteristic Lɑ1 emission line of lead.

Scanning X-ray micrographs reveal nanoscale lead fragments. (A) Deer rib tissue impacted by a lead-core bullet in (A) transmission at 13.7 keV, and (B) lead Lɑ1 X-ray emission. (A) and (B) are on the same spatial scale. (C) Ballistic gelatin impacted by a lead-core bullet in (C) transmission at 14.0 keV, and (D) lead Lɑ1 X-ray emission. (C) and (D) are on the same spatial scale.

Scanning electron micrographs were also collected from the deer rib tissue and are presented in Fig. 4. In these instruments, electromagnetic lenses are used to focus and raster scan a single-digit nanometer sized beam (about 1 nm being state of the art) over a stationary sample, and multi-channel detection is common. Bullet fragments with diameters as small as 50 nm were readily located using backscatter detection (Fig. 4a), owing to the naturally very high contrast of the metallic fragment material relative to the surrounding tissue which primarily contains light elements. Fragments were also resolved in the secondary electron images of the same regions (Fig. 4b). It must be mentioned that electrons have a much stronger interaction with matter relative to X-rays, and this manifests in a much lower penetration depth. We calculated the penetration depth to be 6.7 μm for our sample and imaging conditions, using the program CalcZAF17. Therefore, only those fragments within a few micrometers of the sample surface are observable in the scanning electron microscope. X-ray fluorescence spectra were collected from six sub-micrometer diameter fragments, and a typical spectrum is presented in Fig. 4c. All spectra collected from the suspect fragments displayed the characteristic L and M series emission peaks of lead as the strongest features. All spectra also contained emission peaks characteristic of nitrogen, oxygen, sodium, phosphorus, chlorine, potassium and calcium. These were found to be the main peaks/elements of the surrounding deer rib tissue in regions where no high contrast fragments were observed. Emission peaks characteristic of copper (bullet jacket material) were not observed in any of the fragments or surrounding tissue. The absence of copper fragments agrees with previous observations involving copper coated and monolithic copper projectiles3,9,12,18. When the entire mass of a hunting projectile is contained and collected after impact, macroscopic visual observations reveal a strong tendency for the copper portion to remain in one deformed mass or just a few millimeter scale fragments18, as might be expected from the large difference in Young’s modulus between copper and lead. Our data indicate this macroscopic tendency likely remains true at the micro- and nanoscale.

Scanning electron micrographs of a cluster of lead nanoparticles embedded within deer rib tissue struck by a lead-core hunting bullet, collected with (A) backscatter, and (B) secondary electron detection. (A) and (B) are on the same spatial scale. (C) An energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrum collected from one of the fragments. Lead emission peaks dominate the spectrum.

Discussion

Researchers in both medical and environmental fields have long suspected that lead-based firearm projectiles might produce lead fragments that are so small they are essentially lead “dust”5. To our knowledge this is the first time such tiny lead fragments, more than three orders of magnitude smaller than 0.1 mm diameter, have been directly observed within any biological tissue including hunted game meat. Gunshot residue ejected from the muzzle of a gun upon firing can contain lead-rich micro- to nanoparticles, and scanning electron microscopy is an accepted forensic method for analysis of gunshot residue on surfaces in the vicinity of gunshot wounds19. But those investigations concern extremely close range shots of less than 2 m, which do not reflect real hunting situations. In our study, the impacts occurred 20 m and 100 m from the muzzle. We also used multiple techniques from millimeter to nanometer spatial resolution, proving that the lead micro- and nanoparticles observed here originate from projectile fragmentation, not gunshot residue. One previous investigation detected lead nanoparticles in game meat using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry10, but this technique is arguably not well suited for the problem. It requires totally destructive sample preparation, from bulk tissue down to a homogenous liquid. The authors show the sample preparation affected the particle size measured, and contributed to a large background signal from fully dissolved lead. They suggested “formation of PbNPs [lead nanoparticles] in the sample introduction system”10 was a possibility. Lastly, the measurement could not distinguish if the time resolved high count signals arose from singular lead objects, or aggregate clusters of small particles. X-ray imaging on the other hand requires no sample preparation and the measurement is non-destructive. Medical radiography is widely available and often portable. The measurement is fast and provides a large field of view. Bullet and shot fragments can be easily resolved, but there are limitations with spatial resolution and elemental specificity. We demonstrated these limitations, and then overcame them using advanced forms of X-ray imaging instruments at two synchrotrons, and a modern environmental scanning electron microscope. Of course, these alternative techniques have their own limitations. For synchrotron X-rays, the major limitation is the highly competitive access at a handful of possible facilities worldwide. This fact greatly limited the number of tissue samples that could be investigated in this study. However, the medical radiographs of these samples are comparable with those presented in many previous reports1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,12 and therefore are considered representative for the two types of projectiles investigated. Our report contains the first application of synchrotron X-rays to rifle and shotgun wounds in biological tissue. Environmental scanning electron microscopy is becoming widely available and has extremely high spatial resolution, but as previously mentioned, the major limitation is the micrometer-level penetration depth of electrons in biological tissues, likely to result in a severe under-estimation of lead embedded within a thick tissue sample.

Our results prove that lead micro- and nanoparticles can be produced within both rifle and shotgun wounds of wild game harvested under actual hunting conditions. We expect these observations would also translate to gunshot injuries in humans when similar lead-based ammunition is involved9. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has set a blood lead reference value of 3.5 µg/dL to identify children with elevated blood lead levels. On a population level, a daily dietary intake of 22 µg/day for children age 1–6, and 88 µg/day and women of childbearing age, is required to reach 3.5 µg/dL20. Because the conversion of dietary lead to blood lead has many known variables21, interim reference levels were set ten times lower (2.2 and 8.8 µg/day), and these serve as “benchmark[s] to evaluate whether lead exposure from food is a potential concern”20. One sphere of lead with a diameter of 154 μm has a mass of 22 µg. Such an object is right at the resolution and contrast limits of medical radiography (Fig. 2c), and much smaller fragments were resolved within the tissue samples in this study. In both the deer and grouse samples, the mass of just those lead fragments which are smaller than the resolution limit of medical radiography exceeded the CDC interim reference levels for children by factors of 909 and 60, respectively. These results agree with our earlier hypothesis12 regarding the limited effectiveness of screening donated game meat at food banks for lead using medical radiography22. Meat that contains lead will pass this test if the fragment sizes are below the minimum spatial resolution (false negative), and meat that contains radio-dense objects which are not lead might fail this test because the measurement does not contain element-specific information (false positive)15. Indeed, rates of both false negatives and false positives were found to exceed 30% in two recent studies where butchered game meat samples were tested by both medical radiography and mass spectrometry7,8. Therefore, it may be common that harmful amounts of lead exist as sub-0.1 mm diameter fragments within game meat harvested with lead ammunition, even when larger fragments are not observed in medical radiographs of the same sample.

As noted earlier, our measurements of the mass of lead contain a spherical approximation to calculate fragment volumes from 2D projections. This approximation could result in an over or underestimate of the amount of lead present, because for example, fragments are frequently observed to be irregularly shaped (Figs. 1 and 2)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,12,18. X-ray tomography (combining multiple 2D projections over an angular range) is an inherently more accurate measurement of object volume. Polychromatic versions have been previously applied to bullet4 and shot6 fragmentation, but with polychromatic X-rays, bigger assumptions must be made about the elemental composition of the high-contrast objects observed12. The BMIT-ID beamline13 that we used for the measurements of lead mass routinely performs monochromatic X-ray tomography, and would be possible to collect a lead KES tomogram with micrometer scale spatial resolution, avoiding both the spherical approximation and any assumptions about elemental composition. All that considered, even if we assume the spherical approximation in our study resulted in an improbable 10× overestimation of the mass, the amount of previously invisible lead would still exceed CDC interim reference levels for children multiple times over for both samples and would not change any of our major findings. Projectile fragments are primarily distributed within tissue as a result of the physical forces generated on impact. For big game hunting with rifles, the majority of fragments (~ 95%) are distributed within a 16 cm radius of the bullet path4. Experiments injecting solutions of metallic nanoparticles into the tail vein of mice show they can be transported throughout those animals23. 5 μm to 25 μm diameter micro-plastic particles have been recently observed throughout the human body, including within brain tissue24. Considering that lead projectile fragments are produced in tissue which are the size of erythrocytes and smaller, this fraction could conceivably experience some secondary distribution via the circulatory system of a hunted animal in its final moments12.In addition, the smaller lead fragments have been shown to be more bio-available: (1) a fivefold enhancement of absorption of lead was observed in rats for 6 μm mean diameter particles compared to 197 μm particles25. (2) Vaporized lead particles less than 100 nm diameter were almost totally absorbed by human lungs, whereas 40% of those 900 nm and larger were trapped in upper airways and swallowed26. (3) A related study of body lead burden from retained bullets revealed a significant increase in body lead in cases where the gunshot was associated with a bone fracture. The authors hypothesized that the bone strike divided the bullet into smaller pieces, leading to more rapid absorption by the body9. Several other conditions are known to affect the conversion of dietary lead to blood lead21, but nanoscale aspects (shape and aspect ratio, surface coating, crystallinity, agglomeration state, etc.) for metallic lead are not yet understood. It remains to be determined the maximum extent that the micro- and nanometer scale fragments are distributed in hunted game, and more importantly, what role they play in harm versus millimeter scale fragments.

Methods

Sample preparation

Butchered portions of two wild game animals were donated to this study by licensed hunters in Saskatchewan, Canada. No animals were killed for the purpose of this research. The two animals were hunted in an ethical and lawful way, and the edible remaining portions not used in this study were intended for human consumption. The sample size of two was decided on due to the highly competitive nature of synchrotron beamtime and the limited amount of time awarded to this project. The two species/samples were chosen because (1) they were available without killing for the purpose of this research, and (2) they are representative of a common wild big game animal and a common wild game bird in North America. No criteria was set for including or excluding animals, and there were no exclusions. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the health and safety committees of the Canadian Light Source under proposals 012465 and 014759, and the Advanced Photon Source under proposal 82694. All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and have been approved by the appropriate institutional committees. The details included for reporting this animal research follow ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

A wild adult male white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) was harvested with a rifle at a distance of 100 m. The deer tested negative for chronic wasting disease. Other details of age, history, and health status were unknown. The cartridge was a 7 mm-08 Winchester Ballistic Silvertip (SBST708). The projectile was a 9.07 g (140 grain) bullet, with a lead core enclosed inside a thin copper jacket (“cup-and-core” construction) and a polymer tip. Muzzle velocity was advertised as 844 m/s. We found these bullets contained 4.99 g of lead (55% w/w) by weighing five of them before and after heating above 400˚C to melt out the lead core. Thin tissue sections approximately 0.5 mm thick were created by excising small amounts of tissue using a clean scalpel, then pressing them flat between two clean glass microscope slides, followed by air drying. No sample coatings or stains were applied for any of the subsequent imaging procedures.

A wild adult male sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus) was harvested with a shotgun at a distance of 20 m. Its age, history, and health status were unknown. The cartridge was a 12 gauge 70 mm (2 ¾”) Winchester Super Speed Upland Game & Target (WHS126). The projectiles were 28.3 g (1 oz.) of 2.79 mm diameter (#6) lead balls, commonly referred to as pellets or shot. Muzzle velocity was advertised as 411 m/s.

Medical radiographs

Radiographs were acquired using a Carestream DRX-Revolution portable digital machine at the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon, Canada. The instrument contained a tungsten anode X-ray tube operated at 150 kV and 58.8 mA tube current. A pre-filter of 1.0 mm aluminum and 0.1 mm copper was used in addition to the mandated 2.5 mm aluminum filter. The source to detector distance was 1.0 m, and the samples rested directly on the detector during imaging. The detector was a DRX Plus 3543 C with 12-bit dynamic range. It consisted of a thallium doped cesium iodide scintillator layer over an amorphous silicon sensor, 2520 × 3032 pixels of 139 μm × 139 μm size. The exposure time for each image was 10.2 ms (0.6 mAs). The minimum spatial resolution of the radiographs is 139 μm half pitch (3.6 line pairs/mm).

Synchrotron X-ray projection imaging

Synchrotron X-ray projection imaging was performed at the BioMedical Imaging and Therapy Insertion Device (BMIT-ID) beamline13 at the CLS synchrotron in Saskatoon, Canada. The superconducting wiggler X-ray source was set to 2.5 T, and the source to sample distance was 57.8 m. The detector consisted of a thin scintillator foil, a 16-bit camera (PCO Edge 5.5) with 2560 × 2160 pixels of 6.5 μm × 6.5 μm, and variable optical zoom between the two. Two distinct configurations of the beamline were used: one for KES imaging, and one for highest spatial resolution imaging. For KES measurements, the sample to detector distance was 1.0 m, and the scintillator was 1000 μm thick cerium doped lutetium aluminum garnet from Crytur. Optical magnification of 0.24× was used to obtain an effective pixel size of 27.23 μm × 27.23 μm. The field of view was 69.71 mm H × 5.473 mm V (2560 pixels × 201 pixels). Exposure times were 200 ms at 88.8 keV, and 160 ms at 86.8 keV. The minimum half pitch spatial resolution for KES imaging was 27.2 μm (18.4 line pairs/mm).

For high resolution measurements, the photon energy was set to 30.00 keV, the sample to detector distance was reduced to 0.15 m, and the scintillator was 50 μm thick cerium doped lutetium aluminum garnet from Crytur. Optical magnification of 4× was used to obtain an effective pixel size of 1.625 μm × 1.625 μm, and a field of view of 4.160 mm H × 3.510 mm V. Exposure time was 500 ms per image. The minimum half pitch spatial resolution for high resolution imaging was 1.6 μm (307 line pairs/mm).

Synchrotron scanning X-ray microscopy

Scanning X-ray microscopy was performed at the APS synchrotron in Lemont, Illinois, USA. Two microscopes were used, at beamlines 2-ID-D (the Bionanoprobe16), and 2-ID-E. At 2-ID-D, the photon energy was set to 14.00 keV. The Fresnel zone plate lens had a 100 nm outermost zone width Δr, and 320 μm outer diameter D. The minimum half pitch spatial resolution was 122 nm (8200 line pairs/mm). Scan parameters at 2-ID-D were 100 nm × 100 nm pixels with 50 ms exposure time per pixel. For 2-ID-E, the zone plate parameters were 100 nm Δr, 240 μm D, the photon energy was 13.70 keV, and the minimum half pitch spatial resolution was 500 nm (2000 line pairs/mm). Scan parameters at 2-ID-E were 500 nm × 500 nm pixels with 10 ms exposure time per pixel. Both microscopes were equipped with a quadrant photodiode detector (IRD AXUV PS4C) and a silicon drift detector (Hitachi Vortex ME7), for simultaneous measurement of sample transmission and energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence at each pixel.

Environmental scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron micrographs were acquired with a Thermo Quattro S environmental scanning electron microscope at the Electron Imaging and Microanalysis Laboratory of the CLS. The instrument was operated in environmental mode with an atmosphere of 200 Pa water, an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, and a beam current of 0.13 nA. Secondary electron and backscattered electron images were acquired simultaneously, with a minimum half pitch spatial resolution of 1.3 nm (380000 line pairs/mm). X-ray fluorescence spectra of select regions of interest were collected using a Bruker XFlash 6–30 X-ray fluorescence detector, and analyzed using Bruker Esprit software.

Image processing

All X-ray and electron image processing including dark current subtraction, conversion to transmission and absorption, stitching multiple fields of view, and thresholding were performed in ImageJ version 1.54i27.

Data availability

Data are available on request from the corresponding author A.L.

References

Pupin, M. From Immigrant To Inventor 307–308 (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922).

Arnemo, J. M., Fuchs, B., Sonne, C. & Stokke, S. Hunting with lead ammunition: A one health perspective in Arctic One Health (ed. Tryland, M.) 439–468 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87853-5_21 (Springer, 2022).

Hunt, W. G. et al. Bullet fragments in deer remains: implications for lead exposure in avian scavengers. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 34(1), 167–170. https://doi.org/10.2193/0091-7648(2006)34[167:BFIDRI]2.0.CO;2 (2006). )34[167:BFIDRI]2.0.CO;2.

Haase, A. et al. Analysis of number, size and spatial distribution of rifle bullet–derived lead fragments in hunted roe deer using computed tomography. Discover Food. 3, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-023-00052-w (2023).

Frank, A. Lead fragments in tissues from wild birds: A cause of misleading analytical results. Sci. Total Environ. 54, 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(86)90272-X (1986).

Green, R., Taggart, M., Pain, D. & Smithson, K. Implications for food safety of the size and location of fragments of lead shotgun pellets embedded in hunted carcasses of small game animals intended for human consumption. PLoS ONE. 17(8), e0268089. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268089 (2022).

Buenz, E. J. et al. X-ray screening of donated wild game is insufficient to protect children from lead exposure. Discover Food. 4, 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44187-024-00104-9 (2024).

Hampton, J. O., Pain, D. J., Buenz, E., Firestone, S. M. & Arnemo, J. M. Lead contamination in Australian game meat. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res. 30, 50713–50722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25949-y (2023).

McQuirter, J. L. et al. The effects of retained lead bullets on body lead burden. J. Trauma: Injury Infect. Crit. Care. 50(5), 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200105000-00020 (2001).

Kollander, B., Widemo, F., Ågren, E., Larsen, E. H. & Loeschner, K. Detection of lead nanoparticles in game meat by single particle ICP-MS following use of lead-containing bullets. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 409, 1877–1885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-0132-6 (2017).

Huda, W. & Abrahams, R. B. X-ray-based medical imaging and resolution. Am. J. Roentgenol. 204(4), W393–W397. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.13126 (2015).

Leontowich, A. F. G., Panahifar, A. & Ostrowski, R. Fragmentation of hunting bullets observed with synchrotron radiation: lighting up the source of a lesser-known lead exposure pathway. PLoS ONE. 17(8), e0271987. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271987 (2022).

Gasilov, S. et al. Hard X-ray imaging and tomography at the biomedical imaging and therapy beamlines of Canadian light source. J. Synchrotron Rad. 31, 1346–1357. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577524005241 (2024).

Rose, A. Vision: Human and Electronic, 8–11 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2037-1 (Plenum Press, 1973).

Röntgen, W. C. On a new kind of rays. Nature 53, 274–276. https://doi.org/10.1038/053274b0 (1896).

Chen, S. et al. The bionanoprobe: hard X-ray fluorescence nanoprobe with cryogenic capabilities. J. Synchrotron Rad. 21, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577513029676 (2014).

Armstrong, J. T., Donovan, J. J. & Carpenter, P. C. CALCZAF, TRYZAF and CITZAF: The use of multi-correction-algorithm programs for estimating uncertainties and improving quantitative X-ray analysis of difficult specimens. Microsc. Microanal. 19(S2), 812–813. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927613006053 (2013).

McTee, M., Parish, C. N., Jourdonnais, C. & Ramsey, P. Weight retention and expansion of popular lead-based and lead-free hunting bullets. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166288 (2023).

Kieser, J. A. et al. Morphoscopic analysis of experimentally produced bony wounds from low-velocity ballistic impact. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 7, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-011-9240-y (2011).

Flannery, B. M. & Middleton, K. B. Updated interim reference levels for dietary lead to support FDA’s closer to zero action plan. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 133, 105202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2022.105202 (2022).

Flannery, B. M. et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference levels for dietary lead exposure in children and women of childbearing age. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 110, 104516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104516 (2020).

Totoni, S. et al. Biting the bullet: A call for action on lead-contaminated meat in food banks. Am. J. Public. Health Supplement. 112(S7), S651–S654. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307069 (2022).

Sykes, E. A., Dai, Q., Tsoi, K. M., Hwang, D. M. & Chan, W. C. W. Nanoparticle exposure in animals can be visualized in the skin and analysed via skin biopsy. Nat. Comm. 5, 3796. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4796 (2014).

Amato-Lourenço, L. F. et al. Microplastics in the olfactory bulb of the human brain. JAMA Netw. Open. 7(9), e2440018. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40018 (2024).

Barltrop, D. & Meek, F. Effect of particle size on lead absorption from the gut. Arch. Env Health. 34(4), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00039896.1979.10667414 (1979).

Kehoe, R. A. The metabolism of lead under abnormal conditions. J. Royal Inst. Public. Health Hygiene. 24(6), 129–143 (1961).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Kody Robert and Ryan Ostrowski are thanked for assistance with collecting the medical radiographs at the Royal University Hospital. Olga Antipova is thanked for training and assistance on the Advanced Photon Source 2-ID-E beamline. Siddhant Singh is thanked for suggesting the SEM measurements. Part of the research described in this paper was performed at the Canadian Light Source, a national research facility of the University of Saskatchewan, which is funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the National Research Council, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Government of Saskatchewan, and the University of Saskatchewan. This research also used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. conceived the study, provided the grouse sample, performed all sample preparation, and wrote the manuscript. K.G. provided the deer sample (Figs. 1, 3 and 4) and edited the manuscript. A.P. collected the synchrotron projection X-ray micrographs, and A.L. analyzed that data (Figs. 1 and 2). S.C. and A.L. collected the synchrotron scanning X-ray micrographs and analyzed that data (Figure 3). B.B. collected the scanning electron micrographs and analyzed that data (Figure 4). All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leontowich, A.F.G., Panahifar, A., Chen, S. et al. Lead micro- and nanoparticles directly observed within gunshot wounds in hunted game meat. Sci Rep 15, 36364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20285-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20285-2