Abstract

We evaluated the real-world efficacy of intravitreal faricimab for diabetic macular edema (DME) and its relationship with visual and retinal anatomical changes using optical coherence tomography. We retrospectively assessed 174 patients (214 eyes) with DME from 13 Japan Clinical REtina Study Group (J-CREST) sites who received ≥ 1 faricimab injection and were followed ≥ 6 months, and compared treatment-naïve (with no prior anti-VEGF treatment) and previously treated groups. Both groups showed significant improvements in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central subfield thickness (CST BCVA gain was greater in the treatment-naïve group (p = 0.0109), whereas CST reduction showed little difference (p = 0.31). Resolution of cystoid macular oedema, diffuse retinal thickening, and subretinal fluid (SRF) was observed in both groups. Resolution of inner nuclear layer (INL) oedema and SRF significantly correlated with ≥ 0.2 log MAR BCVA improvement in the treatment-naïve group (p = 0.043 and p = 0.022, respectively). Mean number of injections was comparable between groups. One case of anterior chamber inflammation occurred; however, no serious systemic events were observed. In conclusion, faricimab significantly improved visual and anatomical outcomes in DME, especially in treatment-naïve eyes. Early resolution of INL oedema and SRF may serve as a potential biomarker for visual prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a chronic complication of diabetes mellitus, is a leading cause of blindness worldwide and its prevalence is increasing rapidly1. Diabetic macular edema (DME) is characterized by fluid accumulation in the macula due to increased permeability of the retinal capillaries and is the primary cause of vision loss in DR. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), and inflammatory cytokines play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of DME2,3, and can be involved in both the non-proliferative and proliferative stages of DR, leading to irreversible visual impairment if left untreated.

Conventional treatments for DME, including panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) and focal photocoagulation (FPC) targeting microaneurysms in the macular area, and local steroid administration have certain limitations, and anti-VEGF therapy has emerged as the first-line treatment in recent years2,4,5. However, the burden of frequent anti-VEGF injections on patients’ finances and physical well-being, as well as cases of non-responsiveness, remain considerable challenges4. Faricimab, the first humanised bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting both VEGF-A and Ang-23, has demonstrated efficacy in improving both the functional and structural outcomes of DME in the YOSEMITE and RHINE randomised controlled trials (RCTs) by inhibiting angiogenesis and vascular hyperpermeability and promoting vascular stability6,7. However, unlike the strictly controlled conditions of RCTs with selected patient populations, there is lack of an established protocol for the management of DME in real-world clinical practice8, necessitating the implementation of individualised treatment strategies9. Studies on the efficacy of faricimab in anti-VEGF-resistant DME have shown conflicting results regarding significant improvements in the central subfield thickness (CST)10,11,12,13,14,15and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA)10,13,16 versus no significant improvement in BCVA12,14,15,17, highlighting its uncertain effectiveness in this setting. Therefore, evaluating the association between patient background characteristics, retinal anatomical changes, and visual acuity improvement may help in elucidating the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic efficacy of faricimab and enable more appropriate outcome assessments. DME is classified into cystoid macular oedema (CME), diffuse retinal thickening (DRT), and serous retinal detachment (SRD) patterns, often with overlapping features12,18,19,20. CME frequently involves fluid accumulation in the fovea, inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer plexiform layer (OPL)19. Studies on anti-VEGF agents other than faricimab have reported varying efficacy across these morphological subtypes20, emphasizing the growing importance of individualised treatment strategies based on optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings. However, data on the treatment effects of faricimab on intraretinal fluid (IRF)15,16, DRT16, and SRD12,15,21 in DME are limited. Moreover, no studies have comprehensively evaluated the pre- and post-treatment changes in the localisation of CME, DRT, subretinal fluid (SRF), structural alterations in the inner and outer retinal layers, or vitreomacular interface abnormalities, or whether these anatomical changes are associated with visual improvement. Therefore, we aimed to investigate OCT-based changes that could serve as markers of visual improvement by evaluating the presence or absence of fluids in various morphological subtypes of DME before and after faricimab treatment in treatment-naïve and previously treated eyes. Additionally, we sought to elucidate the real-world treatment selection and administration profiles for faricimab in DME.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of the patients

Between January 2021 and December 2023, 174 patients (214 eyes) with DME who received at least one intravitreal faricimab injection and were followed up for 6 months were included in this analysis. The right eye was treated in 106 cases and the left eye in 108 cases. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population.

Of the 214 eyes, 67 were treatment-naïve and 147 were previously treated. The mean age of the overall cohort was 64.1 years, with the previously treated group being significantly older than the treatment-naïve group (65 vs 62 years, p = 0.035). The majority of eyes were from men (133 eyes, 62%) compared to women (81 eyes, 38%). The mean glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was 7.91%, with no significant difference between the two groups. The distribution of DR severity stages (mild, moderate, severe, and proliferative diabetic retinopathy [PDR]) did not differ significantly between the groups.

Prior non-anti-VEGF treatments included local steroid administration in 48 eyes, with no significant difference between the groups (43 eyes were administered sub-Tenon’s capsule triamcinolone acetonide injections and five intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injections). Laser treatments (FPC and PRP) were significantly more prevalent in the previously treated group (FPC: 9.0% vs 35%, PRP: 43% vs 80%). A history of vitrectomy was present in 18% eyes, with a higher proportion in the previously treated group (21% vs 10%).

In the previously treated group, the interval since the last anti-VEGF injection was ≤ 2 months in 53% eyes and > 3 months in 47% eyes. Aflibercept was the most commonly used prior anti-VEGF agent (78%), followed by ranibizumab (16%) and brolucizumab (6.5%). The mean number of prior intravitreal injections was 2.6 (range 1–39) for ranibizumab, 7.8 (range 1–49) for aflibercept, and 0.16 (range 1–3) for brolucizumab.

Visual acuity

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in visual acuity over 6 months. The mean logMAR BCVA in the treatment-naïve group at baseline was 0.341 ± 0.319. Significant improvements were observed at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months (0.232 ± 0.265, 0.182 ± 0.253, 0.185 ± 0.270, and 0.179 ± 0.279, respectively; p < 0.01 for all time points, with p = 0.0001 at 6 months). In the previously treated group, the mean logMAR BCVA at baseline was 0.323 ± 0.312, with significant improvements at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months (0.288 ± 0.313, 0.271 ± 0.317, 0.276 ± 0.305, and 0.280 ± 0.314, respectively; p < 0.05 for all time points, with p = 0.048 at 6 months). Significantly greater improvements in visual acuity were observed in the naïve group than in the previously treated group at 6 months (p = 0.0109).

Changes in logMAR best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) over 6 months. Mean logMAR BCVA values are shown for treatment-naïve and previously treated eyes at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months following intravitreal faricimab treatment. Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in the BCVA from baseline at all post-treatment time points (p < 0.05 for all). At 6 months, BCVA improvement was significantly greater in the treatment-naïve group than in the previously treated group (p = 0.0109). Error bars indicate standard deviations. *indicates p < 0.05 versus baseline. Bracket with p = 0.0109 indicates a significant difference between groups at 6 months.

The proportion of eyes achieving a ≥ 0.2 logMAR improvement was significantly higher in the treatment-naïve group (22 eyes, 32.8%) compared to the previously treated group (22 eyes, 15.0%; p < 0.01). Similarly, ≥ 0.3 logMAR improvement was observed in 16 eyes (23.9%) in the treatment-naïve group and 10 eyes (6.8%) in the previously treated group (p < 0.001).

Central subfield thickness

Figure 2 shows the changes in the CST over 6 months. The mean baseline CST in the treatment-naïve group was 451.3 ± 147.9 μm, which decreased to 356.6 ± 99.7 μm, 338.6 ± 102.4 μm, 342.4 ± 107.2 μm, and 340.0 ± 116.4 μm at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months, respectively. In the previously treated group, the mean baseline CST was 435.6 ± 135.7 μm, decreasing to 369.6 ± 132.0 μm, 360.4 ± 129.0 μm, 367.6 ± 136.9 μm, and 355.5 ± 122.1 μm at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months, respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed in the improvement of CST between the two groups. The proportion of eyes with a ≥ 30% reduction in CST was not significantly different between the treatment-naïve (24 eyes, 35.8%) and previously treated groups (43 eyes, 29.3%; p = 0.31).

Changes in central subfield thickness (CST) over 6 months. Mean CST values (in μm) are shown for treatment-naïve and previously treated eyes at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months following intravitreal faricimab treatment. Both groups demonstrated significant reductions from baseline at all post-treatment time points (p < 0.01 for all). However, no significant difference in CST reduction was observed between the two groups at any time point, including at 6 months (p = 0.31). Error bars indicate standard deviations. ** indicates p < 0.01 versus baseline. Brackets with n.s. indicate no significant difference between groups.

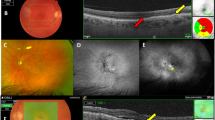

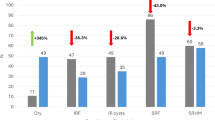

Fluid and retinal structural changes

Table 2 summarises the OCT findings, including the presence of intraretinal fluid (in the fovea, INL, OPL, and DRT), SRF, disorganisation of the retinal inner layers (DRIL), disruption of the ellipsoid zone (EZ), as well as the presence of epiretinal membrane (ERM) and vitreomacular traction (VMT) at baseline and 6 months. The OCT findings were categorised as follows: 0–0, absent both at baseline and 6 months; 0–1, newly appeared after treatment; 1–1, present both at baseline and 6 months; and 1–0, resolved after treatment. Figure 3 illustrates the proportions of eyes with fluid and other findings in each retinal layer at baseline and 6 months in the treatment-naïve and previously treated groups. CME (fovea, INL, and OPL), DRT, and SRF were significantly decreased at 6 months in both groups. No significant changes were observed in DRIL, EZ disruption, ERM, or VMT between baseline and 6 months in either group.

Changes in the retinal findings from baseline to 6 months in treatment-naïve and previously treated groups. The y-axis represents the percentage of eyes. Brackets with asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the treatment-naïve and previously treated groups at each time point (baseline or 6 months); p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; DRT, diffuse retinal thickening; SRF, subretinal fluid; DRIL, disorganisation of the retinal inner layers; EZ, disruption of the ellipsoid zone; ERM, epiretinal membrane; VMT, vitreomacular traction.

At baseline, SRF was significantly more prevalent in treatment-naïve eyes (p < 0.05) and EZ disruption was significantly more common in previously treated eyes (p < 0.05). A trend towards a higher prevalence of DRT was observed in treatment-naïve eyes at baseline (p = 0.06). At 6 months, INL and OPL oedema as well as EZ disruption were significantly more frequent in the previously treated group (p < 0.05). The proportion of eyes with subretinal fluid (SRF) decreased markedly following treatment: in the treatment-naïve group, SRF was present in 25.4% of eyes at baseline and decreased to 3.0% at 6 months; in the previously treated group, the proportion decreased from 12.9 to 1.4%. These findings indicate that SRF resolution occurred in the majority of cases in both groups.

In the treatment-naïve group, resolution of SRF (p = 0.022) and INL oedema (p = 0.043) were significantly correlated with a ≥ 0.2 logMAR improvement in visual acuity. No significant correlations were found between anatomical changes and visual acuity improvement in the previously treated group.

Number of injections

The mean number of faricimab injections during the 6-month observation period was 3.60 in the treatment-naïve group and 3.35 in the previously treated group.

IOP

The intraocular pressure (IOP) did not change significantly in either group from baseline to 6 months.

Switch and concomitant treatments

During the observation period, 28 eyes (six treatment-naïve [9.0%] and 22 previously treated [15.0%]) were switched from faricimab to another anti-VEGF agent (ranibizumab in eight eyes, aflibercept in 12 eyes, and brolucizumab in eight eyes). Reasons for switching included insufficient efficacy (n = 18), financial burden (n = 5), and other reasons (n = 5). Sub-Tenon’s capsule triamcinolone acetonide injection was administered to nine eyes (one treatment-naïve [1.5%] and eight previously treated [5.4%]).

Concomitant treatments initiated after faricimab administration included laser photocoagulation in 27 eyes (focal/grid photocoagulation in 16 eyes [three treatment-naïve, 13 previously treated] and PRP in 14 eyes [10 treatment-naïve, four previously treated]), vitrectomy in seven eyes (three treatment-naïve, four previously treated), cataract surgery in six eyes (all treatment-naïve), and glaucoma surgery in two eyes (both previously treated).

Safety

One case of mild anterior chamber inflammation was reported in the previously treated group, but no systemic adverse events were observed.

Discussion

This study investigated the real-world efficacy of faricimab in DME, along with the impact of local retinal anatomical changes on visual function in treatment-naïve and previously treated eyes. While the previously treated group exhibited a slightly older mean age, baseline HbA1c levels and DR stage were comparable between the groups. The prevalence of local steroid administration prior to the initiation of faricimab was similar between the treatment-naïve group (no prior anti-VEGF therapy) and the previously treated group (with a history of anti-VEGF therapy), whereas laser treatment (FPC or PRP) was significantly more frequent in the previously treated group.

BCVA significantly improved from the first month in both groups, with a greater magnitude of improvement observed in the treatment-naïve group. Consistent with previous reports6, lower baseline visual acuity was associated with poorer final visual acuity, underscoring the potential benefits of early intervention. Both groups also demonstrated significant reductions in the CST. Notably, the treatment-naïve group showed a marked visual acuity gain in the second month, suggesting a more direct correlation between anatomical changes and functional recovery in these eyes.

CME has been attributed to Müller cell degeneration and leakage from retinal microaneurysms, with the severity of oedema correlating with the abundance of microaneurysms in the deep capillary plexus (DCP)19,22. The higher residual fluid rate in the INL and OPL in the previously treated group compared to the treatment-naïve group, despite comparable foveal fluid changes, suggests a propensity for persistent anatomical alterations in the deeper retinal layers of the eyes that underwent prior treatment. The significant correlation observed between INL fluid resolution and ≥ 0.2 log MAR BCVA improvement in the treatment-naïve group implies that the dual anti-VEGF and anti-ANG-2 effects of faricimab potentially led to reduced leakage and regression of aneurysms in the intermediate capillary plexus (ICP) and DCP, thus improving retinal vascular stability, reducing ischaemia, and protecting photoreceptor function23, which may have contributed to better visual outcomes in these cases. A study analysing retinal layer thickness changes after conbercept treatment in 20 patients with DME reported the greatest thickness reduction in the INL and outer nuclear layer (ONL), while BCVA improvement was significantly correlated with thickness reduction in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL)24. These findings suggest that the anatomical effects of anti-VEGF agents may vary across retinal layers, warranting further investigation into the differential retinal structural effects of various therapeutic agents.

Diffuse retinal thickening (DRT), considered an early manifestation of DME driven by Müller cell intracellular swelling, has been reported to respond to anti-VEGF therapy9,12,20. Our study corroborated this finding, with DRT being more prevalent at baseline in the treatment-naïve group and showing significant post-treatment resolution. Conversely, the previously treated group exhibited a higher residual DRT rate, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies12.

The baseline prevalence of SRF was higher in the treatment-naïve group. Previous studies have shown that eyes with DME and SRF have higher levels of VEGF, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) in the aqueous humour compared to those without SRF25. A meta-analysis of anti-VEGF agents (ranibizumab, aflibercept, conbercept, and bevacizumab) suggested that SRF-dominant DME may exhibit greater CST reduction but limited visual acuity gains compared to the DRT- or CME-dominant patterns20. In our study, SRF absorption was favourable in both groups, consistent with previous reports evaluating the efficacy of faricimab12,21. Notably, the treatment-naïve group demonstrated particularly pronounced visual acuity improvement, with a higher proportion of eyes achieving a ≥ 2-line gain. The intergroup difference in visual outcomes might be attributable to irreversible outer retinal structural damage associated with persistent SRF, as evidenced by the higher prevalence of EZ disruption in the previously treated group. Some reports have suggested that the association between visual acuity and SRF is stronger than that between visual acuity and DRIL26, highlighting the potential importance of early SRF resolution for good visual prognosis.

Switching to other anti-VEGF agents within the 6-month faricimab treatment period was observed in 9% of the treatment-naïve group and 15% of the previously treated group. Additionally, sub-Tenon’s capsule triamcinolone acetonide injection was administered to 5% of previously treated eyes. A previous study reported a 29% switch rate at 6 months27, indicating a trend towards greater efficacy and reduced economic burden. Concomitant PRP or FPC was administered to 15% of patients in the treatment-naïve group and 11% in the previously treated group during the observation period, underscoring the need for individualised treatment protocols for patients with an insufficient response to anti-VEGF monotherapy.

No serious systemic adverse events were observed in this study and only one case of anterior chamber inflammation was reported, supporting the safety profile of faricimab in clinical practice.

Our study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design may have introduced potential biases related to patient selection and treatment protocols between the treatment-naïve and previously treated groups. Second, the 6-month observation period may have been insufficient to capture the long-term outcomes. While the study was designed to evaluate early treatment responses, extended follow-up is necessary to assess the durability of faricimab, recurrence rates, and post-switch outcomes. Future studies with longer observation periods are warranted. Third, to reflect real-world clinical practice, no exclusion criteria were applied based on prior treatment or need for additional therapy during the follow-up period. Fourth, intraretinal fluid morphology was assessed based on its presence or absence; a quantitative analysis of layer-specific thickness changes might have yielded different results. Fifth, microaneurysms were not quantitatively assessed. Since they are more common in chronic or previously treated eyes and may affect retinal fluid dynamics and treatment response, their omission could limit the interpretation of anatomical outcomes.

Our findings support the efficacy and safety of faricimab for DME and suggest that early resolution of intraretinal fluid in the INL and SRF may serve as a potential biomarker for predicting visual prognosis, emphasising the significance of evaluating local anatomical findings for the development of future treatment strategies. Therefore, further long-term prospective studies are warranted.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in 13 institutions of the Japan Clinical REtinal Study (J-CREST) Group.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokushima University (Approval Code: 4399–1) and the ethics committees of other participating facilities: Kobe University, Fukui University, Tokyo Medical University, Hiroshima University, Kagoshima University, Yamagata University, Mie University, Nagoya City University, Sapporo City General Hospital, Nara Medical university, National Defence Medical College, and Akita University. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the need for informed consent was waived by the all ethics committees mentioned above.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants were patients diagnosed with DME who had received at least one intravitreal injection of faricimab and were followed for at least 6 months. We classified eyes into two groups: the treatment-naïve group (no history of anti-VEGF treatment) and the previously treated group (with prior anti-VEGF treatment) and compared their treatment outcomes. To reflect real-world clinical practice, no exclusion criteria were applied in either group based on prior treatment or need for additional therapy during the follow-up period. All treated eyes that met the minimum faricimab administration and follow-up duration criteria were included in the analysis. Prior or additional treatment interventions, including local steroid administration (sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone acetonide [STTA] injection, intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide [IVTA] injection), intravitreal anti-VEGF injections (ranibizumab, aflibercept, brolucizumab), retinal photocoagulation (PRP, FPC), and surgical interventions (cataract surgery, vitrectomy, glaucoma surgery), were also considered in the analysis.

Data collection

The clinical investigators at each participating institution retrospectively collected the data from the electronic medical records of eligible patients.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were:

-

BCVA: Measured using a Snellen chart and converted to logMAR values at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months post-faricimab initiation.

-

CST: Evaluated as the average retinal thickness within a 1-mm diameter circle centred on the fovea, as determined by OCT at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months post-faricimab initiation.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures included:

-

Baseline characteristics: Age, sex, treated eye (right or left), baseline HbA1c level, and DR stage according to the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy severity scale.

-

Prior treatments: Treatments administered for DME before faricimab initiation, including the type of anti-VEGF agents used and timing of switching to faricimab (if applicable).

-

OCT findings at baseline and 6 months: Assessment of the presence or absence of the following OCT features at baseline and 6 months, determined by the treating physician.

-

Cystoid macular oedema (CME) in the fovea, inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer plexiform layer (OPL)

-

Diffuse retinal thickening (DRT)

-

Subretinal fluid (SRF)

-

Disruption of the Ellipsoid Zone (EZ)

-

Disorganization of the Retinal Inner Layers (DRIL)

-

Epiretinal membrane (ERM)

-

Vitreomacular traction (VMT)

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) images were obtained using commercially available devices at each participating site, including HD-OCT Cirrus 5000 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), SPECTRALIS OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), DRI OCT Triton Plus (Topcon, Tokyo, Japan), and RTVue XR Avanti (Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA, USA). Scanning protocols and parameters followed the standard clinical practice at each institution. For the purpose of this study, foveal CME was defined as the presence of intraretinal fluid within a 1-mm diameter circle centered on the fovea, while other features such as diffuse thickening and subretinal fluid were assessed within a 6-mm diameter circle centered on the fovea.

-

IOP: Measured at baseline and 6 months.

-

Number of faricimab injections: Total number of faricimab injections administered during the 6-month follow-up period.

-

Concomitant and subsequent treatments: Any other treatments relevant to DR management administered during the 6-month follow-up period.

-

Adverse events: Any ocular or systemic adverse events reported during the 6-month follow-up period.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). No imputation was applied for missing values. Continuous variables were evaluated using paired t-tests for within-group comparisons and Welch’s two-sample t-tests for between-group comparisons. Nominal variables were assessed using the McNemar’s test for within-group comparisons and Fisher’s exact test for between-group comparisons. A significance level of 5% was used for all statistical analyses. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni method.

Data availability

The data analysed in this study are not publicly available due to patient privacy regulations and ethical considerations. The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Steinmetz, J. D. et al. GBD 2019 Blindness and vision impairment collaborators; vision loss expert group of the global burden of disease study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health. 9, e144–e160; https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X (2021).

Wang, W. & Lo, A. C. Y. Diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiology and treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1816 (2018).

Nguyen, Q. D. et al. The Tie2 signaling pathway in retinal vascular diseases: a novel therapeutic target in the eye. Int. J. Retina Vitreous. 6, 48 (2020).

Zhu, Q. et al. From monotherapy to combination strategies: redefining treatment approaches for multiple-cause macular edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 19, 887–897 (2025).

Mehta, H. et al. Outcomes of over 40,000 eyes treated for diabetic macula edema in routine clinical practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Ther. 39, 5376–5390 (2022).

Agostini, H. et al. Faricimab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema: from preclinical studies to phase 3 outcomes. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 262, 3437–3451 (2024).

Shimura, M. et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in diabetic macular edema: 2-year results from the Japan subgroup of the phase 3 YOSEMITE trial. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 68, 511–522 (2024).

Nasimi, S., Nasimi, N., Grauslund, J., Vergmann, A. S. & Subhi, Y. Real-world efficacy of intravitreal faricimab for diabetic macular edema: a systematic review. J. Pers. Med. 14, 913 (2024).

Allingham, M. J. et al. A quantitative approach to predict differential effects of anti-VEGF treatment on diffuse and focal leakage in patients with diabetic macular edema: a pilot study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 6, 7 (2017).

Rush, R. B. & Rush, S. W. Faricimab for treatment-resistant diabetic macular oedema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 16, 2797–2801 (2022).

Borchert, G. A. et al. Real-world six-month outcomes in patients switched to faricimab following partial response to anti-VEGF therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular oedema. Eye (Lond.) 38, 3569–3577 (2024).

Quah, N. Q. X., Javed, K. M. A. A., Arbi, L. & Hanumunthadu, D. Real-world outcomes of faricimab treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 1479–1490 (2024).

Pichi, F. et al. Switch to faricimab after initial treatment with aflibercept in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Int. Ophthalmol. 44, 275 (2024).

Durrani, A. F. et al. Conversion to faricimab after prior anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for persistent diabetic macular oedema. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 108, 1257–1262 (2024).

Durrani, A. F. et al. Conversion to faricimab after prior anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for persistent diabetic macular oedema. Clin. Sci. 138, 327–336 (2024).

Tatsumi, T. et al. Treatment effects of switching to faricimab in eyes with diabetic macular edema refractory to aflibercept. Medicina (Kaunas) 60, 732 (2024).

Ohara, H. et al. Faricimab for diabetic macular edema in patients refractory to ranibizumab or aflibercept. Medicina (Kaunas) 59, 1125 (2023).

Shimura, M., Yasuda, K., Yasuda, M. & Nakazawa, T. Visual outcome after intravitreal bevacizumab depends on the optical coherence tomographic patterns of patients with diffuse diabetic macular edema. Retina 33, 740–747 (2013).

Murakami, T. et al. Pathological neurovascular unit mapping onto multimodal imaging in diabetic macular edema. Medicina (Kaunas) 59, 896 (2023).

Yao, J. et al. Comparative efficacy of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor on diabetic macular edema diagnosed with different patterns of optical coherence tomography: a network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 19, e0304283 (2024).

Chakraborty, D. et al. Clinical evaluation of faricimab in real-world diabetic macular edema in India: a multicenter observational study. Clin. Ophthalmol. 19, 269–277 (2025).

Takahashi, H. et al. Evaluating blood flow speed in retinal microaneurysms secondary to diabetic retinopathy using variable interscan time analysis OCTA. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 14, 27 (2025).

Takamura, Y. et al. Turnover of microaneurysms after intravitreal injections of faricimab for diabetic macular edema. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64, 31 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Correlation of retinal layer changes with vision gain in diabetic macular edema during conbercept treatment. BMC Ophthalmol. 19, 123 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Association between aqueous humor cytokines and structural characteristics based on optical coherence tomography in patients with diabetic macular edema. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 3987281 (2023).

Wirth, M. A., Wons, J., Freiberg, F. J., Becker, M. D. & Michels, S. Impact of long-term intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor on preexisting microstructural alterations in diabetic macular edema. Retina 38, 1824–1829 (2018).

Kusuhara, S. et al. Short-Term Outcomes of Intravitreal Faricimab Injection for Diabetic Macular Edema. Medicina (Kaunas) 59, 665 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conception and design: Murao, Yanai, Mitamura. Data collection: Kusumoto, Abe, Shimura, Ohara, Terasaki, Sugimoto, Matsubara, Hirano, Kinoshita, Tsujinaka, Seki, Iwase. Analysis and interpretation: Murao, Yanai, Mitamura. Funding: Mitamura. Overall responsibility: Murao, Yanai, Mitamura

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murao, F., Yanai, R., Kusuhara, S. et al. Visual outcomes and anatomical biomarkers of Faricimab for diabetic macular edema in the J-CREST real-world comparison of naïve and treated eyes. Sci Rep 15, 36628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20300-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20300-6