Abstract

Transformerless inverter topologies with common ground features in solar photovoltaic and grid-connected systems are increasingly preferred due to their ability to effectively suppress leakage current to approximately zero, eliminate transformer-induced losses, and achieve improved energy conversion efficiency. This article presents a high-boost switched capacitor thirteen-level (13L) common ground transformerless inverter topology (HBSC-13L-CGTLI) with a voltage gain of six and reduced cost. Further, the maximum voltage across the switch is 67% of the output voltage, which reduces the cost of the inverter. The proposed topology does not need any separate circuit for its negative voltage level generation. The proposed topology generates a 13L output voltage at the load terminal using a single DC source, thirteen switches, four switched capacitors and three diodes. A detailed description of operational modes, design of the switched capacitor and filter inductor, and loss analysis of the proposed topology is presented. The performance of the proposed topology is validated through MATLAB/Simulink simulations and experimental results from a 1 kW laboratory prototype under various operating conditions. Finally, a detailed, comprehensive comparison of the different 13L inverter topologies is carried out to demonstrate the superior features of the proposed topology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multilevel inverters are gaining more attention in both industry and academic fields due to their wide range of medium and high-power applications, such as speed drives, electric vehicles, high voltage power transmission, renewable energy integration, etc. The increasing penetration of renewable energy sources has highlighted the significance of power electronic converters in grid integration systems. These power electronic interfaces, particularly DC-DC and DC-AC converters, are fundamental in achieving efficient and reliable power conversion for clean energy production. Among various advanced converter topologies, multilevel inverters have emerged as a crucial solution for integrating renewable sources with the electrical grid. Due to the limitations of conventional two-level inverters in operating at high frequencies, multilevel inverters have emerged as a viable alternative1,2. Compared to conventional two-level structures, multilevel inverter configurations offer lower switch voltage ratings, reduced dv/dt stress, higher fundamental component magnitude, improved voltage harmonic profile, minimised electromagnetic interference, and enhanced output power quality. Although multilevel inverters are widely recognised, conventional topologies such as cascaded H-bridge, neutral point clamped (NPC), and flying capacitor (FC) types present several limitations. The key benefit of the series-connected conventional H-bridge configuration is (i) does not need clamping diodes, (ii no series-connected multiple dc-link capacitors, and (iii) absence of flying capacitors. Therefore, the CHB doesn’t need any voltage balancing techniques. However, this topology needs more isolated DC sources to produce higher output voltage levels, while both the NPC structure and the flying capacitor (FC) types suffer from increased component count. Additionally, these structures face challenges with capacitor voltage balancing and sizing issues. Furthermore, these conventional topologies rely heavily on front-end DC-DC circuits to achieve the required grid voltage levels3. To address these limitations, several advanced multilevel transformerless inverter topologies (TLIT) have been reported in the literature, where the integration of switched-capacitor (SC) configurations with a single DC source has emerged as an effective solution for grid-connected solar PV applications. These structures demonstrate enhanced voltage boosting capabilities while maintaining reduced component count, effectively addressing the limitations of conventional multilevel inverters’ topologies4,5.

In the literature6,7,8,9,10,11, several multilevel transformerless inverter topologies have been proposed using switched-capacitor techniques with a single DC source to achieve voltage boosting capability. The reported topologies in literature6,7,8,9,10,11 comprise: a five-level TLIT6, a seven-level TLIT with three-fold voltage gain7, a nine-level TLIT with double boost capability8, an eleven-level hybrid inverter topology for medium voltage applications9, a thirteen-level inverter with three-fold voltage boost and reduced component count10, and a seventeen-level switched-capacitor inverter topology with high voltage gain11. Analysis of these topologies6,7,8,9,10,11 shows several limitations. Topology6 utilises more switches and H-bridges in its structure, resulting in high voltage stress without boosting capability. While topology7 has a lower total standing voltage per unit TSVp.u. voltage, it requires a higher number of switches (12 switches). Topologies8,9 suffer from high switch count with high voltage rating requirements, with topology9 needing additional control circuits for capacitor voltage balancing. Topology10 shows limitations in ripple current control, while topology11 has increased component count, higher TSV, and high inrush current. Furthermore, these topologies have limited applicability when considering solar PV applications, with none addressing the critical issue of leakage current. As leakage current can cause safety hazards, EMI, and component degradation, its mitigation is essential for compliance with standards like VDE-0126-1-1 through modifications in the structure of the inverter topologies and different pulse width modulation (PWM) techniques.

Through modifications in topology design, one of the prominent methods that emerged is the common-ground type topology12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, where the grid neutral and PV source negative terminals are connected to a common ground together, resulting in near-zero leakage current. The topologies12,13,14,15,16,17,18 generate a five-level output voltage, topologies19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 generate a seven-level output, topologies27,28,29,30,31 generate a nine-level output, and topology32 generates a thirteen-level output voltage waveform. All these are common ground topologies designed for solar grid-connected applications, as their common ground structure helps to maximise leakage current suppression. Topology12 employs six switches but exhibits a significantly high maximum blocking voltage of 1.5 times the input voltage and lacks voltage boosting capability. Topology13, while also utilising six switches, maintains a maximum blocking voltage equal to the output voltage but requires additional magnetic components and demonstrates no boosting capability. In14, a five-level common-ground transformerless inverter is proposed using five switches, a diode, and multiple capacitors, but it uses more capacitors despite generating only five output voltage levels without boosting. The topology in15 employs one additional switch compared to14 but requires one capacitor less, with the capacitor voltage stress limited to half of the input voltage. However, it suffers from higher switch voltage stress up to 1.5 times the input voltage and does not offer any voltage boosting capability. The topology in16 uses the same number of power switches as15 and the same number of capacitors as14. It has a maximum switch voltage stress equal to the input voltage and, like14,15, it does not offer any voltage boosting capability. Topology17 introduces 5L CG TLIT with boosting capability; however, it is constrained by a high device-to-level ratio (DLR), and its maximum blocking voltage equals the output voltage. Similarly, topology18, designed as a dual-boost 5L CG TLIT, incorporates six switches but faces limitations with its maximum blocking voltage equalling the output voltage and notably high voltage stress on its components.

Topologies19,20 represent a seven-level CG TLIT with three-fold boost voltage boosting capabilities. Topology19 employs nine switches and achieves a voltage boost of three times the input voltage, with its peak inverse voltage across switches maintained at three times the input voltage (equal to the output voltage). Similarly, topology in20 maintains its peak voltage stress within the output voltage range; however, it requires a higher number of power components compared to topology in19. In21, a seven-level common-ground inverter is proposed with triple voltage boosting and inherent capacitor balancing. While it ensures leakage current suppression, it uses more diodes and requires several switches to block voltages up to 3Vdc, increasing overall cost and complexity. Additionally, it suffers from high capacitor charging currents. In22, a seven-level common-ground inverter with dynamic voltage boosting is proposed. Though it enables single-stage boosting, it uses more power components and imposes maximum switch voltage stress of 2Vdc to generate 7L output levels. Despite its advantages of generating a seven-level output voltage with a three-fold voltage gain23, it suffers from the use of high-rated switches, which leads to a significantly high total standing voltage per unit (TSVp.u.). This increases the voltage stress on the devices, complicates the selection of components, and can affect overall reliability and cost-effectiveness, especially in higher voltage applications. Similar to23, the topology in24 requires several high-rated switches, with some rated up to 3Vdc, leading to a high total standing voltage per unit. Additionally, it uses a magnetic component, an inductor for soft charging, which adds to circuit complexity and introduces extra losses. The topology in25 uses 10 switches, one diode, and two switched capacitors. Five of its switches are rated to block 2Vdc, resulting in a high TSVp.u., which increases voltage stress and impacts cost and reliability. The topology in26 achieves a 7L output with a three-fold voltage boost using a low number of power switches, only six, which significantly reduces switching losses, cost, and control complexity. However, this is achieved at the cost of using more switched capacitors (four in total). In pursuit of higher output voltage levels, topologies27,28,29,30,31 implement nine-level inverter structures with a CG connection and a voltage boosting feature. Both the topologies presented in27,28 are capable of generating nine-level output voltage waveforms; however, their voltage boosting capability is limited to only twice the input voltage, which may restrict their applicability in systems requiring higher step-up gains. Further, the topologies29,30 can boost the output voltage to four times the input voltage, with topology29 utilising nine switches and topology30 employing ten switches. Though the topology in31 offers dynamic voltage boosting, it needs the requirement of magnetic components and a higher number of power switches. Topology32 presents a thirteen-level CG TLIT with a voltage gain limited to three times the input voltage. The aforementioned analysis highlights a critical trade-off in existing topologies: higher switch count yields reduced voltage stress, while fewer components result in increased voltage stress. Addressing this fundamental challenge, this paper presents a thirteen-level inverter topology that optimises both component count and voltage stress, while maintaining enhanced voltage boost capability and leakage current suppression through the CG structure. The key features include,

-

1.

It generates a 13 V output with a six-fold voltage boost, i.e., Vo = 6Vdc.

-

2.

The MBVp.u. of each semiconductor device is within the output voltage, i.e., 0.67Vo

-

3.

Low TSVp.u. and maximum conducting devices.

-

4.

Least cost of the inverter.

-

5.

SC are self-balanced, so no external balancing is needed.

Proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology

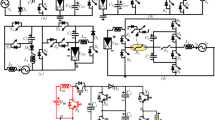

Fig. 1a illustrates the configuration of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology. It consists of thirteen switches (S1–S13), three diodes (D1–D3), and four switched capacitors (SCs) (C1–C4). The proposed structure can generate a 13L output voltage waveform with a boost factor of 6 using four self-balanced SCs. Among these SCs, C1 and C2 are balanced at a voltage equal to the input voltage (Vdc), while C3 and C4 are balanced at 2Vdc. Table 1 presents the distinct switching patterns and the status of SCs used to generate the 13L output voltage. The operation of the proposed inverter topology is explained through 13 modes of operation (States 1–13), as depicted in Figs. 1 and 2. State 1 represents zero voltage levels, states 2 to 7 represent positive output levels, and states 8 to 13 represent negative output levels. Additionally, the proposed inverter topology connects the grid’s neutral and the source’s negative terminal to a common ground, thereby effectively suppressing leakage current to nearly zero, making it highly suitable for grid-connected solar PV applications. A detailed explanation of each of the thirteen distinct output voltage levels is provided below.

State 1: (zero)

The switches S5, S7, and S11 are in a conduction state, and the generated voltage is zero in this state. The switch S1 is also turned ON, which connects the input voltage source Vdc to SC C2 in parallel, thereby charging it to Vdc. The corresponding charging path of the SC C2 is via x-S1-D1-n as depicted in Fig. 1b.

State 2: (+ Vdc)

In this state, the switches S3, S4, and S11 are switched ON, applying the source voltage across the load terminals to generate a voltage level + Vdc. With switches S2 and S3 ON, and S1 OFF, SC C1 is charged to Vdc via the path x − S3 − S2 − n. Additionally, the SCs C3 and C4 are charged to a voltage of + 2Vdc (VC1 + VC2), as switches S5, S8, and S10 are ON, as shown in Fig. 1c.

State 3: (+ 2Vdc)

To generate the + 2Vdc voltage level, switches S1, S4, and S11 are turned ON, and their corresponding load current path is illustrated in Fig. 1d. The input source voltage Vdc and the stored voltage of SC C1 are added together to supply the load. Simultaneously, as S1 is ON, SC C2 charges through the path x − S1 − D1 − n. As same as, + Vdc output voltage level, the SCs C3 and C4 are also charged to a voltage of + 2Vdc (VC1 + VC2/dc).

State 4: (+ 3Vdc)

To achieve the + 3Vdc output voltage level, the input source Vdc and the voltage across the SC C3 are summed up, and the respective current flow path is x-S3-S4-S6-S8-S11-n as depicted in Fig. 1e. Meanwhile, with switches S2 and S10 turned ON, SCs C1 and C4 are charged to a voltage of Vdc and 2Vdc, respectively.

State 5: (+ 4Vdc)

With switches S1, S4, S6, S8, and S11 switched ON, an output voltage of + 4Vdc output voltage level is achieved. The input source Vdc, along with the voltages of SCs C1 and C3, is summed up as illustrated in Fig. 1f. Meanwhile, with switch S1 turned ON, SC C2 is charged to Vdc via x-S1-D1-n.

State 6: (+ 5Vdc)

The positive terminal of the source and the terminal denoted as ‘y’ are connected to generate a + 5Vdc output voltage level by turning ON the switches S3, S4, S6, S9 and S11, as depicted in Fig. 1g. This enables the source voltage This enables the source voltage Vdc, to combine with the SC voltages VC3 and VC4 to generate an output voltage equal to + 5Vdc. Additionally, with S2 turned ON, the SC C1 is charged via the path x − S2 − S3 − n.

State 7: (+ 6Vdc)

As far as the last positive level of the proposed inverter is concerned, the switches S1, S4, S6, S9, and S11 are turned ON, enabling the source voltage Vdc to add up with voltage across capacitors C1, C3 and C4, thereby generating a + 6Vdc output voltage, as illustrated in Fig. 1h. Meanwhile, with switch S1 turned ON, SC C2 is charged to Vdc via x-S1-D1-n.

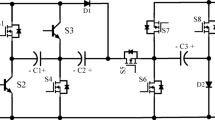

State 8: (− Vdc)

During this mode, the voltage across SC C2 is utilised to generate − Vdc, by turning ON switches S5 and S12, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Additionally, switch S3 is also turned ON, which connects the source in parallel with C1, allowing it to charge to Vdc. The load current flow path is S2-S5-S7-S10-S12-y-n as depicted in Fig. 2a.

State 9: (− 2Vdc)

To synthesise the − 2Vdc voltage level, the switches S5, S7, S8, and S12are triggered ON, establishing a current path through D-S5-S7-S8-S12-y-n, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Meanwhile, with switch S1 turned ON, SC C2 is charged to Vdc via x-S1-D1-n.

State 10: (− 3Vdc)

In this operating state, switches S5, S7, S10, and S12 are triggered ON, allowing the voltages of SCs C2 and C4 to be utilised to generate − 3Vdc. Similar to State 8, switch S3 is also turned ON, connecting the source in parallel with C1 and enabling it to charge to Vdc through x − S2 − S3 − n. The load current flow path is S2-S5-S7-S10-S12-y-n, as depicted in Fig. 2c.

State 11: (− 4Vdc)

The stored energy of the SCs C3 and C4 is utilised in this state to generate a − 4Vdc output voltage. This can be achieved by turning ON the switches S5, S7, S9, and S12 as shown in Fig. 2d. As same as state 9, SC C2 is charged to Vdc via x-S1-D1-n.

State 12: (− 5Vdc)

The second last negative output voltage level, i.e., − 5Vdc, is obtained by utilising the stored energy of SCs C2, C3 and C4, corresponding to VC2, VC3, and VC4, respectively. This is achieved by the on-state switches S2, S5, S7, S9 and S12 as depicted in Fig. 2e. Here to the SC C1 is charged to Vdc via x − S2 − S3 − n.

State 13: (− 6Vdc)

As far as the last negative level of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology is concerned, the switches S5, S7, S9, S12 and S13 are turned ON to add the voltages of all SCs C1-C4 as shown in Fig. 2f.

Considering all operational states (1–13) and the respective switching sequences depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, it is observed that the peak inverse voltage (PIV) of each switch remains within the maximum output voltage of 6Vdc, i.e., 0.67Vdc, as listed in Table 2. Considering the PIV of all switches, the quantitative measure of the cumulative voltage stress across all switching devices TSVp.u. of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology is computed as,

where PIVi denotes the peak inverse voltage of the ith switch, and n represents the total number of switches in the circuit.

Design of passive components (SCs (C1-C4) AND FILTER INDUCTOR (Lf))

Design of SCs (C1-C4)

The higher multilevel output voltages have been generated in switched capacitor multilevel inverters based on the charging and discharging of capacitors employed in their circuit structure. So, capacitance selection is an essential parameter in a switched-capacitor multilevel inverter to achieve higher output voltage levels. The capacitances of all four SCs (C1-C4) are selected according to their maximum discharging period (MDP). The total stored charge (QC) of the SC is expressed as29,

where the QC represents the total charge stored on the SC, t1 is the start time of the MDP and t2 is its end time of the MDP, and Im is the maximum grid current.

The 13L output voltage waveform of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology with its SCs MDP and voltage across SCs (C1-C4) are shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 3 shows that the SCs C1 and C2 demonstrate MDP of t5 to (π-t5) and t4 to (π-t4), respectively. Furthermore, SCs C3 and C4 operate with symmetrical MDPs of t2 to (π-t2), with SC C3's MDP occurring in the positive half-cycle and SC C4 in the negative half-cycle of the output voltage waveform.

The charge of SC C1 during its MDP, i.e., t5 to (π-t5) is written as,

The charge of SC C2 during its MDP, i.e., t4 to (π-t4) is written as,

Similarly, the charge of SCs C3 and C4 during its MDP, i.e., t2 to (π-t2) is written as,

Considering a permissible voltage ripple of 15% and MDP of the SCs, the expression for the capacitor is written as,

The maximum value of the capacitances of the SCs C1-C4 can be expressed as Eqs. (4)-(6):

Design of Filter Inductor L f

The current through the filter inductor (iLf(t)) over one complete cycle, considering the voltage across the inductor VLF, and the initial inductor current iLf (0), is represented as,

Considering the maximum output voltage level of the inverter, which corresponds to the zone-f as depicted in Fig. 3, the inductor ripple current is obtained as18,

The duty cycle df can be obtained by applying the inductor volt-sec balance principle at zone-f, and it is obtained as,

From (10) and (13), the value of the inductor filter (Lf) is calculated as,

Loss analysis

In this section, the theoretical total power loss of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology is discussed to estimate its efficiency. The efficiency (η) of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology, which is a measure of how effectively it converts DC power into AC power while minimising losses, is defined as follows,

The total power loss of a multilevel inverter is the sum of conduction and switching losses of switches and diodes, and ripple loss of capacitors.

where Pcon and Psw represent the conduction and switching losses of the switches and diodes, Pr denotes the ripple loss of the capacitor.

Conduction losses

In a multilevel inverter, conduction losses originate from the on-state resistance of semiconductor switches and the equivalent series resistance of capacitors. These losses happen when the switches remain in the on state while conducting current. By applying Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) to the equivalent circuits shown in Fig. 4 and considering parasitic elements such as the on-state switch resistance (RnS), diode resistance (RnD), capacitor’s internal resistance (RrC), and the diode’s forward bias voltage drop (Vd), the power loss at different output voltage levels is determined and estimated43 using Eqs. (17)-(31).

Considering both switching devices and capacitors, the total conduction loss is mathematically represented as,

where IS and ID represent the RMS value of current flowing through the active switching devices and diodes during the conduction period, while IC denotes the RMS value of current passing through the capacitors. These current components and their respective internal resistances contribute to the overall conduction losses in the proposed topology. Considering the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 4b for zero-level output voltage generation, four switches, one diode, one DC input source, and a switched capacitor are involved in the conduction path. The corresponding conduction losses can be mathematically expressed as,

From the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 4c, the next highest voltage level (+ Vdc) involves six switches, two diodes, and four capacitors in the conduction path. The corresponding conduction losses are given by,

The conduction loss equations for the remaining positive voltage levels (+ 2Vdc to + 6Vdc) are represented as follows,

Following the same approach as positive levels, the conduction losses for all negative voltage levels (-Vdc through -6Vdc) are calculated as follows,

The total conduction losses of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology can be calculated by summing up all the individual voltage level losses calculated from Eqns. (18–30) as follows,

Switching losses

Switching losses in semiconductor devices occur due to the finite transition time during turn-on and turn-off processes, where the simultaneous presence of voltage and current leads to power dissipation. These losses are assessed over a fundamental cycle, considering the switching times (ton and toff), with turn-off typically contributing more to overall losses. To simplify the analysis, switching losses are often evaluated using a linear approximation of voltage and current variations during the transition periods42. Considering energy dissipation during the turn-on and turn-off periods,

The currents Ion,i and Ioff,i represent the current flowing through the ith switch during turn-on and before turn-off, respectively, while Vs, i denotes the voltage of the switch in the OFF state.

Considering the number of ON and OFF transitions of the ith switch over one complete cycle, the switching loss for the ith switch can be calculated as,

Using (34) and considering the switching frequency fsw, the overall switching losses of the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology can be expressed as,

Capacitor ripple losses

Considering all four SCs, C1-C4, the capacitor voltage ripple loss is expressed as43,

Comparative assessment

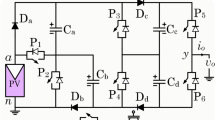

A comprehensive comparative assessment has been performed between the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI topology and other 13L inverter output voltage topologies. The topologies are classified into four distinct categories: multi-source 13L inverter topologies33,34,35, single DC source with three-fold boost topologies10,36,37,38,39, single DC source with six times boost topologies40,41,42,43, and single DC source with three boost and six boost configurations having common ground features32,44,45,46 as depicted in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8. The comparison encompasses critical parameters including component count (switches (Nsw), drivers (Ndr), diodes (Nd), capacitors (Nc), total component count (TD)), voltage metrics (TSVp.u., and MBVp.u.), ratios (switch-to-level generation (Nsw/NL), and switch-to-gain number (Nsw/Gain)), capacitor voltage diversity factor (CDF), and number of peak voltage stress switches (PVS). Through this comprehensive comparison study, the advantages and various trade-offs of the proposed topology against existing configurations are thoroughly examined and presented in this section. Comparing various 13L topologies, in the first category, the one proposed in34 uses a minimum of 11 switches, while the remaining two topologies33,35 use 14 switches. In the second category of three-fold boost 13L inverter topologies,36,39 generate 13L output using 11 switches, while the topology in37 uses 14 switches. In the third category with six-boost topologies,32,41 require a minimum of 13 switches, while topology43 uses a maximum of 15 switches to generate a 13L output voltage waveform. In the final category of common ground feature topologies,32 utilises a minimum of 11 switches, followed by the proposed topology, which employs 13 switches to generate a 13L inverter output voltage. The other topologies44,45,46 in this category use a significantly greater number of switches. Among the common ground featured multilevel inverter topologies in the fourth category, as shown in Fig. 8, when comparing topology32 and the proposed topology with other topologies presented in33,34,35, these topologies utilise a significantly higher number of power switches to generate a 13L output voltage. Although topology32 employs two switches and one diode fewer than the proposed topology, its voltage boosting capability is only half compared to the proposed topology. Specifically, while the proposed topology achieves six times the input voltage boost, topology32 achieves only three times the input voltage boost.

Comparing all topologies shown in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8, the lowest switch count of 11 is used by topologies proposed in32,34,36,38, and39. Although these topologies use slightly fewer switches than the proposed topology, their voltage-boosting capability is significantly lower than the proposed topology. Additionally, the topology proposed in34 requires two separate voltage sources to achieve 13L with a boost factor of 2. Furthermore, the proposed topology is extensively compared with existing topologies based on voltage metrics (TSVp.u. and MBVp.u.) and performance ratios (switch-to-level generation and switch-to-gain number). While comparing all the topologies with the proposed topology based on voltage metrics, the TSVp.u. of the proposed topology is 5.5, ranking as the third least, while its MBVp.u. is 0.67, positioning as the fourth least compared to all other topologies. Although the proposed topology has a TSVp.u. of 5.5, topologies36,43, and46 demonstrate lower TSVp.u. value of 5. Though the topology36 has the lowest TSVp.u. of 5 with an MBVp.u. of 0.67, its gain is limited to only 3. Similarly, topology43 also achieves a minimum TSVp.u. of 5; however, it requires 15 power switches in total for its 13L output voltage waveform generation, which is higher than the proposed topology’s requirement of 13 switches. The one in46, despite having the least TSVp.u. of 5, demands approximately 30 power switches, which is significantly higher than the proposed topology. Even with its favourable MBVp.u. of 0.15, its generalised topology type requires an excessive number of switches. The second-least TSVp.u. of 5.33 is shared by topologies10,32, and41. When comparing topology10 with the proposed topology, both utilise 13 power switches, but topology 5 achieves only half the voltage gain (3 compared to the proposed topology’s gain of 6), despite having a slightly lower TSVp.u. Its MBVp.u. is 0.67, which is comparable to the proposed topology. Similarly, topology41 also employs 13 switches and demonstrates comparable operational characteristics, though with a slightly lower MBVp.u. of 0.5 compared to the proposed topology’s 0.67. The topology proposed in32, while maintaining the same switch count of 13, exhibits a TSVp.u. of 5.3 and a higher MBVp.u. of 1.0. However, like topology10, it only achieves a voltage gain of 3, which is half of what the proposed topology delivers (gain of 6). The proposed topology and topology in37 both exhibit a TSVp.u. of 5.5, which ranks as the third-lowest among all topologies in the comparison. While sharing identical TSVp.u., topology37 exhibits a higher MBVp.u. of 1 and requires 14 power switches in contrast to the proposed topology’s 13 switches. Regarding total power device requirements, topology37 utilises 30 devices compared to the proposed topology’s 33.

Significantly, the proposed topology challenges conventional design principles where a higher switch count typically correlates with lower stress levels. Instead, it successfully demonstrates optimal stress management despite utilising a higher component count, representing an innovative approach to topology design. Unlike conventional multilevel inverter designs, where reduced switch count typically leads to increased voltage stress profiles, the proposed topology demonstrates a unique capability to maintain lower voltage stress profiles across switches despite utilising a reduced number of power components, thus challenging the traditional trade-off between component count and voltage stress distribution. When comparing Nsw/NL, Nsw/Gain across topologies, the proposed topology achieves an Nsw/NL of 1 and an Nsw/Gain of 2.17, performance levels that are only matched by topologies41,42 in the existing literature. The proposed topology outperforms most existing configurations with an impressive Nsw/Gain of 2.17, followed closely by topologies40,43, while all other existing topologies lag significantly behind in this crucial performance metric. The CDF emerges as another crucial comparison metric, owing to its direct impact on inverter cost and size optimisation. This key parameter fundamentally influences the achievement of higher power density at reduced costs. The diversity factor, calculated as the ratio of total capacitor voltages to peak output voltage32, positions the proposed topology at 1, which is in par with the high-boost topologies. The number of peak voltage switches, defined as switches experiencing maximum output voltage, represents another significant evaluation criterion. Analysis shows that the proposed topology, along with topologies10,36,40,41,42,43,44, and46, demonstrates superior characteristics as none of their switches require a voltage rating equal to the output voltage.

Notably, in the proposed configuration, the maximum switch voltage stress is limited to 0.67% of the output voltage. Furthermore, a detailed cost function (CF) analysis is conducted using weighted factors under two categories: α = β = 0.5 and α = β = 1.5 and discussed. The CF has been computed32 and expressed as

Based on cost function analysis, Eq. 37, topologies40,41,42,43 and the proposed topology demonstrate optimal cost metrics. Although the proposed topology exhibits marginally higher cost indices compared to topologies40,41,42,43, it uniquely incorporates common ground characteristics. This facilitates maximum leakage current suppression (~ 0 mA), a critical feature absent in topologies40,41,42,43, making it particularly advantageous for grid-connected PV applications. The proposed topology demonstrates superior performance compared to existing common-ground configurations32,44,45,46, with significantly lower cost function values of 6.21 and 7.29 (with weight factors considered). With the considered weight factors α and β, the proposed topology achieves cost function values of 6.21 and 7.29. When compared with other common-ground type topologies32,44,45,46, the proposed topology demonstrates significantly lower values. This reduction in cost function values indicates the superior performance of the proposed topology over the other CG topologies.

A comprehensive cost comparison analysis was performed for the topologies with a gain of 641,42,43,44,45,46, with the results documented in Table 3. All topologies were evaluated under identical operating conditions: an input voltage of 60 V, an output voltage of 360 V, and a rated output power of 1 kW. The component selection for each topology was carefully optimised based on these design specifications. The detailed cost analysis, including component-wise breakdown and total system costs, is systematically presented in Table 3 for comparative evaluation. From Table 3, the cost analysis shows that the proposed topology achieves the lowest inverter cost both with and without heatsink considerations. The next lowest cost is observed in topology42, followed by topologies41,43, respectively. Performance evaluation metrics, including Fractional Gain Constant (FGC) and Improved Subtractive Gain Cost (ISGC), were determined47 for all topologies under consideration and listed in Table 3. The analysis demonstrates that the proposed topology exhibits superior characteristics with notably higher values of FGC and ISGC parameters. These enhanced metrics conclusively establish the proposed topology’s operational advantages over other configurations.

Fig. 9 shows the graphical representation that illustrates a comprehensive comparison analysis through a radar chart, evaluating various topologies32,41,42,43,44,45,46 and the proposed topology. The comparative analysis encompasses critical parameters, including Nsw, Nsw/NL, Nsw/Gain, cost of the inverter, and maximum conducting switches (MCS) across all configurations. The comparative analysis through radar chart visualisation demonstrates that the proposed topology exhibits the lowest area coverage compared to other topologies32,41,42,43,44,45,46. This minimal area coverage in the radar chart significantly indicates that the proposed topology emerges as one of the prominent candidates among the different configurations32,41,42,43,44,45,46. The proposed topology demonstrates remarkable characteristics through comprehensive comparative analysis: reduced component count, high voltage boost capability, low CDF, one of the lowest TSVp.u. and MBVp.u., and notably the lowest cost inverter among the compared topologies, while achieving the highest FGC and IGSC indices. These distinctive advantages establish it as an optimal candidate for grid-connected solar PV applications.

Results and discussion

The proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI inverter topology is analysed through simulation using the MATLAB/Simulink platform and experimentally validated using a 1 kW laboratory prototype. The analysis is carried out under steady-state, transient, and grid-connected conditions, and the corresponding results are presented and discussed in this section.

Simulation results

Initially, with an input voltage of 60 V, the proposed inverter topology achieves an output voltage of 360 V with 13 levels as depicted in Fig. 10a. Under present steady-state testing conditions with a resistive load of R = 120 Ω, the corresponding output current reaches a peak value of 3 A with an RMS value of 2.121 A, as illustrated in Fig. 10b. The voltage across the SCs C1-C4 is illustrated in Fig. 10c–f, where it can be seen that C1 and C2 maintain a balanced voltage at the input voltage level of 60 V, while C3 and C4 are balanced at twice the input voltage, specifically at 120 V. The performance of the proposed topology is further evaluated with an RL load Z = 60 + j100 Ω. The results show that the load voltage maintains six-times boost characteristics, achieving 360 V at the output. Under these loading conditions, the load current reaches a peak value of 5.3 A with a corresponding RMS value of 3.76 A, as shown in Fig. 10g,h. Figs. 10 (i–l) depicts that the capacitor voltages C1 and C2 are maintained at 60 V, while C3 and C4 are maintained at 120 V during RL load operation, with minimal ripple variations as shown in the waveforms.

Simulation results of (a) Output voltage (vo) at R = 120 Ω, (b) Load current(io) at R = 120 Ω, (c–f) SCs voltage VC1, VC2, VC3, VC4 at R = 120 Ω, (g) Output voltage (vo) at Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (h) Load current (io) at Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (i–l) SCs voltage VC1, VC2, VC3, VC4 at Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (m–o) Output voltage (vo), Load current (io) & SCs voltage VC1, VC3 at Z = 60 + j100 Ω during step change in input voltage, (p,q) Output voltage (vo), & Load current (io) during change in load from R = 100 Ω to at Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (r,s) Output voltage (vo), & Load current (io) during modulation index change 1.0 to 0.8 at Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (t,u) Output voltage (vo), & Load current (io) during modulation index change 0.8 to 0.5 at Z = 60 + j100 Ω.

To evaluate the dynamic transient operating capability of the proposed topology, different tests are performed, such as varying input voltage conditions, load variations and modulation index (MI) variations. The analysis primarily focused on examining the system’s response to input voltage variations from 54 to 60 V while the load was maintained at Z = 60 + j100 Ω. The resultant waveforms, illustrated in Fig. 10m–o, demonstrate the behaviour during the voltage transition. Fig. 10m demonstrates that when the input voltage is maintained at 54 V, the output voltage stabilises at ~ 325 V, and upon increasing the input to 60 V, the output voltage rises to 360 V. The corresponding current waveforms exhibit peak values of 4.7 A and 5.3 A, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 10n. Fig. 10(o) presents the capacitor voltage waveforms during the input voltage transition from 54 to 60 V. The results indicate that the capacitor voltages effectively track the changing input voltage while maintaining balanced voltage levels across the operating range. In general, the load conditions are not constant in practical applications. Therefore, the performance of the proposed topology under varying load conditions is tested with two load configurations: a pure resistive load R = 100Ω and an RL load Z = 60 + j100 Ω. The corresponding output voltage and current waveforms are presented in Figs. 10p,q, respectively.

The results demonstrate that the load voltage remains consistently regulated at 360 V throughout the transition, and the current waveform analysis shows that under R load, the current maintains a steady value of 3.6 A. When switched to RL load, the waveform becomes sinusoidal with a peak value of 5.3 A, as depicted in Fig. 10q. The performance of the proposed topology is checked by examining its behaviour across varying modulation indices (MI). The investigation involved systematic transitions of MI from 1 to 0.8, and subsequently from 0.8 to 0.5, while maintaining the RL load of Z = 60 + j100 Ω. The results demonstrated distinct operational characteristics at each modulation index: at MI = 1, the system successfully achieved all 13 levels with corresponding voltage and current values of 360 V and 5.3 A; at MI = 0.8, the level count decreased to 11, yielding voltage and current measurements of 303 V and 4.3 A respectively; and at MI = 0.5, the system operated at 7 levels, producing a voltage output of 185 V with peak current reaching 2.4 A as shown in Figs. 10r–u.

In addition to steady-state and transient response analysis, the grid-connected operation of the proposed topology is evaluated, and the respective results are presented in Figs. 11 and 12, which demonstrate the topology’s performance under various operating conditions. The proposed topology is tested under unity power factor, lagging power factor, and leading power factor conditions, and the corresponding results are depicted in Figs. 11a–c. Furthermore, the topology’s response to reference current variations is examined through step changes from 1.5 A to 5 A, and the results are presented in Fig. 12b. These comprehensive simulation results validate that the proposed topology maintains optimal performance across all operating conditions.

Power losses occurring in the semiconductor switches and diodes of the proposed 13L inverter were analysed using Piecewise Linear Electrical Circuit Simulation version 4.3.6 (PLEXIM) simulation software48 with IKW50N60DTP devices operating at 25 °C at different output power levels. Fig. 13 illustrates the power loss distribution across the semiconductor devices of the proposed 13L inverter topology. The analysis shows that switches S1-S5 experience predominant losses due to their position in the capacitor charging path, with diodes D1-D3 exhibiting the next significant contribution to power losses. Fig. 14a, b illustrate the power loss analysis of the proposed 13L inverter topology at unity power factor for output powers of 500 W and 1000 W, respectively. The analysis shows total power losses of 14 W at 500 W output and 52 W at 1000 W output. It can be observed from Fig. 14c that the efficiency of the proposed inverter topology decreases as the output power increases, with the highest efficiency achieved at lower power levels.

Experimental results

The proposed 13L inverter topology was experimentally validated using a laboratory prototype, as shown in Fig. 15. The prototype was designed for a 1 kW output power rating and incorporated SKM75GB063D switching devices, MUR5060 diodes, and HCPL-3120 gate drivers, all interfaced with a Texas Instruments TMS320F28379D digital controller. A soft charging inductor of 33 μH was utilised during the experimental validation to reduce the inrush current. Table 4 lists the specifications of the experimental prototype.

The experimental results illustrated in Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19 demonstrate the performance of the proposed inverter topology. Tests were performed under two loading conditions: a pure resistive load of R = 100 Ω and an inductive load of Z = 60 + j100 Ω at a modulation index (Ma) of 1.0. The experimental measurements at 60 V input demonstrate that the inverter output maintains 360 V while exhibiting peak load currents of 3.6 A and 5.34 A for resistive and inductive loading conditions, respectively. These results, presented in Figs. 16a,b, substantiate the designed voltage gain factor of six in the proposed topology. Further analysis of the voltage and current profiles for the SCs (C1, C2, C3, C4) is presented in Figs. 16c,d. As shown in Figs. 16c,d, the measured results indicate that capacitors C1 and C2 maintain voltage levels at 60 V, while C3 and C4 operate at 120 V, with an allowable voltage ripple of 10%, and their charging current profiles remain within the specified limits under inductive loading conditions of Z = 60 + j100 Ω. The dynamic performance of the proposed inverter topology has been analysed under variations in input voltage (from 54 to 60 V), load (from R = 100 Ω to Z = 60 + j100 Ω), and MI variation (from MI = 1 to MI = 0.8), with the corresponding results presented in Figs. 17a–d. While changing the input voltage from 54 to 60 V, initial measurements at 54 V input demonstrated a 13L output voltage waveform with a magnitude of 324 V, corresponding to a peak load current of 4.7 A. Upon increasing the input voltage to 60 V, the system maintained its 13L output configuration while achieving an output voltage of 360 V, with the peak current magnitude escalating to 5.3 A. The experimental results illustrated in Fig. 17b validate that the SC voltages VC1-VC4 maintain voltage-balanced operation throughout the input voltage transition period. Next, a load change operation has been performed, transitioning from a pure resistive load of R = 100 Ω to an inductive load of Z = 60 + j100 Ω and the respective waveforms are depicted in Fig. 17c. It can be observed that with a resistive load, the output voltage waveform and output current waveform are in phase, with a current magnitude of 3.6 A. When the load changes to inductive, it follows a sinusoidal pattern, with the peak current value reaching 5.3 A at a power factor of 0.89. Furthermore, the dynamic operating behaviour of the proposed topology was analysed by varying the modulation index (MI) from 1.0 to 0.8 under an inductive load of Z = 60 + j100 Ω, and the corresponding results are presented in Fig. 17d. The analysis shows that when the modulation index is 1.0, the proposed topology fully achieves 13L output voltage levels with a peak voltage of 360 V and a peak load current of 5.3 A. Upon reducing the modulation index from 1.0 to 0.8, the output voltage levels decrease to 11 L, with the output voltage and peak current dropping to 301 V and 4.3 A, respectively. Additionally, the voltages across the switched capacitors C1 and C2 during this dynamic operation are illustrated in Fig. 17d.

Experimental results during dynamic operating conditions (a) Output voltage vo and current io and SC voltage VC1 for a step change in input voltage from 57 to 60 V, (b) Voltage profile of SCs (C1-C4) at load Z = 60 + j100 Ω for a step change in input voltage from 57 to 60 V, (c) Output voltage vo and current io for a load change of R = 100 Ω to Z = 60 + j100 Ω, (d) Output voltage vo and current io and SC voltage VC1 and VC2 for a change in MI from 1 to 0.8.

As depicted in the Fig. 18, the control architecture for grid-connected operation is implemented as described in16. The filtered current ig is injected into the utility system, where the grid synchronization block manages synchronisation with the utility voltage. This synchronisation enables the transformation block to convert the desired active (P) and reactive (Q) power references into corresponding current components (igref||) and (igref⊥), which are then combined to form the total reference grid current (igref). The actual grid current (ig)is compared with this reference, and a Proportional-Resonant (PR) controller processes the resulting error to generate the voltage reference Vref. This reference is used by the PWM block to generate appropriate gate signals, which are fed to the gate driver to control the inverter power switches.

The Proportional–Resonant (PR) controller effectively regulates sinusoidal currents by combining two adjustable parameters: the proportional gain (Kp) and the resonant gain (Kr). It is used as the inner current controller to ensure accurate tracking of the reference current (ig,ref), typically set for a unity power factor. The PR output feeds into the PWM stage, controlling the inverter’s switching. The PR controllers operate in the stationary reference frame and offer infinite gain at the grid frequency ωo, eliminating steady-state error.

The standard transfer function is:

To ensure digital implementation stability, a damping factor is added:

In the proposed HBSC-13L-CGTLI system, the values Kp = 62.83 and Kr = 6283 are chosen via iterative tuning for optimal performance in a 1 kW setup.

The inverter’s output voltage (vo) waveform, grid voltage (vg) waveform, and grid current (ig) waveform under various power factor (PF) conditions such as unity PF, leading PF, and lagging PF conditions of the proposed topology is tested and the respective results are presented in Fig. 19a–c. Fig. 20a–d illustrates the voltage stress profile of the switches (S1-S13) and diodes (D1-D3). These blocking voltage measurements reveal that switches S1, S3, S4, S5, S8, S9, S10, and S13 experience blocking voltage equal to twice the input voltage (2Vdc), switch S2 blocking voltage equals the input voltage (Vdc), while switches S6, S7, S11, and S12, along with diodes D2 and D3, maintain a maximum blocking voltage of 67% of the output voltage.

Fig. 21a presents the experimental efficiency comparison between the proposed topology and those presented in41,43. For identical output power conditions, the experimental efficiency of the proposed topology demonstrates superior performance compared to41,43. Additionally, Fig. 21b illustrates the correlation between simulation and experimental analysis of the proposed topology.

Conclusion

A single-source, high-boost, switched-capacitor-based 13L CG transformerless inverter topology with a voltage gain of six is proposed. The proposed structure utilises fewer devices compared to other recent topologies with the same output voltage level, achieving sixfold voltage boosting without the use of an H-bridge. The voltage of the switched capacitors is maintained using a series–parallel configuration, thereby validating their self-balancing capability. An important feature of the proposed topology is its use of a reduced number of switches while achieving a high voltage boost. Moreover, the MBVp.u. of the switches remains within the output voltage, i.e., limited to 67% of the output voltage. A detailed comparison with existing topologies of the same 13L output voltage level shows that the proposed configuration achieves higher voltage gain with reduced power switch count and lower maximum blocking voltage (MBV), resulting in significantly lower overall cost. The experimental prototype of 1 kW was tested across a range of operating conditions, including steady-state, dynamic response, and grid-connected scenarios, demonstrating the effectiveness and practical viability of the proposed topology. The simulation efficiency of the proposed topology is 98.6%, while the measured efficiency is 97.5%, both of which are higher than those of recent topologies at the same output power levels. The proposed topology stands out for its high voltage boost with reduced switches, low MBVp.u., and cost-efficiency. Combined with the CG feature, it is well-suited for solar PV applications that demand high voltage gain and zero leakage current.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rodríguez, J., Lai, J. S. & Peng, F. Z. Multilevel inverters: A survey of topologies, controls, and applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 49, 724–738 (2002).

Romero-Cadaval, E. et al. Grid-connected photovoltaic generation plants: Components and operation. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 7, 6–20 (2013).

Kouro, S. et al. Recent advances and industrial applications of multilevel converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 57, 2553–2580 (2010).

Hinago, Y. & Koizumi, H. A switched-capacitor inverter using series/parallel conversion with an inductive load. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 59, 878–887 (2012).

Taghvaie, A., Adabi, J. & Rezanejad, M. A self-balanced step-up multilevel inverter based on switched-capacitor structure. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33, 199–209 (2018).

Bharath, G. V., Hota, A. & Agarwal, V. A new family of 1-φ five-level transformerless inverters for solar PV applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56, 561–569 (2020).

Siddique, M. D., Mekhilef, S., Shah, N. M., Ali, J. S. M. & Blaabjerg, F. A new switched capacitor 7L inverter with three-fold voltage gain and low voltage stress. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II(67), 1294–1298 (2020).

Siddique, M. D., Aslam Husain, M., Iqbal, A., Mekhilef, S. & Riyaz, A. Single-phase 9L switched-capacitor boost multilevel inverter (9l-sc-bmli) topology. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59, 994–1001 (2023).

Panda, N. et al. A new grid interactive 11-level hybrid inverter topology for medium-voltage application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 57, 869–881 (2021).

Bhatnagar, P., Singh, A. K., Gupta, K. K. & Siwakoti, Y. P. A switched-capacitors-based 13-level inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37, 644–658 (2022).

Anand, V. et al. Seventeen level switched capacitor inverters with the capability of high voltage gain and low inrush current. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 4, 1138–1150 (2023).

Pandurengan, G. N., Krishnasamy, V., Ali, J. S. M. & Almakhles, D. Five-level transformerless common ground type inverter with reduced device count. Inf. MIDEM 52, 71–82 (2022).

Neti, S. S., Singh, V. & Anand, V. Common ground buck type five-level transformerless inverter with less stress. IEEE Trans. ircuits Syst. II Express Briefs 71, 2419–2423 (2024).

Singh Neti, S. & Singh, V. A common ground switched capacitor-based single-phase five-level transformerless inverter for photovoltaic application. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 51(6), 2854–2874 (2023).

Pandurangan, G. N., Krishnasamy, V., Ali, J. S. M., Mahmood, F. M. & Almakhles, D. Single-phase common ground type 5L inverter with reduced capacitor voltage stress for photovoltaic applications. IET Power Electronics 16(5), 883–892 (2023).

Guo, B. et al. A single-phase common-ground five-level transformerless inverter with low component count for PV applications. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70(3), 2662–2674 (2022).

Anand, V., Singh, V. & Mohamed Ali, J. S. Dual boost five-level switched-capacitor inverter with common ground. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 70, 556–560 (2023).

Kumari, S., Sandeep, N., Verma, A., Yaragatti, U. R. & Pota, H. Design and implementation of transformer-less common-ground inverter with reduced components. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 9994, 1–10 (2022).

Jakhar, A., Sandeep, N. & Verma, A. K. Seven-level common-ground-type inverter with reduced voltage stress. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 12, 2108–2115 (2024).

Jakhar, A., Sandeep, N. & Member, S. Switched-capacitor-based seven-level boosting inverter with reduced voltage stress for grid-connected photovoltaic applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2025, 1–10 (2025).

Grigoletto, F. B., de Vilhena Moura, P. H., Chaves, D. B., & Vilaverde, J. D. S. Step-up seven-level common-ground transformerless inverter. In 2021, 14th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON) 716–722 (IEEE, 2021).

Barzegarkhoo, R., Farhangi, M., Lee, S. S., Aguilera, R. P., & Siwakoti, Y. P. A novel seven-level switched-boost common-ground inverter with single-stage dynamic voltage boosting gain. In 2022 International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Himeji 2022-ECCE Asia) 873–877 (IEEE, 2022).

Srivastava, A. & Seshadrinath, J. A single-phase seven-level triple boost inverter for grid-connected transformerless PV applications. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 70(9), 9004–9015 (2022).

Kumari, S. & Sandeep, N. Switched-capacitor-based seven-level inverter with reduced component count and current stress. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 5(1), 2–7 (2023).

Jakhar, A., Sandeep, N. & Verma, A. K. Common-ground-type inverter topology with low voltage stress and boosting ability. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 71(5), 2854–2858 (2024).

Gopinath, N. P., Azhagumurugan, R., Sathik, M. J. & Kirubakaran, D. Low cost and compact six-switch seven-level grid-tied transformerless PV inverter. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 8841 (2025).

Barzegarkhoo, R. et al. Nine-level nine-switch common-ground switched-capacitor inverter suitable for high-frequency AC-microgrid applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(5), 6132–6143 (2021).

Sarwer, Z., Anwar, M. N. & Sarwar, A. A nine-level common ground multilevel inverter (9L-CGMLI) with reduced components and boosting ability. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 51(8), 3826–3840 (2023).

Jakhar, A., Sandeep, N. & Verma, A. K. Common-ground-type quadruple boosting nine-level inverter. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Srivastava, A. & Seshadrinath, J. A new nine-level highly efficient boost inverter for transformerless grid-connected PV application. IEEE. J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 11, 2730–2741 (2023).

Narayanan Pandurangan, G. & Vijayakumar, K. Dual-ground transformerless nine-level dynamic voltage boosting inverter topology. Int. J. Electron. 111, 677–696 (2024).

Singh, D. & Sandeep, N. A 13-level switched-capacitor-based common-ground boosting inverter. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 71, 3990–3994 (2024).

Samadaei, E., Kaviani, M. & Bertilsson, K. A 13-levels module (K-Type) with two DC sources for multilevel inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66, 5186–5196 (2019).

Siddique, M. D., Mekhilef, S., Sarwar, A., Alam, A. & Shah, N. M. Dual asymmetrical dc voltage source based switched capacitor boost multilevel inverter topology. IET Power Electron. 13, 1481–1486 (2020).

Roy, T. & Sadhu, P. K. A step-up multilevel inverter topology using novel switched capacitor converters with reduced components. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 236–247 (2021).

Islam, S., Siddique, M. D., Iqbal, A., Mekhilef, S. & Al-Hitmi, M. A switched capacitor-based 13-level inverter with reduced switch count. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 58, 7373–7383 (2022).

Wasiq, M., Siddique, M. D., Sarwar, A., Iqbal, A. & Mekhilef, S. A three-fold boost 13-level switched-capacitor based multi-level inverter topology for solar PV applications. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 50, 4434–4458 (2022).

Ahmed, M. S., Raushan, R. & Ahmad, M. W. An inductor less three-fold boost 13-level switched capacitor inverter with reduced ripple current. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 9891–9901 (2024).

Mansourizadeh, H., Hosseinpour, M., Seifi, A. & Shahparasti, M. A 13-level switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverter with reduced components and inrush current limitation. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–24 (2025).

Alnuman, H. et al. A single-source switched-capacitor 13-level high gain inverter with lower switch stress. IEEE Access 11, 38082–38093 (2023).

Sandeep, N. A 13-level switched-capacitor-based boosting inverter. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II(68), 998–1002 (2021).

Islam, S., Siddique, M. D., Iqbal, A. & Mekhilef, S. A 9- and 13-Level switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverter with enhanced self-balanced capacitor voltage capability. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 10, 7225–7237 (2022).

Anand, V. & Singh, V. A 13-Level Switched-Capacitor Multilevel Inverter with Single DC Source. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 10, 1575–1586 (2022).

Samizadeh, M. et al. A new topology of switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with eliminating leakage current. IEEE Access 8, 76951–76965 (2020).

Barzegarkhoo, R., Lee, S. S., Khan, S. A., Siwakoti, Y. & Lu, D. D. C. A novel generalized common-ground switched-capacitor multilevel inverter suitable for transformerless grid-connected applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36, 10293–10306 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Yao, J. & Ioinovici, A. Switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with input source-load common ground for applications supplied by green energy. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 71, 186–190 (2024).

Tarzamni, H., Gohari, H. S., Sabahi, M. & Kyyra, J. Nonisolated high step-up DC-DC converters: Comparative review and metrics applicability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 582–625 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (PURSE), under Award SR/PURSE/2021/65. Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, India [SR/PURSE/2021/65].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH, SB, NPG, MJS: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Software, Visualisation, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. NPG, MJS: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. SH, NPG, MJS: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hemalatha, S., Balamurugan, S., Gopinath, N.P. et al. High boost switched capacitor based 13L CG transformerless inverter for cost effective grid integration. Sci Rep 15, 36658 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20309-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20309-x