Abstract

Drinking water with a high iodine content is one of the sources of iodine intake, And excessive iodine intake can affect thyroid function. This study aims to investigate the effects of long-term exposure to iodine-rich groundwater on iodine intake And thyroid function in children. We recruited a total of 3,216 children aged 3–14 years on multiple occasions from 2013 to 2023 from counties with high groundwater iodine concentrations in Shandong Province, China. We collected drinking water samples to measure water iodine concentration (WIC), spot urine samples And 24-hour (24-h) urine samples to examine the iodine status. We measured the thyroid volume and collected fasting blood and dried blood spot samples to examine the thyroid function. The median WIC of children’s drinking water was 183 (IQR 70.0-362) µg/L. Within each age group, all iodine indicators, including urine iodine concentration And 24-hour urine iodine excretion, etc., and thyroid volume increased significantly with increasing water iodine concentration. The odds ratios (ORs) of the impact of drinking water with iodine concentration > 300 µg/L on hyperthyrotropinemia And goiter were 1.77 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20–2.62) And 4.19 (95% CI, 2.68–6.57), respectively. In children, prolonged exposure to an environment with high groundwater iodine content is associated with an increase in thyroid volume, a higher prevalence of goiter, and an increased risk of hyperthyrotropinemia. Continued efforts to reduce iodine concentration in drinking water are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iodine is widely distributed in nature. The main sources of iodine intake in the human body are iodine-rich foods, iodized salt, and iodine-rich water1. Groundwater accounts for one-third of China’s total water resources And serves as the primary source of drinking water for Chinese residents. Approximately 70% of urban residents And over 95% of rural residents primarily drink groundwater2. Therefore, drinking iodine-enriched groundwater may lead to excessive iodine exposure for residents3. The flood-prone areas of the Yellow River are the major areas in China with high groundwater iodine content4. The Yellow River has long been sediment-laden, and a portion of this sediment accumulates in the downstream riverbed. During the floods, iodine carried by the river is eroded from the land and redeposited in floodplains in the southwestern and northwestern parts of Shandong Province, increasing the iodine content of local groundwater4.

Iodine absorbed by the human body is primarily stored in the thyroid gland and exerts its physiological functions through the synthesis of thyroid hormones5,6. Thyroid volume, thyroid hormone and thyroid stimulating hormone levels are the main indicators of thyroid function assessed clinically7. Iodine deficiency can affect thyroid hormone synthesis and cause goiter, which is a global public health issue. The universal salt iodization (USI) strategy to prevent iodine deficiency disorders has significantly improved the health of populations worldwide8. However, many studies have shown that excessive iodine intake can also be harmful9,10,11. Jessica et al. found that excessive iodine intake affects thyroid volume in children and increases the risk of goiter1. Laurberg et al. found that elderly with high iodine intake had lower thyroid hormone levels and were more likely to suffer from subclinical hypothyroidism. As thyroid hormones are involved in the central nervous system and physical development12and children are at the critical stage of development, excessive iodine intake is more detrimental to children13. Excessive iodine intake not only leads to thyroid diseases such as goiter in children but may also contribute to growth retardation14. Goiter in childhood can increase the risk of thyroid nodules in adulthood, and can also cause hypothyroidism15.

Since 2005, China has conducted nationwide surveys of iodine levels in groundwater And found that approximately 30 million people are at risk of iodine excess. In 2017, nationwide survey results showed that the iodine levels in drinking water exceeded the standard in 19 provinces, impacting nearly 400 million people16. However, few large-scale epidemiologic studies have been conducted to explore the impact of prolonged exposure to iodine-enriched groundwater on thyroid function in children.

The southwestern and northwestern parts of Shandong Province, located in the Yellow River floodplain, include extensive areas with high groundwater iodine content4. We recruited children aged 3–14 years from these high-iodine areas and assessed their iodine status. We evaluated the impact of iodine-enriched groundwater on their thyroid function. We aimed to guide the formulation of policies to control the iodine levels of groundwater in areas with high groundwater iodine content, thus safeguarding public health.

Methods

Study population

The study recruited children aged 3–14 years on multiple occasions from 2013 to 2023 from counties with high iodine levels in groundwater in Shandong Province, China. Each county was divided into five districts (eastern, southern, western, northern, and central). We randomly selected one primary school or kindergarten from each district as a survey site. Healthy children aged 3–14 years attending the selected schools were screened And recruited through cluster sampling. Children with thyroid disease or taking iodine-containing medication were excluded. A total of 3,216 local children were recruited. Written informed consents were obtained from the parents of all participating children. The Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University approved the survey (No. TMUhMEC 2022011). The authors confirm the study was completed following approved protocol, University regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exposure assessments

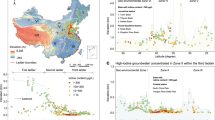

According to China’s “Delineation of Endemic Areas of High Iodine in Water and Iodine-Related Diseases” (GB/T 19380 − 2003 and GB/T 19380 − 2016), areas with iodine concentration in drinking water above 100 µg/L are considered as high-iodine water areas, while those exceeding 300 µg/L are identified as high-iodine disease-endemic areas4,17. The Shandong Iodine Deficiency Disease Control Center collected And tested the iodine concentration in groundwater from various counties in Shandong Province in both 2013 And 2023. The WIC for 2013 And 2023 in each county are shown in the Additional file. Utilizing the GeoScene (Version 2.1; GeoScene Information Technology Co., Ltd.; URL: https://edutrial.geoscene.cn/geoscene/trial/GeoScenePro.html), we generated the geographical distribution map of water iodine concentration (WIC) across counties in Shandong Province, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Based on the 2013 monitoring data from the Shandong Iodine Deficiency Disease Control Center, most of the areas in Shandong province were designated as high-iodine water areas (Fig. 1(a)). The government has widely implemented projects to improve water quality, And iodine in drinking water has been successfully reduced in many parts of Shandong. Despite these efforts, many high-iodine water areas remained in southwestern Shandong in 2023 (Fig. 1 (b)).

Geographical distribution of iodine concentrations in public drinking water across various counties of Shandong Province. a Geographical distribution of iodine concentrations in public drinking water across various counties of Shandong Province in 2013; b Geographical distribution of iodine concentrations in public drinking water across various counties of Shandong Province in 2023. The regions highlighted in black boxes indicate the cities of Liaocheng and Heze. WIC, water iodine concentration.

Children were recruited from Heze and Liaochen, which were classified as high WIC areas from 2013 to 2023. The permanent resident population of Heze City and Liaocheng City is approximately 14.45 million, with children aged 3–14 accounting for about 23.47% to 25.10% of the total population. A 5 ml sample of each child’s daily drinking water was collected in a polyethylene plastic bottle for testing iodine concentration. We estimated the daily water intake amount by dividing the twenty-four-hour (24-h) urine volume by 0.7118. The daily water iodine intake (WII) was calculated by multiplying the estimated water intake by the WIC.

Outcome assessments

Demographic characteristics

The height and weight of the subject children were measured using an electronic height and weight meter (TCS-200 SuHeng). Height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm, And weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body Mass Index (BMI, kg/m²) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Information about gender, age, home address, and medical history was collected through parental questionnaires.

Thyroid function

Fasting blood samples were obtained from children aged 7–14 years, while dried blood spot samples (DBS) were obtained from children aged 3–6 years. Due to the young age of the children (3–6 years), venous blood sampling is not practical. Only thyrotropin (TSH) was detected in DBS. DBS was obtained by spotting whole blood from a finger stick onto filter paper (grade 903; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) And drying at room temperature for 24 h. The concentrations of serum TSH, free thyroxine (FT4), free triiodothyronine (FT3), And thyroid Antibodies were Analyzed to evaluate the thyroid function of 7−14-year-old children. The definition of hyperthyrotropinemia is TSH > 5.0mIU/L with FT4 normal.

Thyroid volume and goiter

Trained medical personnel used the Hawk HY5511 (Hai Ying Electronics Co) ultrasound service to measure thyroid volume (Tvol). We measured the length (l), width (w), and depth (d) of the thyroid’s left and right lobes; the volume of each lobe could be calculated as follows: V (ml) = 0·479 × d(mm) × w(mm) × l(mm) × 0·00119. Tvol was calculated as the sum of the volume of the left and right lobes, excluding the thyroid isthmus. The Chinese “Diagnostic Criteria of Endemic Goiter” (WS 276–2007) establish age-specific diagnostic criteria for goiter, utilizing ultrasonography to ascertain thyroid volume. Goiter was defined according to the criterion.

Iodine status

Spot And 24-hour urine samples were measured for urine iodine concentration (UIC) and creatinine (UCr). As spot urine samples, 10 mL of fresh midstream urine was collected from each child using polyethylene plastic cups. All urine voided by the children over the subsequent 24 h was collected in polyethylene bottles; after mixing thoroughly, two 5-ml urine samples were extracted. All urine samples were stored at −20 °C after collection until they were tested within one week. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, children with a spot UIC > 300 µg/L may be at risk of iodine excess20. We calculated 24-h urine iodine excretion (UIE) by multiplying 24-h UIC by urine volume. According to an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, approximately 92% of human iodine is excreted through the kidneys21. Therefore, the daily iodine intake (DII) was approximated by dividing UIE by 0.92. The urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio (µg/g) was calculated as the spot UIC/spot UCr (UI/Cr). In addition, serum total iodine (StI) and serum non-protein-bound iodine (SnbI) were measured in blood samples.

Laboratory analyses

DBS samples were analyzed for TSH using the DELFIA NeoTSH method on a multi-label counter fluorescence immunoassay analyzer (PerkinElmer)22. The reference ranges for the TSH of DBS are 0.1–3.7 mIU/L. The intra-assay Coefficient of Variations (CVs) And the inter-assay CVs for DBS-TSH were 3.2%−16.1% And 5.7%−17.8%. For venous blood samples, we used ADVIA Centaur automated chemiluminescence immunoassays (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) to analyze TSH, FT4, and FT3. We used An IMMULITE 2000 system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) to detect serum thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies by chemiluminescence reaction. The tests were conducted by the clinical laboratory of the Tianjin Women and Children’s Health Center. The intra-assay CVs for serum TSH, FT4, FT3, thyroid peroxidase antibody, and thyroglobulin (Tg) Antibody were 3.1–5.7%, 3.1–5.5%, 2.1–4.7%, 4.6–6.1%, And 3.1–5.2%. The reference ranges are 4.78–6.96 pmol/L for FT3, 13.4–20.6 pmol/L for FT4, And 0.3–5 mIU/L for TSH.

We used inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; iCAP Q, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to determine UIC, WIC, StI, and SnbI. Blood proteins were precipitated with acetonitrile (acetonitrile: serum = 50 µL: 25 µL) to detect SnbI. The intra-assay CVs for UIC, WIC, StI, And SnbI were 0.8–1.5%, 0.7–1.5%, 1.2–3.6%, And 1.1–1.8%, respectively. We used national standard spectrophotometry to determine UCr, And the CV of UCr concentrations in the laboratory ranged from 1.2% to 4.5%. The Tianjin Key Laboratory of Environmental Nutrition and Population conducted the relevant tests.

Statistical analyses

Referring to the 2023 Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes for iodine23., children were categorized into three age groups—3–6 years, 7–10 years, And 11–14 years—using 7 And 11 years as cutoff points, to analyze the distribution of iodine nutritional status and thyroid function. The normality of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as means (standard deviation), while non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as variables and interquartile ranges (IQR). We used ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis, or chi-squared tests to analyze the variables’ differences among age and WIC groups. Growth and development are influenced by thyroid function, so age, sex, and anthropometric measures are commonly adjusted as conventional factors in thyroid disease studies24,25,26. Multivariable logistic regression models were employed, adjusting for age, sex, And BMI, to evaluate the effects of WIC And a 10 µg/d or 50 µg/d increase in WII on the risk of hyperthyrotropinemia, positivity for either thyroglobulin or thyroid peroxidase antibody and whether goiter occurs. All models were examined for multicollinearity, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable was below 1.5. We used the generalized additive model (GAM) to Analyze the relationship between WIC And Tvol. GeoScene V 2.1 was used to visualize and analyze the data of water iodine concentrations in the counties of Shandong Province. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to assess the predictive ability of WIC and WII for UIC > 300 µg/L, goiter rate, and hyperthyrotropinemia. Incorporating both WIC and WII into the model as the “Model”. An area under the curve (AUC) greater than 0.6 was considered predictive. P values are reported as two-sided. SPSS, 26.0, And SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute) were used for all the statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 3,216 children were recruited (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the distribution of water iodine concentrations in the counties of Shandong Province in 2013 And 2023. The counties of Heze and Liaocheng in the southwest were continuously exposed to high-iodine water in 2013 And 2023. Most (71%) of the study population was exposed to drinking water with iodine concentrations above 100 µg/L.

The median WIC of children’s drinking water was 183 (IQR 70.0-362) µg/L. As shown in Table 1, WIC differed by age group, being higher in children aged 11–14 years old (277 (IQR 122, 460) µg/L) than in younger children. The median DII of children was 253 (IQR 138, 453) µg/day, while the median WII was 147 (IQR 50, 351) µg/day. Water iodine accounted for approximately 61% of the total iodine intake and increased significantly with age (48% in children aged 3–6 years, 58% in those aged 7–10 years, And 80% in those aged 11–14 years, P < 0.001). The median spot UIC in children was 443 (IQR 201–768) µg/L. Spot UIC was higher in the 11–14 years old children than in the younger groups. UIE was increased with age (P < 0.001). FT3 and FT4 were higher in 7–10 years old children than in 11–14 years old children, whereas no differences in serum iodine concentration And TSH were observed among age groups. 224 (10.8%) children had hyperthyrotropinemia, And 159 (7.7%) had positive thyroid antibodies; the prevalence of TSH elevation and antibody positivity did not differ by age group.

Within each age group, all urinary iodine indicators, including spot UIC, UI/Cr, 24-h UIC, And 24-h UIE, increased with WIC (Table 2). WIC was positively correlated with spot UIC (r = 0.54, P < 0.001), UI/Cr (r = 0.46, P < 0.001), And 24-h UIE (r = 0.55, P < 0.001), indicating that iodine intake in children increased with iodine content in drinking water. Serum iodine concentrations were not associated with WIC. In the 7–11 age group, as WIC increased, FT3 decreased slightly and FT4 increased. In the 11–14 age group, as WIC increased, FT3 decreased slightly, And TSH increased. The incidence of hyperthyrotropinemia increased with WIC in the 11–14 age group (Table 2). The results of the GAM showed that the effects of the WIC on Tvol were statistically significant. According to Fig. 2, in children aged 3–6 years, when WIC was less than 500 µg/L, Tvol did not change significantly. When WIC was above 500 µg/L, Tvol increased steeply. In children aged 7–10 years And 11–14 years, Tvol increased with increasing WIC until WIC reached 600 µg/L.

The impact of WIC on Tvol in children based on GAM. (a) The impact of WIC on Tvol in children aged 3–6 years (b) The impact of WIC on Tvol in children 7–10 years (c) The impact of WIC on Tvol in children aged 11–14 years. The images show the fitted curves of the model with 95% CIs. a coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.166, estimated degrees of freedom (edf) is 3.72, P = 0.040. b coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.537, estimated degrees of freedom (edf) is 2.64, P < 0.001. c: coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.563, estimated degrees of freedom (edf) is 6.94, P < 0.001. CIs, confidence interval; Tvol, thyroid volume; WIC, water iodine concentration; GAM, generalized additive model.

As shown in Table 3, the odds ratios (ORs) of the impact of drinking water with an iodine concentration > 300 µg/L on hyperthyrotropinemia was 1.77 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20–2.62). However, each 10–50 µg increase in WII was not associated with hyperthyrotropinemia. The ORs of the impact of drinking water with An iodine concentration above 300 µg/L And WII increases by each 10 µg And 50 µg on goiter were 4.19 (95%CI: 2.68–6.57), 1.02 (95%CI: 1.01–1.02) And 1.08 (95%CI: 1.06–1.10), respectively. Neither WIC nor WII correlated with thyroid antibody positivity.

ROC curves were used to assess the predictive ability of WIC and WII for UIC > 300 µg/L, goiter rate, and hyperthyrotropinemia. As shown in Fig. 3, for UIC > 300 µg/L, a cut-off value of WIC was 202 µg/L, with a sensitivity of 60.0% And specificity of 85.0%, And An AUC of 0.771, while a cut-off value of WII was 158 µg/day, with a sensitivity of 64.7% And specificity of 73.8% And An AUC of 0.746. For goiter, a cut-off value of WIC was 410 µg/L, with a sensitivity of 50.5% And specificity of 78.8%, And An area under the curve of 0.660. The cut-off value of WII was 346 µg/day, with a sensitivity of 59.2% And specificity of 70.0%, And An area under the curve of 0.669. For hyperthyrotropinemia, both the AUC of WIC And WII were below 0.6, ROC analyses showed that WIC and WII were poor predictors of hyperthyrotropinemia.

The ROC curves for assessing the predictive ability of WIC and WII for spot UIC > 300 µg/L (a), goiter rate (b), and hyperthyrotropinemia (c). Children with a spot UIC > 300 µg/L may be at risk of iodine excess. Incorporating both WIC and WII into the model as the “Model”. WIC, water iodine concentration; WII, water iodine intake; UIC, urinary iodine concentration.

Discussion

According to the large-scale epidemiological investigation, children with prolonged exposure to iodine-enriched groundwater are at risk of iodine excess. Drinking iodine-enriched groundwater is associated with a significant rise in Tvol and an increased prevalence of goiter in children. In addition, excessive iodine exposure can lead to elevated TSH levels.

China is one of 13 countries in the world with the most widespread distribution of areas of high groundwater iodine content globally, affecting a significant population3,27. Due to the implementation of the USI strategy, even in areas with low water iodine levels, the salt available for home consumption was iodized28. Yang et al. found that adults in areas with low water iodine have adequate iodine status. In contrast, in areas with high water iodine levels, the combined consumption of drinking water with excess iodine and iodized salt can lead to excessive iodine intake29. The median WIC for children in our study was 183 (IQR: 70.0-362) µg/L. According to WHO criteria, children with spot UIC ≥ 300 µg/L were at risk of iodine excess20. The children’s spot UIC was 443 (IQR: 201, 768) µg/l. Children exposed to iodine-enriched groundwater are more susceptible to iodine excess. Notably, we found that children’s iodine intake from water accounted for 61% of their total iodine intake, which gradually increased with age. Wang et al. found that drinking water contributed to 58.2% of iodine intake in areas with WIC in the range of 150 to 300 µg/L30. In 2009, 14 counties with high groundwater iodine levels implemented a strategy to stop providing iodized salt. However, these areas are still at risk of iodine excess30. For children in particular, iodine intake from drinking water is significantly higher than from iodized salt31. Therefore, simply discontinuing the supply of iodized salt is not sufficient to address children’s iodine excess issues in areas with high groundwater iodine content. Some areas have built reservoirs to store low-iodine water as a means of replacing drinking water sources, thereby reducing WIC in drinking water29,30,32,33.

Research suggests that excessive iodine intake inhibits the release of thyroid hormones and the feedback process of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis increases serum TSH34,35,36,37. However, changes in serum thyroid hormones and serum TSH occurred at higher doses of iodine exposure. Gardner et al. found that An increase in TSH was observed at a dose of 500 µg/d iodine exposure, whereas a decrease in FT4 was only observed at a dose of 1500 µg/d iodine exposure38. In our study, we observed an association between high-water iodine exposure and decreased FT3 levels. Only the highest level of water iodine exposure, when WIC is greater than 300 µg/L, has an affect on hyperthyrotropinemia. The ORs of the impact of drinking water with iodine concentration > 300 µg/L on hyperthyrotropinemia was 1.77 (95% CI, 1.20–2.62). Although there were slight but significant differences in TSH levels among children aged 11–14 years across different WIC categories, WIC and water iodine intake were not significant predictors of hyperthyrotropinemia. Serum TSH is a relatively insensitive marker for iodine status39.

Since both iodine deficiency and iodine excess can cause an increase in TSH secretion, which stimulates compensatory hyperplasia of the thyroid tissue and increases thyroid volume, thyroid volume is considered to reflect the long-term iodine nutritional status of the population40,41. WHO recommends using the total goiter rate to determine the severity of iodine deficiency and excess in populations20,40. In our study, An increased risk of goiter in children was observed when WIC exceeded 300 µg/L or when WII increased. In children aged 3–6 years, there was no significant change in Tvol when WIC was less than 500 µg/L. A positive correlation with Tvol was observed when WIC exceeded 500 µg/L. Given that changes in Tvol typically lag behind changes in iodine intake1the Duration of excess iodine exposure in younger children may not have been sufficient to detect changes in Tvol at less extreme exposure levels. There were significant differences in Tvol among children aged 7–10 years across different WIC ranges. We found that the Tvol tended to stabilize at WIC levels above 600 µg/L. Although high WIC can cause an increase in Tvol, this increase is not unlimited due to long-term effects such as thyroid tissue sclerosis16. Notably, our study found a higher risk of goiter in younger children, which is consistent with previous research16.

Excessive iodine intake can lead to the development of autoimmune thyroid disease42,43. However, some individuals may have autoimmune thyroid disease without being positive for thyroid autoantibodies34. Sang et al. found that the rate of thyroid autoantibody positivity was higher among children living in high WIC areas than among children living in iodine-sufficient areas35. However, Wang et al. reported no significant difference in the antibody positivity rate among children in areas with different iodine exposure30. This finding is consistent with the results of our study. We found no difference in thyroid autoantibody positivity among children with different iodine levels and water iodine intake. More evidence is needed to explore the relationship between excessive iodine intake and thyroid antibodies.

The strength of this study lies in its large and representative survey population. A comprehensive collection of biochemical indicators and a detailed assessment of water iodine status at the survey sites distinguish it from previous studies. However, this study has limitations. Because of its cross-sectional design, we cannot establish a causal relationship between WIC and thyroid function. Non-cooperative participants introduced non-response bias, but we mitigated this by conducting multiple rounds of recruitment. The only reason why children who met the inclusion criteria did not participate was the lack of consent forms. In addition, we collected limited information on potential confounders. It is impractical to collect detailed dietary and personal information from children, so although our questionnaire included questions about children’s consumption of iodized salt, we couldn’t quantify iodine intake from dietary sources.

In conclusion, our study identified the persistence of areas with high groundwater iodine content in Shandong Province, China. Children continue to be at risk of iodine excess due to exposure to iodine-rich groundwater. For children, prolonged exposure to high WIC may lead to increased Tvol and goiter prevalence and increased risk of hyperthyrotropinemia. Water sources should be changed to reduce iodine concentrations in drinking water.

Data availability

Additional datasets collected and analyzed for this research can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Farebrother, J., Zimmermann, M. B. & Andersson, M. Excess iodine intake: sources, assessment, and effects on thyroid function. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1446, 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14041 (2019).

Feng, F. et al. Hydrogeochemical and statistical analysis of high fluoride groundwater in Northern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 34840–34861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09784-z (2020).

Zimmermann, M. B. & Andersson, M. Global Endocrinology: Global perspectives in endocrinology: coverage of Iodized salt programs and iodine status in 2020. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 185, R13-r21. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-21-0171 (2021).

Hou, X. et al. Distribution of iodine concentration in drinking water in China Mainland and influence factors of its variation. Sci. Total Environ. 892, 164628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164628 (2023).

Forhead, A. J. & Fowden, A. L. Thyroid hormones in fetal growth and prepartum maturation. J. Endocrinol. 221, R87–r103. https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-14-0025 (2014).

Zimmermann, M. B. The role of iodine in human growth and development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.009 (2011).

Zimmermann, M. B., Jooste, P. L. & Pandav, C. S. Iodine-deficiency disorders. Lancet (London England). 372, 1251–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61005-3 (2008).

Gorstein, J. L., Bagriansky, J., Pearce, E. N., Kupka, R. & Zimmermann, M. B. Estimating the health and economic benefits of universal salt Iodization programs to correct iodine deficiency disorders. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 30, 1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2019.0719 (2020).

Zimmermann, M. B. & Boelaert, K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. Lancet Diabets Endocrionol. 3, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(14)70225-6 (2015).

Koukkou, E. G., Roupas, N. D. & Markou, K. B. Effect of excess iodine intake on thyroid on human health. Minerva Med. 108, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4806.17.04923-0 (2017).

Leung, A. M. & Braverman, L. E. Consequences of excess iodine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.251 (2014).

Alcaide Martin, A. & Mayerl, S. Local thyroid hormone action in brain development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241512352 (2023).

Campanozzi, A. et al. Iodine deficiency among Italian children and adolescents assessed through 24-hour urinary iodine excretion. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1080–1087. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy393 (2019).

Aakre, I., Strand, T. A., Moubarek, K., Barikmo, I. & Henjum, S. Associations between thyroid dysfunction and developmental status in children with excessive iodine status. PLoS One. 12, e0187241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187241 (2017).

Pearce, E. N. Iodine deficiency in children. Endocr. Dev. 26, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363160 (2014).

An, S. et al. Relationship between water iodine and children’s goiters. Br. J. Nutr. 128, 1798–1805. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114521004529 (2022).

Shen, H. et al. Geographical distribution of drinking-water with high iodine level and association between high iodine level in drinking-water and goitre: a Chinese National investigation. Br. J. Nutr. 106, 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114511000055 (2011).

Bernard, J., Song, L., Henderson, B. & Tasian, G. E. Association between daily water intake and 24-hour urine volume among adolescents with kidney stones. Urology 140, 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.01.024 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Appropriate range of median urinary iodine concentration in 8- to 10-Year-Old children based on generalized additive model. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 30, 1535–1540. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2019.0813 (2020).

WHO & UNICEF. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers, 3rd ed (2007).

Hurrell, R. F. Bioavailability of iodine. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 51 (Suppl 1), 9–12 (1997).

Baloch, Z. et al. Laboratory medicine practice guidelines. Laboratory support for the diagnosis and monitoring of thyroid disease. Thyroid: Official J. Am. Thyroid Association. 13, 3–126. https://doi.org/10.1089/105072503321086962 (2003).

Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes (The People’s Health Press Co., Ltd, 2023).

Babić Leko, M., Gunjača, I., Pleić, N. & Zemunik, T. Environmental factors affecting thyroid-Stimulating hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126521 (2021).

Tian, C. et al. Iodine nutrition and the prevalence status of thyroid nodules in the population: a Cross-sectional survey in Heilongjiang province, China. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199, 3181–3189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-020-02442-y (2021).

Li, X. et al. Iodine nutritional status and thyroid autoimmunity in chinese children and adolescents aged 6–17 years. Nutrients 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213720 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. How did we eliminate the hazards of water-borne excessive iodine in Northern China?? Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115795 (2024).

Azevedo, F. M. et al. Correlation between drinking water and iodine status: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-022-03127-4 (2023).

Du, Y. et al. What iodine intervention measures should be taken in different water iodine areas?? Evidence from a Cross-sectional Chinese survey. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 4654–4663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-03050-0 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Stopping the supply of Iodized salt alone is not enough to make iodine nutrition suitable for children in higher water iodine areas: A cross-sectional study in Northern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 188, 109930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109930 (2020).

Lv, S. et al. Goitre prevalence and epidemiological features in children living in areas with mildly excessive iodine in drinking-water. Br. J. Nutr. 111, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114513001906 (2014).

Liu, P. et al. The standard, intervention measures and health risk for high water iodine areas. PloS One. 9, e89608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089608 (2014).

Liu, L., Liu, J., Wang, D., Shen, H. & Jia, Q. Effect of urinary iodine concentration in pregnant and lactating women, and in their infants residing in areas with excessive iodine in drinking water in Shanxi province, China. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 193, 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-019-01716-4 (2020).

Laurberg, P. et al. Iodine intake as a determinant of thyroid disorders in populations. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 24, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.013 (2010).

Sang, Z. et al. Long-term exposure to excessive iodine from water is associated with thyroid dysfunction in children. J. Nutr. 143, 2038–2043. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.179135 (2013).

Sang, Z. et al. Exploration of the safe upper level of iodine intake in euthyroid Chinese adults: a randomized double-blind trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 367–373. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.028001 (2012).

Vitale, M. et al. Iodide excess induces apoptosis in thyroid cells through a p53-independent mechanism involving oxidative stress. Endocrinology 141, 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.141.2.7291 (2000).

Gardner, D. F., Centor, R. M. & Utiger, R. D. Effects of low dose oral iodide supplementation on thyroid function in normal men. Clin. Endocrinol. 28, 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb01214.x (1988).

Pearce, E. N. & Caldwell, K. L. Urinary iodine, thyroid function, and thyroglobulin as biomarkers of iodine status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104 (Suppl 3), 898s–901s. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.110395 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Associations between iodine intake, thyroid volume, and goiter rate in school-aged Chinese children from areas with high iodine drinking water concentrations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 228–233. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.139725 (2017).

Zimmermann, M. B. & Andersson, M. Assessment of iodine nutrition in populations: past, present, and future. Nutr. Rev. 70, 553–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00528.x (2012).

Ferrari, S. M., Fallahi, P., Antonelli, A. & Benvenga, S. Environmental issues in thyroid diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00050 (2017).

Prete, A., Paragliola, R. M. & Corsello, S. M. Iodine Supplementation: Usage with a Grain of Salt. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 312305. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/312305 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Shandong Iodine Deficiency Disease Control Center for its strong support and help in the field investigation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [NSFC Grant No.82273629] and the Tianjin Key Laboratory of Environment, Nutrition, and Public Health [2020ENKL01].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhang Wanqi: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. Chen Wen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. Yang Rui: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. Lv Dongping: Investigation. Wang Xiaoming: Investigation. Elizabeth N. Pearce: Writing - Review & Editing. An Dong: Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Parents or guardians were required to provide written informed consent and to sign informed consent regarding publishing children’s data and photographs. The Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University approved the survey (No. TMUhMEC 2022011).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, R., Lv, D., Wang, X. et al. Assessment of the association of high-iodine exposure in drinking water, iodine intake, and thyroid function in 3−14-year-old children. Sci Rep 15, 36625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20327-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20327-9