Abstract

V. parahaemolyticus poses a remarkable public health threat, accounting for approximately 25% of global seafood-related infections in human consumers and resulting in severe infections and substantial economic losses in the aquaculture. To explore the prevalence, antibiogram, virulence and resistance genes, the multidrug resistance profiles, and the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus recovered from shrimp, 200 Litopenaeus vannamei (clinically healthy: n = 100 and diseased: n = 100) were gathered from commercial shrimp farms in Ismailia, Egypt. Accordingly, clinical and postmortem findings and bacteriological examinations were performed. All the recovered isolates were positive for the groEL and Ap3 genes, indicating that all the retrieved isolates were AHPND-causing strains. The prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus in the examined shrimp was 11% (22/200), where the hepatopancreas was the prominent infected organ. Using PCR, the prevalence of the toxR, tlh, tdh, and trh virulence genes was 100%, 98%, 80%, and 28%, respectively. Moreover, 42% of the obtained V. parahaemolyticus strains were MDR to seven antimicrobial classes and had the blaTEM, tetA, blaOXA, sul1, aadA, and ermB genes. In addition, 16% of the isolated strains were MDR to six classes and had the blaTEM, tetA, blaOXA, aadA, and ermB genes. The pathogenicity trial emphasized the positive correlation between the inherited virulence genes of the tested strains and the recorded mortalities. In brief, this investigation highlighted the development of MDR V. parahaemolyticus in shrimp, affirming a public health threat. The evolving MDR V. parahaemolyticus strains usually carry the Ap3, toxR, tlh, and tdh virulence genes, and the ermB, blaTEM, aadA, blaOXA, sul1, tetA, and/or tetB antibiotic resistance genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shrimp rank among the most economically significant seafood commodities globally, with their aquaculture sector experiencing remarkable expansion over the past three decades1. This growth has been particularly pronounced in tropical and subtropical regions, where advancements in farming techniques, genetic selection, and disease management have driven increased production and market demand2.

Among farmed shrimp, Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) dominate global aquaculture owing to their wide salinity adaptability, appealing flavor profile and fast growth rate3,4. In 2020, Egypt’s total shrimp production was estimated at 8,614 tons from wild fisheries and 2,164 tons from cultured L. vannamei5. With capture fisheries yielding limited growth potential, the emphasis has shifted toward intensifying shrimp aquaculture to meet rising global demand. However, the expansion of intensive farming systems has introduced a range of stressors, resulting in an increase in of bacterial infections that present significant risks to L. vannamei yield6.

Among the most formidable pathogens in shrimp aquaculture, Vibrio parahaemolyticus poses a critical threat to several farmed shrimp species7. This virulent pathogen is the causative agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND), a devastating disorder characterized by high mortalities and substantial economic damage, significantly influencing global shrimp production8,9. Initially, recorded in China in 2009, AHPND quickly blows out across neighboring nations10, triggering severe epizootics in shrimp farms throughout Asia and North America11,12,13. More recently, it was recorded in Egypt14,15. In addition to its devastating impact on shrimp aquaculture, V. parahaemolyticus poses significant public health risks, accounting for approximately 25% of global seafood-related infections16,17. The pathogen is recognized as a significant agent of foodborne illness linked to the intake of raw, undercooked, or contaminated seafood18. Human infections range from gastroenteritis to wound infections and, in severe cases, septicemia19.

AHPND manifests through a distinct evolution of clinical symptoms, originally presenting as a decrease in feed consumption and sluggishness before advancing to acute symptoms, including an unfilled belly and midgut20. The terminal-stage indicators include an atrophied hepatopancreas, a milky stomach, a vacuous gut, and soft shells20,21. The pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus is driven by a combination of potent exoenzymes, toxins, and virulence determinants. Pathogenic strains carry a 69-kb plasmid encoding two related insect-derived toxins, Photorhabdus PirA and PirB, which exert a pivotal role in disease propagation22,23. Additionally, the bacterium possesses a diverse arsenal of virulence tools associated primarily with red blood cell lysis and cell toxicity24. Key hemolysins such as tdh, trh, and tlh, significantly contribute to its pathogenic potential25.

PCR remains an essential molecular tool for the precise recognition of virulent bacteria and their inherited virulence genes26. In V. parahaemolyticus, the groEL gene is recognized as a reliable indicator for the identification of species-specific pathogens. Primers targeting this gene demonstrate high specificity and sensitivity, enabling the precise detection of purified bacterial DNA and contaminated tissue samples27. Antimicrobials have traditionally been employed to treat AHPND; however, their extensive usage has contributed to the rise of MDR strains in aquatic environments, diminishing treatment efficacy and complicating disease management28. Increasing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents an evolving hazard to food safety and public concern29,30,31. Although previously liable to greatest antibiotics32, recent reports highlight its resistance to multiple antimicrobial classes29,33,34, underscoring the pressing need for alternative disease management strategies. The pervasive and persistent application of antimicrobial agents has raised concerns regarding the possible handover of superbugs from land-based to aquaculture35,36,37.

Vibrios, including V. parahaemolyticus, serve as reservoirs for growing resistance genes, facilitating the horizontal transfer of transposable elements between aquatic creatures and their environment38. This pathogen displays miscellaneous patterns of resistance and harbors an array of resistance genes39,40, contributing to the rise of MDR strains that pose significant epidemiological risks. However, gaps persist in our thoughtful regarding its pathogenicity, transmission dynamics, and molecular mechanisms underpinning antimicrobial resistance. This study seeks to bridge these knowledge gaps by exploring the frequency, molecular characteristics, virulence determinants, and resistance genes of V. parahaemolyticus recovered from L. vannamei.

Materials and methods

Animal ethics

The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All methods were performed according to relevant guidelines and regulations. The handling of the shrimp and all the experimental protocols were conducted by well-trained scientists and were approved by The Scientific Research Ethics Committee, Suez Canal University, Egypt (Approval no.: SCU-VET 2022049).

Sampling, clinical and postmortem examinations

Two hundred shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) (apparently healthy: n = 100 and diseased: n = 100) were randomly gathered from four commercial shrimp farms (25 apparently healthy and 25 diseased shrimp per farm) and from the same location in Ismailia, Egypt, from July to October 2023. The farm location was selected on the basis of a previous history of recurrent infections with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. The collected shrimp were transported in iceboxes to the laboratory. Clinical and postmortem examinations were performed41. Besides, gill, hepatopancreas, and gut samples were gathered from each shrimp for bacteriological examination.

Bacteriological examination

A loopful of hepatopancreas, gill, and gut tissue samples was aseptically inoculated into alkaline peptone water and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h for enrichment. Following incubation, a loopful of the enriched culture was streaked onto Thiosulfate Citrate Bile Salts Sucrose (TCBS) agar (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h42,43. The recovered green colonies were presumptively identified as Vibrio species on the basis of their distinct morphological characteristics. Further identification of the obtained isolates was performed via a combination of culture, microscopic, and biochemical analyses, including Gram staining, motility assessment, and a panel of biochemical tests such as oxidase, Voges-Proskauer, catalase, arginine dihydrolysis, citrate utilization, indole production, sugar fermentation, growth in 8% NaCl, and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) production44. Species confirmation was achieved through molecular characterization via PCR amplification of the groEL species-specific gene using a designated primer set, as outlined by Hossain27. Furthermore, to distinguish between AHPND-causing and non-AHPND strains, PCR detection of the AP3 encoding gene was performed45. The primer sequences are presented in Table S1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antibiogram of the retrieved isolates was determined via the disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, UK). Ten antimicrobials were tested, including amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC, 30 µg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 µg), erythromycin (E, 15 µg), amoxicillin (AMX, 30 µg), florfenicol (FLO, 30 µg), imipenem (IPM, 10 µg), trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (SXT, 25 µg), enrofloxacin (ENO, 10 µg), gentamycin (CN, 10 µg), and tetracycline (TE, 30 µg) (Oxoid, UK), were tested. Interpretations of the results were carried out according to the CLSI guidelines46. E. coli ATCC 25,922 was used as a reference strain. Besides, the obtained isolates were recognized as multidrug-resistant (MDR) according to Magiorakos47. The MAR index was investigated as previously described48.

PCR-based screening of virulence-related and antimicrobial resistance genes

PCR was used to examine the prevalence of virulence (tlh, tdh, toxR, and trh) and antimicrobial resistance genes (blaTEM, sul, tetA, blaOXA, aadA, tetB, and ermB) in the retrieved strains. DNA extraction was done with a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany). Besides, positive control strains (obtained from The AHRI, Egypt) and negative controls (DNA-free reactions) were included. Agar gel electrophoresis was subsequently performed, after which the gel was photographed. The oligonucleotide sequences (Metabion, Germany) are listed in supplementary Table S1.

Pathogenicity assay

To satisfy Koch’s postulates, 80 clinically healthy adult L. vannamei shrimp (15–17 g), free from external disease symptoms, were obtained from a private farm in Ismailia Governorate. To verify their disease-free status, gill and hepatopancreas samples from five randomly selected shrimp were screened prior to experimentation. The shrimp were then transported alive to the fish disease laboratory and acclimated for five days in separate fiberglass tanks containing sand-filtered seawater (salinity 28 ppt, temperature 25 °C). Following acclimation, the shrimp were allocated to four experimental groups (G1-G4) in duplicate (n = 10 per tank). The challenge groups (G1-G3) received an intramuscular injection (IM) of the overnight culture of virulent V. parahaemolyticus strains (A, B, and C, respectively) at a concentration of (0.05 mL, 1 × 10⁶ CFU/mL)49. Strain (A) harbored the toxR, tdh, trh, and tlh virulence genes, whereas strain (B) carried the toxR, trh, and tlh genes, however strain (C) carried the toxR and tlh genes. On the other hand, G4 (control group) was injected with 0.05 mL of sterile saline. Meanwhile, clinical and postmortem assessments were systematically conducted, cumulative mortality was closely tracked, and bacterial re-isolation from infected shrimp was performed to verify pathogenicity.

Statistical analyses

The data frequency analyses were conducted by the chi-square test with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), where a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, the correlation between the identified resistance genes and antibiotics was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient via R software (corrplot package, version 4.0.2; https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Clinical and necropsy findings

Most naturally infected Litopenaeus vannamei exhibit a spectrum of gross pathological lesions, including cuticular erosion, soft shells (S), and melanized (blackened) spots or streaks within the hepatopancreas (white arrows). Additionally, diffuse brown to black discoloration was evident across the body surface (black arrows) (Fig. 1a). Some shrimp also displayed dark reddish discoloration on the pleopods, periopods, carapace, and tail region (red arrows), along with noticeable destruction of the tail fins and antennal flagellum (black arrows) (Fig. 1b). Internally, some shrimp exhibit an empty stomach, whereas the intestine shows partial or complete absence of food content. Additionally, certain individuals displayed whitish musculature, and in most cases, the hepatopancreas appeared either congested or atrophied (black arrows) (Fig. 1c).

Naturally infected Litopenaeus vannamei exhibiting distinct gross pathological alterations: (a) cuticular erosion, soft shells (S), melanized (blackened) spots or streaks within the hepatopancreas (white arrows), and widespread brown to black discoloration across the body surface (black arrows); (b) dark reddish discoloration on the pleopods, periopods, carapace, and tail region (red arrows), accompanied by evident destruction of the tail fins and antennal flagellum (black arrows); (c) whitish musculature, with the hepatopancreas predominantly appearing either congested or atrophied.

Phenotypic traits and the prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus in the examined shrimp samples

The retrieved strains were Gram-negative curved motile rods. In addition, colonies were green on TCBS. Moreover, the recovered isolates were positive for oxidase, growth on 8% NaCl, indole, and catalase. In contrast, they were negative for citrate utilization, H2S production, lactose and sucrose fermentation, Voges-Proskauer, and arginine hydrolyzation. Herein, all the obtained strains carried the species-specific groEL gene. Moreover, they tested positive for AP3, the toxin-encoding gene associated with AHPND.

The overall prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus among the shrimp was 11% (22/200). The pathogen was only recovered from the examined diseased shrimp. Regarding the prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus among various organs, the most predominant infected organ was the hepatopancreas (44%), followed by the gut (32%), and gills (24%), as described in Table 1; Fig. 2. Statistically, there was no significant variance (p > 0.05) in the prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus in various organs.

Antibiogram of V. parahaemolyticus obtained from shrimp

The retrieved V. parahaemolyticus strains were resistant to amoxicillin (92%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (88%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (84%), gentamycin and tetracycline (80% for each), erythromycin (78%), and ceftriaxone (76%). Moreover, the retrieved strains were sensitive to florfenicol (100%), imipenem (100%), and enrofloxacin (92%), as described in Table 2; Fig. 3. In addition, there was a significant variance (p < 0.05) in the susceptibility of the obtained strains to the tested antimicrobials.

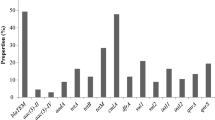

Distribution of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes in V. parahaemolyticus obtained from shrimp

All the retrieved strains from shrimp harbor the toxR and AP3 virulence genes. Besides, the prevalence of the tlh, tdh, and trh virulence genes was 98%, 80%, and 28%, respectively. Moreover, the prevalence of the blaTEM, blaOXA, sul1, aadA, ermB, tetA, and tetB genes was 92%, 88%, 84%, 80%, 78%, 62%, and 18%, respectively, as illustrated in Table 3; Fig. 4. Herein, a significant variance (p < 0.05) was recorded in the propagation of virulence and resistance genes in the obtained isolates. Moreover, origin and distribution patterns of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes among all retrieved V. parahaemolyticus strains from shrimp were illustrated in supplementary Table S2.

In-vitro multidrug resistance profiles and resistance genes of the obtained V. parahaemolyticus from shrimp

In the present study, 42% (21/50) of the obtained V. parahaemolyticus strains were MDR to 7 antimicrobial classes and contained the blaTEM, tetA, blaOXA, sul1, aadA, and ermB genes. Additionally, 16% (8/50) of the recovered strains were MDR to 6 classes and had the blaTEM, tetA, blaOXA, aadA, and ermB genes. Besides, 10% (5/50) of the retrieved strains were MDR to 5 classes and owned the blaTEM, tetB, blaOXA, sul1, and aadA genes. Additionally, 8% (4/50) of the retrieved strains were MDR to 5 classes and had blaTEM, tetB, blaOXA, sul1, and ermB genes (Table 4). Herein, the MAR index values fluctuated from 0.30 to 0.70 (> 0.2), suggesting that the retrieved V. parahaemolyticus from shrimp yields from high-risk contamination. Moreover, strong positive correlations (0.5-1) were observed between CN and the aadA gene, AMX and blaTEM; SXT and sul1; E and ermB (r = 1); TE and tetA (r = 0.64); and AMC and blaOXA (r = 055), as described in Fig. 5.

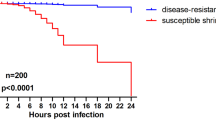

Pathogenicity assay

The mortality rate of the experimentally infected shrimp was closely monitored post-inoculation. Infected shrimp (in the G1- G3 groups) exhibited variable pronounced clinical and necropsy lesions, including dark body discoloration, whitish musculature, and a congested hepatopancreas, closely resembling those observed in naturally infected specimens. Behavioral abnormalities such as erratic swimming, loss of the escape reflex, and eventual immobilization at the tank bottom were also noted.

Undeniably, shrimp inoculated with a virulent strain (A) produced higher mortalities in a shorter time than did those inoculated with other less virulent strains. Specifically, in the G1 group, mortality commenced at 24 h post-injection, reaching 40%, escalating to 80% by 36 h, and culminating in 100% mortality within 48 h. However, in the G2 and G3 groups mortality was delayed and reached 80% and 55%, respectively within 3–4 days post inoculation. These findings underscore the strong correlation between cumulative mortality and the inherited virulence genes of the inoculated strains. In contrast, the control group (G4), which was injected with sterile saline exhibited no mortality (Fig. 6). Furthermore, successful re-isolation of the pathogen from infected tissues confirmed its pathogenic role in disease progression.

The cumulative mortality curve of L. vannamei: Groups 1–3 (G1-G3) represents shrimp intramuscularly (IM) injected with different virulent strains of V. parahemolyticus (A, B, and C, respectively) at an inoculum of 1 × 10⁶ CFU/mL, while Group 4 (G4) serves as the negative control, receiving an IM injection of sterile saline.

Discussion

Vibrio spp., pose substantial threats to aquatic farming systems, including shrimp cultivation, hindering industry expansion and intensification by causing severe disease outbreaks and economic losses50. They are disseminated in marine environments and constitute a natural component of the microbiota in both wild and farmed shrimp habitats. Typically opportunistic, Vibrio species can transition to virulent pathogens when environmental conditions favor their proliferation, allowing them to evade the host’s immune defenses and trigger disease outbreaks51. Among Vibrio-induced diseases in shrimp, AHPND is the main critical manifestation, triggered by V. parahaemolyticus (VpAHPND) strains concealing the pVA1 plasmid, which encodes the potent PirAB toxins8.

Herein, L. vannamei infected with AHPND showed a well-defined disease progression, initially presenting with an empty gut, cuticular erosion, exoskeletal softening, and deterioration of the tail fins and antennal flagellum. As the infection progressed, the affected shrimp developed diffuse muscle whitening and a severely atrophied, pale to white hepatopancreas, which is consistent with a previous report by Ghent12. Comparable results have previously been documented in L. vannamei in Northwestern Mexico21, adult Penaeus japonicas52, and other penaeid species, including P. japonicus, P. kerathurus, and P. semisulcatus53. The extent of lesions and mortality are strongly correlated with the pathogenicity of the microorganism, the host immunity, and the particular virulence genes expressed by the bacteria, all of which collectively determine the progression and outcome of the infection54.

In terms of phenotypic examination, the isolates presented consistent traits and biochemical profiles, facilitating their classification as V. parahaemolyticus. These results were in strong concordance with earlier studies55,56. The overall prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus among the examined shrimp was 11%. These outcomes are relatively consistent with the reports of Youssef57 and Morshdy58, although they are considerably inferior to the prevalence documented by Coly59 and Parthasarathy60. Epidemics of V. parahaemolyticus have often been observed during abrupt temperature changes and are factually linked to spring and autumn syndromes61. The difference in prevalence was due to to factors such as alterations in shrimp species, sample sizes, collection locations, seasonal fluctuations, water quality, and the methodologies used for identification.

With respect to infection intensity, the hepatopancreas and gut are the primary organs affected by infection, a pattern that is consistent with previous studies on the pathology of V. parahaemolyticus infections in shrimp62,63. From a pathophysiological standpoint, the susceptibility of these tissues to infection may be linked to particular encoded-virulence factors, which enable the onset of septicemia. Gomez-Gil64 verified that V. parahaemolyticus plasmids harbor virulence tools. Moreover, the production of Pir toxins, including PirAvp and PirBvp, was detected in both the culture medium and the infected hepatopancreas of shrimp4,65.

Differentiating Vibrio species via outdated methods is an obstacle because of the lack of an accurate diagnostic tool and the time-consuming nature of the analysis66. TCBS agar, for example, fails to distinguish between V. parahaemolyticus, V. mimicus, and V. vulnificus67. The phenotypic similarities between V. parahaemolyticus and related species, as well as Photobacterium, Chryseomonas, and Shewanella species, complicate accurate identification68. Additionally, the non-selectivity of TCBS agar allows the overgrowth of V. alginolyticus, which can obscure V. parahaemolyticus colonies69. However, sucrose utilization on TCBS agar conferred its ability to differentiate between V. parahaemolyticus (green colonies) and V. alginolyticus (yellow colonies). V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus exhibit the same phenotypic characters, with the latter previously classified as biotype 2 of V. parahaemolyticus, and molecular studies showed a genetic similarity of 60–70% between the two species70. Thus, selecting a suitable molecular assay is critical for accurate identification of Vibrio species. All the recovered isolates were positive for the groEL and AP3 genes. The groEL gene has proven to be a dependable molecular indicator for the detection of V. parahaemolyticus, offering high selectivity and sensitivity29. Furthermore, the AP3 toxin-encoding gene of V. parahaemolyticus is primarily utilized to differentiate AHPND strains, serving as a critical marker for identifying this highly pathogenic bacterium45.

Antibiotic resistance remains a critical issue, potentially exacerbating the severity and persistence of bacterial infections36. In this context, V. parahaemolyticus isolates unveiled varying but notably effective susceptibilities to enrofloxacin, florfenicol, and imipenem, indicating that resistance to these antimicrobials has not yet evolved. These results are in agreement with those of Tan71, who conveyed favorable bactericidal activity of carbapenem derivatives against V. parahaemolyticus isolated from Rastrelliger brachysoma. Han72 stated that USA Vibrio isolates exhibited continued sensitivity to imipenem. Similarly, earlier research has shown that V. parahaemolyticus isolates respond effectively to florfenicol and enrofloxacin4.

Conversely, the recovered V. parahaemolyticus strains displayed significant resistance to β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, with amoxicillin (92%) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (88%) exhibiting the highest resistance rates. Additionally, these strains presented diverse resistance patterns against trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and ceftriaxone. These results align with previous studies reporting comparable resistance trends in V. parahaemolyticus isolates from aquaculture settings73,74. Notably, a previous study by Heenatigala and Fernando75 observed 100% resistance to oxytetracycline and ampicillin, whereas Letchumanan76 and Zheng77 found ampicillin resistance rates of 82% and 82.8%, respectively. The noticed antibiotic resistance could stem from the recurrent usage of antibiotics to manage past disease eruptions. Inopportune antimicrobial usage in aquaculture, together with V. parahaemolyticus’s capability to attain resistance genes from other superbugs, significantly contributes to the increase in of MDR strains78. Widespread antimicrobial resistance is largely driven by the horizontal gene transfer79.

Herein, PCR confirmed the presence of the AP3, toxR, tlh, tdh, and trh genes in variable proportions in the retrieved isolates, which is in agreement with the findings of77,80. Although various genetic markers have been employed for the precise identification of V. parahaemolyticus, they fail to explain its pathogenic potential, since these genes are found in both virulent and non-virulent strains81. However, the AP3 gene of V. parahaemolyticus serves as a key marker for differentiating AHPND-causing strains from non-AHPND variants. Its presence is pivotal for the identification of this highly virulent pathogen, making it an essential tool in the diagnosis and surveillance of AHPND in aquaculture settings82.

In the present study, one isolate did not harbor the tlh virulence gene. Although tlh is considered a prominent species-specific marker gene for V. parahaemolyticus, several studies have reported its absence in certain isolates. A possible explanation for this observation is that these strains may be non-pathogenic, suggesting that the presence of the tlh gene alone might not be a fully reliable indicator for V. parahaemolyticus surveillance83,84. Moreover, the detection of the tdh and trh genes in V. parahaemolyticus is important to for identifying their potential threat to human health58,85. These genes are integral to the infectivity of V. parahaemolyticus, contributing to substantial human illnesses like diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain86. As primary virulence factors, tdh and trh play pivotal roles in inducing RBCs lysis and host cell toxicity24. The results suggested that the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus is not attributed to a sole gene but rather to the synergistic influences of multiple virulence factors, as verified by the 100% mortality rate perceived in the challenge trial.

Likewise, most of the recovered strains demonstrated MDR across various antimicrobials, commonly carrying blaTEM, blaOXA, sul1, aadA, ermB, and tetA or tetB resistance genes. These results in align with those of previous studies87,88,89. The blaTEM and blaOXA genes play fundamental roles in mediating resistance to beta-lactams90,91, whereas sulphonamide, aminoglycosides, macrolide, and tetracycline resistance are predominantly arbitrated by the sul1, aadA, ermB, and tetA or tetB genes, respectively92,93,94. Vibrios have an inherent capacity to secure a diverse range of resistance genes from additional pathogens via genetic elements38. Horizontal gene transfer has been implicated in the acquisition of resistance and virulence genes in this pathogen95,96.

The challenge trial demonstrated substantial mortalities in the inoculated shrimp, confirming the virulence of the inoculated strains. Furthermore, the results confirmed a strong correlation between cumulative mortality and the inherited virulence genes of the inoculated strains. The affected shrimp revealed symptoms classically associated with natural infection, thus reinforcing Koch’s postulates and aligning with findings from prior research29. Cuticle erosion was evident in both field and experimentally challenged cases, suggesting that the chitinoclastic and chitinolytic activities of V. parahaemolyticus were responsible for this condition97. Additionally, whitish musculature, generalized necrosis and mineralization, shell softening, loose shells, red discoloration, exoskeletal necrosis, and reddish pleural borders of the antennae were observed following inoculation. These pathological manifestations align with previous reports of P. vannamei infected with V. parahaemolyticus49,98. Herein, the hepatopancreas of most affected shrimp displayed varying degrees of congestion or atrophy. A pronounced reduction in hematopoiesis, coupled with hepatopancreatic depletion and degeneration, was also observed in V. parahaemolyticus-challenged shrimp99,100. The lesions develop due to the release of extracellular products or toxins following successful colonization of the shell and gill tissues101. The findings here offer critical perceptions into the virulence tools of the pathogen, providing a basis for the development of targeted policies for its control and treatment.

In summary, this work underscored the development of MDR V. parahaemolyticus strains in shrimp. The recovered V. parahaemolyticus strains were multivirulent and usually harbored the Ap3, toxR, tlh, and tdh virulence genes. In addition, the retrieved strains displayed multidrug resistance to three to seven tested antimicrobial classes and commonly carried the ermB, blaTEM, aadA, blaOXA, sul1, tetA, and/or tetB genes. Notably, florfenicol, imipenem, and enrofloxacin showed potent antimicrobial activities against the recovered V. parahaemolyticus strains from shrimp. The integration of conventional and molecular approaches provides a useful strategy for distinguishing V. parahaemolyticus in shrimp. Unfortunately, the development of MDR V. parahaemolyticus in shrimp highlights a momentous public health issue.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture Sustainability in Action (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2020).

de Souza, M. C., Dent, F., Azizah, F., Liu, D. & Wang, W. In the Shrimp Book II 577–594 (CABI GB, 2021).

Chen, S. et al. Growth performance, haematological parameters, antioxidant status and salinity stress tolerance of juvenile Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) fed different levels of dietary myo-inositol. Aquacult. Nutr. 24, 1527–1539 (2018).

Tinh, T. H. et al. Antibacterial spectrum of synthetic herbal-based polyphenols against Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from diseased Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) in Thailand. Aquaculture 533, 736070 (2021).

Gafrd General authority for fish resources development. Fish Statistics Yearbook (2019).

Thornber, K. et al. Evaluating antimicrobial resistance in the global shrimp industry. Reviews Aquaculture 12, 966–986 (2020).

Han, J. E. et al. Genomic and histopathological characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from an acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease outbreak in Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) cultured in Korea. Aquaculture 524, 735284 (2020).

Tang, K. F. et al. Shrimp acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease strategy manual. (2020).

Peña-Navarro, N., Castro-Vásquez, R., Vargas-Leitón, B. & Dolz, G. Molecular detection of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in Penaeus vannamei shrimps in Costa Rica. Aquaculture 523, 735190 (2020).

Flegel, T. W. Historic emergence, impact and current status of shrimp pathogens in Asia. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 110, 166–173 (2012).

Eshik, M. M. E., Abedin, M. M., Punom, N. J., Begum, M. K. & Rahman, M. S. Molecular identification of AHPND positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus causing an outbreak in south-west shrimp farming regions of Bangladesh. J. Bangladesh Acad. Sci. 41, 127–135 (2017).

Ghent, B. Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in Shrimp: Virulence. Pathogenesis and Mitigation Strategies.[Europe PMC free article][Abstract][Google Scholar] (2020).

Dhar, A. K. et al. First report of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) occurring in the USA. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 132, 241–247 (2019).

Fadel, A. et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in cultured white-leg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei with the fungal bioactive control strategy. Microb. Pathog. 203, 107450 (2025).

El Zlitne, R. A. et al. Vibriosis triggered mass kills in Pacific white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) reared at some Egyptian earthen pond-based aquaculture facilities. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biology Fisheries 26, 261–277 (2022).

Okoh, A. I. et al. Prevalence and characterisation of non-cholerae vibrio spp. In final effluents of wastewater treatment facilities In two districts of the Eastern cape Province of South africa: implications for public health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 2008–2017 (2015).

Feldhusen, F. The role of seafood in bacterialfoodborne diseases. Microbes Infect. 2, 1651–1660 (2000).

Álvarez-Contreras, A. K., Quiñones-Ramírez, E. I., Vázquez-Salinas, C. & Prevalence Detection of virulence genes and antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogen vibrio species isolated from different types of seafood samples at La Nueva Viga market in Mexico City. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 114, 1417–1429 (2021).

Ghenem, L., Elhadi, N., Alzahrani, F. & Nishibuchi, M. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a review on distribution, pathogenesis, virulence determinants and epidemiology. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 5, 93–103 (2017).

Tran, L. et al. Determination of the infectious nature of the agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome affecting Penaeid shrimp. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 105, 45–55 (2013).

Soto-Rodriguez, S. A., Gomez-Gil, B., Lozano-Olvera, R., Betancourt-Lozano, M. & Morales-Covarrubias, M. S. Field and experimental evidence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as the causative agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease of cultured shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Northwestern Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 1689–1699 (2015).

Yang, Y. T. et al. Draft genome sequences of four strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, three of which cause early mortality syndrome/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in shrimp in China and Thailand. Genome Announcements. 2, 101128genomea00816–101128genomea00814 (2014).

Han, J. E., Tang, K. F., Tran, L. H. & Lightner, D. V. Photorhabdus insect-related (Pir) toxin-like genes in a plasmid of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, the causative agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) of shrimp. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 113, 33–40 (2015).

Makino, K. et al. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet 361, 743–749 (2003).

Honda, T. & Iida, T. The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct haemolysin and related hemolysins. Reviews Res. Med. Microbiol. 4, 106–113 (1993).

Mabrok, M. et al. Development of a species-specific polymerase chain reaction for highly sensitive detection of Flavobacterium columnare targeting chondroitin AC lyase gene. Aquaculture 521, 734597 (2020).

Hossain, M., Kim, E. Y., Kim, Y. R., Kim, D. G. & Kong, I. S. Application of groEL gene for the species-specific detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by PCR. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 54, 67–72 (2012).

Okocha, R. C., Olatoye, I. O. & Adedeji, O. B. Food safety impacts of antimicrobial use and their residues in aquaculture. Public Health Rev. 39, 1–22 (2018).

Algammal, A. M. et al. The prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance genes of multidrug-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus recovered from Oreochromis niloticus. Aquacult. Int. 32, 9499–9517 (2024).

Eid, H. I., Algammal, A. M., Nasef, S. A., Elfeil, W. K. & Mansour, G. H. Genetic variation among avian pathogenic E. coli strains isolated from broiler chickens. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 11, 350–356 (2016).

Eid, H. M. et al. Prevalence, molecular typing, and antimicrobial resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from ducks. Veterinary World. 12, 677 (2019).

Elmahdi, S., DaSilva, L. V. & Parveen, S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: a review. Food Microbiol. 57, 128–134 (2016).

Venggadasamy, V. et al. Incidence, antibiotic susceptibility and characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from seafood in Selangor, Malaysia. Progress Microbes Mol. Biology 4, 1–34 (2021).

Obaidat, M. M., Salman, A. E. B. & Roess, A. A. Virulence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from seafood from three developing countries and of worldwide environmental, seafood, and clinical isolates from 2000 to 2017. J. Food. Prot. 80, 2060–2067 (2017).

Algammal, A. M. et al. The evolving multidrug-resistant V. alginolyticus in sea bream commonly harbored collagenase, trh, and tlh virulence genes and Sul1, blaTEM, aadA, tetA, blaOXA,and tetB or tetM resistance genes. Aquacult. Int. 33, 134 (2025).

Algammal, A. M. et al. Newly emerging MDR B. cereus in Mugil seheli as the first report commonly harbor nhe, hbl, cytK, and pc-Plc virulence genes and bla1, bla2, tetA, and ermA resistance genes. Infect. Drug Resist., 2022 2167–2185 (2022).

Algammal A. M. et al. Molecular and HPLC-based approaches for detection of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A released from toxigenic Aspergillus species in processed meat. BMC Microbiol. 21 (1), 82 (2021).

Dutta, D., Kaushik, A., Kumar, D. & Bag, S. Foodborne pathogenic vibrios: antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 12, 638331 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Antibiotic resistance and genetic profiles of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from farmed Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in Ningde regions. Microorganisms 12, 152 (2024).

Letchumanan, V., Ab Mutalib, N. S., Wong, S. H., Chan, K. G. & Lee, L. H. Determination of antibiotic resistance patterns of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from shrimp and shellfish in Selangor, Malaysia. Progress Microbes Mol. Biology 2, 1–9 (2019).

Austin, B. & Austin, D. A. Bacterial Fish Pathogens: Disease of Farmed and Wild Fish (Springer, 2016).

Colakoglu, F. A., Sarmasik, A. & Koseoglu, B. Occurrence of Vibrio spp. And Aeromonas spp. In shellfish harvested off Dardanelles cost of Turkey. Food Control. 17, 648–652 (2006).

Siddique, A. B. et al. Characterization of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from fish aquaculture of the Southwest coastal area of Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 12, 635539 (2021).

Kaysner, C. A., DePaola, A. & Jones, J. B. A. M. Chap. 9: Vibrio. Bacteriological Analytical Manual; USA, Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA 8 (2004).

Sirikharin, R. et al. A new and improved PCR method for detection of AHPND bacteria. Netw. Aquaculture Centres Asia-Pacific (NACA). 7 (9), 1–3 (2014).

CLSI Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria isolated from aquatic animals. Brian V. Lubbers (eds). In CLSI Guideline VET04 3rd edn (Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281 (2012).

Krumperman, P. H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46, 165–170 (1983).

Raja, R. A. et al. Pathogenicity profile of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in farmed Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 67, 368–381 (2017).

Ghosh, A. K., Hasanuzzaman, A. F. M., Sarower, M. G., Islam, M. R. & Huq, K. A. Unveiling the biofloc culture potential: Harnessing immune functions for resilience of shrimp and resistance against AHPND-causing Vibrio parahaemolyticus Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunology, 151, 109710 (2024).

Tang, K. & Bondad-Reantaso, M. Impacts of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease on commercial shrimp aquaculture. Rev. Sci. Tech. 38, 477–490 (2019).

Khafagy, A., El Gamal, R., Awad, S., Tealeb, A. & Shalaby, M. Bacteriological and histopathological studies on adult shrimps (Penaeus japonicas) infected with Vibrio species in Suez Canal area. Suez Canal Veterinary Med. J. SCVMJ. 22, 157–178 (2017).

El-Bouhy, Z., Abdelrazek, F. & Hassanin, M. A contribution on vibriosis in shrimp culture in Egypt. Egypt J. Aquat. Res. 32, 443–456 (2006).

Zamora-Pantoja, D. R., Quiñones-Ramírez, E. I., Fernández, F. J. & Vazquez-Salinas, C. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Reviews Res. Med. Microbiol. 24, 41–47 (2013).

Bisha, B., Simonson, J., Janes, M., Bauman, K. & Goodridge, L. D. A review of the current status of cultural and rapid detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 47, 885–899 (2012).

Jones, J. L. et al. Biochemical, serological, and virulence characterization of clinical and oyster Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 2343–2352 (2012).

Youssef, A., Farag, A. & Helal, I. Molecular characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from shellfish and their harvesting water from Suez Canal area, Egypt. Int. Food Res. J. 25, 2375–2381 (2018).

Morshdy, A. E. M., Abdelhameed, N. S., Abdallah, K., El-Tahlawy, A. S. & El Bayomi, R. M. Antibiotic resistance profile and molecular characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae isolated from fish. J. Adv. Veterinary Res. 13, 443–448 (2023).

Coly, I., Gassama Sow, A., Seydi, M. & Martinez-Urtaza, J. Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio parahaemolyticus detected in seafood products from Senegal. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 1050–1058 (2013).

Parthasarathy, S., Das, S. C. & Kumar, A. Occurrence of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in crustacean shellfishes in coastal parts of Eastern India. Veterinary World. 9, 330 (2016).

Hsiao, H. I., Jan, M. S. & Chi, H. J. Impacts of Climatic variability on Vibrio parahaemolyticus outbreaks in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 13, 188 (2016).

Kongrueng, J. et al. Characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus causing acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in Southern Thailand. J. Fish Dis. 38, 957–966 (2015).

Chai, F. P. et al. Risk of acquiring Vibrio parahaemolyticus in water and shrimp from an aquaculture farm. 黒潮圏科学= Kuroshio Sci. 8, 59–62 (2014).

Gomez-Gil, B., Soto-Rodríguez, S., Lozano, R. & Betancourt-Lozano, M. Draft genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strain M0605, which causes severe mortalities of shrimps in Mexico. Genome Announcements. 2, 101128genomea00055–101128genomea00014 (2014).

Lin, S. J., Hsu, K. C. & Wang, H. C. Structural insights into the cytotoxic mechanism of Vibrio parahaemolyticus PirA Vp and PirB Vp toxins. Mar. Drugs. 15, 373 (2017).

Fu, K. et al. An innovative method for rapid identification and detection of Vibrio alginolyticus in different infection models. Front. Microbiol. 7, 651 (2016).

Su, Y. C. & Liu, C. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a concern of seafood safety. Food Microbiol. 24, 549–558 (2007).

Kanjanasopa, D., Pimpa, B. & Chowpongpang, S. Occurrence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in cockle (Anadara granosa) harvested from the South Coast of Thailand. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 33, 295–300 (2011).

Martinez-Urtaza, J. et al. Emergence of Asiatic vibrio diseases in South America in phase with El Niño. Epidemiology 19, 829–837 (2008).

Robert-Pillot, A., Guenole, A. & Fournier, J. M. Usefulness of R72H PCR assay for differentiation between Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus species: validation by DNA–DNA hybridization. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215, 1–6 (2002).

Tan, C. W. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from short mackerels (Rastrelliger brachysoma) in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1087 (2017).

Han, J. E., Mohney, L. L., Tang, K. F., Pantoja, C. R. & Lightner, D. V. Plasmid mediated Tetracycline resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus associated with acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in shrimps. Aquaculture Rep. 2, 17–21 (2015).

Abdellrazeq, G. S. & Khaliel, S. A. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of vibrios isolated from healthy and diseased aquacultured freshwater fishes. Global Vet. 13, 397–407 (2014).

Su, C. & Chen, L. Virulence, resistance, and genetic diversity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus recovered from commonly consumed aquatic products in Shanghai, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 160, 111554 (2020).

Heenatigala, P. & Fernando, M. Occurrence of bacteria species responsible for vibriosis in shrimp pond culture systems in Sri Lanka and assessment of the suitable control measures. Sri Lanka J. Aquat. Sci. 21, 1–17 (2016).

Letchumanan, V., Yin, W. F., Lee, L. H. & Chan, K. G. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shrimps in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 6, 33 (2015).

Zheng, Z. et al. Genetic characterization of blaCTX–M–55-bearing plasmids harbored by food-borne cephalosporin-resistant vibrio parahaemolyticus strains in China. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1338 (2019).

Jin, J. et al. Characteristics of antimicrobial-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains and identification of related antimicrobial resistance gene mutations. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 18, 873–879 (2021).

Che, Y. et al. Conjugative plasmids interact with insertion sequences to shape the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2008731118 (2021).

Zaher, H. A. et al. Prevalence and antibiogram of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Aeromonas hydrophila in the flesh of nile tilapia, with special reference to their virulence genes detected using multiplex PCR technique. Antibiotics 10, 654 (2021).

Hossain, M. T., Kim, Y. O. & Kong, I. S. Multiplex PCR for the detection and differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains using the groEL, tdh and trh genes. Mol. Cell Probes. 27, 171–175 (2013).

Powers, Q. M. Acute Hepatopancreactic Necrosis Disease (AHPND): Crayfish Susceptibility and Detection of Etiologic Agent in Environmental Samples (The University of Arizona, 2020).

Gutierrez West, C. K., Klein, S. L. & Lovell, C. R. High frequency of virulence factor genes tdh, trh, and tlh in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from a pristine estuary. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2247–2252 (2013).

Raja, R. A. et al. Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from farmed Penaeid shrimp, Penaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931) by multiplex PCR targeting toxR and tlh genes. Indian J. Fisheries 70, 162–167 (2023).

Rizvi, A. V. & Bej, A. K. Multiplexed real-time PCR amplification of tlh, tdh and trh genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its rapid detection in shellfish and Gulf of Mexico water. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 98, 279–290 (2010).

Shimohata, T. & Takahashi, A. Diarrhea induced by infection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Med. Invest. 57, 179–182 (2010).

Mumbo, M. T. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of bacterial foodborne pathogens in nile tilapia fish (Oreochromis niloticus) at points of retail sale in Nairobi, Kenya. Front. Antibiot. 2, 1156258 (2023).

Dewi, R. R. et al. On-farm practices associated with multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli and Vibrio parahaemolyticus derived from cultured fish. Microorganisms 10, 1520 (2022).

Kang, C. H. et al. Characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from oysters in korea: resistance to various antibiotics and prevalence of virulence genes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 118, 261–266 (2017).

Adesiyan, I. M., Bisi-Johnson, M. A. & Okoh, A. I. Incidence of antibiotic resistance genotypes of vibrio species recovered from selected freshwaters in Southwest Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 12, 18912 (2022).

Silvester, R. et al. Occurrence of β-lactam resistance genes and plasmid-mediated resistance among vibrios isolated from Southwest Coast of India. Microb. Drug Resist. 25, 1306–1315 (2019).

Jeamsripong, S., Khant, W. & Chuanchuen, R. Distribution of phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from cultivated oysters and estuarine water. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 96, fiaa081 (2020).

Igbinosa, E. O., Beshiru, A., Igbinosa, I. H., Ogofure, A. G. & Uwhuba, K. E. Prevalence and characterization of food-borne Vibrio parahaemolyticus from African salad in Southern Nigeria. Front. Microbiol. 12, 632266 (2021).

Beshiru, A. & Igbinosa, E. O. Surveillance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogens recovered from ready-to-eat foods. Sci. Rep. 13, 4186 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: serotype conversion and virulence. BMC Genom. 12, 1–13 (2011).

Ceccarelli, D., Salvia, A. M., Sami, J., Cappuccinelli, P. & Colombo, M. M. New cluster of plasmid-located class 1 integrons in Vibrio cholerae O1 and a dfrA15 cassette-containing integron in Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated in Angola. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2493–2499 (2006).

Molina, V. Vibrio parahaemolyticus Interactions with Chitin in Response To Environmental Factors (Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, 2014).

Intriago, P. et al. Bacterial muscle necrosis in cultured Penaeus vannamei in latin America. Aquaculture Research. 9919229 (2024). (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Taurine metabolism is modulated in Vibrio-infected Penaeus vannamei to shape shrimp antibacterial response and survival. Microbiome 10, 213 (2022).

Abraham, T. et al. Epizootology and pathology of bacterial infections in cultured shrimp Penaeus monodon Fabricius 1798 in West Bengal, India. Indian J. Fish. 60, 167–171 (2013).

Sudheesh, P. & Xu, H. S. Pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in tiger Prawn Penaeus monodon fabricius: possible role of extracellular proteases. Aquaculture 196, 37–46 (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and study design: A.M.A. and M.M.; Methodology: A.M.A., M.M., F.M.Y., S.S.A., and G.B.D.; Acquisition of data, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and Investigation: A.M.A., M.M., B.K.A., S.A., A.K., A.S.S., M.Y.A, E.Al-O., G.B.D., F.M.Y., and S.S.A.; Drafting the manuscript: A.M.A., M.M., B.K.A., S.A., A.S.S., A.K., and E.Al-O.; Writing, critically reviewing, and editing: A.M.A. and M.M. All authors have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Algammal, A.M., Alghamdi, S., Almessiry, B.K. et al. In-depth characterization of virulence traits, pathogenicity, antibiogram, and antibiotic resistance genes of MDR Vibrio parahaemolyticus retrieved from shrimp. Sci Rep 15, 34285 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20333-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20333-x