Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is characterized by progressive muscle fiber degeneration and replacement by fibrous and adipose tissues, alongside significant vascular abnormalities. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) histological assessments provide limited insight into the complex three-dimensional (3D) spatial organization and structural disorganization within dystrophic muscle. Here, we present a novel 3D approach combining multiphoton microscopy (second harmonic generation [SHG] and two-photon excited fluorescence [TPEF]) with tissue-clearing methods to comprehensively characterize microvascular and connective tissue remodeling in dystrophic skeletal muscle. We established a dedicated 3D image analysis workflow utilizing deep-learning-based segmentation techniques to quantify key parameters in both vascular and fibrotic compartments in healthy and dystrophic rat muscle samples. Our findings reveal a profound spatial reorganization of the vascular network in dystrophic muscle, marked by its embedding within an expanded connective tissue and a significant reduction in physical interactions with muscle fibers. This advanced imaging and analysis pipeline provides detailed insights into the extent of vascular and fibrotic remodeling in dystrophic muscle, and represents a powerful tool for monitoring disease progression and evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe X-linked recessive disorder caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene1leading to a complete lack of the dystrophin protein2,3. This deficiency destabilizes the plasma membrane, triggering repeated cycles of muscle fiber necrosis and degeneration, followed by their replacement with adipose and fibrotic tissue4. DMD patients exhibit muscle atrophy and progressive muscle weakness, resulting in loss of ambulation, and develop cardiomyopathy and respiratory insufficiency ultimately leading to premature death typically between 20 and 30 years of age5,6.

Fibrosis, corresponding to the excessive deposition of fibrillar collagen types I and III from extracellular matrix7further impairs contractile muscle function and significantly contributes to disease progression4,8. In addition to muscle fiber degeneration, vascular abnormalities including impaired blood flow and reduced capillary density have been documented9,10,11. Interstitial fibrosis exacerbates vascular dysfunction by disrupting the structural integrity of the vascular network, leading to impaired nutrient and oxygen exchange with muscle fibers4,10.

Fibrosis and vascular remodeling are typically assessed using conventional two-dimensional (2D) histological methods4,12,13. These methods provide limited insight into the complex 3D spatial relationships among muscle fibers, extracellular matrix, and vasculature. Nonlinear microscopy techniques, such as second harmonic generation (SHG) for label-free visualization of collagen-rich fibrotic structures14 and two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) for high-resolution imaging of fluorescently labeled vasculature15 can help address these limitations, enabling 3D imaging of thick tissues with intrinsic optical sectioning and reduced photobleaching14,16,17. However, even these advanced techniques are limited by light scattering in biological tissues18,19which restricts imaging depth to ~ 150 μm in uncleared muscle20,21.

Tissue clearing methods can overcome this limitation by reducing light scattering through refractive index matching22,23rendering tissues optically transparent and significantly extending imaging depth15,24. When combined with multiphoton microscopy, tissue clearing enables high-resolution imaging at depths of up to 1 mm in organs such as the heart and brain15,24. However, in skeletal muscle, particularly in pathological conditions, imaging depth typically remains limited to approximately 350 μm due to higher scattering and tissue density21. Despite these advancements, few studies have systematically combined tissue clearing and multiphoton imaging to quantify and analyze the fibrotic-vascular interactions in dystrophic muscle.

In the present study, we developed a methodological pipeline that combines optical tissue clearing (iDISCO + 24 and CUBIC25 protocols) with multiphoton microscopy to investigate the 3D remodeling of vasculature, stained with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (LEL), and connective tissue. Moreover, we implemented a deep learning-based image analysis workflow for the segmentation and quantification of vascular networks and muscle fibers. This approach was applied to skeletal muscles from 1-year-old healthy and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats to characterize morphological alterations in 3D and assess how fibrosis may contribute to impaired vascular organization.

Our results demonstrate that the combination of tissue clearing and multiphoton imaging provides a robust strategy to visualize and quantify 3D structural changes in dystrophic muscle. This method constitutes a novel tool for studying disease progression and evaluating therapeutic interventions targeting both vascular and fibrotic remodeling in neuromuscular disorders.

Results

Microvessels are small blood vessels located at the periphery of myofibers, including capillaries, terminal arterioles, and terminal venules26,27.

Standard 2D histological analysis of dystrophic muscle reveals capillarization defects as a key feature of microvascular damage.

We first assessed vascular impairment in dystrophic muscle using a 2D approach. To this end, we analyzed two global parameters (microvessel-to-fiber ratio and microvessel density) and two specific metrics (microvessel contact and sharing factor), that are commonly employed to evaluate vasculature in skeletal muscle28,29,30. These analyses were conducted on Biceps femoris muscle sections from 1-year-old WT and DMDmdx rats.

TPEF observation of transverse sections stained with LEL DyLight 594 revealed the distribution of microvessels within muscle fiber bundles, which were visualized by green autofluorescence (Fig. 1a, left panel). A binary mask was applied to the entire section to delineate the muscle fiber area (Fig. 1a, middle panel), enabling the isolation of endomysial vessels. These vessels were then automatically detected using the Segment.ai module in NIS-Elements software (Fig. 1a, right panel). This method revealed a microvessel-to-fiber ratio of 1.05 ± 0.08 in DMDmdx rats and 1.5 ± 0.09 in WT rats (Fig. 1b, top). Although the ratio was numerically higher in WT rats, there was no significant difference between groups. Additionally, microvessel density, defined as the number of microvessels within the endomysial area, was measured as 268 ± 17 mm⁻² in DMDmdx rats and 243 ± 22 mm⁻² in WT rats (Fig. 1b, bottom), indicating comparable microvessel densities between the two groups.

To investigate the interactions between microvessels and individual muscle fibers, we automated the measurements of microvessel contact and the sharing factor using the GA3 module in NIS-Elements software. Muscle fibers and microvessels were detected on 2D cross-sections using deep learning models, namely SegmentObject.ai and Segment.ai, respectively (Fig. 2a, left panel). Details of the training methodology are provided in the Materials and Methods section. To capture the spatial relationship more effectively, the binary mask representing microvessels was expanded to define a proximity area around each muscle fiber. A binary operation was then performed between the muscle fiber and microvessel masks to identify regions of proximity (Fig. 2a, right panel). These regions were used to uniquely associate each proximity region with a corresponding fiber and vessel, enabling precise quantification of microvessel-to-fiber interactions. While DMDmdx rat muscle exhibited a numerical decrease in microvessel contacts per fiber compared to WT rats (3.2 ± 0.24 vs. 3.7 ± 0.17, respectively; Fig. 2b, top), this difference was not statistically significant. Conversely, DMDmdx muscle was characterized by a significant increase in the sharing factor, which represents the number of fibers served by a single microvessel: 2.6 ± 0.07 (DMDmdx rats) vs. 2.4 ± 0.03 (WT rats) (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2b, bottom). Collectively, these findings indicate altered microvasculature organization in 1-year-old DMDmdx rats.

Multimodal 3D imaging reveals a newly formed vascular network and reduced muscle fiber-vessel interaction in dystrophic muscle.

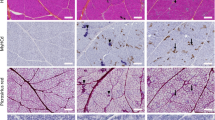

To assess whether 3D imaging analysis could offer a more precise and comprehensive assessment of vascularization, focusing on vascular network connectivity and geometry, we utilized the same muscle samples as in previous experiments, but in thick section format. We optimized the clearing protocol for thick skeletal muscle, settling on a combination of the iDISCO + and CUBIC methods, as described previously31. We then validated that the staining with LEL DyLight 594 was compatible with this protocol. Following optimization, Z-stack images were generated from cleared and LEL DyLight 594-stained Sect. (1-mm-thick). Green muscle autofluorescence and red fluorescence of stained vessels were acquired with multiphotonic microscope up to a depth of 350 μm (Fig. 3a, first column). This enabled identification of muscle fiber bundles and the microvessel network in depth. We generated images with a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which facilitated segmentation of the vasculature across the entire field of view (FOV, 1.052 × 1.052 × 0.350 mm). Muscle fibers and microvessels segmented based on endogenous green fluorescence (Fig. 3a, second column) and red fluorescence (Fig. 3a, third column) staining, respectively, were color-coded to enhance their visibility. Vascular surfaces embedded within muscle fibers were detected by applying an “AND” logical function between the binary masks of muscle fibers and vasculature (Fig. 3a; fourth column). We observed that the endomysial vascular network penetrating muscle consisted of branched capillaries that were well organized in WT rat muscle compared to the disorganized network in DMDmdx rat muscle. Specifically, the vascular network was oriented parallel to the muscle fibers in WT rat muscle, but ran in multiple directions in DMDmdx rat muscle.

For 3D quantitative analysis, we developed a pipeline within the GA3 module in NIS-Elements software, exploiting the same deep learning models used for the 2D analysis to detect objects. These models were applied to individual image slices, and the data were reconstructed into 3D volumetric representations. 3D microvessel density, expressed as the volume occupied by vessels relative to fiber volume, was higher in DMDmdx (0.02 ± 0.002) versus WT rat muscle (0.014 ± 0.001) (Fig. 3b, left), although this difference was not statistically significant. However, the branching count per muscle fiber volume was significantly higher in DMDmdx (21,596 ± 1,981) versus WT (13,428 ± 2,094) rats, indicating increased vascular network ramification in the dystrophic context (p = 0.017; Fig. 3b, middle). To facilitate efficient nutrient and oxygen exchange, capillaries form close contacts with muscle fibers by wrapping within grooves32. We assessed the embedding surface of the vasculature within muscle fibers, using muscle fiber and microvessel masks to calculate the shared surface area, which was then normalized to the number of fibers. Our analysis revealed a significant decrease in the contact surface area in DMDmdx (8.1 ± 0.6 μm²) versus WT (20.4 ± 3.1 μm²) rats, indicating impaired vasculature-muscle interactions in dystrophic muscle (p < 0.001; Fig. 3b, right).

Additional morphometric analyses were conducted to assess the morphology of the vascular network. Vessel diameter and length were quantified using the filament algorithm in Imaris software (version 10.1, Oxford Instruments) (Fig. 4a). The algorithm’s ‘loops’ function was trained on data from four distinct regions before being applied to analyze three images (1.052 × 1.052 × 0.350 μm) of both WT and DMDmdx rat muscle. From each image, 150 microvessels were selected for analysis. The microvessel diameter was reduced in DMDmdx (5.6 ± 0.1 μm) versus WT (5.9 ± 0.1 μm) rats (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b, top). Microvessel length was significantly shorter in the DMDmdx (37.44 ± 1.3 μm) versus WT (54.218 ± 3 μm) muscle (p < 0.0001; Fig. 4b, bottom). Together, these results indicate a highly reorganized vasculature in dystrophic rat muscle, characterized by microvessels that are more branched, shorter, wider, and exhibit reduced contact with muscle fibers. These findings underscore the utility of 3D multimodal exploration for analyzing spatially networked structures such as vasculature.

Multimodal 3D imaging enables combined assessment of microvascular and fibrotic remodeling in dystrophic muscle

Fibrosis represents one of the main pathological features of dystrophic muscle4,33,34 and contributes to structural alterations in muscle bundle organization, including altered spatial relationships whereby the vascular network is detached from muscle fibers12. Recent evidence suggested that the disorganization of collagen network constitutes a potential biomarker of DMD8,24. Building on our microvasculature findings, we next sought to characterize the endomysial connective tissue in 3D and examine its interaction with the vascular network, allowing for a more comprehensive view of muscle remodeling at the structural level.

We analyzed forward 3D SHG on cleared muscle cross-sections. All images were acquired with consistent laser power, detector sensitivity, and gain settings. Image analysis of SHG collagen fibers was performed using the GA3 module of NIS-Elements Software, and false-coloring was applied to the binary mask. A substantial increase in collagen deposition was observed in DMDmdx versus WT rats (Fig. 5a). Endomysial SHG density, corresponding to the volume of collagen network surrounding each muscle fiber relative to muscle fiber volume, was significantly higher in DMDmdx (2.79% ± 0.10%) versus WT (0.51% ± 0.11%) muscle (p < 0.0001; Fig. 5b, left, top).

A detailed analysis of the collagen network was conducted by evaluating the morphology and spatial distribution of SHG+ collagen objects. DMDmdx rats exhibited overrepresentation across all volume classes, indicating increased collagen accumulation along the muscle fiber in depth (Fig. 5b, top right). SHG+ collagen objects were more frequently distributed in shorter distance classes in DMDmdx rats versus WT, suggesting a denser collagen network (Fig. 5b, bottom left). Moreover, these collagen objects were significantly less elongated in DMDmdx versus WT rat muscle (p < 0.001; Fig. 5b, bottom right). Next, we identified 3D regions where DyLight594-stained microvessels spatially coincided with the SHG collagen network, using the previously generated binary masks of both structures (Fig. 6a). The volume of these overlapping regions was measured and normalized to the total microvessel volume to provide a quantitative assessment of the interaction between microvasculature and connective tissue (Fig. 6b, right). The volume of spatial overlap between microvessels and SHG collagen was 10.07 ± 1.66% in DMDmdx rats and 1.79 ± 0.43% in WT rats (p < 0.001; Fig. 6b), indicating a significantly greater degree of microvessel embedding within the fibrotic network in dystrophic muscle. Overall, these data provide new information on the accumulation of connective tissue in dystrophic muscle, in terms of volume, concentration and shape, within which part of the microvasculature is embedded.

Discussion

In this study, we present compelling findings that underscore the utility of multimodal 3D imaging in elucidating the spatial organization and interactions between vasculature, muscle fibers, and connective tissue. Simultaneous 3D visualization of myofibers, microvessels, and/or connective tissue, followed by quantitative analysis on segmented objects, constitutes a powerful approach for comprehensively characterizing the extent of remodeling in dystrophic muscle.

Microvascular disruption is a pathological feature of muscular dystrophy10,35,36 that adversely affects oxygen and nutrient delivery to muscle fibers and impedes muscle development27. As with fibrosis, vascular changes in dystrophic muscle are typically evaluated using conventional 2D histological analyses, which inherently offer limited spatial context37. In this study, we introduced a novel 3D approach to analyze the structure of the vasculature and collagen network, thereby providing further insight into their spatial organization within muscle bundles. To this end, we employed a multimodal imaging technique combining TPEF and SHG to investigate fluorescent lectin-stained vasculature and label-free SHG collagen on cleared rat dystrophic muscle, respectively. In contrast to previous studies that relied on conventional histological methods to assess vascular and fibrotic remodeling4,34our dual-modality imaging approach enabled simultaneous visualization of TPEF and SHG signals from both structures and analysis of their interactions within muscle fibers. Combined with iDISCO + and CUBIC clearing methods, this approach facilitated analysis of microvessel organization and collagen network connectivity to a depth of at least 1 mm (Supplementary Figure S1). We previously demonstrated the utility of tissue clearing and SHG imaging to study fibrosis in DMDmdx rat heart using the CUBIC protocol24. Here, we combine CUBIC with iDISCO + to first enhance the penetration of the fluorescent probes for the vessels thanks to the organic solvent pretreatment in iDISCO + protocol and second to improve the tissue clearing and to avoid the tissue shrinkage thanks to hyperhydration pretreatment in CUBIC protocol. The combination of iDISCO + and CUBIC tissue clearing methods has previously been described for in toto imaging of whole ovarian follicles and their extrinsic vascular and neuronal networks31.

In addition to this novel 3D imaging approach, we developed an image analysis protocol specifically designed to handle the inherent complexity of the objects being measured. Deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool alongside traditional hand-crafted analysis workflows, offering the potential for more accurate and efficient results38. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning U-net architecture to segment blood vessels in heart tissue sections, yielding accurate vascular morphometrics such as vessel length and density38. In our study, 3D features of the vasculature and collagen network were extracted using a U-Net model. We were able to measure vessel density, branching and sharing as well as to characterize the collagen network in terms of density packing and thickness/elongation, thereby corroborating the applicability of these tools as demonstrated by Lapierre-Landry and co-authors38.

Recent studies have identified major structural and functional vascular network defects in a widely used model of DMD, the mdx mouse10,13. Alterations in flow capacity, vessel diameter, and vessel density increase in severity with age10,38. These findings emphasize the crucial role of vascular network damage in the pathophysiology of DMD. In the present study, we describe significant disruptions of the vascular network in the DMDmdx rat model of DMD39. 2D analysis revealed an increased sharing factor in DMDmdx versus WT rats, consistent with previous findings in mdx mice10. 3D analysis of the vasculature confirmed the presence of marked morphological alterations in dystrophic rat muscle, including increases in microvessel ramification, which may represent a compensatory response to the altered metabolic demands of dystrophic muscle10,35. In parallel, we observed decreased vessel-muscle fiber contact, which may indicate impaired functional interactions between the vascular network and muscle fibers. Similar vascular alterations were reported by Latroche et al. in 1-year-old mdx mice, in which the authors described significant increase in branching and functional impairments10.

In analyzing fibrosis, 3D SHG imaging revealed significant changes in the morphology and distribution of the collagen network that were not detectable by 2D image analysis. Specifically, dystrophic rat muscle was characterized by thicker and more densely packed connective tissue. The architecture of collagen fibers has been linked with increased passive stiffness in fibrotic skeletal muscles in mdx mice4,8. Furthermore, there is a correlation between the amount of fibrotic tissue in mdx mouse muscle and contractile function. Given the more pronounced tissue phenotype in the DMDmdx rat model than the mdx mouse39as well as the variability depending on the type of muscle considered, determining whether this correlation is also observed in DMDmdx rats could help to better understand the contractile muscle properties.

3D SHG imaging revealed that the collagen network frequently encased vascular structures in dystrophic muscle, a phenomenon reported in DMD patients4. This encasing likely reflects a pathological interaction between fibrosis and vasculature. Excessive collagen deposition may restrict blood flow, contributing to the increased distance between capillaries and muscle fibers. These findings suggest a pathological feedback loop, whereby fibrosis exacerbates vascular pathology, which in turn drives further muscle degeneration.

The combined analysis of fibrosis and vascular alterations using SHG and TPEF imaging underscores the complex interplay between these two processes in DMD. Our findings suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting both the extension of the vascular network and fibrosis reduction could be effective in managing DMD. Enhancing vascular integrity could improve tissue perfusion and mitigate muscle damage, potentially alleviating some symptoms of the disease40,41. Concurrently, reducing fibrosis could restore the structural and functional integrity of the muscle41. Future studies should investigate the temporal dynamics of vascular and fibrotic remodeling in DMD to identify critical windows for intervention. Early therapeutic strategies targeting these processes could help slow or halt disease progression. Moreover, advanced imaging approaches such as those used in this study could be employed to evaluate the efficacy of potential therapies in preclinical and clinical settings.

Conclusion

The combination of multimodal 3D SHG/TPEF imaging with iDISCO + and CUBIC tissue clearing and deep learning-based image analysis provided new tools to get valuable insights into the structural and spatial features of microvessels and the collagen network in DMD. This approach is particularly well-suited to in-depth characterization of the extent of deterioration in the vasculature and collagen network. Using this approach, we demonstrated that dystrophic muscle features a spatially complex vascular network comprising small microvessels whose interactions with muscle fibers are limited by an encasing connective tissue. The quantitative 3D imaging technique described here could further our understanding of the natural progression of this disease, and serve as a useful tool to assess the impact of biotherapies on vascularization and fibrosis in preclinical studies on DMD.

Methods

Ethics statement and animal experiment

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of the Pays de la Loire Region, France. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the French National Research Council guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Permit number: APAFIS #39967-2022122112121987 v10). Wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the transgenic rat immunophenomic platform (TRIP; Nantes, France). Three animals of each genotype, all aged 1 year, were included in this study. Animals were maintained in a controlled environment (temperature 21 ± 1 °C, 12-h light-dark cycle) at the Boisbonne Center for gene and cell therapy (Oniris, Nantes, France; agreement number: J44273). All efforts were made to minimize suffering. Rats were provided with environmental enrichment: provision of rolls is reported to potentially modify the behavior of housed animals and reduce chronic pain.

Tissue harvesting and sample collection

Anesthesia was induced with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg, Imalgene, Merial, Lyon, France) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, Rompun, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), after which the rats were euthanized by direct administration of sodium pentobarbital (Dolethal; Vetoquinol SA, Magny Vernois) into the vena cava previously accessed by laparotomy, at a lethal dose of 30–35 mg/kg. The Biceps femoris muscles were collected and separated into two portions: one was transferred to a tube containing 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation overnight at 4 °C and storage. The second was embedded in paraffin for classical histological analysis.

iDISCO + clearing pretreatment

Fixed muscles were cut into thick muscle Sect. (6 × 3 × 1 mm³). After washing in PBS, sections were dehydrated stepwise in 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% methanol (MeOH, 20846.292, VWR) / distilled water (dH₂O), with gentle shaking at room temperature (RT) for 1 h each. Tissue sections were then washed twice in 100% methanol (1 h, RT), followed by incubation in a 66% dichloromethane (DCM, 5895811000, Sigma-Aldrich) / 33% methanol solution overnight (ON) at RT. Tissue sections were rehydrated once again stepwise in 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% MeOH/dH₂O with gentle shaking (1 h, RT) each. They were then washed twice with 0.2% Triton X-100 (X100, Sigma-Aldrich) in 1X PBS (1 h). Afterward, they were soaked (ON, 37 °C) in a permeabilization solution containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, D4540, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3 M glycine (G7126, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.02% sodium azide (S2002, Sigma-Aldrich) in 1X PBS, with gentle shaking.

Vascular staining

Following iDISCO + clearing pretreatment, sections were incubated with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin conjugated with Dylight 594 (LEL DyLight 594, Invitrogen, L32471), diluted 1:50 in labeling solution (0.2% Tween 20, 10% DMSO, 0.02% sodium azide in 1X PBS) with gentle shaking (7 days, 37 °C). Next, sections were washed with 0.1% Tween 20 (P1379, Sigma-Aldrich) in 1X PBS (1 day) before proceeding with the clearing procedures.

iDISCO + clearing protocol

Stained sections were gradually dehydrated using the same procedure described above and were then incubated (ON, RT) in a solution of 66% dichloromethane (DCM) / 33% methanol (MeOH), washed twice in 100% DCM (20 min), and subsequently stored in dibenzyl ether (DBE, 108014, Sigma-Aldrich) at RT.

CUBIC clearing protocol

iDISCO + cleared sections were rehydrated stepwise in 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% MeOH / dH₂O, with each step involving gentle shaking (RT, 1 h). Tissue sections were then washed three times with 1X PBS for 1 h each. Next, they were transferred to a 50% CUBIC-L (T3740, TCI) / 50% dH₂O solution (ON, 37 °C), followed by incubation with 100% CUBIC-L with gentle shaking (2 days, 37 °C). Following three washes with 1X PBS, sections were transferred to 50% CUBIC-R (T3741, TCI) (overnight, RT) and clarified a second time with CUBIC-R+ (T3741, TCI) (2 days, RT). Finally, sections were mounted with fibers oriented transversally on a cavity slide (Sigma-Aldrich, BR475565) using CUBIC-R+ (refractive index 1.52), and a 0.17 μm thick coverslip was placed on top before imaging.

Multiphoton microscopy imaging

Images were acquired using a laser scanning multiphoton microscope (A1R-MP+, Nikon Europe B.V., Amstelveen), coupled with a tunable laser (Insight DeepSee, Spectra Physics, France) operating in the wavelength range of 680–1300 nm, with a pulse duration of 120 femtoseconds at a repetition frequency of 80 MHz. A motorized half-wave plate (MKS-Newport, USA) was used to control the laser polarization angle, which was adjustable between 45° and 90°. The objective lens employed for imaging was a Plan-Apo Lambda S 25X silicon objective (refractive index 1.406, MRD73250, Nikon Europe B.V.), with a numerical aperture (NA) of 1.05 and a working distance (WD) of 0.55 mm. The microscope was equipped with eight non-descanned detectors (NDDs), four for backward detection and four for forward detection. Further details on the setup are provided in Fig. 7.

3D image acquisition

Excitation at 820 nm coupled with resonant scanning mode was used to acquire green autofluorescence from muscle fibers, red fluorescence from LEL DyLight 594-labeled vessels, and second harmonic generation (SHG) signals. Green autofluorescence and red fluorescence signals were collected in reflection using band-pass emission filters 525/50BP and 629/56BP for muscle fibers and vessels, respectively. SHG signals were collected in both reflection mode (bSHG) and transmission mode (fSHG) using short band-pass filters, 415/10BP. The field of view (FoV) was 297 μm x 297 μm, scanned at 1024 × 1024 pixels, resulting in a pixel size of 0.29 μm. Z-series were collected with a 1 μm step size within a 350 μm depth of the specimen. Tiles and depth scanning were performed to analyze at least 100 fibers, with the step size between tiles fixed at 1 μm. Images were generated as 12-bit ND2 files, and stitching and 3D reconstruction were performed using NIS-Elements software (version 5.20, Nikon Europe B.V).

Deep-learning model training.

Green autofluorescence from muscle fibers was segmented using the U-Net-based deep learning model “SegmentObject.ai” integrated into NIS-Elements software. This model is particularly suitable for segmenting muscle fibers due to its ability to separate densely packed objects. The training dataset comprised seven cropped images (400 × 400 × 10 μm), each containing annotations of 20 manually identified muscle fibers. The patch size was automatically set to 512 × 512. The training process consisted of a minimum of 2,500 epochs across three batches and was conducted on an NVIDIA RTX5000 graphics unit (Driver version 516.40, NVIDIA). The trained model was applied on another dataset comprising eight manually annotated images for validation. The following metrics were measured (details are provided on Supplementary Figure S2 and S3):

-

- Precision: Evaluates the fraction of correctly predicted positive regions out of all predicted positive regions.

-

- Recall: Also known as sensitivity or True Positive Rate, measures how many of the true positive regions were correctly identified.

-

- F1 score: Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall.

-

- Interception Over Union (IoU): Also known as the Jaccard Index, measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth.

The LEL-DyLight594-labeled vasculature was segmented using the “Segment.ai” in NIS-Elements software. The training dataset included three images (200 × 200 × 300 μm) with a patch size automatically set to 256 × 256 pixels. Initial identification of vasculature structures was achieved through thresholding, followed by manual refinement to create accurate binary masks, which served as the ground truth for model training. The model underwent two separate training runs, each consisting of 500 epochs. To validate the vascular segmentation, the same approach previously employed for validating muscle fiber segmentation was applied.

Both segmentation models demonstrated high accuracy (SegmentObject.ai in Table 1, Segment.ai in Table 2, with detailed measurements provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2), with minimal false positives (precision was 0.90 and 0.92 for the muscle fiber model and the microvessel model, respectively). However, some false negatives were observed, as indicated by recall values of 0.82 and 0.77 for the respective models. The Intersection over Union (IoU) score was 0.74 and 0.71 for the muscle fiber and microvessel models, respectively, while the F1-scores were 0.84 and 0.82, further supporting the robustness of the segmentation performance.

Image analysis of the vasculature

Two-dimensional images: Vascularization was evaluated on five regions per animal (n = 6 rats), each measuring 1052 × 1052 μm, using the General Analysis 3 (GA3) module in NIS-Elements software (version 6.10.1, Nikon Europe BV, Amstelveen). Vessels were detected using the trained “Segment.ai” model, which was imported into the GA3 module. The GA3 pipeline (details are provided in Supplementary Figure S4) was then applied to 30 regions (n = 15 from 3 WT rats and 15 from 3 DMDmdx rats) to analyze the vascular structures. For feature extraction, only endomysial vessels were considered by applying the binary mask of muscle fibers. Vessel-to-fiber ratio was determined by dividing the total number of vessels by the total number of fibers. Vessel density was calculated by dividing the number of vessels by the muscle fiber area. Vessel count per fiber and sharing factor were determined by performing a binary operation between muscle fibers and microvessels. To this end, a proximity area was created by expanding the binary mask of vessels by 10 μm in order to identify fibers in close contact with vessels, defining the fiber-to-vessel association.

Three-dimensional images: Vascularization was evaluated on four regions per animal (n = 6 rats), each measuring 526 × 526 × 350 μm, using the GA3 module. The vascular network was detected using the “Segment.ai” model imported into the GA3 pipeline (see Supplementary Figure S5 for additional details) and applied to 24 regions (n = 12 from 3 WT rats and 3 DMDmdx rats). This enabled the extraction of key features: vascular network density, vascular branching, and surface area of vessels embedded within muscle fibers. The extracted data were exported for statistical analysis.

Three-dimensional image analysis of the collagen network

Connective tissue remodeling was evaluated through analysis of SHG endomysial collagen network on four regions of interest (ROIs) per animal (n = 6, rats), each measuring 526 × 526 × 350 μm. 3D rendering and image analysis were performed using the General Analysis 3 (GA3) module in NIS-Elements software (version 6.10.1, Nikon Europe B.V.). A pre-trained deep learning denoising algorithm was applied to the SHG collagen fiber signal to remove shot noise. Subsequently, a spatial “Laplacian of Gaussian” (LoG) filter (Gaussian σ = 2.7, kernel size = 5 × 5) was applied to identify SHG collagen network boundaries. A manual threshold based on edge detection was used for segmenting the SHG+ objects. Muscle fibers were segmented using the previously trained deep learning model specifically designed for muscle fiber segmentation. To restrict the analysis to SHG collagen network in the endomysial region, the segmented binary mask of autofluorescent muscle fibers was expanded by a 3 μm kernel diameter. A logical “AND” operator was then applied between the binary masks of muscle fibers and SHG collagen network. The resulting SHG collagen network binary masks in the endomysial region were used to extract features of interest: density, volume, elongation and inter-fiber distance of SHG+ objects, overlapping surface between collagen network and vessels. The GA3 pipeline is described in detail in Supplementary Figure S6.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.1). Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons between groups were conducted using a linear mixed-effects model, with random effects on muscle, implemented in the lme4 package. All models presented in this study were assessed for independence and normality of residuals, as recommended. For datasets that did not meet these assumptions, a Wilcoxon test was used instead. For SHG dataset, loglinear models were used to compare the distribution of measures previously discretized into classes. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Two-dimensional histomorphometric analysis of global vasculature in rat Biceps femoris muscle. Transverse sections from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats were stained with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin-conjugated with Dylight 594 (LEL DyLight 594) and investigated with two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF). (a) Left panel: muscle fibers and LEL DyLight 594-stained vessels (white arrows) are visualized by green autofluorescence and red fluorescence, respectively. Middle panel: binary mask (blue) highlights muscle fiber area used for isolating endomysial vessels. Right panel: LEL DyLight 594-stained vessels were detected using NIS-Elements software with the Segment.ai module (version 6.10.1, Nikon Europe BV, Amstelveen). Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) The microvessel-to-fiber ratio and vessel density per unit fiber area were determined in both rat groups from 3 WT and 3 DMDmdx rats (15 regions per genotype). At least 100 fibers were analyzed per image. Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model in R (lme4 package). The normality of residuals was verified. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in capillary-to-fiber ratio (p = 0.3) or microvessel density (p = 0.7).

Two-dimensional histomorphometric analysis of muscle fiber-associated vascular features in rat Biceps femoris muscle. Transverse sections from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats were treated to define binary masks of muscle fibers and microvessels. (a) Left: muscle fibers and microvessels were segmented using the SegmentObject.ai module in NIS-Elements software (version 6.10.1, Nikon Europe BV, Amstelveen). Binary mask objects are false-colored to distinguish individual fibers. Right: binary mask between muscle fibers and microvessels were used to define capillary contacts. A proximity area, created by expanding the binary mask of vessels by 9 μm, identifies fibers in close contact with vessels, defining the fiber-to-vessel association. Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) The microvessel count per fiber and sharing factor (which quantifies the number of fibers supplied by a single microvessel) of vessel-fiber interactions were determined in both rat groups from 3 WT and 3 DMDmdx rats (15 regions per genotype). Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model in R (lme4 package). The normality of residuals was verified.

Three-dimensional histomorphometric analysis of microvessels in rat Biceps femoris muscle. Transverse sections from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats were subjected to iDISCO + and CUBIC clearing protocols, stained with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin-conjugated with Dylight 594 (LEL DyLight 594) and subsequently segmented for muscle fibers and the microvessel network. (a) From left to right: First column: visualization of muscle fibers (green autofluorescence) and vasculature (red; LEL-DyLight594). Second column: segmented muscle fibers were identified using the SegmentObject.ai module in NIS-Elements software (version 6.10.1, Nikon Europe BV, Amstelveen). Third column: segmented LEL-DyLight594-stained vascular network was generated using the Segment.ai module in NIS-Elements software. Fourth column: vasculature surface embedded within muscle fibers was detected by applying an “AND” logical function between the binary masks of muscle fibers and vasculature. Individual components are false-colored to distinguish each object. Field of view 1.052 × 1.052 × 0.350 mm. (b) the microvessel volume density, branching count per fiber volume and mean vessel-to-fiber contact surface were determined in both rat groups from 3 WT rats and from 3 DMDmdx rats (12 regions per genotype). Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model in R (lme4 package) for volume density (p = 0.06). Since the residuals were not normally distributed within the model, a Wilcoxon test was used for the branching and vessel-to-fiber contact surface datasets. Significance levels were set as follows: *0.01 < p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Three-dimensional representations of the vasculature in the Biceps femoris muscle. Tissues were collected from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats. (a) Left: 3D reconstruction of the vascular organization stained with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (LEL) DyLight 594 in 1.052 × 1.052 × 0.350 mm³ images. Right: Top view of the vascular network, generated using a filament algorithm from Imaris software (version 10.1, Oxford Instruments), with false coloration applied to differentiate vascular structures within the binary mask. (b) Quantification of mean diameter and microvessel length. Each group consisted of 3 WT rats and 3 DMDmdx rats. For each animal, 150 microvessels were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test. *0.01 < p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Three-dimensional representation of SHG signal in rat Biceps femoris muscle. (a) Left: three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of SHG collagen fibers in a 350 μm-thick muscle section from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats (field of view 1.052 × 1.052 × 0.350 mm³). The image was processed with a Laplacian of Gaussian filter to enhance fiber boundaries. Right: individual SHG collagen fibers were detected using the GA3 module in NIS-Elements software (Nikon Europe BV, Amstelveen, Netherlands), with false-coloring applied to the binary mask. (b) Bar graphs illustrate features characterizing endomysial SHG+ objects: density, volume, distance separating objects and elongation of objects. Data were determined in both rat groups considering 3 animals per group and 4 regions each. Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test for SHG density. For volume, distance, and elongation datasets, data were discretized into classes, and a log-linear model was applied to compare the distribution between groups. *0.01 < p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Two and three-dimensional representations of vasculature and collagen network in the rat Biceps femoris muscle. Tissue sections from 1-year-old wild-type (WT) and dystrophic (DMDmdx) rats were stained with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin-conjugated with Dylight594 (LEL DyLight594) and subjected to SHG. (a) DyLight594-stained vasculature and SHG collagen network were detected in thin tissue sections (left), thick tissue sections (middle) and alongside a binary mask highlighting the overlapped regions (right). Arrows indicate SHG collagen network encapsulating red-stained vessels. Overlapped regions are false-colored for clarity. (b) Microvessel volume overlapped by SHG was determined in both rat groups considering 3 animals per group (4 regions per rat). A Wilcoxon test was used for statistical analysis. *** p < 0.001.

Experimental workflow for muscle fiber autofluorescence, microvessel staining, SHG imaging and 3D analyses from cleared muscle samples. (a) Overview of the sample preparation steps, including iDISCO+/CUBIC clearing protocols. (b) Representative images of the Biceps femoris muscle before and after the clearing protocols. (c) Multiphoton microscope setup for fluorescence and harmonic imaging. The configuration of emission filters is displayed above the GaAsP and PMT detectors. Excitation signals are shown in red, and emission signals in black and purple. (d) Representative images from DMDmdx rat muscle. Top left: Muscle fibers visualized using green autofluorescence. Top right: Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (LEL) DyLight 594-stained microvessels detected as red fluorescence. Bottom left: SHG imaging in both backward and forward directions from cleared sections. Bottom right: Merged autofluorescence, vascular staining, and SHG signals. White arrows indicate vessels, and white arrowheads highlight SHG signals. Scale bar: 100 μm. (e) Summary of the workflow applied to extract 3D features from cleared muscle samples.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bushby, K. M. D. Genetic and clinical correlations of Xp21 muscular dystrophy. J. Inher Metab. Disea. 15, 551–564 (1992).

Hoffman, E. P., Brown, R. H., Kunkel, L. M. & Dystrophin the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. (1987).

Bonilla, E. et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: deficiency of dystrophin at the muscle cell surface. Cell 54, 447–452 (1988).

Desguerre, I. et al. Endomysial fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A marker of poor outcome associated with macrophage alternative activation. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68, 762–773 (2009).

Kohler, M. et al. Disability and survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 80, 320–325 (2009).

Mazur, W. et al. Patterns of left ventricular remodeling in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cardiac MRI study of ventricular geometry, global function, and strain. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 28, 99–107 (2012).

Gillies, A. R. & Lieber, R. L. Structure and function of the skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Muscle Nerve. 44, 318–331 (2011).

Brashear, S. E. et al. Collagen cross-links scale with passive stiffness in dystrophic mouse muscles, but are not altered with administration of a Lysyl oxidase inhibitor. PLoS ONE. 17, e0271776 (2022).

Loufrani, L. et al. Flow (Shear Stress)–Induced Endothelium-Dependent dilation is altered in mice lacking the gene encoding for dystrophin. Circulation 103, 864–870 (2001).

Latroche, C. et al. Structural and functional alterations of skeletal muscle microvasculature in Dystrophin-Deficient Mdx mice. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 2482–2494 (2015).

Kodippili, K., Thorne, P. K., Laughlin, M. H. & Duan, D. Dystrophin deficiency impairs vascular structure and function in the canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Pathol. 254, 589–605 (2021).

Nguyen, F., Guigand, L., Goubault-Leroux, I., Wyers, M. & Cherel, Y. Microvessel density in muscles of dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 15, 154–163 (2005).

Loufrani, L. et al. Absence of dystrophin in mice reduces NO-Dependent vascular function and vascular density: total recovery after a treatment with the aminoglycoside gentamicin. ATVB 24, 671–676 (2004).

Strupler, M. et al. Second harmonic imaging and scoring of collagen in fibrotic tissues. Opt. Express. 15, 4054 (2007).

Lagerweij, T. et al. Optical clearing and fluorescence deep-tissue imaging for 3D quantitative analysis of the brain tumor microenvironment. Angiogenesis 20, 533–546 (2017).

Fuentes-Corona, C. G. et al. Second harmonic generation signal from type I collagen fibers grown in vitro. Biomed. Opt. Express. 10, 6449 (2019).

Aghigh, A. et al. Second harmonic generation microscopy: a powerful tool for bio-imaging. Biophys. Rev. 15, 43–70 (2023).

Clarke, R. J. & Oprysa, A. Fluorescence and light scattering. J. Chem. Educ. 81, 705 (2004).

Schwertner, M., Booth, M. J. & Wilson, T. Specimen-induced distortions in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 228, 97–102 (2007).

Rothstein, E. C., Carroll, S., Combs, C. A., Jobsis, P. D. & Balaban, R. S. Skeletal muscle NAD(P)H Two-Photon fluorescence microscopy in vivo: topology and optical inner filters. Biophys. J. 88, 2165–2176 (2005).

Schneidereit, D. et al. An advanced optical clearing protocol allows label-free detection of tissue necrosis via multiphoton microscopy in injured whole muscle. Theranostics 11, 2876–2891 (2021).

Richardson, D. S. & Lichtman, J. W. Clarifying Tissue Clearing Cell 162, 246–257 (2015).

Renier, N. et al. A simple, rapid method to Immunolabel large tissue samples for volume imaging. Cell 159, 896–910 (2014). iDISCO.

Pichon, J. et al. Label-free 3D characterization of cardiac fibrosis in muscular dystrophy using SHG imaging of cleared tissue. Biol. Cell.. 114, 91–103 (2022).

Susaki, E. A. et al. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat. Protoc. 10, 1709–1727 (2015).

Granger, D. N. & Senchenkova, E. Inflammation and the Microcirculation. 2 (2010).

Latroche, C. et al. Skeletal muscle microvasculature: A highly dynamic lifeline. Physiology 30, 417–427 (2015).

Hudlická, O. Growth of capillaries in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 50, 451–461 (1982).

Deveci, D., Marshall, J. M. & Egginton, S. Relationship between capillary angiogenesis, fiber type, and fiber size in chronic systemic hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281, H241–H252 (2001).

Nederveen, J. P., Betz, M. W., Snijders, T. & Parise, G. The importance of muscle capillarization for optimizing satellite cell plasticity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 49, 284–290 (2021).

McKey, J., Cameron, L. A., Lewis, D., Batchvarov, I. S. & Capel, B. Combined iDISCO and CUBIC tissue clearing and lightsheet microscopy for in Toto analysis of the adult mouse ovary†. Biol. Reprod. 102, 1080–1089 (2020).

Glancy, B. et al. In vivo microscopy reveals extensive embedding of capillaries within the sarcolemma of skeletal muscle fibers. Microcirculation 21, 131–147 (2014).

Kharraz, Y., Guerra, J., Pessina, P. & Serrano, A. L. Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Understanding the process of fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 1–11 (2014).

Giovarelli, M. et al. Characterisation of progressive skeletal muscle fibrosis in the Mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an in vivo and in vitro study. IJMS 23, 8735 (2022).

Podkalicka, P. et al. Age-Dependent dysregulation of muscle vasculature and blood flow recovery after hindlimb ischemia in the Mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biomedicines 9, 481 (2021).

Podkalicka, P., Mucha, O., Dulak, J. & Loboda, A. Targeting angiogenesis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 1507–1528 (2019).

Lattouf, R. et al. Picrosirius red staining: A useful tool to appraise collagen networks in normal and pathological tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 62, 751–758 (2014).

Lapierre-Landry, M., Liu, Y., Bayat, M., Wilson, D. L. & Jenkins, M. W. Digital labeling for 3D histology: segmenting blood vessels without a vascular contrast agent using deep learning. Biomed. Opt. Express. 14, 2416 (2023).

Larcher, T. et al. Characterization of dystrophin deficient rats: A new model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS ONE. 9, e110371 (2014).

Verma, M. et al. Inhibition of FLT1 ameliorates muscular dystrophy phenotype by increased vasculature in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008468 (2019).

Bosco, J. et al. VEGFR-1/Flt-1 Inhibition increases angiogenesis and improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Therapy - Methods Clin. Dev. 21, 369–381 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Boisbonne Center (Oniris, Nantes, France) for animal care and the APEX platform (INRAE/Oniris, Center of Excellence Nikon Nantes [CENN], Nantes, France) from UMR 0703 PAnTher (INRAE/Oniris, Nantes, France) for their valuable technological support. We also extend our gratitude to the FAIR CHARM consortium (H2020 program, in which UMR 703 PAnTher is a partner) for fostering a collaborative scientific environment through discussions and the sharing of biological materials. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Région Pays de la Loire and NeurATRIS: A Translational Research Infrastructure for Biotherapies in Neurosciences , “Investissement d’Avenir-ANR-11-INBS-0011”. The authors also thank Biogenouest (the network of technology core facilities in Western France in life sciences and the environment, supported by the Conseil Régional des Pays de la Loire) for supporting APEX.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.H. conceived, designed, and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.L. assisted with sample clearing. C.T. performed statistical analysis, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. T.F. supervised the study, assisted with data acquisition, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.A.C. supervised the study, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. K.R. supervised the study, contributed to data interpretation, and participated in manuscript writing. L.D. supervised the study, conceived and designed the experiments, contributed to data interpretation, and participated in manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassani, I., Ledevin, M., Thorin, C. et al. Multiphoton microscopy and tissue clearing for 3D characterization of the vasculature and fibrosis remodeling in rat dystrophic skeletal muscle. Sci Rep 15, 36686 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20335-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20335-9