Abstract

Acoustic band gap waveguide structures with resonant modes open up a new and original avenue of research in the field of detection. This paper focuses on using a structure of Helmholtz resonators parallel to lateral duct with a central defect cell as a high-sensitivity harmful gas sensor. The numerical analysis was carried out using the finite element method based on a COMSOL Multiphysics simulation. A central defect waveguide containing four lateral ducts leads to the emergence of a localized resonant mode, the positions of which can be controlled by modifying the acoustic properties of the gas samples and the geometric dimensions of the system. This resonance peak reaches a very high transmission intensity in the acoustic band gap, between 92% and 100%, for all the gas samples, reflecting the strong localization of the acoustic waves in the defective cell and therefore, good acoustic energy transfer performance at specific frequencies. Various geometric configurations were analyzed as part of this study in order to determine the optimum parameters of the sensor using the propane sample with air. Under optimal conditions, the sensor recorded a sensitivity of 3.8 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), a high figure of merit of 380.7 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\), and a very exceptional quality factor of 129,422. These characteristics reveal a significant improvement in the efficiency of detecting leaks of harmful gases into the air using the proposed sensor. Furthermore, the sensor exhibits significant peak shift linearity with sound speed, reflecting a very stable sensitivity in all gas samples. Thanks to these important results and the design simplicity, the proposed model of parallel resonators with a central defect can be exploited mainly for gas sensors and powerful detection applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The acoustic wave manipulation in phononic crystals (PnCs) or acoustic periodic structures, known for their unique characteristics and great adaptability, is taking on an increasingly important part in current scientific research1,2,3,4. The physical properties of these artificial structures are essentially reflected in their capacity to generate specific frequency ranges with zero acoustic transmission, known as ABGs5,6,7,8. These forbidden frequency ranges are characterized by high efficiency in perfectly reflecting the acoustic wave, thanks to periodic arrangements of the materials’ acoustic impedances or different geometries. The physical phenomena responsible for ABGs formation are essentially Bragg scattering due to multiple destructive interferences and the local resonance mechanism based on resonant cavities9,10,11,12. The adjustment of these ABGs in specific frequency ranges is linked to the mechanical or geometrical properties of materials and systems13,14. As a result, these structures have recently become attractive for their various innovative applications, including selective filtering, waveguiding, low-frequency noise reduction, and multiplexing systems15,16,17.

The insertion of geometric or material defects at specific positions within a periodic PnC leads to the appearance of localized resonant states in the ABGs, corresponding to defect modes18,19,20. These resonance peaks are generated by the waves’ strong localization in the defect cell. This phenomenon is analogous to the creation of defect states in photonic crystals (PCs)21,22. Furthermore, as the acoustic impedance of PnCs is proportional to the density and sound speed in the medium, the tunability of these acoustic properties reveals the importance of periodic and quasi-periodic PnCs for gas and liquid sensing applications23,24,25,26,27. For example, a biosensor proposed by Almawgani et al. has been developed from a periodic and quasi-periodic PnCs structure whose defect layer is filled with a sodium iodide (NaI) solution. The results show high sensor performance at all NaI solution concentrations28. Sayed et al. focused on the detection of different concentrations of lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2) using a quasi-periodic PnC based on Fibonacci, Octonacci, Thue-Morse and double-period sequences. A defect layer filled with Pb(NO3)2 solution was also used, leading to the creation of a resonance mode in the transmission spectrum. They also found that the double-period sequence offered the best sensor performance, with significant sensitivity and quality factor29. In addition, recent studies have largely focused on controlling resonance peaks within the Acoustic band gap (ABG) in order to develop gas sensors based on acoustic waveguide systems with connected resonators6,30. The engineering of these fluid-filled acoustic resonator structures has enabled the design of highly accurate and tunable harmful gas detection systems31,32.

Zaky et al., have developed an open and closed periodic resonator structure with a central waveguide defect as a powerful gas biosensor with optimum sensitivity, figure of merit and quality factor33. Additionally, a PnC based on closed resonators with a waveguide defect shows that gas properties, and in particular the sound speed, have a significant influence on the resonance peak displacement for different gas samples34. Consequently, these studies highlight the need for further exploration of PnC-based systems to optimize the detection properties of harmful gases and detect their leakage in the air. In 2023, El Malki et al.35 experimentally validated theoretical predictions regarding HRs featuring extended necks. Their findings demonstrated strong agreement between the theoretical models and experimental results. Zaky et al.36 investigated parallel HRs incorporating a central HR defect, employing both the transfer matrix method (TMM) and finite element method (FEM). Their results revealed excellent consistency between the TMM simulations and FEM analyses.

This study, therefore, examines the effectiveness of a Helmholtz resonator parallel to lateral duct (HRPLD) system with a central defect as a harmful gas sensor. In fact, colorless and odorless harmful gases are dangerous if released into the air. The latter are particularly harmful when inhaled and are mainly linked to oxygen depletion (risk of asphyxiation). The main objective is to analyze the tunable sensing properties in this structure by replacing the air sample with \(\:{O}_{2}\), \(\:Ar\), \(\:{CO}_{2}\) and \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) samples in order to improve the proposed sensor’s performance. The numerical results of this study are accurately obtained using the finite element method (FEM) based on COMSOL Multiphysics software. The use of FEM to control the acoustic wave propagation in different Helmholtz resonator models has attracted considerable interest in recent decades due to its accuracy and reliability37,38. The defective cell is characterized by its unique design, consisting of a waveguide containing four lateral cylindrical ducts. The central position of this defect type in the system leads to the generation of a resonant mode corresponding to a defect mode in the ABG with a very high transmittance intensity. The position and acoustic intensity of this resonance peak were well controlled by changing the gas samples in descending order of sound speed. Furthermore, the results show a high linearity of resonance peak displacements with samples’ sound speed, demonstrating a very stable sensitivity of the proposed sensor compared to other designs. This property shows outstanding sensor performance, with exceptional merit and quality factor, using optimal parameters of the system. This improvement is specifically due to the unique design of our HRPLD system, which has demonstrated its considerable effectiveness in the precise detection of gases hazardous to human health and the environment.

Numerical model

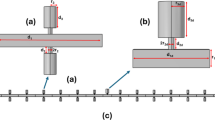

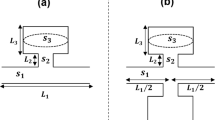

This study focuses on the periodic structure of HRPLD with a cylindrical neck and cavity connected to a main air duct with a defective cell placed at the center of the structure. The unit cell of the network is shown in Fig. 1a, where \(\:{d}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{1}\) are, respectively, the length and height of the rectangular main duct, \(\:{d}_{2}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are the length and radius of the neck, and \(\:{d}_{3}\:\) and \(\:\:{r}_{3}\) are the length and radius of the cavity. The defective cell consists of a main guide with four lateral ducts, as shown in Fig. 1b, where \(\:{d}_{1d}\) is the length of the main guide, and \(\:{d}_{2d}\) and \(\:{r}_{2d}\) are the length and radius of the cylindrical lateral ducts, respectively. The complete schematic of the proposed sensor is clearly shown in Fig. 1c.

As part of the numerical modelling carried out in COMSOL Multiphysics, acoustic excitation was applied via a rectangular aperture placed at the entrance to the main duct (Fig. 1c), with a pressure amplitude defined at 1 Pa, under an ambient temperature set at 293.15 K. The entire model is based on the sound pressure interface in the frequency domain37. The Linear acoustic modulus is taken into account in the simulation procedure. The fluid was considered to be stationary so that wave propagation in the system is not influenced by the flow velocity for a Mach number of less than 0.1. In this context, the problem has been simplified by focusing on the system’s acoustic response and practically ignoring the fluid’s dynamic effects on wave propagation39,40.

To model acoustic wave propagation in the periodic structure of HRPLDs with a central defect, the Helmholtz equation is used, taking into account the fluid density (\(\:\rho\:\)) and acoustic pressure sources (p)41. To accurately model complex geometries, and in particular waveguide systems linked by HRPLDs, a free tetrahedral mesh, characterized by a high level of refinement, was used36,42,43. This mesh has element sizes of between 0.02 m and 0.04 m. To optimize the quality of the results, the meshing method included a growth factor of 1.45, a curvature refinement coefficient of 0.1, and a specific resolution for narrow regions of 1.1. These parameters were decisive in guaranteeing the reliability of the FEM simulations.

Results

The sensor model proposed in this work consists of \(\:\left({\text{H}\text{R}\text{P}\text{L}\text{D})}^{N}\:Defect\:\right({\text{H}\text{R}\text{P}\text{L}\text{D})}^{N}\:\)with the number of periods (\(\:N\)). The geometric dimension parameters are chosen as follows: \(\:{d}_{1}=0.5\:m\), \(\:{d}_{2}=0.03\:m\), \(\:{d}_{3}=0.1\:m,\:{d}_{3C}=0.11\:m,\) \(\:{r}_{1}=0.06\:m\), \(\:{r}_{2}=0.01\:m,\:{r}_{3}=0.03\:m\), \(\:{d}_{1d}=0.26\:m\), \(\:{d}_{2d}=0.15\:m\), \(\:{r}_{2d}=0.01\:m\) and \(\:N=6\). The initial conditions ensure that the gas samples in the sensor guides are in a static state at atmospheric pressure and ambient temperature.

First, we have studied the acoustic wave propagation at normal incidence within the proposed sensor using an air sample with a sound speed of \(\:340\:m/s\) and a mass density of \(\:1.2\:kg/{m}^{3}\). Figure 2 shows transmittance spectra as a function of frequency for a periodic structure of HRPLDs without defects (blue line) and with a defective central cell made up of four lateral ducts (orange line). The band structure in Fig. 2a is plotted using transfer matrix method (TMM). For more details about the TMM, see Ref42.

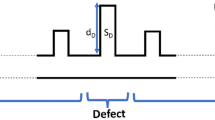

As shown in Fig. 2 (blue line), an ABG was created between the frequency range 1020.0 Hz and 1121.9 Hz, where the waves are completely reflected. This phenomenon is essentially due to the dynamic interaction between incident acoustic waves and the system’s resonant cavities, as a result of multiple local resonances11. Furthermore, the introduction of a defect in the center of the periodic structure leads to a significant change in resonance conditions, creating a very narrow defect peak within the ABG. The creation of this peak is mainly due to the emergence of a localized mode induced by the geometric perturbation of the system6,34. In particular, the presence of a defect Guide with four lateral ducts in the middle of the design leads here to the formation of a very fine resonance peak in the ABG at the 1063.87 Hz position, as shown by the orange line in Fig. 2. The transmittance intensity of this peak is very high (99%), which explains the strong confinement of the acoustic waves in the defective cell. These results clearly demonstrate the critical impact of geometric defects on acoustic wave behavior and their potential applications, mainly in the design of powerful selective filters.

Figure 3 shows the total sound pressure level distribution along the air-filled sensor at five different frequencies: 1010 Hz (Fig. 3a), 1040 Hz (Fig. 3b), 1063.8 Hz, (Fig. 3c), 1090 Hz (Fig. 3d) and 1130 Hz (Fig. 3e) respectively. Due to the impact of a resonant mode, the total sound pressure level at frequency 1063.8 Hz is considerably elevated in the defect cell, as clearly shown in Fig. 3c. This is due to a strong confinement of acoustic waves in the defective cell, which explains the origin of localized states or resonant peaks in the ABG. On the other hand, Fig. 3b and d, corresponding to frequencies of 1040 Hz and 1090 Hz, show a significant decrease in the total sound pressure level along the structure, particularly in the resonant cavities. This can be explained by the influence of local resonances of the resonators, which induce multiple reflections of acoustic waves. This distribution of the total sound pressure level therefore interprets the physical phenomena of the transmittance spectra results detailed above in Fig. 2.

Modulation of gas samples’ acoustic properties, in particular their sound speed and mass density, has a considerable influence on the behavior of acoustic wave propagation in the proposed sensor. For this reason, we have replaced the air sample (used as an indicator) with a sample of \(\:{O}_{2}\), \(\:Ar\), \(\:{CO}_{2}\) and \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\). The precise values of sound velocity and mass density under the working conditions for each sample are clearly illustrated in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 4(a-e), the kind of gas sample that fills the sensor tubes affects ABG’s properties and the peak of defects it contains. Specifically, the ABG ranged from 1030.91 to 1104.28 Hz (Fig. 4a), 988.47 to 1059.83 Hz (Fig. 4b), 967.89 to 1036.23 Hz (Fig. 4c), 810.06 to 867.57 Hz (Fig. 4d), and 755.65 to 808.90 Hz (Fig. 4e), respectively. Similarly, sound speed and mass density directly influence the resonance peak frequency. This is strongly shifted towards lower frequencies (red shift) as sound speed decreases from 340 m/s (Air) to 249 m/s (\(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\)), as shown in Table 1. The standing wave Eq. (1) explains considerably the dependence between the peak resonance frequency and the speed of sound30,34. Moreover, the peak resonance transmittance intensity within the ABG remains 99% maximum for all gas samples, demonstrating the enhanced capacity of this defect type to confine acoustic waves within their cell. Consequently, these results reflect the effect of gas properties on the resonance peak behavior, with a view to various applications such as the development of high-transmittance narrow acoustic filters and precision gas detection.

where \(\:d\) and \(\:\:n\:\) represent the defect length and an integer, respectively. While \(\:c\:\) and \(\:{\:f}_{R\:}\) are the sound speed and resonance peak frequency of each sample, respectively.

The overall aim of this study is to optimize the gas sensor efficiency and performance of the proposed sensor. To this end, optimization parameters such as sensitivity (S), figure of merit (FoM), quality factor (Q) and gas sample limit of detection (LoD) are precisely calculated using the following Eqs6,34. :

Based on Eq. (2), the proposed sensor recorded a fixed sensitivity of 3.12 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\:\) for all samples, as shown in Table 1. This sensitivity stability suggests that the relation between peak resonance frequency and sound speed for each sample is linear (direct proportionality)30. The \(\:FoM\) also remains constant at 3.2 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\) for all samples, due to their proportional relation with sensitivity described in Eq. (3). While the total width at half-maximum of the resonance peak (FWHM) for the air sample is equal to 0.974 Hz. Also, the Q-factor decreases from 1047 (\(\:{O}_{2}\)) to 800 (\(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\)), depending on the change in resonance frequency and, therefore, the acoustic properties of each sample (Eq. 4). According to Eq. (5), LoD remains virtually fixed at \(\:1.6\times\:{10}^{-2}\) m/s, as Table 1 clearly shows. These results clearly demonstrate the impact of the acoustic properties of the different gas samples (sound velocity and mass density) on the acoustic wave propagation in the proposed HRPLDs sensor.

In the context of optimizing the proposed sensor’s performance, the system’s geometric properties, such as number of periods, defect length and unit cell length, will be examined in the following section, using a \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample.

Figure 5(a-b) presents the variation of transmittance spectra with increasing period numbers \(\:N=6\), \(\:N=7\), \(\:N=8\), \(\:N=9\) and \(\:N=10\). It clearly shows that the resonance peak frequency does not change with increasing period number \(\:N\). This peak seems to remain constant in the air sample as the period number \(\:N\) increases from 6 to 10 as shown in Table 2. When the proposed HRPLD system is filled with a \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample, this resonance peak shifts to lower frequencies at 779.22 Hz compared to the air sample due to the change in the acoustic properties of the gas (Fig. 5b), while remaining constant for all numbers of periods \(\:N\). This stability reveals a pronounced overlap of defect peaks but also has the advantage that the position of the resonance peak can be well localized in the ABG independently of the number of periods \(\:N\). The period number effect on peak position analyzed here is perfectly consistent with other sensor designs that are based on acoustic wave propagation6,34. Furthermore, Fig. 5a shows that increasing the period number \(\:N\) substantially decreases the resonance peak width, which has a considerable influence on the FWHM of the air sample peak. Evidently, this FWHM decreases significantly from 0.974 to 0.085 Hz with increasing \(\:N\) from 6 to 10, as illustrated in Table 2. The sensitivity, FoM, Q-factor and LoD are also calculated in Table 2 as a function of increasing \(\:N\). When \(\:N\) increases from 6 to 10 periods, the sensitivity remains constant, recording the same value of 3.13 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\). This proves that varying the period number has no significant influence on the sensitivity of the sensor. This property is consistent with other gas sensors (1D-PnCs) examined by Zaky et al.30,34. Furthermore, with increasing \(\:N\) from 6 to 10 periods, the FoM increases significantly from 3.2 to 36.7 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\), reflecting the inverse relation with the FWHM described in Eq. (3). Due to the inverse proportionality between the Q-factor and the FWHM (Eq. 4), this factor increases considerably with increasing \(\:N\), rising from 1092 (\(\:N=6\)) to 12,492 (\(\:N=10\)), reflecting the efficiency of the proposed sensor at \(\:N=10\) periods. This is well confirmed by the variation in LoD, which shows a decrease with increasing \(\:N\) down to \(\:1.4\times\:{10}^{-3}\) m/s for \(\:N\) of 10 periods. Thus, \(\:N=10\) is the optimum period.

The effect of defect duct length on the proposed sensor performance is well examined in this part of the work. Transmittance spectra versus frequency at different defect lengths \(\:{d}_{1d}\) are presented in Fig. 6a for the air sample, and Fig. 6b for the \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample. The results clearly show that the resonant peak frequencies are very sensitive to any change in length \(\:{d}_{1d}\). When the defective guide length\(\:\:{d}_{1d}\) is increased from 0.2 m to 0.3 m, the resonance peaks are red shifted within the ABG from 1097.1 Hz to 1042.34 Hz for the air sample, and from 803.48 Hz to 763.425 Hz for the \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample. This significant influence on the resonance peak position is essentially due to the increased interaction between the propagated acoustic waves and the defect tube length. In addition, the variation of \(\:{d}_{1d}\:\)slightly affects the transmittance intensity of the resonance peak, as shown in Fig. 6(a-b). Thus, the sensor records a perfect transmittance of 100% at \(\:{d}_{1d}=0.24\) m for the air sample, which explains the high concentration of waves in the defective cell at this length.

The gradual increase in \(\:{d}_{1d}\) from 0.2 to 0.3 m shows a slight decrease in the sensor sensitivity from 3.23 to 3.07 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\:\)as seen in Table 3. This phenomenon can be explained by the red shift of the defect peaks using Eq. (2), which is directly proportional to the variation in the resonance peak of the air sample and \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\). Table 3 also shows that this sensor records the best values for FWHM, FoM, Q-factor and LoD at length \(\:{\:d}_{1d}=0.24\) m, i.e. 0.047 Hz, 67.98 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\), 23,113 and \(\:\:7.4\times\:{10}^{-4}\:\)m/s, respectively. This proves that the length \(\:{\:d}_{1d}=0.24\) m is optimal and that the proposed HRPLD sensor therefore performs better. Consequently, the defect length of 0.24 m will be fixed and used thereafter to ensure the best performance of the proposed sensor.

In order to optimize the proposed sensor’s performance, the impact of unit cell length \(\:{d}_{1}\) on the sensor’s acoustic transmittance is also analyzed in Fig. 7 using an air sample (blue curve) and a \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample (orange curve). As with the effect of the defect length \(\:{d}_{1d}\) on the resonance peak (Fig. 6), varying the length \(\:{d}_{1}\:\) has a significant effect on the resonance peak position and the ABGs. Specifically, the progressive increase in length \(\:{d}_{1}\) from 0.40 to 0.54 m shifts the resonance peak considerably towards the red, from 1293.57 to 1020.36 Hz for the air sample and from 947.34 to 747.26 Hz for the \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample. However, the transmittance intensity remains high, varying between 96% and 100% with the variation in \(\:{d}_{1}\), reflecting the strong localization of acoustic waves inside the defect tubes. The results obtained show excellent control of the resonance peak inside the ABG for the air and \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) samples, which makes it possible to design high quality narrow transmittance filters. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 7, increasing \(\:{d}_{1}\) also increases the ABG width and, in particular, that of the air sample. Thus, the interaction of the acoustic wave and the air sample in the sensor is stronger than that of \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) due to its lower density (air). This characteristic is important in determining whether the \(\:{C}_{3}{H}_{8}\) sample is escaping from the system.

In order to determine the best optimization parameters to obtain the highest performance from the proposed sensor, Table 4 shows the sensitivity, FWHM, FoM, Q-factor and LoD for different unit cell lengths \(\:{d}_{1}\). Due to the red shift of the defect peaks, the sensitivity decreases in the order of 3.8 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\) to 3.6 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), 3.5 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), 3.4 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), 3.3 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), 3.2 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), 3.1 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\) and 3.0 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\) as \(\:{d}_{1}\) increases by 0.40 m, 0.42 m, 0.44 m, 0.46 m, 0.48 m, 0.50 m, 0.52 m and 0.54 m, respectively. The sharp decrease in the FWHM of the defect peak for the air sample as a function of increasing \(\:{d}_{1}\) is clearly illustrated in Table 4. At \(\:{d}_{1}=0.54\) m, the sensor exhibits the lowest FWHM value of 0.0079 Hz, reflecting the best acoustic energy transmittance performance in the resonance peak. Using Eqs. (6) and (7), the sensor records the highest/improved values of FoM (380.7 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\)) and Q (129422) at the same length \(\:{d}_{1}=0.54\) m. This is confirmed by the LoD, which gives the lowest value of \(\:1.4\times\:{10}^{-4}\:\)m/s at \(\:{d}_{1}=0.54\) m. Consequently, given that the best optimization parameters are obtained at a unit cell length of 0.54 m, the latter will be optimal.

Next, the relation between acoustic speed and resonant peak frequency for different gas samples:\(\:{\:C}_{3}{H}_{8}\), \(\:{CO}_{2}\), \(\:Ar\), \(\:{O}_{2}\) and Air respectively, are illustrated in Fig. 8. Using the optimum parameters selected previously, the results confirm the linearity of the proposed sensor described by Eq. (6) below, with a constant sensitivity of 3.00 Hz.s.m-1 s, for all samples:

Finally, a comparative study of the sensor proposed with other sensors based on PnCs is presented in Table 5. The optimization parameters show a considerable improvement in the efficiency of the HRPLD gas sensor proposed here, with a sensitivity of 3.8 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), a significant FoM of 380.7 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\), a very exceptional Q-factor of 129,422 and a very low LoD of \(\:1.4\times\:{10}^{-4}\:\)m/s, compared with that of other models6,30,31,34. In addition, the resonance peak displacement linearity indicating constant sensitivity is well achieved in this work reflecting a high performance of this proposed.

The sensor’s selectivity was rigorously evaluated by testing its response to varying \(\:C{O}_{2}\) concentrations (0-100 ppm) within dry exhaled breath (DEB), a complex gas mixture containing \(\:{N}_{2}\), \(\:{O}_{2}\), \(\:C{O}_{2}\), and trace gases. More details about the acoustic properties of DEB are discussed in Ref23. As shown in Fig. 9, the sensor maintained excellent response characteristics across all tested concentrations while effectively rejecting interference from other mixture components.

The proposed sensor exhibits exceptionally fast response and recovery times due to its operation principle. Unlike sensors that rely on chemical reactions or adsorption processes, this design only requires the gas composition to fill the structure, enabling immediate measurements45,46. Besides, the proposed model demonstrates excellent stability and reusability, as it can be either cleaned or internally coated with a protective layer to prevent gas interactions.

The proposed sensor demonstrates a significant improvement in sensitivity (3.8 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\)) compared to previously reported acoustic metamaterial-based sensors. In Ref36., where the unit cell comprises two identical PHRs and the defect cell is a single HR, the achieved sensitivity is 1.14 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\) approximately 3.3 times lower than that of the proposed design. Similarly, Ref42. employs a unit cell with two PHRs and a horizontal Guide as the defect structure, yielding a sensitivity of only 0.88 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), which is 4.3 times lower than the presented sensor. The enhanced sensitivity of our design can be attributed to its optimized structural configuration, which improves the interaction between acoustic waves and the measured medium, leading to a stronger frequency shift response. Unlike Ref36., which relies on a single HR defect that may limit wave localization, or Ref42., where the horizontal guide defect reduces energy confinement, our sensor’s architecture ensures stronger defect-induced mode coupling and sharper resonance shifts. This advancement makes the proposed sensor more suitable for high-precision applications requiring detection of minute changes in environmental or material properties.

Conclusion

This study proposes an original gas sensor based on a periodic structure of HRPLDs with a central defect guide comprising four lateral ducts. The acoustic wave has been well manipulated in the system by modifying the gas acoustic properties, such as sound speed and mass density, as well as the geometrical parameters of the proposed model. These modifications lead to a significant localization of the acoustic waves in the defective cell, generating fine resonance peaks in the ABG with a high transmittance. Thanks to the Linear relation between the speed of sound and the peak resonance frequency, this system Guarantees stable sensitivity, which improves gases detection performance. By identifying the optimum parameters, the proposed sensor achieves a sensitivity of 3.8 Hz.s.\(\:{m}^{-1}\), a very high FoM and Q-factor of 380.7 s\(\:.{m}^{-1}\) and 129,422 respectively. These results show that the studied structure of HRPLDs as hazardous gas sensors is a good candidate because of its efficiencies and simplicity of design compared with other complex and expensive structures.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from Zaky A. Zaky on reasonable request.

References

Shen, C., Kong, Y., Lu, T. J. & Yang, S. Localization of elastic waves in one-dimensional detuned phononic crystals with flexoelectric effect. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 13, 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475411.2022.2069875 (2022).

Fathy, H. M. et al. Design of one-dimensional phononic crystals comprising robust Fano edge modes as a highly sensitive sensor for alcohols. Front. Phys. 12, 1497294. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2024.1497294 (2024).

Antraoui, I. & Khettabi, A. Study of the defect modes of a finite one-dimensional periodic structure of three different waveguides, Materials Today: Proceedings, 31, S61-S68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.06.064 (2020).

Zaky, Z. A., Malki, M. E., Antraoui, I., Khettabi, A. & Sallah, M. Performance analysis of Thue Morse acoustic resonators for noise reduction. Sci. Rep. 15, 16597. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00903-9 (2025).

Antraoui, I. & Khettabi, A. Properties of defect modes in a finite periodic structure with branched open resonators, Materials Today: Proceedings, 27, 3132–3138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.012 (2020).

Zaky, Z. A., Alamri, S., Zohny, E. I. & Aly, A. H. Simulation study of gas sensor using periodic phononic crystal tubes to detect hazardous greenhouse gases. Sci. Rep. 12, 21553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26079-0 (2022).

Khettabi, A., Bria, D. & Elmalki, M. New approach applied to analyzing a periodic Helmholtz resonator, JMES, 8, 816–824, (2017).

Zaky, Z. A., Antraoui, I., Malki, M. E., Khettabi, A. & Sallah, M. Tunability of acoustic band gaps using Thue Morse quasiperiodic lateral resonators. Sci. Rep. 15, 16183. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99716-z (2025).

Wang, Z. G. et al. Acoustic wave propagation in one-dimensional phononic crystals containing Helmholtz resonators. J. Appl. Phys. 103 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2894914 (2008).

Yan, Z. Z., Zhang, C. & Wang, Y. S. Wave propagation and localization in randomly disordered layered composites with local resonances. Wave Motion. 47, 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wavemoti.2010.02.002 (2010).

Antraoui, I., Khettabi, A., Sallah, M. & Zaky, Z. A. Localized modes and acoustic band gaps using different quasi-periodic structures based on closed and open resonators. Sci. Rep. 15, 7633. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90691-z (2025).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Properties of localized modes and acoustic band gaps using serial closed resonators in generalized Thue Morse quasi periodic sequences. Opt. Quant. Electron. 57, 273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-025-08161-9 (2025).

Zaki, S. E., Mehaney, A., Hassanein, H. M. & Aly, A. H. High-performance liquid sensor based one-dimensional phononic crystal with demultiplexing capability. Mater. Today Commun. 26, 102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102045 (2021).

Maldovan, M. Sound and heat revolutions in phononics. Nature 503, 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12608 (2013).

Pennec, Y., Vasseur, J. O., Djafari-Rouhani, B., Dobrzyński, L. & Deymier, P. A. Two-dimensional phononic crystals: examples and applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 65, 229–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfrep.2010.08.002 (2010).

Gu, T. et al. Induced transparency based subwavelength acoustic demultiplexers. J. Phys. D. 54, 175301. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/abe07c (2021).

Gharibi, H. & Bahrami, A. Phononic crystals for sensing fames with demultiplexed frequencies. J. Mol. Liq. 305, 112841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112841 (2020).

Antraoui, I., Khettabi, A., Sallah, M. & Zaky, Z. A. Analysis of the defect mode features in an asymmetric and symmetric acoustic system using expansion chambers. Sci. Rep. 15, 2546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85002-x (2025).

Malki, M. E., Khettabi, A., Sallah, M. & Zaky, Z. A. Noise filter using a periodic system of dual Helmholtz resonators. Sci. Rep. 14, 24987. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74799-2 (2024).

Malki, M. E. & Khettabi, A. Acoustic wave transmission through periodic parallel resonators, Materials Today: Proceedings, 72, 3786–3794, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.09.393 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Defected photonic crystal as propylene glycol THz sensor using parity-time symmetry. Sci. Rep. 14, 23209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73477-7 (2024).

Nayan, M. F. et al. High sensitivity One-Dimensional photonic crystal sensor design for waterborne bacteria detection. Sens. Imaging. 26, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11220-024-00532-y (2025).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Coupling between topological edge state and defect mode-based biosensor using phononic crystal. Sci. Rep. 15, 2216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85195-9 (2025).

Lin, Q. et al. The compact acoustic liquid sensor based on the circumferential modes of a cylindrical shell. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 304, 111843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2020.111843 (2020).

Lucklum, R., Mukhin, N., Djafari Rouhani, B. & Pennec, Y. Phononic crystal sensors: A new class of resonant sensors—Chances and challenges for the determination of liquid properties. Front. Mech. Eng. 7, 705194. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2021.705194 (2021).

Gharibi, H. & Mehaney, A. Two-dimensional phononic crystal sensor for volumetric detection of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in liquids. Phys. E: Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 126, 114429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2020.114429 (2021).

Gueddida, A. et al. Phononic crystal made of silicon ridges on a membrane for liquid sensing, Sensors, 23, 2023. (2080).

Almawgani, A. H. et al. Periodic and quasi-periodic one-dimensional phononic crystal biosensor: A comprehensive study for optimum sensor design. RSC Adv. 13, 11967–11981. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA01155K (2023).

Sayed, A. G. et al. Enhanced performance of fluidic phononic crystal sensors using different Quasi-Periodic crystals. Crystals 14, 925 (2024).

Zaky, Z. A., Mohaseb, M. & Aly, A. H. Detection of hazardous greenhouse gases and chemicals with topological edge state using periodically arranged cross-sections. Phys. Scr. 98, 065002 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Mohaseb, M., Hendy, A. S. & Aly, A. H. Design of phononic crystal using open resonators as harmful gases sensor. Sci. Rep. 13, 9346. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36216-y (2023).

Zaki, S. E. & Basyooni, M. A. Ultra-sensitive gas sensor based Fano resonance modes in periodic and fibonacci quasi-periodic Pt/PtS2 structures. Sci. Rep. 12, 9759 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Hendy, A. S., Badawy, W. M. & Aly, A. H. Periodic open and closed resonators as a biosensor using two computational methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 11943. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61987-3 (2024).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Sharma, A., Hendy, A. S. & Aly, A. H. Theoretical optimisation of a novel gas sensor using periodically closed resonators. Sci. Rep. 14, 2462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52851-5 (2024).

Malki, M. E., Pereira, N. & Lanceros-Mendez, S. Fano resonance in a defective network formed by Helmholtz resonators with extended necks, in International Conference on Digital Technologies and Applications, 308–319. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29860-8_32

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Acoustic metasurface constructed by periodic parallel Helmholtz resonators for gas sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 15, 24345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04253-4 (2025).

Zhang, Z., Yu, D., Liu, J., Hu, B. & Wen, J. Transmission and bandgap characteristics of a duct mounted with multiple hybrid Helmholtz resonators. Appl. Acoust. 183, 108266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2021.108266 (2021).

Papadakis, N. M. & Stavroulakis, G. E. FEM investigation of a Multi-Neck Helmholtz resonator. Appl. Sci. 13, 10610. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131910610 (2023).

Yang, L., Zhang, J., Xia, J., Zhang, S. & Yang, Y. Sound transmission loss of Helmholtz resonators with elastic bottom plate. Sound Vibration, 58(1), 056968 (2024).

Guo, R., Tang, W. & Zhu, W. Comparison of 1D transfer matrix method and finite element method with tests for acoustic performance of multi-chamber perforated resonator. Appl. Acoust. 112, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2016.05.018 (2016).

El Chami, Y., Pezeshki, Z., Mohamed, S. S. & Safaei, B. Enhanced acoustic Attenuation performance of a novel absorptive muffler: A Helmholtz equation-based simulation study. J. Eng. Manag Syst. Eng. 3, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.56578/jemse030105 (2024).

Antraoui, I. et al. Design of a parallel Helmholtz resonator structure as a hazardous greenhouse gases sensor using the transfer matrix method. Sci. Rep. 15, 25434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09872-5 (2025).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Selective filter using Thue–Morse structures by the finite element and transfer matrix methods. J. Comput. Electron. 24, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10825-025-02364-9 (2025).

Imanian, H., Noori, M. & Abbasiyan, A. Highly efficient gas sensor based on quasi-periodic phononic crystals. Sens. Actuators B. 345, 130418 (2021).

Zarifi, M. H. et al. Sensitivity enhancement in planar microwave active-resonator using metal organic framework for CO2 detection. Sens. Actuators B. 255, 1561–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.08.169 (2018).

Zarifi, M., Farsinezhad, S., Abdolrazzaghi, M., Daneshmand, M. & Shankar, K. Selective microwave sensors exploiting the interaction of analytes with trap states in TiO2 nanotube arrays, Nanoscale, 8, 7466–7473, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NR06567D

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. A. Zaky performed the simulations, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the main manuscript text, discussed the results and supervised this work. I. Antraoui analyzed the data, discussed the results, wrote and revised the main manuscript text. Ali Hennache analyzed the data, discussed the results, and revised the main manuscript text. M. El Malki analyzed the data, discussed the results, wrote and revised the main manuscript text. M. A. Zaky analyzed the data, discussed the results, and revised the main manuscript text. Ali Hennache analyzed the data, discussed the results, and revised the main manuscript text. M. Sallah analyzed the data and discussed the results. Finally, all Authors developed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies involving animals or human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaky, Z.A., Hennache, A., Antraoui, I. et al. Tunable sensing properties of a Helmholtz resonator array featuring a central defect cell with four lateral ducts. Sci Rep 15, 33316 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20363-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20363-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Tailoring Acoustic Waves with Aperiodic Phononic Crystals for Energy Localization

Journal of Vibration Engineering & Technologies (2026)

-

Acoustic multiple transmission peaks in Thue-Morse structures based on lateral resonators

Scientific Reports (2025)