Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurological disorder characterized by memory loss, language difficulties, and the loss of planning and coordination skills. Research done by neurologists suggest that the decline in acetylcholine and the accumulation of pathological forms of amyloid beta plaques produced by both the β- and γ-secretase enzymes in the brain as some of the primary causes of AD. Due to the multifactorial pathway associated with the progression of the disease, the inhibition of cholinesterase, β-secretase and other anti-inflammatory related enzymes have been reported as one of the major approaches in curbing the symptoms associated with it. Organic compounds containing the chalcone, sulfonyl, and allyl frameworks have been reported to possess cholinesterase, β-secretase, cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) inhibitory activities. As a result, we synthesized the allyl chalcones and their sulfonyl derivatives from commercially available 2,4-dihydroxyacetophenone, and evaluated them as potential anti-Alzheimer agents through in-vitro enzymatic assays as cholinesterase, β-secretase, LOX-5 and COX-2 inhibitors. Although, poor inhibitory effects were observed for the chalcone sulfonates against cholinesterase and β-secretase, derivatives 3c, 3e and 3 g exhibited significant inhibitory effects against these enzymes. With the exception of 3a, 3b and 3e with good COX-2 inhibitory activity, other derivatives showed poor anti-inflammatory activity. Enzyme kinetics complemented by molecular docking studies performed on 3e suggests a mixed mode of inhibition of the compound towards these enzymes. In our view, 3e with significant cholinesterase, cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase inhibitory activities could potentially serve as multi-target drug-lead candidate against AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

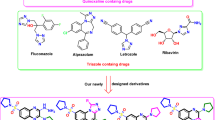

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia affecting the elderly. It is marked by cognitive challenges, such as memory loss and speech impairment1. The brain of patience with AD has been to contain β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, along with signs of oxidative damage2. Various molecular processes contribute to the development and advancement of AD, including decreased acetylcholine levels, deposition of Aβ, and oxidative stress2. Chronic inflammation is a key characteristic of AD, with neuroinflammation serving as a significant pathological hallmark and an early sign of the condition3. Current approaches to treating AD involve the use of cholinesterase inhibitors, along with strategies that also target Aβ peptides and metal-Aβ complexes4,5. A key factor influencing the therapeutic effectiveness of central nervous system medications is their ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier6. Due to the complex and multifactorial pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD, the use of cholinesterase inhibitors has shown to be insufficient in halting the progression of the disease7,8 The accumulation of Aβ is regarded as a critical factor in the progression of AD, as it results in the creation of neurofibrillary tangles and loss of synaptic connections2. Despite the advances in understanding the pathophysiology of AD, current treatments have limited efficacy in slowing the progression of the disease. A contemporary view supports the development of multi-targeted drugs that can address the multiple key pathophysiological processes linked to AD rather than single-targeted therapies9,10. These multi-targeted approaches may offer a more effective strategy for treating AD by targeting multiple biochemical pathways simultaneously. Chalcones, Sulfonyl and allyl containing organic compounds have been found to exhibit anti- Alzheimer properties through inhibiting cholinesterases (AChE and BChE), β-secretase, LOX (5/15) and COX-2, key enzymes involved in the pathogenesis of AD11,12,13 Chalcone A (Fig. 1), for example, was found to significantly inhibit AChE14. Sulfonyl-containing compound B, on the other hand, exhibited significant inhibitory activity against BChE15. Studies have shown the presence of ally functionality as potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, with compound C (Fig. 1) reported to cross the blood − brain barrier and inhibit AChE in the central nervous system16.

While each of these structural features has shown promise as inhibitors of cholinesterases (AChE and BChE), β-secretase, LOX (5/15) and COX 2, constructing a single molecule containing the chalcone, sulfonyl, and allyl frameworks may create a more potent inhibitor that targets multiple enzymes involved in the pathogenesis of AD. This approach could provide a more comprehensive treatment for AD. Based on these assumptions, we synthesized a series of novel 4-(allyloxy)-2-hydroxy-3-iodochalcones and their sulfonate derivatives as potential cholinesterases (AChE and BChE), β-secretase, LOX-5 and COX 2, inhibitors.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

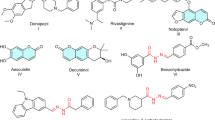

The mono-iodination of commercially available 2,4-dihydroxyacetophenone using a combination of potassium iodate and potassium iodide in ethanol-water mixture as solvent to afford 2,4-dihydroxy-3-iodoacetophenone has previously been reported17. The incorporation of the iodine atom is due to its ability to bind with the protein residue of the active sites of the enzymes. Due to the biological importance of the ally groups in organic compounds16, the prepared 2,4-dihydroxy-3-iodoacetophenone was treated with allyl bromide in the presence of potassium carbonate in acetone at 0 ˚C to afford the desired 1-(4-(allyloxy)-2-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)ethanone 1 (Fig. 2). The successful transformation was confirmed using a combination of spectroscopic techniques, such as 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, NOESY and COSY. Chalcones containing the methoxy and/or fluoro-substitution on the B ring have been found to possess significant cholinesterase inhibitory activity. This is presumably due to the non-covalent interactions of the electrons of the methoxy and fluoro groups with the protein residues of the active sites of the enzymes. As a result, compound 1 was subjected to Claisen-Schmidt aldol condensation with aromatic aldehydes (3-fluorobenzaldehyde and 4-methoxybenzaldehyde) to afford their corresponding chalcone derivatives (2a-b) (Fig. 2). The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra (Figure S1.1 and S1.2) of the prepared chalcones revealed additional signals in the aromatic region due to the incorporation of the phenyl ring. A set of doublets around 7.40–7.90 ppm with coupling constant values between 15.5 and 16.0 Hz in their 1H-NMR spectra confirmed the trans nature of the α,β-unsaturated framework. Due to biological impact of the sulfonyl moieties in organic compounds against inflammatory and cholinesterase activities15. The chalcone derivatives (2a-b) were treated with various sulfonyl chlorides in the presence of triethylamine to afford the novel chalcone sulfonates (3a-i) (Fig. 2) in good yields (Table 1). The incorporation of the sulfonyl group was confirmed by the absence of the broad singlet at around 11.01 ppm, found in the 1H-NMR spectra of the substrate, corresponding to the hydroxyl proton. The presence of additional peaks in the aromatic region was also observed in the proton and carbon spectra of compounds 3a-i (Figure S1.3– S1.11).

Biology

Evaluation against AChE, BChE and β-secretase

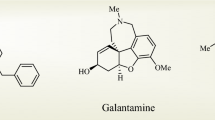

In this investigation, the potential for the allyloxy chalcones (2a-b) and their sulfonate derivatives (3a-i) as anti-Alzheimer agents was firstly explored through in-vitro enzymatic cholinesterase inhibitory assays against acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase using a modified Ellman’s assay procedure with donepezil as the reference standard. The obtained IC50 values (µM) represented in Table 2 revealed moderate to poor inhibitory activities of the prepared compounds against AChE and BChE, with the exception of compound 3e with significant inhibitory effect against these enzymes. The chalcone derivatives (2a–b) showed relatively moderate to poor cholinesterase inhibitory activities when compared to the reference standard, donepezil. The combination of the 3-fluorophenyl and/ or the 4-methoxybenzenesulfonate (3c) and 4-nitrobenzenesulfonate (3e) resulted in an increased inhibitory activity for these compounds against AChE with IC50 values of 10.2 µM and 8.5 µM, respectively, when compared to their chalcone precursors. The presence of the 4-fluorobenzenesulfonate group, on the other hand, resulted to a decrease in the inhibitory activity for 3b with IC50 values of 30.2 µM. The combination of the 4-methoxyphenyl and 4-fluorobenzenesulfonate groups on the molecular framework of 3 g also resulted in an enhanced AChE inhibitory activity (IC50 = 13.7 µM). Similar inhibitory trends for these chalcone sulfonate derivatives 3c, 3e and 3 g were observed towards the BChE with IC50 values of 14.5 µM, 8.3 µM and 11.3 µM, respectively. Compound 3i, with the 4-methoxyphenyl group and 2-nitrobenzenesulfonate also exhibited good inhibitory activity against BChE with an IC50 value of 14.2 µM. The presence of the fluorine atom and nitro group at the meta and ortho positions of the phenyl ring and benzenesulfonate framework, respectively, in 3d resulted in moderate cholinesterase inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 21.6 µM (AChE) and 16.7 µM (BChE). Poor cholinesterase inhibitory activities were observed for the rest of the compounds within the series. According to the amyloid theory, AD originates from the accumulation of pathological forms of Aβ produced by both the β- and γ-secretase enzymes in the brain. This accumulation is due to the distorted production and distribution of Aβ18. As a result, the BACE-1 inhibitory activity of the prepared compounds was evaluated using quercetin as a reference standard. Within the prepared compounds, the presence of the fluoro group at the meta position of the phenyl ring in compounds 3c and 3e resulted in a significant BACE-1 inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 21.6 µM and 15.3 µM, respectively. The significant effects of 3 h against BACE-1 (IC50 = 18.2 µM) may be due to the combination of the electron rich 4-methoxy group on both the phenyl ring and benzenesulfonate group. Other compounds showed lower inhibition activity against BACE-1. The significant inhibitory activities of compounds 3c and 3e against AChE, BChE and BACE-1 in our view make them dual inhibitors and potential drug candidates for curbing AD.

A current hypothesis suggests that inflammatory activity in the brain promotes AD by increasing the production of amyloid beta, killing healthy neurons, and ultimately reducing microglial cells’ ability to remove amyloid plaques19. The inhibition of LOX or COX have also been found to improve cognitive impairment via inhibiting the amyloid and tau pathology20. Chalcone and sulfone containing organic compounds have been reported to inhibit cyclooxygenase, an enzyme that promotes inflammation, by converting arachidonic acid into thromboxanes, prostaglandins, and prostacyclins21. Due to these literature findings, the prepared compounds were further evaluated as potential COX-2 and LOX-5 inhibitors with celecoxib and zileuton as reference standards, respectively.

Evaluation against COX-2 and LOX-5

The general inhibitory trend observed indicates that the prepared chalcones and their sulfonate derivatives are better COX-2 inhibitors compared to LOX-5 (Table 3). Chalcones (2a–b) exhibited poor inhibitory activities against both enzymes. The incorporation of the sulfonyl group resulted in a slight increase in the inhibitory property of some of the compounds (3a–i). The combination of the 3-fluorophenyl and/or methanesulfonate (3a), 4-fluorobenzenesulfonate (3b) and 4-nitrobenzenesulfonate (3e) resulted to a moderate COX-2 inhibitory activities for these compounds with IC50 values of 14.3 µM, 18.6 µM and 12.7 µM, respectively. Compounds 3b and 3e were also found to exhibit moderate inhibitory activities against LOX-5 with IC50 values of 27.2 µM and 28.0 µM, respectively. In our view, the dual cholinesterase, BACE-1, COX-2 and LOX-5 inhibitory activities exhibited by compound 3e, suggests it could serve as a multi-target-ligands (MTDLs) for curbing the symptoms associated with AD.

To investigate the mode of inhibition of the chalcone sulfonate derivatives, enzyme kinetic studies of the most active compound (3e) were conducted.

Enzyme kinetic studies of 3e against ache and BChE

A combination of the Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plots were used to determine the compound’s Michaelis constant (Km) and reaction velocity (Vmax) values as well as inhibition constant (Ki). These plots also indicate the type of inhibition exhibited by the compounds22.The cholinesterase (AChE and BChE) enzyme reaction was conducted and absorbance was recorded after every 1 s for 10 s at a wavelength of 412 nm. On the other hand, with the BACE-1 enzyme kinetic studies, fluorescence readings were recorded at excitation and emission of 545 nm and 590 nm, respectively, after every 1 s for 10 s. The enzyme kinetic studies on the most active compound 3e against AChE and BChE were evaluated at increasing inhibitor and substrate concentrations of (0, 2.5, 3.5 and 5 µM) and (0.1, 0.5, 2.5 and 5 mM), respectively. The Lineweaver–Burk plot of compound 3e against AChE revealed a decrease in the calculated Vmax values from 0.04 to 0.01 µMs-1 and a relatively constant Km value of 0.22 µM (Fig. 3 (a)). This trend is typical for a non-competitive mode of inhibition. The sets of intersecting straight lines above the x-axis on the Dixon plot with a Ki value of 2.6, on the other hand, is typical for a competitive mode of inhibition (Fig. 3 (b)). The results obtained from both graphs suggest the type of inhibition where the inhibitor can interact with the enzyme at either the active or a separate allosteric site23. A similar trend for this compound was observed in the Lineweaver–Burk plot against BChE with a decreasing Vmax values ranging from 0.014 to 0.007 µMs-1 and a constant Km value of 0.10 µM (Fig. 4 (a)). The Dixon plot, on the other hand, with intersecting lines just on the x-axis with Ki value of 5.7 ((Fig. 4 (b)), corroborates the non-competitive mode of inhibition observed from the Lineweaver–Burk plot for this compound against BChE.

To understand the interactions of the allyloxychalcones and their sulfonate derivatives with the protein binding sites, molecular docking studies of the most active compound, 3e, was performed into the active sites of AChE (PDB code 4EY7), BChE (1P0I) and β-secretase (1M4H).

In-silico cytotoxicity of compound 3e

Analysis for 3e using the ADMETlab 2.0 online tool24 indicates 3e falls within acceptable limits for all physicochemical properties except log D and log P values. These values represent the ability of the compound to enter the blood circulation as well as pass through membranes (Fig. 5). The absorption and distribution values are also all favorable for the compound other than it does seem to have the ability to inhibit P-Glycoproteins involved in drug clearance. It also does not bind plasma proteins within the blood which is a drug uptake and distribution option. The lower binding to plasma protein might balance the lower membrane permeability because if not bound more compound is available to attempt to pass through the membrane.

Diagram showing the physiochemical and cytotoxicity parameters for compound 3e. Molecular weight (MW), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (nHA), number of hydrogen bond donors (nHD), number of rotatable bonds (nRot), number of rings (nRing), number of atoms in the biggest ring (MaxRing), number of heteroatoms (nHet), formal charge (fChar), number of rigid bonds (nRig).

In terms of the computed toxicity parameters, compound 3e could be mutagenic displaying a poor score on the Ames test as well as carcinogenicity measures. The compound could also be allergic to the skin owing to the poor Ames test score on the skin sensitive rule. The nitro, sulphur and alkene groups in compound 3e were found to be the primary causes of the compound’s inability to pass both the Carcinogenicity Rule and skin sensitive rules.

Molecular docking studies

Docking of 3e into cholinesterase enzyme (AChE and BChE) binding sites.

The structures of AChE (PDB code: 4EY7) and BChE (PDB code: 1P0I), were selected due to their high resolutions (2.35 Å and 2.00 Å, respectively). The AChE structure was also crystallized with donepezil and therefore docking was conducted with donepezil to confirm parameters to use for docking 3e (Fig. 6 (a and b). In the docking pose of compound 3e with AChE (Fig. 7(a)), the 3-fluorophenyl group was involved in π-π stacking and π-π T-shaped interactions with the protein residues Tyr341 and Trp 86, respectively, as well as a π-cation interaction with His447 of the catalytic active site (CAS). Besides the π-π stacking between the benzene group and Tyr341, π-π T-shaped interactions were also noticed between the benzene group and the protein residue Trp86. Similar interactions with Tyr341 have been shown to stabilize the AChE-inhibitor complexes25. The docking pose of 3e showed the presence of a strong hydrogen bonding interaction between the oxygen atoms of the nitro group and the protein residue Gly126. The sulphur atom and the phenyl ring of the 4-nitrobenzenesulfonate group, interacts with the protein residue Tyr124 via the electrostatic π-sulphur and π-π T shaped interactions, respectively. The fluorine atom of the 3-fluorophenyl group is predicted to be involved in a very strong hydrogen bonding interaction with Gly121 and Gly122. The top docking pose of compound 3e into the active site of BChE (Fig. 7(b)) revealed no π-π stacking and π-π T-shaped interactions. However, the fluorine and oxygen atoms of the 3-fluorophenyl and nitro groups are involved in a very strong hydrogen bonding interactions with the Asn289 and Trp82 protein residues, respectively. The 3-fluorophenyl group was also involved in halogen bond interaction with Ser287 protein residue. Interactions with Trp82 are key for the design of inhibitors to BChE26. These observed interactions of 3e presumably account for this compound’s increased inhibitory effect against these enzymes, as well as observed mixed-mode of inhibition.

Docking of 3e into β-secretase binding sites.

The inhibitor co-crystallized with β-secretase was used as a reference standard in for the docking of compound 3e, into the active site of β-secretase (PDB code: 1M4H), (Fig. 8). Several hydrogen bonds form between the inhibitor and various residues of the protein (Fig. 8(a)). The compound 3e showed only two hydrogen bonds between the oxygen atoms of the nitro group and Arg235 and Asn233, however, π-anion and halogen interactions were observed on the benzene group and fluorine atom with Asp228 and Gly11 protein residues, respectively (Fig. 8(b)). The number of halogen and hydrogen bonds is lower for 3e than the co-crystallized ligand but some similar residues are involved in the few bonds observed which could provide a reason for inhibitory activity of 3e against this enzyme.

Conclusions

Although the prepared chalcone derivatives exhibited poor inhibitory effect against LOX-5, COX-2 and BACE-1 activity when compared to the reference standards, moderate cholinesterase (AChE and BChE) inhibitory activity was observed for the compounds. The replacement of the 2-hydroxyl group with sulfonyl chloride derivatives resulted in significant inhibitory effects for the chalcone sulfonates 3c, 3e and 3 g against AChE and BChE. Moderate to significant inhibitory effects were observed for 3c and 3e against BACE-1 activity, respectively. Generally, the prepared compounds revealed poor to moderate anti-inflammatory activity. However, chalcone sulfonate derivatives (3a, 3b, 3e) and (3b, 3c, 3e) exhibited significant activity against COX-2 and LOX-5, respectively. The molecular docking studies showed that these compounds bind mainly at the allosteric sites, explaining their non-competitive mode of inhibition towards these enzymes. The most active compound 3e with dual cholinesterase as well as cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase inhibitory activities could potentially serve as multi-target drug-lead candidate against AD.

Experimental

General

All the commercially available reagents and solvents were purchased from Merck and Sigma Aldrich and were used without further purification unless stated otherwise. Flash column chromatography was carried out on silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh). All reagents were measured at room temperature. The structural properties of compounds were recorded and confirmed by: Melting points were obtained using Lasec/SA-melting point apparatus from Lasec company, SA (Johannesburg, South Africa); Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) (Bruker Avance 400 MHz Topspin 3.2) and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) (Sciex X500R QTOF); Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. All chemical shifts are expressed in part per million (ppm) abbreviated as δ, with respect to tetramethylsilane as an internal standard of the 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra, CDCl3 (1H-NMR = 7.25 ppm and 13 C-NMR = 77.0 ppm). The 1H-NMR spectra were reported as follows: δ (number of protons, multiplicity, coupling constant J, and position of proton). The multiplicity are expressed by s = singlet, d = doublets, t = triplets, dd = doublet of doublets, m = multiplets and brs = broad singlet.

Typical procedure for the synthesis of compounds 2a–b

A mixture of 1 (1 equiv.) and benzaldehyde derivative (1.2 equiv.) in the presence of 5% KOH (5 mL) in ethanol (30 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The reaction mixture was poured into crushed ice, and acidified with concentrated HCl. The precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethanol to afford compounds 2a–b.

(E)-1-(4-(allyloxy)-2-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)-3-(2-chlorophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (2a)

Yellow solid (2.3 g, 85%), mp. 187–188 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 4.67 (2H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.30 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.48 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.96–6.03 (1H, m), 6.40 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.07 (1H, t, J = 2.8 Hz), 7.27–7.34 (3H, m), 7.48 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.80 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.84 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 14.08 (-OH, s); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 29.7, 70.0, 103.7, 114.6 (d, 2JCF = 22.0 Hz), 114.9, 114.7 (d, 2JCF = 22.0 Hz), 118.3, 120.9, 124.8 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 130.6 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 131.6 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 136.8, 136.9, 144.0 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 163.2 (d, 1JCF = 245 Hz), 163.8, 164.8, 191.3; δC (100 MHz, CDCl3); HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 423.9972: C18H14FIO3; found 423.9976.

(E)-1-(4-(allyloxy)-2-hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (2b)

Yellow solid (0.90 g, 77%), mp. 139–141 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.80 (3 H, s), 4.65 (2 H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.28 (1 H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.47 (1 H, d, J = 17.2), 5.96–6.03 (1 H, m), 6.38 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 6.87 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.37 (1 H, d, J = 15.2 Hz), 7.54 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.83 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.62 (1 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 55.5, 69.9, 77.3, 103.5, 114.6, 115.0, 117.1, 118.2, 127.4, 130.6, 131.4, 131.8, 145.4, 162.1, 163.4, 164.7, 191.6; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 436.0172: C19H17IO4; found 436.0175.

Typical procedure for the synthesis of compounds 3a–j

A solution of 2 (1 equiv.) in dichloromethane (5 mL) at 0 °C in the presence of triethylamine (1.2 equiv.) was treated with various sulfonyl chlorides (1.2 equiv.). The ice-bath was removed and the mixture stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with an ice-cold water (50 mL), and the precipitate was filtered and purified by silica gel column chromatography to obtained compounds 3a–j.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-6-(3-(3-fluorophenyl)acryloyl)-2-iodophenyl methanesulfonate (3a)

White solid (0.08 g, 65%), mp. 133–135 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.23 (3H, s), 4.63 (2H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.30 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.48 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.96–6.03 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.83 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.86 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.00 (2H, t, J = 2 Hz), 7.37 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.62 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.74 (2H, dd, J = 2 Hz and 8 Hz) ; δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 40.7, 70.4, 86.3, 110.2, 114.6 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 117.5 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 118.6, 124.6 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 126.4, 128.5, 130.5 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 131.5, 131.8, 137.0, 136.9 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 143.5 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 161.3, 163.2 (d, 1JCF = 252 Hz), 189.4; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 501.9747: C19H16FIO5S; found 501.9750.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-6-(3-(3-fluorophenyl)acryloyl)-2-iodophenyl 4-fluorobenzenesulfonate (3b)

White solid (0.1 g, 73%), mp. 115–117 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 4.60 (2H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.29 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.45 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.93–6.03 (1H, m), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.00-7.10 (3H, m), 7.25 (2H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.28–7.32 (2H, m), 7.43 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.66 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.76 (2H, dd, J = 2 Hz and 8 Hz) ; δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 29.7, 70.4, 86.5, 110.4, 114.5 (d, 2JCF = 22.0 Hz), 116.7 (d, 2JCF = 23.0 Hz), 117.4 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 118.5, 124.6 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 126.1, 128.8, 130.5 (d, 3JCF = 9.0 Hz), 131.5, 131.9 (d, 4JCF = 4.0 Hz), 132.0 (d, 3JCF = 10.0 Hz), 132.1, 136.9 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 142.5 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 149.0, 161.4, 163.3 (d, 1JCF = 252 Hz), 164.0 (d, 1JCF = 252 Hz), 188.4; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 581.9809: C24H17F2IO5S; found 581.9813.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-6-(3-(3-fluorophenyl)acryloyl)-2-iodophenyl 4-methoxybenzenesulfonate (3c)

White solid (0.09 g, 70%), mp. 124–125 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.87 (3H, s), 4.61 (2H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.30 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.48 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.93–6.02 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.77 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.00-7.05 (2H, m), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.19–7.27 (2H, m), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.35 (2H, dd, J = 2 Hz and 8 Hz) ; δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 55.7, 70.3, 86.9, 110.3, 114.5, 114.6 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 117.2 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 118.4, 124.6 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 126.2, 127.2, 128.8, 130.4 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 131.3, 131.6, 132.1, 137.0 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 142.0 (d, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 149.2, 161.4, 163.15 (d, 1JCF = 246 Hz), 164.7, 188.4; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 594.0009: C25H20FIO6S; found 594.0012.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-6-(3-(2-fluorophenyl)acryloyl)-2-iodophenyl 2-nitrobenzenesulfonate (3d)

White solid (0.11 g, 76%), mp. 118–120 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 4.63 (2H, d, J = 4.0 Hz), 5.29 (1H, d, J = 10.8 Hz), 5.46 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.94–6.03 (1H, m), 6.77 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.02–7.10 (1H, m), 7.12–7.23 (2H, m), 7.26–7.30 (3H, m), 7.52 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.60–7.62 (2H, m), 7.66 (1H, t, J = 1.2 Hz), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 70.4, 86.7, 110.6, 115.0 (d, 2JCF = 22.0 Hz), 117.6 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 118.5, 124.5 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 125.0, 125.7, 128.6, 130.4, 130.5 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 131.4, 132.0, 132.1, 132.5, 135.5, 136.5 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 142.8, 148.4, 149.8, 161.6, 163.2 (d, 1JCF = 246 Hz), 188.6; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 608.9754: C24H17FINO7S; found 608.9758.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-6-(3-(2-fluorophenyl)acryloyl)-2-iodophenyl 4-nitrobenzenesulfonate (3e)

White solid (0.12 g, 80%), mp. 125–126 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 4.63 (2H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.30 (1H, d, J = 10.8 Hz), 5.45 (1H, d, J = 17.2), 5.93–6.02 (1H, m), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.00 (1H, d, J = 15.6), 7.06 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.15 (1H, d, J = 9.6 Hz), 7.22 (1H, h, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.30 (1H, dd, J = 2.0 Hz and 8.0 Hz), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.66 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.97 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.19 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 70.5, 86.2, 110.6, 114.4 (d, 2JCF = 22.0 Hz), 117.7 (d, 2JCF = 21.0 Hz), 124.4, 124.6 (d, 4JCF = 3.0 Hz), 125.8, 128.6, 130.4, 130.7 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 131.3, 132.2, 136.6 (d, 3JCF = 8.0 Hz), 141.6, 143.0, 148.7, 151.2, 161.5, 162.2 (d, 1JCF = 246 Hz), 188.4; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 608.9754: C24H17FINO7S; found 608.9760.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-2-iodo-6-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acryloyl)phenyl methanesulfonate (3f)

Yellow solid (0.90 g, 77%), mp. 139–141 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.23 (3 H, s), 3.78 (3 H, s), 4.63 (2 H, d, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.30 (1 H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.48 (1 H, d, J = 17.2), 5.96–6.03 (1 H, m), 6.74 (1 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.83 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.86 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.00 (2 H, t, J = 2 Hz), 7.37 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.42 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.62 (1 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.74 (2 H, dd, J = 2 Hz and 8 Hz) ; δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 40.6, 55.5, 70.4, 86.5, 110.1, 114.5, 118.5, 123.0, 127.3, 128.9, 130.5, 131.6, 145.3, 148.5, 161.0, 189.9; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 513.9947: C20H19IO6S; found 513.9952.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-2-iodo-6-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acryloyl)phenyl 4-fluorobenzenesulfonate (3 g)

Yellow solid (0.11 g, 81%), mp. 137–138 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.78 (3 H, s), 4.60 (2H, d, J = 4.4 Hz), 5.29 (1H, d, J = 9.6 Hz), 5.47 (1H, d, J = 16.0), 5.93–6.01 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 6.86 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.00 (2H, t, J = 2 Hz), 7.35 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.41 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.62 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.74 (2H, dd, J = 2 Hz and 8 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 42.0, 55.5, 70.4, 86.6, 110.4, 114.5, 116.7 (d, 2JCF = 23.0 Hz), 118.4, 122.7, 127.3, 129.1, 130.4, 131.6, 131.8, 131.9, 132.0, 143.9, 148.9, 161.2, 161.8, 164.5 (d, 1JCF = 266 Hz), 188.7; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 594.0009: C25H20FIO6S; found 594.0012.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-2-iodo-6-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acryloyl)phenyl 4-methoxybenzenesulfonate (3 h)

Yellow solid (0.11 g, 82%), mp. 143–145 °C; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.81 (3 H, s), 3.88 (3 H, s), 4.70 (2 H, d, J = 4.2 Hz), 5.35 (1 H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.56 (1 H, d, J = 17.1), 6.03–6.12 (1 H, m), 6.82 (3 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.93 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.95 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.45 (1 H, d, J = 16.0 Hz), 7.50 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.71 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.74 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 55.5, 55.7, 70.3, 87.1, 110.2, 114.4, 114.5, 118.3, 122.8, 127.3, 127.5, 129.2, 130.3, 131.2, 131.6, 132.0, 143.5, 149.2, 161.2, 161.7, 164.5, 188.7; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 606.0209: C26H23IO7S; found 606.0213.

(E)-3-(allyloxy)-2-iodo-6-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acryloyl)phenyl 2-nitrobenzenesulfonate (3i)

????? solid (0.09 g, 69%), mp. 126–127 °C; νmax (ATR) cm− 1; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.78 (3 H, s), 4.62 (2 H, d, J = 4.2 Hz), 5.30 (1 H, d, J = 10.4 Hz), 5.47 (1 H, d, J = 17.1), 6.00-6.03 (1 H, m), 6.76 (1 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.81 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.93 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.30 (1 H, d, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.36 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.43 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.56–7.60 (3 H, m), 7.62 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz); δC (100 MHz, CDCl3) 29.7, 55.5, 110.6, 114.4, 118.5, 122.2, 125.1, 126.9, 129.0, 130.5, 130.6, 131.5, 131.8, 132.1, 132.5, 135.3, 144.0, 148.3, 150.0, 161.3, 162.0, 188.7; HRMS (ES+): m/z [M + H]+ calc for 620.9954: C25H20INO8S; found 620.9957.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory assay

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitory assay was performed following the procedure by the manufacturer as outlined in the kit (Item No. AB138871; Abcam). Stock solution of 20 µM in DMSO, which was further diluted to the final assay concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 5.0 and 10 µM using Tris buffer (50 mM; pH 7.7). In each well of the 96-well plate, 9.0 µL of the test compounds and 1.0 µL acetylcholinesterase (0.04 mg/mL) () was added and the mixture incubated for 15 min. 70 µL of Tris buffer was then added to each well and was further incubated for 10 min. 10 µL solution DTNB and acetylcholine iodide (3 mM and 5 mM, respectively, in Tris buffer, 50 mM, pH 7.7) was used to start the reaction. The absorbance readings was recorded for each run at a wavelength of 412 nm using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States) and the IC50 and standard deviation values were determined using the Graph Pad Prism.

Butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory assay

The butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory assay was performed following the procedure by the manufacturer as outlined in the kit (Item No. AB241010; Abcam). Stock solution of 20 µM in DMSO, which was further diluted to the final assay concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 5.0 and 10 µM using Tris buffer (50 mM; pH 7.7). In each well of the 96-well plate, 9.0 µL of the test compounds and butyrylcholinesterase (0.02 mg/mL) was added and the mixture incubated for 15 min. 70 µL of Tris buffer was then added to each well and was further incubated for 10 min. 10 µL solution DTNB and butyrylcholine iodide (3 mM and 5 mM, respectively, in Tris buffer, 50 mM, pH 7.7) was used to start the reaction. The absorbance readings was recorded for each run at a wavelength of 412 nm using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States) and the IC50 and standard deviation values were determined using the Graph Pad Prism.

5 β-Secretase (BACE-1) inhibitory assay

The β-Secretase inhibitory assay was performed following the procedure by the manufacturer as outlined in the kit (Item No. AB133072; Abcam). Stock solutions of the test compounds (20 µM) and quercetin were prepared in DMSO and further diluted to 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 5.0 and 10 µM with sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.5). 10 µL of the test compounds as well as quercetin and 2.0 µL human recombinant BACE-1 (1.0 U/mL) was added to each well and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Afterwards, 10 µL of substrate was added to each well and the reaction was further incubated for 60 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensity produced by the hydrolyzed substrate was recorded with an excitation and emission wavelengths of 545 nm and 590 nm, respectively, using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States).

Cyclooxygenase (COX-2) inhibitory assay

The cyclooxygenase (COX-2) assays were performed in duplicate using 96-well plates following the procedure by the manufacturer as outlined in the kit (Item No. K 547; Bio Vision). The prepared stock solutions of the test compounds in DMSO (20 µM) were diluted using a Tris buffer (50 Mm, pH 7.7) to obtain the final assay concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 5.0 and 10 µM. 10 µL of the test compounds and 80 µL of the reaction mixture (a mixture of 76 µL COX assay buffer, 1 µL of COX probe, 2 µL of diluted COX cofactor and 1 µL of COX-2 enzyme) were incubated for 5 min. Afterwards, 10 µL of diluted arachidonic acid (in assay buffer) and 90 µL of aqueous sodium hydroxide solution was added to each well to initiate the reaction. The absorbance readings was recorded for each run at a wavelength of 430 nm using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States) and the IC50 and standard deviation values were determined using the Graph Pad Prism.

Human lipoxygenase (LOX-5) inhibitory assay

The lipoxygenase (LOX-5) assays were performed in duplicate using a 96-well plate following the procedure by the manufacturer as outlined in the kit (Item No. K 980; BioVision). 20 µM stock solution of the test compounds and standard in DMSO were further diluted in 50 mM Tris buffer of pH 7.7 to obtain concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 5.0 and 10 µM. Each well on a plate was filled with 2 µL test compound, 38 µL of LOX assay buffer and 40 µL of the reaction mixture (36 µL of LOX assay buffer, 2 µL of LOX probe, and 2 µL of LOX-5 enzyme) was incubated for 5 min at room temperature. 20 µL of LOX substrate solution was then added to each well to initiate the reaction. The absorbance readings was recorded for each run at a wavelength of 234 nm using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States) and the IC50 and standard deviation values were determined using the Graph Pad Prism.

Enzymes kinetic studies against ache and BChE

The enzyme studies were conducted in triplicate using a 96-well plate. Both the stock solutions of the test compounds and substrate in DMSO were diluted further in Tris buffer (50 Mm, pH 7.7) to obtain final concentrations of 0, 2.5, 3.5 and 5 µM, and 0.1, 0.5, 2.5 and 5 mM, respectively. To each well were added, 9.0 µL of the test compound (10, 25, 50, and 100 µM), 1.0 µL of the respective enzyme (AChE (0.04 mg/mL) and BChE (0.02 mg/mL)), and 70 µL of Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 7.7). The assay mixture was incubated for 30 and then 10 µL of DTNB (3 mM in Tris buffer, 50 mM, pH 7.7) and 10 µL of AChI/ or BChI (5 mM in Tris buffer, 50 mM, pH 7.7) were added sequentially to each well. The absorbances were measured after every 1 s for 10 s at a wavelength of 412 nm using a micro plate spectrophotometer reader (Accuris smart reader 96, Edison, New Jersey, United States).

Molecular docking

The binding site with x, y, and z coordinates of 9.919, -59.4524, -24.4327 with a radius of 11 was selected for PDB structure code 4EY7 representing AChE. Docking was conducted using the CDOCKER protocol with default settings following the preparation of donepezil with the prepare ligands protocol also with default settings in Discovery Studio software version 22.1.100.22290 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA).28 Compound 3e was drawn and then prepared using the prepare ligands protocol and docked using the CDOCKER protocol. The top 5–7 poses with the optimal CDOCKER and CDOCKER interaction energy were then subjected to binding energy calculations. Binding energies were calculated by allowing the binding site atoms to flex and introducing the Generalized Born with Molecular Volume solvent model. The pose with the best binding energy and no unfavourable interactions was represented. Similarly, the PDB code 1P0I structure representing BChE was prepared and the binding site x, y, z coordinates of 133.448, 114.713, 40.5365 with a radius of 12 was selected. Prepared compound 3e as well as donepezil were docked and binding energies were calculated the best binding energy and no unfavourable interactions were represented. For the PDB code 1M4H representing Beta-Secretase, the compound co-crystalised with the structure, as well as compound 3e were prepared, and docked similarly to the PDB codes above the binding site coordinates were 20.3192, 30.7692, 23.6911 with a radius of 15.8.

In-silico cytotoxicity methodology

Compound drawn in discovery studio was saved as a SMILES file, the detail was then entered into the ADMETab2.0 online tool (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) on the 4 October 2024.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Na Chiangmai, N. Spontaneous speech analysis for detecting mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease in Thai older adults. : 1–236. (2023).

Sehar, U., Rawat, P., Reddy, A. P., Kopel, J. & Reddy, P. H. Amyloid beta in aging and alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (21), 12924 (2022).

Thakur, S., Dhapola, R., Sarma, P., Medhi, B. & Reddy, D. H. Neuroinflammation in alzheimer’s disease: current progress in molecular signaling and therapeutics. Inflamm 46 (1), 1–17 (2023).

Yoo, J., Lee, J., Ahn, B., Han, J. & Lim, M. H. Multi-target-directed therapeutic strategies for alzheimer’s disease: controlling amyloid-β aggregation, metal ion homeostasis, and enzyme Inhibition. Chem. Sci. 16 (5), 2105–2135 (2025).

Singh, K., Kaur, A., Goyal, B. & Goyal, D. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of peptides for synergistic treatment of alzheimer’s disease by targeting Aβ Aggregation, Metal-Mediated Aβ Aggregation, Cholinesterase, Tau Degradation, and oxidative stress. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 15 (14), 2545–2564 (2024).

Sousa, J. A. et al. Reconsidering the role of blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease: From delivery to target. Front. aging neurosci, 1102809. (2023).

Kumar, V. & Roy, K. Recent progress in the treatment strategies for alzheimer’s disease. Computational Model. Drugs against Alzheimer’s Disease, 3–47. (2023).

Monteiro, A. R., Barbosa, D. J., Remião, F. & Silva, R. Alzheimer’s disease: insights and new prospects in disease pathophysiology, biomarkers and disease-modifying drugs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 211, 115522 (2023).

Noor, F. et al. Network Pharmacology approach for medicinal plants: review and assessment. Pharm 15 (5), 572 (2022).

Thai, K. M. et al. Recent advances in computational modeling of Multi-targeting inhibitors as Anti-Alzheimer agents. Computational Model. Drugs against Alzheimer’s Disease, 231–277 (2023).

Antoniolli, G., Almeida, W. P., Frias, C. C. & de Oliveira, T. B. Chalcones acting as inhibitors of Cholinesterases, β-Secretase and β-Amyloid aggregation and other targets for alzheimer’s disease: A critical review. Curr. Med. Chem. 28 (21), 4259–4282 (2021).

Akocak, S., Boga, M., Lolak, N., Tuneg, M. & Sanku, R. K. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of 1, 3-diaryltriazenesubstituted sulfonamides as antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. JOTCSA 6 (1), 63–70 (2019).

Chowdhury, S. & Kumar, S. Inhibition of BACE1, MAO-B, cholinesterase enzymes, and anti‐amyloidogenic potential of selected natural phytoconstituents: Multi‐target‐directed ligand approach. J. Food Biochem. 45 (1), 13571 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Recent advance on pleiotropic cholinesterase inhibitors bearing amyloid modulation efficacy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 242, 114695 (2022).

Makhaeva, G. F. et al. New hybrids of 4-amino-2, 3-polymethylene-quinoline and p-tolylsulfonamide as dual inhibitors of acetyl-and butyrylcholinesterase and potential multifunctional agents for alzheimer’s disease treatment. Mol 25 (17), 3915 (2020).

Sharma, A., Nuthakki, V. K., Gairola, S., Singh, B. & Bharate, S. B. A Coumarin – Donepezil hybrid as a Blood – Brain barrier permeable dual cholinesterase inhibitor: Isolation, synthetic Modifications, and biological evaluation of natural coumarins. ChemMedChem 17 (18), 202200300 (2022).

Mphahlele, M. J., Agbo, E. N., Gildenhuys, S. & Setshedi Exploring, I. B. Biological activity of 4-Oxo-4H-furo[2,3-h]chromene derivatives as potential Multi-Target-Directed ligands inhibiting Cholinesterases, β-Secretase, Cyclooxygenase-2, and Lipoxygenase-5/15, biomolecules. 9 (11), 736. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110736

Hardy, J. & Selkoe, D. J. The amyloid hypothesis of alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356 (2002).

Shadfar, S., Hwang, C. J., Lim, M. S., Choi, D. Y. & Hong, J. T. Involvement of inflammation in alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory agents. Arch Pharm Res. 38, 2106–2119 (2015).

Moussa, N. & Dayoub, N. Exploring the role of COX-2 in alzheimer’s disease: potential therapeutic implications of COX-2 inhibitors. Saudi Pharm. J. 31 (9), 101729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101729 (2023).

Kontogiorgis, C. A. & Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Biological evaluation of several coumarin derivatives designed as possible anti-inflammatory/antioxidant agents. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 18, 63–69 (2003).

Wang, B. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of novel Rutaecarpine derivatives and related alkaloids derivatives as selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 1415–1423 (2010).

Pesaresi, A. Mixed and non-competitive enzyme inhibition: underlying mechanisms and mechanistic irrelevance of the formal two-site model. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 38 (1), 2245168. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2023.2245168 (2023).

Guoli, X. et al. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res, 49 (2021).

Kurt, B. Z. et al. Synthesis, anticholinesterase activity and molecular modeling study of novel carbamate-substituted thymol/carvacrol derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 25, 1352–1363 (2017).

Correa-Basurto, J. et al. QSAR, docking, dynamic simulation and quantum mechanics studies to explore the recognition properties of cholinesterase binding sites. Chem. Biol. Interact. 209, 1–13 (2014).

Discovery Studio software. version 22.1.100.22290 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA) to BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, Discovery Studio, version 22.1.100.22290, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes, (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Ms L. Raphoko for her assistance with running the mass spectrometry for the prepared compounds.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support on this project from the University of Limpopo (UL) and the National Research Foundation (South Africa) through grant number 129370.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.W, T.C.L and E.N.A: Conceptualize and design of the project E.N.A and K.B.M: Synthesis, purification and characterization E.N.A and S.G: Biological assaysS.G: Computational studiesAll authors: Wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agbo, E.N., Maluleke, B.K., Gildenhuys, S. et al. Biological evaluation and molecular Docking studies of the prepared chalcone derivatives as potential anti-Alzheimer agents. Sci Rep 15, 36575 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20390-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20390-2