Abstract

Drugs, chemical compounds, and other elements are often delivered to the ears of experimental animals to manipulate cochlear function, study how the ear works, identify drugs that prevent hearing loss, and test for ototoxicity. Delivery procedures for acute studies have been described in the literature. However, detailed information on methods that allow weeks of continuous drug delivery to the mouse cochleae is sparse. This paper describes a method for chronic drug delivery to the mouse cochlea. We illustrate the steps for the surgical implantation of an ALZET infusion pump and the placement of its catheter. We propose a ventral approach to the cochlea, using a surgical laser to make the cochleostomy and the placement of the pumps’ delivery ports into scala tympani with an orientation toward the cochlear apex. The catheter’s orientation toward the cochlear base often affects the vestibular system and is not favored for placement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The murine animal model has become the gold standard for many basic science experiments and drug studies addressing hearing impairment, hearing loss, and hearing protection. During the experiments, drugs and chemical compounds are delivered to the cochleae of experimental animals to study normal function, ototoxicity, and the potential for treating noise-induced hearing loss. Several research groups have presented methods for direct cochlear drug delivery1,2. The published techniques include transtympanic drug injection into the middle ear3,4,5,6,7,8,9, sponges or gels placed on the round window10,11,12,13, microinjection through the round window14, nano-carriers15,16,17,18, and direct delivery of drugs with pumps into the cochlea14,19,20,21,22,23. Recently, Kim and Ricci surgically exposed mouse cochleae and applied phosphoric acid gel to create a window in the cochlear wall that permits the imaging of cochlear cells in hearing animals24 and provides access to place a catheter for drug delivery. Among the methods, direct drug injection into scala tympani provides a well-controllable approach for cochlear drug delivery14,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. While previous papers describe the technique of implanting an osmotic pump to deliver the chemical compounds21,22, careful evaluation of the published methods shows that only in larger animals, such as gerbils or guinea pigs, implanted osmotic pumps delivered drugs for weeks. Only a few publications are available on intracochlear drug delivery in mice14,33. Examples are Chen and coworkers, who delivered the drugs in less than three hours33. Jero and coworkers compared different methods for drug delivery to the inner ear14. They showed that transtympanic injection, sponges placed on the round window, and direct cochlear injection with an osmotic pump could deliver the drugs14. For the direct drug infusion into the cochlea, no timeline was provided for the infusion. However, all animals were sacrificed after 72 hours14.

To deliver drugs directly into the mouse cochlea for up to four weeks, we implanted an ALZET micro-osmotic pump34. The study aimed to demonstrate that fluvastatin, when injected four weeks into the right cochlea, can protect noise-induced hearing loss in the left ear34. The surgery is a modification of the approach reported by Jero et al. (2001) but uses a surgical carbon dioxide (CO2) laser to make the bullostomy and cochleostomy. The cochleostomy was rostral, as close as possible to the stapedial artery and the middle ear’s medial wall. This approach also allowed us to select the placement of the pump catheter into scala vestibuli by moving the cochleostomy site toward the cochlear base. With the chosen cochlear access, the catheter orifice and subsequent direction of the drug flow could be oriented either toward the cochlear base, including the vestibular system, or the cochlear apex.

Methods and results

Ethical statement

The animal experiments described below complied with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. Care and use of the animals followed the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals guidelines35. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northwestern University (IS00008596 and IS00008707) and by the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED).

Animals

Ten-week-old CBA/CaJ male mice (stock number 000654) were shipped from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) to the Center for Comparative Medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. The mice were acclimated for one week in the facility before surgery. Three animals were housed together in an autoclaved, individually ventilated cage, with wood shavings and cotton pads for the nest and hiding place building. The light cycle was 14 h, followed by 10 h of dark. The lights were “on” at 6 am and “off” at 8 pm. Water and Teklad (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) LM-485 Mouse/Rat sterilizable diet pellets were given ad libitum. Post-surgery, mice were individually housed to prevent chewing and scratching at the sutures.

Osmotic pump implantation

The osmotic pumps

ALZET micro-osmotic pumps (Model 1004, Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) were purchased from Braintree Scientific (Braintree, MA). According to their specification sheet, the pumps deliver fluids over four weeks at a 0.11 µL/hour flow rate. The numbers were not verified experimentally during our experiments. Forty-five mice were implanted in this study, one pump per animal. No change in pumps occurred during the duration of the drug delivery. For the time after the implantation, we had little control over the volume of fluids delivered. The decision about whether the drug of interest was delivered to the cochlea was made by the location of the catheter tip at the conclusion of the study. In only one case, the tip of the catheter was outside the cochlea.

The catheter for the osmotic pump

The catheter inserted into the cochlea was custom-fabricated to reduce the tubing diameter from 1 mm at the port of the osmotic pump to 130 μm, where it enters the cochlea. Supplemental Fig. 1 shows the fabrication steps (Supplemental Table 1 lists the materials and sources). A 2 cm long segment of polyimide tubing (Micolumen, Oldsmar, FL), 130 μm outer and 100 μm inner diameter, was inserted into the Tygon ND100-65 tubing (Saint Gobain Performance Plastic, Akron, OH), 840 μm inner diameter. The connection was sealed with SILASTIC MDX4-4210 medical-grade elastomer mixed with its curing agent (Dow Corning, Midland, MI). The fabricated catheters were then placed in an oven for overnight polymerization to form the silicone rubber at 50 °C (Supplemental Fig. 1). Before sterilization, the quality of each catheter was individually tested (Supplemental Fig. 1). The catheter length was adjusted for proper pump placement before inserting it into the cochlea and fixation with methyl methacrylate acrylic.

Materials required and preparation of the surgery

Before the surgery, all instruments (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2) were autoclaved. Catheters that connect the osmotic pump and the cochlea were sterilized using ethylene oxide gas (Supplemental Table 3). We also gathered the materials required for anesthesia (Supplemental Table 4) and collected the disposable and miscellaneous items (Supplemental Table 5) for the surgery.

The surgical team

A two-person team was optimal for the procedure, with one person trained in performing surgeries. The second, a support person, was responsible for inducing the anesthesia, mounting the mouse in the head holder, shaving and cleaning the surgical field, keeping medical records, monitoring and adjusting the anesthesia, and supervising the animal’s recovery after surgery.

Animal anesthesia

For pain management, we injected a subcutaneous dose of 0.05 mg/kg immediate-release buprenorphine analgesic36,37 at least an hour before the induction of the anesthesia, followed thirty minutes later by an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mL of 0.9% NaCl United States Pharmacopeia (USP) solution for hydration. The anesthesia was induced with 3% of the inhalation anesthetic isoflurane in 0.3 L/min oxygen by placing the mouse into a commercially available induction box (23 cm (length) x 10 cm (width) x 10 cm (height)). The mouse was transferred from the induction box to a water-based heating pad covered with an absorbent pad and placed into a custom-made head holder. Isoflurane, 1–3% in 0.3 L/min oxygen, delivered via a nose cone, was used to maintain the level of anesthesia (Fig. 1a and Supplemental Fig. 3).

The surgical approach to the right bulla. (a) Place the mouse into the head holder and incise the skin along the white line, approximately 2 cm. (b) Retract the skin to expose the submandibular glands (SMG). Identify the anterior belly of the digastric muscle (AD). Separate the right and left SMG along the white dashed line by blunt dissection. (c) Retract the right SMG and identify the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle, AD, and PD, respectively. The location of the bulla is below the PD (white arrow). (d) Detach the intermediate tendon from the hyoid bone and elevate the PD to expose the bulla region (box) and outer ear canal (thin white arrow). Avoid manipulating the facial nerve (thick arrow). Further, retract the muscles to expose the bulla.

Preparation of the surgical field

With a commercially available Wahl clipper (Supplemental Table 2), the animal’s fur was removed well beyond the expected incision line (Fig. 1a). The area was cleaned three times with betadine solution and 75% alcohol in an alternate order, wiping the cleaning fluid away from the center of the surgical field. Drapes under the animal and drapes covering the nose cone and exposed animal parts created a sterile field. Towel Clamps (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2: Tool #1) held the drapes in place.

Access to the bulla

Figure 1 shows in detail the surgical access to the bulla. First, in the supine position, the mouse was mounted to the nosecone of the custom-made head holder (Fig. 1a). Any other head holder will work if the mouse head is not moving during the creation of the access to the cochlea. The surgery began with an approximately 2 cm skin incision using a small pair of sharp scissors (Supplemental Table 2: Tools #2 and #3), starting close to the right shoulder, lateral from the midline, towards the mandible along the dashed white arrow (Fig. 1a). Using blunt dissection, the tissue over the submandibular glands (SMGs) was removed (Fig. 1b), and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle (AD) became visible. The white dashed line in Fig. 1b highlights the boundary between the left and right SMG, along which they were separated (Fig. 1c, Supplemental Table 2: Tool #2). Retracting the right SMG exposed the entire digastric muscle with its anterior (AD) and posterior bellies (PD). The PD was the landmark at which to approach the bulla. The white arrow in Fig. 1c points to the location of the bulla below the PD. Scissors were not used for the surgery’s following steps to minimize the risk of cutting small blood vessels. Instead, the tissue was dissected carefully with sharp forceps (Supplemental Table 2: Tools #4 and #5) to expose the digastric muscle’s origin. Figure 1d shows the bulla after elevating the PD; the bulla and outer ear canal are visible (dashed box, Fig. 1d and Supplemental Table 2: Tools #4 and #5). It is important not to manipulate the facial nerve (thick arrow). After the dissection, the muscles were retracted with a custom-made tool (Supplemental Figure 2c, Supplemental Table 2: Tool #6). Careful muscle dissection with pointed forceps exposed the bulla (Fig. 2a and Supplemental Table 2: Tools #4 and #5).

Opening the bulla and creating the cochleostomy

The surgical bullostomy and cochleostomy are made using a Buckingham drill, a motorized drill with a burr, or a CO2 laser. Any tools will work for the bullostomy, but the cochleostomy is more challenging. The burr and the Buckingham drill often impede the cochlea’s direct view, frequently resulting in a much larger cochleostomy than required to insert the osmotic pump’s catheter. In contrast to the burr, the CO2 laser allows adequate visual control over the cochleostomy site while creating the opening (Fig. 2f). Laser ablation follows the absorption of infrared radiation. Because of the Gaussian laser beam profile, carbonization of the tissue might occur at the edges of the laser beam. In this study, we have not measured ABR thresholds in the right ear after making the cochleostomy and implanting the osmotic pump. However, a previous study demonstrated little CAP threshold elevation after creating a cochleostomy in the guinea pig cochlea using the same laser38. The 4 W laser power setting in the guinea pig elevated CAP thresholds by less than 10 dB. At the 5 W and 6 W laser power settings, the CAP thresholds were elevated by 32 dB; at the 10 W laser power setting, the CAP threshold elevation was 20–40 dB. Threshold elevations were localized to the site of the cochleostomy. In contrast to creating the cochleostomy with the laser, the same study has shown that drilling a cochleostomy resulted in 50% of the cases in a drastic elevation of the CAP threshold with no auditory responses for frequencies above 7 kHz. For the remaining cochleostomies created by drilling, threshold elevations were less than 20 dB and were localized to frequencies between 10 and 20 kHz.

The figure describes the opening of the bulla. (a) View and access to the bulla after retraction of the muscles. (b) shows a sketch of (a), providing the orientation of the field of view; identifiable structures are the tympanic bulla (TB), the tympanic ring (TR), and the zone of interest for the bullostomy. (c) An approximately 200 μm opening in the bulla is made with the CO2 Laser by delivering a 100 ms single pulse at a 5 W power setting. (d) This opening is then widened with the fine-pointed forceps until the basal cochlear turn is visible. The stapedial artery (SA) denotes the stapedial artery, and (CB) the cochlear bone. (e) The mouse head is rotated to visualize the malleus (m) and tympanic membrane (TM). (f) is the image of a 100 μm cochleostomy created with the CO2 Laser by delivering a single 100 ms pulse at a 7 W power setting. The malleus and tympanic membrane can still be identified from the field of view.

For the mouse surgeries, the CO2 laser power setting to make the bullostomy was 5 W, 100 ms pulse width, in single pulse mode (Fig. 2). The setting was 7 W, 100 ms pulse width, in single pulse mode for creating an approximately 150-µm cochleostomy in the cochlear basal turn.

Drug delivery into the right cochlea protected the left contralateral cochlea from noise-induced hearing loss. Based on those findings, the ear used to study the drug effects was on the other, non-implanted ear, as described previously22,34.

Using the laser bears the risk of nicking the stapedial artery. To use the Buckingham drill for making or enlarging the cochleostomy (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2: Tool #7), the tip of the Buckingham drill should be less than 100 μm in diameter.

ALZET pump placement

Supplemental Fig. 4 describes the intraoperative catheter and osmotic pump assembly, and Fig. 3 the surgical placement. For the pump assembly, the catheter, the osmotic pump, and its access port were placed (Supplemental Fig. 4a,b) on the sterile drape. The ALZET pump was loaded with the drug using the filling needle. The effects of drug delivery loaded in these pumps were studied by Depreux et al. and are not reported in this article34. The drugs were either 50 µM fluvastatin or its carrier alone34. The catheter was shortened (Supplemental Fig. 4b) and connected to the access port (Supplemental Fig. 4c). Before joining the catheter to the pump, it was flushed with the drug, ensuring no air bubbles had been introduced (Supplemental Fig. 4d, e). The fluid drop at the catheter’s tip (Supplemental Fig. 4f) confirms the pump’s successful assembly. The assembled ALZET pump was inserted into a pocket under the skin over the thorax (Fig. 3a), which was made by blunt dissection with a pair of pointed scissors. Two pairs of forceps (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2; Tools #4 and #5) were used to manually insert the pump towards the shoulder blades and push it into its final position. Since the osmotic pump was placed on the animal’s back, its catheter was positioned below the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 3b and c). After tunneling the catheter, its tip was gently bent (Fig. 3b, c) and inserted with a pair of fine forceps (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2; Tool #5) through the cochleostomy (Fig. 3c). The cochleostomy was slightly larger than the catheter’s outer diameter. Additional tissue was required to seal the opening.

The figure shows the osmotic pump placement. (a) A subdermal pocket is formed over the shoulder by separating the fascia (label “F”) from the skin (label “S”) using a pointed scissor, allowing the insertion and final ALZET pump placement. It is important to remove the retractor before inserting the pump to prevent tissue damage by the retractor. Elevation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (star) accommodates the pump’s catheter (white arrow). The dashed circle encircles the bulla. (b,c) After insertion of the pump, the catheter (white arrow) is carefully bent with forceps toward the bulla (dashed circle). Sternocleidomastoid muscle (star) (d). The catheter tip is placed through the hole of the cochleostomy (black arrow). The cochleostomy is slightly larger than the catheter’s diameter, and no additional tissue is placed to seal the opening (the stapedial artery is labeled as SA and the tympanic bulla as TB). (e) The catheter is stabilized in its position by filling the middle ear cavity with dental acrylic. (f) The tissue covering the bulla limits tissue desiccation during the 5 min of the acrylic polymerization time (Submandibular glands labeled as SMG).

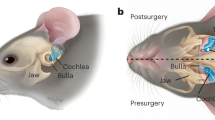

The cochleostomy’s exact location and the catheter orientation determined whether the catheter’s orifice was toward scala tympani or scala vestibuli. Cochleostomy sites closer to the stapes and the catheter’s orientation toward the cochlear base placed the tubing tip into scala vestibuli. In contrast, cochleostomy locations closer to the stapedial artery and the bulla’s medial wall, with catheter orientations toward the bulla’s medial wall, placed the catheter’s tip into the scala tympani. In some experiments, we confirmed the catheter tips’ locations through micro-computed tomography with synchrotron radiation (see the section below: Image acquisition and tomographic reconstruction, Fig. 4a). After placing the catheter, we stabilized it in its position by filling the middle ear cavity with methyl methacrylate acrylic using a 1 mL syringe and 22G needle (Fig. 3e). During the 5 min of acrylic polymerization, we covered the bulla with the SMG and skin to limit desiccation (Fig. 3f). During the polymerization process, the temperature may increase at contact points. However, the volume of the acrylic is small, and it is surrounded by other large tissues during this step, which offsets the increase in temperature.

Post-surgical recovery. The figure shows the catheter (micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)) and pump placement in the mouse. (a) Micro-CT images of the catheter placement were obtained at the end of the study. The distal opening of the catheter is below the stapes footplate (S) in scala vestibuli. Fibrous tissue seals the cochleostomy (yellow star). The yellow dashed arrow highlights the center of the catheter tubing. The two red (˫) signs delimited the exterior of the catheter walls (outer diameter 130 μm, inner diameter 100 μm). (b) shows an implanted mouse. This mouse was sternal 4 min post-surgery and moved freely with no visible vestibular effects or impediments to ambulation (Supplemental Video 1). White dashed lines delimit the shape of the implanted pump. The scale bar in A equals 500 μm.

Histology after implantation

After euthanasia, the catheters were removed from the bullae. In sixteen right ears, which were removed two weeks after the implantation, the remaining pump volume was determined after aspiration of the fluids inside the pump. The measures showed that about half of the volume was ejected in fifteen ears. This is expected as the designed delivery period for the pumps is 4 weeks. One of the pumps failed to deliver the drugs. The catheter was likely blocked. The results showed that the pump was working as expected. However, this finding is not proof that the entire volume was injected into the cochlea. We had no means of following the path of the fluid ejection.

Right ears (bullae and cochleae) were harvested from the temporal bone and fixed overnight in 4% PFA in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at 4 °C. Tissues were washed in PBS the following day and stored at 4 °C in 0.25% PFA in PBS buffer. After separating the cochleae from the bullae, they were rinsed in PBS several times and sectioned by hand with a fresh razor blade along the mid-modiolar plane running through the cochlea. The resulting cochlear sections were dehydrated with acetone at increasing concentrations: 25%-50%-75%-90%-100%-100%-100% acetone39. Each step took 15 min. From 100% acetone, the samples were transferred to Araldite resin (ARALDITE/Embed embedding kit#13940 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) six steps: 7:1, 1:1, and 1:7 acetone-to-resin ratio, followed by three infusions in pure plastic for 1 h each step. The araldite resin was cured overnight at 60 °C. Three-micron-thick sections were cut along the mid-modiolar plane using an ultramicrotome (LKB 8800 Ultrotome III, Stockholm-Bromma, Sweden) and placed on glass slides. The sections were stained with 0.05% toluidine blue (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 1% sodium tetraborate aqueous solution.

Five right-implanted cochleae were processed for histology as described under Sect. 2.5. Three cochleae showed no signs of epithelial cell hyperplasia lining the periosteum of the cochlear bone (Supplemental Fig. 5A). The captured images had no signs of cellular damage in the basilar membrane, organ of Corti (inner and outer hair cells, pillar cells, supporting cells), lateral wall (stria vascularis, spiral prominence, and spiral ligament), modiolus, and Rosenthal canal (Suppl Fig. 5A and B). In two samples, epithelium hyperplasia was spread across the cochleostomy site into scala media and tympani (supplemental Fig. 5C). One sample had tissue proliferation in all scalae, including the helicotrema.

Skin closure and suture

The skin incision was closed with two layers using interrupted sutures (Supplemental Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2: Tool #8 or #11 and #9). For the first layer, we used 6 − 0 (VICRYL) absorbable suture material and 6 − 0 (ETHICON) non-resorbable suture for the skin. During this last step, the percentage of isoflurane was decreased to a minimum of 1-1.5% under continuous monitoring of the mouse’s anesthesia level. The closed incisions were cleaned with two alternating swabs of Betadine solution and alcohol (75%). The anesthetic delivery was discontinued, and the animal was removed from the head holder and placed in the supine position in a recovery box on top of a heating pad. The animal was under continuous supervision until sternal and freely ambulant. The recovery time was, on average, 6 min (min) and 52 s (s) (2–19 min, n = 45) after stopping the flow of isoflurane (Fig. 5). The pump was visible on the mouse’s back but did not affect the animal’s movements and activity (Fig. 4B, Supplemental Video 1).

Outcome measures. Reduced breathing rates (RD), bleeding (HM), and vestibular symptoms (VD) did not increase surgical length (a) or recovery (b) times when compared to mice with no such events, classified in the figure as “Fine” or sham (exposed to anesthesia only). Moreover, mice undergoing surgery had significantly increased recovery time compared to sham (anesthesia-only) mice. The surgery duration is between switching the anesthesia machine to the “ON” and the “OFF” position. Recovery from anesthesia is when the mouse moves from a supine to a sternal position. Statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. Statistical analysis using One-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. Graphs show means ± Standard Deviation (SD). P values are indicated in the brackets; ns = insignificant.

Post-surgical pain management

For post-surgical pain management, we injected buprenorphine subcutaneously (SC) every 12 h over 48 h.

Post-surgical animal handling

Animal handling after the surgery was gentle to avoid dislocation and damage to the newly implanted osmotic pump. Mice were single-housed in fresh and clean cages after the surgery to prevent the risk of injury by cage mates. Some of the former cotton bedding/nest was transferred into a new cage to reduce mouse stress from being left alone in a new environment. A food paste made of water-saturated food pellets was placed in the cage close to the mouse nest for easy access. It was essential to change the food every day. Visual mouse pain monitoring included, but was not limited to, looking for the shape of eyelids, porphyrin patches around the eyes, back positioning, the status of nest building, the animal’s activity level, and gait during frequent mouse observations40,41,42,43,44. The animals’ weight was monitored over two weeks.

Image acquisition and tomographic reconstruction

All cochleae were imaged at the 2-BM-B beamline of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) using monochromatic radiation with photon energies of 22 kilo-electron volts (keV). The detector-sample distance was 600 mm for phase contrast. A 5x objective lens was used in the detector system, resulting in an approximately 3 × 3 mm2 field of view. Over a range of 180 degrees, we captured projections of each sample at increments of 0.12 degrees. The exposure time for a single image was 0.2–0.3 s. At the beginning and end of each image series, flat field images (no object in the beam path) were recorded; after the series, a dark field image (the radiation beam was blocked) was captured.

The projections were used to reconstruct the cochlea. Custom-written phase retrieval software for non-interferometric phase imaging with partially coherent X-rays was used45,46,47. Reconstructions were on a 2048 × 2048 grid with custom-written software48. The reconstructions resulted in 1.45 μm isotropic voxels. The spatial resolution was determined from the system’s response to a sharp discontinuity in the image, such as a bony edge. The parameter measured was the distance required for the gray values to fall from 90% to 10%. The resulting distance was 4.4 μm.

Events observed during and after surgery

Under optimal anesthesia, the mouse’s expected heart rate is between 300 and 450 beats per minute (bpm), with an oxygen saturation above 96% and a breathing rate of around 55–65 breaths/min49. Four out of 45 mice (8.9%) had an episode with fewer than 50 bpm breathing rates. Decreasing the isoflurane concentration to 0.5% for 1 to 3 min restored normal breathing and respiratory rates. While little to no bleeding during the surgeries is typical, in 6 out of 45 mice (13.3%), for example, bleeding from the jugular vein occurred after the retractor nicked the vessel. Gentle pressure with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator stopped the bleeding. Bleeding also occurred while making the cochleostomy (3 mice, 6.7%). Since the mouse’s head was not tightly fixed in the head holder, it moved slightly with the animal’s breathing. The stapedial artery moved similarly, and in rare instances, into the beam path of the CO2 laser or drilling while creating the cochleostomy. Bleeding by opening the stapedial artery could be severe, and it was difficult to stop. It is important to record bleeding events and episodes of hypoxia as they may affect mouse hearing.

The vestibular system is close to the cochlear base and can be affected by the catheter’s placement. Symptoms indicating vestibular stimulation or damage (VDs) included a tilted head, shaking the head, a twirling body, and the mouse’s inability to extend arms toward the cage to grab it while held by the tail. Vestibular symptoms showed in 19 out of 45 mice up to 72 h post-surgery and did not recover over time. All mice showing vestibular symptoms had the catheter implanted toward the base of the cochlea.

Overall, the above-described incidents did not affect surgical and recovery times (Fig. 5). After surgery, the mice’s body weight decreased by 3.56 ± 3.12% and 6.28 ± 9.90% at 24 h and one week, respectively. The body weight was back to or above pre-surgery levels two weeks after the surgery. On average, mice presenting signs of vestibular damage lost more weight (11.95 ± 12.73% one-week post-surgery). Two mice from the VD group were euthanized for losing more than 25% of body weight during the first week after the surgery (Supplemental Fig. 6). No other animal required euthanasia in this study.

Discussion

A modified ventral approach to the cochlea allows the implantation of an osmotic pump for long-term drug delivery in mice. Our modifications to the published procedure14,33 include different locations for the bullostomy and cochleostomy and the use of a laser. The manuscript provides a detailed description of the ALZET mini-osmotic pump implantation and the surgical outcomes. In contrast to the dorsal approach described for electrode placement50, labyrinthectomy, and vestibular neurectomy51, the ventral approach provides easier access to the cochlea with the mouse fixed on the nasal holder. It offers better control over the facial nerve, as Jero et al. discussed14. The ventral approach also offers minimal morbidity and mortality.

A potential alternative approach for drug delivery to the cochlea would be the long-term placement of the pump’s catheter into a semicircular canal. In the initial phase of the project, we entertained this possibility. However, the long-term fixation of the catheter in the semi-circular canal posed a challenge we could not address.

Our protocol stresses the approach to the middle ear by using the digastric muscle as a landmark. Identifying the posterior digastric muscle allows for moving quickly to the ear with minimal displacement of adjacent tissues. The use of a small retractor maintains the field of view. After the surgery, skin closure in two layers reduces the risk of wound dehiscence.

Mice are social animals, and single housing after surgery may delay recovery52. However, the single housing of the surgically treated mice is important. Housed together, they tend to chew their sutures, resulting in wound dehiscence.

ALZET osmotic pumps require several hours of priming in sterile saline solution at 37 °C to deliver drugs immediately after implantation. The priming time depends on the model (https://www.alzet.com/resources/alzet-technical-tips/#1560367975183-ba1896c5-0e75/). Based on experimental consideration, this step can be omitted to circumvent any break in the sterile chain of the pump.

Hemorrhage and reduced respiratory rate episodes were the two surgical events that required quick intervention. However, surgery length, sternal recovery time, and body weight were not different in mice with complications from mice exhibiting no surgical problems (“fine” group). The stapedial artery, persistent in adult mice53, is a branch of the internal carotid artery. The stapedial artery passes through the stapes, branches of the medial meningeal artery, and runs rostrally, forming its infraorbital branch. The stapedial artery does not constitute a blood supply for the cochlea and has been obliterated during surgical approaches54 without affecting cochlear function. Consequently, bleeding from the stapedial artery is unlikely to affect the cochlea but causes problems through blood accumulation in the middle ear. Injuring the jugular vein with the retractor was less severe. The primary bleeding issue may lead to a decreased total blood volume. Both respiratory distress and severe bleeding during the surgery resulted in elevated ABR thresholds in our hands. Even if post-surgical recovery of animals encountering noticeable bleeding during surgery did not seem to differ from the “fine” group, study rigor might require excluding these animals.

The typical isoflurane setting was 1-1.5% after the anesthesia induction. Settings must deliver enough anesthetic to ensure a sufficient anesthesia level but not expose the mice to excessive isoflurane, depressing breathing, and increasing anesthesia recovery times. Isoflurane is a non-flammable volatile anesthetic approved by the Federal Drug Administration for general anesthesia induction and maintenance in humans and animals55. According to Constantinides et al.56, isoflurane is the primary anesthetic used in mouse animal models. In the central nervous system, isoflurane likely inhibits neurotransmitter-gated ion channels such as GABA, glycine, and NMDA receptors55,57. Skeletal muscles, including thorax ones, become relaxed, increasing PaCO255. Therefore, inadequate high isoflurane levels lead to bradycardia and lower respiratory rates49. Episodes of reduced respiratory rates during a few surgeries may have originated from too deep anesthesia levels.

Similar to Jero et al.14, we observed vestibular symptoms in implanted mice. The direction of the catheter toward the cochlear base correlates with the frequency of vestibular symptoms. Vestibular symptoms, such as those described in the 2.2.13 section, may result from mechanical damage caused by advancing the catheter too far towards the cochlear base or through the direct flow of the injected fluids into the cochlea. Vestibular function was not systematically assessed by measuring vestibular myogenic or sensory evoked potentials (VEMP or VsEP)58,59,60,61,62,63,64. Therefore, the number of mice with post-surgical vestibular deficiencies may underestimate the number of mice affected. It is essential to realize that vestibular damage, especially if severe, is debilitating for the mouse. It is likely disrupting the affected mouse’s ability to feed and drink adequately, particularly during the critical surgical recovery period. Mice may lose excess weight, so they must be euthanized or removed from the study.

Placement of the catheter in the scala tympani of the cochlear base22 likely delivers the drugs near the cochlear aqueduct65. The delivered compounds may reach the contralateral ear22,66,67,68 via this path. Talaei et al. (2019)69 showed that trypan blue delivered via the round window diffuses toward the cochlear apex.

Most of our implanted mice underwent a terminal hearing assessment two weeks after implantation. In some cases, the evaluation was done after four weeks. The effect of the drug delivery to the cochlea was determined by the change in hearing as determined by the ABR thresholds. They were typically obtained from the non-implanted ear34. Since detailed data on the ABR thresholds have been reported previously34 they are not shown in this manuscript. In guinea pigs, implanted ears presented about 20 dB ABR threshold elevation22. These ABR threshold elevations can be explained by histological data from the implanted cochlea. The specimen showed scar tissue, mainly at the scala vestibuli of the basal turn near the cochleostomy. The basilar membrane and organ of Corti appeared intact.

Conclusion

Surgical protocols for osmotic pump implantation to deliver solution into mouse inner ears are sparsely available. Here, we inform about a surgical method to chronically implant an osmotic pump in mice to deliver the drug into the basal cochlear turn. The technique was successfully used to study hearing protection in the contralateral ear. While a Buckingham or motorized drill can be used to create the bullostomy and cochleostomy, we suggest using a CO2 laser. The protocol is flexible such that the cochleostomy location can be adapted for other regions of the cochlea, depending on the investigator’s study. It can deliver drugs, nucleic acids, compounds, or viruses into the implanted ear, potentially targeting the contralateral ear. Vestibular sequelae were related to the orientation of the catheter. The hearing of the implanted ear will be affected by fibrosis resulting from post-surgical inflammation and the presence of the catheter.

Data availability

All data analyzed have been shown in the paper. The raw data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

El Kechai, N. et al. Recent advances in local drug delivery to the inner ear. Int. J. Pharm. 494, 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.08.015 (2015).

Salt, A. N. & Plontke, S. K. Local inner-ear drug delivery and pharmacokinetics. Drug Discov Today. 10, 1299–1306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03574-9 (2005).

Li, Y. et al. Comparison of inner ear drug availability of combined treatment with systemic or local drug injections alone. Neurosci. Res. 155, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2019.07.001 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Endoscopic intratympanic methylprednisolone injection for treatment of refractory sudden sensorineural hearing loss and one case in pregnancy. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 39, 640–645 (2010).

Dormer, N. H., Nelson-Brantley, J., Staecker, H. & Berkland, C. J. Evaluation of a transtympanic delivery system in Mus musculus for extended release steroids. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 126, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2018.01.020 (2019).

Hoffer, M. E. et al. Transtympanic versus sustained-release administration of gentamicin: kinetics, morphology, and function. Laryngoscope 111, 1343–1357. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200108000-00007 (2001).

Li, L., Ren, J., Yin, T. & Liu, W. Intratympanic dexamethasone perfusion versus injection for treatment of refractory sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 270, 861–867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-012-2061-0 (2013).

Plontke, S. K., Zimmermann, R., Zenner, H. P. & Lowenheim, H. Technical note on microcatheter implantation for local inner ear drug delivery: surgical technique and safety aspects. Otol Neurotol. 27, 912–917. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000235310.72442.4e (2006).

Sale, P. J. P. et al. Cannula-based drug delivery to the guinea pig round window causes a lasting hearing loss that may be temporarily mitigated by BDNF. Hear. Res. 356, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2017.10.004 (2017).

Maini, S. et al. Targeted therapy of the inner ear. Audiol. Neurootol. 14, 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1159/000241897 (2009).

Murillo-Cuesta, S. et al. Direct drug application to the round window: a comparative study of ototoxicity in rats. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 141, 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2009.07.014 (2009).

Sheppard, W. M., Wanamaker, H. H., Pack, A., Yamamoto, S. & Slepecky, N. Direct round window application of gentamicin with varying delivery vehicles: a comparison of ototoxicity. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 131, 890–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2004.05.021 (2004).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comparison of the distribution pattern of PEG-b-PCL polymersomes delivered into the rat inner ear via different methods. Acta Otolaryngol. 131, 1249–1256. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2011.615066 (2011).

Jero, J., Tseng, C. J., Mhatre, A. N. & Lalwani, A. K. A surgical approach appropriate for targeted cochlear gene therapy in the mouse. Hear. Res. 151, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00216-1 (2001).

Farrah, A. Y., Al-Mahallawi, A. M., Basalious, E. B. & Nesseem, D. I. Investigating the potential of phosphatidylcholine-based nano-sized carriers in boosting the oto-topical delivery of caroverine: in vitro characterization, stability assessment and ex vivo transport studies. Int. J. Nanomed. 15, 8921–8931. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S259172 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Understanding the translocation mechanism of PLGA nanoparticles across round window membrane into the inner ear: a guideline for inner ear drug delivery based on nanomedicine. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 479–492. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S154968 (2018).

Glueckert, R., Pritz, C. O., Roy, S., Dudas, J. & Schrott-Fischer, A. Nanoparticle mediated drug delivery of rolipram to tyrosine kinase B positive cells in the inner ear with targeting peptides and agonistic antibodies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 71. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00071 (2015).

Maina, J. W. et al. Mold-templated inorganic-organic hybrid supraparticles for codelivery of drugs. Biomacromolecules 15, 4146–4151. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm501171j (2014).

Paasche, G., Bogel, L., Leinung, M., Lenarz, T. & Stover, T. Substance distribution in a cochlea model using different pump rates for cochlear implant drug delivery electrode prototypes. Hear. Res. 212, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2005.10.013 (2006).

Paasche, G. et al. Technical report: modification of a cochlear implant electrode for drug delivery to the inner ear. Otol Neurotol. 24, 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/00129492-200303000-00016 (2003).

Brown, J. N., Miller, J. M., Altschuler, R. A. & Nuttall, A. L. Osmotic pump implant for chronic infusion of drugs into the inner ear. Hear. Res. 70, 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5955(93)90155-t (1993).

Richter, C. P. et al. Fluvastatin protects cochleae from damage by high-level noise. Sci. Rep. 8, 3033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21336-7 (2018).

O’Leary, S. J., Klis, S. F., de Groot, J. C., Hamers, F. P. & Smoorenburg, G. F. Perilymphatic application of cisplatin over several days in albino guinea pigs: dose-dependency of electrophysiological and morphological effects. Hear. Res. 154, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00232-5 (2001).

Kim, J. & Ricci, A. J. A chemo-mechanical cochleostomy preserves hearing for the in vivo functional imaging of cochlear cells. Nat. Protoc. 18, 1137–1154. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-022-00786-4 (2023).

Plontke, S. K. & Salt, A. N. Local drug delivery to the inner ear: Principles, practice, and future challenges. Hear. Res. 368, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2018.06.018 (2018).

Mader, K., Lehner, E., Liebau, A. & Plontke, S. K. Controlled drug release to the inner ear: Concepts, materials, mechanisms, and performance. Hear. Res. 368, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.006 (2018).

Hao, J. & Li, S. K. Inner ear drug delivery: recent advances, challenges, and perspective. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 126, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2018.05.020 (2019).

Nyberg, S., Abbott, N. J., Shi, X., Steyger, P. S. & Dabdoub, A. Delivery of therapeutics to the inner ear: the challenge of the blood-labyrinth barrier. Sci. Transl Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aao0935 (2019).

Tandon, V. et al. Microfabricated reciprocating micropump for intracochlear drug delivery with integrated drug/fluid storage and electronically controlled dosing. Lab. Chip. 16, 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5lc01396h (2016).

Lee, M. Y. et al. Dexamethasone delivery for hearing preservation in animal cochlear implant model: continuity, long-term release, and fast release rate. Acta Otolaryngol. 140, 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2020.1763457 (2020).

Hu, B., Salvi, R. J. & Henderson, D. The technique of chronic infusion of drugs into the cochlea by an osmotic pump. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 33, 169–171 (1998).

Kim, E. S. et al. A microfluidic reciprocating intracochlear drug delivery system with reservoir and active dose control. Lab. Chip. 14, 710–721. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3lc51105g (2014).

Chen, Z., Mikulec, A. A., McKenna, M. J., Sewell, W. F. & Kujawa, S. G. A method for intracochlear drug delivery in the mouse. J. Neurosci. Methods. 150, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.017 (2006).

Depreux, F. et al. Statins protect mice from high-decibel noise-induced hearing loss. Biomed. Pharmacother. 163, 114674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114674 (2023).

Council, N. R. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. https://doi.org/10.17226/12910 (The National Academies Press, 2011).

Stokes, E. L., Flecknell, P. A. & Richardson, C. A. Reported analgesic and anaesthetic administration to rodents undergoing experimental surgical procedures. Lab. Anim. 43, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1258/la.2008.008020 (2009).

Clark, T. S., Clark, D. D. & Hoyt, R. F. Jr Pharmacokinetic comparison of sustained-release and standard buprenorphine in mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 53, 387–391 (2014).

Fishman, A. J., Moreno, L. E., Rivera, A. & Richter, C. P. CO(2) laser fiber soft cochleostomy: development of a technique using human temporal bones and a guinea pig model. Lasers Surg. Med. 42, 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.20902 (2010).

Teudt, I. U. & Richter, C. P. The hemicochlea preparation of the guinea pig and other mammalian cochleae. J. Neurosci. Methods. 162, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.012 (2007).

Gaskill, B. N., Karas, A. Z., Garner, J. P. & Pritchett-Corning, K. R. Nest Building as an indicator of health and welfare in laboratory mice. J. Vis. Exp. 51012 https://doi.org/10.3791/51012 (2013).

Langford, D. J. et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Methods. 7, 447–449. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1455 (2010).

Miller, A. L. & Leach, M. C. The mouse grimace scale: A clinically useful tool? PLoS One. 10, e0136000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136000 (2015).

Graf, R., Cinelli, P. & Arras, M. Morbidity scoring after abdominal surgery. Lab. Anim. 50, 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023677216675188 (2016).

Oliver, V. L., Thurston, S. E. & Lofgren, J. L. Using cageside measures to evaluate analgesic efficacy in mice (Mus musculus) after surgery. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 57, 186–201 (2018).

Paganin, D. & Nugent, K. A. Noninterferometric phase imaging with partially coherent light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2586–2589 (1998).

Paganin, D., Mayo, S. C., Gureyev, T. E., Miller, P. R. & Wilkins, S. W. Simultaneous phase and amplitude extraction from a single defocused image of a homogeneous object. J. Microsc. 206, 33–40 (2002).

Weitkamp, T., Haas, D., Wegrzynek, D. & Rack, A. ANKAphase: software for single-distance phase retrieval from inline X-ray phase-contrast radiographs. J. Synchrotron Rad. 18, 617–629 (2011).

Gursoy, D., De Carlo, F., Xiao, X. & Jacobsen, C. TomoPy: a framework for the analysis of synchrotron tomographic data. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 21, 1188–1193. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577514013939 (2014).

Ewald, A. J., Werb, Z. & Egeblad, M. Monitoring of vital signs for long-term survival of mice under anesthesia. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011, pdb prot5563. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot5563 (2011).

Soken, H. et al. Mouse cochleostomy: a minimally invasive dorsal approach for modeling cochlear implantation. Laryngoscope 123, E109–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24174 (2013).

Simon, F. et al. Surgical techniques and functional evaluation for vestibular lesions in the mouse: unilateral labyrinthectomy (UL) and unilateral vestibular neurectomy (UVN). J. Neurol. 267, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09960-8 (2020).

Pham, T. M. et al. Housing environment influences the need for pain relief during post-operative recovery in mice. Physiol. Behav. 99, 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.038 (2010).

Kuchinka, J. The stapedial artery in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). Anat. Rec (Hoboken). 301, 1131–1137. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23801 (2018).

Emadi, G., Richter, C. P. & Dallos, P. Stiffness of the gerbil basilar membrane: radial and longitudinal variations. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00446.2003 (2004).

Hawkley, T. F., Preston, M. & Maani, C. V. Isoflurane (StatPearls Publishing, 2021).

Constantinides, C., Mean, R. & Janssen, B. J. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the cardiovascular function of the C57BL/6 mouse. ILAR J. 52, e21–31 (2011).

Jones, M. V., Brooks, P. A. & Harrison, N. L. Enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid-activated Cl- currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurones by three volatile anaesthetics. J. Physiol. 449, 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019086 (1992).

Sheykholeslami, K., Megerian, C. A. & Zheng, Q. Y. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in normal mice and Phex mice with spontaneous endolymphatic hydrops. Otol Neurotol. 30, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e31819bda13 (2009).

Willaert, A. et al. Vestibular dysfunction is a manifestation of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 179, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.7 (2019).

Honaker, J. A., Lee, C., Criter, R. E. & Jones, T. A. Test-retest reliability of the vestibular sensory-evoked potential (VsEP) in C57BL/6J mice. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 26, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.26.1.7 (2015).

Jones, T. A. et al. The adequate stimulus for mammalian linear vestibular evoked potentials (VsEPs). Hear. Res. 280, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2011.05.005 (2011).

Jones, S. M. et al. Hearing and vestibular deficits in the Coch(-/-) null mouse model: comparison to the Coch(G88E/G88E) mouse and to DFNA9 hearing and balance disorder. Hear. Res. 272, 42–48 (2011).

Jones, S. M. et al. Stimulus and recording variables and their effects on mammalian vestibular evoked potentials. J. Neurosci. Methods. 118, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00125-5 (2002).

Jones, T. A. & Jones, S. M. Short latency compound action potentials from mammalian gravity receptor organs. Hear. Res. 136, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00110-0 (1999).

Salt, A. N. & Hirose, K. Communication pathways to and from the inner ear and their contributions to drug delivery. Hear. Res. 362, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2017.12.010 (2018).

Stover, T., Yagi, M. & Raphael, Y. Transduction of the contralateral ear after adenovirus-mediated cochlear gene transfer. Gene Ther. 7, 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3301108 (2000).

Roehm, P., Hoffer, M. & Balaban, C. D. Gentamicin uptake in the chinchilla inner ear. Hear. Res. 230, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2007.04.005 (2007).

Kho, S. T., Pettis, R. M., Mhatre, A. N. & Lalwani, A. K. Safety of adeno-associated virus as cochlear gene transfer vector: analysis of distant spread beyond injected cochleae. Mol. Ther. 2, 368–373. https://doi.org/10.1006/mthe.2000.0129 (2000).

Talaei, S., Schnee, M. E., Aaron, K. A. & Ricci, A. J. Dye tracking following posterior semicircular canal or round window membrane injections suggests a role for the cochlea aqueduct in modulating distribution. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 471. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00471 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Office of Naval Research (N000141210173; N000141512130; N000141612508); a grant from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Hearing Restoration Research Program under award number W81XWh-20-1-0484; and a grant to the APS by the USDOE, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science under contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38. We thank Microlumen for the generous gift of the polyimide catheter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Frederic Depreux was involved in data curation; formal analysis; investigation; writing original draft, review, and editing. Donna Whitlon was involved in Conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing-review and editing. Claus-Peter Richter performed surgery, and involved in investigation, methodology; writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Depreux, F., Whitlon, D. & Richter, CP. ALZET pump implantation in mice for chronic drug delivery to the cochlea. Sci Rep 15, 36379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20395-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20395-x