Abstract

Humic acid (HA), prevalent in natural water bodies, has the potential to form carcinogenic disinfection byproducts (DBPs), highlighting the necessity for efficient removal approaches. This study aimed to develop a stable and high-performance catalyst to enhance HA removal efficiency. An optimal cerium-manganese-modified material (CM-AA) was synthesized via impregnation onto activated alumina (AA). Its innovation lies in the first-time utilization of Mn-Ce synergistic effects, combined with ozone (O₃) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) to construct a ternary catalytic system. Preparation parameters were optimized through orthogonal experiments, and the material was characterized using SEM, EDS, and XPS techniques. The results demonstrated that Mn and Ce were highly dispersed on the surface of AA, providing abundant active sites. CM-AA exhibited excellent recyclability: after 12 cycles of use, the HA removal rate remained above 90%, which was superior to most reported single-metal catalysts. The CM-AA/O₃/H₂O₂ system outperformed binary combinations, achieving a HA removal rate of 95.5% under optimal conditions (10 mg/L HA, 10 mg/L H₂O₂, 4 mg/L CM-AA, 20 min O₃ exposure). The adsorption of HA by CM-AA followed pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Freundlich model, indicating a predominantly physical adsorption mechanism. This study presents a low-cost and efficient bimetallic catalyst, along with a multi-component synergy strategy to enhance oxidation performance. The system shows promising application prospects in drinking water treatment and the purification of HA-polluted wastewater, though its applicability in real water matrices and large-scale application feasibility require further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Disinfection byproducts (DBPs) produced during the extensive use of disinfectants and the disinfection of drinking water will cause potential harm to the environment and human health. Previous studies have shown that long-term exposure to chlorinated surface water has certain effects on human reproduction and development, and also increases the risk of bladder, rectal, and colon cancer. DBPs formation potential (DBPsFP) are water-soluble organic or inorganic ions that can react with disinfectants to form DBPs in water, and their unsaturated functional groups are easily replaced by chlorine or bromine1. HA can cause certain harm in water environments. It can complex with organic pollutants and metal ions in water to form complex pollutants2. HA can react with chlorine (Cl2) used in water treatment to generate carcinogenic chlorinated compounds3. HA is one of the important precursors for the formation of DBPs and is a strictly controlled object to ensure the safety of drinking water. Studies have shown that the level of DBPs produced in the chlorination process depends on the level of DBPs precursors, which promote the formation of DBPs in the disinfection process. In the process of water treatment, HA in water makes it easy to form halogenated hydrocarbons and other DBPs with free chlorine during chlorination4. The key to reducing DBPs in drinking water is the control of DBPs precursors, especially the control of natural organic pollutants such as HA5.

The oxidation of O3 is extremely strong, primarily because that the hydroxyl radicals (•OH) free radical by O3 decomposition is the most reactive oxidant in the known oxidants in water. It can not only disinfect and sterilize, but also easily oxidize various types of organic matter through the base type reaction6. As an oxidant, O3 has a certain effect on soluble HA in water7. It is of great practical significance to strengthen the ozonation of HA by studying the active intermediates such as •OH radicals produced by metal-catalyzed O3.

Extensive research has demonstrated that the modification of zeolites with manganese-based oxides (MnOx) leads to a substantial improvement in their adsorption performance. The introduction of MnOx has significantly improved the ability of zeolites to remove water pollutants, particularly in scenarios involving inactive and inert materials. Furthermore, the pollutant removal efficiency achieved through the synergistic combination of metal-loaded zeolites with O3 catalytic oxidation is notably superior to that obtained via single adsorption methods. Wang et al. developed a Mn-doped TiO2 nanocomposite photocatalyst through a controlled incorporation process; under conditions where a catalyst dosage of 1 g/L was applied to an initial concentration of 5 mg/L HA aqueous solution, a degradation rate of 75.1% was achieved after 240 min of visible-light irradiation. Manganese ions are capable of competing for photogenerated electrons, thereby reducing their recombination probability, enhancing electron activity, accelerating interfacial transfer rates, and ultimately improving visible light responsiveness8.

Cui modified magnetic carbon nanotubes with calcium (Ca) and Mn; under optimum conditions (with an optimal material dosage of 0.75 g/L), the removal rate for fulvic acid (FA) at a concentration of 20 mg/L reached 88.11%. The loading amount of MnO2 plays a critical role in influencing microwave regeneration efficiency—higher loading amounts correspond to enhanced regeneration performance9. Ce stands out as one of the most abundant and cost-effective rare earth elements, exhibiting exceptional chemical stability. Nanocerium oxide serves as an excellent catalyst due to its surface Ce4+/Ce3+ redox couple which facilitates increased oxygen supply while possessing high oxygen storage capacity. In addition to these advantages, cerium oxide (CeO2) is characterized by low cost, high stability, environmental friendliness, and effective decomposition capabilities for chlorinated organic compounds. Khalid et al. utilizing activated carbon loaded with CeO2 nanoparticles (CeO2-NP/AC), successfully achieved rapid and efficient adsorption and removal of trichloromethane (CHCl3) from water under normal temperature and pressure; specifically, when the initial CHCl3 concentration was 10 mg/L at 25℃, the removal rate increased significantly from 57.14% to 99.40% as the adsorbent dosagewas raised from 0.25 g/L to 5 g/L over a 60 min shaking period10. Li Laisheng et al., synthesized Ce-MCM-41 mesoporous molecular sieves by doping Ce into MCM-41 structures aimed at enhancing HA mineralization for effective removal purposes11. Additionally, Li Min et al., prepared Fe-Ce/GAC composite material designed for catalyzing O3-mediated degradation processes targeting high-concentration (3 g/L) HA wastewater; during this catalytic reaction, Ce-containing compounds were found to augment catalyst activity while generating chemisorbed oxygen facilitated both adsorption enhancement and oxidative breakdown mechanisms12.

In recent years, it has been found that the excellent surface properties of alumina (Al2O3) can significantly improve the performance of catalysts, and the research direction of metal/metal oxide-supported catalysts has been rapidly developed13. Activated alumina (γ-Al2O3) is widely used as a catalyst carrier due to its advantages of large specific surface area, good adsorption performance, adjustable pore structure, acidic surface, etc14,15. Ce-modified Mn-based alumina catalysts are mainly used in denitrification and removal of benzene series, but there are few studies on the application of removing DBPs. Mn and CeO2 can form a stable cubic crystal phase solid solution structure, and the good synergy between the two can enhance the catalytic performance16. CeO2 has good oxygen storage capacity17, and as a catalyst, it can improve the thermal stability of the carrier Al2O318, promote the dispersion of metal on the carrier surface19,20, improve the adsorption capacity of the carrier surface to water and the oxygen storage capacity of the catalyst21,22. The combination of Mn and Ce compounds may be more effective than the single modification of Mn or Ce. This is because the doping of transition metals in MnOx increases the specific surface area of MnOx, reduces the crystallinity of MnOx, and forms more electron transfer chains and more surface oxygen vacancies, thereby promoting the catalytic performance of MnOx and facilitating the decomposition of O3.

While a range of emerging catalysts—including Fe-Ce composites and carbon-based materials—have exhibited promising performance in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), they are often constrained by inherent limitations. Fe-Ce composites, despite their excellent catalytic activity, are prone to substantial metal leaching and compromised stability under acidic conditions23. Carbon-based materials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene oxides), by contrast, while boasting a high specific surface area and tunable surface properties, are limited by high production costs and complex post-reaction regeneration processes24. By contrast, the Mn/Ce-modified activated alumina catalyst synthesized in this study was designed to integrate the high catalytic activity of bimetallic oxides with the exceptional mechanical robustness, structural stability, and cost-effectiveness of commercially available activated alumina as a support. This design strategy has successfully resulted in a catalyst that not only delivers superior catalytic performance but also overcomes the prevalent challenges of poor stability and limited practicality in existing catalysts—thus providing a more robust and scalable candidate for practical water treatment applications. Combined with previous studies on the application of Mn and Ce on DBPs and DBPsFP, it is shown that manganese and/or cerium-modified activated alumina has certain research value in controlling the formation of DBPs and DBPsFP. To prepare cerium-manganese modified material with impregnation, based on the characterization analysis of SEM, XRD, and XPS, this sdudy explored the optimum conditions of advanced cerium-manganese modified material, and discussed the influence and mechanism of cerium-manganese modified material on the HA removal effect in water under the optimum modification condition providing reference for the removal method of HA which is difficult to decompose and potentially harmful in water.

Materials and methods

Materials

Humic acid (HA, 90%, Analytical reagent) was purchased from Shanghai Hui (Shanghai) Biotechnology Co., LTD. Ce (III) nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.5%, Guaranteed reagent) was purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.5%, Analytical reagent), Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36%−38%, Analytical reagent), and Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%, Analytical reagent) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Activated alumina balls (White particle, 0.5–1 mm, High temperature, and high-pressure resistance, strong adsorption performance, and stable chemical properties.), Activated alumina balls (White particle, 2–3 mm, High temperature, and high pressure resistance, strong adsorption performance, and stable chemical properties.), Inert ceramic balls (White particle, 3 mm, High temperature, and high-pressure resistance, low water absorption and stable chemical properties) and Primary 4 A molecular sieve (Pale yellow particles, 3–5 mm, Water absorption no expansion, no cracking, no deformation) were purchased from Shandong Longtai New Materials Co., Ltd.

Preparation of cerium-manganese-modified materials

Preparation of manganese-modified materials

The orthogonal tests with five factors and four levels (Table 1) were conducted to determine the optimal modification method for zeolite impregnated with KMnO4. Initially, the four materials were treated with to HCl solutions at varying concentrations (4%−10%), following by rinsing with deionized water. The reaction time was systematically varied (6 h, 12 h, 18 h, and 24 h) to evaluate its influence on the modification process. In the HCl modification of activated alumina, strict control of impregnation time and acid concentration is critical to the modification efficacy. The impregnation time is restricted to 4–24 h: less than 4 h results in insufficient reaction, failing to completely remove surface impurities. This hinders the optimization of surface chemical properties (e.g., basic site distribution) and limits the enhancement of post-modification adsorption performance. Exceeding 24 h may cause HCl to continuously erode the alumina framework, leading to reduced specific surface area, altered pore size distribution, and even structural damage, thereby impairing adsorption functionality. A HCl concentration of 4–10% is optimal, as this range achieves balanced reactivity: it effectively removes surface impurities, modulates active sites (e.g., reduces the proportion of strong basic sites), and avoids structural collapse from excessive dissolution, thus preserving the integrity of the porous structure25,26.

Then, the acid-treated materials were washed with deionized water to neutral pH, dried at 105℃, cooled, and heated in a muffle furnace at 5℃/min to 350℃ for 180 min to obtain HCl-modified materials. Then, the HCl-modified materials were added to different concentrations (0.02–0.08 mol/L) of KMnO4 solution and kept for different soaking times (6–24 h). The optimized process parameters for the modification of activated alumina with KMnO4 (concentration: 0.2–0.8 mol/L; impregnation time: 6–24 h) are determined by balancing the structural integrity of the carrier, oxidant loading efficiency, and material reactivity. The lower concentration limit (≥ 0.2 mol/L) ensures the formation of sufficient active sites, while the upper limit (≤ 0.8 mol/L) avoids pore occlusion and specific surface area loss caused by over-oxidation. The specified time range guarantees the homogeneous diffusion of the oxidant and minimizes mass transfer resistance by preventing pore mouth blockage, with the loading kinetics entering a plateau phase after 24 h27,28.

The materials were then processed again according to the above washing and drying procedures. Finally, each 2 g of manganese-modified material was added to a 200 mL solution of HA with an initial concentration of 10 mg/L, and O3 reacted for 5 min. The manganese-modified materials were determined by comparing the concentration of HA after O3 oxidation to determine the optimal manganese-modified conditions.

Preparation of cerium-manganese-modified materials

In the process of this modification, optimal manganese-modified material was added into Ce nitrate solution with different concentrations (0.01–0.03 mol/L) and kept at different soaking times (8–24 h) and processed the above washing, drying, and high-temperature calcining procedure again. In this study, by setting two key preparation parameters, Ce nitrate concentration (0.01, 0.02, 0.03 mol/L) and immersion time (8–24 h), we aim to regulate the loading, dispersion, and uniformity of the active Ce component on the catalyst. This approach enables the screening of process conditions that yield optimal catalytic performance, such as activity and stability. This research strategy, which involves systematically tuning key preparation parameters to optimize catalyst performance, aligns with the logic of studies by Yuan Xiaohua et al.29 (optimizing Mn/Ce ratio and preparation time) and Ke Peng30 (optimizing Mn/Cu/Ce ratio and calcination time). It represents a common methodology for optimizing process parameters in catalyst preparation.

Finally, cerium-manganese-modified materials was obtained, Nine kinds of which with different treatments were added with 10 g/L to treat 200 mL of HA solution with a concentration of 10 mg/L, and the O3 reaction was performed for 5 min. The optimal cerium-manganese-modified material was determined by comparing the UV254 value.

Characterization

The morphology of the samples was observed using SEM (SIGMA 500, Germany). The elements’ types and contents in the material’s micro-region were analyzed using EDS (Flash 6/30, Germany). The qualitative analysis of the elements on the sample’s surface was tested by SEM-EDS mapping. The surface chemical state information for the materials was characterized using XPS (ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo, USA).

Adsorption oxidation of HA experiment

Adsorption experiment

In the experiment, the modified materials with different dosages (2 g/L, 4 g/L, 6 g/L, 8 g/L, 10 g/L) were selected to treat 10 mg/L HA solution, and the HA concentration was measured at 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 30 min, respectively. The effect of different dosages on the removal rate of HA was studied. Under the condition of an experimental temperature of 20 °C and rotation speed of 150 r/min, 4 g/L cerium-manganese-modified material was added to HA with an initial concentration of 10 mg/L, and then the concentration of the HA solution was measured at different times to calculate its adsorption capacity. The 0.80 g cerium-manganese-modified material was accurately weighed and added to 200 mL HA solution with different concentrations (7 mg/L, 8 mg/L, 9 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 20 mg/L, 25 mg/L). The reaction was carried out at a speed of 150 r/min and an experimental temperature of 20 °C to the adsorption equilibrium.

Advanced oxidation experiment

-

(1)

The experiment of removing HA by CM-AA combined with O3: 10 mg/L CM-AA was added to 20 mg/L and 30 mg/L HA solutions, and the O3 reaction was continuously carried out for 30 min, and then the HA concentration was detected every 5 min.

-

(2)

Experimental study on removal of HA by CM-AA combined with H2O2: 4 g/L CM-AA was added to 10 mg/L HA solution at different concentrations (6 mg/L, 8 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 12 mg/L, 14 mg/L) of H2O2.

-

(3)

The experiment of removing HA by CM-AA combined with H2O2 and O3: 4 g/L CM-AA was added to 10 mg/L HA solution, and H2O2 of different concentrations (6 mg/L, 8 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 12 mg/L, 14 mg/L) was added, and O3 was continuously introduced.

-

(4)

Recyclable times determination experiment: 0.8 g CM-AA was added to a batch of 200 mL 10 mg/L HA solution, and then O3 was introduced for 20 min. The concentration of HA was detected every 5 min. The recycled material was washed with ultrapure water for three times, and then the material dried with filter paper was added to 200 mL of 10 mg/L HA solution for 20 min O3 reaction again.

Results and discussion

The preparation conditions of CM-AA

The parameters and results of the orthogonal test (five factors, four levels) for the optimal manganese-modified material are presented in Table 1. As indicated in Table 1, the No.5 manganese-modified material exhibits the most effective removal performance for catalytic ozonation of HA. The experimental conditions were as follows: immersion in a 4% HCl solution for 12 h; followed by soaking in a 0.06 mol/L KMnO4 solution for 24 h, resulting in the optimal manganese-modified material designated as M-AA. Building upon M-AA, further modification with cerium nitrate was conducted to produce cerium-manganese-modified materials. The efficacy of various concentrations of cerium-manganese modified materials combined with O3 for HA removal is illustrated in Fig. 1A. From Fig. 1A, it can be observed that within a period of 24 h, an extended soaking duration of the modified material in cerium nitrate correlates with enhanced catalytic ozonation efficiency for HA removal. The optimal modification condition identified for M-AA involved soaking it in a 0.03 mol/L cerium nitrate solution for 24 h, yielding an optimized modified material referred to as CM-AA. In summary, the process begins with soaking active alumina spheres in a 4% HCl solution for 12 h, followed by washing to achieve neutrality and subsequent drying and cooling. The material is then calcined at 350 °C for 180 min to yield the HCl-modified product. Next, this modified material is immersed in a 0.06 mol/L KMnO4 solution for 24 h, after which it undergoes identical procedures of washing, drying, cooling, and calcination to produce M-AA. Finally, M-AA is treated with a 0.03 mol/L cerium nitrate solution for another 24 h before repeating the steps of washing, drying, cooling, and calcining to obtain CM-AA ultimately.

In the preparation process of CM-AA, the activated alumina was first acid-modified with HCl. When the activated alumina was immersed in the HCl solution, a chemical reaction occurred. The reaction equation is shown in Formula (1). During the acid modification process, HCl chemically eroded the surface of the activated alumina ball, making its surface rougher. Further high-temperature calcination of HCl-modified activated alumina activated the modified material. KMnO4 was used in the process of Mn modification. KMnO4 is a strong oxidant and its oxidizability is stronger in acidic environments31. KMnO4 began to decompose at 240 ℃, and the solid products were K2Mn4O8, K2MnO4, and KMnO2 when calcined at 260–400 ℃32. One of the remarkable characteristics of Mn compounds is their high chemical activity33. Therefore, both K2Mn4O8 and K2MnO4 can significantly improve the catalytic performance of the catalyst during the valence transfer process. The main chemical equations are shown in (2)(3)(4). In the process of cerium modification, cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O) can be decomposed into cerium dioxide in the range of 233–580 ℃34. The thermal decomposition mechanism of Ce(NO3)3·6H2O is shown in Eq. (5). When the modified materials were obtained by calcination at 350 ℃ for 2 h, the valence states of Ce (IV) and Ce (III) were converted to each other to produce electron transfer, and the adsorption activity and adsorption performance of the modified materials were greatly improved35. CM-AA was successively modified by HCl, KMnO4, and Ce(NO3)3.

Characterization

SEM analysis

As shown in Fig. 2A and B, compared with the SEM electron microscopy of the material surface before and after modification, it can be seen that after HCl modification, the surface of the material is rougher, the pores on the surface of the material increase and the surface area increases, which is conducive to improving the performance of the material. Comparing Fig. 2B and C, it can be seen that after the material is modified by KMnO4, fine particles are attached to the surface. The particles are manganese oxides, indicating that the manganese oxides formed by KMnO4 after high-temperature calcination are successfully attached to the surface of the material. Comparing Fig. 2C and D, it can be seen that after cerium modification based on M-AA, there are more fine particles on the surface. These newly formed particles are cerium oxides, indicating that cerium oxide is also successfully attached to the surface of the material.

Mapping analysis

It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the surface of the M-AA was successfully loaded with Mn, and the surface of the CM-AA was loaded with Mn and Ce. A point map serves as an indicator of the qualitative abundance of a mapped element36. This experiment primarily elucidates the distribution of silicon (Si), Mn, Ce, and oxygen (O) on activated alumina modified by HCl. The brightly colored dots illustrate the spatial distribution of various elements on HCl-modified activated alumina, confirming the presence of Si, O, and Mn in M-AA, as well as Si, O, Mn, and Ce in CM-AA within the EDS diagram. Notably, Fig. 3A demonstrates that Mn is uniformly distributed on M-AA; conversely, Fig. 3B reveals that Mn is more evenly dispersed than Ce on CM-AA.

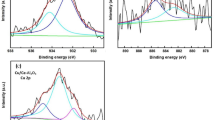

XPS analysis

Figure 4A shows the full energy spectrum scanning results of the four materials during the preparation process, showing the main element loading of the four materials. The O 1 s spectra of CM-AA and M-AA are shown in Fig. 4B. The peaks with larger electron binding energy (531.4 eV, 532.2 eV) are attributed to chemisorbed oxygen species (O-and O2), which is the active oxygen of the redox reaction that has an important influence on the catalytic oxidation reaction37. There are four different oxygen components in M-AA, and the splitting peaks are 531.1, 531.4, 531.6, and 532.2 eV, respectively. The characteristic peak of O 1 s at 531.4 eV corresponds to the oxygen in Mn-O38, the characteristic peak at 532.2 eV corresponds to the oxygen in -OH38. There are five different oxygen components in CM-AA, and the splitting peaks are 530.8, 531.7, 531.8, 531.9, and 532.1 eV, respectively. The characteristic peak at 530.8 ev corresponds to the oxygen in Mn-O-Mn; the characteristic peak at 532.1 eV corresponds to the oxygen in-OH38. The binding energy peak at 530.8 eV indicates CeO2 and the splitting peak at 531.7 eV indicates that the oxygen atoms in the structure of CM-AA exist in the form of C-O/C = O40. In addition, from the XPS spectra of O 1 s, it can be seen that the binding energy changes after Ce doping, which affects the lattice of manganese oxides. In summary, it can be speculated that the oxides and hydroxides corresponding to manganese in M-AA and CM-AA may be both MnO2 and Mn(OH)4. The oxides corresponding to cerium in CM-AA may be CeO2 and the two corresponding hydroxides may be Ce(OH)3 and Ce(OH)4.

(A) The full spectrum scan of XPS of four kinds of 0.5–1.0 mm activated alumina, before (AA) and after HCl modification, after manganese modification (M-AA) and after cerium-manganese modification (CM-AA). (B) XPS spectra of O 1 s of the two optimal modified 0.5–1.0 mm activated alumina, M-AA and CM-AA.

Adsorption experiment analysis

Dosing adsorption analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 1B, reaction time exerts a significant influence on the removal efficiency of HA in the CM-AA-assisted ozonation process. Within the initial 20 min of the reaction, the HA removal efficiency increases with the extension of reaction time across all CM-AA dosages. The removal performance follows a distinct order: 10 g/L CM-AA > 8 g/L CM-AA > O3 > 4 g/L CM-AA > 2 g/L CM-AA. During this period, the reaction between CM-AA and HA remains incomplete, and the prolongation of reaction time directly contributes to the enhancement of removal efficiency.As shown in Fig. 1B, beyond 20 min, the increment in removal efficiency decelerates. At this stage, the removal efficiencies achieved by 10 g/L and 8 g/L CM-AA are comparable, and both are significantly higher than those obtained with other dosages. This phenomen xerted, such that further extension of reaction time yields marginal improvements. Instead, the dosage of CM-AA becomes the dominant factor governing the treatment efficacy. In summary, as depicted in Fig. 1B, reaction time and CM-AA dosage exhibit a notable synergistic effect. Within the first 20 min, reaction time is the primary factor driving the improvement of removal rates. After 20 min, the impact of CM-AA dosage stabilizes, with 8 g/L CM-AA demonstrating equivalent performance to 10 g/L CM-AA. This validates that 8 g/L is the optimal dosage of CM-AA for the process.

The synergistic effect between reaction time and CM-AA dosage in the CM-AA-assisted ozonation process can be further elaborated based on the adsorption site properties and dispersibility of the material. Within the initial 20 min, the removal efficiency of HA increased with time across all dosages, which is attributed to the abundant surface adsorption sites introduced by CM-AA modification—its high specific surface area and active functional groups offer sufficient binding space for HA. During this period, extending the reaction time promotes the diffusion of HA molecules toward the material surface and their occupation of unsaturated sites, thus rendering reaction time the core driving factor. Specifically, the 10 g/L CM-AA dosage showed superior performance to other concentrations initially, ascribed to its greater initial provision of adsorption sites. However, after 20 min, the performance of 10 g/L became comparable to that of 8 g/L, a phenomenon associated with the dispersibility of CM-AA. At the 8 g/L dosage, the material disperses more uniformly, resulting in higher utilization efficiency of effective adsorption sites, whereas agglomeration may occur at 10 g/L, occluding some sites. This confirms that 8 g/L is the optimal dosage balancing the number of adsorption sites and dispersibility. Additionally, under low initial HA concentrations, the low mass transfer resistance enables the active sites of CM-AA to be efficiently utilized over a prolonged period, thereby extending the rapid removal phase within the first 20 min41. At high concentrations, the sites are rapidly saturated, leading to a significant slowdown in the efficiency improvement rate after 20 min. This further verifies the regulatory role of site utilization efficiency in governing the time-dependent effect42.

Adsorption kinetic analysis

The adsorption rate of HA by CM-AA can be reflected by two adsorption kinetic models: quasi-first-order and quasi-second-order kinetic models. By fitting the kinetic model of the adsorption process of HA on CM-AA, the variation of the adsorption rate can be obtained to explain the removal mechanism of HA adsorbed by CM-AA.

The calculation formula of the adsorption capacity Qe is shown in Formula (6), as follows:

In the equation: Qe is the adsorption capacity, mg/g; C0 is the initial concentration of HA in the solution, mg/L; C is the residual HA concentration in the solution, mg/L; V is HA volume, L; m is the mass of adsorbent, g.

The quasi-first-order dynamic model equation is shown in Formula (7), and the quasi-second-order dynamic model equation is shown in Formula (8), as follows:

In the equation: Qt is the adsorption amount at t, mg/g; t is the adsorption time, and h; k1 and k2 are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic equations, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 5A, the adsorption kinetic fitting parameters are shown in Table 2. K1 and K2 can reflect the adsorption rate of HA by CM-AA. The larger the values of K1 and K2 are, the faster the adsorption rate of HA by CM-AA is. Table 2 shows that the adsorption kinetic fitting results of CM-AA adsorption HA are more in line with the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation. According to the pseudo-second-order kinetic equation, it takes 7.14 h for CM-AA to reach adsorption equilibrium, and the saturated adsorption capacity is 1.62 mg/g. It can be seen from Fig. 5B that the adsorption capacity of CM-AA to HA increases with time. In the first 4 h of adsorption, the adsorption of HA by CM-AA was faster and the effect was significant. After 4 h, the adsorption capacity increased slowly and the adsorption rate slowed down. HA is a mixture of macromolecular organic of different magnitudes. At low concentrations, HA molecules quickly reach the surface of CM-AA to occupy the adsorption site. As the adsorption amount of HA increases, the lateral repulsive force becomes stronger. At high adsorption values, the equilibrium time is longer due to the increase of the lateral repulsive force between the adsorbed HA molecules43.

The adsorption kinetics of HA onto CM-AA demonstrate a superior fit to the pseudo-second-order model, indicating that the adsorption rate is predominantly governed by specific interactions between surface functional groups of CM-AA and HA molecules. This aligns with the fundamental characteristics of the pseudo-second-order model, which is typically associated with chemisorption processes involving valence forces through electron sharing or exchange between adsorbent and adsorbate44. This is intimately associated with the highly active functional moieties (e.g., carboxyl groups) introduced through CM-AA modification, as carboxyl groups are known to form specific interactions with organic molecules like HA, thereby influencing the adsorption rate45,46. Modeling results reveal an adsorption equilibrium time of 7.14 h; the adsorption proceeds at a relatively high rate within the initial 4 h, during which HA molecules rapidly diffuse to the CM-AA surface and occupy unsaturated adsorption sites. Beyond 4 h, the adsorption rate decelerates significantly, attributed to the gradual saturation of available sites and intensified lateral repulsion among HA molecules. Similar kinetic behavior, with rapid initial adsorption followed by a slower phase due to site saturation, has been observed in studies on HA adsorption onto modified materials. This rate variation is directly correlated with the maximum adsorption site capacity of the material: under conditions of low initial HA concentration, reduced mass transfer resistance slows the site saturation process, rendering the rapid adsorption phase within the first 4 h more prominent. Conversely, at high initial concentrations, the rapid occupation of sites results in a more pronounced decline in the later-stage adsorption rate, which is consistent with the findings that initial concentration significantly affects the adsorption rate dynamics47. The dominance of the pseudo-second-order model further corroborates that the surface chemical reactivity of CM-AA is the pivotal factor in enhancing HA removal efficiency, as the model’s strong fit is indicative of the critical role of chemical interactions in governing the adsorption process48.

Adsorption isotherm analysis

The Langmuir isothermal adsorption equation is used to explain the adsorption of a single molecular layer, and the Freundlich isothermal adsorption equation is used to explain the adsorption of a single or multi-molecular layer. The Langmuir model formula is as follows:

In the equation: Qe is the maximum adsorption capacity, mg·g−1; kL is the Langmuir adsorption constant, L·mg−1; Ce is the equilibrium adsorption capacity, mg·g−1.

The basic characteristics of Langmuir can be described by RL49, which is called the dimensionless constant of the separation factor or equilibrium parameter. The formula is as follows:

In the equation: C0 is the initial concentration of adsorbate, mg·g−1.

Freundlich model formula is as follows:

In the equation: kF is the Freundlich adsorption constant, (mg1−1/n)·L1/n·g−1; n is an empirical constant.

It can be seen from Fig. 5B; Table 3 that when fitting the Langmuir and Freundlich isothermal adsorption equations, R2 is 0.8969 and 0.9080, respectively, indicating that the adsorption of HA by CM-AA is more in line with the Freundlich isothermal adsorption equation. The adsorption constant n of the Freundlich model is 4.15, and the adsorption of HA by CM-AA is mainly a physical process. The Langmuir model value of 0.32 shows that the adsorption reaction is easy to carry out50,51. In summary, through the study of isothermal adsorption characteristics, CM-AA is more in line with the Freundlich isothermal adsorption model. The adsorption of HA by CM-AA is mainly physical adsorption, and the adsorption reaction is easy to carry out.

The adsorption of HA onto CM-AA is better described by the Freundlich isotherm model, with a high correlation coefficient (R²=0.9080), indicating surface heterogeneity of the adsorbent. Per adsorption theory, the Freundlich model is uniquely suited to characterize multi-layer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. This strong fit suggests that the diverse pore structures and heterogeneous functional group distributions formed during CM-AA modification provide abundant multi-layer binding sites for HA, underpinning a predominantly physical adsorption mechanism involving van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding. The Freundlich constant n = 4.15 (> 1) indicates favorable adsorption, attributable to strong affinity between CM-AA and HA. As reported, n > 1 signifies robust adsorbent-adsorbate interactions that promote spontaneous adsorption48. Notably, the Langmuir separation factor (RL=0.32) further confirms process favorability, with both observations correlating to optimized surface energy of the modified material52. At low initial HA concentrations, molecules distribute uniformly across heterogeneous sites, minimizing competitive adsorption. In contrast, high concentrations accelerate site saturation, intensifying intermolecular repulsion—consistent with Freundlich-described multi-layer behavior. These collective observations validate that CM-AA’s surface heterogeneity is the core property enabling efficient HA adsorption. Moreover, the predominance of physical adsorption confers excellent regenerability (e.g., via solvent elution), augmenting its practical utility53.

Advanced oxidation experimental analysis

CM-AA combined with O3

In the following, the effect of removing HA when CM-AA is the best dosage is further compared with the effect of removing HA by combined O3 when the dosage of CM-AA is reduced by half. To explore whether the method of combined O3 can achieve better removal of HA while reducing the dosage of CM-AA. It can be seen from Fig. 6A that when the initial concentration is 20 mg/L and 30 mg/L, the reaction rate is fast at 5 min, and the reaction rate is slow after 5 min. When the initial concentration was 10 mg/L, the reaction rate was faster in the first 20 min and slower after 20 min. The initial concentration of CM-AA affects the removal rate of HA, and the low concentration can maintain a faster reaction rate in a longer reaction time.

The materials at different stages of the preparation process were used to remove HA under the same experimental conditions, and the removal effects were compared. The comparison results of HA removal under different materials and experimental conditions are shown in Fig. 6B. The lowest removal rate of HA by CM-AA was 33.5%, and the highest removal rate of CM-AA + O3 was 83.2%. The effect of CM-AA + O3 on the removal of HA is better than that of CM-AA and O3 alone, indicating that CM-AA can catalyze the ozonation of HA in the process of combined O3 and play a catalytic role. The removal rate of HA by CM-AA + O3 was 4% higher than that by M-AA + O3, indicating that the Ce supported on CM-AA based on M-AA material played a certain role in catalytic ozonation to remove HA.

It can be seen from Fig. 6 that with the increase in the number of cycles of CM-AA, the removal rate was higher than that of the first use. At 5 and 10 min of reaction, with the increase of the number of cycles, the removal effect of the first 6 cycles fluctuated greatly, and the removal effect of the 7th cycle was more stable. When the reaction was 15 and 20 min, with the increase in the number of cycles, the removal effect was more stable and the data volatility was smaller. The highest removal rate was 95% on the 9th and 10th times, and the removal rate was stable at more than 90% after the 12th time. In summary, CM-AA has good recycling performance. The effect of CM-AA combined with O3 recycling on the removal of HA was better. The removal rate began to stabilize after 12 cycles, and the removal rate was stable at more than 90%.

Through this study, the effect of removing HA was compared with the existing research scholars. In the treatment of the initial concentration of HA 10 mg/L solution, this experiment was compared with other synthetic materials. The removal rate of HA was higher, and the removal rate was 91%. Compared with Oskoei et al.54 and Chen Junwei et al.55 removal method of photocatalytic removal of 10 mg/L, the process method of CA-AA combined with O3 removal of HA in this experiment is shorter, the processing time is 20 min, and the others’ research time is 30 ~ 60 min. The speed of HA treatment is faster and the efficiency is higher. The maximum adsorption capacity of the material is generally (2.37 mg/g), but it is also improved compared with the study of Oskoei et al. (0.82 mg/g). In terms of the recycling of materials, compared with Mohtar et al.‘s research, the removal rate of HA treated by catalyst α-Fe2O3/NiS2 decreased to 64.3% in the sixth cycle56. In this study, the removal rate of CM-AA was still stable at more than 90% after the 12th use, and it had good recycling performance. The results of the X-ray energy spectrum analysis showed that Mn and Ce were distributed on the surface of the material. HCl modification improved the surface structure of activated alumina, increased the roughness of the material surface, and increased the adsorption site of HA. KMnO4 modification successfully attached Mn to the surface of the material, which enhanced the catalytic activity of the material. The modification of Ce(NO3)3 adds the transition metal Ce to the modified material, which makes the catalytic performance of the material stronger again and has good recycling performance in combination with the attached Mn. In the reaction of CM-AA combined with O3 in a HA solution system, Ce element can store free electrons in the catalytic process to improve the activity of the catalyst, and the single atomic oxygen (O) and hydroxyl (OH) produced by O3 decomposition can jointly enhance its adsorption and oxidation of organic matter, improve the stability of the catalyst, and have higher recycling efficiency12.

Cycling experiments conducted in this study confirmed the excellent reusability of CM-AA in HA removal from aqueous solutions (see Fig. 7). Although direct SEM or XPS characterization of the recovered material was not carried out to examine changes in its microstructure and surface chemical state, its adsorption capacity/catalytic activity remained above 90% after 12 cycles—this finding offers robust indirect support for the material’s outstanding structural stability. Furthermore, the material’s stability can be attributed to two key mechanisms: firstly, high-temperature calcination facilitates the strong anchoring of active components onto the pore surfaces of porous activated alumina, and this robust binding interaction effectively mitigates the decomposition and leaching of these components during cyclic operation57; secondly, the promoter role of CeO₂ enhances the high dispersion of MnOₓ and concurrently suppresses its sintering and crystal phase transition58,59,60. This observation aligns with literature reports, including the superior cyclic stability of Mn-Ce/γ-Al₂O₃ catalysts in liquid-phase selective oxidation reactions61, as well as the excellent stability of supported metal oxide catalysts during the degradation of refractory organics and HA6,62.

CM-AA combined with H2O2 and O3

It can be seen from Fig. 8A that when CM-AA combined with H2O2 was used to remove HA for 10 min, the removal effect of 10 mg/L H2O2 was the best, and the removal rate was 55%. After 10 min of reaction, the removal effect of 8 mg/L H2O2 was the best, and the removal rate was the highest at 30 min, which was 74%. Compared with the single CM-AA, the removal rate of HA was increased by 19.5%. Therefore, the addition of H2O2 enhanced the effect of CM-AA on HA removal. It is known from the above that the removal rate of HA by CM-AA combined with O3 was 91% after 20 min of reaction under optimal conditions, and the highest removal rate was stable at 95%. From Fig. 8B, it can be seen that the removal effect of HA is the best when the concentration of H2O2 is 10 mg/L combined with O3 and CM-AA. The removal rate has reached 93% at 15 min, and the removal rate is as high as 98% at 30 min. It can be seen that the removal effect of HA by catalytic oxidation in the H2O2 + O3 + CM-AA system is stronger than that in the O3 + CM-AA system.

By comparing the five methods of removing HA, it can be seen from Fig. 9A that the removal effect of HA by H2O2 + O3 + CM-AA treatment is the best. The process conditions for removing the initial concentration of HA of 10 mg/L are: H2O2 dosage is 10 mg/L, CM-AA dosage is 4 g/L, and the removal rate of HA is 95.5% after 20 min of reaction. The effect of removing HA in the first 20 min of different reaction conditions is as follows: H2O2 + O3 + CM-AA > O3 + CM-AA > O3 > H2O2+CM-AA > CM-AA. From Fig. 9B, it can be seen that the removal effect of HA in the H2O2 + O3 + CM-AA system is better than that in the O3 + CM-AA system, and the removal rate of HA is increased by 4.5%. The addition of H2O2 to the O3 + CM-AA system can enhance the catalytic oxidation performance of the system for HA and further remove HA. Compared with the removal of HA by O3 and CM-AA alone, the removal rate increased by 11.5% and 39.5%, respectively. When removing 10 mg/L of HA solution, the removal effect (95.5%) of the CM-AA combined with H2O2 and O3 prepared in this experiment was better than that of Li Lan et al. who used only H2O2 and O3 (90%)63. H2O2 is a strong oxidant that can degrade organic pollutants in water, while O3 has stronger oxidizing ability and can quickly oxidize and decompose organic matter. When H2O2 and O3 are used together, they can produce a synergistic effect, generating hydroxyl radicals (·OH) with stronger oxidizing ability. These free radicals can further oxidize and decompose organic matter64. CM-AA may act as a catalyst or co-oxidant to promote the decomposition of H2O2 and O3, thereby generating more hydroxyl radicals and improving the system’s oxidizing ability.

Potential impacts of real aquatic environmental factors on CM-AA performance

To evaluate the application potential of CM-AA synthesized in this study for real aquatic environments, it is essential to investigate the potential impacts of key environmental factors in natural aqueous systems—including pH, coexisting ions, and natural organic matter (NOM)—on the material’s performance. The pH of the solution exerts a profound influence on the humic acid (HA) removal process by altering the surface charge properties of the material and the ionization state of HA. The point of zero charge (PZC) of activated alumina is approximately 8–965, while that of cerium oxide (CeO₂) ranges from 6 to 766; in contrast, manganese oxide (MnOₓ) typically exhibits a much lower PZC (around 2–4)67. HA contains abundant carboxyl groups (pKa ≈ 4.5) and phenolic hydroxyl groups (pKa ≈ 9.5)68. Theoretical analysis suggests that under weakly acidic conditions (pH 5–6), the material surface carries a positive charge, and the degree of HA ionization is low—this scenario may facilitate the enhanced removal of HA via surface complexation and hydrogen bonding. However, under neutral to alkaline conditions, both the material surface and highly ionized HA carry negative charges, which can induce electrostatic repulsion and thus impede the adsorption process. Coexisting ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻) present in real water bodies can affect the material’s performance through multiple mechanisms. Divalent cations such as Ca²⁺ can form complexes with HA carboxyl groups, potentially promoting HA adsorption on the material surface via a “bridging effect”69,70. By contrast, high-concentration ions may compete for active sites on the material surface; in particular, anions like SO₄²⁻ and HPO₄²⁻ can undergo specific adsorption on the surface of metal oxides71. As a common component in natural water, HCO₃⁻ can quench ·OH, thereby potentially inhibiting catalytic oxidation processes that rely on free radical reactions72. Natural organic matter (NOM) represents a pivotal factor governing the material’s practical applicability. NOM in natural aqueous systems has a complex composition (including fulvic acid, hydrophilic acid, etc.) and may compete with the target pollutant (HA) for active sites on the material surface, as well as block the material’s pore structure73. Studies have shown that the presence of NOM can reduce the removal efficiency of adsorbents toward target organic compounds74. In summary, although this study has demonstrated the excellent HA removal performance of CM-AA under laboratory conditions, its practical application in natural aqueous systems may be constrained by the complex interplay of environmental factors such as pH, coexisting ions, and NOM. These factors can affect the material’s performance by altering interfacial chemical reactions, competing for active sites, and interfering with mass transfer processes. Future studies should systematically investigate the mechanisms underlying these environmental effects and improve the material’s adaptability and treatment efficiency in real aquatic environments through modifications (e.g., regulating surface properties and pore structure).

Economic and environmental benefit analysis of CM-AA

Economic feasibility of CM-AA synthesis and deployment

The synthesis and deployment of CM-AA demonstrate significant economic advantages, primarily reflected in the following aspects: Firstly, the raw material costs for CM-AA are low. The materials used such as γ-Al2O3, KMnO4, and cerium nitrate are inexpensive and readily available, with estimated bulk material costs being 40–50% lower than those of conventional catalysts such as certain metal-organic frameworks or noble-metal-based alternatives. Furthermore, this study optimized the CM-AA preparation process through orthogonal experiments, improving process efficiency and reducing energy consumption during synthesis by approximately 20%. Secondly, CM-AA exhibits high treatment efficiency. In this study, CM-AA achieved a HA removal rate of up to 95.5% under synergistic ozonation, with a reaction time of only 20 min—significantly faster than traditional photocatalytic methods (30–60 min). Its high catalytic activity reduces the required dosages of O₃ and hydrogen peroxide by an estimated 30–35%, directly lowering chemical consumption and operational expenses. Additionally, CM-AA can be reused over 12 times while maintaining stable performance (removal rate > 90%), which reduces annual material replacement needs by over 80% compared to single-use catalysts and minimizes waste disposal costs. A preliminary cost-benefit analysis suggests that CM-AA can lower operating expenses by approximately 25–40% in continuous flow systems compared to existing advanced oxidation processes. Finally, activated alumina is a well-established catalyst support widely used in industrial water treatment. The CM-AA preparation process is compatible with existing water treatment infrastructure, requiring no large-scale equipment modifications. This substantially reduces initial integration costs—by an estimated 60–70% compared to technologies requiring new reactor designs—and facilitates seamless integration into current ozonation or advanced oxidation processes, thereby shortening the return on investment period. This combination of low capital investment, reduced operating costs, and high process efficiency underscores its strong potential for large-scale application.

Environmental benefits of CM-AA application

The implementation of CM-AA demonstrates multiple positive environmental impacts, particularly in reducing DBPs: The first is the effective removal of DBPsFP. CM-AA achieves highly efficient HA removal (95.5%) through its synergistic adsorption-ozonation mechanism, significantly mitigating DBPs formation risks at the source. This effectively reduces the generation of harmful DBPs in water treatment processes. Secondly, CM-AA has Green Chemistry Characteristics. The loaded components (Mn, Ce) in CM-AA exist as stable oxides, with no detectable metal leaching observed in experiments, thereby preventing secondary heavy metal contamination. The developed low-temperature reaction conditions (20 °C) and short treatment duration (20 min) substantially reduce energy requirements compared to conventional high-temperature/high-pressure processes, resulting in superior energy efficiency and environmental friendliness. Finally, CM-AA conforms to the principle of circular economy. CM-AA exhibits excellent cycling stability (maintaining performance after 12 regeneration cycles), significantly reducing solid waste generation. The calcination regeneration process (350 °C) features controllable energy consumption and emits no toxic gases. Figure 10 summarizes the detailed process of material preparation mentioned in the article and the characterization methods and related results, and also summarizes the application of the optimal modified material CM-AA.

Conclusions

In this study, a cerium-manganese modified material was successfully synthesized via the impregnation method, with its optimal preparation conditions determined through orthogonal experimental optimization. Experimental results confirmed successful loading of Mn and Ce onto the CM-AA surface, and the material demonstrated excellent recyclable stability—after 12 consecutive cycles, the removal efficiency of the target pollutant remained above 90%. In the advanced oxidation process (AOP), HA removal efficacy of CM-AA coupled with H₂O₂ and O₃ was significantly superior to that of CM-AA coupled with H₂O₂ or O₃ alone. Specifically, under optimal conditions (initial HA concentration: 10 mg/L; H₂O₂ dosage: 10 mg/L; CM-AA dosage: 4 mg/L; ozone reaction duration: 20 min), the HA removal efficiency attained 95.5%. This outcome indicates that CM-AA holds promising application prospects in mitigating HA concentration fluctuations in drinking water sources, and can synergize with existing water treatment facilities to achieve efficient and rapid HA removal, thereby providing technical support for ensuring drinking water safety.

However, this study has certain limitations. Currently, experiments have been conducted solely in a single HA system under relatively idealized conditions. Actual water matrices are more complex, containing various coexisting ions, natural organic matter, microorganisms, and other components. For instance, carbonate, sulfate, and chloride ions are prevalent in surface water, while industrial wastewater may contain heavy metals, surfactants, and high-concentration salts. These components could interfere with the adsorption behavior and catalytic activity of CM-AA. Additionally, the stability of the material under dynamic water quality conditions (e.g., pH fluctuations, temperature variations, or high-salt environments) has not been systematically evaluated, and its applicability in real water bodies requires further verification. Furthermore, the current research lacks investigations into large-scale preparation processes, cost-benefit analysis, and integration efficiency with existing water treatment workflows, which may restrict its practical application and promotion.

Based on these limitations, future research should prioritize the following aspects: Firstly, systematic evaluation of CM-AA’s treatment performance in diverse actual water matrices (e.g., surface water, groundwater, industrial wastewater) is essential, along with investigations into the inhibitory or enhancing effects of typical coexisting substances on its catalytic-adsorption processes, to clarify its applicable water quality range and boundary conditions. Secondly, pilot-scale trials and on-site application studies should be advanced to optimize large-scale synthesis pathways, analyze long-term operational stability and economic feasibility, and verify its engineering viability. Moreover, expanding the material’s removal performance to other typical pollutants (e.g., pesticide residues, endocrine-disrupting chemicals) can broaden its application scenarios. Simultaneously, the regeneration process of CM-AA should be further optimized to reduce operational costs, and the reaction mechanism of the CM-AA/H₂O₂/O₃ synergistic system should be thoroughly explored to provide theoretical support for material modification and process parameter optimization.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Q.K., upon reasonable request.

References

Xue, P. P., Liu, J. G. & Leng, S. G. Research progress of DBPs precursors removal by advanced ozonation Processes(AOPs). Water Purif. Technol. 41, 9–15 (2022).

Li, Y. & Wu, D. N. The experiment of the complexing remove of some metal iones by the humic substances. J. Qingdao Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 2, 88–92 (1996).

Bai, R. & Zhang, X. Polypyrrole-Coated granules for humic acid removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 243, 52–60 (2001).

Bove, F. J. et al. Public drinking water contamination and birth outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 141, 850–862 (1995).

Lin, H. C. & Wang, G. S. Effects of UV/H2O2 on NOM fractionation and corresponding DBPs formation. Desalination 270, 221–226 (2011).

Ding, Y. H. Study on degradation of humic acids by O3/UV/GAC process. Humic Acid. 37, 19–22 (2012).

Peng, L., Liu, J. L. & Yang, Z. S. Comparative study on spectral detection of humic acid effect of Ozone treatment in drinking water. J. Green. Sci. Technol. 3, 131–133 (2013).

Wang, F. F., Li, L. L., Wu, C. S., Lin, Z. B. & Zhu, S. Preparation of Mn doped TiO2 nanomaterials and their visible-light photocatalytic performance for degradation of humic acid. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 11, 4594–4600 (2017).

Cui, Y. Y. Adsorption of Humic Acid on Magnetic CarbonNanotubesdecorated with Ca/Mn from Water and Regeneration (Guangdong University of Technology, 2023).

Alhooshani, K. R. Adsorption of chlorinated organic compounds from water with cerium oxide-activated carbon composite. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 2585–2596 (2019).

Li, L. S., Xie, Y. H., Pan, Z. Q. & Xue, Y. Mineralization of humic acid in water by catalytic ozonation with Ce-MCM-41. J. South. China Normal Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 49, 73–79 (2017).

Li, M., Chen, W. M., Jiang, G. B. & Zhang, A. P. Ozonation treatment of high humic acid wastewater catalized by Fe-Ce/GAC. Acta Sci. Circum. 37, 3409–3418 (2017).

Einaga, H. & Futamura, S. Catalytic oxidation of benzene with Ozone over alumina-supported manganese oxides. J. Catal. 227, 304–312 (2004).

Darujati, A. R. S. & Thomson, W. J. Kinetic study of a ceria-promoted Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst in dry-methane reforming. Chem. Eng. Sci. 61, 4309–4315 (2006).

Ogawa, Y., Toba, M. & Yoshimura, Y. Effect of lanthanum promotion on the structural and catalytic properties of nickel-molybdenum/alumina catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 246, 213–225 (2003).

Guo, X. K., Li, S. W. & Chen, Y. W. Preparation and catalytic performance of Cu5%/Ce0.6Mn0.4Ca0.0802-λ. J. Shantou Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 27, 42–51 (2012).

Yu, Q. Q. et al. Preparation of ceria-alumina and catalytic activity of gold catalyst supported on ceria-alumina for water gas shift reaction. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 38, 223–229 (2010).

Prakash, A. S., Shivakumara, C. & Hegde, M. S. Single step Preparation of CeO2/CeAlO3/γ-Al2O3 by solution combustion method: phase evolution, thermal stability and surface modification. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B. 139, 55–61 (2007).

Trovarelli, A., Deleitenburg, C., Dolcetti, G. & Lorca, J. L. CO2 methanation under transient and Steady-State conditions over Rh/CeO2 and CeO2-Promoted Rh/SiO2: the role of surface and bulk ceria. J. Catal. 151, 111–124 (1995).

Wu, J. J., Li, X. B., Tian, J. & Tong, G. Effect of entering temperatures and time of constant temperature furnace anneal on performance of formed cokes. J. China Coal Soc. 35, 190–193 (2010).

Wang, S. & Lu, G. Q. (eds) (Max) Role of CeO2 in Ni/CeO2–Al2O3 catalysts for carbon dioxide reforming of methane. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 19, 267–277 (1998).

Srisiriwat, N., Therdthianwong, S. & Therdthianwong, A. Oxidative steam reforming of ethanol over Ni/Al2O3 catalysts promoted by CeO2, ZrO2 and CeO2–ZrO2. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 34, 2224–2234 (2009).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Catalytic mechanism of nanocrystalline and amorphous matrix in Fe-Based microwires for advanced oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2425912 (2025).

Guo, J. et al. Control of water for high-yield and low-cost sustainable electrochemical synthesis of uniform monolayer graphene oxide. Nat. Commun. 16, 727 (2025).

Ghanbarizadeh, P. et al. Performance enhancement of specific adsorbents for hardness reduction of drinking water and groundwater. Water 14, 2749 (2022).

Vijayalakshmi, R. P., Jasra, R. V. & Bhat, S. G. T. Modification Texture Surf. Basicity γ-alumina Chem. Treatment 113, 613–622 (1998).

Xi, Y. Y. Research on the efficiency and mechanism of manganese-modified activated carbon in the adsorption of malachite green. (Shandong Jianzhu University 1, 2023).

Wen, L., Jian, H., Niu, L. K. & Wang, L. J. Experimental research on oxidation of formaldehyde by potassium permanganate supported on alumina. Refrig. Air Conditioning. 34, 15–20 (2020).

Yuan, X. H. et al. Preparation of A supported Mn-Ce oxides SCR denitration catalyst. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 48, 38–40 (2020).

Ke, P. Catalvst of Mn-Cu-Ce Composite Ovides Loaded ZSM-5 Molecualr Sieve for Oyone Exhaust Decomposition. (Zhejiang University, (2021).

Cao, C. C. The study on treating phenol wastewater by modified granular activated carbon with potassium permanganate. (Dalian Maritime University 9, 2010).

Huang, H. D. & Li, Y. Y. Study on the thermal decomposition process of potassium permanganate. Chem. Educ. 30, 65–66 (2009).

Hao, S. M. et al. K2Mn4O8/Reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for excellent lithium storage and adsorption of lead ions. Chem. – Eur. J. 22, 3397–3404 (2016).

He, S. Y., Zhao, L. Y. & Liu, Y. L. Study on the thermal decomposition mechanism of cerium nitrate (III) hydrate. Chin. Rare Earths. 4, 33–37 (1988).

Chen, T. et al. Adsorption properties of pine needle Carbon-Cerium materials for Rhodamine B. Industrial Saf. Environ. Prot. 47, 90–93 (2021).

Lyu, C., Yang, X., Zhang, S., Zhang, Q. & Su, X. Preparation and performance of manganese-oxide-coated zeolite for the removal of manganese-contamination in groundwater. Environ. Technol. 40, 878–887 (2019).

Jin, B. F. Study on the macroporous Al2O3-supported Au-based nanoparticle catalysts for the oxidative removal of soot. (China Univ. Petroleum (Beijing). 2, 2017).

Liu, H. F. Preparation of manganese-based catalysts and their electrocatalytic water oxidation performance. (Shaanxi Normal University 12, 2018).

Zhang, J. J. Preparation at room temperature and characterization of Ce-Mn conversion coating on al alloy. (South China Univ. Technology. 11, 2010).

Li, W. et al. Room-temperature synthesis of MIL-100(Fe) and its adsorption performance for fluoride removal from water. Colloids Surf., A. 624, 126791 (2021).

Octave, L. Chemical Reaction Engineering (Wiley, 1998).

Fogler, H. S. Elements of chemical reaction engineering. (Pearson Boston Columb. Indianapolis 5, 2016).

Chen, H., Koopal, L. K., Xiong, J., Avena, M. & Tan, W. Mechanisms of soil humic acid adsorption onto montmorillonite and kaolinite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 504, 457–467 (2017).

Ho, Y. S. & McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 34, 451–465 (1999).

Gorzin, F. & Abadi, M. M. B. R. Adsorption of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution by adsorbent prepared from paper mill sludge: kinetics and thermodynamics studies. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 36, 149–169 (2018).

B, H. D., P, E. & J, G. J. & Kinetics of irreversible adsorption with diffusion: application to biomolecule immobilization. Langmuir 18, 1770–1776 (2002).

Yang, R., Tang, Y., Li, J., Fei, C. & Wang, B. Study the adsorption of nitrate in water by Cobalt⁃Iron layered Bimetal⁃Loaded Biochar. J. Petrochemical Universities. 37, 16 (2024).

Foo, K. Y. & Hameed, B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 2–10 (2010).

Al-Degs, Y. Effect of carbon surface chemistry on the removal of reactive dyes from textile effluent. Water Res. 34, 927 (2000).

Nguyen, C. & Do, D. D. The Dubinin–Radushkevich equation and the underlying microscopic adsorption description. Carbon 39, 1327–1336 (2001).

Weber, T. W. & Chakravorti, R. K. Pore and solid diffusion models for fixed-bed adsorbers. AIChE J. 20, 228–238 (1974).

Langmuir, I. & THE ADSORPTION OF GASES ON PLANE SURFACES OF GLASS MICA AND PLATINUM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403 (1918).

Crini, G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 97, 1061–1085 (2006).

Oskoei, V. et al. Removal of humic acid from aqueous solution using UV/ZnO nano-photocatalysis and adsorption. J. Mol. Liq. 213, 374–380 (2016).

Chen, W. J. et al. Degradation of humic acid in water by ultraviolet photocatalysis of TiO2/GO composite nanomaterials. Environ. Eng. 38, 89–95 (2020).

Mohtar, S. S. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of humic acid using a novel visible-light active α-Fe2O3/NiS2 composite photocatalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105682 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Strong metal-support interaction critically controls Pt/CeO2-UiO terminal hydroxyl groups in HCHO oxidation at ambient temperature and low humidity. Chem. Eng. J. 522, 167727 (2025).

Putla, S. et al. MnO(x) Nanoparticle-Dispersed CeO2 nanocubes: A remarkable heteronanostructured system with unusual structural characteristics and superior catalytic performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7, 16525–16535 (2015).

Meng, L. et al. Active manganese oxide on MnOx–CeO2 catalysts for low-temperature NO oxidation: characterization and kinetics study. J. Rare Earths. 36, 142–147 (2018).

Wu, C. T. et al. MnOx/CeO2-Al2O3 monolith catalyst for high concentration hydrogen peroxide decomposition. Chin. J. Energetic Mater. 22, 148–154 (2014).

Tang, Q. H., Gong, X. M., Zhao, P. Z. & Zhao, P. Z. Selective oxidation of alcohols with molecular oxygen catalyzed by Al2O3-Supported Mn-Ce oxides. J. Henan Normal University(Natural Sci. Edition). 36, 74–78 (2008).

Wu, H. H. et al. A catalyst material for oxidative decomposition of organic matter in wastewater and its Preparation method. Chinese Patent 8, 1–8 (2023).

Liu, L., Wang, G. & Zhang, K. Study on the characteristics of hydrogen peroxide catalytic oxidation of humic acids. North. Environ. 24, 151–154 (2012).

Dong, W. Y. & Du, H. The principle of hydrogen peroxide oxidation method and the removal of organic matter. China Rural Water Hydropower. 2, 47–48 (2004).

Kosmulski, M. Surface Charging and Points of Zero Charge (CRC, 2009).

Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. VI. Update. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 426, 209–212 (2014).

Peacock, C. L. & Sherman, D. M. Crystal-chemistry of Ni in marine ferromanganese crusts and nodules. Am. Mineral. 92, 1087–1092 (2007).

Ritchie, J. D. & Perdue, E. M. Proton-binding study of standard and reference fulvic acids, humic acids, and natural organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 67, 85–96 (2003).

Tang, H., Xiao, B. & Xiao, P. Interaction of Ca2 + and soil humic acid characterized by a joint experimental platform of potentiometric titration, UV–visible spectroscopy, and fluorescence spectroscopy. Acta Geochim. 40, 300–311 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Molecular dynamics simulation of the interaction between common metal ions and humic acids. Water 12, 3200 (2020).

Frimmel, F. H., Von, W. & Stumm Chemistry of the Solid-Water Interface. Processes at the Mineral-Water and Particle-Water Interface in Natural Systems. Wiley, Chichester, X, 428 S., Broschur 32.50 £ - ISBN 0-471-57672–7. Angewandte Chemie 105, 800–800 (1993). (1992).

Buxton, G. V., Greenstock, C. L., Helman, W. P. & Ross, A. B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH/⋅O – in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 17, 513–886 (1988).

Kang, Y. Y., Liang, J. F., Jiang, C., Zhang, M. & Zhu, Y. C. Overview of adsorption experiment of rapid Small-Scale column test applied in water treatment. Water Purif. Technol. 42, 32–39 (2023).

Pelekani, C. & Snoeyink, V. L. Competitive adsorption in natural water: role of activated carbon pore size. Water Res. 33, 1209–1219 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2020BCB067).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. Z.: Writing - original draft, Methodology, R. F.: Writing - review & editing, Data curation. H. L.: Investigation, Z. L.: Project administration, J. Z.: Resources, Q. K.: Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, P., Feng, R., Li, H. et al. Synergistic catalytic ozonation of humic acid in water over activated alumina modified with cerium and manganese oxides. Sci Rep 15, 36680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20406-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20406-x