Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the impact of various light spectra on the growth, physiology, and biochemistry of two lettuce cultivars under salinity and alkalinity stress in a Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) hydroponic system. The experiment was conducted using a factorial design with a completely randomized approach. The factors considered in this study encompassed three different levels of light (supplementary red light, supplementary blue light, and ambient light), three levels of stress (10 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM NaCl, and a control without stress), and two lettuce cultivars. Light treatments were administered starting from the seedling transfer to the NFT system, while stress treatments were applied during the four-leaf stage of lettuce growth. The study observed that subjecting lettuce plants to salinity and alkalinity stress in the NFT system resulted in a decrease in various vegetative characteristics (such as shoot and root mass, root length, leaf number) as well as physiological and biochemical traits (including net photosynthesis, Fv/Fm, PI, LRWC, soluble sugars, soluble protein, and anthocyanin), photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a and b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids), and leaf nutrient concentrations (K, Fe, Mn and Zn). However, the application of blue and red light spectra proved to be beneficial, as it led to enhanced growth, improved physiological and biochemical traits, increased nutrient content, higher photosynthetic pigments, and improved photosynthetic parameters in lettuce cultivars facing salinity and alkalinity stresses. In conclusion, the findings highlight the positive impact of blue and red light spectra on lettuce plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress conditions, as observed through improved growth and various physiological and biochemical characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water quantity and quality both play crucial roles in ensuring water availability and suitability for irrigation, yet the focus on water quality is often overlooked. With the growing urban population, the demand for high-quality water for plant cultivation has become limited. In response, authorities in arid and semi-arid regions of various countries have implemented regulations aimed at reducing the utilization of high-quality water in agriculture and encouraging the use of lower-quality water sources1,2. Recognizing the significance of water quality alongside quantity is essential for sustainable agricultural practices and the efficient use of water resources.

Water alkalinity is a significant factor that strongly influences the quality of water and pH of growing media3. Key contributors to alkalinity include bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonates (CO32−), while hydroxide, borate, ammonia, organic bases, phosphates, and silicates are secondary factors4. Alkaline pH conditions result in the formation of insoluble nutrient forms, notably iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and zinc (Zn), rendering them unavailable for plant absorption5. This deficiency manifests as yellowing in young leaves due to reduced chlorophyll synthesis caused by the lack of Fe and Zn6. Bicarbonate ions also affect the uptake of macronutrients, particularly phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), and potassium (K) by plants7. In alkaline soils, a significant portion of P becomes inaccessible to plants due to the formation of metal complexes with calcium (Ca) and Mg8. The presence of bicarbonate ions increases the pH of the leaf apoplast, resulting in the stabilization of Fe3+ ions as hydroxide ions and iron phosphate before they pass through the cytoplasmic membrane9. To enhance the plant’s Fe uptake and efficiency, it is necessary to neutralize or reduce the sodium carbonate in the root environment, as the carbonate ion inside the plant is influenced by sodium carbonate9. The presence of NaHCO3 and Na2CO3 alters pH levels within cells and leads to osmotic stress, ionic stress, and ion imbalance, reducing the cell’s ability to regulate osmotic adjustment and antioxidant responses. This ultimately leads to a decrease in cell membrane integrity, root vitality, and photosynthetic efficiency7.

Salinity is a significant limiting factor in plant growth, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions where continuous evaporation and low rainfall contribute to soil salinization. This accumulation of salts can render hectares of arable land unsuitable for cultivation. Salinity adversely affects plant growth and performance in various parts of the world. As salt accumulates in the root environment, the uptake and transport of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions to plant tissues increase, resulting in reduced absorption of essential nutrients such as K, P, and other cations necessary for plant growth. Consequently, plant growth is hindered10. Plants have a protective mechanism to increase tolerance to salt stress by compartmentalizing toxic ions in vacuoles and synthesizing small compatible molecules. These molecules help maintain osmotic balance, scavenge reactive oxygen species, and protect membranes and macromolecules. However, if the exclusion of toxic ions is not balanced by beneficial ions in the cytosol, plants may need to expend excess energy on synthesizing compatible compounds, which can hinder growth and survival under continuous salt stress. As a result, most horticultural crops have low tolerance to continuous salt stress7. Plants activate antioxidant defense systems to combat oxidative stress caused by salinity, incurring high energy costs in order to support growth performance under salt stress7. Plants produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) during normal metabolism, but salt stress disrupts the balance, leading to ROS accumulation and oxidative damage. Despite their harmful effects, ROS also act as signaling molecules in response to environmental stimuli. Plants have enzymatic and non-enzymatic scavengers to alleviate ROS-induced damage under salt stress. These antioxidants help remove excess ROS and protect cellular components. Many plants show increased activity of antioxidant enzymes and accumulation of non-enzymatic antioxidants in response to salinity, which helps combat oxidative stress11. The defense mechanisms of enzymatic and non-enzymatic scavengers are crucial for plants to adapt to and cope with salt stress efficiently11. NaCl toxicity negatively impacts plant photosynthesis by disrupting various aspects of the process. Specifically, NaCl stress leads to a decline in photosynthetic rates, damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, and alterations in enzyme activities and gene expression. This results in reduced carbon assimilation and impaired electron transport, ultimately hindering the plant’s ability to convert light energy into chemical energy12. Studies have shown that under salt stress, various parameters related to photosynthesis such as net photosynthesis rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and maximal efficiency of photosystem II decline13. Both stomatal and non-stomatal factors contribute to the overall decrease in photosynthetic output in plants under salt stress14. Stomatal closure inhibits CO2 diffusion and reduces intercellular CO2 concentration, affecting photosynthesis production. Non-stomatal factors include disruptions in photosynthetic membrane proteins, thylakoid membranes, and loss of pigments15. Chlorophyll contents decrease in leaves under salt stress, with salt-tolerant varieties showing more stability compared to salt-sensitive ones. Plants employ photoprotective mechanisms to counter photoinhibition and photodamage, thereby safeguarding the photosystems. Salt-tolerant Ricinus communis exhibits higher photorespiratory activity and efficient photoprotection mechanisms, while salt-sensitive Jatropha curcas experiences biochemical limitations in photosynthesis due to decreased Rubisco activity and electron transport rates under salinity16.

Light is a critical factor in the greenhouse industry, accounting for a considerable portion of production costs17. This is particularly important in regions with fluctuating natural day length and insufficient light for optimal plant growth. In layer crops, supplementary lighting is crucial. Currently, high pressure sodium (HPS) lamps are widely used in greenhouses, but they generate significant amounts of radiant heat and operate at high temperatures (over 200 °C)18. Consequently, HPS lamps cannot be positioned too close to plants, and adequate ventilation is necessary to prevent excessive temperature increases. To address this issue and enhance product quality, a promising solution is the use of light emitting diodes (LEDs), which have garnered considerable attention19. LEDs offer energy-efficiency, technical advantages over traditional light sources, and the potential to fulfill various lighting roles in greenhouse settings. Unlike fragile filaments, electrodes, or lamps filled with pressurized gases, LEDs are durable and provide superior performance20. Supplemental light can have a positive impact on mitigating plant stresses4. Insufficient light is a common stressor for indoor plants or plants grown in shaded areas21. Supplemental light can provide the necessary light intensity and duration to support plant growth and development22. Supplemental light, particularly specific light spectra like blue and red, can enhance the salt tolerance of plants4. It promotes physiological and biochemical changes in plants, such as the accumulation of compatible solutes and the regulation of ion transport, enabling better adaptation to salinity stress23. It is important to note that the effectiveness of supplemental light in mitigating plant stresses can vary depending on the plant species, the specific stressor, and the light spectra used4. Optimal light intensity, duration, and spectral composition should be carefully adjusted according to the specific stress conditions and plant requirements24.

This research uniquely explores how supplemental red and blue LED lighting mitigates the negative effects of both salinity and alkalinity stress on lettuce in a hydroponic system. It fills a knowledge gap by combining light spectrum and dual stress analysis on growth, physiology, and nutrient uptake. The use of an NFT hydroponic setup underlines the potential for real-world, soilless crop production applications, especially where water quality issues (salinity/alkalinity) are common. The manuscript fills a significant gap by elucidating the influence of supplemental spectra on plant pigment composition, color parameters (hue, chroma, *a, *b), and stress-related biochemical markers under stress conditions—knowledge that was previously sparse, especially for consumer-relevant traits like leaf color and nutritional quality. It also addresses the impact on leaf color and biochemical markers, important for crop quality. Overall, it provides practical insights for improving lettuce resilience in resource-limited, stressed environments.

Given the varied reactions of plants to LED lighting and the increasing scarcity and quality decline of water resources, particularly in terms of salinity and alkalinity, implementing proper management techniques becomes crucial to enhance both the quantity and quality of the lettuce crop. Therefore, the primary objective of this research is to evaluate how lettuce performs when exposed to different spectrums of LED lighting under the challenging conditions of salinity and alkalinity within the hydroponic NFT system.

Materials and methods

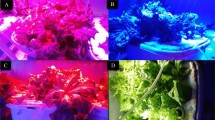

Plant material and growth conditions

The experimental project utilized two cultivars of lettuce, Lollo bionda (produced by Organic Farm Company) and New Red Fire 11 (produced by Takumi Japan). Seeds were purchased from Sepahan Rooyesh (Sepahan Rooyesh Seed Co., Isfahan, Iran). The sources of seeds were Rijk Zwaan (Rijk Zwaan Zaadteelt und Zaadhandel B.V., De Lier, The Netherlands) and Takii Seed (Takii Seed Co., Japan) companies. Lollo bionda lettuce is characterized by its early maturity, green color, curled leaves, firm texture, and sweet taste. New Red Fire lettuce, on the other hand, features a red-brown color, early ripening, sweetness, and twisting leaves. The project was conducted in the greenhouse of the Department of Horticultural Science, Vali-E-Asr University, Rafsanjan, Iran. The greenhouse maintained a temperature range of 24 ± 3 °C during the day and 18 ± 3 °C at night, with a photoperiod of 11 h of light (115 µmol m−2 s−1 intensity) and 13 h of darkness, along with a relative humidity of 50–60%. The study aimed to investigate the effects of different supplementary light spectrums on the growth, physiological and biochemical characteristics of the two lettuce cultivars under salinity and alkalinity stresses in the nutrient solution of nutrient film technique (NFT). The experiment followed a factorial design and employed a complete randomized design with four replications. The factors considered were the three supplementary light levels (100% red light, 100% blue light, and ambient greenhouse light), three stress levels (10 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM NaCl, and control), and two lettuce cultivars. These light treatments were initiated upon transplanting in the NFT system, while the stress treatments were applied at the four-leaf stage of lettuce development. During the experiment, the seedlings were transferred to small mesh plastic pots filled with perlite and placed in the openings of the NFT hydroponic system. The modified Resh nutrient solution (Table 1) was used for the irrigation of the plants after they were transferred to the NFT system. Salinity treatment was introduced 4 days after transplanting by adding sodium chloride salt (Merck, Germany) to the nutrient solution, while alkalinity treatment was implemented by adding sodium bicarbonate. The red and blue LED lamps were positioned horizontally, 20 cm above the seedlings, and separated using thick aluminum foil to ensure the separation of each light level. The NFT system consisted of three separate systems, each comprising two 2-m canal with nine culture holes spaced 20 cm apart on each channel. Each system was equipped with a 40-L tank, inside of which a water pump delivered the nutrient solution to the pipes. The nutrient solution flowed through the pipes to the end of the canal, where it entered the canal through two connecting hoses with a diameter of 1 cm. The canals were set at a slope of 1–2% to facilitate the flow of the nutrient solution. Each system featured two rows for lettuce cultivation.

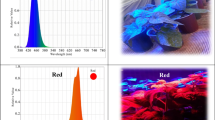

LED tubes and the light treatments

The experiment was conducted using metal structures with dimensions of 100 cm in length, 5 cm in width, and 5 cm in height. LED tubes with a power of 24 W and photon flux density (PPFD) of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 were utilized. These LED tubes were sourced from Parto Roshd Novin Company, Iran and are specifically designed for plant growth (Iran grow light, Iran). The LED tubes emitted light in different spectral ranges: monochromatic blue (B) with a peak wavelength of 460 nm and monochromatic red (R) with a peak wavelength of 660 nm (Fig. 1). Additionally, there was a treatment group that received only ambient light, without any supplemental LED lighting (Table 2). The photoperiod for the experiment consisted of 11 h of light and 13 h of darkness. The LED lighting systems were mounted directly above each plant, with a distance of 20 cm.

Vegetative growth and leaf characteristics

Upon completion of the experiment, the plants were harvested to obtain measurements. The shoot and root of the plants were carefully separated, and the samples were weighed to determine their fresh mass. Subsequently, the samples were placed in an oven set at 70 °C for 72 h to measure their dry mass. The dry mass of each sample was then recorded. The number of leaves for each treatment was determined at the end of the experiment and prior to harvest. In order to evaluate leaf area, three leaf samples were randomly collected from each treatment and their leaf area was measured using a leaf area meter (model number 202 m-CI).

Leaf pigments and leaf color parameters

To determine the levels of chlorophyll and carotenoids in a leaf sample, the frozen leaves (0.25 g) are crushed using liquid nitrogen in a mortar. Next, 80% acetone (20 mL) is added to the sample, which is then centrifuged at 4800 rpm for 20 min. The resulting supernatant is analyzed using a spectrophotometer to measure its absorbance at specific wavelengths (470 nm, 647 nm, and 663 nm). Finally, the concentrations of chlorophyll and carotenoids are calculated using Lichtenthaler’s method25.

Leaf surface color was analyzed using a calorimeter (Chroma Meter CR-400C, Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The colorimeter recorded CIE L*a*b* coordinates, where L* represents lightness, a* indicates the position on the green–red axis (− greenness to + redness), and b* represents the position on the blue-yellow axis (− blueness to + yellowness)26. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the color, numerical values of a* and b* were converted into additional parameters. The hue angle (H°) was calculated as the inverse tangent of b*/a* (H° = tan−1 b∗/a∗), providing information about the dominant color hue. Chroma, denoted as Chroma = (a*2 + b*2)1/2, represented the overall color saturation or intensity. In order to obtain accurate measurements, three opposite points from the surface of the leaf were read using the colorimeter. This approach ensured a representative assessment of the leaf’s color properties. By utilizing the colorimeter to measure CIE L*a*b* coordinates, including the derived parameters of hue angle and chroma, researchers were able to gain detailed insights into the color characteristics of the leaf surfaces. This information is valuable for understanding plant physiology, assessing ripeness, and studying the effects of environmental factors on leaf coloration.

Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence

Plant gas exchange parameters were measured using a portable photosynthesis system (ADC BioScientific Ltd, Hoddesdon, UK) 60 days after planting. The parameters included net CO2 assimilation rate (A, μmol CO2 m−2 s−1), water-use efficiency (iWUE, μmol CO2 mol−1 H2O), stomatal conductance (gs, mol H2O m−2 s−1), transpiration (E, mmol H2O m−2 s−1), sub-stomatal CO2 concentration (Ci, μmol CO2 mol−1), and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (A/Ci). Measurements were conducted 30 days after applying the treatments and when the leaves were mature, specifically around 9:00 AM and 12:00 AM, on fully expanded leaves4. The leaves were placed in the cuvette for 3 min, and then the measurement was done27. The air temperature and light intensity in cuvette during measurements were ambient. The CO2 concentration was 400 ppm and molar flow of air was 200 mol s−128.

At the end of the growing period, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were measured using a portable photosynthetic efficiency analyzer (PEA) manufactured by Hansatech Inc. The PEA enabled the assessment of various parameters related to the photosynthetic activity of the plants. The measured parameters included Variable fluorescence (Fv), Maximal fluorescence of the dark-adapted state (Fm), Minimal fluorescence yield of the dark-adapted state (Fo), Maximal quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) and Performance index (PI). The PI is a parameter used to assess the efficiency of photosynthetic electron transport within the photosystem II (PSII) complex and the overall functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus. It provides a quantitative measure of the functional status of the photosynthetic apparatus by evaluating various aspects of the electron transport chain. It is sensitive indicator of stress, such as drought or high salt concentrations, and can be used to compare primary photochemical reactions and electron transport29. The PI is used to analyze and monitor the impact of various environmental stressors, such as high light levels, temperature extremes, or nutrient deficiencies, on the photosynthetic performance of plants. Changes in the PI value can indicate alterations in the efficiency of light energy absorption, conversion, and utilization within the photosynthetic apparatus. By measuring the PI, researchers can gain insights into the overall health and functioning of the photosynthetic system under different conditions and stressors.

Fully expanded leaves were collected, tagged, and allowed to undergo a 15-min dark adaptation period before measurements. The leaves were then exposed to red light, and fluorescence signals were recorded within a specific time range. The recorded fluorescence transients were analyzed using the equations of the JIP-test30, providing valuable insights into the dynamic response and overall photosynthetic performance of the plants to light stimuli31.

Antioxidant capacity

The radical scavenging activity in plant tissue extracts was determined using the method described by Barros et al.32. The reduction of DPPH radicals was measured by assessing the absorption at 517 nm. The percentage of DPPH discoloration, representing the radical scavenging activity, was calculated using the following equation:

where A0 is the absorbance of the DPPH solution and A1 is the absorbance of the sample.

Malondialdehyde concentration

In accordance with the method described by Health and Packer (1968), one g of fresh leaf tissue was weighed and thoroughly ground in a porcelain mortar with 5 mL of a 0.1% trichloroacetic acid solution. The resulting extract was then subjected to centrifugation for 5 min. To 1 mL of the supernatant obtained from the centrifugation, 4.5 mL of a 20% trichloroacetic acid solution containing 5 g of Thiobarbituric acid per 100 g was added. The resulting mixture was once again centrifuged at 4000 rpm (1000g) for 10 min. Subsequently, the absorbance intensity of the solution was measured at a wavelength of 532 nm using a Microplate Reader device (Epoch model, manufactured by American Biotech).

Total phenolic compounds

To measure the total phenolic compounds, the method described by Matta et al.33 was employed. In this method, 0.1 g of leaf tissue was boiled in 10 mL of 80% ethanol, and the resulting extract was subjected to centrifugation at 3500 rpm. The concentration of total phenolic compounds was determined using a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 640 nm. To establish a standard curve, catechol was utilized, enabling the quantification of phenolic compounds in the leaf tissue extract with accuracy and precision.

Anthocyanin measurement

The content of anthocyanin in the plant samples was determined following the method described by Nogués and Baker34. Fresh leaf tissue (1 g) was homogenized in 10 mL of acidic methanol and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 3500 rpm. The absorbance of the resulting samples was measured at wavelengths of 530 nm and 657 nm. These measurements allowed for the quantification of anthocyanin content, providing valuable information about the presence and abundance of these pigments in the leaf tissue.

Soluble proteins

Protein measurement was conducted using the method developed by Bradford et al.35. In this analysis, 0.1 mL of the protein extract was mixed with 5 mL of the Bradford reagent in test tubes. The mixture was gently vortexed and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 595 nm, employing bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Proline

Free proline contents in lettuce leaf were determined according to Bates et al.36.

Total soluble sugars

Soluble sugars were determined using the method described by Irigoyen et al.37. To perform this analysis, 0.1 mL of the ethanol extract (which was prepared similarly to the proline extraction) was combined with 3 mL of freshly prepared anthrone solution (200 mg of anthrone in 100 mL of 72% sulfuric acid). The mixture was then incubated in a hot water bath for 10 min. After cooling, the absorbance of the samples was measured at a wavelength of 625 nm. The standard curve was made with glucose in a range of 0–50 μg. The total soluble sugars (mg g−1 FW) were quantified using glucose as standard.

Leaf relative water content (LRWC)

For the determination of LRWC, fresh leaves were utilized. One fully expanded leaf was selected from each plant and a 5 mm diameter leaf disk was obtained from it. The prepared leaf discs were initially weighed to measure their fresh mass (FM). Subsequently, the leaf discs were placed on distilled water in a petri dish, allowing them to float, and they were incubated at normal room temperature. After 4 h, any excess water on the discs was blotted, and the discs were then weighed to determine their turgor mass (TM). The samples were subsequently dried at 70 °C for 24 h, and their dry mass (DM) was obtained. The relative water content was calculated using the following equation:

Elemental analysis

To analyze the leaf samples, the dried samples were subjected to a temperature of 550 °C for a duration of 5 h. During this process, the leaf samples were converted into ashes. The resulting ashes were then dissolved in 5 mL of 2 N HCl, followed by the addition of 50 mL of distilled water. The concentrations of Na and K in the leaf samples were measured using flame photometry (Jenway PFP7 model). Additionally, the concentrations of Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu in the leaf samples were measured using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (T80 UV/VIS model manufactured in China). As for the Ca and Mg concentration, it was measured through the process of EDTA titration38.

Experimental design and data analysis

This experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design, with two factors analyzed as a factorial design and each treatment replicated three times. The experimental units consisted of individual plants grown in NFT systems. Data analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, http://www.sas.com). For statistical analysis, a two-way ANOVA model was employed to determine significant treatment effects. Subsequently, significant mean differences (p < 0.05) were calculated using the Duncan test as a post hoc analysis to identify distinct treatment groups. Pairwise multiple comparisons and range tests were conducted to determine which means differed from one another and to identify homogeneous subsets within the data. The graphs representing the data were created using Microsoft Excel 2016. Correlation analysis, Polar heatmap with circular dendrogram, and k-means clustering were performed using Origin2024.

Results

Vegetative growth

Significant improvements in shoot and root fresh and dry mass were observed in both lettuce cultivars when exposed to blue and red light spectrums, irrespective of the presence of salinity and alkalinity stress. In contrast, the application of salinity and alkalinity stress led to a substantial reduction in shoot and root fresh and dry mass compared to the control treatment (Table 3). Furthermore, the negative impact of salinity and alkalinity stress on the number of leaves, leaf area, and root length of both lettuce cultivars was evident when compared to the control treatment. However, the utilization of blue and red light spectrums, regardless of the presence of salinity and alkalinity stress, resulted in a significant improvement in the number of leaves, leaf area, and root length for both lettuce cultivars. In terms of vegetative growth parameters, the NRF11 cultivar outperformed the LB cultivar. The highest vegetative growth parameters were observed under non-stress conditions, particularly in the NRF11 cultivar when exposed to red spectra. Under alkalinity stress conditions and in the absence of supplemental light, the LB cultivar exhibited the most inhibited vegetative growth parameters compared to other cultivars.

Photosynthetic pigments and leaf color indices

Salinity and alkalinity stress had a detrimental impact on the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids in lettuce leaves, resulting in decreased levels compared to the control treatment. However, when lettuce cultivars were exposed to blue and red light spectrums in conjunction with alkalinity and salinity stress conditions, a significant increase in these traits was observed (Table 4). Notably, the effect of blue light in augmenting pigment content under the conditions of salinity and alkalinity stress was more pronounced in both lettuce cultivars than the effect of red light.

The findings revealed that both salt and bicarbonate stress led to a decrease in the a* index when compared to the control treatment. However, when lettuce cultivars were subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress conditions along with blue and red light spectrums, there was an increase in the a* index (Table 4). The highest a* index was observed under non-stress conditions, with NRF11 and LB cultivars responding most favorably to red and blue light spectrums, respectively. Moreover, both lettuce cultivars exhibited an increase in the b* index under salinity and alkalinity stress conditions, surpassing the values observed in the control treatment. The application of blue and red light spectrums in the presence of salinity and alkalinity stress further amplified the b* index (Table 4). Notably, the NRF11 cultivar displayed the highest b* index when exposed to the interaction of red light spectrum and alkalinity stress. Furthermore, salinity and alkalinity stress led to an increase in the chroma index compared to the control treatment, and the utilization of blue and red light spectrums further enhanced the chroma index (Table 4).

Photosynthetic properties

Under ambient light conditions, the application of salinity stress resulted in a reduction of net photosynthesis in both LB and NRF11 lettuce cultivars, as compared to the control treatment (Table 5). However, when red and blue supplemental light was provided, the photosynthesis rate increased in both stressed and non-stressed conditions. In the case of the LB cultivar, alkalinity stress only caused a decrease in photosynthesis rate under ambient light conditions. Conversely, in the NRF11 cultivar, alkalinity stress led to a reduction in photosynthesis rate under both red and blue light conditions. Overall, these findings highlight the beneficial effects of red and blue supplemental light in mitigating the negative impacts of salinity stress on lettuce photosynthesis. Furthermore, the response to alkalinity stress varied between the LB and NRF11 cultivars, suggesting genotype-specific differences in their tolerance mechanisms. The salinity stress treatment of the nutrient solution, under red and blue lights condition, resulted in an increase in the intracellular concentration of CO2 under the leaf stomata of both LB and NRF11 lettuce cultivars, as compared to the control treatment (Table 5). Conversely, the alkalinity stress treatment only led to a decrease in the intracellular concentration of CO2 in the NRF11 cultivar, specifically when exposed to red light.

Under ambient light conditions, the transpiration rate of the LB cultivar remained unaffected by both salinity and alkalinity stress, while the NRF11 cultivar exhibited a decrease in transpiration rate under both stressors (Table 5). In the red and blue light conditions, the NRF11 cultivar experienced a decrease in transpiration rate due to salinity treatment, whereas the LB cultivar demonstrated an increase in transpiration rate under the same conditions. Additionally, in the red and blue light conditions, the LB cultivar showed an increase in transpiration rate when subjected to alkalinity stress. Notably, the NRF11 cultivar treated with red light exhibited the highest transpiration rate among all treatments in the absence of stress.

Under ambient light conditions, both cultivars exhibited a decrease in stomatal conductance due to salinity and alkalinity stress (Table 5). In the LB cultivar treated with red light, neither salinity nor alkalinity had any significant effect on stomatal conductance. However, in the blue light condition, both salinity and alkalinity stresses led to a decrease in stomatal conductance. On the other hand, in the NRF11 cultivar treated with red light, both salinity and alkalinity stress caused a decrease in stomatal conductance. In the blue light condition, only salinity stress resulted in a decrease in stomatal conductance.

Under ambient light conditions, salinity and alkalinity stresses were found to decrease stomatal resistance in the LB cultivar compared to the control (Table 5). However, these stresses had no significant effect on stomatal resistance in the other light conditions for both cultivars. Notably, in the absence of stress, the presence of blue light led to a decrease in stomatal resistance in both cultivars.

Under ambient light conditions, both salinity and alkalinity stresses were found to decrease the instantaneous carboxylation efficiency in the LB cultivar, whereas only salinity stress affected this trait in the NRF11 cultivar (Table 5). Conversely, in the red and blue light treated LB cultivar, the instantaneous carboxylation efficiency decreased solely due to salinity stress. Under red and blue light conditions, the NRF11 cultivar displayed lower instantaneous carboxylation efficiency specifically under alkalinity stress conditions. Notably, the red light treated NRF11 cultivar exhibited the highest instantaneous carboxylation efficiency among all treatments in the absence of stress.

The NRF11 cultivar exhibited a decrease in instantaneous intrinsic water-use efficiency under alkalinity stress in all light conditions, whereas salinity stress only had an adverse effect on instantaneous intrinsic water-use efficiency under ambient light conditions (Table 5). In the LB cultivar, salinity stress resulted in a decrease in instantaneous intrinsic water-use efficiency across all light conditions, while alkalinity stress only had a detrimental effect on instantaneous intrinsic water-use efficiency under blue light conditions. Notably, the blue light treated LB cultivar displayed the highest instantaneous intrinsic water-use efficiency among all treatments in the absence of stress.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

In the NRF11 cultivar, alkalinity stress led to a decrease in Fv/Fm under red and blue light conditions, while salinity stress only had an adverse effect on Fv/Fm under red light conditions (Table 6). In the LB cultivar, alkalinity stress resulted in a decrease in Fv/Fm under ambient and red light conditions, while salinity stress only had an adverse effect on Fv/Fm under ambient light conditions. Notably, in both cultivars, the highest Fv/Fm values were observed in the non-stress conditions. In the NRF11 cultivar, salinity and alkalinity stresses led to a decrease in PI (performance index) under red and ambient light conditions. Additionally, in the blue light condition, only alkalinity stress resulted in a decrease in this trait (Table 6). On the other hand, in the LB cultivar, both salinity and alkalinity stresses caused a decrease in PI when exposed to blue light. However, under ambient and red light conditions, the PI index decreased solely due to alkalinity stress.

Antioxidant capacity

The results revealed that both salinity and alkalinity stress conditions led to a decrease in the antioxidant capacity of both lettuce cultivars when compared to the control treatment. However, it was observed that the utilization of blue and red light spectrums under salinity and alkalinity stress conditions enhanced the antioxidant capacity in both lettuce cultivars (Table 6).

Malondialdehyde

The findings indicated that the application of salinity and alkalinity stress to both LB and NRF11 lettuce cultivars resulted in an elevation of malondialdehyde content when compared to the control treatment. Conversely, the utilization of blue and red light spectra exhibited a mitigating effect on malondialdehyde levels in both lettuce cultivars (Table 6).

The phenolic compounds

The LB cultivar exhibited an increase in the phenolic compounds of its leaves when subjected to alkalinity stress and supplemental lights, as compared to the control treatment (Table 6). In contrast, the NRF11 cultivar did not show any significant changes in phenolic compounds under the same conditions.

Anthocyanin

The results indicated that exposure to salinity and alkalinity stress conditions led to a reduction in leaf anthocyanin concentration in both lettuce cultivars, relative to the control treatment. However, the application of blue and red light spectrums demonstrated a positive impact on anthocyanin concentration in both lettuce cultivars (Table 6). Notably, the NRF11 cultivar exhibited the highest anthocyanin concentration under unstressed conditions when exposed to blue light.

Protein

In Table 7, it was observed that the protein concentration in the NRF11 cultivar experienced a decrease under both salinity stress and alkalinity stress across all light conditions. Conversely, the LB cultivar did not show any significant effect on protein concentration in response to either stress.

Proline

Under ambient light conditions, the proline content of lettuce cultivars subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress increased significantly compared to the control treatment. However, when blue and red light spectra were applied during salinity and alkalinity stress, a decrease in the accumulation of the proline was observed in both NRF11 and LB lettuce cultivars (Table 7).

Total soluble sugars

The influence of alkalinity stress on total soluble sugars in two cultivars of lettuce was examined, revealing interesting findings. The NRF11 cultivar demonstrated an increase in total soluble sugars when subjected to red light spectrums, while blue light resulted in a decrease compared to the control treatment (Table 7). However, the LB cultivar showed no significant changes in total soluble sugars with the addition of supplemental light.

Relative leaf water content

A comparative analysis of the average data revealed that under ambient light conditions, both salinity stress and alkalinity stress led to a decrease in the relative water content (RWC) of the two lettuce cultivars, as presented in Table 7. In the NRF11 cultivar subjected to red light treatment, both stresses resulted in a decrease in LRWC. On the other hand, for the same NRF11 cultivar under blue light conditions, only alkalinity stress exhibited a decrease in LRWC. For the LB cultivar treated with blue light, both stresses caused a reduction in LRWC. However, when exposed to red light, only alkalinity stress led to a decrease in LRWC.

Nutrient elements

Under ambient light conditions, both salinity and alkalinity stresses resulted in a decrease in K concentration in both cultivars. In the blue light condition, these stresses had no effect on K concentration in the NRF11 cultivar, while in the LB cultivar, only alkalinity stress caused a decrease in K (Table 7). Conversely, in the red light condition, leaf K concentration in both cultivars decreased solely due to alkalinity stress, with salinity having no significant effect on K concentration. The variance analysis of the research data revealed that leaf P content was not significantly influenced by cultivar, stress, light spectrum, or the interaction between these factors (data not shown). The study found that the concentration of Ca and Mg remained unaffected by both stresses and light spectra. However, it was observed that the LB cultivar had a higher concentration of Ca and Mg than the NRF11 cultivar (Figs. 2 and 3). Similarly, the concentration of Na was not influenced by stresses and light spectra. Nevertheless, the NRF11 cultivar exhibited a higher concentration of Na compared to the LB cultivar, as indicated in Fig. 4. Figure 5 demonstrates that the concentration of Fe was found to decrease under salinity and alkalinity stresses. In Fig. 6, it was observed that the NRF11 cultivar displayed an increase in Fe concentration with red light treatment, while no significant effect was seen in the LB cultivar. Blue light, had no impact on Fe concentration in either cultivar (Fig. 6). Moving on to Mn concentration, in the NRF11 cultivar, it was found to decrease under alkalinity and salinity stresses regardless of the light conditions (Table 7). Conversely, in the LB cultivar, Mn concentration decreased under alkalinity and salinity stresses in both red and ambient light conditions and only under alkalinity stress in blue light conditions. The concentration of Zn, decreased under salinity and alkalinity stresses in both cultivars (Figs. 7 and 8). However, red light treatment led to an increase in Zn concentration in both NRF11 and LB cultivars (Fig. 8). It is worth noting that the analysis of variance (ANOVA) did not indicate any significant effects of cultivar, stress, light spectrum, or their interactions on Cu content (data not shown).

Effect of salinity and alkalinity stress on Fe concentration of lettuce leaves. Values are means of three replicates. Bars with different letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (Duncan test). Control (no stress), salinity (10 mM NaCl) and alkalinity (10 mM NaHCO3). Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

Effect of light spectra on leaf Fe concentration of two lettuce cultivars. Values are means of three replicates. Bars with different letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (Duncan test). Photon flux density (PPFD) 200 ± 10 µmol m−2 s−1. Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

Effect of salinity and alkalinity stress on Zn concentration of lettuce leaves. Values are means of three replicates. Bars with different letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (Duncan test). Control (no stress), salinity (10 mM NaCl) and alkalinity (10 mM NaHCO3). Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

Effect of light spectra on leaf Zn concentration of two lettuce cultivars. Values are means of three replicates. Bars with different letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 (Duncan test). Photon flux density (PPFD) 200 ± 10 µmol m−2 s−1. Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

Correlation analysis

The results of the correlation analysis, as shown in Fig. 9, revealed both significant positive and negative relationships between some measured parameters. Notably, strong positive correlations were identified between several traits, such as shoot fresh mass, root fresh mass, shoot dry mass, root dry mass, leaf number, leaf area, root length, total chlorophyll content, carotenoids, anthocyanin levels, and performance index. In contrast, malondialdehyde and proline showed a negative correlation with these traits (Fig. 9).

The heatmaps based on the Pearson correlation among all parameters examined in this study. The coefficients in each cell range from − 1 to 1, where a negative value indicates a negative correlation, a positive value indicates a positive correlation, 1 represents a perfect correlation, and 0 signifies no correlation. The color and size of the squares correspond to the strength of the correlation coefficients: red indicates a positive correlation and blue indicates a negative correlation. Darker color of the squares indicates stronger correlations. A single asterisk (*) denotes a significant correlation at p < 0.05, while a double asterisk (**) indicates a highly significant correlation at p < 0.01. Here, SFM shoot fresh mass, RFM root fresh mass, SDM shoot dry mass, RDM root dry mass, Leaf No leaf number, Chl.T total chlorophyll, a and b leaf pigments, Croma chroma, Pn net photosynthetic rate, Ci intercellular CO2 concentration, TR transpiration rate, Gs stomatal conductance, rs stomatal resistance, A/Ci instantaneous carboxylation efficienc, iWUE intrinsic water-use efficiency, Fv/Fm maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII, PI performance index, AA antioxidant activity, MDA malondialdehyde, TPC total phenolic content, ACNs anthocyanins, PrC protein concentration, TSS total soluble solids, LRWC leaf relative water content, K potassium, Mn manganese.

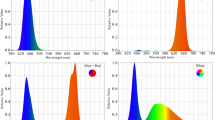

Polar heatmap with circular dendrogram

In this study, the similarities and differences between all treatments for both Lollo bionda and New Red Fire 11 cultivars were assessed separately based on Ward and Euclidean distance methods. A cluster analysis was conducted to group both treated and untreated plants based on their morphological and physiological characteristics. Additionally, a polar heat map was created to visually depict the relationships among the clusters (Fig. 10). For the Lollo bionda cultivar, three distinct clusters were identified (Fig. 10A). Group A comprised plants exposed to red and blue light spectra under non-stress conditions. This group exhibited high values for all vegetative growth parameters. Physiological traits in this group indicated high levels of intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE), anthocyanin content (ACNs), net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), and Fv/Fm, along with higher concentrations of total chlorophyll (Chl.T), carotenoids, potassium (K), and manganese (Mn). However, this group exhibited low levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (TR). Group B included plants that experienced salinity and alkalinity stress while exposed to red and blue light spectra. This group had moderate morphological parameters and high values of certain physiological traits, such as performance index (PI), instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (A/Ci), chroma (Croma), leaf pigments (a, b), antioxidant activity (AA), total phenolic content (TPC), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (TR). But this group showed lower levels of Fv/Fm, relative stomatal resistance (rs), leaf relative water content (LRWC), proline, total soluble solids (TSS), and manganese (Mn). Group C included untreated plants as well as plants under salinity and alkalinity stress, all grown under ambient light conditions. This group generally had low values of morphological parameters but showed high levels of stress-related traits such as proline, MDA, LRWC, TSS, Fv/Fm, rs and Protein concentration (PrC). Similarly, in the New Red Fire 11 cultivar, three distinct clusters were identified (Fig. 10B). Group A included plants treated with salinity and alkalinity stress under red and blue light spectrums, along with untreated control plants exposed to blue light spectrum. This group showed moderate values for both morphological and physiological parameters. Group B comprised untreated plants (control) cultivated under the red light spectrum, which demonstrated high morphological parameter values. Additionally, some physiological characters, including performance index (PI), total chlorophyll (Chl.T), carotenoids, leaf pigments (a), stomatal conductance (Gs), transpiration rate (TR), A/Ci, and net photosynthetic rate (Pn), reached their highest levels in this group. Group C included treated plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress, as well as control plants grown under ambient light conditions. This group showed low morphological parameter values, particularly under salinity and alkalinity stress. Moreover, physiological parameters, such as potassium (K), anthocyanins (ACNs), proline concentration (PrC), total phenolic content (TPC), intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE), PI, Chl.T, carotenoids, Gs, TR, A/Ci, Pn, intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), antioxidant activity (AA), pigments (a and b), and chroma (Croma), were at their lowest. In contrast, some stress-related traits, including proline, malondialdehyde (MDA), leaf relative water content (LRWC), total soluble solids (TSS), Fv/Fm, and relative stomatal resistance (rs), exhibited elevated values, especially under conditions of salinity and alkalinity stress.

Polar heatmap with circular dendrogram represents the grouping of control and treated lettuce plants based on their morphological and physiological parameters in (A) the Lollo Bionda cultivar and (B) the New Red Fire 11 cultivar. Here, SFM shoot fresh mass, RFM root fresh mass, SDM shoot dry mass, RDM root dry mass, Leaf No leaf number, Chl.T total chlorophyll, a and b leaf pigments, Croma chroma, Pn net photosynthetic rate, Ci intercellular CO2 concentration, TR transpiration rate, Gs stomatal conductance, rs stomatal resistance, A/Ci instantaneous carboxylation efficienc, iWUE intrinsic water-use efficiency, Fv/Fm maximal photochemical efficiency of PSII, PI performance index, AA antioxidant activity, MDA malondialdehyde, TPC total phenolic content, ACNs anthocyanins, PrC protein concentration, TSS total soluble solids, LRWC leaf relative water content, K potassium, Mn manganese.

K-means clustering

K-means clustering in plant physiology assists in organizing complex data, identifying groups with similar physiological traits, and revealing underlying patterns that may be relevant to plant adaptation, and productivity. It serves as a bridge between data analysis and biological interpretation, helping researchers to dissect complex datasets into interpretable groups, enhancing the understanding of how plants adapt to and manage stress. By grouping plants based on their response characteristics, the method assists in identifying resilient cultivars and effective treatments under plant stress conditions. Based on the k-means analysis, all treatments, which comprised three different light conditions (red, blue, and ambient light), three stress levels (control, salinity stress and alkalinity stress), and two lettuce cultivars (Lollo Bionda and New Red Fire 11), were classified into three distinct clusters (Fig. 11). Control and treated plants exposed to salinity and alkalinity stress in both cultivars under ambient light were classified into Cluster 1. In this cluster, control plants were further away from plants under stress conditions. Cluster 2 includes unstressed (control) plants that were grown under red and blue light conditions. However, the two lettuce cultivars were positioned far apart within this cluster, indicating that these cultivars are affected differently by red and blue light conditions. Treated plants exposed to salinity and alkalinity stress in both cultivars under red and blue light were classified into Cluster 3. The separation of these treatments into three distinct clusters indicates that red and blue supplementary lights have a better effect on increasing vegetative growth and yield of lettuce plants. This effect is observed under both stress and non-stress conditions, as these supplementary lights improve the measured parameters when compared to ambient light.

K-means clustering analysis of supplementary lights and stress treatments in two lettuce cultivars. The coding system in the figure is structured as follows: The first letter indicates the cultivar type (L: Lollo bionda, N: New Red Fire 11), the second letter represents the light treatment applied (A: Ambient, R: Red, B: Blue), the third letter specifies the type of stress condition (C: Control, S: Salinity, A: Alkalinity). For example, the code L–A–C translates to: Lollo bionda cultivar grown under ambient light with no stress (control condition).

Discussion

Vegetative characteristics of lettuce

The results of the current experiment highlight the crucial role of light spectra in mitigating the negative effects of salinity and alkalinity stress on lettuce plants’ vegetative growth. The NRF11 cultivar exhibited better overall growth performance, especially when exposed to red spectra under non-stress conditions. On the other hand, the LB cultivar displayed the most inhibited vegetative growth parameters under alkalinity stress conditions without supplemental light. Understanding the specific responses of different lettuce cultivars to stress conditions and light spectra can aid in selecting resilient cultivars for cultivation in challenging environments. Additionally, optimizing light spectra can be a potential strategy for enhancing lettuce production and improving plant performance under stress conditions. Light spectra can have positive effects in mitigating the adverse effects of salinity and alkalinity stress on plants. Red light has been found to promote plant growth and development. It enhances stem elongation and increases leaf surface, leading to improved photosynthetic capacity. This can help counter the negative effects of salinity and alkalinity stress by boosting overall plant growth and biomass production39. Blue light is known to have a positive impact on photosynthetic performance and chlorophyll formation. It promotes chloroplast development, allowing plants to efficiently capture and utilize light energy for photosynthesis40. This can be beneficial in salinity and alkalinity stress conditions where photosynthetic activity may be impaired. Light spectra, especially red and blue light, have been shown to influence nutrient uptake in plants. Red light has been found to enhance root growth and nutrient absorption, helping plants access essential nutrients even under stress conditions41. By improving nutrient uptake, plants can maintain their physiological functions and counter the negative effects of salinity and alkalinity stress. Light spectra can induce morphological adaptations in plants, helping them cope with stress conditions41. Salinity and alkalinity stress can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants, causing oxidative damage. Studies have shown that specific light spectrums, such as red and blue light, can stimulate antioxidant defense mechanisms in plants, helping to scavenge ROS and protect plant cells from damage42. This antioxidant activity can play a crucial role in minimizing the negative impact of salinity and alkalinity stress. Overall, by providing optimal light conditions, specific light spectrums can positively influence plant growth, photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and antioxidant defense mechanisms. These effects can help alleviate the adverse effects of salinity and alkalinity stress, enabling plants to adapt and maintain their productivity in challenging environmental conditions.

Photosynthetic pigments

The levels of chlorophyll can decline in response to anaerobic stress or leaf senescence due to reduced synthesis and increased degradation processes43. The content of chlorophyll in leaves is a critical indicator directly associated with photosynthesis in plants, reflecting their photosynthetic efficiency44. The application of salinity and alkalinity stress led to a decline in the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids in lettuce leaves when compared to the control treatment. However, when lettuce cultivars were subjected to blue and red light spectrums along with salinity and alkalinity stress conditions, there was a significant increase in these pigment traits. It is worth noting that the effect of blue light in enhancing pigment content under the conditions of salinity and alkalinity stress was more pronounced in both lettuce cultivars compared to the effect of red light. This suggests that blue light plays a crucial role in mitigating the negative impact of stress on pigment accumulation in lettuce leaves. These findings highlight the potential of manipulating light spectra as a strategy to enhance pigment content in lettuce cultivars grown under stress conditions. Alkalinity stress, characterized by high pH levels, has detrimental effects on chloroplasts and reduces the photosynthetic activity of plants. The presence of bicarbonate compounds leads to a decrease in leaf Fe concentration, resulting in a reduction of chlorophyll content45. Alkaline stress can cause severe damage to photosynthetic pigments and membrane systems, indicating its potential impact on the cytoplasm and disruption of chloroplast structure and function, leading to decreased chlorophyll synthesis46. The decrease in chlorophyll content has negative consequences on plant growth strength and stress resistance47. The decline in chlorophyll levels under alkaline stress could be attributed to several factors, including the deposition of magnesium ions (Mg+2), which can result in the destruction of green pigments, increased oxidative stress causing damage to chloroplast structure, and enhanced activity of the enzyme chlorophyllase responsible for chlorophyll degradation48. The amount of chlorophyll in living plants is a critical factor for maintaining their photosynthetic capacity, and the impact of stress on the levels of chlorophyll a and b can vary depending on the intensity and duration of the stress4.

Leaf color indicators

This experiment finding emphasize that salinity and alkalinity stress can alter the color properties of lettuce, but the application of specific light spectrums can counteract these effects to some extent. Such insights are valuable for growers and consumers who prioritize the color quality of lettuce. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and optimize light spectra management to achieve desired color characteristics in lettuce cultivars subjected to stress conditions. The effects of salinity and alkalinity stress on plant pigments, such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, and anthocyanins, can result in color changes in lettuce leaves. However, there is limited information available regarding the impact of salinity and alkalinity stress on hue and chroma indices of lettuce leaves. A study on amaranth plants revealed that increased salinity stress led to a reduction in hue and chroma indices49. Additionally, research on green peas demonstrated significant variations in hue and chroma indices as well as L*, a*, and b* values in response to different light spectrums, with blue and blue-red light having a more pronounced effect than red light50.

Photosynthetic parameters

The results showed that that red and blue supplemental light can mitigate the negative impacts of salinity stress on photosynthesis, while the response to alkalinity stress varies between the LB and NRF11 cultivars. These findings indicate that alkalinity stress has a more pronounced effect on the photosynthetic efficiency of lettuce plants compared to salinity stress, and the specific light conditions can modulate these effects. Salinity and alkalinity stress can have detrimental effects on photosynthesis, affecting both biochemical and photochemical processes51. The Fv/Fm variable, which represents the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II, serves as a sensitive indicator of plant photosynthetic performance52. Inhibition of light triggers a reduction in quantum efficiency, which can be assessed through the Fv/Fm. If a plant is unable to dissipate excess solar energy, it is transferred to oxygen via chlorophyll, resulting in photooxidative damage. Initial signs of this damage manifest in the D1 protein in photosystem II, leading to membrane destruction and chlorophyll oxidation. Although limited research exists on the impact of alkalinity stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence53, some studies have reported inhibition of photosynthesis and delayed plant growth under such conditions54. Our research revealed that salinity and alkalinity stress led to a decrease in the Fv/Fm variable and photosynthetic efficiency index, while the application of blue and red light spectra to plants subjected to these stresses enhanced this variable. Environmental stressors that affect photosystem II efficiency cause a decline in the Fv/Fm ratio4. Alkalinity has been shown to have a detrimental effect on the photosynthetic characteristics and chlorophyll fluorescence in certain species55. Under red light and salt conditions, reaction centers in plants became damaged, leading to a reduction in electron transfer capacity in photosystem II. However, when blue light was combined with red light, a positive effect was observed56. Applying blue light in conjunction with salinity significantly impacted the maximum photochemical quantum yield56. The Fv/Fm index measures the maximum quantum performance of photosystem II, usually ranging close to 0.83, and in controlled conditions, it serves as an indicator of plant photosynthesis rates. Alterations in this index correspond to changes in light trapping efficiency. Misra et al.57 observed a decrease in the photochemical efficiency of photosystem II in Phaseolus and Brassica genera 3 days after salinity application compared to control plants. In a study on two sorghum plant cultivars, a sodium chloride concentration of 250 mM decreased photochemical quantum efficiency by 9–10% and electron transfer rate by 20–25%58. Changes in the rate of photosynthesis under salinity stress primarily result from stomatal closure, overshadowing the effects on the photosynthesis apparatus. Barley plants exhibited changes in net photosynthesis rate within approximately 24 h of salt application, while no alterations were observed in photosystem II efficiency59. A decrease in photosystem II quantum efficiency indicates a reduction in electron transfer speed within the chloroplast electron transport chain, potentially increasing the likelihood of reactive radical production that can damage photosystem II components60. Plant vitality is evaluated using the photosynthetic efficiency index (PI), which combines three independent parameters: the density of fully active reaction centers, electron transfer efficiency to the electron transfer chain other than quinone A (QA), and the probability of trapping absorbed photons by reaction centers. This index reflects the performance of both photosystems I and II, providing quantitative information on plant performance under stress conditions30. Several studies have reported the inhibition of photosynthesis and delayed plant growth due to alkalinity stress54, while Deng et al.61 noted that the photosynthetic efficiency index gradually decreases with increasing salinity and alkalinity stress, with extreme stress resulting in a further decline compared to control levels.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the application of salinity and alkalinity stress resulted in a decrease in crucial photosynthetic parameters such as carbon dioxide exchange, stomatal conductance, transpiration, gas exchange, and net photosynthesis. However, when blue and red light spectra were employed on plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress, these parameters showed improvement. These results align with the research conducted by Bayarash et al.62, which also observed reduced rates of photosynthesis, gas exchange, transpiration, and chlorophyll fluorescence indices under salinity and alkalinity stress. The decline in photosynthetic indices can be attributed to stomatal closure triggered by stressful conditions, leading to a reduction in carbon dioxide exchange and subsequently lowering the activity of the Rubisco enzyme. Consequently, the rate of photosynthesis decreases, ultimately impacting dry matter production63. Bayarash et al.62 discovered that in alkalinity stress conditions, stomatal closure and decreased transpiration rate were caused by reduced leaf water content and decreased leaf K levels. The reduction in K content hampers water transfer to the stomata, resulting in stomatal closure, decreased transpiration, gas exchange, and carbon dioxide uptake. The closure of stomata and the resultant decrease in transpiration also elevate leaf temperature, leading to damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, particularly photosystem II, and a decline in chlorophyll fluorescence indices. Bayarash et al.62 also found that both spinach cultivars exhibited reduced chlorophyll fluorescence indices under stress conditions, likely due to decreased relative chlorophyll content. Furthermore, elevated leaf water content promotes free radical accumulation, disrupting cell membrane and organelle efficiency, and ultimately impairing electron transfer processes and decreasing chlorophyll fluorescence indices64. The reduction in chlorophyll fluorescence indices subsequently leads to a decrease in photosynthesis. Tang and Turner65 investigated two plant species under drought and alkaline conditions and observed a significant decrease in photosynthesis rate under alkalinity stress. This reduction in photosynthetic indices in alkaline conditions can be attributed to diminished absorption of crucial elements such as Fe and other micronutrients, ultimately decreasing chlorophyll content and compromising photosynthesis rate5, which aligns with the findings of the current research on the impact of alkalinity stress on nutrient absorption, chlorophyll content, and photosynthesis rate.

Antioxidant capacity

The study found that both salinity and alkalinity stress conditions resulted in a decrease in the antioxidant capacity of lettuce cultivars compared to the control treatment. However, the application of blue and red light spectrums under salinity and alkalinity stress conditions enhanced the antioxidant capacity in both lettuce cultivars. These results suggest that light spectra can play a beneficial role in enhancing the antioxidant defense system of lettuce plants under stressful conditions. Antioxidants are important for scavenging reactive oxygen species and protecting plants from oxidative damage4. The increase in antioxidant capacity observed when blue and red light spectrums were used indicates that these light wavelengths have the potential to enhance the antioxidant response in lettuce plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress. The researchers discovered that salt stress has a detrimental effect on the antioxidant activity of Schizonepeta tenuifolia Briq66. Additionally, it was observed that the phenol content of lettuce plants exhibited a strong correlation with their antioxidant capacity, and this capacity decreased due to a reduction in phenol content under salt and alkali stress67. However, there is evidence that the combination of blue and red light spectrum can enhance the production of antioxidant compounds in plants68. In line with this, a study found that the antioxidant capacity of lettuce leaves increased when exposed to a combination of blue and red light69. It has also been determined that increasing the content of photosynthetic pigments serves as a foundation for improving the antioxidant capacity of lettuce plants, while the combination of blue and red light plays a crucial role in stimulating the accumulation of antioxidant compounds in vegetables70. Therefore, red and blue LED lights positively influence antioxidant mechanisms in plants through various pathways. They are essential for photosynthesis, leading to the production of compounds vital for antioxidant defense. These lights enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes involved in scavenging harmful ROS71. They also regulate gene expression related to antioxidant defense and promote the production of antioxidant compounds like phenolic compounds34. Overall, red and blue LED lights help plants defend against oxidative stress, maintain health, and vitality.

Malondialdehyde

The application of salinity and alkalinity stress to both LB and NRF11 lettuce cultivars led to an increase in malondialdehyde content compared to the control treatment. However, the use of blue and red light spectra showed a mitigating effect on malondialdehyde levels in both lettuce cultivars. These findings suggest that light spectra can help alleviate oxidative stress caused by salinity and alkalinity stress in lettuce plants. Malondialdehyde is a marker of lipid peroxidation, which is an indicator of oxidative damage. The decrease in malondialdehyde levels observed when blue and red light spectra were applied suggests that these light wavelengths can protect lettuce plants from oxidative stress. One significant consequence of oxygen free radicals on cellular health is the destructive impact on cell membranes. Analyzing the concentration of malondialdehyde in plant tissue serves as an indicator of the extent of cell membrane destruction, as this compound is released during membrane peroxidation and degradation. Increased levels of malondialdehyde are a clear indication of oxidative stress72. In particular, red light radiation and salinity stress have proven to be especially damaging to sensitive plant tissues. Numerous studies, including Akbari et al.73 on savory (Satureja hortensis L.), and Delavari et al.74 on basil, have observed an elevation in malondialdehyde levels due to increased salinity. This confirms the role of salinity stress in intensifying oxidative stress and further highlights the damaging effects on cellular membranes.

Leaf phenolic content

These results suggest that the LB cultivar has a higher capacity to produce phenolic compounds in response to alkalinity stress and supplemental lights. Phenolic compounds are bioactive compounds with antioxidant and health-promoting properties. Phenolic compounds, including various types such as simple phenols, acid phenols, chalcones, flavonoids, and anthocyanins, are abundant in plants75. The impact of salinity stress on phenolic content in plants has been studied in different species. In fenugreek, it was observed that salinity stress led to increased phenolic compound content in the leaves, with a more pronounced increase in tolerant cultivars76. However, in sage plants, researchers found that the phenolic content initially increased with salinity stress but decreased at higher concentrations, attributing this decrease to the negative effect of salt stress on antioxidant properties, resulting in reduced phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity77. Phenolic compounds exhibit antioxidant activity primarily due to their oxidation–reduction properties, enabling them to scavenge and neutralize free radicals78. These compounds play crucial roles in defense and antioxidant functions, and their synthesis can be induced in response to environmental stress79. The tolerance of plants to alkalinity depends on various factors, including plant species, growth conditions, and the buffering capacity of the culture medium80. The increase in phenolic compounds under alkalinity stress may be attributed to their antioxidant role against reactive oxygen species81. Light spectrum also influences phenolic compound content, as the use of blue and red light spectrums has been shown to increase phenolic content in lettuce leaves, and the combination of blue and red lights enhances both phenolic and antioxidant compounds in lettuce plants69.

Anthocyanin content

The study found that both salinity and alkalinity stress conditions resulted in a decrease in leaf anthocyanin concentration in lettuce cultivars compared to the control treatment. However, the application of blue and red light spectrums had a positive impact on anthocyanin concentration in both lettuce cultivars. These findings suggest that light spectra play a role in enhancing anthocyanin synthesis in lettuce plants under stressed conditions. Anthocyanins are pigments responsible for the red, purple, and blue colors in plants and have important antioxidant and health-promoting properties82. The increase in anthocyanin concentration observed when blue and red light spectrums were utilized indicates that these light wavelengths can stimulate anthocyanin production in lettuce plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress. It is worth noting that the NRF11 cultivar had the highest anthocyanin concentration under normal, unstressed conditions when exposed to blue light. This suggests that the combination of specific lettuce cultivars and light spectra can potentially enhance anthocyanin accumulation in lettuce leaves. Anthocyanins, the most common group of flavonoids, play a vital role as antioxidant compounds in plants by not only neutralizing free radicals but also preventing their formation, thus reducing oxidative damage83. While these pigments are not essential for plant growth and survival like photosynthetic pigments, their sensitivity to salinity and alkalinity conditions can serve as an indicator of stress83. Moreover, anthocyanins serve as osmotic compensatory solutions under water stress, salinity, and alkalinity, and their high content has been observed in plants that exhibit tolerance to these conditions84. When faced with oxidative stress, anthocyanins play a crucial role in mitigating damage by quenching active oxygen species, particularly in young leaves.

Leaf protein content

The present study demonstrated that the protein content in plants subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress significantly decreased compared to control plants. However, the application of blue and red light spectrums on plants exposed to salinity and alkalinity stress resulted in an improvement in leaf soluble protein content compared to the stressful conditions. This finding aligns with earlier research by Shirahmadi et al.56, which observed a notable reduction in leaf soluble proteins with increasing salinity stress. The protein decline observed can be attributed to the inhibition of protein synthesis by non-living stresses like salt stress, which has an impact on the synthesis of specific proteins, including protein enzymes. Additionally, under stressful conditions, plants hydrolyze proteins through the action of protease enzymes to produce amino acids required for regulating cell osmosis, resulting in a decrease in soluble protein content, as observed in this research85.

Proline content of leaves

The study found that under ambient light conditions, the proline content in lettuce cultivars increased significantly when they were exposed to salinity and alkalinity stress, compared to the control treatment. Interestingly, the application of blue and red light spectra during salinity and alkalinity stress led to a decrease in proline accumulation in both lettuce cultivars. This indicates that these specific light wavelengths may have a regulatory effect on proline metabolism under stress conditions. It is possible that the light spectra influenced other stress-responsive signaling pathways or altered the synthesis and degradation of proline. Research shows that the accumulation of proline and soluble carbohydrates is a general response of plants under salinity and alkalinity stress54. Proline is an adaptive osmolyte that is mostly produced in response to osmotic imbalance in the cytoplasm86. Also, proline is quickly broken down after stress, which may provide factors that support the oxidative photophosphorylation cycle in mitochondria and provide the necessary energy (ATP) to return from the stress state87. The higher accumulation of proline indicates the ability to regulate osmotic resistance and resistance to adverse environmental conditions in plants46. The researchers found that red/blue light in salinity conditions kept the plant in a better condition by controlling the amount of proline56. In a comparative study between LED and fluorescent light, it was shown that the amount of proline under fluorescent light and water stress had the highest concentration and its concentration decreased rapidly during the recovery stage88.

Soluble sugars

These findings suggest that the response of lettuce cultivars to light spectrums in terms of total soluble sugars can vary. The NRF11 cultivar showed a positive response to red light, indicating that this light spectrum can enhance sugar accumulation in lettuce leaves under alkalinity stress. However, the LB cultivar did not exhibit any significant changes in total soluble sugars with the application of supplemental light. Under low light intensity, red light has been found to exhibit the highest carbon dioxide assimilation rate in various plants, as it possesses superior quantum performance for carbon dioxide fixation compared to other wavelengths of sunlight. Red light also promotes the expression of genes associated with photosynthesis89. In tomato seedlings, a combination of red and blue light resulted in a threefold increase in carbohydrate levels compared to red monochromatic light, while the starch content was numerically higher in equal proportions of red and blue light. However, no significant difference was observed between red monochromatic light and the combination of red and blue light40. Carbohydrates, as primary metabolites, act as compatible osmolytes and play a crucial role in mitigating environmental stresses such as cold, drought, salinity, osmotic stress, and low temperature. They also scavenge oxygen free radicals90. The accumulation of carbohydrates under stress conditions reduces plant damage. Soluble carbohydrates can activate key enzymes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, thus promoting anthocyanin production91. In conclusion, the light source can significantly impact carbohydrate accumulation in lettuce plants. This characteristic becomes more valuable under salinity conditions, and manipulating the appropriate light spectrum can potentially alter the plant’s response in such conditions.

Relative leaf water content

The present research revealed that the use of blue and red light spectrums in greenhouse conditions improved the relative water content of lettuce cultivars subjected to salinity and alkalinity stress. However, salinity and alkalinity stress alone resulted in a decrease in the relative water content of leaves. Studies by Yang et al.92 have highlighted the negative effects of sodium bicarbonate on plant water content and absorption. Similarly, Bayarash et al.62 found that salinity and alkalinity stress reduced the relative water content of spinach leaves. Interestingly, Yang et al.92 noted that alkalinity stress had a more detrimental impact on water content compared to salinity stress, likely due to the poor structure of alkaline soils. The relative water content of leaves is crucial for a plant’s osmosis regulation, absorption ability, and drought tolerance, as evidenced by Sánchez-Rodríguez et al.93.

Nutrient elements