Abstract

This study focuses on a surface texturing technique using electrodeposition to enhance the junction properties of thin film solar cell structures. The CdS/CdTe solar cell structure was used to demonstrate this concept, focusing on the thermally evaporated oxygenated CdS layer deposition on the textured layer of electrodeposited CdS seeds, ultimately improving the CdS/CdTe junction properties and solar cell performance. Deposited CdS seeds have grown after the deposition of the thermally evaporated CdS: O layer and subsequent annealing. Optical characterizations of CdS seed layers and subsequent CdS layer stacks revealed that seed layers deposited with an applied potential of -680 mV exhibit a significant blue shift and a steep band edge. These optical characteristics were confirmed by the calculated bandgap values. Morphological characterizations exhibited an increment of seed density with applied potential. Additionally, an improved seed size and seed growth upon layer deposition by thermal evaporation were observed for the seeds deposited at -680 mV. Structural characterizations of seed layers via X-ray diffraction followed by Rietveld and Pawley refinements confirmed the optical bandgap variation. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy validated the results obtained for the optical bandgap with the analysis of surface chemistry of seed layers. These optimized CdS seed layers facilitated subsequent thermal evaporation of CdS: O thin films and the fabrication of CdS/CdTe solar cells. The electrical characterizations emphasized that the solar cells deposited using the seed layer at -680 mV yield better electrical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cadmium sulfide (CdS) is a commonly employed material for the window layer in thin film solar cells, particularly those based on cadmium telluride (CdTe). Solar cells based on the CdS/CdTe have demonstrated notable advancements in both efficiency and cost-effectiveness within the photovoltaic sector1,2. Nevertheless, a significant obstacle encountered in the development of CdS/CdTe solar cells pertains to the structural mismatch between the fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass substrate and the CdS layer, as well as the structural mismatch between the thermally evaporated CdS layer and the CdTe layer. These differences often lead to negative impacts such as poor adhesion, higher series resistance, and decreased open circuit voltage3,4,5,6,7. Hence, it is essential to enhance the interface quality between FTO and CdS to optimize the performance of CdS/CdTe solar cells.

One approach to enhance the quality of the interface involves incorporating a seed layer (either discrete or continuous) positioned between the FTO and the Thermally evaporated oxygenated CdS (TE-CdS: O) layer. A seed layer is a thin film that functions as a template for the growth of an additional layer above it. The implementation of a seed layer has been found to have several beneficial effects on subsequent layers8. These effects include the reduction of lattice mismatch, the increase in nucleation density, and the improvement of crystal orientation9,10,11. Multiple studies have documented the utilization of various materials as seed layers in CdS/CdTe solar cells, including zinc oxide (ZnO), zinc sulfide (ZnS), and tin oxide (TiO2)12,13,14,15,16. Most of these publications have used continuous seed layers for their studies, and the use of discrete seed layers is rare in the literature. The formation of a discrete seed layer is a rapid process, and precise control of time and other parameters is essential.

A discrete seed layer can also be used as a chemical-based surface texturing technique to increase the effective area of the junction interface. The most common method for surface texturing in the solar cell research field is laser scribing, which is a subtractive technique17,18,19. However, the involvement of additive techniques, such as electrochemically deposited seed layers for surface texturing, is rare in the literature.

This study aims to utilize a discrete Electrodeposited CdS (ED-CdS) seed layer for the subsequent deposition of TE-CdS: O. Electrodeposition is a cost-effective and scalable method that enables the deposition of a seed layer or a thin film on diverse substrates20,21. The utilization of ED-CdS as a window layer in CdS/CdTe solar cells has been extensive, and it has demonstrated comparable or better performance when compared to other deposition methods, including chemical bath deposition (CBD), close-spaced sublimation (CSS), and vacuum thermal evaporation (VTE)22,23,24,25. However, the utilization of ED-CdS as a seed layer for TE-CdS: O and, specifically, a discrete seed layer has not been documented in the literature.

This work mainly focuses on examining the influence of applied potential on the morphological, structural, and optical aspects of ED-CdS seed layer deposition to determine optimal conditions. Systematic and extensive research has been conducted on ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layer stacks to determine the optimum morphological and optical properties. Additionally, the electrical properties of the CdS/CdTe solar cell devices have been examined. The somewhat lower efficiency observed in the CdS/CdTe solar cells in this study is likely attributed to the unoptimized CdTe layer, limiting overall device performance. However, the study demonstrated that efficiency can be further improved by applying this methodology. Additionally, this technique can be incorporated with other window and buffer layers, such as CdSe or ZnO, to approach novel device structures.

Research methodology

Applied potential optimisation of ED-seed layer

Before the electrodeposition of CdS, FTO substrates were cleaned using a procedure described elsewhere26. Electrodeposition of discrete CdS seed layers was performed using a three-electrode system with an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference, a Pt plate as the counter electrode, and a FTO glass plate as the working electrode. A circulating water bath containing CdCl2 (0.2 M) and Na2S2O3 (0.02 M) with a pH of 2.0 was heated to 80 °C and used as the electrolyte. The solution was stirred at a rate of 60 rpm. Prior to electrodeposition, cyclic voltammetry was performed with the same three-electrode system without stirring and suitable potential ranges were determined. The cathodically applied potential was varied from 620 to 700 mV in steps of 20 mV for a duration of 60 s. Successfully deposited thin films were washed with DI water and dried with nitrogen gas before annealing at 475 °C for 30 min and about 10 Torr with a 6% O2 in argon ambient. Seed layers were deposited on substrates individually, while the subsequent CdS layers were deposited at once on all such seed-deposited FTO substrates.

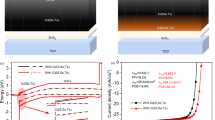

Before CdS/CdTe solar cells were fabricated, the TE-CdS: O layers were deposited on the ED-CdS seed layers. CdS powder (Sigma-Aldrich, Evaporation grade, 99.995%) was used for thermal evaporation of CdS thin films. Six samples were attached to the substrate holder, and the substrate rotation was set at 2.5 rpm to maintain a uniform deposition. While maintaining the chamber pressure at 2 × 10−4 Torr, 20% Oxygen within Argon ambient was introduced to the chamber using EQ-GSL-LCD 4-channel gas mixer from the MTI Corporation. PID temperature controllers were used to maintain the source and substrate temperatures at 500 and 150 °C, respectively. To control the evaporation flow, a mechanical shutter was used. The deposition was carried out for 4 min to get ~ 200 nm in thick CdS layers. Afterwards, the films were annealed at 475 °C for 30 min and about 10 Torr with a 6% O2 in argon ambient to make the surface uniform. The deposited ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layer stacks were investigated to understand the optical and morphological properties. A schematic diagram of the device fabrication is shown in Fig. 1.

CdTe layers (~ 5 μm) were deposited on top of the TE-CdS: O layers using the OTF-1200X close-spaced sublimation system (CSS) from the MTI Corporation to fabricate the CdS/CdTe solar cell. The Ar gas as the carrier with 6% oxygen was used as the ambient, and the pressure of the chamber was kept at about 10 Torr. The temperature profiles for substrate and source were set with pre-optimized gradients to reach the temperature values of 610 and 680 °C, respectively. The CSS process was carried out for 140 s. After retrieving the samples from CSS, the CdCl2 heat treatment was performed. For that, a 30 nm thick CdCl2 layer was deposited using the thermal evaporation technique on the CdTe layer. Then, the layer stack was air-annealed for 15 min at 400 °C in a tube furnace. The remaining CdCl2 was washed out with DI water and dried with nitrogen gas. Afterwards, using pre-optimized conditions, nitric–phosphoric acid solution (NP) etching was performed on the CdTe layer surface for 35 s27,28. The electrical contacts were deposited using the thermal evaporation technique on the post-treated CdTe layer in the order of 4 nm Cu layer before the 40 nm Au layer. Finally, the fabricated cells were air-annealed for 20 min at 200 °C in a tube furnace. Successfully fabricated solar cells were later characterized for electrical properties.

Characterization

Various characterization techniques (SEM, XRD, XPS, UV-Vis, J-V characteristics) were employed to understand the samples’ behavior and their characteristics.

SEM images were taken by means of Quanta 250 FEG Scanning Electron Microscopes (SEM) with 5 kV accelerating voltage to study the surface morphology of both seed and stack layers.

Bruker D8 Advance with Cu Kα (λ = 1.5406 Å) was used to obtain grazing incident X-ray diffractograms (GIXRD) for structural characterizations of the deposited seed layers. The measurements were performed with 1° incident angle and 2θ range from 10° to 80° in steps of 0.01°.

ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS) was used to study the surface chemistry of the deposited seed layers with 180° double-focusing, bi-polar hemispherical electron energy analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). Monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.6 eV) were used with an analysis spot size of 300 microns and energy step size of 1.000 eV.

Shimadzu UV-1800 double-beam spectrophotometer was used to obtain transmittance spectra from 300 to 1100 nm in the step of 1 nm for studying the optical characteristics of deposited CdS seed layers and layer stacks.

The current-voltage characteristic of the CdS/CdTe solar devices was examined by the Peccell PEC-L01 solar simulator system with AM 1.5G illumination.

Results and discussion

Cyclic voltammetry analysis

Figure 2 shows the cyclic voltammogram obtained with the three-electrode system. Two consecutive scans were performed in the potential range of 0 to −0.75 V with a scan rate of −0.1 Vs−1 with a step size of −0.002 V to check whether the knee bend region is significantly shifting with the deposition duration and to identify the optimal deposition potential range.

The following reaction takes place when a cathodic potential is applied to the three-electrode system, and a cathodic current is passed through the system29.

Based on the results obtained, the range within two verticle lines (−0.70 to −0.62 V) was used for the study by considering the knee bend of the CV.

Optical characterizations

Figure 3 shows the transmittance spectra of ED-CdS layers and ED-CdS/TE-CdS stacks with varying applied potential. The behavior of the transmittance spectra can be attributed to both the discrete nature of the seed layers and the crystallinity of the films. Since the deposited seeds were discretely arranged, photons of the lower wavelengths were also seen to be partially transmitted through the sample. According to Fig. 3 (a), the transmittance around the absorption edge (~ 500 nm) increased with increasing applied potential up to −680 mV and then started decreasing in further increments.

In Fig. 3(a), for the electrodeposited CdS seed layers, the discretely arranged seeds allow partial transmission of photons at shorter wavelengths since the substrate is not fully covered, resulting in higher transmittance in that region compared to continuous films.

Figure 3 (b) shows the variation of transmittance spectra of ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layers stacks with applied potential. All the samples could achieve more than 80% of transmittance beyond the absorption edge wavelength (~ 550 nm). According to the inset of the figure, the blue shift of the absorption edge increased with the increasing applied potential. However, the highest steepness was recorded for the CdS layer electrodeposited using − 680 mV. The seed layer deposited at − 680 mV provides the steepest absorption edge due to its better crystallinity and lower defect density, thereby confirming the optimized optical behavior at this potential.

Calculated optical bandgap values of the ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O stacks are plotted as shown in Fig. 4. As the applied potential increased, the Eg showed a rising trend up to −680 mV, after which it started to decrease. Although for bulk materials, Eg is constant, it can vary for thin films due to thickness, doping, and other factors. This defect-induced band-tailing phenomenon can be explained by the development of localized energy states. The Eg decreases as the band tail width in semiconductors increases21.

The EU and band tailing width increase as a result of an increase in these disorders and defects, which causes a drop in the Eg25,26. According to Fig. 4, the EU variation exhibits an opposite trend to the Eg variation, justifying the fact that disorder formation governed the Eg variation.

Based on the aforementioned optical characterization results, it appears that the CdS films deposited with applied potential − 680 mV have better optical characteristics than the others.

Morphological characterisation

SEM images were obtained from the seed layers deposited at −620, −680, and − 700 mV and are shown in Fig. 5 (a, b,c). All the images exhibit discretely arranged seeds over the FTO layer. Compared to the seeds deposited at −620 mV, larger seeds can be observed for the seed layer deposited at −680 mV. Figure 5 (c) exhibits a wide range of seed sizes and higher seed density.

SEM images obtained from the seed layers deposited with an applied potential of (a) −620 mV, (b) −680 mV, (c) −700 mV, and (d) corresponding mean seed sizes. SEM images of corresponding ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O stacks where seed layers deposited with an applied potential of (e) −620 mV, (f) −680 mV, (g) −700 mV, and (h) corresponding mean sizes of grown seeds.

Figure 5 (e, f,g) shows the SEM images obtained from the ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layer stacks where the seed layer deposited at −620, −680 and − 700 V. Qualitatively, two main observations can be seen from all three SEM images of Fig. 5 (e, f,g); (1) the coalescence of TE-CdS: O clusters has formed slightly large grains and (2) even larger seeds have been grown by the coalescence of TE-CdS: O clusters into the ED-CdS seeds. A considerable contribution to this TE-CdS: O grain formation and growth of the ED-CdS seeds was provided by the post-annealing of ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layer stacks. Figure 5 (d) and (h) show the mean seed sizes and the mean size of grown seed variations with applied potential, respectively.

For quantitative investigation, the size of the seeds, the density of the seeds distribution, and the size of the grown seeds were measured and shown in Table 1.

The mean size of the seed has increased with the increment of applied potential up to −680 mV and decreased thereafter. However, the seed density has increased continuously with the increment of applied potential. The size variation of the grown seeds in ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O layer stacks also exhibits the same trend as the mean seed size variation. Also, the highest seed growth percentage is recorded for the seed layer deposited with − 680 mV.

Structural characterization

Figure 6 shows the GIXRD diffractograms obtained from the seed layer deposited at −620, −680 and − 700 mV. It exhibits that all the deposited seed layers are polycrystalline CdS (PDF 00-041-1049) with (002) plane preferential.

The Rietveld and Pawley refinements were performed with the X’pert Highscore software. Rietveld refinement was used to determine crystallite size, microstrain and phase distribution, while Pawley refinement was used to calculate lattice constants, and all the calculated values are given in Table 2.

The prominent three peaks of the reference pattern of CdS were used to investigate crystallite size and microstrain. Crystallites aligned to different planes show different sizes and microstrains but are almost similar. According to the results, the crystallite size increased at −680 mV in all three considered planes and then decreased after further increasing the applied voltage. However, the microstrain properties for all the samples show the opposite trend. The crystallite size variation is quite similar to the mean seed size variation in Table 1, suggesting the morphological growth of the seeds at the electrodeposition stage is governed by their crystallographic growth. The highest hexagonal phase concentration was obtained from the seed layer deposited with − 680 mV, and the variation is similar to the crystallite size variation trend. Stacking faults are the main reason for the formation of cubic CdS (PDF 01-075-1546), which occur due to the removal of one atomic plane (C) from the hexagonal atomic structure (ABCABC) leading to cubic structure (ABAB)30,31,32.

With the increase of applied potential, lattice parameter a (= b) has slightly decreased up to −680 mV and saturated beyond. However, lattice parameter c has continuously increased with the increase of applied potential. The lowest unit cell volume was observed from the applied potential of −680 mV. With the reduction of unit cell volume, the electron cloud bonds tightly to the parent atoms and more energy is required to excite an electron33. This phenomenon confirms the highest bandgap observed from the seed layer deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV.

Surface composition and chemical state analysis

Figure 7 (a) shows the XPS spectra obtained in the survey mode from the ED-CdS seed layer deposited with different applied potentials. All the spectra exhibit the occurrence of Cd3d, S2p, Sn3d5, and O1s peaks. All the spectra were charge-referenced to an adventitious C1s peak at 284.8 eV.

High-resolution XPS spectra were obtained for the Cd3d and S2p peaks and shown in Fig. 7 (b) and (c). Cd3d region has well-separated spin-orbit components separated by ~ 6.80 eV, while S2p has closely spaced spin-orbit components separated by ~ 1.16 eV. Thermo Scientific Avantage Data System software was used to deconvolute all peaks.

According to Fig. 7 (b), the highest positive shift of the binding energy compared to the standard peak position (405.10 eV) can be observed from the ED-CdS seed layer deposited with the potential of −680 mV. This observation again confirmed the highest bandgap value obtained from the ED-CdS seed layer deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV. According to Fig. 7 (c), seed layers deposited with − 660 and − 680 mV exhibit a lower area than the rest, which is a clue for a lower atomic percentage of S. Further, −680 mV has the highest positive shift of binding energy. Table 3 summarises all the results obtained from the XPS analysis.

According to Table 3, only a slight variation of binding energies can be observed with the applied potential variation. The highest positive shifts of binding energies in Cd and S chemical states were recorded for the seed layers deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV. This confirms the highest bandgap obtained at seed layers deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV. Atomic Cd percentage has increased with the increment of applied potential up to −680 mV and decreased beyond, leading the highest S deficiency to occur in the seed layer deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV.

Electrical characterisation of CdS/CdTe solar cells

Figure 8 shows the electrical properties variation of the ED-CdS/TE-CdS: O/CSS-CdTe solar cells with the applied potential of seed layer deposition. ED-CdS seed layers deposited at −660 and − 680 mV show higher short circuit current density (JSC) than the rest. Open circuit voltage (VOC), fill factor (FF), and efficiency have increased to −680 mV and decreased after that.

The variation of efficiency is almost similar to the variation of bandgap shown in Fig. 4, suggesting that the variation in optical properties mainly governed the electrical properties. The highest average efficiency of 10.1% from 16 circular dot-shaped solar cells was obtained from the applied potential of −680 mV, with the highest individual solar cell efficiency reaching up to 11.2%. The authors have studied the same CdS/CdTe solar cells with the above-mentioned conditions but without the ED-CdS layer34, which have significantly lower efficiency, suggesting the improvisation of solar cell performance after introducing the ED-CdS seed layer26. Usually, the surface of a bare TE-CdS: O layer has a uniform and flat nature. With the growth of the seeds, the surface of CdS layer stacks appears to have blisters-like structures (expected surface texture), leading to an increment in the effective area of the TE-CdS: O/CSS-CdTe interface. We propose that this enhancement in the effective surface area causes an improvement in generating more electron-hole pairs. Hence, the highest growth of seeds at −680 mV may have an influence on the achievement of the highest electrical properties. According to all characteristic observations, we observed that the optimum applied potential for an ED-CdS seed layer should be −680 mV to achieve maximum efficiency.

Conclusion

In this study, discrete CdS seed layers were deposited using the electrodeposition technique and could be identified as a method for surface texturing. The applied potential of ED-CdS seed layers was optimized to control the seed distribution, enhance the thermal evaporation process of CdS and improve the fabrication of CdS/CdTe solar cells. Through a comprehensive series of characterizations and analyses, several key findings emerged.

Optical characterizations of the electrodeposited CdS seed layers and their subsequent layer stacks revealed that seed layers deposited with an applied potential of −680 mV exhibit optimum optical properties. These optimum seed layers displayed a significant blue shift, a steeper band edge, excellent transmittance in the 550–1100 nm wavelength range, and a higher bandgap. Morphological characterizations demonstrated large seed size and seed growth at −680 mV, resulting in a higher junction area (CdS/CdTe). Structural analyses using X-ray diffraction followed by Rietveld and Pawley refinements further confirmed the structural dominance of the optically and morphologically optimized seed layers. The effective area of the TE-CdS: O/CSS-CdTe interface increased due to the growth of the seeds, leading to higher electrical properties. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy provided valuable insights into the surface chemistry of the seed layers, validating the optimal conditions at −680 mV.

These optimized CdS seed layers were pivotal in facilitating the thermal evaporation of CdS thin films and the subsequent fabrication of CdS/CdTe solar cells. Electrical characterizations of these solar cells emphasized the significant impact of the optimized seed layers, resulting in higher electrical properties, including a maximum average efficiency of 10.1% and a maximum individual solar cell efficiency of 11.2%. The study’s conclusion emphasizes the critical significance of exact control over the electrodeposition parameters for CdS seed layers for performance enhancement of CdS/CdTe solar cells.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chu, T. L. & Chu, S. S. Recent progress in thin-film cadmium telluride solar cells. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 1 (1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.4670010105 (1993).

Khrypunov, G. et al. Recent developments in evaporated CdTe solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 90 (6), 664–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2005.04.003 (2006).

Yoshida, T. et al. Atom-by-atom growth of cadmium sulfide thin films by electroreduction of aqueous Cd2+–SCN – complex. J. Electroanal. Chem. 473 (1–2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-0728(99)00071-6 (1999).

Bittau, F. et al. The effect of temperature on resistive ZnO layers and the performance of thin film CdTe solar cells. Thin Solid Films. 633, 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2016.10.068 (2017).

Kephart, J. M. et al. Band alignment of front contact layers for high-efficiency CdTe solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 157, 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2016.05.050 (2016).

Wei, S. H., Zhang, S. B. & Zunger, A. First-principles calculation of band offsets, optical bowings, and defects in CdS, CdSe, CdTe, and their alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 87 (3), 1304–1311. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.372014 (2000).

Giugni, A. et al. Optical phonon modes in ordered core-shell CdSe/CdS Nanorod arrays. Phys. Rev. B. 85 (11), 115413. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.85.115413 (2012).

Kumarage, W. G. C. et al. A study on the enhancement of opto-electronic properties of cds thin films: seed-assisted fabrication. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 32 (4), 045014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/aa5ee3 (2017).

Noor, N. et al. Influencing FTO thin film growth with thin seeding layers: a route to microstructural modification. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3 (36), 9359–9368. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5tc02144h (2015).

Liang, S. et al. State of the Art of ultra-thin gold layers: formation fundamentals and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 4 (12), 2533–2560. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2na00127f (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Seed layer-assisted growth of branched Bi2S3 nanostructure on α-Fe2O3 thin film for improved photoelectrochemical performance. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 32 (10), 13040–13050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-05700-4 (2021).

Terasako, T. et al. Structural and electrical properties of CuO films and n-ZnO/p-CuO heterojunctions prepared by chemical bath deposition based technique. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 132, 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2014.08.023 (2015).

Chen, Y. L. et al. New insights into the Electron-Collection efficiency improvement of CdS-Sensitized TiO(2) Nanorod photoelectrodes by interfacial Seed-Layer mediation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11 (8), 8126–8137. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b22418 (2019).

Ren, T. et al. Fabrication of CdS–ZnS layered thin films by hydrothermal seeded growth method. Thin Solid Films. 513 (1–2), 99–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2006.01.029 (2006).

Aslam, M. M. et al. Growth and characterization of layer by layer CdS–ZnS QDs on dandelion like TiO2 microspheres for QDSSC application. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 36, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2015.03.030 (2015).

Wu, L. P. et al. Effect of ZnS buffer layers in ZnO/ZnS/CdS Nanorod array photoelectrode on the photoelectrochemical performance. RSC Adv. 4 (40), 20716–20721. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra00005f (2014).

Ding, J. et al. A laser texturing study on multi-crystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 214, 110587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2020.110587 (2020).

Ring, S. et al. Light trapping for a-Si:H/µc-Si:H tandem solar cells using direct pulsed laser interference texturing. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) - Rapid Res. Lett. 9 (1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.201409404 (2015).

Canteli, D. et al. Photon-collection improvement from laser-textured AZO front-contact in thin-film solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 463, 775–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.267 (2019).

Ling, J. et al. Electrodeposition of CdTe thin films for solar energy water splitting. Mater. (Basel). 13 (7), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071536 (2020).

Lincot, D. Electrodeposition of semiconductors. Thin Solid Films. 487 (1–2), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2005.01.032 (2005).

Sinha, T., Verma, L. & Khare, A. Variations in photovoltaic parameters of CdTe/CdS thin film solar cells by changing the substrate for the deposition of cds window layer. Appl. Phys. A. 126 (11), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-020-04058-4 (2020).

Lakmal, A. A. I. et al. Effect of cds layer thickness on thermally Evaporated-CdS/CdTe solar cell efficiency. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 33 (19), 15627–15637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-022-08467-4 (2022).

Dey, M. et al. Deposition of CdS thin film by thermal evaporation. in. International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE). 2019. IEEE. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ECACE.2019.8679325

Schaffner, J. et al. 12% efficient CdTe/CdS thin film solar cells deposited by low-temperature close space sublimation. 110(6). (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3639291

Lakmal, A. A. I. et al. Medium-vacuum thermal evaporation of cds:o thin films towards industrial CdS/CdTe solar cells: temperature and O2% optimization. Optik 294, 171476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2023.171476 (2023).

Chun, S. et al. Wet chemical etched CdTe thin film solar cells. Curr. Appl. Phys. 13 (1), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2012.07.015 (2013).

Bätzner, D. L. et al. A study of the back contacts on CdTe/CdS solar cells. Thin Solid Films. 361–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-6090(99)00842-1 (2000).

Altiokka, B. & Yildirim, A. K. Electrodeposition of cds thin films at various pH values. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 72 (6), 687–691. https://doi.org/10.3938/jkps.72.687 (2018).

Lee, J. H. & Lee, D. J. Effects of CdCl2 treatment on the properties of cds films prepared by r.f. Magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films. 515 (15), 6055–6059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2006.12.069 (2007).

Wan, L. et al. Effect of CdCl2 annealing treatment on thin CdS films prepared by chemical bath deposition. Thin Solid Films. 518 (23), 6858–6865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2010.07.011 (2010).

Lakmal, A. A. I. et al. Thermally evaporated cds thin films for cds/CdTe solar cells: effect of substrate temperature on cds layer. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B. 273, 115406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2021.115406 (2021).

Krueger, B. W. et al. Variation of band gap and lattice parameters of β–(AlxGa1 – x)2O3 powder produced by solution combustion synthesis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 99 (7), 2467–2473. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.14222 (2016).

Song, W. et al. Effect of CdCl2Treatment of CdS Films on CdTe/CdS Solar Cells. MRS Proceedings, 426. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1557/proc-426-331

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our co-author, DR. BUDDHIKA S. DASSANAYAKE, who tragically passed away on December 25, 2023. Despite his untimely demise, Dr. Dassanayake’s dedication and expertise left an indelible mark on the development of this work. As the Principal Investigator of the Advanced Materials Research Laboratory (AMReL), University of Peradeniya, his visionary leadership played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of this project. The collaborative spirit and collective effort that has shaped this manuscript are forever indebted to Dr. Dassanayake’s significant role. His impact on this project, his academic legacy, and his enduring influence within the scientific community will be cherished and remembered with deep gratitude. The authors would like to acknowledge and appreciate the contributions of the Postgraduate Institute of Science and the Department of Physics, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. Department of Physics and Electronics, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, UAE, and the Sivananthan Laboratories, Inc. USA. A.A.I.L., K.M.N.S.B. and B.S.D. acknowledge the funding provided by the Solar Edu-Training Project under the State Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation, Sri Lanka. H.C.S.P. and G.D. acknowledge the support of the Khalifa University internal funding CIRA-2021-071 (8474000416).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.I. Lakmal: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft. H.C.S. Perera: Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. K.M.N.S. Bandara: Data curation, Methodology. V.A. Seneviratne: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. T. Delclos: Resources. M. I. Helal: Resources. B.S. Dassanayake: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. G. Das: Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lakmal, A., Perera, H.C., Bandara, K. et al. Enhancement of solar cell efficiency through tailored electrodeposited seed layers and CdS: O surface texturing. Sci Rep 15, 36684 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20498-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20498-5