Abstract

The crowded intracellular environment influences RNA structure and interactions. While in-cell nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy allows atomic-resolution studies of RNA in living human cells, its application is limited due to rapid RNA degradation. In this study, we introduced an RNase inhibitor cocktail into living human cells and acquired in-cell NMR spectra of an RNA aptamer that strongly binds to HIV-1 Tat, both with and without a peptide derived from Tat. Introduction of the RNase inhibitor cocktail effectively suppressed RNA degradation. The significantly extended lifetime enabled the observation of intact in-cell NMR spectra for both the free aptamer and its complex with the peptide in living human cells at physiological temperatures. The in-cell NMR spectra of the free and complexed forms provided structural insights into RNA in living cells for understanding the mechanism of tight binding, including the formation of U-A-U base triples only in the complex. This was achieved without chemical modifications to the aptamer. The easily applicable and cost-effective nature of the RNase inhibitor cocktail makes this technique suitable for a wide range of in-cell NMR analyses for RNA. This innovation offers a pathway to unravel cellular processes and design novel RNA-focused medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

RNA aptamers are functional oligoribonucleotides that can recognize and strongly bind diverse target molecules. Using the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) method1, RNA aptamers have been developed for various targets2,3, including amino acids4, peptides5, proteins6, and even living cells7. Aptamers are versatile8 and have been used to inactivate9,10,11,12, activate13,14, purify15, detect16, and image17,18 target molecules. RNA aptamers can be introduced into and transcribed within living cells, making them promising tools for targeting intracellular molecules.

The intracellular environment is densely populated with biomolecules, leading to molecular crowding that alters the structural and physicochemical properties of proteins and nucleic acids19,20. Therefore, to utilize RNA aptamers intracellularly, analyzing their structural and physicochemical properties within living cells is crucial. In-cell nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is currently the only method capable of analyzing nucleic acid molecules at atomic resolution within living cells21,22,23,24. Our group successfully recorded the first in-cell NMR spectra of nucleic acids in living human cells25. This technique has not only detected and confirmed the formation of non-canonical nucleic acid structures within living cells25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 but has also characterized interactions between nucleic acids and their target molecules33,34,35,36,37,38. Furthermore, in-cell NMR has been used to study the dynamics of nucleic acid base-pair opening and closing, revealing differences between in vitro and in-cell environments20.

While in-cell NMR has been widely applied to DNA, its use in RNA research remains scarce owing to the rapid degradation of RNAs within living cell25,35,36,37,38. Previous studies have attempted to mitigate RNA degradation in living cells by chemically modifying the RNA sugar moiety or performing measurements at lower temperatures25,35,36,37. In contrast, our study introduces a simple and robust method to prevent RNA degradation within living cells. This approach enables the observation of in-cell NMR signals of RNA for extended periods without chemical modifications, even at physiological temperatures (37 °C).

To reduce RNA degradation within living cells, we co-delivered the RNA aptamers with an RNase-inhibitor cocktail consisting of SUPERase•In RNase Inhibitor and a recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitor. The cocktail was prepared by mixing the two inhibitors immediately before use. We selected this combination because the inhibitors have complementary target spectra and bind RNases in a 1:1 noncovalent manner39, providing broader protection in lysates and cells. Product details and concentrations are given in Materials and Methods.

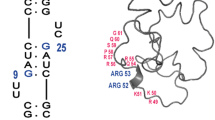

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of the RNase inhibitor cocktail in preventing the degradation of an RNA aptamer10,36,37,40,41 that strongly binds to and inactivates the HIV Tat protein (Fig. 1). This RNA aptamer specifically targets the arginine-rich motif (49RKKRRQRRRPPQG61) of the Tat protein and demonstrates remarkable affinity for the peptide containing only this sequence (Tat peptide), with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 10− 9 M 10,40,41. We previously analyzed the structure of this RNA aptamer in complex with Tat peptide in vitro40 and recently captured its structural changes upon Tat peptide binding in living human cells using in-cell NMR37.

Through the concurrent introduction of the RNA aptamer and the RNase inhibitor cocktail into living human cells, we effectively inhibited RNA aptamer degradation during in-cell NMR measurements and substantially extended the observation time for in-cell NMR spectra of RNA without chemical modifications, even at physiological temperatures (37 °C). Our method, which only requires adding a commercially available RNase inhibitor cocktail to the RNA solution before transfection, is simple. This method is clearly effective and provides a versatile approach for in-cell NMR studies on RNA.

Materials and methods

Preparation of RNA aptamer for HIV-1 and Tat-derived peptide

An RNA aptamer for HIV-1 Tat (5′-GGGAGCUUGAUCCCGGAAACGGUCGAUCGCUCCC-3′) was synthesized, purified, and desalted by Hokkaido System Science Co., Ltd. (Hokkaido, Japan). A Tat-derived arginine-rich peptide (49RKKRRQRRRPPQG61) was also synthesized, purified, and desalted by Toray Research Center, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

RNase inhibitor cocktail

We utilized two distinct RNase inhibitors: SUPERase•In™ RNase Inhibitor (Catalog number: AM2694, Invitrogen), and RNase Inhibitor (Code number: 315–08121, NIPPON GENE), both purchased as commercial products. We prepared an RNase inhibitor cocktail by mixing the two RNase inhibitors (the final concentration of each RNase inhibitor was 1 U/µL).

In vitro NMR spectroscopy

The RNA aptamer was dissolved in transfer buffer (TB: 25 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.0], 115 mM CH3COOK, 2.5 mM MgCl2) containing 5% D2O and 10 µM 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS) to a final concentration of 150 µM. The RNA solution was heated at 90 °C for 5 min and gradually cooled to 4 °C at a rate of − 1 °C/min (annealing) using a thermal cycler (TaKaRa RCR Thermal cycle Dice Gradient; Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). To prepare the RNA aptamer in complex, an equimolar amount of Tat peptide was added to the annealed RNA solution.

1D 1H-NMR spectra of the RNA aptamer in free, aptamerfree, or in complex with Tat peptide, aptamercomplex, with and without the RNase inhibitor cocktail (1 U of each/µL) were recorded at 10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C using the Band-Selective Optimized-Flip-Angle Short-Transient (SOFAST)42 technique with band-selective PC9 (90°) excitation and rSNOB (180°) refocusing pulses centered on the imino region to selectively excite and refocus solute ¹H spins while avoiding direct excitation of water. The number of scans was 1024, and the total acquisition time was 15 min. All NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker BioSpin AVANCE III HD 600 and 800 spectrometers equipped with a cryogenic probe.

In-lysate NMR spectroscopy

HeLa cells (purchased from Riken BRC Cell Bank, Ibaraki, Japan) were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin under 5% CO2 conditions at 37 °C. Then, cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Following centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, the cell pellets were suspended in Leibovitz’s L-15 media (80% v/v cell pellets). The cell suspension was sonicated for 2 h (cycles of 1 s ON and 1 s OFF) on ice, and the complete cell lysis was confirmed by microscopy. The cell slurry was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and defined as 80% cell lysate.

The annealed RNA, either 150 µM aptamerfree or 150 µM aptamercomplex (with 150 µM Tat peptide), in 1× TB containing D2O and DSS (final concentrations of 10% and 20 µM, respectively), was mixed with the 80% cell lysate, both in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail (1 U of each/µL). The final concentration of the cell lysate was 50%. The 1D in-lysate 1H-NMR spectra were recorded using the SOFAST technique. For each time point, the number of scans was 2048, and the acquisition time was 30 min.

Denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of RNA aptamer extracted from living cells

With or without the RNase inhibitor cocktail (1 U of each/µL), a suspension of HeLa cells (1 × 107 cells/70 µL) was electroporated using NEPA21 Super Electroporator (Nepa Gene Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan). The electroporation buffer contained 40 µM fluorescein (FAM)-labeled RNA aptamer and 960 µM unlabeled RNA aptamer, with or without 1 mM unlabeled Tat peptide. Electroporation followed our published protocol36,37; briefly, poring and transfer pulses were applied in a 2 mm-gap cuvette. After electroporation, the cells were divided into seven aliquots and incubated at 37 °C for different time periods (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 h) in microtubes; they were then washed with 500 µL of L-15 medium and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min. Each tube received 54 µL of lysis buffer (10 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 48.5 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA), and the cell pellets were disrupted by freezing and thawing five times. Subsequently, each sample was sonicated for 1 h (cycles of 1 s ON and 1 s OFF) on ice. The completion of cell lysis was confirmed by microscopy, and the sonicated samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, then 10 µL of each supernatant was analyzed by 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with 8 M urea. In the marker lane, 10 µL of 20 µM intact FAM-labeled RNA aptamer in TB was injected.

In-cell NMR spectroscopy using a bioreactor system

Either 1 mM aptamerfree or 1 mM aptamercomplex (1:1 complex prepared with excess amount of 2 mM Tat peptide) in TB containing 10% D2O and 20 µM DSS was introduced into HeLa cells with or without the RNase inhibitor cocktail (1 unit of each/µL), by electroporation26,33,43 using NEPA21 Super Electroporator system (Nepa Gene Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan), as described previously36,37.

As described previously31,36,37, a bioreactor system44,45, with slight modification, was used during the in-cell NMR measurements for supplying fresh L-15 media at a rate of 25 µL/min to the cells in the NMR tube to maintain the cells healthy. A glass tube with a 0.6 mm inner diameter was used as an inlet tube after being treated with 15% hydrogen peroxide and ethanol overnight. For two hours prior to the in-cell NMR experiment, the L-15 medium flow was started at the same rate to equilibrate the bioreactor.

The imino proton region of the 1D in-cell1H-NMR spectra at 37 °C was recorded using the SOFAST technique. For each time point, the number of scans was 2048 and the acquisition time was 30 min.

Results and discussion

In vitro1H-NMR spectra of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail

We first evaluated the effect of the RNase inhibitor cocktail on the NMR spectra of the RNA aptamer. In vitro 1D 1H-NMR spectra of the aptamerfree (Figure S1) and aptamercomplex (Figure S2) were recorded at different temperatures (10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C) in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail. The imino proton region of the1H-NMR spectra was examined. Peak intensities were slightly lower when the RNase-inhibitor cocktail was present. This is explained primarily by the dilution of RNA concentration upon adding the cocktail. Importantly, the spectra for both aptamerfree and aptamercomplex remained very similar regardless of the absence or presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail. We observed no marked chemical-shift changes, new peaks, or marked line broadening for either aptamerfree and aptamercomplex, indicating no detectable structural perturbation caused by the RNase inhibitor cocktail under these conditions.

Time course of in-lysate NMR spectra of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail.

Initially, we investigated the effect of an RNase inhibitor cocktail on the stability of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex. The 1D 1H-NMR spectra of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex probes were recorded in the presence of HeLa cell lysate, both with and without the RNase inhibitor cocktail, which is referred to as in-lysate NMR spectra later. The time-dependent progressions of the in-lysate NMR spectra for the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex were tracked from 0.5 h until complete degradation of the aptamer. Here, zero-hour time point represents the moment either the aptamerfree or aptamercomplex was mixed with the cell lysate.

In the absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the imino proton signals of aptamerfree and aptamercomplex progressively decreased in intensity and became undetectable after 2.5 h (Fig. 2A) and 3.0 h (Fig. 3A), respectively. The disappearance of the imino proton signals indicated the loss of hydrogen bonds due to aptamer degradation, although we cannot completely exclude the possibility of unfolding. In contrast, in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the imino proton signals of aptamerfree and aptamercomplex decreased but remained observable until 4.5 h (Fig. 2B) and 5.0 h (Fig. 3B), respectively. The aptamerfree and aptamercomplex gradually degraded even in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail. However, the degradation rates in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail were substantially lower than that in the absence of the inhibitor. These findings indicate that the RNase inhibitor cocktail confers a protective effect against degradation in the cell lysate, thereby prolonging the lifespans of aptamerfree and aptamercomplex. Consequently, the use of the RNase inhibitor cocktail extended the available time for conducting in-lysate NMR experiments on aptamerfree and aptamercomplex.

In-lysate1H-NMR spectra of the aptamercomplex. Imino proton spectra of 150 µM aptamercomplex in the absence (A) and presence (B) of the RNase inhibitor cocktail were recorded under 50% lysate at 37 °C. The acquisition time for each spectrum is 30 min.

Time course of degradation of the aptamer free and aptamer complex by denaturing gel electrophoresis in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail in living cells

Next, we investigated the effect of the RNase inhibitor cocktail on the degradation of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex in living HeLa cells using denaturing gel electrophoresis. The FAM-labeled aptamerfree and aptamercomplex, introduced into living HeLa cells via electroporation with or without the RNase inhibitor cocktail, was incubated at 37 °C. Subsequently, the cells were lysed and analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Without the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the band corresponding to the intact RNA aptamer was clearly observed, and its intensity was retained for up to 2 h. However, the band became faint at 3 h and was undetectable by 4 h (Fig. 4A). In contrast, in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the intact RNA aptamer band remained prominent up to 5 h and disappeared by 6 h (Fig. 4B). For the aptamercomplex, in the absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the band corresponding to the intact RNA aptamer was visible up to 3 h but disappeared by 4 h (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, the band for intact RNA aptamer remained visible up to 5 h (Fig. 5B). These observations suggested that the RNase inhibitor cocktail effectively retarded the degradation of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex in the cellular environment, potentially extending the timeframe for experimental manipulations in living cells.

Denaturing gel electrophoresis of FAM-labeled aptamerfree electroporated and incubated in HeLa cells in the absence (A) and presence (B) of the RNase inhibitor cocktail. All fractions were collected from HeLa cells after different incubation times at 37 °C. As a reference, a FAM-labeled RNA aptamer was applied in a marker lane.

Denaturing gel electrophoresis of FAM-labeled aptamercomplex electroporated and incubated in HeLa cells in the absence (A) and presence (B) of the RNase inhibitor cocktail. All fractions were collected from HeLa cells after different incubation times at 37 °C. As a reference, a FAM-labeled RNA aptamer was applied in a marker lane.

Time course of in-cell NMR spectra of the aptamer free and aptamer complex in the presence and absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail at physiological temperature.

To ascertain the effectiveness of the RNase inhibitor cocktail for in-cell NMR studies of RNA at physiological temperature (37 °C), we conducted in-cell NMR experiments on the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex both with and without the inhibitor cocktail. The time course of in-cell NMR spectra was recorded, starting at 1.5 h and continuing until the complete degradation of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex. The zero-hour time point marks the moment when either the aptamerfree or aptamercomplex was introduced into living HeLa cells via electroporation, with and without the RNase inhibitor cocktail.

In the absence of RNase inhibitor cocktail, the initial in-cell NMR spectrum failed to show clear imino proton signals from aptamerfree (Fig. 6A). In contrast, with the RNase inhibitor cocktail, in-cell NMR signals for all imino protons of aptamerfree were consistently observed up to 6 h (Fig. 6B).

For the aptamercomplex, in the absence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail, in-cell NMR signals from the imino protons were discernible only during the initial measurement at 1.5 h and disappeared by 2 h (Fig. 7A). In contrast, with the RNase inhibitor cocktail, in-cell NMR signals of all imino protons were distinctly visible at 4 h (Fig. 7B), with signals still observable at 7 h.

These findings demonstrated the potent protective effect of the RNase inhibitor cocktail against the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex degradation within living HeLa cells. Adding RNase inhibitor cocktail substantially increases the stability of the aptamerfree and aptamercomplex throughout the in-cell NMR experiments, effectively extending the feasible duration of such studies.

Significantly, signals of the aptamercomplex at approximately 14 ppm, specifically at 13.8 ppm and 13.9 ppm, which correspond to imino proton signals of U7 and U23 involved in two base triple structures at the Tat peptide binding sites37, were only apparent in the presence of the RNase inhibitor cocktail (Fig. 1, and 7B). These signals indicate that the RNA aptamer forms a stable complex with the Tat peptide37. The clear presence of these signals confirms that the RNA aptamer maintains a stable complex with the Tat peptide in living human cells even at 37°C. Previously, we validated the formation of the RNA aptamer-Tat peptide complex within living human cells by in-cell NMR at a lower temperature of 10 °C 37. Demonstrating this complex formation at physiological temperatures had been challenging due to rapid RNA degradation and limited time for recording in-cell NMR without the RNase inhibitor cocktail. This study, for the first time, provides direct evidence of the RNA aptamer-Tat peptide complex formation in living cells at 37°C.

Conclusions

In this study, because all in-cell NMR experiments were carried out in a continuously perfused bioreactor, extracellular contents do not accumulate during acquisition. The in-cell spectra are therefore most consistent with signals arising predominantly from aptamers in living cells.

We investigated the efficacy of an RNase inhibitor cocktail in enhancing the stability and longevity of RNA aptamers during in-lysate and in-cell NMR experiments at 37 °C. The RNase inhibitor cocktail notably extended the lifespan of the RNA aptamer, thereby increasing the available time window for both in-lysate and in-cell NMR analyses. This extension is pivotal for acquiring two-dimensional in-cell NMR spectra of isotopically labeled RNAs at 37 °C, such as 1-15N HSQC and 1-13C HSQC, which can yield enhanced structural insights into RNA within the living cellular environment36.

Notably, with the RNase inhibitor cocktail, we achieved the first in-cell NMR spectrum of a ligand-free RNA aptamer at physiological temperature. To understand the mechanism behind tight binding, it is necessary to examine not only the aptamer in its complex state but also in its free state. Therefore, the successful recording of in-cell NMR spectra in the free state is important.

In this study, all the RNase inhibitor cocktail contained both SUPERase•In™ RNase Inhibitor and a recombinant RNase Inhibitor (NIPPON GENE). We did not test either reagent alone. We used the combination because the two inhibitors act on different RNase families, which broadens protection in lysates and cells.

Our straightforward and practical approach holds promise for a broad range of applications, potentially benefiting the in-cell NMR study of biologically functional RNAs, such as ribozymes, microRNAs, non-coding RNAs, and RNA-based therapeutic modalities, including siRNAs and antisense RNAs.

Our methodology has provided concrete evidence of aptamer-peptide complex formation within living human cells at physiological temperature, 37 °C, through in-cell NMR spectra. This study underscores the potential of RNA aptamers as candidates for RNA-based therapeutics, especially in HIV treatment, paving the way for their use in developing anti-HIV drugs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

12 November 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Omar Eladl was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of chemistry, New York University, New York, NY 10012, USA.’ The original Article has been corrected.

References

Gold, L. S. E. L. E. X. How it happened and where it will go. J. Mol. Evol. 81, 140–143 (2015).

Tuerk, C. & Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 (1990).

Wu, Y. X. & Kwon, Y. J. Aptamers: the evolution of SELEX. Methods 106, 21–28 (2016).

Jiang, F., Kumar, R. A., Jones, R. A. & Patel, D. J. Structural basis of RNA folding and recognition in an AMP–RNA aptamer complex. Nature 382, 183–186 (1996).

Varshney, A. et al. Identification of an RNA aptamer binding hTERT-derived peptide and inhibiting telomerase activity in MCF7 cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 427, 157–167 (2017).

Urvil, P. T. et al. Selection of RNA aptamers that bind specifically to the NS3 protease of hepatitis C virus. Eur. J. Biochem. 248, 130–138 (1997).

Shangguan, D. et al. Identification of liver Cancer-Specific aptamers using whole live cells. Anal. Chem. 80, 721–728 (2008).

Kang, K. N. & Lee, Y. S. RNA aptamers: A review of recent trends and applications. in Future Trends in Biotechnology (ed Zhong, J. J.) vol. 131 153–169 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, (2012).

Sun, M. et al. Aptamer blocking strategy inhibits SARS-CoV‐2 virus infection. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10266–10272 (2021).

Yamamoto, R. et al. A novel RNA motif that binds efficiently and specifically to the Tat protein of HIV and inhibits the trans -activation by Tat of transcription in vitro and in vivo. Genes Cells. 5, 371–388 (2000).

Mashima, T. et al. Anti-prion activity of an RNA aptamer and its structural basis. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1355–1362 (2013).

Murakami, K. et al. An RNA aptamer with potent affinity for a toxic dimer of amyloid β42 has potential utility for histochemical studies of alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 4870–4880 (2020).

Tsukakoshi, K. et al. G-quadruplex-forming aptamer enhances the peroxidase activity of myoglobin against luminol. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 6069–6081 (2021).

Ueki, R. et al. A chemically unmodified agonistic DNA with growth factor functionality for in vivo therapeutic application. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2801 (2020).

Nair, R., Haimovich, G. & Gerst, J. An Aptamer-based mRNA affinity purification procedure (RaPID) for the identification of associated RNAs (RaPID-seq) and proteins (RaPID-MS) in yeast. BIO-Protoc 12, (2022).

Findeiß, S., Etzel, M., Will, S., Mörl, M. & Stadler, P. Design of artificial riboswitches as biosensors. Sensors 17, 1990 (2017).

Yang, L. Z. et al. Dynamic imaging of RNA in living cells by CRISPR-Cas13 systems. Mol. Cell. 76, 981–997e7 (2019).

Sato, S. et al. Live-Cell imaging of endogenous mRNAs with a small molecule. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1855–1858 (2015).

Nakano, S., Miyoshi, D. & Sugimoto, N. Effects of molecular crowding on the Structures, Interactions, and functions of nucleic acids. Chem. Rev. 114, 2733–2758 (2014).

Yamaoki, Y. et al. Shedding light on the base-pair opening dynamics of nucleic acids in living human cells. Nat. Commun. 13, 7143 (2022).

Nishida, N., Ito, Y. & Shimada, I. In situ structural biology using in-cell NMR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 1864, 129364 (2020).

Luchinat, E., Cremonini, M. & Banci, L. Radio signals from live cells: the coming of age of In-Cell solution NMR. Chem. Rev. 122, 9267–9306 (2022).

Theillet, F. X. In-Cell structural biology by NMR: the benefits of the atomic scale. Chem. Rev. 122, 9497–9570 (2022).

Yamaoki, Y., Nagata, T., Sakamoto, T. & Katahira, M. Recent progress of in-cell NMR of nucleic acids in living human cells. Biophys. Rev. 12, 411–417 (2020).

Yamaoki, Y. et al. The first successful observation of in-cell NMR signals of DNA and RNA in living human cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 2982–2985 (2018).

Dzatko, S. et al. Evaluation of the stability of DNA i-Motifs in the nuclei of living mammalian cells. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2165–2169 (2018).

Bao, H. L., Liu, H. & Xu, Y. Hybrid-type and two-tetrad antiparallel telomere DNA G-quadruplex structures in living human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 4940–4947 (2019).

Dzatko, S., Fiala, R., Hänsel-Hertsch, R., Foldynova-Trantirkova, S. & Trantirek, L. Chapter 16. In-cell NMR spectroscopy of nucleic acids. in New Developments in NMR (eds (eds Ito, Y., Dötsch, V. & Shirakawa, M.) 272–297 (Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/9781788013079-00272. (2019).

Bao, H. L. & Xu, Y. Telomeric DNA–RNA-hybrid G-quadruplex exists in environmental conditions of HeLa cells. Chem. Commun. 56, 6547–6550 (2020).

Bao, H. L., Masuzawa, T., Oyoshi, T. & Xu, Y. Oligonucleotides DNA containing 8-trifluoromethyl-2′-deoxyguanosine for observing Z-DNA structure. Nucleic Acids Res. gkaa505 https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa505 (2020).

Sakamoto, T., Yamaoki, Y., Nagata, T. & Katahira, M. Detection of parallel and antiparallel DNA triplex structures in living human cells using in-cell NMR. Chem. Commun. 57, 6364–6367 (2021).

Cheng, M. et al. Thermal and pH stabilities of i-DNA: confronting in vitro experiments with models and In‐Cell NMR data. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10286–10294 (2021).

Krafcikova, M. et al. Monitoring DNA–Ligand interactions in living human cells using NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13281–13285 (2019).

Krafčík, D. et al. Towards profiling of the G-Quadruplex targeting drugs in the living human cells using NMR spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6042 (2021).

Schlagnitweit, J. et al. Observing an antisense drug complex in intact human cells by in-Cell NMR spectroscopy. ChemBioChem 20, 2474–2478 (2019).

Eladl, O., Yamaoki, Y., Kondo, K., Nagata, T. & Katahira, M. Detection of interaction between an RNA aptamer and its target compound in living human cells using 2D in-cell NMR. Chem. Commun. 59, 102–105 (2023).

Eladl, O., Yamaoki, Y., Kondo, K., Nagata, T. & Katahira, M. Complex formation of an RNA aptamer with a part of HIV-1 Tat through induction of base triples in living human cells proven by In-Cell NMR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9069 (2023).

Broft, P. et al. In-Cell NMR spectroscopy of functional riboswitch aptamers in eukaryotic cells. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 865–872 (2021).

Blackburn, P. Ribonuclease inhibitor from human placenta: rapid purification and assay. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 12484–12487 (1979).

Matsugami, A. et al. Structural basis of the highly efficient trapping of the HIV Tat protein by an RNA aptamer. Structure 11, 533–545 (2003).

Harada, K. et al. RNA-Directed amino acid coupling as a model reaction for primitive coded translation. ChemBioChem 15, 794–798 (2014).

Schanda, P., Kupče, Ē. & Brutscher, B. SOFAST-HMQC experiments for recording Two-dimensional deteronuclear correlation spectra of proteins within a few seconds. J. Biomol. NMR. 33, 199–211 (2005).

Theillet, F. X. et al. Structural disorder of monomeric α-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 530, 45–50 (2016).

Kubo, S. et al. A Gel-Encapsulated bioreactor system for NMR studies of Protein–Protein interactions in living mammalian cells. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 1208–1211 (2013).

Breindel, L., DeMott, C., Burz, D. S. & Shekhtman, A. Real-Time In-Cell nuclear magnetic resonance: Ribosome-Targeted antibiotics modulate quinary protein interactions. Biochemistry 57, 540–546 (2018).

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants to M.K. (23H02419, 23H04069, and 24K21946), T.N. (20K06524 and 23K05664), and Y.Y. (22K05314), an AMED grant to M.K. (24fk0410048h0103), a collaborative research program grant from the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University to T.N. (NMRCR-24-03), grants from the joint usage/research programs of the Institute of Advanced Energy, Kyoto University to M.K. (ZE2024A-15), T.N. (ZE2024A-06 and ZE2024A-27), and Y.Y. (ZE2024A-11), the Hattori Hokokai Foundation to Y.Y., the Japanese Government (MEXT) Scholarship to O.E.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, O.E. and Y.Y.; methodology, O.E. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, O.E. and Y.Y.; investigation, O.E. and Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, O.E., Y.Y., T.N., and M.K.; writing—review and editing, O.E., Y.Y., T.N., and M.K.; supervision, M.K.; funding acquisition, O.E., Y.Y., T.N., and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eladl, O., Yamaoki, Y., Nagata, T. et al. In-cell NMR spectra of chemically unmodified RNA at physiological temperature with extended lifetime through RNase inhibitor cocktail in living human cells. Sci Rep 15, 36397 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20519-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20519-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

In-cell NMR spectroscopy: advancements, applications, challenges, and future directions in structural biology

Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine (2025)