Abstract

Tracing soluble radionuclides is critical for understanding the mechanisms underlying the transport of soluble materials in marine environments. In the present study, we investigated the surface distribution of the concentrations (activities) of 134Cs, 137Cs, 226Ra, and 228Ra in the northern North Pacific, Bering Sea, and Arctic regions from 2017 to 2024. The 226Ra and 228Ra concentrations distinctively separated the surface into the low-226Ra subtropical–transition and high-226Ra subarctic current areas in the northern North Pacific and the 228Ra-rich eastern shelf and 228Ra-poor western basin areas in the Bering Sea. In 2022–2024, the surface concentrations of the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident-derived 137Cs (FD-137Cs) ranged between 0.4 and 1.5 mBq/L, with the highest values in the eastern shelf of the Bering Sea. The lateral distribution of 137Cs concentrations is predominantly ascribed to the preferential inflow of FD-137Cs to the Bering Sea along with the upstream Alaskan Coastal Current. After the steep increase from 2015 to 2017, the temporal variation in FD-137Cs concentrations in the Bering Sea was small (0.8–1.5 mBq/L from 2018 to 2024). This could be attributed to the continual transport of FD-137Cs from the Alaskan Gyre area via the Aleutian Islands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current systems play important roles in the transport of various materials in marine environments. In addition to physical parameters such as salinity and temperature, chemical tracers in seawater are often used to investigate the functions of current systems and material transport. Among these chemical tracers, an anthropogenic radionuclide, 137Cs, with a half-life of 30.2 years, was introduced into seawater by a global fallout caused by atmospheric nuclear test explosions conducted in the mid-1950s to the early 1960s and leakage from nuclear power plant accidents1,2,3. The 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) accident resulted in the release of substantial quantities of 137Cs and 134Cs (half-life: 2.06 years) (~ 15–20 PBq each)4,5 as well as other radionuclides into the northwestern North Pacific.

Numerous studies on the transport of 137Cs and 134Cs have been conducted around the Japanese Archipelago and in the transition area between the Kuroshio Extension and westward subarctic currents, following the FDNPP accident6,7,8,9. However, owing to the lack of adequate radiocesium data, the transport patterns of FDNPP accident-derived radiocesium in subarctic and arctic areas remain unclear. Currently, the concentrations of short-lived 134Cs in seawaters, originating solely from the FDNPP accident10,11, have reduced to levels below the detection limit (< ~ 0.01 mBq/L) even when employing high-precision and high-sensitivity low-background γ-spectrometry. Nevertheless, FDNPP accident-derived 137Cs (FD-137Cs) concentration continues to serve as a useful chemical tracer for investigating radionuclide distribution in current systems.

Among naturally occurring and soluble radium isotopes, 226Ra (half-life: 1600 years) is conventionally used as a tracer to study the mixing of subarctic and subtropical currents12,13. Furthermore, 228Ra (half-life; 5.75 years) is generally used to trace the circulation of seawater that has undergone interactions with coastal/shallow shelf sediments and transported to offshore areas14. Particularly, the lateral distribution of 228Ra concentrations has been employed to study the transport patterns of FD-radiocesium in the marginal seas in the northwestern North Pacific Ocean15.

In the present study, the lateral distribution of the concentrations of 134Cs (in and before 2022), 137Cs, 226Ra, and 228Ra in the northern North Pacific was examined, particularly focusing on the Bering Sea from 2017 to 2024, using low-background γ-spectrometry, and the ocean- and sea-scale transport patterns of FD-137Cs were also investigated. The actual measurement data could offer valuable insights into the transport mechanisms of soluble materials (dispersion, mixing, paths, and their time-scale) in oceanic systems.

Results

226Ra–228Ra distributions and current systems

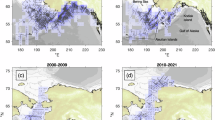

A plausible current model for this study and the locations of surface seawater sampling sites are presented in Fig. 1. Along the northern front of the Kuroshio Extension Current, an eastward transition current circulates at approximately 40°–45°N toward the western American Coast, and a section of this current diverges northward, forming the counterclockwise Alaskan Gyre (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, the westward Alaskan Stream (AS) and Alaskan Coastal Current (ACC) circulate along the eastern Aleutian Islands16, although their current patterns remain unclear. Upon entering the Bering Sea, currents migrate along and on the eastern shallow shelf (maximum depth of 180 m) as the shelf slope current and ACC, and they eventually exit into the Chukchi Sea via the Bering Strait18. On the western basin area, there are counterclockwise surface currents that mainly flow back into the Pacific and migrate as the East Kamchatka Current19.

Between 2017 and 2024, surface seawaters (KH17, OS23, and MR19–24 samples) were collected over the northern North Pacific, Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas (Fig. 1b). The sample descriptions, salinity, and concentrations of the radionuclides in the collected seawater samples are shown in Table S1. The longitudinal profiles of salinity and 226Ra and 228Ra concentrations are presented in Fig. 2. Although surface salinity was high and increased southward from ~ 43° N in the Pacific (33.5–35.5), this was constant northward (~ 32.5 at 44°–58° N) (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the salinity exhibited minor variations in the north of the Bering Sea (30–32.5), and the variation was significant in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas in the Arctic side (16–32).

Longitudinal profiles of (a) salinity, (b) 226Ra, (c) 228Ra concentrations, and (d) 228Ra concentrations against salinity in KH17 (no radium data), Mu1820, OS23, MR19, and MR22–24 waters.

The surface 226Ra concentrations in the subarctic area in the Pacific were high, primarily owing to the long-term uplifting of high-226Ra bottom water based on the long half-life (1600 years)13,21. Notably, 226Ra concentrations distinctively separated the surface water along transects MR23 and MR24 into low-226Ra eastward subtropical (27°–40°N), high-226Ra westward subarctic current areas (45°–55°N) with a transition area (40°–45°N) between them, and a wide ranging-226Ra Bering Sea–Chukchi Sea area (55°–75°N) (Fig. 2b). 226Ra concentrations (< ~ 0.5 mBq/L) at the surface in a few OS23 sites close to the Bering Strait (63°–65°N) were exceptionally lower than those at 15–45 m depths (1.4–2 mBq/L; unpublished data in our laboratory). This observation may indicate the local mixing of low-226Ra waters on the surface (e.g., Chukchi Sea side waters), with the underlying cause remaining unclear22.

Surface 228Ra concentrations of MR22–24 waters widely ranged from < 0.1 to 3.8 mBq/L (Fig. 2c). In the Pacific, the small 228Ra concentration peak (0.3–0.4 mBq/L) was observed at 42°–45°N in transects MR23 and MR24. This concentration level is similar to that observed in the upstream region in/around the transition current and is indicative of the effects of 228Ra supplied from the shallow shelf of the East China Sea and off Japanese Archipelago (e.g., 0.3–0.5 mBq/L along the coast of central Honshu23 and offshore of southwestern Hokkaido24 in the Pacific side).

Comparing the lower 228Ra concentrations in the waters of the subarctic of the Pacific and western basin area of the Bering Sea (< ~ 0.5 mBq/L), 228Ra concentrations in the waters of the eastern shelf area were higher (0.2–2.2 mBq/L). This could be primarily attributed to the continual supply of 228Ra from the eastern shallow shelf area20. The 228Ra concentrations in 2018 (Mu18 samples)20 shifted to the low 228Ra side, owing to the different expedition route (i.e., along the offshore area of the western coast of the Bering Sea) (Fig. 2c). The surface of the Bering Sea plausibly separated into the low-salinity and 228Ra-rich eastern shelf slope current and ACC (hereafter, shelf water) and high-salinity and 228Ra-poor western basin currents. As shown in Fig. 2d, the study area was divided into six sections (sct): The 226Ra-poor subtropical–transition and 226Ra-rich subarctic areas (sct-tP and -aP) and in/around the Alaskan Gyre (sct-A) in the North Pacific, 228Ra-rich eastern shelf and 228Ra-poor western basin areas (sct-sB and -bB) in the Bering Sea, and Chukchi and Beaufort Seas with wide variations in salinity and 226Ra and 228Ra concentrations (sct-C).

Global fallout- and total-137Cs concentrations

The longitudinal distributions of global fallout-derived 137Cs (GF-137Cs), total-137Cs, and FD-137Cs concentrations on the sampling dates are presented in Fig. 3a–c. Reflecting the distribution of former nuclear test explosion sites, particularly in the subtropical northern North Pacific25 and subsequent 137Cs transport with currents, GF-137Cs concentrations in subarctic currents were lower than those in subtropical currents. For example, in the southwestern Okhotsk Sea, GF-137Cs concentrations in subtropical and subarctic currents were 1.5 and 1.0 mBq/L in 2009, respectively12, which are consistent with the concentrations corrected in March 2011 using 134Cs concentrations in the northwestern North Pacific (1.5 and 0.9 mBq/L, respectively)24. Additionally, the concentrations directly following the 2011 accident in the Bering Sea and Alaskan Gyre were estimated to be ~ 1 mBq/L7. Assuming the GF-137Cs concentration in March 2011 and effective half-life in the subtropical and subarctic areas to be 1.5 and 1 mBq/L and 16.5 and 13.7 years26, respectively, subtropical and subarctic GF-137Cs concentrations from 2017 to 2024 were calculated to be between 0.5 and 0.9 mBq/L (Fig. 3a). GF-137Cs concentrations in the transition area were tentatively estimated based on 0.7 of the fraction of subtropical current from the salinity and 226Ra concentrations. Although GF-137Cs concentrations in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas were higher than those in the Bering Sea before the arrival of FD-137Cs (~ 1.5 mBq/L in 2010)7, the GF-137Cs concentrations are unknown because the data, including on the effective half-life, are lacking.

The FDNPP is in close proximity to the upstream of the transition current. Thus, 137Cs-rich water masses from the ambient of FDNPP (hereafter, 137Cs-core) were preferentially transported to the surface at 145°–150° E between 2011 and 2012 (10–15 mBq/L) along with the drastic transition current at 35°–40° N. Subsequently, the 137Cs-core reached the central North Pacific (8–10 and 4–8 mBq/L in 2012 and 2014, respectively)6,27,28. The significant spatiotemporal variation in total-137Cs concentrations indicated the eastward transport of the 137Cs-core, and the transport speeds in the western transition current and eastern areas were estimated to be 2200 and 1200 km/y, respectively28.

The high-137Cs area (maximum ~ 10 mBq/L) was observed at the core center (~ 45°N and ~ 145°W) of the Alaskan Gyre in 201529. Subsequently, the surface concentrations of total-137Cs steeply decreased offshore (60°–43° N) at ~ 145° W (4–2 mBq/L) and in 170°–130° W at ~ 47° N (5–1 mBq/L) along latitudinal and longitudinal transects of KH17 in 2017 (Fig. 3b). The 137Cs-core shifted to the West America and Alaskan coasts (~ 5 and ~ 4 mBq/L, respectively) from 2015 to 2017.

The total-137Cs concentrations in MR23 and MR24 waters in sct-tP were 1.2–1.7 mBq/L. The maximum 137Cs concentration in the Pacific was observed in the transition current along transects MR23 and MR24 (~ 1.6 mBq/L at ~ 42°N), accompanied by a high 228Ra concentration. This 137Cs value is approximately equivalent to that in the upstream coastal area of the Japanese Archipelago, where the concentrations have shown minor variations since 2013 (~ 2 mBq/L)30. The total-137Cs concentrations gradually decreased southward. In addition to the minimal variations in salinity and 226Ra concentrations (Fig. 2a, b), the 137Cs concentrations of waters in sct-aP exhibited small variation in the range of 1–1.2 mBq/L, and the 137Cs and 228Ra concentrations showed minimum levels, including the AS area along the Aleutian Islands. The 137Cs concentrations of the waters in the Bering Sea increased northward from 0.8 to 1.7 mBq/L. Notably, water samples with higher 137Cs concentrations in sct-sB exhibited higher 228Ra concentrations, distinctively separating to the shelf side waters (Fig. 3a), despite the distinct supply processes of 137Cs and 228Ra.

The total-137Cs concentrations varied widely in sct-C, ranging from 0.5 to 1.7 mBq/L. Despite the broad range, the highest 137Cs concentrations of MR and OS samples in the Chukchi Sea were comparable to those in sct-sB, indicating the inflow of 137Cs through the Bering Strait. 137Cs concentrations in sct-C in 201911 showed a positive correlation with 228Ra concentration data obtained in the present study (correlation coefficient, r2 = 0.91 with five samples) (Table S1). This is ascribed to dilution likely owing to the mixing of the Siberian Coastal Current following passage through the Bering Strait. Additionally, total-137Cs concentrations in MR22 waters off the Alaskan Coast in sct-C were negatively correlated with 228Ra concentrations (coefficient, r2 = 0.62 with five samples) (Table S1). The low 137Cs concentrations in 2022 primarily resulted from the effect of the 137Cs-poor and 228Ra-rich (and 226Ra-rich and low-salinity) Mackenzie River (e.g., via suspended sediment desorption)31.

FDNPP-137Cs concentrations

The concentrations of FD-137Cs (i.e., [total-137Cs]–[GF-137Cs]) were estimated based on the following assumptions: (i) homogeneous distribution of GF-137Cs over the subtropical and subarctic areas, including the Bering Sea, and (ii) a negligible effect of the mixing of Arctic seawaters (Fig. 3c). FD-137Cs concentrations in MR22–24 waters were 0.4–1.5 mBq/L. FD-137Cs concentrations were higher at ~ 42° N in sct-tP, possibly reflecting the transport of the 137Cs-core with the transition current, even though the concentrations steeply decreased to approximately 3/20 of those recorded for the core at ~ 160°E–170° W in 201228. Furthermore, the effect of FD-137Cs gradually decreased southward from 0.8 to 0.4 mBq/L. FD-137Cs concentrations in sct-aP were low, with minor variation (0.5–0.7 mBq/L). The concentration level in sct-bB gradually increased northward, and the maximum concentrations were observed at ~ 60°–65° N in sct-sB. Additionally, even at a narrow longitudinal width, the FD-137Cs concentrations in the north Bering Sea exhibited wide variation (e.g., 0.7–1.1 mBq/L at ~ 65° N) in 2022–2024. The distributions of FD-137Cs distinctly separated, as follows: sct-aP (0.6–0.8 mBq/L) < sct-bB (0.8–1.0 mBq/L) < sct-sB (1.0–1.5 mBq/L) (Fig. 3c).

For a direct comparison of the effect of FD-137Cs concentrations, the concentrations were re-corrected to July 2017 (sampling timing for KH17) using the effective half-life (Fig. 3d). FD-137Cs concentrations re-corrected in sct-aP (43°–53° N) along transect MR24 were approximately 10% lower than those at the same latitude along transect MR23, and the difference was not explainable based only on the radioactive-decay (~ 5% decrease per year). Therefore, this result may be predominantly due to a decrease in the contribution of the expanded 137Cs-core to the northwestern North Pacific17.

Discussion

The temporal variations in total-137Cs, 134Cs, and FD-137Cs concentrations, and fractions of FD-137Cs in the Bering Sea and AS are presented in Fig. 4. Despite the lack of 137Cs concentration data in 2016 and unfixed expedition routes during this period (particularly in the western region of the Bering Sea in 2018)20, the total concentrations of 137Cs in the Bering Sea appear to have steeply increased from 2015 to 2018 (Fig. 4a). Subsequently, total-137Cs concentrations decreased slightly from 2018 to 2024, although the 137Cs concentrations showed wide annual variations.

Temporal variations in (a) total-137Cs concentrations on the sampling date, (b) 134Cs concentrations on the FDNPP accident date, (c) FD-137Cs concentrations on the sampling date, (d) FD-137Cs concentrations re-corrected to 2017, and (e) fractions of FD-137Cs in MR19–24 and OS23 waters in the Bering Sea and Alaskan Stream along with previous data11,20,32, compared with KH17. Two waters in 2020 have been tentatively classified as sct-sB, based on their salinity and sampling locations.

The temporal variation in the concentrations of 134Cs, attributed primarily to the FDNPP accident, steeply increased from 2015 to 2018 with minor variations observed from 2018 to 2022 (Fig. 4b). Notably, after 2018, the concentrations of 134Cs in sct-sB were higher than those in sct-bB, thereby directly indicating differences in the currents. The features of the spatiotemporal variations in FD-137Cs concentrations (Fig. 4c) were found to be consistent with those in total-137Cs and 134Cs concentrations. In contrast to the steep decline in FD-137Cs concentrations along the transition current area after passing the core in sct-tP (2012–2014)28, in both sct-sB and -bB, there were only minor temporal variations from 2018 to 2024 (1–1.7 and 0.7–1.5 mBq/L, respectively), despite the wide annual variations. Although waters in 2018 were from the western coast characterized by the lowest 228Ra concentrations (Fig. 2c), the FD-137Cs concentrations in these waters were the highest, which could indicate the arrival of the center of the FD-137Cs core, as observed off southeastern coast of Hokkaido in 202033.

As shown in Fig. 4d, for both assessed sections, the FD-137Cs concentrations re-corrected to July 2017 were characterized by either no decline or the least decline from 2018 to 2024 (mean, 1.64 mBq/L in sct-sB and 1.28 mBq/L in sct-bB). In the Bering Sea, the fractions of FD-137Cs to total-137Cs also remained approximately constant in each section during the period from 2018 to 2024, following the arrival of the core. Despite the short residence time of the subtropical Kuroshio Current in the southern Japan Sea (a few months)23, FD-137Cs and 134Cs concentrations were also characterized by minor temporal variations subsequent to the inflow of the FD-radiocesium-affected Kuroshio Current from 2014 to 201930,34, thus providing evidence to indicate the occurrence of large reservoirs of FD-137Cs in the Kuroshio area.

The concentrations and fractions of FD-137Cs in the Bering Sea and AS were within the range of sct-A (0.2–4.6 mBq/L and 0.38–0.86, respectively) (Fig. 4d, e). FD-137Cs concentrations in waters of the ACC area along transect KH17 (3.6 and 3.2 mBq/L at sites CL12 and CL14 at ~ 60°N, respectively; Table S1) were over two-fold higher than those in waters in sct-sB, along with high fractions (0.8). Additionally, assuming the high current speeds of the ACC and AS (4.4–11.3 × 103 km/y)35, the 137Cs-core in the northern part of sct-A in 2017 was transported immediately to sct-sB in 2018 (or 2017). Consequently, the most reasonable explanation for the spatiotemporal features of the FD-137Cs concentrations in sct-sB is that FD-137Cs was continually supplied with the ACC from the large-scale reservoirs (e.g., the counterclockwise Alaskan Gyre and the surrounding currents) via passes of the eastern Aleutian Islands, at least during the 8-year period from 2017 to 202416,35. The steep increase in FD-137Cs concentrations in the Bering Sea from 2015 to 2018 indicates an increase in 137Cs concentrations in the ACC and/or the spread of FD-137Cs within a few years. Subsequently, the ACC-dominated currents were followed by the mixing of 228Ra-rich waters (and/or supply of 228Ra) on the shallow shelf within the Bering Sea, and thus a mixing with shelf waters may have contributed to a decline in FD-137Cs concentrations in the ACC within sct-sB from ~ 3.5 to 1.6 mBq/L (Fig. 4c).

The minor temporal variations in FD-137Cs concentrations in sct-bB from 2018 to 2024 may be attributable to the continual supply of FD-137Cs (Fig. 4d). However, given that the concentrations in sct-bB were distinctly lower than those in sct-sB, this would tend to indicate that the dilution effect in sct-bB was greater than in sct-sB along the Aleutian Islands and/or after entering the Bering Sea. Furthermore, there appeared to be a minimal exchange of waters between sct-bB and -sB within the Bering Sea, as evidenced from the clear distinction in 228Ra concentrations between both sections, particularly in the northern Bering Sea (Fig. 2d).

In contrast, the re-corrected concentrations and fractions in the AS appeared to show a gradual decline from 2019 to 2024, being lower than those in the Bering Sea, although the data were insufficient to provide conclusive evidence (Fig. 4d, e). Despite the mixing of basin and shelf waters in the Bering Sea, the extent of the lateral dilution of FD-137Cs in the AS was higher than that in the Bering Sea.

On the basis of the observed spatiotemporal variations in FD-137Cs (Fig. 4), it is reasonable to assume that the source currents in the AS differ from those in the Bering Sea. A plausible candidate for the low FD-137Cs waters with the lowest 228Ra concentrations in the AS-dominated area is from offshore in sct-A (~ 1–1.5 mBq/L and 0.7 in 2017), and it is conceivable that the FD-137Cs concentrations in the AS and upstream region may have declined from 2018.

In conclusion, the spatiotemporal measurement data of FD-137Cs recorded in the present study indicate differences in the sources and transport paths between the currents in the Bering Sea and AS (e.g., large effect of the ACC in the Bering Sea) and the retention mechanism of FD-137Cs in the Bering Sea and ACC from 2018. Collectively, these current systems can provide a basis for predicting the transport, dispersion, and mixing patterns of different types of soluble contaminants across the northern North Pacific from the western coast of North America (Alaska) to the eastern coast of North Asia (Siberia), including the Bering Sea. However, the residence time and mixing patterns of surface waters within the Bering Sea (> 1 year of the shelf slope current)36 and in and around the Alaskan Gyre have yet to be sufficiently established. Further clarification regarding the circulation of FD-137Cs could be achieved by characterizing the continual research. This study is currently being conducted by our research group.

Materials and methods

The seawater samples were collected along the R/Vs Hakuho Maru (KH17 in 2017), Oshoro Maru (OS23 in 2023), and Mirai (MR22–24 in 2022–2024) expedition routes across the northern North Pacific between 2017 and 2024 (Fig. 1b). A total of 77 samples (approximately 20–40 L each) were collected at depths from 0 to 13 m using a conductivity–temperature–depth rosette with Niskin bottles or a pump system. The pre-concentration of radiocesium was conducted by placing a resin in 40 L aliquots of KH17 seawater samples onboard during the expedition and MR22 in a land laboratory37.

In another land laboratory, after adjusting the pH to 1, radiocesium was separated quantitatively via co-precipitation by adding 0.26–0.52 g of CsCl and 4.0–8.0 g of ammonium phosphomolybdate (AMP) to ~ 20–40 L aliquots of the unfiltered seawater samples38. A minimally Ra-contaminated Ba carrier was added to the supernatant after AMP treatment or in untreated waters, and BaSO4 was precipitated along with the radium isotopes39. The chemical yields were 90–93% for radiocesium and 92–100% for the radium isotopes, based on the yields of the AMP/Cs (with a 95% mean removal yield of radiocesium from seawater during AMP treatment) and BaSO4 fractions, respectively.

Low-background γ-spectrometry was performed for all AMP/Cs and BaSO4 samples within approximately 2–4 counting days for radiocesium and radium isotopes, using completely shielded germanium detectors at the Ogoya Underground Laboratory (270 m water-depth equivalent), Ishikawa, Japan40, except for some AMP/Cs samples in KH17 for ground-level γ-spectrometry. The 134Cs (605 keV), 137Cs (662 keV), 226Ra (214Pb; 295 and 352 keV), and 228Ra (228Ac; 338 and 911 keV) concentrations were calibrated using the AMP/Cs and BaSO4 mockup samples. The analytical precision was 10–50% for 134Cs, 2–20% for 137Cs, 2–10% for 226Ra, and 10–50% for 228Ra, based on the standard deviation of the counting statistics, and under analytical conditions, the detection limit for 228Ra was set at ~ 0.1 mBq/L.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Livingston, H. D. & Povinec, P. P. Anthropogenic marine radioactivity. Ocean Coast Manag. 43, 689–712 (2000).

Duran, E. B., Povinec, P. P., Fowler, S. W., Airey, P. L. & Hong, G. H. 137Cs and 239+240Pu levels in the Asia-Pacific regional seas. J. Environ. Radioact. 76, 139–160 (2004).

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Worldwide Marine Radioactivity Studies (WOMAR) 187 (IAEA, 2005).

Tsubono, T. et al. Evaluation of radioactive cesium impact from atmospheric deposition and direct release fluxes into the North Pacific from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Deep Sea Res. I I(115), 10–21 (2016).

Buesseler, K. et al. Fukushima Daiichi-derived radionuclides in the ocean: Transport, fate, and impacts. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9, 173–203 (2017).

Kumamoto, Y. et al. Southward spreading of the Fukushima-derived radiocesium across the Kuroshio Extension in the North Pacific. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04276 (2014).

Kumamoto, Y. et al. Meridional distribution of Fukushima-derived radiocesium in surface seawater along a trans-Pacific line from the Arctic to Antarctic Oceans in summer 2012. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4439-0 (2016).

Nishikawa, H. et al. Surface water pathways in the subtropical–subarctic frontal zone of the western North Pacific. Prog. Oceanogr. 199, 102691 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Spatiotemporal variations in vertical profiles of Fukushima-derived 137Cs in the Kuroshio-Oyashio confluence region from 2011 to 2018: Implications for local water mass dynamics and basin-scale circulations. Prog. Oceangr. 228, 103321 (2024).

Inoue, M., Hanaki, S., Kameyama, H., Kumamoto, Y. & Nagao, S. Unique current connecting Southern and Indian Oceans identified from radium distributions. Sci. Rep. 12, 1781 (2022).

Kumamoto, Y. et al. Fukushima-derived radiocesium in the western subarctic area of the North Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea, and Arctic Ocean in 2019 and 2020. J. Environ. Radioact. 251–252, 106949 (2022).

Inoue, M. et al. Spatial variations of 226Ra, 228Ra, 137Cs, and 228Th activities in the southwestern Okhotsk Sea. J. Environ. Radioact. 104, 75–80 (2012).

Xu, B. et al. Radium-226 in the global ocean as a tracer of thermohaline circulation: Synthesizing half a century of observations. Earth-Sci. Rev. 226, 103956 (2022).

Moore, W. S. et al. Enriched regions of 228Ra along the U.S. GEOTRACES Pacific meridional transect (GP15). J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 129, e2023JC020564 (2024).

Inoue, M. Surface distributions of 228Ra in seas and oceans globally: Implications for water circulation and contaminant transport. J. Environ. Radioact. 278, 107468 (2024).

Stabeno, P. J. et al. Long-term observations of Alaska coastal current in the northern Gulf of Alaska. Deep Sea Res. II 132, 24–40 (2016).

Kuroda, H., Suyama, S., Miyamoto, H., Setou, T. & Nakanowatari, T. Interdecadal variability of the Western Subarctic Gyre in the North Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. I 169, 103461 (2021).

Danielson, S. L. et al. Coupled wind-forced controls of the Bering-Chukchi shelf circulation and the Bering Strait throughflow: Ekman transport, continental shelf waves, and variations of the Pacific-Arctic sea surface height gradient. Prog. Oceanogr. 125, 40–61 (2014).

Ezer, T. & Oey, L.-Y. On the dynamics of strait flows: An ocean model study of the Aleutian passages and the Bering Strait. Ocean Dyn. 63, 243–263 (2013).

Inoue, M. et al. Distributions of radiocesium and radium isotopes in the western Bering Sea in 2018. Mar. Chem. 225, 103843 (2020).

Nozaki, Y., Kasemsupaya, V. & Tsubota, H. The distribution of 228Ra and 226Ra in the surface waters of the northern North Pacific. Geochem. J. 24, 1–6 (1990).

Li, Q. et al. Transit time of river water in the Bering and Chukchi Seas estimated from δ18O and radium isotopes. Prog. Oceanogr. 159, 115–129 (2017).

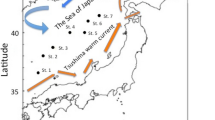

Inoue, M., Tanaka, K., Kofuji, H., Nakano, Y. & Yamamoto, M. Seasonal variation in the 228Ra/226Ra ratio of coastal water within the Sea of Japan: Implications for the origin and circulation patterns of the Tsushima Coastal Branch Current. Mar. Chem. 107, 559–568 (2007).

Inoue, M. et al. Lateral variations of 134Cs and 228Ra concentrations in surface waters in the western North Pacific and its marginal sea (2018–2019): Implications for basin-scale and local current circulations. Prog. Oceanogr. 195, 102587 (2021).

Inomata, Y. & Aoyama, M. Evaluating the transport of surface seawater from 1956 to 2021 using 137Cs deposited in the global ocean as a chemical tracer. ESSD. 10.5194/essd-2022-374 (2022).

Povinec, P. P. et al. 90Sr, 137Cs and 239+240Pu concentration surface water time series in the Pacific and Indian Oceans—WOMARS results. J. Environ. Radioact. 81, 63–87 (2005).

Macdonald, A. M. et al. A Fukushima tracer perspective on four years of North Pacific mode water evolution. Deep-Sea Res. I 166, 103379 (2020).

Kumamoto, Y. et al. Zonal and vertical transports of Fukushima-derived radiocesium in the subarctic gyre of the North Pacific until 2014. J. Environ. Radioact. 247, 106864 (2022).

Smith, J. N. et al. Recent transport history of radioactivity in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Environ. Sci. Tech. 51, 10494–10502 (2017).

Takata, H., Kusakabe, M., Inatomi, N. & Ikenoue, T. Appearances of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant-derived 137Cs in coastal waters around Japan: results from marine monitoring off nuclear power plants and facilities1983-2016. Environ. Sci. Tech. 52, 2629–2637 (2018).

Kipp, L. E., Henderson, P. B., Wang, Z. A. & Charette, M. A. Deltaic and estuarine controls on Mackenzie River solute fluxes to the Arctic Ocean. Estuaries Coasts 43, 1992–2014 (2020).

Huang, D., Lin, J., Du, J. & Yu, T. The detection of Fukushima-derived radiocesium in the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean six years after the nuclear accident. Environ. Pull. 256, 113386 (2020).

Inoue, M. et al. Subarctic-scale transport of 134Cs to ocean surface off northeastern Japan in 2020. Sci. Rep. 13, 7524 (2023).

Inoue, M. et al. Temporal and spatial variations of 134Cs and 137Cs levels in the Sea of Japan and Pacific coastal region: Implications for dispersion of FDNPP-derived radiocesium. J. Environ. Radioact. 182, 142–150 (2018).

Ladd, C., Hunt, G. L. Jr., Mordy, C. W., Salo, S. A. & Stabeno, P. J. Marine environment of the eastern and central Aleutian Islands. Fish. Oceanogr. 14, 22–38 (2005).

Stabeno, P. J., Danielson, S. L., Kachel, D. G., Kachel, N. B. & Mordy, C. W. Currents and transport on the Eastern Bering Sea shelf: an investigation of over 20 years of data. Deep Sea Res. II 134, 13–29 (2016).

Kumamoto, K., Aoyama, M., Hamajima, Y. & Murata, A. Activity concentration of Fukushima-derived radiocesium in the western subarctic area of the North Pacific Ocean in summer 2017. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 325, 263–270 (2020).

Inoue, M. et al. Spatial variations of low levels of 134Cs and 137Cs in seawaters within the Sea of Japan after the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 81, 340–343 (2013).

Nakano, Y., Inoue, M. & Komura, K. A simple coprecipitation method combined with low-background γ-spectrometry: Determination of 7Be, 137Cs, 210Pb, and radium and thorium isotopes in small-volume coastal water samples. J. Oceanogr. 64, 713–717 (2008).

Hamajima, Y. & Komura, K. Background components of Ge detectors in Ogoya underground laboratory. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 61, 179–183 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the researchers, captain, and crew onboard of the R/Vs Mirai, Oshoro Maru, and Hakuho Maru for their assistance during sampling. This research was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (21H03575 to MI) and (#24110004 to YK). This study was also supported by the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability II (ArCS II) Project (JPMXD1420318865) and the cooperative research program of Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University (No. 23001) to YK. The maps in the figures were drawn using Ocean Data View ver. 5.5.1 (http://odv.awi.de).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.I. designed the study and prepared the manuscript. H.M., D.K., and Y.H. performed the radium and radiocesium analyses. Y.K. and D.N. conducted seawater sampling. S.N. and Y.K. supervised the study. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inoue, M., Mitsunushi, H., Koshiishi, D. et al. Retention of 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP accident-derived 137Cs in the northern North Pacific–Bering Sea. Sci Rep 15, 36444 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20520-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20520-w