Abstract

The stability of foundation piles in the secondary terrace of the Wei River is of great significance for engineering construction in northwestern China. To investigate the bearing behavior of piles and the shear characteristics of the pile–soil interface, three cast-in-place piles were constructed at a representative site, with reinforcement stress meters installed in two of them. Static vertical compression tests were performed using a sparse-to-dense loading strategy, and comparative interface shear tests were carried out under controlled laboratory conditions. The results show that the pile side friction resistance accounts for the majority of the bearing capacity, while the contribution of end resistance is limited. The shear stress–displacement curves of the pile–soil interface can be classified into three types—strain-hardening, strain-softening, and ideal elastic–plastic—depending on soil properties and stress levels. These findings provide a clear classification of the support–deformation relationship and reveal the mechanisms governing load transfer in the secondary terrace deposits. The outcomes offer practical guidance for the design and optimization of pile foundations in alluvial terrace areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As part of Xi’an’s strategic expansion, extensive urban and industrial development is envisaged along the northern bank of the Wei River. This transformation has intensified the demand for robust infrastructure foundations within the region’s intricate soft soil strata, particularly on the second river terrace, where the performance of pile foundations under static loading assumes paramount importance.

The region north of the Weihe River is defined by highly intricate hydrogeological conditions. The upper strata are dominated by aeolian loess interbedded with residual paleosols, while the middle and lower layers comprise alluvial sands and silty clays deposited by the river itself. Collectively, these deposits exhibit high degrees of saturation and weak bearing capacity, with certain zones even presenting the traits of a soft, silty foundation. To satisfy the structural load-bearing requirements of construction projects under such challenging conditions, in-situ concrete piles have been widely adopted. Their prevalence stems from mature construction methodologies, broad adaptability, cost efficiency, and the capacity to provide substantial bearing resistance1,2,3,4,5.

Significant research achievements have been made in understanding the engineering characteristics of soft foundations6,7,8, as well as in identifying common construction issues and corresponding mitigation measures for cast-in-place piles in such strata9,10,11,12,13, many of which have been successfully applied in engineering practice. However, owing to regional variations in sedimentary facies, provenance, stratigraphic sequences, and fault structures during the genesis of these soft soils, their engineering behavior demonstrates marked heterogeneity. Consequently, geotechnical engineers engaged in site investigation, design, construction, or inspection find their technical methodologies and conceptual frameworks inevitably shaped and constrained by such geological distinctions.

Among the diverse methods employed to investigate the bearing behavior of pile foundations, the most prevalent is the examination of the relationship between bearing capacity and settlement deformation, as revealed through static vertical compression tests conducted on single piles14,15,16,17. However, this macroscopic relationship often proves insufficient in explaining the complex anomalies observed in pile bearing behavior. At present, a widely adopted approach involves embedding sensors within the pile body and combining them with static vertical compression tests, thereby enabling a more precise analysis of internal force distribution along the pile18,19,20,21. Comparative analyses between pile design parameters and post-construction testing on the second terrace of the Wei River reveal that bearing behavior frequently diverges markedly from design expectations, differing not only from that of typical soft surficial soils but also from the response of soils between piles. This divergence highlights the paramount importance of investigating the mechanical behavior of the pile–soil interface throughout the process of settlement-induced deformation.

Therefore, this study seeks to examine the vertical compressive bearing behavior of cast-in-place single piles situated on the second terrace of the Wei River. By integrating static load testing with axial force monitoring and shear interface simulations, the mechanisms governing the mobilization of shaft resistance are elucidated. In addition, the relationship between field test results and laboratory shear behavior is explored through the combined application of scanning electron microscopy and information entropy theory, offering insights into the shear deformation process at the pile–soil interface. The findings provide a valuable reference for foundation design in pile-supported structures constructed within high-saturation soft soil environments.

Methodology

Test pile design

The test was conducted on the second terrace of the northern bank of the Weihe River, approximately 3.5 km south of the river. The terrain is flat and expansive, with ground elevations ranging between 351.00 and 353.00 m. Figure 1 presents the plan layout of the pile locations and boreholes. The three test piles are labeled S1, S2, and S3; piles M1 through M8 serve as eight auxiliary reaction anchor piles, and ZK1 and ZK2 are boreholes designated for stratigraphic verification. Table 1 summarizes the physical and mechanical characteristics of the foundation soil. Figure 2 illustrates the lithological description and distribution characteristics obtained from the verification boreholes at the test site. Table 2 lists the design parameters for the test piles and anchor piles. Based on the verification borehole data, test piles S1 and S2 were selected for the installation of pile body sensors. Each test pile is symmetrically equipped with 11 pairs of measurement points along the pile shaft, as shown in Fig. 3. The internal force of the pile shaft was measured using Ф18 vibrating wire strain gauges, as presented in Fig. 4. Three single-pile vertical compression static load tests were conducted, with internal force measurements performed on two piles. The site’s collapsible soil layer is only 1.5 m thick, and the calculated collapsibility is relatively minor. Therefore, the collapsibility of the loess-like soil is not considered.

Methodology for static vertical compression testing of a single pile

The static vertical compression test system for single piles primarily comprises three components: the loading system, the reaction frame, and the measurement system, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The loading is applied using two 6300 kN hydraulic jacks operating in parallel, controlled by an electric hydraulic pump. The reaction device consists of four anchor piles combined with a beam structure. Load measurement is conducted via a hydraulic pressure sensor ranging from 0 to 70 MPa, while settlement is measured using displacement sensors with a resolution of 0.01 mm. Data acquisition is automatically performed by the RSM-JCⅢ static load testing instrument. According to the specifications22, the test employs a slow-maintenance loading method: each load level is applied until relative stability is achieved before proceeding to the next, continuing until pile failure occurs, followed by staged unloading back to zero.

Settlement was recorded at 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after each load increment, and subsequently at 30-min intervals. Unloading was conducted in increments twice the magnitude of the loading increment values. After each unloading stage, residual settlement was measured once at 15 min, twice more at 15-min intervals, and then once again after 30 min, after which the next unloading stage was initiated. Upon complete unloading to zero, residual settlement at the pile head was monitored for 3 h, with readings taken at 15 and 30 min, and then at 30-min intervals thereafter.

The use of excessively sparse load increments in static load tests can lead to data gaps and an inability to trace failure causes, while increasing the risk of structural instability. Conversely, overly dense increments prolong the testing period and may cause resource wastage due to excessive pursuit of high-density grading. Adhering to the four principles of scientific rigor, feasibility, economy, and safety, the current static load test did not employ uniform increments. Instead, a “coarse-to-fine” loading scheme was adopted, with load increments of 1000 kN, 800 kN, and 600 kN applied to test piles S1, S2, and S3, respectively. Detailed loading increments are presented in Table 3.

Pile shaft internal force measurement method

When subjected to external loads, variations in strain within the sensing structure alter the gauge length between the two support points of the vibrating wire, thereby inducing a shift in its natural frequency. Under conditions of small oscillations, the natural frequency f of the vibrating wire is related to the axial stress, as expressed in Eq. (1). When the sensor is exposed to pressure, the natural frequency changes correspondingly, with the linear relationship between frequency and force described in Eq. (2). The axial force within the pile shaft and the lateral friction resistance mobilized in each soil layer are subsequently determined using Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.

where, f represents the natural frequency of the vibrating wire, s is the force applied to the wire, and L is the effective length of the wire, r denotes the mass density of the wire material.

where, Pi is the pressure measured at the i instance on the rebar, f0 is the initial frequency, fi is the measured frequency, b is the intercept, and k is the coefficient.

where E denotes the elastic modulus of concrete, Eg represents the elastic modulus of the reinforcement, Ag denotes the cross-sectional area of the reinforcemen

where D denotes the diameter of the pile, qs denotes the side friction resistance of the soil layer segment Hi, and Ni is the axial load in the pile shaft.

After the installation of the rebar strain gauges, measurements were taken 3–4 times prior to the commencement of the vertical static compressive force test to facilitate data correction. One measurement was conducted immediately before the formal loading as the initial frequency value. One measurement was taken at each load level after the settlement had stabilized during the test, continuing until the loading and unloading processes were completed.

Shear test scheme for the pile-ground interface

To explore the mobilization mechanism of side friction along the pile, undisturbed soil samples were extracted from a depth of 1.5 m near the pile head and subsequently subjected to laboratory shear tests at the pile–ground interface. The samples were air-dried, remolded, and prepared with saturation levels of 50%, 67%, and 80%, then placed in 150 mm × 150 mm shear boxes. The load was removed after normal consolidation pressure was applied and the vertical deformation remained below 0.005 mm within 15 min. The target load was directly reapplied following a 20-min rest period. Once the vertical deformation again remained under 0.005 mm for 15 min, the remolded soil cakes-approximately 10 mm thick-were deemed ready. The pile surface morphology was simulated using wooden boards with a 1 mm undulating profile. Shear tests were conducted under normal stresses of 15, 30, and 45 kPa using displacement control. Shear test system as shown in Fig. 6. Subsequently, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to analyze the microstructural features of the pile–soil interface samples obtained from the field (post-static load testing) and the remolded laboratory specimens (post-shear testing). All SEM images were captured at × 500 magnification and binarized using a fixed global threshold. Particle major axes were determined through ellipse fitting, and only particles with aspect ratios above 1.2 and diameters larger than 10 μm were considered valid. A schematic diagram of the particle major axis is shown in Fig. 7. Orientation data were extracted from no fewer than 200 particles per image to ensure statistical robustness. Software tools were used to statistically evaluate the orientation of particle major axes after acquiring microstructural imagery, and information entropy theory was applied to assess the directional distribution of the microscopic particle structure.

The range of possible orientations for the particle major axis [0,π] is evenly divided into 9 intervals. Assuming the number of particles whose major axis direction falls within the i interval is Ki, and the corresponding probability is Pi(Ki), where the particle orientations are mutually exclusive events satisfying the condition:

The orientation entropy E of the mineral particles can be expressed as:

where, E is a continuous function of Pi(Ki), when all Pi are equal, E becomes a monotonically increasing function of n, and it satisfies the composition rule. Moreover, E = 0 if and only if any one of the Pi(Ki)(i = 1, 2, …, n) equals 1, while under all other conditions, E remains positive. The entropy reaches its maximum when the events are equiprobable. It is clear that structural orientation entropy serves as a statistical metric, with its values ranging between 0 and 1. A lower entropy value indicates a higher degree of structural orientation, indicating lower disorder. Conversely, a larger entropy implies a lower degree of orientation and greater structural disorder.

The orientation entropy E employed in this study is derived from Shannon’s concept of information entropy. A lower value of E signifies a greater degree of alignment—or reduced randomness—in the orientation of the soil particles’ major axes. This parameter serves as a quantitative indicator of the structural order within the microstructure during shear deformation. In geotechnical applications, it reflects the extent of coordinated particle motion within shear bands, thereby providing a means of distinguishing among elastic, elasto-plastic, and plastic deformation phases in the pile–soil interface zone.

Machine-rock interaction and rock-breaking models

Static vertical compression test on a single pile

Bearing capacity analysis

Figures 8, 9 and 10 present the Q-s and s-lgt curves obtained from the static vertical compression tests conducted on single piles S1, S2, and S3. For test pile S1, the load increased from 0 to 3000 kN, during which the Q-s curve remained approximately linear. When maintaining a load of 3000 kN and reaching the stability criterion, the settlement was 4.15 mm, with a mean settlement rate of approximately 0.0014 mm/kN, indicating a relatively slow deformation. The curve exhibited a gentle downward bending shape from 3000 to 5000 kN. When maintaining 5000 kN and reaching stability, the settlement reached 19.03 mm, increasing by 14.88 mm compared to 3000 kN, with a mean settlement rate of approximately 0.0074 mm/kN, showing an obvious acceleration in settlement. The settlement increased sharply as the load rose from 5000 to 6000 kN. Stability could not be achieved under a maintained load of 6000 kN. The test was terminated with a final settlement of 85.50 mm and an average settlement rate exceeding 0.0666 mm/kN, indicating a sudden and significant increase in settlement. After unloading from 6000 to 0 kN, the settlement rebounded by 7.14 mm, stabilizing at 78.36 mm.

For test pile S2, the load increased from 0 to 3200 kN, with the Q-s curve remaining approximately linear. Under a maintained load of 3200 kN and reaching stability, the settlement was 4.55 mm, with a mean settlement of 0.0014 mm/kN, indicating slow deformation. The curve gently bent downward from 3200 to 4800 kN. The settlement was 15.71 mm when maintaining 4800 kN and reaching stability, an increase of 11.16 mm compared to 3200 kN, with an average settlement rate of 0.0070 mm/kN, showing clear acceleration. The curve deviated from gentle bending and initially dropped sharply between 4800 and 5600 kN. Although stability was reached under 5600 kN load, it was difficult and required a longer time, the final settlement was 39.40 mm, an increase of 34.85 mm from 3200 kN, with an average settlement rate of 0.0296 mm/kN, showing further acceleration. The curve dropped again sharply from 5600 to 6400 kN. Stability could not be maintained at 6400 kN, so the test was terminated. The final settlement reached 83.42 mm, with an average settlement rate above 0.0550 mm/kN, indicating a sudden surge in settlement. The rebounded after unloading by 7.68 mm and stabilized at 75.74 mm after unloading from 6400 to 0 kN.

For test pile S3, the load increased from 0 to 3000 kN, during which the Q-s curve was approximately linear. When maintaining a load of 3000 kN and reaching the stability criterion, the settlement was 4.17 mm, with an average settlement rate of 0.0014 mm/kN, indicating a relatively slow deformation. The curve exhibited a gentle downward bend from 3000 to 4800 kN. When maintaining 4800 kN and reaching stability, the settlement reached 17.45 mm, increasing by 11.89 mm compared to 3000 kN, with an average settlement rate of 0.0074 mm/kN, showing a clear acceleration in settlement. The curve deviated from the gentle bend and dropped sharply for the first time between 4800 and 5400 kN. Although stability was reached at 5400 kN, it was difficult to maintain and required a prolonged stabilization time. The final settlement was 34.08 mm, an increase of 28.49 mm from 3000 kN, with an average settlement rate of 0.0277 mm/kN, indicating continued acceleration. The curve dropped again sharply from 5400 to 6000 kN. Stability could not be maintained at 6000 kN. The test was terminated with a final settlement of 80.19 mm and an average settlement rate exceeding 0.0769 mm/kN, reflecting a sudden and dramatic increase in settlement. After unloading from 6000 to 0 kN, the pile top rebounded after unloading by 7.35 mm, stabilizing at 72.84 mm.

The s-lgt curves all exhibited sudden settlement drops Sd as illustrated in Fig. 11 during the loading process of the three test piles. When the loading increments were relatively sparse, the sudden drop occurred at the load level where the settlement deformation failed to meet the stability criterion. For example, for test pile S1 at a load of 6000 kN, after 30 min of loading, the settlement rate increased sharply and stability could not be achieved, ultimately leading to failure. This abrupt drop point signifies that both the side resistance and end bearing capacity of the pile have reached their ultimate limit state. As shown in Fig. 11, the reaction force of the roof support exhibits a more rapid increase compared with the floor support. This phenomenon can be explained by the stress concentration near the roof, where the vertical stress dominates and induces bending and splitting failures. In contrast, the floor mainly undergoes shear and uplift, leading to a slower force response. Quantitatively, at a deformation of 15 mm, the roof support reaction is approximately 28% higher than that of the floor, reflecting the different load transfer mechanisms of the roof–floor system.

The sudden settlement drop occurred at a load level that barely met or failed to meet the stability criterion when the loading increments were relatively dense. For example, in test pile S2, at a load of 5600 kN, after 240 min of loading, the settlement rate increased sharply, then after 780 min, the rate gradually stabilized, meeting the stability standard. The settlement rate immediately rose to the sharp rate observed at 5600 kN upon loading to 6400 kN, failing to achieve stability and eventually leading to failure. This abrupt drop suggests that the pile’s side and end resistances either simultaneously reached the yield state or that one entered the yield state while the other attained the ultimate limit state, signaling that the pile-soil system was approaching failure. When test pile S3 was loaded to 5400 kN and the loading duration lasted for 150 min, the settlement rate sharply increased, though the rate of increase was less than that of test pile S2., the settlement rate stabilized, meeting the stability criterion after 420 min. When the load reached 6000 kN and the loading duration lasted 90 min, the settlement rate sharply increased, with a rate faster than that at 5400 kN, failing to meet the stability criterion and leading to instability. The initial abrupt drop suggests that both the pile side resistance and end resistance reached the yield state simultaneously, or that one entered the yield state while the other reached the ultimate limit state, causing the pile-soil system to approach failure. The second sudden drop signifies that both resistances reached the ultimate state, and the system failed. Evidently, the loading increments for test pile S1 were too sparse, causing significant deviations between the ultimate state in the static load test and the actual condition. In contrast, the increments for S2 and S3 were more appropriate, yielding more accurate ultimate state information.

By the end of the test, the total settlement surpassed 40 mm, exceeding five times the settlement observed at the preceding load level. In accordance with the Technical Code for Testing of Building Foundation Piles (JGJ106-2014), the ultimate vertical compressive bearing capacities of test piles S1, S2, and S3 are determined to be 5000 kN, 5600 kN, and 5400 kN, with corresponding settlements of 19.03 mm, 39.40 mm, and 34.08 mm, respectively. From the perspectives of deformation control and structural safety, it is noted that although piles S2 and S3 met the stability criterion at 5600 kN and 5400 kN respectively, the time required to achieve stability was considerable, and the stability was marginal. Moreover, their critical displacements were significantly larger than that of S1. When the subsequent load level was applied, the piles failed to stabilize and ultimately reached an unstable state. Therefore, it is more reasonable and reliable to adopt the load level immediately prior to the onset of instability as the ultimate vertical compressive bearing capacity. Accordingly, the ultimate bearing capacities for piles S1, S2, and S3 are taken as 5000 kN, 4800 kN, and 4800 kN, respectively, with corresponding settlements of 19.03 mm, 15.71 mm, and 17.45 mm. The differences between the two sets of ultimate bearing capacities (Table 4) are substantial. Designers may select a scientifically grounded, reasonable, and economically viable ultimate bearing state based on the structural grade of the superstructure and its sensitivity to settlement.

Deformation analysis

According to the pile compression Eq. (7) in the Technical Code for Building Pile Foundations (JGJ 94–2008), the calculated pile compression corresponding to each load level is summarized in Table 5. Based on these values, the pile compression-pile head settlement curves are plotted in Fig. 12.

where, ξ denotes the comprehensive coefficient, which is taken as 0.5 for bored cast-in-place piles, Pt is the load at the pile head, L denoted the length of pile; Ep is the pile’s elastic modulus, and Ap represents the pile’ s cross-sectional area.

During the static loading tests, ring-shaped cracks appeared at the pile-ground interface near the embedded sections of test piles S1, S2, and S3 after applying loads of 5000 kN, 5600 kN, and 5400 kN, respectively, with crack widths of approximately 1 mm. The cracks around the piles became more pronounced after unloading, widening to about 2–3 mm. In the later stages of loading, excessive settlement of the pile body led to incompatible deformation between the surrounding soil and the pile. The pile experienced axial compression and radial expansion during loading. The pile rebounded axially and recovered its radial deformation upon unloading, whereas the surrounding soil exhibited weak elastic recovery or even plastic deformation, resulting in more prominent cracks around the pile post-unloading.

The rebound at the pile tops of S1, S2, and S3 was 7.14 mm, 7.68 mm, and 7.35 mm after unloading. The corresponding pile body compression deformations were 6.80 mm, 6.84 mm, and 6.80 mm-values closely matching the rebound, indicating that the deformation of the pile concrete during testing was predominantly elastic. When pile settlement was primarily governed by axial compressive deformation of the pile body, the resulting settlement ranged from 8 to 12 mm, as shown in Fig. 12. Based on a Poisson’s ratio of 0.2 for concrete, the corresponding circumferential deformation at the embedded section of the pile was estimated to be 1.6 mm to 2.4 mm, which closely aligns with the observed crack widths.

The settlement profiles of test piles S1, S2, and S3 under loading exhibit similar shapes. The deformation process can be categorized into four distinct stages, as illustrated in Fig. 13.

Elastic stage (segment OA)

At the initial stage of loading, the applied load is relatively low and the corresponding displacement is primarily caused by recoverable axial compression of the pile, which accounts for approximately 80% of the total vertical deformation of the pile–soil system. The pile head settlement curve lies slightly above but remains close to the pile compression curve, both exhibiting a linear relationship. A quantitative criterion for identifying this stage is that no inflection point appears. This stage can be used for pile integrity testing and stiffness verification, ensuring that the pile meets design expectations before higher load levels are applied.

Yield stage (segment AB)

The instability stage is characterized by a rapid increase in settlement or significant slippage of the pile body, signifying loss of load-bearing capacity. The curve shows a sudden drop, with axial compression of the pile contributing less than 15% of total settlement. Instability can be defined by a settlement rate greater than 2 mm per 100 kN load increment or by the appearance of a peak point followed by a drop exceeding 10%. This stage provides a basis for defining the ultimate bearing capacity and the limit state of pile foundations. It serves as a direct reference for design modifications, such as increasing pile dimensions or adjusting foundation treatment methods.

The yield stage begins when deformation shifts from pile axial compression to shear at the pile–soil interface. At this point, pile compression decreases to about 50% of total settlement, and the pile head curve diverges from the pile compression curve. The pile compression contribution drops below 50% and the slope of the load–settlement curve decreases by more than 20% compared to the elastic stage. This stage is critical for assessing safety reserves and guiding construction control. Identifying the onset of yielding allows engineers to determine whether additional reinforcement or reduced loading rates are necessary to prevent premature instability.

Instability stage (segment BC)

The instability stage is characterized by a rapid increase in settlement or significant slippage of the pile body, signifying loss of load-bearing capacity. The curve shows a sudden drop, with axial compression of the pile contributing less than 15% of total settlement. Instability can be defined by a settlement rate greater than 2 mm per 100 kN load increment or by the appearance of a peak point followed by a drop exceeding 10%. This stage provides a basis for defining the ultimate bearing capacity and the limit state of pile foundations. It serves as a direct reference for design modifications, such as increasing pile dimensions or adjusting foundation treatment methods.

Unloading rebound stage (segment CD)

Following failure, unloading reveals both elastic recovery of the pile and residual plastic deformation of the surrounding soil. The rebound displacement typically recovers more than 85% of the measured pile compression. In the tests, piles S1–S3 showed rebounds nearly identical to the corresponding elastic compression of the pile body, confirming the predominance of elastic recovery, although residual settlements remained. This stage is valuable for long-term performance evaluation of pile–soil systems. The comparison between rebound and elastic compression can be used to assess whether the pile mainly works in an elastic state or if significant plastic soil deformation may affect serviceability.

Axial force of the pile shaft

Figure 14 illustrates the axial force distribution along the pile shaft for test piles S1 and S2 under various load levels. All curves exhibit an overall inverted trapezoidal shape. The axial force distribution along the length of each pile shows a similar trend under different loads, gradually decreasing with depth. When the applied load was less than 4000 kN, the axial force in test pile S1 had not yet been transmitted to the pile tip, and therefore no compression deformation occurred at the pile base. When the applied load exceeded 4000 kN, the load at the pile head was progressively transferred to the pile tip. At an applied load of 3200 kN, the axial force in pile S2 had not yet been transmitted to the pile tip. Upon reaching 4000 kN, the axial force was transferred to the pile base, albeit small, with correspondingly minor compression deformation at the pile base. The load at the pile head began to gradually transfer to the pile tip only after the applied load exceeded 4800 kN.

Additionally, when the applied load at the pile head is relatively low, the axial force within the pile is transmitted through the surrounding soil layers in an approximately linear fashion. However, the axial force transmission increasingly exhibits nonlinear behavior at higher load levels. The axial force distribution curves for pile S1 at load levels of 2000 kN and 3000 kN display a good linear relationship, slight concavity appears at 4000 kN and 5000 kN, and the nonlinearity becomes pronounced at 6000 kN.

Similarly, linearity is well maintained for pile S2 at 1600 kN, 2400 kN, and 3200 kN, slight concavity emerges at 4000 kN and 4800 kN, and distinct nonlinearity is evident at 5600 kN and 6400 kN. The underlying reason is primarily attributed to the high saturation of the entire soil stratum, which results in a relatively loose connection between soil particles surrounding the pile. The adsorption forces and capillary forces on particle surfaces are weakened, causing a reduction in cohesion. Meanwhile, the high saturation lowers the effective stress within the soil, further degrading the frictional interaction at the pile-soil interface. This leads to a small compression deformation gradient between the upper and lower parts of the pile and a more uniform attenuation of axial force during transmission. However, as the load continues to increase and relative displacement in the pile-soil system enlarges, the compression deformation of the soil at the pile tip sequentially undergoes elastic deformation, elastoplastic deformation, and eventually progresses to plastic deformation. Throughout this process, the resistance at the pile tip exerts a notably nonlinear influence on the transmission of axial force along the pile.

Pile side resistance

Figure 15 illustrates the distribution curves of side frictional resistance along the pile length for test piles S1 and S2. Table 6 presents the results of side friction resistance and end bearing resistance. It is evident that this pile type functions as a friction pile From Fig. 15 and Table 6. At loading levels of 2000 kN and 3000 kN for test pile S1, the primary side friction resistance was provided by the 0–23.5 m soil stratum, while the 23.5–27.5 m layer had just begun to mobilize its resistance and contributed minimally. The side friction mobilization across the 0–27.5 m depth increased significantly at 4000 kN, and the 27.5–31.0 m layer also began to participate in bearing the load. When the load reached 5000 kN, the 0–34.0 m segment exhibited substantial side friction mobilization, while the 34.0 m-36.0 m layer had mobilized approximately 80% of its capacity-sufficient to balance the pile head load. Pile instability and failure occurred at 6000 kN, with the side friction resistance along the entire pile length fully mobilized, marking the attainment of the ultimate limit state. Figure 15 illustrates the time-dependent evolution of the support force, in which the roof support reaches a peak more quickly than the floor support. This is due to the earlier activation of tensile cracks in the roof, while the floor response is governed by shear deformation and delayed failure initiation. Quantitative comparison shows that the peak force of the roof support occurs about 12% earlier than that of the floor, highlighting the strong influence of failure mode on the support–deformation relationship.

At a loading value of 1600 kN for test pile S2, side friction resistance was primarily provided by the 0–19.5 m soil layer, while the 23.5–27.5 m layer had only just begun to mobilize and contributed minimally. At 2400 kN, the mobilization of side friction in the 0–27.5 m segment increased markedly. When the load reached 3200 kN, side friction in the 0–27.5 m section continued to increase, and the 27.5–31.0 m layer was activated, beginning to share the pile head load. Although the 34.0–36.0 m layer exhibited limited side friction mobilization at 4000 kN, all strata along the pile length began to contribute. Side friction increased rapidly across all layers at 4800 kN, with particularly notable growth from 19.5 to 36.0 m. The 0–34.0 m strata demonstrated substantial mobilization at 5600 kN, while the 34.0–36.0 m layer, though not as fully mobilized as the overlying layers, still reached a relatively high level. The pile experienced instability and failure at 6400 kN, with side friction along the full length of the pile fully mobilized, signifying the ultimate limit state.

By synthesizing the axial force distribution along the pile (Fig. 14) with the distribution of side friction resistance (Fig. 15), the depth-dependent variation of side friction resistance can be delineated into three distinct stages, as illustrated in Fig. 16. In the first stage, under relatively low pile head loads, the side friction resistance within the soil strata exhibits a parabolic profile with depth—increasing gradually at shallow depths before decreasing rapidly with further penetration. At this stage, the bearing capacity is predominantly derived from the side resistance mobilized within the upper two-thirds of the pile shaft, while the end bearing resistance remains largely inactive. In the second stage, as pile head loads increase, the zone of pile shaft compression extends downward, transmitting axial forces to the pile tip. The mobilization of side resistance in the lower portion of the pile shaft becomes pronounced, eventually reaching levels comparable to the upper portion. Although the distribution within the upper strata retains the same general form as in the first stage, its magnitude increases, while the resistance in the lower strata develops along a similar curvature but displays a distinctly different pattern. By this stage, side resistance is mobilized across all soil layers, and the lower third of the shaft contributes a bearing capacity nearly equivalent to that of the upper two-thirds. In the third stage, as pile head loads continue to increase, the settlement rate accelerates, ultimately driving the system toward instability. The growth of side friction resistance in the upper two-thirds of the shaft gradually diminishes, while a sharp and concentrated increase occurs in the lower third, making it the principal source of the overall bearing capacity.

To analyze the development characteristics of side friction resistance at varying depths and time intervals, side friction resistance curves of test piles S1 and S2 under different loading conditions were plotted, as shown in Fig. 17. The time-dependent development characteristics of side friction resistance and the curves of side friction resistance versus relative displacement are presented in Fig. 18.

The 0–23.5 m soil stratum consists of loess-like silty clay, characterized by relatively low compressive modulus and cohesion. In terms of pile length, this layer provides surplus resistance under low pile head loads. The side friction resistance gradually increases from top to bottom. The curves exhibit a downward bending trend in the later stages of loading, indicating that the layer retains reserve capacity to balance the applied load. In the first third of the loading process, resistance increases synchronously. In the remaining two-thirds, the growth decelerates, with a slight rise near the ultimate state. Side friction resistance initially increases rapidly and exhibits a linear relationship with the relative displacement between the pile and the surrounding soil. As displacement increases and the pile-soil system begins to yield, all soil layers display a decelerated growth in side resistance. With further increases in relative displacement, strain-softening behavior emerges, and the side friction resistance in each layer sequentially reaches its ultimate state from top to bottom.

The 23.5 m–31.0 m stratum is composed of silty sand, distinguished by a markedly higher compression modulus and internal friction angle. Relative to the pile length, this layer furnishes substantial resistance under moderate pile-head loads. From the onset of loading, side friction in this horizon responds promptly to pile-top stresses, producing nearly linear load–response curves that signify a well-balanced stress transfer. Temporally, the patterns of increase and subsequent deceleration of side resistance in the silty sand layer resemble those in the overlying 0–23.5 m loess-like silty clay, although the propensity for rapid escalation near the ultimate state is more pronounced. In terms of relative displacement, a more distinct linear relationship emerges between side friction and pile–soil displacement in the early stages of loading, attributable to the rigid interlocking of sand particles. Progressive settlement further mobilizes side friction, reinforcing the skeletal framework at the interface and enhancing both modulus and friction angle. As settlement advances, intensified friction induces particle abrasion, fragmentation, rearrangement, and densification, leading to the formation of a new structural skeleton. This reconfiguration is accompanied by significant elastoplastic deformation. The curve morphology in Fig. 19a reveals the occurrence of dilation, which narrows the borehole and drives the pile–soil system into a post-yield hardening regime. This mechanical evolution allows the silty sand layer to retain latent strength reserves, thereby sustaining side resistance until global failure or accelerated settlement ultimately ensues.

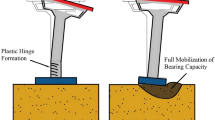

The 31.0 m-37.0 m soil layer consists of silty clay, with compression modulus and friction angle slightly lower than those of the silty sand layer. Within this pile length range, compression and shear deformations occur in the soil beneath the pile tip, forming a compression zone and an arching zone 23,24,25,26,27, as shown in Fig. 19. The arching effect, coupled with the confinement imposed by the overlying soil, modifies the lateral earth pressure coefficient, resulting in elevated horizontal stress near the pile tip and an enhancement in side friction resistance. Temporally, although the side friction resistance develops later, it increases rapidly. Once the average side friction strength of the overlying soil is reached, the curve begins to exhibit a downward trend. In the later stages of the test, a sharp yet short-lived increase in side friction resistance is observed with the continued progression of loading and settlement. In terms of relative displacement, the curve shows obvious strain hardening. Following yielding, plastic deformation intensifies, leading to improvements in the soil’s compressive strength, shear strength, and stiffness. The soil’s resistance to deformation progressively strengthens, and deformation magnitude decreases with continued loading. Although side friction resistance contributes 88% and end bearing resistance 12% to the total pile capacity in this static load test, the reinforcing influence of end bearing resistance on the side friction resistance in the lower portion of the pile should not be underestimated.

Considering the characteristics of side friction resistance along the pile shaft, the length of pile in this region is divided into three segments: HⅠ—the normal side friction resistance segment (0–23.5 m), HⅡ—the side friction reserve segment (23.5–31.0 m), and HⅢ—the pile end reinforcement segment (31.0–37.0 m). These three stages are illustrated in Fig. 20.

Based on a comprehensive analysis of the on-site static load test results, the side resistance at different depths exhibits layered and asynchronous activation characteristics. The mobilization of side friction resistance along the pile requires relative displacement between the pile and the surrounding soil. When the pile displacement is absent or minimal, the side friction resistance cannot be fully developed. As the pile top load increases and transfers downward, a compression deformation gradient forms between the upper and lower parts of the pile, inducing relative displacement at the pile–soil interface. Consequently, the side friction resistance in the upper surrounding soil is activated first. As the pile–soil relative displacement continues to increase, the side friction resistance in the deeper soil layers progressively develops, contributing the majority of the bearing capacity. As displacement continues to increase, the soil at the pile tip undergoes compression, forming an arching effect that reinforces the stress level around the pile tip soil and further enhances the side friction resistance at the pile end. Both side resistance and end resistance are fully mobilized when the pile-soil system reaches slip failure, reaching the ultimate state. Prior to failure, the enhancement of side friction resistance near the pile tip indirectly influences the mobilization sequence of side friction resistance within the adjacent reinforcement zone, resulting in a cycle of reduction, reserve, and reactivation. This fully reflects the spatiotemporal differences in the mobilization of side and end resistances. Such nonlinear interaction governs the load-settlement behavior of the individual pile.

This on-site static test is destructive in nature. To ensure the acquisition of objective and accurate data under safe conditions, a “coarse-to-fine” loading increment strategy was adopted, with loading increments of 1000 kN, 800 kN, and 600 kN for test piles S1, S2, and S3, respectively. Analysis of the Q-s curves, s-lgt curves, pile axial force, and side friction distribution indicates that the pile-soil system progresses from yielding to the ultimate state mainly by increasing the load level stepwise. The minimum increment of 600 kN, which is less than twice the pile-end resistance, allowed observation of mechanical deformation behaviors at different stages and provided data support for evaluating the bearing capacity of the pile foundation in this area. Comprehensive analysis shows that the test for ultimate bearing capacity closely correlates with the sharp drop point in the pile-soil system response, which effectively reveals the degrees of mobilization of side friction resistance and end bearing resistance. Considering that side friction resistance is mobilized prior to end resistance, to accurately capture the ultimate bearing capacity state of the pile foundation, loading increments should not exceed twice the pile-end resistance.

Laboratory shear tests

The soil samples for this shear test were taken from near the pile top of test pile S2. Figure 21 illustrates the internal and surface morphologies of the pile-soil interface specimens at saturation levels of 50%, 67%, and 80% when shear displacement reached 15 mm. A distinct shear plane was observed inside the specimen at the pile-soil interface at 50% saturation, inclined approximately 35° to the shear direction, with shear marks on the upper surface about 8 mm long. The angle between the shear plane at the rear of the specimen and the shear direction slightly decreased to about 34° at 67% saturation, and an almost horizontal slip surface appeared in the middle front section, shear marks on the upper surface extended to about 10 mm. At 80% saturation, no clear internal shear plane was observed within the specimen, but pronounced shear marks on the upper surface measured about 15 mm in length. These observations indicate that failure at the interface is mainly due to slip along the contact surface and the soil’s shear failure near the interface. Internal soil shear failure occurs at lower saturation, implying that the interface shear strength between the pile and the surrounding soil exceeds that of the soil mass. Conversely, slip failure along the interface predominates at higher saturation, indicating that the shear strength at the pile–soil interface is lower than that of the surrounding soil.

Figure 22 shows the shear stress–shear displacement curves at saturation levels Sr of 50%, 67%, and 80%. The initial yield points show little difference as saturation increases, but the shear displacement at yield completion becomes progressively larger, resulting in a longer yielding phase. At Sr = 50%, the curve levels off near a shear displacement of about 4 mm, marking the end of yielding. At Sr = 67%, yielding ends near 6 mm. At Sr = 80%, yielding concludes at approximately 7.8 mm of displacement. The relationship between peak shear stress and normal stress at different saturation as shown in Fig. 23. Table 7 presents the shear strength results. It can be observed that as saturation Sr increases from 50 to 80%, the cohesion decreases significantly, while the friction angle shows only a slight reduction. This indicates that saturation mainly weakens cohesion when influencing the shear strength of the pile-soil interface specimens. Under stress concentration effects at the contact surface, shear failure at Sr = 80% occurs on the upper surface of the pile-soil interface specimen.

Microscopic analysis

Table 8 presents the distribution of principal particle axes and corresponding entropy values for different shear displacements, as analyzed by the IPP software. Figure 24 shows histograms of principal particle axis orientations at various shear levels. Figure 25 depicts the relationship curve between shear displacement and entropy. Figure 24 displays histograms of principal particle axis orientations for saturation levels of 50%, 67%, and 80% at shear displacements of 3 cm, 10 cm, and 15 cm. The histograms are approximately symmetric. From 0° to 80°, the bar heights gradually increase. At the 80°-100° interval, where the inclination approaches the horizontal direction, the bar heights increase sharply. The bar heights gradually decrease between 100° and 180°. Overall, the heights of the histograms progressively rise as shear displacement increases from 3 to 15 mm, indicating that with the development of shear, the internal particle structure exhibits increasingly pronounced orientation. In Fig. 25, the long-term load–deformation curves demonstrate that the roof support sustains higher ultimate resistance than the floor support. This can be attributed to the roof being subjected to compressive arching action, which enhances its bearing capacity, whereas the floor undergoes continuous uplift and shear slip that reduce its effective stiffness. A quantitative assessment indicates that the ultimate bearing capacity of the roof support is nearly 1.4 times that of the floor support. This finding underscores the asymmetric mechanical behavior of the roof and floor, which should be carefully considered in the design of support systems.

The curve depicting the relationship between shear displacement and entropy was plotted and analyzed in conjunction with macroscopic deformation and histogram data. The principal axes of mineral particles were distributed relatively uniformly at a shear displacement of 3 mm, with entropy values ranging from 0.937 to 0.999. This indicates a low degree of particle orientation and high disorder, reflecting internal structural behaviors such as dragging, slip, rotation, and damage characteristic of elastoplastic deformation. Over 50% of particle principal axes aligned with the shear direction at 10 mm shear displacement, and entropy values ranged between 0.594 and 0.763. This signifies a higher degree of structural orientation and reduced disorder, suggesting that most mineral particles had largely completed their directional adjustment. More than 60% of principal axes aligned with the shear direction at 15 mm shear displacement, with entropy values between 0.575 and 0.635. Mineral particles underwent minor structural adjustments or damage repair, reflected by a stabilized, nearly horizontal segment on the entropy curve. Comparing entropy variations across saturation levels reveals that, for the same shear displacement, higher saturation corresponds to lower entropy values. This indicates that water’s weakening effect accelerates coordinated particle deformation, making the deformation more thorough. However, subsequent micro-adjustments are minimal once coordination is nearly complete. Furthermore, greater particle orientation facilitates the formation of continuous shear planes, which reduces shear strength. Shear stress tends toward a steady state when orientation stabilizes. The combined analysis of particle histogram distributions and entropy changes effectively explains the observed variations in the curve of shear stress versus shear displacement.

Similarly, the deformation of the soil surrounding the static load test pile can be examined from a microscopic perspective to observe its variation trends. After the static load test was completed, undisturbed soil samples were collected from the vicinity of test pile S2, excavating from the pile top to a depth of 1.5 m. Samples were collected at intervals of 10 cm, 20 cm, 30 cm, and 40 cm from the pile perimeter for scanning electron microscopy observation, and the principal axis information of the particles was extracted.

The distribution of particle principal axes and the corresponding entropy values at various distances from the pile perimeter are presented in Table 9. Histograms of particle principal axis information at distances of 10 cm, 20 cm, 30 cm, and 40 cm from the pile perimeter are presented in Fig. 26. When the soil is 10 cm from the pile perimeter, 66% of the particle principal axes are oriented between 80° and 100°, aligned with the shear direction, while the remaining eight angle intervals collectively account for 34%. The particle principal axis distribution histogram exhibits a pronounced peak in the middle with lower values on both sides, rapidly decreasing from the center outward, and the entropy value is 0.590. At 20 cm from the pile perimeter, 28% of the particle principal axes align with the shear direction, with the other eight angle intervals ranging from 5 to 12%. The histogram still shows a central peak tapering towards both sides, though the height differences among intervals are less pronounced, the entropy value is 0.942. At 30 cm from the pile perimeter, the particle principal axes are uniformly distributed across all angle intervals, ranging between 10 and 13%, with the histogram bars nearly equal in height; the entropy value is 0.994. A similarly uniform distribution is observed across all nine angle intervals at 40 cm from the pile perimeter, ranging from 10 to 12%, with histogram heights close to each other and an entropy value of 0.997.

The entropy value curve for soil at different distances from the pile perimeter is presented in Fig. 27. Within the 0–40 cm range around the pile, the closer the soil is to the pile, the lower the entropy value and the better the particle structural orientation. Notably, coordinated deformation of particles is particularly evident within 0–20 cm, less pronounced between 20 and 30 cm, and nearly absent from 30 to 40 cm. This indicates that the pile’s frictional influence on the surrounding soil radiates outward radially, forming a radial plastic shear zone of 0–30 cm thickness-significantly smaller than the influence range-depth relationship 28.

Combined with the shear test results where saturation (Sr) increases from 50 to 80%, and the shear failure surface moves from inside the specimen toward its upper surface, the summary is as follows:

-

(1)

The settlement deformation failure surface during this static load test occurred near the pile-soil interface;

-

(2)

The pile-soil interface failure did not strictly occur as slip along the exact pile-soil contact surface. Influenced by pile length, diameter variations, and pile surface roughness, shear failure during pile settlement deformation actually involves soil within a certain thickness adjacent to the pile surface;

-

(3)

The thickness of the pile-soil interface affected in this test ranges from 0 to 30 cm.

When pile settlement deformation is slight, the microstructure orientation at the pile-soil interface is disordered, with entropy values close to 1, indicating that side friction resistance has just been activated. The internal structure at the pile-soil interface undergoes coordinated deformation as settlement deformation increases, causing entropy values to decrease and side friction resistance to increase.

As settlement deformation continues to increase, no fracture failure occurs within the plastic shear zone, and the coordinated deformation of internal structural orientation is fully achieved. At this stage, the entropy value remains stable, and the side friction resistance reaches its ultimate state, approaching a steady value. When settlement deformation continues to increase beyond this point, fracture failure occurs in the plastic shear zone, leading to a reduction in side friction resistance and a renewed onset of structural coordination. The static load test can be concluded once total settlement exceeds 40 mm and exceeds five times the settlement observed in the preceding load stage. Therefore, loading is generally ceased before fracture failure occurs in the plastic shear zone. Excavation near the pile top showed no fracture traces in the surrounding soil. This is further corroborated by the time-dependent curve of lateral frictional resistance presented in Fig. 18, which exhibits no intersecting decline.

The development of side resistance in this site differs from that of typical soft coatings or the inter-pile soil. Instead, it reflects the mechanical behavior of a plastic shear band of finite thickness. Therefore, the correlation between shear stress and side resistance can be established through shear testing of the plastic shear band.

Comparison between experimental and calculated values

The relationship between shear stress and shear displacement was found to follow a hyperbolic model based on the experimental results29. To establish the relationship among shear stress, saturation, and shear displacement, the results of the shear tests were normalized, with the ratio of shear stress to saturation (τ/Sr) plotted as the ordinate and shear displacement (s) as the abscissa. Through data fitting, it was found that the resulting curve (Fig. 28) still conforms to the hyperbolic model, namely:

where τ denotes the shaft resistance, Sr represents the degree of saturation, and s denotes the displacement difference between the pile and the surrounding soil. The parameters a and b are undetermined coefficients.

By rearranging Eq. (8), the following expression is obtained:

It can be concluded that:

The reciprocal of both sides of Eq. (8) is taken, yielding:

From Eq. (10), it is known that the curve of sSr/t-s is a linear function. By plotting this curve (Fig. 29), parameters a and b for different saturation levels are obtained. The equation parameters are listed in Table 10.

y fitting the relationship curves between saturation and parameters a and b, the following expressions are obtained:

The fitted curves for a and b are shown in Figs. 30 and 31. It can be observed that once the saturation reaches a certain level, its increase has a more pronounced effect on parameter a, while the influence on parameter b remains relatively stable. This behavior is analogous to the effects of saturation on cohesion and friction angle. Therefore, a and b can be regarded as fitting coefficients representing cohesion and friction angle, respectively, with 1/a and 1/b corresponding to modulus and the maximum shear stress of the t/Sr-s curve at a given saturation. The parameters a and b in the hyperbolic shear model reflect the deformation characteristics of the pile–soil interface. Specifically, the parameter a is inversely related to the initial shear stiffness of the interface and can be interpreted as representing the cohesion-related component of shear strength. The parameter b controls the rate at which shear stress approaches its ultimate value with increasing displacement and is analogous to the friction angle component in classical shear models. Therefore, 1/a corresponds to the initial shear modulus, and 1/b approximates the peak shear resistance under a given saturation. These interpretations are consistent with the trends observed in the shear stress–displacement curves under varying saturation levels.

By substituting a and b into the fitted Eq. (8), the shear force transfer equations at the soil-pile interface under different saturation levels can be obtained.

To verify the rationality of the fitting equation, the saturation Sr was set at 67% and the normal stress at 15 kPa. Using the fitting formula, the side friction development curve at a depth of 1.5 m in the stratum during settlement deformation was calculated and plotted, then compared with the experimental curve; the comparison results are shown in Fig. 32. The comparison indicates that the shear stress calculated by the fitting formula from the indoor pile-soil interface shear simulation test aligns well with the side friction curve obtained from the on-site static load test during the initial and stable stages, with slight discrepancies observed in the yield stage. Analysis reveals that this difference is related to the loading methods: the on-site static load test employed load-controlled loading with a non-uniform shear failure rate, whereas the indoor shear test used displacement-controlled loading with a constant shear rate. Therefore, the rate and degree of shear strength development during yielding differ slightly.

It is also worth noting that the indoor shear tests were conducted under displacement-controlled loading, where the shear rate was kept constant, allowing a gradual development of shear stress and yielding behavior. In contrast, the field static load tests adopted a load-controlled method, in which loading was applied incrementally and held constant to monitor settlement. This difference in control modes results in distinct deformation paths: displacement-controlled tests produce smoother shear stress–displacement curves, while load-controlled tests may exhibit more abrupt transitions during yielding. These methodological differences partly explain the slight deviation between fitted shear curves and measured side friction development curves in the mid-yield stage.

Relationship between static load test and shear test

In this study, the term “plastic shear zone” refers to a finite-thickness region adjacent to the pile–soil interface that undergoes progressive plastic deformation during pile settlement. Unlike a theoretical zero-thickness slip plane, this zone includes disturbed soil that experiences coordinated particle rearrangement, strain softening, and eventual yielding. Its development is driven by relative displacement between the pile and surrounding soil, and it governs the mobilization of side friction resistance in highly saturated strata.

The comparison between the field static load test and the indoor shear test is as follows:(1) After instability in the pile-soil system throughout the test of static load the entropy of the internal soil particle principal axis structure at 10 cm from the pile perimeter is basically the same as the entropy values at 10 cm and 15 cm shear displacements in the shear test, indicating consistent degrees of shear deformation and failure reflected by the microstructural orientation in both tests. (2) The settlement deformation failure in the static load test predominantly occurs within approximately 20 cm of soil adjacent to the pile perimeter. At 80% saturation in the shear test, the failure plane is located at the upper surface of the specimen. From a scale perspective, the shear failure locations in both tests are similar, occurring near the interface, i.e., the pile-soil boundary. (3) When the pile settlement deformation failure takes place at the pile-soil interface, the shear stress calculated by the indoor pile-soil interface shear test fitting formula corresponds well overall with the lateral friction development curve obtained from the field static load test. This demonstrates that the correlation between lateral friction and shear stress can be established through shear tests of the plastic shear zone.

The above three points indicate that both the lateral friction-related curve and the shear stress-related curve characterize the soil behavior under shear action. Moreover, the lateral friction-settlement deformation curve can be regarded as the expression of the shear stress–shear displacement curve under specific conditions, specifically referring to the shear behavior of the pile-soil interface plastic shear zone subjected to vertical loading.

Conclusion

In this study, based on the vertical compressive static load test of a secondary-tier single pile in the Weihe River area, pile-soil interface indoor shear simulation tests, and quantitative analysis of microstructural characteristics, draws the following conclusions:

-

(1)

For static load tests used to provide design references, a loading scheme of "loose first, then dense" is recommended, with load increments not exceeding twice the end bearing resistance.

-

(2)

During the settlement deformation process of the pile–soil system, the pile exhibits favorable elastic compressive deformation; lateral resistance at different depths shows layered asynchronous activation characteristics. Although friction piles have smaller end bearing resistance, the reinforcement effect of the end resistance on lateral resistance near the pile tip and its activation sequence should not be overlooked. In the tested area, the lateral friction resistance along the pile shaft is segmented into three segments: HⅠ — normal lateral friction activation zone, HⅡ — lateral friction reserve zone, and HⅢ — pile tip reinforcement zone; near the pile top, the pile–soil interface thickness ranges from 0 to 30 cm.

-

(3)

With increasing saturation, the soil’s shear strength weakens; during shearing, the internal structure’s orientation intensifies and entropy decreases. Failure mode evolves from soil self-shear near the interface to slip failure along the interface. After a certain shear displacement, entropy stabilizes and shear stress reaches its limit state.

-

(4)

In strata with higher saturation, the pile settlement deformation process, pile-soil interface shear failure degree, failure location, and lateral friction resistance behavior closely resemble those observed in shear tests. This indicates that the lateral friction-settlement curve can be regarded as the expression of the shear stress–shear displacement curve under specific conditions, which characterizes the shear behavior of the plastic shear zone at the pile-soil interface subjected to vertical loading.

-

(5)

The shear entropy curve, derived from the orientation distribution of soil particles, reflects the development of internal structural coordination within the plastic shear zone. Its evolution correlates well with the mobilization and eventual yielding of side resistance during pile settlement. This suggests that orientation entropy can serve as a supplementary indicator for identifying plastic shear band formation, offering new guidance for pile foundation design in saturated soils.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sales, M. M., Prezzi, M., Salgado, R., Choi, Y. S. & Lee, J. Load-settlement behaviour of model pile groups in sand under vertical load. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 23, 1148–1163 (2017).

Sarma, K. & Saggu, R. Implications of thermal cyclic loading on pile group behavior. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 146, 4020114 (2020).

Theland, F. et al. The influence of pile–soil–pile interaction on the vertical response of end-bearing pile groups in soil on bedrock subjected to a vertical load at the soil’s surface. Transp. Geotech. 51, 101525 (2025).

Wang, Y.-Y. et al. Laboratory study on pile jacking resistance of jacked pile. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 154, 107070 (2022).

Xiong, W., Li, Z., Hu, D. & Li, F. Performance analysis of pile group installation in saturated clay. Appl. Sci. 14, 8321 (2024).

Akgüner, C. & Kirkit, M. Axial bearing capacity of socketed single cast-in-place piles. Soils Found. 52, 59–68 (2012).

Bai, L., Gong, S., Xu, L., Bai, X. & Huang, Z. Finite element simulation study on vertical bearing characteristics of single pile with ram-compacted bearing sphere. PLoS ONE 18, e0291719 (2023).

Bai, X., Liu, X., Zhang, M., Wang, Y. & Yan, N. Ultimate load tests on bearing behavior of large-diameter bored piles in weathered rock foundation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 8821428 (2020).

Feng, H., Dai, X., Chen, S. & Chen, J. Research on bearing characteristics of open-ended pipe piles under static load. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 5572898 (2021).

Han, G. B. & Wan, Z. Analysis of bearing capacity of post-end grouting pile under vertical load. Strength Mater. 57, 178–188 (2025).

Kong, G., Liu, Z., Wang, L., Liu, H. & Yang, Q. Experimental studies on the behavior of a single shaped pile under oblique pullout loads. Acta Geotech. 18, 4733–4746 (2023).

Liu, Y., Xu, P., Liu, X., Ma, S. & Huang, Z. Weakening characteristics of pile group foundations in clayey soil under vertical cyclic loading: Experimental and numerical investigation. Ocean Eng. 313, 119317 (2024).

Norkus, A. & Martinkus, V. Experimental study on bearing resistance of short displacement pile groups in dense sands. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 25, 551–558 (2019).

Qian, Y. et al. Effect of pile spacing on load bearing performance of NT-CEP pile group foundation. Buildings 15, 1404 (2025).

Sun, Z. & Kong, G. Load transfer behavior of multiangle helical piles embedded in silty clay under vertical and oblique loads. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 151, 4025062 (2025).

Tian, C., Li, P., Yv, R., Li, Y. & Li, B. Research on the vertical bearing capacity of concrete-filled steel tube composite piles by mixing method. Appl. Sci. 15, 5022 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. On-site full-scale load test and reliability evaluation of prefabricated bridge substructure for “pile–column integration”. Appl. Sci. 12, 5520 (2022).

Xiao, K., Guo, S., Wen, J., Han, J. & Yang, X. Prediction method of vertical ultimate compressive bearing capacity of single pile in soft soil considering the influence of gravity. Geofluids 2023, 1–24 (2023).

Xiao, Y., Liu, X., Zhou, J. & Song, L. Field test study on the bearing capacity of extra-long PHC pipe piles under dynamic and static loads. Sustainability 15, 5161 (2023).

Yan, N. et al. Load-bearing characteristics and optimization design for rock-socketed bored piles in sandy silty clay in coastal areas. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 190, 109207 (2025).

Zhao, X. et al. Vertical compressive bearing performance and optimization design method of large-diameter manually-excavated rock-socketed cast-in-place piles. Sci. Rep. 13, 14234 (2023).

Srijan, S. & Gupta, A. K. Vertically and horizontally reinforced end-bearing stone column: An experimental and numerical investigation. Appl. Sci. 13, 11016 (2023).

Kong, G. et al. Effects of pile configuration on the group behavior of semi-floating energy piles. J. Build. Eng. 77, 107487 (2023).

Li, H. & Tamura, S. An existing pile efficiency method for the design of lateral new pile behavior in sites with existing piles. Can. Geotech. J. 60, 1188–1201 (2023).

Luan, L., Ding, X., Cao, G. & Deng, X. Development of a coupled pile-to-pile interaction model for the dynamic analysis of pile groups subjected to vertical loads. Acta Geotech. 15, 3261–3269 (2020).

Niu, J., Yang, Z., Yin, S. & Cheng, S. Integrated analysis of optimization and settlement characteristics in hybrid pile systems for reused foundations. Appl. Sci. 15, 3016 (2025).

Saggu, R. & Sarma, K. Pile group response to thermal cycles and associated alterations in soil response. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 149, 4023017 (2023).

Chandrasekaran, S. S., Boominathan, A. & Dodagoudar, G. R. Dynamic response of laterally loaded pile groups in clay. J. Earthq. Eng. 17, 33–53 (2013).

Gao, Y., Guo, Z. & Yuan, Q. Pile driving and the setup effect and underlying mechanism for different pile types in calcareous sand foundations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12, 133 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to their colleagues and laboratory staff for their valuable assistance during the experiments and data analysis.

Funding

This work was completed without external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xin Du organized the database, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, Liu Fengyin contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, X., Liu, F. Experimental study on vertical compressive bearing capacity of single pile in Weihe river second terrace. Sci Rep 15, 36427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20550-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20550-4