Abstract

Understanding the impact of rhizosphere soil properties on tobacco growth after land consolidation is crucial for optimizing agricultural practices. This study investigated the relationship between rhizosphere soil biochemical properties, enzymatic activities, and tobacco growth in three fields in Guizhou province. We found no significant differences in the biochemical properties, soil quality index, or enzymatic activities between tobacco plants exhibiting Good and Bad growth performance. Soil microbial activity was primarily limited by phosphorus, but there were no significant differences in carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus limitations between the two growth performance. Additionally, soil ecosystem multifunctionality showed no significant correlation with tobacco plant performance. These results suggest that while rhizosphere soil properties play a role, other factors such as microbial communities and management practices may have a more significant influence on tobacco growth after land consolidation. Further research is needed to explore these complex interactions and develop strategies to enhance tobacco production in post-consolidation environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Healthy soil is a critical foundation for achieving high yield and quality in tobacco production1,2. The availability of suitable arable land and soil fertility have often become constraints for the continuous and efficient development of tobacco production3. Comprehensive land consolidation in tobacco-growing regions can effectively enhance the utilization efficiency of arable land, expand the area available for tobacco cultivation, which benefit sustainable tobacco production in long term4,5. Nevertheless, land consolidation can disrupt the topsoil that has been cultivated for years, with intensive mechanical operations and subsoil plowing being key factors damaging the soil structure of farmland. This leads to an approximately 15% increase in topsoil bulk density and a 65% reduction in air permeability6. Moreover, the disturbances to soil biochemical processes and the impacts on plant growth caused by alterations in soil structure can persist for several years7. Soil organic carbon may decrease by 0.13–2.4 t C ha−1 yr−1 due to land consolidation8, significantly negatively impacting the structural integrity of the rhizosphere microbial network and the abundance of key microbial communities9. Ultimately, land consolidation results in uneven soil fertility and a diminished nutrient supply capacity10,11. Consequently, the suitability of tobacco fields for tobacco cultivation is significantly reduced in the short term. However, it remains unclear how soil quality affects tobacco growth after land consolidation.

Rhizosphere soil plays a vital role in plant growth, affecting nutrient acquisition, water retention and overall plant health12,13,14. The biochemical properties of the rhizosphere, such as soil organic matter, pH and soil texture, are key factors affecting microbial activity15,16,17. Recent studies have shown that soil enzymes are vital mediators affecting the interactions between microorganisms and soil nutrients and root exudates18,19. And soil enzymes are the vital factors that promote soil nutrient mineralization, fixation and depolymerization20,21,22. Tobacco, a high-value crop with substantial economic significance, is particularly sensitive to its growing environment, with its growth and yield being heavily influenced by soil conditions3,23,24. Although some studies suggest that soil microbial activity is key to tobacco plant performance25,26, the role of soil biochemical properties and enzymatic activities remains underexplored. Understanding how rhizosphere soil properties affect tobacco growth is therefore essential for optimizing tobacco production.

Therefore, we investigated the differences in rhizosphere soil biochemical properties and enzymatic activities between tobacco plants exhibiting good and poor growth performance, hypothesizing that these soil factors may significantly contribute to the observed variations in tobacco growth after land consolidation.

Results and discussion

Soil biochemical properties and SQI

The radar graphics show the soil biochemical properties under good and bad performance of tobacco growth in Site 1 (a), Site 2 (b), and Site 3 (c). Soil quality index (SQI) response to different tobacco growth in the three fields (d). Values are means ± standard error (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences between tobacco growths based on t-test (p < 0.05). pH; EC, electrical conductivity; SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; AP, available phosphorus; AN, available nitrogen; C_acq, N_acq, and P_acq represent soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus acquisition enzymatic activities, respectively.

The tobacco plant height, number of effective leaves, and leaf length and width of the good-growth phenotype were 1.45–1.52 times, 1.28–1.39 times, 1.17–1.55 times, and 1.25–1.65 times greater, respectively, compared to the bad-growth phenotype (Table 1). The biochemical properties of the rhizosphere soil did not show significant differences between the Good and Bad growth conditions across the three sites (Fig. 1; Table 2). In Site1, no significant differences were observed in any of the rhizosphere soil properties between the two conditions (Fig. 1a; Table 2). In Site2, the available nitrogen (AN) in the Bad condition was significantly higher than in the Good condition by 38.24% (Fig. 1b; Table 2), while no significant differences were observed in the other biochemical properties. In Site3, the SOC and AN of in the Bad conditions were higher than those of Good by 17.01% and 70.03%, respectively (Fig. 1c; Table 2). These differences were also reflected in the SQI between Good and Bad conditions. Specifically, the SQI of Good in Site2 was significantly higher than that of Bad by 21.10% (Fig. 1d), while no significant differences were observed at the other sites. Overall, apart from the significant differences in certain biochemical properties and SQI between Good and Bad across the three fields, no significant differences were observed in other aspects. These findings suggest that the growth of tobacco plants after land consolidation is not predominantly influenced by rhizosphere soil properties. While soil characteristics are important, other factors such as microbial communities and management practices significantly impact growth. Microorganisms play a vital role in plant growth and development by facilitating the uptake of soil nutrients and maintaining plant health27,28,29. Additionally, management practices like planting methods and irrigation are vital for optimizing growth conditions30,31,32,33. These factors, when combined, provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing tobacco growth post-consolidation. Further research is needed to explore the interactions be-tween these elements and develop strategies to improve tobacco production in such environments (Fig. 2).

Enzymatic activities and stoichiometry evaluation

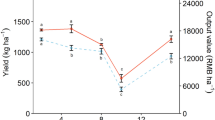

A scatter plot of soil extracellular enzyme stoichiometry under Good and Bad performance of tobacco growth in Site1, Site2, and Site3 (a). The enzymes were BG, β-glucosidase; BX, β-xylosidase; CE, β-cellobiosidase; NAG, β–1,4-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase; LAP, L-leucine aminopeptidase; ACP, acid phosphatase. Differences in vector length (b) and angle (c) of soil enzyme activities under good and bad performance of tobacco growth. Linear regression analysis to determine the relationship between microbial C limitation and microbial N/P limitation (d). Vector length represents microbial soil C limitation, and vector angle represents microbial soil N/P limitation. Values are means ± standard error (n = 5). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between lengths based on a two-sample t-test.

(a) Heat map shows the rhizosphere soil enzyme activities under good and bad performance of tobacco growth in Site1, Site2, and Site3. The C-acquisition enzymes include β-1,4-glucosidase (BG), β-cellobiosidase (CE), and β-xylosidase (BX); the N-acquisition enzymes include β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) and L-leucine aminopeptidase (LAP); the P-acquisition enzyme is acid phosphatase (ACP). (b) The rhizosphere soil ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) is calculated based on the average standardized Z-scores of the six rhizosphere soil enzyme activities. NS indicates no significant difference (p < 0.05) between the rhizosphere soils of different tobacco growth types at each site.

The analysis of soil enzymatic activities revealed no significant differences between the Good and Bad growth conditions, except for a notable increase by 69.71% in CE activity in the Bad condition at Site3 and a notable increase by 86.33% in CE activity in the Good condition at Site2 (Table 2; Fig. 3a). This suggests that while enzymatic activities play a role in nutrient cycling, they do not solely determine tobacco growth variations34,35,36. The vector analysis of enzymatic stoichiometry indicated that microbial metabolism across all sites was primarily limited by phosphorus, with no significant differences in phosphorus limitation between the Good and Bad conditions (Fig. 2a and c). Similarly, there is also no significant differences in microbial C limitation between Good and Bad conditions (Fig. 2b). These findings highlight the importance of phosphorus availability in microbial processes, but it also underscores the need to consider other factors influencing plant growth37,38. Furthermore, there was no significant correlation between soil microbial carbon and phosphorus limitations (Fig. 2d), which may indicate that the soil microbial community already adapted to the soil nutrient environment39,40. In addition, the soil ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) showed no significant differences between the Good and Bad conditions (Fig. 3b), indicating that EMF does not directly correlate with tobacco growth traits41,42. Based on the Pearson and Mantel test analysis presented in Fig. 4, we observed a lack of significant correlations between most soil biochemical properties and enzymatic activities with the EMF. This key finding suggests that tobacco growth may be influenced by factors beyond soil biochemical properties and enzymatic activities (Fig. 4), such as microbial communities and management practices, may be more influential in determining tobacco growth outcomes. These findings collectively emphasize the multifaceted nature of factors affecting tobacco growth and highlight the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between soil properties, microbial dynamics, and management strategies.

Correlation between soil indicators and tobacco plant phenotypic traits based on the Pearson and Mantel test. The colored matrix on the left represents the magnitude and direction of Pearson correlation coefficients (r) (see vertical color bar). The thickness of the connecting lines represents the magnitude of the Mantel correlation coefficient (Manlet’s r) (see legend on bottom left), and their color indicates the significance level (p-value) of the Mantel test (see legend on bottom right). pcarbon, pH; AP, available conductivity; SOC, soil organic carbon; TN, total nitrogen; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; AP, available phosphorus; AN, available nitrogen; BG. β-1,4-glucosidase; NAG, β-1,4-acetylglucosidase; CE, β-cellobiosidase; XYL, xylanase; ACP, acid phosphatase; LEU, leucine aminopeptidase.

Conclusion

This study has revealed that the biochemical properties, soil quality index, and enzymatic activities of rhizosphere soil do not significantly differ between tobacco plants exhibiting Good and Bad growth conditions following land consolidation. Although microbial activity across the three sites was strongly limited by phosphorus, there were no significant differences in carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus limitations between the two growth conditions. Additionally, the biochemical properties and enzymatic activities of the rhizosphere soil were not significantly associated with eco-system multifunctionality or the formation of tobacco plant traits. These findings suggest that while certain indicators may show minor differences, the overall growth of tobacco plants is not directly or entirely controlled by the rhizosphere soil properties. Instead, other factors such as microbial communities, management practices, and environmental conditions may play a more significant role. Further investigation is needed to explore these complex interactions and develop strategies to enhance tobacco production in post-consolidation environments.

Materials and methods

Site description and design

The experiment was conducted in three tobacco fields in Qingdi (Site1: 25.339°E, 105.168°N; Site2: 25.334° E, 105.169° N) and Jiaole (Site3: 25.328° E, 105.163° N) in Guizhou Province, where growth phenotype surveys and rhizosphere soil sampling were carried out. All fields had been planted with flue-cured tobacco for over 10 years, and land consolidation was undertaken in the recent 3 years. The initial soil pH for Site1, Site2, and Site3 were 5.9, 5.8, and 5.2, respectively, soil organic carbon (SOC) 15.0, 19.3, and 15.9 g kg−1, respectively, as well as soil total nitrogen (TN) were 1.6, 1.9, and 1.8 g kg−1, respectively.

Two classifications were established according to the growth of tobacco plants: plants with good and bad growth performance. Three adjacent tobacco plants with different growths were selected in each field. The rhizosphere soil corresponding to the good and poor growth of tobacco plants were designated as “Good” and “Bad”, respectively. The tobacco seedlings were transplanted in May 2023. In September 2023, during the maturity stage of the tobacco, we measured the plant height and the number of effective leaves. The third leaf from the top was also selected to record leaf width and length. The variety of all tobacco plants was flue-cured tobacco named “Yunyan 87”. Uniform organic fertilizer (rapeseed straw: 300 kg ha−1) was applied across all fields. Chemical fertilizers were also applied uniformly in all fields (300 kg N ha−1, 300 kg P ha−1, and 300 kg K ha−1).

Soil collection and analysis

Three soil cores were collected 10 cm away from the base of the tobacco plants and mixed to form a composite rhizosphere soil sample to minimize damage to the tobacco plants. A total of 5 mixed soil samples were collected from Good and Bad. Visible fine roots and plant residues were removed (< 2 mm). Partial rhizosphere soil samples were air-dried for the analysis of pH, electrical conductivity (EC), soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), and available phosphorus (AP). In contrast, the remaining samples were stored at 4 °C to measure dissolved organic carbon (DOC), mineral N (NH4+-N and NO3--N), and rhizosphere soil enzymatic activities. EC and pH were measured using a conductivity meter (DDS-307, INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China) and an electronic pH meter (FE28 and LE438, Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Switzerland), respectively, utilizing soil suspended with a soil–water ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v). SOC and TN were analyzed via the K2Cr2O7 oxidation–reduction titration method and the Kjeldahl method, respectively43. AP was extracted from 1 g fresh soil with 5 ml of 0.5 M NaHCO3, then the extracts of the samples and standards were measured by the malachite green colorimetric method. DOC was measured using a TOC analyzer (TOC-L, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan). NH4+-N and NO3--N were measured by a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA)44.

The soil quality index (SQI) was measured as follows:

where SLi represents the standardized value (0–1) for each rhizosphere soil biochemical property, Xmax is the maximum measured value of each rhizosphere soil biochemical property, and X is the measured value of each rhizosphere soil biochemical property.

Thereafter, the SQI was calculated based on the standardized values of all rhizosphere soil biochemical properties45:

where n represents the number of rhizosphere soil biochemical properties applied for the SQI.

Enzymatic activities and stoichiometry evaluation

The C- (i.e., β-Glucosidase (BG), β-xylosidase (BX), and β-cellobiohydrolase (CE)), N- (i.e., β-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (NAG) and L-leucine aminopeptidase (LAP)), and P-acquisition enzymatic activity (i.e., acid phosphatase (ACP)) were measured by fluorometric method46. In brief, 1 g of fresh soil was suspended in 50 mL of deionized water and shaken for 0.5 h. After stirring, 50 µL of soil suspension (400 µmol g−1), 100 µL of the corresponding substrate, and 50 µL of buffer solution were added to a 96-well microplate. Fluorescence values were then measured sequentially at 0 h, 1 h, and 2 h using a fluorescence microplate reader (Thermo 1510, MULTISKAN GO, USA). The activities of C-acq enzymes, N-acq enzymes, and P-acq enzyme were normalized as follows47:

Microbial carbon (C) limitation, nitrogen (N) limitation, and phosphorus (P) limitation were analyzed by calculating vector length and angle48:

where the vector length reflects the degree of microbial carbon (C) limitation, with longer vectors denoting a stronger emphasis on C-acq enzymes production relative to nutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P). Meanwhile, the vector angle distinguishes between N and P limitation: steeper angles (above 45°) suggest that P is the primary limiting nutrient, whereas shallower angles (below 45°) indicate that N limitation is more pronounced.

Evaluation of rhizosphere soil EMF

Soil ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) was represented by six rhizosphere soil enzymatic activities (BG, BX, CE, NAG, LAP, ACP). After the transformation of the standardization of individual functions, they were averaged to calculate the multifunctionality index49:

where X is the measured rhizosphere soil enzymatic activity, mean is the average of enzyme i, and SD is the standard deviation of enzyme i.

Statistical analysis

We employed a rigorous statistical protocol to compare the “Good” and “Bad” groups. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal data. For normal distributions, Bartlett’s test determined variance homogeneity, guiding the choice between Welch’s t-test (unequal variances) and independent samples t-test (equal variances). All of the following analyses were performed using R software (Version 4.4.1). The differences in parameters between the Good and Bad groups were analyzed using the t-test. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the parameters, and Bartlett’s test was applied to evaluate the homogeneity of variances between the Good and Bad groups before conducting the t-test. Radar charts, bar charts, and difference heatmaps were performed using the R (Version 4.4.1) packages “fmsb” and “ggplot2,” respectively. Rhizosphere soil biochemical properties, enzymatic activities, relationships with rhizosphere EMF, and tobacco traits were analyzed using the “linkET” and “vegan” packages in R (Version 4.4.1) to perform Mantel test.

Data availability

The data generated from the study will be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

References

Jacqueline, M. et al. Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils 37, 489–499 (2012).

Liu, L. et al. Bacterial and fungal communities regulated directly and indirectly by tobacco-rape rotation promote tobacco production. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1418090 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Returning ryegrass to continuous cropping soil improves soil nutrients and soil microbiome, producing good-quality flue-cured tobacco. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1257924 (2023).

Demirdogen, A. Land consolidation, cropland use, and vegetation productivity. Agribusiness 41, 21923 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. The impact of land consolidation on arable land productivity: A differentiated view of soil and vegetation productivity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 326, 107781 (2022).

Obour, P. B. & Ugarte, C. M. A meta-analysis of the impact of traffic-induced compaction on soil physical properties and grain yield. Soil Tillage Res. 211, 105019 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Effects of plastic residues and microplastics on soil ecosystems: A global meta-analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 435, 129065 (2022).

Lessmann, M. et al. Global variation in soil carbon sequestration potential through improved cropland management. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1162–1177 (2022).

Banerjee, S. et al. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. ISME J. 13, 1722–1736 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Impacts of ecological programs on land use and ecosystem services since the 1980s: A case-study of a typical catchment on the loess Plateau, China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 33, 3271–3282 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Newly created farmland should be artificially ameliorated to sustain agricultural production on the loess plateau. Land. Degrad. Dev. 31, 2565–2576 (2020).

Domeignoz-Horta, L. A. et al. Plant diversity drives positive microbial associations in the rhizosphere enhancing carbon use efficiency in agricultural soils. Nat. Commun. 15, 8065 (2024).

Kwak, M. J. et al. Rhizosphere microbiome structure alters to enable wilt resistance in tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1100–1109 (2018).

Zhu, B. & Cheng, W. Impacts of drying–wetting cycles on rhizosphere respiration and soil organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 63, 89–96 (2013).

Qin, S. et al. Linkage between temperature sensitivity of SOM decomposition and microbial communities depends on soil fractions. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17456 (2024).

Jiang, M. et al. Declining soil pH reduces microbial biomass-driven soil multifunctionality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 203, 105623 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Global hierarchical meta-analysis to identify the factors for controlling effects of antibiotics on soil microbiota. Environ. Int. 192, 109038 (2024).

Lian, J., Li, G., Zhang, J. & Massart, S. Nitrogen fertilization affected microbial carbon use efficiency and microbial resource limitations via root exudates. Sci. Total Environ. 950, 174933 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Oxygen availability regulates the quality of soil dissolved organic matter by mediating microbial metabolism and iron oxidation. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 7410–7427 (2022).

Wang, C. & Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic matter priming: The pH effects. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17349 (2024).

Li, J. Y. et al. Soil aggregate-associated organic carbon mineralization and its driving factors in rhizosphere soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 186, 109182 (2023).

Tian, Y. et al. Long-term soil warming decreases microbial phosphorus utilization by increasing abiotic phosphorus sorption and phosphorus losses. Nat. Commun. 14, 864 (2023).

John, R. M. et al. Economy-wide impact of a reduction in tobacco use in India. Tob Control 2023-058471 (2024).

Xia, H. et al. Soil Microbiological assessment on diversified annual cropping systems in China. J. Environ. Manage 371, 123284 (2024).

Jiang, C. et al. Isolation, identification, and mechanism analysis of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in tobacco. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1457624 (2024).

Rani, A. et al. Bacterial volatile organic compounds as biopesticides, growth promoters and plant-defense elicitors: Current Understanding and future scope. Biotechnol. Adv. 63, 108078 (2023).

Yin, X. et al. The role of rhizosphere microbial community structure in the growth and development of different tea cultivars. Appl. Soil Ecol. 206, 105817 (2025).

Adomako, M. O., Roiloa, S. & Yu, F. H. Potential roles of soil microorganisms in regulating the effect of soil nutrient heterogeneity on plant performance. Plants 10, 2399 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. A plant’s diet, surviving in a variable nutrient environment. Science 368, eaba0196 (2020).

Yao, W. et al. Legume-rice rotations increase rice yields and carbon sequestration potential globally. One Earth 8, 101170 (2025).

Ren, C., He, L. & Rosa, L. Integrated irrigation and nitrogen optimization is a resource-efficient adaptation strategy for US maize and soybean production. Nat. Food 15, 7748 (2025).

Feng, W. et al. Oat/soybean strip intercropping benefits crop yield and stability in semi-arid regions: A multi-site and multi-year assessment. Field Crops Res. 318, 109560 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Maize–Soybean rotation and intercropping increase maize yield by influencing the structure and function of rhizosphere soil fungal communities. Microorganisms 12, 1620 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Crop diversification increases soil extracellular enzyme activities under no tillage: A global meta-analysis. Soil Tillage. Res. 235, 105870 (2024).

Zhang, N. et al. Deciphering the performance and mechanisms of glycolipids in regulating crop growth in coastal saline-alkali soils: perspectives on soil properties and microbial communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 201, 105527 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enhanced activity of soil nutrient-releasing enzymes after plant invasion: A meta‐analysis. Ecol. Soc. Am. 100, e02830 (2019).

Bicharanloo, B. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus availability have stronger effects on gross and net nitrogen mineralisation than wheat rhizodeposition. Geoderma 405, 115440 (2022).

Bilyera, N. et al. Microbial tradeoffs in internal and external use of resources regulated by phosphorus and carbon availability. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 106, 103353 (2021).

Xue, W., Zhang, W. & Chen, Y. Heavy thinning temporally reduced soil carbon storage by intensifying soil microbial phosphorus limitation. Plant. Soil 484, 33–48 (2023).

Zhai, Z. et al. Trade-off between microbial carbon use efficiency and microbial phosphorus limitation under salinization in a tidal wetland. CATENA 209, 105809 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Soil multifunctionality predicted by bacterial network complexity explains differences in wheat productivity induced by fertilization management. Eur. J. Agron. 153, 127058 (2024).

Deng, H. et al. Soil ecosystem multifunctionality is strongly linked with crop yield after four decades chemical fertilization in black soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 368, 109007 (2024).

Bao, S. D. Soil Agro-Chemistrical Analysis 3rd edn (China Agricultural, 2000).

Jia, R. et al. Insights into the associations between soil quality and ecosystem multifunctionality driven by fertilization management: A case study from the North China plain. J. Clean. Prod. 362, 132265 (2022).

Kuzyakov, Y. et al. New approaches for evaluation of soil health, sensitivity and resistance to degradation. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 7, 282 (2020).

Yao, W. et al. Short-term reduction in cropping intensity improves soil quality of topsoil rather than subsoil. Land. Degrad. Dev. 34, 2393–2402 (2023).

Yao, W. et al. Increased seasonal fallow intensity enhanced the soil fertility of latosol in a tropical multi-cropping region. Soil Tillage. Res. 246, 106362 (2025).

Nayab, G. et al. Climate warming masks the negative effect of microplastics on plant-soil health in a silt loam soil. Geoderma 425, 116083 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Legume-based rotation enhances subsequent wheat yield and maintains soil carbon storage. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43, 64 (2023).

Funding

This study was financially supported by Science and Technology Project of Qianxinan Branch, Guizhou Tobacco Company (2022-3) and the Foundation of Guizhou Province Tobacco Company (2023XM21).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., W.Z., and H.Z.; methodology, R.J. and H.Z.; software, T.Y. and W.Y.; formal analysis, T.Y. and W.Y.; investigation, R.J.; resources, Y.L., Y.G., J.C., J.L., F.C. and W.Z.; data curation, R.J. and T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Y. and W.Y.; writing—review and editing, T.Y., W.Y., R.J., X.Q., Y.L., Y.G., J.C., B.Z., J.L., F.C., W.Z. and H.Z.; visualization, T.Y. and W.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Z. and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, T., Jia, R., Yao, W. et al. Rhizosphere soil properties may not determine tobacco growth after land consolidation. Sci Rep 15, 36425 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20560-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20560-2