Abstract

Recently, the field of phyto-nanomedicines has emerged as a promising avenue of research for generating sustainable, economically viable, and medically safe plant-based metal nanoparticles (NPs) with boosted therapeutic potential. Despite advancements, the literature remains inconclusive regarding the optimal extraction protocol for these plants to yield NPs with maximized functionality. Therefore, this study pioneered the use of two diverse UAE-Salvadora persica extracts; namely, aqueous and hydro-alcoholic, in the biological synthesis of green zinc and iron oxides NPs, aiming to resolve the research gap concerning the ideal extraction protocol for biomedical green NPs’ production. Our findings revealed that the alcoholic extract yielded NPs with superior phytochemical surface coating, and higher phenolic (42.94 ± 2.79 µg of GAE/mg of DW) and flavonoid (45.63 ± 1.88 µg of QU/mg of DW) contents, resulting in stronger antioxidant properties with IC50s ranging from 69.68 µg/mL to 180.26 µg/mL. Nevertheless, the aqueous extract demonstrated superior reducing efficacy, and its corresponding zinc oxide NPs exhibited the strongest cytotoxicity against A-431 cells (IC50:377.39 µg/mL), surpassing the activity of its parent crude extract. These extract-dependent nanoparticle variations were further confirmed and resonated via QTOF-LC/MS/MS and Principal Component Analysis analyses. Thus, our findings emphasize that selection of appropriate extraction protocols is crucial for therapeutic plant-based NPs’ development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of medical research, there is an imperative to produce environmentally benign pharmaceuticals with robust safety profiles to maintain sustainability. Since the last few decades, scientists have been following the path of synthesizing environmentally friendly, biologically active, and safe metal nanoparticles (NPs) using natural resources like microorganisms and plants. This is to reduce chemical waste and increase safety profiles of drugs. These natural resources are also inexpensive, and the synthesis is energy efficient compared to the chemical synthesis approaches involving several chemicals as reducing and stabilizing agents which lead to various biological and environmental risks due to toxicity of the used chemicals. The resulting studies in this field have been demonstrating improved physical and chemical properties, biocompatibility, and biological effects, in addition to being cost-effective over the chemically synthesized NPs. This is due to the bioactive phytochemical constituents that act as reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents for the NPs. Plant extracts contain a plethora of functional groups that exhibit a synergistic effect, enabling the reduction of metal precursors and concurrently mitigating the aggregation of the synthesized NPs, thereby preserving their colloidal stability. Finally, they coat the surfaces of the NPs, offering excellent linkers and binders for many biological elements, making them excellent candidates for biomedical applications. Plant extracts are favored over microorganisms for the green synthesis of metal NPs due to their enhanced scalability, faster synthesis rates, and improved biocompatibility within the human body1,2,3. Consequently, due to their minuscule size and exceptional capabilities, plant-based NPs emerge as highly promising candidates for a spectrum of biomedical applications, with a particular emphasis on drug delivery and development. These unique characteristics endow them with the remarkable ability to effectively penetrate and navigate through the most intricate biological microenvironments, including the tiniest capillaries, blood vessels, and biological junctions. This translates to a reduction in the requisite dosage, minimization of adverse effects, and an overall improvement in patient adherence to the prescribed therapeutic regimen4,5,6,7. Previous literature studies reveal that NPs synthesized with the aid of phytochemicals can potentiate the biological activities of the stand-alone plant extracts or metal NPs. This synergistic effect is primarily attributed to an enhancement in bioavailability and a concomitant improvement in therapeutic efficacy8,9.

A diverse array of metals, including silver, gold, chromium, copper, zinc, and iron, can be incorporated into the synthesis of plant-mediated NPs7,10,11,12,13. In the present investigation, the synthesis process will specifically utilize zinc and iron as the metallic precursors. In fact, Zn is considered to be among the most promising and biocompatible metallic candidates for the fabrication of NPs utilizing natural-based resources since zinc is one of the most important elements that presents normally in the human body tissues in large amounts14. These NPs exhibit a unique set of physicochemical properties that render them highly attractive for a wide spectrum of applications. As an illustrative example, zinc NPs synthesized with the aid of plant extracts have demonstrated a spectrum of significant pharmacological activities, particularly, encompassing antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer properties15,16. In a recent study, one-pot synthesized neem leaves-mediated metal oxide and noble metal ZnO@Ag have demonstrated exceptional antibacterial effects against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa3.

Salvadora persica (SP; traditionally known as Miswak or Arak tree), belongs to the family Salvadoracea and is widespread in arid places in Africa, Asia, and Arab countries. It is widely grown in the streets of the UAE and has many medicinal uses. The different organs of SP are utilized in countless folk uses, including cosmetics, food, fuel, hygiene, and human medicine. Its branches and roots are widely used as tooth cleaning sticks in the Middle East and some Asian and African cultures. Its green leaves, fruits and small stems are added to food and used in traditional herbal therapy to treat asthma, cough, and rheumatic diseases17. SP characterization describes a total of 76 compounds which belong to a wide array of chemical classes like phenolic acids, flavonoids, sulfur-containing compounds, alkaloids, sterols, and fatty acids18. Also, it showed a powerful effect in the treatment of many skin diseases19. Recently, the importance of SP as an anti-cancer candidate has increased when it was found that the alcoholic extract of the stem and the fruits were effective against many types of cancer cells20. The effect of stigmast-5-en-3β-ol and coumarins, which were separated from SP, on murine mouse melanoma was studied and the extract was found to delay the growth of cancer in mice21. GC-MS analysis of the ethanol extract of SP fruit revealed the presence of known anticancer agents, such as eicosane, and formyl colchicine22.

According to the National Cancer Institute, a 50% increase in cancer incidence is projected by 2050, necessitating the development of novel anticancer agents with robust safety profiles23. As mentioned above, green NPs, in general, are characterized by their diminutive size and unique physicochemical properties, thus enhanced intracellular bioavailability. Given the established anticancer properties of ZnO and Fe2O3 NPs and the demonstrated therapeutic efficacy of SP in addressing various dermatological conditions, this study hypothesizes that the synergistic combination of these entities will result in the formulation of potent natural-based NPs for the targeted treatment of skin malignancies.

Provided that different solvents extract unique active phytocompounds from the plants, it is expected that the choice of the extraction protocol will influence the physicochemical and biological properties of the resulting green NPs24. The literature lacks a definitive consensus on the optimal extraction protocol for SP, hindering the production of maximally functional NPs. The available SP-based NPs’ reports did not explain their choice of specific extraction protocol over alternatives. Therefore, we consider it essential to carry out a thorough investigation of different extract types of SP to obtain green NPs with optimized activity for our intended application and to elucidate the impact of SP extract type on the physicochemical and biological characteristics of its derived NPs. It is worth noting that this is the first study to thoroughly address this issue using the aerial parts of UAE-grown SP. Zinc and iron oxides NPs were synthesized using aqueous (SQ) and hydroalcoholic (SC) extracts derived from the aerial parts of SP cultivated in the UAE. The resulting NPs were subjected to comprehensive physical and chemical characterization, as well as in vitro evaluation of their antioxidant and skin anticancer activities. Furthermore, the chemical profiles of the employed extracts were comprehensively investigated to identify their marker compounds, enabling an assessment of their influence on the observed properties and activities of the synthesized NPs.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Absolute 99.8% ethanol and absolute methanol were obtained from Honeywell (Germany). Anhydrous free-flow potassium bromide, extra pure zinc acetate-2-hydrate, iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (ACS reagent, 97%), folin & ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, gallic acid-1-hydrate extra pure, potassium persulfate (ACS reagent, 99+%), 98% aluminum chloride, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS), potassium acetate reagent plus ≥ 99.0%, sodium carbonate, acetonitrile, ammonium formate and quercetin were bought from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. Methanol, formic acid, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Fisher Scientific, UK. Milli-Q Water was obtained from Millipore, USA.

Preparation of extracts

Fresh aerial parts’ samples of S. persica (stem, leaf) were collected from United Arab Emirates University farms in Al-Ain, UAE in June 2022. The plant material was authenticated by Dr. Mohamed Taher, head of the herbarium in Biology department at United Arab Emirates University. A voucher specimen of S. persica was reserved in the herbarium of college of Science at the United Arab Emirates University, with a serial number of UAEU-NH0014687. The fresh materials were rinsed, air-dried, and crushed using a home blender, then the dried powders were used for the preparation of aqueous and hydroalcoholic extracts via decoction and maceration, respectively. Decoction was performed by heating 266.92 gm of the plant material in deionized water at 60 °C for 3 h with continuous stirring at 1500 RPM. In contrast, the hydro-alcoholic extract was prepared by macerating 266.92 gm of the plant crushed powder in 80% ethanol. Afterward, filtration and evaporation were performed to obtain the aqueous and alcoholic crude extracts. Evaporation was done using Buchi Rotavapor R-200 equipped with Buchi heating bath B-490, Buchi vacuum pump interface I- 300, V600, and Julabo cooling system FP50 of Germany. Exhaustive extraction was done for both types of extracts by repeating the previous steps several times, leading to the production of total yields of 123.91 gm (46.42%), and 55.64 gm (20.85%) of aqueous and hydro-alcoholic crude extracts, respectively.

Synthesis of the nanoparticles

A method following Zhan et al. was used to fabricate Fe2O3 NPs with some modifications, using both aqueous and 80% ethanolic extracts25. Briefly, 1.6212 g of FeCl3·6H2O (0.02 M) were mixed with 300 mL of deionized water and added to 100 mL of the plant extract (2 gm). The mixture was refluxed for 90 min at 55–60 ℃ at 500 RPM. The reaction mixture was left overnight to cool down. After that, the mixture was centrifuged and washed for 3–5 min at 4000 RPM with deionized water and ethanol, three times each. The NPs were left to air dry overnight. Afterward, they were weighed, ground, and stored for further analysis. Regarding the fabrication of ZnO NPs, it was performed according to the method executed by Ashraf et al. 2023, with some modifications, using both aqueous and 80% ethanolic extracts26. In brief, 10 mL of zinc acetate dihydrate (1 g/mL) was mixed with 100 mL extract (2.37 g and 4.6 g, for alcoholic and aqueous extracts respectively). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h at 55–60 ℃ and 500 RPM. Afterwards, the solution was allowed to cool down, followed by centrifugation to obtain the ZnO NPs at 4000 RPM for 3–5 min. The collected NPs were then washed with deionized water and ethanol, 3 times each, and finally, left to air dry overnight and stored for further analysis (Fig. 1). The modifications introduced to the original followed protocol include operating the synthesis procedures at low temperatures instead of high temperatures, followed by air drying of the obtained NPs to avoid decomposition of the extracts’ phytoconstituents that coat the NPs27. As we mentioned above that the bioactive organic metabolites constituting the plant extract act as powerful reducing, stabilizing, and capping agents during the synthesis process of the NPs. So, they accelerate reduction of metal precursor to form the metal NPs, in addition to coating these NPs. This coating provides high stability and boosts the biological activity for the NPs. Thus, it is important to preserve these organic compounds during the whole synthesis process to achieve the maximum stability and effectiveness of the NPs. It is worth noting that using two different sorts of extracts allows for evaluating how extraction methods affect the physicochemical and biological properties of the synthesized green NPs, as different solvents extract unique active constituents24. These approaches aim to attain the highest quality and potency of NPs.

Characterization of the nanoparticles

The synthesized NPs were characterized using UV-Vis spectrophotometry, Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-Ray (SEM-EDX), and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)- Zetasizer. UV-Vis spectrophotometry was used to analyze the optical properties of the resulting NPs. To identify the size, shape, surface morphology, and agglomeration state of the particles, SEM was applied. EDX analysis was conducted to determine the elemental composition of the samples understudy, while FT-IR technique was employed to confirm the coating of the NPs with the plant phytochemical constituents via molecular analysis. The crystallinity of the samples was examined by XRD. Also, DLS was applied to provide information about the size range and surface charge of NPs under investigation28.

UV visible spectrophotometer

The plasmon resonance of the resulting NPs was identified by measuring the NPs suspended in 50% ethyl alcohol using Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer from Agilent Technologies Ltd, Malaysia. Spectral data were recorded within the range of 200–800 nm to identify the characteristic peaks confirming the formation of ZnO and Fe2O3 NPs.

The obtained data of the measured absorption spectra of the formulated NPs were utilized to determine the band gap energy of each of the biosynthesized NPs. Tauc’s equations (Eqs. 1–3) and plotting for direct band gap material was applied for this purpose. Also, this will help study the influence of the extract type on the optical band gap (Eg) of the fabricated samples.

where hv is the photon energy, α is absorption coefficient, λ and A are the wavelength and absorbance obtained from the absorption spectra of the nanoparticles, respectively. Furthermore, t is the cuvette pathlength which was determined as 1 cm, and m is the direct allowed transition process, and its value is 1/2. Afterward, y is plotted versus hv to determine the energy gap (Eg) through extrapolation of the linear portion near the absorption edge back to y = 0. The intercept on the hν axis is the Eg29. The calculation of Eg was done using Origin® software by fitting the linear line and dividing the obtained linearity intercept by the slope.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX)

Quattro SEM equipped with EDX detector of Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA was utilized for images’ capturing of the fabricated NPs and mapping their elemental compositions. The instrument was operated at a high vacuum with an accelerating voltage of 10–30 kV and a magnification of 10,000–20,000 X.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

The XRD patterns of the bioformed NPs were determined using Rigaku MiniFlex 600-C Benchtop Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Instrument, Rigaku Co. Instruments, USA, with a CuKα X-ray (λ = 1.542 Å) at 40 kV and 15 mA. A continuous scan at 2θ/ θ angle ranging from 10° to 80° was applied to analyze the samples with a scanning rate of 1°/min. The output peaks’ matching, and analysis were performed using Match software.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The Malvern Zetasizer Nano DLS (Malvern Instruments, UK) was utilized in this study to measure the mean particle sizes (z-average) and zeta potential of the samples. Prior to measurements, the samples were diluted with ethanol to achieve an appropriate scattering intensity. The measurements were conducted at a temperature of 25 °C and a flow rate of 0.500 mL/min, with zeta and size analyses performed at measurement positions of 2 mm and 4.65 mm, respectively. Zeta potentials and particle sizes were obtained by averaging the results of three runs, with up to 18 and 126 measurements using clear disposable cells and cuvettes, respectively.

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

The Nicolet NEXUS 470 FT-IR Spectrophotometer from Thermo Scientific, USA, was employed to discern the functional groups of the organic phytochemicals participating in the reduction, stabilization, and capping of the NPs, as well as to determine the peaks associated with the metal itself. The samples, weighing 0.002 g, were thoroughly ground, and mixed with KBr (0.2 g). This mixture was then compressed using a hydrolytic compressor to create a thin disc, which underwent analysis within the range of 400–4000 cm− 1. The analysis involved an average of 64 scans at 25 cm− 1 spectral resolutions and a laser frequency of 15798.3 cm− 1. The spectrum was shown in transmittance % mode.

Chemical investigation

Total phenolic content (TPC)

The determination of total phenolic content within both crude extracts of SP and their bio-fabricated NPs was executed utilizing the Folin-Ciocalteu protocol30. This method is predicated on the capacity of phenolic compounds to induce a reduction in Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, thereby producing molybdenum–tungsten complexes that exhibit a discernible blue hue which is quantifiable through spectrophotometry. The intensity of this coloration is directly proportional to the concentration of phenolic compounds within the reaction medium31. In brief, 100 µL of the sample (1 mg/mL) was amalgamated with 125 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 750 µL of 15% w/v sodium carbonate solution within a test tube. The total volume was adjusted to 5 mL with distilled water and meticulously mixed. A correcting blank was prepared accordingly, substituting the sample with the solvent utilized for sample solubilization (80% methanol). Following an incubation period of 90 min in darkness at room temperature, measurements were taken at 765 nm using a Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies Ltd, Malaysia). The TPC of the sample was quantified as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents per milligram of the sample’s dry weight (µg of GAE/mg of DW). This calculation was facilitated by employing the average absorbances of the samples and the linear equation derived from the standard curve constructed with gallic acid (y = 0.0023x − 0.047). To establish this standard curve, gallic acid was initially dissolved in 80% methanol at a concentration of 1 mg/mL as a stock solution, which was subsequently diluted to concentrations of 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240, and 280 µg/mL. These solutions underwent identical procedural steps as the samples, with blank preparation mirroring those of the samples but substituting the sample with the solvent (80% methanol). The resulting average absorbances were plotted against the corresponding concentrations. All assessments were conducted in triplicate and presented as mean values accompanied by standard deviations (SD).

Total flavonoid content (TFC)

Analysis of the total flavonoid contents of the crude extracts of SP and their corresponding, green-fabricated NPs were conducted via carrying out the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay30. This method relies on the reaction between flavonoids and aluminum chloride, resulting in the formation of colored, acid-stable flavonoid-aluminum complexes involving the C-4 keto group and either the C-3 or C-5 hydroxyl group of flavones and flavonols. These complexes are then quantified spectrophotometrically32. In summary, the samples were prepared by mixing them with a suitable solvent, in our case it was 80% methanol, to achieve a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Subsequently, in a test tube, 0.5 mL of the sample was mixed with 0.1 mL of 10% AlCl3, 0.1 mL of 1 M potassium acetate, and 1.5 mL of 95% methanol. The volume was then adjusted to 5 mL with distilled water and mixed well. A blank was prepared following the same procedure, with the sample being replaced by the solvent alone. Finally, the mixture was incubated for 60 min at room temperature in darkness, after which the absorbance was measured at 415 nm using a Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, which was manufactured in Agilent Technologies Ltd, Malaysia. The TFC was expressed as µg of quercetin equivalents per milligram dry weight of the tested sample (µg Qu/mg of DW) and calculated using the linear equation (y = 0.0066x + 0.0143) of the standard calibration curve of quercetin. The preparation of this standard curve involved forming different concentrations of quercetin (5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 100 µg/mL) from a stock solution (1 mg/mL). These prepared concentrations underwent the same procedure as described above, and the resulting average absorbances were plotted against their analogue concentrations. All measurements were conducted in triplicate and presented as mean values accompanied by standard deviations (SD).

Metabolic profiling of SP extracts via Q-TOF LC/MS/MS

Alcoholic and aqueous extracts of SP were subjected to a comprehensive analysis via Quadrupole time-of-flight liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (Q-TOF LC/MS/MS) to determine their phytochemical profile.

Sample preparation

A 50 mg sample of the extract was dissolved in 1 mL of the reconstitution solvent (prepared by mixing distilled water: methanol: acetonitrile, 50: 25: 25 v/v) by vortexing (2 min), sonicating (10 min), then centrifuging (10,000 rpm, 10 min). Next, 50 µl of the stock solution of the dissolved extract was subjected to dilution to 1000 µL with the reconstitution solvent. Finally, 10 µL of the 2.5 µg/µL of the prepared sample was injected, along with a 10 µl blank injection of the reconstitution solvent33,34.

Analysis and acquisition method

The constituents were separated using an ExionLC system manufactured by AB Sciex, located in California, USA. The system was equipped with a Phenomenex in-line filter disk (0.5 μm x 3.0 mm) positioned pre-column, a Waters X select HSS T3 column (2.5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm), and was coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer, the AB Sciex Triple-TOF 5600+ (CA, USA). Sciex Analyst TF 1.7.1 software (CA, USA) was used to control the LC-Triple TOF. Thorough elution of the various analytes was achieved using a gradient elution of the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.3 mL /min. For positive mode, the mobile phase was 5 mM ammonium formate buffer at pH 3 with 1% methanol (A). For negative mode, it was 5 mM ammonium formate buffer at pH 8 with 1% methanol (B). Acetonitrile (C-100%) was used in both modes. The elution protocol comprised the following stages: 0 to 21 min, 95% A or B with 5% C; 21 to 28 min, 5% A or B with 95% C; and 28.1 to 35 min, 95% A or B with 5% C. The chromatographic conditions included a 10 µL injection volume and a 40 °C column temperature. For both MS1 and MS2, TOF mass spectra were acquired across a mass range of 50.0000 to 1000.0000 Da. High-resolution TOF scanning was implemented in MS1, with Information Dependent Acquisition (IDA) being employed in MS2. The criteria for switching included exceeding 200 cps, excluding former ions after three repeats, excluding former target ions for three seconds, excluding isotopes within 2.0 Da, monitoring a maximum of 15 candidate ions per cycle, and setting the ion tolerance to 10.000 ppm. In addition, Dynamic Background Subtraction was implemented.

Data processing and analysis

Features (peaks) were extracted from the Total Ion Chromatogram (TIC) using Master View software according to specific criteria. Consistent with non-targeted analysis, features were required to have a signal-to-noise ratio greater than 10. Additionally, their intensity in the sample had to be at least three times greater than in the blank. MS-DIAL 4.9 (from the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, Japan) and PeakView (from Sciex, CA, USA) were used for data processing. For compound identification, the generated data were queried against the RIKEN tandem mass spectral “ReSpect” Databases entries (containing 1573 negative and 2737 positive records), as well as published literature and the Mass Bank database. Only identifications with a score cut-off of 70% were considered. Mass error was strictly controlled to remain below 10 ppm.

Fingerprinting and multivariate data analysis via Q-TOF LC/MS/MS data

The Metware Cloud, a free online platform (https://cloud.metwarebio.com), was used to perform Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on LC-MS/MS data obtained from alcoholic and aqueous extracts of SP. The methodology followed that described by El-Hawary et al.35. The purpose of this analysis was to ascertain the degree of separation between the extracts and their respective marker compounds, as this is expected to influence the physicochemical and biological properties of the green synthesized NPs derived from them.

Biological evaluation

Evaluation of antioxidant activity (in-vitro)

The antioxidant potential of the NPs and their corresponding crude extracts was examined through DPPH and ABTS colorimetric radical scavenging assays, employing specific methodologies36. In the DPPH assay, stock solutions of the samples were prepared in 80% methanol with a concentration of 100 µg/ mL. These solutions were then diluted to 6 different concentrations (10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 µg/mL) and mixed with DPPH with a ratio of 2:1 (v/v), then incubated in darkness at 24 °C for 40 min. The negative control involved mixing 80% methanol with DPPH, while solely 80% methanol was designated as the blank. In contrast, for each concentration of the tested NPs, a sample blank was prepared by dispersing the sample in 80% methanol due to their tendency to disperse in the solvent and their limited solubility. Following this, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured using a Hidex Sense UV microplate reader (Hidex, Turku, Finland).

The radical scavenging % of the samples was calculated utilizing the following formula:

where Ab is the negative control absorbance and A is the sample absorbance. IC50 (µg/mL) values were calculated by generating a calibration curve within the linear range for each sample tested, by plotting sample concentration against the corresponding % of radical scavenging. The IC50 represents the concentration required for the samples to decrease DPPH absorption by 50%, indicating higher antioxidant activity with lower IC50 values. In the ABTS radical scavenging assay, 100 µg/mL stock solutions of the samples were prepared in 80% methanol. These stock solutions were then used to prepare concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL for testing. To generate the ABTS+• radical cation, 7 mM of ABTS was mixed with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio and incubated in darkness for 12–16 h. The resulting mixture was diluted with methyl alcohol until reaching an absorbance value of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Aliquots of 100 µL of each sample concentration solution were combined with 100 µL of diluted ABTS+• in a 96-well plate. The resulting mixtures were subsequently incubated for a period of 10 min in darkness at ambient temperature. The absorbance of the samples was then determined at a wavelength of 734 nm using a Hidex Sense UV microplate reader (Hidex, Turku, Finland). Methanol 80% with ABTS+• was employed as the negative control, while solely 80% methanol served as the blank. Because the tested NPs exhibited low solubility and achieved uniform dispersion in 80% methanol, a sample blank consisting of the sample dispersed in this solvent was prepared for each concentration. The percentage radical scavenging activity was calculated through the following formula:

where Ac is the negative control absorbance, and A is the sample absorbance. Employing a calibration curve within the linear range, the IC50 (µg/mL) values were derived by plotting extract concentrations against their associated percentages of radical scavenging. Analogous to DPPH assays, a higher IC50 value denotes diminished antioxidant activity, indicating the concentration required by the sample to reduce ABTS absorption by 50%. All analyses were performed in triplicate and reported as mean ± standard error (SE).

Investigation of skin anticancer activity (in-vitro)

Cell culture

A-431 human epidermoid skin carcinoma (skin/epidermis) cell lines were sourced from Nawah Scientific Inc., headquartered in Mokatam, Cairo, Egypt. DMEM media, supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 units/mL penicillin, was used to propagate the cell lines. The routine upkeep of these cell lines was executed within a controlled atmosphere, featuring 5% (v/v) CO2 humidity at 37 °C.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cell viability was evaluated via the Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. In 96-well plates, 100 µL of cell suspension (5 × 103 cells) was plated and incubated in complete media for 24 h. Following incubation, cells were exposed to varying drug concentrations by treating them with another 100 µL of media containing the drug. Cells were fixed with 150 µL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at 4 °C for 1 h after 72 h of drug exposure. Upon TCA removal, cells underwent five washes with distilled water. Plates were incubated with 70 µL of 0.4% w/v SRB in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Following the incubation, three washes with 1% acetic acid were performed on the plates, which were then left to air-dry overnight. In the final step, the protein-bound SRB stain was dissolved with 150 µL of 10 mM TRIS, and then the absorbance was measured at 540 nm via a BMG LABTECH®- FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (Ortenberg, Germany)37,38.

Statistical analysis

All the results were expressed as mean ± standard error/standard deviation of the mean (SEM/SDM). The radical scavenging percentage and cell viability were determined in triplicate for antioxidant and cytotoxic activities, respectively. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for antioxidant and cytotoxic activities, to determine the significance of difference among the studied groups. The statistical analyses were tested at P < 0.05 using the GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

Results and discussion

Characterization of the nanoparticles

We have incorporated significant adjustments into the synthesis protocols, specifically conducting the synthesis reactions at temperatures below 60 °C and opting for air drying instead of using high-temperature oven drying. These modifications aim to safeguard against the decomposition of bioactive constituents of the extracts, which serve as coatings for the metal NPs27. As was previously mentioned, the bioactive metabolites present in the plant extract play crucial roles as effective reducing, stabilizing, and capping agents throughout NP synthesis. They expedite the reduction of metal precursors and contribute to coating that not only improves the stability but also enhances the biological activity of the ultimately formed NPs. It merits acknowledgment that the incorporation of two distinct extract types is intended to scrutinize the impact of extraction methodologies on both the physiochemical and biological properties of the synthesized green NPs. The objective is to optimize the quality and efficacy of the NPs, recognizing that various extraction solvents selectively extract diverse active constituents24. As presented in figure S1 in supplementary file, the resultant NPs derived from SP manifest divergent physical attributes. Consequently, a range of methodologies was employed to scrutinize their physicochemical properties. SZnC and SFeC denote the zinc and iron oxides NPs synthesized utilizing the alcoholic extract, respectively, whereas SZnQ and SFeQ represent the zinc and iron oxides NPs synthesized employing the aqueous extract, respectively.

UV visible spectrophotometer

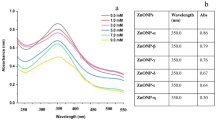

By studying the absorption spectra collected from the UV-VIS spectral analysis of the samples understudy, formation of zinc and iron oxides NPs was confirmed. Zinc oxide NPs normally show a broad peak in the UV-VIS spectrum in the range of 230–330 nm. The optical transition observed at 270 nm for the aqueous extract-based NPs corresponds to the formation of zinc oxide NPs. As for alcoholic extract-based NPs, it was 275 nm. Furthermore, iron oxide NPs normally show a broad peak in the UV-VIS spectrum in the range of 220–288 nm. For the aqueous extract-based NPs, it was observed at 270 nm, whereas, for the alcoholic extract-based NPs, it was found at 275 nm (Figure S2 in supplementary file). The results showed promise for the process of nanoparticle synthesis through confirming the surface plasmon resonance of the formed plant-based metal NPs25. The calculated band gap values for SZnC and SZnQ were 3.76 eV and 3.69 eV, respectively (Figure S3 in supplementary file), which are within the reported ranges in the literature. The reported band gap energies for ZnO are ranging between ~ 2.88 eV and 4.7211,16,29. For SFeC and SFeQ, they give direct-like optical transitions at 2.82 eV and 2.86 eV, respectively, from the direct-Tauc plot. These values are in good consistency with those reported in the literature39. However, the reported fundamental indirect gap (~ 2.0–2.25 eV) (Figure S4 in supplementary file)40,41.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX)

SEM was utilized to visualize the surface morphology and agglomeration state of the NPs understudy. The images exhibit a fluffy (SFeC and SZnC) to medium rough (SFeQ and SZnQ), irregular-like surface, indicating a higher propensity for agglomeration in SFeC and SZnC compared to NPs prepared using aqueous extracts (Fig. 2a). This may be attributed to differences in the phytochemical content between the aqueous and hydroalcoholic extracts, and consequently in their respective capping molecules. This will be further confirmed later in this study through Q-TOF LC/MS/MS-based multivariate analysis. These findings suggests that aqueous extracts may be more effective in stabilizing Fe2O3 and ZnO NPs than their alcoholic counterparts. Previous studies have consistently reported a heightened tendency for agglomeration in green-synthesized NPs in general due to the adhesive nature of the plant extracts employed25. Notably, SFeQ NPs exhibited superior uniformity, dispersion, and homogeneity compared to other formed NPs.

(a) SEM images of the zinc oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles prepared with aqueous and 80% ethanolic SP extracts, (b) elemental composition of the SP-derived nanoparticles by EDX, and (c) spatial distribution of elements in SP-derived nanoparticles, and (d) XRD patterns of S. persica-based Fe2O3 and ZnO NPs.

EDX analysis was conducted to verify the formation of Fe2O3 and ZnO NPs and explore the elemental composition of their coating. The recorded peaks of iron and zinc confirm the presence of Fe and Zn NPs. Results indicate that the average weight percentages of iron in the analyzed samples were 17.45% and 19.23% for SFeC and SFeQ NPs, respectively, while 42.61% and 56.38% in SZnC and SZnQ NPs, respectively. Peaks for oxygen and carbon were observed between 0.1 and 0.5 KeV, with weight percentages of 27.05, 19.81, 10.07, and 22.61 for oxygen and 47.13, 30.28, 42.61, and 18.66 for carbon in SFeC, SFeQ, SZnC, and SZnQ NPs, respectively. Other elements like nitrogen and sulfur are attributed to the phytochemicals of the plant that cap the NPs (Figs. 2b and c). The results indicate higher percentages of Fe and Zn in aqueous-based NPs than alcoholic-based ones, suggesting that aqueous extract may serve as a stronger reducing agent. Conversely, the percentage of carbon is higher in alcoholic-based NPs than in aqueous-mediated ones, suggesting that phytochemicals from alcoholic extract provide a more effective coating for the NPs.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

An X-ray powder diffractometer, set to Bragg’s angles between 10° and 80°, was used to analyze the crystalline structure, nature, and phase diffraction of the fabricated NPs. The resulted X-ray diffraction patterns of the SP-mediated NPs revealed that most of the formed nanoparticles are amorphous with a poor crystalline structure, exhibiting 2θ broad weak peaks at 21.532°, 21.588°, and 21.83°, which may correspond to the crystalline cellulose naturally present in the plant extracts coating the NPs42,43,44. However, SZnQ was an exception, exhibiting stronger diffraction peaks; thus, stronger crystallinity (Fig. 2d). The major diffraction peaks for SZnQ were found at 31.068°, and 33.325°, 35.884, and 47.757, corresponding to miller indices of (100), (002), (101), and (102), agreeing partially with the hexagonal geometry of zinc oxide nanoparticles as previously mentioned in JCPDS no. 36-145145. We mentioned here “partial agreement” because we did not perform any type of calcination for the NPs in order to maintain the optimum efficacy of all the phytochemicals that are coating the NPs, especially the thermosensitive phytoconstituents. Some shifts were observed in some peaks due to the effect of the plant extract that coats the surface of the NPs. Other major peaks at 11.579°, 20.695°, 29.072° were observed, and they are assumed to be related to the associated plant matrix with the NPs44,45,46,47.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The diameter of the bio-fabricated NPs, their zeta potential values, and polydispersity indices were analyzed at ambient temperature, using Malvern Zetasizer DLS, while dispersed in ethanol. Zeta potential significance comes from its reflection of the particles’ stability, through measuring the repulsion between nearby particles carrying similar charges and, consequently, correlating this with the stability of colloidal dispersions. Enhanced stability of the particles could be concluded by getting higher zeta potential value. Regarding the polydispersity index, it plays a crucial role in measuring the homogeneity of particle sizes in a sample, as elevated values indicate greater variability among particles48. The resulting data is presented in Table 1, and graphs illustrating particle size and zeta potential distribution for all tested samples are presented in Fig. 3a and b. According to the demonstrated values, SZnC exhibited the smallest particle size (58.49 nm), followed by SFeC with mean particle size of 105.7 nm. Conversely, SFeC exhibit the highest surface stability (18 mV) followed by SZnC (15.1 mV). A previous study reported the bio-fabrication of silver NPs using the aqueous extract of SP, which exhibited a zeta potential of 1.4 mV49. In contrast, higher stabilized gold NPs (− 28.7 mV) and copper NPs (− 25.2 mV) were synthesized via SP 50% ethanolic fruit extract12. These studies suggest that the phytochemical constituents of the utilized extracts likely contribute to the surface charge of the resulting nanoparticles, and consequently, to their stability. Based on this, it is evident that the value and charge of the zeta potential of the plant-based fabricated NPs vary depending on the type of the used plant extract (e.g., aqueous, alcoholic, hydroalcoholic, etc.), plant organ (e.g., leaves, fruits, aerial parts, etc.) and the core metal (e.g., zinc, iron, gold, etc.). It could be concluded from the results that NPs based on the alcoholic extract outperform those derived from the aqueous one in terms of particle size and stability because they displayed smaller particle size and higher potential. Furthermore, all the SP-mediated NPs exhibit positive surface charges and show monodispersity.

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

FT-IR analysis was performed to deduce the functional groups of the phytochemical molecules that are linked with the synthesis and coating of the NPs. The bands in the FT-IR results at 3371.15–3536.28 cm− 1 correspond to the O-H functional group stretching corresponding to carboxyl acid and alcoholic hydroxyl groups. The bands that correspond to the aliphatic C-H functional group were found in the range between 2644.99 cm− 1 and 2926.01 cm− 1. In addition, the bands found between 2087.41 and 2396.93 cm− 1 represent the C ≡ C and C ≡ N vibrations. The peaks seen from 1507.57 to 1861.03 cm− 1 represent the functional group C = C and C = O. The functional group NO2 was observed in the range from 1328.34 to 1464.8 cm− 1. In addition, bands that are shown within the range of 1035.66–1273.34 cm− 1 represent C-O functional group. The aromatic rings, C-halogens, and metal oxides bands were determined between 404.48 and 916.77 cm− 1 (Fig. 3c)50. Consequently, the FTIR spectra of the examined samples indicate the presence of alcoholic, phenolic, carbonyls, alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, alkyl halides, nitro, and aromatic functional groups. This observation can be linked to the existence of various phytochemical classes, like phenolics, flavonoids, amino acids, fatty acids, and terpenoids in the samples. This affirmation solidifies the effective encapsulation of the NPs with the chemical constituents derived from the plants. In line with the outcomes of this analysis, the FT-IR spectra of the SP extracts and their corresponding NPs closely resemble each other, providing validation for the successful green synthesis of plant-based iron and zinc oxides NPs as proposed in this study. However, it is observed that there is a compression or expansion of the intensity of some bands of the investigated NPs when compared to their parent extracts. We assume that this is due to the involvement of the extracts’ phytochemical compounds that possess these functional groups in the reduction reactions of the metal precursor, leading to its depletion or formation of other derived organic compounds. These results are in agreement with previous reports51.

Chemical investigation

Total phenolic and flavonoid content

The results of the phenolic and flavonoid contents’ investigation of the plant under scrutiny and its associated green NPs were presented in Table 2 and discussed in supplementary file S1.

Metabolic profiling of the extracts via Q-TOF LC/MS/MS

The phytochemical composition of alcoholic and aqueous extracts of SP was thoroughly characterized using Q-TOF LC/MS/MS. The total intensity and base peak chromatograms demonstrated successful metabolite elution in both positive and negative ionization modes (Figures S5-S12 in supplementary file). Tentatively, 72 phytochemicals were identified in negative mode and 64 in positive mode. Most of these metabolites belong to several phytochemical classes, including phenolics (51), amino acids (18), and fatty acids (5), along with other miscellaneous classes. Tables 3 and 4 provide a comprehensive overview of the identified compounds, including their retention times and fragmentation patterns. The data indicate that phenolics compounds constituted the largest portion of identified metabolites, with significant proportions observed in both negative (29 out of a total of 72 compounds) and positive (22 out of a total of 64 compounds) ionization modes. Within these identified phenolics, 39 compounds were detected in the SC, and 35 in the SQ. Twenty-three of them were detected in both extracts, while 16 compounds were exclusively annotated in SC only. Furthermore, zearalenone, quercetin-3-D-xyloside, quercetin-3-O-arabinoglucoside, delphinidin-3-O-beta-glucopyranoside, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, sinapyl aldehyde, cinnamate, peonidin-3,5-O, di-beta-glucopyranoside, malvidin-3, 5-di-O-glucoside chloride, hyperoside, phlorizin, and rhamnetin were solely determined in SQ. The results indicate a clear preference for negative ionization in the detection of phenolic compounds. This observed trend is consistent with previous established understanding that the inherent chemical properties of phenolic compounds, specifically their weak acidity and high pKa values, facilitate their preferential ionization under negative electrospray ionization (ESI) conditions52,53.

Identification of phenolic acids

Phenolics constitute the predominant class in the studied extracts of S. persica. Mass spectral data of the identified phenolic acids revealed significant fragmentation patterns, characterized by losses of 44 amu (CO2) in negative ion mode, 45 amu (COOH) in positive ion mode, 18 amu (H2O), and 31 amu (methoxy). Peaks 34 and 37 at m/z 137.0236 and 146.9611 [M-H]-, annotated as P-Hydroxybenzoic acid and Cinnamate, displayed distinguished fragments at m/z 93.03539 and 102.97254 due to the loss of CO2 [M-H-44]-, respectively. Peak 35 at m/z 359.1006 [M-H]- exhibited a fragment at m/z 340.86834 due to the loss of water moiety [M-H-18]-, thus identified as Rosmarinic acid. Peak 31 at m/z 163.0388 which was assigned as 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic acid, demonstrated the loss of both CO2 and water moieties, giving fragments at fragments at m/z 119.05016 and 144.9458, respectively.

Based on its molecular ion at m/z 385.1144 (C17H22O10)- and MS2 fragmentation patterns, peak 38 was tentatively identified as 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl sinapate, with fragment ions at m/z 91.05561 indicative of hexose, CO2, C2H4, and two methoxy moieties’ losses [M + H-162-44-28-62]+. In the positive mode, a major fragment at m/z 73.06343 was noted in peak 18 at m/z 149.0199 (C9H8O2)+ due to the loss of CH3O and COOH [M + H-31-45]+. This peak was recognized as Cinnamate. Moving to peak 51 at m/z 225.1379 [M + H]+, it produced a distinct fragment at m/z 130.06576 due to a combination loss of carboxylic acid, water, methoxy and hydrogen moieties [M + H-45-18-31-1]+. Therefore, it was named as 3-(4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-propenoic acid or Sinapinic acid.

Identification of other phenolics

Forty-four phenolic compounds, belonging to flavonoids, stilbenes, zearalenones, xanthines, and methoxyphenols, were detected in the extracts understudy. Twenty-four of them were identified in the negative ionization mode. Losses corresponding to water (18 amu.), methyl (15 amu.), and methoxy (31 amu.) groups confirmed the presence of hydroxyl, methyl, and methoxy functionalities in the phenolic aglycones. An eminent example, in the negative mode, is peak 9 (m/z 283.0477, C16H12O5−) which showed a major fragment at m/z 195.03427 amu due to the loss of two water molecules, one methyl, and one methoxy group, in addition to 6 hydrogen atoms [M-H-36-15-31-6]−. This peak was assigned as the O-methylated flavone; acacetin. Also, myricetin was detected in peak 25 (m/z 317.0533, C15H10O8−), where a distinguished fragment at m/z 241.00246 was produced due to the loss of four water molecules and 4 hydrogen atoms. For the glycosides, the fragmentation patterns in the generated data consistently demonstrated the loss of rhamnosyl (146 amu.), pentosyl (132 amu.), and hexosyl (162 amu.) moieties, suggesting the presence of these sugar units in the identified flavonoid glycosides. In peak 43 (m/z 595.1276, C26H28O16−), the generated fragments at m/z 445.06913, and m/z 271.02147 indicates the losses of pentose and H2O for the first fragment, and quercetin (-302 amu), H2O and 4 hydrogen atoms for the second fragment. Thus, this peak was annotated as quercetin-3-O-arabinoglucoside. Another example is peak 44 (m/z 739.2104, C33H40O19−), which was assigned as kaempferol-3-O-robinoside-7-O-rhamnoside as its fragmentation patterns showed a loss of rhamnose deoxy sugar at m/z 593.14732, and other losses of rhamnose and water at m/z 575.14933, in addition to a special fragment at m/z 285.03109:599 due to the loss of 2 units of rhamnose and one hexose. Peaks 45 (m/z 609.1442, C27H31O16−) and 47 (m/z 609.1456, C28H34O15−) demonstrate mutual fragment peaks at m/z 301.02639 and 301.03645, respectively, due to the loss of rhamnose and hexose units. So, they were identified as delphinidin-3-O-(6’’-O-alpha-rhamnopyranosyl-beta-glucopyranoside and hesperidin, respectively. Likewise, peaks 49 (m/z 463.1314, C21H20O12−), 50 (m/z 463.0895, C21H21O12−), and 51 (m/z 463.089, C21H20O12−) produced fragments at m/z 301.04119, m/z 301.032, and m/z 301.03133, due to the loss of hexose unit, respectively. Therefore, these fragments were recognized as Quercetin-4’-glucoside, delphinidin-3-O-beta-glucopyranoside, and hyperoside. Furthermore, losses of coumaroyl and hexose sugar units were detected at m/z 285.03341:476 fragment of peak 52 (m/z 593.1475, C30H26O13−), in addition to another common fragment at m/z 255.01969 corresponding to the loss of coumaroyl (-146 amu), hexose (-162 amu), and C2H6 units. This peak was named as kaempferol-3-O-(6-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside.

In the positive mode, the same losses were observed. A stilbene resveratrol was detected in peak 15 at m/z 229.1541, C14H12O3+, as the loss of three water molecules and five hydrogen atoms led to the generation of a predominant fragment at m/z 170.08351. Also, peaks 30 at m/z 625.2059 (C28H33O16) + and 33 at m/z 433.1488 (C21H20O10) + showed distinct fragments at m/z 463.1607, and m/z 271.12228 due to the loss of hexosyl sugar unit [M + H-162] +, respectively. These peaks were named as peonidin-3,5-O-di-beta-glucopyranoside and apigenin-7-O-glucoside, respectively. The fragmentation patterns of several detected flavonoid aglycones revealed cleavages within rings A, B, or C. For example, quercetin was indicated in peak 42 at m/z 303.0504, C15H10O7+, as it displayed distinct fragmentation peaks at m/z 153.02337 [M + H-benzene-4H2O2]+ and 137.02676 [M + H-benzene-4H2O2-CH4]+ due to cleavage of ring b, beside other fragments resulted from water loss at m/z 285.05759 [M + H-H2O2]+ and 229.05472:586 [M + H-4H2O2-2 H]+.

Identification of amino acids

Amino acids represent the second most abundant class of compounds identified in the analyzed extracts, with 18 phytometabolites detected in the alcoholic extract and 11 in the aqueous extract. In the negative mode, mutual losses of CO2 (-44 amu), CO (-28 amu), NH (-15 amu), and H2O (-18 amu) units were observed. Peaks 5 (m/z 146.0449, C5H9NO4−), 23 (m/z 116.0713, C5H11NO2−), and 65 (m/z 144.0462, C7H15NO2−) showed fragments at m/z 102.06028, m/z 72.00127, and m/z 100.95884 due to the loss of COO, respectively. Other fragments were produced by peaks 5 and 65 at m/z 128.03703, and m/z 126.03607 due to loss of a water molecule, respectively. Also, a loss of CO was recorded in the fragmentation pattern of peak 65 at m/z 116.05509 [M-H-CO] −. Peaks 5, 23, and 65 were annotated as glutamic acid, norvaline, and homoisoleucine, respectively. Peak 30 at m/z 128.0354, C5H7NO3−, exhibited distinct fragmentation patterns at m/z 94.97976 [M-H-NH-H2O]− and m/z 68.99817 [M-H-COO-NH]−, so it was tentatively identified as 5-Oxoproline. The same losses were recorded in the positive mode except for the COO loss as it was recorded as COOH (− 45 amu). Tyrosine in peak 6 at m/z 182.0776, C9H11NO3+, displayed main fragments at m/z 110.06071 [M + H-H2O-COOH-9 H] +, 88.07796 [M + H-H2O-COOH-NH2-CH3] +, 58.06561 [M + H-H2O-COOH-NH2-C3H9] +. Also, peak 40 at m/z 194.1166 (C10H11NO3+), which was recognized as phenaturic acid, yielded a distinctive fragment at m/z 91.05798 [M + H-COOH-CO-NH-CH3]+.

Fingerprinting and multivariate data analysis via Q-TOF LC/MS/MS data

We employed untargeted multivariate data analysis to thoroughly examine the metabolic heterogeneity observed in SC and SQ extracts. Though visual inspection of Q-TOF LC/MS/MS findings reveals the separations between the extracts, PCA affords a more rigorous and comprehensive qualitative and quantitative insights into their similarities, dissimilarities, and key marker compounds, especially considering their complex metabolite profiles. The OPLS-DA model demonstrated excellent stability and reliability, as confirmed by the permutation testing and model validation plotted in Figs. 4a, b, which yielded R2Y value of 0.982, R2X value of 0.999, and Q2 = 0.936 with a statistically significant P-value of less than 0.005, confirming an optimal model. Two orthogonal principal components (PCs) visualized the PCA findings of the Q-TOF LC/MS/MS dataset for the tested extracts as shown in the PCA score plot in Fig. 4c. PC1, which accounted for 32.1% of the total variance, delineated the degree of separation between the two extracts, while PC2 explained 58.9% of the variance, illustrating the amount of variability within each texted extract. Along the PC1 axis of the score plot, SQ sample exhibited positive scores, placing it on the right, while SC sample displayed negative scores, clustering on the left, indicating a clear separation between them. Figure 4d, showing the OPLS-DA S-plot, revealed a distinct separation between SC and SQ extracts, although some overlap was observed. This separation was characterized by 26 SQ-specific and 39 SC-specific phytochemical markers. The predominant marker compounds in SQ are rhamnetin, maltotriose, tartrate, 2’-deoxyadenosine, and isoguvacine, while the major ones in SC are N, N-dimethylglycine, 4-aminophenol, hydroxybutyric acid, 3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine, and hesperidin.

Multivariate data analysis of the Q-TOF LC/MS/MS metabolomic data from SC and SQ samples using PCA and OPLS-DA (n = 2). (a) OPLS-DA permutation test plot, (b) OPLS-DA model validation plot, (c) OPLS-DA score plot of PC1 vs. PC2 scores, (d) OPLS-DA S-plot, illustrating the covariance p[1] against correlation p(corr)[1] of discriminating variables between alcoholic and aqueous extracts of S. persica.

Biological evaluation

Evaluation of antioxidant activity (in-vitro)

The in-vitro ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays represent commonly utilized techniques for evaluating the radical scavenging abilities or antioxidative impacts of natural product extracts and their derived NPs against ABTS and DPPH radicals, which present as harmful and foreign entities within our biological framework. These analytical approaches, reliant on spectrophotometry, pivot upon the diminution of the stable colored ABTS•+ and DPPH radicals54. The core tenet of the ABTS assay lies in the generation of a bluish-green radical ABTS·+ that undergoes subsequent reduction by antioxidant agents, yielding colorless ABTS; conversely, the DPPH assay involves the reduction of the purple DPPH·+ to colorless DPPH55. A notable distinction between these methodologies lies in the predilection of ABTS radicals for reaction via the Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer (SPLET) mechanism in aqueous environments, while DPPH radicals engage in SPLET-mediated reactions in solvents such as ethanol and methanol56. Thus, we have employed both assays to ascertain the antioxidative potential of the phyto-fabricated green NPs and their corresponding extracts. The resultant data is illustrated as radical scavenging percentages wherein heightened values denote increased antioxidant efficacy (Fig. 5a and b). Additionally, these results are represented as IC50 values (Table 5), representing the concentration at which 50% scavenging of radicals is achieved by the tested sample. Lower IC50 values imply superior antioxidant potency within the examined sample. It is worth mentioning that SZnC displayed the strongest radical scavenging effect among the tested samples against both sorts of radicals (IC50 180.26 and 69.68 µg/mL against DPPH·+ and ABTS·+, respectively). Also, our findings unveil significant antioxidant activity across all tested samples, attributable to the dose-dependent scavenging of DPPH and ABTS free radicals. Notably, the SP-based ZnO NPs exhibits the most prominent antioxidant effect against DPPH and ABTS radicals across all tested concentrations, showcasing IC50 values ranging between 69.68 and 189.26 µg/mL and radical scavenging percentiles from 25.94% to 69.99% at 100 µg/mL. On the other hand, SC and SFeC demonstrated the weakest scavenging effect against DPPH·+ and ABTS·+, respectively.

(a) In-vitro antioxidant activity of SP extracts and their corresponding bio-fabricated nanoparticles against DPPH radicals, (b) ABTS assay. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) from three independent experiments (n = 3). (c) Anticancer activity of SP extracts and their Fe and Zn nanoparticle formulations against A-431 human epidermoid skin carcinoma cells. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with three replicates per group. (d) Microscopic assessment of the morphological changes in A-431 cells treated with SP extracts and their Fe2O3 and ZnO NPs for 72 h, (A) 0.1 µg/ml, (B) 10 µg/ml, (C) 1000 µg/ml.

These findings were further supported by the results from the one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests of both assays, which demonstrate a clear and progressive dose-response relationship for the tested samples. At the lowest concentrations, some treatments show a significant effect, but the magnitude and number of significant comparisons increase with increasing concentration. In ABTS assay, at a concentration of 10 µg/ml, SC and SFeC were not significantly different from the control (Adjusted P values of 0.9947 and 0.4414, respectively). However, the other tested samples showed a highly significant difference from the control at P < 0.05. This indicates that even at a relatively low concentration, some of the treatments have a potent effect. As the concentration was increased to 20 µg/ml, the number of significant comparisons grew, while the SC treatment remained insignificant (P = 0.9443). This trend continued at the higher concentrations of 40, 60, and 80 µg/ml, where all treatments consistently showed a highly significant difference from the control group, with adjusted P values of < 0.0001. The data clearly show that SQ, SZnC, SZnQ, and SFeQ are particularly potent, exerting a strong effect against ABTS radicals even at low concentrations, while treatments like SC and SFeC require higher concentrations to demonstrate a significant difference from the control (Tables S1 in supplementary file). For DPPH assay, the effect becomes more significant and widespread across the examined samples as the concentration increases from 20 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL. Only SC showed significant difference at the concentration of 10 µg/mL (P < 0.0302). At a concentration of 20 µg/mL the substances SC, SQ, and SZnC showed a statistically significant difference from the control group, with adjusted P-values of 0.0077, 0.0310, and 0.0025, respectively. At a concentration of 60 µg/mL, the effect becomes more pronounced. All substances, except SFeQ (P = 0.1080), showed a statistically significant difference from the control group, with P-values of 0.0412 for SC, < 0.0017 for SQ, < 0.0001 for SZnC, 0.0068 for SFeC, and < 0.0001 for SCZnQ. This trend of increasing significance culminates at 80 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL, where all the samples showed highly significant differences from the control group (Tables S2 in supplementary file).

These high radical scavenging effects could be linked to the samples’ high content of phenolics, and flavonoids as revealed from the findings of Q-TOF LC/MS/MS, TPC, and TFC, especially that it is widely acknowledged that phenolics and flavonoids are powerful phytochemicals with strong antioxidant capabilities57. Our QTOF-LC/MS-MS findings indicated that approximately 37.5% of the detected compounds in the extracts were categorized as phenolic phytochemicals, with 39 compounds detected in the SC extract and 35 in the SQ extract. These findings align with prior established studies36. This implies that the phenolic and flavonoid compounds in the extracts likely function as superior capping and coating agents during nanoparticle synthesis, leading to enhanced antioxidant activity against ABTS and DPPH free radicals.

Investigation of skin anticancer activity (in-vitro)

The exploration focused on assessing the anticancer efficacy of the green-fabricated NPs and their corresponding crude extracts against A-431 human epidermoid skin carcinoma via the sulforhodamine B (SRB) screening assay. This assay, widely employed for evaluating cytotoxicity in cell-based investigations, relies on the measurement of cell density through the quantification of cellular protein content. A key aspect of this technique is the interaction of SRB, a xanthene dye, with basic amino acid residues (proteins) under slightly acidic conditions, reversible upon exposure to basic treatment conditions. Thus, quantifying the amount of bound SRB to cells via colorimetric analysis functions as an indicator of cell density and, consequently, cell proliferation37. The results are represented as the percentage of cell viability for cancer cells and IC50 values, as illustrated in the Fig. 5c. Furthermore, Fig. 5d portrays the morphological changes in cancer cells following exposure to different concentrations of the tested samples. The results indicate that all the tested samples were active against the tested cancer cells except the Fe2O3 NPs (SFeQ and SFeC) which showed inactivity. The findings emphasize the most robust effectiveness of SP aqueous extract based ZnO NPs against the targeted cell lines compared to its parent aqueous crude extract, followed by the alcoholic crude extract demonstrating a noteworthy decrease in cancer cell viability after 72 h of exposure, 18.77% and 12.11% at 1000 µg/mL, with IC50 values of 377.39 µg/mL and 396.30 µg/mL, respectively. This efficacy was further validated through microscopic examination of treated cells, revealing substantial alterations in cancer cell morphology such as detachment and shrinkage, particularly at higher concentrations (Fig. 5d). The conducted one-way ANOVA statistical analyses demonstrate that both group and concentration effects among each group of the tested samples were highly significant (P < 0.05). The Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (vs. control) shows that all the tested samples demonstrated significant difference from the control at 1000 µg/mL (p < 0.05), indicating that the cell viability of the tested cells dropped sharply at high concentrations. However, only SZnQ and SC displayed significance at 100 µg/mL. At lower concentrations, only 1 µg/mL SZnQ, 1 µg/mL SFeQ, and 10 µg/mL SC displayed significant difference, suggesting a dose-dependent response. The results of the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test show a concentration-dependent effect of the various treatments. At the lowest concentration (0.1), none of the comparisons to the control group were statistically significant, with all adjusted P values being greater than 0.05. This suggests that at very low concentrations, the treatments had no discernible effect on the measured variable. However, as the concentration increased, significant differences began to emerge. At a concentration of 100, the SZnQ showed a highly significant difference compared to the control group and all the tested samples, with P values of less than 0.05. This trend became even more pronounced at the highest concentration of 1000 µg/mL. At this concentration, nearly all treatments showed a statistically significant effect when compared to the control and each other with a notable exception of SZnQ vs. SC, SZnC vs. SQ and SC, and SQ vs. SC. This strong dose-response relationship suggests that the inhibitory or stimulatory effects of these products are only evident at higher concentrations. The findings indicate that for many of the treatments, their biological effect is not apparent until a certain threshold concentration is reached (Table S3 in supplementary file).

These findings are in agreement with previous studies11. Recently, zinc oxide NPs fabricated using the aerial parts of UAE-wild Calotropis procera and Leptadenia pyrotechnica exhibited significant anticancer activity against A-431 human epidermoid skin carcinoma, achieving IC50s down to 188.97 µg/mL. The study suggests that this therapeutic potential is likely attributed to the combined action of the zinc metal core of the NPs, as well as their phenolic and flavonoid surface coatings15,58. More in-depth study conducted on Lawsonia inermis revealed that the extract type significantly influences the anticancer effect of its corresponding ZnO NPs, suggesting that the phenolic and flavonoid composition of them, both qualitative and quantitative, plays a key role in their anticancer potential alongside the intrinsic properties of the NPs’ metal core36. Therefore, we propose that the enhanced potency of our SP-mediated ZnO NPs results from the combined and synergistic action of their zinc core and the SP-derived phenolic phytochemicals coating the NPs. Multiple studies support this by highlighting the anticancer properties of ZnO NPs, and phenolics, including SP-derived phenolics, which collectively target cancer cells through diverse molecular pathways19,21,59. The proposed mechanism for ZnO NPs’ cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in cancer cells centers on that the acidic tumor microenvironment facilitates the release of soluble zinc ions from ZnO NPs, initiating their cytotoxic and genotoxic effects. This triggers multiple cytotoxic pathways, primarily through zinc-mediated protein disruption, leading to DNA damage, oxidative stress, and apoptosis, among other cellular dysfunctions like disturbance of cellular homeostasis, electron transport chain and membrane permeability60,61. Furthermore, the high concentration of the released zinc ions, coupled with the inherent redox properties of ZnO NPs and the tumor’s inflammatory response towards the NPs, leads to significant ROS generation, contributing to cancer cell death62. Accumulation of ROS, strong oxidizing agents, in tumor cells leads to disruption of cellular redox homeostasis balance and mitochondrial function, causing oxidative stress. This stress damages cellular components via lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and nucleic acids damage, leading to DNA damage, and ultimately triggering cell death via both necrotic and apoptotic pathways11,63.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the potent anticancer activity of SP extracts, with a focus on their phenolic phytochemicals, particularly against skin cancer19,20,21. The isolated xanthotoxin and umbelliferone phytochemicals from 90% ethanolic extract of SP stems displayed a regression response in vivo towards the growth of tumors of murine mouse melanoma. The authors of this study attributed this regression effect to the antioxidant properties of the isolated compounds as a possible pathway21. Further in-depth study revealed the ability of SP root extract to inhibit hepatocarcinoma cells through inhibition of tumor angiogenesis via modulating essential angiogenic makers and regulators like Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its associated intracellular key signaling molecules. This causes cessation of blood supply to the cancer cells, starving them of nutrients and ultimately, cellular death20. The predominance of phenolics and amino acids in the tested extracts, as confirmed by our QTOF-LC/MS/MS and multivariate analysis findings, directly supports the critical role of these compounds in mediating the observed anticancer activity of the extracts and their NPs. Recognized for their anticancer properties, phenolic compounds function through multifaceted pathways, including inducing apoptosis, promoting differentiation, and modulating inflammation, angiogenesis, and metastasis. These actions are partly mediated by their ability to regulate cellular redox balance under oxidative stress64,65. For instance, quercetin, apigenin, and resveratrol, among other phenolic compounds, induce apoptosis to inhibit carcinogenesis via extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by cell surface receptor activation, like TNF-α, activating caspase-8. The intrinsic pathway is regulated by mitochondrial internal cell signaling, involving various mitochondrial proteins like inhibitor of small mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (SMACs), apoptosis proteins (IAPs), and B-cell lymphoma-2 protein (Bcl-2), along with mitochondrial membrane integrity and polarity64,66.

Given that amino acids are the second most predominant class in our tested samples, as revealed by QTOF-LC/MS/MS analysis, they may significantly contribute to the samples’ effectiveness. Notably, amino acids play a crucial role in targeting cancer cells, as their metabolic intermediates can influence both tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic processes. For example, through the citrulline-NO pathway, arginine metabolism produces nitric oxide (NO), which exhibits a context-dependent role and contradictory effects in oncogenesis, through either promoting angiogenesis and thus tumor growth, or acting as a tumor suppressor by upregulating p5367. Beyond their composition, the nanoscale dimensions of the synthesized NPs act synergistically to boost their therapeutic efficacy by facilitating cellular internalization, improving systemic bioavailability, and optimizing intracellular distribution, thereby potentiating their utility in targeted drug delivery applications5.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that aqueous and 80% ethanolic extracts of SP successfully facilitated the environmentally friendly synthesis of Fe2O3 and ZnO NPs by multifunctioning as reducing, capping, coating, and stabilizing agents effectively, highlighting their potential in biomedical contexts. SEM and EDX analyses revealed that the alcoholic extract of SP produced ZnO and Fe2O3 NPs with a richer carbon surface coating than the aqueous extract. Consistent with this, TPC and TFC data showed a higher phenolic and flavonoid content in NPs synthesized with the alcoholic extract compared to their aqueous extract derived analogues. Consequently, owing to this effective coating, the SZnC NPs exhibited the strongest antioxidant activity against DPPH and ABTS radicals. FT-IR analysis revealed the successful coating of the NPs with phytochemicals, as evidenced by characteristic functional group bands. Observed intensity variations and band absences in the NPs’ samples, relative to the parent extracts, further provides evidence for the involvement of these compounds in the reduction process in the NPs’ synthesis. Our conclusions were strengthened by QTOF-LC/MS-MS and multivariate analyses findings, which also revealed that around 37.5% of the detected compounds in the extracts are classified as phenolic phytochemicals. OPLS-DA modeling further confirmed this, indicating that a significant portion (30.8%) of the marker compounds for each SC and SQ were phenolics. Conversely, the elevated concentrations of Zn and Fe in the NPs derived from the aqueous extract, compared to those synthesized using alcoholic extracts, point to the aqueous extract’s superior reducing capability in the NPs’ biosynthesis process. With the exception of Fe2O3 NPs, all the tested samples exhibited promising cytotoxicity against A-431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells. Notably, SZnQ displayed the strongest effect, surpassing its parent aqueous extract, achieving 18.77% cell viability at 1000 µg/mL after 72 h of exposure, suggesting that the combined synergistic cytotoxic action of the zinc metal core and the phenolic/flavonoid coating of the NPs contributed to this therapeutic effect. The distinctive behaviors among the fabricated NPs were statistically supported by PCA, which showed a clear separation between their parent extracts (32.1% variance) and significant variability within each extract (58.9% variance). This study confirmed the differences between the source extracts and their subsequent impact on the synthesis, physicochemical properties, and biological behavior of the resulting NPs. It also stressed the necessity of selecting the appropriate extract based on thorough chemical and biological investigations of the potential parent extracts to ensure the selection of the most suitable extract for the desired nanoparticle applications. These results indicate that the green-synthesized NPs hold promise as sustainable anticancer and antioxidant agents, warranting further exploration for diverse biomedical applications. Consequently, detailed in vivo pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and chemical studies are advocated to fully elucidate their mechanisms of action, assess their bioavailability, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic profiles. A key research gap concerning optimal extraction protocols for green nanoparticle synthesis in biomedical applications is addressed in this study, which explores the biological synthesis of ZnO and Fe2O3 NPs using two distinct SP extracts.

Limitations of the study and future outlook

This study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged and may represent research gaps to be addressed in future work. The purity of the synthesized NPs was not comprehensively assessed, and no direct comparison was made with chemically synthesized counterparts. In addition, in vivo validation and evaluation on normal cell lines were not conducted, which limits the translational relevance of the current findings. Cytotoxicity testing was performed using only one cancer cell line (A-431); while this provided useful preliminary data, broader testing across multiple cancer and normal cell lines is necessary to confirm the generality of the observed effects and the NPs’ biocompatibility. Future studies will address these limitations by incorporating thorough NPs’ purity analysis, comparative assessments with chemically synthesized NPs, in vivo validation, and expanded in vitro testing on both cancerous and normal cell lines.

Data availability

All the generated data within this study are included in this published article and the supplementary file.

References

Khatami, M., Alijani, H. Q., Nejad, M. S. & Varma, R. S. Core@ shell nanoparticles: greener synthesis using natural plant products. Appl. Sci. 8, 411 (2018).

Singh, J. et al. Green’ synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 16, 84 (2018).

Noor, A., Pant, K. K., Malik, A., Moyle, P. M. & Ziora, Z. M. Green encapsulation of metal oxide and noble metal ZnO@Ag for efficient antibacterial and catalytic performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 64, 10360–10372 (2025).

Satpathy, S., Patra, A., Ahirwar, B. & Hussain, M. D. Process optimization for green synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by extract of hygrophila spinosa T. Anders and their biological applications. Phys. E Low Dimens Syst. Nanostruct. 121, 113830 (2020).

Jain, N., Jain, P., Rajput, D. & Patil, U. K. Green synthesized plant-based silver nanoparticles: therapeutic prospective for anticancer and antiviral activity. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 9, 5 (2021).

Moradi, S. Z., Momtaz, S., Bayrami, Z., Farzaei, M. H. & Abdollahi, M. Nanoformulations of herbal extracts in treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol 8, (2020).

Chan, Y. et al. Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for garcinia Mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Rev 14, (2025).

Adewale, O. B. et al. Biological synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Crassocephalum Rubens and their comparative in vitro antioxidant activities. Heliyon 6, e05501 (2020).

Krishnan, V. & Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles for topical drug delivery: potential for skin cancer treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 153, 87–108 (2020).

Liang, Y. P. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of copper oxide nanoparticles from Durian (Durio zibethinus) husk for environmental applications. Catalysts 15, 275 (2025).

Subramaniam, H., Lim, C. K., Tey, L. H., Wong, L. S. & Djearamane, S. Oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity of HCC2998 colon carcinoma cells by ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from Calophyllum teysmannii. Sci. Rep. 14, 30198 (2024).

ELhabal, S. F. et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of gold and copper nanoparticles from Salvadora persica fruit extracts and their biological properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 17, 6095–6112 (2022).

Cheah, S. Y. et al. Green-synthesized chromium oxide nanoparticles using pomegranate husk extract: multifunctional bioactivity in antioxidant potential, lipase and amylase inhibition, and cytotoxicity. Green Process. Synthesis 14, (2025).

Subramaniam, H. et al. Potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles as an anticancer agent: A review. J. Experimental Biology Agricultural Sci. 10, 494–501 (2022).

El-Fitiany, R. A., AlBlooshi, A., Samadi, A. & Khasawneh, M. A. Biogenic synthesis and physicochemical characterization of metal nanoparticles based on Calotropis procera as promising sustainable materials against skin cancer. Sci. Rep. 14, 25154 (2024).

Selvanathan, V. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and preliminary in vitro antibacterial evaluation of ZnO nanoparticles derived from soursop (Annona muricata L.) leaf extract as a green reducing agent. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 20, 2931–2941 (2022).

Mekhemar, M., Geib, M., Kumar, M., Hassan, Y. & Dörfer, C. Salvadora persica: nature’s gift for periodontal health. Antioxidants 10, 712 (2021).

Varijakzhan, D., Chong, C. M., Abushelaibi, A., Lai, K. S. & Lim, S. H. E. Middle Eastern plant extracts: an alternative to modern medicine problems. Molecules 25, 1126 (2020).

Abbas Shahid, A. A. M. U. R. S. A. A. A. H. S. H. T. M. A. Q. S. Z. I. and B. H. A. Therapeutic Effect of Salvadora persica on Multiple Skin Diseases. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 10, 1–7 (2022).

Al-Dabbagh, B., Elhaty, I. A., Murali, C., Al Madhoon, A. & Amin, A. Salvadora persica (Miswak): antioxidant and promising antiangiogenic insights. Am. J. Plant. Sci. 9, 1228 (2018).

Iyer, D. & Patil, U. K. Evaluation of antihyperlipidemic and antitumor activities of isolated coumarins from Salvadora indica. Pharm. Biol. 52, 78–85 (2014).

Al Bratty, M. et al. Phytochemical, cytotoxic, and antimicrobial evaluation of the fruits of miswak plant, Salvadora persica L. J Chem (2020).