Abstract

In our previous research, we observed a discrepancy between the apparent14C age of the carbon content of honey samples and their known age, date of the collection. The aforementioned studies demonstrated the existence of substantial old carbon intake, even older than five years, as evidenced by the outcomes of bomb-peak based radiocarbon dating. In order to ascertain the cause of the anomalies identified, a targeted nectar sample collection was conducted in Hungarian sampling areas. Consequently, the carbon isotope ratios (13C/12C and 14C/12C) of individual nectar samples from black locust, linden, phacelia, rapeseed and apple were determined by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). Furthermore, 14CO₂ data from an international atmospheric background station were employed for comparative purposes. The presented results demonstrate that the aforementioned anomalies, previously detected in honey, can also be observed in nectar samples. It has been demonstrated that carbon deposits of up to three years old, and in some cases exceeding 60–70 years of age, can be identified in nectars. In addition to representing the first 14C/12C nectar results, the findings underscore the potential for older carbon stored in soil or plants to enter the food chain through nectar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nectar derived from plants is the fundamental constituent of honey. The composition and properties of honey can vary depending on the plant species from which it is produced, but mostly the nectar determines it with also the quality of honey. In addition to the plant species and the processing carried out by bees and beekeepers, the final properties and composition of honey are also influenced by the specific honey-processing techniques employed1. Besides these, the main role of the nectar is to attract pollinators and serve as a food source for them, such as bees. From this point of view, the quality and chemical composition can affect a whole food chain, including insects, higher animals, and people as well.

Numerous analytical tools can be employed to ascertain or regulate specific chemical, physical, or biological characteristics of nectars and honey. Among these, isotope ratio measurements, which are extensively utilized in detecting honey adulteration, occupy a particularly prominent position. The 13C/12C isotope ratio, in particular, can be utilized to determine the different source contributions, thus the potential addition of C4 plant-derived sugars to the product2,3,4, as it is a powerful tool to differentiate C3 and C4 plants. In addition to the methods mentioned above, less commonly used but also applicable for honey testing is radioactive carbon isotope (14C, radiocarbon) measurements, comparing the ratio to the stable 12C. The radiocarbon method is a geochemical technique that can be used to determine the mean age or the turnover time of the carbon content in organic samples5,6,7,8.

In our previous studies, we have demonstrated that honey can exhibit unexpected radiocarbon ages, comprising old carbon, not only in Hungarian but also in US samples, utilising the bomb-peak approach5,6,7. This bomb-peak approach utilizes the elevated and decreasing level of radiocarbon (14C) in atmospheric CO2, which naturally radiolabel the whole biosphere due to the direct connection via photosynthesis. Using this radiocarbon-based method, old-carbon contributions can be differentiated by comparing our measurement data (14C/12C ratio) to a selected reference value, especially an atmospheric reference14CO2 value collected during the selected vegetation period. In addition to honey, other plant materials, such as plant sap, tree sap and maple syrups may also contain old, aged carbon, which may originate from the carbon storage of plants9,10,11,12,13. However, the presence of a soil-derived component has been less well-documented in the literature.

The radiocarbon method is best suited to distinguish soil and stored carbon sources from modern, 1-2-year-old materials, given their relative age difference compared to them. The rapidly decreasing atmospheric radiocarbon peak, produced by nuclear bomb experiments, provides a calibration curve for the method12,14,15,16. Since the Integrated Carbon Observation System’s (ICOS) station network collects and measures atmospheric 14CO2 with higher resolution, there are more available reference values on the system’s data portal17.

In order to ascertain the reason for the old radiocarbon age and old carbon contribution in honey we observed before, individual nectar samples were collected in Hungary and their carbon stable isotope ratios were measured in the HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research, Hungary. This work is unique in that there is a paucity of available data regarding the 13C/12C ratio of nectar18, and the presented results are the first nectar 14C/12C ratios which reveal the possible carbon sources of these plant liquids. In the present study, 51 samples were measured for δ13C and 50 samples for the 14C/12C ratio using IRMS and AMS techniques. The samples were collected in Hungary and included rapeseed (Brassica napus L.), apple (Malus domestica Borkh), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia Benth), linden (Tilia tomentosa Moench.) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). The black locust samples were the primary focus of the study. The isotope ratio measurements were performed on individual nectar samples, which were collected in glass capillaries.

Results

Stable carbon isotope ratio of nectar samples

The measured δ13C data are entirely consistent with the δ13C range of C3 plants (between 21‰ and − 35‰) as documented in the literature19,20,21. The measurement data can be found in Supplementary S1 (Table S1) and Fig. 1. The highest value is related to a sample of linden, but it does not exceed − 20‰ δ13C, precisely − 20.27 ± 0.01‰ (Fig. 1), from the sampling area Debrecen-Józsa, at a sampling point situated in closer proximity to a residential area (< 30 m). The other sampling points were more than 300 m away from residential areas and roads. However, further samples taken at the same sampling point do not exceed − 24‰. The most negative recorded value was observed in a sunflower sample from the Bagota sampling point, with a value of −29.12 ± 0.01‰ (Fig. 1). Similarly, another nectar collected from the same sampling point exhibited a comparable negative value, at −28.10 ± 0.02‰. The remaining sunflower samples exhibited higher values, though none exceeded − 26‰. The δ13C value of the apple samples is comparable to that of the sunflower samples, however, it should be noted that the apple nectars represent a few trees from a single sampling area. In contrast, the black locust samples were collected from three distinct sampling points at greater distances from each other (Fig. 4c), as evidenced by the broader range of δ13C results, which span from − 27.82 ± 0.01‰ to −23.44 ± 0.02‰ (Fig. 1). The data presented in this study overlap with, but do not fully coincide with, the black locust honey data published by Kropf et al. (2010). In many cases, the values are lower than those published by Kropf et al. (2010). The rapeseed nectar δ13C values presented by Li et al. (2022) (−30.2 to −26.5) are similar to the data represented in this study, with nominal values ranging from − 27.11 ± 0.06‰ to −25.55 ± 0.05‰. Nevertheless, the Phacelia samples exhibit the widest range, despite the proximity of the sampling points, which were separated by only a few hundred metres. The results for these samples span a considerable range, from − 27.78 ± 0.01‰ to −22.72 ± 0.02‰, which range is similarly wide as the range reported in Li et al. (2022) for rapeseed.

The data set exhibits a degree of overlap with the honey data from the aforementioned Kropf et al. (2010) study, yet does not entirely align with its range. The aforementioned study examined honey, rather than nectar. Consequently, the comparison is only indirect due to the absence of nectar δ13C data.

It is evident that the range of δ13C values of nectar samples from different C3 plants within a single growing season exhibits considerable variability, even in a relatively narrow geographical area such as the lowland region of the Carpathian Basin or even on samples collected from the same plant. This variability persists despite the presence of similar meteorological conditions. The evidence demonstrates that a multitude of additional factors, including soil composition and microenvironment, can exert an influence on δ13C values. Furthermore, it is evident that δ13C values of samples derived from the same plant can exhibit discrepancies. Table 1 illustrates the mean δ13C signatures of different plant nectars.

Radiocarbon in nectars

Special care was taken during sample collection to exclude nearby fossil and nuclear emissions, to ensure that significant anthropogenic emissions did not affect the measured 14C/12C ratio. The sampling areas are unaffected by 14C emissions from nuclear power plants as the nearest one is more than 200 km away. Nearby fossil (14C-free) emissions are also negligible as sampling was conducted outside urban areas. The contribution of fossil emissions to the 14CO2 values during the growing season at an urban background station in the largest nearby city is also negligible22,23. Therefore, these types of emissions cannot elevate or decrease the 14CO2 values in the air at the selected sampling sites (Table 2).

As the δ13C measurement and the 14C/12C isotope ratio measurement were not taken from the same sample, but from samples taken at the same sampling sites, a statistical comparison is not feasible. Consequently, the mean δ13C and 14C/12C isotope ratios collected at each sampling point demonstrate no correlation or relationship (Fig. 2). The raw measurement data can be accessed in Supplementary S1.

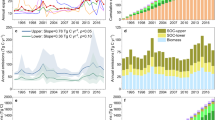

Δ14C values of nectar samples collected from Hungary. (A) shows black locust, (B) shows sunflower, (C) shows phacelia, and (D) shows apple and linden Δ14C data. The different coloured circles show the Δ14C values of the samples, the green area shows the vegetation period in 2021, while the grey shaded line shows the atmospheric reference value from the ICOS dataset (Hohenpheissenberg, Germany), the yellow shaded line shows the reference value from Hua et al. 2022. The dashed lines connected to the circles show where the measured value intercepts the y axis and the reference atmospheric line’s values as well. The red dashed line shows the mean Δ14C in the vegetation period (in HPD) in 2021. The red bands around the dashed line show the 1σ, 2σ and 3σ standard deviation (SD).

The Δ14C values of nectar samples largely overlap (Fig. 3), within measurement error, with the expected international reference background values, which, based on 14CO2 data from the ICOS station at Hohenpheissenberg (HPD), where the Δ14C values fluctuated between 2.8 and − 6.6‰ (Δ14C) for the growing season 2021. The mean Δ14C values of selected species’ nectars are listed in Table 2. Values significantly higher than this, if the nuclear-related contribution is excluded, infer some older carbon contribution, as indicated by the bomb peak, while values lower than this interval, if the anthropogenic fossil contribution is considered negligible, infer some pre-bomb peak carbon contribution.

In several instances, values that fell outside the range of the background station data were observed. Consequently, in these instances, a discernible contribution from old carbon was identified. A substantial proportion of the sunflower samples (Fig. 3b) exhibit fluctuations within the anticipated range. However, one value is markedly lower, by ~ 5.0‰ (−17.9 ± 4.3‰), than the values observed during the expected growing season based on the data from international background station (HPD). This could be a fossil contribution, but the sampling point was on farmland far from a town and a busy road, so the fossil contribution is likely to be negligible, and such a large fossil load is unlikely in this area. As the dataset is small and we observed only one markedly lower value, it could simply be a statistical outlier. A single successful apple nectar sample was obtained (Fig. 3d), exhibiting a lower Δ14C value (−14.8 ± 2.7‰) than anticipated. This is comparable to the outlier sunflower result and is accompanied by a predominantly negative bias for phacelia samples. These lower samples indicated older than 60–70 years old carbon contribution, indicating pre-bomb-peak carbon contribution, presumably from the soil carbon pool, as the phacelia (Fig. 3c) and sunflower are annual plants. In contrast, a significant proportion of the black locust samples fluctuate within the expected interval (Fig. 3a). However, in several cases, a positive bias can be measured. The highest Δ14C value observed in the black locust samples is 6.4 ± 2.8‰, indicating a potential contribution of up to 3–4 years’ older carbon to the nectar carbon content. Conversely, elevated 14C results were previously identified in tree sap and maple syrup samples, indicating the presence of old, stored carbon in trees. This older carbon is naturally radiolabelled by the previously higher14CO2 values. As it is present in the trees in the form of non-structural carbohydrates, such as sugars and starches, it does not significantly affect the measured δ13C value. This is because these substances are stored sugars from the same C3 plant and have δ13C values that fluctuate within the same range. Only one linden nectar sample exhibited no deviation from the expected background values (Fig. 3d).

Compared to the HPD station mean for the 2021 growing season (March–September), positive differences larger than 3σ SD are mainly found for acacia. For sunflowers, phacelia and apples, one sample falls outside this range in the negative direction; however, the small number of samples makes it difficult to identify an overall deviation. In the case of acacia, the positive deviation of the samples may be due to carbon stored over a long period of time. In contrast, sunflowers and phacelia are annual plants that do not store carbon over many years.

Taking into account the variability of the atmospheric values and the possible fossil contribution in a non-urban, but not atmospheric background location, such as our sampling sites, the black locust samples show clearer evidence of an old carbon contribution, possibly from stored non-structural carbon, by the enriched Δ14C results. In our preceding study, we observed comparable elevated Δ14C values in black locust honey samples, yet al.so discerned diminished Δ14C values that fell below the anticipated atmospheric14CO2 reference value6.

These findings corroborate the sequence of results previously observed in honey samples and demonstrate the incorporation of older carbon into honey5,7, presumably via the nectar and other carbon sources. In our previous study, we listed the possible effects of potential carbon sources on the observed Δ14C value of honey7. The stored carbon pools may contain 14C-enriched carbon due to the natural labelling of bomb carbon, while the carbon stored in the soil may have a lower 14C/12C ratio due to the long-term formation and storage of carbon in the soil7,9. Because sap is a complex mixture of plant fluids mixed within the plant itself, it is difficult to distinguish the contribution of different substances to the plant bulk radiocarbon value. This would require targeted investigations, such as targeted nectar sampling in the case of honey, or compound specific radiocarbon measurements can be taken of the major organic components of the sap, such as sugars, amino acids, oligosaccharides organic acids and plant hormones24,25, but if a compound has different sources, such as sugars from different pools, it is difficult to determine the source.

Reed et al.26 reported that in Abutilon plants, active sugar accumulation in floral nectaries can be accompanied by passive water flow, which dilutes the nectar. Thus, the presence of a xylem in the nectary, which may increase the likelihood of passive water outflow, is also relevant in this context. Konarska27 observed that clammy locust (Robinia viscosa) nectaries have a small number of xylem elements, and xylem can also be found in floral nectaries of several Asteraceae species28,29.These xylem vessels transport the aqueous solution taken up by the roots, which can dilute the nectar. The movement of xylem water and the different age carbon transported by it into the nectaries (and into the nectar) may explain the minor variations in black locust honey radiocarbon data compared to the waited results. According to Yamada et al.30, living wood fibers found in the outer part of the annual ring function as “single-use” starch storage in black locusts. The latter authors studied the dynamics of these starch grains over a year under a light microscope, and they found that most of these starch pools degrade by June. However, as the authors noted, the detection of small starch grains is limited using image analysis. Consequently, several small starch grains may enter the apoplastic space after these living wood fibers die. The latter can be a part of the non-structural carbon storage in black locust trees.

Our results, presented in this study corroborate the hypothesis that the observed carbon contribution in honey may be introduced into honey not from honey processing but from natural sources, as it is already present in the nectar itself. Since annual plants cannot store carbon for years, one of the most likely sources of old carbon, which was also detected in nectar in this study, is soil.

The results shown here are the first nectar radiocarbon (Δ14C) dataset. Based on the presented results, the radiocarbon age of the nectar was relatively recent, but in some cases (at least in 8 cases out of 50 samples), it may be influenced by older carbon contributions. In some instances, the carbon contribution is as old as 3–4 years, while in others, it may be considerably older, up to 60–70 years old. This effect can be attributed to the stored non-structural carbon in the case of black locust samples; however, in annual plants, such as phacelia and sunflower, it may originate from the soil, as these plants do not store carbon for years. These results corroborate our previous findings, which demonstrated that honey also exhibits this radiocarbon offset in comparison to the anticipated background atmospheric14CO2 value. The reported δ13C data of nectar show consistent values with those reported in the literature. As nectar is part of the food chain through the honeybee, studying it is important not only from a plant-life perspective but also from a human perspective. In the future, this should also be taken into account when planning plant protection treatments.

Materials ad methods

Nectar sampling

The samples were collected from the eastern region of Hungary, in the extensive arable areas of the Hajdú-Bihar county. This area has sedimentary bedrock with a negligible carbonate content. All of the nectars were collected on farmlands during the blooming period of selected species in 2021, at least 100 m distance from main roads. The locations and selected species are indicated on Fig. 4. and listed in Table 3. All the areas where the arable crop samples were collected, such as phacelia, sunflower and rapeseed, are under continuous agricultural cultivation. The apple sample, however, comes from an orchard. The black locust and linden nectars were collected from forests surrounded by agricultural land. The nectar sample collection was executed with the farmers’ authorization.

Location of Hungary (A) and the sampling sites and selected species in Hungary (B), and the species and the number of sampling site (listed in Table 3) in Hajdú-Bihar county (C). The maps were created using QGIS 3.8.0, an open-source software program (https://qgis.org/), with Google Satellite layers as the basemaps.

The samples from individual flowers from the selected plants on field conditions were collected using a sterile glass capillary tube (inner volume ~ 10 µL) (Marienfeld capillary for melting point determination, 80 × 0.6 mm). These capillaries simply suck the nectar out of the flowers by the capillary-effect. The applied capillary tubes were preheated at 300℃ to eliminate carbon contamination. This type of capillary tubes are generally used for 14C/12C measurements in the HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research for fuel and wine analyses before, without significant contamination31,32. Each capillary contained 5–10 µL of nectar. As the capillaries were not combined, each result represents an individual nectar sample. Photos of the sample collection can be found in Supplementary File S1 (Figure S1-S4). None of the plants were protected species. Only nectar were collected during the survey; no plant tissues were taken.

Isotope ratio measurements

Individual nectar samples were collected into capillary tubes from individual flowers of the selected plants. The samples were not chemically pre-treated. Isotope ratio measurements were taken from the bulk material. The liquids in their sampling capillary tube were dropped and sealed into a bigger glass test tube that also contained ~ 300 mg MnO2 powder (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99%) oxidizing reagent. Then, the test tubes were flame-sealed by a gas torch under vacuum (< 5*10−2 mbar). Then, the sealed ampoules were combusted in a laboratory muffle furnace at 550 ℃ for 12 hours to convert the total carbon content of the samples to CO2 gas. Then, the CO2 content of the samples was extracted and purified in a dedicated vacuum line, which is further detailed in our former honey studies5,33. Measurements of the 14C/12C and 13C/12C ratios were taken from different samples collected at the same site. After this, the samples were further processed for AMS and IRMS (dual inlet mode) measurements. The purified CO2 for 14C/12C measurement were graphitized using the sealed tube graphitization method, described in Rinyu et al.34,. This indicates that at least 200 µg carbon was extracted, mostly between 200 and 500 µg of carbon. For the AMS-based 14C/12C ratio measurements, a MICADAS type (ETH Zürich) mass spectrometer was used35, and for the IRMS-based 13C/12C measurements, a Finnigan DELTAPLUS XP (Thermo Fisher Scientific) type mass spectrometer was used in the HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research. The same combustion method was used for the δ13C measurements as for the 14C/12C preparation. A minimum of 200 µg of carbon (between 200 and 500 µg) was extracted from individual nectar samples for the δ13C measurement. The measurement setup and method are the same as used before for honey samples detailed in Varga et al., (2024). The 14C results are expressed in Δ14C units36,37.

For the comparison of local nectar Δ14C data, we used an ICOS background atmospheric station’s Δ14C data set, namely from the Hohenpeissenberg (HPD) station (South Germany), which has produced background14CO2 data since 2016 17.

The stable carbon isotope results are expressed in conventional delta notation, where δ13C values are relative to the VPDB standard38,39. The stable carbon isotope ratio of samples was compared to reference materials to avoid systematic errors. The δ13C values are calculated using the following equation:

where Rsample and Rreference are the measured isotope ratio of the sample and isotope ratio of the reference material, respectively. The δ13C values are expressed against the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB), per mille.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and the datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

De-Melo, M., Almeida-Muradian, A. A., de Sancho, L. B., Pascual-Maté, A. & M. T. & Composition and properties of apis mellifera honey: A review. J. Apic. Res. 57, 5–37 (2018).

Zhou, X., Taylor, M. P., Salouros, H. & Prasad, S. Authenticity and geographic origin of global honeys determined using carbon isotope ratios and trace elements. Sci. Rep. 8, 14639 (2018).

Schellenberg, A. et al. Multielement stable isotope ratios (H, C, N, S) of honey from different European regions. Food Chem. 121, 770–777 (2010).

Doner, L. W. & White, J. W. Carbon-13/Carbon-12 Ratio Is Relatively Uniform Among Honeys. Science (80-.). 197, 891–892 (1977).

Varga, T. et al. Isotopic study of honey documents widespread plant uptake of old carbon in North America. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174691 (2024).

Varga, T. et al. Honey as an indicator of long-term environmental changes: MP-AES analysis coupled with 14 C-based age determination of Hungarian honey samples. Sci. Total Environ. 736, 139686 (2020).

Sajtos, Z. et al. Rape, sunflower and forest honeys for long-term environmental monitoring: presence of indicator elements and non-photosynthetic carbon in old Hungarian samples. Sci. Total Environ. 808, 152044 (2022).

Sierra, C. A., Müller, M., Metzler, H., Manzoni, S. & Trumbore, S. E. The muddle of ages, turnover, transit, and residence times in the carbon cycle. Glob Chang. Biol. 23, 1763–1773 (2017).

Muhr, J. et al. How fresh is maple syrup? Sugar maple trees mobilize carbon stored several years previously during early springtime sap-ascent. New. Phytol. 209, 1410–1416 (2016).

Carbone, M. S. et al. Age, allocation and availability of nonstructural carbon in mature red maple trees. New. Phytol. 200, 1145–1155 (2013).

Richardson, A. D. et al. Distribution and mixing of old and new nonstructural carbon in two temperate trees. New. Phytol. 206, 590–597 (2015).

Richardson, A. D. et al. Seasonal dynamics and age of stemwood nonstructural carbohydrates in temperate forest trees. New. Phytol. 197, 850–861 (2013).

Peltier, D. M. P., Carbone, M. S., Ogle, K., Koch, G. W. & Richardson, A. D. Decades-old carbon reserves are widespread among tree species, constrained only by sapwood longevity. New. Phytol. 245, 1468–1480 (2025).

Hua, Q. et al. ATMOSPHERIC RADIOCARBON FOR THE PERIOD 1950–2019. Radiocarbon 00, 1–23 (2022).

Guadinski, J. B. et al. Use of stored carbon reserves in growth of temperate tree roots and leaf buds: analyses using radiocarbon measurements and modeling. Glob Chang. Biol. 15, 992–1014 (2009).

Trumbore, S. E. Comparison of carbon dynamics in tropical and temperate soils using radiocarbon measurements. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 7, 275–290 (1993).

Kubistin, D. et al. ICOS ATC/CAL 14 C Release, Hohenpeissenberg (131.0m), 2015-09-24-2022-10-26, ICOS RI. doi: (2023). https://hdl.handle.net/11676/e9X5rkp9vL-D6lBVYTH9BYGg

Li, H. et al. Study on stable carbon isotope fractionation of rape honey from rape flowers (Brassica Napus L.) to its unifloral ripe honey. Food Chem. 386, 132754 (2022).

White, J. W. & Winters, K. Honey protein as internal standard for stable carbon isotope ratio detection of adulteration of honey. J. AOAC Int. 72, 907–911 (1989).

Reiffarth, D. G., Petticrew, E. L., Owens, P. N. & Lobb, D. A. Sources of variability in fatty acid (FA) biomarkers in the application of compound-specific stable isotopes (CSSIs) to soil and sediment fingerprinting and tracing: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 565, 8–27 (2016).

O’Leary, M. H. Carbon isotopes in photosynthesis. Bioscience 38, 328–336 (1988).

Molnár, M. et al. Fossil fuel CO2 Estimation by atmospheric 14 C measurement and CO2 mixing ratios in the City of Debrecen, Hungary. J. Radioanal Nucl. Chem. 286, 471–476 (2010).

Major, I., Furu, E., Haszpra, L., Kertész, Z. & Molnár, M. Carbon in Atmospheric PM 2.5 and Carbon Dioxide in Debrecen, Hungary. Radiocarbon 57, 991–1002 (2015). One-Year-Long Continuous and Synchronous Data Set of Fossil.

Broussard, L. et al. Phloem Sap composition: What have we learnt from metabolomics? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6917 (2023).

Esteves, E., Locatelli, G., Bou, N. A. & Ferrarezi, R. S. Sap analysis: A powerful tool for monitoring plant nutrition. Horticulturae 7, 1–13 (2021).

Reed, M. L., Findlay, N. & Mercer, F. V. Nectar production in Abutilon. Water and solute relations. Aust J. Biol. Sci. 24, 677–688 (1971).

Konarska, A. Microstructure of floral nectaries in Robinia viscosa var. Hartwigii (Papilionoideae, Fabaceae)—a valuable but little-known melliferous plant. Protoplasma 257, 421–437 (2020).

WIST, T. J. & DAVIS, A. R. Floral nectar production and nectary anatomy and ultrastructure of Echinacea purpurea (Asteraceae). Ann. Bot. 97, 177–193 (2006).

Davis, A. R., Peterson, R. L. & Shuel, R. W. Anatomy and vasculature of the floral nectaries of brassica Napus (Brassicaceae). Can. J. Bot. 64, 2508–2516 (1986).

Yamada, Y., Awano, T., Fujita, M. & Takabe, K. Living wood fibers act as large-capacity single-use starch storage in black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). Trees 25, 607–616 (2011).

Varga, T. et al. Radiocarbon dating of microliter sized Hungarian Tokaj wine samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 118, 105203 (2023).

Varga, T. et al. Intercomparison excercise on fuel samples for determintion of biocontent ratio by 14 C accelerator mass spectrometry. Radiocarbon 65, 539–548 (2023).

Janovics, R., Futó, I. & Molnár, M. Sealed tube combustion method with MnO2 for AMS 14 C measurement. Radiocarbon 60, 1347–1355 (2018).

Rinyu, L. et al. Optimization of sealed tube graphitization method for environmental C-14 studies using MICADAS. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms. 294, 270–275 (2013).

Molnár, M. et al. Status report of the new AMS 14 C sample Preparation lab of the hertelendi laboratory of environmental studies (Debrecen, Hungary). Radiocarbon 55, 665–676 (2013).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion reporting of 14 C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Stenström, K. E., Skog, G., Georgiadou, E., Genberg, J. & Johansson, A. A Guide To Radiocarbon Units and Calculations Lund University (Department of Physics, Division of Nuclear Physics, 2011).

Coplen, T. B. et al. New guidelines for δ 13 C measurements. Anal. Chem. 78, 2439–2441 (2006).

Hoffman, D. W. & Rasmussen, C. Absolute carbon stable isotope ratio in the Vienna Peedee belemnite isotope reference determined by 1 H NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 94, 5240–5247 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the European Union and the State of Hungary, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund in the project of GINOP-2.3.4-15-2020-00007“INTERACT”. Zsófi Sajtos was supported by the EKÖP-24-4 University Research Scholarship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. Zsuzsa Lisztes-Szabó was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences [BO-357-23-10].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TV, ZS, ZLS and MM planned and designed the research. TV, IF, ZS, BB and ZLS performed experiments, conducted fieldwork, analysed isotope data. TV, ZS, BB, ZLS and MM wrote the manuscript. ZLS identified the species studied. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Varga, T., Sajtos, Z., Buró, B. et al. Tracing old carbon sources in Hungarian nectar samples using radiocarbon analysis. Sci Rep 15, 36704 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20578-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20578-6