Abstract

In India, biofloc systems for freshwater fish farming have encountered significant challenges, with many projects failing due to widespread disease outbreaks. This study investigates the causes of these outbreaks, revealing that unhygienic conditions play a major role in the emergence of new diseases. Focusing on Anabas testudineus, the study examines the link between poor biofloc management, reverse zoonosis, and antimicrobial resistance. Twelve pathogenic bacterial isolates were recovered from fish reared in biofloc environments and identified through morphological, biochemical, and molecular techniques. Among these, eight were gram-negative rods and four were gram-positive bacilli. Notably, molecular identification revealed that most of the isolates, including Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella aerogenes, Citrobacter werkmanii, and Acinetobacter seifertii, are primarily human pathogens, rarely reported in fish. These bacteria exhibited various exoenzyme activities, indicating their pathogenic potential. Antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed inherent resistance in most isolates, raising concerns about biofloc systems fostering antimicrobial resistance even without prior antibiotic exposure. The study also underscores the risk of reverse zoonosis, emphasizing the need for stronger biosecurity measures to prevent the transfer of pathogens between humans and fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, biofloc systems for freshwater fish farming in India have encountered significant challenges, with many projects failing due to widespread disease outbreaks. As global demand for seafood continues to rise due to increasing health awareness, population growth, and shifting dietary preferences1, the aquaculture industry is under pressure to meet market demands while adhering to more environmentally stringent regulations2. To address the depletion of water resources and the limitations of capture fisheries, the industry has transitioned from traditional to intensive aquaculture systems, aiming to maximize fish production while minimizing the use of water, land, and space. Among many types of advanced aquaculture systems, biofloc technology (BFT) has gained attention for its potential to enhance biosecurity, improve environmental stewardship, and ensure economic viability3,4. This technology is regarded as a dynamic alternative method because nutrients can be recycled and reused in perpetuity. The sustainable viewpoint of such a system is highly based on in-situ microbial cells as it needs minimum or zero water exchange rates, making this technology a cost-effective and environment-friendly ecosystem that supports sustainable aquaculture, conserves feed inputs, and utilizes wastewater during the production system.

BFT, a closed-loop aquaculture system, utilizes microorganisms to improve water quality, recycle nutrients, and manage diseases5. Countries such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Bangladesh have increasingly adopted BFT due to its cost-effectiveness and ecological benefits. A recent study highlighted India as the third most productive nation in biofloc farming, following Brazil and China4. The system promotes sustainability by converting toxic ammonia into protein-rich flocs, reducing the need for water exchange, and conserving feed resources6,7. Despite these advantages, disease outbreaks remain a significant hurdle to the success of biofloc systems, particularly in India. Several research studies8,9,10 have found the presence of Aeromonas hydrophila, A. salmonicida, Pseudoalteromonas aeruginosa, Vibrio alginolyticus, V. fluvialis, Bacillus cereus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Staphylococcus sp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae. All of these microbes have their role and interact with one another in the system to facilitate the bioremediation mechanism.

Anabas testudineus, commonly known as climbing perch, is an indigenous fish species in India and plays a key role in freshwater aquaculture in Northeast India11. The species is well-suited to biofloc systems due to its tolerance to high particulate matter and poor water quality, making it especially popular in regions like Tripura, which has one of the highest per capita fish consumption in the country12. However, the growing population and geographical constraints in the region have limited the expansion of fish farming, increasing the reliance on innovative methods like biofloc-based culture to meet the rising demand for fish protein. Despite the benefits of biofloc technology, the system has been hindered by disease outbreaks, which have caused significant losses in fish production.

Diseases caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites, and other pathogens are major challenges in aquaculture. In biofloc systems, pathogenic bacteria can thrive under suboptimal environmental conditions, leading to disease outbreaks13. Poor water quality, particularly ammonia poisoning, can impair fish immune responses and increase susceptibility to infections14. While biofloc systems offer natural immune-enhancing properties through the presence of probiotics and heterotrophic bacteria that help regulate ammonia levels and suppress harmful pathogens9, disease outbreaks remain a persistent issue. This is particularly evident in West Bengal, where biofloc farms have reported significant mortalities due to inadequate disease prevention and treatment measures15. Inadequate knowledge in terms of water quality, floc quality and quantity, low-quality probiotics, electricity problems, non-trained culturist, insufficient aeration and build-up of NH4+-N and NO2- poses an even greater challenge to farmers who may incur significant losses due to pathogenic bacteria in the biofloc microbial community, leading to disease outbreaks and economic loss16. In contrast, inadequate and unstable water quality is caused by the inability of the microbial community to regulate the concentration and ionic balance of all nutritional constituents in BFT16. In Anabas culture, both pond and biofloc systems have been vulnerable to disease outbreaks, with several unpublished reports highlighting the frequent occurrence of diseases linked to improper stocking practices and the use of untreated water17. This study aims to address these challenges by identifying and isolating bacterial pathogens associated with disease outbreaks in biofloc systems, followed by phylogenetic analysis based on partial 16 S rRNA gene sequences to confirm the evolutionary relationships of these pathogens. The findings from this research will be crucial for developing effective disease management strategies, including targeted therapies and vaccination approaches, to mitigate the impact of diseases in biofloc-based aquaculture systems.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

All experiments involving fish were performed in accordance with the standard national and international guidelines and policies suggested by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of the College of Fisheries, Central Agricultural University, Imphal with approval number CAU-CF/48/IAEC/2018/03.

Farm location

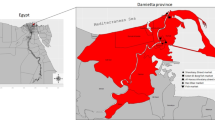

The study was carried out for a period between December 2021 to April 2022. A total of eleven biofloc farms in Tripura, India, having disease were selected for the study (Fig. 1; Table 1). The investigation was initiated through National Surveillance Programme for Aquatic Animal Diseases Phase II project in response to reports from farmers concerning fish mortalities and by active surveillance. The affected fishes primarily weighed over 50 g. Employing visual signs such as exophthalmia, fin base and scale pocket hemorrhages, and fin erosion.

Sample collection

To determine the environmental conditions, parameters such as temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, alkalinity, ammonia, and nitrite were estimated utilizing methods advocated by APHA18. Remarkably, these parameters remained consistently stable across all the sampled farms, with dissolved oxygen averaging at 9.5 ± 0.5 mg/L, temperature at 22 ± 2.5 °C, and pH at 7.0 ± 1.50. Although owned by different individuals, these farms exhibited similar culture conditions, encompassing the utilization of commercial diet and the rearing of fish in tanks measuring 10–20 m3, with a density ranging from 80 to 100 individuals per cubic meter. After transportation to the laboratory, the handling of the fishes adhered strictly to the existing laws and acts in India.

Isolation of pathogenic bacterial isolates

The process of bacterial isolation stands as a pivotal stage in the identification and control of the disease, executed in accordance with standard laboratory methods. In order to initiate, fish samples in their morbidity state were humanely sacrificed through decapitation, duly cleaned with 70% alcohol before dissection. The kidney, liver, and spleen were carefully obtained in sterile manner and subsequently macerated in physiological saline, maintaining a ratio of 1:10 (weight of tissue to volume of diluent). Following this, a centrifugation at 5000 RPM was done, followed by a series of dilutions up to a 10−5. The diluted samples were methodically spread across sterile nutrient agar (NA) plates. These inoculated plates were then incubated at a constant temperature of 35 °C for duration of 24 h. Upon completion of the incubation period, a thorough examination of the colony morphology on the NA plates was carried out, enabling the identification and selection of distinct colonies exhibiting unique characteristics such as color, size, and shape. The chosen colonies were subsequently streaked onto fresh NA plates to achieve a pure culture and incubated at 35 °C for duration of 24 h.

Phenotypic characterization of isolates by presumptive biochemical test

The bacterial isolates underwent phenotypic characterization to ascertain their probable identification. Subsequently, identification of bacteria is based on the characteristics of Gram’s stain, colony morphology, and motility. Additionally, a series of biochemical assays was also conducted. It includes nitrate reduction tests, urease test, IMViC assessments (Indole, Methyl red; Voges-Proskauer and Citrate) exclusively for gram-negative isolates. Furthermore, the catalase test, gas production from glucose, triple sugar iron test, amino acid decarboxylation evaluation, and carbohydrate fermentation test were carried out by using media from HiMedia, India in accordance with established methodologies19,20,21.

Molecular identification

DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and sequencing

The most advanced technique for categorizing and identifying microorganisms is molecular approach. Molecular identification of each bacterial isolates obtained was done by using universal bacterial primer 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, 27F (5’ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG 3’) and 1492R (5’ TACGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT 3’)22,23.

Bacterial genomic DNA extraction and 16 S rRNA PCR amplification

The heating technique was used to extract genomic DNA from the fresh bacterial culture by growing on NA for 24 h at 35 °C. A loopful of this culture was suspended in 50 µl of 1x Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 8.0) and lysed at 98 °C for 15 min in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) followed by snap cooling at -20 °C. The cell debris was settled by centrifugation at 10,000 RPM for 2 min and the supernatant was used as DNA template for PCR amplification. All the PCR reactions were performed in a thermal cycler24. The gene amplification was accomplished by employing 16 S rRNA universal bacterial primers25. The reaction was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Eppendorf) with reaction mixtures (final volume 25 µl) containing 13 µl of PCR Master mix (HiMedia, India), 1.0 µl (10 pmol) each of forward and reverse primers, 1.0 µl of DNA template and 9 µl of nuclease-free water. Amplification was performed with the program as 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension of 72 °C for 7 min24,25,26.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The purified PCR products were sequenced with the same universal primer 27 F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) in forward direction by using the Sanger sequencing method and was carried out in an automated DNA Analyzer (ABI3730 (48 capillary) Sequencers, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) at Bioserve Biotechnologies Pvt. Ltd., India. The sequence data were compiled, analyzed, and matched with the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) algorithm27 with the help of Chromas software (Technelysium Pvt. Ltd., Australia). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method28 using the software MEGA1129. Phylogenetic neighbours were selected based on the results of BLAST using 16 S rRNA sequences of the isolates and closely related species retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. Genetic distances were obtained by employing Kimura’s 2-parameter model30.

Antibiotic susceptibility test

The antibiotic sensitivity test was used to determine the sensitivity or resistance of the isolates to specific antibiotics. The test was conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). This was performed using reliable and widely used Kirby-bauer disc diffusion method described by Bauer31. A total of 16 antibiotic discs Amikacin, Cefoxitin, Cephalothin, Chloramphenicol, Clindamycin, Nitrofurantoin, Tobramycin, Trimethoprim, Neomycin, Oxytetracyclin, Cefotaxim, Cefalexin, Ticacilin, Furazolidin, Bacitracin, Spectinomycin (HiMedia, India) having different discs potency were used. Muller-Hinton agar (HiMedia, India) plates were prepared aseptically and swabbed with overnight grown cultures of the bacterial isolates and antibiotic discs were aseptically placed. The plates were incubated at 35 °C for 24 h. After incubation period the clear zone formed around the antibiotics disc was recorded using Antibiotic Zone Scale (HiMedia, India). Zone diameters of inhibition were interpreted as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on CLSI breakpoints.

Determination of phenotypic virulence potential of the isolates

The phenotypic detection of virulence determinants of the test bacteria was analyzed based on their ability for the expression of some soluble virulence factors such as gelatinase activity32, amylase activity33, lipase activity34, DNase activity35, caseinase activity36, and biofilm production37 by following the standard protocol.

Results

Collection of diseased fish sample

External examinations of fish show fin erosion (Fig. 1a), hemorrhages of fin base and scale pocket (Fig. 1b), exophthalmia in eyes and hemorrhage around the periorbital tissue (Fig. 1c). Many of the infected fish with abnormal behaviour or clinical sign became eviscerated. A total of twelve bacterial isolates were originally recovered. All isolates were obtained from head kidney, liver and spleen of diseased A. testudineus by spreading on NA plates. At first multiple colonies with distinct morphology were obtained and then pure cultures were procured by streaking and re-streaking of the morphologically distinct isolated colony on fresh NA media. Then isolated pure cultures were preserved in tryptone broth supplemented with glycerol and stored at 4 °C. The bacterial isolates with distinct morphology were obtained and coded as B3.1, B3.2, B6.1, B6.2, B7.1, B7.2, B7.3, B8.1, B9.1, B9.2, B9.3, B11.1.

Phenotypic identification of pathogens

Lesions and mortality from the farms

Severe tissue damage was found in the sampled fish. Some fishes presented multiple bacterial colonies on their body.

Isolation, phenotypic and biochemical characterization

Among the eleven sampling sites scrutinized, a notable collection of twelve harmful bacterial isolates was carefully obtained from commercial biofloc, revealing a concerning incidence of diseases. To determine the identification of these bacterial isolates, a mix of advanced methods, including gram staining, biochemical tests, and molecular characterization, were used. Noticeably, a formidable majority of the isolates, precisely 66.66%, displayed the gram-negative affinity, while the remaining 33.33% intriguingly showed gram-positive. The colonies, with a rod-shaped symmetry, had an intriguing gram-negative composition (named as B6.1, B6.2, B7.1, B7.2, B7.3, B9.3, and B11.1), while the remaining were gram-positive counterparts (named as B3.1, B3.2, B8.1, and B9.2). B6.1 and B7.1 of the isolated microbial group showed low or surface motility.

Biochemical characterization of isolated bacteria

The physiological and chemical responses of all bacterial isolates are shown in Table 2. Different biochemical tests like oxidase, catalase, indole, MR, VP, citrate utilization, TSI, H2S production, nitrate reduction test, amino acid decarboxylation (ornithine and lysine), urease test and carbohydrate fermentation (glucose, sucrose, arabinose and inositol) were performed, and the results were analysed by following the method suggested by Bergey’s manual38.

Molecular identification

PCR amplification and sequence analysis

To classify the bacterial organisms taxonomically, we selectively amplified the 16 S rRNA genes from twelve isolates and analyzed their genetic information. This data was then compared to closely related 16 S rRNA sequences available in the GenBank database. All 16 S rRNA sequences derived from these twelve bacterial isolates, obtained during this study, have been cataloged and deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers OP218088 to OP218099.

Nucleotide BLAST and phylogenetic analysis of the isolated bacteria

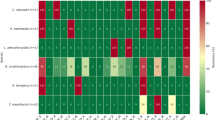

The identity of bacterial isolates after comparing their DNA sequences with those available in the GenBank NCBI (National Centre for Biotechnology Information) database using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) 2.13.0 + program showed similarity with the identified species and isolate codes B11.1, B9.2, B7.1, B3.1, B3.2, B6.1, B6.2, B9.1, B7.3, B8.1, B7.2, and B9.3 were identified with their NCBI Accession no. Enterobacter ludwigii (OP218088.1), Brevibacillus borstelensis (OP218089.1), Acinetobacter seifertii (OP218090.1), Paenibacillus azoreducens (OP218091.1), Aneurinibacillus migulanus (OP218092.1), Acinetobacter nosocomialis (OP218093.1), Citrobacter werkmanii (OP218094.1), Enterobacter ludwigii (OP218095.1), Enterobacter cloacae (OP218096.1), Bacillus cereus (OP218097.1), Enterobacter asburiae (OP218098.1), and Klebsiella aerogenes (OP218099.1) respectively. The identification results were similar to those found through physiological and biochemical identification. By constructing a single comprehensive phylogenetic tree, it was revealed that B. borstelensis, P. azoreducens, A.migulanus, and B. cereus form a distinct cluster within the Firmicutes phylum with Paenibacillaceae and Bacillaceae family respectively. E. cloacae, E. ludwigii, and E. asburiae were grouped together, suggesting their close evolutionary relationship within the family Enterobacteriaceae. Additionally, K. aerogenes and C. werkmanii were found to be closely related within the Enterobacteriaceae family. A. seifertii and A. nosocomialis clustered together, forming a distinct branch within the Moraxellaceae family of Proteobacteria phylum (Fig. 2).

Antibiotic susceptibility test

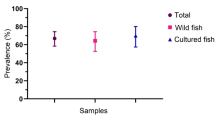

During the evaluation of antibiotic susceptibility, most bacterial isolates demonstrated a notable sensitivity to a wide spectrum of antibiotics (Table 3). Moderately, chloramphenicol displayed a sensitivity rate of 66.6%. Clindamycin and bacitracin, exhibited a resistance rate of 91.6%. Cefoxitin registered an 83.3% resistance rate, while cefalexin presented a 50% resistance rate. Moreover, the bacteria exhibited resistance to trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, neomycin, and oxytetracycline at rate of 33.3% (Fig. 3). Notably, the antibiotic susceptibility profile of major bacterial divisions is visually represented in Fig. 4.

Determination of virulent potential of the isolated bacteria

The phenotypic determinants were assayed by gelatinase, amylase, lipase, DNase, caseinase activity, and biofilm production (Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed at the isolation and identification of bacterial pathogens associated with diseased fish of biofloc-based aquaculture units in Tripura’s landscapes. In addition to the presence of disease in anabas fish from six biofloc farms, co-infections involving multiple bacterial pathogens were detected at several of these sites. Fishes having significant signs of disease, such as ulcerative skin lesions, unusual behaviour, or morbidity were sampled. Subsequently, biochemical and molecular diagnosis by using 16S rRNA universal primer was done. The characterization of pathogens allows us for better disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, thereby safeguarding the health and productivity of fish reared in Biofloc systems. The human bacterial pathogens that were isolated and identified include Acinetobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella aerogenes and Citrobacter werkmanii. Given the importance of the A. testudineus in aquaculture especially in Tripura, we reported varied level of mortality associated with pathogenic bacteria among different commercial biofloc farms in this species only. During the present study first author observed severe ulcers, skin lesions, tail-rot, and hemorrhages at the base of the fins and scale pocket, which had not been previously described by other authors in this system.

Several studies in recent times have revealed that the new pathogens are also being isolated from the infected fishes in addition to the conventional or previously known fish pathogens. More precisely, Gram-negative bacteria that are usually recognized to be detrimental to fish, such as Aeromonas spp., Flavobacterium spp., and Pseudomonas spp., are substituted by other species (Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacter spp.) that were previously unknown to be virulent or even mildly pathogenic to fish39 and similar result are obtained in this study. Under suboptimal water conditions, the presence of harmful bacterial communities can escalate into pathogenic forms that proliferate in the nutrient-rich environment of BFT systems16. Several researchers found that flocculating bacteria of biofloc system act as an immunostimulant thereby preventing the cultured fish species from disease. The fish and shrimp cultured under this system shows resistant potential towards the pathogens when challenged with bacterial and viral agents40,41. Few reports available in literature that describe the presence of pathogenic bacteria such as Vibrio fluvialis, V.alginolyticus, A. hydrophila, A. salmonicida, and P. aeruginosa etc. in the biofloc making the bioremediation process successfully happen with dominating amount of heterotrophic and nitrifying bacteria42 but in this study we report association of pathogenic bacteria as probable cause of disease. In the present study, we have identified E. ludwigii (OP218088.1 and OP218095.1), E. cloacae (OP218096.1), E. asburiae (OP218098.1) and K. aerogenes (OP218099.1) under Enterobacteriaceae family. E. cloacae and E. ludwigii of this group have been identified as pathogenic and causes mortality of mullet, Mugil cephalus43, as well as fairy shrimp, Branchinella thailandensis44 in normal rearing condition not in biofloc. Researcher reported that E. cloacae is associated with mortality in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus which was raised in freshwater11. Results of VP, glucose, sucrose, ornithine decarboxylase, catalase, nitrate reduction, citrate utilization, lactose fermentation and catalase tests for this group are in accordance with work done by researchers45,46 for similar bacteria with little variation, this may be due to differences in environmental conditions or inherent molecular variations among isolates, which should be clarified using isolates from other hosts, including climbing perch from across the world.

The genus Acinetobacter has a heterogeneous group of microbes and is considered “the most problematic” by physicians and scientists47. Recently, Acinetobacter spp. was isolated as an emerging fish pathogen from fresh and marine water48,49,50. In the present study A. seifertii COF_AHE30 (OP218090.1) and A. nosocomialis COF_AHE33 (OP218093.1) were obtained. A. seifertii is a new species that is mainly associated with human disorders51, and it is a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex that has been acquired from human clinical samples. This was recently recognized as an emerging pathogen related to human diseases, including bacteremia49 . The probable presence of Acinetobacter spp. based on our research in the biofloc system may enter with flowing water which was the source of water for the culture unit, because this bacterium is generally considered as hospital associated and entered the flowing water with hospital discharge52.

B. cereus COF_AHE37 (OP218097.1) isolated in the present study from A. testudineus is generally considered as a foodborne disease in humans and it displays symptoms including abdominal cramps, pain, and watery diarrhoea associated with the consumption of contaminated food53,54,55,56. It may also induce local and systemic infections in humans54 and more recently, it has been classified as a fish-threatening disease, resulting in massive financial losses in the aquaculture industry57. Apart from fishes, in shrimp aquaculture there is an earlier report of B. cereus known to cause bacterial white patch disease57. B. cereus has a high pathogenicity potential due to their lipase activity, haemolytic activity as reported by Vidal58 for which similar reports was found in the present study. Moreover, B. cereus has been used as a probiotic in fish and shrimp aquaculture58 raising more concerns regarding their usage as probiotics. Therefore, before using it as probiotic candidate species, their pathogenicity potential should be determined.

Paenibacillus was reported from several environmental and dietary sources and responsible for milk and other dairy product deterioration59, as well as it causes chronic kidney disease in humans. In the present study we have identified P. azoreducens COF_AHE31 (OP218091.1) under this group for the first time in diseased fishes under biofloc system. P. azoreducens obtained from industrial wastewater with ability to decolorize the azo dye Remazol Black B60. Brevibacillus species. is a former Bacillus species that is usually associated with soil, isolates of which have been identified in the dairy environment61. Researchers from Bangladesh (international boundary with Tripura) isolated and identified Brevibacillus spp. for the first time from diseased rohu with scale erosion, reddish skin, and pale gill62 thus similar results with biofloc system of Tripura posing threat in future aqua based practices of the region. B. borstelensis COF_AHE29 (OP218089.1) was isolated in the present study under this group shows consistent result with work done by Almeida in biochemical assessment (MR, VP, catalase, oxidase and Arabinose)63.

In the present study A. migulanus COF_AHE32 (OP218092.1) and Citrobacter werkmanii (OP218094.1) was isolated from anabas having exophthalmia, and hemorrhagic fin base. Citrobacter spp. was pathogenic to various fish species and showing mortality in Oncorhynchus mykiss, Garra rufa obtusa, Rhamdia quelen, Carassius auratus and many more other species64,65,66,67.

In the commercial biofloc units, where the pathogenic bacterial incidents have been observed, there exists the potential for the intrusion of these microorganisms into the culture system of fish, possibly via soil and water source. To mitigate the exposure to these pathogens, it is prudent to undertake the disinfection of intake water, for most of the bacteria found belong to the Enterobacteriaceae family, widely dispersed in nature and known to inhabit the faeces of both humans and animals, as well as water, soil, plants, plant materials, insects, and dairy products68,69. Hence, it is conceivable that these bacteria may be transmitted to the culture units through water intake. Acinetobacter, a significant nosocomial pathogen causing severe infections in humans, has been sporadically reported as a fish pathogen49. Furthermore, fish may serve as a notable reservoir of these zoonotic pathogens, enabling the transmission of pathogen to humans51 if the fishes were consumed without cooking properly. A substantial portion of the bacteria isolated in this study is of heterotrophic origin, emphasizing the need of maintaining optimal conditions within the system to ensure the high health status of the cultured organisms. Among the other bacterial species identified in this research belongs to Paenibacillaceae and Bacillaceae families. The pathogens discussed in this paper represent the occurrence of Enterobacteriaceae (50%), Paenibacillaceae (25%), Moraxellaceae (16.6%), and Bacillaceae (8.3%), in a biofloc-based A. testudineus fish farming system. Moreover, this study identified P. azoreducens, C. werkmanii, A. seifertii, and A. nosocomialis as fish pathogens, which are generally not known to cause diseases in fishes. However, they are pathogenic to humans and may be associated with an increasing array of human afflictions. Clinical isolates from these taxonomic groups were characterized, and phenotypic investigations were conducted to shed light on their distinct enzymatic virulence features.

The relentless transmission of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria to individuals via the Enterobacteriaceae group has persistently captivated attention70,71. This phenomenon has also been recognized as a foremost concern regarding public health and disease, particularly in relation to intestinal pathogens15. The isolates in this study exhibited a remarkable resilience against clindamycin and bacitracin (91.6%), cefoxitin (83.3%), cefalexin (50%), and lesser but still notable resistance to trimethoprim, chloramphenicol, neomycin, oxytetracycline, and nitrofurantoin (33.3%). These distinct resistance patterns observed among various biofloc bacteria suggest the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer, underscoring the urgency to screen bacteria harboring antimicrobial resistance genes within biofloc systems. This screening assumes heightened significance since these systems are typically shielded from usage of antibiotics due to the prevailing dominance of the heterotrophic bacterial community.

The virulence capacity of a bacterium is intrinsically linked to the diversification of enzymes and toxins synthesized by the strain17. Gelatinase causes tissue damage and help in invasiveness and infection establishment by overcoming host defences72. DNase may be involved in biofilm development and bacterial proliferation, as well as assisting microbes in evading the immune system. Amylase is largely responsible for bacterial nutrition and metabolism. Lipases play an essential role in invasion and establishment of infection73. Slime production helps the microorganisms to attach to specific host tissues72. Most of the isolated bacterial isolates exhibited conspicuous phenotypic exhibitions of virulence factors and were presented in Table 4. Koch’s postulates of the isolated pathogenic bacteria will be performed in future studies in the laboratory to determine their pathogenic potential emphasizing their relevance to fisheries and aquaculture.

Finally, reverse zoonosis where human-associated pathogens infect non-human animals, has been observed and isolation of the pathogens like Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter spp. was done during present investigation. The notion of reverse zoonosis was assumed based on available literature and the potentiality of these bacteria to cause disease in human population74,75. Among these remarkable occurrences, one exemplar of note involves the illustrious progeny of Enterobacteriaceae lineage and the formidable nosocomial entity Acinetobacter, notorious for its affliction upon the human populace. Recent scientific endeavours have illuminated a concerning finding: these microbial agents, hitherto known solely for their pathogenecity in humans, harbor the potential to inflict substantial harm upon piscine communities43,46,69, thereby engendering pernicious effects for aqueous ecosystems. The transmission of these pathogens from human sources to fish signifies a concerning reversal of the traditional direction of zoonotic infections with urgent need of concern by scientific community. Recent studies provide growing evidence of the potential for cross-transmission of opportunistic human pathogens to aquatic animals, particularly in systems with poor biosecurity such as biofloc-based aquaculture. Dekić et al.76 demonstrated that Acinetobacter baumannii, a clinically significant human pathogen, can successfully colonize freshwater fish (Poecilia reticulata) following artificial exposure to bacterial concentrations above 3 log CFU mL⁻¹. Colonization occurred within 24 h of contact, indicating a substantial public health risk and supporting the potential for reverse zoonotic events under certain environmental conditions. Furthermore, the epidemiological link between humans and the environment is reinforced by Houang et al.77 provided strong evidence of cross-transmission of Acinetobacter strains among hospital patients and between patients and environmental reservoirs. This highlights the adaptability of A. baumannii and its ability to persist across diverse ecological niches, including aquaculture environments. Gheorghe-Barbu et al.78 conducted a comprehensive analysis of A. baumannii in aquatic systems, identifying its presence in both water and fish microbiota. Their findings underscore the environmental persistence and adaptability of this pathogen in aquatic ecosystems, thus supporting its potential role as an emerging threat in aquaculture and a convergence point for human and animal health concerns. These studies support the hypothesis that human-associated multidrug-resistant bacteria, such as Acinetobacter baumannii, can enter aquaculture systems, establish colonization in fish, and potentially pose both animal and public health risks. These findings justify further investigation into the reverse zoonosis pathway, particularly in closed or semi-closed systems like biofloc where human interaction is frequent and biosecurity may be lacking.

The presence of Enterobacteriaceae in the biofloc aids in the protein-synthesis by breakdown of nitrogenous waste and organic residue79,80 Numerous studies conducted extensive research on the bacteria in BFT. Inadequate maintenance of biofloc systems may lead to pathogen proliferation, increasing the susceptibility of fish and prawns to disease. According to a study conducted by Hostins, the risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus causing Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND) in Litopenaeus vannamei is reduced by managing C/N ratio in biofloc systems81. The Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia) were reared under biofloc with different C: N ratios (C: N12, C: N15, and C: N20) and the inclusion of jaggery-as carbon source offered lower cumulative mortalities and better production after experimental challenge with A. hydrophila as compared to control82. Compared to normal aquaculture, biofloc based systems promote higher shrimp growth rates and better water quality due to the presence of biofloc, which is essentially a microbial community83. Biofloc systems may promote efficient and sustainable aquaculture by sustaining a resilient microbial ecology and superior water quality16.

Conclusion

This research highlights the critical need to manage the pre-treatment of intake water and good husbandry practices for biofloc culture to ensure the removal of pathogenic bacterial contaminants, particularly human-associated bacteria like Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacter spp., which have now been implicated in disease transmission within biofloc environments via the intake waters. Signs of stress or sickness in organisms may indicate the presence of pathogenic bacteria. The study underscores the importance of addressing reverse zoonosis to protect both human and animal health while maintaining ecological balance. As biofloc technology gains traction as a sustainable aquaculture solution, the findings of this study hold significant implications for its safe and widespread adoption with economic benefit. Consistent assessment of the microbial community in BFT is similarly important, accompanied by a concerted attempt to minimise the populations of Vibrio and Enterobacter. Consistent introduction of probiotic bacteria from reputable sources into the BFT system by inoculation may promote the proliferation of beneficial flocculating bacteria that inhibit the growth of pathogenic microbes. Moving forward, comprehensive efforts to understand the pathogenic potential of the isolated bacteria, including their extracellular enzymes, virulence genes, and serological properties, are crucial. This knowledge will be instrumental in developing effective disease management strategies, including targeted therapies and vaccination protocols. Monitoring water quality closely is a valuable indicator of when the microbial population ceases to facilitate the efficient functioning of the system. Future research should also prioritize the enhancement of biosecurity measures, emphasizing the importance of maintaining optimal water quality through regular monitoring of parameters like dissolved oxygen, ammonia, nitrite, and pH. Proper aeration, effective biofloc management, and timely water exchange, combined with quarantine practices of diseased cultured fish, will help minimize the bacterial load and prevent disease outbreaks. Collaboration among farmers, researchers, and industry stakeholders is essential to safeguard the long-term viability and sustainability of biofloc-based aquaculture systems.

Data availability

The sequence data generated during the current study have been submitted to GenBank under the accession number(s) OP218088 to OP218099. These data are publicly available at the NCBI GenBank database.

References

Kim, B. F. et al. Country-specific dietary shifts to mitigate climate and water crises. Glob Environ. Change. 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.010 (2020).

FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Rome https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en (2020).

Emerenciano, M. et al. Biofloc technology (BFT): a review for aquaculture application and animal food industry. Biomass now-cultivation Utilization. 12, 301–328. https://doi.org/10.5772/53902 (2013).

Basumatary, B. et al. Global research trends and performance measurement on Biofloc technology (BFT): a systematic review based on computational techniques. Aquac Int. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-023-01162-z (2023).

Moriarty, D. J. The role of microorganisms in aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture 151, 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(96)01487-1 (1997).

Naylor, R. L. et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature 405, 1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.1038/35016500 (2000).

Avnimelech, Y. & Kochba, M. Evaluation of nitrogen uptake and excretion by tilapia in bio Floc tanks, using 15 N tracing. Aquaculture 287, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.009 (2009).

Kasan, N. A. Application of Biofloc in aquaculture: an evaluation of flocculating activity of selected bacteria from Biofloc. In Beneficial Microorganisms in agriculture, Aquaculture and Other Areas 165–182 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Manan, H. et al. Identification of Biofloc microscopic composition as the natural bioremediation in zero water exchange of Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, culture in closed hatchery system. Appl. Water Sci. 7 (5), 2437–2446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-016-0421-4 (2017).

Kasan, N. A. et al. Isolation of potential bacteria as inoculum for Biofloc formation in Pacific whiteleg Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei culture ponds. Pak J. Biol. Sci. 20 (6), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2017.306.313 (2017).

Kumar, K. et al. Association of Enterobactercloacae in the mortality of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878) reared in culture pond in Bhimavaram, Andhra Pradesh, India. Indian J. Fish. 60, 147–149 (2013).

Debnath, C. et al. Economics of fish farming in Tripura. Indian J. Hill Farming. 23, 21–33 (2018).

Defoirdt, T. Implications of ecological niche differentiation in marine bacteria for microbial management in aquaculture to prevent bacterial disease. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005843 (2016).

Cheng, C. H. et al. Effects of ammonia exposure on apoptosis, oxidative stress and immune response in pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus). Aquat. Toxicol. 164, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.04.004 (2015).

Dash, P. M. et al. A study on ground reality of freshwater fish farming in Biofloc tank in West Bengal, India. J. Inland. Fish. Soc. India. 53, 132–142 (2021).

Akange, E. T. et al. Swinging between the beneficial and harmful microbial community in Biofloc technology: A paradox. Heliyon 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25228 (2024).

Mazumder, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of two virulent aeromonads associated with haemorrhagic septicaemia and tail-rot disease in farmed climbing perch Anabas testudineus. Sci. Rep. 11, 5826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84997-x (2021).

APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater 21st edn (APHA- AWWA-WPCF, 2005).

MacFaddin, J. F. Biochemical Tests for Identification of Medical Bacteria (Williams and Wilkins, 2000).

Austin, B. et al. Bacterial fish pathogens: disease of farmed and wild fish. Dordrecht, Netherlands (2007).

McDevitt, S. Methyl red and voges-proskauer test protocols. A Soc. Microbiol (2009). https://asm.org/protocols/methyl-red-and-voges-proskauer-test-protocols

Rainey, F. A. et al. The genus nocardiopsis represents a phylogenetically coherent taxon and a distinct actinomycete lineage: proposal of Nocardiopsaceae fam. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. 46, 1088–1092. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-4-1088 (1996).

Fredricks, D. N. et al. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl. J. Med. 353, 1899–1911. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043802 (2005).

Sambrook, J. et al. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold spring harbor laboratory press. (2nd ed.) Cold Spring harbor laboratory press. (1989). https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19901616061

Baker, G. C. et al. Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J. Microbiol. Methods. 55, 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2003.08.009 (2003).

Frank, J. A. et al. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2461–2470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (2008).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 (1987).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2021).

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01731581 (1980).

Bauer, A. W. et al. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 45, 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/45.4_ts.493 (1966).

Schmidt-Ott, K. M. et al. Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated Lipocalin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 407–413. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2006080882 (2007).

Shameena, S. S. et al. Virulence characteristics of Aeromonas veronii biovars isolated from infected freshwater goldfish (Carassius auratus). Aquaculture 518, 734819. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734819

Anguita, J. et al. Purification, gene cloning, amino acid sequence analysis, and expression of an extracellular lipase from an Aeromonas hydrophila human isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 2411–2417. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.59.8.2411-2417.1993 (1993).

Huys, G. et al. Genotypic diversity among Aeromonas isolates recovered from drinking water production plants as revealed by AFLPTM analysis. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 19 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80073-7 (1996). 428 – 35.

Koneman, E. W. et al. Diagnostic microbiology. The Nonfermentative gram-negative Bacilli (Lippincott-Raven, 1997).

Subashkumar, R. et al. Occurrence of Aeromonas hydrophila in acute gasteroenteritis among children. Indian J. Med. Res. 123, 61 (2006).

Brenner, D. J. et al. Classification of procaryotic organisms and the concept of bacterial speciation, in bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Springer 27–32 (2005).

Pękala-Safińska, A. Contemporary threats of bacterial infections in freshwater fish. J. Vet. Res. 62, 261–217. https://doi.org/10.2478/jvetres-2018-0037 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Regulation of growth, intestinal microbiota, non-specific immune response and disease resistance of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka) in Biofloc systems. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 77, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2018.03.053 (2018).

Van Doan, H. H. et al. Dietary inclusion of chestnut (Castanea sativa) polyphenols to nile tilapia reared in Biofloc technology: impacts on growth, immunity, and disease resistance against Streptococcus agalactiae. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 105, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2020.07.010 (2020).

Kumar, V. et al. Biofloc Microbiome with bioremediation and health benefits. Front Microbiol. 12, 741164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.741164 (2021).

Thillai Sekar, V. et al. Involvement of Enterobacter cloacae in the mortality of the fish, Mugil cephalus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02365.x (2008). 667 – 72.

Purivirojkul, W. Application of probiotic bacteria for controlling pathogenic bacteria in Fairy shrimp Branchinella Thailandensis culture. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 13. https://doi.org/10.4194/1303-2712-v13_1_22 (2013).

Wendy, F. T. et al. Enterobacter ludwigii, a candidate probiont from the intestine of Asian Seabass. J. Sci. Technol. Tropics. 10, 5–14 (2014).

Mardaneh, J., Dallal, M. M. & Isolation and identification Enterobacter asburiae from consumed powdered infant formula milk (PIF) in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Acta. Med. Iran 54, 39–43 (2016).

Vaneechoutte, M. et al. Identification of acinetobacter genomic species by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.33.1.11-15.1995 (1995).

Nemec, A. et al. Acinetobacter seifertii sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolated from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65, 934–942. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.000043 (2015).

Cosgaya Castro, C. et al. Acinetobacter dijkshoorniae sp. nov., a new member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex mainly recovered from clinical samples in different countries. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 5, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001318 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Isolation, identification and characterisation of an emerging fish pathogen, Acinetobacter pittii, from diseased loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) in China. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 113, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-019-01312-5 (2020).

Kishii, K. et al. The first cases of human bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter seifertii in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 22, 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2015.12.002 (2016).

Benoit, T. et al. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex prevalence, spatial-temporal distribution, and contamination sources in Canadian aquatic environments. Microbiol. Spect. 12 (10), e01509–e01524. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01509-24 (2024).

Yu, S. et al. A study on prevalence and characterization of Bacillus cereus in ready-to-eat foods in China. Front. Microbiol. 10, 3043. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.03043 (2020).

Jeßberger, N. et al. From genome to toxicity: a combinatory approach highlights the complexity of enterotoxin production in Bacillus cereus. Front. Microbiol. 6, 560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00560 (2015).

McDowell, R. H. et al. Bacillus cereus. StatPearls. (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459121/

Gopal, N. et al. The prevalence and control of Bacillus and related spore-forming bacteria in the dairy industry. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1418. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01418 (2015).

Velmurugan, S. et al. Bacterial white patch disease caused by Bacillus cereus, a new emerging disease in semi-intensive culture of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 444, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.03.017 (2015).

Vidal, J. et al. Probiotic potential of Bacillus cereus against Vibrio spp. In post-larvae shrimps. Revista Caatinga. 31, 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252018v31n226rc (2018).

Ranieri, M. L. et al. Real-time PCR detection of Paenibacillus spp. In Raw milk to predict shelf life performance of pasteurized fluid milk products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5855–5863. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01361-12 (2012).

Meehan, C. et al. Paenibacillus Azoreducens sp. nov., a synthetic Azo dye decolorizing bacterium from industrial wastewater. Int. J. Sys Evol. Micro. 51, 1681–1685. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-51-5-1681 (2001).

Geetha, I. & Manonmani, A. M. Surfactin: a novel mosquitocidal biosurfactant produced by Bacillus Subtilis ssp. Subtilis (VCRC B471) and influence of abiotic factors on its pupicidal efficacy. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02912.x (2010).

Ahsan, M. K. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Bacteria from Diseased Farm Fish. Dissertation, University of Rajshahi (2015).

Almeida, J. et al. A report on novel mosquito pathogenic Bacillus Spp. Isolated from a beach in Goa, India. (2014). http://irgu.unigoa.ac.in/drs/handle/unigoa/6071

Janda, J. M. et al. Biochemical identification of citrobacteria in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 1850–1854. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.32.8.1850-1854.1994 (1994).

Lü, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of Citrobacter spp. from the intestine of grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idellus. Aquaculture 313, 156 – 60. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.01.018

Junior, G. B. et al. Citrobacter freundii infection in silver catfish (Rhamdia quelen): hematological and histological alterations. Microb. Pathog. 125 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.09.038 (2018). 276 – 80.

Pan, L. et al. The novel pathogenic Citrobacter freundii (CFC202) isolated from diseased crucian carp (Carassius auratus) and its ghost vaccine as a new prophylactic strategy against infection. Aquaculture 533, 736190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736190 (2021).

Aly, S. M. et al. Bacteriological and histopathological studies on Enterobacteriaceae in nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2, 94–104 (2012).

Elsherief, M. F. et al. Enterobacteriaceae associated with farm fish and retailed ones. Alex J. Vet. Sci 42. (2014).

Sreedharan, K. et al. Characterization and virulence potential of phenotypically diverse Aeromonas veronii isolates recovered from moribund freshwater ornamental fishes of Kerala, India. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 103, 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-012-9786-z (2013).

Lilenbaum, W. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococci isolated from the skin surface of clinically normal cats. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 27, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-765X.1998.00406.x (1998).

Beaz-Hidalgo, R. & Figueras, M. J. Aeromonas spp. Whole genomes and virulence factors implicated in fish disease. J. Fish. Dis. 36, 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfd.12025 (2013).

Timpe, J. M. et al. Identification of a Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane protein exhibiting both adhesin and lipolytic activities. Infect. Immun. 71, 4341–4350. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.71.8.4341-4350.2003 (2003).

Visca, P. et al. Acinetobacter infection–an emerging threat to human health. IUBMB Life. 63 (12), 1048–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.534 (2011).

Moreira de Gouveia, M. I. et al. Enterobacteriaceae in the human gut: dynamics and ecological roles in health and disease. Biology 13 (3), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13030142 (2024).

Dekić, S. et al. Emerging human pathogen acinetobacter baumannii in the natural aquatic environment: a public health risk? Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 28 (3), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2018.1472746 (2018).

Houang, E. T. et al. Epidemiology and Infection control implications of acinetobacter spp. In Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 (1), 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.39.1.228-234.2001 (2001).

Gheorghe-Barbu, I. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii’s journey from hospitals to aquatic ecosystems. Microorganisms 12 (8), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12081703 (2024).

Ayazo-Genes, J. et al. Describing the planktonic and bacterial communities associated with Bocachico prochilodus Magdalenae fish culture with Biofloc technology. Rev MVZ Cordoba. 24 (2), 7209–7217. https://doi.org/10.21897/rmvz.1648 (2019).

Steenackers, H. et al. Salmonella biofilms: an overview on occurrence, structure, regulation and eradication. Food Res. Int. 45 (2), 502–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.01.038 (2012).

Hostins, B. et al. Managing input C/N ratio to reduce the risk of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) outbreaks in Biofloc systems-A laboratory study. Aquaculture 508, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.04.055 (2019).

Elayaraja, S. et al. Potential influence of jaggery-based Biofloc technology at different C: N ratios on water quality, growth performance, innate immunity, immune-related genes expression profiles, and disease resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 107, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2020.09.023 (2020).

Hosain, M. et al. (ed, E.) Effect of salinity on growth, survival, and proximate composition of macrobrachium Rosenbergii post larvae as well as zooplankton composition reared in a maize starch based Biofloc system. Aquaculture 533 736235 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736235 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge “National Surveillance Programme for Aquatic Animal Diseases (NSPAAD)” Phase-II project under the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana (PMMSY) for providing financial support to execute the work. The first author is extremely grateful to University Grant Commission, New Delhi, India for providing fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C. performed investigation, validation, visualization, data curation, writing original draft; M.P. edited manuscript, R.D. critically revised the manuscript; D.D. performed data curation; H.S. design the experiment, supervised, review & editing; and T.C. validated the result.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chouhan, N., Pavankalyan, M., Devi, R. et al. Emergence of human associated bacterial pathogens in Anabas testudineus reared in freshwater Biofloc systems. Sci Rep 15, 36747 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20611-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20611-8