Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) remains incurable, as most patients relapse or become refractory (RRMM), and the molecular nexus among clonal evolution, immune escape and therapy response remains unknown. Bulk RNA-seq from 24 MM to 6 matched marrows (subset of 132) plus single-cell datasets were analysed by differential expression, pseudotime, WGCNA, enrichment, immune deconvolution and GDSC drug screens. PRKD2 was knocked down (KD) or over-expressed (OE) in H929, 8226 and U266 cells. Viability (CCK-8) and apoptosis (Annexin V/7-AAD) were assessed after 48 h of axitinib (1.25–10 µM). PRKD2 was the sole gene uniformly up-regulated in newly diagnosed MM, RRMM and poor-survival cohorts, rising along the malignant plasma-cell trajectory. High PRKD2 aligned with ISS-III stage, elevated mRNAsi/EREG_mRNAsi and worse 5-year survival (38% vs. 73%, P = 0.012). PRKD2-KD reduced proliferation (~ 30%) and restored HLA-E, whereas PRKD2-OE suppressed antigen-presentation genes and polarised macrophages toward an IL-6/MERTK tumour-promoting phenotype. PRKD2-high marrow contained more naïve/memory B cells but fewer mature plasma cells. PRKD2 expression correlated positively with axitinib sensitivity (– log10 IC50, r = 0.68; P < 0.001). Experimentally, PRKD2-OE cells showed a 1.4-fold increase in axitinib-induced apoptosis, while PRKD2-KD cells were intrinsically pro-apoptotic and further sensitised; axitinib abolished the growth advantage conferred by PRKD2-OE. PRKD2 integrates secretory stress, stem-like programmes and immune evasion, driving aggressive MM yet exposing a vulnerability to VEGFR/PDGFR blockade. Direct PRKD2 targeting or axitinib-based combinations—including proteasome inhibition—deserve clinical evaluation for high-risk MM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM), also called plasma cell myeloma, is an incurable plasma cell malignancy and one of the most common malignant hematological diseases1. It is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow, leading to a series of complications such as anemia and fatigue, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, and increased susceptibility to infection2,3. Although various therapeutic methods have been developed to hinder the progression and exacerbation of MM, such as high-dose chemotherapy, autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and gene therapy4,5, strong side effects and the presence of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) in some patients persist6; For RRMM, prognosis remains challenging, and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) are still difficult to extend7,8. Therefore, MM, especially RRMM, remains a clinical challenge.

RRMM refers to the later stage of MM, where those malignantly mutated plasma cells further infiltrate and become nonresponsive and resistant to formerly efficacious treatments9. While the etiology of RRMM has not been fully understood, genetic abnormalities are believed to be the fundamental drivers facilitating the malignant mutations of plasma cells in the bone marrow, leading to the dysregulation of downstream signaling pathways including the NF-kB pathway, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and JAK/STAT pathway10. Meanwhile, myeloma cells proliferate uncontrollably and suppress other cell types in the bone marrow, such as normal plasma cells, osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and immune cells, exacerbating the bone marrow microenvironment and accelerating osteolytic lesions10. In addition, myeloma cells gradually gain the ability to evade immune surveillance, involving the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1, the production of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and the induction of regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells11. This primes drug resistance and constitutes the primary challenge for the treatment of RRMM. Therefore, it is imperative to identify new therapeutic targets and design new drugs to block the exacerbation of RRMM and improve OS and PFS for RRMM patients.

Serine/threonine-protein kinase D2 is an enzyme encoded by the PRKD2 gene in humans, belonging to the protein kinase D family, which is a group of serine/threonine kinases that play important roles in various cellular processes12. Previous research has shown that PRKD2 has a potential role in various cancer types, exhibiting aberrant expression in breast cancer13, prostate cancer14 and pancreatic cancer15. PRKD2 promotes tumor cell proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis through its effects on downstream signaling pathways and transcriptional regulation16. Specifically, mutations in PRKD2 have been found to disrupt downstream events in CD4 + T cells and T follicular helper cells, which play a crucial role in providing signals to B cells to initiate immune responses, suggesting a potential link between PRKD2 and B cell physiological functions17. Furthermore, inhibition of protein kinase D2 has been shown to reduce tumor growth in pancreatic cancer by downregulating the production of interleukin 35 (IL-35) in regulatory B cells18. These findings lead us to consider a possible association between PRKD2 and MM. Particularly, considering that plasma cells belong to the B cell family and that dysregulation of plasma cells is one of the primary reasons for the occurrence of MM, there has been little research emphasizing the regulatory role of PRKD2 in the pathogenesis of MM.

Based on these findings, we have initiated a project to explore if and how PRKD2 functions in the initiation of MM. Additionally, we aim to investigate whether new medicines can target PRKD2 to potentially mitigate the development and progression of MM or RRMM.

Methods

Patients

We analyzed 132 multiple myeloma (MM) patients at various stages, treated at the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, and Suzhou Medical College of Soochow University from August 3, 2022, to July 30, 2023. All diagnoses were confirmed via bone marrow aspiration, and patients provided informed consent. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Soochow University and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample collection and RNA-seq analysis

Bone marrow samples were collected and preserved in RNA-specific storage solution. Approximately 20–30 ng of mRNA per sample was extracted and used to construct RNA-seq libraries with the KAPA Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit (Illumina platform). Paired-end sequencing (HiSeq-PE150) was then performed. In total, raw data for 30 patient samples were deposited in GEO (GSE268395).

Transcriptomic data, and clinical information of TCGA and GEO database

We obtained 30 RNA-seq samples (MM and healthy controls) from the TCGA database (accessed April 23, 2024). Additionally, we retrieved 559 MM cases from GEO (GSE24080: Dead vs. Alive) for validation. Data included parameters such as age, gender, and ISS stage, with the median value used for data classification.

Single-cell RNA-seq pre-processing and cell-type annotation

Raw FASTQ files of HD (n = 5), MGUS (n = 6), SMM (n = 4) and MM (n = 4) samples (GSE271107) were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome (Ensembl release 109) with Cell Ranger 7.2.0 using default chemistry detection. Unfiltered gene-barcode matrices were imported into Seurat v5.0.1 (R 4.3.3), and droplets were retained if they expressed ≥ 200 genes, ≤ 6 000 genes and had < 15% mitochondrial UMIs, thresholds chosen after visual inspection of knee plots (Fig S1A). Genes detected in fewer than three cells were discarded. Library size differences were normalised with SCTransform (method = “glmGamPoi”, vars.to.regress = c (“percent.mt”, “S.Score”, “G2M.Score”)), followed by principal-component analysis on the top 3000 variable features. Batch effects arising from donor, platform (10 × 3′ v3 vs. v4) and capture date were mitigated with Harmony v1.0 (theta = 2, lambda = 0.1); the first 30 Harmony components were carried forward to construct a shared nearest-neighbour graph (k = 30). Unsupervised clustering employed the Leiden algorithm (resolution = 0.8), and two-dimensional visualisation used UMAP (min.dist = 0.3).

Initial cell identities were assigned automatically with SingleR v2.2 against the Human Primary Cell Atlas, and concordance was cross-checked with the Monaco Immune reference. Cluster-specific marker genes were then refined by Seurat’s FindAllMarkers (log2FC > 0.25, adjusted p < 0.01, min.pct = 0.20). When automatic and marker-based annotations disagreed, manual curation relied on canonical markers—for example, over-expression of IRF4, PRDM1, XBP1 (malignant plasma cells). CD3D, TRAC (T cells); MS4A1, CD79A (B cells); SDC1, IRF4 (plasma cells); LYZ, S100A8 (myeloid); and KIT, MPO (progenitors). Putative doublets were flagged with DoubletFinder v2.0.3 (expected rate = 7.5%) and removed. The final annotated object comprised 181,462 high-quality cells spanning healthy donor (HD), MGUS, SMM and MM samples.

Figure S2A–C compares three gene-selection strategies for Monocle pseudotime. Seurat variable genes (2000; 1948 high-dispersion hits) and cluster DEGs (1523 hits) captured canonical plasma-cell signals, whereas an empirical Monocle filter (mean ≥ 0.1 UMI; dispersion ≥ fit) retained 1 847 transcripts spanning stress-adaptation, metabolic and signalling pathways. Because all three lists generated nearly identical topologies (branch-assignment r > 0.92) but the empirical set offered the broadest coverage, it was chosen for downstream analysis, optimising sensitivity to stage-specific inflection points linked to PRKD2 induction (Fig. S2A–C).

Pseudotime reconstruction and branch analysis

Seurat objects were converted to Monocle 2 v2.24.1. Ordering genes were defined with an empirical filter (mean ≥ 0.1 UMI; dispersion ≥ fitted value), giving 1 847 genes. Dimensionality reduction used DDRTree (dims = 30) and the root node was set to healthy plasma cells. Branch-dependent genes were identified with BEAM (q < 1 × 10−4) and visualised as heat maps to define fate-specific modules.

Stemness indices (mRNAsi and EREG-mRNAsi)

We quantified stemness with the one-class logistic-regression (OCLR) weight matrix of Malta et al. using gelnet v1.2.119. For bulk RNA-seq (24 MM + 6 controls and GSE24080), log2(FPKM + 1) values were correlated with the OCLR weights to generate the mRNA expression-based stemness index (mRNAsi), then linearly rescaled to 0–1 (higher = more stem-cell-like). To capture epigenetically sustained stemness, genes annotated as epigenetically regulated were removed and the same procedure repeated, yielding EREG-mRNAsi on the same 0–1 scale. The identical weight vector was applied to single-cell data via AddMetaData in Seurat, allowing cell-level mRNAsi/EREG-mRNAsi scores to be correlated with PRKD2 expression throughout the manuscript.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

The 3000 most variable genes from 30 bulk samples were log2-transformed and analysed with WGCNA v1.72-1. A soft threshold β = 8 (scale-free R2 ≈ 0.9) produced the adjacency matrix, which was converted to a TOM; modules were defined with minModuleSize = 30 and mergeCutHeight = 0.25. Module eigengenes were correlated with mRNAsi and EREG_mRNAsi (|r| > 0.3; P < 0.01). Hub genes were those with Module Membership > 0.8 and Gene Significance > 0.4, identifying PRKD2 as the top node. Module genes were functionally annotated with clusterProfiler v4.8.2 (FDR < 0.05).

PRKD2 mutation in MM cell lines

To generate PRKD2 knockout (KO) and overexpression (OE) MM cell lines were created and delivered via lentiviral vectors. Transduced cells underwent antibiotic selection or FACS sorting.

Western blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with 1 × protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and clarified by centrifugation (14,000 g, 15 min, 4 °C). Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA assay, and 20 µg of each sample were resolved on 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gels, followed by wet transfer to PVDF membranes (0.45 μm). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBST and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following Abcam primary antibodies: anti-PKD2/PRKD2 [EP1495Y] (ab51250, 1:1000) and anti-β-actin (loading control, ab8226, 1:1000). After three washes in TBST, membranes were incubated for 1 h with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L secondary antibody (ab97051, 1:10,000). Bands were visualised using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent and imaged on a Chemidoc MP system; band intensities were quantified with ImageJ and normalised to β-actin.

Cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) cell proliferation/viability assay

CCK-8 assays (Dojindo, Cat. #CK04-05) were performed on three 8226 cell groups (PRKD2 knockdown, overexpression, and vector controls). Cells were seeded in multi-well plates and incubated with CCK-8 reagent at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. Absorbance at 450 nm indicated cell viability. Results were expressed as the proliferation ratio compared to vector controls.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA (0.5 µg) was extracted from freshly isolated bone-marrow mononuclear cells with TRIzol™, DNase-treated, and reverse-transcribed using the iScript™ cDNA kit (Bio-Rad). Gene-specific primers for HRAS, HSP90B1, RNASE2, VCAN and the reference gene GAPDH were designed in Primer-BLAST and validated for single-peak melt curves (sequences in Table S1). qPCR was performed in triplicate on a CFX96 Touch (Bio-Rad) using SsoAdvanced™ SYBR Green master mix under standard cycling (95 °C × 30 s; 40 × [95 °C × 5 s, 60 °C × 30 s]). Relative expression was calculated as 2−ΔCt (ΔCt = Ct_target – Ct_GAPDH). Group means ± SD were compared with two-tailed Student’s t-tests; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Pathway and functional analysis

Using “DESeq2” in R, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PRKD2-High and PRKD2-Low groups, with a threshold of |log2 fold change| > 1 and false discovery rate < 0.05. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed with “clusterProfiler,” “org.Hs.eg.db,” and “enrichplot,” highlighting key functional pathways related to PRKD2. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed with clusterProfiler, using KEGG pathway definitions20,21,22.

Estimation of tumor-Infiltrating immune cells

We employed ssGSEA in R to estimate tumor-infiltrating immune cell populations in relation to PRKD2 expression. Heat maps illustrated infiltration levels and functional features of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting potential links between PRKD2 and immune responses.

Immune deconvolution

Bulk-RNA profiles were deconvoluted with CIBERSORTx (v1.1, Stanford University) to estimate relative abundances of 22 immune cell phenotypes. Raw counts were normalised to transcripts-per-million (TPM), quantile-normalised within CIBERSORTx, and analysed against the LM22 reference signature matrix with 1000 permutation runs to obtain empirical P values. The “batch-mode” option was enabled to remove technical variation across datasets, and the S-mode (“single-cell”) correction was applied when single-cell–derived mixtures were included. Only samples with deconvolution P < 0.05 were retained for downstream statistics. All CIBERSORTx outputs were parsed in R 4.3.3 using the packages tidyverse, data.table, and ggpubr; Spearman correlations between PRKD2 expression and inferred cell fractions were adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini–Hochberg method (false-discovery rate < 0.05).

Drug sensitivity assessment

The semi-inhibitory concentration (IC50) for chemotherapeutic drugs was calculated with the “pRRophetic” package. We focused on differences in IC50 between PRKD2-High and PRKD2-Low groups, particularly for axitinib. Statistical significance was evaluated by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and boxplots were generated with “ggplot2.”

Axitinib-induced apoptosis and proliferation assays

H929 myeloma cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37 °C with 5% CO2. PRKD2 knock-down (1965-KD) and over-expression (HOMO-OE) derivatives were generated by lentiviral transduction with shPRKD2 (TRCN0000001965) or pLV-CMV-PRKD2-3×Flag, respectively, while LV3 (shRNA empty) and LV5 (vector empty) served as matched controls; stably infected cells were selected in 1 µg mL−1 puromycin for 7 days and PRKD2 modulation was confirmed by qPCR and immunoblot. For drug treatment, log-phase cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells mL−1 in 24-well plates for apoptosis or 5 × 102 cells per well in 96-well plates for viability, then exposed for 48 h to axitinib (MedChemExpress, #HY-10052) at 1.25, 2.5, 5 or 10 µM; vehicle (0.1% v/v DMSO) served as the negative control, and all conditions were set up in biological triplicate. Apoptosis was quantified by staining harvested cells with FITC-Annexin V/7-AAD (BD Biosciences, #556547) for 15 min at room temperature, acquiring 10,000 events per sample on a BD FACSCanto II, and summing early (Annexin V+/7-AAD−) and late (Annexin V+/7-AAD+) fractions; data were analysed in FlowJo v10 and expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Viability was assessed by adding 10 µL Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (Dojindo, #CK04) to each well, incubating 2 h and reading absorbance at 450 nm on a BioTek Synergy H1, with results normalised to DMSO controls. Dose–response curves were analysed in GraphPad Prism 9 using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test, and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for group comparisons of age and ISS stage, followed by post hoc tests. All dichotomisations use the 75th percentile of PRKD2 TPM values unless specifically stated. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparing two groups of quantitative data. Prognostic modeling employed RStudio (version 4.3.2) with the packages “rms,” “ggplot2,” “risk regression,” “PredictABLE,” and “survminer.” Immune infiltration scores were assessed via the CIBERSORT package, and statistical significance was determined by t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, depending on data distribution.

Results

Single-cell landscape of myeloma evolution highlights PRKD2 as a stage-dependent hub gene

Integrated analysis of 181,462 high-quality bone-marrow cells from healthy donors (HD), MGUS, smouldering myeloma (SMM) and multiple myeloma (MM) resolved 20 transcriptionally distinct populations (Fig. 1A). Premalignant stages were marked by expansion of CD4+ T and FOXP3+ Treg subsets and early erythropoiesis, whereas cycling progenitors, pDCs and NK/NKT cells declined. A discrete “MM-malignant plasma” cluster emerged in MGUS, expanded through SMM, and dominated MM, indicating early malignant commitment (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1B). Deconvolution of the T-cell compartment uncovered stage-specific shifts that were obscured at the bulk CD4/CD8 level. Compared with healthy donors, MGUS marrow was enriched for naïve CD4 (3.8%) and cytotoxic CD8 (3.3%) subsets, whereas SMM showed the highest effector-memory CD4 (3.3%) and exhausted CD8 (1.5%) proportions. By overt MM, central-memory phenotypes dominated both lineages (CD4 3.5%, CD8 2.4%) and cytotoxic CD8 cells contracted to near-baseline, indicating functional redistribution rather than uniform expansion across disease progression (Fig S1C).

Single-cell atlas of myeloma progression pinpoints PRKD2 as a stage-linked hub. (A) UMAP coloured by 20 clusters; split panels show stages. Dashed circle highlights the plasma-cell region where an “MM-malignant plasma” cluster emerges in MGUS and expands through SMM to dominate MM. HD (n = 5), MGUS (n = 6), SMM (n = 4) and MM (n = 4). (B) Bar chart of mean cell-type frequencies per stage. (*P < 0.05, compared with HD) (C) Heat-map of normal plasma-cell DEGs; PRKD2 (red) rises stepwise HD→MM. Heat-map was drawn in R [v4.3.3] using ComplexHeatmap [v2.1] (Bioconductor; https://bioconductor.org/packages/ComplexHeatmap) from vst-normalized expression with per-gene z-scores. (D) Heat-map for MM-malignant plasma cells, showing further PRKD2 up-regulation plus stress/immune-evasion genes. Generated in R [v4.3.3] with ComplexHeatmap [v2.1] as in (C). (E) Box-scatter plots of mRNAsi and EREG_mRNAsi in bulk plasma cells (****P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon). (F) Same indices within the MM-malignant subset. (G) Feature-density UMAPs: PRKD2 signal (yellow) intensifies from HD to MM within plasma cells. (H–K) PRKD2 expression correlates with mRNAsi and EREG_mRNAsi; Points are coloured by clinical group (HD, MGUS, SMM, MM). Separate solid lines represent group-specific linear regressions with 95% confidence ribbons. An ANCOVA comparing the four slopes yields a significant group × PRKD2 interaction (F = 4.89, p = 0.003), indicating that the relationship between PRKD2 expression and stemness indices differs across disease stages. (L) iTALK network linking CD4+, CD8+, NK/NKT, normal and malignant plasma cells in MM; arrow width ∝ ligand–receptor counts. (M) Chord diagram of dominant MM-plasma/NK→CD4+ T signals; VCAN, HSP90B1, RNASE2 and HRAS target TLR2. PRKD2 expression in sending plasma cells scales with total TLR2 engagement.

Within the plasma-cell lineage, differential expression pinpointed PRKD2 as the most consistently up-regulated gene across the HD→MGUS→SMM→MM continuum (Fig. 1C,D). Stemness scoring mirrored this trajectory: both mRNAsi and EREG_mRNAsi rose stepwise from HD (~ 0.15) to MGUS, SMM and MM (~ 0.80–0.90) (Fig. 1E,F). Spatial UMAP mapping confirmed that PRKD2 induction is confined to plasma cells and intensifies to a high-density hotspot in MM (Fig. 1G). Correlated tightly with PRKD2 expression in bulk plasma cells (R2 = 0.599 for mRNAsi) and in MM-malignant plasma (R2 = 0.439; Fig. 1H–K). ANCOVA confirmed a significant group effect (interaction p = 0.003). These data position PRKD2 at the nexus of a stem-like transcriptional programme that unfolds during clonal evolution.

iTALK cell-communication analysis revealed MM-malignant plasma as the dominant signalling hub (466 ligand–receptor pairs), targeting CD4+ T cells via a VCAN/HSP90B1/RNASE2/HRAS–TLR2 axis (Fig. 1L,M). PRKD2 expression in ligand-producing plasma cells scaled with the cumulative strength of TLR2-directed interactions (Spearman ρ ≈ 0.60, P < 10−50), implicating PRKD2 in orchestrating the secretory programme that engages immunomodulatory TLR2 signalling. qPCR validation confirmed that HRAS, HSP90B1, RNASE2 and VCAN transcripts are all significantly up-regulated in primary MM samples (n = 6) compared with healthy bone-marrow controls (n = 6) (Fig S1D-S1G). For each gene the mean 2−ΔCt value in MM was two- to four-fold higher than in HD, with p < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t-test), reinforcing the transcriptomic prediction that PRKD2-high myeloma cells co-express these downstream effectors. Collectively, Fig. 1 establishes PRKD2 as a progressive, plasma-cell–restricted driver linked to stemness acquisition and T-cell crosstalk, underscoring its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target in myeloma progression.

PRKD2-driven rewiring of the plasma-cell trajectory

Monocle2 ordered 2137 plasma cells into a bifurcating graph with two branch nodes (Fig. 2A). In the stage-stratified pseudotime projection (Fig. 2B), plasma cells from healthy donors (HD) are located almost exclusively on the right-hand, lower quiescent branch. MGUS cells appear for the first time just above node 1 and extend slightly along the early malignant arm. SMM cells occupy a more distal segment of this branch, whereas multiple myeloma (MM) cells cluster on the far right and lower tip. Kernel-density plots of the same trajectory (Fig. 2C) corroborate this shift: the modal pseudotime for HD lies between 0 and 2, MGUS peaks at 6–10, and both SMM and MM peak beyond 10, illustrating a stepwise advance of plasma-cell states toward the terminus as disease progresses.

Pseudotime analysis uncovers a PRKD2-centred malignant branch. (A,B) Monocle2 principal graph of 2137 plasma cells (red = normal, cyan = MM-malignant). Branch nodes ① and ② split a quiescent upper arm from a malignant lower arm. (C) Same graph by clinical stage. Cells shift from root (HD) through MGUS and SMM to populate the malignant arm in MM; grey curves show stage-specific density along pseudotime. (D) Gene-smooths along pseudotime. Early regulators (BTG2, FOS/FOSB, CD79A) wane, ribosome/secretory genes (IGHG, IGHD/M, RPL29, RPS5/A) rise. PRKD2 climbs steadily, peaking where malignant cells accumulate. (E) BEAM heat-map of 278 branch genes. Module 1—up-regulated in malignant fate—contains PRKD2 with ribosome/ER genes (RPS5, RPL29); modules 2–4 house stress, Ig heavy- and light-chain signatures, respectively. BEAM analysis was performed with Monocle 2 [v2.3] (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle-release/) and the heat-map rendered in R [v4.3.3] using ComplexHeatmap [v2.1] (https://bioconductor.org/packages/ComplexHeatmap).

Along the malignant-plasma-cell pseudotime axis, PRKD2 rises steadily from early to late states. Three immediate-early genes—BTG2, FOS, and FOSB—track the same upward trajectory, indicating synchronous activation with PRKD2 during progression. In contrast, the B-lineage marker CD79A follows the opposite pattern, diminishing as PRKD2 increases. The remaining transcripts examined (e.g., immunoglobulin heavy chains, ribosomal components, alarmins) show no consistent monotonic trend and therefore appear unrelated to the PRKD2-centred evolutionary program (Fig. 2D,E).

Pathway enrichment along the malignant-plasma‐cell branch revealed a discrete, secretory–lysosomal programme. Compared with earlier stages, multiple-myeloma (MM) cells were specifically enriched for “N-glycan biosynthesis”, “Various types of N-glycan biosynthesis”, “Lysosome”, “Protein export”, “Phagosome”, “Antigen processing and presentation”, and “Epstein-Barr virus infection” pathways (Fig. S3). No other type (HD, MGUS or SMM) showed concurrent activation of this module, underscoring a unique dependence of MM cells on glycoprotein maturation, vesicular trafficking and antigen-handling machinery.

Clinical analysis

We collected clinical data from 132 patients diagnosed with or without MM. After grouping and preliminary analysis, significant differences were observed in both age (p = 0.018) and ISS stage (p = 0.001) variables, which could potentially affect the accuracy of data and reliability of results. To address these potential confounding factors and ensure a more balanced analysis, propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted to correct the ratio of different groups within the age and ISS stage variables to approximately 1:1:1, respectively. This approach effectively eliminated differences between different age groups and among different ISS stages, as shown in Table 1.

Stemness indices, survival, and a PRKD2-centred co-expression hub

After the correction by PSM, we assigned numbers to the matched patients and retrieved their total RNA from bone marrow samples from the database, which included 7 samples from patients in complete or partial remission (CR or PR), 8 samples from relapsed or refractory (RR) patients, and 9 samples from newly diagnosed (ND) patients. Additionally, we included an extra 6 samples from healthy individuals as the control group. All samples underwent RNA sequencing following retrieval. Upon obtaining the original data, spliced transcript alignment to a reference (STAR) was performed initially to exclude minor transcripts. Older patients (≥ 65 year) carried significantly higher mRNAsi and EREG_mRNAsi than younger individuals (median 0.75 vs. 0.53 and 0.62 vs. 0.46, respectively; P < 0.02) (Fig. 3A). Stemness rose further when samples were stratified by treatment status: newly diagnosed and, most strikingly, relapsed/refractory MM displayed much higher scores than complete/partial responders or non-myeloma controls (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). A step-wise increase across ISS stages I→III, with low values in MGUS/SMM (“other”), confirmed that stem-like programmes intensify as clinical burden worsens (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3C).

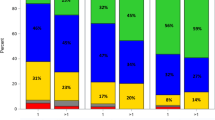

Stemness indices, clinical stratification, survival impact. mRNAsi and EREG-mRNAsi across patient stratifications. Box-plots show log-scaled indices after propensity-score matching (PSM). Older patients (≥ 65 year) harbour higher stemness than younger cases. (A) Scores further increase from complete/partial remission (CR/PR) through newly diagnosed (NDMM) to relapsed/refractory (RRMM) myeloma, with lowest values in healthy donors (HD). (B) A step-wise rise is also evident across ISS stages I→III, whereas MGUS/SMM (“Other”) remain low. (C) Kruskal–Wallis tests: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (D,E) Kaplan–Meier curves dichotomised at the cohort median. High-stemness myeloma exhibits inferior 5-year overall survival (mRNAsi: 38% vs. 73%, log-rank P = 0.012; EREG-mRNAsi: 36% vs. 70%, P = 0.063).

When patients were dichotomised at the cohort median, the mRNAsi-High group showed a 5-year overall-survival of 38% versus 73% in the mRNAsi-Low group (log-rank P = 0.012) (Fig. 3D); a similar, borderline-significant trend was seen for EREG_mRNAsi (36% vs. 70%, P = 0.063) (Fig. 3E). Thus, enrichment of stemness—previously localised to PRKD2-high malignant plasma cells in single-cell data—translates into inferior prognosis in bulk marrow.

Weighted gene-co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) partitioned the transcriptome into 31 colour modules (Fig. S4A). Module–trait mapping identified the royal blue eigengene as most correlated with mRNAsi and the blue eigengene with EREG_mRNAsi (Fig. S4B). Within the royal-blue cluster, intramodular connectivity correlated with gene significance for mRNAsi (r = 0.34) (Fig. S4C). An analogous relationship held for the blue module and EREG_mRNAsi (r = 0.42) (Fig. S4D). Functional annotation of both stemness-linked modules highlighted enrichment for ER protein-processing, proteasome, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and the MAPK/PI3K-Akt axis—the same secretory-stress, pro-survival circuitry that converged on PRKD2 in the single-cell atlas. Collectively, Fig. 3 establishes PRKD2 as the central node of a stemness-associated network that accompanies therapeutic resistance, advanced stage and poor survival in multiple myeloma.

PRKD2 emerges as a convergent DEG and ER-stress effector in multiple myeloma

Differential-expression analyses were performed with DESeq2 on three independent contrasts—newly diagnosis (NDMM) vs. control, relapsed/refractory (RR) vs. control, and GSE24080 dead vs. alive. A Venn diagram revealed 28 genes shared by all contrasts, placing PRKD2 at the numerical centre of overlap (Fig. 4A). Heat-map visualisation confirmed that PRKD2 expression was consistently higher in NDMM, RR and even CR/PR specimens than in healthy marrows (Fig. 4B), nominating it as a putative driver across the clinical spectrum of MM.

PRKD2 is a shared DEG and ER-stress effector in multiple myeloma. (A) Venn diagram of DESeq2 analyses (NDMM vs. HD, RRMM vs. HD, GSE24080 dead vs. alive) showing 28 common DEGs centred on PRKD2. (B) Heat-map of the 28 genes across control, CR/PR, NDMM and RRMM marrows; PRKD2 is up-regulated in every MM group. Bottom annotation bars carry numbered colour codes to aid cross-reference: 1 Group, 2 Age, 3 Gender, 4 MM type, 5 Durie–Salmon stage, 6 ISS stage. PRKD2 heads the list and shows strongest up-regulation in the RRMM samples. Heat-map generated in R [v4.3.3] with ComplexHeatmap [v2.1] (https://bioconductor.org/packages/ComplexHeatmap) from vst-normalized expression with per-gene z-scores. (C,D) Western blots validating PRKD2 knock-down (sh1641/2074/1965) and knock-up (cDNA-Homo) in H929, 8226, U266 cells; β-actin, loading control. (E) CCK-8 proliferation assay in 8226 cells: PRKD2 knock-down suppresses growth (0–72 h), over-expression has no consistent effect (mean ± SD, n = 9). (F) GO enrichment of ID DEGs: top terms cluster around unfolded-protein response, ER stress and chaperone activity. (G) KEGG enrichment of the same DEGs highlights ‘Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum’ and ‘Protein export’, linking PRKD2 to secretory-stress and pro-survival pathways (RRMM vs. CR). KEGG resource cited per guidelines: KEGG—Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that patients with high PRKD2 expression experienced faster disease progression. Although overall survival (OS) was shorter in the PRKD2-high group, the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.17; Fig. S5A). In contrast, progression-free survival (PFS) was markedly worse: PRKD2-high cases had a median PFS of 14 months (log-rank P = 0.0042; Fig. S5B). These data indicate that elevated PRKD2 is an adverse marker for early relapse, even within this propensity-matched cohort.

To test functional relevance, we engineered H929, RPMI-8226 and U266 cells with lentiviral shRNAs (knock-down) and cDNA (knock-up). Immunoblotting verified efficient silencing or over-expression of PRKD2 in all three lines (Fig. 4C) and in an independent bulk lysate (Fig. 4D). PRKD2 depletion attenuated 8226 proliferations over 72 h, whereas over-expression produced no consistent gain, likely owing to baseline saturation (Fig. 4E). CCK-8 assays in H929 (Fig. S6A) and U266 (Fig. S6B) mirrored the trend seen in RPMI-8226: PRKD2 knock-down modestly reduced proliferation, whereas PRKD2 over-expression produced a slight increase at 72 h; however, neither change reached statistical significance (P > 0.05). Gene-ontology enrichment of the NDMM DEG set mapped predominantly to unfolded-protein response, ER lumen trafficking and chaperone activity (Fig. 4F), while KEGG analysis highlighted “Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum” and “Protein export” (Fig. 4G). Collectively, Fig. 4 identifies PRKD2 as the key gene common to aggressive MM datasets, validates its capacity to modulate myeloma-cell growth, and connects its action to ER-stress and pro-survival kinase programs that constitute exploitable therapeutic targets.

PRKD2 reshapes the immune landscape toward a B-cell–biased, plasma-cell–suppressive milieu

In the PRKD2-low group, immune-receptor programmes were preferentially enriched, including B-cell-receptor signalling, immunoglobulin production and several cytokine/chemokine pathways (Fig. 5A,B), consistent with retention of B-cell identity. Conversely, the PRKD2-high samples selectively activated secretory-stress and metabolic modules: unfolded-protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum, protein-complex export, N-glycan biosynthesis, protein export and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 5C,D). Thus, loss of B-cell-receptor signaling in the PRKD2-high subgroup is accompanied by a shift toward ER-stress management and glycoprotein-processing rather than activation of alternative immune networks. Immunogen profiling then dichotomized the cohort at median PRKD2 expression. The PRKD2- high arm displayed a larger fraction of memory B cells and plasma-cell precursors, with a reciprocal drop in CD4-memory T cells, monocytes and mast cells (Fig. 5E,F).

PRKD2 expression dictates immune-pathway activity and leukocyte composition. (A–D) ssGSEA enrichment plots. In PRKD2-low marrows, B-cell receptor signalling, antigen presentation and other immune pathways rank among the top positively enriched sets; the same pathways are depleted in PRKD2-high samples. (E) CIBERSORT-derived leukocyte fractions for each sample, stacked by cell type. PRKD2-high cases (red) show a relative increase in memory B-cell compartments and a reduction in CD4 memory T cells, monocytes and mast cells compared with PRKD2-low cases (blue). (F) Box-scatter comparison of the most significantly altered immune subsets between PRKD2 groups (Wilcoxon; P < 0.05 marked by asterisks). (G) Correlation matrix (colour) and network (edges > |0.2|) linking PRKD family members to 22 immune-cell subsets. PRKD2 is uniquely and negatively correlated with mature plasma cells (blue edge), whereas PRKD1/3 show weaker, non-specific associations.

Correlation mapping across 22 leukocyte subsets showed that among PRKD kinases, PRKD2 was uniquely and negatively linked to mature plasma-cell abundance (Fig. 5G, blue edge). PRKD1/3 exhibited broader but weaker associations. These data indicate that PRKD2 skews the marrow toward a B-lineage–dominant but plasma-cell–suppressed environment, potentially favouring the expansion of malignant clones at the expense of normal immunoglobulin-secreting cells.

PRKD2 dampens antigen presentation yet confers axitinib sensitivity in myeloma

Pathway enrichment of the PRKD2-high versus -low bulk-RNA-seq groups highlighted marked suppression of APC, HLA and CCR signatures and a blunted type-II IFN response (Fig. 6A). Consistent with this, the PRKD2-high cohort showed lower basal expression of multiple HLA genes, whereas PRKD2 knock-down—but not over-expression—significantly up-regulated HLA-E, a key non-classical presenter (Fig. 6B,C), indicating that PRKD2 restricts adaptive-immune visibility.

High PRKD2 suppresses antigen-presentation pathways yet confers axitinib sensitivity. (A) ssGSEA comparing PRKD2-high vs. -low marrows: APC signalling, HLA machinery, CCR axis and type-II IFN response are all down-regulated in the high group. (B,C) HLA gene expression under PRKD2 manipulation: over-expression has little impact, whereas PRKD2 knock-down markedly elevates HLA-E. (D) RNA-seq of PRKD2-knockout myeloma cells. Loss of PRKD2 in RPMI-8226 cells lowers CD80 and FCGR1A while raising VEGFA (log2 FC ± SD, n = 3 replicates). (E) RNA-seq of PRKD2-over-expressing myeloma cells. Conversely, PRKD2 over-expression increases IL-6 and MERTK in the same cell lines (log2 FC ± SD, n = 3). (F) PD-L1 mRNA shows no difference between PRKD2 strata. (G) GDSC mining links rising PRKD2 to greater in-vitro sensitivity to the VEGFR/PDGFR inhibitor axitinib (Pearson r = 0.68). (H) Boxplot confirms higher axitinib sensitivity (lower IC50 index) in the PRKD2-high cohort. (I) Representative Annexin V/7-AAD density plots of vector control (LV3-vector, LV5-vector), PRKD2 knock-down (1965-PRKD2-KD) and PRKD2 over-expression (HOMO-PRKD2-OE) cells after 48 h exposure to DMSO or axitinib (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 µM). Quadrants: Q1, necrotic; Q2, late apoptotic; Q3, early apoptotic; Q4, viable. (J) Quantification of total apoptosis (Q2 + Q3) from three independent experiments (mean ± SD). PRKD2-OE cells show significantly higher apoptosis than the LV5 control at every dose, whereas PRKD2-KD cells are intrinsically pro-apoptotic and further sensitised by axitinib. (K) Relative cell proliferation measured by CCK-8 after the same 48 h treatments. PRKD2 loss reduces basal growth and slightly lowers viability at 10 µM, while axitinib abolishes the proliferative advantage of PRKD2-OE cells. Statistical analysis: two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; P < 0.05 versus corresponding vector control at the same concentration; *P < 0.05 versus DMSO within the same cell line. Error bars denote SD (n = 3).

Macrophage-related transcripts were also altered: PRKD2 knockout reduced the co-stimulatory ligand CD80 and the high-affinity Fc γ receptor FCGR1A, while simultaneously elevating VEGFA levels (Fig. 6D). Conversely, PRKD2-overexpression increased IL-6 and MERTK (Fig. 6E), implying that PRKD2 skews macrophages toward a tumor-supportive, angiogenic phenotype. Checkpoint analysis revealed no difference in PD-L1 mRNA between PRKD2 strata (Fig. 6F), suggesting that anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy is unlikely to offset PRKD2-mediated immune escape.

Drug-response mining of the GDSC panel demonstrated that higher PRKD2 expression predicts greater axitinib sensitivity. A Pearson analysis showed a strong positive correlation between PRKD2 mRNA level and the –log10-transformed IC50 (R = 0.68, P < 0.001; Fig. 6G), indicating that cells with elevated PRKD2 require lower absolute drug concentrations to reach 50% growth inhibition. When cell lines were stratified, the PRKD2-high cohort displayed a significantly higher sensitivity index than the PRKD2-low group (median –log10 IC50 = 2.4 vs. 1.8; P = 0.00037; Fig. 6H). Thus, PRKD2 over-expression marks a biologically defined subset of multiple-myeloma cells that are intrinsically more responsive to VEGFR/PDGFR blockade, suggesting that axitinib monotherapy—or low-dose axitinib–based combinations—may be particularly effective in PRKD2-high disease, whereas PRKD2-low tumours could require alternative or synergistic regimens.

As illustrated in Fig. 6I–K, PRKD2 status dictates both apoptotic sensitivity and proliferative fitness of H929 myeloma cells under axitinib pressure. Cells were treated for 48 h with DMSO or axitinib (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 µM); PRKD2 was either knocked down (1965-PRKD2-KD) or over-expressed (HOMO-PRKD2-OE), with LV3- and LV5-vector lines as matched lentiviral controls. Annexin V/7-AAD contour plots (Fig. 6I) and their quantification (Fig. 6J) demonstrate a dose-dependent rise in total apoptosis across all four lines, but the amplitude is clearly PRKD2-dependent. PRKD2-OE cells displayed a ~ 1.4-fold higher apoptotic fraction than LV5 at every dose (e.g., 1.25 µM: 32% ± 2% vs. 22% ± 3%; 10 µM: 64% ± 4% vs. 33% ± 3%, P < 0.05), indicating that elevated PRKD2 creates a liability to VEGFR/PDGFR blockade. Conversely, PRKD2-KD cells were intrinsically fragile, with basal apoptosis already doubled over LV3 (26% ± 2% vs. 12% ± 1%) and climbing further to ~ 62% at 10 µM. Proliferation assays (Fig. 6K) tell the reciprocal story: PRKD2 loss curtailed growth to ~ 70% of LV3 even without drug and fell slightly further at 10 µM, whereas PRKD2-OE conferred no lasting advantage once axitinib was applied—cell viability converged to 72–78% of vehicle across 1.25-10 µM, effectively nullifying the proliferative benefit of PRKD2. Taken together, these data show that PRKD2 simultaneously sustains baseline proliferation and sensitises cells to axitinib-induced apoptosis; removal of PRKD2 cripples growth but also abolishes the apoptotic surge elicited by the inhibitor. Thus, PRKD2 functions as a context-specific driver of myeloma cell fitness and represents a tractable co-target that could potentiate axitinib-based therapy.

Discussion

Multiple complementary analyses converge on the view that PRKD2 is a previously unrecognised driver of aggressive myeloma biology. At the transcriptomic level, PRKD2 is the only gene uniformly up-regulated across newly diagnosed, RRMM and poor-survival datasets, and its expression scales with mRNA-based stemness indices, high ISS stage, therapeutic resistance and inferior overall survival. Single-cell pseudotime mapping localises PRKD2 to the malignant plasma-cell trajectory, where it rises in tandem with ER-stress and secretory programmes; WGCNA further places PRKD2 at the hub of a stemness-linked co-expression module enriched for “protein processing in the ER”, proteasome activity and MAPK/PI3K-Akt signalling. Functionally, PRKD2 silencing slows myeloma-cell proliferation, restores HLA-E expression and partially normalises macrophage cytokine profiles, whereas over-expression suppresses antigen-presentation genes and skews macrophages toward an IL-6/MERTK, tumour-supportive phenotype. Immune-deconvolution indicates that high-PRKD2 marrow is characterised by expanded naïve/ memory B-cell pools yet a relative paucity of mature plasma cells, implying that PRKD2-driven clones out-compete their normal counterparts and blunt adaptive immunity. Finally, drug-sensitivity mining reveals a positive correlation between PRKD2 levels and axitinib responsiveness, nominating VEGFR/PDGFR blockade—alone or combined with proteasome inhibition—as a precision option for PRKD2-high disease. Collectively, these findings position PRKD2 at the intersection of secretory stress, stemness, immune evasion and drug vulnerability, and highlight it as a mechanistic linchpin and therapeutic target in relapsed and high-risk multiple myeloma.

Our study revealed an abnormal enrichment of HLA-related immune responses in RRMM patients. HLA, also known as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), is a group of genes located on chromosome 6 that encode proteins involved in the regulation of the immune system23. Typically, MHC can be categorized into class I, II, and III based on their specific structure and functions of their gene products. Gene products of class I present peptide fragments derived from endogenous sources to cytotoxic CD8 + T cells, while class II facilitate the presentation and delivery of exogenous peptides to T helper cells24. Conversely, class III proteins are directly involved in antigen presentation but mediate the production of various inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-125. In the adaptive immune system, macrophages serve as professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), playing a crucial role in initiating and regulating downstream immune cascades26. Of note, MHC II molecules are specific biomarkers located on the surface of macrophages, through which processed antigens within macrophages can be successfully presented and delivered to CD4 + T cells (T helper cells), activating and stimulating downstream B cells to differentiate into either plasma cells for antibody production or memory cells for defense against further reinfection27. Therefore, MHC II proteins are of particular importance, and several studies have reported that the dysfunction of MHC II is one of the primary reasons for inherited immunodeficiency, with patients suffering from MHC II deficiency having an increased susceptibility to respiratory and gastrointestinal infections28. Thus, abnormal HLA expression can lead to immune defense abnormalities in the body, making abnormal plasma cells difficult to clear in a timely manner, thereby resulting in MM progression, which is consistent with our research findings.

PD-L1, or programmed death-ligand 1, is a protein utilized by cancer cells to evade immune surveillance primarily by reducing the proliferation of antigen-specific T cells during adaptive immune responses29. Typical PD-L1 inhibitors are a class of anticancer drugs that can block the activity of PD-L1 immune checkpoint proteins located on the surface of cancer cells30,31,32. In this study, we have demonstrated that the expression of PD-L1 is not associated with differences in PRKD2 levels, indicating that PRKD2 induces the occurrence of MM or RRMM in a manner independent of PD-L1 expression. Therefore, traditional PD-L1 inhibitors may not be able to suppress the proliferation, differentiation, and metastasis of tumor cells in MM patients with abnormally elevated PRKD2 levels, and these malignant cells may continue to attack the adaptive immune system under conditions of increased PRKD2 expression. For these reasons, it is necessary to design or discover new drugs or treatment methods that alleviate MM or RRMM by acting in conjunction with PRKD2. In other words, PRKD2 should be the therapeutic target of the new drugs or treatment methods we are seeking.

Due to the limited efficacy of traditional PD-1/PD-L1-related drugs in PRKD2-aberrant MM, we analyzed drug databases and identified Axitinib as a potential effective medication. Our findings revealed that as the level of PRKD2 increases, the sensitivity to Axitinib gradually rises, although this positive correlation may not be as strong as a linear relationship. Particularly, high Axitinib sensitivity corresponds to high PRKD2 levels, emphasizing PRKD2 as a potential binding target of Axitinib. Axitinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor commonly used in cancer therapy33. Essentially, Axitinib functions by blocking specific receptors in cancer cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and spread34. While Axitinib treatment may lead to various side effects such as fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, it has been shown to significantly inhibit breast cancer growth in animal models and has received approval for renal cell carcinoma treatment35. However, there is limited research on the potential therapeutic effects of Axitinib in MM or RRMM. This significant finding suggests that Axitinib may treat MM or RRMM by targeting PRKD2.

PRKD2 is highly upregulated in MM/RRMM, enhancing cell proliferation and altering endoplasmic reticulum protein processing. This disrupts immune responses, particularly by impairing macrophage function and reducing HLA expression, potentially facilitating disease progression. Unlike other tumors, increased PRKD2 does not upregulate PD-L1, suggesting PD-L1 inhibitors may be less effective. Axitinib, however, suppresses PRKD2, possibly restoring macrophage function and improving MM/RRMM outcomes. The study’s limitations include small sample size, binary PRKD2 grouping, and reliance on preliminary data. Further animal models and clinical trials are essential to confirm Axitinib’s efficacy and safety in MM/RRMM. PRKD2’s detrimental role necessitates exploring novel therapeutic approaches.

Conclusion

This study identifies PRKD2 as a central-acting kinase that integrates secretory stress, stemness maintenance and immune evasion in multiple myeloma. PRKD2 is consistently over-expressed in newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory disease, rises along the malignant plasma-cell trajectory, and predicts high ISS stage, therapeutic resistance and poor overall survival. Mechanistically, PRKD2 suppresses antigen-presentation genes, skews macrophages toward an IL-6/MERTK, tumour-supportive phenotype and drives myeloma-cell proliferation, whereas genetic silencing reverses these effects and restores HLA-E expression. Drug-sensitivity mining further links PRKD2 abundance to heightened responsiveness to the VEGFR/PDGFR inhibitor axitinib, suggesting an immediately testable precision-therapy option. Taken together, our findings establish PRKD2 as a mechanistic linchpin of aggressive myeloma biology and highlight pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of PRKD2 as a promising strategy to curb disease progression and improve outcomes in high-risk and relapsed multiple myeloma.

Data availability

The RNA-seq datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE268395 and are publicly available at: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE268395]. Additional materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

26 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28728-6

References

Kazandjian, D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin. Oncol. 43 (6), 676–681 (2016).

Criteria for the classification of. Monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the international myeloma working group. Br. J. Haematol. 121 (5), 749–757 (2003).

Raab, M. S., Podar, K., Breitkreutz, I., Richardson, P. G. & Anderson, K. C. Multiple myeloma. Lancet 374 (9686), 324–339 (2009).

Kyle, R. A. & Rajkumar, S. V. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 111 (6), 2962–2972 (2008).

Fisher, S. A. et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in Haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1 (1), Cd009768 (2019).

Estcourt, L. J. et al. Comparison of different platelet count thresholds to guide administration of prophylactic platelet transfusion for preventing bleeding in people with haematological disorders after myelosuppressive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 (11), Cd010983 (2015).

Child, J. A. et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (19), 1875–1883 (2003).

Greipp, P. R. et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (15), 3412–3420 (2005).

Bhatt, P., Kloock, C. & Comenzo, R. Relapsed/Refractory multiple myeloma: A review of available therapies and clinical scenarios encountered in myeloma relapse. Curr. Oncol. 30 (2), 2322–2347 (2023).

Hideshima, T. & Anderson, K. C. Signaling pathway mediating myeloma cell growth and survival. Cancers (Basel). ;13(2). (2021).

Rosenblatt, J. & Avigan, D. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in multiple myeloma: a dream or a reality? Blood. 129 (3), 275–279 (2017).

Sturany, S. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human protein kinase D2. A novel member of the protein kinase D family of Serine threonine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (5), 3310–3318 (2001).

Liu, Y. et al. Oncogenic functions of protein kinase D2 and D3 in regulating multiple cancer-related pathways in breast cancer. Cancer Med. 8 (2), 729–741 (2019).

Roy, A. et al. Protein kinase D2 and D3 promote prostate cancer cell bone metastasis by positively regulating Runx2 in a MEK/ERK1/2-Dependent manner. Am. J. Pathol. 193 (5), 624–637 (2023).

Wille, C. et al. Protein kinase D2 induces invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by regulating matrix metalloproteinases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 25 (3), 324–336 (2014).

Azoitei, N., Fröhling, S., Scholl, C. & Seufferlein, T. PRKD2: A two-pronged kinase crucial for the tumor-supporting activity of HSP90. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2 (2), e981444 (2015).

Misawa, T. et al. Mutual inhibition between Prkd2 and Bcl6 controls T follicular helper cell differentiation. Sci. Immunol. ;5(43). (2020).

Michaud, D., Mirlekar, B., Steward, C., Bishop, G. & Pylayeva-Gupta, Y. B cell receptor signaling and protein kinase D2 support regulatory B cell function in pancreatic cancer. Front. Immunol. 12, 745873 (2021).

Malta, T. M. et al. Machine learning identifies stemness features associated with oncogenic dedifferentiation. Cell 173 (2), 338–354 (2018). e15.

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28 (11), 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D7 (2025).

Choo, S. Y. The HLA system: genetics, immunology, clinical testing, and clinical implications. Yonsei Med. J. 48 (1), 11–23 (2007).

Marchesi, M. et al. HLA-dependent tumour development: a role for tumour associate macrophages? J. Transl. Med. 11, 247 (2013).

Gruen, J. R. & Weissman, S. M. Human MHC class III and IV genes and disease associations. Front. Biosci. 6, D960–D972 (2001).

Hirayama, D., Iida, T. & Nakase, H. The phagocytic function of Macrophage-Enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(1). (2017).

Frei, R. et al. MHC class II molecules enhance Toll-like receptor mediated innate immune responses. PLoS One. 5 (1), e8808 (2010).

Farrokhi, S. et al. MHC class II deficiency: report of a novel mutation and special review. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr). 46 (3), 263–275 (2018).

Han, Y., Liu, D. & Li, L. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 10 (3), 727–742 (2020).

Gong, J., Chehrazi-Raffle, A., Reddi, S. & Salgia, R. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J. Immunother. Cancer. 6 (1), 8 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in tumor immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 731798 (2021).

Shiravand, Y. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 29 (5), 3044–3060 (2022).

Bellesoeur, A., Carton, E., Alexandre, J., Goldwasser, F. & Huillard, O. Axitinib in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: design, development, and place in therapy. Drug Des. Dev.Ther. 11, 2801–2811 (2017).

Carmichael, C., Lau, C., Josephson, D. Y. & Pal, S. K. Comprehensive overview of axitinib development in solid malignancies: focus on metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 10 (5), 307–314 (2012).

Wilmes, L. J. et al. AG-013736, a novel inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases, inhibits breast cancer growth and decreases vascular permeability as detected by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 25 (3), 319–327 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Suzhou Medical College of Soochow University and Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University for their support of this research project.

Funding

This research was funded by the Xuzhou Science and Technology Bureau Project (Grant number KC23231). Additional support was provided by the Xuzhou Health Commission (Grant number XWKYHT20230015) and Open project of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of bone marrow stem cells (NO. XZSYSKF2020037).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. S.C., C.G. and Y.S. contributed to the data analysis. J.X., C.C., F.M., H.Z., Y.K., R.J., and K.L. provided data support. The supervision and revision of the manuscript were managed by J.Q., H.L. and Z.L., who actively participated in all aspects of the study process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human ethics and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients (or their legal guardians), ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the research objectives.

Consent for publication

All authors provided their consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the order of the Figures. Figure 1 was published as Figure 3, Figure 2 was published as Figure 1, Figure 3 was published as Figure 4, Figure 4 was published as Figure 6, Figure 5 was published as Figure 2, and Figure 6 was published as Figure 5. As a result, the Figure legends were incorrect. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Cao, S., Geng, C. et al. Single-cell and bulk transcriptomics uncovers PRKD2-driven tumor stemness and progression in multiple myeloma. Sci Rep 15, 36723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20615-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20615-4