Abstract

To quantitatively measure the volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) in different parts of the brain in patients with different types of cognitive function and analyze the relationship between WMH volume and cognitive function to obtain a threshold WMH volume for the early detection and clinical assessment of cognitive dysfunction. The clinical data and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data of patients with WMHs indicated by cranial MR in the Department of General Medicine of Shandong Provincial Third Hospital were collected. The FLAIR sequence images of the patients were subsequently analyzed with computer automated detection technology. Through deep learning-based 3D reconstruction, the specific volumes of the patients’ WMHs were obtained. Patients were divided into three groups according to the Fazekas scale score: Fazekas score 1, Fazekas score 2, and Fazekas score 3. The WMH volumes within each group were subsequently compared, and the correlations between the WMH volumes of the patients in each group and their Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores, Trail Making Test A (TMT-A) scores, Trail Making Test B (TMT-B) scores, age, duration of hypertension, duration of diabetes, basic information, etc., were analyzed. The patients were subsequently divided into a normal group (MoCA > 25) and a mild cognitive impairment group (18 < MoCA ≤ 25) on the basis of their MoCA scores. The WMH volumes in each group were then calculated separately. The cutoff values of the WMH volume for differentiating between the normal group and mild cognitive impairment group were obtained through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The MoCA scores significantly differed among the three Fazekas score groups (r = − 0.5716, P < 0.0001). There were also statistically significant differences in the total volume of WMHs among the three groups (r = 0.7527, P < 0.0001). WMH volume was positively correlated with the TMT-A and TMT-B scores (r = 0.2345, P< 0.05; r = 0.2404, P < 0.05) but negatively correlated with the MoCA score (r = − 0.4789, P < 0.0001). Moreover, WMH volume was positively associated with the duration of hypertension (F = 4.743, P < 0.05) but not with the duration of diabetes (F = 1.431, P = 0.2456). The cutoff value of WMH volume between the normal group and mild cognitive impairment group was 15.474900; at this value, the sensitivity of the WMH volume in discriminating the two groups was 0.808, and the specificity was 0.556. Automated detection technology can successfully be used to obtain the volume of WMHs in different parts of patients’ brains. Since WMH volume is correlated with cognitive function scores, we can use MRI to identify and assess individuals who show potential early signs of cognitive dysfunction and administer early interventions. These findings provide potential preventive and therapeutic targets for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of cognitive dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia, accounting for approximately 15% of cases. However, unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which ranks first, there is no standard treatment for vascular dementia1. Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is a major cause of vascular mild cognitive impairment (VMCI)2,3. This latter condition greatly harms people’s lives and places an increasingly heavy burden on their families and society4. Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) refers to cognitive dysfunction primarily caused by cerebrovascular diseases and their risk factors, encompassing the entire range from mild cognitive impairment to dementia2. The early stage of VCI is VMCI, which can be prevented, delaying the progression of cognitive impairment5,6. However, without intervention at this stage, VMCI will gradually develop into vascular dementia, at which point the disease is considered irreversible7. As a neuroimaging marker of cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), the imaging manifestations of leukoaraiosis or leukodystrophy, have an extremely high incidence in the population. These hyperintensities are jointly important risk factors for VMCI and are among its strongest radiological predictors8,9,10. Given these clinical characteristics, this study suggests that early identification of and cognitive intervention for potential VMCI patients via the detection of WMHs would be highly important for research on vascular dementia. Clinical studies have shown that even in older adults with normal cognitive function, those with a large WMH volume have a significantly increased risk of dementia with age11,12,13. The progression of VMCI caused by WMHs is slow, and early diagnosis is difficult. By the time patients show obvious dementia symptoms, they have typically missed the opportunity for early intervention and treatment. Therefore, the development of technology for the quantitative identification of WMHs and its application in the early screening of VMCI patients could result in the development of early intervention strategies for patients with cognitive impairment and delay the occurrence of vascular dementia. WMHs thus present potential therapeutic targets for interventional trials in individuals with cognitive impairment.

Owing to the variability of complex brain anatomy, differences among imaging protocols, and the imperfection of image acquisition, brain imaging analysis has been a major challenge in the field of computer-aided technology. Compared with the manual feature extraction methods employed alongside traditional machine learning algorithms14,15,16,17, novel image-based self-learning methods have been shown to extract complex feature hierarchies from images. However, more general techniques, such as deep learning, are needed to address these changes. Brain MRI segmentation methods based on deep learning have attracted much attention because of their self-learning ability and ability to generalize large amounts of data. With the increasing maturity of deep learning architecture, the performance of such methods has gradually exceeded that of the most advanced, classical machine learning algorithms currently in use.

This study provides an intelligent method for accurately predicting the volume of WMHs by applying a deep learning-based high-signal 3D reconstruction technique18 to obtain specific WMH volume data. The diagnostic results for the WMHs according to deep learning were compared with the diagnostic evaluations of the doctors. At the same time, a professional team of clinicians administered a variety of behavioral cognitive scales, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Trail Making Tests A (TMT-A) and B (TMT-B), while basic patient information, including sex, age, disease duration, blood lipid levels, and blood sugar levels, was obtained. We assessed WMH volumes and their associations with cognitive function. Through this study, we provide an intelligent method for accurately predicting the volume of WMHs and apply it to the automatic identification and screening of patients with mild cognitive impairment in clinical practice to allow the development of early intervention strategies and potentially delay the occurrence of vascular dementia.

Materials and methods

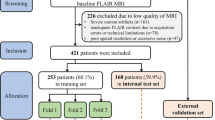

Sample population

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Hospital of Shandong Province (Approval Number: KTLL-2020042), and written consent was obtained from all the subjects. We confirm that all studies were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations and that written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians prior to testing. We continuously recruited 76 inpatients and outpatients aged between 50 and 80 years who presented with WMHs on T2-weighted imaging as indicated by cranial MRI in our hospital from January to December 2021. According to the “Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement”, the inclusion criteria we have set are as follows: patients aged 50 to 80 years with hypertension; head MRI shows no history of stroke, head trauma, encephalitis, hydrocephalus, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia or other central nervous system diseases; no systemic diseases causing cognitive impairment; no history of congenital mental retardation or anxiety and depression; no drugs affecting cognitive function; and able to cooperate with the cognitive function assessment. The exclusion criteria were nonvasogenic WMHs(Poisoning, metabolic diseases, immune-mediated disorders, protein malnutrition and mitochondrial diseases, infections, tumors); clear indications of cortical or hippocampal atrophy on cranial MRI; a Hachinski Ischemic Scale score suggesting that the patient’s cognitive impairment might be caused by degenerative diseases; alcohol or drug dependence; disorders of consciousness; aphasia; other diseases that would affect cognitive evaluations; or the inability to complete the MRI examination.

MRI data acquisition and processing

MRI data were obtained at baseline with a 3.0-Tesla machine (Philips, Ingenia 3.0T, Netherlands) employing the following sequences: T1-weighted imaging (T1WI): repetition time (TR) 1900 ms, echo time (TE) 20 ms, slice spacing 1 mm, matrix: 308 × 158, field of view (FOV) 25.5 cm × 23 cm, 230 mm × 185 mm, scanning time 1 min and 39 s; T2-weighted imaging (T2WI): TR 2386 ms, TE 92 ms, slice thickness 6 mm, slice spacing 1 mm, matrix 308 × 308, FOV 25.5 cm × 23 cm, 230 mm × 230 mm; and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging: TR 7000 ms, TE 140 ms, slice thickness 6 mm, slice spacing 1 mm, matrix 308 × 168, FOV 25.5 cm × 23 cm, 230 mm × 184 mm, and scanning time 1 min and 45 s. The MRI data of all the subjects were collected by a professional technician in the imaging department. In this work, we used a new WMH quantitative analysis and 3D reconstruction method to reconstruct high signals in WMHs in 3D. We used ResUnet augmented with an attention mechanism to achieve highly accurate, high-signal segmentation of the WMHs. The technical details of these procedures have been described previously18.

Collection of patient basic data

We collected sex, age, years of education, duration of hypertension, duration of type 2 diabetes, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The levels of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine (Scr), and serum albumin were all precisely tested by the laboratory of Shandong Provincial Third Hospital. And left ventricular wall thickness (LVWT) of all participants was precisely measured by qualified cardiac color Doppler ultrasound physicians from Shandong Provincial Third Hospital.

WMH reconstruction

The ResUnet was utilized to achieve high-signal segmentation of white matter, and an attention mechanism was added to ResUnet to achieve more precise segmentation. After accurately segmenting the white matter high-signal areas, the segmented images of each group were reconstructed in three-dimensional form. “The marching cubes algorithm” is a classic algorithm in surface rendering. As shown in Fig. S2, move the cubes, where lk and lk + 1 represent two different isosurfaces; (i, j, k) represents the vertex of the voxel. One vertex of a voxel has two possible states, so a voxel (with 8 vertices) has a total of 28 or 256 states, where the gray value of a certain point within the voxel (as shown in Fig. S2) can be calculated using the trilinear interpolation formula (Fig. S3). a0–a7 represent the gray values of the eight vertices of the voxel; x, y, z represent the coordinate points within the voxel; f(x, y, z) represents the gray value of the (x, y, z) point within the voxel. These 256 combinations can be simplified to 128 combinations by reversing symmetry (the values of the boundary vertex 0 and 1 of the voxel are exchanged); through rotational symmetry (the positions of the boundary vertex 0 and 1 of the voxel remain the same after rotation), these 256 combinations can be simplified to 15 cases. Each state of the voxel element contains multiple tetrahedrons, and the vertices of the triangular faces within the voxel need to be calculated through linear interpolation based on the values of the isosurface and the values of the two adjacent vertices on both sides. To solve the blurring problem at the connection points of the moving solid method, this study adopted the moving tetrahedron method for three-dimensional reconstruction. Compared with the moving solid method, the moving tetrahedron algorithm divides the cube units in the marching cubes algorithm into tetrahedrons. There are many ways of segmentation, and it is usually divided into 5 tetrahedrons and then builds the isosurface within the tetrahedron. There are a total of 24 and 16 combination methods. Through reversal and rotational symmetry, only one vertex of the boundary voxel is greater than the isosurface, thereby generating triangular faces. If both vertices are greater than the isosurface, a quadrilateral face will be generated. This study uses the moving tetrahedron method to perform three-dimensional reconstruction of the brain white matter and can achieve better modeling accuracy.

Cognitive function tests

We organized professional-trained clinical physicians to conduct cognitive function evaluations on the patients. All participants were assessed via neuropsychological tests to determine their overall level of cognition and their cognition in different cognitive domains, including language ability, memory ability, executive ability and processing speed. The general cognitive level was assessed by the MoCA(Beijing version7.1). The maximum score of the MoCA scale is 30 points. A score above 26 is considered normal. A score of 18 or above but less than 26 indicates the presence of MCI. And processing speed was assessed by the TMT-A and TMT-B. Accurately record the time taken by each subject to complete TAT-A and TAT-B.

Statistical analysis

Firstly, based on the Fazekas score, the patients were classified into Fazekas 1, Fazekas 2 and Fazekas 3 groups. The Fazekas scale is mainly used in clinical practice to reflect the extent of WMH lesions. Periventricular and deep WMH lesions are usually separately scored and classified into four grades according to the Fazekas scale (Fig. 1). Fazekas scores of 0 indicate no lesion, Fazekas scores of 1 indicate spot-like lesions, Fazekas scores of 2 indicate plaque-like lesions (partial spot aggregation), and Fazekas scores of 3 indicate patch-like lesions (lesions integrated into large patches). For age, education years, years of hypertension, years of type 2 diabetes, BMI, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, TG, LDL, BUN, Scr, serum albumin and LVWT in each group, one-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons among groups. To test for sex differences, we employed the chi-square test. Secondly, considering that the statistical data were non-normal, spearman correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlations between the cognitive domain-level MoCA scores, processing speed on the TMT-A and TMT-B and WMH volume. Stratified analysis was also performed for the correlations between WMH volume and cognitive function. Finally, Patients were divided into a normal group (MoCA > 25) and a mild cognitive impairment group (18 < MoCA ≤ 25) on the basis of their MoCA scores. The volumes of WMHs in each group were subsequently calculated separately. The cutoff values of WMH volume for the normal group and the mild cognitive impairment group were obtained through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.The r value represents the default Spearman correlation coefficient output by the statistical software. GraphPad Prism 8 software and IBM SPSS Statistics 27 were used for statistical analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for all analyses.

Four-point Fazekas scale for white matter hyperintensities. The T2 FLAIR images show examples of the four Fazekas scale scores for white matter hyperintensities: no lesions (Faze score of 0), punctate lesions (Fazekas score of 1), early confluent lesions (Fazekas score of 2), and diffuse confluent lesions (Fazekas score of 3).

Results

Statistical analysis between the Fazekas scale score and basic patient data

We collected data on patient sex, age, duration of hypertension and type 2 diabetes, blood lipid levels, liver and kidney function parameters, glycosylated hemoglobin, BMI, and LVWT (Table 1). Statistical analysis was conducted for these basic patient data among different Fazekas scale score groups. We found that there were statistically significant differences in age (F = 4.743, P < 0.05) and duration of hypertension (F = 4.467, P < 0.05) among the Fazekas scale score groups, whereas the differences in years of education (F = 2.730, P = 0.0719), duration of type 2 diabetes (F = 1.431, P = 0.2456), BMI, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, TG, LDL, BUN, Scr, serum albumin, and LVWT among the groups were not statistically significant.

Correlations between the Fazekas scale score and MoCA score

We collected T2 FLAIR sequences from the cranial MR images of all the participants and used them to calculate the Fazekas scale score. Spearman correlation analysis was subsequently conducted between the Fazekas scale score and the MoCA score (Fig. 2A), revealing a statistically significant negative correlation between the two parameters (r = − 0.5716, P < 0.0001).

Correlations among Fazekas scale scores, MoCA scores and WMH volumes. (A) Seventy-six patients with varying extents of WMHs were enrolled in our study, including 36 patients with Fazekas scores of 1, 19 patients with Fazekas scores of 2, and 20 patients with Fazekas scores of 3. (B) The correlations between WMH volume and Fazekas scale score were analyzed via Spearman correlation analysis.

Correlation between WMH volume and Fazekas scale score

Spearman correlation analysis was conducted between the WMH volumes and the Fazekas scale scores of the patients (Fig. 2B), revealing statistically significant differences in the total volume of WMHs among the three groups (r = 0.7527, P < 0.0001).

Correlations between WMH volume and cognitive function score

We calculated the WMH volumes of all participants via our automated computer detection system as described above. Spearman correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between the volume of WMHs and the time spent on TMT-A and TMT-B (Fig. 3A, B; r = 0.2345, P < 0.05). Spearman correlation analysis also revealed a significant negative correlation between WMH volume and the MoCA scores of the participants (r = 0.4789, P < 0.0001).

Correlation analysis among WMH volume and the TMT-A, TMT-B and MoCa scores. WMH results were obtained via the automatic calculation methods of the software. This set of data reflects the Spearman correlations between WMH volumes and the time required to complete the TMT-A (A), the time required to complete the TMT-B (B), and the MoCA scores (C).

Cutoff values for WMH volume in individuals with normal cognitive function and those with mild cognitive impairment

We divided the subjects into a normal group and a VMCI group according to their MoCA scores and obtained the WMH volumes of the two groups. ROC curve analysis, including calculation of the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index, was used to determine the cutoff value that best distinguished the normal group from the VMCI group (Fig. 4). Analysis of the data in SPSS yielded a value of 0.7286, as shown in Fig. 3D. The optimal cutoff value was 15.475, at which point the sensitivity was 0.808 and the specificity was 0.556.

Discussion

With the aging of the population, the global incidence of dementia has been increasing annually, and an increasing body of evidence shows that vascular factors may be related to the progression of dementia. WMHs are considered white matter changes caused by small blood vessel ischemia. The quantification of WMHs is beneficial for the analysis of risk factors for ischemia and cognitive function in dementia patients. Therefore, the development of tools for measuring WMHs suitable for clinical use would be highly important in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of dementia.

This study employed an intelligent 3D reconstruction and accurate volume measurement method for WMH signals under a smart healthcare framework. The automatic calculation method adopted in this study only requires T2 FLAIR sequences from cranial MR images obtained in routine clinical practice; the subsequent WMH data can be easily obtained in clinical practice by storing and uploading DICOM-formatted images into the software. This study proposes an attention-based model called Attention-Unet. The model incorporates an attention mechanism to achieve more accurate WMHs segmentation and improve the precision of 3D reconstruction. Experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves Dice coefficient and MPA scores of 92.52% and 92.43%, respectively, on the WMH dataset, outperforming current mainstream segmentation models (Table S2, Fig. S4, Fig. S5). Consequently, it enables precise 3D reconstruction and volumetric measurement of WMH18. Moreover, this study was conducted in a clinical setting to measure and analyze the WMH volume of patients with cognitive impairment quantitatively and score the relevant cognitive function scales and executive function scales of patients. The results revealed that the volume of WMHs obtained via the automated computer system was consistent with the Fazekas scale score manually obtained by professional physicians, and the statistical analysis revealed a correlation between the two variables. Moreover, correlations were analyzed between the relevant cognitive function and executive ability data of the participants and both the Fazekas scale score and WMH volume. These results verify the feasibility and sensitivity of the computer-based automated measurement method for WMHs we previously described. By analyzing the WMH data of the normal population and individuals with mild cognitive impairment, we obtained the optimal WMH cutoff value for discriminating the two groups. In this study, although the area under the ROC curve (AUC = 0.72) for WMH volume does not reach the threshold for independent diagnosis, its auxiliary value in diagnosis cannot be denied. In the future, it may be possible to obtain more accurate critical values through the analysis of larger samples. For individuals who have not yet shown obvious cognitive symptoms but have an increased WMH volume, especially those with vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes, WMH volume can be used as a “potential risk marker”. This prompts clinicians to strengthen cognitive function monitoring (e.g., rechecking the MoCA every 6–12 months) to achieve early risk identification. In community screening for cognitive impairment, WMH volume can first be evaluated via cranial MRI. Those with a high volume should be focused on for comprehensive cognitive assessment, which reduces over-testing in low-risk populations and improves the targeting of screening. Through artificial intelligence analysis of MR data and early identification of individuals who may develop cognitive dysfunction in the future, it would be possible to reduce the incidence of cognitive dysfunction through the development and implementation of early intervention strategies. The findings of this study provide potential preventive and therapeutic targets for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of cognitive dysfunction.

There have been numerous reports on the correlation between WMHs and the cognitive function of patients with cSVD. It is generally believed that WMHs are related to ischemic changes; patients are often complicated with hypertension, and appropriate targeted blood pressure control can alleviate the progression of WMHs. Some studies19,20,21 have also indicated that the volume of WMHs in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease is related to hypertension, suggesting that WMHs are also associated with hypertension. We analyzed the duration of hypertension and the volume of WMHs on the MR images of the patients and identified a positive correlation between the two variables (P < 0.05). Notably, however, the correlation between the duration of hypertension and the volume of WMHs in patients with well-controlled blood pressure may not be significant. We conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis using WMH volume, age and duration of hypertension as independent variables, and cognitive function as the dependent variable. Supplementary Material Table S1 shows that there is a significant correlation between cognitive ability and WMHs, while there is no significant difference in the duration of hypertension. In future studies, we plan to track the blood pressure levels of patients and study the relationships between the degree of control of blood pressure, future WMHs, and the cognitive function of patients. In addition, an analysis of the duration of diabetes in patients revealed no correlation with the total volume of WMHs.

In recent years, automatic detection technology based on computer software has undergone rapid development, and the application of computer-assisted quantitative measurement methods for the volume of WMHs in clinical practice has received widespread attention. Some studies22,23 have shown that the total volumes of WMHs and the volumes of frontal and parietal lobe WMHs are significantly associated with the diagnosis of severe cognitive dysfunction, whereas this was not the case for temporal lobe WMH volume. Similarly, the volume of periventricular WMHs but not deep WMHs is significantly associated with the clinical diagnosis24,25. Because small, discrete lesions have different intensity distributions than larger lesions do, deep WMHs may appear fainter than periventricular WMHs. Therefore, various segmentation methods may undersegment deep WMHs, resulting in a stronger relationship between the volume of periventricular WMHs and clinical variables than between the volume of deep WMHs and these same variables. In our future research, we plan to segment lesions in different locations in detail and employ different analytical algorithms in the hope of obtaining more accurate results. At the same time, additional clinical or imaging markers can be introduced, such as cerebral microbleeds, diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space, or other neuroimaging features. Some analyses are computationally complex and have high requirements for imaging data; however, it may be necessary to conduct large-sample trials in the future to further confirm the findings.

This was a preliminary study on WMH volume in patients with different levels of cognitive dysfunction focused on the preliminary clinical application of quantitative WMH lesion detection technology. In this study, the correlation coefficient between the volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) and cognitive function scores was r = 0.2345, with a corresponding statistical test result of P = 0.023 (P < 0.05), which is statistically significant. The association between WMH and cognitive function is modulated by multiple factors: cognitive function is a complex multi-dimensional indicator influenced by a combination of various factors. WMH is only one of them, so the correlation obtained from a single indicator may be weak. This suggests that the impact of WMH on cognitive function may be achieved through indirect pathways rather than through a direct strong correlation. Despite this weak correlation, the result still has certain clinical value. In clinical practice, an increase in WMH volume may serve as a “potential early warning signal” for cognitive decline. The weak correlation between individual WMH volume and cognitive function does not negate its importance in multimodal assessment. Future studies can combine the spatial distribution of WMH (such as in periventricular and deep white matter regions), other imaging markers, and clinical indicators to construct a comprehensive prediction model, thereby improving the efficiency of cognitive function assessment. In future studies, we plan to incorporate more risk factors and construct a multimodal combined prediction model. One limitation of this study is its single-center nature. It will be necessary to carry out multicenter studies in the future, expand the sample size, and modify the models and algorithms by combining more clinical feedback to further improve study performance and accuracy. Meanwhile, we can dynamically obtain patients’ MoCA scores and executive ability scores across multiple periods and determine the relationship between the volume of WMHs and cognitive function through linear regression. The volume of WMH may change dynamically over time, and it may be more meaningful to capture the changes in WMH volume over time and its association with the progression of cognitive function. We plan to conduct longitudinal follow-up in subsequent studies.

In current clinical practice, physicians often need to administer multiple neuropsychological scales to assess cognitive function in patients with suspected cognitive impairment, which typically requires significant time and effort. In contrast, this study enables the quantification of WMH volume within seconds through automated data processing. If we can directly classify patients into high-risk groups for VMCI using predefined cutoff values during routine brain MR, we could achieve earlier screening and clinical intervention. This will allow clinicians to identify patients who may develop cognitive dysfunction in the future before the development of relevant symptoms, improve the efficiency of automatic identification and screening of patients with mild cognitive impairment, and allow the development and implementation of intervention and treatment strategies for these patients as early as possible to delay the occurrence of vascular dementia. The core clinical significance of the findings in this study lies in transforming WMH volume from an “imaging observation indicator” into a “quantitative marker that can guide clinical decision-making”, thereby providing a basis for risk stratification, accurate diagnosis, and targeted intervention of cognitive impairment.

Research indicates that certain cognitive training interventions, such as multidomain, adaptive computerized cognitive training, can enhance global cognitive function in patients with VMCI26 and improve working memory and attention in individuals with both WMHs and VMCI27. Meta-analyses28,29 further demonstrated that dual-task cognitive‒motor training benefits both cognitive and motor functions in cognitively impaired patients, whereas computer-assisted cognitive training shows specific efficacy in enhancing memory.

The early identification of VMCI has significant positive implications at the individual, familial, and societal levels. This study established a VMCI early screening model by integrating neuropsychological scales with artificial intelligence-assisted imaging analysis. This early detection capability creates a critical intervention window, enabling patients to access more effective treatments while compensatory mechanisms remain intact. At the individual level, early identification allows timely engagement in nonpharmacological interventions such as cognitive training and lifestyle modifications. More importantly, it prevents the psychological distress associated with abrupt dementia diagnoses, granting patients sufficient time for medical decision-making and financial planning. From a family perspective, early detection substantially reduces caregiver burden. Through participation in intervention training, family members can adopt more scientific approaches to manage cognitive decline. With respect to socioeconomic benefits, this approach may reduce healthcare expenditures for national insurance systems and lower associated societal costs. Future research will further explore precision intervention strategies based on WMHs to maximize the societal benefits of early identification.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data supporting the study are available in the database https://github.com/wls860707495/-White-Matter Hyperintensities and https://github.com/fxxq725/WMH.

References

O’Brien, J. T. & Thomas, A. Vascular dementia. Lancet 386, 1698–1706. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00463-8 (2015).

Rundek, T., Tolea, M., Ariko, T., Fagerli, E. A. & Camargo, C. J. Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. NeuroTher. 19, 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-021-01170-y (2022).

Mok, V. C. T., Cai, Y. & Markus, H. S. Vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: Mechanisms, treatment, and future directions. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 19, 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930241279888 (2024).

Lam, B. Y. K. et al. The global burden of cerebral small vessel disease in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 18, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930221137019 (2023).

Filley, C. M. Cognitive dysfunction in white matter disorders: New perspectives in treatment and recovery. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 33, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.21030080 (2021).

Markus, H. S. & de Leeuw, F. E. Cerebral small vessel disease: Recent advances and future directions. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 18, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930221144911 (2023).

Markus, H. S. & Joutel, A. The pathogenesis of cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment. Physiol. Rev. 105, 1075–1171. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00028.2024 (2025).

Biesbroek, J. M., Weaver, N. A. & Biessels, G. J. Lesion location and cognitive impact of cerebral small vessel disease. Clin. Sci. 131, 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20160452 (2017).

Roseborough, A. D. et al. White matter hyperintensities and longitudinal cognitive decline in cognitively normal populations and across diagnostic categories: A meta-analysis, systematic review, and recommendations for future study harmonization. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12642 (2023).

Hainsworth, A. H., Markus, H. S. & Schneider, J. A. Cerebral small vessel disease, hypertension, and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. Hypertension 81, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.19943 (2024).

Debette, S. & Markus, H. S. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 341, c3666. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3666 (2010).

Prins, N. D. & Scheltens, P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: An update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.10 (2015).

Hu, H. Y. et al. White matter hyperintensities and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 120, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.007 (2021).

Valdés Hernández, M. D. C. et al. Metric to quantify white matter damage on brain magnetic resonance images. Neuroradiology 59, 951–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-017-1892-1 (2017).

Rachmadi, M. F., Valdés-Hernández, M. D. C., Agan, M. L. F., Di Perri, C. & Komura, T. Segmentation of white matter hyperintensities using convolutional neural networks with global spatial information in routine clinical brain MRI with none or mild vascular pathology. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. Off. J. Comput. Med. Imaging Soc. 66, 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2018.02.002 (2018).

Dadar, M. et al. Validation of a regression technique for segmentation of white matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36, 1758–1768. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2017.2693978 (2017).

Jiang, M. et al. Impact of white matter hyperintensity and age on gait parameters in patients with cerebral small vessel disease. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 24, 672–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2022.12.001 (2023).

Wang, X., Wang, L., Yang, J. & Feng, X. Accurate 3D reconstruction of white matter hyperintensities based on attention-Unet. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 3812509. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3812509 (2022).

Misquitta, K., Dadar, M., Louis Collins, D. & Tartaglia, M. C. White matter hyperintensities and neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 28, 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102367 (2020).

Inoue, Y., Shue, F., Bu, G. & Kanekiyo, T. Pathophysiology and probable etiology of cerebral small vessel disease in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 18, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-023-00640-5 (2023).

Ungvari, Z. et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: From pathophysiology to public health. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 17, 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00430-6 (2021).

Tubi, M. A. et al. White matter hyperintensities and their relationship to cognition: Effects of segmentation algorithm. Neuroimage 206, 116327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116327 (2020).

Femir-Gurtuna, B. et al. White-matter changes in early and late stages of mild cognitive impairment. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 78, 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.078 (2020).

Bolandzadeh, N., Davis, J. C., Tam, R., Handy, T. C. & Liu-Ambrose, T. The association between cognitive function and white matter lesion location in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 12, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-126 (2012).

Griffanti, L. et al. BIANCA (brain intensity abnormality classification algorithm): A new tool for automated segmentation of white matter hyperintensities. Neuroimage 141, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.018 (2016).

Tang, Y. et al. The effects of 7-week cognitive training in patients with vascular cognitive impairment, no dementia (the Cog-VACCINE study): A randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer’s Dementia J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 15, 605–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.009 (2019).

Pantoni, L. et al. Effect of attention training in mild cognitive impairment patients with subcortical vascular changes: The RehAtt study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 60, 615–624. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-170428 (2017).

Yu, D. et al. The effect of dual-task training on cognitive ability, physical function, and dual-task performance in people with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 38, 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155231216621 (2024).

Chan, A. T. C., Ip, R. T. F., Tran, J. Y. S., Chan, J. Y. C. & Tsoi, K. K. F. Computerized cognitive training for memory functions in mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00987-5 (2024).

Funding

The present study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021MH227), the Jinan Science and Technology Bureau plan (202019181), and the Taishan Scholars Youth Expert Program of Shandong Province (No. tsqn202211355).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QH and WWZ wrote the main manuscript and performed the experiments. YYX, JJY and QH designed the study. HZ, XXL, SJZ, YYX and HYX completed the questionnaire, and QH and WWZ performed the data analysis. JJY and WQC contributed to the manuscript revisions and revised it critically for important intellectual content that contributed to manuscript revisions. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, Q., Xing, Y., Zhu, W. et al. Clinical application of 3D reconstruction and accurate volume measurement of white matter in patients with cognitive dysfunction. Sci Rep 15, 36778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20640-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20640-3