Abstract

This study evaluates the status of soil contamination by potentially toxic elements (PTEs)—Cr, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Mo, Cd, Sn, Ba, Pb in agricultural and urban areas in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in light of applicable regulations. The method validation was performed, and the uncertainty of the analytical process, including the sampling stage, was estimated. Soil samples collected by the doubling method were acid-mineralized and then analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Validation was performed with reference materials, and process uncertainty was determined by analysis of variance in the ROBAN programme. PCA analysis was also used to determine correlations between PTEs. The results for Zn, Sn, and Cu in agricultural soils, as well as Cu in urban soils, were below the limit of quantification. For Mo, Cd, and Pb in agricultural soil, and Zn and As in urban soil, the estimation was rejected due to inconclusive results. In agricultural and urban soil samples, the average Ba content was respectively 209.27% and 114.72% of the limit value standard, indicating high Ba levels. In urban soil, the Cd concentration reached 292% of the limit value. The method validation was successful, confirming the accuracy of the analysis. Exceeding the maximum limit value for Ba and Cd in soil samples can have a negative impact on the environment and pose a threat to soil and human health. More research is required to monitor the environmental risk and identify sources of hazardous metal emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During periods of rapid economic and agricultural development, it is extremely important to control the state of pollution of the environment, especially of the soils that form the basis of life on Earth. Human activities are contributing to increased soil pollution, and the differences between the contamination in urban and agricultural areas are noticeable. This pattern was confirmed in Kraków, where soils from recreational forest and glade areas showed significant variation in trace metal levels depending on proximity to anthropogenic sources such as roads or buildings1. The motivation for conducting research on soil pollution, including chemical substances in the agricultural industry, is the need for continuous monitoring of environmental conditions, which is essential for safeguarding the health and life of living organisms2,3. An example of harmful substances that have a negative impact on the environment includes metals, metalloids and elements that are essential in trace amounts, but exhibit potential ecotoxicity at elevated concentrations4.These elements, classified as potentially toxic elements (PTEs), can pose a threat to human health through various routes of exposure. Although they may naturally occur in soils at levels that are not harmful to health, human activities—and sometimes natural processes—can increase their concentrations to levels that are hazardous to human health5,6.

The most important natural sources of PTEs—such as Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Zn, As, Mo, Cd, Sn, Ba, and Pb—identified in this study include bedrock, volcanic activity, and rock weathering. Current anthropogenic sources of pollution from these metals include industrial emissions, transportation, municipal activities, and agriculture. Particularly hazardous sources include mining, non-ferrous metal smelting, and themetallurgical and chemical industry, waste storage, the application of mineral fertilisers (especially with sewage sludge or phosphates), waste calcium, plant protection products, and surface runoff from heavily trafficked roads7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Each PTE, when present in excess, has a range of health consequences for humans5. Direct transfer of these elements through the food chain is illustrated in Fig. 17.

Pathways of heavy metal transport in the ecosystem7.

Soil contamination by potentially toxic elements (PTEs) has become a critical global concern due to its widespread occurrence, persistence in the environment, and significant implications for human health and food safety. Recent large-scale research by Hou et al.14 highlighted the alarming extent of this issue by analyzing over 796,000 soil samples across 1,493 regions worldwide14. Their findings estimate that approximately 14–17% of the world’s arable land—equivalent to more than 240 million hectares—is contaminated with toxic metals such as As, Cd, Pb, and others, posing a direct risk to 0.9–1.4 billion people. These areas, referred to as high-risk zones, include previously underestimated regions in low-latitude Eurasia, parts of South America, and the Middle East. The study clearly links soil contamination to both natural geological factors and human activities, including mining, industry, and intensive agriculture. Given that soil underpins more than 95% of global food production, such contamination not only endangers local ecosystems but also threatens global food security14.

Urban soils, although not directly involved in food production, are equally important due to their proximity to human populations and their role in public health, urban ecosystems, and recreational areas15. These soils are subject to increasing pollution pressure resulting from high population density, land use intensity, and a wide range of anthropogenic activities7,16. Unlike agricultural soils, where contamination often origin from fertilizers and pesticides, urban soil pollution is more closely associated with road traffic, industrial emissions, fuel combustion, construction waste, and historical land use17.

Multiple studies have confirmed that urban soils frequently contain elevated levels of PTEs such as Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, and Ni16,17. For example, in the urban soils of Kraków, the mean concentrations of Zn, Pb, and Cu exceeded geochemical background values by 2–3 times, particularly in forest glade areas with greater anthropogenic influence1. In many cases, the concentrations of these elements exceed both geochemical background levels and national safety thresholds15,18. Large-scale reviews of urban environments across Europe have shown that over half of the investigated sites exhibit anthropogenic enrichment of heavy metals15. Pb, for example, is consistently identified as the most concerning element, with maximum levels in some countries exceeding 600 mg/kg17. This poses a particular risk to vulnerable populations, especially children, due to their higher sensitivity to toxic exposure and frequent contact with contaminated soils in parks, playgrounds, and residential zones7,16.

Poland, with its diverse land-use patterns and ongoing transformation of both urban and rural areas, provides a unique context for investigating soil contamination. Urban areas such as Kraków experience intense anthropogenic pressures, while agricultural regions are subject to fertilizer and pesticide inputs. Despite these risks, comprehensive and updated national data on PTEs levels in soils remain limited, particularly for regions undergoing land-use change.

To address this gap, soil samples were collected from three representative locations within the Małopolska Province in southern Poland, an area known for its high environmental diversity and significant industrial legacy. The first site, Głogoczów, is a rural village located approximately 20 km south of Kraków, in proximity to Skawina, where the Skawina Metallurgical Plants operated between 1954 and 2001. The aluminum smelter located there had a documented degrading influence on soils, water, vegetation, fauna, and even historical monuments in Kraków19,20,21. Today, the site hosts the modern aluminum rolling mill NPA Skawina Sp. z o.o.

The second sampling point, Baranówka, is situated northeast of Kraków, just 8 km from the site of the former Lenin Steelworks, later transformed into the T. Sendzimir Steelworks, and currently operating under ArcelorMittal Poland. This area includes a metallurgical waste dump, where iron-bearing wastes and ashes are stored in sedimentation tanks, posing potential long-term contamination risks21.

The final location was Kraków, where samples were collected on the premises of the Oil and Gas Institute at 1 Bagrowa Street, situated in a heavily industrialized area of the city. The site is surrounded by key industrial facilities including the Kraków Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Plant, the Sewage Treatment Plant, and the Municipal Waste Incineration Plant. The city is also home to a wide range of industrial sectors, including metallurgical, chemical, pharmaceutical, machinery, electrochemical, food processing, printing, leather, and footwear industries.

Kraków, the second largest city in Poland in terms of population and area, is located in the southern part of the country within the Vistula River valley. The city lies in the Malopolska region and is characterized by a mild temperate climate, with average annual temperatures around 9 °C and approximately 650 mm of precipitation22,23. Air movement is typically aligned with the Vistula valley axis, with prevailing winds blowing from the west and east1,23. These climatic and geographical characteristics may influence the transport and accumulation of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in the soil. Wind patterns may also contribute to the dispersion of PM10 and other airborne particulate fractions, which can carry PTEs and lead to further environmental contamination1.

By targeting both agricultural and urban environments with known industrial legacies and active sources of anthropogenic pollution, this study aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of PTEs concentrations in southern Poland. The inclusion of historically contaminated sites allows for the evaluation of long-term environmental impacts, while current industrial zones help capture emerging contamination patterns. Given the proximity of urban soils to densely populated areas, especially in Kraków, the findings of this research have direct implications for public health and environmental risk management. Other researchers emphasizes that even recreational green areas, often perceived as safe, may pose exposure risks due to the accumulation of trace metals in topsoil layers accessible to the public, including children1.

This article focuses on the determination of selected PTEs in soils of different land uses—agricultural and urban—using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). This method was chosen due to its exceptional analytical parameters, including high sensitivity, accuracy, multi-element detection capability, and low detection limits, making it one of the most effective techniques for trace metal and metalloid analysis in environmental samples24.

A key feature of the proposed methodology is not only the high-precision chemical analysis, but also the emphasis on the quality of the entire analytical process, including sample collection. This aspect—often overlooked in similar studies—represents a major strength of the present work. The doubling method for sample collection was implemented in accordance with established quality standards and the recommendations of the Polish Association of Accredited Laboratories (POLLAB), enabling robust uncertainty estimation not only in the laboratory phase but also at the field sampling stage25.

The next stage of the study was method validation. The estimation of measurement uncertainty was conducted using classical ANOVA and its robust counterpart RANOVA, employing the ROBAN tool, which provided resilience to outliers and sample variability. Validation of the research method together with the sampling step as a subject of the investigation, directly affects the reliability of the obtained analytical results obtained. This analytical approach allowed for a comprehensive assessment of the contamination level in soilsand a comparison of the quality between agricultural and urban areas in south Poland. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate the contamination status of PTEs in both soil groups and to identify potential sources and correlations of these harmful elements.

The obtained concentration values were evaluated in reference to national regulations, particularly the Regulation of Minister of the Environment of 1 September 2016, which defines permissible levels of contaminants in soils, depending on their land-use calssification26. A detailed overview of the soil group classifications used in the evaluation is presented in Table 1, while the respective threshold values (limits) for PTEs are provided in Table 2.

This national framework was further supported by relevant European environmental directives and strategic guidelines26. These include documents issued by the European Environment Agency (EEA), which emphasizes the need for a harmonized approach to soil monitoring across EU Member States and the importance of integrating risk-based thresholds and indicators to asses soil health and contamination levels27. In parallel, the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission published a technical report highlighting methodologies for soil contamination assesment and stressing the urgency of aligning national monitoring systems with EU-wide environmental goals28. Although numerous studies have investigated soil contamination, dynamic development of agriculture and industry necessitates ongoing, updated analyses to reflect current environmental conditions. A critical factor in ensuring the reliability of such studies is the appropriate selection of analytical methods, combined with rigorous instrument validation and proper estimation of measurement uncertainty. These steps are essential to determine the suitability and accuracy of the technique used for identifying selected soil components.

Materials and methods

Soil sampling

The soil samples were collected using the doubling method, which involves taking duplicate samples at each site following the same procedures25. A minimum of eight randomly selected sites, representative of their typical land use (agricultural and urban), were chosen for sampling. From each site, duplicate samples were collected, processed into analytical samples, and subsequently used to produce two measurement samples. A schematic representation of the doubling method is presented in Fig. 2.

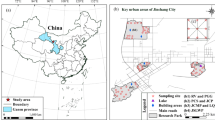

Agricultural soil samples were collected in Baranówka and Głogoczów, Poland in 2017, while urban soil samples were collected at 1 Bagrowa Street Krakow 30-733, Poland on 16 June 2021. The geographic locations were recorded using GPS coordinates and are presented on the map in Fig. 3. According to the classification provided in the Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 1 September 2016, fourteen agricultural soil analytical samples from Baranówka and Głogoczów were classified as Group II-1, while sixteen urban soil analytical samples from Bagrowa Street in Kraków were assigned to Group I 26. For clarity in further analysis, the agricultural samples were labeled 1A–14A (where "A" stands for “agricultural”), and the urban samples were labeled 1U–16U (with "U" indicating “urban”).

Geographic locations of the soil sampling sites. Agricultural soil samples (1A–14A) were collected in Baranówka and Głogoczów (2017), while urban soil samples (1U–16U) were collected at Bagrowa Street in Kraków (2021). Coordinates were recorded using a GPS receiver. The background map uses data from ©OpenStreetMap contributors (https://www.openstreetmap.org/). Map data available under the Open Database License (https://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/).

Preparation of soil samples for analysis

To ensure accurate chemical analysis, proper sample preparation procedures were followed in accordance with PN-ISO standards.

The collected soil samples (after first removing visible plant parts and stones) were dried to an air-dry state by spreading them on trays and leaving them in an airy place at room temperature. Once dried, the samples were sieved through a 1 mm mesh and gently crushed using a soft brush to obtain homogeneous, fine material for further analysis.

Determination of soil moisture content

The moisture content of the prepared soil samples was determined in accordance with the PN-ISO standards (ISO 11465. Soil quality—Determination of dry matter and water content of soil—Gravimetric method and ISO 75/C-04616.01. Water and sewage. Special studies of sludges. Determination of water content, dry matter, organic substances, and mineral substances in sewage sludge)29,30.

The procedure involved the gravimetric determination of water evaporated from the soil during drying to a constant mass at 105 °C. To ensure accuracy and repeatability, the following equipment was used: an analytical balance XP250DR with a precision of 0.1 mg, a laboratory dryer KBC-125G with adjustable temperature settings, and a desiccator for sample cooling and stabilization.

First, clean glass evaporating dishes were prepared and weighed using the analytical balance. Each dish was placed on the pre-tared and stabilized balance, and the mass was recorded. During weighing, ambient temperature and relative air humidity parameters were also noted. This procedure was repeated identically for all evaporating dishes.

Subsequently, air-dried soil samples were weighed into the dishes in arbitrary amounts ranging from 1 to 10 g. For each type of soil, two separate subsamples (replicates) were prepared. The mass of each dish with its respective soil sample was then recorded.

The dishes containing soil were then placed in the KBC-125G dryer and subjected to drying at a constant temperature of 105 °C for 1 h, or until a constant mass was achieved. After drying, the samples were immediately transferred to a desiccator and left for 30 min to cool down to room temperature. Following this stabilization period, each dish was reweighed promptly to minimize moisture reabsorption from the air.

The water content (X) in each sample was calculated relative to the dry mass, using the following formula (1):

where \({m}_{0}\)—mass of the empty dish [g], \({m}_{1}\)—mass of the dish with air-dried soil [g], \({m}_{2}\)—mass of the dish with oven-dried soil [g], For each soil sample, the mean water content was calculated based on the two subsamples, and the absolute difference between the two values was determined to assess reproducibility.

All calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel. The results obtained for each sample are summarized in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials.

Acid digestion of soil samples

Soil samples were subjected to microwave-assisted acid digestion following the procedure outlined in PN-ISO 1146631 .The method of acid digestion in a closed microwave system involves converting solid samples into aqueous solutions by destroying organic matter while retaining analytically determinable elements. To determine the metal content of the tested soils, it is necessary to process the samples accordingly. The first step involved milling the samples in a FRITSCH planetary micro mill pulverisette 7. Milling was carried out using two ceramic vessels in which grinding balls were evenly distributed, and then covered with the soil sample up to 2/3 of the container’s volume. The vessels were sealed with lids and gaskets and positioned opposite each other in the chamber, tightly fixed to ensure they remained closed and stable throughout the 15-min grinding process. After milling, the samples were transferred into separate containers for further processing.

Previously prepared soil samples were measured in quantities of approximately 0.5 g using an XP250DR analytical balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg, and their mass was recorded. The samples were then placed in high-pressure digestion vessels, and acids were added in the following proportions: 9 ml HNO3, 1 ml HF, and 2 ml HCl. After allowing the mixtures to stand for 10 min to initiate the reaction, the containers were sealed and placed into a MARS 6 microwave digestion system, where the digestion was performed at a temperature of 180 ± 5 °C for 9.5 min. Once the process was completed, the samples were left in the digester to cool. The contents of the containers were then quantitatively transferred to 100 ml volumetric flasks and filled to the mark with demineralized water. The procedure was carried out twice for each soil sample, meaning that two independent digestions were conducted per sample to ensure reproducibility and data reliability.

Determination of PTEs content in mineralized soil samples by ICP-MS

The ICP-MS technique was used for the determination of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in digested soil samples.

This method allows for high sensitivity, selectivity, and speed of analysis, low detection limits, and enables multi-element analysis.

Analyses were carried out using an Agilent ICP-MS 7900 mass spectrometer equipped with MassHunter Workstation software, a standard MicroMist nebulizer, nickel cones, and a quartz torch (1 mm). The samples were introduced directly into the instrument using a peristaltic pump and 1.02 mm inner diameter tubing (sample flow rate was 0.346 ml min−1). Before and between analyses of AgNPs, the sample introduction system was rinsed with a mixture of 5% nitric acid and 3% HCl to avoid memory effects. Disposable polypropylene containers were used for all analyses.

Before and between analyses, the sample introduction system was rinsed with 5% nitric acid followed by demineralized water to avoid memory effects. The ICP-MS measurements were performed using the helium collision cell mode to minimize polyatomic interferences and improve accuracy.

The parameters of the ICP-MS mass spectrometer setup used for the analysis are presented in Table 3.

Certified reference materials (CRMs) were used for quality control and to validate the accuracy of the digestion and measurement processes. Each batch included a blank sample and duplicate CRM samples. The instrument was calibrated and tuned on the day of analysis using an Agilent tuning solution (1 µg L-1, Li, Co, Y, Tl, Ce, Ba in a 2% HNO3 solution).

The following CRMs were used in the study: The Sandy LoamSoil CRM standard (VHG-DS1-100G) which has a wide range of Cu, Ba, and Zn content and concentrations of Co, Mo, Sn, and Pb at undetectable levels and The Matrix Reference MaterialEnviroMATContaminatedSoil (SS1) standard, which served as a PTEs high-concentration reference. Calibration curves were prepared using multi-element standard solutions with know concentrations. The calibration was based on five concentration levels: 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 µg/L. The analytical parameters and expanded uncertainty (k = 2,95% confidence level) are presented in Table 4.

The limits of detection for all analyzed elements were determined based on replicate measurements of a certified reference material with concentrations close to the expected detection limits. Ten replicate measurements were performed, and the LOD was calculated as three times the standard deviation (3 × SD) of these measurements. The calculated LOD for all elements was 5 µg/kg (dry weight basis).

The same LOD value was adopted for all elements to ensure uniform and conservative reporting, considering the variability inherent to sample preparation and matrix effects in soil analysis. Although different elements may theoretically yield different detection limits due to instrumental sensitivity, matrix complexity in soil samples can introduce additional uncertainties. Therefore, a uniform LOD of 5 µg/kg for all analytes provides a consistent and reliable threshold for data interpretation and minimizes the risk of underestimating uncertainty for specific elements. Moreover, this level of detection is sufficient for the purpose of the present study, which focuses on assessing contamination levels in soils where analyte concentrations are typically well above this threshold.

Since the moisture content of the soil samples had already been determined, it was possible to convert the ICP-MS results, originally expressed in mg/L, into concentrations in mg/kg of dry weight. The measured metal concentrations were first recalculated for the final digest volume of 100 mL. Knowing the mass of the digested sample and its moisture content (X), the concentrations per dry weight were calculated using the following formula:

where 0.1—final volume of the digest (in litres), \({m}_{sample}\)—mass of the soil sample used for digestion (in grams),

The final results of all determined PTE concentrations in the analyzed soil samples are presented in Tables S3 and S4, available in the Supplementary Materials..

Table S3 contains data for agricultural soils (samples 1A–14A), while Table S4 presents results for urban soils (samples 1U–16U).

Estimation of uncertainties in soil sampling, analytical processes, and measurement

In this study, to assess soil quality and compare the results obtained of PTEs concentration with the threshold values mentioned in the Regulation26), both the uncertainty of soil sampling and the uncertainty of the analytical process were estimated. Ignoring uncertainty can have a crucial impact on incorrect decisions made after the analysis. For this reason, uncertainty should always be determined32. The estimation of measurement uncertainty is a fundamental part of data validation in environmental analysis and supports regulatory compliance as well as scientific credibility of results.

Uncertainty due to sampling can significantly affect the total uncertainty of the obtained analysis results and can be caused, among other things, the heterogeneity of the analyzed area, the physical state of the sampled material, temperature and pressure, or the transport of the samples. It may also arise from factors such as sampling technique, storage conditions, or unintended contamination, all of which can influence sample integrity. In addition, total measurement uncertainty is also influenced by factors related to sample preparation (e.g., sample homogeneity, digestion efficiency, weighing accuracy) and instrumental analysis, including instrument stability, calibration, signal drift, and matrix effects. Using the doubling method, it was possible to estimate the reliability of the data obtained on the basis of uncertainty and to validate the method with the sampling step. In this method, two subsamples are collected from each sampling location and subjected to independent digestion and analysis, which enables separate evaluation of variability introduced at each stage.

To estimate the overall uncertainty, the ROBAN software32 (Royal Society of Chemistry, n.d.) was used. The choice of this programme was justified by its implementation of the algorithms of ANOVA—classical analysis of variance and robust ANOVA (RANOVA) statistics method allowing for 10% outlier results to be included in the analysis25,32. This software enables partitioning of total variance into geochemical variance, sampling variance, and analytical variance, and provides quantitative indicators of uncertainty based on robust statistical methods.

These algorithms rely on calculating the arithmetic mean of the obtained results, which can be significantly influenced by the presence of outliers in the data set. In the results included in this the number of deviations does not exceed 10%, but outliers may occur. Robust ANOVA (RANOVA) is particularly useful in environmental studies because it provides reliable estimates even when data contains slight deviations from normality or heteroscedasticity. To interpret the results obtained, the uncertainty determined using a robust RANOVA analysis of variance. By using the results of the analysis of variance, it was possible to determine parameters such as the total and sampling variance, the standard and expanded uncertainty for the 95% confidence interval, as well as the components and the relative uncertainty of the measurement result32.

The ROBAN program determines individual variance components and their percentage contribution to the total value. The total variance (\(\sigma_{total}^{2}\)) was expressed by Eq. (3)25:

where \(\sigma_{geoch}^{2}\)—geochemical variance (due to natural heterogenity of the environment), \(\sigma_{sampl}^{2}\)—sampling variance (caused by the method of collecting samples), \(\sigma_{anal}^{2}\)—analytical variance (introduced during laboratory analysis),

In practice, population variances are replaced by their estimates (\(s_{total}^{2}\)), which gives Eq. (4)25:

where \({s}_{geoch}\)—variability between sampling sites (geochemical variability), \({s}_{sampl}\)—variability between samples (precision of sample collection), \({s}_{anal}\)—variability between repeated measurements, reflecting analytical precision,

The standard measurement uncertainty (\({u}_{meas})\) was calculated using the square root of the sum of the sampling and analytical variances as in Eq. (5)25:

where \({s}_{meas}\)—combined standard uncertainty of the measurement, resulting from both sampling and analytical steps,

The expanded uncertainty (\({U}_{meas})\) at 95% confidence level is expressed as25:

Relative expanded uncertainty (\(U_{meas}^{\prime }\)), used to evaluate the uncertainty as a percentage of the mean result, is calculated by25:

where x is the mean concentration of the analyte in the sample.

Individual components of uncertainty can also be expressed as25:

These formulas provide a comprehensive quantitative overview of uncertainty sources and allow their contribution to the final result to be compared and interpreted. This structured uncertainty analysis strengthens the reliability of conclusions drawn from the study and supports the use of data for risk assessment or regulatory reporting.

The results of uncertainty estimation using the ROBAN software for agricultural soil samples (1A–14A) and urban soil samples (1U–16U) are presented in Supplementary Tables S5–S17.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a multivariate statistical technique commonly used in environmental studies to reduce the dimensionality of complex datasets while preserving as much variability as possible. This method transforms the original, possibly correlated variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components. The first principal component (PC1) accounts for the maximum variance in the data, followed by the second principal component (PC2), which explains the next highest variance, and so on. This enables the identification of underlying patterns and relationships between variables, such as grouping of samples and potential sources of pollution33.

In the present study, PCA was employed to explore the associations between potentially toxic elements (PTEs) and to visualize the differentiation between agricultural and urban soils based on their elemental composition. The analysis was conducted using the XLSTAT 2025.1.1 software, as an add-in to Microsoft Excel.

Before applying PCA, the raw concentration data of selected elements were normalized using z-score standardization, where each value was transformed by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for the corresponding element. This ensured that variables with different units and ranges contributed equally to the analysis. Separate PCA was performed using only the elements common to both soil types to enable direct comparison and avoid bias resulting from unequal variable representation. The input dataset was prepared as a matrix of observations (individual soil samples) and variables (standardized values of selected PTEs), and the correlation matrix was used as the basis for the PCA.

Additionally, sample labels and grouping information (agricultural or urban origin) were included to facilitate the interpretation of spatial clustering patterns on the PCA plots. Biplots were generated to illustrate the relationships between variables and samples in a two-dimensional space defined by the first two principal components.

The results of the analysis are presented in Fig. 4 (score plot) and Fig. 5(loading plot).

Results

In order to compare the obtained relative expanded uncertainties of soil sampling, analytical procedure, and measurement for soil samples from agricultural and urban areas, appropriate graphs were included in Figs. 6 and 7. These comparisons refer to Cr, Co, Ni, As, and Ba determined in agricultural soils, and to Cr, Co, Ni, Mo, Cd, Sn, Ba, and Pb determined in urban soils.

The determination of metal content excluded Zn, Sn, and Cu in agricultural soil, as well as Cu in urban soil. The reason for the lack of estimation was that the obtained results were below the method’s limit of quantification of the method (the number of results to be evaluated was insufficient due to too low metal concentrations in the samples).

Furthermore, this study omits extended relative uncertainty values for the determination of Mo, Cd and Pb in agricultural soils and Zn and As in soil from an urban area. The estimation for the aforementioned metals was rejected due to inconclusive results and an insufficient number of repetition of the analysis. Additionally, the complexity of sample preparation for the study may also have influenced the results.

In the study, for all determined metals in both urban and agricultural soil samples, the largest contribution to total variance originated from the variation between sampling sites. Following the established limit values according to the POLLAB Club Information Bulletin25, in order to be able to confirm the reliability of the results of the determination of metals in soils, the value of the relative expanded uncertainty of measurement, sampling, and analytical process should not exceed 30%.

The relative expanded uncertainty was determined for the measurement of metal content in soils at a 95% confidence interval, with k = 2. Combining the contributions from sampling and the analytical process, it follows that the relative expanded uncertainty for the entire measurement process does not exceed the limit of 29.06%, which determined the reliability of the results obtained. The relative expanded uncertainty of the analytical procedure varies between 3.37% and 20.27%, which is the basis for determining the suitability of the technique used for the determinations of selected elements..

The greatest contribution to the total uncertainty for agricultural and urban soil samples is the uncertainty due to the sampling step. It ranges from 8.92% to 25.11% for agricultural soils and from 4.00% to 25.11% for urban soils, respectively. The study and estimation results showed that the double sampling method and the analytical process of elemental determination by the ICP-MS method used during the analyses carried out meet the requirements for the reliability of the results. The validation of the method proceeded correctly, which is the basis for the correctness of the analysis.

Assessment of soil contamination status

For the purpose of verification whether the determined values of metal concentrations in the investigated soil samples are within the limits of the permissible content of substances (given in the Regulation26), the results identified as reliable—without taking outliers into account—were compared to the values assigned for the respective land groups (presented in Table 5).

Regarding the samples from the agricultural area, after the identification of outliers and their rejection in the analysis, the determined values of Cr, Co, Ni, and As were found to be within the permitted limit according, and their concentrations in the soil do not pose an environmental hazard.

The average Ba content in agricultural soil, after rejecting outliers, is 418.54 mg kg−1 dry weight, while the maximum permissible value of Ba for soil group II-126 is 200 mg/kg dry weight. The resulting concentration of this element in the soil is 209.27% of the limit value standard, which means that Ba is present in the agricultural soil in excessive amounts.

For samples from the urban area (group I26), after proper identification of outliers and their rejection in the analysis, it was found that the determined values of Cr, Co, Ni, Mo, Sn, and Pb are within the permissible content and their concentration in the soil does not pose an environmental risk.

The average contents of Cd and Ba in urban soil, after rejection of outliers, were 5.84 mg kg−1 dry weight and 458.89 mg kg−1 dry weight, respectively.

The limit value for the Cd content for soil group I is 2 mg kg−1 dry weight, while Ba for the same group is 400 mg kg−1 dry weight.

The concentrations of both Cd and Ba exceed the limits established in the Regulation26. The resulting Cd concentration is as much as 292% of the standard of the limit value, while the Ba concentration reaches 114.72% of the limit.

A comparative analysis of average metal concentrations revealed that Ba, Cr, and Ni were present in higher amounts in urban soils than in agricultural ones. In contrast, Co was found in slightly higher concentrations in agricultural soils (6.85 mg/kg) compared to urban soils (6.51 mg/kg). These findings confirm that urban areas are generally more exposed to pollution from anthropogenic sources such as traffic and industry.

Identification of grouping patterns and PTEs associations via PCA

In the present study, PCA was performed based on the concentrations of a selected group of PTEs: Ni, Co, Ba, and Cr. These elements were chosen due to their presence in both urban and agricultural soils and the reliability of their measurement results. The analysis yielded two principal components (PC1 and PC2), which together explained 85.63% of the total variance — with PC1 accounting for 60.46% and PC2 for 25.17%.

On the score plot (Fig. 4), urban soil samples (particularly 7U1, 7U2, 8U1, and 8U2) were clustered on the right side of the PC1 axis, indicating higher PC1 values and greater variability, reflecting elevated concentrations of Ni, Cr, and Co.

In contrast, agricultural samples tended to form more compact and distinct groupings, mostly distributed on the left side of the PC1 axis. The most clearly separated and cohesive clusters were observed among the following agricultural samples: 13A1, 13A2, 14A1, 14A2, 3A1, 3A2, 6A1, 6A2, 9A1, 9A2, 10A1, 10A2, and 4A2.

The biplot (Fig. 5) showed that Ni, Cr, and Co vectors were strongly aligned with PC1, correlating positively with urban samples and contributing most to their separation. Ba was distinctively aligned along the PC2 axis, indicating a different variance pattern compared to the other elements. This distribution pattern implies that Ni, Co and Cr were the most influential in differentiating urban soils from agricultural soils along PC1. Ba introduced additional variation along PC2, affecting both land use types without being exclusive to either. Overall, the PCA results revealed a clear spatial separation between urban and agricultural soils, driven mainly by Ni, Cr, Co, whereas Ba contributed orthogonal variance, indicating a distinct contamination pattern.

Discussion

In urban soils, the Cd concentration reached as much as 292% of the permissible limit, while Ba exceeded the threshold by 14.72% (114.72% of the limit value). In agricultural soils, only Ba exceeded the permissible value, reaching 209.27% of the established limit. Exceeding the maximum permissible limit value for Ba in samples from both groups of areas and Cd in samples from the urban area can have a negative impact on the environment. According to the Regulation, these exceedances pose a threat to both soil and human health13,34.

Cd is considered the second most dangerous element after lead for both plants and humans35,36. Plants absorb it relatively easily with an intensity directly proportional to its concentration in the environment. Very large amounts of this element accumulate in celery root and leaves, lettuce, carrots, potatoes, broccoli, and cauliflower. It is worth noting that when other elements are present in the soil, the absorption of PTEs into organisms can be variable. For example, copper and zinc reduce the amount of Cd in plants, while lead and iron increase its concentration. In addition to disrupting photosynthesis, Cd can affect the metabolism of nitrogenous compounds, decrease the CO2 uptake capacity, alter the permeability of the cell membrane and DNA structure. The result is twisted leaves, thickened roots and shortened plants35. Plants containing the accumulated Cd in their tissues enter the human body in the form of food. Drastic consequences of the accumulation of large amounts of Cd in the human body are birth defects such as cerebral hernia, hydrocephalus, missing eyes, cleft palate or missing metatarsal bones35. It also causes kidney, intestinal and liver damage, anaemia, hypertensive disease and cancer.

Ba, as a chemically reactive element, belongs to the PTEs group34. It can be harmful to plants in concentrations that far exceed acceptable standards. Its effects on human health are very serious, as even small doses of Ba can cause muscle weakness, paresthesias, flaccid paralysis, cardiovascular disorders, or ventricular arrhythmia. Ba compounds delivered with food via the oral route manifest as acute gastrointestinal distress, muscle weakness and progressive paralysis. Acute renal failure, dysphagia, and hypertension can also occur. A lethal dose of Ba (approximately 10 mg BaCl kg−1 body weight) causes respiratory and cardiac arrest34. It is also worth noting that the toxicity of Ba depends on the water solubility of its salts. Highly soluble compounds—such as BaCl2, Ba(NO3)2, and BaCO3, are considered highly toxic, whereas poorly soluble salts likeBaSO4, are regarded as practically harmless to human health13.

There are many pathways of exposure to PTEs. Those mentioned include the possibility of ingestion of soil, skin contact or inhalation of wind-blown soil dust. Oral pathways of exposure are particularly relevant, especially for children given their still-developing bodies and behaviors such as playing on the ground and putting their hands in their mouths 1,16.

One of the primary sources of environmental pollution associated with human activities is vehicular traffic and industrial operations17. Soil contamination is most pronounced in areas with high traffic density, such as city entrances, urban centers, and highways15. The presence of railway and bus station, as well as ports, further contributes to elevated concentrations of PTEs in soils18. Proximity to the sea, industrial activity, metal ore extraction, and even residential heating with fireplaces can influence soil contamination18,37. Additionally, researchers emphasize the significance of geological substrates as a source of metals in the soil. Certain PTEs often originate from natural sources such as ultramafic, metavolcanic, and igneous rocks17.

Soil contamination with potentially toxic elements (PTEs) is a widespread issue, particularly in urban areas. A clear positive correlation has been observed between population density and PTE concentrations, underscoring the significant human impact on soil quality areas18,38. The results of this study were compared with data from Gąsiorek et al., who analyzed soil from Planty Park in the center of Krakow39. The Cd content in the urban soils examined in this study was significantly higher (5.84 mg/kg) compared to Planty Park (0.80 mg/kg), which may indicate stronger or more recent sources of contamination39. Similarly, Cr and Ni concentrations were also higher—45.48 mg/kg and 22.95 mg/kg, respectively—compared to 16.3 mg/kg for Cr and 10.5 mg/kg for Ni in the park. An opposite trend was observed for Pb, with an average content of 32.19 mg/kg in the current urban samples and as much as 120.2 mg/kg in Planty Park, possibly due to long-term accumulation of this element in the historical city center39. These differences highlight the variability of contamination sources within urban areas and emphasize the need for ongoing localized monitoring to effectively manage soil quality.

The average concentrations of metals in urban soils from Kraków clearly exceeded the values of mobile metal fractions reported in another city in Poland, Łódź40. The content of Cd reached 5.84 mg/kg in Kraków, compared to only 0.34 mg/kg in Łódź. Similarly, Ni (22.95 mg/kg in Kraków vs. 2.10 mg/kg in Łódź) and Pb (32.19 mg/kg vs. 21.6 mg/kg) were also higher in the Kraków samples40. These findings indicate a higher degree of metal contamination in Kraków's urban soils compared to Łódź, which may be attributed to differences in emission sources, urban development history, and local environmental conditions.

Further evidence supporting the elevated contamination levels in Kraków’s urban soils comes from a recent comprehensive study comparing soils from Kraków, Lublin, and Toruń41. In that study, the highest average concentrations of Cd (5.5–7.7 mg/kg), Ni (37.4 mg/kg), Cr (up to 1021.7 mg/kg), Zn (up to 452 mg/kg), and Pb (80.4 mg/kg) were also observed in Kraków’s industrial and traffic areas41. These values are consistent with the findings of the present study, where mean concentrations of Cd (5.84 mg/kg), Ni (22.95 mg/kg), and Pb (32.19 mg/kg) were determined. Although some differences in sampling locations and analytical focus exist, both datasets point to Kraków as an area with substantial PTEs accumulation in urban soils, likely resulting from long-term anthropogenic pressure and high-intensity land use19,20,21,41.

A recent study conducted in urban parks of Sosnowiec revealed significant contamination of the topsoil with potentially toxic elements (PTEs), particularly Cd, Pb, Zn, As, Ba, and Sr, in almost all sampled locations42. The highest concentrations of these elements were recorded in parks situated near residential streets and historical industrial zones, such as Kruczkowski Park and Dietla Park, where Cd exceeded recreational soil limits by up to 19 times and Pb by 10 times42. Although the total concentrations of Cr, Cu, Co, and Ni remained within acceptable levels, environmental indices such as the geoaccumulation index and enrichment factor confirmed moderate to very high pollution levels, especially for Cd, Pb, and Zn. The sources of contamination were attributed to historical mining and metallurgy, traffic emissions, coal combustion, and park maintenance activities42. These findings are consistent with the results of the present study, where elevated levels of Cd (5.84 mg/kg), Pb (32.19 mg/kg), and Ba (458.89 mg/kg) were also identified in urban soils. This supports the conclusion that urban pressure and industrial legacy remain major contributors to soil pollution in southern Poland19,20,21,42.

The results of this study were compared with the most recent data on global agricultural soil contamination with toxic elements14. As, detected in agricultural soil samples at a concentration of 6.77 mg/kg, did not exceed the permissible limits, confirming its relatively low prevalence—exceedances were reported in only 1.1% of samples worldwide14. The mean concentrations of Cr (41.65 mg/kg), Co (6.85 mg/kg), and Ni (14.54 mg/kg) in agricultural soils remained well below threshold values, which aligns with global findings indicating that only a small percentage of samples exceed the limits (3.2% for Cr, 1.1% for Co, and 5.8% for Ni, respectively)14.

According to other sources and extensive research, agricultural areas remain contaminated with PTEs throughout Europe. The sources of this pollution are related to metal ore mining areas. Compared to other European countries, Poland is relatively unpolluted and has a low content of PTEs in agricultural soils37. It is among the countries that actively conduct and publish research on soil contamination by PTEs. For many other European countries, significant data gaps have been identified, which can make it difficult to assess the extent of environmental pollution. Given the limited knowledge on PTEs contamination of soils in many European countries, further standardized research is needed to fill these data gaps and develop effective soil protection strategies on a continental scale17.

Numerous studies have shown that soils in natural areas located near urban centers are almost as contaminated as green spaces within cities. This indicates that pollutants generated in urban environments can migrate into adjacent natural ecosystems, posing serious implications for environmental protection38. It is particularly important to recognize that pollutants such as PTEs, pesticides, and microplastics are capable of long-distance transport and can affect remote soils. For example, contamination has been documented even in Antarctica—a region with minimal infrastructure—as a result of pollutant migration via marine currents and atmospheric transport pathways15,38. This highlights the global reach and persistence of soil contaminants.

This phenomenon is also evident on a local scale in Kraków, as documented by Sołek-Podwika and Ciarkowska (2024), who reported elevated concentrations of Cd, Ba, and Pb in recreational forest soils, including areas located far from direct emission sources1. This suggests lateral transport of pollutants via air, surface water, or soil erosion. The accumulation of these metals was particularly pronounced in areas adjacent to roads and public spaces, and notably in the upper soil layers—the zones most accessible to human contact—thereby increasing potential exposure risks. Increased Cd concentrations were observed not only in zones of intense anthropogenic activity, but also in seemingly remote forest glades used for leisure, which reflects both the long-term environmental persistence of these pollutants and their capacity for ecosystem-wide migration1.

Although the present study focused on a different set of land-use types—namely urban and agricultural soils—the findings are consistent with the overall contamination patterns observed by Sołek-Podwika and Ciarkowska1. In our study, Cd concentrations in urban soils reached 5.84 mg/kg, exceeding the regulatory threshold by 292%, while Ba levels were recorded at 458.89 mg/kg in urban soils and 418.55 mg/kg in agricultural soils, both surpassing their respective limits (400 mg/kg for urban and 200 mg/kg for agricultural soils). For comparison, Sołek-Podwika and Ciarkowska reported Cd concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 4.2 mg/kg and Ba concentrations between 290 and 410 mg/kg in forest and glade soils, depending on vegetation cover and elevation1.These similarities, despite differing land-use categories, suggest that anthropogenic pressures in Kraków affect a wide spectrum of soil environments, including recreational, forested, urban, and agricultural areas. These findings underscore the persistence and mobility of potentially toxic elements in urban environments and highlight the need to account for spatial contamination dynamics in environmental protection strategies.

Climate change can affect the mobility and bioavailability of PTEs in soil, potentially worsening contamination in both urban and agricultural areas14. PCA analysis confirmed the presence of distinct groupings between agricultural and urban soils, which could be linked to different contamination profiles and pollution sources.

Urban soil samples (particularly 7U1, 7U2, 8U1 and 8U2) tended to cluster on the right side of the PCA biplot (Fig. 4), corresponding to higher values of PC1 and elevated concentrations of Ni, Co, and Cr. This distribution suggests a significant influence of traffic and industrial emissions, which is consistent with findings from other studies conducted in Kraków and other Polish cities, where elevated levels of Cr and Ni were observed in urban areas exposed to intensive anthropogenic activity 41,42.

A similar pattern was reported in a study of urban soils in Lisbon, where PCA revealed strong associations between Pb, Cr, Ni, and Cd. In that study, Cr and Ni were linked both to vehicular traffic, and the parent material of the soil, indicating mixed natural and anthropogenic sources15. These findings further support the interpretation of our PCA results.

Although Co was not always directly addressed in these studies, its co-occurrence with Cr and Ni in our PCA results—despite lower overall concentrations in urban samples—may suggest similar pollution sources or transport mechanisms. According to the findings of the present study, average Co concentrations were 6.85 mg/kg in agricultural soils and 6.51 mg/kg in urban soils, remaining within permissible limits and not posing an environmental risk.

Similar conclusions were drawn in a meta-analysis of soils in Sudan, where Co levels were higher in agricultural soils, than in industrial areas (59.0 ± 53.4 mg/kg and 58.2 ± 6.89 mg/kg respectively), suggesting lower concentrations in specific types of urban land use5. In contrast, a study conducted in the Greek city of Volos reported a much higher average Co concentration of 22.56 mg/kg in urban soils, indicating clear contamination, particularly near transport infrastructure18. These comparisons support the conclusion that soils in Poland are relatively less contaminated with cobalt than those in selected European and African regions.

On the PCA biplot (Fig. 5), Ba strongly loaded on the second principal component (PC2), indicating that its distribution pattern differed from elements such as Cr, Co, or Ni, which were more aligned with PC1 and urban samples, where consist in exceeding values. Although Ba was not explicitly included in PCA analyses in previously cited studies, its presence in our results suggests a distinct contamination source or behavior. The upward direction of the Ba vector on the biplot suggests that it contributes to sample variance in a unique way.

While urban samples showed partial alignment with Ba, the element was not exclusive to one land use type, indicating widespread distribution. This finding aligns with previous research that reported elevated Ba concentrations in urban green spaces exposed to vehicular emissions and industrial activities42. Additionally, potential agricultural sources such as certain fertilizers or soil amendments may explain its high presence in rural soils. Together with its known toxicity at elevated doses, these results highlight the need for monitoring Ba levels in both urban and agricultural settings.

Agricultural samples formed more compact and clearly separated clusters (e.g., 13A1, 13A2, 14A1, 14A2, 3A1, 3A2, 6A1 and 6A2), with lower PC1 values, suggesting a lower degree of contamination (except Co) and a more homogeneous composition for the analyzed elements.

Our results support previous findings that vehicular traffic and industrial activities are major contributors to soil pollution43. These results are in line with global observations indicating that agricultural soils generally contain fewer pollutants than urban soils40,41.

The accumulation of PTEs in urban soils underscores the importance of sustainable urban planning and pollution control measures. Meanwhile, in agricultural regions, implementing soil remediation techniques and sustainable farming practices could mitigate the risk of PTEs uptake by crops. Given the significant impact of PTEs on human and animal health, as well as their effects on the environment, continued research and constant monitoring are strongly recommended to ensure the safety of life on Earth.

This article aimed to determine the content of Cr, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Mo, Cd, Sn, Ba and Pb, but these elements are not the only ones that pose a threat to human health and ecosystems. Other scientists have also studied other groups of elements, including platinum group metals (PGEs), which may have their origins in emissions from vehicle catalytic converters 44. Metals from platinum group have been found to metabolize in soil, which can lead to bioavailable forms. There is a need for continuous research on soil contamination with platinum group metals over large areas due to the growing environmental problem associated with their presence 44. Worth mentioning is also the problem of the presence of neurotoxic mercury in urban and agricultural soils, which is also an alarming problem, especially in the context of public health 16. The above mention underscores the importance of research on the content of contaminants in soils and may inspire the expansion of this article’s research in the future. Also, it may be important to create maps based on pollution indicators, which can be a valuable tool for monitoring and managing pollution 18. Such visual tools not only support decision-making in urban planning and environmental management but also enhance communication of environmental risks to local communities1.

In cases where soil contamination is detected, it is recommended to implement measures aimed at improving soil quality. One of the effective approaches to improving soil quality and mitigating the risks associated with potentially toxic elements contamination involves the use of organic amendments that enhance soil properties and reduce metal bioavailability. Wheat straw, as an organic amendment, can alter soil pH and provide organic matter that binds PTEs into stable complexes, thereby decreasing their mobility and bioavailability in contaminated soils 45. Research indicates that wheat straw can be an effective tool for improving soil quality, including soils contaminated with PTEs such as Cd. Wheat straw alters soil pH, which influences the solubility and mobility of substances in the soil. It affects the mobility and bioavailability of PTEs in the soil45. Additionally, it serves as a source of organic matter that can bind PTEs into complexes, thereby reducing their bioavailability45. Similar mechanisms may potentially apply to Ba, however, no confirmed data is available on this subject.

In addition to organic amendments, phytoremediation and bioremediation are promising, environmentally friendly strategies for soil restoration. Phytoremediation uses specific plant species capable of accumulating, stabilizing, or transforming toxic elements, making it suitable for large-scale, cost-effective applications. Bioremediation relies on the metabolic activity of soil microorganisms, which can degrade or immobilize pollutants, and is often used in combination with phytoremediation in integrated remediation strategies. These approaches offer sustainable alternatives to more conventional methods.

Other soil remediation methods, particularly those involving physical or chemical interventions, are associated with high economic costs. For this reason, within environmental protection strategies, remediation techniques should be considered a last resort. The primary focus should remain on preventing contamination by reducing the emission of harmful compounds into the ecosystem46. Ultimately, the findings of this study reinforce the need for integrated, long-term soil protection policies that combine monitoring, prevention, public awareness, and targeted remediation when necessary.

Limitations of the study

Despite its broad scope, this study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size—14 agricultural and 16 urban soil samples—while sufficient for a preliminary assessment, may limit the representativeness of the findings for the entire region5,41. Additionally, all samples were collected during a single season, which does not account for seasonal variability in the mobility and accumulation of metals in soil47. Another limitation is the lack of long-term monitoring data, which would allow a better understanding of temporal trends and help distinguish background levels from recent pollution episodes39,40,41.

From a methodological perspective, the study did not include speciation analysis, which restricts the ability to evaluate the bioavailability and environmental behavior of the metals. Furthermore, while the use of ICP-MS ensured high sensitivity, the findings could be strengthened by complementary analytical techniques or quality control inter-laboratory comparisons.

Future research should consider increasing the number of sampling locations and incorporating seasonal and multi-year sampling, in order to better capture the dynamics of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in various land-use types27. Expanding the study area and including plant uptake analysis or human health risk modeling could further support the assessment of ecological and health-related threats posed by soil contamination6,16,47.

Conclusions

The conducted study revealed exceedances of permissible metal concentrations in both urban and agricultural soils, particularly for Cd and Ba. In urban soils, cadmium reached 5.84 mg/kg (limit: 2 mg/kg), while barium reached 458.89 mg/kg (limit: 400 mg/kg). In agricultural soils, only barium exceeded the threshold, reaching 418.55 mg/kg (limit: 200 mg/kg). It strongly highlights the potential environmental and health risks associated with excessive metal accumulation.

The results were compared with literature data on urban soils from other Polish cities, including Kraków, Łódź, Sosnowiec, Lublin, and Toruń. It was observed that Cd, Ni, and Pb concentrations in the samples from Kraków were higher than in other locations, confirming the considerable anthropogenic pressure in this region. The mobility and persistence of these pollutants were also confirmed, as they were detected even in forests and recreational areas located far from emission sources.

A novel contribution of this study lies in the simultaneous analysis of urban and agricultural soils from the same geographical region using the ICP-MS technique, combined with an in-depth environmental risk assessment in the context of current legal regulations. The entire analytical procedure was thoroughly validated, including the determination of detection limits, assessment of precision, accuracy, and measurement uncertainty, using certified reference materials and statistical tools such as analysis of variance and the ROBAN software. Particularly important is the identification of the potential for toxic element migration between different land-use types and their accumulation in the topsoil layer.

In addition, principal component analysis (PCA) provided a valuable multivariate perspective that clearly differentiated between urban and agricultural soil samples and elucidated distinct metal distribution patterns. Urban soils—particularly samples 7U1, 7U2, 8U1, and 8U2—were associated with higher PC1 values and elevated concentrations of Ni and Cr, which is consistent with anthropogenic pollution sources such as traffic and industrial activity. A similar pattern has been reported in other studies, including research from Kraków and Lisbon, where Cr and Ni were strongly associated with urban contamination profiles. Interestingly, Co—despite being statistically grouped with Cr and Ni on the PCA biplot—was present at higher concentrations in agricultural soils, possibly indicating natural geochemical origin or the influence of rural land use. Ba, on the other hand, strongly loaded on PC2, suggesting a different distribution pattern and contamination source, with significant concentrations observed in both urban and rural areas. Its behavior highlights the importance of monitoring Ba levels, given its high toxicity and widespread presence. The obtained data may be applied in spatial planning, the management of green and agricultural areas, and the development of local environmental protection strategies. They also highlight the necessity of implementing preventive measures, such as emission reduction, ongoing soil monitoring, and the consideration of biological remediation methods—for example, the use of wheat straw to reduce the bioavailability of Cd.

Data availability

The data supporting the reported results are collected on the disc. They can be shared upon request, from the corresponding author, K. Styszko, styszko@agh.edu.pl.

References

Solek-Podwika, K. & Ciarkowska, K. Sources of the Trace Metals Contaminating Soils in Recreational Forest and Glade Areas in Krakow, a Large City in Southern Poland. Sustainability (Switzerland) 16, (2024).

Zhou, D., Lin, Z. & Liu, L. Regional land salinization assessment and simulation through cellular automaton-Markov modeling and spatial pattern analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 439, 260–274 (2012).

Piwowar, A. Micronutrients in plant production and the agricultural environment: agricultural, chemical, and market perspectives (in polish). Chem. Ind. 100, 53–56 (2021).

Duffus, J. H. ‘Heavy metals’ a meaningless term? (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 74, 793–807 (2002).

Siddig, M. M. S., Brevik, E. C. & Sauer, D. Human health risk assessment from potentially toxic elements in the soils of Sudan: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 958, 178196 (2025).

Nde, S. C. et al. Human health risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in soils and rice grains (Oryza sativa) using a combination of probabilistic indices and carcinogenic risk modelling. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 18, 100664 (2025).

Ociepa-Kubicka, A. & Ociepa, E. Toxic impact of heavy metals on plants, animals, and humans (in polish). Environ. Eng. Prot. 15, 169–180 (2012).

Ociepa, A., Pruszek, K., Lach, J. & Ociepa, E. Influence of long-term cultivation of soils by means of manure and sludge on the increase of heavy metals content in soils. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S. 15, 103–109 (2008).

Gouder de Beauregard, A. C. & Mahy, G. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: The role of macrophytes in a stormwater basin. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2, 289–295 (2002).

Vásquez-Murrieta, M. S., Migueles-Garduño, I., Franco-Hernández, O., Govaerts, B. & Dendooven, L. C and N mineralization and microbial biomass in heavy-metal contaminated soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 42, 89–98 (2006).

Bień, J. Sewage Sludge: Theory and Practice (in Polish) (Czestochowa Univ. of Technol, 2007).

Sas-Nowosielska, A. Phytotechnologies in the Remediation of Areas Contaminated by Zinc-Lead Industry (in Polish) Vol. 189 (Czestochowa Univ. of Technol, 2009).

Kabata-Pendias, A. & Pendias, H. Biogeochemistry of Trace Elements (in Polish) (PWN Publishing, 1993).

Hou, D. et al. Global Soil Pollution by Toxic Metals Threatens Agriculture and Human Health. https://www.science.org.

Silva, H. F., Silva, N. F., Oliveira, C. M. & Matos, M. J. Heavy metals contamination of urban soils—A decade study in the city of Lisbon. Portugal. Soil Syst. 5, 27 (2021).

Penteado, J. O. et al. Health risk assessment in urban parks soils contaminated by metals, Rio Grande city (Brazil) case study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111737 (2021).

Binner, H., Sullivan, T., Jansen, M. A. K. & McNamara, M. E. Metals in urban soils of Europe: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 854, (2023).

Golia, E. E., Papadimou, S. G., Cavalaris, C. & Tsiropoulos, N. G. Level of contamination assessment of potentially toxic elements in the urban soils of Volos City (Central Greece). Sustainability 13, 2029 (2021).

Rajpolt, B. Fluorine pollution of underground water in the area of the respository of the former Aluminium Mettarurgy Plant in Skawina. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 4, (2010).

Rajpolt, B. & Tomaszewska, B. Fluorine contamination in soil and aquatic environment on the example of Aluminium Smelter in Skawina. Publishing House of the MEERI PAS (2011).

Gajdzik, B. Environmental aspects of the restructuring process in the steel and metallurgical sector in Poland . Poland JEcolHealth 17, (2013).

Central Statistical Office (CSO 2023) Statistical Office n Krakow. Available at: https://krakow.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 10 May 2024). (In Polish).

Bokwa, A. Evolution of studies on local climate of Kraków. Acta Geographica Lodziensia 108, 7–20 (2019).

Szczepaniak, W. Instrumental Methods in Chemical Analysis (in Polish) (PWN, 2005).

Klub POLLAB Information Bulletin 1/52/2009, E. 1. Measurement Uncertainty Related to Sampling. Methodological Guide. Utilizing Information on Measurement Ucertainty for Compliance Assessment (in Polish). (2007).

Journal of Laws; item 1395. Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of September 1, 2016, on the method of assessing soil contamination. (2016).

European Environment Agency (EEA). Soil monitoring in Europe: A review of existing systems and requirements for harmonisation at EU level. Publ. Off. Eur. Union (2023).

Ballabio, C., Hiederer, R., Fernández-Ugalde, O. & et al. EU soil strategy: Harmonisation of criteria and thresholds for contaminated soil. Joint Res. Centre (JRC), Eur. Comm. (2024).

ISO 11465. Soil quality—Determination of dry matter and water content of soil—Gravimetric method. Polish Standard. (1999).

ISO 75/C-04616.01. Water and sewage. Special studies of sludges. Determination of water content, dry matter, organic substances, and mineral substances in sewage sludge. Polish Standard. (1975).

ISO 11466. Soil quality - Extraction of trace elements soluble in aqua regia. Polish Standard. (1995).

Royal Society of Chemistry. version 1.0.1.; access: October 2021; http://www.rsc.org.

El Fadili, H. et al. Bioavailability and health risk of pollutants around a controlled landfill in Morocco: Synergistic effects of landfilling and intensive agriculture. Heliyon 10, e23729 (2024).

Sapota, A. & Skrzypińska-Gawrysiak, M. Barium and its soluble compounds. Documentation. Found. Methods Work Environ. Assess. 1(47), 39–64 (2006).

Wacławek, W. & Gruca-Królikowska, S. Metals in the environment. Part II. Impact of heavy metals on plants (in polish). Chem. Didact. Ecol. Metrol. 11, 41–54 (2006).

Jagodzińska, M. & Rydzek, M. Environmental impact of heavy metals from means of transport. Buses – Tech. Exploitation, Transport Syst 24, 68–70 (2019).

Bojanowski, D. Determination of heavy metal sources in an agricultural catchment (Poland) using the fingerprinting method. Water (Basel) 16, 1209 (2024).

Liu, Y.-R. et al. Soil contamination in nearby natural areas mirrors that in urban greenspaces worldwide. Nat. Commun. 14, 1706 (2023).

Gąsiorek, M., Kowalska, J., Mazurek, R. & Pająk, M. Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal pollution in topsoil of historical urban park on an example of the Planty Park in Krakow (Poland). Chemosphere 179, 148–158 (2017).

Wieczorek, K., Turek, A., Szczesio, M. & Wolf, W. M. Comprehensive evaluation of metal pollution in urban soils of a post-industrial city—a case of Łód´ z, Poland. Molecules 25, (2020).

Plak, A., Telecka, M., Charzyński, P. & Hanaka, A. Evaluation of hazardous element accumulation in urban soils of Cracow, Lublin and Torun (Poland): pollution and ecological risk indices. J Soils Sediments https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-024-03864-0 (2024).

Rahmonov, O., Kowal, A., Rahmonov, M. & Pytel, S. Variability of concentrations of potentially toxic metals in the topsoil of urban forest parks (Southern Poland). Forests 15, (2024).

Golia, E. E., Bethanis, J., Xagoraris, C. & Tziourrou, P. potentially toxic elements in urban and peri-urban soils -A critical meta-analysis of their sources, availability, interactions, and spatial distribution. J. Ecol. Eng. 25, 335–350 (2024).

Savignan, L., Faucher, S., Chéry, P. & Lespes, G. Platinum group elements contamination in soils: Review of the current state. Chemosphere 271, 129517 (2021).

Golia, E. E. The impact of heavy metal contamination on soil quality and plant nutrition. Sustainable management of moderate contaminated agricultural and urban soils, using low cost materials and promoting circular economy. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 33, 101046 (2023).

Azhar, U. et al. Remediation techniques for elimination of heavy metal pollutants from soil: A review. Environ. Res. 214, 113918 (2022).

Gkoltsou, V. S., Papadimou, S. G., Bourliva, A., Skilodimou, H. D. & Golia, E. E. Heavy metal levels in green areas of the urban soil environment of Larissa City (Central Greece): Health and sustainable living risk assessment for adults and children. Sustainability (Switzerland) 17, (2025).

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this work was carried out at the Oil and Gas Institute – National Research Institute in Krakow. The facilities and resources provided by the Institute were essential for the successful completion of the study. The authors acknowledge the financial support of AGH University of Krakow, grant number 16.16.210.476. Research supported by AGH UST within the framework of the “Excellence Initiative—Research University” program.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., M.G., D.U., K.S.; methodology, M.G., D.U., J.P., K.S.; formal analysis, M.G., D.U., J.P.; investigation, D.U., J.P., M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., M.G., D.U., K.S.; visualization, D.U;. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uchmanowicz, D., Pyssa, J., Gajec, M. et al. Assessment of potentially toxic elements in agricultural and urban soils of lesser Poland using ICP-MS and uncertainty estimation. Sci Rep 15, 36795 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20680-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20680-9