Abstract

This paper highlights the significance of mesoscale structures, particularly the core-periphery structure, in financial networks for portfolio optimization. We build portfolios of stocks belonging to the periphery part of the Minimum Spanning Trees and Planar maximally filtered subgraphs of the underlying network of stocks created from Pearson correlations between pairs of stocks and compare its performance with some well-known strategies of Pozzi et. al. hinging around the local indices of centrality in terms of the Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio, information ration and average return. Our findings reveal that these portfolios consistently outperform traditional strategies and further the core-periphery profile obtained is statistically significant across time periods. These empirical findings substantiate the efficacy of using the core-periphery profile of the stock market network for both inter-day and intraday trading and provide valuable insights for investors seeking better returns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Portfolio optimization has been a central theme in a huge body of literature in mathematical finance over the past decades. It involves the selection of an optimal portfolio of stocks that maximizes returns while minimizing risk1,2,3. Portfolio optimization is important to high-frequency traders as well as long-term investors4,5. Markowitz6 introduced the classical mean-variance optimization framework, a foundational contribution to modern portfolio theory. This approach yields optimal asset weights by maximizing the expected return for a given level of risk or minimizing risk for a target return. Building on this foundation, our study integrates network-based insights by constructing portfolios derived from the core periphery structure of financial networks. We then optimize the asset weights by maximizing the Sharpe ratio, subject to realistic constraints: all asset weights are non-negative, lie between 0 and 1, and sum to one7. These weights represent the proportion allocated to each stock.

In recent years, network science has provided tools to model complex interdependencies in financial markets. Researchers have used filtered networks such as the Minimum Spanning Tree8 (MST) and Planar Maximally Filtered Graph9 (PMFG) to extract meaningful topologies by representing stocks as vertices and correlations between them as edges. The topology of these financially filtered networks effectively extracts hierarchical and clustering properties and reduces data complexity while preserving the fundamental characteristics of the dataset. In recent years, centrality and peripherality measures have emerged as practical tools for assessing the importance of assets in a network and constructing optimized portfolios4,10,11. In analyzing high-frequency stock market networks, previous work utilizing data from the National Stock Exchange India revealed pronounced nonlinear relationships among stocks and optimized portfolios using the network approach based on the mutual information method5. Applying random matrix theory in financial networks using cross-correlation and global motion matrices highlights peripherality for asset selection and superior portfolio optimization.12,13. The use of centrality and peripherality measures has emerged as effective tools to assess the importance of assets in a network and to construct optimized portfolios4,10. Many researchers have focused on analyzing stock networks amid financial crises5,14,15,16. Extensive research is available on applying centrality and peripherality measures to portfolio optimization4,5,11,17. It is worth pointing out that strategies other than centrality and peripherality, such as clustering techniques, have also been explored in the context of portfolio construction18,19,20,21,22. A network-based strategy for the construction of portfolios has gained popularity in the recent past4,17,23,24.

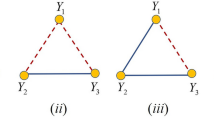

However, most studies rely on local centrality-based heuristics to identify influential stocks, often overlooking mesoscale structures such as core-periphery organization. Despite their widespread use in social25,26, transportation23,26,27,28 and biological28,29 networks, core-periphery models have not been extensively applied in the context of portfolio optimization. The original definition of core and periphery of a network formulated by Borgatti et al.25 is as follows (it captures the intuitive idea that core vertices are densely connected, there are linkages between core and periphery vertices, and there are no linkages between periphery vertices): Let \(G\) be an undirected and unweighted network with \(N\) vertices and \(M\) edges with neither self-loop nor multiple edges. Let \(A = (a_{ij})\) be the adjacency matrix for \(G\) where \(a_{ij} = 1\) if the vertices \(i\) and \(j\) are adjacent and \(a_{ij} = 0\) otherwise. A network \(G\) is classified as a core-periphery network if there exists a set of core vertices \(K \subset N\) and periphery vertices \(P \subset N \setminus K\), such that:

-

i.

\(\forall i, j \in K: a_{ij} = 1\).

-

ii.

\(\forall i, j \in P: a_{ij} = 0\).

-

iii.

\(\forall i \in K, \exists j \in P\) with \(a_{ij} = 1\), and \(\forall j \in P, \exists i \in K\) with \(a_{ij} = 1\).

In Ref.25, Borgatti et al. assign a label \(c_i\) to each vertex \(i\) according to the rule: \(c_i = 1\) if vertex \(i\) belongs to the core set \(K\), and \(c_i = 0\) if vertex \(i\) belongs to the periphery set \(P\). They compute the optimal partition into \(K\) and \(P\) by maximizing the function

where \(c_{ij}\) is set to 1 if either \(i\) or \(j\) belong to \(K\), and set to 0 if both belong to \(P\). Furthermore, Borgatti et al. formulate the idea of assigning a “coreness” value to each vertex by introducing a continuous quantity \(c_i \in [0,1]\) for each vertex \(i\), and computing these by maximizing

Motivated by this approach, Rombach et al.30 propose a robust method capable of identifying multiple cores by defining the quality of a core in terms of a transition function, which is then maximized to obtain the core scores for each vertex. We provide precise methodological details in the Methods section. In this work, we focus solely on undirected graphs, as financial networks constructed using correlation or distance metrics naturally yield symmetric adjacency matrices, representing mutual relationships between pairs of stocks without directional influence. This is a standard approach in market structure studies, where edge directions are not meaningful in the absence of explicit causality or flows. A literature survey shows significant effort has been devoted to analyzing core-periphery structures in financial networks. Notable works include Refs.23,31,32. For instance, Ref.23 studies a combination of ETFs and their constituent stocks, and a core-periphery analysis of a correlation-based network using the Rombach model30 revealed that ETFs appear in the core. However, no particular application or analysis has been reported for the periphery vertices.

In this paper, we have explored the performance of various portfolios constructed based on different core-periphery strategies at different levels of data (daily data and tick-by-tick data of 30 seconds). We have observed that the periphery vertices decided based on the core scores given by the Rombach model30 could not give us any clear advantage from an investment point of view. So, we explored other methods for assigning coreness values and experimented with the method of Rossa et al.28. This is a statistical procedure in which persistence probabilities of sets of vertices are computed by modeling a random walker transitioning from vertex \(i\) to \(j\) as a Markov chain. We provide the requisite details in Methods section. We specifically point out the seminal work of Pozzi et al.4 in which a measure is constructed to detect sparsely connected vertices. This measure called the hybrid measure is based on degree centrality, betweenness centrality, eccentricity, closeness, and eigenvector centrality values. Vertices with high hybrid scores are treated as peripheral, whereas vertices with low values of the hybrid score are treated as central. The underlying network used is the PMFG of the pairwise correlation-based network. The main result of this work is that investing in peripheral stocks identified using the hybrid measure outperforms investing in central ones. The authors construct and compare portfolio performance by assigning stock weights uniformly and using the Markowitz optimization framework. In our work, we propose a novel portfolio construction strategy based on the core-periphery profile of stocks. Our starting point is the PMFG sub-graph extracted from a pairwise correlation-based network with the correlation coefficient as the weight assigned to the edge between two stocks. This is much simpler than Pozzi s strategy s starting point, in which the weights assigned to edges are exponentially weighted Pearson s correlation coefficients. We constructed the stock network using the correlation method and filtered it using PMFG. We use popular core-periphery algorithms to identify the core and peripheral stocks of the network. We construct portfolios comprising stocks identified as peripheral and evaluate their performance against well-known strategies, including the hybrid measure-based. We also compare our proposed strategy with another core-periphery strategy. Empirical results show that peripheral stocks identified through the proposed core-periphery strategy outperform traditional methods. The results presented in this paper are obtained on both daily and high-frequency data (recorded at intervals of 30 seconds), adding to the scarce knowledge in this context.

The objectives of this paper are (i) Highlighting the importance of core-periphery structures within the financial correlation networks for guiding portfolio decisions. (ii) To construct portfolios from the peripheral region of the PMFG-filtered network built from correlation and compare their performance against standard centralities-based strategies using financial metrics such as Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio, information ratio, average return, and risk profiles. (iii) To assess the statistical significance of the core-peripheral structure in financial networks. (iv) Liquidity and practical implementation considerations. (v) Assessing the stability of the core and periphery stocks over time. (vi). Investigating the long-memory characteristics of stock return series using Hurst exponent.

Methods

In this section, we introduced some well-established core periphery detection algorithms, including the methods proposed by Rossa et al.28 and Rombach et al.30, which we employed to identify and analyze core periphery structures in networks. Furthermore, we present the hybrid measure approach introduced by Pozzi et al.4, which we use for comparison with our proposed core periphery-based methods.

Algorithms for detecting core-periphery structure in Networks

Rossa et al.’s intuitive idea of core and periphery is captured by modeling a random walker from vertex \(i\) to vertex \(j\) as a Markov chain28. Here, the vertices of the weighted network constitute the set of states of the Markov chain, and the matrix of transition probabilities (from vertex \(i\) to \(j\)) \([p_{ij}]\) is defined in terms of the weighted adjacency matrix \([a_{ij}]\) as

In this paper, we compute \(a_{ij}\) as in Ref.23

where \(\rho _{ij}\) is the Pearson correlation coefficient between vertices \(i\) and \(j\). The transformation ensures that all resulting weights are non-negative.

The goal is to find the largest subset \(S\) of vertices such that if the random walker is parked at any vertex belonging to \(S\), then at the next instant there is a high probability that it escapes \(S\); that is, there is an extremely slim chance of staying inside \(S\). This would imply that the connectivity among the vertices in \(S\) is possibly non-existent or very weak. So, intuitively \(S\) has periphery vertices.

Mathematically, the probability that a random walker stays inside \(S\) is given by

where \(\pi _i > 0\) is the asymptotic probability of being at vertex \(i\). This expression, however, greatly simplifies in view of the irreducibility of the Markov chain, leading to the condition

For further details, the reader may refer to Ref.33. A simple algebraic manipulation yields

Here, \(C^{w}_{DC}(i) = \sum _h a_{ih}\) stands for the weighted degree of the \(i\)th vertex. This simplifies \(\phi _S\) to the expression below and makes it easy to compute:

Now, the set \(S\) is constructed as follows: We start with any vertex of least weighted degree and call the set containing this vertex as \(S_1\). Without loss of generality, assume that \(S_1 = \{1\}\). Here, \(\phi _1 := \phi _{S_1} = 0\). In the next step, consider the subsets \(S_2^{(j)} := S_1 \cup \{j\}\) for all \(2 \le j \le N\) and compute the minimum of all \(\phi _{S_2^{(j)}}\). Suppose \(\phi _{S_2^{(k)}}\) is the minimum, then define \(S_2 := S_2^{(k)}\) and \(\phi _2 := \phi _{S_2^{(k)}} = \phi _{S_2}\) is the coreness assigned to the vertex \(k\). Note that \(S_2\) is a set of 2 vertices with the least persistence probability and \(\phi _1 \le \phi _2\). Next, we repeat the above process to construct \(S_3\) from \(S_2\) and to compute \(\phi _3\) - the coreness of the third vertex, so that \(\phi _1 \le \phi _2 \le \phi _3\) and continue this process till all vertices are exhausted. Finally, we have the core-periphery profile \(\phi _1 \le \phi _2 \le \cdots \le \phi _N\) of the network.

Figure 1 shows the correlation-based PMFG network of 89 stocks of the index NIFTY 100 for the entire year 2014. Green vertices are the ones which have high values of coreness, and the red vertices have very low values of coreness (that is, they are most peripheral). Had there been an ideal core-periphery structure in this network, then we would have found a set of red vertices in which no two vertices are connected; but that is not the case here, as one can spot two adjacent red vertices in the figure.

A correlation-based PMFG network of 89 stocks of the index NIFTY 100 from the National Stock Exchange, India, from January to December 2014. The top 10 peripheral and core stocks based on the method of Rossa et al.28 are colored with red and green circles, respectively. Also, the size of a vertex is proportional to the degree of the vertex, and the width of the edge is proportional to the correlation coefficients.

The other idea of Rombach et al.30 was to assign a core score (a number lying between 0 and 1) to each vertex through an optimization procedure described below. This method works for weighted and undirected networks and hinges around determining a random shuffling \((c_1, c_2, \ldots , c_N)\) of the coreness values assigned to \(N\) vertices which maximizes the quality function for chosen values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\):

Following30, we choose the initial coreness values to be

The parameters \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) lie between 0 and 1. Let the shuffling of \((c_i^*)\) which maximizes \(Q\) be denoted by \((c_i)\). For the sake of convenience, we denote the maximum value of \(Q(\alpha , \beta )\) also by \(Q(\alpha , \beta )\). We repeat these calculations for numerous pairs \((\alpha , \beta )\) and define the core score (CS) for each vertex \(i\) as

where \(Z\) is the normalization constant chosen so that \(\max _{1 \le j \le N} CS(j) = 1\). Therefore,

In this paper, we work with 10000 pairs \((\alpha , \beta )\) uniformly sampled from the unit square \([0, 1] \times [0, 1]\).

Construction of the hybrid measure

The approach adopted in4 is to calculate the hybrid measure for each vertex of the PMFG subgraph extracted from the full exponential weighted Pearson correlation network. This hybrid measure is defined in terms of Degree centrality, the Betweenness, Eccentricity, the Closeness, and the Eigenvector centrality for the underlying weighted and unweighted PMFG subgraphs:

The hybrid measure of the \(i\)th vertex is defined by

For the vertex \(i\), \(C^{w}_{DC}(i)\) (\(C^{u}_{DC}(i)\)) is the weighted (unweighted) degree centrality. \(C^{w}_{BC}(i)\) (\(C^{u}_{BC}(i)\)) is the weighted (unweighted) betweenness centrality. \(C^{w}_{E}(i)\) (\(C^{u}_{E}(i)\)) is the weighted (unweighted) eccentricity. \(C^{w}_{C}(i)\) (\(C^{u}_{C}(i)\)) is the weighted (unweighted) closeness. \(C^{w}_{EC}(i)\) (\(C^{u}_{EC}(i)\)) is the weighted (unweighted) eigenvector centrality. In Ref.4, for the computation of weighted degree and eigenvector centrality of vertices, the edge between vertices \(i\) and \(j\) are assigned the weight \(1 + \rho _{ij}^w\); whereas, for the computation of weighted betweenness, eccentricity, and closeness centralities, the edge weights chosen are \(\sqrt{2(1 - \rho _{ij}^w)}\). The value of \(P(i)\) is small for the central vertices and large for its peripheral vertices in the network. Pozzi et al.4 made the portfolios using the hybrid measure, showing that their portfolio performance is better than the individual centralities measures or other combinations.

Markowitz model & financial ratios

The Markowitz mean-variance portfolio theory, proposed by Markowitz6, is a fundamental framework in modern finance to optimize portfolio allocations. In this study, we use the Markowitz model that maximizes the Sharpe ratio, which measures the risk-adjusted return of a portfolio7. The objective is to find the optimal weights of assets that maximize the Sharpe ratio, subject to certain constraints. Let \(w\) be the weight vector that represents the allocation of assets in the portfolio. The optimal portfolio allocation can be obtained by solving the following optimization problem:

where \(R_{P}\) is the expected return of the portfolio and \(\sigma _{P}\) is the standard deviation of the portfolio returns. The expected return of the portfolio \(R_{P}\) and the standard deviation \(\sigma _{P}\) can be calculated as follows:

where \(R_{i}\) is the expected return of asset \(i\), \(\sigma _{i}\) is the standard deviation of the returns of asset \(i\), and \(C_{ij}\) is the cross-correlation between assets \(i\) and \(j\).

This study also uses a risk parity34 approach as an alternative portflio optimization method that aims to balance the contribution of each asset to the overall portfolio risk. This method is based on inverse volatility weighting rather than focusing solely on return maximization. Let \(\varvec{\sigma }\) denote the volatility of the asset’s portfolio. The portfolio weights \(\textbf{w}\) are calculated as:

where \(\varvec{\sigma }^{-1} = \left( \frac{1}{\sigma _1}, \frac{1}{\sigma _2}, \dots , \frac{1}{\sigma _n} \right) ^\top\) denotes the element-wise inverse of the volatility vector \(\varvec{\sigma } = \left( \sigma _1, \sigma _2, \dots , \sigma _n \right) ^\top\), and \(\textbf{1} = (1, 1, \dots , 1)^\top\). This weighting scheme gives higher allocation to assets with lower volatility, approximating equal risk contributions across the portfolio. This method provides a computationally efficient proxy for risk balancing.

Let \(\hat{S}_{t,m}\) represent the price of the portfolio of the \(m\) stocks at tick \(t\). Let \(w_i\) be the weight of the \(i\)th stock in the portfolio. Then, for each portfolio at tick \(t\), the return of the portfolio over the next \(T\) ticks is given by:

with

where \(\hat{S}_{t,i}\) and \(\hat{S}_{t+T,i}\) are the prices of the \(i\)th stock at ticks \(t\) and \(t + T\), respectively. In this context, \(T\) is the holding period. We compute the average return \(\bar{R}_{t+T,m}\) as well as the standard deviation \(s_{T,m}\) over \(t\) in the full-time span. We then choose the Sharpe ratio \(S_{T,m}\) as a proxy for the performance of the portfolio, which is defined as

From an investment point of view, it is desirable to invest in portfolio having large Sharpe ratio. Comparing \(S_{T,m}\) across different strategies tells you which is more robust and efficient, providing an empirical basis for performance comparison.

While the Sharpe ratio is the most widely used metric in the literature4,5,12 for risk-adjusted portfolio performance, it treats all volatility symmetrically. Usually, it assumes normally distributed returns that can be limiting in practice. For addressing these limitations, we consider the Sortino ratio35 (which focuses exclusively on downside risk) and the information ratio36 (which evaluates excess returns relative to a benchmark), providing a more nuanced assessment of portfolio performance.

The Sortino ratio measures the risk-adjusted return of an investment strategy and addresses a key limitation of the Sharpe ratio by focusing solely on downside risk. It is defined as:

where \(R_p\) is the portfolio return, \(R_f\) is the risk-free rate (or minimum acceptable return), and \(\sigma _d\) is the downside deviation, calculated as the standard deviation of returns falling below \(R_f\). Unlike the Sharpe Ratio, which penalizes upward and downward volatility, the Sortino ratio isolates harmful downside fluctuations, making it a more investor-aligned and practical metric for real-world portfolio evaluation.

The information Ratio (IR) quantifies the risk-adjusted portfolio performance by measuring the excess return of an investment and normalizes it by the volatility of that excess return. It is defined as:

where \(R_p\) denotes the return of the portfolio, \(R_b\) represents the return of a benchmark (e.g. market index) and \(\sigma _{(R_p-R_b)}\) is the standard deviation of the excess return. The information ratio quantifies performance relative to the benchmark, making it particularly suitable for evaluating active investment strategies.

Data description

Financial network analysis has been extensively applied to understand structural organization and dynamics of financial markets. Daily stock return data has been widely used due to its availability and ease of handling. However, high-frequency data collected at intervals of seconds or minutes provides deeper insight into short-term market dynamics, liquidity fluctuations, and intra-day structural changes, albeit at the cost of increased data processing and analysis complexity.

Several studies have utilized daily data to construct financial networks. For instance, Guo et al.16 studied the Chinese stock market based on daily returns. Similarly, Pozzi et al.4,37,38 focused on daily stock data from the American Stock Exchange to explore network filtering techniques and their implications on portfolio optimization. On the other hand, more recent works have begun to examine high-frequency data in financial networks. Barbi et al39 investigated the Brazilian equity market using nonlinear dependencies derived from stock returns with a 15-minute tick size. Sharma et al.5 studied the Indian stock market using 30-second interval data, capturing the rapidly evolving market structure and its implications on systemic risk. In the same year, Khoojine et al15 analyzed the Chinese stock market turbulence during 2015 2016 by examining topological features of networks based on high-frequency level. Therefore, we worked with both high-frequency and daily data sets. Below, we describe the details of the data sets that are used for our study.

Daily time series stock market data

We collect daily price data for the constituent stocks of the NIFTY 500 index from the National Stock Exchange (NSE), India, and the S&P 500 index from the U.S. stock market over 8 years, spanning from January 2014 to December 2021. After excluding stocks with insufficient or missing data, our final dataset comprises 351 stocks from the NIFTY 500 and 464 stocks from the S&P 500. The log return of stock \(k\) on day \(t+1\) is calculated as:

where \(S_{t,k}\) denotes the price of stock \(k\) on day \(t\).

High-frequency stock market data

We collect tick by tick high-frequency data of the constituent stocks of the NIFTY 100 index from the National Stock Exchange, India during the period January 2014 to December 2014. The data was filtered to obtain all stocks listed on the NIFTY 100 during that year. Eleven stocks were omitted from the analysis due to insufficient and missing data. We finally selected 89 stocks out of 100 stocks during the entire year 2014. The exchange opens at 9 am and is open till 4 pm. In the first half hour, trades tend to pick up pace, while the last half hour shows some ambiguity or incompleteness in the data. Keeping this in mind, we have used data from 9:30 am to 3:30 pm in our analysis. Furthermore, we divide this period into 30 seconds time intervals and call each such interval a tick. Thus, the total number of ticks considered for each working day will be 720. For the \(k\)th stock, we first calculate the volume-weighted average price, \(\hat{S}_{t,k}\) for the tick \(t\) by

Here \(v_{i,k,t}\) is the volume of the \(k\)th stock traded at an instant \(i\) and \(S_{i,k,t}\) is the stock price at the instant \(i\) in the 30-second window at time \(t\). The log return of each stock \(k\) at tick \(t\) is then calculated using Equation 16.

Furthermore, we considered 2014 for our analysis, as it was the year when general elections were held in India and a change in government was seen. Tables 1 and 2 provide detailed information on the sector-wise distribution of the 89 and 351 stocks in the NIFTY 100 and NIFTY 500 indices, respectively, considered in our analysis.

Results

In the following subsections, we conducted a comprehensive analysis structured around the following key components:

-

Portfolio selection at daily and high-frequency levels

-

Cross-validation of portfolio performance

-

Statistical significance of core-periphery profile of stocks

-

Liquidity and practical implementation considerations

-

Dynamic occurrence of core and periphery stocks over time

-

Estimation of the Hurst exponent using the rescaled range (R/S) method

We elaborate on each of the above points below in detail.

Portfolio selection at daily and high-frequency levels

This section discusses the comparative analysis of portfolio construction, where we examine the performance of our proposed strategy in contrast to traditional methods, including Pozzi’s approach4. We evaluate the performance of portfolios comprised of sizes \(m = 5, 10, 20\) and \(30\) stocks by assigning portfolio weights using both the uniform method and the Markowitz method:

Type-1 (Portfolio of periphery stocks from the core-periphery strategy-1): We apply the Rossa algorithm28 to each PMFG network based on the correlation method. This gives a core-periphery profile: \(\phi _1 \le \phi _2 \le \ldots \le \phi _m \le \ldots \le \phi _N\), Where \(N\) is the number of stocks. We list the pure periphery stocks for which \(\alpha _k = 0\) in decreasing order of the Sharpe ratio. Next, we construct a portfolio comprising the \(m\) most periphery stocks corresponding to \(\phi _1, \phi _2, \ldots , \phi _m\).

Type-2 (Portfolio of periphery stocks from the core-periphery strategy-2): We apply the Rombach algorithm30 to each PMFG network based on the correlation method. This gives the coreness of each vertex and then arranges them in ascending order of coreness: \(x_1 \le x_2 \le \ldots \le x_m \le \ldots \le x_N\). Subsequently, we list the pure periphery stocks for which \(x_k = 0\) in decreasing order of the Sharpe ratio. Next, we construct a portfolio comprising the \(m\) most periphery stocks corresponding to \(x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_m\). This portfolio is constructed in a similar fashion as in Refs.4,5,12,17.

Type-3 (Portfolio of peripheral stocks from the Hybrid measure of Pozzi et al.4): We compute the hybrid measure for each vertex of the PMFG networks based on the exponentially weighted correlation method38, as elaborated upon in the preliminaries section. We arrange them in descending order: \(x_1 \ge x_2 \ge \ldots \ge x_N\). According to Ref.4, peripheral vertices are the ones with higher values of the hybrid measure. Thus, the stocks corresponding to \(x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_m\) are the \(m\) most peripheral stocks.

Type-4 (Portfolio of core stocks from the core-periphery strategy-1): We apply the Rossa algorithm to each PMFG network based on the correlation method and arrange the obtained core-periphery profile in descending order. We then pick the stocks corresponding to the first \(m\) scores. Thus, we consider portfolios of the \(m\) most core stocks. The authors in Refs.4,10,12,17 have also considered portfolios constructed out of core stocks.

Type-5 (Portfolio of core stocks from the core-periphery strategy-2): We apply the Rombach algorithm to each PMFG network based on the correlation method and arrange the obtained coreness in descending order. Next, we construct a portfolio comprising \(m\) stocks corresponding to the first \(m\) scores. Thus, we consider portfolios of the \(m\) most core stocks.

Type-6 (Market portfolio): We constructed a ’market portfolio’ comprising all \(N\) listed stocks. This type of portfolio has been used as a benchmark in many works such as Refs.4,5.

Investing in a large stock portfolio might be difficult for intraday or interday traders because of the high volume of transactions and the requirement for quick decision-making. Therefore, our objective was to develop an investment strategy that enables investors to achieve competitive returns with a small portfolio of stocks compared to a fully diversified portfolio containing a large number of stocks. Thus, we evaluate the performance of portfolios constructed with varying sizes, specifically \(m=5, 10, 20,\) and \(30\), comprising the most periphery and core stocks using our proposed core-periphery-based strategies. In the subsequent section, we will elucidate the portfolio performance of our proposed strategies utilizing both daily and high-frequency stock market datasets.

A comparative study on daily time series stock market data

We utilized daily data from 351 stocks selected from the NIFTY 500 index of the National Stock Exchange (NSE) of India, spanning from January 2014 to December 2021, covering a total of 1970 market days. Notably, during this period, the market trend in 2020 witnessed a significant decline Fig. 2 due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, resulting in prolonged volatility. Our analysis involves using moving windows of 125 days (equivalent to 6 months). For each day \(t\) within this window, we construct the PMFG-filtered network based on the full cross-correlation matrix derived from the preceding 125 days. Subsequently, we assess the stability of the portfolio over the subsequent 125 days, encompassing holding periods ranging from 1 to 125 market days.

We first construct portfolios using the uniform method and then compare the Sharpe ratios and average returns of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in the daily time series data (NIFTY 500). Figures 3 and 4 show that Type-1 significantly outperforms Types-2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in terms of both the Sharpe ratio and average returns. Notably, as the holding period increases, Type-1 consistently demonstrates increasing advantages over Types-2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Our main results are presented by the comparison between Type-1 with Type-3 and Type-6 (investing in all stocks i.e., market performance). Furthermore, Fig. 5 indicates that the risk (standard deviation) associated with Type-1 is lower than that of Types-4 and 5, while as portfolio size increases, the risk profiles of Type-1 become similar to Types-3 and 6. We also construct portfolios using the Markowitz method and then compare the Sharpe ratios and average returns of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Figures 6 and 8 show that Type-1 significantly outperforms Types-2, 3, 4, and 5 in terms of both the Sharpe ratio and average return. Significantly, as the holding period extends, Type-1 consistently demonstrates increasing advantages over Types-1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Additionally, from Figure 8, as the portfolio size expands, Type-1 approaches Type-6, representing the market portfolio with Markowitz weights, in terms of the Sharpe ratio. However, analysis from Fig. 4 reveals that the average return of Type-1 is comparable to that of Type-6. Furthermore, Fig. 7 shows that Type-1 carries a lower risk than Types-2, 3, 4, and 5 in terms of standard deviation. In addition, the risk profiles for Type-1 and Type-6 become more comparable as the size of the portfolio increases. The distribution of Markowitz weights among all stocks may be the cause of this Type-6 risk discrepancy (Fig. 8).

Table 7 presents a comprehensive comparison of portfolio performance across three types strategies, Type-1, Type-2, and Type-3 under varying weighting schemes, equal weight (\(\textbf{w}^{\textrm{EW}}\)), Markowitz (\(\textbf{w}^{\textrm{MW}}\)), and risk parity (\(\textbf{w}^{\textrm{RP}}\)). The analysis includes multiple investment horizons (20, 40, 80, 100, and 120 days) and considers a portfolio size \(m = 30\). The empirical results reveal that Type-1 strategies consistently outperform Type-2 and Type-3 across almost all evaluation metrics, including Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio, Information ratio, and mean return, regardless of the holding period or weighting scheme. This superior performance is particularly evident under the equal weight and risk parity schemes, where Type-1 portfolios show the most significant advantage in risk-adjusted returns. For example, under the equal weighting scheme, the Sharpe ratio for Type-1 increases from 0.32 (20-day horizon) to 0.78 (120-day horizon), while the Sortino ratio improves from 0.33 to 1.97, the Information ratio from 0.12 to 1.74, and the mean return from 0.021 to 0.11. Similar upward trends are observed under other weighting methods, underscoring the robustness of Type-1 across traditional and downside-risk-based performance measures. While Type-3 occasionally performs competitively, particularly under the Markowitz scheme at shorter horizons, the differences with Type-1 are generally marginal. Type-2 underperforms across all configurations, affirming the comparative weakness of its underlying stock selection procedure.

It is worth noting a minor deviation in performance at portfolio size \(m = 5\), where fluctuations are observed across strategies. This deviation is likely due to the relatively small number of assets compared to the total number of 351 stocks (see Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the results affirm the statistical and economic significance of the Type-1 strategy, highlighting its reliability across different market conditions, weighting schemes, and evaluation criteria. These findings also remain consistent for other portfolio sizes (see Supplementary Tables 1–3).

To further evaluate the robustness of our method, we compare its performance with an alternative filtering approach, the Minimum Spanning Tree (MST). The comparative results under the uniformly weighted scheme, in terms of Sharpe ratio, average return, and portfolio risk, are presented in Supplementary Figures 1–3. As observed, portfolios constructed using our proposed method (Type-1) consistently outperform the alternative core-periphery strategy (Type-2), the hybrid centrality-based approach (Type-3), and the core stock portfolios (Types-4 and 5). Regardless of the filtering technique, our key finding remains robust: portfolios composed of peripheral stocks identified through our proposed method achieve better risk-adjusted performance than the traditional method. We also perform these analyses using weights from the Markowitz portfolio optimization framework, yielding comparable results. Therefore, our results are consistent with the different filtering approaches and prove our method’s robustness.

To assess the generalizability of our findings, we extend our analysis to a developed financial market, specifically, the US stock exchange, represented by the S&P 500 index over the same time period as the Indian market: January 2014 to December 2021. The results for the uniform weighting scheme indicate that our proposed strategy (Type-1), based on the core-periphery structure identified via PMFG, consistently outperforms both the alternative core-periphery method (Type-2) and the hybrid approach proposed by Pozzi et al. (Type-3) in terms of risk-adjusted returns. We obtain similar results using the Markowitz portfolio optimization framework. An important observation arises when comparing core and peripheral stock portfolios in this developed market setting. In contrast to our results on the Indian market, portfolios composed of core stocks (Types-4 and 5) initially outperform those made from peripheral stocks, particularly for portfolio sizes of 5 and 10. However, as the portfolio size increases to 20 and 30, the performance gap narrows and becomes comparable. Despite this, in terms of average returns, the peripheral stock portfolios constructed using our proposed method continue outperforming their core stock counterparts. This may be attributed to the lower volatility and relatively stable behavior of core stocks in developed markets like the United States, which typically experience fewer fluctuations than emerging markets like India. This phenomenon is also reflected in the lower standard deviations observed for core stock portfolios, as shown in Supplementary Figures 4–6.

A comparative study on high-frequency stock market data

We perform our analysis using high frequency tick-by-tick data of 30 seconds obtained from the NSE (India), covering the period January 2014 to December 2014, comprising a total of 164,640 ticks. We specifically focused on the year 2014 due to the significant political event of the general elections in India, which resulted in a change of government from the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) after a decade. The elections, promotional rallies held in March, polling in April, and result declarations in May collectively contributed to heightened market volatility during this period, which persisted post-election (Fig. 2). Our analysis involves utilizing moving windows of 240 ticks (equivalent to 2 hours) for the high-frequency data. At each instant t, we construct the PMFG filtered network using 75% overlapping windows of size 240 ticks. Due to the extensive size of the dataset, we employ overlapping windows to efficiently construct PMFG networks. Subsequently, we assess the stability of the portfolio over the next 2-hour window, considering holding periods ranging from 1 to 240 ticks. Initially, portfolios are constructed employing the uniform method, followed by a comprehensive comparison of the Sharpe ratios and average returns across various types (Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) within the high-frequency time series data (NIFTY100). Figures 9 and 10 illustrate that Type-1 exhibits significant outperformance compared to Types-2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in terms of both the Sharpe ratio and average returns. Importantly, as the holding period extends, Type-1 consistently demonstrates escalating advantages over Types-2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Our main results are presented by the comparison between Type-1 with Types-3 and 6 (market portfolio). Moreover, Fig. 11 illustrates that the risk, as indicated by standard deviation, associated with Type-1 is lower compared to that of Types-4 and 5. However, as the portfolio size increases, the risk profiles of Type-1 become increasingly similar to that of Type-6. We also constructed portfolios using the Markowitz method, followed by a comparative analysis of the Sharpe ratios and average returns across Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Figures 14 and 10 show that Type-1 significantly outperforms Types-2, 3, 4, and 5 in terms of both the Sharpe ratio and average return. Significantly, as the holding period lengthens, Type-1 consistently exhibits increasing advantages over Types-1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Additionally, according to Fig. 14, as the portfolio size expands, Type-1 converges toward Type-6, representing the market portfolio with Markowitz weights, in terms of the Sharpe ratio. However, contrasting insights from Fig. 12 reveal that the average return of Type-1 outperforms that of Type-6. Moreover, Fig. 13 highlights that the risk, as indicated by standard deviation, associated with Type-1 is lower than that of Types-2, 3, 4, and 5. Notably, Type-6 appears less risky, potentially attributed to the allocation of Markowitz weights across all stocks. It’s worth emphasizing that the Markowitz theory serves as a classical mathematical framework aimed at maximizing the Sharpe ratio in portfolio construction (Fig. 14).

Each subplot compares the Sharpe ratio of portfolios of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of sizes 5, 10, 20, and 30 stocks, respectively; for the following holding periods, including \(30\) s, \(1\) min, \(1.5\) min, and so on, up to \(120\) minutes (total \(240\) ticks); with weights assigned through the uniform method.

Each subplot compares the average return of portfolios of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of sizes 5, 10, 20, and 30 stocks, respectively; for the following holding periods, including \(30\) s, \(1\) min, \(1.5\) min, and so on, up to \(120\) minutes (total \(240\) ticks); with weights assigned through the uniform method.

Each subplot compares the standard deviation of portfolios of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of sizes 5, 10, 20, and 30 stocks, respectively; for the following holding periods, including \(30\) s, \(1\) min, \(1.5\) min, and so on, up to \(120\) minutes (total \(240\) ticks); with weights assigned through the uniform method.

Each subplot compares the average return of portfolios of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of sizes 5, 10, 20, and 30 stocks, respectively; for the following holding periods, including \(30\) s, \(1\) min, \(1.5\) min, and so on, up to \(120\) minutes (total \(240\) ticks); with weights assigned through the Markowitz method.

Each subplot compares the standard deviation of portfolios of Types-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of sizes 5, 10, 20, and 30 stocks, respectively; for the following holding periods, including \(30\) s, \(1\) min, \(1.5\) min, and so on, up to \(120\) minutes (total \(240\) ticks); with weights assigned through the Markowitz method.

Finally, our study shows that portfolios with Markowitz weights exhibit lower Sharpe ratios than portfolios with equal weights, which aligns with the classical framework of the Markowitz method. While the Markowitz method is theoretically applicable to a large number of stocks, practical implementation can be challenging and costly, making our process more attractive for financial applications. Our results remain consistent across intraday and intraday investor types, demonstrating the robustness of our approach. Overall, our findings underscore the benefits of mesoscale structures in portfolio construction and highlight the importance of peripheral stocks in achieving superior risk-adjusted returns.

Cross validating our observations

To cross-validate and check the effectiveness of our method, we randomly picked 500 windows (out of 1846) from the daily time series data set (NIFTY 500). Then, we picked stocks based on Types 1, 2, and 3 strategies. Subsequently, we compared the rate of returns of the portfolios for different holding periods (for example, 50, 60, and so on, up to 125 days). We compare the Sharpe ratios, average rate of returns, and standard deviations for different strategies (Types 1, 2, and 3). The process was repeated 1000 times and obtained average return, standard deviation, and Sharpe Ratio for each 1000 iteration corresponding to Types 1, 2, and 3. We carried out hypothesis testing to support our claim that the portfolio comprising Type-1 outperforms the others (Types-2 and 3). We calculated \(\hat{p}\), the proportion of times the Sharpe Ratio from our proposed strategy was more than the Sharpe Ratio of the other strategies, and carried out hypothesis testing for the proportion test as follows:

-

Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): \(p_0 = 0.7\).

-

Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): \(p_0 > 0.7\).

Next, we calculated the p-value on the basis of the following test statistic:

For small p-value, we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis.

Similar tests were carried out to check the proportion of times the average return from the Type-1 strategy was more than Types-2 and 3. The p-values for Sharpe ratio comparisons between Types-1 and 2, as well as Types-1 and 3, for various holding periods, are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. One can claim that at least 70% of the randomly chosen windows in our proposed strategy (Type-1) performed better than the rest of the strategies (Types-2 and 3). The p-values for the comparisons of average returns between Types-1 and 2, as well as Types-1 and 3, across various holding periods, are provided in the Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

Statistical significance of core-periphery profile of stocks

To evaluate the statistical significance of the core-periphery profile observed in each network constructed through the rolling-window process. We compute the cp-centralization \(C\) from the empirical networks built using the Planar Maximally Filtered Graph (PMFG) filtering technique for each time window. These networks are derived from the daily return data for the NIFTY 500 and S&P 500 and high-frequency tick data for NIFTY 100. In Ref.28, a measure of the strength of the core-periphery structure called the core-periphery centralization (cp-centralization) is defined and denoted by

A high value of \(C\) indicates that the obtained core-periphery profile \((\phi _1, \ldots , \phi _n)\) is significant. Figure 15 displays the distribution of the cp-centralization values obtained for NIFTY 100, NIFTY 500, and S&P 500, across all network windows.

A statistical procedure to judge the significance of the observed value of \(C\) is based on the computation of the \(p\)-value calculated as follows: For each network, we generate 100 randomized counterparts using the configuration model, which preserves the degree distribution of the original network. We calculate the cp-centralization for each randomized network and call it \(C^{i}_{\text {rand}}\) for \(i = 1, 2, \ldots , 100\). Next, we choose between the following hypotheses based on the \(p\)-values calculated as

Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): The profile \((\phi _1, \ldots , \phi _n)\) is not significant.

Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): The profile \((\phi _1, \ldots , \phi _n)\) is significant and not random.

For a small \(p\)-value, we reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) and accept the alternative hypothesis. The p-value distributions for the NIFTY 100, NIFTY 500, and S&P 500 networks, shown in Fig. 16, are concentrated entirely below the significance threshold of 0.05. This result strongly indicates that the observed core-periphery profiles in the network are not due to random, but reflect a statistically significant structure in the underlying financial networks.

Liquidity and practical implementation considerations

In this study, We have taken the NIFTY 500 data sample period from 1st January 2014 to 31st December 2021, which is divided into consecutive, non-overlapping 6-month estimation and evaluation windows. We conducted a comprehensive window-wise analysis of liquidity and transaction cost proxies to assess the practical feasibility of implementing the proposed core and peripheral stock portfolio strategies. Specifically, for each of the 16 estimation windows spanning the 8-year dataset, we calculated the average daily turnover and the Amihud illiquidity40 measure for both core and peripheral portfolios during their 6-month evaluation windows.

Let \(G_t\) denote the set of \(K\) stocks (core or periphery) identified from estimation window \(W_t\) and \(D_t\) denote the set of trading days in the evaluation window \(F_t\), with \(|D_t| = n_t\) days. The turnover for the portfolio \(G_t\) on day \(d\) is defined as:

where \(V_{i,d}\) is the traded volume and \(P_{i,d}\) is the adjusted closing price of stock \(i\) on day \(d\).

The average daily turnover of the portfolio is calculated as:

The Amihud illiquidity measure, proposed by Yakov Amihud (2002), quantifies the price impact per unit of trading volume, serving as a proxy for illiquidity. The Amihud illiquidity measure for stock \(i\) on day \(d\) is defined as:

where \(R_{i,d}\) denotes the daily return and \(V_{i,d}\) denotes the daily volume of stock \(i\) on day \(d\).

To obtain a group-level illiquidity measure for a portfolio \(G_t\), we average across all stocks:

We examine the top 20 core and top 20 periphery stocks for each window using the approach described in Ref.28. Table 8 compares the core and periphery portfolios based on average turnover and Amihud illiquidity measures. The results consistently show that core portfolios exhibit higher average turnover and lower Amihud illiquidity ratios than peripheral portfolios. This indicates that core stocks are generally more liquid, with higher trading volumes and lower price impact per unit volume, implying lower transaction costs. In contrast, peripheral portfolios exhibit higher Amihud illiquidity measures while demonstrating lower turnover, suggesting poorer liquidity and potentially higher transaction costs due to wider bid-ask spreads and greater price impact upon trading.

These findings highlight an important trade-off in strategy implementation. While peripheral portfolios achieved higher Sharpe ratios and average returns with lower standard deviations compared to core portfolios, the higher illiquidity of peripheral stocks may pose practical challenges in terms of execution cost and market impact. Investors and practitioners must, therefore, carefully balance the potential benefits of selecting peripheral stocks based on network structural signals against the real-world costs associated with trading in less liquid assets.

Dynamic occurrence of core and periphery stocks over time

We investigate the dynamic occurrence patterns of the core and periphery stocks by thoroughly examining all 351 stocks that are part of the Nifty 500 index. In particular, we used the Rossa et al.28 approach described in the Methods section to examine the top 20 core and top 20 periphery stocks over the 1846 periods. A detailed illustration of stock activity throughout different periods is shown in the accompanying Fig. 17, showing observable distinctions between core and periphery stocks. In Fig. 17, each horizontal line represents the ongoing selection of a specific stock over the corresponding period. A notable observation is that the occurrence of core stocks remained relatively stable during the period under consideration. In contrast, peripheral stocks were observed to exhibit very different behavior. This stability suggests that core stocks are in a consistently central position over time, while peripheral stocks exhibit greater variability. A striking observation is the relatively stable occurrence of core stocks throughout the period. In contrast, the periphery stocks are seen to exhibit a very different behavior. This stability suggests that core stocks are consistently in central positions over time, whereas periphery stocks display more significant variability.

The plot shows occurrences of the top 20 core and periphery stocks across all 1846 windows of the Nifty 500 index: (a) Core Stocks: Dots represent stock selection within the top 20, with horizontal lines indicating continuous selection. (b) Periphery Stocks: Like core stocks, dots denote stock selection within the top 20, with horizontal lines representing continuous selection.

We have conducted a comprehensive analysis to ascertain the occurrence distribution, which denotes the number of days stock is allocated to the core or periphery group. Through this analysis, we computed the distribution of occurrence times for individual stocks within the portfolio. The results of this analysis are presented in Fig. 18. The distribution of occurrence times for core stocks reveals a notable peak at the shortest occurrence times, with a pronounced tail extending towards longer durations. Notably, the distribution of core stocks demonstrates characteristics akin to a power law distribution, as evidenced in Fig. 18. For example, a clear pattern emerges where 15 stocks have consistently remained part of the core for a period of more than 500 days. In contrast, the distribution pattern for periphery stocks follows an exponential decay trend. This disparity in distribution behaviors between core and periphery stocks underscores the nuanced dynamics within the portfolio.

We record the frequency of all 351 stocks of Nifty 500 occurring in the top 20 core and the top 20 peripheral stocks across all 1846 windows. We observe that core stocks are predominantly concentrated in financial services. Additionally, Metals & Mining, Chemicals, and construction materials also have stocks with high coreness values. Specifically, the most occurring core stocks across 1846 windows were L&T Finance Holdings Ltd. (Financial Services) (70.10%), Bank of India (Financial Services) (56.07%), Steel Authority of India Ltd. (Metals & Mining) (52.11%), Canara Bank (Financial Services) (48.86%). In contrast, the peripheral companies span various sectors. Specifically, the largest occurring periphery stocks across all 1846 windows were Abbott India Ltd. (Healthcare) (20.21%), Tanla Platforms Ltd. (Information Technology) (15.76%), Relaxo Footwears Ltd. (Consumer Durables) (15.28%), RattanIndia Enterprises Ltd. (Services) (15.01%), APL Apollo Tubes Ltd. (Capital Goods) (14.57%), Alkyl Amines Chemicals Ltd. (Chemicals) (14.41%). Therefore, the core stocks are stable in various time windows, whereas periphery stocks have larger variations.

In terms of the industrial sectors, the frequently occurring core stocks across 1846 windows belong to Financial Services (28.43%), Metals & Mining (11.53%), Chemicals (7.77%), Construction Materials (7.10%), Automobile and Auto Components (6.45%), Capital Goods (5.74%). The largest occurring periphery populated sectors are Healthcare (12.30%), Capital Goods (11.16%), Chemicals (10.13%), Financial Services (9.76%), Consumer Durables (9.04%), Fast Moving Consumer Goods (7.64%). Figure 19 summarizes the proportion of allocation of core and peripheral stocks occurrences.

Estimation of the Hurst exponent using the rescaled range (R/S) method

To investigate the presence of long-range dependence (LRD), which means that past events influence future values over long periods in financial time series, we compute the Hurst exponent41 (H) for each stock’s return series. The Hurst exponent provides insights into the persistence, randomness, or mean-reverting behavior of a time series. It is defined within the interval [0, 1], with the following interpretations:

-

\(H < 0.5\): The series exhibits anti-persistent (mean-reverting) behavior.

-

\(H = 0.5\): The series follows a random walk (no memory).

-

\(H > 0.5\): The series exhibits persistent (trend-following) behavior.

We estimate H using the classical rescaled Range (R/S) method, originally introduced by Hurst41 in 1951. The procedure is described as follows:

-

1.

Let \(X = \{x_1, x_2, \dots , x_n\}\) be the log-return time series of length n.

-

2.

For a given subseries size k, divide the time series into \(\lfloor n/k \rfloor\) non-overlapping blocks of size k.

-

3.

For each block, compute the mean: \(\bar{X}_k = \frac{1}{k} \sum _{i=1}^{k} x_i.\)

-

4.

Compute the cumulative deviation from the mean: \(Y_t = \sum _{i=1}^{t} (x_i - \bar{X}_k), \quad \text {for } t = 1, \dots , k.\)

-

5.

Compute the range R(k) of the cumulative deviation: \(R(k) = \max \limits _{1 \le t \le k} Y_t - \min \limits _{1 \le t \le k} Y_t\)

-

6.

Compute the standard deviation S(k) of the block: \(S(k) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{k} \sum _{i=1}^{k} (x_i - \bar{X}_k)^2}.\)

-

7.

Calculate the rescaled range: \(\frac{R(k)}{S(k)}.\)

-

8.

Plot \(\log (R/S(k))\) against \(\log (k)\) and fit a linear regression. The slope of the best-fit line corresponds to the estimated Hurst exponent H: \(\log \left( \frac{R(k)}{S(k)}\right) = H \log (k) + C.\)

We compute the Hurst exponent for each of the 351 NIFTY500 index stocks to investigate the long-memory characteristics of stock return series. We choose \(k=10\) (small enough to allow many segments) to \(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor\) (large enough to capture meaningful fluctuations) with the step size 50 to reduce computation. This results show a significant majority of the stocks exhibit persistent behavior, characterized by a Hurst exponent greater than 0.5. Specifically, 324 stocks out of 351 (92.31%) were found to be persistent. This strong prevalence of long-memory effects supports the presence of fractal structures and temporal dependencies in financial time series. Figure 20 shows the distribution of Hurst exponents across all stocks, clearly indicating a skew towards persistent dynamics.

The high proportion of persistent behavior (\(H > 0.5\)) observed in our dataset suggests the presence of long-range dependencies in the stock return series. Such behavior is characteristic of self-similar processes, where statistical patterns repeat across time scales. In self-similar time series, the Hurst exponent governs the degree of persistence and is directly linked to the fractal dimension via the relation \(D = 2 - H\), where \(1< D < 2\). A higher Hurst exponent corresponds to a smoother and less rough time series, implying a lower fractal dimension42. This mathematical relationship indicates that persistent time series (with \(H > 0.5\)) are characterized by lower geometric complexity and exhibit long-range dependence. Our findings therefore support the idea that market dynamics are not entirely random but exhibit structured complexity across scales.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate how extracting dependency structures among financial equities, using network-theoretic techniques, can construct well-diversified portfolios that systematically reduce investment risk. Using PMFG constructed from correlation matrices of asset returns, we develop a mesoscale network-based strategy for portfolio optimization that outperforms traditional methods. Specifically, we build correlation-based financial networks and apply core-periphery detection algorithms to identify structurally distinct subsets of assets, namely core and peripheral stocks. The portfolios are then composed based on these structural roles. Using daily and high-frequency stock market data, investment performance is rigorously evaluated using multiple financial metrics. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on centrality-based methods, our method systematically emphasizes peripheral stocks and shows better risk-adjusted returns when they are included in the portfolio.

Our empirical findings consistently indicate that portfolios comprising peripheral stocks, as identified through our core-periphery framework, exhibit lower volatility and superior risk adjusted returns compared to portfolios composed of core stocks, those constructed using benchmark strategies (for example, network centrality-based4), and another core-periphery-based approach. A plausible economic rationale is that peripheral stocks, sparsely connected in the correlation network, are less susceptible to systemic shocks and offer greater diversification benefits. The relatively low pairwise correlations between peripheral stocks enhance diversification within the portfolio, resulting in reduced overall volatility and improved risk adjusted performance. Importantly, this diversification benefit remains effective even in portfolios with a small number of assets. The underperformance of core-based portfolios can be attributed to their vulnerability to herding behavior and market contagion effects. During episodes of financial stress characterized by market crashes or speculative bubbles, correlations between assets typically increase, especially among those central in the network. Investors often exhibit synchronized behavior in such periods, driving highly connected stocks into amplified price swings. Consequently, portfolios concentrated in such central stocks are more likely to experience sharp drawdowns and volatility spikes. Our results suggest that robust portfolio diversification is achievable by targeting peripheral stocks that are not heavily embedded in the market correlation core. Our findings underscore the practical relevance of incorporating mesoscale network structures, such as core-periphery profiles, into portfolio construction frameworks. The approach improves the characteristics of return to risk and aligns with emerging insights from network-based systemic risk analysis, offering a novel perspective on the management of portfolio exposure in complex financial systems. In addition, our methodology provides an intuitive graphical visualization of portfolio composition, enabling investors to interpret the portfolio structure through the topological properties of the financial network.

Our empirical findings suggest that peripheral stocks may be systematically overlooked or underpriced by the market, leading to better risk-adjusted returns when incorporated into portfolio strategies. This observation has significant implications in classical and behavioral financial theories: (i). Efficient Market Hypothesis43 (EMH): The EMH posits that all publicly available information is immediately and wholly reflected in asset prices, implying that no strategy should consistently outperform the market risk adjusted. However, the observed and statistically significant outperformance of portfolios composed of peripheral stocks challenges the semi-strong and strong forms of the EMH. Specifically, it suggests that certain informational or structural inefficiencies persist in the market, particularly for stocks less connected within the financial correlation network. This indicates that not all information is efficiently priced, especially for under-followed or non-systemically central assets. (ii). Fractal Market Hypothesis44 (FMH): Beyond classical perspectives, our findings also resonate with the Fractal Market Hypothesis, which provides a framework for understanding persistent, long-memory dynamics in financial time series. The high prevalence of persistent behavior in stock returns (with 92.31% of stocks showing Hurst exponent \(H > 0.5\)) indicates self-similarity and multi-scale dependencies, features not captured by EMH. FMH accounts for heterogeneous investor time horizons and evolving market structures, making it more suited to explain the non-random, structurally dependent behavior we observe in peripheral assets. Thus, our study finds conceptual alignment with FMH, highlighting the fractal nature of financial markets and the temporal structure of inefficiencies. (iii). Behavioral Finance Perspective45: Behavioral finance offers an alternative explanation rooted in investor psychology and limited cognitive processing. Investors often allocate disproportionate attention to well-known or “attention-grabbing” stocks, which tend to occupy central positions in the financial network. In contrast, peripheral stocks may be ignored or undervalued due to their lower visibility and weaker connections to the broader market. This behavioral tendency aligns with the neglected firm hypothesis46 and limited attention theories, which suggest that under-followed assets command higher expected returns to compensate for reduced investor attention and limited analyst coverage47,48. In this context, a stock’s peripheral position in the network can serve as a proxy for informational neglect. Our findings, particularly the superior risk-adjusted performance of peripheral stocks, are consistent with these behavioral perspectives, offering an interpretation that complements traditional rational-agent frameworks such as the EMH and FMH.

This study contributes to the growing literature on network-based portfolio optimization by demonstrating that peripheral stocks, identified using core-periphery structures in financial networks, can yield superior risk-adjusted returns. The findings highlight the potential of using network mesoscale structures to construct alternative investment strategies beyond traditional centrality-based approaches. Several avenues remain open for future research. Incorporating comparisons with advanced portfolio construction methods such as risk parity or multi-factor models could further enhance our strategy within the broader landscape of portfolio optimization techniques. Furthermore, the framework can be extended by incorporating regime-switching models or volatility-based segmentation to more effectively capture dynamic changes in market structure. Another promising direction is the integration of hypergraph-based network representations, which allow modeling higher-order interactions among multiple stocks, potentially revealing richer structural dependencies than traditional pairwise networks. These extensions can significantly enhance the theoretical foundation, practical relevance, and generalizability of network-based portfolio strategies, opening pathways for future work to establish a more comprehensive and robust framework for financial decision-making.

Data availability

The source code used in this study is publicly available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/Imran10896/Portfolio_optimization. The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

Black, F. & Litterman, R. Global portfolio optimization. Financial Anal. J. 48, 28–43 (1992).

Brinson, G. P., Singer, B. D. & Beebower, G. L. Determinants of portfolio performance ii: An update. Financial Anal. J. 47, 40–48 (1991).

Prices, C. A. A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. J. Finance 19, 425–444 (1964).

Pozzi, F., Matteo, T. & Aste, T. Spread of risk across financial markets: Better to invest in the peripheries. Sci. Rep. 3, 1665 (2013).

Sharma, C. & Habib, A. Mutual information based stock networks and portfolio selection for intraday traders using high frequency data: An indian market case study. PloS One 14, e0221910 (2019).

Markowitz, H. Portfolio selection. J. Finance 7, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1952.tb01525.x (1952).

Cornuejols, G. & Tutuncu, R. Optimization Methods in Finance (Camegie Mellon University, 2005).

Mantegna, R. N. Hierarchical structure in financial markets. Eur. Phys. J. B-Condensed Matter Complex Syst. 11, 193–197 (1999).

Tumminello, M., Aste, T., Matteo, T. & Mantegna, R. N. A tool for filtering information in complex systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 10421–10426 (2005).

Zhao, L. et al. Stock market as temporal network. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 506, 1104–1112 (2018).

Peralta, G. & Zareei, A. A network approach to portfolio selection. J. Empirical Finance 38, 157–180 (2016).

Yang, L., Zhao, L. & Wang, C. Portfolio optimization based on empirical mode decomposition. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 531, 121813 (2019).

Pawanesh, P., Ansari, I. & Sahni, N. Exploring the core-periphery and community structure in the financial networks through random matrix theory. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 661, 130403 (2025).

Sharma, C. & Sahni, N. A mutual information based r-vine copula strategy to estimate var in high frequency stock market data. Plos One 16, e0253307 (2021).

Han, D. et al. Network analysis of the Chinese stock market during the turbulence of 2015–2016 using log-returns, volumes and mutual information. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 523, 1091–1109 (2019).

Guo, X., Zhang, H. & Tian, T. Development of stock correlation networks using mutual information and financial big data. PloS One 13, e0195941 (2018).

Li, Y., Jiang, X.-F., Tian, Y., Li, S.-P. & Zheng, B. Portfolio optimization based on network topology. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 515, 671–681 (2019).

Pai, G. V. & Michel, T. Evolutionary optimization of constrained \(k\)-means clustered assets for diversification in small portfolios. IEEE Trans. Evolutionary Comput. 13, 1030–1053 (2009).

Tola, V., Lillo, F., Gallegati, M. & Mantegna, R. N. Cluster analysis for portfolio optimization. J. Economic Dynamics Control 32, 235–258 (2008).

Nanda, S. J. & Panda, G. A survey on nature inspired metaheuristic algorithms for partitional clustering. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 16, 1–18 (2014).

Ren, F. et al. Dynamic portfolio strategy using clustering approach. PloS One 12, e0169299 (2017).

Nanda, S., Mahanty, B. & Tiwari, M. Clustering indian stock market data for portfolio management. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 8793–8798 (2010).

Lee, S. H., Cucuringu, M. & Porter, M. A. Density-based and transport-based core-periphery structures in networks. Phys. Rev. E 89, 032810 (2014).

Pawanesh, P., Ansari, I. & Sahni, N. Exploring the core–periphery and community structure in the financial networks through random matrix theory. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 130403 (2025).

Borgatti, S. P. & Everett, M. G. Models of core/periphery structures. Social Netw. 21, 375–395 (2000).

Kojaku, S. & Masuda, N. Finding multiple core-periphery pairs in networks. Phys. Rev. E 96, 052313 (2017).

Cucuringu, M., Rombach, P., Lee, S. H. & Porter, M. A. Detection of core-periphery structure in networks using spectral methods and geodesic paths. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 27, 846–887 (2016).

Rossa, F. D., Dercole, F. & Piccardi, C. Profiling core-periphery network structure by random walkers. Sci. Rep. 3, 1467 (2013).

Yang, J. & Leskovec, J. Overlapping communities explain core-periphery organization of networks. Proc. IEEE 102, 1892–1902 (2014).

Rombach, P., Porter, M. A., Fowler, J. H. & Mucha, P. J. Core-periphery structure in networks (revisited). SIAM Rev. 59, 619–646 (2017).

In’t Veld, D., Leij, M. & Hommes, C. The formation of a core-periphery structure in heterogeneous financial networks. J. Econ. Dynam. Control 119, 103972 (2020).

Craig, B. & Peter, G. Interbank tiering and money center banks. J. Financial Intermediation 23, 322–347 (2014).

Meyer, C. D. Matrix analysis and applied linear algebra (SIAM, 2023).

Roncalli, T. Introduction to risk parity and budgeting (CRC press, 2013).

Sortino, F. A. & Price, L. N. Performance measurement in a downside risk framework. J. Investing 3, 59–64 (1994).

Grinold, R. C. & Kahn, R. N. Active Portfolio Management: A Quantitative Approach for Producing Superior Returns and Controlling Risk (McGraw-Hill, 2000).

Pozzi, F., Aste, T., Rotundo, G. & Matteo, T. D. Dynamical correlations in financial systems. In Microelectronics, MEMS, and Nanotechnology, 68021E–68021E–11 (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2007).

Pozzi, F., Matteo, T. & Aste, T. Exponential smoothing weighted correlations. Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 1–21 (2012).

Barbi, A. Q. & Prataviera, G. A. Nonlinear dependencies on Brazilian equity network from mutual information minimum spanning trees. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 523, 876–885 (2019).

Amihud, Y. Illiquidity and stock returns: Cross-section and time-series effects. J. Financial Markets 5, 31–56 (2002).

Hurst, H. E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civil Eng. 116, 770–799 (1951).

Mandelbrot, B. B. Self-affine fractals and fractal dimension. Physica Scripta 32, 257 (1985).

Fama, E. F. Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. J. Finance 25, 383–417 (1970).

Sparrow, C. The fractal geometry of nature. (1984).

Shleifer, A. Inefficient markets: An introduction to behavioural finance (Oup Oxford, 2000).

Merton, R. C. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. Working Paper, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1987).

Barber, B. M. & Odean, T. All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Rev. Financial Studies 21, 785–818 (2008).

Hirshleifer, D. & Teoh, S. H. Limited attention, information disclosure, and financial reporting. J. Accounting Economics 36, 337–386 (2003).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Shiv Nadar University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.A., N.S.; Data Curation: I.A., C.S.; Methodology: I.A., C.S., N.S., A.A.; Validation: I.A., C.S., N.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: I.A., C.S., N.S.; Writing – Review & Editing: I.A., C.S., N.S., A.A.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, I., Sharma, C., Agrawal, A. et al. A novel portfolio construction strategy based on the core- periphery profile of stocks. Sci Rep 15, 36882 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20777-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20777-1