Abstract

Epidemiological evidence support the idea that CST I, L. crispatus-dominated vaginal microbiota, could protect women form cervical HPV infection also favoring the HPV clearance. Our prospective, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on 62 women newly diagnosed of HPV infection without visible cervical lesions at colposcopy, was mainly aimed at evaluating the role exerted by the oral treatment (daily, 4 months) with the strain L. crispatus M247 in prompting the HR-HPV clearance and CST shift. The results of our study demonstrated that the probiotic treatment significantly increased versus control: (i) the HPV clearance (60% versus 31.8%), and (ii) the number of negative PAP tests (83.3% versus 71.4%), favoring also the vaginal microbiota eubiosis. Particularly, the vaginal microbiota analysis demonstrated a significant relationship between the observed HPV clearance and: (i) a reduced richness; (ii) an increased relative presence of L. crispatus; and (iii) an increased number of women with a CST I microbiota. While a larger study would further strengthen these findings, the current evidence provides encouraging insights into the potential efficacy of the oral treatment with the strain L. crispatus M247.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite being preventable by vaccination and screening, cervical cancer is the fourth most common female cancer with approximately 604,000 new cases and 342,000 attributable deaths in 20201. Human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection, is the necessary cause for its development2,3. Although vaccination and screening will continue to be the main prevention strategies for cervical cancer, there is a need for continued research to reduce the disease burden. Lactobacillus species in the female genital tract are described to reduce the risk of bacterial and viral infections and obstetric complications like miscarriage and preterm birth4,5,6,7. Bacterial vaginosis, a polymicrobial disorder characterized by the dominance of anaerobes, (i.e. Gardnerella, Atopobium, Prevotella, Mobiluncus and Peptostreptococcus) and concomitant depletion in Lactobacillus, has previously been associated with the development of cervical cancer, and with the incidence, prevalence, and persistence of HPV8,9,10,11,12. By analyzing the 16S rRNA genes to characterize the vaginal microbiota using vaginal swabs from 396 multi-ethnic and asymptomatic women of reproductive age, in 2011 hierarchical taxonomic clustering analysis was used to classify the vaginal microbial composition of individuals into one of five community state types (CSTs)13. Accordingly, CST I is characterized by the dominance of Lactobacillus crispatus, CST II by that of Lactobacillus gasseri, CST III by that of Lactobacillus iners, and CST V by that of Lactobacillus jensenii. All these four Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs demonstrate low species diversity and evenness. In contrast, CST IV is typically poor or devoid of Lactobacillus spp. being enriched with anaerobic bacterial taxa. Epidemiological studies have then significantly correlated the occurrence of CST III and, particularly, CST IV with a higher risk of HPV infection and persistence and with possible cervical cancer development, and CST I with a “protective” status14,15,16,17,18. According to the vaginal microbiota composition profiles and their relationship with healthy conditions or diseases, the use of vaginal-colonizing probiotics has been recently proposed for HPV clearance and gynecological cancer prevention19. To evaluate the L. crispatus effect in favouring HPV clearance, we and other researchers have started investigating the role exerted by the probiotic strain L. crispatus M24720. A first non-controlled trial, enrolling 35 HPV-positive women among which 24 CST IV, 10 CST III, and 1 CST II, demonstrated, after 90 days of oral treatment, a reduction of about 70% in HPV positivity and a significant change in CST status with 94% of women newly classified as CST I21. A second randomized controlled trial where microbiota analysis were not performed, demonstrated, in 80 women treated for 90 days (versus 80 untreated), that after a median follow-up of 12 months the likelihood of resolving HPV-related cytological anomalies and observing HPV clearance were respectively 20% and 6% higher in women orally treated with the strain M24722. Due to the important limitations of the first two trials, this current work describe a third, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial looking at the effect of orally administered L. crispatus M247 on HPV clearance in relationship to microbiota composition.

Materials and methods

Study ethics and involved centres

This is a randomized, prospective, single blind, multi-center (Hospitals from Palermo, Catania and Lentini, Italy), investigation carried out to delineate the efficacy and safety of the strain L. crispatus M247 in women with a diagnosis of HR-HPV infection. The trial took place between January 2022 and November 2024. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (Registration Number: NCT06802809; First Posted Date: 25/01/2025). Trial was registered retrospectively on ClinicalTrials.gov. The study was conducted in Italy, where, at the time of trial initiation, prospective registration was not mandated by local regulations or ethics committees. The study protocol received ethical approval prior to recruitment from the following Ethic Committees (ECs): “Palermo 1” (protocol number:7; approval date: July 21st, 2021) and “Catania 2” (protocol number: 774; approval date: October 18th, 2021). The EC “Palermo 1” was responsible for the enrolments occurred at Palermo hospital while the EC “Catania 2” was responsible for the enrolments occurred both at the hospital of Catania and at the hospital of Lentini, being this last a small town in the province and under the health jurisdiction of Catania. All patients signed the informed consent at the time of enrolment. The enrolled patients, 66, where equally distributed in the three centres as regards to being treated with probiotic or placebo (Palermo: 8 in the probiotic group; 4 in the placebo one; Lentini: 5 in the probiotic group; 3 in the placebo one; Catania: 31 in the probiotic group; 15 in the placebo one). The study was completed by 62 subjects, 40 from the treated group and 22 from the placebo one. Analysis were performed only on these 62 patients having the four patients abandoned the study on their own choice before the treatment started. Out of the withdrawing patients, 3 were from the Palermo hospital and 1 from the Lentini one. Their withdrawal was not due to side effects or intolerance occurred as a consequence of the therapy (they all belonged to the group treated with the probiotic) but for familiar problems not having, as they declared, any relationship with the study.

Study scheme, patients, enrolment criteria, treatments and diagnostic procedures

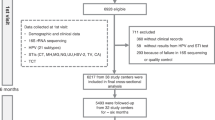

Flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1. Out of evaluated 98 patients attending our hospitals during the period established by the trial protocol, having a diagnosis of HR-HPV infection and aged between 18 and 69 years, the study enrolled 66 women who complied with the enrolment criteria. Patient randomization was performed after considering exposure to cigarette smoke. In fact, it was required that smokers and non-smokers were equally distributed in the two groups (treated and control). After this stratification, each patient was randomly assigned to one of the two groups with a 2:1 ratio in favor of the treated group. As before starting, four patients allocated in the probiotic group abandoned, the treated group was reduced to 40 patients. The inclusion criteria were: (i) being between 18 and 69 years, understanding and accepting participation in the study and being able to provide written informed consent to the trial; (ii) a first diagnosis of HR-HPV infection through DNA-HPV screening test; (iii) being HR-HPV positive patients without visible cervical lesions at colposcopy. Exclusion criteria were: (i) undergone HR-HPV vaccination; (ii) undergone cervical treatments for preneoplastic pathology; (iii) HSIL cytology that following histological examination requires treatment according to the SICPCV 2019 recommendations23; (iv) demonstrated hypersensitivity to one or more components of the product; (v) being treated with probiotics, antibiotics, immunomodulators or immunosuppressants in the three months before the enrolment; (vi) received a diagnosis of immune system or neoplastic pathology or being treated with chemotherapeutics; (vii) be pregnant or breastfeeding or planning to become pregnant in the next nine months. Patients of the treated group were administered with the probiotic strain L. crispatus M247 (LMGP-23257). Treatment was once a day, after breakfast, by dissolving the preparation powder in water or directly into the oral cavity, for four continuous months. Each probiotic sachet contained no fewer than 20 billion colony forming units (CFU) bacteria. The product (Crispact®, Pharmextracta SpA, Pontenure, Piacenza, Italy; notified to the Italian Health Authorities in 2019 with the notification number 115450) was manufactured by Labomar SpA (Istrana, Treviso, Italy). The control group (N = 22) was treated with a placebo preparation with the same modalities as the group treated with the probiotic strain. The placebo was manufactured by the same company that produced the probiotic. Placebo sachets were formulated similarly as the probiotic sachets with the exception of the replacement of the probiotic strain with inactive excipient (maltodextrin). The products, probiotic and placebo, were completely indistinguishable from each other because identical packaging materials were used to prepare them. Only the healthcare personnel involved in the trial were able to distinguish which was the product and which was the placebo because the two different productions had two different batch numbers. Due to the instability of the probiotic strain if stored at room temperature20, the product was stored in the dark at a temperature between 2 and 8 °C. At enrollment and at the end of treatment (4 months), all subjects in both groups underwent: (i) HPV-DNA test; (ii) PAP-test; and (iii) colposcopy examination and were asked to undergo vaginal microbiota sampling.

Study aims

Primary aim was to investigate the ability of L. crispatus M247 to promote HPV clearance. Secondary aims were: (i) investigating the probiotic ability to promote the normalization of cervical cytology; (ii) evaluating the probiotic safety (through daily diary entries by the enrolled patients); (iii) exploring that probiotic treatment was able to modify the vaginal microbiota of the treated patients in favor of the CST I cluster, also evaluating its correlation with the viral clearance.

Dysplastic lesions classification

Dysplastic lesions at cervical level observed according to the cervical-vaginal smear (Pap Test) were classified from a cytological point of view using the Bethesda System24, which includes the following categories: (i) Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US); (ii) Atypical squamous cells – cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H); (iii) Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL or LSIL); (iv) High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL or HSIL); (v) Squamous cell carcinoma; (vi) Atypical Glandular Cells not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS); (vii) Atypical Glandular Cells, suspicious for AIS or cancer (AGC-neoplastic); and (viii) Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS).

HPV-DNA test

The HPV-DNA test, a primary screening method revealing not only the presence (or absence) of the DNA of the human papillomavirus but also allows the identification of the high, medium and low risk genotypes, was performed in our study being a standard of care in our centers. To perform the test, a sample of cells was taken from the cervix with the same methods described for the Pap test. DNA extraction from cervical swabs occurred through the use of the “QIAmp® DNA Mini Kit” kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). Subsequently, the DNA isolated from cervical swabs was quantified using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Molecular analysis occurred using the “EasyPGX® ready HPV” kit and conducted on the EasyPGX® qPCR instrument 96 (Diatech Pharmacogenetics, Jesi, Ancona; Italy) which selectively amplifies the E6 and E7 oncogenes of 14 high-risk HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68). The analysis of the results was performed automatically using EasyPGX® analysis software version 4.0.0 (Diatech Pharmacogenetics, Jesi, Ancona; Italy).

Vaginal microbiota analysis and CST classification

For the purposes of this study, a total of 40 vaginal swab samples were properly collected and storage in sterile tubes containing 1 mL of DNA/RNA Shield from Zymo Research and stored until bacterial DNA extraction. Vaginal samples were subjected to DNA extraction using the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Partial 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified from extracted DNA using the primer pair Probio_Uni/Probio_Rev, targeting the V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene sequence25. Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences were added to the partial 16S rRNA gene-specific amplicons, which were further processed employing the 16-S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol (Part #15044223 Rev. B - Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Amplifications were carried out using a Veriti Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The integrity of the PCR amplicons was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2200 TapeStation Instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The DNA products obtained following PCR-mediated amplification of the 16 S rRNA gene sequences were purified by a magnetic purification step involving Agencourt AMPure XP DNA purification beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics GmbH, Bernried, Germany) in order to remove primer dimers. The DNA concentration of the amplified sequence library was determined by a fluorometric Qubit quantification system (Life Technologies – Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Amplicons were diluted to a concentration of 4 nM, and 5 µL quantities of each diluted DNA amplicon sample were mixed to prepare the pooled final library. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 chemicals. Following sequencing, the.fastq files were processed using a custom script based on the QIIME software suite26. Paired-end read pairs were assembled to reconstruct the complete Probio_Uni/Probio_Rev amplicons. Quality control retained sequences with a length between 140 and 400 bp and a mean sequence quality score > 20, while sequences with homopolymers > 7 bp and mismatched primers were omitted. In order to calculate downstream diversity measures, 16 S rRNA operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined at 100% sequence homology (also called ASVs) using DADA227. OTUs not encompassing at least two sequences of the same sample were removed. Notably, this approach allows highly distinctive taxonomic classification at single nucleotide accuracy28. All reads were classified to the lowest possible taxonomic rank using QIIME229,30 and a reference dataset from the SILVA database31. Biodiversity within a given sample (α-diversity) was calculated using the OTU number. Regarding Lactobacillus partial ITS sequences were amplified from extracted DNA using the primer pair Probio-lac_Uni/Probio-lac_Rev, which targets the spacer region between the 16S rRNA and the 23S rRNA genes within the rRNA locus32. Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences were added to the partial ITS amplicons, which were further processed employing the 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol (Part#15044223 Rev. B - Illumina). PCR amplification as well as library preparation were carried out as described above for the 16S rRNA microbial profiling analyses. Following sequencing, the.fastq files were processed using a custom script based on the QIIME software suite. Paired-end read pairs were assembled to reconstruct the complete Probio-lac_Uni/Probio-lac_Rev amplicons. Quality control retained sequences with a length between 100 and 400 bp and a mean sequence quality score of > 20, while sequences with homopolymers > 7 bp in length and mismatched primers were removed. ITS OTUs were defined at 100% sequence homology using UCLUST30. All reads were classified to the lowest possible taxonomic rank using QIIME29,30, and a reference dataset, consisting of an updated version of the Lactobacillus ITS database32. CST classification was performed according to the Lactobacillus dominance13,33.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The sample of women studied, although modest (N = 62), is largely superior to the samples investigated in studies similar to ours in which the possibility of promoting HR-HPV clearance through the administration of a probiotic or a nutraceutical product was evaluated34,35.

Equivalence between the two groups (probiotic and placebo) was determined using Fisher’s exact test and the two-tailed Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. The difference between the two groups in terms of side effects, was determined using the two-tailed Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. As the regards to the clinical outcomes: Whole model, Wald and Likelihood Ratio tests were used to evaluate HR-HPV clearance; McNemar test was used to evaluate the differences in PAP test; ANCOVA and Wilcoxon Rank Sums methods were respectively use to evaluate richness and to evaluate all taxa, including Lactobacillus, L. crispatus and CST clustering. JMP 10 statistical software for macOS was used and statistical significance was set at 95%.

Results

Descriptive features of the analyzed patients

As shown in Fig. 1, after assessing for eligibility 98 patients, 23 of the them were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (HR-HPV vaccinated, 6 women; current use of probiotics, 12 women; recent use of antibiotics, 5 women) and 9 declined to participate (fear of probiotic-induced bloating, 3 women; not providing explanation, 6 women). After randomization and allocation, 4 women left the study on their own choice before the treatment started. As two were smokers and two were not, the initial requirement about smoking condition (“smokers and non-smokers must be equally distributed in the two groups”) was kept valid (Online Resource 1). Out of the 62 patients left (40 belonging to the probiotic group and 22 belonging to the placebo one), no others abandoned the study during its course. Therefore, all the results shown refers to the 62 patients completing the study. As shown in Table 1 and in Online Resources 2 and 3, the two groups demonstrated no significant differences according to the considered features (age, marital status, parity, educational qualification, socioeconomic level, smoking, birth control pill). The anamnestic analysis of vaginal infections recorded in patients of the two groups between 6 and 3 months before enrollment did not reveal significant differences although some women of the group treated with the probiotic reported some episodes of infection (Online Resource 4).

HPV-DNA test results after 4 months of treatment

We then evaluated if the treatment was significantly able to favor the HR-HPV clearance. As reported in Table 2 and in Online Resource 5, after 4 months of treatment with the probiotic, HPV-DNA test resulted positive in 16 out 40 patients, with a 60% reduction, while in the placebo group the test resulted positive in 15 out 22 patients, with a reduction of 31.8%. To check whether the explanatory variables (treatment and baseline value) were associated with the dependent variable (response at T4), we applied three different statistical methods: Whole Model, Wald and Likelihood Ratio Test (Online Resource 6). The results were all significant (p were respectively: 0.0322, 0.0371 and 0.0322) indicating that at least one of the explanatory variables significantly contributed to explain the dependent variable. In order to validate which explanatory variable was responsible for the observed effect, we analyzed both the intercept and the treatment effects. The intercept represents the log-odds of the negative response when all explanatory variables are 0 (in other words, it represents the value of the dependent variable when the independent variable is zero). Our analysis revealed a not significant result (p = 0.5242) for intercept (Online Resource 7). Differently, the analysis of the impact of the treatment with the probiotic strain demonstrated to be significant (p = 0.0371; Online Resource 7). This result indicates that belonging to the probiotic group increases the log-odds of having the negative response to the HPV-DNA test at T4 compared to the placebo group. We then analyzed the odd ratio for the HR-HPV clearance. Result indicated that patients in the probiotic group have 3.2148 times greater odds (p = 0.0371) to get rid of HPV than the placebo group (Table 2 and Online Resource 8). Since the women enrolled in the study all came from investigations performed as primary screening in which, in case of infection, it is specified only if the strain is HR or LR, the exact qualitative typing of the HR-HPV strain involved in the infection was not available except in a few cases. Differently, most of the HPV-DNA test at the end of the study was performed using molecular probes capable of identifying the HR-HPV serotype that had not been eventually eliminated by the treatment. As shown in Online Resource 9, in the probiotic group we have observed the persistence of serotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 39, 45, 52, 59, 66 and 68; while in the placebo group we have observed the persistence of serotypes 16, 31, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 66 and 68 with no significant differences between the two groups. However, a higher prevalence of persistence of serotypes 16 and 31 was observed in both groups with 11 out of 29 cases (approximately 38%) in the probiotic group and 7 out of 21 cases (33%) in the placebo group.

PAP test and colposcopy results after 4 months of treatment

As reported in Table 3 and in Online Resource 10, after 4 months of treatment, in both groups we observed an increase in negative PAP tests while both ASCUS (Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance) and LSIL (Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) decreased. In the probiotic group the improvement in cervical cytology concerned 83.3% of patients previously positive. In the placebo group this improvement concerned 71.4% of the patients previously positive. According to The McNemar analysis, used to test whether a certain treatment has a significant effect by comparing “before” and “after”, and considering both ASCUS and LSIL as “positive” conditions, only the effect measured in the probiotic resulted to be significant (p < 0.001). The contingency tables to evaluate when the PAP test changes from one category to another (from “positive” to “negative” or vice versa, with “positive” meaning both ASCUS and LSIL) are reported in Online Resource 11. Last, colposcopy were negative for the all 62 patients of the two groups (Online Resource 12).

Tolerability, compliance and side events observed in the two groups during the four months of treatment

Tolerability was reported to be “very good” by 6 patients, “good” by 28 patients and “acceptable” by 6 patients belonging to the probiotic group. Similarly, in the placebo group the same responses were give respectively by 2, 15 and 5 patients. Compliance demonstrated to be quite high since all 62 women of the two groups declared to have been adherent for not less 95% of the treatment doses. Side effects (Online Resource 13) observed in the probiotic group were overlapping, and not significantly different, both for type and severity, with those observed in the placebo group, demonstrating therefore no specificity.

Vaginal microbiota shifts and CSTs

Since only 31 patients in the group treated with the probiotic strain and 9 treated with the placebo preparation properly delivered their both microbiota samples, the analysis were performed only on these 40 patients. Most of the samples missing for analysis were the consequence of: improper storage (10 patients), inappropriate sampling method (6 patients), or declared inability to perform properly the vaginal sampling according to the explained procedure (3 patients). Finally, the samples of a patient was lost by the patient herself and the samples of two patients were found not analyzable due to insufficient quantity of DNA available for analysis. Table 4 reports the results concerning richness (measured as mean ASV number), Lactobacillus and L. crispatus (both reported as relative %) in patients treated with the strain M247 or placebo in relationship with the HR-HPV status observed at the end of the study. As shown, the more the richness decreases and the more the presence of L. crispatus increases, the greater the probability of observing HR-HPV clearance. Since this effect is generally also visible in the placebo group, at least as far as richness is concerned, we have analyzed the impact of the richness values observed at baseline and that exerted by the variable “treatment” on the results. To assess the effect of the probiotic on richness, controlling for baseline ASV levels, the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was chosen. Overall Model demonstrated that, significantly (p < 0.0001), 59.28% of the variability in ASV levels at T4 was indeed explained by the model (Online Resource 14). The analysis of the main effects (HR-HPV clearance and richness decrease) by Ancova then reported: (i) for baseline ASV a coefficient of 1.8723 (p < 0.0001), confirming its strong influence on ASV values observed after 4 months of treatment; (ii) for the probiotic treatment a coefficient of −32.54 (p = 0.0003), demonstrating its role in producing a significant reduction in ASV levels at T4 compared to placebo; (iii) for the interaction between ASV values and probiotic treatment a coefficient of −1.57 (p < 0.0001), suggesting that the efficacy of the probiotic strongly depends also on baseline ASV levels (Online Resource 15). To understand if the effect was mostly due to the baseline ASV values or mostly to the treatment with the probiotic, we have then applied the Adjusted Means Comparison. This analysis clearly highlighted that the adjusted mean ASV value at T4 for the probiotic group was 23.85 [95% CI: 8.54, 39.16] and that for the placebo one was 88.93 [95% CI: 59.26, 118.60]. Being the difference between the two adjusted means (−65.08) highly significant (p = 0.0003), the most important factor affecting the ASV reduction observed in women with HR-HPV clearance was due to the treatment with the probiotic (Online Resource 16). Moreover, analysis performed by Prediction Profiler demonstrated that treatment with the probiotic strain was associated with a significant reduction in richness that was more evident than that observed with the placebo treatment, regardless of the initial values. Furthermore, the interaction suggested that the M247 strain was particularly effective when richness at T0 was higher (Online Resource 17). Concerning Lactobacillus, although an increase by about 25% was observed in those patients treated with the probiotic and clearing the HPV, our analysis did not demonstrate significant shifts between the two groups (Table 4). Differently, a significant shift was observed when analyzing the mean relative percentage of the L. crispatus in women treated with the probiotic strain (Table 4; Fig. 2). Finally, statistical analysis performed comparing all other species of lactobacilli (Online Resource 18) or any other main vaginal taxa (Online Resource 19) did not reveal any significance shift.

Relative percentage of L. crispatus in patients who remained HR-HPV-positive or became HPV-negative in the probiotic and in the placebo group. Values of L. crispatus are reported as mean relative percentage versus the whole vaginal microbiota. Wilcoxon Rank Sums test was adopted for the statistical analysis of the values observed at T4 versus T0 (p = 0.0385 was observed in the Probiotic group; no significant difference was observed in the Placebo Group).

As regards to CST classification (Table 5), at enrollment in the probiotic group 6 women were CST I, 1 was CST II, 6 were CST III, 17 were CST IV and 1 was CST V, while in the placebo group 6 women were CST I and 3 were CST IV. The difference is significant (p < 0.05) despite the process of randomization. After four months of treatment, in the probiotic group 15 women were CST I, 1 was CST II, 5 were CST III, 10 were CST IV and none was CST V, while in the placebo group 4 women were CST I and 5 were CST IV. The significant (p < 0.05) shift (T4 versus T0) observed in the probiotic group due to the increased number of women classified as CST I to the detriment of those classified mainly as CST III and IV, become more relevant when it is evaluated according to the HPV-DNA result at the end of the treatment. As reported in Fig. 3 and Table 5, 12 women were CST I at enrollment (6 in the probiotic group and 6 in the placebo one). After four months of treatment, 15 women of the probiotic group were CST I versus 4 observed in the placebo one. Out of 15 women clustered as CST I in the probiotic group, 11 (about 73%) belonged to the subgroup who cleared HR-HPV and 4 (about 27%) belonged to the subgroup who remained HR-HPV positive. In the placebo group, among the 4 CST I women, 2 were HPV negative and 2 were HR-HPV positive at the end of the treatment.

Discussion

We have carried out a multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the role exerted by the probiotic strain L. crispatus M247 in favoring the HPV clearance and CST shift in women newly diagnosed of HR-HPV infection. Different evidences prompted us to test this assumption36,37,38,39,40. Indeed, current knowledge suggests the existence of the interplay between the cervicovaginal microbiome and the local immunity in HPV infections, emphasizing the role played by the low microbial diversity and by the L. crispatus dominance expressed in the CST I vaginal cluster on immune response. More than a simple assumption, a Lactobacillus-dominant microbiome, particularly with L. crispatus, creates a protective environment through D-lactic acid release, maintaining at the same time a low pH and a polarized Th1 anti-inflammatory immune response41. Our results significantly demonstrate that, besides to be well tolerated, four months of therapy with the L. crispatus M247 strain: (i) doubles the viral clearance (−60% versus − 31.8%) observed at the end of treatment; (ii) determines a 3.2-fold advantage in becoming HPV-negative; (iii) improves, by about 11%, cervical cytology by reducing the diagnoses of ASCUS and LSIL; (iv) reduces the alpha-biodiversity of the vaginal microbiota, with a more evident reduction in women who show HR-HPV clearance; (v) increases the mean relative percentage of L. crispatus, with an incremental delta more evident in women who demonstrate viral clearance; and (vi) increases the number of women in whom the CST shift, in favor of cluster I (that is, characterized by low richness and strong dominance of L. crispatus) is observed, with a shift more evident in women who highlight HR-HPV clearance. Noteworthy, not only the effect on viral clearance is significantly correlated with the vaginal microbiota shift, result that apparently would demonstrated that the more the strain is colonizing, or favoring the establishment of CST I consortium, and the best is the result observed, but it is also correlated with the higher richness of the vaginal microbiota at the enrolment. This could mean that the more the vaginal microbiota is dysbiotic and the more are the advantages that the probiotic treatment can determine. This result could also be correlated with the difference observed at T = 0, despite randomization, as CST groups. The group treated with the probiotic presented indeed a condition more unfavorable for HPV clearance, as the presence of vaginotypes classifiable as CST III or CST IV was significantly increased compared to the placebo group. We have no idea how this difference could have been observed despite randomization other than by resorting to what are perhaps the most significant biases in the study: the low sample size and a different ratio between the number of the two groups and the number of women who actually provided vaginal material for microbiota analysis. Our study has validated, if ever there was a need: (i) the role that vaginal eubiosis can have in relation to viral infection by HPV (independently of the treatment in fact, the more women resulted CST I and the higher was the possibility of determining a prompt viral clearance), and (ii) the possible impact that targeted probiotic therapies, in this case with a Lactobacillus species considered eubiotic for vaginal well-being (L. crispatus), can have on the immune health of the female host. This is because we observed a viral clearance of 60% at 4 months in subjects treated with the probiotic. One might wonder if this percentage can be considered clinically relevant. Several studies have described spontaneous HPV clearance, estimated at approximately 20–30% of cases at three months, almost 50% at six months, and nearly 60–70% at one year42. Consequently, several studies report that over 90% of HPV infections and infection-induced lesions are transitory and resolve spontaneously43. Our results have therefore demonstrated a clearance probably higher than the value expected to occur spontaneously and in any case in the control group the viral clearance that we have observed was significantly lower, approximately 32%. These numbers, even if not beyond any reasonable doubt, would therefore seem to demonstrate a significant role determined by the treatment with the M247 strain. Although the global results that we have got seem to demonstrate that the use of L. crispatus M247 can significantly increase the chances of viral clearance, they do not help us to understand exactly why. Naturally, our hypothesis is that the probiotic can improve the vaginal environment of the woman, enriching and/or restoring a eubiotic vaginal bacterial community (CST I). What we cannot know, however, is whether the eubiotic bacterial community found in women who became CST I following treatment is really due to a total or partial colonization event of the M247 strain. In fact, we cannot exclude that therapy with the strain simply favored normal vaginal physiology to recompose into a eubiotic CST I-type picture without any relationship with the M247 strains. Our previous study on women infected by HPV and a clinical case report have already demonstrated the ability of the M247 strain to effectively restore a CST I but even in these cases we did not have the analytical elements to affirm that the new CST I pictures were really coincident with the administered strain21,44. Anyway, the assumption that the strain could be colonizing remains valid since we had previously conducted a study on healthy volunteers using a probe to specifically detect the presence of the M247 strain. The study had demonstrated that, following oral treatment, the M247 strain was actually found first in the intestine and then in the vaginal environment of treated subjects45. Moreover, other authors, using a different strain of L. crispatus (CTV-05), demonstrated that the change in CST and the strong dominant vaginal presence of L. crispatus was actually attributable to the administered strain with an evident positive impact (also) on the immunological health of the new vaginal context obtained thanks to the treatment46,47,48,49. It must be said, however, that these works, in addition to using a different strain, also used a different administration route, namely via vaginal suppository. Differently, in our trial, we used the oral route, which was described as capable of vaginal colonization50,51,52,53, but still substantially different. Exactly like ours, these studies would support the hypothesis of a vaginal consortium that can manifest itself as the result of a colonization of the used probiotic strain. Other comments deserve to be added. Vaginal bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can be caused by various pathogens (Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma spp. - especially Ureaplasma urealyticum). These agents can coexist with HPV infections and have been associated with cervical cytological abnormalities, such as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL). According to a recent study conducted on a very large sample (N = 2256) of Greek women followed for at least 20 months, the HPV-STI association showed the following incidences: Ureaplasma spp. was detected in 76.9% of positive cases; Mycoplasma hominis in 21.6%; Chlamydia trachomatis in 8.2%; and Mycoplasma genitalium in 1.9%. Coinfections with two bacteria were observed in 10.1% of samples. In our trial, as reported in Online Resource 4, we did not find the same type of association, likely for two reasons. First, the sample enrolled, unlike that of the Greek study, did not have a high prevalence of STIs. Furthermore, the sample size, modest in our study and high in the Greek study, may have contributed to the different results54. A recent paper proposed the validation of scoring systems that quantify factors related to sexual lifestyle55. For example, the crucial role of age at first sexual intercourse is well known, as is the fact that the older the woman, the lower the probability of a positive DNA test. Indeed, analyzing this aspect could help to identify the risk of cervical precancer. Anyway, analyzing this aspect was impossible for us because: (i) the average age of the women in the sample was over 40; (ii) all the women enrolled had their first and only positive HPV test result; and (iii) they were not asked to report the number of sexual partners they had during their medical history. A final comment concerns what we have observed regarding the different HR-HPV serotypes “resistant” to clearance. In fact, although according our protocol we did not intend to evaluate any effect related to a particular HR-HPV serotype, we noted, among the serotypes persistent at 4 months, a higher prevalence of serotypes 16 and 31 in both groups. This phenomenon had already been noted by other authors56. It is possible that patients who demonstrate the persistence of these serotypes have an immune deficit such as to have a particularly low possibility of spontaneous clearance.

Limitation of the study and future direction of investigation

The most important limitations of our study are: (i) the low number of enrolled women, (ii) the low numbers of the microbiota analyses performed, especially in the placebo group where the results were attributable to slightly less than half of the treated women, and (iii) the ratio of microbiota analyses (3:1) compared to a ratio (2:1) with respect to the enrolled women in the two groups. Also worth mentioning is the lack of a double-blind study condition. Our work was performed in a single-blind manner, with only the patients actually unaware of whether they were “treated” or “control”. Other aspect could limitate the validity of our conclusions: data concerning the number of sexual partners and the intrauterine devices (IUDs) were not collected during enrollment. Therefore it was not possible to correlate these aspect with the results. Furthermore, to demonstrate a long-term benefit of oral administration of L. crispatus, it would be necessary to demonstrate greater remission of SIL in patients with persistent HR-HPV infection (for one to two years) in a certainly larger study population. As regards to the future direction of investigation we are planning to organize a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with larger number of women and larger number of microbiota analysis performed. Also to arrive to more definitive answers, in the new trial we will carry out the check with specific probes to obtain qualitative and quantitative data to be attributed to the probiotic strain used.

Conclusions

Our trial, despite some important limitations, has demonstrated that the L. crispatus M247 strain, administered orally for 4 months, in HR-HPV positive women without dysplasia (LSIL/HSIL) on colposcopy, has got a favorable impact on viral clearance, cervical cytology, and vaginal microbiota, demonstrating that the structure of the vaginal microbiota (especially when characterized by low richness and high dominance of L. crispatus) and the specific probiotic therapy (in this case the use of the L. crispatus species) can favorably impact women’s gynecological well-being.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Person of contact: F. Di Pierro; [f.dipierro@vellejaresearch.com] (mailto: f.dipierro@vellejaresearch.com).

Change history

22 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33138-9

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Stanley, M. Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecol. Oncol. 117 (2 Suppl) S5-S10 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.024.

Walboomers, J. M. et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 189 (1) 12–29 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1%3C12::AID-PATH431%3E3.0.CO;2-F.

Mastromarino, P. et al. Effects of vaginal lactobacilli in chlamydia trachomatis infection. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304 (5–6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.04.006 (2014).

Eastment, M. C. & McClelland, R. S. Vaginal microbiota and susceptibility to HIV. AIDS 32 (6), 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001768 (2018).

Bayar, E., Bennett, P. R., Chan, D., Sykes, L. & MacIntyre, D. A. The pregnancy Microbiome and preterm birth. Semin Immunopathol. 42 (4), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-020-00817-w (2020).

Grewal, K., MacIntyre, D. A. & Bennett, P. R. The reproductive tract microbiota in pregnancy. Biosci. Rep. 41 (9), BSR20203908. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20203908 (2021).

Hill, G. B. The microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 169 (2 Pt 2), 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(93)90339-k (1993).

Guo, Y. L., You, K., Qiao, J., Zhao, Y. M. & Geng, L. Bacterial vaginosis is conducive to the persistence of HPV infection. Int. J. STD AIDS. 23 (8), 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2012.011342 (2012).

King, C. C. et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the natural history of human papillomavirus. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 319460. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/319460 (2011).

Gillet, E. et al. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with uterine cervical human papillomavirus infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 11, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-10 (2011).

Gillet, E. et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 7 (10), e45201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045201 (2012).

Ravel, J. et al. Vaginal Microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 108 (Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 4680–4687. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1002611107 (2011).

Di Paola, M. et al. Characterization of cervico-vaginal microbiota in women developing persistent high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 10200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09842-6 (2017).

Mitra, A. et al. The vaginal microbiota associates with the regression of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 lesions. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15856-y (2020).

Chambers, L. M. et al. The Microbiome and gynecologic cancer: current evidence and future opportunities. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 23 (8), 92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01079-x (2021).

Audirac-Chalifour, A. et al. Cervical Microbiome and cytokine profile at various stages of cervical cancer: A pilot study. PLoS One. 11 (4), e0153274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153274 (2016).

Wen, Q. et al. Associations of the gut, cervical, and vaginal microbiota with cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 25 (1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03599-1 (2025).

Mitra, A. et al. Genital tract microbiota composition profiles and use of prebiotics and probiotics in gynaecological cancer prevention: review of the current evidence, the European society of gynaecological oncology prevention committee statement. Lancet Microbe. 5 (3), e291–e300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00257-4 (2024).

Di Pierro, F., Polzonetti, V., Patrone, V. & Morelli, L. Microbiological assessment of the quality of some commercial products marketed as Lactobacillus crispatus-Containing probiotic dietary supplements. Microorganisms 7 (11), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110524 (2019).

DI Pierro, F. et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus crispatus M247 to papillomavirus-infected women: results of a preliminary, uncontrolled, open trial. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 73 (5), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-606X.21.04752-7 (2021).

Dellino, M. et al. Lactobacillus crispatus M247 oral administration: is it really an effective strategy in the management of papillomavirus-infected women? Infect. Agent Cancer. 17 (1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-022-00465-9 (2022).

Ciavattini, A. et al. Italian society of colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal pathology (SICPCV). Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: clinical practice guidelines from the Italian society of colposcopy and cervical pathology (SICPCV). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 240, 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.07.014 (2019).

Pangarkar, M. A. The Bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology. Cytojournal 19, 28. https://doi.org/10.25259/CMAS_03_07_2021 (2022).

Milani, C. et al. Assessing the fecal microbiota: an optimized ion torrent 16S rRNA gene-based analysis protocol. PLoS One. 8 (7), e68739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068739 (2013).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 7 (5), 335–336. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13 (7), 581–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869 (2016).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6 (1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z (2018).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (Database issue), D590–D596. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2013).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (12), 8228–8235. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005 (2005).

Milani, C. et al. Phylotype-Level profiling of lactobacilli in highly complex environments by means of an internal transcribed Spacer-Based metagenomic approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84 (14), e00706–e00718. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00706-18 (2018).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26 (19), 2460–2461. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (2010).

Gajer, P. et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci. Transl Med. 4 (132), 132ra52. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605 (2012).

Verhoeven, V. et al. Probiotics enhance the clearance of human papillomavirus-related cervical lesions: a prospective controlled pilot study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 22 (1), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328355ed23 (2013).

Moscato, G. M. F. et al. A retrospective study on two cohorts of immunocompetent women treated with nonavalent HPV vaccine vs. Ellagic acid complex: outcome of the evolution of persistent cervical HPV infection. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (15), 5509–5519. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202208_29422 (2022).

Graham, S. V. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 131 (17), 2201–2221. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20160786 (2017).

Alizhan, D. et al. Cervicovaginal microbiome: Physiology, Age-Related Changes, and protective role against human papillomavirus infection. J. Clin. Med. 14 (5), 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051521 (2025).

Xu, P. et al. Roles of probiotics against HPV through the gut-vaginal axis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 169 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.16005 (2025).

Zeng, M. et al. Roles of vaginal flora in human papillomavirus infection, virus persistence and clearance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1036869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1036869 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Effectiveness of vaginal probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus chen-01 in women with high-risk HPV infection: a prospective controlled pilot study. Aging (Albany NY). 16 (14), 11446–11459. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.206032 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Altered vaginal cervical microbiota diversity contributes to HPV-induced cervical cancer via inflammation regulation. PeerJ 12, e17415. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17415 (2024).

Rodríguez, A. C. et al. Proyecto Epidemiológico Guanacaste Group. Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100 (7), 513–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn044 (2008).

Petry, K. U., Horn, J., Luyten, A. & Mikolajczyk, R. T. Punch biopsies shorten time to clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus infections of the uterine cervix. BMC Cancer. 18 (1), 318. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4225-9 (2018).

Di Pierro, F., Bertuccioli, A., Cazzaniga, M., Zerbinati, N. & Guasti, L. A clinical report highlighting some factors influencing successful vaginal colonization with probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus. Minerva Med. 114 (6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4806.23.08773-6 (2023).

Di Pierro, F., Bertuccioli, A., Cattivelli, D., Soldi, S. & Elli, M. Lactobacillus crispatus M247: A possible tool to counteract CST IV. Nutrafoods 17, 169–172. https://doi.org/10.17470/NF-018-0001-4 (2018).

Lagenaur, L. A. et al. Connecting the dots: translating the vaginal Microbiome into a drug. J. Infect. Dis. 223 (12 Suppl 2), S296–S306. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa676 (2021).

Armstrong, E. et al. Vaginal Lactobacillus crispatus persistence following application of a live biotherapeutic product: colonization phenotypes and genital immune impact. Microbiome 12 (1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-024-01828-7 (2024).

Lyra, A. et al. A healthy vaginal microbiota remains stable during oral probiotic supplementation: A randomised controlled trial. Microorganisms 11 (2), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020499 (2023).

Armstrong, E. et al. Sustained effect of LACTIN-V (Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05) on genital immunology following standard bacterial vaginosis treatment: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Microbe. 3 (6), e435-e442 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00043-X. Erratum in: Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(7):e479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00156-2.

Strus, M. et al. Studies on the effects of probiotic Lactobacillus mixture given orally on vaginal and rectal colonization and on parameters of vaginal health in women with intermediate vaginal flora. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 163 (2), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.05.001 (2012).

Reid, G. et al. Oral probiotics can resolve urogenital infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 30 (1), 49–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01549.x (2001).

Morelli, L., Zonenenschain, D., Del Piano, M. & Cognein, P. Utilization of the intestinal tract as a delivery system for urogenital probiotics. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 38 (6Suppl), S107–S110. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mcg.0000128938.32835.98 (2004).

Russo, R., Edu, A. & De Seta, F. Study on the effects of an oral lactobacilli and lactoferrin complex in women with intermediate vaginal microbiota. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 298 (1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-018-4771-z (2018).

Valasoulis, G. et al. Cervical HPV Infections, sexually transmitted bacterial pathogens and cytology Findings-A molecular epidemiology study. Pathogens 12 (11), 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12111347 (2023).

Valasoulis, G. et al. The influence of sexual behavior and demographic characteristics in the expression of HPV-Related biomarkers in a colposcopy population of reproductive age Greek women. Biology (Basel). 10 (8), 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10080713 (2021).

Jaisamrarn, U. et al. Natural history of progression of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS One. 8 (11), e79260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079260 (2013). Erratum in: PLoS One. 2013;8(12). https://doi:10.1371/annotation/cea59317-929c-464a-b3f7-e095248f229a.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FDP, EGS, EL Conceptualization; EGS, GEL, MFG, SF, AP, EL Methodology, Investigation, Validation, and Formal analysis; FDP, AK, FR, NMM Resources; FDP, EGS, GEL, MFG, SF, AP, EL Data curation; FDP, EGS Writing–original draft preparation; FDP, EGS, MC, AB, MM, IC, CMP, MLT, NZ Writing–review and editing; FDP, EGS, EL, MLT, NZ Visualization; FDP, EGS, NZ Supervision; FDP, MLT, NZ Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

FDP is the Scientific & Research Director in Pharmextracta SpA. IC, MC and AB are Pharmextracta scientific advisers. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional Information

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Emanuela Gloria Sampugnaro which was incorrectly given as Emanuela Giorgia Sampugnaro.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Pierro, F., Sampugnaro, E., Lomeo, G.E. et al. Effect of orally administered L. crispatus M247 in favoring HR-HPV clearance and CST shift: results from a randomized, multi-center, placebo-controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 36881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20838-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20838-5