Abstract

In this study, we investigated the metal artifact reduction (MAR) performance of a deep learning (DL)-based technique in the evaluation of postoperative CT after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). For the development dataset, we collected CT scans from fifty patients without a metal prosthesis, and for the clinical test dataset, we collected CT scans from 44 patients with a previous history of TKA. We developed a DL-based knee MAR network (KMAR-Net) using 25,000 pairs of simulated images generated from 50 patients using the sinogram handling method. Regarding quantitative analysis, the area, mean attenuation, and standard deviation were calculated for Non-MAR, MAR algorithm for orthopedic implants (O-MAR), and KMAR-Net. For qualitative analysis, overall artifact, bone conspicuity, and soft tissue were compared using visual grading analysis. To additionally validate the feasibility of KMAR-Net under controlled conditions, a phantom study using a CTDI phantom with various metallic inserts and scanning parameters was conducted. KMAR-Net outperformed the projection-completion method regarding the area of dark streak artifacts, mean attenuation, and standard deviation within the artifacts. In the qualitative analysis, KMAR-Net was superior to O-MAR in the overall artifact and soft tissue evaluation, and one of the two readers evaluated it as superior for bone conspicuity (P = 0.080 for reader 1 and P < 0.001 for reader 2). In summary, DL-based KMAR-Net showed superior MAR performance in CT compared to the conventional projection-based method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For patients with advanced osteoarthritis of the knee suffering from intractable pain, knee replacement surgery is the treatment of choice, and the use of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is continuing to increase1,2. Computed Tomography (CT) is an essential modality in evaluating various postoperative complications after TKA3, which are sometimes occult on knee radiographs. However, in CT, severe artifacts caused by large metal prostheses impair diagnostic assessment4.

Metallic implants within the patient severely attenuate or even totally block x-ray penetration, resulting in the corruption of the projection data arriving at the detector5. Metal artifacts occur when the projection data contaminated by metal are used to reconstruct an image, which appears as bright and dark streak artifacts6. Various metal artifact reduction (MAR) techniques to overcome these artifacts in CT images have been investigated over the past several decades5. The traditional approach is to alter the image acquisition and reconstruction parameters using high tube voltage and current, narrow collimation, thin-section acquisition, low pitch values, and soft-tissue reconstruction kernels. However, the clinical use of these methods has limitations in practical applications due to increased radiation exposure and insufficient MAR performance7. The most commonly used method in recent years is to optimize CT acquisition as in the case of dual-energy CT or to use a projection-completion method that replaces corrupted projection data by various interpolation techniques. However, despite many technological developments, there are still artifacts that are not completely overcome by this physics- or knowledge-based approach, especially in the presence of large metallic implants with a high atomic number such as those used for TKA8.

Recently, the rapid development of deep learning (DL) technology has shown outstanding results in diverse fields of radiology, ranging from the detection and characterization of lesions to image quality enhancement using novel reconstruction algorithms9,10,11. Like other radiological fields in which DL-based features begin to outperform existing hand-crafted features, an artificial intelligence (AI) technology with a data-driven approach is expected to be the next breakthrough in the field of MAR research. Several early results have shown that MAR algorithms based on deep neural networks exhibit superior MAR performance in CT compared to conventional techniques12,13,14, but those studies are yet scarce in the medical literature and require validation at various target regions.

Therefore, we investigated the MAR performance of the DL-based knee MAR network (KMAR-Net) for the evaluation of postoperative CT of patients with TKA.

Materials and methods

Study Population and CT Acquisition

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 2006-055-1131). The same committee of Seoul National University Hospital waived the requirement for informed consent, as the data used in this retrospective study were fully de-identified to protect patient confidentiality. All methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. For the development dataset, we retrospectively collected a convenience sample of 50 patients without metal prosthesis who underwent lower extremity CT scans between January 2017 and December 2018. For the temporally-separated clinical test dataset, we collected 44 consecutive patients with a previous history of TKA who underwent lower extremity CT scans using MAR protocol between January 2019 and April 2019. The exclusion criteria for the clinical test dataset were CT scans without MAR protocol and history of orthopedic surgery other than TKA (Fig. 1). All CT examinations in the clinical test dataset were performed with a MAR algorithm for orthopedic implants (O-MAR, Philips Healthcare).

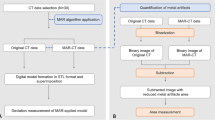

The overall development process of KMAR-Net. A total of 25,000 image pairs were generated through the sinogram handling method to train and validate KMAR-Net. KMAR-Net was trained with the training set of 15,000 image pairs, and the final model was selected with the validation set of 5,000 image pairs. For the simulated test set, the performance of KMAR-Net was evaluated by calculating image quality metrics. Finally, the output images of the KMAR-Net were compared with O-MAR images for the clinical test set.

The scanning parameters were as follows: detector configurations, 64 × 0.625 mm for IQon and iCT (Philips Healthcare), 192 × 0.6 mm for Somatom Force (Siemens Healthcare); tube voltage, 120 kVp; tube current, 50–150 reference mAs; pitch, 0.4–0.8; rotation time, 0.4–0.5 s; matrix, 512 × 512; slice thickness, 2 mm; and reconstruction increment, 2 mm. The reconstruction field of view was 320 × 320 mm covering both knee joints, and CT images were reconstructed using a sharp filter.

Generation of simulated dataset

Since reference images with a metallic implant but completely free of metal artifacts are not present in reality, a simulated dataset was generated by using the sinogram handling method (Fig. 2). We used axial CT scans from 50 patients without metallic implants, each containing more than 100 slices covering the knee joint. Simplified virtual metal shapes resembling commonly used femoral and tibial components in total knee arthroplasty were manually created by referencing real postoperative CT images. To introduce diversity, variations in size, orientation, and positioning were applied. We used slices corresponding to typical TKA locations, such as the distal femur and proximal tibia, with long-stem components simulated in some cases. These virtual implants were then inserted into the axial CT images of patients without metal prostheses, which were used as reference images. An image with metal artifacts was simulated from the virtual metal-inserted images using the sinogram handling method. Each image pair consisted of a metal artifact-free CT slice and its corresponding artifact-simulated image, with multiple variations per slice using different shapes and sizes of virtual prostheses. In this way, 25,000 pairs of simulated images were created from 50 patients, with 500 image pairs generated per patient. Of which 15,000 were used as a training dataset, 5,000 as a validation dataset, and the remaining 5,000 pairs as a simulated test dataset. Further details about the sinogram handling method are provided in Supplementary material and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Development of KMAR-Net

The proposed KMAR-Net architecture and its training process are provided in Supplementary material and Supplementary Fig. 2. The entire code for KMAR-Net was implemented using a DL open framework (PyTorch 1.1.0, Facebook) and can be found at: https://github.com/ljm861/KMAR-Net/blob/master/KMAR-Net.py.

Assessment of KMAR-Net performance

For the simulated test dataset, the reference images were compared with the output images from the trained KMAR-Net. Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), and structural similarity (SSIM) between the output and reference images were calculated for the evaluation of MAR performance.

Regarding the clinical test dataset, metal artifacts were evaluated for each joint on the representative axial image at femoral epicondyle levels for images with no MAR algorithm (Non-MAR), O-MAR, and KMAR-Net. For quantitative evaluation, the area of the dark streak artifact was measured using the method described in our previous study15. We created an outline along the boundary of the knee joint, and a region of interest (ROI) for low-attenuation streak artifacts was created to include all pixels with attenuation values less than or equal to -200 Hounsfield units (HU) within the pre-worked outline. The area, mean attenuation, and standard deviation (SD) of streak artifacts were calculated within the ROI.

A qualitative evaluation was done by two musculoskeletal radiologists (JMK and HDC, with 1 and 6 years of experience in musculoskeletal radiology, respectively). Images were evaluated for the following three entities: the degree of overall metal artifacts, conspicuity of the bony structures, and depiction of soft tissue. To evaluate bone conspicuity, we assessed whether unusual cortical thinning or disruption of cortical continuity was introduced in areas without severe streak artifacts. Soft tissue was evaluated regarding how well distal thigh muscles and subcutaneous fat were visualized. We performed a visual grading analysis for different MAR protocols. For each entity, the image quality was rated with a 5-point Likert scale: grade 1, non-diagnostic; grade 2, poor (severe artifact with the marked impairment in the diagnostic quality); grade 3, fair (moderate artifact with impaired diagnostic quality); grade 4, good (mild artifact with sufficient diagnostic information); grade 5, excellent (very few artifacts). Finally, we investigated whether new artifacts such as pseudocemented appearance—an abnormal hyperattenuating rim around the implant that mimics bone cement and results from overcorrection16 (Fig. 3)—and band-like blurring occurred in both MAR algorithms.

Axial noncontrast CT images of the left knee joint in a 66-year-old woman who underwent total knee arthroplasty. Images were reconstructed using (a) Non-MAR and (b) O-MAR protocols and are shown in the bone window setting (window width = 2000 HU, window level = 500 HU). In the O-MAR image, an abnormally high-attenuated lesion is newly visible adjacent to the lateral femoral condyle, which is not observed in the Non-MAR image. This lesion resembles bone cement and demonstrates a characteristic pseudocement appearance (arrow).

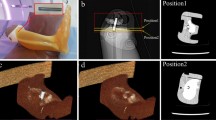

Phantom study

A phantom experiment was performed to test the feasibility of the KMAR-Net and confirm whether the results of the trained network reflect the actual images. We used a CT dose index (CTDI) phantom (RaySafe CT Dose Phantom, Fluke Biomedical) of homogeneous polymethyl methacrylate cylinder (150 mm thickness, 160 mm diameter) with five holes of 13.1 mm diameter. Four stainless steel and four aluminum rods of the same size as the hole of the CTDI phantom were manufactured for the experiment. To generate various degrees of metal artifacts, we scanned the phantom varying the type and number of metallic rods inserted into the phantom (no metal, 1 to 4 stainless steel rods, 1 to 4 aluminum rods, two stainless steel and two aluminum rods). We also varied scanning parameters related to metal artifacts, including tube voltage (100, 120 kVp), slice thickness (1, 2 mm), and reconstruction kernel (bone, standard kernel). CT scans were performed on IQon CT with a fixed tube current of 200 mAs, and other scanning parameters were the same as for the clinical study. Images without a metallic rod were used as the reference image, and 80 phantom images with the metallic rods were used to evaluate the performance of KMAR-Net. We calculated PCC, PSNR, and SSIM and additionally measured mean HU and SD in the box ROI located in a metal-free area to evaluate the similarity between the reference and output images of each MAR protocol.

To train KMAR-Net for phantom study, 474 simulated image pairs were generated from eight images taken without a metallic rod and assigned into one of the following datasets: training dataset (330 image pairs), validation dataset (72 image pairs), and simulated test dataset (72 image pairs). Because the phantom has a relatively simple structure than patients, the number of the simulated image pairs is less than the patient dataset. After training, a phantom test dataset containing real phantom CT images with the metallic rods was used to evaluate the performance of the trained KMAR-Net. Image quality metrics, including PCC, PSNR, and SSIM, were calculated using the phantom CT image taken without a metallic rod as a reference. All metrics were calculated only for the pixels inside the cylindrical phantom, and the pixel values of the metal-containing parts were replaced by water-equivalent attenuation values (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, mean HU and standard deviation were measured in the area without metal using a box region-of-interest (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables, including quantitative measurements, were compared using repeated-measures analysis of variance, and post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed by independent t-test. Qualitative grading results were analyzed by using the Friedman test, followed by post hoc analysis with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust for multiple testing in post hoc analysis. To visualize the frequency distribution of the visual grading score, we provided stacked bar charts. Cohen’s weighted kappa statistics were used to evaluate the interobserver agreement of the visual grading scores between the two radiologists. The frequency of occurrence of new artifacts between the two MAR algorithms was compared using the McNemar test. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (ver. 4.0.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

For the development dataset, we retrospectively collected lower extremity CT scans of 50 patients (68.4 years ± 8.7, 46 women) without a metal prosthesis. Among 176 patients who underwent lower extremity CT between January 2019 and April 2019, we excluded 120 patients who underwent CT scans without MAR protocol and 12 patients with a previous history of orthopedic surgery other than TKA. Finally, 44 patients (70.7 years ± 7.2, 36 women) with a previous history of TKA were included in the clinical test dataset. There were 18 patients with unilateral TKA (nine right and nine left TKAs) and 26 patients with bilateral TKA (Table 1). The types of implants used for TKA in this study include the following: Vanguard Complete Knee System (Zimmer Biomet), Attune Knee System (DePuy Synthes), LPS-Flex Total Knee System (DePuy Synthes), and LCCK (Legacy Constrained Condylar Knee) System (Zimmer Biomet). Of 50 CT scans in the development dataset, 23 were performed with IQon CT, 19 with Somatom Force, and 8 with iCT. For the clinical test dataset, 37 scans were performed using IQon CT and seven scans with iCT.

Simulated and clinical data test results

For the simulated test dataset, image quality metrics were 0.995 for PCC, 41.49 for PSNR, and 0.996 for SSIM (Supplementary Fig. 4). Regarding the clinical test dataset, there were significant differences among the three protocols in all quantitative measurements, including area, mean attenuation, and SD of streak artifacts (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The area of artifacts was the largest in Non-MAR (2165.2 ± 576.5 mm2), followed by O-MAR (1554.6 ± 566.3 mm2), and most of the dark streak artifacts were removed in KMAR-Net (100.6 ± 94.5 mm2). Mean attenuation of artifacts was also the lowest in Non-MAR (− 724.9 ± 71.8 HU), followed by O-MAR (− 424.2 ± 59.4 HU), and KMAR-Net showed the best performance (− 247.7 ± 28.0 HU). The noise within streak artifacts showed similar results with the SD of 295.7 ± 11.7 HU in Non-MAR, 218.8 ± 35.4 HU in O-MAR, and 68.5 ± 50.3 HU in KMAR-Net.

Results of quantitative analysis from the clinical test dataset. (a) The area of dark streak artifacts was the smallest in the KMAR-Net, reducing most of the streak artifacts. (b) The mean HU within the dark streak artifacts was higher in KMAR-Net than in O-MAR. (c) The standard deviation (SD) within the artifacts was the lowest in KMAR-Net.

For qualitative evaluation, the results of interobserver agreement for the visual grading score showed moderate agreement for the degree of overall artifact (κ = 0.59) and conspicuity of the bony structures (κ = 0.43), and good agreement for the depiction of soft tissue (κ = 0.76) between the two radiologists. When comparing three protocols, there were significant differences regarding overall artifact, bony conspicuity, and soft tissue depiction in both radiologists (P < 0.001). In the pairwise comparison, KMAR-Net showed fewer overall artifacts than the other two protocols (P < 0.001). With regard to bony conspicuity, KMAR-Net was significantly superior to Non-MAR (P < 0.001), and when compared to O-MAR, only one reader evaluated that KMAR-Net was significantly superior to O-MAR (P = 0.080 for reader 1 and P < 0.001 for reader 2). In particular, in the evaluation of soft tissue, KMAR-Net showed an image quality of grade 3 or higher in all cases, whereas Non-MAR images evaluated to be poor or non-diagnostic quality in most cases (98% [43/44] for reader 1 and 100% [44/44] for reader 2) (Fig. 5). Pseudocemented appearance occurred in 84% (37/44) in O-MAR and 36% (16/44) in KMAR-Net (P < 0.001). The band-like blurring of soft tissue was observed in 61% (27/44) of KMAR-Net, but was not observed in O-MAR images. Representative cases are shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Results of qualitative analysis from the clinical test dataset. (a) KMAR-Net showed fewer overall artifacts than O-MAR. (b, c) KMAR-Net was superior to O-MAR regarding bone conspicuity and soft tissue evaluation. Most of the Non-MAR images were of non-diagnostic image quality for the evaluation of soft tissue. The visual grading scores are as follows: grade 1, non-diagnostic; grade 2, poor (severe artifact with the marked impairment in the diagnostic quality); grade 3, fair (moderate artifact with impaired diagnostic quality); grade 4, good (mild artifact with sufficient diagnostic information); grade 5, excellent (very few artifacts).

The left knee joint of a 78-year-old woman who underwent revision total knee arthroplasty surgery due to aseptic loosening of the femoral component. (a) A preoperative lateral knee radiograph taken before revision surgery shows radiolucent gaps around the anterior and posterior flanges of the femoral component (long arrows). Axial noncontrast CT images reconstructed with (b) Non-MAR, (c) O-MAR protocol, and (d) KMAR-Net are shown in the bone window setting (window width = 2000 HU, window level = 500 HU). The image of the Non-MAR protocol is of non-diagnostic image quality due to severe streak artifacts. In the O-MAR image, new artifacts of high attenuation that are not visible in the original image interfere with the evaluation of cortical and trabecular bones (arrowhead). KMAR-Net rarely shows these hyperattenuating artifacts while further reducing streak artifacts, and the bone-implant interface gap is more clearly demonstrated (arrows). MAR, metal artifact reduction; O-MAR, metal artifact reduction algorithm for orthopedic implants; KMAR-Net, knee metal artifact reduction network.

The right knee joint of a 69-year-old woman who underwent total knee arthroplasty surgery. Axial CT images reconstructed with (a) Non-MAR, (b) O-MAR protocol, and (c) an output image of KMAR-Net. All images are shown in the soft tissue window setting (window width = 400 HU, window level = 30 HU). The image of the Non-MAR protocol is of non-diagnostic image quality due to severe streak artifacts. In the O-MAR image, a large part of periarticular soft tissue is also covered by metal artifacts. These artifacts are substantially reduced, and the subcutaneous fat and distal thigh muscles around the knee joint are well visible in the output image of KMAR-Net. However, KMAR-Net introduces band-like soft tissue blurring of ground-glass appearance (arrow). MAR, metal artifact reduction; O-MAR, metal artifact reduction algorithm for orthopedic implants; KMAR-Net, knee metal artifact reduction network.

Phantom study

In the phantom experiment, Non-MAR showed image quality metrics of 0.928 for PCC, 31.27 for PSNR, and 0.895 for SSIM. These metrics improved to 0.985 for PCC, 35.85 for PSNR, and 0.938 for SSIM when O-MAR was used. The performance of the proposed KMAR-Net for phantom was higher than that of O-MAR with PCC, PSNR, and SSIM values of 0.994, 39.64, and 0.988, respectively (Fig. 8). The mean attenuation in the box ROI within the phantom of Non-MAR and O-MAR was 94.2 and 108.2 HU, respectively, which was lower than that of the reference image (118.7 HU). In the case of KMAR-Net, the mean attenuation was 117.3 HU, which was quite similar to the reference. SD was also the lowest in the KMAR-Net (19.2 HU) among the three protocols (Table 2).

Representative result images of phantom study. KMAR-Net showed superior MAR performance than O-MAR in the phantom test dataset. O-MAR effectively removes metal artifacts from aluminum rods, but residual streak artifacts can be seen when severe artifacts are present due to stainless steel rod. MAR, metal artifact reduction; O-MAR, metal artifact reduction algorithm for orthopedic implants; KMAR-Net, knee metal artifact reduction network.

Discussion

Our DL-based MAR technique significantly improved metal artifact reduction compared to the projection-completion method. KMAR-Net showed the best performance in quantitative measures such as area, mean HU, and SD of streak artifacts. The subjective image quality of KMAR-Net was also superior to O-MAR. In the phantom study, KMAR-Net showed attenuation value and standard deviation similar to reference images.

For the supervised learning of MAR, an artifact-free image is required as a reference, which is difficult to obtain in actual CT images. In several recent studies, various methods have been proposed to address this problem by simulating metal artifacts and generating training data from artifact-free images. Gjesteby et al.14 used commercial CT simulation software, CatSim (GE Global Research Center)17, to generate the artifact-free and metal-corrupted images. They reported that their dual-stream network is superior to normalized MAR method in the pelvic and spinal regions. Zhang et al.18 produced training data stacked as a three-channel image by combining a simulated metal artifact image with the pre-corrected results from two simple MAR methods, linear interpolation and beam hardening correction. They attempted to further reduce artifacts by performing a tissue preprocessing step replacing metal-affected projections with the forward projection of the prior image. In a study by Lyu et al.19, they proposed a dual-domain network by connecting two networks enhancing images in both image- and projection-domains and used simulated metal-contaminated sinogram and metal mask projection as input data.

Several recent studies have explored the use of deep learning for MAR in CT imaging (Table 3)20,21,22,23. While most methods vary in target region, network architecture, and evaluation metrics, they consistently demonstrate improved artifact suppression compared to conventional methods. For instance, Selles et al. showed that DL-MAR achieved significantly higher diagnostic confidence and image quality in hip CTs than both conventional and dual-energy methods with O-MAR. Similarly, Puvanasunthararajah et al. validated their models using CT scans with simulated metal artifacts, reporting strong improvements in SSIM, PSNR, and HU accuracy. Although these outcomes are promising, direct comparison of different DL-based MAR algorithms remains difficult due to differences in datasets, anatomical targets, and evaluation metrics.

While hip and spine implants have been studied in cohorts of a few dozen patients, knee arthroplasty CT has seen little attention in the deep learning MAR literature. Our proposed method showed significantly improved MAR performance even in patients with severe metal artifacts caused by large metal prostheses such as TKA. In addition, many studies perform metal segmentation at a particular stage of the MAR process5,18,19, which can create secondary artifacts by inaccurate metal segmentation. However, this problem can be prevented in this study, because KMAR-Net does not use a priori knowledge about the metal shape and skips the metal segmentation step.

One of the pitfalls of the currently widely used projection-completion techniques is that, while reducing metal artifacts, they often delete normal anatomical structures such as cortical bone, resulting in pseudolesions mimicking osteolysis24. They can also introduce new artifacts such as hyperattenuating areas that are not visible in the original image25. Our proposed method has improved these shortcomings and showed significantly better performance than O-MAR in the evaluation of bony structure, which may be particularly useful for assessing lesions such as periprosthetic loosening (Fig. 6). However, when KMAR-Net was used, band-like blurring of soft tissue was newly introduced in areas where severe streak artifacts were previously present. Nonetheless, this artifact was significantly smaller than the pre-existing streak artifacts, and it had relatively little effect on image quality in the subjective analysis of radiologists.

Metal artifacts are caused by a combination of several mechanisms, including beam hardening, photon starvation, scattering, and non-linear partial volume effect5,6. Although we used the sinogram handling method to simulate metal artifacts, this simulated metal artifact is not precisely the same as the actual metal artifact and may not reflect some components of artifacts. Due to this discrepancy between the simulated and the real image, when applied to real clinical images, the trained model may have limitations in generating a completely artifact-free image. Therefore, to improve the performance of DL-based MAR algorithms, it is necessary to develop advanced simulation algorithms that reflect the complex X-ray physics and geometry of CT hardware underlying the metal artifacts generation.

One notable finding was that the evaluation of bone conspicuity varied with radiologists’ experience, showing the lowest interobserver agreement among the qualitative metrics (κ = 0.43). The more experienced radiologist (6 years) did not find a significant difference between O-MAR and KMAR-Net, likely reflecting greater ability to recognize normal anatomy despite residual artifacts. In contrast, the less experienced radiologist (1 year) was more influenced by artifact burden, leading to a stronger preference for KMAR-Net. These results indicate that the degree to which artifact affects qualitative judgment can differ substantially depending on radiologists’ experience.

This study had several limitations. First, the clinical test dataset consisted of a relatively small number of patients with a female-dominant distribution. However, this imbalance, along with sex-related anatomical differences in skeletal and soft tissue structure, may affect model performance and limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, variability in implant styles and materials could influence artifact characteristics, and future studies should explore their impact on model robustness. Second, we compared KMAR-Net only with a commercial projection-based MAR algorithm. While this reflects a clinically relevant baseline, comparisons with other MAR approaches—including dual-energy CT, hybrid methods15, and more advanced DL-based techniques such as transformer or diffusion models—would provide a more comprehensive evaluation and should be addressed in future studies. Third, although band-like blurring artifacts generally affect a smaller area than severe streak artifacts, they may still distort important anatomic features or lesions, potentially introducing bias in interpretation. Moreover, the inability to analytically explain the cause of such artifacts highlights a fundamental limitation of deep learning–based models. Fourth, the simulation did not fully account for all physical components contributing to metal artifacts, including cone-beam effects related to tube current modulation. Incorporating these factors into future simulation pipelines may improve the model’s generalizability to real-world images. Finally, it is necessary to verify whether the AI-generated images actually reflect the anatomic structures and true lesions. Although we performed a phantom study to evaluate the similarity of the simulated image and actual structure, it is necessary to validate with the patients confirmed with a postoperative complication in future studies.

In conclusion, KMAR-Net showed superior MAR performance in CT compared to a conventional projection-completion method and is thus a promising candidate to evaluate a postoperative CT after TKA.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are not publicly available because of the private health information policies of participating institutions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- MAR:

-

Metal artifact reduction

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- KMAR-Net:

-

Knee metal artifact reduction network

References

Price, A. J. et al. Knee replacement. Lancet 392, 1672–1682 (2018).

Bruyere, O. et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum 44, 253–263 (2014).

Mulcahy, H. & Chew, F. S. Current concepts in knee replacement: complications. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 202, W76-86 (2014).

Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging: Hochman, M. G. et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria((R)) Imaging After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 14, S421–S448 (2017).

Gjesteby, L. et al. Metal artifact reduction in CT: Where are we after four decades?. IEEE Access 4, 5826–5849 (2016).

Katsura, M., Sato, J., Akahane, M., Kunimatsu, A. & Abe, O. Current and novel techniques for metal artifact reduction at CT: Practical guide for radiologists. Radiographics 38, 450–461 (2018).

Lee, M. J. et al. Overcoming artifacts from metallic orthopedic implants at high-field-strength MR imaging and multi-detector CT. Radiographics 27, 791–803 (2007).

Wellenberg, R. H. H. et al. Metal artifact reduction techniques in musculoskeletal CT-imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 107, 60–69 (2018).

Shin, Y. J. et al. Low-dose abdominal CT using a deep learning-based denoising algorithm: A comparison with CT reconstructed with filtered back projection or iterative reconstruction algorithm. Korean J. Radiol. 21, 356–364 (2020).

Masutani, E. M., Bahrami, N. & Hsiao, A. Deep learning single-frame and multiframe super-resolution for cardiac MRI. Radiology https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020192173 (2020).

Rodriguez-Ruiz, A. et al. Detection of breast cancer with mammography: Effect of an artificial intelligence support system. Radiology 290, 305–314 (2019).

Zhu, L. et al. Metal artifact reduction for X-ray computed tomography using U-net in image domain. IEEE Access 7, 98743–98754 (2019).

Lee, D., Park, C., Lim, Y. & Cho, H. A metal artifact reduction method using a fully convolutional network in the sinogram and image domains for dental computed tomography. J. Digit. Imaging 33, 538–546 (2019).

Gjesteby, L. et al. A dual-stream deep convolutional network for reducing metal streak artifacts in CT images. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, 235003 (2019).

Chae, H. D., Hong, S. H., Shin, M., Choi, J. Y. & Yoo, H. J. Combined use of virtual monochromatic images and projection-based metal artifact reduction methods in evaluation of total knee arthroplasty. Eur. Radiol. 30, 5298–5307 (2020).

Shim, E. et al. Metal artifact reduction for orthopedic implants (O-MAR): Usefulness in CT evaluation of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Am. J. Roentgenol. 209, 860–866 (2017).

De Man, B. et al. CatSim: A new computer assisted tomography simulation environment. In Medical Imaging 2007: Physics of Medical Imaging Vol. 6510 65102G (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2007).

Zhang, Y. & Yu, H. convolutional neural network based metal artifact reduction in X-ray computed tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 1370–1381 (2018).

Lyu, Y., Lin, W.-A., Lu, J. & Zhou, S. K. DuDoNet++: Encoding mask projection to reduce CT metal artifacts. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.00340 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Preclinical validation of a novel deep learning-based metal artifact correction algorithm for CT images of patients with orthopedic implants. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 24, e14166 (2023).

Puvanasunthararajah, S., Camps, S. M., Wille, M. L. & Fontanarosa, D. Deep learning-based ultrasound transducer induced CT metal artifact reduction using generative adversarial networks for ultrasound-guided cardiac radioablation. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 46, 1399–1410 (2023).

Selles, M. et al. Is AI the way forward for reducing metal artifacts in CT? Development of a generic deep learning-based method and initial evaluation in patients with sacroiliac joint implants. Eur. J. Radiol. 163, 110844 (2023).

Selles, M. et al. Deep learning-based metal artifact reduction improves image quality and diagnostic confidence in CT after total hip arthroplasty. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 8, 31 (2024).

Philips Healthcare, Metal artifact reduction for orthopedic implants (O-MAR). https://www.philips.co.uk/c-dam/b2bhc/master/sites/hotspot/omar-metal-artifact-reduction/O-MAR%20whitepaper_CT.pdf (2012).

Shim, E. et al. Metal artifact reduction for orthopedic implants (O-MAR): Usefulness in CT evaluation of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 209, 860–866 (2017).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the MSIT under Grant NRF-2021R1F1A1057818 and Grant RS-2024–00344958; and in part by an Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No.RS-2020-II201336, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (UNIST)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L, H.C., and S.J.Y. designed the study and wrote the main manuscript text. J.L. and H.C. developed the KMAR-Net model. S.H.H., J.Y.C., H.J.Y. and J.M.K. collected the data and reviewed the images. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.J.Y., J.L., H.D.C., and H.C. are co-inventors on a patent application that related to the methods in this paper: “Apparatus and Method for Removing Metal Artifact of Computer Tomography Image Based on Artificial Intelligence” Application number KR10-2019-0159149. S.H.H., J.Y.C., H.J.Y. and J.M.K. have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Chae, HD., Cho, H. et al. Deep learning-based metal artifact reduction in CT for total knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep 15, 39587 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21012-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21012-7