Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of the quality of tourism services on the quality of life of individuals with disabilities, with a particular focus on the challenges they face while traveling in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, the study sought to determine whether these challenges varied depending on the type of disability. A quantitative, cross-sectional survey design was employed, and data were collected from 173 participants via a structured survey. Findings revealed that individuals with disabilities encountered various personal, social, and structural challenges during their tourism experiences. Moreover, significant differences were found in personal and structural challenges across different disability types, whereas no statistically significant differences were identified in social challenges based on the type of disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concern for the quality of tourism services provided to individuals with disabilities has become a vital topic, receiving increasing attention in research circles and the global tourism industry, especially in light of international trends toward promoting inclusiveness and achieving social justice1. Recent studies indicate that inclusive tourism has shifted from being a secondary consideration to becoming a priority in many national and international policies related to sustainable development and human rights2,3,4,5,6. Darcy and Dickson3 indicated that tourism is no longer a luxury or a recreational activity restricted to a specific group; it has become an influential factor in achieving quality of life, especially for the most vulnerable and marginalized groups, including individuals with disabilities. The World Tourism Organization7 also reports that tourism for individuals with disabilities is an integral part of human rights and a development imperative that must not be overlooked in national policies, especially in countries seeking to expand community participation in sustainable development.

According to Kastenholz and Rodriguez8, with countries’ growing interest in the tourism sector as a source of income and economic enhancement, a new concept called “inclusive tourism” has emerged and is being used to shape global tourism policies. This concept has transformed traditional ideas of tourism to encompass all segments of society, including individuals with disabilities. Specifically, inclusive tourism focuses not only on providing services but also on creating an appropriate tourism environment that enables individuals with disabilities to enjoy experiences comparable to those of individuals without disabilities. From this perspective, the significance of inclusive tourism lies in promoting individuals with disabilities’ right to fully participate in social and cultural life, which contributes to enhancing their quality of life9. A review of reports and literature indicates that the concept of inclusive tourism includes offering a range of facilities that ensure easy access and movement within tourist attractions, such as accessible hotels, transportation, and public amenities that provide comfort and support for individuals with disabilities. This tourism also necessitates the development of systems and mechanisms in tourist locations that allow individuals with disabilities to navigate and interact with the tourist environment freely and without barriers. This includes providing clear information about accommodations, recreational facilities, and health services that meet their specific needs9,10,11,12,13,14. High-quality tourism services are essential for improving the quality of life for individuals with disabilities because they provide an accessible tourism environment that enhances their physical, psychological, and social well-being9,12. According to Adhikari and Liu15, the availability of diverse tourism facilities and services can enhance the independence of individuals with disabilities, allowing them to enjoy tourism experiences without barriers. This improvement in accessibility to tourist attractions is not limited to physical facilities; it also extends to creating a positive psychological and social environment that helps reduce barriers, such as feelings of isolation or marginalization experienced by many individuals with disabilities. Furthermore, Müller and Sørensen5 assert that tourism plays an important role in enhancing the mental health of individuals with disabilities, as inclusive tourism contributes to improving self-confidence and reducing anxiety and depression. On a social level, the quality of tourism services provides individuals with disabilities opportunities to interact with the surrounding community and participate in cultural and recreational activities, enhancing their sense of belonging and equality.

Although improving tourism services is essential for enhancing the quality of life for individuals with disabilities, many challenges exist whose impact varies based on the type of disability, significantly affecting the effectiveness of these services. Several studies have indicated that some types of disabilities encounter more significant challenges in tourism than others15,16,17,18. For example, a study by Buhalis and Law10 found that individuals with physical and motor disabilities experience greater difficulties accessing tourist attractions if transportation or hotels lack the equipment to meet their specific needs, such as the absence of ramps or elevators that allow for free movement. More importantly, providing accessible facilities for individuals with physical and motor disabilities requires substantial investment in tourism infrastructure, which may not be feasible in all tourist destinations5. On the other hand, Pereira and Pinto9 noted that individuals with sensory disabilities, such as visual impairments or hearing loss, struggle with a lack of assistive devices like audio or visual cues that enable them to navigate easily within tourist attractions. Regarding individuals with intellectual disabilities, Kastenholz and Rodriguez8 reported that these individuals may require additional support to comprehend tourist information or interact with activities due to challenges in navigating their environment. Therefore, achieving inclusive tourism necessitates first understanding the unique challenges faced by individuals with disabilities and then providing suitable solutions that consider individual differences among them to ensure an inclusive tourism experience for all.

Tourism for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has witnessed remarkable development in the tourism sector in recent years19. Tourism has become a crucial component of the country’s plans for the coming years, aimed at diversifying the national economy and reducing dependence on oil. According to the Saudi Ministry of Tourism19, there has been significant growth in the number of tourists visiting Saudi Arabia over the past few years, with the number of Saudi tourists increasing from 43.3 million in 2018 to 81.9 million in 2023, and the number of foreign tourists rising from 15.3 million to 27.4 million during the same period. Additionally, the Ministry of Tourism confirmed that the total number of tourists to Saudi Arabia in the first half of 2024 reached 60 million, including 44 million domestic tourists and 15 million international tourists. Tourism for individuals with disabilities is a vital part of Saudi Arabia’s plans and strategies, as the country strives to achieve an inclusive tourism environment accessible to all segments of society, including this group of people20. Alrashid21 emphasized that many steps have been taken to enhance the tourism environment in alignment with the specific needs of individuals with disabilities. These efforts range from developing tourism facilities and updating legal systems to providing specialized tourism programs designed to facilitate the movement of individuals with disabilities within tourist attractions. One of the most important initiatives launched by Saudi Arabia in this context is the “Inclusive Tourism” program, which aims to prepare tourism facilities and public areas according to universal design principles for individuals with disabilities. Furthermore, tourism laws have been updated to include the rights of individuals with disabilities, ensuring they receive an integrated tourism experience that encompasses accommodation, transportation, recreational activities, and cultural events22.

Despite notable advancements in the formulation of regulations and legislation, as well as the provision of tourism services tailored for individuals with disabilities in recent years, challenges persist for these individuals in their tourism experiences across many cities and tourist areas in Saudi Arabia23. According to Alharbi and Alkhathlan18, the most prominent of these barriers include limited access to tourist facilities, such as hotels, public amenities, and transportation, which do not adequately address the needs of individuals with disabilities in certain cities. Moreover, many tourist facilities often lack essential accessibility features, such as ramps or elevators for those with mobility impairments, and even audio-visual guides that assist individuals with hearing and visual disabilities. Additionally, Hossain and Fadlalla24 pointed out that numerous individuals with disabilities and their families face social and psychological challenges arising from the social stigma they may encounter, which can hinder their full participation in tourism activities. They noted that this sense of isolation may stem from a lack of awareness or training among tourism sector personnel regarding how to assist visitors with disabilities. Another significant challenge for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia, as highlighted by Aldosary and Alshehri17, is the absence of tourism information specifically aimed at this demographic, whether regarding facilities designated for them or available tourism activities. Furthermore, the lack of collaboration between governmental and private entities may also impede progress in this area.

This study examined how the quality of tourism services affects the quality of life for individuals with disabilities. It sought to identify the personal, social, and structural challenges faced by tourists with disabilities in Saudi Arabia, focusing on how these challenges differ among various types of disabilities, including intellectual, learning, physical, visual, and others. The study addressed the following two research questions: (1) What personal, social, and structural challenges limit the accessibility of tourist attractions for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia? (2) To what extent do these challenges vary based on the type of disability? By systematically assessing these challenges, as demonstrated in previous studies25,26, this study provides valuable insights into the lived experiences and specific needs of individuals with disabilities.

Methodology

Research design

To explore the effect of tourism service quality on the quality of life of individuals with disabilities, the current study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design. The researchers collected the data through a structured survey and analyzed it using descriptive and inferential statistics. This research design is useful at a single point in time to identify relationships, patterns, and differences between variables27,28,29. It is also valuable when statistical evidence is needed to address the research problem.

Population and participants

Research participants include individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. According to the latest statistics issued by the General Authority for Statistics30, disability prevalence reached 1.8% of the total population in Saudi Arabia. The authority reported that 41.5% of individuals had a single disability, while 58.5% had multiple disabilities, depending on the degree of severity, among all individuals with one or more disabilities in the target sample. The statistics also showed that the percentage of individuals with a visual disability was 21.8%, while the percentage of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals was 7.0%. Furthermore, the percentage of individuals with communication difficulties was 2.7%, and the percentage of individuals with physical disabilities reached 52.6% of the total individuals with one disability. Statistics indicate that 68.2% of individuals with disabilities in the 2–4 age group have multiple disabilities, while 31.8% have only one disability. For the 5–17 age group, 60% have multiple disabilities, while 40% have only one disability. Finally, 58% of individuals with disabilities aged 18 and older have multiple disabilities, while 42% have only one disability.

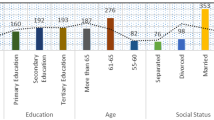

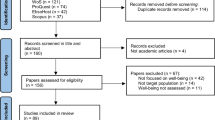

To determine the appropriate sample size for the current study, the researchers used G*Power 3 software. The key parameters included a medium-to-large effect size (f = 0.30), statistical power of 0.80, seven disability types, and an α level of 0.05. The analysis showed that the required sample size to achieve the specified power while controlling for Type I and Type II errors is 161 participants31,32. This sample size meets the statistical benchmarks for reliability and robustness in hypothesis testing33. A total of 178 responses were initially collected. However, the researchers excluded five responses due to missing data on key outcome questions, leaving a final sample of 173 participants. As shown in the Table 1, 67.1% of the participants were individuals with disabilities, 26.6% were family members of individuals with disabilities, and 6.4% were assistants to individuals with disabilities. Most participants were male (61.3%) and single (62.4%). In terms of disabilities, 42.8% had physical or motor disabilities, 21.4% were deaf or hard-of-hearing, 17.9% had visual disabilities, 8.1% had an intellectual disability, 4.7% had autism spectrum disorder, 2.9% had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 2.3% had learning disabilities. Regarding travel habits, 72.8% of individuals with disabilities typically travel with their families. Most respondents reported having tourism experience in the Riyadh region (28.9%) and the Makkah region (22.5%). The majority of participants were aged 18–25 years (29.5%), followed by those aged 26–35 years (23.7%).

Survey instrument

The researchers developed the survey after reviewing literature on how tourism service quality affects the lives of individuals with disabilities. They titled the survey, “Tourism Services for Individuals with Disabilities in Saudi Arabia.” It consisted of four sections, with the first providing participants with detailed information about the study’s purpose, confidentiality, their rights, and general instructions for completing the survey. The second section requested demographic information, including: (1) age; (2) participant description; (3) gender; (4) marital status; (5) type of disability; (6) travel partner(s); and (7) area of tourist experience. The researchers categorized the variables in the second section in multiple ways, such as the lowest age group being ‘under 18 years old’ and the highest age group being ‘over 56 years old’.

The third section comprises 33 items divided into three factors. The first factor concerns personal challenges and includes 6 items, such as "I feel there is a lack of knowledge about the needs of individuals with disabilities in the tourism industry" and "there is often confusion in understanding the difference between disability and illness among tourism service providers". The second factor addresses social challenges and contains 4 items, such as "tourism service providers’ expectations about the capabilities of individuals with disabilities affect the availability of options for them," and "tourism service providers often do not strive to facilitate effective communication for individuals with disabilities." Finally, the third factor pertains to structural challenges and consists of 23 items, such as "there is a lack of visibility of available universal access services within the overall marketing efforts of the tourism sector," "traveling with an escort imposes double the cost for individuals with disabilities," and "accessible transportation is more expensive than public transportation for individuals with disabilities." The researchers measured the items in the third section on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The Likert scale is widely used for measuring items since it captures nuanced answers that go beyond agree/disagree or simple yes/no options. It enabled the researcher to determine the degree or intensity of opinions, attitudes, or perceptions34,35. Moreover, the Likert scale measurement allowed for the quantification of qualitative data for statistical analysis and comparison across groups36.

Instrument validity

Content validity

In the current study assessing tourism services for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia, the researchers emphasized expert validation to achieve content validity. The first step involved identifying the key dimensions of constructs through prior studies and a literature review37. Next, the researchers recruited four experts with diverse expertise in Saudi tourism policy, disability advocacy, and accessibility design37. In the third step, the experts provided qualitative feedback; they rated coherence, clarity, and cultural appropriateness and offered open-ended comments. Finally, the researchers added, adjusted, or eliminated items based on the experts’ feedback.

Construct validity

The researchers conducted a factor analysis to establish construct validity. Factor analysis simplifies complex variable relationships by identifying latent variables that describe patterns in observed data16. In this study, the researchers performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test hypothesized factor structures.

To assess the construct validity of personal challenges, which is one of the proposed latent variables, the researchers performed factor analysis, with the KMO value and Bartlett’s test indicating that the data were suitable for this analysis. Additionally, using principal component analysis, a single factor was extracted (all items loaded onto a single component), with factor loadings ranging from 0.518 to 0.769, confirming the construct validity and unidimensionality of the scale. The researchers observed similar results when assessing the construct validity of social challenges (factor loadings ranging from 0.656 to 0.750), where all four items loaded onto a single component, representing the latent construct. However, in the case of structural challenges, one of the 23 items had a small factor loading score (< 0.3), suggesting a weak relationship between the underlying factor and the observed items. Therefore, the item, “Customer service in the tourism sector treats individuals with disabilities fairly and communicates with them using appropriate language (R)”, was excluded.

Instrument reliability

The researchers determined the instrument’s reliability by computing Cronbach’s alpha to assess internal consistency reliability. Cronbach’s alpha is widely used to evaluate the internal consistency of multiple-item scales, indicating whether items are closely related as a group38. The generally accepted threshold is α ≥ 0.7038,39; however, values greater than 0.6 are also considered acceptable (Taber, 2018). As shown in Table 2, the researchers found the overall reliability of the instrument to be 0.927, suggesting an acceptable level of internal consistency. Furthermore, they calculated the coefficient alpha for each factor as follows: Factor I (6 items) = 0.675, Factor II (4 items) = 0.668, and Factor III (23 items) = 0.916.

Data collection

After obtaining ethical approval No. SCBR-499/2025 from the Standing Committee for Bioethics Research (SCBR) at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University to conduct the study, the researchers randomly distributed the survey to the participants, including both male and female individuals with disabilities. Due to the type and severity of certain disabilities that might prevent individuals from completing the survey themselves, the researchers took steps to ensure fair and accurate representation by involving family members and assistants to complete the survey on behalf of individuals with disabilities. To obtain a representative sample of individuals with disabilities who had previously received tourism services in Saudi Arabia, the researchers first contacted 50 entities across Saudi Arabia involved in providing services to individuals with disabilities, including government agencies, disability associations, and university disability centers, to distribute the survey to their beneficiaries. Additionally, the researchers posted the online survey on the websites of associations for individuals with disabilities and their Twitter accounts to ensure broader participation.

Data analysis

Given the quantitative nature of the study, personal, social, and structural challenges that limit the accessibility of tourist attractions for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia were identified using frequency analysis. This process organizes, summarizes, and presents data by counting how often certain categories or values occur. It also includes percentages to facilitate comparison and interpretation.

To examine whether personal, social, and structural challenges faced by tourists with disabilities differ based on the type of disability, the researchers conducted a one-way ANOVA. For this test, latent constructs (composite variables) of the three challenges were computed based on the results of reliability and validity and used as the outcomes. A one-way ANOVA compares the average scores of three or more independent groups and determines significant differences in the outcomes40. Before conducting the test, the researchers ensured that the composite variables representing the challenges followed a normal distribution. The researchers performed all tests using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 2741.

Results

-

1.

What are the personal, social, and structural challenges that limit the accessibility of tourist attractions for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia?

The frequency analysis showed that among personal challenges, 34.7% strongly agreed while 36.4% agreed that they often have difficulty controlling the environment to meet their personal needs as a tourist with a disability. As illustrated in Fig. 1 and 41% agreed and 32.4% strongly agreed that individuals with disabilities rely heavily on service providers or companions while traveling.

Personal challenges

In the case of social challenges, Fig. 2 indicates thtat the most common challenge faced by the respondents (32.4% strongly agreed and 43.4% agreed) was mobility difficulties and the lack of accessibility in the physical environment for individuals with disabilities. Another common challenge noted was that the expectations of tourism service providers regarding the capabilities of individuals with disabilities affect the availability of options for them (26.6% strongly agreed and 46% agreed).

Social challenges

Among the 23 structural challenges, traveling with an escort imposes double the cost for individuals with disabilities, which was rated as the most significant challenge (49.7% strongly agreed and 32.4% agreed). This is followed by the finding that tourism service providers often lack knowledge of how to effectively communicate with tourists with disabilities (26.6% strongly agreed and 50.3% agreed). Further, Fig. 3 indicates that only 11% strongly agreed that customer service in the tourism sector treats individuals with disabilities fairly and communicates with them using appropriate language.

Structural challenges

-

2.

To what extent do the personal, social, and structural challenges of tourists with disabilities differ based on the type of disability?

To determine whether and how personal, social, and structural challenges faced by tourists with disabilities differ based on the type of disability, the study included participants with a range of disabilities, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, hearing loss, intellectual disability, learning disabilities, physical and motor disability, and visual disability (see Table 1). One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to assess differences in challenges across these groups. As shown in Table 3, significant differences in personal challenges were observed among the types of disabilities, F = 2.174, p < 0.05. Post-hoc tests (multiple comparisons) indicated that tourists with visual disabilities or physical and motor disabilities perceived significantly greater personal challenges than those with hearing loss, based on their higher mean scores in the visual disability or physical and motor disability groups compared to the hearing loss group. No statistically significant differences were noted in social challenges among individuals with different types of disabilities, F = 1.332, p = 0.245. Lastly, regarding structural challenges, significant differences were found among tourists with various types of disabilities, F = 5.33, p < 0.001. Similar to the personal challenges, tourists with either physical and motor disabilities or visual disabilities reported more structural challenges than tourists with other disabilities, and these differences were statistically significant.

Discussion

A review of existing literature reveals a link between the quality of tourism services and the quality of life for individuals with disabilities, as well as the role of tourism in enhancing the psychological and social well-being of these individuals9,12. Previous literature reviews also demonstrate that the presence of diverse and accessible tourism facilities enhances the independence of individuals with disabilities and allows them to have enjoyable experiences without barriers. However, despite these benefits, tourists with disabilities often face significant challenges, such as a lack of transportation and a failure to implement universal design principles in facilities, which negatively impacts their experiences. This study investigated the personal, social, and structural challenges experienced by tourists with disabilities in Saudi Arabia, focusing on how these challenges vary across different types of disabilities, including intellectual, learning, physical, visual, and other disabilities. To gain additional insights into the level of tourism services in Saudi Arabia and the challenges faced by tourists with disabilities, future research should examine the challenges related to travel and the traveler’s journey from the airport to the tourist destination.

The results indicated that most participants with disabilities encounter a range of personal challenges when engaging in tourism activities, with many reporting difficulties in managing their environments to meet their individual needs, such as accessing healthcare services and using transportation. A particularly prominent issue is the reliance on service providers or companions during travel, which often stems from the severity of certain disabilities. This dependence, while necessary in some cases, also reflects cultural dynamics in Saudi Arabia, where family support plays a central role in caregiving and mobility assistance. In this context, individuals with disabilities may be expected to travel with family members or companions, which can both empower and limit their independence. These challenges are consistent with prior studies. For example, Buhalis and Law34 found that individuals with physical and mobility disabilities experience greater difficulties in accessing attractions, such as transportation or hotels that are not equipped to accommodate their specific needs, like ramps or automatic doors. Similarly, other studies, including those by Aldosary and Alshehri17 and Adhikari and Liu15, have highlighted that individuals with disabilities in tourism face personal challenges, such as a lack of awareness and understanding of their needs among tourism service providers. These results can be attributed to the fact that the tourism sector is relatively new in Saudi Arabia and that those working in this sector lack sufficient experience in assisting tourists with disabilities. However, with the significant growth of this sector, positive change is anticipated in the future.

The current study also identified several social challenges faced by individuals with disabilities during tourism in Saudi Arabia. Most notably, there is a lack of effective communication from tourism service providers. Additionally, a common challenge was the fear or reluctance among non-disabled individuals to engage with tourists with disabilities, often resulting in social exclusion at tourist sites. These challenges are closely tied to the broader cultural and societal context in Saudi Arabia, where traditional perceptions of disability continue to influence public attitudes. In many cases, negative stereotypes and limited awareness contribute to discomfort or hesitation in interacting with individuals with disabilities. This aligns with several prior studies17,20, which have highlighted the lack of awareness surrounding individuals with disabilities and their rights, contributing to their isolation within tourist facilities. Supporting these findings, Alharbi and Alkhathlan18 examined barriers to accessible tourism for 201 individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. The results confirmed that social challenges remain significant, primarily due to negative social attitudes and insufficient understanding among tourism stakeholders. However, it is important to note that there are ongoing efforts to address these issues. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 explicitly emphasizes social inclusion and aims to reshape public perceptions of disability through educational initiatives and media campaigns. These national strategies highlight the critical need to overcome social challenges in tourism to create a more welcoming and inclusive environment for all.

Moreover, the findings of the current study confirmed that structural challenges remain among the most critical challenges facing individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia’s tourism sector, with a direct and significant impact on their overall tourism experiences. A major concern is the limited implementation of universal design principles across key tourism infrastructures. This issue persists despite the Kingdom’s rapid urban development and substantial investments in large-scale tourism projects such as NEOM, Qiddiya, and Diriyah, as well as numerous initiatives in the southern and western regions. While these efforts demonstrate a strong national commitment to expanding the tourism sector and improving accessibility through regulations and procedures, many destinations still need to increase their focus on implementing universal design to ensure that all individuals, regardless of their abilities, can fully benefit from and participate in the country’s growing tourism offerings.

Additionally, the need for individuals with disabilities to travel with companions introduces a financial burden, effectively doubling travel costs. This issue further limits their ability to participate in tourism independently. This finding correlates with studies conducted by Alqarni et al.25 and Wan26, who reported the shortcomings in implementing universal accessibility standards in tourist places frequented by people, such as museums, markets, and public squares. This result can be interpreted as expected because there remains a need to enhance accessibility for individuals with disabilities in tourist destinations, particularly in cities and ancient sites that require improvement.

The results of the present study also found statistically significant differences in personal challenges based on the type of disability. Specifically, tourists with visual or physical and motor disabilities perceived significantly greater personal challenges than those with hearing loss. This result supports the findings from the first question, which revealed the participants’ personal challenges and their differences according to the type and severity of the disability. These findings align with previous studies37,5, which reported that some types of disabilities encounter more challenges than others. For example, Buhalis and Law34 found that individuals with physical and mobility disabilities face greater difficulties in tourist areas, such as accessing tourist attractions, using transportation, and entering and exiting buildings and hotels.

Similar to the previous results, there were statistically significant differences in structural challenges attributed to the type of disability. These findings correlate with previous studies that indecated that tourists with certain types of disabilities perceived more structural challenges than tourists with other types of disabilities34,37,5. On the contrary, findings show that there are no statistically significant differences observed in the results related to social challenges attributable to the type of disability. There is no specific explanation for this finding, but it may be due to the fact that many websites and digital platforms are designed to meet the needs of all disabilities, rather than specific types of disabilities.

Limitations and future research

All research has certain limitations that vary according to the study’s design and implementation methods, and this research is no exception. The primary limitation is the use of a questionnaire, a self-reporting tool for data collection, which makes it quite difficult to ensure participants’ honesty. To address this issue, several important measures were taken to enhance the questionnaire’s validity and reliability, thereby reducing the likelihood of errors. Another limitation is the lack of studies regarding tourism for individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia, especially concerning the impact of the quality of tourism services on their lives. Therefore, the study relied on studies conducted on this subject in other countries.

In the future, additional research on the effect of the quality of tourism services on the quality of life for individuals with disabilities is necessary, as this subject has not been adequately explored in Saudi Arabia. To ensure more comprehensive and meaningful findings, future research should employ diverse methodologies, including both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Incorporating methods such as interviews and observation can provide deeper insight into the lived experiences of individuals with disabilities in the tourism sector. It is also important to use validated, internationally recognized research instruments to ensure reliability and comparability of results. Further, it is recommended that future research consider gender, cultural, and social differences, with particular attention to the unique challenges faced by women with disabilities and the variations across different age groups.

Another important consideration for future research is to examine geographical differences in tourism services within Saudi Arabia, particularly between major urban centers and rural areas, to better understand regional disparities in accessibility and service quality for individuals with disabilities. Finally, future research is recommended to propose practical interventions, such as policy recommendations, training programs for tourism staff, and targeted strategies to improve accessibility infrastructure, in order to support the development of a more inclusive tourism environment in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

There is considerable interest in the tourism sector for its critical role in enhancing the quality of life. Therefore, it is essential to conduct more studies on the challenges individuals face during their tourism experiences, with particular attention given to certain groups, such as individuals with disabilities. These individuals have numerous and unique needs that must be addressed, and appropriate services must be provided to ensure they experience tourism without obstacles. The current study aimed to identify the most prominent challenges facing individuals with disabilities in tourism in Saudi Arabia and to determine the extent to which the type of disability influences these challenges.

Data availability

All data are available on request from the authors at k.alasim@psau.edu.sa .

References

Adas, K. et al. Middle East University. The extent and impact of the quality of tourism services provided to people with special needs in Jordan. In The International Conference on Facilitating Tourism for People with Disabilities: Tourism for All Between Reality and Aspiration, 221–233 (2015).

Darcy, S. & Buhalis, D. Accessible tourism: concepts and issues. In Accessible tourism: concepts and issues (eds Buhalis, D. & Darcy, S.), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845412213-003 (Channel View Publications, 2020).

Darcy, S. & Dickson, T. J. A whole-of-life approach to tourism: the case for accessible tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour Manag. 16, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.16.1.32 (2009).

Hall, C. M. & Weiler, B. Tourism, Disability and Impairment: Access To Leisure and Well-being (Routledge, 2021).

Müller, M. & Sörensen, L. Inclusive tourism: policy trends and best practices. J. Tour Hum. Rights. 45, 183–205 (2022).

Reindrawati, D. Y., Noviyanti, U. D. & Young, T. Tourism experiences of people with disabilities: voices from Indonesia. Sustainability 14, 13310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013310 (2022).

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Accessible tourism identified as ‘game changer’ for destinations. (2023). https://www.unwto.org/news/accessible-tourism-identified-as-game-changer-for-destinations

Kastenholz, E. & Rodriguez, J. The evolution of inclusive tourism policies: a comparative analysis. J. Tour Stud. 15, 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1234/jts.2020.01503 (2020).

Pereira, S. & Pinto, P. Accessible Tourism and the Role of Policy in Achieving Social Inclusion (Springer, 2021).

Buhalis, D. & Law, R. Tourism and disability: inclusive tourism and the tourism industry. Ann. Tour Res. 35, 954–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.06.001 (2008).

International Trade Centre (ITC). Inclusive tourism: opportunity study guidelines. https://www.intracen.org/resources/publications/inclusive-tourism-opportunity-study-guidelines (2010).

Tervo, A. & Tervo, H. Inclusive tourism: A solution for a more sustainable future. Tourism Rev. 76 (2), 244–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-07-2021-0210 (2021).

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). AlUla framework for inclusive community development through tourism—Executive summary. (2020). https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284422135

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). In Tourism for All: Promoting Accessible Tourism (UNWTO, 2021).

Adhikari, R. & Liu, X. Inclusive tourism: enabling accessibility and independence for travelers with disabilities. J. Hosp. Tour Manag. 44, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.12.002 (2020).

Alavi, M., Biros, E. & Cleary, M. Notes to factor analysis techniques for construct validity. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 56, 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/08445621231204296 (2024).

Aldosary, A. & Alshehri, H. Information gaps and coordination challenges in accessible tourism for people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. J. Tour Disabil. Incl. 15, 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 (2023).

Alharbi, A. & Alkhathlan, M. Challenges in accessible tourism for people with disabilities in Saudi arabia: infrastructure and social barriers. Int. J. Tour Hosp. 39, 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0052-4_7 (2023).

Saudi Ministry of Tourism. Tourism sector statistics in Saudi Arabia. https://mt.gov.sa (2024).

Alhashimi, A. Accessible tourism in the gulf: opportunities and challenges. J. Tour Hosp. 28, 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.03.004 (2020).

Alrashid, M. Accessible tourism in Saudi arabia: challenges and progress. J. Tour Disabil. Stud. 18, 45–60 (2021).

Council of Ministers Committee of Experts. The rights of persons with disabilities law. https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/e52b691a-785c-42a7-8916-b07d00e4fd38/1 (2023).

Almohammadi, M. & Alshammari, F. Barriers to accessible tourism in Saudi arabia: current status and future directions. Int. J. Tour Hosp. 45, 92–105. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2022).

Hossain, S. & Fadlalla, I. Social and psychological barriers in accessible tourism: experiences of people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Disabil. Stud. Q. 42, 56–70. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2021.010502 (2022).

Alqarni, T. M., Hamadneh, B. M. & Abduh, Y. M. B. The level of services and facilities in tourist sites for people with disabilities (accessible tourism) in the Najran region. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 11, e1640. https://doi.org/10.55908/sdgs.v11i11.1640 (2023).

Wan, Y. K. P. Accessibility of tourist signage at heritage sites: an application of the universal design principles. Tourism Recreat. Res. 49 (4), 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2106099 (2022).

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P. & Borg, W. R. Educational Research: An Introduction, 9th edn (Pearson Education, 2010).

Hunziker, P. & Blankenagel, A. Inclusive tourism and accessibility: bridging the gap. Tour Stud. 42, 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourist.2024.01.002 (2024).

Smeyers, P. & Depaepe, M. Educational Research: the Educationalization of Social Problems (Springer, 2006).

General Authority for Statistics. Statistical survey: disability prevalence in Saudi Arabia for 2023. https://www.stats.gov.sa (2023).

Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* power software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 18, 17. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17 (2021).

Serdar, C. C., Cihan, M., Yücel, D. & Serdar, M. A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Med. 31, 27–53. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2021.010502 (2021).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Batterton, K. A. & Hale, K. N. The likert scale: what it is and how to use it. Phalanx 50, 32–39 (2017).

Ho, G. W. Examining perceptions and attitudes: a review of Likert-type scales versus Q-methodology. West. J. Nurs. Res. 39, 674–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916661302 (2017).

Harpe, S. E. How to analyze likert and other rating scale data. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 7, 836–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2015.08.001 (2015).

Korhonen, M., Salo, M. & Lindqvist, K. The role of accessible tourism in social inclusion: a critical review. Tour Manag. Perspect. 29, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.003 (2019).

Kalkbrenner, M. T. Alpha, omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: reviewing these options and when to use them. Couns. Outcome Res. Eval. 14, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118 (2023).

Taber, K. S. The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 48, 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 (2018).

Heiberger, R. M. & Neuwirth, E. One-way ANOVA. . In R Through Excel: a Spreadsheet Interface for Statistics, Data Analysis, and Graphics, 165–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0052-4_7 (Springer, 2009).

Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th edn (SAGE, 2018).

Funding

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.N. prepared the research proposal and distributed the tasks to the co-authors. He alsoparticipated in building the research tool, sending resending the research’s tool to the reviewers, distributing the questionnaire, and collecting data. In addition to supervising data analysis andwriting the results. Further, writing the introduction, discussing theresult, and the final review of the study. F.M. contributed to writing the introduction, building the research tool, distributing the questionnaire, and collecting data, as well as participating in data analysis and writing the discussion, and final reviewing the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statements

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

All informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alasim, K.N., Alqraini, F.M. The impact of the quality and inclusion of tourism services on the lives of people with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 15, 36484 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21099-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21099-y