Abstract

Light field angular super-resolution (LFASR) aims to reconstruct densely sampled angular views from sparsely captured inputs, enabling high-fidelity rendering, refocusing, and depth estimation. In this paper, we propose a novel LFASR framework that employs a tri-visualization feature extraction strategy, which jointly processes Sub-Aperture Images (SAIs), Epipolar Plane Images (EPIs), and Macro-Pixel Images (MacroPIs) to comprehensively exploit the spatial-angular structure of light fields. These complementary representations are processed in parallel to extract diverse and informative features, which are then refined through a deep spatial aggregation module composed of residual blocks. The proposed pipeline consists of three key stages: Early Feature Extraction (EFE), Advanced Feature Refinement (AFR), and Angular Super-Resolution (ASR). Extensive experiments on both synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrate that our method achieves strong performance in terms of PSNR and SSIM, while maintaining strong generalization and robustness in challenging scenarios, including occlusions and large disparity variations. Moreover, qualitative evaluations confirm the method’s ability to preserve epipolar consistency and structural integrity across synthesized views, making it a reliable and efficient solution for practical LFASR applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light field (LF) captures a comprehensive representation of a scene by recording both spatial and angular information of light rays across multiple viewpoints sampled uniformly on a plane1,2,3. This dual-dimensional capture enables numerous advanced applications, such as post-capture refocusing4, disparity estimation5,6, foreground de-occlusion7, virtual reality8, 3D reconstruction9, and object segmentation10. However, achieving densely sampled LFs, which are essential for these applications, remains a significant challenge. Current LF acquisition technologies face notable limitations. For example, camera arrays11 provide high sampling density but are often bulky and expensive. Similarly, time-sequential12 methods are restricted to static scenes, and plenoptic cameras13,14 inherently trade-off between spatial and angular resolution.

To address the limitations of LF acquisition, researchers have increasingly adopted computational approaches for LF reconstruction. These techniques aim to synthesize high-resolution LFs from sparsely sampled inputs, thereby minimizing the need for specialized hardware. In particular, spatial super-resolution (SSR) methods15,16,17,18 enhance the resolution of each sub-aperture image while keeping the original angular resolution unchanged. In contrast, angular super-resolution (ASR) methods19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 focus on reconstructing densely sampled angular views from sparsely captured LFs (e.g., from \(2 \times 2\) to \(7 \times 7\)). Together, SSR and ASR form a complementary set of solutions that address the resolution limitations in both spatial and angular domains, effectively bridging the gap between practical LF acquisition and application requirements.

Within LFASR, two primary paradigms dominate: explicit depth-based and implicit depth-based approaches. Explicit methods first estimate disparity maps, which describe pixel-wise correspondences between different viewpoints, and then warp input views according to these disparities to generate new perspectives. This explicit modeling of geometry provides strong guidance in regions with significant depth variation, enabling accurate view synthesis when disparity is reliable. However, their performance is highly sensitive to the quality of disparity estimation. In textureless areas, around occlusion boundaries, or under non-Lambertian surfaces, disparity predictions often become inaccurate, leading to ghosting, tearing, or blurred structures in the reconstructed views.

In contrast, implicit depth-based methods bypass explicit disparity estimation altogether. Instead, they adopt a data-driven strategy, directly learning mappings from sparse input views to dense angular reconstructions. By jointly encoding spatial and angular features, these models can infer correspondences without explicit geometric supervision, which reduces sensitivity to disparity errors and allows finer preservation of textures. Nevertheless, the absence of explicit geometric constraints makes these methods less effective under wide baselines or large disparity ranges, where angular coherence and structural consistency are difficult to maintain, often resulting in view misalignment or distortions.

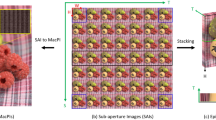

The four-dimensional LF structure provides multiple complementary visualization formats (Fig. 1), each highlighting distinct aspects of spatial–angular correlation. Sub-aperture images (SAIs) represent spatial views sampled from different angular positions, offering detailed but view-dependent representations. Epipolar-plane images (EPIs) capture intensity variations along angular slices, forming linear patterns whose slopes encode disparity, making EPIs particularly effective for depth-sensitive modeling. Macro-pixel images (MacPIs) reorganize the LF into compact, grid-like structures where angular variations are embedded into spatial layouts, facilitating efficient processing with convolutional operators while preserving angular relationships. These representations are inherently complementary: SAIs preserve fine spatial details, EPIs provide structured disparity cues, and MacPIs enable efficient integration of angular correlations. Leveraging them jointly promises a more holistic modeling of LF structure than any single representation alone.

However, existing LFASR methods typically do not utilize all available LF visualizations, which limits their ability to fully capture the LF’s geometric richness. For instance, Wang et al.33 employ only MacPIs, disentangling angular and epipolar cues through dedicated convolutional kernels combined with downsampling and pixel shuffling. While this disentangling is effective, the downsampling operations inevitably discard details, constraining the fidelity of reconstruction. Similarly, Liu et al.34 emphasize multiscale correlations within SAIs but do not exploit the complementary disparity cues embedded in EPIs or the structural compactness of MacPIs. These design choices highlight a broader limitation: single-representation methods struggle to balance detail preservation, geometric awareness, and angular coherence simultaneously.

To address these shortcomings, we propose a unified LFASR framework that integrates SAIs, EPIs, and MacPIs in a complementary manner. Rather than disentangling and processing them in isolation, our method directly extracts spatial, angular, and epipolar information from all three representations and fuses them using a dedicated Spatial_Group module, which enhances and refines spatial detail. This joint design preserves more information, strengthens geometric modeling, and significantly improves reconstruction fidelity compared to single-visualization or disentangling-based approaches. Furthermore, our network incorporates large receptive fields to capture long-range dependencies and a hierarchical refinement strategy with cascaded blocks, enabling robust performance in challenging conditions such as large disparities, occlusions, and reflective surfaces. The key contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

1) We propose a novel Tri-Visualization Feature Extraction Block (TVFEB) that explicitly integrates three complementary LF representations–SAIs, EPIs, and MacPIs– enabling comprehensive modeling of spatial-angular correlations and disparity cues. This unified design enables comprehensive exploitation of LF structure from multiple perspectives, enhancing robustness against disparity and occlusion variations.

2) Our network employs a hierarchical refinement strategy where multiple TVFEB modules are cascaded to progressively enhance feature quality. This multi-stage processing captures long-range interactions across views and reinforces fine-grained geometric details, improving the reconstruction of complex scenes with large disparities.

3) The proposed method demonstrates consistently strong performance across multiple datasets, as evidenced by the conducted experiments. It achieves robust quantitative results while effectively preserving epipolar consistency and structural integrity across synthesized views. These outcomes are validated on both synthetic and real-world LF datasets, highlighting the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Related work

Reconstructing densely sampled LFs from a sparse set of input views has been extensively studied. Existing solutions are generally categorized into depth-based and non-depth-based methods. These methods differ fundamentally in their strategies for handling the angular and spatial correlations inherent in LFs.

Depth-based LF reconstruction

Depth-based approaches utilize disparity information to synthesize novel views, leveraging explicit correspondence modeling between different angular views. For instance, Wanner et al.19 analyzed 4D LF reconstruction by estimating disparity maps using EPIs and synthesizing novel views through disparity-based warping. Zhang et al.20 proposed a phase-based technique that synthesizes LFs from micro-baseline stereo pairs using disparity-assisted phase synthesis, although it is prone to artifacts in occluded regions. Extending patch-based synthesis, Zhang et al.21 modeled LF views as overlapping depth layers to capture varying depth structures effectively.

Recent advancements in deep learning have refined this paradigm. Depth-based neural networks typically consist of two sub-networks: one for depth estimation and another for view refinement. The process can be summarized as follows:

1) Depth Estimation:

Here, \(D(x,u)\) denotes the depth map at spatial location \(x\) and angular position \(u\), estimated from input views \(L(x,u')\) via the depth estimation network \(f_d\).

2) Disparity-Based Warping:

The novel view \(W(x,u,u')\) is synthesized by warping input views \(L(x,u')\) based on the estimated disparity.

3) View Refinement:

Final reconstruction \(\hat{L}(x,u)\) combines the warped view and a refined version produced by the refinement network \(f_r\). Kalantari et al.22 introduced a disparity-driven neural framework for LF reconstruction, combining disparity and color estimation for synthesizing high-quality views. However, this method suffers in occluded and textureless regions due to challenges in disparity estimation. Choi et al.23 proposed a method for synthesizing extreme angular views by combining depth-guided warping and refinement, using depth information to map input views to novel positions. Jin et al.24 enhanced this approach with a depth estimator featuring a large receptive field, effectively addressing challenges posed by large disparities. Later, Jin et al.25 introduced a coarse-to-fine strategy, first generating coarse SAIs and then refining them with an efficient LF refinement module. Their method utilized plane-sweep volumes (PSVs) built on predefined disparity ranges for improved depth estimation. Liu et al.37 proposed a geometry-assisted multi-representation network that synthesizes dense LF stacks from lenslet images, SAIs, and pseudo video sequences, followed by a geometry-aware refinement module to exploit spatial-angular and geometric cues. Chen et al.38 proposed a Multiplane-based Cross-view Interaction Mechanism (MCIM) with Multiplane Feature Fusion and a Cross-Shaped Transformer (CSTNet), enabling efficient cross-view interaction and improved robustness to scene geometry.

Despite their strengths in handling large disparities, depth-based methods remain vulnerable to inaccuracies in disparity maps. These errors often manifest as ghosting, geometric distortions, and photometric inconsistencies–particularly in occluded or homogeneous regions where depth estimation is inherently ambiguous.

Non-depth-based LF reconstruction

Non-depth-based methods bypass explicit disparity estimation, instead focusing on direct modeling of the angular-spatial correlations in LFs. Early techniques often employed traditional optimization frameworks. For instance, Mitra et al.26 proposed a patch-based synthesis technique using a Gaussian Mixture Model to represent LF patches. Shi et al.27 leveraged LF sparsity in the Fourier domain, while Vagharshakyan et al.28 applied shearlet transforms to reconstruct semi-transparent scenes iteratively.

With the rise of deep learning, CNN-based frameworks have become the dominant paradigm for non-depth-based LF reconstruction. These models typically learn a mapping from sparse views to novel angular views using a unified network:

where \(\hat{L}(x, u)\) denotes the synthesized view at spatial position x and angular position u, \(L(x, u')\) represents the input views, and \(\theta\) are the learnable parameters of the network f. Several notable CNN-based methods have been proposed. Yoon et al.29 introduced a deep network for generating novel views from two adjacent input views. Zhu et al.30 integrated CNN and LSTM modules to enhance both spatial and angular dimensions. Wu et al.31 tackled spatial-angular asymmetry using a blur-restoration-deblur approach in the EPI domain, though its performance is limited under significant disparity variations. A later improvement merged sheared EPIs for better angular synthesis32.

Wang et al.33 disentangled spatial, angular, and epipolar information for LF reconstruction, while Liu et al.34 proposed a spatial-angular feature extraction strategy with MacPI-based upsampling. Salem et al.35 proposed a dual feature extraction approach for LF reconstruction, effectively processing horizontal and vertical epipolar data during both the initial and deep feature extraction stages. Elkady et al.36 developed a model that extracts quadrilateral epipolar features from multiple directions, building a robust feature hierarchy for accurate LF reconstruction. Li et al.39 proposed a reconstruction framework based on the Epipolar Focus Spectrum (EFS), which decomposes the input LF into sparse, sheared, and occlusion components. This decomposition enhances reconstruction stability and accuracy, particularly in scenes with large disparity variations and intricate structural details. In a related effort, Liu et al.40 developed a hybrid architecture combining convolutional and Transformer modules with an integrated deblurring mechanism. Their approach jointly models geometric and textural features, resulting in sharper and more detailed reconstructions. Wang et al.41 proposed ViewFormer, a Transformer-based LFASR framework that uses view-specific queries to encode content and spatial coordinates. It leverages a Transformer encoder-decoder and view interpolation to enhance features dynamically based on angular positions.

Non-depth-based approaches avoid errors associated with disparity estimation, enabling better handling of occlusions and low-texture regions. However, they face challenges when dealing with large disparities in LFs, such as issues with view alignment, angular coherence, and maintaining image quality across varying depths. To address these limitations, hybrid reconstruction strategies have gained attention. A prominent example is the work of Chen et al.42, who proposed a disparity-guided hybrid framework that adaptively integrates depth-based and non-depth-based methods. Their approach applies non-depth-based reconstruction in regions with low disparity, while employing depth-based techniques in high-disparity areas. This adaptive mechanism capitalizes on the complementary strengths of both paradigms, enabling more accurate and context-aware super-resolution across varying disparity conditions. Similarly, Wu et al.43 introduced the Geometry-aware Neural Interpolation (Geo-NI) framework, which combines Neural Interpolation with Depth Image-Based Rendering by leveraging cost volumes across depth hypotheses, enabling robust LF rendering under large disparities and non-Lambertian effects.

Recent works aim to enhance both spatial resolution and angular sampling rates of LF images. Liu et al.44 proposed an adaptive pixel aggregation method that synthesizes high-resolution LF images by leveraging spatial-angular correlations and refining features through a feature separation and interaction module. Wang et al.45 introduced the 4D efficient pixel-frequency transformer (4DEPFT), which models 4D correlations in pixel and frequency domains using inner-outer transformers with 4D position encoding. This approach reduces computational costs while delivering superior performance compared to existing method.

In light of these challenges, our work advocates a fully learning-based non-depth framework that capitalizes on the complementary strengths of various LF representations (e.g., SAIs, EPIs, and MacPIs). By explicitly designing modules to process these visualizations, our model achieves high-quality reconstructions with improved angular consistency and reduced aliasing–without the need for disparity estimation.

Methodology

Problem formulation

LF can be modeled as a 4D function \(L(u, v, x, y) \in \mathbb {R}^{ S \times T \times H \times W }\), where \(S \times T\) defines the angular resolution (number of sub-aperture views), and \(H \times W\) represents the spatial resolution (pixel dimensions of each view). This formulation captures both angular and spatial details, enabling the reconstruction of diverse perspectives and representing depth and parallax effects. Given a low-angular-resolution LF image, denoted \(I_{\text {LR}} \in \mathbb {R}^{S \times T \times H \times W}\), comprises \(S \times T\) sparsely sampled SAIs. The goal is to reconstruct a high-angular-resolution LF image \(I_{\text {HR}} \in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha S \times \alpha T \times H \times W}\), where \(\alpha> 1\) is the angular scale factor. This process synthesizes \((\alpha S \times \alpha T - S \times T)\) novel views to increase angular density, improving the representation of LF for improved realism and accurate rendering. In this work, we transformed the LF images from RGB to the YCbCr color space. Reconstruction operates on the luminance channel (Y) in the YCbCr color space, as it carries most of the structural information. The Chrominance channels (Cb, Cr) are upsampled by bicubic interpolation and combined with the reconstructed Y channel to form the final \(I_{\text {HR}}\). This method balances computational efficiency with visual fidelity by preserving texture and color consistency. Furthermore, we investigate the sensitivity of reconstruction performance to the angular scale factor \(\alpha\). In particular, we evaluate two challenging cases: (i) \(\alpha =3.5\), corresponding to reconstructing a \(7\times 7\) LF from a \(2\times 2\) input, and (ii) \(\alpha =4\), corresponding to reconstructing an \(8\times 8\) LF from a \(2\times 2\) input. These scenarios provide insight into the robustness of the proposed method under significant angular upscaling, where larger scaling factors significantly increase reconstruction difficulty. The corresponding results are reported in the Experiments section.

Overview of network architecture

The architecture of the proposed network, illustrated in Fig. 2, is centered around a novel module termed the Tri-Visualization Feature Extraction Block (TVFEB). This block is designed to extract complementary spatial-angular features from three distinct LF representations: MacPIs, EPIs, and SAIs. The overall framework is divided into three main stages: Early Feature Extraction (EFE), Advanced Feature Refinement (AFR), and Angular Super-Resolution (ASR).

The EFE stage employs a single TVFEB to extract rich high-dimensional features from the input LF image \(I_{\text {LR}}\). By jointly processing the SAI, EPI, and MacPI representations, this stage captures both local structural patterns and geometric relationships across views. The output is a unified feature representation denoted as \(F_{\text {EFE}} \in \mathbb {R}^{ S \times T \times C \times H \times W }\), where C denotes the number of feature channels. The operation is formally defined as:

The AFR stage further improves the quality of feature representations through a hierarchical refinement strategy composed of three cascaded TVFEBs, collectively referred to as the TVFE_Group. In this stage, each block in the group deepens and enriches the features by progressively refining them across spatial, epipolar, and angular dimensions. To preserve and reinforce previously learned information, a skip connection is introduced between the input of the TVFE_Group and the output of the final TVFEB within the group. These features are concatenated and passed through a \(1\times 1\) convolution as a fusion operation to produce the refined output, denoted as \(F_{\text {AFR}} \in \mathbb {R}^{ST \times C \times H \times W }\). The process is formally described by:

This refinement strategy enables the network to capture long-range dependencies and strengthens its ability to model complex spatial and angular interactions. Consequently, the network becomes more robust in reconstructing LFs with significant geometric complexity and large disparity variations.

The ASR stage performs angular upsampling by applying a PixelShuffle operation to the MacPI-based features. This operation rearranges and enlarges the angular dimensions, generating the high-angular-resolution feature volume \(F_{\text {HR}} \in \mathbb {R}^{\alpha S \times \alpha T \times H \times W}\), where \(\alpha\) denotes the angular scale factor. This step enables the synthesis of novel viewpoints and enhances angular fidelity. The process is formally described by:

To ensure consistency and stability in the reconstruction process, a global residual connection is applied. This combine the upsampled prediction with bicubic interpolation of the input LF, resulting in the final high-resolution output \(I_{\text {HR}}\). This design enhances angular resolution while maintaining the structural integrity of epipolar geometry and spatial details.it can be represented as follows:

The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of each module within the network, explaining how the proposed architecture effectively addresses the challenges of LFASR.

Tri-visualization feature extraction block (TVFEB)

To comprehensively exploit the diverse structural cues inherent in LF data, we introduce the TVFEB. This module simultaneously processes three complementary LF visualizations-MacPIs, EPIs, and SAIs–to extract rich spatial and angular features. As illustrated in Fig. 2, these three visualizations are processed in parallel, then aggregated and refined through a dedicated spatial enhancement module, denoted as Spatial_Group.

The processing pipeline begins by transforming the input low-angular-resolution LF image (\(I_{\text {LR}}\)) into its corresponding MacPI, EPI, and SAI forms. Each visualization is independently processed by a dedicated module designed to extract relevant structural features. In the MacPI branch, spatial and angular features are captured through two parallel convolutional paths. The spatial path comprises two \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers with stride 1, and dilation/padding equal to the input angular resolution (e.g., 2), separated by a Leaky ReLU activation with a negative slope of 0.1. The angular path includes two \(2 \times 2\) convolutions with stride 1, dilation 5, and asymmetric padding of (3,2), also interleaved with a Leaky ReLU. The outputs of both paths are summed to produce the final MacPI feature maps, denoted as \(F_{\text {MacPI}}\):

For the EPI branch, horizontal and vertical EPIs are generated by stacking SAIs along the respective angular dimensions. These EPIs are processed using a shared feature extractor composed of two \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers with stride 1 and padding 1. A Leaky ReLU activation (slope 0.1) separates the layers. The resulting horizontal and vertical features are summed to produce the final EPI feature maps, denoted as \(F_{\text {EPI}}\):

In the SAI branch, each sub-aperture view is individually processed through two \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layers (stride 1, no padding) separated by a Leaky ReLU activation to construct the SAI feature maps, denoted as \(F_{\text {SAI}}\):

This configuration enables localized feature extraction with minimal spatial distortion. The outputs of the three branches, which share the same dimensions \(\in \mathbb {R}^{ S \times T \times C \times H \times W}\), are merged via element-wise addition and subsequently transformed into MacPIs visualization and passed to the spatial_Group module for refinement. This module comprises a sequence of spatial residual blocks (SPA_Res_Blocks) designed to enhance spatial geometry and texture encoding. Each SPA_Res_Block begins with a \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layer, followed by eight additional \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers interleaved with Leaky ReLU activations (slope = 0.1), and concludes with a final \(3 \times 3\) convolution. A skip connection is applied between the output of the first and before the last convolutional layer to preserve low-level features and stabilize training. Outputs from all SPA_Res_Blocks are concatenated and fused using two final \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers.this can be represented as:

This design enables TVFEB to effectively extract and integrate rich structural information across three LF representations. The parallel processing strategy, followed by spatial refinement, enhances network’s capacity to model complex geometric structures and long-range dependencies critical for high-quality LFASR.

Angular Super-Resolution (ASR)

The ASR stage aims to enhance the angular resolution of the intermediate feature representation \(F_{\text {AFR}}\), which is first organized into the MacPI format. This is accomplished through a downsampling-then-upsampling strategy tailored for efficient angular view synthesis. Initially, a \(2 \times 2\) convolutional layer with stride 2 and no padding is applied to \(F_{\text {AFR}}\), effectively reducing its angular resolution while preserving essential structural information. This operation is followed by a Leaky ReLU activation function with a negative slope of 0.1, promoting non-linearity and enhances representational capacity.

Subsequently, a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer is employed to increase the channel dimensionality of the downsampled feature maps. This step facilitates richer feature representation and prepares the data for the upsampling stage. To perform angular upsampling, a pixel shuffle operation is utilized to reorganize the feature maps into higher angular resolution, effectively synthesizing the missing SAIs. To mitigate the spatial distortion that may result from the pixel shuffle operation, the upsampled features are further refined using a \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layer followed by a Leaky ReLU activation. This refinement enhances local consistency and ensures that the reconstructed angular views maintain both spatial coherence and geometric integrity. Finally, a fusion operation is performed using a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer to reduce the feature channel dimension to one,, yielding the reconstructed high-angular-resolution LF feature maps \((F_{\text {HR}})\).

Experiments

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed model against existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, highlighting its strengths and effectiveness in LFASR. We also conduct ablation studies to assess the impact of specific design choices on performance and explore the potential of our model for depth estimation task.

Datasets and implementation details

To ensure thorough validation, we evaluated our model on both synthetic and real-world LF datasets. For synthetic benchmarks, we employed the HCInew46 and HCIold47 datasets, which contain LFs with large baselines and high disparity variations. For real-world evaluation, we used the 30Scenes22 and STFlytro48 datasets, which capture natural textures and illumination conditions. Following established protocols33,36, our training set consisted of 120 scenes (100 real-world and 20 synthetic), while the test set included 5 scenes from HCIold, 4 from HCInew, 30 from 30Scenes, and 40 from STFlytro. The STFlytro dataset was further subdivided into 25 occlusion-heavy and 15 reflective scenes to assess robustness under challenging conditions. Table 1 summarizes the training and test splits.

Synthetic datasets provided controlled settings with large disparity ranges and rich textures, as shown in Table 1. They are ideal for evaluating the model’s capacity to reconstruct angular detail under geometric complexity. Texture complexity was quantified using the texture contrast metric, computed via the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix49. Real-world datasets, although featuring smaller disparities, presented naturally occurring textures and optical distortions–key challenges for practical deployment.

Our evaluation focused on the standard \(2\times 2 \rightarrow 7\times 7\) ASR task. The objective was to reconstruct a \(7\times 7\) array of SAIs from only the four corner views. Each SAI was cropped into \(64\times 64\) patches during training, generating approximately 15,000 samples. Data augmentation techniques including random 90-degree rotations and horizontal/vertical flipping were applied to improve model generalization.

Training was conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. We used Adam optimizer50 with parameters \(\beta _1 = 0.9\), \(\beta _2 = 0.999\), a batch size of 4, and an initial learning rate of \(2 \times 10^{-4}\), halved every 25 epochs. The model was trained for 80 epochs. The objective function was the \(L_1\) loss, defined as:

where \(I_{\text {GT}}\) is the ground truth LF and \(I_{\text {LR}}\) is the input sparse LF. This loss encourages pixel-wise fidelity in reconstructed views.

Performance was quantitatively assessed using the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), computed on the Y channel of reconstructed LF images. The metrics were averaged across all 45 reconstructed views in the \(2\times 2 \rightarrow 7\times 7\) setting and reported per dataset. These evaluations provide a holistic view of both visual fidelity and structural preservation across angular views, confirming the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed method.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed model, we conducted a comprehensive comparative evaluation against several SOTA LFASR methods. The benchmark models selected for comparison include LFASR-geo24, FS-GAF25, DistgASR33, QEASR36, EASR34, DFEASR35, ELFR42, CSTNet38, and CTDDNet40. For consistency and fairness in evaluation, we adopted two widely used reconstruction tasks: \(2 \times 2 \rightarrow 7 \times 7\) and \(2 \times 2 \rightarrow 8 \times 8\) ASR.

\(2\times 2 \rightarrow 7\times 7\) reconstruction task

The quantitative evaluation results for the \(2 \times 2 \rightarrow 7 \times 7\) ASR task are summarized in Table 2. The proposed method demonstrates competitive performance, achieving consistently strong PSNR and SSIM results across both real-world and synthetic datasets. In particular, for real-world datasets, it achieves the best PSNR on the Occlusions and Reflective datasets while ranking second on 30scenes, and it obtains the best average performance across all real-world benchmarks. For synthetic datasets, it attains the highest PSNR on HCIold and ranks second in SSIM on HCInew, while also achieving the best average results across synthetic benchmarks. These outcomes underscore the robustness of the proposed method across diverse LF scenarios.

On real-world datasets such as 30Scenes, Occlusions, and Reflective, The proposed model achieves PSNR values of 44.09 dB, 40.31 dB, and 39.87 dB, respectively, along with consistently high SSIM scores, ranking among the top-performing methods across all benchmarks, reflecting high reconstruction fidelity. For synthetic datasets, which involve wider baselines and greater disparity variation, the model achieves 37.90 dB PSNR on HCInew and 44.06 dB on HCIold. Although ELFR42 surpasses our PSNR on HCInew with 38.81 dB, our method yields the highest SSIM (0.985), indicating better structural consistency and perceptual quality.

Averaged across all datasets, our model surpasses competing approaches, achieving an average PSNR of 41.42 dB and SSIM of 0.990 on real-world data, and 40.98 dB PSNR with 0.989 SSIM on synthetic data. These consistent improvements across both challenging and diverse scenarios highlight the robustness, effectiveness, and strong generalization capacity of the proposed LFASR method.

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, qualitative comparisons of reconstructed LF images are presented in Figs. 3 and 4, covering both real-world and synthetic datasets. The visual results, including zoomed-in regions, highlight the superior reconstruction fidelity achieved by the proposed method.

For real-world datasets, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In 30Scenes_IMG_1743, competing approaches fail to accurately reconstruct the white line on the wall, and in occlusions_35, they show notable degradation in preserving building boundaries under occlusion. Our method demonstrates significant improvements in these complex scenarios, producing reconstructions that closely align with the ground truth in both spatial accuracy and occlusion consistency.

Similar improvements are observed in synthetic scenes such as HCI_new_bedroom and HCI_new_stilllife (Fig. 4), prior methods often fail to restore fine-grained details, such as the painting on the wall or tablecloth patterns, resulting in blurring or structural loss. In contrast, our model successfully restores these high-frequency details with enhanced clarity and reduced artifacts.

Furthermore, residual error maps reveal that our method introduces fewer reconstruction artifacts than competing approaches. Analyzing the reconstructed EPIs reveals that our model maintains linear structures with high accuracy, indicating effective modeling of angular geometry. While prior models often introduce angular distortions or misaligned parallax, our network maintains geometric coherence across views, highlighting its robustness in preserving LF structure under challenging conditions.

\(2\times 2 \rightarrow 8\times 8\) reconstruction task

In this experiment, we evaluate the performance of the proposed method on the \(2\times 2 \rightarrow 8\times 8\) ASR task. Unlike the previous \(2\times 2 \rightarrow 7\times 7\) task, this scenario involves an integer upsampling factor of 4, eliminating the need for intermediate downsampling or fractional upsampling steps. This simplification allows for a more streamlined reconstruction pipeline.

To adapt the model to this configuration, we adjust the initial convolutional layer of ASR stage to utilize a \(3 \times 3\) kernel with a stride of 1 and padding of 1. This modification ensures effective local feature extraction while preserving the spatial dimensions of the input.

Table 3 presents a comprehensive quantitative comparison of the proposed method against several SOTA LFASR techniques on both synthetic and real-world datasets. The results indicate that our approach maintains superior reconstruction performance across all evaluated test cases, further validating its scalability and robustness under higher angular resolution demands.

For real-world datasets, our model achieves substantial improvements in reconstruction quality. Specifically, in terms of the average PSNR it outperforms DFEASR35 by 1.25 dB, DistgASR33 by 0.49 dB, EASR34 by 0.44 dB, QEASR36 by 0.56 dB, and CTDDNet40 by 0.35 dB. On synthetic datasets typically more challenging due to their wider baselines and complex disparity variations, our model achieves even more notable gains: 1.76 dB over DFEASR35, 1.78 dB over DistgASR33, 1.76 dB over EASR34, 0.51 dB over QEASR36, and 1.21 dB over CTDDNet40. These average PSNR improvements are accompanied by higher SSIM scores, reflecting our model’s enhanced ability to preserve angular consistency and fine structural details.

To support these quantitative findings, qualitative comparisons are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. Visual inspection of zoomed-in regions confirms that our method yields sharper textures, cleaner object boundaries, and fewer reconstruction artifacts than competing methods, underscoring its superior visual fidelity.

To further evaluate the generalization capability of our model, we performed view extrapolation experiments on the \(2\times 2 \rightarrow 8\times 8\) task. In this setting, the model is required to synthesize novel viewpoints beyond the angular range of the input views given. We compare our results against two methods–DistgASR33 and EASR34–and present the quantitative results in Table 4. Across all datasets and extrapolation tasks, our method consistently demonstrates superior performance.

On the 30Scenes dataset, our model achieves PSNR gains of 0.35 dB and 0.32 dB over DistgASR33, and 0.49 dB and 0.46 dB over EASR34, for the Extra.1 and Extra.2 extrapolation tasks, respectively. Similarly, on the Occlusion dataset, we observe improvements of 0.27 dB and 0.44 dB compared to DistgASR, and 0.33 dB and 0.42dB compared to EASR. For the Reflective dataset, our method surpasses DistgASR by 0.15 dB and 0.29 dB, and EASR by 0.06 dB and 0.24 dB on Extra.1 and Extra.2, respectively.

These consistent improvements across diverse and challenging extrapolation scenarios highlight the robustness of our method and its capacity to generate high-fidelity novel views, even in regions with limited angular support.

Efficiency analysis

In this subsection, we evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed method in comparison with existing approaches, focusing on two key metrics: model size and inference time. The analysis is conducted under the standard \(2 \times 2 \rightarrow 7 \times 7\) ASR task using real-world and synthetic datasets. To ensure a fair comparison, all experiments are executed on a unified hardware platform comprising a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU, CUDA version 11.7, and cuDNN version 8.8.0. Each inference test is repeated five times, and the reported inference times represent the average across runs to ensure statistical robustness and reduce variability due to hardware fluctuations.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of various LFASR methods in terms of inference time and model size on both real-world and synthetic datasets. On the real-world dataset, our method outperforms FS-GAF25 and DistgASR33 in terms of inference time, while demonstrating competitive performance relative to other approaches. Similarly, on synthetic datasets, our model achieves faster inference than FS-GAF25, DistgASR33, and ELFR42, and remains comparable to the remaining techniques.

In terms of model complexity, our architecture maintains a smaller parameter count than EASR34, while remaining competitive with other methods. Importantly, our model (denoted as “Ours”) consistently achieves the highest average PSNR across both dataset categories, highlighting its ability to strike an effective balance between reconstruction accuracy, runtime efficiency, and parameter economy.

Ablation study

To better understand the contributions of individual components within the proposed framework, we conduct a comprehensive ablation study. Specifically, several network variants were implemented by selectively modifying or removing key architectural elements from the core TVFEB. The performance of each variant is compared against the proposed model on the synthetic dataset to evaluate the impact of each design choice. The configuration and motivation behind each variant are detailed below to enable a thorough evaluation of their respective contributions to the overall model performance.

Without EPIs path (w/o EPIs)

In this variant, the EPI branch was removed from the TVFEB to assess its contribution to reconstruction quality. Specifically, only the SAI and MacPI branches were retained and processed in parallel, with their extracted features aggregated and subsequently refined by the spatial_Group module. As reported in Table 6, this modification led to a performance drop of 0.29 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 0.17 dB on the HCI_old dataset. These results highlight the critical role that epipolar features play in enhancing reconstruction accuracy, particularly in capturing angular dependencies.

Without SAIs path (w/o SAIs)

Similarly, in this variant, the SAI branch within the TVFEB was omitted to evaluate its specific contribution to the overall reconstruction performance. Only the EPI and MacPI branches were preserved and processed in parallel, and their combined features were refined through the spatial_Group module. As shown in Table 6, this modification resulted in a PSNR reduction of 0.21 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 0.25 dB on the HCI_old dataset. These findings underscore the importance of SAI-based features in capturing spatial details and enhancing the detail and quality of the reconstructed views.

Without MacroPIs path (w/o MacroPIs, w/o Mac_spa, w/o Mac_ang)

To evaluate the contribution of MacroPI-based features, we implemented three variants. In the first variant (w/o MacroPIs), the entire MacroPI branch within the TVFEB was removed. Only the EPI and SAI branches were retained, and their outputs were aggregated and refined using the spatial_Group module. This modification led to a notable reduction in reconstruction quality, with PSNR drops of 0.68 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 0.89 dB on the HCI_old dataset, highlighting the significance of MacroPI-derived features.

To further investigate the roles of individual components within the MacroPI branch, we introduced two additional variants. In the second variant (w/o Mac_spa), the spatial sub-branch of the MacroPI pathway was excluded, resulting in PSNR decreases of 0.34 dB on HCI_new and 0.32 dB on HCI_old. This demonstrates the relevance of spatial feature extraction from the MacroPI representation. The third variant (w/o Mac_ang) removed the angular sub-branch, yielding PSNR drops of 0.47 dB and 0.42 dB on the HCI_new and HCI_old datasets, respectively. These results confirm the complementary importance of angular feature modeling within the MacroPI domain.

Without spatial group (w/o spa_group)

In this variant, we removed the spatial refinement module (spatial_Group) within the TVFEB to assess its specific contribution to the overall reconstruction performance. The SAI, EPI, and MacroPI branches were retained and processed in parallel, and their outputs were aggregated without the subsequent refinement typically performed by the spatial_Group.

As reported in Table 6, this modification led to a substantial decline in reconstruction accuracy, with PSNR reductions of 4.34 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 2.29 dB on the HCI_old dataset. These results clearly highlight the critical role of deep spatial convolutions in the spatial_Group module, which are essential for capturing fine-grained spatial features and enhancing the consistency and quality of the reconstructed LF.

Without TRi-visualization (w/o TV)

To isolate the effect of the tri-visualization feature extraction strategy, this variant removes the parallel feature extraction from SAIs, EPIs, and MacroPIs. Instead, only the spatial_Group module was retained to refine the features derived from a single LF representation.

As presented in Table 6, this modification resulted in a substantial performance degradation, with PSNR decreasing by 8.98 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 7.53 dB on the HCI_old dataset. These findings strongly emphasize the pivotal role of tri-visualization feature integration in enhancing the spatial-angular representation and reconstruction accuracy of LF images.

Sequential processing (Sequential)

In this variant, the original parallel processing design of the TVFEB was replaced with a sequential configuration. The LF representations were processed in a fixed order–first EPI, followed by SAI, and then MacroPI–prior to refinement by the spatial_Group module. This setup aimed to investigate the impact of processing order and feature interaction strategy on overall reconstruction performance.

As shown in Table 6, this sequential design led to a notable decrease in performance, with PSNR dropping by 1.98 dB on the HCI_new dataset and 1.38 dB on the HCI_old dataset. These results underscore the effectiveness of the original parallel processing strategy in better capturing complementary features from different LF visualizations and enabling more coherent feature integration.

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, qualitative comparisons of reconstructed LF images are provided in Fig. 7, using the bicycle scene from the HCI_new dataset. The visual results include error maps of different ablation variants, which illustrate the notably improved reconstruction fidelity achieved by our approach.

Application to depth estimation

To evaluate the angular consistency of the reconstructed \(7 \times 7\) LF images, we applied depth estimation to the outputs generated by various methods, including our own.For this purpose, we employed the Spinning Parallelogram Operator (SPO)51, a widely used and robust technique for extracting disparity maps from LF data. This analysis allows us to assess the effectiveness of our reconstruction in maintaining coherent angular structures essential for accurate depth inference.

Visual comparisons of depth maps estimated using SPO51 from \(7 \times 7\) LF images reconstructed by different methods are presented. The mean square error (MSE) between the depth maps derived from the ground-truth densely sampled LF and those obtained from the reconstructed LF images is employed as the quantitative evaluation metric.

The evaluation was carried out on three representative scenes from the synthetic dataset: buddha, herbs, and bicycle. To ensure a reliable assessment, the depth maps derived from ground truth LF images were used as reference benchmarks, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The visual results indicate that our method achieves accurate depth estimation performance, particularly in occluded and structurally complex regions. This improvement can be attributed to the model’s ability to preserve angular geometry and disparity cues, leading to more reliable and detailed depth inference. Ultimately, this demonstrates that the proposed method not only excels in view reconstruction but also facilitates downstream tasks such as depth estimation through its superior structural preservation.

Limitations and future directions

Comparison of reconstruction performance (PSNR) across three datasets with different disparity ranges: 30scenes \([-1,1]\), HCI_old \([-3,3]\), and HCI_new \([-4,4]\). The proposed method consistently achieves the best performance on 30scenes and HCI_old, while the hybrid approach ELFR demonstrates superior robustness in the high-disparity HCI_new dataset.

Although the proposed method achieves strong performance on most benchmark datasets, its effectiveness is reduced in cases involving extreme disparities. For instance, on the HCInew dataset, our approach attains 37.90 dB PSNR–outperforming many alternatives but still below the 38.81 dB reported by the hybrid reconstruction framework ELFR42 as shown in Fig. 9. This gap underscores a fundamental limitation of depth-free approaches, which often face difficulties under severe occlusion and large disparity variations. Future research could explore hybrid strategies that combine depth-guided and depth-free mechanisms, with the aim of enhancing robustness in such challenging scenarios. In addition, incorporating efficiency-oriented architectures, such as lightweight transformer variants or state-space models like Mamba, offers a promising direction for reducing both model size and inference time, thereby improving practicality for real-world applications.

Conclusion

In this paper, we introduced a novel framework for light field angular super-resolution (LFASR) that employs a unified tri-visualization feature extraction strategy. By jointly leveraging three complementary representations–Sub-Aperture Images, Epipolar Plane Images, and Macro-Pixel Images–the proposed Tri-Visualization Feature Extraction Block (TVFEB) effectively captures diverse spatial and angular dependencies. These features are subsequently refined through a deep spatial aggregation module to better reconstruct complex structural information in LF data. The overall architecture is structured into three key stages: Early Feature Extraction, Advanced Feature Refinement, and Angular Super-Resolution. This hierarchical design supports robust multi-perspective feature learning, enabling the accurate synthesis of densely sampled angular views even in challenging scenarios involving large disparities and occlusions. Extensive experiments conducted on both synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrate that the proposed method delivers competitive performance against SOTA LFASR techniques. In addition to achieving strong PSNR and SSIM scores, our model exhibits enhanced visual quality, improved angular consistency, and superior depth estimation capability. While a slight performance drop is observed in high-disparity scenes such as those in the HCInew dataset, this highlights a promising direction for future work, particularly through the incorporation of depth-aware refinement mechanisms. Finally, our efficiency analysis confirms that the proposed method achieves a favorable balance between reconstruction accuracy, computational complexity, and inference speed, making it a practical solution for real-world LF imaging applications.

Data availability

The datasets and code generated and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the GitHub repository [LFASR_TV] at [https://github.com/ebrahem00/LFASR_TV].

References

Levoy, M. & Hanrahan, P. Light field rendering. In Seminal Graphics Papers: Pushing the Boundaries 2, 441–452 (2023).

Gortler, S. J., Grzeszczuk, R., Szeliski, R. & Cohen, M. F. The lumigraph. In Proceedings of the 23rd annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, 43–54 (1996).

Wu, G. et al. Light field image processing: An overview. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 11, 926–954 (2017).

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Guo, Y., Xiao, C. & An, W. Selective light field refocusing for camera arrays using bokeh rendering and superresolution. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 26, 204–208 (2018).

Chen, J., Hou, J., Ni, Y. & Chau, L.-P. Accurate light field depth estimation with superpixel regularization over partially occluded regions. IEEE Transactions on Image Process. 27, 4889–4900 (2018).

Peng, J., Xiong, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, D. Zero-shot depth estimation from light field using a convolutional neural network. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging 6, 682–696 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Deoccnet: Learning to see through foreground occlusions in light fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 118–127 (2020).

Yu, J. A light-field journey to virtual reality. IEEE MultiMedia 24, 104–112 (2017).

Kim, C., Zimmer, H., Pritch, Y., Sorkine-Hornung, A. & Gross, M. H. Scene reconstruction from high spatio-angular resolution light fields. ACM Trans. Graph. 32, 73–1 (2013).

Xu, Y., Nagahara, H., Shimada, A. & Taniguchi, R.-i. Transcut: Transparent object segmentation from a light-field image. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 3442–3450 (2015).

Wilburn, B. et al. High performance imaging using large camera arrays. In ACM siggraph 2005 papers, 765–776 (2005).

Laboratory, S. G. The (new) stanford light field archive. http://lightfield.stanford.edu. Accessed: Jun. 26, 2025.

Lytro illum. https://www.lytro.com/. Accessed: Jun. 26, 2025.

Raytrix. 3d light field camera technology. https://www.raytrix.de/. Accessed: Jun. 26, 2025.

Wang, Y. et al. Ntire 2025 challenge on light field image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, 1227–1246 (2025).

Yeung, H. W. F. et al. Light field spatial super-resolution using deep efficient spatial-angular separable convolution. IEEE Transactions on Image Process. 28, 2319–2330 (2018).

Liao, Y., Song, L., Zhang, G. & Fang, F. Multi-level disparity-guided transformers for light field spatial super-resolution. Pattern Recognit. 111803 (2025).

Li, M., Ma, B. & Wang, S. Hierarchical spatial-angular integration for lightweight light field image super-resolution. Knowledge-Based Syst. 315, (2025).

Wanner, S. & Goldluecke, B. Variational light field analysis for disparity estimation and super-resolution. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 36, 606–619 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Liu, Y. & Dai, Q. Light field from micro-baseline image pair. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3800–3809 (2015).

Zhang, F.-L. et al. Plenopatch: Patch-based plenoptic image manipulation. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 23, 1561–1573 (2016).

Kalantari, N. K., Wang, T.-C. & Ramamoorthi, R. Learning-based view synthesis for light field cameras. ACM Transactions on Graph. (TOG) 35, 1–10 (2016).

Choi, I., Gallo, O., Troccoli, A., Kim, M. H. & Kautz, J. Extreme view synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 7781–7790 (2019).

Jin, J., Hou, J., Yuan, H. & Kwong, S. Learning light field angular super-resolution via a geometry-aware network. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 34, 11141–11148 (2020).

Jin, J. et al. Deep coarse-to-fine dense light field reconstruction with flexible sampling and geometry-aware fusion. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis Mach. Intell. 44, 1819–1836 (2020).

Mitra, K. & Veeraraghavan, A. Light field denoising, light field superresolution and stereo camera based refocussing using a gmm light field patch prior. In 2012 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 22–28 (IEEE, 2012).

Shi, L., Hassanieh, H., Davis, A., Katabi, D. & Durand, F. Light field reconstruction using sparsity in the continuous fourier domain. ACM Transactions on Graph. (TOG) 34, 1–13 (2014).

Vagharshakyan, S., Bregovic, R. & Gotchev, A. Light field reconstruction using shearlet transform. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 40, 133–147 (2017).

Yoon, Y., Jeon, H.-G., Yoo, D., Lee, J.-Y. & So Kweon, I. Learning a deep convolutional network for light-field image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops, 24–32 (2015).

Zhu, H., Guo, M., Li, H., Wang, Q. & Robles-Kelly, A. Revisiting spatio-angular trade-off in light field cameras and extended applications in super-resolution. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 27, 3019–3033 (2019).

Wu, G., Liu, Y., Fang, L., Dai, Q. & Chai, T. Light field reconstruction using convolutional network on epi and extended applications. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 41, 1681–1694 (2018).

Wu, G., Liu, Y., Dai, Q. & Chai, T. Learning sheared epi structure for light field reconstruction. IEEE Transactions on Image Process. 28, 3261–3273 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Disentangling light fields for super-resolution and disparity estimation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis Mach. Intell. 45, 425–443 (2022).

Liu, G., Yue, H., Wu, J. & Yang, J. Efficient light field angular super-resolution with sub-aperture feature learning and macro-pixel upsampling. IEEE Transactions on Multimed. 25, 6588–6600 (2022).

Salem, A., Elkady, E., Ibrahem, H., Suh, J.-W. & Kang, H.-S. Light field reconstruction with dual features extraction and macro-pixel upsampling. IEEE Access (2024).

Elkady, E., Salem, A., Kang, H.-S. & Suh, J.-W. Reconstructing angular light field by learning spatial features from quadrilateral epipolar geometry. Sci. Reports 14, 29810 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. Geometry-assisted multi-representation view reconstruction network for light field image angular super-resolution. Knowledge-Based Syst. 267, (2023).

Chen, R. et al. Multiplane-based cross-view interaction mechanism for robust light field angular super-resolution. IEEE Transactions on Vis. Comput. Graph. (2025).

Li, Y., Wang, X., Zhou, G., Zhu, H. & Wang, Q. Sheared epipolar focus spectrum for dense light field reconstruction. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis Mach. Intell. 46, 3108–3122 (2023).

Liu, D., Mao, Y., Zuo, Y., An, P. & Fang, Y. Light field angular super-resolution network based on convolutional transformer and deep deblurring. IEEE Transactions on Comput. Imaging 10, 1736–1748 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Light field angular super-resolution by view-specific queries. The Vis. Comput. 41, 3565–3580 (2025).

Chen, Y., Huang, X., An, P. & Wu, Q. Enhanced light field reconstruction by combining disparity and texture information in psvs via disparity-guided fusion. IEEE Transactions on Comput. Imaging 9, 665–677 (2023).

Wu, G., Zhou, Y., Fang, L., Liu, Y. & Chai, T. Geo-ni: Geometry-aware neural interpolation for light field rendering. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis Mach. Intell. (2025).

Liu, G., Yue, H., Li, K. & Yang, J. Adaptive pixel aggregation for joint spatial and angular super-resolution of light field images. Inf. Fusion 104, (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Four-dimension efficient pixel-frequency transformer for light field spatial and angular super-resolution. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 154, (2025).

Honauer, K., Johannsen, O., Kondermann, D. & Goldluecke, B. A dataset and evaluation methodology for depth estimation on 4d light fields. In Asian conference on computer vision, 19–34 (Springer, 2016).

Wanner, S., Meister, S. & Goldluecke, B. Datasets and benchmarks for densely sampled 4d light fields. In VMV 13, 225–226 (2013).

Raj, A. S., Lowney, M., Shah, R. & Wetzstein, G. Stanford lytro light field archive. LF2016. html (2016).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. H. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 610–621 (2007).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Zhang, S., Sheng, H., Li, C., Zhang, J. & Xiong, Z. Robust depth estimation for light field via spinning parallelogram operator. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 145, 148–159 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A5A8026986) and in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2023-NR076833).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and A.S.; methodology, E.E. and A.S.; software, E.E. and A.S.; formal analysis, E.E. and A.S.; investigation, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; resources, J.-W.S and H.-S.K; data curation, E.E. and A.S.; writing–original draft preparation, E.E.; writing–review and editing, E.E. and A.S. and J.-W.S and H.-S.K; validation, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; visualization, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; supervision, J.-W.S and H.-S.K; project administration, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; funding acquisition, J.-W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elkady, E., Salem, A., Kang, HS. et al. Tri-visualization feature extraction for light field angular super-resolution. Sci Rep 15, 32688 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21108-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21108-0