Abstract

The greater challenges in the manufacturing and machine tool sectors are the periodic replacement of moving components due to wear, and its subsequent escalated product cost. The present research aims to address the issue by developing of novel lightweight surface composite reinforced with hybrid particles SiC and Y2O3 processed through the Friction Stir Process (FSP). The test specimens were prepared by FSP by following four different wt.% of hybrid particles. The sliding tribological examination was executed to examine the wear characteristics of the surface composite at both ambient and elevated temperature environments. The achievement of dynamic recrystallisation is acknowledged through microstructure and grain size analysis results that reveal the finer grain structure at the nugget zone with the smaller grain size. The wear assessment outcomes endorse the improved wear characteristics of the Al-3SC-1Yo variant by upholding its 126% and 53.88% higher wear resistance than the base material at ambient and elevated temperatures, subject to the normal load of 45 N. The post-worn-out surface analyses proclaim that ambient wear is driven by adhesion, two and three-body abrasion, whereas elevated temperature wear is driven by pure abrasion. It is comprehended from the wear results that 90% more wear loss is recorded during the elevated temperature than the same in the ambient environment. The quantitative comparison of ambient and elevated temperature wear through the observation of surface topography, and the inclusion of hybrid reinforcement on unique base materials are the key novelties of the proposed study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emerging and consistent industrial needs require materials with sophisticated properties and lightweight. Weight saving with improved properties for any component is the dominant preference of the aerospace and automobile sectors to cater for the fuel-saving demand1,2,3,4,5. In particular, the moving parts of the machinery are prone to periodic replacement owing to their wear and loss of material6,7,8,9. To address the issue, numerous surface modification techniques like surface coatings10, surface hardening11, laser-based cladding12, surface chemical treatment13, and surface mechanical treatment14 are employed. Out of which, most of the processes are targeting to introduce hard material on the surface. However, the surface mechanical treatment approach is to mitigate the microstructure of the surface through a secondary process, which imparts severe plastic deformation. Shot peening15, burnishing16, Laser Shock Peening (LSP)17, Ultrasonic Impact Treatment (UIT)18, roller burnishing19, surface hammering20 and Friction Stir Processing (FSP) are a few of the processes in practice to induce surface modification. Moreover, the FSP is a cheaper and more versatile process to produce surface composites. The foremost advantage of the FSP is the introduction of finer grains through dynamic recrystallisation supplemented by frictional heat and severe plastic deformation. It is more preferable than some other surface mechanical treatments, because of its dual mode of grain refining and nucleating. The frictional heat enables the newer grain nucleation, and the finer grains are transformed due to the rotation of the pin, imparting rigorous plastic deformation21. Apart from that, the mitigation of FSP process parameters and the number of passes are also reported for the microstructure improvement. Furthermore, the attempts to enhance the hardness of the surface by adding prominent ceramic particles within the slot before the FSP. Many researchers attempted to develop a surface composite using FSP by infusing different particles like Al2O322, SiC23, TiB224, TiC25, B4C26, CNTs27, Graphene Oxide (GO)28, graphene29 and reduced GO (rGO)30 either in mono or in hybrid. This research attempt aims to develop a light surface composite reinforced through SiC and an unexplored rare earth compound, Y2O3, through FSP and to showcase its supremacy in acting as a phenomenal wear-resistant material. Since Y2O3 is known grain refiner, it enhances the grain refinement during the grain refinement supplemented by dynamic recrystallisation. Moreover, a wear study at elevated temperatures usually experiences an oxide formation, from both the base metal and reinforcements, which helps to minimise the wear loss. However, higher formation of oxide layer and its brittle failure causes the debris and acts as a third body to intensify the wear. Eventually, Y2O3 is a fully oxidised and thermally stable component, and further oxidation at the elevated temperature is ruled out. A 15 wt.% inclusion of WC particles to improve the wear characteristics through FSP was reported by Patel et al.31. They studied the impact of process parameters on the severe deformation and frictional heat, in addition to the effect of WC. Patel et al.32 attempted to develop of surface composite by reinforcing two hard particles, WC and ZrSiO4, in an equal weight percentage of 7.5%. Consequent wear examination results highlighted the formation of Al2O3 intermetallic compound and recrystallised grain structure were the pivotal factors in delivering the improved wear properties. Sathishkumar et al.33 implemented a response surface methodology technique to arrive at the optimal FSP parameter while they were developing AZ 31 surface composite reinforced with TiC, to achieve better wear characteristics. Subsequently, the report revealed that the wear was governed by the wear track, delamination and oxide formation. Additionally, the grain nucleation, grain refinement, uniform dispersion of TiC, and good interfacial bonding were the attributable factors for the attainment of improved wear resistance.

The impact of tool speed and the axial load on the microstructure and wear characteristics was examined by Kaya et al34. When they were engaging in the development of an Al-5083 surface composite reinforced with SiC particles via FSP. The author concluded that 38% and 42% of enhancement were observed for hardness and wear resistance, respectively, as the trial was done by following an 8000 N axial load and 900 rpm tool rotation. A novel attempt to mitigate the grain size by implementing cryo-FSP and experimenting at cryogenic temperature to avail a faster cooling rate for a surface composite composed of Al-7075-SiC. The remarkable grain size reduction of 1–3 µm was attained by the inducement of a smaller dendritic grain quality supplemented by the grain nucleation. The effect of multiple passes of FSP on the microstructure, hardness and wear capacity was revealed by Zhang35. Not only these studies, but many significant attempts were applied to enhance the tribological properties of Al 356- TiC36, Al 5052- ZrO237, AA6061-316 SS35, Al 7050-SiC + TiB238, Al-B4C39, A390-Al2O340 FSP surface composite. A comprehensive review compiled by Bharti et al.41 explores the various reinforcement, tooling techniques, and FSP parameters exposed so far to provide a list of properties like tensile strength, flexural strength, hardness, wear strength, and refined microstructure.

The fundamental aim of the work is to highlight the contribution of hybrid particles SiC and Y2O3 in developing hard surfaces to yield a better wear-resistant surface composite. The secondary objective of the research is to recommend a novel wear-resistant lightweight surface composite to demonstrate its potential to replace the heavier monolithic components assembled in automobiles and aircraft vehicles. Based on the stringent literature survey and the author’s knowledge, there was no single research attempt made to develop the FSPed Al-5052 surface composite by infusing this hybrid SiC and Y2O3 particles. There were many reports related to the surface composites reinforced with different ceramic and natural-based hard particles, except for the inclusion of Y2O3, either monotonic or hybrid. This novel hybrid inclusion in the development of surface composite through FSP, and subsequent experiment wear study at both ambient and elevated temperatures, highlights a clear knowledge gap in this field. To impart balanced wear resistance and anti-oxidation, an elevated working temperature environment is a secondary objective of the study. This could be the prime novelty that exists in the present research, in addition to the scientific validation of grain refinement and post-worn-out surface topographical analysis.

Materials and methods

Base material

Due to the excellent weldability quality, Al-5052 was the parent material to fabricate the FSPed surface composite. The material supplier in Metal Mart Coimbatore, India, was contracted to procure Al-5052 plates with a dimension of 120 mm length × 100 mm width × 6 mm thickness, whose chemical constituents, physical and mechanical attributes are tabulated in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Reinforcements

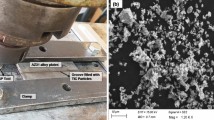

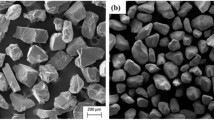

The present research aims to demonstrate an FSPed composite that is significantly hard and wear-resistant. Hence, the reinforcements chosen are SiC and Y2O3 from the ceramic family to showcase the necessary wear-resistance behaviour and surface hardness. Alpha Chemicals, situated in Bangalore; India, was requested to supply the reinforcements. The particle sizes were authenticated as 80 and 5 µm for SiC and Y2O3 by the particle analyser result depicted in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. The reinforcement composition of weight percentage is managed in four variants. The weight percentage of reinforcements and their relevant labelling are shown in Table 3. Based on the literature study, it is well known that Y2O3 is a thermally stable anti-oxidising component and a good grain refiner43,44. Hence, to achieve the optimal wear-resistant performance, Y2O3 is proposed to be added in four different compositions along with the anti-wear agent SiC.

Processing of FSPed surface composite

A computer-aided vertical milling machine (VMC-LMW-KODI 40) was pressed into service to fabricate the FSPed composite by incorporating the mentioned reinforcements. Figure 2 depicts the collective understanding of FSP insight. A 2 mm depth and 3 mm wide grooves were machined through the CNC end milling process to accommodate the tool pin and to load the reinforcement powder, as shown in Fig. 3a. The reinforcement powder was cleaned, rinsed with acetone, and then dried in a muffle furnace. The dried powder of both reinforcements was weighed priorly to the reinforcement design shown in Table 3. The weighed powder was loaded into the ball mill and was allowed to amalgamate homogenously by running at 700 rpm for 30 min. The amalgamated powder was preheated in the muffle furnace at 300 °C and was fed into the machined groove throughout the length by dispersing uniformly. A shoulder without a pin possessing a 20 mm diameter was made to run over the slot at 750 rpm to seal the reinforcement. Subsequently, a shoulder pin made out of H13 Hot-Work Tool steel, with an 18 mm shoulder diameter and 6 mm pin diameter, is shown in Fig. 3c was pressed to run over the sealed slot at 1250 rpm rotational speed49, 50 mm/min feed rate50, 2° tilt angle and 6 kN axial load, thereby causing severe plastic deformation. The pin was threaded up to 5 mm to drill and distribute the powder to form a homogenous structure with the base material. The finished FSPed composite is shown in Fig. 3b. The wear test specimens of dimensions 10 mm in diameter and 6 mm in length, are carved out from the FSPed composite.

Characterization

The complete microstructure and post-wear studies were executed by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL- JSM IT710HR). The compound analysis was carried out through an X-ray diffractometer (XRD- Malvern Panalytical-Xpert3 MRD).

Wear study

A dry sliding wear testing apparatus called the Pin-on-disc set-up (DUCOM-India, TR-20LE-PHM-250), as illustrated in Fig. 4, was hired to examine the wear attributes of the developed surface composite. The counter disc made out of EN-28 grade with a hardness value of 90 HRC and surface imperfections to the magnitude of 17 µm was used to slide on the specimens carved to the dimensions (10 mm dia × 6 mm length) advocated by the ASTM E-92 standard.

The constant sliding wear testing parameters were maintained as follows: sliding velocity- 1.5 m/s, sliding distance: 2.5 km, rotational speed of the disc: 717 rpm51. The wear attributes of the composite were measured at both ambient and high temperatures. The ambient temperature study was executed by changing the normal load at three levels, 15, 30 and 45 N52. and was exposed to a constant 28 °C of room temperature, whereas the high-temperature test was executed by varying the temperatures at three levels of 75°, 150°, and 225 °C53 and was exposed constant normal load of 45 N. The temperature ranges were arrived at based on the feasibility, which addresses the material stability and oxidation nature at high temperatures. The pneumatic system and temperature controller regulated the load and temperature, respectively. To achieve error-free results, the average values of the coefficient of friction and wear rate from three distinct experiments running at similar conditions were utilised to prepare plots. The computerised data acquisition system facilitated the frictional force and the height loss. The dirt on the disc was removed with an emery sheet and rinsed with acetone after every experiment. The volume loss of the pin was detected from the weight loss of the pin by following the equation shown in 1, and in turn, it was used to compute the wear rate as follows,

Where wi, wf, and ρ are the initial, final weight and density of the pin53.

Where vs and ve are volumes at the start and end, respectively. SDs and SDe are the sliding distances before the start and end, respectively.

The coefficient of friction was calculated by using the relation,

Results and discussion

Characterization

The added advantage of the FSP is a significant secondary grain refinement through the combined action of frictional heat and rigorous plastic deformation. The ploughing action of the threaded pin makes the material deform considerably, and then the compressive action of the shoulder completes the severe deformation by collapsing the larger grains into smaller grains. Further, the grain nucleation is also initiated with the prominent heat delivered during the contact friction between the shoulder and the material. However, the tool speed and its shoulder contact prompt the development of three different zones called nugget, Thermo Mechanically Affected zone (TMAZ) and Heat Affected Zone (HAZ). The grain structure attained at the individual zone is depicted in Fig. 5a–c

A nugget zone is an area under the tool pin where the material experiences the complete ploughing action associated with the complete frictional heat. The frictional heat delivers the heterogeneous nucleation of grains. Further, the plastic deformation caused by the ploughing action also transforms the larger grains into smaller ones. Hence, the collective heterogeneous nucleation and finer refinement of grains yield the fine microstructure, which is authenticated in Fig. 5a. Subsequently, the grain size evaluation result manifests the measured average grain size as 49 µm. The second zone, adjacent to the nugget zone, is known to be TMAZ, wherein the effect of severe plastic deformation and heat is minimal owing to the increased distance radially from the centre of the tool pin. The absence of ploughing action dents the severe plastic deformation despite leaving minimal plastic deformation due to the squeezing action of the shoulder. The frictional heat is also exhausted as the radial distance increases from the axis of the tool pin; hence, the nucleation effect succumbs to the insufficient heat to nucleate the newer grains. The combined minimal plastic deformation and nucleation partly enhance the grain structure, as Fig. 3b depicts. The micrograph acknowledges the existence of a coarser and finer mixer of grain size. The third zone, which also deviates from the centre of the tool pin axis, recorded partial grain size refinement since it evolved with low plastic deformation and frictional heat. At HAZ, the effect of plastic deformation and friction heat is drastically minimised as the radial distance of the zone increases significantly from the centre of the tool pin axis. The negligible compressive force and the frictional heat exerted by the end of the shoulder pin fail to induce a sizeable plastic deformation and grain nucleation; hence, the micrograph depicted in Fig. 5c authenticates the zero-grain refinement. Further, the grain size measurement is executed and shown in Fig. 6a–c. through Image J software corroborates the quantitative comparison of the grain sizes between the three zones. It is witnessed from the statistical calculation of the grain size for all three zones that the grain magnitude of the nugget zone has declined by 1.89 and 0.44 times that of the TMAZ and HAZ, respectively.

Figure 7 illustrates the compound analysis result of the proposed composites. The XRD analysis confirms the existence of the two hybrid reinforcements, SiC and Y2O3. The results show that the peaks of SiC and Y2O3 appear at 2θ values of 64.44 and 77.24, and their peak heights are also varied according to their percentage composition in the composite.

Hardness

Figure 8 reveals the comparative micro-hardness achieved by all the FSPed specimens. The hardness was observed at a 1 mm radial distance from both the extreme of the centre of the tool pin axis. The importance of the nugget zone is vivid through the trend with which the plots are reflected. Invariably, all the curves pertinent to the FSPed composite exhibit a similar trend.

It is interesting to view the immediate hype of all the FSPed composite’s hardness plots between the ranges of − 6 to + 6 mm radial distance. The area under the tool pin experiences larger plastic deformation and the higher frictional heat, in turn, causes the larger grain to disintegrate into finer grain size and nucleate newer grains. This fine-grain structure obtained through the process benefit helps to escalate the hardness. In parallel, the increased hardness for a reduced grain size is validated through the Hall–Petch theory54. The outer zones TMAZ and HAZ record a meagre hardness. Despite the comparison being made on the same nugget zone of all the FSPed composites, Al-3SiC-1 Yo secures the highest hardness among others. The balanced composition of both hard ceramic particles is the prime reason for their higher hardness. The agglomeration effect of Y2O3 reported in previous research restricts the hardness of other variants. Apart from the hardness obtained through dynamic recrystallisation, Al-3SiC-1 Yo attains a 50% higher hardness than the base alloy, which reflects the significant inclusion of balanced reinforcement of hybrid ceramic particles.

Ambient temperature wear analysis

The wear rate of the FSPed composites is assessed through a pin-on-disc apparatus. The volume of material loss for the sliding meter under the constant rotation of 717 rpm with varying normal loads of 15, 30 and 45 N is recorded from the data acquisition system from the wear test rig. The graph showing the wear rate is plotted for all the variants of the FSPed composite, including the base material under individual normal load, and the same is shown Fig. 9a–c. The cumulative wear rate observed at every incremental 0.5 km of sliding distance for all materials at three different loads is illustrated in Fig. 9d55.

It can be viewed from the wear results that the wear rate is in progress as the load and sliding distance are increasing. However, the response to the wear of the material is discrete though the trend is similar. The wear rate seems milder and heavier according to the wt. % of SiC and Y2O3. The nature of wear progression of all the variants of FSPed coupons comprises three stages: adhesion wear, and two and three-body abrasion wear56. In the first stage of adhesion wear, material loss is recorded due to steady-state wear. The interlocking of mutual asperities of the counter disc and the coupon’s surface induces a physical resistance, which is realised as friction due to adhesion. The magnitude of this steady-state adhesion wear also increases with the addition of normal load, as the increased normal load accelerates the effect of interlocking. The second stage of wear is through two-body abrasion in a steeper way, wherein the asperities are plastically deformed due to continuous sliding in association with the sustained normal load57. However, the wear loss is greater for the base material than for the FSPed composite. Since FSPed specimens are grain-refined and reinforced with hard particles, their rate of plastic deformation is quite lesser than the non-reinforced base material. It has already been validated through experiments that the hardness of the FSPed composites is greater than the base material. The hard particle’s addition retards the rate of plastic deformation because the crystallographic dislocation movements are halted by the hard particles. The third stage of wear is driven by three-body abrasion, wherein the wear rate is rapid, which is why the wear rate curve is accelerating linearly. The plastically deformed asperities are detached from the surface, and the same are embroiled between the surfaces of the coupons and counter disc. The embroiled detached particles act as an external body to intensify the wear by mimicking cutting particles. Based on three different normal loads, the maximum material loss is observed invariably for all the materials at a higher normal load of 45 N.

Nevertheless, the minimal wear is recorded for the variant Al-3SC-1Yo than the rest of the others. The remarkable wear resistance of Al-3SC-1Yo is recorded as 1.26 times higher than the base material at an elevated load of 45 N. In comparison with the other processed and reinforced variants at the same 45 N load, it has 73% higher wear resistance than Al-2SC-2 Yo. It is been already reported in the hardness test that the higher hardness is achieved by Al-3SC-1Yo. Similarly, the involvement of hard particles SiC in three portions of wt.% and uniformly distributed Y2O3 particles in one portion of wt.% are not only the key members to retard the plastic deformation in second-stage wear but also restrict the detachment of asperities thereby, minimising the embroilment of particles to aggravate the three-body abrasion mechanism. The agglomeration of Y2O3 particles beyond one portion of wt.% causes the rest of other FSPed variants to perform poorer against both two and three-body abrasion wear. Similar findings were reported by the researchers58, while they were attempting to develop hybrid and mono-FSPed aluminium composite reinforced with B4C and TiB2 particles. The authors declared that the hybrid-B4C- TiB2 FSPed composite exhibited a higher resilience against wear than B4C.

The contribution of dynamic recrystallisation in the present work to enhance grain refinement was also reflected in the cited work. Further, the inherent behaviour of TiB2 to nucleate the newer grains helped the dynamic recrystallisation to succeed more to achieving finer grains. Another researcher59 experienced a similar wear mechanism, which is reported in this study. The author reported that the three-body abrasion was the prime mechanism for aggravating the material loss at higher velocities, while they were developing an FSPed Mg composite.

The coefficient of friction is a dependent property of frictional force and normal load. Consequently, the frictional force is regulated by the surface nature of the contact region. The CoF observation is done from the experiments for all the variants, including the parent material, shown in Fig. 10a–d affirm the improved wear resistance of Al-3SC-1Yo compared with all other variants, including the base material. In particular, Al-3SC-1Yo secures a 34.15% reduction in CoF than the base material at a higher load of 45 N. This phenomenon reflects the excellent wear-resistance nature of Al-3SC-1Yo than the rest of the others.

It is already interpreted from the hardness and wear rate results that the harder asperities of Al-3SC-1Yo resist the adhesion in the first stage of wear and also experience negligible plastic deformation in the second stage of wear (two-body abrasion). The minimal adhesion and plastic deformation ensure the inducement of minimal CoF, thereby acknowledging the improved wear resistance of Al-3SC-1 Yo. Even at a higher load in association with the three-body abrasion wear, Al-3SC-1Yo experiences lower CoF owing to the lesser probability of detachment of asperities to entangle between the surfaces. Even with the comparison of other processed and reinforced coupons, Al-3SC-1Yo records 4.3%, 9%, and 30.18% lesser CoF than Al-2SC-2Yo, Al-4SC-0Yo and Al-1SC-3Yo.

Worn-out surface analysis (ambient temperature wear)

The surface topography of the material after the wear is investigated to comprehend the effect of wear and the response of the material against the frictional load. The post-wear analysis conducted through SEM and EDS facilitates the comprehensive scientific understanding of the wear nature and the probable development of an oxide layer, to act as a lubricant layer.

However, the increased hardness due to the dynamic recrystallisation and hard particle reinforcement, Al-3SC-1Yo, safeguards the surfaces from adhesion wear, even at a higher load of 45 N. The deeper wear tracks with a lesser and higher number of detached asperities are seen in Fig. 11a, b for the base material. The mentioned micrographs explore the two body-abrading wear mechanisms. The effect of the three-body abrasion mechanism is clearly pictured in Fig. 11c. The poor strength base material fails miserably at two body abrasions, leaving more detached debris. Consequently, the more detached debris entangled between the coupon’s surface and the counter disc’s surface accelerates the three-body abrasion. The intense abrading action has ploughed the surface to form deep grooves shown in Fig. 11c. Hence, the base material records higher wear loss. In contrast, minimal wear at a higher load is recorded for Al-3SC-1Yo, even under the three-body abrasion. The resilient nature against wear is incurred not only due to the amplified strength and hardness attained after FSP and reinforcements but also due to the formation oxide layer. The experimentally proven high strength and hardness Al-3SC-1Yo records minor detached debris, with comparatively lighter wear tracks than the parent material as shown in Fig. 12a. At higher loads, the two-body abrading action induces a deeper wear track with ejected debris as depicted in Fig. 12b and frictional heat generated due to the severe abrasion, which causes the oxide layer formation. The oxide layer shown in Fig. 12c acts as a tribo layer, which subsides the effect of three-body abrasion, causing Al-3SC-1Yo to be rigid enough against wear to lose less material.

High-temperature wear analysis

The wear rate observed during the high-temperature wear analysis, by varying the temperature, is depicted in Fig. 13a–c. The cumulative wear rate observed at every incremental 0.5 km of sliding distance for all materials at three different temperatures is illustrated in Fig. 13d. The wear test was carried out at a constant normal load of 45 N, the highest load during ambient temperature testing. It is vivid from the wear rate results of room and high temperatures that the wear rate recorded at high-temperature environments is significantly higher (nearly 90% more wear) in ambient environments, despite the process and reinforcement benefits. In the ambient environment, the wear mechanism is driven by adhesion-transformed abrasion wear, whereas in a high-temperature environment, the complete wear mechanism is governed by the abrasion only. It is well known that the material becomes softer at high temperatures owing to the diffusion of molecular bonding.

Eventually, the sliding contact of the hard counterpart with the softer substrate under a higher load of 45 N, causes a significant abrasion action. This continuous abrading action under the higher load instigates the more pronounced wear. However, the effect of temperature has been experienced during experimental observations, with noticeable changes in the wear rate according to the change in temperature. From the wear rate plots available in Fig. 13a–c. the wear progression is more pronounced as the temperature increases. The quantitative comparison between Al-3SC-1Yo (declared to be more wear-resistant under ambient environment) and base material Al-5052 at three distinct temperatures manifests that Al-3SC-1Yo variant acquired a considerable wear-resistant to the scale of 57.88%, 3.57% and 14.05% than the base material at 75 °C, 150 °C and 150 °C, correspondingly. It is well comprehended from the comparison that the degree of wear resistance declines as the temperature amplifies. At a low temperature of 75 °C, escalated wear resilience is attributed to the formation oxide layer, which acts as a protective layer to prevent material loss. In parallel, as the temperature increases, the formation of the oxide layer also increases despite the wear being more activated because of brittle failure of the thicker oxide layer. The thermal mismatch between the reinforcements and base material at elevated temperatures prompts the thermal stress, which in turn leads to the spalling of the oxide layers. The fractured oxide layers pave the way to expose the softer FSPed composite to the harder counter-disc, hence the wear is exacerbated. The benefits of reinforcement are no longer in leveraging the wear resistance, as hard filler particles start to lose their bonding at high temperatures, hence the activewear is witnessed. However, contradictory findings were reported by the researcher60, when they compared the room and elevated-temperature tribological study of Al-Si alloy and Al-Si-graphite composite. The report highlighted the improved wear resistance as the temperature increases up to 250 °C, and validated the existence of a glaze layer supplemented by the sintering effect of worn-out debris at high normal and temperature load. Moreover, the base alloy involved in the study was Al-Si alloy which had a higher red-hot temperature (570 °C). Since the operating wear temperature was 250 °C, less than half of the red-hot temperature, the softening of the asperities was impossible, hence the developed glaze layer facilitated the reduction in wear. In contrast, the present study involves Al-5052 whose red-hot temperature is 270 °C, and whose operating temperature is nearly 90% of its red-hot temperature. As a result, the asperities experience complete softening which attracts more wear loss as the oxide layer gets fractured.

Figure 14a–d expresses the distribution of the coefficient of friction availed from the experiments conducted at three distinct temperatures under a constant normal load. Since the signature property of friction, CoF, is a dependent entity of frictional force and temperature, the changes in temperature also affect the magnitude of the friction. A similar trend of wear progression is mimicked in the CoF observation since the increasing CoF index with the increase in temperature. The quantitative comparison of the CoF of wear-resistant Al-3SC-1Yo variant and base material explores a steady improvement in the CoF index of Al-3SC-1Yo to the magnitude of 14%, 3.46% and 5%, than that of the base material at 75 °C, 150 °C and 225 °C, respectively. The erosion in the CoF index concerning the temperature is attributed to the more pronounced adhesion effect due to the severe plastic deformation supplemented by the softening of the material at higher temperatures. Further, the direct contact of both surfaces, supplemented by the spalling of oxide layers, accelerates the contact area, thereby promoting the frictional force, hence, the CoF escalates.

Worn-out surface analysis (high-temperature wear)

The post-worn-out surface analysis is conducted for all the FSPed specimens subjected to high-temperature wear. The macro images of the worn-out pins at three different temperatures are shown in Fig. 15a–c. The micrograph analysis aims to comprehend the nature of oxide layer formation and its performance against temperature and sliding load. The worn-out surface micrographs of the base material at low and high-temperature ranges are depicted in Fig. 16a, b respectively.

The noticeable damage to the surface of the parent material at both temperatures is witnessed in the results. At 75 °C, the significant wear tracks are visible along with the oxide layer. The unreinforced base material behaves more softly at this temperature; hence, it leads to sizable wear tracks appearing. At 225 °C, oxide layer formation is higher despite the wear loss that occurred owing to the spalling of oxide layers. The broken pieces of oxide layers, along with the exposed metal surfaces, are visible in Fig. 16b. The existence of the oxide layer is authenticated through EDS results depicted in Fig. 17a, b. The deeper wear marks on the metal-to-metal contact region, supplemented by the breakage of the oxide layer, pose a higher wear loss. The higher wear loss recorded for the base material is not only due to the failure of the oxide layer but also due to the absence of reinforcement to strengthen the matrix.

The performance of the oxide layer of Al-3SC-1Yo at both low and high temperatures is exposed through the worn-out micrograph shown in Fig. 18a, b. At 75 °C, Al-3SC-1Yo experiences less wear than the base material owing to the minimally fractured oxide layers. The micrographic comparison of base material and Al-3SC-1Yo affirms the noticeable abraded oxide layer and subsequent wear tracks present in base material, whereas milder wear tracks for Al-3SC-1Yo. At 225 °C, the wear rate of Al-3SC-1Yo is comparatively higher than its wear rate at room temperature and lower than that of Al-5052 at high temperature. The thicker and more distinct oxide layer formation than the Al-5052, due to the existence of reinforcements, is found to be the root cause for the minimal wear than the base material. However, more damaged oxide protective layers are witnessed for Al-3SC-1Yo at 225 °C, which acts as a catalyst to boost the wear rate by exposing the metal-to-metal contact. Hence, more wear is recorded than the ambient condition.

Measurement of wear progression

The comprehensive validation of wear progression of wear-resistant Al-3SC-1Yo and base material at both ambient and high-temperature environments, subject to higher physical and thermal load, respectively, is done through the measurement of surface roughness and is depicted in Fig. 19a–d.

The surface roughness results uphold the experimental findings of a higher wear rate at high temperatures than in the ambient environment. The extreme conditions of both physical and thermal loads are considered for the validation. The surface texture also expresses that 90% of the additional surface irregularities are observed for the specimens pertinent to the high-temperature environment than the room temperature, which is highly concurrence with the comparative experimental wear report between the high and room temperature wear study.

Conclusions

The exhaustive wear study conducted at both ambient and room temperature for the hybrid SiC-Y2O3 reinforced aluminium composite processed through FSP to highlight the material for the potential replacement of components involved in the automobile sector draws the following scientific conclusions.

-

The microstructure study and grain size observation indicate that a finer microstructure is developed in the nugget zone with a smaller grain size. Coarser and zero-grain refinement have been observed from TMAZ and HAZ, respectively.

-

Hardness results comprehend the higher hardness achieved by the Al-3SC-1Yo variant, providing the higher hardness peaks are reflected in the nugget zone. In particular, the Al-3SC-1Yo variant FSPed composite is 50% harder than the base material, which signifies the dual factor grain refinement: Y2O3 inclusion and dynamic recrystallisation.

-

The room temperature wear examination confirms the wear mechanism is driven in three successive modes: adhesion, two-body abrasion and three-body abrasion

-

The presence of oxide layers safeguards the materials at low temperatures, and on the other hand, their failure attracts the metal-to-metal contact, which leads to exacerbating the wear at high temperatures.

-

The post-wear surface morphology assessment reveals ejected debris and broken oxide layers in room and high-temperature environments, respectively.

-

The comprehensive wear study in both environments declares the supremacy of the Al-3SC-1Yo variant in showcasing the wear resistance among all other variants, including the base material.

-

The idea of retarding the oxide formation with the inclusion of Y2O3 is partly succeeded, but the higher level of inclusion of the same draws the difficulty of agglomeration.

-

The intensity of the wear progression at high-temperature wear for the base material and wear-resistant variant has been authenticated through surface roughness measurement.

-

The multi-fold wear resistance improvement recorded for the FSPed composite rather than the base material paves the way to represent the material for automobile component replacements.

Data availability

The data involved in the findings of the result will be shared by the corresponding author based on reasonable request.

References

Patel, M. et al. Lightweight composite materials for automotive—A review. Carbon 1(2500), 151 (2018).

Agarwal, J. et al. Progress of novel techniques for lightweight automobile applications through innovative eco-friendly composite materials: A review. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 33(7), 978–1013 (2020).

Bulei, C., Stojanovic, B. & Utu. D. Developments of discontinuously reinforced aluminium matrix composites: Solving the needs for the matrix. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2212(1), p. 012029, IOP Publishing. (2022)

Sharma, S. K. et al. Progress in aluminum-based composites prepared by stir casting: Mechanical and tribological properties for automotive, aerospace, and military applications. Lubricants 12(12), 421 (2024).

Tenali, N., Ganesan, G. & Babu, P. An investigation on the mechanical and tribological properties of an ultrasonic-assisted stir casting Al-Cu-Mg matrix-based composite reinforced with agro waste ash particles. Appl. Eng. Lett. 9(1), 46–63 (2024).

Milojević, S. & Stojanović, B. Determination of tribological properties of aluminum cylinder by application of Taguchi method and ANN-based model. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 40(12), 571 (2018).

Krstić, J. et al. Application of metal matrix nanocomposites in engineering. Adv. Eng. Lett. 3(4), 180–190 (2024).

Babic, M. et al. Wear properties of A356/10SiC/1Gr hybrid composites in lubricated sliding conditions. Tribol. Ind. 35(2), 148–154 (2013).

Gajević, S. et al. Optimization of dry sliding wear in hot-pressed Al/B4C metal matrix composites using Taguchi method and ANN. Materials 17(16), 4056 (2024).

Mellor, B. G. Surface Coatings for Protection Against Wear (Woodhead Publishing, 2006).

Bakhtiari, M., Fayazi Khanigi, A. & Farnia, A. Improving the wear properties of AISI4130 steel using laser surface hardening treatment. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.. 48(9), 11801–11818 (2023).

Chenrayan, V. et al. Effect of powder composition, PTAW parameters on dilution, microstructure and hardness of Ni–Cr–Si–B alloy deposition: Experimental investigation and prediction using machine learning technique. Heliyon 10(16), e36087 (2024).

Komarov, P. et al. Wetting behavior of wear-resistant WC-Co-Cr cermet coatings produced by HVOF: The role of chemical composition and surface roughness. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 30, 285–303 (2021).

Regev, M. & Spigarelli, S. A study of the metallurgical and mechanical properties of friction-stir-processed cu. Metals 11(4), 656 (2021).

Yan, H. et al. Effect of shot peening on the surface properties and wear behavior of heavy-duty-axle gear steels. J. Market. Res. 17, 22–32 (2022).

Zhou, Z.-Y. et al. Research on the mechanism of the two-dimensional ultrasonic surface burnishing process to enhance the wear resistance for aluminum alloy. Friction 12(3), 490–509 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Research on the mechanism of NiCrBSi-WC/Co coatings wear resistance improvement by low-energy laser shock peening. Tribol. Int. 199, 109957 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Microstructure and wear resistance property of laser cladded CrCoNi coatings assisted by ultrasonic impact treatment. J. Market. Res. 22, 853–864 (2023).

Raza, A. & Kumar, S. A critical review of tool design in burnishing process. Tribol. Int. 174, 107717 (2022).

Meng, T. L. et al. Grinding-and robotic hammer peening-induced modifications in the near-surface regions of laser-cladded Inconel 718 coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 489, 131130 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. Effects of in-process cryocooling on metallurgical and mechanical properties of friction stir processed Al7075 alloy. Mater. Charact. 144, 440–447 (2018).

Raaft, M. et al. Microstructural, mechanical and wear behavior of A390/graphite and A390/Al2O3 surface composites fabricated using FSP. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 528(18), 5741–5746 (2011).

Patil, N. A., Pedapati, S. R. & Marode, R. V. Wear analysis of friction stir processed AA7075-SiC-graphite hybrid surface composites. Lubricants 10(10), 267 (2022).

Rafi, S. M. et al. Synergistic effect of FSP and TiB2 on mechanical and tribological behavior of AA2024 surface composites. J. Tribol. 145(11), 114501 (2023).

Vanani, B. B. & Abdollahzadeh, A. Fabrication of reinforced Al–Mg composite by TiC particles via FSW: Microstructure and tribology study. J. Market. Res. 30, 6787–6801 (2024).

Abdelhady, S. S., Elbadawi, R. E. & Zoalfakar, S. H. Investigation of the microstructure, mechanical and wear performance of friction stir-processed AA6061-T6 plate reinforced with B4C particles surface composite. J. Compos. Mater. 57(14), 2297–2310 (2023).

Mishra, M. et al. Microstructural and mechanical studies of multi-walled CNTs/Mg composite fabricated through FSP. J. Compos. Mater. 55(22), 3023–3033 (2021).

Nathan, S. R. et al. Investigations on microstructure, thermo-mechanical and tribological behavior of graphene oxide reinforced AA7075 surface composites developed via friction stir processing. J. Manuf. Process. 90, 139–150 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. A review on microstructures and properties of graphene-reinforced aluminum matrix composites fabricated by friction stir processing. J. Manuf. Process. 68, 126–135 (2021).

Singh, A., Sharma, S. K. & Batish, A. Microstructure and mechanical behavior of coal-derived reduced graphene oxide reinforced AA7075 fabricated via friction stir processing. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 108973 (2024).

Patel, S. K. et al. Microstructural, mechanical and wear behavior of A7075 surface composite reinforced with WC nanoparticle through friction stir processing. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 276, 115476 (2022).

Patel, S. K. et al. Microstructural, mechanical and wear behavior of A7075 surface composite reinforced with WC and ZrSiO4 nanoparticle through friction stir processing. J. Manuf. Process. 71, 85–105 (2021).

Kumar, T. S. et al. A study on microstructural, mechanical properties, and optimization of wear behaviour of friction stir processed AZ31/TiC composites using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 18729 (2024).

Kaya, N. et al. Effect of process parameters of Al5083/SiC surface composites fabricated by FSP on microstructure, mechanical properties and wear behaviors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 315, 128991 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Impact of multiple FSP passes on structure, mechanical, tribological and corrosion behaviors of AA6061/316 stainless-steel reinforced Al matrix composites. Surf. Coat. Technol. 447, 128801 (2022).

Akbari, M., Asadi, P. & Asiabaraki, H. R. Investigation of wear and microstructural properties of A356/TiC composites fabricated by FSP. Surf. Rev. Lett. 29(10), 2250130 (2022).

Bharti, S., Ghetiya, N. D. & Dutta, V. Investigating microhardness and wear behavior of Al5052/ZrO2 surface composite produced by friction stir processing. Mater. Today Proc. 44, 52–57 (2021).

Chittoriya, B. S., Jayant, A. & Kumar, R. Effect of multipass FSP and (SiC + TiB2) nanoparticles on the mechanical and metallurgical characteristic of the hybrid metal matrix composite. SILICON 15(18), 7927–7941 (2023).

Boopathi, S. et al. Friction stir processing of boron carbide reinforced aluminium surface (Al-B4C) composite: Mechanical characteristics analysis. Mater. Today Proc. 50, 2430–2435 (2022).

Gupta, R. & Thakur, L. Influence of micro-sized Al2O3 particles on mechanical and wear performance of an AA7075-Al2O3 composite coating developed by friction surfacing. Int. J. Interact. Design Manuf. IJIDeM 18(8), 5583–5597 (2024).

Bharti, S., Ghetiya, N. D. & Patel, K. M. A review on manufacturing the surface composites by friction stir processing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 36(2), 135–170 (2021).

Natarajan, P. et al. The effect of SiC and Y2O3 inclusion on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al 5052 composite fabricated through friction stir process. Heliyon 11(1), e41665 (2025).

Yao, G. et al. Excellent performance of W-Y2O3 composite via powder process improvement and Y2O3 refinement. Mater. Des. 212, 110249 (2021).

Shapiro, I. et al. Effects of Y2O3 additives and powder purity on the densification and grain boundary composition of Al2O3/SiC nanocomposites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 29(9), 1613–1624 (2009).

Asadi, P. et al. Effects of SiC particle size and process parameters on the microstructure and hardness of AZ91/SiC composite layer fabricated by FSP. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 20, 1554–1562 (2011).

Hashmi, A. W. et al. Mechanical properties and microstructure evolution of AA6082/sic nanocomposite processed by multi-pass FSP. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 75(8), 2077–2090 (2022).

Bouaeshi, W. & Li, D. Effects of Y2O3 addition on microstructure, mechanical properties, electrochemical behavior, and resistance to corrosive wear of aluminum. Tribol. Int. 40(2), 188–199 (2007).

Guo, Y. P. et al. Effect of rare earth Y2O3 on the corrosion and friction properties of Al2O3 ceramic coatings prepared via microarc oxidation. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 15(8), 7682–7692 (2020).

Macerl, M. et al. Microstructure and properties after friction stir processing of twin-roll cast Al–Mn–Cu–Be alloy. Crystals 12(5), 630 (2022).

Sharma, V., Prakash, U. & Kumar, B. M. Surface composites by friction stir processing: A review. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 224, 117–134 (2015).

Chenrayan, V. et al. Tribological performance of TiB2-graphene Al 7075 hybrid composite processed through squeeze casting: At room and high temperature. Tribol. Int. 185, 108486 (2023).

Vaishnav, V., Kumar, R. P. & Venkatesh, C. Influence of nano MoS2 particle on the mechanical and tribological properties of Al-TiB2-Gr hybrid composite. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 36(2), 857–867 (2022).

Chenrayan, V. et al. Frictional stability of pumice-reinforced lightweight magnesium composite in ambient and elevated temperature environments. J. Market. Res. 32, 3465–3475 (2024).

Hansen, N. Hall–Petch relation and boundary strengthening. Scr. Mater. 51(8), 801–806 (2004).

Shekhar, C., Wani, M. & Sehgal, R. Fabrication and self-lubricating tribological characterisation of Cu–Ni/TiC/CaF2 composite for railway switch slide baseplate. Wear 526, 204890 (2023).

Shekhar, C. et al. Recent progress in particulate reinforced copper-based composites: fabrication, microstructure, mechanical, and tribological properties—A review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 27(2), 2401748 (2025).

Shekhar, C. et al. A novel ceramic reinforced metal matrix composite (Cu–Ni/TiC–CaF2): Fabrication, microstructure, mechanical and tribological characterization. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 56, 1–27 (2025).

Narimani, M., Lotfi, B. & Sadeghian, Z. Evaluation of the microstructure and wear behaviour of AA6063-B4C/TiB2 mono and hybrid composite layers produced by friction stir processing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 285, 1–10 (2016).

Arora, H., Singh, H. & Dhindaw, B. Wear behaviour of a Mg alloy subjected to friction stir processing. Wear 303(1–2), 65–77 (2013).

Rajaram, G. et al. Studies on high temperature wear and its mechanism of Al–Si/graphite composite under dry sliding conditions. Tribol. Int. 43(11), 2152–2158 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their acknowledgement to the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH-Research Excellence For REgion Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Large Research Group Project under the grant number RGP.2/198/46. The authors thank the management of Alliance University, Bengaluru, for their extended support in demonstrating the research work successfully.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C : Conceptualization, writing original draft, K.S: Methodology, validation, P.N: Software, V.R.B &V.T: Supervision, A.A: Data curation, J.P & M.N.B : Funding aqcuisistion, M.E.S: Writing—reviewing & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chenrayan, V., Shahapurkar, K., Natarajan, P. et al. Wear behaviour of hybrid ceramic reinforced FSP surface composite at varying temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 37454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21162-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21162-8