Abstract

This research presents a new approach of a fractal model to magnetic data within a Geographic Information System (GIS) environment. We utilized data acquired by an Iranian-made geophysical instrument, equipped with both lower and upper sensors, from the Baba-Ali iron ore deposit in western Iran. The Concentration-Area (C-A) fractal method was employed for data modeling. Initially, data from the lower and upper sensors were independently interpolated using the indicator kriging method within the GIS environment, generating respective raster maps. These interpolated datasets then underwent C-A fractal modeling. This process delineated four distinct classes within the data, allowing for the determination of their corresponding geophysical threshold values and the creation of magnetic field intensity maps for each sensor’s data. Subsequently, the discrepancy between these two magnetic field intensity maps was calculated within the GIS environment to derive the final dataset. At this stage, a grid of 1.65 × 1.65 square meters, comprising 80,925 data points, was generated. These final data were then subjected to a second round of C-A fractal modeling to characterize their fractal behavior. This analysis revealed five distinct data clusters in the C-A plot. The initial three clusters were interpreted as representative of the geophysical background or the first phase of mineralization. In comparison, the subsequent two clusters were attributed to anomalous values or a second phase of mineralization. This enabled the determination of a final threshold value. The resulting geophysical anomaly map demonstrates that fractal modeling of magnetic data in a GIS environment, by effectively discerning fractal patterns within geophysical datasets, offers a highly effective approach for optimizing the identification of geophysical anomaly zones and suggesting exploratory drilling targets. Specifically, a discrepancy in Earth’s magnetic field intensity between the lower and upper magnetic induction (MI) sensors equal to or exceeding 15,548 nT was identified as indicative of an anomaly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Applying Geographic Information System (GIS) capabilities in the analysis of geophysical data can significantly enhance the performance of various methods for separating geophysical anomalous zones1. In geophysical exploration, the core objective is to employ appropriate data analysis techniques to identify drilling targets effectively. Therefore, selecting the most suitable data analysis method is of paramount importance to reduce costs in subsequent stages of exploration operations2,3,4,5. The primary objective of this research is to apply the Concentration-Area (C-A) fractal model to geomagnetic data with the aid of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). The C-A fractal method is a structural technique that leverages the fractal properties of exploration data distribution to separate anomalous zones. This method was initially introduced by Cheng et al. for the separation of anomalous geochemical samples6,7,8. Fractal or multifractal properties were defined by the self-similarity of an element’s geochemical distribution in geological units9. Some research work has been done on fractal modeling of exploration data related to iron ore deposits10,11. The distribution of geophysical data, particularly geomagnetic data, may support this. Fractal features may originate from a variety of geological processes, including mineralization, tectonics, metamorphism, and petrogenesis. These geological occurrences may result in an increase in the fractal dimension and the depletion or enrichment of elements within the rock units, which could alter their geophysical characteristics. Therefore, these changes can be used in the detection and isolation of geophysical anomalies. Variogram analysis, the Area-Perimeter relation, the Concentration-Area relationship, and the Concentration-Distance model can all be used to calculate the fractal dimension6,12,13,14,15. In recent decades, a variety of structural techniques, especially fractal techniques, have been developed for modeling and interpreting geophysical data to identify potential areas; the majority of this research has been done on geomagnetic data3,4,7,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Statistical distribution of geophysical data, especially the frequency of values, is taken into consideration in the majority of the statistical techniques mentioned2,20,22,23, and25. The core challenge in these methods lies in effectively utilizing them with two distinct datasets: lower and upper sensor geomagnetic data. In this project, we have addressed this problem for the first time by using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) within ArcGIS 10.2 software for the C-A fractal model. This integration has significantly streamlined the application of the C-A method for analyzing geophysical data. This novel approach allows us to minimize errors while applying practical methods for separating geophysical anomalies, ultimately improving the results obtained in metallic prospects.

Study area and geology

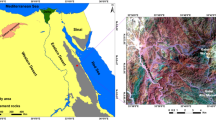

The study area is situated 35 km northwest of Hamedan, west of Iran’s Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, which includes the Almagholagh batholith near the Baba-Ali iron ore deposit (Fig. 1). A geological map around the Baba-Ali iron mine is also shown in Fig. 1. The Limy Oligo-Miocene formations, Schists, and Sonqor series are the three primary lithological units, with corresponding geological ages of the Jurassic and Triassic-Jurassic. The Sonqor series includes a volcano-sedimentary sequence. Andesitic tuff, schistose alternation, and limy units with interbedded metamorphosed spilitic volcanic rocks are all included in this succession26. Between the dioritic and quartz syenite rocks, the Baba-Ali skarn magnetite deposit is one of two major volcanic-sedimentary and intrusive sections that make up the Baba-Ali area. Limy formations and the Sonqor Series are both part of the volcanic-sedimentary sector, which has ages of Oligo-Miocene and Triassic-Jurassic, respectively27,28,29,30.

Methodology

Data acquisition

Two MI magnetometer setups and gradiometry sensors were utilized for the magnetic survey5. The MI sensor’s specifications were thoroughly examined by31. Together with the profile survey, the two sensors were maintained vertically at a distance of about one meter. Additionally, we aim to maintain the bottom sensor’s distance from the ground at about one meter. The profile used for this measurement had an offset of roughly 50 m. The MI magnetometer continually samples at a rate of 1 Hz. As a result, both the profiles and the walking pace affect the survey’s in-line sampling rate. After correcting for the diurnal impact, the raw data from the two sensors - the upper and lower sensors - were smoothed. The deposit is being extended in a W-E direction. Therefore, the N-S direction with the most significant changes is chosen to conduct the survey.

Geological map and geographical location of Baba-Ali exploration area (Modified from5.

Eight survey profiles, totaling approximately 1.06 km in length, are displayed in Fig. 2. We did not apply the diurnal correction, as our focus was solely on the discrepancy between the lower and upper sensors. Given the 40 Hz sampling rate, we obtained a sufficient number of data points to remove the noise effectively. Therefore, we applied a simple low-pass filter using a moving average. There are 8307 measurement samples and profiles in all. The C-A fractal method is more applicable to data with regular grids, which is consistent with the nature of magnetic data. To completely eliminate this limitation, interpolation is performed on the raw data.

Concentration-area fractal model

Determining the fractal dimension of geophysical phenomena is the foundation of this model. A smooth model of the element’s spatial distribution is offered by contour maps. The area shrinks as the concentration or value of the geomagnetic variable increases if A(ρ) comprises a contour with a concentration value of ρ (here is the geomagnetic variable). The following is the concentration-area model used to define anomalies and the geophysical background:

Where \(\:A\left(\rho\:\right)\) is the area where the geomagnetic variable value is greater than a contour with ρ, and D represents exponential features. By counting the cells in the variables’ raw data, A(ρ) can be found. The grid and the study area’s cells overlap in this manner. The number of cells (multiplied by the cell’s area) at values greater than the area is the A(ρ) region for a given area. Anomalies (values related to mineralization processes) in geophysical exploration represent distinct power functions in comparison to the background value.

To put it another way, the anomaly will be distinguished from the background by its distinct fractal dimension6,12, and32. The fractal dimension of the geophysical variable is increased when geophysical anomaly values are present. The threshold values for distinguishing anomalous regions from the background were determined by comparing the fractal dimensions of the background and anomalous dataset. The threshold values in this research were calculated using the area-concentration fractal approach. The different stages of fractal modeling of the Earth’s magnetic field data on the Baba-Ali iron ore deposit in the GIS environment are presented in the form of a flowchart in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

For implementing the concentration-area (C-A) fractal model on the lower and upper MI sensor magnetic field intensity data, first, a grid net of 1.65 × 1.65 m2 was considered to estimate the data by the indicator Kriging method. Data interpolation was performed using methods indicator kriging (IK), and minimum curvature. Very similar results were obtained. However, since the results of method IK were smoother and more continuous, the estimated data of this method were ultimately selected for fractal modeling and preparation of final maps. In order to justify the spatial resolution of the grid in terms of location, it was necessary to select the grid spacing optimally, and the most optimal spacing was 1.65 × 1.65 m2. Considering the raw data spacing, spacing greater than 1.65 increased uncertainty and reduced the accuracy of the work, and spacing smaller than that did not change the resolution and accuracy of the map. There were 7200 grid nets in all, where data interpolation was done. The aforementioned interpolation approach was used for raw data in order to produce this interpolation. Then, concentration-area logarithm plots were generated for the estimated data. In this instance, these diagrams display varying dimensions for various populations. Table 1 displays the separated populations’ fractal dimensions from Fig. 4. For every MI sensor, the concentration-area fractal graphs display four significant populations. From lower to higher magnetic field intensity populations, fractal dimensions often grow. The different linear trend could be interpreted as several fractal dimension or multi-population. Low fractal dimensions are associated with syngenetic components of geological activities and are not related to the mineralization phase. However, high fractal dimensions are associated with mineralization and are consistent with epigenetic components. These changes are seen at the boundary of the second and third populations. Anomalous populations are characterized by high fractal dimensions and strong magnetic field intensities. The background population, which has not been impacted or has been less affected by these activities, is considered to have low fractal dimensions.

The C-A fractal model was used for calculating the value of the threshold. The first and second fractal dimensions (or fractal populations) were considered background populations, while the third and fourth populations were regarded as geomagnetic anomalies or metal mineralization populations. Therefore, the boundary between the second and third populations was considered as a threshold value. The estimated threshold values for each dataset are presented in Table 1.

The contour maps of the iso-magnetic field intensity values showed the anomalous areas. Using ArcGIS version 10.2, a kriging interpolation technique with the proper pixel size was employed to produce these raster maps. By considering the distribution of the Earth’s magnetic field intensity, anomalous areas were detected. This makes it feasible to recommend possible areas for the continuation of exploration activities in addition to predicting the drilling points. The map of the Earth’s magnetic field intensity for the lower and higher MI sensors is displayed in Fig. 5a and b, respectively. These statistics also show the extent of the ore body. A color gradient from dark blue to red represents the strength of the magnetic field in the area. In the research area, blue denotes the Earth’s magnetic field’s lowest intensity, while red denotes its maximum. The map of the possible geomagnetic regions for the research area was presented based on the threshold values for the readings of the lower and upper MI sensors that were determined using the C-A fractal model. These regions are displayed in Fig. 5c and d. On the maps, the anomaly area derived from the lower MI sensor is larger than the one derived from the higher MI sensor.

The gradient of the Earth’s magnetic field is depicted in Fig. 6 after these maps are subtracted using the ArcGIS program version 10.2. In addition to displaying the interpolated data grid on a section of the raster map of the study area, this figure illustrates the difference in Earth’s magnetic field intensity as measured by lower and upper MI sensors. This figure represents the gradient of the values, which was obtained by deducting the sensor maps.

To identify geomagnetic anomalous zones, two distinct scenarios were investigated. The first scenario involved defining the final threshold value for the anomaly map as the difference between two threshold values obtained from the lower and upper sensors. This approach yielded a final threshold value of 12,219 nT. However, the potential anomalous areas delineated using this threshold proved to be unreasonable. It accounted for only 9% of the study area as background and over 91% as potential anomalous zones. Consequently, this scenario was deemed unacceptable.

The second, more robust scenario for identifying anomalous samples employed a C-A fractal model applied to the discrepancy of the lower and upper MI sensors data. This approach necessitated the extraction of kriging grid data and the generation of a point layer within an ArcGIS environment from the raster map depicting the magnetic field intensity distribution in the area. Figure 6 illustrates the kriging data grid generated in the ArcGIS software, specifically for the northeastern part of the study area. The generated dataset comprised 80,925 points with a grid cell size of 1.65 m×1.65 m. Following the preparation of the data in an Excel file, the concentration-area fractal model algorithm was implemented, and the final C-A plot was generated (Fig. 7).

Five distinct fractal populations were identified on this plot. The fractal dimensions for each population are presented in Table 1. Within this model, populations one to three were classified as the background population, while populations four and five were designated as the anomalous populations. Therefore, the boundary between the third and fourth populations was identified as the final threshold value. Subsequent calculations determined this value to be 15,548 nT. The resulting map illustrating the geomagnetic anomalous zones in the region is presented in Fig. 8. Notably, a significant anomaly is observed in the central part of the study area, exhibiting a northwest-southeast trend. This scenario considered about 10% of the total geomagnetic data collected from the region as anomalous values.

Validation of the model

The method was validated by comparing its results with the results of the geomagnetic surveys of the ground Baba-Ali iron deposit in 199828 (Fig. 9a), Shahsavani and Vafaei’s magnetic gradiometry results in 20205 (Fig. 9b), and one other anomaly separation method (U-spatial statistics) published by Seyedrahimi-Niaraq et al., 20221 (Fig. 9c). The C-A fractal model is presented alongside these findings in Fig. 9d for improved validation. The findings indicate a possible zone in the study area’s west and center, which then continued to the NW-SE trend with less unusual intensity. On this same mineralization trend, two exploration trenches with a northeast-southwest trend were proposed in local surveys. The findings of magnetic gradiometry investigations have also verified the location of these anomalies. These results are in perfect agreement with the anomalous zone derived from the C-A fractal model. In addition, the mineralization process is also clearly detected by the proposed method (Fig. 9d). Compared to the U-spatial statistic method, the proposed model shows the same trend in the center and northwest of the region. However, the mineralization trend introduced in the southeast of the region by the U-statistic method is eliminated by the C-A fractal method, which is more consistent with field realities. In other words, the C-A model has shown the definite anomaly zones with greater clarity.

Figure 10 illustrates the methodology for identifying magnetic anomaly values, as presented in Figs. 8 and 9c. This chart was generated using the output data from the NW-SE mineralization trend depicted in Fig. 9c. These zones are characterized by values exceeding 15,548 nT. Values above this threshold line are considered anomalous and are delineated by these values. This method involves calculating a magnetic threshold value for the study area. By doing so, it not only highlights variations in magnetic field intensity but also more definitively identifies anomalous zones on the anomaly map (Fig. 8) where further exploration is warranted. This approach, using the proposed approach, can thus help prevent unnecessary expenses in subsequent stages of exploration.

Conclusions

A Concentration-Area fractal model was applied to Earth’s magnetic field intensity data from the Alibala iron-ore deposit within a GIS environment. This novel approach yielded significant improvements over previous results. By modeling the output of the raster map data using the fractal C-A fractal model, a magnetic anomaly zone trending northwest-southeast was identified in the center of the study area. This model designated approximately 10% of the surveyed data as magnetic anomalous values. Validation of the model with prior results demonstrated that this new approach, by examining the fractal patterns of geophysical data and suggesting exploratory drilling targets, can be highly effective in optimizing the identification of geophysical anomaly zones (Discrepancy of the Earth’s magnetic field intensity of the lower and upper MI sensors ≥ 15548 nT).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Seyedrahimi-Niaraq, M., Shahsavani, H. & Hekmatnejad, A. Application of U-spatial statistics for separating magnetic anomalies: a case study on the Galali iron ore deposit in Western Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 15(21), 1629 (2022).

Scheiber-Enslin, S., Ebbing, J. & Webb, S. J. An integrated geophysical study of the Beattie magnetic anomaly, South Africa. Tectonophysics 636, 228–243 (2014).

Curto, J. B., Diniz, T., Vidotti, R. M., Blakely, R. J. & Fuck, R. A. Optimizing depth estimates from magnetic anomalies using spatial analysis tools. Comput. Geosci. 84, 1–9 (2015).

Kolokolov, I. V. Spatial statistics of magnetic field in two-dimensional chaotic flow in the resistive growth stage. Phys. Lett. A. 381(11), 1036–1040 (2017).

Shahsavani, H. & Vafaei, S. Magnetic gradiometry with a low-cost magneto-inductive sensor: A case study on Baba-Ali iron ore deposit (Western Iran). J. Appl. Geophys. 177, 104053 (2020).

Cheng, Q., Agterberg, F. P. & Ballantyne, S. B. The separation of geochemical anomalies from background by fractal methods. J. Geochem. Explor. 51, 109–130 (1994).

Afzal, P., Afshar, Z. Z., Khankandi, F. S., Wetherelt, A. & Yasrebi, B. A. Separation of uranium anomalies based on geophysical airborne analysis by using Concentration-Area (C-A) Fractal Model, Mahneshan 1: 50000 Sheet, NW Iran. J. Min. Metall. A: Min. 48(1), 1–11 (2012).

Mahdiyanfar, H. & Seyedrahimi-Niaraq, M. Integration of fractal and multivariate principal component models for separating Pb-Zn mineral contaminated areas. J. Min. Environ. 14(3), 1019–1035 (2023).

Mahdiyanfar, H. & Seyedrahimi-Niaraq, M. Improvement of geochemical prospectivity mapping using power spectrum–area fractal modelling of the multi-element mineralization factor (SAF-MF). Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 22(4), geochem2022-015 (2022).

Sadeghi, B., Moarefvand, P., Afzal, P., Yasrebi, A. B. & Saein, L. D. Application of fractal models to outline mineralized zones in the Zaghia iron ore deposit, Central Iran. J. Geochem. Explor. 122, 9–19 (2012).

Ghasemi, S., Imamalipur, A. & Barak, S. Application of fractal modeling for accurate resources estimation in the Qarah Tappeh copper deposit, NW Iran. J. Min. Environ. 15(4), 1563–1577 (2024).

Yousefi, M. & Carranza, E. J. M. Prediction–area (P–A) plot and C–A fractal analysis to classify and evaluate evidential maps for mineral prospectivity modeling. Comput. Geosci. 79, 69–81 (2015).

Akbari, S., Ramazi, H. & Ghezelbash, R. Using fractal and multifractal methods to reveal geophysical anomalies in Sardouyeh District, Kerman, Iran. Earth Sci. Inf. 16(3), 2125–2142 (2023).

Sadeghi, B. Concentration-area plot. In Encyclopedia of Mathematical Geosciences (169–175) (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Nazih, M., Gobashy, M. M., Khamis, H., El-Sadek, M. A. & Soliman, K. S. Singularity index and multifractal analysis of magnitude magnetic transforms: a new methodology to explore Au mineralization with application to Esh El Mallaha, Egypt. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 11010 (2025).

Spector, A. & Grant, F. S. Statistical models for interpreting magnetic data. Geophysics 35(2), 293–302 (1970).

Keating, P. The fractal dimension of gravity data sets and its implication for GRIDDING1. Geophys. Prospect., 41(8), 983–993. (1993).

Dimri, V. P. Fractal behavior and detectibility limits of geophysical surveys. Geophysics 63(6), 1943–1946 (1998).

Louro, V. H. A. & Mantovani, M. S. M. 3D inversion and modeling of magnetic and gravimetric data characterizing the geophysical anomaly source in Pratinha I in the Southeast of Brazil. J. Appl. Geophys. 80, 110–120 (2012).

Dimri, V. P., Srivastava, R. P. & Vedanti, N. Fractal Models in Exploration Geophysics: Applications To Hydrocarbon Reservoirs, Vol. 41 (Elsevier, 2012).

Allek, K., Boubaya, D., Bouguern, A. & Hamoudi, M. Spatial association analysis between hydrocarbon fields and sedimentary residual magnetic anomalies using weights of evidence: an example from the triassic Province of Algeria. J. Appl. Geophys. 135, 100–110 (2016).

Dimri, V. P. & Ganguli, S. S. Fractal theory and its implication for acquisition, processing and interpretation (API) of geophysical investigation: A review. J. Geol. Soc. India. 93(2), 142–152 (2019).

Sun, T. et al. Fractal-based multi-criteria feature selection to enhance predictive capability of AI-driven mineral prospectivity mapping. Fractal Fract. 8(4), 224 (2024).

Chauhan, M. S., Bansal, A. R. & Dimri, V. P. Scaling laws and fractal geometry: insights into geophysical data interpretations. J. Geol. Soc. India. 101(6), 983–989 (2025).

Srivastava, R. P., Vedanti, N. & Dimri, V. P. Optimal design of a gravity survey network and its application to delineate the jabera-damoh structure in the Vindhyan basin, Central India. Pure. appl. Geophys. 164(10), 2009–2022 (2007).

Barud, J. Geological Map of the Kermanshahan Quad Rangle (1:250,000). Geol. Surv, Iran, Tehran (1975).

Amiri, M. Petrography of the Almouglagh, 231 (in Persian) (Univ. Trbiat-e-Moalem, 1995).

Sabanoor Steel Raw Material Supplying Company (SSRMS Co.). Report of Baba Ali iron mine ground magnetic survey. (1998).

Zamanian, H. Iron Mineralization Related To the Almoughlagh and South Ghorveh Batholiths with Specific Refrence To the Baba Ali and Gelali Deposits (Univ. Pune, 2003).

Zamanian, H. & Radmard, K. Geochemistry of rare earth elements in the Baba Ali magnetite Skarn deposit, Western Iran - a key to determine conditions of mineralisation. Geologos 22, 33–47 (2016).

Regoli, L. H. et al. Investigation of a low-cost magneto-inductive magnetometer for space science applications. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 7, 129–142 (2018).

Seyedrahimi-Niaraq, M. & Hekmatnejad, A. The efficiency and accuracy of probability diagram, spatial statistic and fractal methods in the identification of shear zone gold mineralization: a case study of the Saqqez gold ore district, NW Iran. Acta Geochim. 40, 78–88 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (Research grant number 1404/د/9/1126). The authors would like to thank them for their financial and research support.

Funding

This research was supported the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (Research grant number 1404/د/9/1126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. developed the model and wrote the main manuscript. H.Sh. performed the geophysical surveys and assisted in editing the text and preparing the Figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seyedrahimi-Niaraq, M., Shahsavani, H. Fractal modeling of Baba Ali iron ore deposit geophysical data in western Iran for magnetic anomaly separation in GIS environment. Sci Rep 15, 42949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21197-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21197-x