Abstract

Accurately predicting the fresh properties of self-consolidating concrete (SCC) is critical for enhancing construction efficiency and ensuring robust performance in complex and highly reinforced structures. Traditional experimental testing is time-consuming, costly, and prone to human error. In this study, over 2500 experimental data points were initially collected from 176 published studies to develop a comprehensive and reliable dataset. After rigorous data cleaning and filtering 348 SCC mix designs with complete rheological information were selected for model development. After rigorous data cleaning and filtering the dataset divided into 85% for training and 15% for testing. Five state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) models Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Decision Trees (DT), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests (RF) were developed to predict slump flow (mm) and V-funnel time (s). Model interpretability was enhanced using Shapley Additive explanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) to examine the influence of mix design variables. Among the models, GEP and DNN achieved the highest predictive accuracy with R² values up to 0.957 and 0.950 for V-funnel time (s) and 0.915 and 0.911 for slump flow (mm) respectively. The results highlight the strong potential of advanced ML methods to reliably forecast SCC’s fresh properties, reduce reliance on extensive laboratory testing, and support rapid, data-driven optimization of concrete mixed designs in modern construction practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-consolidating concrete or SCC is an extremely flowable concrete that can flow by its own weight, thereby filling all cavity spaces in molds without vibration. SCC has drawn a lot of attention in current construction because it is efficient in enhancing the efficiency and quality of concrete placing, particularly in complex formwork and highly reinforced zones1. The rheological properties of self-compacting concrete (SCC) include slump flow (mm) (mm), V-funnel time (s), yield stress, viscosity, and flowability. They are particularly relevant to the construction sector, since the concrete is deposited within a construction when it is in the plastic state2.

Conventionally, rheological properties of SCC have been identified by experimental testing, which is time-consuming and comparatively expensive. Recent years have seen the adoption of sophisticated computational methods, including Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Decision Trees (DT), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests (RF), in predicting these properties from mix design parameters and material properties. GEP, an evolutionary algorithm, can represent intricate relationships and provide simply interpretable solutions3. On the other hand, DNN is a sub-branch of ML in which good capabilities for handling large datasets and the learning of nonlinear patterns exist so that it could potentially become a promising tool for the prediction of concrete properties4.

Several machine learning techniques have been used to model SCC workability and rheology. For instance, Nunes et al.5 predicted SCC’s flowability using artificial neural networks, while Zhang et al.6 represented the influence of mix proportions on SCC’s yield stress using GEP. Although promising, further studies must be conducted that will compare the performances of GEP and DNN models for predicting SCC’s rheological properties. These should be integrated since each has its advantage.

The main goal of this study is to design and compare the performance of different machine learning (ML) models Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Decision Trees (DT), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests (RF) to predict the rheological properties of self-consolidating concrete (SCC) with respect to slump flow (mm) and V-funnel time (s). An extensive dataset of 348 SCC mixtures was gathered from published literature, covering a broad variety of mix design parameters.

Rheometer

A rheometer is still a useful instrument in rheological testing; the shear strength of concrete being measured. More importantly, it is very useful in assessing the shear stress as well as flowability under different loading conditions, it is applicable to the study of concrete under conditions of stress like those that occur during placement and compaction.

The technical committee 266-MRP of RILEM has carried out round-robin testing to examine the performance of different rheometers in measuring yield stress and viscosity values in combination with flow behavior of cementitious materials7. Though the operational mechanism is different and the measurement procedure, the overall outcome of this round-robin testing program has proven the notion that the suitability of a rheometer depends upon the conditions and the type of material for which a test is being performed. Therefore, comprehension of the strength and weakness of each instrument will allow characterization with more accuracy and uniformity of the fresh concrete properties in any testing situation. Different types of rheometers given in Table 1.

Factors influencing rheological properties as determined by rheometers

The measurement of rheological properties in cement-based materials depends, among others, on the inherent factors related to the rheometer in use. It comprises calibration, geometric shape, spacing between cylinders, both inner and exterior, and the choice between vane or coaxial geometries, as well as alternative geometries such cone systems. To comprehend the effect of these rheometer-specific Variables are important in cement-based materials for correct characterization8,9.

Several factors affect the measurement of rheological properties, and these are often associated with the design and capabilities of the used rheometer. Some of the important considerations that might affect the reliability and accuracy of rheological measures include:

The importance of calibration in ensuring accurate rheological measurements

For rheological measurements to be reliable, calibration is essential. Calibration is essentially used for perfectly correlating the rheometer’s sensors and the software with proper acquisition of data. The process might be affected by factors such as sensor resolution, long-term stability, and a little bit of calibration methodology used. In practice, different calibration procedures and standards applied may lead to inconsistency in the measurement of rheological properties among different rheometers. Therefore, standard calibration procedures are crucially important in minimizing inconsistencies and maximizing the comparison of measurements.

Impact of rheometer geometric design on rheological measurements

Rheological measurements are greatly influenced by geometric patterns of a rheometer, including the inner and outer cylindrical arrangement or any other structural element. The components’ height, shape, and radius are important factors to consider. Shear rate, shear stress, and flow behavior in examined materials can all be impacted by geometrical variations in the aforementioned factors. Because it affects the velocity gradient, which in turn affects the rheological properties measured, the distance among inside and outside cylinders or simply the distance in other configurations is particularly crucial. A larger gap, for instance, would lead to lower shear stress and possible YS undershooting. Therefore, it is crucial to standardize gap dimensions and reporting to ensure consistency and comparability of rheological data among various rheometers.

Influence of inner cylinder geometry on rheological measurements: Vane vs. coaxial configurations

Vane and coaxial geometries are crucial for identifying inner cylinders, and since each has unique advantages and disadvantages, the best one must be used depending on the application. High torque sensitivity is provided by vane shapes, which are connected to the inner cylinder and are perfect for yield stress (YS) and plastic viscosity (PV). However, when adopting vane designs, the flow near the rheometer walls may be nonuniform, which can restrict their accuracy, particularly for materials that exhibit big particles. Coaxial geometries, on the other hand, guarantee more dependable flow conditions by creating a consistent space between the inner and outer cylinders. Compared to geometries that use vane flow, this design usually lacks torque sensitivity, but it is ideally suited for evaluating the rheological characteristics of highly flowable materials. For more specific applications, there are other arrangements like helical screws or cone systems, but they typically include complications that make it more difficult to determine basic rheological characteristics. Certain results may need specific calibration procedures or be provided in relative units. When selecting a geometry, one must consider the characteristics of the material and the kinds of rheological parameters that are needed, constantly monitoring the advantages and disadvantages of various configurations.

To enable precise and reliable measurement of rheological characteristics in cement-based materials, considerations pertaining to rheometer calibration, geometry, and inner cylinder configuration must be made. The comparability of data between various rheometers will be improved by standardizing calibration procedures with accurate reporting of geometric characteristics, enabling insightful comparisons and a deeper comprehension of the behavior of such materials.

Rheological property prediction

Accurate predictions allow optimized mix designs while minimizing costs and allowing the desired performance to be achieved. Traditional prediction methods are based on empirical relations extracted from extensive laboratory testing. However, the complex and nonlinear factors governing the behavior of Self-Consolidating Concrete demand more advanced predictive methods. It is here that the domain of ML comes into action, with high potential because it can dig deep into complex relationships involved in huge data. Though promising, very few research has investigated the usage of ML to predict rheological parameters.

To predict the interface rheological characteristics of fresh concrete, a combined ML technique of integrating LSSVM with PSO was employed. This work used 142 experimental designs in conjunction with a tribometer for rheological property recording. Furthermore, the fresh properties of the concrete mixtures are not reported. Although the PSO-LSSVM model was strong in predictability, one of its major drawbacks was the limited number of avaiLabel experimental data. The authors suggested that better generalizability of the model would be achieved through higher experimental data accumulation10.

A comparative study is carried out with evolutionary artificial intelligence techniques using the Decision Tree (DT) and the Bagging Regressor (BR) models in predicting rheological properties of fresh concrete9. The use of 140 experimental points could cause some inconsistencies as both experiments were taken using different instruments to determine properties. The 6 input variabels used were cement, water, FA, CA, and Total Powder. The authors reported that the predictions of the rheological properties using ML algorithms are highly promising. Among the BR and DT methods that were tested, BR performed better than DT in terms of predictive accuracy. The statistical sensitivity analysis showed that major influential variables to PV predictions were found to be related to cement and medium-to-coarse aggregates, whereas for Yielding Stress, the greatest impact was identified in the case of small and medium coarse gravels9,10,11. In such instances, they came to use the same database and obtained similar limitations as those noticed in their earlier investigation12.

Several machine learning techniques, such as MLR, RF, DT, and SVM, have been used to predict SCC’s rheological properties10. The 100 results of SCC mixture were based on a prior study. However, it is unclear how the 100 mixtures were gathered since the referenced study only had to work with 59 Self-Consolidating Concrete mixtures except if mortar mixtures were included. The slump flow (mm), V-funnel time (s), and H2/H1 values were considered the input parameters used in this study. It was determined that the DT algorithm was the most effective for predicting yield stress of SCC, while the RF model showed to be the most accurate in predicting the plastic viscosity13,14,15.

A database containing data from several studies examining 170 SCC mixtures was used. It has been considered a major weakness that the database is not uniform, as data have been aggregated from sources with different methods of rheological measurement. The mortar mixtures were the subject of one study, which further adds to the diversity. 4 advanced machine learning techniques were used namely: LightGBM, XGBoost, RF, and CatBoost. Using multiple algorithms would be helpful in reducing some limitations imposed by inconsistent sources, but the findings should be critically analyzed due to inconsistencies reported for a relatively high R213,15,16,17,18,19.

A total number of 348 Self-Consolidating Concrete mixtures were analyzed from 19 published articles using various rheometers. The two methods used are SHAP and PDP used to investigate how the different SCC composition influences the rheological properties of Self-Consolidating Concrete. The model presented very good accuracy for prediction of rheological characterized as SCC, with R² values ranging between 0.93 and 0.98 and an Index of Agreement between 0.92 and 0.99. The investigation done by both SHAP and PDP indicated that the YS and plastic viscosity (PV) were inversely proportional to slump flow (mm), ratio, and segregation rate. However, a positive direct proportion was observed between those factors and time required for the V-funnel time (s)14,15,18,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

There are several gaps evident in research work which mainly pertain to inconsistent source data since most of the work used for the compilation of this dataset has been sourced from different entities that sometimes-used measurement techniques and instruments. This causes inconsistencies and thus reduces the generalizability of results. Secondly, small sample size limits the applicability of the results. Better datasets are required to ensure improved reliability in the conclusions that are obtained. There is also high measurement error, particularly as seen with tribometers, which carries with it values of YS and PV, likely to be unusually high, whose accuracy becomes doubtful. In addition, the unclear origin of some data could also undermine the integrity of the results obtained15. Some studies already have compared different methods, but it would be valuable to conduct a more comprehensive analysis that compares machine learning techniques with conventional statistical techniques and hybrid methods using reliable datasets. More sensitive analyses conducted in detail would help better understand the reliability of the models when applied to various types of concrete and under other conditions. The issues have now been addressed and provided more precise, trustworthy, and broadly applicable findings in prediction of rheological properties for Self-Consolidated Concrete.

Research significance

Various studies have shown that ML models consistently demonstrate powerful predictor abilities for predicting rheological properties of self-compacting concrete. This assesses the viability of using advanced computational methods in the field. Based on selected algorithms, effectiveness of the adopted predictive models can vary. The BR was outperforming DT model in one study while XGBoost was doing exceptionally in another10,16. Besides, the input features of cement type and aggregate characteristics can affect models differently, and understanding which features have the greatest impact on the outcome can guide the design of future experiments. This research marks a paradigm shift in the approach to rheological predictions through use of the five ML algorithm. The article aims to generate more precise, efficient, and holistic predictions that will enhance the model and application processes of Self-Consolidating Concrete. Database creation here-from various research related to concrete and various rheometers-is full of many potentials beyond its academic interest. It would remake the practices and standards within industries, making SCC in construction a source of innovative and optimized change.

Methodology

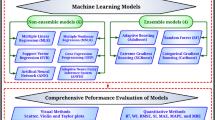

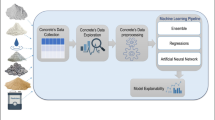

Figure 1 illustrates the overall methodology adopted for predicting the fresh properties of Self-Consolidating Concrete (SCC) using machine learning techniques. The process begins with data collection, after finalized data divided into 15% test set and 85% train set and then followed by a thorough data analysis phase, which includes both descriptive analysis to understand the distribution of variables and a correlation matrix to examine inter-variable relationships. The insights from this analysis guide the model development stage, where five machine learning models Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree (DT), Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Deep Neural Network (DNN), and Random Forest (RF) are trained using the input data. These models are then assessed using various performance metrics, such as R2, Relative Absolute Error (RAE), Mean Percentage Error (MPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). The final output is a comparative analysis of model performance, providing results that inform optimal model selection for accurate and efficient SCC property prediction.

Data collection and cleaning

To use machine learning algorithms to generate the proper prediction models, data collection is the first step. Collection and generation of reliable data for any model is the most tedious task in machine learning75. 2500 SCC mixes were gathered from 176 published studies between 2014 and 2024 to create a complete dataset35,63. In total, there were 2500 raw data points that were initially gathered according to published literature, online databases, and experimental sources. Several filtering procedures were carried out to get quality and consistency of data. The physically unrealistic entries like Water < 50 kg/m3 were dropped off and 154 published studies entries were dropped off. This was followed with deletion of 197 records in which the data was more than 20% missing in key mix parameters, and imputation of the records with minimal incomplete data records with the median of the variable. The detection of the outliers was performed with the help of the Interquartile Range (IQR) technique, which was followed by the removal of values that were further than 1.5 x IQR of the first (Q1) or third quartile (Q3). A heavy dose of special attention was drawn toward those variables that are highly skewed i.e. Admixture and TP, therefore pruning 281 outlier records. Copies and items that were in non-standard units were also standardized. After this sequence of cleaning, the resulting final dataset used in modeling consisted of 348 records of high compatibility mix data and was statistically sound, and unbiased with regards to missing values and extreme values.

Of 176 identified studies, 34 were screened full-text, and 19 matched the inclusion standards, and 348 unique SCC mixes were found after unit harmonization and duplicate elimination. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the inclusion and exclusion of the study 19 papers as shown in Table 2. Rheological characteristics obtained only through empirical testing were not included. Inconsistent entries were identified through data cleaning and removed to ensure dataset integrity. Missing mix components were handled using mean imputation where appropriate. Outliers were detected using the interquartile range (IQR) method and were either removed or capped based on their influence on model performance. The rheological data from each rheometer was normalized using min-max scaling to reduce inter-device variability. Additionally, rheometer type was included as a categorical covariate in the model to account for instrument-specific effects.

Descriptive analysis

Rigorous data standardization and normalization procedures ensure that all features were on a consistent scale79. Important mixture design factors, such as the ingredients’ specific gravity, were noted to calculate derived qualities like paste volume. Rheological and important new properties were collected. Table 3; Fig. 3, which also display the mean, standard deviation, ranges, and minimum and maximum, Skewness and kurtosis values for each parameter, highlight these mixing parameters.

Correlation matrix and data distribution for input parameters

Examining the linear and non-linear correlations between features and outputs is crucial for understanding the interplay within the dataset76. The Pearson correlation matrix provides valuable insights into the linear relationships between various parameters in the dataset74.The two heatmaps Fig. 4a and b illustrate correlation relationships among features in the dataset. In Fig. 4a, Cement and TP exhibit a moderately strong positive correlation (r = 0.53), while Water and CA show a negative correlation (r = -0.31), indicating an inverse relationship. V-funnel time (s) has weak correlations (r < 0.2) with most features, suggesting limited interdependence. In Fig. 4b, Cement and TP maintain a positive correlation (r = 0.45), consistent with Heatmap 1, and Water and CA again show a negative correlation (r = -0.31). Slump flow (mm) has weak correlations, such as with MGS (r = 0.07), reflecting minimal dependency. Across both heatmaps, Pairwise correlations remained below 0.80, suggesting limited risk of severe multicollinearity, although residual multicollinearity among interacting predictors cannot be fully excluded. Cement and TP emerge as influential variables, while V-funnel time (s) and Slump flow (mm) exhibit weaker impacts on the dataset.

Multicollinearity and interdependencies among input features can present challenges in ML modeling. When two or more features are strongly correlated, it becomes difficult for the model to disentangle their individual impacts, potentially leading to overfitting and reduced generalizability. Such issues undermine model accuracy and interpretability, making it harder to assess the unique contribution of each feature. To mitigate these challenges, it is generally recommended that correlations between features remain below 0.80. In this study, the correlations between all feature pairs are below this threshold, minimizing the risk of multicollinearity and enhancing the robustness and interpretability of the models23,25,26,40,41.

The scatterplot matrices visualize pairwise relationships among variables such as Cement (kg/m3), Total Powder (TP) (kg/m3), Fine Aggregate (FA) (kg/m3), Coarse Aggregate (CA) (kg/m3), Water(kg/m3), Admixtures (Adm)%, and Maximum Grain Size (MGS) (mm), and their influence on response variables like V-funnel time (s) Fig. 5a and Slump Fig. 5b. The diagonal plots display the distribution of each variable, while the off-diagonal scatterplots show how each pair of variables is related. Linear trends in the plots indicate strong correlations, while scattered points suggest weak or no relationships. These matrices are valuable for identifying correlations, detecting outliers, and selecting key variables that influence the response variables, providing a quick and comprehensive overview of the dataset’s structure.

Model development

The predictive models for rheological properties of SCC are developed in this research by applying GEP, DNN, DT, SVM and RF. These methods capture unique powers for analyzing intricate and non-linear relationships between input parameters and output properties.

Gene expression programming (GEP)

GEP was used as it combines the strengths of genetic algorithms and symbolic regression to identify explicit mathematical expressions representing the relationship between the mixture design parameters and the target rheological properties. A split of 85% of the dataset for training and 15% as a test set was done and Gene Expression Programming (GEP) model was created with a set of functions based on the equation {+, −, ×, ÷, √, log, exp} The operation used was addition (+), and the training process was stopped when there was no significant improvement (i.e. less than 0.001 reduction in error) in 50 consecutive generations or when the training had reached 1000 generations. The number of chromosomes and genes in the current study were determined using a trial-and-error approach and suggestions from earlier research65,66. These parameters were adjusted until the highest level of accuracy was achieved in the model. Schematic sketch of GEP model shown in Fig. 6.

Key parameters for GEP, like gene length, number of chromosomes, and mutation rates, were optimized to maximize predictive performance in the prediction for both Slump flow (mm) and V funnel. The algorithm was run on a preprocessed dataset that had outliers removed and missing values added, thus making strong predictions.

Deep neural networks (DNN)

The DNN model, being capable of capturing high-level abstraction with the help of large datasets, was developed through multiple layers of neurons that are interconnected with nonlinear activation functions. The number of hidden layers and neurons was optimized to achieve maximum accuracy through trial and error67. The architecture consisted of an:

The Deep Neural Network (DNN) consisted of three hidden layers with 128, 64, 32 units with ReLU activation and dropout rate of 0.2 with a final linear output layer. The model was trained in batches of 32 to a maximum of 500 epochs using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001) and learning rate reduction schedule, and the early stopping with 30-patience was utilized to prevent overfitting. The random seed was fixed (42) to make it reproducible, and hyperparameter optimization was performed on a fixed validation set that was not dependent on the test set in any way. The DNN was trained using an Adam optimizer and mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function. Applications of early stopping and dropout can avoid overfitting. A split of 85% of the dataset for training and 15% as a test set was done, and other hyperparameters such as the number of neurons per layer, batch size, and learning rate were adjusted to optimize the performance using grid search. schematic sketch of DNN shown in Fig. 7.

Decision trees

Decision Trees are one of the most popular machine learning models for classification and regression tasks. They operate by splitting the dataset into subsets based on feature values in a tree-like structure. Each internal node represents a decision based on a specific feature, and each leaf node corresponds to an outcome or prediction. Decision Trees can be easily interpreted and visualized in understanding complex datasets. Nonetheless, they are prone to overfitting, especially as the tree becomes very deep in which case generalization could be impacted.

Techniques such as pruning or the setting of maximum depth commonly must be applied for overfitting. As simple to use, they would not necessarily perform better than even more complex models in problems with high-dimensional data or noise. Despite this, Decision Trees are the base for a lot of advanced models such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosted Trees that boost accuracy and robustness through the combination of multiple trees. They can handle categorical and numerical data, so they are versatile for any application. A split of 85% of the dataset for training and 15% as a test set was done. schematic sketch of DT shown in Fig. 8.

Support vector machine (SVM)

A support vector machine (SVM) is a supervised machine learning algorithm designed for classification and regression tasks73. SVMs work by discovering an optimal hyperplane for the features of the data points from different classes which maximize the margin and pushes the support vectors, the closest data points to the boundary, as far apart as possible from it. SVMs are very effective in handling high-dimensional data and can model nonlinear relationships using kernel functions such as polynomial, radial basis function (RBF), or sigmoid kernels.

Although SVMs are powerful tools, they tend to be computationally expensive, especially for large datasets. Their performance is strongly dependent on the choice of kernel and hyperparameters, including the regularization parameter (C) and the parameters of the kernel. Despite these challenges, SVMs perform well in applications that require high precision, such as text categorization, bioinformatics, and image recognition. A split of 85% of the dataset for training and 15% as a test set was done schematic sketch of SVM shown in Fig. 9.

Random forest (RF)

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that combines the predictions of multiple Decision Trees so that the model can predict more accurately and avoid overfitting. Each of the trees in a Random Forest is trained on some random subset of the data along with features, so the overall trees are diverse. A Random Forest aggregates the individual predictions of all the trees using majority voting for the classification task or averaging in the case of regression. It provides a balance between bias and variance and can effectively handle big datasets and high-dimensional data. But compared to individual decision trees, it can be less interpretable and computationally costly53.

Random Forests are versatile models. It can be used for classification and regression problems effectively without showing overfitting issues during the training phase since they implement randomness in it. In addition, although computational requirements may increase as their ability to use the feature scale increases for very big feature space, they remain useful, especially for problems requiring less complexity like in a certain medical diagnostics problem or finance modeling or even some types of environmental science problem. A split of 85% of the dataset for training and 15% as a test set was done schematic sketch of RF shown in Fig. 10.

Performance metrics

The accuracy of GEP and DNN models was assessed using R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) criteria shown in Table 4. Such metrics measure how successful the applied model is in generalization as well as the reliability of its predictions. The comparison between models showed that they achieved very high prediction performance.

Performance assessment

To ensure that robust models are created that may forecast the output with low error-free outcomes, it is important to evaluate the estimation capacity of machine learning models using a variety of statistical metrics63. To evaluate the effectiveness of the models in both the training and testing stages, this work employs three of the most popular error metrics. Table 4 lists the applied error metrics, their mathematical formulas, their relevance, and the ideal values at which models should be approved.

Results and discussions

Regression slope analysis

The regression plots for training and testing are shown in Figs. 11 and 12, where the estimated data is shown on the y-axis and the actual records are shown on the x-axis. As more data closely matches the line, demonstrating a high degree of agreement between the actual and anticipated values, the model performs better. Furthermore, there is excellent alignment between the model’s predictions and the actual values when the regression slope (RS) is greater than 0.868,69. As seen in Fig. 11, all the V-funnel time (s) models that were generated showed regression slopes. The suggested ML models’ high prediction accuracy was demonstrated by the regression slopes training data for GEP and DNN, which were both above the suggested cutoff of 0.80. The GEP and DNN model demonstrated a strong ability to predict the fresh property with exceptional R- Square values of training dataset is 0.957 and 0.950 Respectively.

As compared, the Decision Tree model exhibits a significantly reduced performance level where R-squared is lower at 0.818. The SVM and RF models are the least effective models in this dataset, with predicted values recording the greatest deviation with the actual value with an R-squared of 0.781 and 0.643 respectively. Overall, the GEP and DNN models are decisively better, as is the SVM model, which is considerably less stable.

Similarly Fig. 12 indicates the predictive performance of Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Decision Tree (DT), Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) models for slump flow (mm) the slump prediction range is 426.136–890 mm for training data set and for testing 380–810 mm. Both models, GEP and DNN, exhibit high levels of accuracy since they predict values that are quite like the real ones, as shown by the high R-squared scores of training data is 0.915 and 0.911, respectively and testing is 0.901 and 0.894 respectively. As compared, the Decision Tree model exhibits a significantly reduced performance level where R-squared is lower at 0.885. The SVM and RF models are the least effective models in this dataset, with predicted values recording the greatest deviation with the actual value with an R-squared of 0.599 and 0.435 respectively. Overall, the GEP and DNN models are decisively better, as is the SVM model, which is considerably less stable.

Residual analysis

Residual analysis for slump flow (mm)

Figure 13 shows residual plots of the slump prediction based on the five models, i.e., GEP, DNN, DT, SVM, and RF, help in depicting the distribution and normality of the residuals thus assessing the performance of the model. The GEP and DNN models are excellent in their performance, with Q-Q plots that are close to the diagonal line and their histograms of the residuals symmetrically and sharply peaked distributions with the mode at zero-meaning normal distribution of residuals and errors that are minimal. Random Forest (RF) is also satisfactory in that it exhibits a slight deviance in the tails. Conversely, the Q-Q plots of DT and SVM are more deviated to normality, and the histograms are wider and tend to be slightly skewed, meaning that the predictions are less consistent, and the residual variance is greater. In general, GEP and DNN are the most successful models in predicting slump relying on the behavior of the residuals, as well as RF being a close second.

Residual analysis for V-Funnel

Figure 14 represents the residual analysis of five models GEP, DNN, DT, SVM, and RF in predicting V-funnel time (s). The Q-Q plots and the histograms of the residuals will be used to determine the distribution of the errors of prediction and their dispersion in each of the models. The Q-Q plots of the GEP and DNN highly follow the line of reference thus showing that the model at hand is approximately normally distributed with their histograms being very sharp and well centered on the origin which implies high degree of prediction and low range of error variability. By contrast, DT and SVM have high deviations in Q-Q plot and broader and more scattered histograms that indicate non-normal residuals and less reliable predictions. RF exhibits moderate ability, and residual patterns are superior to SVM and DT but not very consistent like GEP and DNN. All in all, both GEP and DNN have a better performance in modeling V-funnel time (s); this can be seen in residual behaviors.

Model performance using Taylor diagram

The Taylor diagram provides a comprehensive graphical representation of model performance by simultaneously displaying the correlation coefficient, standard deviation, and centered root mean square error (RMSE) between predicted and actual values. In this study, Taylor diagrams were used to compare the predictive accuracy of five models (GEP, DNN, DT, SVM, and RF) for slump flow (mm) and V-funnel time (s). Models positioned closer to the red reference point indicate higher correlation, better match in standard deviation, and lower error. For both properties, GEP and DNN models showed the best agreement with experimental values, while RF and SVM exhibited relatively lower performance, as indicated by their greater distance from the reference point.

Figure 15a and b indicate that the GEP and DNN models exhibited better accuracy for Slump flow (mm) and V-funnel time (s)prediction. Similarly, Fig. 15b shows that the GEP and DNN model also demonstrated high accuracy for Slump flow (mm) prediction. Overall, the GEP and DNN model showed better accuracy for both v funnel and Slump flow (mm).

Statistical assessment of the models

Low mean squared error (MSE), Root Mean squared error (RMSE), Mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) values underscore the model’s proficiency in minimizing prediction errors77.

Table 5 summaries the predictive performance of all of the models for v-funnel time (s) using a grouped cross-validation with studies and rheometers defining the groups so that there was no overlap between training and test folds. The grouped splits are reported as a mean and standard deviation of repeated results. In sum, GEP and DNN were always better than their conventional machine learning baselines their R2 value is 0.957 and 0.950 respectively.

Table 6 presents the performance of the models in predicting slump flow (mm), evaluated with grouped cross-validation to prevent train–test overlap at the study/rheometer level. GEP and DNN clearly provided the most reliable predictions, achieving R² = 0.915 ± 0.04 and 0.911 ± 0.05, respectively.

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI)

Explaining machine learning (ML) predictions requires mathematical computations, supporting hypotheses, and an understanding of the underlying mechanisms71. Interpretability approaches are commonly employed to make ML models more accessible to non-technical audiences. In this paper we used SHAP and PDP to better interpret the model.

SHAP violin analysis

Feature attribution was done with the TreeSHAP variant of SHAP which gives exact Shapley values for tree-based models. Expected values were also computed using the training data, which served as the background dataset, and were therefore consistent with the model fitting distribution. Because SHAP values may be sensitive to multicollinearity, we also assessed pairwise correlations among input variables; in the presence of strong correlations (|r| > 0.8), we reported SHAP rankings considered jointly instead of assigning importance to a single feature. Finally, to ensure the robustness of the attributions, we contrasted SHAP rankings with permutation importance and found agreement.

Post-training, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis determine the contribution of each feature to the predictive outcomes of the model78.

The generated models are interpreted in this work using SHAP, which offers insights on feature relevance and how it affects output predictions. Multicollinearity and potentially synergistic effects among variables are satisfactorily addressed by the SHAP methodology72. The SHAP values for each parameter are displayed in Fig. 16a. With the greatest SHAP score (about 10) in Slump, total powder (TP) had a notable effect on Slump flow (mm), MGS, FA, cement, Adm, water, and CA. Water had the greatest mean absolute SHAP score in V Funnel modeling, followed by cement concentration, FA, CA, TP, and MGS Fig. 16b. As seen in Fig. 17a and b, the influence of selected factors on model output was examined using the SHAP violin summary graphic. The SHAP violin score of parameters is displayed in Fig. 17a and b. The output target is positively impacted by the feature if the SHAP violin score is positive; higher values signify a stronger influence. It is observable. Slump is negatively impacted by high TP. The Table 7 presents the global mean absolute SHAP values for each target, in descending order of feature contribution to model predictions. For slump flow (mm), total powder and mean grain size were the predominant variables whereas in v-funnel time (s), water and fine aggregate were the predominant variables. This demonstrates that different rheological properties are controlled by different mix design parameters (powder-related properties affecting one target and water binder ratios affecting the other).

PDP explanation

Figures 18 and 19 show the PDP plots for slump flow (mm) and V-funnel, respectively. Partial dependence plots were trimmed to realistic mix-design domains for interpretation: cement (230–550 kg/m3; The partial dependence plots of slump-flow show the ability to interpret feature-response trends. Cement content (230–550 kg/m3) increases slump-flow up to about 450 kg/m3 (about + 60 mm) and then the effect becomes constant. Total powder (350–650 kg/m^3) exhibits a non-monotonic behavior: slump-flow decreases by − 40 mm up to 450 kg/m^3 and then increases again by approximately + 50 mm towards 600 kg/m^3, probably due to admixture dosage interactions. Coarse aggregate (550–950 kg/m3) has a moderate effect (plus or minus 20 mm). Water content has a very significant influence on slump-flow, resulting in an increase of about + 50 mm between 160 and 200 kg/m3 (keeping other parameters at median). Across all the PDPs, 95% CI bands and data-density rug plots are presented, and regions of non-monotonicity are highlighted explicitly as being due to interactions of the features (e.g. high TP with low admixture) or to sparsity of the data rather than model instability.

Figure 19 shows partial dependence plots for V-funnel which shows obvious quantitative patterns. Cement increase from 200 to 550 kg/m3 increases V-funnel time (s) by approx. +5 s. The non-linear effect is strongest for coarse aggregate: V-funnel decreases by -4 s between 550 and 750 kg/m^3 then increases again by + 5 s up to 950 kg/m^3. A U-shaped relation was observed for water, with water decreasing V-funnel by -6 s up to a W/P ratio of 1.0 before rising by + 8 s as W/P neared 3.5. By comparison, total powder causes less than 1 s variation and maximum grain size only impacts V-funnel up to 0.8 mm (approximately − 5 s) before the effect becomes constant.

Conclusion

This study showed how state of the art machine learning models can be used to predict the fresh properties of the self-consolidating concrete (SCC). Five ML algorithms GEP, DNN, DT, SVM and RF were compared based on their predictive power of slump flow and V-funnel time by using a strictly filtered dataset of 348 SCC mixtures. Of these, both GEP and DNN performed better than other models, with higher values of R 2 and other error measures, whereas explainable AI systems like SHAP and PDP provided valuable insights into the impact of mix design parameters. The results validate that a combination of ML and explainability techniques can be an effective method to achieve high accuracy of predictions, less dependence on tiresome laboratory analyses, and can justify optimization of SCC mix design in practice.

-

GEP and Deep Neural Networks (DNN) performed better with up to 0.93 and 0.82 of the R 2 respectively with V-funnel and slump flow respectively.

-

Taylor diagram, Q-Q plot and residual analysis confirmed the strength of GEP and DNN, and the results of the prediction and the experimental findings were in high agreement.

-

SHAP and PDP analyses showed that various mix design factors predominate various rheological characteristics, total powder and mean grain size have pronounced effect on slump flow, and water and fine aggregates condition V-funnel action.

-

Altogether, this study highlights the promise of explainable ML models to revolutionize SCC mix design optimization, allowing them to build more quickly, affordably, and reliably.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, J. & Zhou, J. Joseph Kangwa Self-compacting concrete adopting recycled aggregates. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-89838-6.00007-4 (2025).

Chiara, F. Ferraris measurement of the rheological properties of high performance concrete: state of the art report. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.104.028 (2025).

Ferreira, C. Gene expression programming: a new adaptive algorithm for solving problems. Complex. Syst. 13 (2), 87–129 (2001). https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0102027

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521 (7553), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539 (2015).

Aicha, M. B. E. N. et al. Prediction of the flowability of self-compacting concrete using artificial neural networks. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.019 (2025).

İbrahim, Ö. D. Modeling of compressive strength of self-compacting concrete containing fly Ash by gene expression programming. https://doi.org/10.7764/rdlc.19.2.346 (2025).

Feys, D. et al. RILEM TC 266-MRP: round-robin rheological tests on high performance mortar and concrete with adapted rheology rheometers, mixtures and procedures. Mater. Struct. 56, 90. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-023-02173-1 (2023).

Kalyon, D. M. & Aktas¸, S. Factors affecting the rheology and processability of highly filled suspensions. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 5, 229–254. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060713-040211 (2014).

Asuka, T. & Tatsuya, M. Factors affecting rheological properties of barley flour-derived batter and dough examined from particle properties. Food Hydrocoll. 129, 107645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107645 (2022).

Nguyen, T. D., Tran, T. H. & Hoang, N. D. Prediction of interface yield stress and plastic viscosity of fresh concrete using a hybrid machine learning approach. Adv. Eng. Inf. 44, 101057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101057 (2020).

Ferraris, C. F. & DeLarrard, F. Testing and Modeling of Fresh Concrete Rheology, NIST (1998, accessed 8 Sep 2023). https://www.nist.gov/publications/testing-and-modeling-fresh-concrete-rheology.

Nazar, S. et al. An evolutionary machine learning-based model to estimate the rheological parameters of fresh concrete. Structures 48, 1670–1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.01.019 (2023).

Ben Aicha, M., Al Asri, Y., Zaher, M., Alaoui, A. H. & Burtschell, Y. Prediction of rheological behavior of self-compacting concrete by multi-variable regression and artificial neural networks. Powder Technol. 401, 856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117345 (2022).

Ben Aicha, M., Burtschell, Y., Alaoui, A. H., El Harrouni, K. & Jalbaud, O. Correlation between bleeding and rheological characteristics of self-compacting concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 29, 05017001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001871 (2017).

Asri, Y. E. L. et al. Prediction of plastic viscosity and yield stress of self-compacting concrete using machine learning technics. Mater. Today: Proc. 59, A7–A13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.891 (2022).

Cakiroglu, C., Bekdas¸, G., Kim, S. & Geem, Z. W. Explainable ensemble learning models for the rheological properties of self-compacting concrete. Sustainability 14, 14640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114640 (2022).

Okamura, H. & Ouchi, M. Self-compacting high-performance concrete. Prog Struct. Eng. Mater. 1, 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/pse.2260010406 (1998).

Benaicha, M., Roguiez, X., Jalbaud, O., Burtschell, Y. & Alaoui, A. H. Influence of silica fume and viscosity modifying agent on the mechanical and rheological behavior of self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 84, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.03.061 (2015).

Sahraoui, M. & Bouziani, T. Effects of fine aggregate types and contents on rheological and fresh properties of SCC. J. Build. Eng. 26, 100890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100890 (2019).

Cheng, B. et al. Ai-guided proportioning and evaluating of self-compacting concrete based on rheological approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 399, 132522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132522 (2023).

Wu-Jian, L. et al. Rheological approach in proportioning and evaluating prestressed self-consolidating concrete. Cem. Concr Compos. 82 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.05.008 (2017).

Cu, Y. T. H., Tran, M. V., Ho, C. H. & Nguyen, P. H. Relationship between workability and rheological parameters of self-compacting concrete used for vertical pump up to supertall buildings. J. Build. Eng. 32, 101786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101786 (2020).

Benaicha, M., Jalbaud, O., Roguiez, X., Hafidi Alaoui, A. & Burtschell, Y. Prediction of self-compacting concrete homogeneity by ultrasonic velocity. Alex Eng. J. 54, 1181–1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2015.08.002 (2015).

Zhang, J., An, X. & Li, P. Research on a mix design method of self-compacting concrete based on a paste rheological threshold theory and a powder equivalence model. Constr. Build. Mater. 233, 117292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117292 (2020).

Benaicha, M., Roguiez, X., Jalbaud, O., Burtschell, Y. & Alaoui, A. H. New approach to determine the plastic viscosity of self-compacting concrete. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 10, 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-015-0327-5 (2016).

Benaicha, M., Hafidi Alaoui, A., Jalbaud, O. & Burtschell, Y. Dosage effect of superplasticizer on self-compacting concrete: correlation between rheology and strength. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8, 2063–2069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.01.015 (2019).

Ling, G. et al. Rheological behavior and microstructure characteristics of SCC incorporating Metakaolin and silica fume. Materials 11, 2576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122576 (2018).

Sfikas, I. P., Badogiannis, E. G. & Trezos, K. G. Rheology and mechanical characteristics of self-compacting concrete mixtures containing Metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 64, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.048 (2014).

Kabagire, K. D., Yahia, A. & Chekired, M. Toward the prediction of rheological properties of self-consolidating concrete as diphasic material. Constr. Build. Mater. 195, 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.053 (2019).

Nanthagopalan, P. & Santhanam, M. A new empirical test method for the optimisation of viscosity modifying agent dosage in self-compacting concrete. Mater. Struct. 43, 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-009-9481-3 (2010).

Benaicha, M., Jalbaud, O., Hafidi Alaoui, A. & Burtschell, Y. Porosity effects on rheological and mechanical behavior of self-compacting concrete. J. Build. Eng. 48, 103964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103964 (2022).

Durgun, M. Y. & Atahan, H. N. Rheological and fresh properties of reduced fine content self-compacting concretes produced with different particle sizes of nano SiO2. Constr. Build. Mater. 142, 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.098 (2017).

Boukendakdji, O., Kadri, E. H. & Kenai, S. Effects of granulated blast furnace slag and superplasticizer type on the fresh properties and compressive strength of self-compacting concrete. Cem. Concr Compos. 34, 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.08.013 (2012).

Benaicha, M., Belcaid, A., Alaoui, A. H., Jalbaud, O. & Burtschell, Y. Rheological characterization of self-compacting concrete: new recommendation. Struct. Concr. 20, 1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201900154 (2019).

el Safhi, A. M. A comprehensive self-consolidating concrete dataset for advanced construction practices (2024). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10569517.

Ahmad, W. K. & Sanjay, K. Rheological study of high-performance concrete composed of fly Ash and silica fume using ICAR rheometer (2025).

Bauchkar, S. D. & Chore, H. S. Rheological properties of self consolidating concrete with various mineral admixtures. Struct. Eng. Mech. 51, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.12989/sem.2014.51.1.001 (2014).

Schankoski, R. A., de Matos, P. R., Pilar, R., Prudˆencio, L. R. & Ferron, R. D. Rheological properties and surface finish quality of eco-friendly self-compacting concretes containing quarry waste powders. J. Clean. Prod. 257, 120508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120508 (2020).

Shen, W. et al. Influence of pumping on the resistivity evolution of high-strength concrete and its relation to the rheology, Constr. Build. Mater. 302, 124095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124095 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Rheological property and stability of nano-silica modified self-compacting concrete with manufactured sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 401, 132935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132935 (2023).

Li, F. et al. Pressure-based analysis of rheological equilibrium distances of pumped self-consolidating concrete (SCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134517 (2024).

Benaicha, M., Burtschell, Y., Alaoui, A. H. & Elharrouni, K. Theoretical calculation of self-compacting concrete plastic viscosity. Struct. Concr. 18, 710–719. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.201600064 (2017).

Feys, D., Khayat, K. H., Perez-Schell, A. & Khatib, R. Development of a tribometer to characterize lubrication layer properties of self-consolidating concrete. Cem. Concr Compos. 54, 40–52 (2014).

Derabla, R. & Benmalek, M. L. Characterization of heat-treated self-compacting concrete containing mineral admixtures at early age and in the long term. Constr. Build. Mater. 66, 787–794 (2014).

Esmaeilkhanian, B., Khayat, K. H. & Wallevik, O. H. Mix design approach for low- powder self-consolidating concrete: eco-SCC content optimization and performance. Mater. Struct. 50, 124. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-017-0993-y (2017).

Saleh Ahari, R., Erdem, T. K. & Ramyar, K. Permeability properties of self- consolidating concrete containing various supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 79, 326–336 (2015).

Saleh Ahari, R., Erdem, T. K. & Ramyar, K. Time-dependent rheological characteristics of self-consolidating concrete containing various mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 88, 134–142 (2015).

Saleh Ahari, R., Kemal Erdem, T. & Ramyar, K. Effect of various supplementary cementitious materials on rheological properties of self-consolidating concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 75, 89–98 (2015).

Ajay, N., Girish, S. & Nagakumar, M. S. Use of concrete shear box for measuring the Bingham parameters of SCC. Mater. Today: Proc. 46, 4598–4604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.714 (2021).

Li, W. et al. The properties and mesco/ microstructure characteristics of interfacial zone between precast concrete and self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 297, 123753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123753 (2021).

Dabiri, H. et al. Machine learning-based analysis of historical towers. Eng. Struct. 304, 117621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.117621 (2024).

Younsi, S. et al. Reconstructing missing InSAR data by the application of machine leaning-based prediction models: a case study of Rieti. J. Civ. Struct. Heal Monit. 14, 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-023-00730-4 (2024).

el Safhi, A. M., Dabiri, H., Soliman, A. & Khayat, K. H. Prediction of self-consolidating concrete properties using XGBoost machine learning algorithm: part 1–workability. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133560 (2023).

EFNARC. The European Guidelines for Self-Compacting Concrete: Specification, Production and Use (International Bureau for Precast Concrete (BIBM), 2005).

ACI Committee 237, ed. Self-Consolidating Concrete (American Concrete Institute, 2007).

Craeye, B., Van Itterbeeck, P., Desnerck, P., Boel, V. & De Schutter, G. Modulus of elasticity and tensile strength of self-compacting concrete: survey of experimental data and structural design codes. Cem. Concr Compos. 54 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.03.011 (2014).

Nehdi, M. & Al-Martini, S. Coupled effects of high temperature, prolonged mixing time, and chemical admixtures on rheology of fresh concrete. ACI Mater. J. 106, 231–240 (2009).

el Safhi, A. M., Benzerzour, M., Rivard, P. & Abriak, N. E. Feasibility of using marine sediments in SCC pastes as supplementary cementitious materials. Powder Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2018.12.060 (2018).

Xie, T., Mohamad Ali, M. S., Elchalakani, M. & Visintin, P. Modelling fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials using reactive moduli. Constr. Build. Mater. 272, 121954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121954 (2021).

Jiao, D. et al. Effect of constituents on rheological properties of fresh concrete-a review. Cem. Concr Compos. 83, 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.07.016 (2017).

Shi, C. et al. A review on ultra high performance concrete: part I. Raw materials and mixture design. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.088 (2015).

Feys, D. & Khayat, K. Comparing rheological properties of SCC obtained with the ConTec and ICAR Rheometers (2015).

Li, Z., Gao, X. & Lu, D. Correlation analysis and statistical assessment of early hydration characteristics and compressive strength for multi-composite cement paste. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125260 (2021).

Chu, H. H. et al. Sustainable use of fly-ash: use of gene-expression programming (GEP) and multi-expression programming (MEP) for forecasting the compressive strength geopolymer https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2021.03.018 (2025).

Khan, M. A. et al. Geopolymer concrete compressive strength via artificial neural Network, adaptive neuro fuzzy interface System, and gene expression programming with K-Fold cross validation. Front. Mater. 8, 621163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.621163 (2021).

Christian Tominski Interacting with Visualizations. Inf. Vis. 2021, 359–392. https://link.springer.com/book/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02600-3 (2021).

Naved, M., Asim, M. & Ahmad, T. Prediction of concrete compressive strength using deep neural networks based on hyperparameter optimization. Cogent Eng. 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2023.2297491 (2024).

Khan, A. et al. Predictive modeling for depth of wear of concrete modified with fly ash:a comparative analysis of genetic programming-based algorithms. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, e02744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02744 (2023).

Xenochristou, M., Hutton, C., Hofman, J. & Kapelan, Z. Water demand forecasting accuracy and influencing factors at different Spatial scales using a gradient boosting machine. Water Resour. Res. 56, 562. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026304 (2020).

Sagi, O. & Rokach, L. Explainable decision forest: transforming a decision forest into an interpretable tree. Inform. Fusion. 61, 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2020.03.013 (2020).

Lipton, Z. C. The mythos of model interpretability. Queue 16, 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1145/3236386.3241340 (2018).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global Understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9 (2020).

Askari, D. F. A. et al. Prediction model of compressive strength for eco-friendly palm oil clinker light weight concrete: a review and data analysis. https://link.springer.com/article/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44290-024-00119-2 (2025).

Tipu, R. K. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of concrete strength properties with coconut shell as partial aggregate replacement: a sustainable approach in construction engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00957-y (2025).

Wu, Y., Kang, F., Zhu, S. & Li, J. Data-driven deformation prediction model for super high arch dams based on a hybrid deep learning approach and feature selection. Eng. Struct. 325, 119483 (2025).

Tipu, R. K. et al. Optimizing compressive strength in sustainable concrete: a machine learning approach with iron waste integration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01061-5 (2024).

Tipu, R. K. et al. Predicting compressive strength of concrete with iron waste: a BPNN approach. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01130-9 (2024).

Pooja Lamba, D. P. et al. Repurposing plastic waste: Experimental study and predictive analysis using machine learning in bricks. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.139158 (2024).

Tipu, R. K., Batra, V., Suman, K. S., Pandya, V. R. & Panchal efficient compressive strength prediction of concrete incorporating recycled coarse aggregate using newton’s boosted backpropagation neural network (NB-BPNN). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105559 (2025).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Maaz Khan, Muhammad Faisal Javed, Hisham Alabduljabbar, and Furqan Ahmad. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Maaz Khan and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Javed, M.F., Alabduljabbar, H. et al. Explainable machine learning and ensemble models for predicting fresh properties of self consolidating concrete. Sci Rep 15, 42288 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21305-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21305-x