Abstract

Explicit motor sequence learning (ESL) consolidation manifests as skill improvements during rest periods that last minutes or longer. However, recent evidence suggests that ESL improvements also occur during inter-trial rest periods that last seconds (micro offline gains; MOGS). While indirect evidence supports that MOGS is a phenomenon tied to brief periods of wakeful rest, this hypothesis has never been directly tested. Prior studies suggest that MOGS and sequence learning in general rely on associative memory processes that link sequence elements across time and space. However, evidence supporting this hypothesis in healthy humans is lacking. We reasoned that if wakeful rest during inter-trial ESL periods is necessary for MOGS, replacing these periods with an engaging task should degrade MOGS. Additionally, we explored whether associative processes support MOGS, predicting that associative memory encoding during inter-trial periods would further degrade MOGS. To this end, we compared the performance of three groups that differed only in whether inter-trial periods included no task (REST), an associative encoding task (ENC), or a semantic judgment task (SEM). We identified no significant group differences in ESL or MOGS, which were confirmed by Bayesian analyses. These results are consistent with the notion that MOGS capture inter-trial performance changes rather than a rapid form of consolidation that requires rest or depends on associative memory processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with sensorimotor network damage often need to relearn everyday motor skills. To facilitate such relearning, rehabilitation specialists must understand the conditions that optimally support motor skill acquisition and motor memory stabilization. An intense area of motor learning research centers on improvements in motor memory stabilization, or consolidation, during time away from practice. During these “offline” periods (which typically last minutes, hours, or days), motor network neuroplasticity supports the consolidation of motor memories1,2. Such consolidation improves motor skill performance and makes newly-acquired motor memories more resistant to interference from other memories and experiences3,4,5,6,7. A commonly used paradigm for measuring motor memory consolidation is the explicit sequence learning (ESL) task8, which requires the learner to perform a sequence of keypresses (similar to playing a melody on a piano) as accurately and rapidly as possible. In this task, learning manifests as improvements in effector (i.e., finger) coordination, resulting in more efficient sequence production. ESL performance is typically measured as the number of correct sequences completed during a fixed time period, while consolidation is typically measured as the difference in performance between the end of an acquisition period and the beginning of a retention period that occurs after a period of rest. ESL performance generally increases with practice, and these practice-related improvements are commonly referred to as “online gains.” However, ESL performance also increases during time away from the task due to consolidation, and these improvements are termed “offline gains”2,3,6,9.

While motor skill consolidation is thought to require minutes or hours of wakefulness and/or longer periods of sleep7,10, recent findings suggest that consolidation may also occur during brief inter-trial rest periods lasting just 10 s11,12. Because these “micro offline” gains (MOGS) in skill performance are also associated with neural biomarkers11,13,14, several recent studies have suggested that MOGS reflect a rapid form of consolidation essential to motor skill learning.

Interestingly, the neural biomarkers linked to MOGS include elements of a network that supports associative memories13,15,16, including the hippocampus and precuneus17,18 and evidence linking hippocampal function to nondeclarative memory has grown considerably in recent decades19,20. The exact role of the hippocampus in motor and procedural learning is still unclear, but recent work suggests that it associates temporally asynchronous, yet related observations into memory engrams21,22,23, consistent with the theory that the hippocampus binds stimuli and their features across space and time23. Despite this possibility, evidence linking associative memory processes to motor learning in healthy humans is still lacking.

While several prior studies11,13 including a large-scale crowd-sourced study12 have reproduced the results of the original report13, multiple knowledge gaps related to the boundaries and contingencies of MOGS remain. First, an experimental manipulation examining whether rest per se is necessary for MOGS has not been conducted. In general, one would expect that if rest were required for MOGS, performing any task that is more taxing than wakeful rest during inter-trial periods should decrease MOGS. Additionally, although the neural correlates of MOGS are becoming clearer13,15,16, the cognitive and motor processes that support MOGS are still poorly understood. In particular, the role of associative processes in MOGS and ESL in general have never been evaluated.

The original report revealing evidence of MOGS showed that brief periods of rest between ESL trials are associated with strong improvements in performance, while improvements that occur during the trial itself (micro-online gains; MOnGS) are considerably weaker11. Here, we aimed to reproduce these findings in a group of healthy adult participants who performed no task during inter-trial periods (REST group) and thus experienced the same experimental conditions as in the initial study. We also included two additional groups that were identical to this REST group except that they were instructed to either encode associative memories (ENC group) or judge the semantic similarity of two words (SEM group) during the inter-trial periods. The latter group was included to control for non-specific effects related to performing a task during inter-trial periods and isolate the role of associative memory processes. We reasoned that if MOGS reflect consolidation and thus require rest, then the ENC and SEM groups would experience significantly smaller MOGS compared to the REST group. We further reasoned that if MOGS rely on associative memory processes, then the ENC group would experience significantly smaller MOGS compared to the other two groups.

Experimental procedure

Participants

Prior to data collection, our study was pre-registered on Aspredicted.org (#141506). Forty-five right-handed neurotypical adults (age range: 18–36 years, 16 males, 29 females) participated in an experiment involving ESL task performance during electroencephalography (EEG) recordings. This experiment was part of a larger study involving noninvasive brain stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), although participants did not receive stimulation or undergo fMRI procedures before or during the experiment described in this report. Therefore, in the current experiment, participants were excluded from the study if they reported contraindications to neuroimaging or noninvasive brain stimulation. We also excluded participants with non-corrected vision impairments or color blindness. No participant failed screening due to neuroimaging or neurostimulation contraindications or reported any non-corrected vision impairments.

Participants were evenly assigned into one of three groups based on order of recruitment. To ensure that our study was powered to observe MOGS in the REST group, we determined the sample size for all groups using the effect size from the original report by Bönstrup et al., who first reported MOGS during skill acquisition11 in 33 healthy younger adults (2.69 ± 0.63 average change in keypresses per second, t(32) = 4.19, p < .001, d = 4.26). Assuming an effect size of 4.26 from this study, α = 0.05, and power (1-β) = 0.95, our study would have a 99.9% chance of observing significant MOGS with only four participants per group. However, to improve the reliability and generalizability of our results, we increased our target sample size to 15 participants per group. All participants provided their written informed consent prior to participation and the study was conducted in accordance with all relevant guidelines and regulations. Experimental procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Texas at Austin. Participants were compensated $15 per hour, and experimental procedures typically lasted for 2 h.

General procedures

After consent and screening procedures, participants were prepared for EEG recordings. EEG signals were recorded for five minutes while participants rested quietly with their eyes open as well as continuously during remaining task procedures. EEG results are not reported here. During skill acquisition, participants experienced 24 trials, each lasting 20 s (8 min total). The acquisition phase of the ESL task consisted of 24 10 s trials of ESL performance, each split by a 10 s inter-trial period (Fig. 1A; 23 total). Following acquisition, all participants rested for 30 min before completing the final nine retention trials. These nine trials were identical to the acquisition trials and all participants rested during the eight inter-trial periods. After retention testing, the associative memory encoding (ENC) and semantic judgement (SEM) groups completed a memory probe (see below).

Experimental procedures and task. (A) Participants performed the ESL task across 24 acquisition and 9 retention trials (black lines), each of which followed an inter-trial period (grey lines). (B) The REST, ENC, and SEM groups differed only in their inter-trial period experience and instructions. (C) During trials, participants typed the 4-1-3-2-4 sequence on a response pad using their index, pinky, middle, ring, and index fingers, respectively.

In the context of our experiment, “online” periods refer to trials where the participant is actively performing the ESL task and “offline” periods are inter-trial periods away from the ESL task. In the ESL task, performance improvements are typically measured as increases in the number of correctly performed sequences across acquisition trials11,24,25,26. Thus, as opposed to implicit sequence learning tasks, where participants typically acquire subconscious knowledge of the sequence over several trials27,28, participants are told the sequence on the first trial and learning manifests as improvements in effector (i.e., finger) coordination, measured as increased efficiency in sequence production8.

During ESL trials, participants typed a single, fixed sequence as quickly and accurately as possible. The sequence was continuously displayed in the center of the computer screen and responses were collected on a Chronos response box (Psychology Software Tools; Fig. 1B). Because this response box includes five keys and the numerical sequence used in this study only contained four distinct numbers, the rightmost key was occluded, and participants were instructed to disregard it. Participants were also instructed that the sequence they experienced on the first trial would not change over the course of the experiment. The sequence of 4-1-3-2-4 (with 4 corresponding to the index finger, 3 to the middle finger, 2 to the ring finger, and 1 to the pinky finger, respectively [Fig. 1C]) was fixed and did not vary across trials or participants. We used this specific sequence to replicate the approach of the original report of MOGS11. Participants were instructed to accurately complete as many sequences as possible during the 10-second trial periods, to begin as soon as the sequence appeared on the screen, and to continue until the trial ended. Each response, regardless of accuracy, produced a yellow asterisk on the screen that appeared just below the presented sequence (Fig. 1B). This response feedback was identical to that used by Bönstrup et al.11 and was included to ensure that all responses were registered by E-prime software29, that the participant’s fingers were correctly positioned over each key, and that participants pressed the keys with sufficient force.

The experiment included three groups of participants which differed only in their experience and instructions during the inter-trial periods: REST, ENC, and SEM. These names correspond to the task demands for each group: rest for the REST group; encoding for the ENC group, and semantic judgements for the SEM group. The REST group was instructed to rest quietly during the inter-trial periods. For the REST group’s inter-trial periods, the sequence of numbers shown on the screen was replaced by a series of X’s (Fig. 1B, top). Note that the procedures of this group were identical to those used by Bönstrup et al.11. For the ENC group’s inter-trial periods, the sequence of numbers was also replaced by a series of X’s, but a pair of words was displayed immediately below the X’s (Fig. 1B, middle). This word pair remained on the screen for the first five seconds of the break. Participants in the ENC group were instructed to remember the word pairs so that they could recall them later. For the SEM group’s inter-trial period, the sequence of numbers was also replaced by a series of X’s with a pair of words displayed immediately below them. However, participants in this group were instructed to silently determine the similarity of the two words presented on the screen (Fig. 1B, bottom). We did not provide further instructions to the SEM group, allowing them to make as many semantic comparisons as they wished. However, we manipulated the semantic relatedness of the word pairs so that half of the word pairs were members of one of three categories (e.g., tools, animals, foods) and the remaining were not (see below). Therefore, while we cannot confirm the exact comparisons that were made by the SEM group, our experimental design encouraged participants to make categorical comparisons.

The ENC and SEM groups were shown pairs of words for five seconds during the 23 inter-trial periods during skill acquisition. Presented words were either animals (turtle, elephant, eagle, sheep, snake, butterfly, dolphin, ant, giraffe, lion, cat, dog, crow, fly, panda, koala), tools (wrench, shears, drill, pliers, hammer, screwdriver, saw, axe, chisel, awl, hatchet, stepladder, spade, trowel, lawnmower, shovel), or food (salad, cake, pudding, yogurt, bread, eggs, pizza, hamburger, pasta, ketchup, honey, grapes, waffles, chips, burrito, sushi). There were 16 words for each category, and each word was presented once during skill acquisition. The words were paired so that participants observed 12 within-category pairs (i.e., animal-animal [4 pairs], tool-tool [4 pairs], food-food [4 pairs]) and 12 between-category pairs (i.e., animal-food [4 pairs], animal-tool [4 pairs], and tool-food [4 pairs]) during acquisition. This approach was used to ensure variability in the semantic relatedness of the pairs for the SEM group (see below). Pairs were presented in a randomized order across trials for each participant and all participants were shown the same 24 total word pairs.

To equate task demands between groups during acquisition, we did not require responses during inter-trial periods. The inter-trial period tasks differed in their associative demands: the ENC group was explicitly told to remember the word pairs, while the SEM group was not. This allowed us to isolate the effects of associative memory encoding while separating them from non-specific effects of task performance. Note that although the ENC group likely engaged in intentional memory encoding processes, the SEM group was also likely to incidentally remember the word pairs as well.

Following the 24 skill acquisition trials, participants were instructed to rest for 30 minutes. After this 30 minute rest period, all groups completed nine retention trials that were identical to the procedures experienced by the REST group during skill acquisition. Finally, following the ESL task, participants in the ENC and SEM groups performed a recognition task. Each group was shown one word of each pair and participants were instructed to select its pair from a series of four choices. Three of the choices were foils of the same category as the correct word. For example, from the pair “giraffe-chisel,” the word “giraffe” was presented along with four tool options: “chisel,” “awl,’ “hatchet,” and “stepladder.” Participants indicated their response by pressing 1, 2, 3, or 4 on a standard keyboard. No time limit was imposed.

Data analysis

Although participants performing the ESL task are instructed to maximize the number of correct sequences produced on each trial, Bönstrup et al.11 found that improvements in typing speed occur between trials (i.e., MOGS) rather than during trials (i.e., MOnGS). Therefore, as in other studies of ESL3,8,11,26, we predicted that (1) the number of correct sequences performed across acquisition trials would increase, (2) MOGS would be generally positive, and (3) MOnGs would either be near zero or negative. These predictions are specific to the early stages of ESL acquisition analyzed by Bönstrup et al. While the number of correct sequences represents general improvements in ESL, here we specifically focused on MOGS as our metric of interest, since the factors that define it are less well understood.

Calculation of micro offline (MOGS) and micro-online (MOnGS) gains

Following the methodology of Bönstrup et al.11, we calculated MOGS between the 23 inter-trial periods and micro-online gains (MOnGS) within the 24 intra-trial periods during skill acquisition. MOGS and MOnGS were calculated by measuring changes in tapping speed (keypresses per second [KPS])11 between succesfully completed sequences. KPS was calculated as the number of correctly performed elements of a sequence divided by the computer clock time between the first and last elements of that sequence. For example, a complete and accurately performed sequence with a computer clock time of 2.3 s between the first and last response keys would have a KPS of 2.17 (5 keypresses over 2.3 s). MOGS were defined as the difference in KPS between the last accurately performed sequence of one trial and the first accurately performed sequence of the following trial, where positive numbers indicate performance improvements and negative numbers indicate performance decrements. MOnGS were defined as the difference in KPS between the first and last accurately performed sequences within a trial, where positive numbers again indicate performance improvements and negative numbers indicate performance decrements. Consistent with Bönstrup et al., if the last sequence was performed correctly but was cut off by the end of the trial, it was counted as the last correct sequence and KPS for that sequence was recorded. For example, if the first three elements of a sequence were performed correctly as the trial ended, KPS was calculated by dividing 3 by the computer clock time between the first and third response.

Motor skill acquisition and retention

Aside from MOGS and MOnGS, we also measured motor skill acquisition and retention. A single sequence was considered correct if all elements of the sequence were accurately performed in succession within the 10 s trial limit. Consistent with MOGS and MOnGS calculations (see above), participants were also given partial credit if they performed the last sequence correctly, but it was incomplete because the trial ended. For example, if the participant performed the sequence “4-1-3-2,” “4-1-3,” or “4-1” before the trial ended, 0.8, 0.6, or 0.4 was added to the number of correctly performed sequences, respectively30. Three-parameter asymptotic exponential curves were individually fit to all participants’ ESL performance data using MATLAB’s fmincon function. The model included acquisition asymptote (the predicted ceiling for performance), acquisition magnitude (the difference between the asymptote and first trial performance), and acquisition rate (the trial number by which asymptotic performance is reached). For the acquisition asymptote parameter, values were allowed to range between 0 and the maximum number of correct sequences performed on any acquisition trial. For the acquisition magnitude and rate parameters, values were allowed to range between 0 and 10. The starting parameters for acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, and acquisition rate were set as each participant’s maximum number of correct sequences on any acquisition trial, the difference between the maximum and minimum number of correct sequences on any acquisition trial, and 1, respectively. Function tolerance, step tolerance, maximum iterations, and the maximum functional evaluations of the model were set to 1.0 × 10− 30, 1.0 × 10− 8, 2.0 × 105, and 4.0 × 105, respectively. All three parameters for each participant were forwarded to a group analysis (see Statistical Analysis). Retention scores were calculated for each participant by subtracting the average number of correct sequences performed during the last six acquisition trials from the average number of correct sequences performed during all nine retention trials.

Associative memory performance

The ENC and SEM groups both experienced the same word pairs during the acquisition inter-trial periods. For these groups, recognition performance accuracy was calculated as the number of correct responses during the memory probe, with a total of 6/24 correct responses (25%) reflecting chance-level performance.

Statistical analysis

We predicted that if rest is necessary for MOGS, performing a task during the inter-trial periods would significantly reduce MOGS relative to performing no task during these periods. Thus, we expected MOGS to be significantly smaller in the ENC and SEM groups relative to the REST group. We also explored whether associative memory processes support MOGS, predicting that performing an associative memory encoding task during the acquisition inter-trial periods would significantly decrease MOGS compared to performing a similar task that does not require associative memory encoding or resting during these same periods. Thus, we expected MOGS to be significantly smaller in the ENC group relative to the REST and SEM groups. In the SEM group, one participant’s data were excluded from statistical analysis because the participant failed to register a correct sequence on more than half of the acquisition trials. All statistical analyses were performed in MATLAB 2025a31 or JASP32. For all comparisons, alpha was set to 0.05.

Reproducing the findings of Bönstrup et al.11

Bönstrup et al.11 calculated MOGS and MOnGS within an early learning period defined as the first 11 trials during acquisition. Within this period, they found convincing evidence that MOGS are positive, MOnGS are negative, and that MOGS are significantly greater than MOnGS. To ensure that we could reproduce these findings and validate our power analysis, we performed the same analyses described by Bönstrup et al. for the REST group. For each participant, we calculated mean MOGS across the first 10 inter-trial periods and mean MOnGS across the first 11 trials. One-tailed unpaired t-tests were used to evaluate whether MOGS were significantly greater than zero and whether MOnGS were significantly smaller than zero. We also used a one-tailed paired t-test to evaluate whether MOGS were significantly greater than MOnGS. To confirm that our results for the REST group were sufficiently powered, we performed a post-hoc power analysis comparing average MOGS on the first 10 inter-trial periods to zero using MATLAB’s sampsize function. For this analysis, mu0 was set to zero, sigma0 was set to the standard deviation of participants’ average MOGS across the first 10 inter-trial periods, and mu1 was set to the mean of participants’ average MOGS across the first 10 inter-trial periods.

Investigating group differences in MOGS and break point determination

To determine whether MOGS differed between the three groups, average MOGS from the early learning period (defined as the first 11 trials) for each participant and group were submitted to a linear mixed-effects model analysis using INTERTRIAL PERIOD (1–10), GROUP (REST vs. ENC vs. SEM), and their interactions as fixed effects and subject as a random intercept. We chose the first 11 trials to define early learning based on the analysis of Bönstrup et al.11. In their study, early learning was defined by averaging participants’ learning curves using the number of correct sequences performed per trial. The trial where 95% of total learning was surpassed was selected as the break point that distinguished early and late learning11.

While the approach of defining early learning using the 95% method was sufficient for defining MOGS in the original report11, it is possible that group differences in MOGS in the current study may depend on the chosen break point. Therefore, we formally evaluated whether the choice of break point affected our results. We submitted average MOGS calculated using trials preceding each possible break point (1–24) to a linear mixed effects model with GROUP (REST, ENC, SEM) as a fixed effect, BREAK POINT (1–23) as a covariate, and SUBJECT as a random intercept. We reasoned that if group differences in MOGS depend on break point, then we should observe a significant group effect even when statistically controlling for the number and order of trials used to calculate MOGS.

Investigating group differences in MOnGS

To determine whether MOnGS differed between the three groups, average MOnGS from the early learning period for each participant and group were submitted to a linear mixed-effects model analysis using TRIAL (1–11), GROUP (REST vs. ENC vs. SEM), and their interaction as fixed effects and subject as a random intercept.

Motor skill acquisition and retention analysis

ESL skill performance is typically represented as the number of correct sequences performed on each trial3,8. We therefore asked whether introducing a task during the inter-trial periods would significantly reduce (1) the acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, and acquisition rate during skill acquisition, and (2) the retention values calculated as the difference in performance between the acquisition and retention periods. Acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, acquisition rate, and retention values for each group were therefore submitted to four separate one-way ANOVAs.

We note that because we are examining the effect of group on several measures (i.e., MOGS, asymptote, magnitude, rate, retention), that it would be best practice to correct for multiple comparisons, as performed by Bönstrup et al. However, multiple comparisons correction is necessary to avoid a Type 1 error (that an effect exists when in fact it doesn’t), whereas our results instead suggest no effect of group on any of our motor learning metrics. Thus, because our results did not support the alternative hypothesis, correcting for multiple comparisons would not have changed our pattern of results.

Bayesian analyses

To determine whether our results provide evidence in support of the null hypothesis (i.e., that task performance during acquisition inter-trial periods does not affect MOGS), we employed 5 one-way Bayesian ANOVAs. These Bayesian ANOVAs contrasted group performance defined by acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, acquisition rate, retention, and MOGS. We report the results in terms of Bayes Factor (BF01), indicating the likelihood that results are in favor of the null hypothesis. Here, a BF01 of between 0 and 0.33, 0.33-3, or 3–10 indicates evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis, inconclusive evidence, and evidence in favor of the null hypothesis, respectively.

Post-hoc analysis of power for between-group comparisons

Our results revealed no significant between-group differences in MOGS, suggesting that our experiment may not have been adequately powered enough to observe such differences. To determine whether this was the case, we evaluated whether we should add additional subjects and retest our hypotheses or whether doing so would be unreasonable given the observed effect size. To perform this analysis, we first calculated the group effect size by dividing the coefficient estimate for the group effect by the pooled standard deviation of MOGS. We then calculated the required sample size to achieve β = 0.85 using this effect size and setting α to 0.05.

Interactions between associative memory and ESL

Our results suggested that the ENC group experienced greater variability in MOGS than the other groups. Therefore, we asked whether our results were influenced by interactions between associative memory and ESL. To this end, we regressed the number of successfully recognized word pairs against acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, acquisition rate, retention, and MOGS using two-tailed Pearson’s correlations. These analyses were performed separately for the ENC and SEM groups. Z-tests were used to statistically contrast the correlations between the ENC and SEM groups.

Results

Reproducing the findings of Bönstrup et al.11

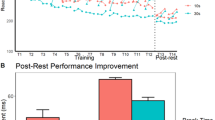

We first determined whether we were able to reproduce evidence of MOGS during early learning (the first 11 trials) in our REST group. MOGS are calculated by subtracting the KPS of the last correct sequence of one trial from the KPS of the first correct sequence of the next trial and have been proposed to reflect a rapid form of offline consolidation11. We also tested for evidence of MOnGS, which are calculated by subtracting the KPS of the first correct sequence of one trial from the KPS of the last correct sequence of the same trial. We found that MOGS during early learning were significantly greater than zero (0.47 ± 0.08 ΔKPS; t(14) = 3.26, p = .003), MOnGS were significantly smaller than zero (-0.31 ± 0.07 ΔKPS; t(14) = -1.88, p = .04), and MOGS were significantly greater than MOnGS (t(14) = 2.60, p = .01). We thus reproduced the findings of Bönstrup et al.11. To ensure that we were sufficiently powered to show evidence of MOGS with 15 participants in the REST group, we performed a post-hoc power analysis comparing MOGS for early learning against zero. Using the observed effect size of d = 0.842, α = 0.05, and a sample size of 15, this analysis revealed that we achieved power equal to 0.858, indicating sufficient power to identify MOGS.

Investigating group differences in MOGS

The three groups differed in whether they rested (REST), explicitly encoded associative memories (ENC), or made semantic judgments (SEM) during the acquisition inter-trial periods. We predicted that rest was necessary for MOGS and that the ENC and SEM groups would show significantly reduced MOGS compared to the REST group. We also explored whether explicitly engaging associative memory encoding processes would significantly reduce MOGS. We therefore predicted that MOGS would be significantly smaller in the ENC group compared to the SEM group. However, we did not identify a significant effect of GROUP on MOGS (t(433) = -0.21, p = .832; Fig. 2A). The main effect of INTERTRIAL period (t(433) = -1.26, p = .208) and the interaction (t(433) = 1.85, p = .066) were also not significant. A direct t-test between the REST (0.30 ± 0.07 ΔKPS) and ENC (1.39 ± 0.11 ΔKPS) groups revealed no significant difference in MOGS (t(14.36) = -1.18, p = .26). A direct t-test between the ENC (1.39 ± 0.11 ΔKPS) and SEM (0.90 ± 0.11 ΔKPS) groups was also not significant (t(19.07) = -0.65, p = .53). These results do not support the hypothesis that rest or associative memory processes are necessary for MOGS.

Between group analyses. (A) Micro offline gains across acquisition trials for the REST (black), ENC (blue), and SEM (red) groups across trials. Shaded areas represent the standard error of the mean. Vertical grey line divides early learning (left) from late learning (right). (B) Same plot as (A) except for micro-online gains (C) The average number of correct sequences performed. Shaded areas represent the standard error of the mean. (D) Violin plots of retention gains (in number of correct sequences) for each group. Boxplot and whiskers represent the upper and lower quartiles. Black lines and white dots represent the median and means, respectively.

Evaluating the effect of break point on MOGS

To determine whether the break point that defines early and late learning during acquisition affected the presence of group-level differences in MOGS, we performed a linear-mixed effects model analysis that included the number of trials used to calculate MOGS as a covariate. Specifically, the dependent variable was average MOGS calculated across different number of trials (i.e., break points) per subject, GROUP was a fixed effect, trial number was a covariate, and SUBJECT was a random intercept. We reasoned that if the choice of break point significantly influenced group differences in MOGS, then we should observe a significant GROUP effect when statistically controlling for the number of trials used to calculate MOGS. However, the GROUP effect did not reach significance (p = .39).

Investigating group differences in MOnGS

We calculated MOnGS using the first 11 acquisition trials. We did not identify a significant effect of GROUP (t(477) = 0.3, p = .76; Fig. 2B) or TRIAL (t(477) = 0.72, p = .47) on MOnGS. We did identify a significant interaction between GROUP and TRIAL (t(477) = -2.00, p = .046). A direct t-test between the REST (-0.23 ± 0.05 ΔKPS) and ENC (-1.29 ± 0.14 ΔKPS) group also revealed no significant difference in MOnGS (t(14.38) = 1.18, p = .26). A direct t-test between the ENC (-1.29 ± 0.14 ΔKPS) and SEM (-0.79 ± 0.13 ΔKPS) group was also not significant (t(19.63) = 0.67, p = .51). MOnGS was also inversely correlated with MOGS (r(9) = -0.87, p = .0005).

The significant interaction suggests that MOnGS progressively decreased across early learning trials for the ENC and SEM groups. To determine whether this was the case, we separated the analysis by group and examined the effect of TRIAL using three linear mixed-effects model analyses with SUBJECT as a random intercept. We found a significant effect of TRIAL for the ENC (t(162) = -2.35, p = .02) and SEM (t(151) = -2.21, p = .029) groups, but not the REST group (t(162) = -0.13, p = .90). These results indicate that performing a task during the inter-trial periods significantly reduced MOnGS across early learning.

Motor skill acquisition and retention

We measured ESL acquisition by fitting 3-parameter exponential curves to participant-level data, where the acquisition asymptote indexes the predicted maximum number of correct sequences achieved, acquisition magnitude indexes the difference between initial and asymptotic performance, and acquisition rate indexes the number of trials needed to reach acquisition asymptote. Additionally, we measured retention scores as the difference in the average number of correct sequences performed during the nine retention trials (after the 30-minute rest period) and the last six acquisition trials. Descriptive statistics for acquisition asymptote, magnitude, and rate and retention are shown in Table 1. Raw data are shown in Fig. 2C. Three separate one-way ANOVAs contrasting the acquisition parameters across groups revealed no significant differences (acquisition asymptote F(2, 41) = 0.17, p = .84; acquisition magnitude: F(2, 41) = 1.29, p = .29; acquisition rate: F(2, 41) = 0.83, p = .43). There were no significant differences in skill retention (i.e., consolidation) between groups (F(2,41) = 0.01, p = .99; Fig. 2D). These results do not support the hypothesis that rest during inter-trial periods is necessary for ESL acquisition.

Bayesian analyses

We performed five one-way Bayesian ANOVAs contrasting acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, acquisition rate, retention, and average MOGS (calculated across the first 10 inter-trial periods) between groups. Our results showed moderate evidence (3 < BF01 < 10) in favor of the null hypothesis over the alternative hypothesis for acquisition asymptote (BF01 = 5.32 ± 0.03%), acquisition rate (BF01 = 3.37 ± 0.04%), and retention (BF01 = 5.94 ± 0.03%), but not for acquisition magnitude (BF01 = 2.47 ± 0.02%). That is, a model consistent with the null hypothesis is moderately better at explaining the shape of the acquisition curves and retention scores than a model that includes GROUP as a factor. Further, the Bayesian ANOVA for MOGS showed moderate evidence in favor of the null hypothesis (BF01 = 3.26 ± 0.02%). Overall, these results do not support the hypothesis that rest is necessary for ESL or MOGS.

Post-hoc power analysis

To evaluate whether we were underpowered to identify differences between the REST, ENC, and SEM groups in the current study, we performed a post-hoc power analysis using the data acquired in this study. Using the effect size calculated from our MOGS analysis (d = -0.036) and assuming α = 0.05 and power (1-β) = 0.85, we would have an 85.2% chance of revealing significant group differences with a total of 42,526 participants (~ 14,175 per group). Thus, assuming group differences exist we would have to increase our sample size by thousands of participants to see these differences. Note also that since MOGS were greater in the ENC and SEM groups, this difference would support the hypothesis that task performance improves rather than degrades MOGS. This post-hoc analysis suggests that our findings were not caused by insufficient sample size.

Exploring interactions between associative memory and motor skill learning

Memory performance was assessed by a memory probe after the ESL task. During this probe, participants in the ENC and SEM groups were instructed to correctly identify the word that was paired with a cue during acquisition. Participants in the ENC and SEM groups successfully encoded associative memories (ENC proportion correct = 0.59 ± 0.05, t(14) = 12.66, p = 2.33 × 10− 9; SEM proportion correct = 0.57 ± 0.05, t(13) = 9.18, p = 2.40 × 10− 7), showing performance significantly above chance. Performance did not differ between the two groups: t(27) = 0.21, p = .83.

Our results suggested that the ENC group experienced higher variation in MOGS compared to the REST group. Our post-hoc analysis revealed that the coefficient of variation was twice as high for the ENC (2.47%) group compared to the REST group (1.18%). In response, we explored whether this variance was explained by episodic memory encoding success by performing a post-hoc analysis of the relationship between the number of associative memories that were successfully encoded and (1) motor skill acquisition, (2) motor skill retention, and (3) MOGS.

Associative memory performance and motor skill acquisition

For the ENC group, we identified a significant positive correlation between associative memory performance and acquisition asymptote (r(13) = 0.78, p = .0005; Fig. 3A) and acquisition magnitude (r(13) = 0.59, p = .02; Fig. 3B) but not acquisition rate (r(13) = -0.10, p = .73; Fig. 3C). For the SEM group, we did not identify significant relationships between associative memory performance and acquisition asymptote (r(12) = -0.36, p = .20; Fig. 3A), acquisition magnitude (r(12) = -0.39, p = .165; Fig. 3B), or acquisition rate (r(12) = 0.05, p = .86; Fig. 3C). The correlation for the ENC group was significantly more positive than that for the SEM group for acquisition asymptote (Z = 3.45, p = .0003; Fig. 3A) and acquisition magnitude (Z = 2.61, p = .0046; Fig. 3B), but not for acquisition rate (Z = -0.36, p = .64; Fig. 3C). These results indicate that participants in the ENC group who were able to successfully encode associative memories during inter-trial periods also performed well on the ESL task.

Associative memory encoding success and motor learning. Data points and trend lines are shown for the ENC (blue) and SEM (red) groups. Panels represent correlations between memory performance and (A) acquisition asymptote, (B) acquisition magnitude, (C) acquisition rate, (D) retention, and (E) MOGS. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Associative memory performance and motor skill retention

We did not identify a significant correlation between associative memory performance and motor skill retention for the ENC (r(13) = 0.44, p = .10; Fig. 3D) or SEM (r(12) = -0.36, p = .20; Fig. 3D) groups. However, the correlation for the ENC group was significantly greater than the correlation for the SEM group (Z = 2.04, p = .021; Fig. 3D).

Associative memory performance and MOGS

Associative memory performance positively correlated with MOGS for the ENC group (r(13) = 0.70, p = .004; Fig. 3E) but not the SEM group (r(13) = 0.22, p = .44; Fig. 3E), and the correlation for the ENC group was marginally stronger than the correlation for the SEM group (Z = 1.54, p = .062; Fig. 3E). These results provide provisional support for the notion that participants with better associative encoding performance also show greater MOGS.

Discussion

Forty-five participants were divided evenly into three groups. All participants performed an ESL task for 24 10-second trials, with each trial separated by 10-second inter-trial periods. After a 30-minute break, all participants performed nine retention blocks. The three groups differed only in whether they rested (REST), intentionally encoded associative memories (ENC), or made semantic judgments (SEM) during the inter-trial periods. We reasoned that if MOGS is supported by wakeful rest during inter-trial periods, then engaging in any task that requires concentration should diminish MOGS. We therefore predicted that the ENC and SEM groups would show significantly smaller MOGS than the REST group. Additionally, we explored whether MOGS relies on associative memory processes, expecting that the ENC group would show significantly smaller MOGS than the SEM group. However, our results did not support either prediction. When comparing the number of correct sequences performed across acquisition trials, we also identified no group differences in acquisition asymptote, acquisition magnitude, or acquisition rate, nor any group differences in retention. Finally, our Bayesian analysis favored the null hypothesis that acquisition asymptote, acquisition rate, retention, and MOGS do not differ between groups. Overall, our findings do not support the hypothesis that MOGS require wakeful rest.

The lack of differences in MOGS across groups observed here is surprising given that the most salient feature of MOGS is that it develops over a period of wakeful inter-trial rest. Two potential hypotheses arise from these results. The first possibility is that MOGS relies on time away from the ESL task rather than rest per se. The second possibility is that MOGS reflect changes in motor performance between ESL trials rather than skill learning. Of note, a defining principle of motor skill learning is that changes in motor performance are not always indicative of learning33. If MOGS reflect motor performance rather than motor learning, one would predict that continuously performing the ESL task without any inter-trial rest periods would produce the same amount of motor learning as participants who do receive inter-trial rest periods. In contrast, if MOGS do represent motor learning, eliminating inter-trial rest periods should significantly degrade overall motor learning. Interestingly, a recent pre-published study identified no evidence that eliminating inter-trial rest periods during an ESL task degrades motor learning34. While this approach may offer a “purer” test of the necessity of rest in MOGS and motor learning, we did not include a “no inter-trial period” group in the current study because it would eliminate the possibility of measuring MOGS and also produce group-level differences in fatigue. Moreover, we argue that while entirely eliminating inter-trial periods would be the strongest manipulation possible to test the role of rest in MOGS, our data suggest that the manipulations used in our study were strong enough to significantly reduce rest. Specifically, memory performance in the ENC and SEM groups was 60 and 57%, respectively, which are significantly above chance (25%) but well below ceiling (100%). Furthermore, participants who performed poorly on the memory test showed lower levels of MOGS, which contradicts the idea that disengaging from the inter-trial task promotes MOGS. Together, these results strongly suggest that participants in the ENC and SEM groups were actively engaged during the inter-trial periods and are more closely aligned with the null hypothesis (i.e., that MOGS does not require rest) than the alternative hypothesis (i.e., that performing a task during inter-trial periods decreases MOGS).

We also measured MOnGS and tested whether they differ between groups but did not find an effect of GROUP. We did, however, observe a significant interaction between GROUP and TRIAL, and post-hoc tests indicated that MOnGS decreased across the early learning period for the ENC and SEM groups, but not the REST group. This finding suggests that engaging in a task during inter-trial periods disrupts MOnGS. However, it is important to note that we did not see any meaningful differences in acquisition curve shape or retention between groups. Thus, the drop in MOnGS in early learning likely represents performance- rather than learning-related effects. This is not a particularly surprising finding, given that participants in the ENC and SEM group were required to switch between cognitive and motor tasks.

Based on previous work implicating medial temporal lobe activity in MOGS and associative memory, we investigated the role of associative memory processes in skill acquisition15,22. However, we observed no statistically meaningful difference in ESL or MOGS between the ENC and SEM groups, suggesting that associative memory processes do not contribute to ESL or MOGS. However, this result must be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, although only the ENC group was explicitly told to memorize the word pairs during the inter-trial periods, the post-ESL memory probe revealed nearly equivocal memory performance between the ENC and SEM groups. This result indicates that both groups engaged associative memory processes, such that any group differences cannot be interpreted as being caused specifically by associative memory processes. Instead, any group differences would either be due to the intentionality of the associative memory encoding, where the ENC group was explicitly told to encode the presented word pairs and the SEM group was not, or specific aspects of the semantic task and the cognitive processes it recruited that were not present in the memory encoding task. Second, although participants in the ENC and SEM groups were given explicit instructions to encode the word pairs and judge their semantic similarity, respectively, we cannot exclude the possibility that participants in the SEM group actively engaged associative memory processes or that the ENC group did not engage in these processes. As mentioned in the Methods, we did not collect verbal responses from participants during the inter-trial periods. This was done to equate non-specific task demands between groups. However, this also limited our insight into participants’ mental processes during these periods. Therefore, while our results may suggest that explicitly encoding associative memories does not affect ESL or MOGS, this can only be regarded as a provisional finding. Regardless of its role, the medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus are still indirectly implicated in MOGS13,15,16. To directly link hippocampal activity to MOGS, researchers could use causal methods in healthy humans, such as noninvasive brain stimulation. For example, applying repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the inferior parietal lobule reproducibly increases hippocampal network functional connectivity35,36,37 and produces corresponding increases in associative memory36,37,38. If the hippocampus and associative memory are indeed necessary for both MOGS and motor learning, one would expect that manipulating hippocampal network functional connectivity would produce corresponding changes in MOGS.

Surprisingly, we observed that the ENC group showed wide between-subject variation in MOGS and that variability was positively correlated with associative memory performance. Additionally, associative memory performance was also positively correlated with acquisition asymptote and acquisition magnitude. While these results suggest that associative memory processes may enhance ESL and MOGS and may even contradict the hypothesis that associative memory processes hinder MOGS, they must be interpreted within the broader context of our findings. First, we did not observe any significant differences in ESL or MOGS between the REST and ENC groups. Second, although the SEM group likely also engaged associative memory processes, the positive correlations observed for the ENC group were significantly stronger than the same correlations for the SEM group. Lastly, correlations involving small groups of participants must always be interpreted with caution39. Thus, we assert that rather than reflecting evidence that associative memory encoding boosts ESL and MOGS, the significant correlations for the ENC group simply reflect between-participant differences in general task performance. In other words, participants that explicitly encoded associative memories well also performed well on the ESL task. Thus, we are unable to draw strong conclusions regarding the role of associative memory processes in MOGS and motor learning.

Our study had several strengths, including our strict replication of the experimental design and analysis of the original study that revealed MOGS11 in the REST group. We were also able to confirm that participants in the ENC group successfully encoded associative memories using the post-ESL task memory probe. Finally, we performed Bayesian analyses to determine whether our results provide support for the null hypothesis that rest is not necessary for MOGS. Yet, our study also had several limitations. First, we used a lower number of participants (N = 15 per group) than the original report of MOGS (N = 3311). Our decision was based on an a priori power analysis showing that 15 participants was sufficient to observe significant evidence of MOGS in the REST group, and this was confirmed by our post hoc analysis of achieved power. Additionally, to investigate whether the lack of differences in MOGS between groups findings were due to our sample size, we performed a post hoc sample size analysis using the effect size drawn from our group analysis. This analysis revealed that we would need tens of thousands of participants to identify potential group differences. Further, because performance was slightly higher in the ENC and SEM groups compared to the REST group, any potential group differences would be in favor of inter-trial task performance boosting MOGS, which does not support the hypothesis that wakeful rest is necessary for MOGS. Furthermore, Bayesian analyses revealed that a null model explains our results significantly better than one that includes group as a factor. We are therefore confident that our study was sufficiently powered to test our hypotheses despite only using 15 participants per group. Second, we did not interrogate participants’ mental processes occurring during the inter-trial periods, which means that we cannot know what processes were engaged during these periods. However, given that both the ENC and SEM groups performed above chance during the post-ESL memory probe, we can conclude that both groups engaged associative memory processes during the inter-trial periods. Moreover, the fact that performance on the memory probe was only ~ 60% for both groups (chance = 25%) suggests that the inter-trial ENC task was demanding enough to prevent ceiling-level performance. Thus, while we cannot know the exact mental processes participants engaged during the intertrial periods, it is unlikely that the task demands were not strong enough to test our hypotheses. Finally, our ability to detect an effect of task engagement during inter-trial rest periods on motor learning and MOGS may have been hindered by using a between-subjects, rather than a within-subjects, design. Our motivation to use a between-subjects design was to maintain a close replication of Bönstrup et al.11. However, a within-subjects design could have afforded greater statistical power by reducing noise associated with individual differences. Future studies investigating the role of rest in MOGS may benefit from such an experimental design.

Relearning motor skills is paramount to motor recovery for individuals with sensorimotor network damage. MOGS represents a potential point of interest for the treatment of these individuals. However, in our study, we did not identify any convincing evidence that wakeful rest is necessary for either motor skill acquisition or MOGS. Specifically, we identified no significant differences in ESL performance or MOGS when comparing three groups that were instructed to either rest, encode associative memories, or make semantic judgments during inter-trial periods. Overall, our findings raise the hypothesis that MOGS represent inter-trial differences in motor performance rather than learning or consolidation.

Data availability

Raw data in tabular format, MATLAB code, and JASP output are freely available on GitHub with instructions: https://github.com/mfreedberg84/Rest_and_MOGS.

References

Debas, K. et al. Brain plasticity related to the consolidation of motor sequence learning and motor adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 17839–17844 (2010).

Dayan, E. & Cohen, L. G. Neuroplasticity subserving motor skill learning. Neuron 72, 443–454 (2011).

Walker, M. P. & Stickgold, R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron 44, 121–133 (2004).

Krakauer, J. W. & Shadmehr, R. Consolidation of motor memory. Trends Neurosci. 29, 58–64 (2006).

Robertson, E. M. New insights in human memory interference and consolidation. Curr. Biol. 22, (2012).

Walker, M., Brakefield, T., Hobson, J. & Stickgold, R. Dissociable stages of human memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Nature 425, 616–620 (2003).

Brown, R. & Robertson, E. Off-line processing: reciprocal interactions between declarative and procedural memories. J. Neurosci. 27, 10468–10475 (2007).

Karni, A. The acquisition of perceptual and motor skills: A memory system in the adult human cortex. Cogn. Brain Res. 5, 39–48 (1996).

Gupta, M. W. & Rickard, T. C. Comparison of online, offline, and hybrid hypotheses of motor sequence learning using a quantitative model that incorporate reactive Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 14, (2024).

Albouy, G. et al. Both the hippocampus and striatum are involved in consolidation of motor sequence memory. Neuron 58, 261–272 (2008).

Bönstrup, M. et al. A rapid form of offline consolidation in skill learning. Curr. Biol. 29, 1346–1351e4 (2019).

Bönstrup, M., Iturrate, I., Hebart, M. N., Censor, N. & Cohen, L. G. Mechanisms of offline motor learning at a microscale of seconds in large-scale crowdsourced data. Npj Sci. Learn. 5, (2020).

Jacobacci, F. et al. Rapid hippocampal plasticity supports motor sequence learning. PNAS 117, 23898–23903 (2020).

Gann, M. A., Dolfen, N., King, B. R., Robertson, E. M. & Albouy, G. Prefrontal stimulation as a tool to disrupt hippocampal and striatal reactivations underlying fast motor memory consolidation. Brain Stimulat. 16, 1336–1345 (2023).

Buch, E. R., Claudino, L., Quentin, R., Bönstrup, M. & Cohen, L. G. Consolidation of human skill linked to waking hippocampo-neocortical replay. Cell Rep. 35, (2021).

Mylonas, D. et al. Maintenance of procedural motor memory across brief rest periods requires the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 44, (2024).

Ritchey, M., Libby, L. A. & Ranganath, C. Cortico-hippocampal systems involved in memory and cognition: the PMAT framework. In Progress in Brain Research (eds O’Mara, S. & Tsanov, M.) Vol. 219, 45–64 (Elsevier B.V., 2015).

Ranganath, C. & Ritchey, M. Two cortical systems for memory-guided behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 713–726 (2012).

Freedberg, M., Toader, A., Wasserman, E. & Voss, J. Competitive and cooperative interactions between medial temporal and striatal learning systems. Neuropsychologia 136, 107257 (2020).

Albouy, G. et al. Maintaining vs. enhancing motor sequence memories: respective roles of striatal and hippocampal systems. NeuroImage 108, 423–434 (2015).

Schapiro, A., Gregory, E., Landau, B., McCloskey, M. & Turk-Browne, N. The necessity of the medial temporal lobe for statistical learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 1736–1747 (2014).

Schapiro, A. C., Turk-Browne, N. B., Norman, K. A. & Botvinick, M. M. Statistical learning of temporal community structure in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 26, 3–8 (2016).

Staresina, B. P. & Davachi, L. Mind the gap: binding experiences across space and time in the human hippocampus. Neuron 63, 267–276 (2009).

Walker, M. P., Brakefield, T., Morgan, A., Hobson, J. A., & Stickgold, R. Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron 35(1), 205-211 (2002).

Censor, N., Dimyan, M. A., & Cohen, L. G. Modification of existing human motor memories is enabled by primary cortical processing during memory reactivation. Curr. Biol. 20(17), 1545-1549 (2010).

Hussain, S. J. et al. Phase-dependent offline enhancement of human motor memory. Brain Stimulat. 14, 873–883 (2021).

Nissen, M. J. & Bullemer, P. Attentional requirements of learning: evidence from performance measures. Cogn. Psychol. 19, (1987).

Hazeltine, E., Grafton, S. T. & Ivry, R. Attention and stimulus characteristics determine the locus of motor-sequence encoding A PET study. Brain 120, 123–140 (1997).

Psychology Software Tools, Inc. E-Prime. (2016).

Hardwicke, T. E., Taqi, M. & Shanks, D. R. Postretrieval new learning does not reliably induce human memory updating via reconsolidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113, 5206–5211 (2016).

The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB. The MathWorks Inc.

JASP TEAM. JASP. (2024).

Schmidt, R., Lee, T., Winstein, C., Wulf, G. & Zelaznik, H. Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis, vol. 51 (Human Kinetics, 2019).

Das, A., Karagiorgis, A., Diedrichsen, J., Stenner, M. P. & Azañón, E. Micro-offline gains convey no benefit for motor skill learning. Biorxiv (2024).

Freedberg, M. et al. Persistent enhancement of hippocampal network connectivity by parietal rTMS is reproducible. eNeuro 6, ENEURO0129–192019 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Targeted enhancement of cortical-hippocampal brain networks and associative memory. Science 345, 1054–1057 (2014).

Warren, K. N., Hermiller, M. S., Nilakantan, A. S. & Voss, J. L. Stimulating the hippocampal posteriormedial network enhances task-dependent connectivity and memory. eLife 8, 1–21 (2019).

Freedberg, M. V., Reeves, J. A., Fioriti, C. M., Murillo, J. & Wassermann, E. M. Reproducing the effect of hippocampal network-targeted transcranial magnetic stimulation on episodic memory. Behav. Brain Res. 419, (2022).

Yarkoni, T. Big correlations in little studies: inflated fMRI correlations reflect low statistical power—Commentary on Vul et al. (2009). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 294–298 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lucas Hussain Freedberg for his essential feedback during the writing process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing (original draft), Writing (review and editing), Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. NA: Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing (review and editing), Visualization, Project administration. SJH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing (review and editing). TS: Investigation, Writing (review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, N.I., Suresh, T., Hussain, S.J. et al. Investigating the effect of task engagement during intertrial rest periods on micro offline gains. Sci Rep 15, 37396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21351-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21351-5