Abstract

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) comprehensively detects DNA sequence variation, enabling assessment of genetic disorders. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the diagnostic utility of WGS for pediatric musculoskeletal disorders by comparing it with whole exome sequencing (WES), which is more widely used but not as comprehensive in its coverage of the genome. This multi-center cohort study consists of WGS and WES analysis for 36 pediatric patients with musculoskeletal disorders of unknown etiology and, where available, their parents and siblings. WGS and WES were performed on DNA extracted from saliva samples. Secondary analysis of sequence data and tertiary analysis with interpretation of sequence variants were performed using the Illumina DRAGEN and Emedgene platforms, respectively. We evaluated 36 patients, and the median age was 11 years. The most common phenotypes included thoracolumbar scoliosis and gait disturbance. The median number of candidate variants per patient identified by WES and WGS were 57.5 and 90.5, respectively. 38 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified by WGS, providing a potentially diagnostic (tier-1) candidate for 22 of 36 (61.1%) patients. 12 of the 38 tier-1 variants (31.6%) were identified only by WGS. Of these 12 variants missed by WES, two candidates had variants that are likely to solve the respective case after undergoing manual curation. WGS resulted in a larger number of variants predicted as pathogenic/likely pathogenic in patients with musculoskeletal phenotypes, including variants potentially capable of solving their respective cases. WGS showed particular advantage in detecting CNVs. This study demonstrates that WGS is a promising method for improving our understanding of musculoskeletal disorders marked by genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a comprehensive test capable of detecting multiple variant types in coding and noncoding regions of genomes1,2. In clinical applications, WGS typically increases diagnostic rates over chromosomal microarray (CMA), targeted panel sequencing, or whole-exome sequencing (WES) across a range of patient populations and clinical phenotypes3,4,5,6,7. Its discovery and diagnostic utility—along with its streamlined laboratory workflow and decreasing cost—has piqued interest in WGS as a first- or second-line genetic test8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Consequently, there are numerous government initiatives for improved clinical access to WGS12,15. Furthermore, public- and private-payer health insurance companies increasingly cover WGS-related costs as evidence of its power and advantages accrues16. In research applications, WGS offers an opportunity to better understand the genomics and underlying molecular mechanisms of rare pediatric disorders, which have largely lacked scientific investigation1,10,17,18. A paucity of understanding regarding the cause of these genetic disorders undermines the ability of clinicians to screen and treat patients with rare diseases. While NGS is very promising for both clinical and research applications, many inconsequential variants are produced during WES and especially WGS analysis. Therefore, various tertiary analysis software platforms have emerged to help genome scientists prioritize variants19. Whether the improved yield of WGS over WES translates into a higher yield of interesting variants when paired with tertiary analysis platforms for prioritization is not extensively documented.

The neurological, muscular, and skeletal systems are functionally linked. Therefore, many musculoskeletal disorders are heterogeneous because they can arise from functional disruption in any combination of the three systems. For example, scoliosis can be congenital (e.g., caused by a skeletal malformation of vertebrae), secondary to another disorder (e.g., degenerative joint disease), or idiopathic. Most cases (~ 80%) of pediatric scoliosis are idiopathic, for which several heterogenous mechanisms have been proposed including dysfunction in neurological, skeletal and/or muscular cell proliferation or differentiation, estrogen receptor asymmetry or dysfunction, proprioception deficiency, immune dysfunction, or nutritional deficiency20,21,22,23. Differential diagnoses in musculoskeletal disorders can also be difficult to discern due to overlapping clinical manifestations. For example, Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies result from pathogenic variants within the dystrophin-encoding gene, dmd. Limb girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs) are genetically heterogeneous but may be misdiagnosed as Becker muscular dystrophy, delaying patients’ diagnostic odysseys24,25,26.

Shriners Children’s (SHC) has specialized in the treatment of pediatric neuromusculoskeletal disorders for more than one hundred years. In 2019, SHC initiated the Shriners Precision Medicine and Genomics (SPMG) project to research the genetic causes of disorders affecting our patients. To this end, we sequence genomes from across our hospital system. The resulting genomic database is currently comprised of sequencing data from more than 5,000 consenting patients with neuromusculoskeletal disorders and their first-degree biological family members. Approved projects, often with internal funding, can use the stored sequencing data to quickly facilitate research that unravels the genetic underpinnings of pediatric neuromusculoskeletal disorders and ultimately improves treatment outcomes. The primary aim of the present study was to compare the performance of WGS with that of WES within our research pipeline. Here, we present the findings for thirty-six probands with diverse neuromusculoskeletal disorders and discuss the potential of WGS for improving patient care.

Methods

Study cohort

Patients recruited for this multi-center, retrospective cohort study received care between July and October 2019 at an SHC site in Philadelphia, Puerto Rico, St. Louis, or Tampa. Eligible patients were ≥ 3 years of age, currently receiving medical care at SHC, and suspected of having a hereditary musculoskeletal disorder(s). To be included in the study the patient or their legally authorized representative had to be able to understand study instructions and provide informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had a physical or mental condition that prevented collection of saliva (e.g., xerostomia, facial abnormalities). Informed consent and patient assent were obtained from participants and their parent(s) or legally authorized representative(s) as applicable and conducted by SHC staff authorized to obtain consent for this study. Saliva collection was approved by the WCG Institutional Review Board, protocol number 20191503.

Sample collection

Saliva specimens were collected at participating SHC sites across 20 hospitals and clinics located in the USA, Canada and Mexico using the Oragene®·Discover OGR-600 or OGR-675 kits (DNA Genotek Inc.). All specimens were shipped in batches to the Shriners Children’s Genomics Institute where all lab work was completed. Upon receipt, saliva samples were vortexed and placed in an air incubator for 2 h at 50 °C for protein denaturation (including nucleases), then stored at room temperature until processed for nuclear DNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

DNA extraction

For WGS, saliva specimens were subjected to automated DNA extraction in the Chemagic™ 360 instrument (PerkinElmer, Inc.) using the Chemagic DNA Saliva 600 Kit H96 (catalog number CMG-1037, PerkinElmer, Inc.). For the WES approach, DNA extraction was performed manually utilizing the PrepIT•L2P DNA extraction kit (catalog number PT-L2P-5, DNA Genotek Inc.), following manufacturer’s protocol.

DNA quantifications were performed using fluorometric-based Qubit (catalog number Q33260, ThermoFisher Scientific, Invitrogen) and Quant-iT (catalog number Q33130, ThermoFisher Scientific) assays for the manual and automated extractions, respectively.

Library preparation

WGS libraries were constructed on the Zephyr® G3 NGS Workstation (Revvity, Inc.) using the Illumina® DNA PCR-Free Prep, Tagmentation kit (catalog number 20041795, Illumina, Inc.) and IDT® for Illumina® DNA/RNA UD Indexes Set A, Tagmentation and Set B, Tagmentation (catalog numbers 20027213, and 20027214, respectively, Illumina, Inc.) according to manufacturer’s specifications. Library quantifications were performed using the Invitrogen™ Quant-iT™ OliGreen™ ssDNA Assay Kit (catalog number O11492, ThermoFisher Scientific). WES libraries were constructed using the Nextera™ DNA Flex Pre-Enrichment Library Prep and Enrichment Reagents (catalog number 20025524; Illumina, Inc.) and IDT for Illumina UMI DNA Index Anchors (catalog number 20034701, Illumina, Inc.), according to manufacturer’s specifications. Library quantifications were performed using the Qubit 1X dsDNA HS Assay kit (catalog number Q33231, ThermoFisher Scientific).

DNA sequencing

WGS runs were performed on the NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc.) using the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit v1.5 (catalog number 20028312, Illumina, Inc.) for paired-end reads (2 × 150 cycles), aiming at a targeted average depth of 30x. Samples that did not reach the minimum average depth of 27x were subjected to additional sequencing to reach or surpass that threshold. WES was performed on the NextSeq 500DX sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc.) using the NextSeq 500/550 High Output Kit v2.5 (catalog number 20024907) for parallel sequencing of pooled libraries (2 × 74 cycles) aiming for 100x coverage.

Data analysis

WGS data were processed using a combination of Illumina® BaseSpace™ Sequence Hub and Illumina® Connected Analytics (ICA; Illumina, Inc.). FastQ reads for WGS and WES were uploaded to the Emedgene platform (v. 34.0.2) where they underwent alignment and variant calling with DRAGEN 4.2.4. Cases were excluded if WGS coverage was less than 27x or WES coverage was less than 55x. Family members needed to pass relatedness metrics, including relatedness coefficient, to be included27. Tertiary analysis was carried out using the Emedgene platform and included variant annotation and prioritization in conjunction with clinical information for each patient using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms. Additional details on analysis within the platform and candidate curation can be found in the supplemental methods.

Results

36 patients were identified with at least 55x mean coverage for WES (median coverage 69.3x) and at least 27x coverage for WGS (median coverage 37.4x) (See Supplemental Table 1, Additional File 1). The median age was 11 years (range 3–21), 21 (58.3%) were female, 30 (83.3%) identified as White, non-Hispanic, and 19 (52.8%) were enrolled as a proband-parent duo (See Supplemental Table 2, Additional File 1). 34 patients had at least one family member, and 45 unique family members were included in total.

The median relatedness coefficient of patients with first degree relatives was 0.50 and 0.46 using WGS and WES, respectively (p = 2.46e-10, Wilcoxon signed-rank), with a median deviation from expected relatedness of 0.01 and 0.04, respectively (See Supplemental Table 3, Additional File 1). One hundred fifteen unique HPO-coded phenotypes were assigned across all patients. 36 unique neuromusculoskeletal phenotypes were present in more than one patient and the most frequent phenotype was thoracolumbar scoliosis (25%) (Table 1).

Candidate variant curation

Using the WGS approach, all 36 cases resulted in more “most likely” candidates, and all but one sample had a higher number of candidate variants overall. The median number of candidate variants automatically curated per case for WGS and WES was 90.5 and 57.5, respectively. A median of 10 candidates per patient were automatically curated as “most likely” via WGS vs. a median of six via WES (p = 9.4e-7, Wilcoxon signed-rank, Fig. 1a). WES selected more candidates classified as benign, while WGS identified more pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), and uncertain significance (VUS) variants (Fig. 1B). Of the 3,832 unique variants found across all patients, 2,274 (59.3%) were found by both WGS and WES cases while 1,325 (34.6%) were found only by WGS and 233 (6.1%) were found only by WES (Fig. 1C). Of the 1,325 candidates found by WGS only, 20 (1.5%) were predicted to be “pathogenic”, 46 (3.5%) “likely pathogenic”, and 687 (51.8%) of uncertain significance. Of the 233 candidates found only by WES, 5 (2.1%) were predicted to be pathogenic, 43 (18.5%) likely pathogenic, and 93 (39.9%) of uncertain significance. There were no benign candidates selected by WGS only, while 4 benign candidates were selected by WES only. The overall respective rank of WGS and WES were positively correlated (rho = 0.93, p < 2.2e-16, Spearman’s Correlation), despite the lower number of WES candidates (Fig. 1D).

Comparison of WGS and WES. (A) Comparison of all predicted candidate variants (left) and predicted “most likely” candidate variants (right) between WES and WGS prior to curation. (B) Comparison of counts for each pathogenicity level for WES and WGS cases prior to curation; 479 variants with no assigned pathogenicity field (“NA” or “None”) were excluded. (C) Overlap of variants between corresponding WES and WGS cases prior to curation. (D) Comparison of Emedgene-assigned rank for corresponding WES and WGS cases when variant was present in both prior to curation. (E) Category of variant assignment within WES case for variants that were curated as first-tier (as defined in methods) within the corresponding WGS case.

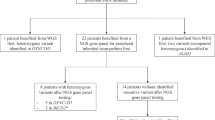

Potential diagnostic performance of WGS and WES

We used WGS data as a first-line approach to identify variants of interest. Out of a total of 36 patients, 26 (72%) had at least one first or second tier variant (Additional File 2). WGS identified 38 first-tier curated variants in 22/36 (61.1%) patients, and in 4 cases where no first-tier variants were selected, second-tier variants were present. Of the 38 first-tier variants, 26 (68.4%) were identified as candidates within the corresponding WES case (Fig. 1E; Tables 2 and 3). Of the 12 first-tier variants not recovered by WES, six were duplications or deletions, one was a small deletion, and five were SNVs (Tables 2 and 3). Five de novo variants were curated, one of which was among the first-tier candidates (Additional File 2). The one first-tier de novo variant was a 38 kb deletion in proband 21-0015-C that was not confirmed by WES (Table 3, Additional File 2).

Copy number variations for duchenne and becker muscular dystrophies

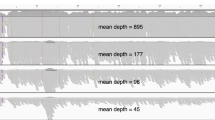

Four patients had muscular dystrophy as a phenotype, including one duo, one trio, and two siblings belonging to a quad. Hemizygous dmd deletions were observed in two male patients (22-0007-C and 22-0016-C). In neither instance was the dmd deletion detected by WES (Additional File 2). Both 22-0007-C and 20-0016-C inherited their respective dmd deletion from their mothers (Fig. 2). No candidate variant was identified in the 22-0014-C WGS case. However, one dmd stop-gain SNV (chrX:32644214 C > A) was missed in the WGS data due to low coverage (10x) but included as a candidate variant in the WES data where the variant depth was 29x (See Supplemental Fig. 1, Additional File 1). For 22-0007-C and 22-0016-C, read data was examined to confirm the presence of a dmd variant in the probands and their mothers (Fig. 2). Patient 22-0017-C is a female fraternal twin to 22-0016-C (WGS relatedness coefficient = 50.2%, IBS0 = 111) who also had a recorded muscular dystrophy phenotype but did not exhibit the same dmd variant, leading to an initial classification as tier-2 for 22-0017-C. Read alignment data appeared to show a reduction in reads for 22-0016-C around the predicted 31,782,619 start point and 31,896,448 end point, but no such reduction in reads was seen in 22-0017-C (Fig. 2E,F).

A DMD deletion in two cases. (A) Family pedigree with inheritance pattern of dmd variants in the case of proband 22-0007-C. Ref = Reference, Het = Heterozygous, Hemi = Hemizygous. Black nodes are documented as being affected. (B) Start point read placement and coverage for proband and both parents. Split reads are highlighted in red. (C) End point read placement and coverage for proband and both parents. Split reads are highlighted in red. (D) Family pedigree with inheritance pattern of dmd variants in the case of proband 22-0016-C. (E) Start point read placement and coverage for each sibling and both parents. Split reads are highlighted in red. (F) End point read placement and coverage for each sibling and both parents. Split reads are highlighted in red.

Potential enrichment bias within a case of compound heterozygosity

Proband 22-0009-C had the phenotypes of spastic paraplegia, cerebral palsy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In addition, both parents’ self-reported status indicated the presence of “myopathy”. Examination of the WGS data revealed two variants in als2 inherited in trans. Both als2 variants were SNVs, with the paternal chr2:201724392G > A (rs767,350,733) being a known stop gain mutation and classified as likely pathogenic in ClinVar, while the maternal chr2:201,726,484 C > T is a novel missense variant predicted as damaging and likely pathogenic by the annotation tool. Manual curation revealed that the novel variant has multiple lines of evidence of being deleterious including a Revel score of 0.95. It also has a low frequency in GnomAD (1.2E-6). Neither variant was detected as a candidate using the WES pipeline. However, when we removed quality filters, both als2 variants were present (Fig. 3A,B). Both variants had low depth (10x and 7x, respectively) despite an overall WES sample coverage of 79x (Fig. 3A,B, See Supplemental Table 2, Additional File 1), and had been removed due to low quality.

als2 variants in WGS and WES for 22-0009-C. pathogenic variants shown at locations (A) 201,724,392 and (B) 201,726,484 on chromosome 2 for proband and both parents within WGS and WES cases. Pedigrees are drawn above each variant with pedigrees denoting inheritance of respective variants. Coverage is group-scaled at 65x and 41x.

Discussion

Musculoskeletal disorders are a heterogeneous group of conditions that have a correspondingly diverse genetic pathophysiology and are often poorly characterized. The Shriners Children’s Precision Medicine and Genomics (SPMG) project aims to unravel the underlying genetic pathology of these disorders. Researchers and clinicians now frequently turn to WGS and WES technologies for the study and molecular diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders with some debate over which is more practical28,29. Although generally WES is less expensive to process per sample, it requires PCR amplification and hybridization capture, making it more labor-intensive and time-consuming. Meanwhile, the cost of WGS continues to decline as technology advances over the years, while the manual work is simpler and faster, reducing preparation time. To optimize our research protocol, we have performed a direct comparison of WES and WGS within an automated prioritization tool for the molecular diagnosis of neuromusculoskeletal disorders within our patient population.

In this study, WGS and secondary analysis resulted in a significantly higher number of candidate variants than analysis with WES data, with a significantly higher number of “most likely” predictions. WGS recovered 94% of all candidates identified by either technology, identifying 1,325 candidates that were not detected by WES. The increased risk of false positives associated with the larger number of variants returned by WGS is mitigated by modern tools that can quickly apply guided filtering for clinical relevance. Meanwhile, in cases where the causative variant is missed or eliminated for insufficient technical quality, prioritization programs may suggest spurious connections with variants despite little evidence of pathogenicity. This may explain why WES identified more candidate variants classified as benign. In some cases, viable candidates may be missed entirely.

Among the 38 first-tier candidate variants identified by WGS in this study, 12 (31.6%) were not identified as candidates in the corresponding exome case (Fig. 1E; Tables 2 and 3). Of the five first-tier CNVs found by WGS, none were captured by WES (Table 3). While short-read technologies typically struggle to accurately call CNVs, the enrichment step of WES severely limits the ability to detect CNVs (especially deletions) because short-read CNV detection relies on breakpoint detection and relative read depth. This study’s lack of a panel-of-normals additionally limited detection of CNVs by read depth using WES and potentially contributed to an increase in errors or missed calls. The discrepancy in CNV detection between WES and WGS is noteworthy in the context of neuromuscular disorders where CNVs are frequently responsible for pathology30,31. As more non-SNV variants gain clinical annotation and CNV calling improves, the performance gap between WES and WGS will likely continue to grow29. While CMA is still widely considered the first-line test for detection or validation of suspected clinical CNVs, our study focused on comparing WGS and WES. Their highly scalable, streamlined nature is practical for our system-wide SPMG project and we were interested in determining which we should use as the first-line technology in our research context. Therefore, we did not include any CMA data. However, previous studies have demonstrated that WGS can result in comparable yield, increased flexibility and improved breakpoint detection over CMA32,33,34. Therefore, as WGS technology improves it may eclipse CMA as a first-line test. CNV reliability is also improving as long-read sequencing technologies are more widely adopted. The capacity of WGS to identify a broad range of genetic variant types in a single test maximizes the potential for acquiring clinically useful genetic information, potentially reducing serial clinical and laboratory investigations, shortening the diagnostic odyssey, and expediting etiology-based treatment6,35.

Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies are typically characterized by pathogenic variants in the dmd gene. Two patients (22-0016-C and 22-0007-C) had annotated muscular dystrophy phenotypes and had hemizygous partial or full deletions of the dmd gene inherited from a heterozygous mother (Fig. 2). The 1058.26 kb deletion in 22-0007-C encompasses the entire dmd gene and would likely lead to a Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy presentation. The 113.83 kb predicted deletion in 22-0016-C would encompass exons 48–50 which may be Becker muscular dystrophy but would require additional testing. The female sibling (22-0017-C) of patient 22-0016-C was negative for the respective dmd deletion. It is possible that 22-0017-C instead has another form of muscular dystrophy, such as limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, and was misdiagnosed. False positives for Becker muscular dystrophy have been documented previously24,25,26, and may be more common when a sibling has an altered dmd gene. However, it is also possible that the muscular dystrophy annotation for 22-0017-C was a recording error. Unfortunately, in-depth medical data was out of scope for this project, so we cannot confirm the annotated phenotypes or definitively state either conclusion. Considering this case, clinicians should manage sibling diagnostic odysseys with caution.

Five of the first-tier variants not detected by WES were SNVs. The exon enrichment step in WES leads to notoriously uneven coverage across the genome which can lead to missing important variants. This was highlighted in proband (22-0009-C) with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), spastic paraplegia, and cerebral palsy with a potential case of compound heterozygosity where neither SNV was detected by WES (Fig. 3, See Supplemental Table 2, Additional File 1). This pair of variants was previously identified by another team in a set of siblings using WES36, suggesting that some of the pitfalls of WES may be overcome by larger pedigrees. However, it is also possible that nuanced methodological differences shifted the specific areas that were enriched or that differences in quality filtering protocols led to more stringent filtering. Further, the use of saliva for our study as opposed to blood may be more detrimental to the quality of WES because saliva samples have shorter average fragment sizes and higher contamination with non-human DNA. Unpredictable coverage variability may lead to the loss of both known and novel SNVs, which compounds when multiple variants may contribute to the diagnosis. We also suspect the uneven coverage and lower frequency of variant calls within the WES dataset led to a significant, albeit slight, difference in relatedness between WES and WGS. Emedgene’s relatedness inference is based on the Peddy program and known SNVs27. The inability to consistently call SNVs at sufficient depth with WES data may result in a lower capacity for built-in quality control as well as a potential reduction in diagnostic value. Low coverage on variants can pose a problem within WGS cases as well (See Supplemental Fig. 1, Additional File 1). Setting coverage thresholds on regions of interest for reporting is essential to reduce false positives in settings where results will be reported to patients. Clinicians should be aware of test limitations, including WGS- or WES-based assays, and make sure the implications of these limitations are reported to patients with their results in a comprehensible manner by a qualified professional.

Among the 12 first tier candidates not detected by WES, two candidates are potentially clinically diagnostic after manual review of clinical criteria. These include one hemizygous DMD deletion in 22-0007-C, as well as two compound heterozygous candidates which were present in the als gene of 22-0009-C. A tier-2 dmd variant in 22-0016-C is also a highly probable candidate for the case which was also not identified by WES. Unfortunately, we cannot verify the phenotypes of these patients or validate the findings molecularly due to the study’s scope and limitations. The ability of variant prioritization tools to create a “short list” of variants researchers and clinicians can focus on remains a valuable tool. Teams can recognize variants of clinical interest while also extracting additional information from novel candidates for research purposes. However, analysts must be aware of the limitations of predictive tools and use judgment on their final selections. Clinical pipelines, especially, require a clear framework with rigorous validation and reporting of variants.

This study was a retrospective quality improvement study exploring the potential value of two methodologies prior to clinical implementation. Due to the lack of access to detailed medical records, thorough clinical analysis was limited. We did not acquire additional testing results such as chromosomal microarrays, genetic panels, or blood tests, and limited our analysis to WES and WGS data. Further, we assigned phenotypes (HPO codes) to the best of our ability based on assigned medical billing (ICD-10) codes and parental questionnaires obtained during enrollment. To mitigate limitations in clinical diagnosis, WES and WGS cases were phenotype-matched. Due to the project’s exploratory nature, both WES and WGS were optimized for overall coverage rather than coverage at targeted regions of interest, and some variants did not meet quality or coverage thresholds. Similarly, Emedgene was used in “discovery” rather than “focus” mode resulting in a higher number of candidate variants. Finally, we used an earlier version of the WES library preparation protocol, which has been improved in later iterations.

Conclusions

WGS combined with appropriate secondary and tertiary analytical tools demonstrated superior performance compared with WES and potentially resolved musculoskeletal cases occasionally missed by WES. WGS in the present pediatric population resulted in a pathogenic variant yield of 61.1%. WGS-based analysis resulted in a substantially higher number of candidate variants. WES missed 31.6% of the 38 tier-1 variants identified by WGS, including all five tier-1 CNVs. Overall, 34.6% of candidate variants were identified by WGS only. Based on this dataset, the Shriners Children’s Genomics Institute now uses WGS as the first line technology to study the genetic basis of all pediatric research and clinical applications.

Data availability

Access to sequencing data or emedgene cases may be granted upon reasonable request to the corresponding author on a case-by-case basis with the approval of SHC compliance and legal departments.

Abbreviations

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

- WGS:

-

Whole genome sequencing

- HPO:

-

Human Phenotype Ontology

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- CNV:

-

Copy number variant

- SV:

-

Structural variant

References

Pagnamenta, A. T. et al. Structural and non-coding variants increase the diagnostic yield of clinical whole genome sequencing for rare diseases. Genome Med. 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-023-01240-0 (2023).

Gloss, B. S. & Dinger, M. E. Realizing the significance of noncoding functionality in clinical genomics. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0087-0 (2018).

Lionel, A. C. et al. Improved diagnostic yield compared with targeted gene sequencing panels suggests a role for whole-genome sequencing as a first-tier genetic test. Genet. Med. 20, 435–443. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.119 (2018).

Abul-Husn, N. S. et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of genome sequencing versus targeted gene panel testing in Racially and ethnically diverse pediatric patients. Genet. Sci. 25, 100880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100880 (2023).

Group, N. I. S. et al. Effect of Whole-Genome sequencing on the clinical management of acutely ill infants with suspected genetic disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1218–1226. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3496 (2021).

Ewans, L. J. et al. Whole exome and genome sequencing in Mendelian disorders: a diagnostic and health economic analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 30, 1121–1131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01162-2 (2022).

Lindstrand, A. et al. From cytogenetics to cytogenomics: whole-genome sequencing as a first-line test comprehensively captures the diverse spectrum of disease-causing genetic variation underlying intellectual disability. Genome Med. 11, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-019-0675-1 (2019).

Manickam, K. et al. Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American college of medical genetics and genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 23, 2029–2037. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01242-6 (2021).

Clinical Genetics Group Of Medical Genetics Branch Chinese, Medical, A., Professional Committee For Prenatal Diagnosis Of Genetic Diseases Medical Genetics Branch Of Chinese Medical, Disease, A. G. O. G. & Birth Defect, P. C. [Expert consensus on the application of low-depth whole genome sequencing in prenatal diagnosis]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 36, 293–296. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2019.04.001 (2019). Control Committee Of Chinese Society Of Preventive.

Souche, E. et al. Recommendations for whole genome sequencing in diagnostics for rare diseases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 30, 1017–1021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01113-x (2022).

Smith, L. et al. Genetic testing and counseling for the unexplained epilepsies: an evidence-based practice guideline of the National society of genetic counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 32, 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1646 (2023).

Turro, E. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of patients with rare diseases in a National health system. Nature 583, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2434-2 (2020).

Dimmock, D. et al. Project baby bear: rapid precision care incorporating rWGS in 5 California children’s hospitals demonstrates improved clinical outcomes and reduced costs of care. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.05.008 (2021).

Bagger, F. O. et al. Whole genome sequencing in clinical practice. BMC Med. Genom. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-024-01795-w (2024).

Stark, Z. et al. Integrating genomics into healthcare: A global responsibility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.014 (2019).

Phillips, K. A. et al. US private payers’ perspectives on insurance coverage for genome sequencing versus exome sequencing: A study by the clinical sequencing Evidence-Generating research consortium (CSER). Genet. Med. 24, 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2021.08.009 (2022).

Jobanputra, V. et al. Advancing access to genome sequencing for rare genetic disorders: recent progress and call to action. Npj Genomic Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-024-00410-2 (2024).

Muurinen, M. et al. Mosaic deletions of known genes explain skeletal dysplasias with high and low bone mass. JBMR Plus. 6 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10660 (2022).

Bastida-Lertxundi, N. et al. Evaluating seven bioinformatics platforms for tertiary analysis of genomic data from whole exome sequencing in a pilot group of patients. Adv. Lab. Med. / Av. En Med. De Laboratorio. https://doi.org/10.1515/almed-2025-0031 (2025).

De Salvatore, S. et al. Exploring the association between specific genes and the onset of idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review. BMC Med. Genomics. 15, 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01272-2 (2022).

Kotwicki, T. et al. Estrogen receptor type 1 and type 2 presence in paravertebral skeletal muscles: expression level and relation to phenotype in children with idiopathic scoliosis. Genes (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13050739 (2022).

Lau, K. K. L. et al. Timely revisit of proprioceptive deficits in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Global Spine J. 12, 1852–1861. https://doi.org/10.1177/21925682211066824 (2022).

Batista, R. M. B. F. et al. Association between vitamin d levels and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Coluna/Columna 13 (2014).

Osman, H. et al. From doubt to diagnosis: Canadian patient perspectives on a Limb-Girdle muscular dystrophy diagnosis. Health Expect. 28, e70271. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.70271 (2025).

Duan, D., Goemans, N., Takeda, S., Mercuri, E. & Aartsma-Rus, A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis.Primers. 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00248-3 (2021).

Gatheridge, M. A. et al. Identifying Non–Duchenne muscular dystrophy–Positive and false negative results in prior Duchenne muscular dystrophy newborn screening programs: A review. JAMA Neurol. 73, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3537 (2016).

Pedersen, B. S. & Quinlan, A. R. Who’s Who? Detecting and resolving sample anomalies in human DNA sequencing studies with Peddy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 406–413 (2017).

Garg, B., Tomar, N., Biswas, A., Mehta, N. & Malhotra, R. Understanding musculoskeletal disorders through Next-Generation sequencing. JBJS Reviews 10 (2022).

Chung, C. C. Y. et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of exome and genome sequencing in pediatric and adult patients with rare diseases across diverse populations. Genet. Sci. 25, 100896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100896 (2023).

Winder, T. L. et al. Clinical utility of multigene analysis in over 25,000 patients with neuromuscular disorders. Neurol. Genet. 6, e412. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXG.0000000000000412 (2020).

Pennings, M. et al. Copy number variants from 4800 exomes contribute to ~ 7% of genetic diagnoses in movement disorders, muscle disorders and neuropathies. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 31, 654–662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01312-0 (2023).

Yang, M. et al. Diagnostic utility of whole genome sequencing after negative karyotyping/chromosomal microarray in infants born with multiple congenital anomalies. jkms 39, e250-250. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e250 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Whole-Genome sequencing is a viable replacement for chromosomal microarray and fragile X PCR Testing. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.24.25328260 (2025).

Collins, R. L. et al. A structural variation reference for medical and population genetics. Nature 581, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2287-8 (2020).

Akgun-Dogan, O. et al. Impact of deep phenotyping: high diagnostic yield in a diverse pediatric population of 172 patients through clinical whole-genome sequencing at a single center. Front. Genet. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2024.1347474 (2024).

Vanderver, A. et al. Whole exome sequencing in patients with white matter abnormalities. Ann. Neurol. 79, 1031–1037. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24650 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank patients and families who participated in this research study, as well as clinical workers who collected samples and consented patients. We would also like to thank Raye Alford for her valuable input on the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by Shriners Children’s.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMB: study design, data analysis, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision. AGG: study conception, study design, data acquisition, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision. AQ: study design, data analysis, manuscript revision. EE: data analysis. DQ: data analysis. SPS: study conception, study design, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision. HLS: manuscript drafting, manuscript revision. ML: manuscript drafting, manuscript revision. KS: study conception, study design, data acquisition, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ML, HLS, and SPS are employed by Illumina, Inc. The authors report no other competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent and patient assent were obtained from participants and their parent(s) or legally authorized representative(s) as applicable in person or through a virtual process conducted by SHC staff authorized to obtain consent for this study. The sample collection performed was approved by WCG Institutional Review Board, protocol number 2019150. All methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. The post-processing comparison of WES and WGS data was undertaken as a Quality Improvement Initiative at Shriners Hospitals for Children and, as such, was not formally supervised by an Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Informed consent and patient assent were obtained from participants and their parent(s) or legally authorized representative(s) as applicable and conducted by SHC staff authorized to obtain consent for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brashear, A.M., Gustafson, A.G., Quitadamo, A. et al. Improved genomic characterization of a clinically heterogeneous pediatric cohort with WGS vs. WES. Sci Rep 15, 37679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21421-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21421-8