Abstract

Neoagaro-oligosaccharides (NAOS) are degraded seaweed polysaccharides of low molecular weight and high water solubility. Currently, little information is available on the utility of NAOS for seed germination. Here, we investigated seed germination of garden cosmos under NAOS concentrations of 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 g/L and monitored the role of 1 g/L NAOS in physiology of germinating seeds and recovery from plant growth inhibitor stress. The results showed that 1 g/L NAOS maximized germination potential of seeds and hypocotyl length, along with increasing α-amylase and β-amylase activities and soluble starch and soluble sugar contents of seedlings. Radicle length and hypocotyl fresh weight showed progressive decrease with the increase in NAOS concentration. The optimal dose of NAOS (1 g/L) decreased abscisic acid level but increased the levels of auxins, gibberellins and strigolactones in germinating seeds. Addition of 1 g/L NAOS to germination medium alleviated the impact of different growth retardants on seed germination and seedling growth, particularly radicle dry weight. This study shows that exogenous NAOS can improve seed germination and alleviate the stress induced by growth retardants on garden cosmos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seed germination, an early and crucial stage of plant growth, represents a complex process regulated by many coordinated metabolic, cellular, genetic and environmental events in the spermatophyte life cycle1,2. It directly affects the rate of seedling emergence and harvest date which will determine the final yield, and thus has important economic and ecological significance3,4.

Plant hormones are key factors in the regulation of seed germination and serve as critical signaling molecules for transmitting environmental changes5,6,7. Previous studies indicate that abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellins (GAs) are the main hormones involved in seed germination, with ABA promoting seed dormancy and inhibiting germination, while GAs play the opposite roles that is breaking dormancy and promoting germination8,9. Furthermore, other signaling molecules such as auxins, cytokinins (CKs), jasmonates, brassinosteroids, ethylene and salicylic acid considerably contribute to seed germination10,11,12,13,14,15. Complex interactive effects have been reported between two or more hormones in controlling seed germination in different plant species16,17,18,19,20.

Oligosaccharides comprise a class of carbohydrates of two to ten identical or different monosaccharide residues connected by glycosidic bonds to form straight or branched chains, and the constituent units are mainly five- or six-carbon sugars21. By preserving the various activities of polysaccharides, the water solubility and bioavailability of oligosaccharides have been greatly improved22. Oligosaccharides exhibit various physiological properties and are employed in plant research. For example, chitosan oligosaccharides are used as a plant elicitor to promote plant growth and yield23,24, and can also induce resistance to plant diseases25, cold tolerance26, and salt tolerance27. Alginate oligosaccharides enhance resistance to pathogens, drought, salt, heavy metals, and other stressors in the postharvest storage28. Pectin-derived oligosaccharins increase postharvest quality and extend the vase life of lisianthus flowers29. Neoagaro-oligosaccharides (NAOS) are prepared as hydrolysates of agar, by breaking β-(1→4) bonds using β-agarase30,31. Although recent studies have revealed the role of oligosaccharides in regulating plant growth, postharvest quality, and improving plant stress resistance32,33,34, studies investigating the effect of NAOS application on seed germination are limited.

Garden cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.), family Asteraceae, is a beautiful, rich-colored ornamental annual35,36. It is widely used in urban and rural greening and park landscaping. In this study, to evaluate the effect of NAOS on seed germination of garden cosmos, we determined germination rate of seeds under varying NAOS concentrations, and monitored the role of NAOS in physiology of germinating seeds and recovery from stress induced by different plant growth inhibitors. The results provide a basis for the development of novel eco-friendly natural growth regulators for seed germination of garden cosmos and other horticultural crops.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Garden cosmos seeds (Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.) were purchased from Shuoya Garden Co., Ltd., Suqian City, Jiangsu Province, China. The seeds were stored in a plastic woven sack at room temperature until used in the experiments.

Plant growth regulators and chemicals

The following plant growth regulators were used in this study: ABA, code: CA1011; N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA, a key inhibitor of the directional (polar) transport of auxin, code: CN7710); paclobutrazol (PAC, an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthetic pathway, code: CP8121) and TIS 108 (a strigolactone-biosynthesis inhibitor, code: CT11200). The plant growth regulators were purchased from Beijing Coolaber Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). They were first prepared as stock liquor and then diluted to the appropriate working concentration in distilled water. NAOS, with neoagarotetraose and neoagarohexaose as the main ingredients, were provided by the Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Xiamen, China.

Seed germination under NAOS and growth inhibitors

According to the method of Dong et al. 1, seeds of garden cosmos were surface sterilized in 75% alcohol for 30 s and sodium hypochlorite for 5 min. Following this, they were rinsed 5–6 times in sterile distilled water and gently blotted on filter paper. The sterilized seeds were germinated on two layers of filter paper moistened with 4 mL distilled water or of treatment solutions in 90-mm diameter Petri dishes incubated in a constant temperature chamber of 22–25 ℃ with 16 h light/8 h dark. The experiment was performed with three replicates, each was a Petri dish containing 50 seeds. A radicle length of 2 mm was used as the criterion of germination. Seed germination was recorded daily for a period of 5 days, with daily addition of 1 mL of the treatment solutions. For the experiment evaluating the effect of NAOS concentrations, the germination rate was recorded under 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 g/L NAOS33. The germination percentage under 0 and 1 g/L NAOS treatments was recorded at 6 h intervals for a period of 48 h. To evaluate the impact of plant growth inhibitors on seed germination, the following concentrations of growth inhibitors were used: ABA (0, 10, 20, and 100 µM); PAC (0, 100, 200, and 500 µM); NPA (0, 250, 500, and 1000 µM); TIS108 (0, 10, 100, and 500 µM).

The germinative force and germination rate of seeds were assessed as the cumulative germination percentage on the 2nd and 5th days, respectively1,17,37,38. After five days of germination, the seedlings were harvested to measure length and fresh weights (FW) of hypocotyl and radicle, and were then dried to a constant weight for estimation of dry weights (DW). Seedling length was determined using Image J software (NIH, https://imagej.net/).

Recovery of seed germination from germination inhibitors by NAOS

Seeds were germinated on two layers of filter paper moistened with 4 mL of 20 µM ABA, 200 µM PAC, 1000 µM NPA, and 500 µM TIS108 in 90-mm diameter Petri dishes. From the 1 st to 4th d, 1 mL double distilled water (ddH2O, control) or 1 mL of 1 g/L NAOS (recovery) were added daily to each Petri dish. The germination percentage was assessed daily. The FW, DW, and length of hypocotyls and radicles were determined on 5 d.

Evaluation of germinating seed physiology

An aliquot of the germinating seeds (> 0.3 g) was sampled after 18 h of incubation in the 0 g/L and 1 g/L NAOS treatments. Specimens were frozen rapidly in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 ℃. The activities (U/g) of α-amylase and β-amylase, and the contents (mg/g) of soluble starch, and total soluble sugars were determined following the methods of plant assay kits (codes: BC0610, BC2040, BC0700, and BC0030) from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, China. One unit of enzyme activity (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the production of 1 milligram of reducing sugar per gram of tissue per minute.

Phytohormone quantification

Aliquots of the frozen germinating seeds were transported to Wuhan MetWare Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China; http://www.metware.cn/) to determine the hormone contents according to Wan et al.33. Three replicates of each assay were performed.

Statistical analysis

Seed images were processed using Image J. Microsoft Excel 2010, IBM SPSS Statistics 26, and GraphPad Prism 8 were used to statistically analyze and visualize the experimental data. The data are expressed as means ± SD. The significance of the differences between means (P < 0.05) was analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Duncan’s multiple range test.

Results

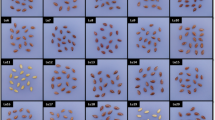

Seed germination of garden cosmos under different NAOS concentrations

Germination of garden cosmos seeds was obvious from the 1 st day in ddH2O, and the seedlings were fully extended by the 5th day (Fig. 1A). The cumulative germination percentage slowly increased from the 3rd to 5th day (Fig. 1B). Among the different NAOS concentrations, 1 g/L treatment had led to the highest germination rate during the early period of germination (up to the 3rd day), with no considerable differences among treatments on the 4th and 5th days (Fig. 1B, D, E). The 1 g/L NAOS treatment induced appreciable improvement in seed germination compared to 0 g/L NAOS treatment during the early period of germination (18–48 h) (Fig. 1C).

Germination of garden cosmos seeds in response to NAOS concentration. A Germination progress in ddH2O for a period of five days (Bar = 1 cm). B Time course of cumulative germination percentage of seeds treated with different NAOS concentrations. C Cumulative germination percentage of seeds treated with 0 and 1 g/L NAOS for 48 h. D Germinative force of seeds treated with different NAOS concentrations assessed as the cumulative germination percentage on the 2nd d. E Germination rate of seeds treated with different NAOS concentrations assessed as the cumulative germination percentage on the 5th d. Data are means ± SD of three replicates. Different letters and/or asterisks above data points indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

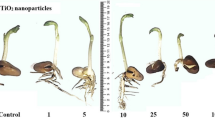

Effects of NAOS concentration on seedling growth of garden cosmos

Hypocotyl length of garden cosmos seedlings was significantly increased by 11.1% upon increasing NAOS concentration from 0 to 0.1 g/L, then decreased with further increase in NAOS concentration. By contrast, radicle length was decreased by 22.4% across the entire range of NAOS concentrations. Hypocotyl FW exhibited 5.5% reduction as NAOS concentration exceeded a threshold of 5 g/L up to 10 g/L. Radicle FW was increased by 16.7% with the increase in NAOS concentration from 0 to 0.01 g/L then declined with further increase in NAOS concentration. Hypocotyl DW was significantly lowered by 14.4% upon increasing NAOS concentration from 0 to 1 g/L, then increased with further increase in NAOS concentration; however, radicle DW was non-significantly affected by NAOS concentration (Table 1).

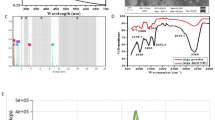

Effect of NAOS on the physiology of germinating garden cosmos seeds

Among the different NAOS concentrations, 1 g/L treatment led to the maximal germination percentage after 48 h of germination (Fig. 1D); therefore, we tested the effect of this treatment on the physiology of germinating seeds after 18 h of germination. The activities of α-amylase and β-amylase, as well as the contents soluble starch and total soluble sugars of seeds treated with 1 g/L NAOS were significantly increased by 158%, 27.6%, 9.5%, and 4.4%, respectively above the control (Fig. 2A-D).

In contrast to the 26% decrease in ABA content of germinating seeds treated with 1 g/L NAOS, the contents of IAA, IAA-ALA, GA1, GA19 and 5DS levels were increased by 61.2%, 115.3%, 27.3%, 34.9%, and 469%, respectively above the control (Table 2).

Effects of plant growth inhibitors on seed germination of garden cosmos

Table 2 reveals that the levels of endogenous ABA, auxins, gibberellins, and strigolactones had been considerably changed under 1 g/L NAOS relative to the control. Thus, we investigated the effects of graded concentrations of the relevant plant growth inhibitors on seed germination. As shown in Fig. 3, the effect of growth inhibitors on seed germination varied according to the type of inhibitor. The inhibition in seed germination under ABA and PAC was severe and dose-dependent, with stronger impact of ABA compared with PAC. Whereas 100 µM of ABA were sufficient to induce almost complete cessation of germination, the required concentration of PAC was 500 µM (Fig. 3A and B). The inhibition in seed germination by NPA was also dose-dependent but less severe than that caused by PAC, with the top concentration (1000 µM) leading to only 40% reduction in germination percentage (Fig. 3C). Although no considerable effect of TIS108 was observed on seed germination, yet the top concentration (500 µM) considerably impacted germination on the 2nd day (Fig. 3D). It was necessary to achieve considerable inhibitory effect of growth inhibitors on germination, but without complete cessation. Thus, we selected 20 µM ABA, 200 µM PAC, 1000 µM NPA, and 500 µM TIS108 as appropriate concentrations for the next experiment to investigate the role of NAOS in recovery of germination from the stress induced by growth inhibitors.

NAOS can recover seed germination and seedlings growth of garden cosmos from growth inhibitor stress

The role of NAOS in recovery of seed germination from stress induced by growth inhibitors varied according to the type of growth inhibitor. Whereas addition of 1 g/L NAOS to the germination medium improved germination of seeds subjected to ABA (Fig. 4A) and PAC (Fig. 4B) post the 2nd day of germination and those subjected to TIS108 (Fig. 4D) across the 2nd − 3rd day period, it led to non-significant improvement in seeds treated with NPA (Fig. 4C).

Role of NAOS at 1 g/L in germination recovery of garden cosmos seeds from the stress induced by the plant growth inhibitors: (A) 20 µM ABA, (B) 200 µM PAC, (C) 1000 µM NPA and (D) 500 µM TIS108. Data are means ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks above data points indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Two-way ANOVA (Table 3) revealed that NAOS concentration and growth inhibitors and their interaction had significant effects on length, FW and DW of radicle, indicating that NAOS can recover radicle growth of garden cosmos to a greater extent than hypocotyl growth from growth inhibitor stress. Addition of NAOS to the germination medium at a level of 1 g/L significantly improved lengths and FWs of hypocotyl and radicle of seedlings treated with TIS108, with non-significant effect on those treated with ABA, PAC and NPA. While NAOS exerted almost no beneficial effect on hypocotyl DW, it led to marked improvement in radicle DW, particularly in seedlings treated with ABA, PAC and TIS108, with mild beneficial effect on those treated with NPA (Table 4).

Discussion

Seed germination and seedling establishment are two critical phases in plant development that are controlled by multiple endogenous and environmental factors1. Abiotic stress can directly affect seed germination and seedling growth through inducing hormonal disturbances and changing enzyme activity. In recent years, oligosaccharides, a group of compounds with low molecular weights and high water solubility, have been used as growth regulators in agriculture25,27,28,34. In the present study, exogenous NAOS was observed to improve seed germination of garden cosmos, with particularly marked beneficial effect on seedling growth.

Research has shown that oligosaccharides have beneficial regulatory effects on seed germination and seedling growth. Although high levels of chitooligosaccharides (COS) decreased shoot and root length of common bean, suggesting an apparent phytotoxic effect39, yet, COS has been reported to increase germination rate of soybean seeds40. Pectic-oligosaccharides derived from pomelo peel have promoting effects on rice seed germination and early seedling growth41. Mixed oligosaccharides are reported to have the greatest regulatory effects in delay of leaf senescence, enhancement of root development and fruit production of strawberry and cucumber24. In the present study, we found that 1 g/L NAOS significantly increased germination potential of garden cosmos seeds, and the increase was evident at as early as 18 h. But, as the NAOS concentration increased beyond this optimal level, the hypocotyl length was decreased, while root length and hypocotyl FW showed a progressive dose-dependent decrease (Table 1). These results are consistent with the promoting effects of oligosaccharides on seed germination reported in previous studies. For instance, between 0.5 g/L and 1.25 g/L alginate-derived oligosaccharide were effective in promoting maize seed germination and 0.75 g/L was the most effective concentration on maize seedlings growth42. The greater beneficial effect of NAOS on seedling growth of garden cosmos than on seed germination may be attributed to the difference in absorption efficiency of NAOS between seeds and seedlings and the different environmental requirements for seed germination and seedling growth. Nevertheless, the optimal 1 g/L NAOS treatment promoted hypocotyl length but decreased hypocotyl DW, which points to consumption of stored food reserves during seed germination.

The exogenous nitric oxide donor (sodium nitroprusside) has been found to substantially improve tomato seed germination and to upregulate α-amylase and protease activities43. Likewise, exogenous strigolactone can improve tomato germination potential by stimulating α-amylase and protease activities44. The present findings reveal that 1 g/L NAOS significantly increased the activities of α-amylase and β-amylase as well as the contents of soluble starch and total soluble sugars of germinating garden cosmos seeds (Fig. 2). The effect of NAOS was greater on enzyme activity of the germinating seeds than on sugar content, on α-amylase activity than on that of β-amylase and on soluble sugars than on starch. This indicates that NAOS, similar to the other plant growth regulators, can stimulate α-amylase activity during seed germination. However, 0.75 g/L alginate-derived oligosaccharide markedly increased the activity of β-amylase in maize seeds but not the corresponding α-amylase42. This evidence suggests the existence of different mechanisms among different oligosaccharides in their accelerating effect of seed germination.

Treatment with chitosan oligosaccharides can reduce ethylene production and respiration rate during aprium fruit storage45. Application of alginate oligosaccharides as a postharvest treatment has been reported to delay the accumulation of ABA and ABA conjugates and restrain the expression of ABA signaling genes, thus extending the storage life of strawberry46. NAOS treatment affects aging and may be related to the low content of ABA in rose petals33. In our work, NAOS improved content of growth promoters in germinating garden cosmos seeds but reduced the content of the growth retardant (ABA), and among the growth promotors, the improvement in 5DS was the greatest followed by IAA while GAs exhibited the least improvement (Table 2). We found that the four investigated growth inhibitors exerted differential effects on seed germination and seedling growth, where ABA exerted the strongest impact on seed germination but PAC exerted the strongest impact on hypocotyl growth along with the least impact on radicle growth. This suggests that the effect of NAOS on seed germination is related to a complex hormone regulatory pathway.

Numerous phytohormones are known to be involved in the control of seed dormancy and germination, where they can stimulate seed germination individually or through crosstalk1,17,47,48,49. In this study, upon screening of different plant growth inhibitors, ABA and PAC markedly inhibited germination of garden cosmos seeds, while NPA exerted moderate inhibition. TIS108 moderately inhibited germination percentage after 2 days, with no effect on the final germination percentage (Fig. 3). This indicates that germination of garden cosmos seeds responds differently to various hormones. During the NAOS-induced recovery of seed germination from the growth inhibitor stress, the counteracting effect of NAOS was particularly evident against ABA, PAC and TIS108, with marginal effect against NPA (Fig. 4). Future research on seed germination of garden cosmos seeds will through light on the interactions between multiple hormones. In addition, identifying the molecular signaling mechanisms during seed germination would help to characterize the relationships between phytohormones and enzyme activities under NAOS treatments.

In summary, NAOS can play a beneficial role in improvement of seed germination of garden cosmos through coordinated upregulation of amylase activity, particularly α-amylase and the hormonal crosstalk-mediated acceleration of seeds metabolic activities. The results provide a scientific basis for the potential application of NAOS as commercial plant growth regulators. Future studies incorporating advanced transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses will validate the participation of hormonal pathways in seed germination of garden cosmos under NAOS treatments. The long-term effects of NAOS on plant development and yield and the potential applicability to other species are also worthy of further attention.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dong, T., Tong, J., Xiao, L., Cheng, H. & Song, S. Nitrate, abscisic acid and gibberellin interactions on the thermoinhibition of lettuce seed germination. Plant. Growth Regul. 66, 191–202 (2012).

Rajjou, L. et al. The effect of alpha-amanitin on the Arabidopsis seed proteome highlights the distinct roles of stored and neosynthesized mRNAs during germination. Plant. Physiol. 134 (4), 1598–1613 (2004).

Boter, M. et al. An integrative approach to analyze seed germination in Brassica napus. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 1342 (2019).

Moreira, I. N., Martins, L. L. & Mourato, M. P. Effect of Cd, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn on seed germination and seedling growth of two lettuce cultivars (Lactuca sativa L.). Plant. Physiol. Rep. 25, 347–358 (2020).

Yoshioka, T., Endo, T. & Satoh, S. Restoration of seed germination at supraoptimal temperatures by fluridone, an inhibitor of abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 39, 307–312 (1998).

Chae, S. H., Yoneyama, K., Takeuchi, Y. & Joel, D. M. Fluridone and norflurazon, carotenoid-biosynthesis inhibitors, promote seed conditioning and germination of the holoparasite Orobanche minor. Physiol. Plant. 120 (2), 328–337 (2004).

Carrera-Castaño, G., Calleja-Cabrera, J., Pernas, M. & Gómez, L. Oñate-Sánchez, L. An updated overview on the regulation of seed germination. Plants (Basel). 9 (6), 703 (2020).

Bethke, P. C., Gubler, F., Jacobsen, J. V. & Jones, R. L. Dormancy of Arabidopsis seeds and barley grains can be broken by nitric oxide. Planta 219, 847–855 (2004).

Sun, T. P. The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr. Biol. 21 (9), R338–R345 (2011).

Cheng, W. H., Chiang, M. H., Hwang, S. G. & Lin, P. C. Antagonism between abscisic acid and ethylene in Arabidopsis acts in parallel with the reciprocal regulation of their metabolism and signaling pathways. Plant. Mol. Biol. 71 (1–2), 61–80 (2009).

He, Y., Zhao, J. & Wang, Z. Rice seed germination priming by salicylic acid and the emerging role of phytohormones in anaerobic germination. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 66 (8), 1537–1539 (2024).

Linkies, A. & Leubner-Metzger, G. Beyond gibberellins and abscisic acid: how ethylene and jasmonates control seed germination. Plant. Cell. Rep. 31 (2), 253–270 (2012).

Liu, X. et al. Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110(38), 15485–15490 (2013).

Miransari, M. & Smith, D. L. Plant hormones and seed germination. Environ. Exp. Bot. 99, 110–121 (2014).

Steber, C. M. & McCourt, P. A role for brassinosteroids in germination in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 125, 763e769 (2001).

Bunsick, M. et al. SMAX1-dependent seed germination bypasses GA signalling in Arabidopsis and striga. Nat. Plants. 6 (6), 646–652 (2020).

Hu, X. W., Huang, X. H. & Wang, Y. R. Hormonal and temperature regulation of seed dormancy and germination in Leymus chinensis. Plant. Growth Regul. 67, 199–207 (2012).

Mei, S. et al. Auxin contributes to jasmonate-mediated regulation of abscisic acid signaling during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 35 (3), 1110–1133 (2023).

Seo, M. et al. Regulation of hormone metabolism in Arabidopsis seeds: phytochrome regulation of abscisic acid metabolism and abscisic acid regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant. J. 48 (3), 354–366 (2006).

Zhao, X., Dou, L., Gong, Z., Wang, X. & Mao, T. BES1 hinders abscisic acid insensitive5 and promotes seed germination in Arabidopsis. New. Phytol. 221 (2), 908–918 (2019).

Jiang, C. C., Cheng, D. Y., Liu, Z., Sun, J. N. & Mao, X. Z. Advances in agaro-oligosaccharides preparation and bioactivities for revealing the structure-function relationship. Food Res. Int. 145, 110408 (2021).

Catherine, T., Shalini, V. & Kurt, I. The potential of marine oligosaccharides in pharmacy. Bioactive Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 18, 100178 (2019).

Ou, L. et al. Physiological, transcriptomic investigation on the tea plant growth and yield motivation by chitosan oligosaccharides. Horticulturae 8 (1), 68 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Different oligosaccharides induce coordination and promotion of root growth and leaf senescence during strawberry and cucumber growth. Horticulturae 10 (6), 627 (2024).

Jia, X. C., Meng, Q. S., Zeng, H. H., Wang, W. X. & Yin, H. Chitosan oligosaccharide induces resistance to tobacco mosaic virus in Arabidopsis via the salicylic acid-mediated signalling pathway. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–12 (2016).

Tan, C. et al. Integrated physiological and transcriptomic analyses revealed improved cold tolerance in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) by exogenous chitosan oligosaccharide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (7), 6202 (2023).

Qian, X., He, Y., Zhang, L., Li, X. & Tang, W. Physiological and proteome analysis of the effects of chitosan oligosaccharides on salt tolerance of rice seedlings. Int J. Mol. Sci. 25 (11), 5953 (2024).

Zhang, C., Wang, W., Zhao, X., Wang, H. & Yin, H. Preparation of alginate oligosaccharides and their biological activities in plants: A review. Carbohydr. Res. 494, 108056 (2020).

Lopez-Guerrero, A. G., Zenteno-Savın, T., Rivera-Cabrera, F., Izquierdo-Oviedo, H. & Melgar, L. D. A.A.S. Pectin-derived oligosaccharins effects on flower buds opening, pigmentation and antioxidant content of cut lisianthus flowers. Scientia Hortic. 279, 109909 (2021).

Kang, O. L., Ghani, M., Hassan, O. & Rahmati, S. Ramli, N. Novel agaro-oligosaccharide production through enzymatic hydrolysis: physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities. Food Hydrocoll. 42, 304–308 (2014).

Li, J. B. et al. A simple method of preparing diverse neoagaro-oligosaccharides with β-agarase. Carbohydr. Res. 342, 1030–1033 (2007).

Li, N. et al. Recent progress in enzymatic preparation of chitooligosaccharides with a single degree of polymerization and their potential applications in the food sector. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 196, 6802–6816 (2024).

Wan, Y., Wen, C., Gong, L., Zeng, H. & Wang, C. Neoagaro-oligosaccharides improve the postharvest flower quality and vase life of cut rose ‘Gaoyuanhong’. HortScience 58 (4), 404–409 (2023).

Xiong, S. et al. Preserving refrigeration and shelf life quality of hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta) with alginate oligosaccharides preharvest application. J. Food Sci. 89 (11), 7422–7436 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Physiological and transcriptome response to cadmium in cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.) seedlings. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 14691 (2017).

Skutnik, E. et al. Nanosilver as a novel biocide for control of senescence in garden cosmos. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 10274 (2020).

Mavi, K., Demir, I. & Matthews, S. Mean germination time estimates the relative emergence of seed lots of three cucurbit crops under stress conditions. Seed Sci. Technol. 1, 14–25 (2010).

Santana, D. G. & Ranal, M. A. Linear correlation in experimental design models applied to seed germination. Seed Sci. Technol. 1, 233–239 (2006).

Chatelain, P. G., Pintado, M. E. & Vasconcelos, M. W. Evaluation of chitooligosaccharide application on mineral accumulation and plant growth in Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant. Sci. 215–216, 134–140 (2014).

Hai, N. T. T. et al. Preparation of chitooligosaccharide by hydrogen peroxide degradation of Chitosan and its effect on soybean seed germination. J. Polym. Environ. 27, 2098–2104 (2019).

Udchumpisai, W., Uttapap, D., Wandee, Y., Kotatha, D. & Rungsardthong, V. Promoting effect of pectic-oligosaccharides produced from pomelo peel on rice seed germination and early seedling growth. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 42, 2176–2188 (2023).

Hu, X., Jiang, X., Hwang, H., Liu, S. & Guan, H. Promotive effects of alginate-derived oligosaccharide on maize seed germination. J. Appl. Phycol. 16 (1), 73–76 (2004).

Khan, M. N. et al. Effect of nitric oxide on seed germination and seedling development of tomato under chromium toxicity. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 40, 2358–2370 (2021).

Al-Amri, A. A., Alsubaie, Q. D., Alamri, S. A. & Siddiqui, M. H. Strigolactone analog GR24 induces seed germination and improves growth performance of different genotypes of tomato. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 42, 5653–5666 (2023).

Ma, L. et al. Effects of 1-methylcyclopropene in combination with chitosan oligosaccharides on post-harvest quality of aprium fruits. Scientia Hortic. 179, 301–305 (2014).

Bose, S. K., Howlader, P., Jia, X., Wang, W. & Yin, H. Alginate oligosaccharide postharvest treatment preserve fruit quality and increase storage life via abscisic acid signaling in strawberry. Food Chem. 283, 665–674 (2019).

Gupta, S., Plačková, L., Kulkarni, M. G., Doležal, K. & Van Staden, J. Role of smoke stimulatory and inhibitory biomolecules in phytochrome-regulated seed germination of Lactuca sativa. Plant. Physiol. 181 (2), 458–470 (2019).

Omoarelojie, L. O. et al. Synthetic Strigolactone (rac-GR24) alleviates the adverse effects of heat stress on seed germination and photosystem II function in lupine seedlings. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 155, 965–979 (2020).

Sarath, G. et al. Nitric oxide accelerates seed germination in warm-season grasses. Planta 223, 1154–1164 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China for Young Scholars (No. 32102426) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2021QC156).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by XYY, LFG, HTZ and CW. CW designed the experiment. The first draft of the manuscript was written by XYY and CW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Wen, C., Gong, L. et al. Exogenous neoagaro-oligosaccharides accelerate seed germination and alleviate the impact of growth retardants on germination and seedling growth of garden cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus Cav.). Sci Rep 15, 37500 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21473-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21473-w