Abstract

This study compares ticagrelor and clopidogrel on major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and bleeding risk in Chinese CAD patients. Conducted at the Chinese PLA General Hospital from June 2017 to October 2020, it involved patients on DAPT, divided into A + C (aspirin + clopidogrel) and A + T (aspirin + ticagrelor) groups. The primary endpoint was MACE, including all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke. The secondary endpoint was BARC type 2, 3, and 5 bleeding events. Propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) adjusted confounders. Weighted outcomes and Cox models assessed treatment and outcomes. Of 844 patients, 631 were in A + C (470 males, median age 65) and 213 in A + T (178 males, median age 60). Covariates balanced using IPTW or PSM showed no significant baseline differences (P > 0.05, SMD < 0.2). No significant differences in MACE or BARC type 3/5 bleeding were found between groups. However, the A + T group had a higher risk of BARC type 2 bleeding (HR: 4.16, 95% CI: 2.18–7.90). The incidence rates of MACE events were 2.38% (15/631) in the A + C group and 3.29% (7/213) in the A + T group. This study indicates ticagrelor and clopidogrel have similar MACE and BARC type 3/5 bleeding incidence, but ticagrelor shows higher BARC type 2 bleeding risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of global mortality and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost1. Its primary acute manifestation is acute coronary syndrome (ACS), encompassing unstable angina (UA), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)2. Approximately 7 million people are diagnosed with ACS annually worldwide, with notably higher age-standardized mortality rates in low-income regions3,4,5. ACS imposes a substantial healthcare and economic burden, resulting in around 1 million hospitalizations globally each year6. Consequently, early diagnosis and prompt intervention are critical for ACS patients. The cornerstone of ACS treatment lies in rapidly restoring blood flow and implementing long-term management, with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) as the most common surgical approaches. However, long-term management of ACS is more challenging, requiring integrated, multidimensional strategies.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), combining aspirin with another antiplatelet agent, is a guideline-recommended treatment that significantly improves prognosis and reduces mortality in patients with ACS. In patients with low bleeding risk, guidelines endorse extending DAPT duration to ≥ 12 months7,8. However, current research primarily focuses on optimizing DAPT duration9,10,11,12,13, while the choice of aspirin’s companion drug remains controversial. Ticagrelor and clopidogrel demonstrate comparable efficacy in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE)14, complicating treatment decisions. Although clopidogrel’s effectiveness is well-established, growing evidence suggests that ticagrelor, a novel antiplatelet agent, offers stronger antiplatelet effects and greater survival benefits compared to clopidogrel15,16. Clinical studies further indicate that aspirin combined with ticagrelor significantly enhances ACS prognosis and lowers mortality12,17,18. However, in patients at high bleeding risk, ticagrelor is associated with a significantly increased incidence of bleeding complications17. Additionally, Ghamraoui reported that, among patients undergoing carotid artery revascularization, those treated with ticagrelor had a significantly higher incidence of unstable angina or myocardial infarction within 6 months compared to clopidogrel19. In East Asian populations, findings are inconsistent: Kang et al. found that, in Korean AMI patients, ticagrelor and clopidogrel had similar 1-year rates of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), but ticagrelor was associated with higher bleeding risk20. Conversely, the PLATO study reported consistent efficacy between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in Asian patients21. Therefore, further comparative studies on the long-term effects of ticagrelor- or clopidogrel-based DAPT in patients with CAD are essential. Current research primarily focuses on evaluating efficacy within 12 months, with limited data on longer-term outcomes. Therefore, further studies comparing the long-term effects of ticagrelor- versus clopidogrel-based DAPT in patients with CAD are warranted. This study aims to compare clinical outcomes in patients with CAD who receiving long-term ticagrelor- or clopidogrel-based DAPT, evaluating their differential impacts on MACE and bleeding risk.

Methods

Study design and population

This single-center, real-world, retrospective study included patients with CAD who received DAPT at the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Chinese PLA General Hospital between June 2017 and October 2020, with follow-up data collected until January 2022. Follow-up information was obtained from hospital medical records and outpatient clinic visits, supplemented by structured telephone interviews when necessary. Data completeness was high, with only minimal loss to follow-up. All primary and secondary endpoints were confirmed by two independent physicians through review of the medical records, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

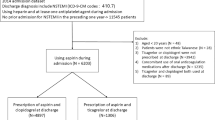

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age > 18 years; (2) diagnosed with CAD per guidelines22 and received DAPT for > 12 months; (3) complete follow-up data available. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who had switched between multiple P2Y12 inhibitors; (2) patients who received anticoagulant therapy; (3) patients with significant bleeding tendencies; (4) patients with malignant tumors or terminal illnesses with a life expectancy of less than 6 months; (5) concomitant heart valve or left ventricular wall abnormalities requiring concurrent surgery, had cerebrovascular diseases (history of stroke or intracranial hemorrhage within six months before DAPT treatment), or had recently participated in other investigational drug trials; and (6) situations that the researchers considered inappropriate for analysis.

Patients were divided into two groups based on medication: those receiving clopidogrel 75 mg once daily combined with aspirin 100 mg once daily (maintenance dose) were assigned to the A + C group; those receiving ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily combined with aspirin 100 mg once daily (maintenance dose) were assigned to the A + T group. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (approval number: S2017-044-02). As a retrospective study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome was defined as the first occurrence of a MACE, a composite endpoint including all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction23, and non-fatal stroke24. The secondary outcome was the occurrence of type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding events during follow-up, assessed using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) scale (ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe bleeding)25,26. Additional endpoints of interest include individual components of primary and secondary outcomes, as well as the incidence of repeat coronary revascularization. Furthermore, the risks of thrombosis and bleeding associated with long-term use of clopidogrel- or ticagrelor-based DAPT were also evaluated.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics include sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol use, past medical history (including Diabetes, Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension, Hepatic insufficiency, Chronic kidney disease, Chronic lung disease, Peripheral arterial disease, Cerebrovascular disease, carotid artery stenosis, Family History of CAD, previous myocardial infarction, chronic heart failure, previous PCI, and previous CABG) and follow-up data were obtained from the database of the anti-thrombotic therapy registration platform for CAD patients. The severity of angina pectoris was evaluated using CCS grading system27. Because no standardized risk scoring system exists specifically for patients receiving long-term dual antiplatelet therapy, we applied the CHA₂DS₂-VASc28 and HAS.BLED29 scores as surrogate tools to estimate thrombotic and bleeding risks. Although originally developed for patients with atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation, these scores were used here for reference purposes only. All patients in this study were treated exclusively with dual antiplatelet therapy and not with oral anticoagulants. These scores should not be interpreted as evidence that our cohort had atrial fibrillation or required anticoagulation therapy.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.3). Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using a 1:1 nearest-neighbor algorithm. Covariates were rigorously selected based on their clinical relevance to the primary outcome, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol consumption history, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, liver dysfunction, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, stenosis, prior myocardial infarction, heart failure, history of PCI or CABG, CHA₂DS₂-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. The Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) model was constructed using the same covariates as PSM. Patients in the ticagrelor group were assigned a weight of 1, while those in the clopidogrel group were assigned a weight of ps/(1-ps), where ps represents the propensity score used for the analysis. Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables meeting normality assumptions were presented as median (interquartile range) and compared using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were expressed as N (%) and compared using the χ² test. Standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated before and after IPTW, with SMD > 0.2 indicating significant baseline differences between groups. The above analyses were repeated in the PSM cohort. Associations and prognoses of the A + T and A + C groups were evaluated using IPTW, PSM, and multivariable Cox models. Cumulative incidence functions (CIF) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to depict the incidence of endpoint events. Cox proportional hazards models were employed to assess the impact of treatment regimens on primary and secondary outcomes during follow-up. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

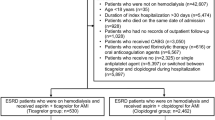

A total of 909 patients were initially enrolled. After excluding 65 patients based on the criteria, 844 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The A + C group included 631 patients [470 males, median age 65.00 (57.50, 72.00) years], and the A + T group included 213 patients [178 males, median age 60.00 (55.00, 68.00) years]. Before IPTW, compared with the A + C group, the A + T group was younger (SMD = 0.304), had a lower rate of prior CABG (SMD = 0.364), but a higher proportion of males (SMD = 0.225) and a higher rate of prior PCI (SMD = 0.518). After IPTW adjustment for covariates, no significant differences were observed between the groups. Following 1:1 PSM, 422 patients (211 pairs) were included, with no significant differences in baseline clinical characteristics (all P > 0.05, SMD < 0.2) (Table 1).

Clinical outcomes

The mean follow-up duration for all patients was 42.2 months. A total of 22 primary outcome events occurred, including 8 all-cause deaths, 6 non-fatal strokes, and 8 non-fatal myocardial infarctions. The incidence rates of MACE events were 2.38% (15/631) in the A + C group and 3.29% (7/213) in the A + T group. Secondary outcome events occurred in 29 patients (4.60%, 29/631) in the A + C group and 29 patients (13.62%, 29/213) in the A + T group, specifically comprising BARC type 2 bleeding [A + C: 21 (3.33%, 21/631); A + T: 24 (11.27%, 24/213)] and BARC type 3 or 5 major bleeding [A + C: 8 (1.27%, 8/631); A + T: 5 (2.35%, 5/213)]. The rates of repeat coronary revascularization were 28 (4.44%, 28/631) in the A + C group and 14 (6.57%, 14/213) in the A + T group.

After IPTW, PSM, and multivariable analysis, no significant differences in MACE incidence were observed between the A + C and A + T groups (all P > 0.05). For secondary outcomes, no significant differences in BARC type 3 or 5 major bleeding were found across the three methods (all P > 0.05). When analyzing BARC type 2 bleeding alone, the A + T group showed significantly increased HRs in IPTW, PSM, and multivariable analyses: 4.16 (95% CI: 2.18–7.90, P < 0.001), 4.24 (95% CI: 1.80–9.95, P < 0.001), and 3.98 (95% CI: 2.11–7.52, P < 0.001), respectively. For BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding combined, the A + T group exhibited significantly elevated HRs across all three methods: 3.59 (95% CI: 2.03–6.36, P < 0.001), 4.17 (95% CI: 1.89–9.19, P < 0.001), and 3.31 (95% CI: 1.89–5.79, P < 0.001), respectively (Table 2).

No significant differences in MACE or repeat revascularization rates were observed between the A + C and A + T groups (Fig. 2b and c). The A + T group exhibited significantly higher cumulative risks of BARC (types 2, 3, or 5) and BARC type 2 bleeding compared to the A + C group (both P < 0.001, Fig. 2a and d). However, no significant difference was found in BARC type 3 or 5 major bleeding rates (Fig. 2e).

Comparison of the cumulative incidence of the clinical events, between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups after inverse probability of treatment weighting. a): Secondary safety end point showing cumulative hazard over time, with A + T group (blue) demonstrating significantly higher risk compared to A + C group, b): Primary end point with no significant difference between treatment groups, c): Any revascularization events showing similar cumulative incidence between groups, d): BARC 2 bleeding events with significantly higher incidence in the A + T group compared to A + C group, e): BARC 3 or 5 bleeding events with no significant difference between groups.

The IPTW Cox model was used to evaluate the risk of outcome events between the two groups. IPTW analysis showed no significant association between the A + C and A + T groups for primary outcome events (HRIPTW = 1.60, 95% CI: 0.51–5.03), repeat revascularization (HRIPTW = 1.43, 95% CI: 0.72–2.84), or BARC type 3 or 5 major bleeding (HRIPTW = 1.90, 95% CI: 0.52–6.96). However, for secondary outcome events, the A + T group exhibited a significantly increased risk of BARC type 2 minor bleeding (HRIPTW = 4.16, 95% CI: 2.18–7.90).

Discussion

Among CAD patients receiving DAPT for more than 12 months, ticagrelor did not significantly reduce the incidence of MACE or the need for repeat revascularization compared to clopidogrel. However, after a mean follow-up of 42 months, results showed that ticagrelor was associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding, particularly BARC type 2 minor bleeding, compared to clopidogrel. These findings highlight the potential bleeding risk of ticagrelor, consistent with prior studies in East Asian populations, and provide real-world evidence for Chinese CAD patients. Notably, while our original IPTW-processed curves may have suggested an atypical pattern, re-analysis of the raw survival data revealed a steady accumulation of events during follow-up. A more pronounced increase in MACE was observed in 2022, primarily driven by a rise in all-cause mortality during the domestic COVID-19 outbreak, likely reflecting non-cardiac deaths. This external factor may explain the apparent late clustering of events.

Current evidence supporting the extension of DAPT beyond 12 months is limited for non-high-bleeding-risk patients undergoing PCI (Class IIb recommendation), CABG patients (Class IIb recommendation), and those on single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) (Class IIb recommendation). Guidelines provide a low level of recommendation for extended DAPT, as it requires balancing the benefits of reducing thrombotic events against the risks of bleeding and other adverse events. For instance, Valgimigli et al.9 compared clinical outcomes in PCI patients receiving 6 versus 24 months of DAPT, finding no significant differences in all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, or stent thrombosis, but a higher bleeding risk in the 24-month group. Yeh et al.10 reported that 30 months of DAPT post-PCI reduced stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction compared to 12 months but increased bleeding risk. In East Asian populations, data on long-term DAPT are scarce compared to Western populations. The EPICOR Asia study13 evaluated long-term benefits of antiplatelet therapy in ACS patients, noting a slightly higher MACE incidence in the DAPT group versus the SAPT group after 2 years, with similar bleeding rates. However, due to treatment allocation bias and baseline confounders in this observational analysis, causal relationships between DAPT and MACE or bleeding could not be inferred. None of these studies directly compared different antiplatelet agents. A retrospective cohort study in Taiwanese acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients30 compared extended DAPT with aspirin plus clopidogrel versus aspirin plus ticagrelor, suggesting that ticagrelor may reduce mortality compared to clopidogrel. In contrast, the PHILO trial31 found higher, but statistically non-significant, rates of primary efficacy outcomes and major bleeding in the ticagrelor group. Park et al.32 reported a higher in-hospital major bleeding rate with ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel. Our study aligns with findings by Park and Goto, indicating that ticagrelor is associated with an increased risk of BARC type 2 or combined BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding. Evidence suggests that the safety and efficacy of DAPT vary across populations, necessitating individualized assessment before extending DAPT. Based on these trials and our findings, we recommend that DAPT duration be determined by weighing ischemic and bleeding risks, with extension considered based on the patient’s ischemic risk profile. As ischemic and bleeding complications may occur concurrently and significantly increase mortality, treatment decisions should be made after evaluating the impact of different bleeding types on mortality relative to ischemic events.

This study provides real-world data on long-term DAPT in Chinese CAD patients and examines the choice of P2Y12 inhibitors in extended DAPT regimens. The results indicate that, among CAD patients in mainland China, ticagrelor did not demonstrate superiority over clopidogrel in primary outcome events.—this finding aligns with other large-scale studies in East Asian populations. For instance, the PHILO trial in Japan33 found no statistically significant differences in primary safety or efficacy outcomes between ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups. Similarly, the KAMIR-NI study in South Korea31 reported that the ticagrelor group did not have a lower MACE incidence than the clopidogrel group within 6 months. A retrospective study by Lee et al.30 in Taiwanese patients with AMI compared outcomes in patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel for at least 30 days. Although the ticagrelor group showed a 22% reduction in the composite outcome (all-cause death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) over 18 months, the study excluded 5,155 patients who died within 30 days post-AMI, a number significantly larger than the 2,844 patients in the ticagrelor group, potentially introducing selection bias. In summary, despite possible clopidogrel resistance in approximately 20% of East Asian populations, our findings suggest that ticagrelor-based DAPT offers no additional clinical benefit over clopidogrel in our study population.

Our findings indicate that ticagrelor significantly increases the risk of BARC type 2 bleeding events in Chinese patients compared to clopidogrel, consistent with the retrospective cohort study by Chi-Jen Chang et al.34 in Taiwanese patients with AMI. Current evidence suggests that ticagrelor does not significantly elevate the risk of BARC type 3 or 5 major bleeding compared to clopidogrel in East Asian and Caucasian populations, indicating a limited impact of long-term ticagrelor use on major bleeding risk. However, prior studies35 have shown that, over a 4-year follow-up, bleeding events contribute to mortality risk comparably to myocardial infarction. The TRACERA trial25,36 further demonstrated that even BARC type 2 minor bleeding adversely affects the prognosis of patients with ACS. Based on our results, the impact of ticagrelor therapy warrants cautious evaluation.

Another highlight of this study was the long follow-up duration, the mean follow-up duration for all patients was 42.2 months, which was significantly longer than most previous studies, Ye et al. focused on the platelet aggregation function after 5-day treatment of clopidogrel or ticagrelor in a group of CAD patients37; while Onuk compared the performance of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in anemic ACS patients and showed ticagrelor demonstrated superiority in reducing ischemic events38, another study performed in India showed similar follow-up duration of 40 months, however, they focused on patients who switched drugs and revealed that Intermediate metabolizer exhibited a trend favoring ticagrelor continuation39.This study had several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, despite the use of IPTW to partially address randomization limitations, selection bias may still persist. Second, being a single-center study with a limited sample size and incomplete coverage of all coronary artery disease patients, the generalizability of the findings is constrained, potentially introducing patient selection bias. Third, the study population included patients receiving medical therapy and PCI/CABG, resulting in considerable within-group heterogeneity. Future multicenter, prospective, large-scale clinical studies are needed to further evaluate the clinical benefits and bleeding risks of ticagrelor-based DAPT regimens. Additionally, the patient enrollment period spanned approximately five years, during which changes in clinical practice and treatment strategies may have influenced outcomes. The small number of MACE events further limits the statistical power of our analyses, raising concerns about external validity. These factors should be considered when interpreting our findings. If any true difference in efficacy or safety between ticagrelor and clopidogrel exists, it is likely small, and confirmation would require studies with larger populations. Moreover, the multivariable Cox models may have been overfitted, as the number of covariates exceeded the recommended ratio of events per variable, and the adjusted hazard ratios should therefore be interpreted with caution.

This study demonstrates that among Chinese patients with CAD receiving long term DAPT, ticagrelor shows no significant difference compared to clopidogrel in terms of MACE or BARC type 3 and 5 bleeding events. However, ticagrelor is associated with a significantly higher incidence of BARC type 2 bleeding events, suggesting an increased bleeding risk when combined with aspirin in Chinese patients with CAD.

Conclusion

The long-term follow-up performance showed that ticagrelor did not significantly reduce the incidence of MACE or the need for repeat revascularization compared to clopidogrel, but was associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding. Indicating the potential bleeding risk of ticagrelor and special attention should be paid to high-risk bleeding patients in a clinical scenario.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ralapanawa, U. & Sivakanesan, R. Epidemiology and the magnitude of coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome: A narrative review. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 11, 169–177 (2021).

Nohria, R. & Viera, A. J. Acute coronary syndrome: diagnosis and initial management. Am. Fam Physician. 109, 34–42 (2024).

Cader, F. A., Banerjee, S. & Gulati, M. Sex differences in acute coronary syndromes: A global perspective. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 9, 239 (2022).

Timmis, A. et al. Global epidemiology of acute coronary syndromes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 778–788 (2023).

Bhatt, D. L., Lopes, R. D. & Harrington, R. A. Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes. Rev. JAMA. 327, 662–675 (2022).

Makki, N., Brennan, T. M. & Girotra, S. Acute coronary syndrome. J. Intensive Care Med. 30, 186–200 (2015).

Ibanez, B. et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 39, 119–177 (2018).

Byrne, R. A. et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 44, 3720–3826 (2023).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation 125, 2015–2026 (2012).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Benefits and risks of extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI in patients with and without acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 2211–2221 (2015).

Kinlay, S., Young, M. M., Sherrod, R. & Gagnon, D. R. Long-Term outcomes and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary intervention with Second-Generation Drug-Eluting stents: the veterans affairs extended DAPT study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e027055 (2023).

Bonaca, M. P. et al. Prevention of stroke with Ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction: insights from PEGASUS-TIMI 54 (Prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with prior heart attack using Ticagrelor compared to placebo on a background of Aspirin-Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 54). Circulation. 134, 861–871 (2016).

Pocock, S. et al. Predictors of one-year mortality at hospital discharge after acute coronary syndromes: A new risk score from the EPICOR (long-tErm follow uP of antithrombotic management patterns in acute coronary syndrome patients) study. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care. 4, 509–517 (2015).

Turgeon, R. D. et al. Association of Ticagrelor vs clopidogrel with major adverse coronary events in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 180, 420–428 (2020).

Verdoia, M. et al. Mean platelet volume and high-residual platelet reactivity in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or Ticagrelor. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 16, 1739–1747 (2015).

Kohli, P. et al. Reduction in first and recurrent cardiovascular events with Ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in the PLATO study. Circulation 127, 673–680 (2013).

Saito, S. et al. Efficacy and safety of adjusted-dose Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patients with acute coronary syndrome: the PRASFIT-ACS study. Circ. J. 78, 1684–1692 (2014).

Bansilal, S. et al. Ticagrelor for secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with multivessel coronary disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 489–496 (2018).

Ghamraoui, A. K., Chang, H., Maldonado, T. S. & Ricotta, J. J. 2 Clopidogrel versus Ticagrelor for antiplatelet therapy in transcarotid artery revascularization in the society for vascular surgery vascular quality initiative. J. Vasc Surg. 75, 1652–1660 (2022).

Kang, J. et al. Third-Generation P2Y12 inhibitors in East Asian acute myocardial infarction patients: A nationwide prospective multicentre study. Thromb. Haemost. 118, 591–600 (2018).

Kang, H. J. et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: A retrospective analysis from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) Trial. Am Heart J. 169, 899–905 e891 (2015).

Levine, G. N. et al. An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery, 2012 /PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation. 134, e123-155 (2016). (2016).

Thygesen, K. et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 1581–1598 (2012).

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2020 update: A report from the American. Heart Association Circulation. 141, e139–e596 (2020).

Vranckx, P. et al. Validation of BARC bleeding criteria in patients with acute coronary syndromes: the TRACER trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2135–2144 (2016).

Mehran, R. et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding. Acad. Res. Consortium Circulation. 123, 2736–2747 (2011).

Owlia, M. et al. Angina Severity, Mortality, and healthcare utilization among veterans with stable angina. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012811 (2019).

Cairns, J. A. ACP journal club. CHA2DS2-VASc had better discrimination than CHADS2 for predicting risk for thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation. Ann. Intern. Med. 154, JC5–13 (2011).

King, A. Atrial fibrillation: HAS-BLED–a new risk score to predict bleeding in patients with AF. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8, 64 (2011).

Lee, C. H. et al. Cardiovascular and bleeding risks in acute myocardial infarction newly treated with Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in Taiwan. Circ. J. 82, 747–756 (2018).

Goto, S., Huang, C. H., Park, S. J., Emanuelsson, H. & Kimura, T. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese patients with acute coronary syndrome -- randomized, double-blind, phase III PHILO study. Circ. J. 79, 2452–2460 (2015).

Park, K. H. et al. Comparison of short-term clinical outcomes between Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing successful revascularization; from Korea acute myocardial infarction Registry-National Institute of health. Int. J. Cardiol. 215, 193–200 (2016).

Mauri, L. et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl. J. Med. 371, 2155–2166 (2014).

Chang, C. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in East Asian patients with acute myocardial infarction: A nationwide cohort study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 443–451 (2021).

Kazi, D. S. et al. Association of spontaneous bleeding and myocardial infarction with long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1411–1420 (2015).

Kikkert, W. J. et al. The prognostic value of bleeding academic research consortium (BARC)-defined bleeding complications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison with the TIMI (Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction), GUSTO (Global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary Arteries), and ISTH (International society on thrombosis and Haemostasis) bleeding classifications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1866–1875 (2014).

Ye, Z. et al. Impact of Hemodialysis on efficacies of the antiplatelet agents in coronary artery disease patients complicated with end-stage renal disease. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 57, 558–565 (2024).

Onuk, T. et al. Comparison of Ticagrelor and clopidogrel in anemic patients with acute coronary syndrome: efficacy and safety outcomes over one year. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 80, 759–770 (2024).

Senguttuvan, N. B. et al. Impact of switching antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndrome patients with different CYP2C19 phenotypes: insights from a single-center study. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 35, 145–152 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1301400).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dong Shiyong and Zhang Liyue are responsible for analyzing data, statistical plotting, and writing papers. Zhang Liyue and Xie Yuqian are responsible for data collection and clinical follow-up. Xie Yuqian also provides statistical analysis guidance, and Wang Rong is responsible for research design, organizational guidance, paper revisions, and providing full funding support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (approval number: S2017-044-02). The requirement for individual Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital because of the retrospective nature of the study. The study was carried out in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, S., Zhang, L., Xie, Y. et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Chinese patients with coronary artery disease: a retrospective real-world study. Sci Rep 15, 37614 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21478-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21478-5