Abstract

“Little Giant” Enterprises (LGEs) are leading exemplars of China’s specialized and sophisticated small and medium-sized enterprises, playing a critical role in national industrial upgrading and innovation. Understanding the specific business environment configurations that foster these high-potential firms is a significant and practical research question. This study investigates the spatial distribution of LGEs and the characteristics of the regional business environment in Zhejiang Province, which hosts the largest number of LGEs in China. Based on adaptation theory, we employ a multi-method approach, integrating Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). Our analysis of 90 districts and counties reveals that the spatial distribution of LGEs is unbalanced and can be categorized into three distinct groups. The QCA results show that no single business environment element is a necessary condition for high LGE density; instead, we identify nine distinct configuration paths that lead to this outcome across the different groups. A key finding is that good financial services and a robust market environment are common core conditions across most paths. Furthermore, DEA results indicate that the traditional approach of optimizing individual elements is inefficient, underscoring the necessity of strategic, synergistic combinations. This research provides a novel configurational perspective on regional development policy, offering valuable theoretical insights and practical guidance for municipal authorities seeking to cultivate specialized and sophisticated enterprises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Like many emerging nations, China’s economy is primarily driven by small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs), which significantly impact manufacturing innovation and enhancement. Recently, constraints in crucial technologies and the emergence of “economic chokepoints” have become significant obstacles to China’s sustainable economic development. Nurturing a group of firms possessing core technology, like Germany’s hidden champions, is quite essential. Hidden champions are companies that are market leaders but unknown to the public1. Recently, China has proposed a strategy to guide the development of SMEs towards the path of specialization and sophistication. Specialized and sophisticated “little giant” enterprises (LGEs) in China are SMEs that focus on specialization (focusing on special markets), sophistication (lean production and management) and innovation (novelty of product or service)2,3. This concept was first presented in the Chinese government report in 2011 and has attracted considerable attention. Since 2019, the MIIT (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology) has annually selected a group of LGEs nationally.

In recent research, LGEs are regarded as the development goals of SMEs in China, and scholars focus on exploring the paths to cultivate more LGEs from a theoretical perspective4. Prior studies emphasize the critical role of the business environment (BE) in fostering these firms, particularly in developing economies2,5. The business environment in which firms operate is crucial for their development and growth. It encompasses both internal and external factors that impact how well firms function, such as regulations, economic conditions, infrastructure, and innovation capacity6,7. Previous research confirms that an optimized business environment enhances SMEs’ technological innovation by stimulating their innovative capacity8. Similarly, Aldrich and Ruef9 demonstrate that dynamic market environments enable SMEs not only to compete within existing markets but also to explore new growth opportunities. Further studies highlight that efficient governance increases SMEs’ access to social resources and improves welfare, thereby supporting LGE development. Conversely, adversarial government-business relations and bureaucratic inefficiencies constrain firms’ resource acquisition and growth prospects10. Moreover, an optimized legal environment can effectively mitigate the inherent fragility and uncertainty of SMEs while enhancing their adaptability11. Despite these insights, previous studies primarily focus on the isolated effects of individual business environment elements such as governance, innovation, or legal frameworks on SME growth12, neglecting the interactive mechanisms within the business environment system under China’s transitional institutional context13. This gap in research limits our comprehension of how synergistic effects among business environment factors affect SME growth patterns. China’s transitional economy presents unique institutional configurations where diverse environmental factors combine to create distinct, often challenging business ecosystems14. The cultivation of LGEs exhibits intricate linkages with various business environment factors. Their expansion requires tailored environmental ecosystems, while their sustainability demands operational flexibility in dynamic conditions. Different combinations of business environment elements exert distinct effects on LGEs, making it practically significant to analyze the synergistic effects of multiple business environment factors15.

According to the announcement of the MITT on the national-level LGEs, Zhejiang has the largest number of LGEs among the 31 provinces, securing the top position. What might be the factors behind this remarkable performance? Is there a strong causal relationship with the business environment in the region? The business environment represents a complex system encompassing multiple dimensions; however, existing research lacks systematic frameworks to examine its relationship with the growth of LGEs. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) offers distinct advantages over traditional statistical methods in this context, as it can effectively analyze the combinatorial effects of multiple factors through set theory and Boolean algebra16,17. While a few recent studies have begun exploring this relationship from a configurational perspective18,19, limitations remain in both theoretical and methodological dimensions. Current research has not yet clearly identified which specific combinations of business environment factors lead to high LGE density, nor does it employ sufficiently rigorous methods to propose actionable policy pathways. This study addresses these gaps by investigating the spatial distribution patterns of LGEs and their corresponding business environment characteristics at the county and district levels in Zhejiang Province. Through the QCA method, we examine the multiple BE factors and their combinatorial mechanisms in fostering LGEs, to identify business environment configurations for high LGE concentration. DEA is further conducted to evaluate business environment optimization efficiency, generating evidence-based policy recommendations for local governments to enhance the regional business environment.

This paper aims to make marginal contributions in three aspects. First, it constructs an integrated analytical framework to identify the business environment conditions for fostering LGEs. Second, employing the OCA method, the study examines configuration paths of business environment factors that lead to high LGE density using county-level data from Zhejiang Province. Furthermore, DEA is utilized to propose targeted business environment improvement strategies, enabling local governments to optimize regional business environments more effectively. These findings offer both theoretical and practical insights for cultivating LGEs. The paper proceeds with a literature review in Sect. 2, followed by research methodology in Sect. 3, empirical findings in Sect. 4, discussion in Sect. 5 and conclusions in Sect. 6.

Literature review

The concept and development of “Little Giant” enterprises (LGEs)

China’s “Little Giant” Enterprises (LGEs) are a central pillar of the national strategy to foster specialized, refined, and innovative SMEs. Officially designated by the MIIT, LGEs are SMEs that target niche markets, possess leading technologies, and demonstrate strong innovative capacity within their specialized fields20.

The development of LGEs is driven by distinct institutional and policy drivers. Unlike some Western models that evolve organically, the LGE initiative is a state-led industrial policy designed to overcome specific developmental challenges within China’s manufacturing sector. These challenges include a historical reliance on volume-based manufacturing, vulnerabilities in key core technologies (“bottleneck” problems), and the need for greater resilience and upgrading in global supply chains21.

LGEs are characterized by several key features: (1) a dominant focus on a specific market niche or a key segment in the manufacturing supply chain; (2) a strong commitment to research and development (R&D) and intellectual property creation; (3) high-quality, lean production standards; and (4) the potential to become industry leaders domestically and internationally. Their role is critical in advancing China’s industrial modernization, enhancing technological self-reliance, and moving up global value chains22. While the concept of highly specialized SMEs exists internationally (e.g., Germany’s “hidden champions”23, LGEs represent a parallel phenomenon with a unique policy-backed genesis. The existing literature on hidden champions, which highlights their market leadership, innovation focus, and geographical clustering23,24,25,26, can provide a valuable international framework for analysis and comparison. However, the primary context for understanding LGEs remains the specific Chinese policy environment and the developmental objectives they are designed to address.

Business environment

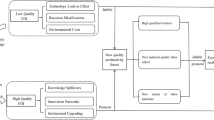

The business environment (BE) was originally proposed by the World Bank as the time, cost, and convenience factors that a company needs to spend in the business process. Carlin et al.27 define the business environment as an economic context that influences the operational costs, convenience, and stability of enterprises, encompassing infrastructure, macroeconomic policies, and other social factors. Similarly, Gaganis et al.28 define it as the regulatory framework governing business establishment, operation, and dissolution. Aterido et al.29 further conceptualize the business environment as a set of conditions within a firm’s control that significantly impact its behavior throughout its lifecycle. In China, this term has a relatively short history. Some scholars defined BE as a combination of hard and soft factors such as infrastructure, policies, and labor cost13,30. Based on an ecological perspective, Li’s research group13,30 conceptualized BE as a holistic ecosystem that includes elements for business functioning. The research compares the business environment to a “habitat” for enterprises. Habitat is a biological concept that refers to the living environment of animals, and the business environment is similar to that of companies. Du et al.31 also compared BE as an ecosystem and discovered that though cities differ in the development level of markets, finance, and other aspects of BE, these disparities do not automatically prevent them from reaching high levels of entrepreneurial involvement.

A good business environment is an important breeding ground for the growth of enterprises31,32,33,34. Recently, a growing number of scholars in developing countries have focused on how BE influences local innovation and SME growth. In highly competitive markets, SMEs depend on consistent and comprehensive resource support to sustain long-term growth and drive innovation35. An enabling business environment plays a pivotal role in facilitating SMEs’ access to these essential resources36. Furthermore, disparities in business environments significantly affect SMEs’ ability to acquire critical resources, develop capabilities, and exploit viable opportunities, ultimately determining their growth pathways12. Nam and Tram37 showed that enhancing the business environment can be advantageous for the high-quality progression of SMEs. Focusing on small firms, Haschka et al.38 discovered that a conducive BE typically enhances firm growth. However, specific elements like minimal entry costs, availability of land, and financing service have a more significant impact on SME growth. Enhancing and optimizing the business environment can increase business confidence, improve efficiency39,40, quality, and innovation resilience12,41. This not only benefits local firms but also contributes to the overall quality development of the region42,43.

Business environment and LGEs cultivation

In the context of global industrial upgrading and intensifying technological competition, governments worldwide are cultivating specialized SMEs with core competitiveness by optimizing business environments. Germany’s “Hidden Champions” thrive on industrial clusters and financial support systems, such as low-interest loans from banks and high-standard certifications by industry associations24. The U.S. “Small Giants” benefit from market-driven financing and preferential procurement policies44, while Japan’s niche manufacturers rely on cross-shareholding networks and long-term stability strategies, including 10-year tax incentives for key industries45. Korea’s INNO-BIZ program provides technology-intensive SMEs with substantial policy support, including tax reductions (with R&D tax credits up to 50%), innovation subsidies, and preferential government procurement opportunities. These measures effectively lower entry barriers and foster specialized SME development46,47. The previous studies show that BE play a crucial role in the development of specialized SMEs. These international experiences offer valuable insights for the cultivation of LGEs in China.

China’s specialized and sophisticated LGEs are growing rapidly with policy support, and the cultivation of LGEs relies fundamentally on supportive business environments48,49. Some research starts to explore the factors influencing the development of LGEs and finds that it is impacted by various environmental elements, including public service, economic and social strength, as well as innovation capacity in different regions49,50. Fostering a conducive business environment is an important measure for reducing regional disparities and the growth of LGEs. However, the literature on LGEs in China with limited research exploring the correlation between BE and the output of LGEs. Besides, recent studies have not analyzed the characteristics of the regional business environment where LGEs are located.

The cultivation of LGEs relies on business environment conditions. Different combinations of BE elements exert distinct effects on LGEs, making it practically significant to analyze the synergistic effects of multiple BE factors15. Specifically, a fair, competitive market environment drives SMEs to continuously enhance their innovation capabilities and competitiveness, serving as a key catalyst for cultivating LGEs. It also provides these firms with greater opportunities to expand market share, optimize products and services, and strengthen core competencies. As essential components of a favorable business environment, financial services and government support play crucial roles. Through accessible bank loans, government subsidies, tax incentives, and other measures, they achieve a dialectical unity between an “effective government” and an “efficient market,” thereby facilitating the cultivation and growth of LGEs51,52. Furthermore, innovation capacity also serves as a vital role in fostering LGEs. Under such conditions, SMEs can effectively integrate innovation resources, significantly increase R&D investment, enhance collaborative innovation and strengthen technology spillovers53.

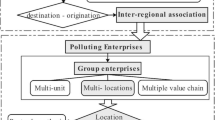

The cultivation of LGEs constitutes a complex systematic project, jointly influenced by multiple business environment factors including market environment, financial services, government services, innovation capacity and so on. However, current literature remains incomplete in addressing the following critical questions: (1) whether any single business environment factor serves as a necessary condition for LGE cultivation, (2) what specific combinations of these factors optimally promote such development. QCA proves particularly suitable for investigating these questions, as it can deconstruct the synergistic effects of multiple concurrent factors while revealing asymmetric relationships and equifinal causal pathways between various conditions and outcomes16. Our study tries to examine the relationship between the regional BE and the spatial density of LGEs from a configurational perspective. Using LGE distribution density as the outcome variable and following the views of Li’s research group13 and Du et al.31, we operationalize the business environment as an ecosystem for enterprises. Building upon prior research and considering the distinctive characteristics of Zhejiang Province, we develop a municipal-level BE evaluation index system comprising seven dimensions. This approach enables a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of county-level BE quality by accounting for the diverse environmental factors affecting enterprise production and operations. The theoretical framework of this study is structured in Fig. 1.

Study area and methodology

Study area

The paper examines the spatial pattern of LGEs and the business environment that fosters the output of LGEs at the level of counties and districts in Zhejiang Province. The paper focuses on Zhejiang Province mainly for the following reasons: first, Zhejiang is a large province for private enterprises and SMEs, and now it has become a large province for national-level LGEs. In the first three batches, Zhejiang has 470 national-level LGEs, surpassing Guangdong, Shandong, and Jiangsu, attracting widespread attention from all sectors of society. Second, Zhejiang’s county-level economy is developed, with 17 counties included in this year’s ranking of China’s top 100 counties by economy. Taking the counties and districts within Zhejiang Province as the research scale can help us to further analyze the business environment characteristics of the LGE location.

Data source

The list of LGEs is derived from the announcement by the MIIT in China. Since 2019, it has started to select LGEs based on the following indicators, like high revenue efficiency, high growth rate, strong innovation capability, and so on. By checking and matching with the list of LGEs, 470 LGEs are finally obtained in Zhejiang Province. Then, using the “Qichacha” system platform, we obtain the basic information and address of each company, and further use Geocode software to get the longitude and latitude coordinate information to locate the geographical location of the LGEs to their county and district affiliation. As of 2024, Zhejiang has 37 municipal districts, 20 county-level cities, 32 counties, and one autonomous county, with a total of 90 counties and districts. Using this as the spatial statistical unit, we calculate the number and spatial distribution density of LGEs in 90 counties and districts. The data of the variables in this article mainly come from the Zhejiang County and City Statistical Database and Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook in the EPS global statistical data/analysis platform, as well as manual search and organization on websites. For the existing data, missing and abnormal values should be handled by the following steps: first, manually organize relevant statistical data and verify them. Second, if it cannot be verified, outliers should be treated as missing values and processed by using methods such as mean interpolation, smoothing, regression interpolation, etc.

Variables and data processing

In this study, we aim to analyses the correlation between the output of LGEs and the business environment. We use the distribution density (Y) of LGEs to measure their output, calculated as the number of LGEs per square kilometer in each region of Zhejiang Province. This metric highlights the spatial concentration and agglomeration effects of these enterprises. As for business environment (BE), we adopt the views of Li’s research group and conceptualize BE as an ecosystem for enterprises. To measure business environment characteristics of the regional space where LGEs are located, we mainly refer to the index system introduced by Li’s framework in his research on “Evaluations on China’s Urban Business Environment“54. We expand Li’s business environment index system by adding two key dimensions: rule of law environment and innovation capacity, to better suit Zhejiang’s context. As a national pilot for rule of law development, Zhejiang has implemented quantitative legal assessments and streamlined administration through its one-stop service reform55. The province also boasts strong innovation capabilities, exemplified by Hangzhou’s digital economy and Ningbo’s advanced manufacturing. These additions allow for more accurate evaluation of county-level business environments across Zhejiang. For the measurement of BE index X, we develop a set of indicators including 7 first-grade indicators, 17 s-grade indicators, and 21 base measurement indices (Table 1). The values in parentheses represent weights that follow Li’s index system and are evaluated by Chinese experts. The base measurement indices are first standardized using the normalization method, followed by the calculation of the business environment index (X) for each district and county in Zhejiang Province using the multi-factor weighted summation technique (see Table 2). The weighted summation is performed hierarchically: normalized base indicators are first weighted at each level and then combined to construct the final business environment index.

The index system comprises seven level-one indicators, as presented in Table 1. These indicators are selected based on Li’s framework and tailored to Zhejiang’s regional characteristics. The values in parentheses represent weights that follow Li’s index system and are evaluated by Chinese experts. The weight values in parentheses were initially adopted from Li’s established index system and subsequently evaluated and confirmed by a panel of domain experts to ensure their validity for the provincial context. The base measurement indices are first standardized using the normalization method, followed by the calculation of the business environment index (X) for each district and county in Zhejiang Province using the multi-factor weighted summation technique. First, public services are the basic requirements for a business environment, such as the road infrastructure, water and electricity supply, etc. Second, human capital is the main resource to enhance the firm’s innovation capability. We use human resource reserves and labor costs to measure the human resources of the region. Third, the market environment is an important foundation for a business ecosystem, involving economic indicators, trading volume and enterprise organization. Moreover, financial services, innovation capacity and rule of law environment also play an important role in a good business ecosystem, which affect the growth of LGEs. These enterprises depend on financial support to scale R&D and production, innovation to differentiate in niche markets, and a stable legal environment to ensure contract enforcement, intellectual property protection and fair competition. Furthermore, an efficient and clean government environment is a key component of a good business environment ecosystem. To provide a favorable government environment for the cultivation of LGEs in the region, thereby helping them achieve gradient growth.

Research method

The paper focuses on exploring the spatial pattern of LGEs in Zhejiang Province, and evaluates which types of business environments are more conducive to LGE output. First, this study uses ArcGIS to analyze the spatial distribution of LGEs in the region. Second, it uses the fsQCA method to identify the business environments that lead to high spatial density of LGEs. Finally, DEA is further conducted to evaluate business environment optimization efficiency for different counties and districts.

Cluster analysis

Cluster Analysis is one kind of unsupervised machine learning methods, which is commonly used to solve the classification problem of different samples, whose idea is based on the statistical principles of maximum inter-class variance and minimum intra-class variance. Ward’s hierarchical clustering method is widely used in academic research and industry. The clustering method is usually applied to the feature recognition or classification with a large number of samples56,57. Based on the multi-index information features of the research samples, classification work is carried out to distinguish the homogeneity and heterogeneity of regions, and to represent the differences of the research objects. This method is based on the analysis of variance, and the selected metric is Euclidean distance. Firstly, the samples are classified into a set, then the distance variance between classes is calculated. Any two categories with small variation and deviation square are merged into one class. The sample distance is calculated circularly and classified in order until all categories are merged. The analysis results are presented in the form of pedigree chart or tree chart.

Assuming a set containing n samples is divided into k groups(G1, G2,…, Gk), and xij is used to represent the feature vector of the i-th sample indicator in Gj, where nj is the number of samples corresponding to Gj, and xj is the gravity center of Gj,, then the sum of squares of deviations for all samples in Gj is58:

The formula for the sum of squares of internal deviations within all categories is denoted as.

Equation (2).

In this study, we use the Ward’s hierarchical clustering method to conduct the cluster analysis since it is widely used. For the approach, there are 90 counties and districts, so the sample size is 90 cases. We base on the data of first-grade business environment indices (X1-X7) and the spatial distribution density of LGEs (Y) for the group classification of 90 cases.

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA)

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), a set-theoretic configurational method grounded in Boolean algebra, examines necessity relations and subset relationships between causes and effects, offering a holistic approach to analyzing the drivers of complex social issues. As a research paradigm that transcends traditional qualitative and quantitative limitations, QCA has been widely applied in management studies59,60. It combines the strengths of qualitative analysis (case-oriented and in-depth) while avoiding the constraints of quantitative methods (large-sample orientation and low granularity). Unlike conventional regression analysis, which focuses on the net effects of independent variables, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) evaluates complex causal relationships by identifying how antecedent conditions combine to jointly influence outcomes. Therefore, this study adopts fsQCA to investigate how seven key factors in the business environment interact to affect the density of specialized and innovative “Little Giant” enterprises in Zhejiang Province, revealing the multifaceted driving mechanisms behind their distribution. QCA evaluates the sufficiency and necessity of condition X for outcome Y using consistency and coverage measures.

Data envelopment analysis

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is a technique applied to evaluate the efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs). This method was first proposed by researchers Charnes et al. in 197861. This method does not require pre-setting the form of the production function, but evaluates efficiency by constructing a production possibility boundary formed by actual data.

This method uses various input and output data from DMUs to construct a data envelopment surface that identifies optimal combinations, defining the production frontier. DMUs located on this frontier are classified as efficient and receive an efficiency score of 1. In contrast, DMUs outside the frontier are classified as inefficient and receive a relative efficiency score between 0 and 162,63.

In this study, inputs are 7 first-grade indices (X1-X7), and outputs are the distribution density of LGEs (Y) in 90 districts and counties in Zhejiang Province. We use the DMUs efficiency analysis method of the DEA model to identify whether there is “input redundancy” or “output loss” in the improvement of the business environment (input) and the growth (output) of LGEs in each county or district64. Meanwhile, it can also further improve the business environment and optimization plans, which are helpful for the growth of LGEs. Let Xij (i = 1, ., m) and Yrj (r = 1, ., t) denote the i-th input and r-th output of the j-th region. Weights Wr and Vi are assigned to the i-th input and r-th output. The efficiency value of DMUmn is represented by Gj, and the production frontier indicates the most efficient input-output relationship. If the total of the weighted inputs equals 1, and the model of the 0-th DMU can be defined as62,65:

By converting Eq. (3) into its dual form and incorporating slack variables Si− (input redundancy) and Sr+ (insufficient output), Eq. (4) is derived. Here, λ represents the eigenvalue and θ0 is the efficiency coefficient. Then analytical results (θ0, λ, S−, S+) can be obtained by substituting the input and output data into Eq. (4).

In Eq. (5), the parameters θ0 = 1, S+ = 0 indicate that the DMUj in the region is efficient, signifying optimal use of all factors and achieving the desired output results. Conversely, θ0 < 1 suggests inefficiency of the DMUj in the region. If Si− > 0, it means that the input factor Xij is not fully utilized, while Sr+ > 0 implies a shortfall of Sr+ in the output Yrj. This method allows for the identification of input redundancy and output shortfall in each region, providing a basis for enhancing resource allocation and making the necessary changes to achieve the desired output62,65:

Results

Spatial layout of LGEs

The paper visualizes the spatial layout of LGEs in Zhejiang Province. Based on the detailed geographical location and latitude-longitude coordinate information of 470 LGEs in Zhejiang Province, a geographical spatial distribution map is created using the ArcGIS10.8 software tool (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2, LGEs have emerged in various regions and counties, but the spatial distribution density varies across regions and counties.

The spatial layout features of LGEs show the divergence of large-scale space and the agglomeration of local space. 81 out of 90 county-level administrative regions have specialized and sophisticated LGEs. In other words, 90% of the county-level administrative regions in the province are distributed with LGEs.

In terms of a wide area, the vast majority of 90 county-level units in Zhejiang Province have LGEs distributed in varying degrees. The top 10 counties and districts with the highest number of enterprises are: Yinzhou District (32), Cixi (31), Zhenhai District (25), Beilun District (25), Yuyao (18), Yuhang District (18), Fenghua District (14), Haishu District (11), Jiangbei District (11), Wucheng District (10) and Yueqing (10). There is less distribution of LGEs located in the mountainous areas in the southwest of Zhejiang Province such as Qingtian County, Longquan, Yunhe County, Songyang County and other areas. However, some counties and districts have not got LGEs yet such as Tonglu and Chun’an Counties in Hangzhou, Taishun and Dongtou Counties in Wenzhou. LGEs are mainly distributed in the Hangjiahu and Ningshao plains in the northeast, with Ningbo and Hangzhou ranking the top in terms of the number of LGEs. For instance, Ningbo has a total number of 182 LGEs in various districts, ranking third in China in the quantity of LGEs after Beijing and Shanghai. The counties and districts in Ningbo on the southern shore of Hangzhou Bay have a high concentration of LGEs, becoming the hotspots favored by LGEs in Zhejiang Province. The southwestern mountainous areas, on the other hand, are the inert spaces of LGEs.

Geographical distribution of LGEs in Zhejiang Province. Source: National Geomatics Center of China. Map created using ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Correlation between the BE and the layout of LGEs

The cultivation and development of LGEs are like living organisms, requiring time, nutrition, and a good ecological environment. BE includes various factors that businesses encounter during economic activities31. Therefore, a good business environment is an important “breeding ground” and “habitat” for high-quality development of enterprises32,33,34.

First, this article conducts a correlation analysis between the business environment index (X), the 7 first-grade indices (X1-X7), and the distribution density of LGEs (Y) in 90 districts and counties in Zhejiang Province. We use Pearson correlation analysis and present the results in Table 3. Pearson correlation analysis is employed to preliminarily examine the bivariate relationships relationship between business environment factors and LGE distribution density, supplemented by QCA to reveal the multidimensional combinations of BE factors that contribute to high LGE density. The combined application of these analytical methods offers superior insights into business environment-LGE distribution dynamics compared to conventional approaches.

Table 3 shows that the correlation between the distribution density (Y) of LGEs in Zhejiang Province and the business environment (X) reach the significant correlation level of 0.4670, respectively. Among the first-grade business environment indices, the correlation between Y and financial services (X5) reach the highly significant levels of 0.6644. The correlation with human resources is also significant at level of 0.5374. The correlation with market environment reaches highly significant levels of 0.4303. In addition, the correlation with the innovation environment is also significant at level of 0.2398. However, the correlation with the rule of law environment is only 0.1989, which may because the overall legal environment within the region of Zhejiang Province has a high level and there are relatively minimal spatial differences between different counties and districts.

Then, Ward’s hierarchical clustering method is used to further explore the business environment characteristics of LGEs and their differential performance. Based on the first-grade business environment indices and the spatial distribution density index of LGEs of 90 counties and districts in Zhejiang Province, a cluster analysis is conducted, and the findings are illustrated in Fig. 3. In the figure, the 90 districts and counties are divided into three groups of categories, namely A, B and C. The categorized scenarios of the corresponding counties or districts in each group are summarized in Table 4, and different groups show distinctly different BE characteristics. The business environment index (X) and its first-grade indices (X1-X7) in Group A are significantly superior to the corresponding districts and counties in Group B and C. Using the various index levels of Group A as a reference frame, the average level of B and C in the overall business environment index score is only 52.81% and 28% of that of Group A cities. In detail, the level of first-grade indices (X1-X7) in Group B is equivalent to 46.92%, 40.43%, 53.96%, 53%, 44.72%, 92.58% and 50.69% of that in Group A, respectively. The corresponding distribution density of LGEs(Y2)in Group B is lower, only 20.58% of that in the districts and counties of Group A. As for Group C, the level of seven first-grade indices of business environment is 18.22%, 19.44%, 20.18%, 15.73%, 12.48%, 75.15% and 53.22% of that in Group A, respectively. The corresponding distribution density of LGEs in Group C is only 6.05% of that in Group A.

The above analysis reveals significant differences in the business environment ecology among different districts and counties in Zhejiang Province, with correspondingly distinct spatial distribution patterns observed for LGEs. However, the level of the rule of law environment is relatively high and has the smallest relative difference between groups A, B and C. The reason may be the fact that the overall legal environment within the region of Zhejiang Province is at a high level and there are relatively small spatial differences between different counties and districts.

Business environments that foster the spatial density of LGEs

From the above analysis, we can see the correlation between the distribution density of LGEs and the business environment index has reached the significant level, but the high-density distribution area of LGEs within the administrative region of Zhejiang Province is not naturally located in counties or districts with high business environment index. This apparent paradox underscores the complex, non-linear interactions among business environment factors in shaping enterprise distribution patterns. Through fsQCA methodology, our study systematically investigates how seven key business environment factors interact synergistically to influence spatial distribution of LGEs, ultimately identifying distinct configurations that foster high enterprise concentration across various districts and counties in Zhejiang Province.

Variables and calibration

The antecedent condition variable are the seven first-level indicators of the business environment in each district/county, while the outcome variable is the distribution density of LGEs across these districts/counties. To transform the raw data into fuzzy-set membership scores ranging from 0 to 1, calibration was first conducted for the seven condition variables and one outcome variable. Drawing on prior research and relevant theories66, direct calibration was employed based on the numerical characteristics of the variables. In our analysis, the calibration anchor points were set at the 95%, 50%, and 5% percentiles, representing full membership, the crossover point, and full non-membership, respectively. Additionally, to avoid the exclusion of cases due to exact thresholds, a constant of 0.001 was added to the 0.50 membership score67. The calibration anchor points for each variable are presented in Table 5.

Necessity analysis

The necessity analysis evaluates whether a single condition variable constitutes a necessary condition for the outcome variable. Following prior research16, this study adopts 0.9 as the consistency threshold for necessity analysis. The criterion for determining a necessary condition is a consistency level exceeding 0.9; if met, the condition can be regarded as a necessary condition for the outcome variable. As shown in Table 6, the consistency value of each condition is lower than 0.9. Thus, no necessary conditions for high LGEs distribution density were identified in Group A, B, or C districts/counties.

Configuration analysis

This study sets the original consistency threshold at 0.8, the Proportional Reduction in Inconsistency (PRI) threshold at 0.8, and the frequency threshold at 160. Given the lack of consensus in existing literature regarding the directional effects of specific business environment conditions on the outcome, we adopted a conservative approach in conducting counterfactual analysis. Our analysis assumes that both the presence and absence of individual business environment conditions could potentially contribute to high distribution density of LGEs. Following the literature, core and peripheral conditions for each solution were identified by comparing the intermediate solution with the parsimonious solution.

As shown in Table 7, nine configurations can produce high distribution density of LGEs. Among them, four configurations are identified in Group A districts/counties, two in Group B, and three in Group C. The following sections will provide a detailed analysis of the business-environment configurations that lead to high LGEs distribution density within these three groups.

Following Fiss68, configurations S1a and S1b are neutral permutations as they shared the same core conditions-the presence of financial services. Configuration S1a indicates that a high distribution density of LGEs can occur in conjunction with high-quality financial services, even when other BE conditions (public services, human resources, et al.) are absent. Typical example of this configuration is the Binjiang District. By focusing on the digital finance and digital industry, the district has actively implemented reforms that significantly enhance trade and investment facilitation, as well as overall developmental vitality. Configuration S1b exhibits a mutualistic–symbiotic pattern, when human resources, public services, and market conditions are present as peripheral conditions, it yields a high spatial density of LGEs. The district of Zhenhai exemplifies this configuration. Its financial development service center has taken proactive steps to strengthen finance’s role in underpinning the regional economy, thereby sustaining steady overall economic growth.

Configuration S2a shows that in districts where market environment and innovation capacity are weak, high-quality government services, abundant human capital, and robust public services can still generate high LGEs density. Typical area such as Beilun District exemplifies this configuration. its SME Public Service Platform is expressly designed to resolve the challenges faced by SMEs, offering dedicated modules on fiscal support, tax incentives, financial assistance, industrial upgrading, green development, innovation promotion, and entrepreneurship cultivation. Configuration S2b emphasizes the importance of high-quality government services as a core condition, complemented by peripheral conditions such as a robust rule-of-law environment and strong innovation capacity. Within this ecosystem, the business environment is primarily influenced by a government-led approach, which leads to a high distribution density of LGEs. The Yinzhou District serves as a prime example of this configuration.

Configuration S3 indicates that optimizing financing services, fostering a conducive innovation environment, and consolidating human resources can generate a high density of LGEs. In this context, public services and market conditions are not essential factors influencing the distribution density of LGEs. Typical urban districts and counties include Longwan, Lucheng, Yuecheng, Ouhai, Nanhu, Xiuzhou, and Wuxing. These regions are driven primarily by financial services and innovation ecosystems, which contribute significantly to the high density of LGEs. This configuration highlights how finance and innovation dual-drive mechanisms effectively promote the agglomeration of LGEs. Configuration S4 highlights two core conditions: high financial services and a robust market environment. Peripheral conditions include low human resources, a weak rule of law, insufficient public services, and limited innovation capacity. This configuration fosters a business ecosystem conducive to a high density of Large Growth Enterprises (LGEs). Typical areas following this path include the Jindong and Jiangbei Districts. While Jiangbei excels in market environment, Jindong performs well in financial services. However, neither district demonstrates significant strengths in other dimensions of the business environment.

Configuration S5 illustrates a market-driven path in which a high-quality market environment serves as the core condition, supported by three complementary factors: skilled human capital, advanced financial services and innovation capacity. This configuration promotes high-density distribution of LGEs, exhibiting partial mutualistic symbiosis with market forces as the primary driver. Typical areas such Fenghua, Kecheng, Xiangshan, Xinchang, and Tiantai reveals that robust market environment, human capital, financial services, and innovation capacity can effectively compensate for deficiencies in government services, thereby fostering LGEs agglomerations. Configuration S6 identifies advanced financial services as the core condition, complemented by two key peripheral factors: strong innovation capacity and rule-of-law environment. Empirical evidence from Wuyi and Pujiang counties demonstrates that in regions with deficiencies in government services, public services, human resources, and market environment, strategic emphasis on enhancing financial services, innovation capacity, and legal environment can effectively foster high-density clusters of LGEs. This configuration reveals financial services’ pivotal compensatory function in facilitating industrial specialization and upgrading when other institutional factors are suboptimal, offering an alternative regional development pathway of LGEs.

Configuration S7 features dual core conditions: developed financial services and good market environment, supported by two peripheral factors: efficient public services and quality human capital. This configuration illustrates how financial services and market environment jointly drive a high-density cluster of LGEs. Empirical evidence from Putuo District reveals that even in regions with underdeveloped innovation capacity and weak legal environment, strong market environment, public services, and advanced financial services can collectively stimulate the growth of LGEs. A notable example is the recent establishment of the EX Focus Private Equity Fund under the Zhejiang Free Trade Zone, which is the zone’s first Qualified Foreign Limited Partnership (QFLP) fund, thereby creating new cross-border investment channels.

Robustness test

This study conducted robustness tests on the antecedent configurations generating high density of LGEs. Based on the research of Meuer et al.69, this study conducts a robustness test by increasing the consistency threshold. When the PRI consistency threshold was raised from 0.80 to 0.85 while keeping all other treatments unchanged, the resulting configurations remained fundamentally consistent. The robustness tests confirm the stability of the findings.

Improvement of business environment

Although the nine types of configurations leading to the high distribution density of LGEs achieve the same goal (consequence event), they may not yield the same effectiveness. To address this, we conduct DEA analysis to assess the degree of redundancy of level-one indices of the business environment in 90 counties and districts, and to identify the “negative” list of output deficiencies for LGEs. We divide the typical regions (counties and districts) into three categories, and present the findings in Table 8.

Obviously, if we are in accordance with the input redundancy situation, the scientific reduction of excessive elements of the business environment can properly compensate for the output deficit. Specifically, for Yinzhou District, Cixi, Binjiang District, etc. in Group A, the improvement of the BE is in line with the growth of LGEs, which means that the BE in the region is effective. However, for Yuhang District and Keqiao District, the density of LGEs show that there is obvious redundancy of business environment elements. These districts should ensure an appropriate match in aspects such as innovation capacity and government services, while strengthening the weaknesses in other elements of business environment (e.g. market environment and financial services). For Group B districts and counties, Jiangbei District in Ningbo can serve as a reference model for constructing an efficient business environment ecosystem, rather than pursuing comprehensive excellence in all aspects. For the counties and districts in Group C, there is a general loss of efficiency, and there are no ideal examples of cases worthy of support. These areas require prioritized investments in foundational factors like market environment and innovation capacity, while collaborating with top-performing Group A areas to implement their proven solutions. However, relatively speaking, Sanmen County and Xinchang County have good input efficiency of business environment factors, such as the rubber processing industry in Sanmen County and the biological pharmaceutical industry in Xinchang. For the SMEs in the characteristic industrial clusters, we need to adapt and create a business environment that fits the local characteristic industrial chain.

Conclusion and policy implications

Conclusion

This study, grounded in adaptation theory, has examined the spatial distribution of Little Giant Enterprises (LGEs) and the configuration of the regional business environment (BE) across 90 districts and counties in Zhejiang Province, China. By employing a novel multi-method approach integrating Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), this research provides a configurational perspective on the complex ecosystem factors that foster high LGE density. The principal conclusions are as follows: First, the spatial distribution of LGEs in Zhejiang is markedly heterogeneous and agglomerative. LGEs are predominantly concentrated in the advanced economic corridors of the Hangjiahu and Ningshao plains in northeastern Zhejiang, with Ningbo and Hangzhou emerging as primary hubs. In contrast, the southwestern mountainous regions constitute an economic inert space with significantly lower LGE density. Cluster analysis confirmed this spatial disparity, categorizing the regions into three distinct groups (A, B, and C) with correspondingly graded BE characteristics. Second, the fsQCA results underscore that no single business environment element is a necessary condition for high LGE density. Instead, high density emerges from the synergistic interplay of multiple factors, illustrating the principle of equifinality. We identified nine distinct configuration paths to this outcome: four in high-performing Group A regions, two in intermediate Group B, and three in developing Group C. A comparative analysis of these paths reveals that robust financial services and a efficient market environment act as the most pervasive core conditions, appearing frequently across the majority of configurations. Third, the DEA efficiency analysis further reveals that many regions exhibit significant input redundancies in their BE construction. Over-investment in certain elements (e.g., innovation capacity in Group B, government services in Group C) does not yield a commensurate increase in LGE output. This finding challenges the conventional one-size-fits-all approach to BE optimization and advocates for a more precise, resource-efficient strategy that targets specific regional shortcomings, adhering to the “bucket principle” of strengthening the weakest links.

Policy implications

Based on the granular findings of the QCA and DEA analyses, we propose the following targeted policy recommendations to enhance the cultivation efficiency of LGEs in different regional contexts: Given the foundational role of financial services and the market environment, policymakers should move beyond generic support. For financially mature Group A regions, an advanced “investment-loan linkage” model should be promoted, encouraging partnerships between commercial banks and private equity ventures to provide hybrid financing. For Groups B and C, policy should focus on expanding credit loan pilots by leveraging big data (e.g., tax records, supply chain data) to build corporate credit profiles, thereby reducing reliance on physical collateral and improving capital accessibility for SMEs. Further, policy must ensure a level playing field for SMEs competing in niche markets. Drawing from successful pilots in Hangzhou and Ningbo, measures such as increasing the weighting of technical merits in public procurement bids and implementing a “credit pledge” system can mitigate biases against smaller firms. Furthermore, integrating regional industrial platforms (e.g., Shaoxing’s textile shared labs) with major e-commerce ecosystems (e.g., Alibaba, Ningbo Shipping Exchange) can provide LGEs with end-to-end support from R&D to global marketing, drastically reducing innovation costs and market entry barriers. Moreover, local governments must abandon the inefficient strategy of blanket investment across all BE dimensions. DEA results provide a clear mandate for targeted improvement. Group B should rationalize over-investment in innovation and government services, reallocating resources to strengthen foundational financial and market infrastructures. Group C must prioritize streamlining bureaucratic processes, enhancing market competition, and guaranteeing basic public service delivery before investing in advanced factors. Concurrently, an improved talent introduction system is crucial across all regions to ensure LGEs can recruit the high-level expertise necessary for innovation and gradient growth, thereby promoting more balanced regional development.

Research limitations and future directions

Despite its contributions, this study is subject to several limitations that present avenues for future research. First, while Zhejiang Province offers an ideal setting as the national leader in LGE cultivation, the findings are inherently contextual. The generalizability of the specific configuration paths and policy recommendations to other Chinese provinces or national contexts with different institutional environments remains unverified. Future research should conduct comparative studies across diverse regions to test the robustness and transferability of these findings. Second, this study treats LGEs as a homogeneous group due to data constraints. It does not account for potential sector-specific variations (e.g., advanced manufacturing vs. new IT) in their sensitivity to different business environment factors. A more granular, industry-level analysis could yield deeper, more nuanced insights into the tailored support required for different types of specialized enterprises. Third, the configurational model primarily focuses on socio-economic and institutional factors. It does not explicitly incorporate the moderating effects of deeper contextual variables, such as geographical proximity to innovation hubs or regional cultural factors (e.g., entrepreneurial spirit, risk appetite), which may well influence the effectiveness of the identified BE pathways. Future studies should integrate these geographical and socio-cultural dimensions to build a more holistic theoretical framework.

Data availability

The list of little giant enterprises is available at the following links: Ministry of Industry and Information Technology: [https://www.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/qyj/](https:/www.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/qyj) . The raw data are not publicly available but can be obtained upon request from the first author (Luqian Wang).

References

Simon, H. Hidden champions: the definition. In Hidden Champions in the Chinese Century https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92597-03 (Springer, 2022)

Zhu, H., Liu, B. & Chen, B. The rise of specialized and innovative little giant enterprises under China’s ‘dual circulation’ development pattern: An analysis of spatial patterns and determinants. Land 12(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010259 (2023).

Garcia-Vega, M. Does technology diversification promote innovation? An empirical analysis for European firms. Res. Policy. 35, 230–246 (2006).

Ding, Y. & Wu, X. Will the cultivation of “Little Giant” enterprises boost the innovation vitality of manufacturing SMEs? Evidence from the policies for SRDI SMEs. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 40(12), 108–116 (2023).

Bade, F. J. & Nerlinger, E. A. The spatial distribution of new technology-based firms: Empirical results for West-Germany. Pap. Reg. Sci. 79(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101100050041 (2000).

Stern, N. A Strategy for Development (World Bank Publications, 2002).

Gogokhia, T. & Berulava, G. Business environment reforms, innovation and firm productivity in transition. Econ. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 11, 221–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00167-5 (2021).

Zhang, M., Xu, H. & Feng, T. Business environment, relationship lending and technological innovation in SMEs. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 41(02), 35–49 (2019).

Aldrich, H. E. & Ruef, M. Organizations Evolving (Sage, 2006).

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W. & Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Beck, T. Financial development and international trade: is there a link?. J. Int. Econ. 57(1), 107–131 (2002).

Lim, D. S. K., Oh, C. H. & De Clercq, D. Engagement in entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Interactive effects of individual-level factors and institutional conditions. Int. Bus. Rev. 25, 933–945 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. “Research on evaluation of doing business in Chinese cities” research group, theoretical logic, comparative analysis, and the countermeasures of doing business assessment in Chinese cities. Manag. World 37(5), 98–112 (2021).

Greenwood, R. et al. Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 5, 317–371 (2011).

Douglas, E. J., Shepherd, D. A. & Prentice, C. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis for a finer-grained understanding of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 35, 105970 (2020).

Ragin, C. C. The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. 26 (University of California Press, 1987).

Zhang, M. et al. Different paths but same destination: Configurational antecedents of strategic change and their performance implications. Manag. World 36(9), 168–186 (2020).

An, J. & Liu, G. Business environment for high-quality development: A qualitative comparative analysis based on fsQCA. Sci. Manag. Res. 41(2), 101–110 (2023).

Xia, Q. & Zhu, Q. Growth of quantity and improvement of quality: business environment and specialized, refined, unique and innovative firms—based on the fsQCA method. Res. Econ. Manag. 44(8), 126–144 (2023).

Zhu, H., Liu, R. & Chen, B. The rise of specialized and innovative little giant enterprises under China’s ‘Dual Circulation’ development pattern: An analysis of spatial patterns and determinants. Land https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010259 (2023).

Zhang, Y. Can the “Little Giant” label enhance firms’ supply chain positions?. Econ. Lett. 246, 112064. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONLET.2024.112064 (2025).

Rising ‘Little Giants’ Showcasing China’s Private Sector Vitality - Global Times Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202502/1328865.shtml (Accessed 10 Sept 2025).

Johann, M., Block, J. & Benz, L. Financial performance of hidden champions: Evidence from German manufacturing firms. Small Bus. Econ. 59, 873–892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00557-7 (2022).

Schenkenhofer, J. Hidden champions: a review of the literature & future research avenues. Manag. Rev. Q. 72(02), 417–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00253-6 (2022).

Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E. & Schenkenhofer, J. Internationalization strategies of hidden champions: lessons from Germany. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 26(1), 2–24 (2018).

Voudouris, I. et al. Greek hidden champions: Lessons from small, little-known firms in Greece. Eur. Manag. J. 18(6), 663–674 (2000).

Carolin, G. & Rita, R. Electricity connections and firm performance in 183 countries. Energy Econ. 76, 344–366 (2018).

Gaganis, C., Pasiouras, F. & Voulgari, F. Culture, business environment and SMEs’ profitability: Evidence from European countries. Econ. Model. 78, 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.09.023 (2019).

Aterido, R., Hallward-Driemeier, M. & Pagés, C. Big constraints to small firms’ growth? Business environment and employment growth across firms. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 59(3), 609–647 (2011).

Li, Z. Research on evaluation and comparison of business environment in China’s major urban agglomerations. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 36(6), 17–28 (2021).

Du, Y. Z., Liu, Q. C. & Cheng, J. Q. What kind of business environment ecosystem will contribute to city-level high entrepreneurial activity? A research based on institutional configurations. Manag. World 36(9), 141–155 (2020).

Gogokhia, T. & Berulava, G. Business environment reforms, innovation and firm productivity in transition economies. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 11, 221–245 (2021).

Hemmert, M. et al. The distinctiveness and diversity of entrepreneurial ecosystems in China, Japan, and South Korea: An exploratory analysis. Asian Bus. Manag. 18(3), 211–247 (2019).

Yuan, D., Zhou, J., Qin, R. & Li, J. Private enterprise innovation investment: an analysis based on the perspective of business environment. Economist 8, 89–98 (2021).

Wiklund, J. & Shepherd, D. A. Where to from here? EO-as-experimentation, failure and distribution of outcomes. Entrep. Theory Pract. 35, 925–946 (2011).

Bradley, S. W., Shepherd, D. A. & Wiklund, J. The importance of slack for new organizations facing ‘tough’ environments. J. Manag. Stud. 48(5), 1071–1097 (2011).

Nam, V. H. & Tram, H. B. Business environment and innovation persistence: the case of small- and medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 30(3), 239–261 (2021).

Haschka, R. E., Herwartz, H., Struthmann, P., Tran, V. T. & Walle, Y. M. The joint effects of financial development and the business environment on firm growth: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Comp. Econ. 50(2), 486–506 (2022).

Bachmann, R. & Elstner, S. Firm optimism and pessimism. Eur. Econ. Rev. 79, 297–325 (2015).

Liu, J. & Yang, Y. Improving high-tech enterprises’ new product development performance through digital transformation: a configurational analysis based on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Manag. Decis. Econ. 44, 3878–3892. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3926 (2023).

Song, Y., Wang, J. & Chen, H. The formation mechanism of organizational resilience of enterprises in the context of anti-globalization: a case study based on Huawei. Foreign Econ. Manag. 43(05), 3–19 (2021).

Dai, X. Business environment and GVC upgrading. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 05, 48–61 (2020).

Augier, P., Dovis, M. & Gasiorek, M. The business environment and Moroccan firm productivity. Econ. Transit. 20(2), 369–399 (2012).

Glaeser, E. L. & Kerr, W. R. Local industrial conditions and entrepreneurship: How much of the spatial distribution can we explain?. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 18(3), 623–663 (2009).

Ibata-Arens, K. Beyond technonationalism: Biomedical innovation and entrepreneurship in Asia. Soc. Forces 99(1), e18. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa028 (2020).

Lee, S. & Park, G. The impact of INNO-BIZ policy on SME innovation in Korea. J. Asian Econ. 68, 101–115 (2020).

Kim, J. et al. Government procurement and SME growth: Evidence from INNO-BIZ. Small Bus. Econ. 58(3), 1327–1345 (2022).

Mao, J. & Guo, S. Research on the driving path of high-quality development of the “new, distinctive, specialized and sophisticated” SMEs-qualitative comparative analysis based on the TOE framework. Fudan J. (Soc. Sci.) 65(01), 150–160 (2023).

Dong, Z. & Li, C. The high-quality development trend and path choice of the superior small and medium-sized enterprises. Reform 10, 1–11 (2021).

Ding, J., Liu, X., Wang, D. & Yin, J. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of China’s national-level “Little Giant” Enterprises. Econ. Geogr. 10, 109–118 (2022).

Hsuan, P. H., Tian, X. & Xu, Y. Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 112, 116–135 (2014).

Brown, J. R., Martinsson, G. & Petersen, B. C. Law, stock markets and innovation. J. Financ. 68(4), 1517–1549 (2013).

Ciftci, M. & Cready, W. M. Scale effects of R&D as reflected in earnings and returns. J. Account. Econ. 52, 62–80 (2011).

Li, Z. Evaluation of Business Environment in Chinese Cities (China Development Press, 2018).

Su, M. & Zheng, Y. A legal study based on geographic methods: spatial and temporal differences and influencing factors in the construction level of China’s law-based government. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1128. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05376-9 (2025).

Kondruk, N. E. & Malyar, M. M. Analysis of cluster structures by different similarity measures. Cybern. Syst. Anal. 57, 436–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10559-021-00368-4 (2021).

Van de Velden, M., D’Enza, A. I. & Palumbo, F. Cluster correspondence analysis. Psychometrika 82, 158–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-016-9514-0 (2017).

Wu, W., Zeng, X., Chen, Y., Tang, G. & Xu, J. Research on the habitat portrait of enterprises with professionalism, refinement, specialization and novelty from the perspective of regional integration of Yangtze River Delta. China Bus. Rev. 10, 5–9 (2022).

Misangyi, V. F. et al. Embracing causal complexity: The emergence of a neo-configurational perspective. J. Manag. 43(1), 255–282 (2017).

Pappas, I. O. & Woodside, A. G. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA): guidelines for research practice in information systems and marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 58, 102310 (2021).

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W. & Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 6(2), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8 (1978).

Kao, C. Efficiency decomposition in network data envelopment analysis: A relational model. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 192, 949–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2007.10.008 (2009).

Chen, Y., Zhao, H. & Yu, M. Innovation efficiency and its influencing factors of China’s creative industry—based on the two-stage DEA model. Econ. Geogr. 38(7), 117–125 (2018).

Rezaeiani, M. J. & Foroughi, A. A. Ranking efficient decision making units in data envelopment analysis based on reference frontier share. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 264, 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.06.064 (2018).

Tang, G., Wang, L., Zheng, T. & Wu, W. What types of business environment fosters the emergence of more specialized and sophisticated “little giant” enterprises?–An empirical study based on the TOE framework and configuration adaptation theory. Manag. Decis. Econ. 45(3), 1557–1572 (2024).

Thiem, A. & Duşa, A. Fuzzy-set QCA. In Qualitative Comparative Analysis with R. Springer Briefs in Political Science, 5 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4584-5_4 (Springer, 2013).

Stokke, O. S. Qualitative comparative analysis, shaming, and international regime effectiveness. J. Bus. Res. 60(5), 501–511 (2007).

Fiss, P. C. Building better causal theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 54(2), 393–420 (2011).

Meuer, J., Rupietta, C. & Backes-Gellner, U. Layers of co-existing innovation systems. Res. Policy 44(4), 888–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.01.013 (2015).

Zhou, Z., Lei, L. & San, Z. Business environment and high-quality development of enterprises—Mechanism analysis based on the perspective of corporate governance. Public Financ. Res. 05, 111–129 (2022).

Liu, J. & Tang, J. Business environment, investment capacity, and corporate investment efficiency: an empirical study of listed companies in China. J. Manag. Sci. China 25, 88–106 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by Zhejiang Shuren University Educational Reform Foundation (grant number jg2024016), and Zhejiang Shuren University Scientific Research Program (grant number 2024R091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Luqian Wang, Kaixing Hong, did the Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Wasi Ul Hassan Shah did supervision, methodology, and writing, which were reviews. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Hong, K. & Ul Hassan Shah, W. Spatial distribution and business environment of specialized and sophisticated Little Giant enterprises in Zhejiang Province. Sci Rep 15, 37697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21511-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21511-7