Abstract

The current study focused on evaluating the behavior of 4-amino-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(2 H)-one (1a) along with its tautomers, as well as 4-amino-6-methyl-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(2 H)-one (2a) and its tautomers as potential corrosion inhibitors for copper surfaces with two different miller indices namely Cu (1 1 1) and Cu (1 1 0) by employment of a DFT approach. Among different tautomers, the most negative adsorption energies were observed for the following compounds: 4-amino-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(6 H)-one (1c), 4-amino-5-hydroxy-1,2,4-triazine-3(4 H)-thione (1d), 4-amino-6-methyl-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(6 H)-one (2c), and 4-amino-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-1,2,4-triazine-3(4 H)-thione (2d). Critical parameters associated with the molecular performance of triazine derivatives as corrosion inhibitors include the EHOMO, ELUMO, ΔEgap, total hardness (η), electronegativity (χ), electrophilicity index (\(\:\omega\:\)), and the electron transfer fraction from the inhibitor molecule to the copper atom (ΔN) were computed to assess their efficacy in corrosion prevention. The active sites of inhibitors were determined through the analysis of Mulliken charges, highlighting that heteroatoms exhibit the highest electron density and thus serve as key active sites. This observation aligns with Fukui, which indicates that the highest fk+ and fk− correspond to sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corrosion refers to the deterioration of metallic materials due to chemical or electrochemical reactions with their environment. This process can lead to significant loss of metal structures and may ultimately result in structural failure1. Several critical factors influence the rate of corrosion, including the metal surface characteristics, the chemical composition of the surrounding environment, as well as pressure and temperature2,3.

Copper is a valuable metal renowned for its remarkable corrosion resistance in various atmospheric and chemical settings4. This resistance mainly arises from developing a protective passive oxide film or a non-conductive layer of corrosion products on the material’s surface5,6. Copper corrosion can occur under certain environmental conditions. Factors leading to copper corrosion include moisture, humidity, sulfur dioxide, strong acids or alkalis, and exposure to saltwater7. This corrosion process and the resulting formation of corrosion products can negatively impact the performance and efficiency of systems made from copper. Hence, the protection of copper from corrosion is a critical concern8.

While various strategies, such as applying anti-corrosive coatings9,10, or alloying copper with other metals, can mitigate copper corrosion11,12, the most effective, secure, and economical method is using corrosion inhibitors13,14,15,16,17. A corrosion inhibitor is a specific chemical additive that, when introduced in low concentrations into a corrosive environment, significantly reduces the corrosion rate18. This reduction occurs without altering the concentration of the corrosive medium itself, allowing for enhanced material longevity and performance in hostile conditions. Corrosion inhibitors like molybdates and chromates are increasingly being substituted with organic alternatives due to their toxicological concerns. Organic corrosion inhibitors function by adsorbing onto the metal surface, forming a protective film that significantly reduces the electrochemical reactions responsible for corrosion in the presence of aggressive electrolytes. This mechanism enhances the metal’s resistance to corrosive environments, effectively mitigating the corrosion process19. Key adsorption sites for bonding with metal surfaces include heteroatoms like S, P, N, and O, along with aromatic rings present in their structures20,21,22,23.

Organic molecules containing nitrogen are proven to be highly effective inhibitors in terms of performance. Azoles, as an important family of heterocyclic compounds including pyrrole, pyrazole, tetrazole, and imidazole24,25,26, along with pyridines27, pyrimidines, and their benzene-fused counterparts28, are frequently employed as potent inhibitors. The triazine molecule distinctly features three nitrogen atoms that are arranged in multiple configurations. Due to their importance in the synthesis of biologically active compounds and the formation of stable complexes with metal ions, the synthesis of 3-thioxo-1,2,4-triazin-5-one derivatives has been of interest to researchers. This has led to a couple of preparation methods that have been reported in the literature29,30. A study by Zhao et al. examined the corrosion inhibition performance of two specific triazine derivatives, 6-N, N-bis(6-methylheptyl)amine-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-dithiol monosodium and 6-dibutylamino-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-dithiol monosodium, on copper in synthetic seawater, observing spontaneous adsorption and strong interactions with the copper substrate31. Similarly, Obot et al. used advanced density functional theory to analyze the adsorption properties of different triazine derivatives, focusing on hexahydro-s-triazine compounds that exhibit variations in the para-position substituents on their phenyl rings, specifically H, CH3, OCH3, NH2, and NO2 ( Inh1 Inh5) and the results revealed strong interaction potentials between these triazine derivatives and steel substrates32. Ayman et al. also studied hydrazino-methoxy-1,3,5-triazine derivatives and confirmed their ability to substantially reduce steel corrosion rates in acidic conditions, even at minimal concentrations. Together, these studies underscore the remarkable promise of triazine derivatives as versatile and robust corrosion inhibitors across different metals and environments, highlighting their potential as effective and economical solutions33.

To develop effective corrosion inhibitors, the triazine ring’s chemical functionalization at the carbon or nitrogen atoms is essential because none of the natural varieties of 1,2,3-triazines, 1,2,4-triazines, or 1,3,5-triazines serve as effective corrosion inhibitors34,35. This can be effectively accomplished by varying alkyl chain lengths, introducing electron-withdrawing or electron-releasing substituents, and incorporating additional heteroatoms, heterocycles, or phenyl rings. Such modifications optimize inhibitory properties and enhance performance in corrosive environments36,37,38. These molecules possess significantly increased active sites that effectively engage with the metal surface and are coupled with a larger geometrical surface area, leading to superior surface coverage. Numerous triazine-based anti-corrosion agents have been thoroughly researched and proven effective for application in both neutral and acidic corrosive environments. A notable structural feature of triazine heterocycles is their capacity to adopt tautomeric forms, especially when specific heteroatoms like oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur are positioned adjacent to the nitrogen atoms of the heterocycles39.

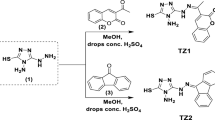

A study conducted by John et al. explored how three different 1,2,4-triazine compounds inhibit the corrosion of mild steel in a 1 M hydrochloric acid solution. They employed a combination of experimental methods, alongside theoretical calculations. Their findings revealed that the type of functional group attached to the triazine ring significantly influences the corrosion inhibition efficiency, ranking in the order of CH2Ph > But > Me40. In a different study, John et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition efficiency of two compounds: 4-amino-6-methyl-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazine-5(2 H)-one (AMTDT) and (4-amino-4 H-1,2,4-triazole-3,5-diyl) dimethanol (ATD). They conducted both experimental and theoretical analyses and discovered that, while the inhibitors exhibited nearly identical effectiveness at higher concentrations, AMTDT demonstrated superior efficiency at lower concentrations41. In this study, we focus on two series of triazine derivatives: the first is 4-amino-3-thioxo-6-methyl-1,2,4-triazine-5-one (1a) and its tautomers, designating them as 1b, 1c, and 1d, while the second series involves the introduction of a methyl group at the C5 position of 4-amino-3-thioxo-6-methyl-1,2,4-triazine-5-one which was 4-amino-6-methyl-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4 triazin-5 (2 H)-one (2a) and its tautomeric forms labeled as 2b, 2c, and 2d. The investigation of substitution effects in organic chemistry is a critical area of study as the integration of substituents can substantially alter the adsorption characteristics, electronic properties, and spatial arrangement of compounds. Specifically, introducing a methyl group can also enhance the hydrophobic nature of the protective film, thereby improving its resistance to moisture and various corrosive agents. We aim to evaluate the impact of introducing a methyl group at the C5 position on both the adsorption behavior and corrosion inhibition efficiency.

What sets this project apart from previous ones is the thorough assessment of the tautomeric forms when adsorbed on copper surfaces with two different Miller indices, Cu (1 1 1) and Cu (1 1 0). The inhibitors were analyzed in both parallel and perpendicular orientations on these surfaces. Previous studies have explored these molecules through both experimental and theoretical approaches; however, this research takes a direction by employing DFT calculations to comprehensively assess the inhibition efficiency of two distinct series of inhibitors. Evaluations included Mulliken charge, Fukui function, partial density of states (PDOS), and various quantum chemical parameters related to the inhibitors. The goal is to identify their active sites, thereby providing a thorough assessment of the computational aspects of inhibitor efficiency, which differentiates this work from earlier studies (Scheme 1).

Computational details

Computer simulation techniques have been developed to assess inhibition performance or to delve into the specifics of inhibition mechanisms. Among the various methods of computer simulation, quantum chemistry calculations have become a popular choice for assessing the effectiveness of corrosion inhibitors. This method allows for the prediction of inhibitor molecules’ ability to either donate or accept electrons by analyzing global reactivity parameters. These include factors like the gap of energy between HOMO (the highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO (the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital), as well as chemical potential and other relevant metrics42,43.

In this study, all calculations were conducted using the DMol3 program package within the Material Studio software, version 2020, based on density functional theory. Table 1 displays the parameters used in the DMol3 calculation. The dispersion-corrected PW91 functional has been used for the calculation of the interaction of inhibitors with the Cu surfaces44,45,46. The corrected version of this functional can capture the dispersion forces between the metal surface and the inhibitor. The most stable Miller index for copper (Cu) surfaces is typically the (1 1 1) face. The (1 1 1) surface of copper has a close-packed structure, which means that it has a high atomic density and a lower surface energy compared to other Miller indices like (1 0 0) and (1 1 0). Surfaces with lower surface energy exhibit greater stability because they minimize the tendency for atoms to rearrange or migrate47,48.

The inhibitors’ energy of adsorption on copper surfaces was calculated by Eq. 149:

Ecomplex stands for the total energy of inhibitors on the surface. It has been determined that a greater amount of negative energy tends to demonstrate enhanced stability. Additionally, other quantum parameters were calculated by the following equations50,51, and the highest occupied molecular orbital is represented by the symbol EHOMO, and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital is represented by the symbol ELUMO:

The Cu (1 1 1) surface is contained within a simulation box with dimensions of 10.224 Å × 10.224 Å × 24.174 Å. 48 Cu atoms in a four-layer slab model were used to construct the copper surface. Likewise, the Cu (1 1 0) surface is enclosed within a box measuring 14.459 Å × 10.224 Å × 23.834 Å. A four-layer slab model consisting of 64 copper atoms, was employed in creating the copper surface (Fig. 1).

The symbol φ corresponds to the metal surface’s work function, with specific values for different crystal planes of copper: φCu (1 1 1) = 4.94 eV, and φCu (1 1 0) = 4.48 eV.

Results and discussion

Molecular geometry

To evaluate the efficacy of corrosion inhibitors, the relative stability of tautomers in the gas phase before adsorption is listed in Table 2. Taking a more detailed examination of Table 2, it is clear that the stability trend of series 1 inhibitors is as follows: 1a\(\:>\) 1b\(\:>\) 1c\(\:>\) 1d. For series 2 inhibitors, the stability is as follows: 2a\(\:>\) 2b\(\:>\) 2d\(\:>\) 2c. After adsorption, the intramolecular bond length of inhibitors can either increase or decrease. Indeed, when an inhibitor is adsorbed on the surface, copper atoms can donate or accept electron density via d-orbitals, which interact with the molecular orbitals of the inhibitor. This redistribution of charge can alter electron densities in specific bonds, strengthening some while weakening others, and changing their lengths52. Therefore, Table 3 presents the key intramolecular bond lengths of the inhibitors participating in the adsorption process, both prior to and following adsorption. Except for 1a molecule, all measured bond lengths exhibit an increase upon adsorption, with this change being particularly pronounced in the 1c and 2c inhibitors. For example, after the 2c molecule is adsorbed on the Cu (1 1 0) surface in a parallel mode, the bond length of S1 = C2 increases by 0.234 Å. This indicates a strong interaction, such as chemisorption, where a chemical bond is formed between the inhibitors and the surface. This happens because the electrons involved in the bond after adsorption are shared with the surface atoms, weakening the original bond in the inhibitors.

Evaluation of adsorption energies of triazine derivatives on the Cu (1 1 1)

The adsorption energy of triazine derivatives on the Cu (1 1 1) in two distinct configurations, parallel and perpendicular, is summarized in Table 4, and their optimized adsorption structures are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3. Consider Table 4, which indicates that the adsorption energies are nearly similar in parallel and perpendicular geometries. To gain a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of triazine derivatives as inhibitors, their adsorption energy on the surface is calculated, and a more negative energy means better performance toward corrosion. It is apparent in Table 4, the most negative energy in series 1 molecules belongs to 1c inhibitor, and in perpendicular and parallel configurations, its energy is -85.75 and − 81.24 kcal mol− 1, respectively, and it is adsorbed to the surface from S1 and N3 positions. After the 1c molecule, the adsorption energy of 1d in perpendicular and parallel configurations with − 65.69 and − 61.11 kcal mol− 1, respectively, has the most negative value in series 1. When 1a is adsorbed from S1, its adsorption energy is nearly the same in both the parallel and perpendicular orientations. However, the parallel form is more stable, exhibiting an adsorption energy of -48.73 kcal mol− 1. 1b molecule is bonded from N4 to the surface and in two adsorption configurations, its Eads is about − 46 kcal mol− 1. The adsorption energies for the series 2 molecules are more negative compared to those in series 1, indicating a heightened corrosion inhibition efficiency associated with the methyl group’s introduction at the C5 position. This increased adsorption energy reflects a stronger interaction arising from the structural modification, underscoring the importance of the C5 substitution in enhancing corrosion resistance. Notably, molecule 2c exhibits the greater negative adsorption energy on the Cu (1 1 1) surface, registering − 97.81 kcal mol− 1 in a perpendicular orientation with bonding through S1 and N3. In a parallel configuration, with bonding through S1 and N4, it shows a value of -93.83 kcal mol− 1. 2d in parallel is adsorbed from two sites of S1 and N4, which showed more negative adsorption energy (-77.57 kcal mol− 1) compared to 2d perpendicular, which is adsorbed from only S1, and the adsorption energy is -71.10 kcal mol− 1. The adsorption energies of 2a and 2b have quite close values and are almost − 60 kcal mol− 1.

The Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔGads) for the inhibitors was evaluated. A negative ΔGads signifies a spontaneous adsorption process53; and, in this study, the observed ΔGads on the Cu (1 1 1) surface is negative, indicating that the adsorption is spontaneous.

The interaction between metals and inhibitors can be categorized as either chemisorption or physisorption. Chemisorption involves the formation of covalent bonds between the molecules and the surface, while physisorption relies on van der Waals dispersion forces. Chemisorbed inhibitors offer better protection by reducing the reactivity of the metal to which they are attached. On the other hand, physisorbed inhibitors play a vital role by forming a physical barrier that effectively blocks the entry of corrosive agents, especially when dealing with large molecules54. Therefore, here the covalent radii of N-Cu and S-Cu are compared with the distance of S from Cu and the distance of N from the surface. So, according to the calculations presented in Table 4, the distance between the N atom of inhibitor molecules and the Cu atom of the surface, denoted as d N−Cu, ranges from approximately 1.940 to 2.130 Å, and according to the calculations for covalent radii, the sum of the nitrogen atom radius (\(\:{r}_{cov\:}^{N}\), 0.71 Å) and copper atom radius (\(\:{r}_{cov}^{Cu}\), 1.32 Å) is 2.03 Å. Hence, the length of the N-Cu covalent bond is close to the related molecule-surface distance. Moreover, the distance between the S atom of inhibitor molecules and copper surface, referred to as d S−Cu, is between about 2.34 and 2.60 Å, and the S-Cu covalent bond is 2.34 A˚ (\(\:{r}_{cov}^{s}+{r}_{cov}^{Cu}=\) 1.05+ 1.32 = 2.34 Å), which is close to dS−Cu. So, the similarity of N-Cu and S-Cu covalent bond lengths to the corresponding molecule–surface distances suggests the presence of chemisorption between inhibitor molecules and the copper surface54,55,56, the confirmation of this finding is reflected in the adsorption energy values, which range from − 46 to -98 kcal mol−1. These values go beyond the typical range seen in physisorption, strongly indicating that chemisorption is occurring57. Moreover, to bring this discussion to a close, many studies on corrosion inhibitors employ the standard free energy of adsorption as a criterion to differentiate between physisorption and chemisorption. The classifications are as follows: physisorption occurs when ΔGads\(\:>\) − 4.78 kcal mol−1; mixed physisorption/chemisorption is indicated by − 4.78 kcal mol− 1\(\:<\)ΔGads\(\:<\)− 9.56 kcal mol−1; and chemisorption is characterized by ΔGads\(\:<\)− 9.56 kcal mol− 158,59,60,61,62. As shown in Table 4, all measured ΔGads values are significantly lower than − 9.56 kcal mol−1, which supports our assertion that the inhibitors are chemisorbed onto the surface.

Evaluation of adsorption energies of triazine derivatives on the Cu (1 1 0)

The adsorption energy of triazine derivatives on the Cu (1 1 0) is summarized in Table 5, while the optimized structures in both parallel and perpendicular orientations are depicted in Figs. 4 and 5. The adsorption energies on Cu (1 1 0) exhibit a similar pattern to those observed on Cu (1 1 1), and similarly, the incorporation of a methyl group at the C5 position of series 2 triazine derivatives results in increased adsorption energies. It is evident from Table 5 that the 1c inhibitor in series 1 possesses the most negative energy. When the 1c molecule is oriented perpendicularly, it is adsorbed through S1 and N3, exhibiting adsorption energy of -93.37 kcal mol− 1, and the S1 = C2 and N3 = N4 bonds, as indicated in Table 3, exhibited an increase of 0.104 and 0.101 Å in their bonds, respectively that this increase can be due to the transfer of charge from the S1 and N3 atoms to the surface. In the parallel configuration, the adsorption takes place through S1 and N9, with an energy of -76.07 kcal mol− 1. After that, 1d showed a strong interaction with the surface, and when oriented perpendicularly, it is adsorbed from S1 and N3 with an energy equal to -66.04 kcal mol− 1, and when oriented parallelly, it is adsorbed from S1 and N4 with an energy equal to -62.09 kcal mol− 1. When two series of inhibitors’ adsorption energies on the Cu (1 1 0) are compared, the strongest interaction with the surface belongs to the 2c compound, which is adsorbed from S1 and N3, and energies in perpendicular and parallel are equal to -114.04 and − 99.34 kcal mol− 1, respectively. Moreover, the distance between S1 and Cu atoms is approximately 2.27 to 2.45 Å, and the distance between N and Cu atoms ranges from 1.97 to 2.18 Å. These measurements closely resemble the covalent bond lengths for S-Cu and N-Cu. Given the proximity of the adsorbed atoms to the surface, molecules positioned either vertically or parallelly predominantly engage with the surface by creating a covalent bond. This is supported by the range of adsorption energy levels observed for the inhibitors, which varies from − 44 to -114 kcal mol− 1, clearly pointing to the occurrence of chemisorption. Moreover, the measured ΔGads for the Cu (1 1 0) surface is also negative, similar to that of the Cu (1 1 1), which indicates that adsorption on this surface is likewise spontaneous and as demonstrated in Table 5, all measured ΔGads values fall significantly below − 9.56 kcal mol− 1, reinforcing our claim that the inhibitors are chemically adsorbed onto the surface.

The adsorption characteristics of inhibitors reveal significantly higher absolute adsorption energies on the Cu (1 1 0) surface (Table 5) compared to the Cu (1 1 1) surface (Table 4). For instance, the adsorption energy of the 2c molecule on Cu (1 1 0) is measured at -114.04 kcal mol− 1 when oriented perpendicularly. In contrast, the same molecule exhibits an adsorption energy of -97.81 kcal mol− 1 on the Cu (1 1 1) surface. This disparity suggests that the Cu (1 1 0) surface facilitates stronger adsorption interactions, resulting in more stable and effective bonding of the inhibitors. Consequently, Cu (1 1 0) demonstrates superior performance in terms of adsorption strength and inhibition efficiency relative to Cu (1 1 1).

Partial density of States (PDOS)

To gain a deeper understanding of the electronic interactions between inhibitors and the surface, the partial density of states of the s and p orbitals of the inhibitor molecules, alongside the d orbitals of both the copper surface with two Miller indices of (1 1 1) and (1 1 0) surfaces, were analyzed. These states are examined both before (shown in the bottom panel) and after (shown in the top panel) adsorption, in both parallel and perpendicular orientations. In Fig. 6, the PDOS for inhibitors oriented perpendicularly on the Cu (1 1 0) surface is presented. However, the remaining plots due to the similarity are available in the supplementary information (Figure S1- Figure S3). The Fermi energy level was set to zero, and it is displayed with dotted vertical lines63. In the analysis of the PDOS of the 1c molecule before and after adsorption on the Cu (1 1 0) surface, it is observed that the molecule is adsorbed to the surface via two S1 and N3 atoms. The s orbital of the S1 atom shows a range from − 2390 to approximately + 10 eV before adsorption, while the range after adsorption decreases significantly, falling from − 25 to 0 eV, and the peak intensity reduces to roughly one-third of its original value. The p orbital of the S1 atom presents two minor peaks at -380 and − 266 eV prior to adsorption, with a substantial peak at -150 eV. After adsorption, this orbital exhibits a continuous peak from − 22 to 0 eV, and the peak intensity decreases to approximately one-sixth of its original value. Regarding the d orbital of the copper atom (atomic number 40), a peak with higher intensity is recorded prior to adsorption, reaching a value of 6.5 electrons eV− 1. In contrast, post-adsorption, this intensity reduces to 4.5 electrons eV− 1. For the N3 atom in the s orbital, there is a distinct peak observed at -380 eV, accompanied by a continuous peak ranging from − 22 to + 15 eV prior to adsorption. Following the adsorption process, the sharp peak disappears, resulting in a continuous peak that extends from − 22 to 0 eV. Additionally, the intensity of the peak decreases to approximately one-fourth of its original value. In the p orbital, there are two distinct peaks observed at -376 eV and − 266 eV, along with a continuous peak ranging from − 22 to + 15 eV prior to adsorption. After adsorption, the peaks in the positive energy region are eliminated, leaving a continuous peak from − 22 to 0 eV, which shows a reduction in intensity to half of its original value. Concerning the d orbital of the copper atom before and after adsorption, its range remains stable; however, its intensity decreases from − 6.5 to -4.5 electrons eV⁻¹. When comparing the PDOS of this molecule with other inhibitors on two copper surfaces, both in parallel and perpendicular configurations, a consistent trend is observed across all PDOS profiles. So in general, Triazine derivatives are adsorbed from N, S, or both to the surface as inhibitors. The s orbitals of N atoms before adsorption have peaks ranging from − 380 to + 15 eV, while the range for S atoms is wider, spanning from − 2400 to + 15 eV. This data indicates that S atoms exhibit a broader energy range compared to N atoms before adsorption. Before adsorption, the range of p orbitals in both N and S atoms is between − 380 to + 15 64. After being adsorbed, the peaks of the s and p orbitals are observed within the range of -25 to 0 eV, and this range only varies for the 2b molecule (Figure S1) that is adsorbed on the Cu (1 1 1), which is from − 1 to 0 eV. Initially, the energy levels are distinct, but when triazine derivatives are adsorbed onto the surface, the peaks in the positive range are eliminated, their intensity declines, and peaks are broadened significantly. This change indicates a strong interaction between the inhibitors and the copper surface. The d-orbital of the surface both before and after adsorption was also evaluated. After adsorption, the intensity diminished, and the peaks became slightly broader, suggesting a strong interaction between the inhibitor and the surface65.

PDOS diagrams of triazine derivatives before (light blue) and after (light red) adsorption perpendicularly on the Cu (1 1 0) surface. (The initial columns on the left illustrate the s orbitals, while the subsequent columns present the p orbitals of the inhibitors. The third set of columns represents the d orbitals characteristic of the copper surface.)

Analysis of the molecular inhibitors’ activity

Quantum chemical parameters

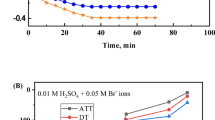

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) are crucial for comprehending the molecules’ reactivity toward the surface and establishing their correlation with the chemical structure66 and FMOs for triazine derivatives are displayed in Fig. 7. The HOMO and the LUMO are the key molecular orbitals that influence reactivity. EHOMO assesses the electron donation ability of a molecule; a higher value indicates a greater inclination to donate electrons to the d orbitals present on the surface. ELUMO reflects the electron-gaining capacity of a molecule, and a lower ELUMO indicates greater inhibition efficiency67,68. A lower value for ΔEgap suggests more favorable adsorption of inhibitors on the surface, subsequently improving their efficacy in mitigating corrosion. ΔEgap values for these inhibitors, as shown in Fig. 8, indicate the following trend: 2b > 1b > 2a > 1a > 1d > 2d > 1c > 2c so their inhibition efficiency order is 2c > 1c > 2d > 1d > 1a > 2a > 1b > 2b and this aligns with the results presented in Tables 4 and 5, where the maximum absolute adsorption values were observed for inhibitors 2c, 1c, 2d, and 1d. Also, a plot of ΔEgap vs. adsorption energies show good correlation with R2 (correlation coefficient) values in the range of 0.7877–0.9956.

A soft molecule is defined by a relatively small energy gap between its HOMO and LUMO69. Conversely, a hard molecule exhibits a larger energy gap between these two orbitals70. As mentioned previously, a molecule with a smaller energy gap exhibited better performance as a corrosion inhibitor. According to the information presented in Table 6, the trend of high softness and low hardness of inhibitors is consistent with the ΔEgap order (2c > 1c > 2d > 1d > 1a > 2a > 1b > 2b). Electronegativity serves as a critical parameter that illustrates the electron transfer dynamics between inhibitors and metal substrates. As electronegativity increases, the propensity for electron transfer from the inhibitor to the substrate decreases. According to Table 6, the 2d and 1d, with electronegativities of 4.109 and 4.221 eV, respectively, demonstrate a strong tendency to preserve the surface against corrosion71. The electrophilicity index (ω) quantifies an electrophile’s ability to accept electrons, indicating its capacity to engage with an adjacent electron reservoir. This measure reflects the potential for electron acceptance, which can be a fraction of unity or greater, thereby characterizing the electrophile’s reactivity in electron-rich environments72. In the present study, compounds 1c and 2c exhibit the highest electrophilicity indices, measuring 14.748 eV and 14.345 eV, respectively, among all examined inhibitor molecules. This suggests that they may act as the strongest nucleophiles in the context of this research. ΔN quantifies the extent of charge transfer interactions occurring at the interface between the surface and the corrosion inhibitors. When ΔN > 0, it indicates that charge moves from the inhibitors to the surface, whereas ΔN < 0 means that electrons are transferred from the surface to the inhibitor. As shown in Table 6, ΔN Cu (1 1 1) for 2d and 1d is equal to 0.384 and 0.327, respectively and ΔN Cu (1 1 0) for 2d and 1d inhibitors is equal to 0.172 and 0.118 and they have the highest charge transfer from the inhibitor to the surface and this leads to improved effectiveness in preventing corrosion73.

In conclusion, an assessment of frontier molecular orbitals, electronegativity, electrophilicity indices, and charge transfer parameters reveals that the triazine derivatives namely, 2c, 1c, 2d, and 1d, will exhibit enhanced adsorption and corrosion inhibition effectiveness on both Cu (1 1 1) and Cu (1 1 0). This observation aligns with their adsorption energies, which display the highest absolute values. Thus, these derivatives hold considerable promise for advancing surface protection strategies.

Mulliken charges

Table 7 summarizes the Mulliken charges of the molecules before their adsorption on the surface, which helps identify the atoms that are most likely to interact with the copper atoms74. Atoms that have a more negative Mulliken charge are great candidates for donating electrons to the unoccupied d-orbitals of surfaces75,76. As seen in Table 7, heteroatoms have the highest electron density and serve as active sites for inhibitors. These findings are corroborated by the data presented in Tables 4 and 5, which signifies that molecules are adsorbed from heteroatoms onto the surface. The Mulliken charge of molecules after adsorption has changed because of their nature to donate and give electrons, and Table 8 presents the variation in the Mulliken charge of the active sites, comparing values recorded before and following the adsorption process. A positive Δq suggests that electrons are transferred from the inhibitors to the surface, while a negative Δq indicates electron transfer from the surface to the inhibitor77. Most atoms exhibit a positive Δq, indicating their beneficial effect on surface protection. Notably, S1 demonstrates the most positive value, signifying the most effective electron transfer from this atom to the surface, except for 1b and 2b molecules, which do not adsorb to the surface from the S1 atom.

Fukui indices

Active sites of inhibitors for electrophilic or nucleophilic attack can be identified by utilizing Fukui indices78. Nucleophilic attacks and electrophilic attacks are associated with fk+ and fk−. A higher fk+ signifies a stronger inclination to donate electrons, while a higher fk− value suggests a stronger inclination to accept electrons79,80, and the reactivity increases with a higher Fukui index value, indicating a stronger tendency for electron gain or loss81,82. Calculated Fukui indices in gas and aqueous phases are displayed in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12. It is evident that, the highest fk+ and fk− are on the S, N, and O, which means these atoms have the highest tendency to donate and accept electrons. They are active donor-acceptor sites, and these results agree with the data in Table 8, which shows Mulliken charges after adsorption. As is obvious in Table 8, the Mulliken charge of some of the heteroatoms increases after adsorption, which means they are capable of accepting free electrons from the filled surface orbitals.

Comparison of gas and aqueous phases

Solvation energy refers to the change in energy that occurs when a molecule is transferred from the gas phase into a solvent. It considers the interactions that take place between the molecule and the solvent molecules, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions. In the gas phase, molecules are isolated and interact minimally with their surroundings. In contrast, the aqueous phase introduces significant solvation effects due to water’s high polarity and ability to form hydrogen bonds. These interactions can stabilize or destabilize molecular complexes depending on their structure and charge distribution.

In this study, all adsorption energy calculations referenced previously relate to the gas phase; however, given that corrosion occurs in the presence of water, additional calculations have been implemented to assess the effectiveness of inhibitor molecules in both gas and aqueous phases. To achieve this, the adsorption energy of the inhibitor molecules, when they are adsorbed perpendicularly and parallel to the surfaces of Cu (1 1 1) and Cu (1 1 0) in the aqueous phases, is listed in Table 9. As shown in Table 9, it is evident that the absolute adsorption energy value in the aqueous phase is reduced compared to the gas phase in Tables 4 and 5. For example, the perpendicular orientation of the 2c molecule on the Cu (1 1 0) surface shows a decrease in absolute adsorption energy from 114.04 kcal mol[- [1 to 77.17 kcal mol[- [1. This reduction indicates a significant solvation effect; however, the resulting energy remains sufficiently high to ensure effective corrosion inhibition on copper substrates.

Furthermore, the Fukui indices for the 2c molecule, due to its superior performance relative to other inhibitors when adsorbed on Cu (1 1 1) and Cu (1 1 0) surfaces, in both gas and aqueous phases, are presented in Table 10. In the gas phase, there is a direct interface between the copper surface and the reactants. However, in the aqueous phase, solvation effects can modulate electron density distribution, which may influence nucleophilic and electrophilic activities. However, this study indicates that changes in Fukui indices of inhibitors after adsorption on the surface are negligible in both phases. The minimal variation in Fukui indices observed between gas and aqueous environments may be attributed to the inherent chemical properties of the inhibitors and their interactions with the copper substrate. If the inhibitors possess strong adsorption characteristics that primarily govern their engagement with the surface, then the solvation effects encountered in the aqueous phase are unlikely to significantly impact their electron density profiles. It is noteworthy that S1 demonstrates consistently high reactivity across a range of conditions.

Comparing previous studies with this project

Extensive theoretical and experimental research has been undertaken to identify the most effective corrosion prevention strategies for copper surfaces. The calculated adsorption energy values of inhibitor molecules on the copper surface, as illustrated in Tables 4 and 5, were compared to those of previously reported inhibitors listed in Table 11. The results indicate that the studied molecules exhibited stronger adsorption, with absolute adsorption energy values exceeding those noted in other studies. The weaker adsorption energies reported in prior research highlight the superior performance of inhibitor molecules in this study in terms of interaction strength with the copper surface. These results underscore the potential of the molecules as an effective corrosion inhibitor, offering enhanced adsorption properties compared to existing alternatives.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive study utilizing a density functional theory (DFT) approach, the inhibition efficiency of several compounds, namely 4-amino-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(2 H)-one (designated as 1a) along with its tautomers (1b, 1c, and 1d), and 4-amino-6-methyl-3-thioxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,4-triazin-5(2 H)-one (denoted as 2a) and its corresponding tautomers (2b, 2c, and 2d) was investigated. The primary focus was on their effectiveness in safeguarding copper surfaces exhibiting distinct Miller indices, specifically the Cu(1 1 1) and Cu(1 1 0). In summary, it is confirmed that the interaction between the copper surfaces and the inhibitor molecules has been classified as chemisorption, based on the calculated bond lengths of Cu-N and Cu-S, which suggest the formation of covalent bonds between the inhibitor molecules and the copper surfaces, the adsorption energy of inhibitors on the copper surfaces, and Gibbs free energy of adsorption of inhibitor molecules on the Cu surfaces. The adsorption of inhibitors onto the surface occurs through heteroatoms, in line with calculated quantum chemical parameters such as Fukui indices and Mulliken charges. The Fukui indices demonstrate that heteroatoms act as the main active sites for both electron donation and acceptance. Furthermore, the positive Δq observed for these heteroatoms signifies their tendency to transfer electrons to the surface. Another quantum chemical parameter, ΔEgap, reveals that compounds 2c, 1c, 2d, and 1d exhibit the greatest inhibition efficiency. This finding is further corroborated by the adsorption energy trends, which align remarkably with the ΔEgap values. Ultimately, the analysis of the adsorption energies of molecules across various surface structures indicates a clear trend in efficiency, with Cu (1 1 0) outperforming Cu (1 1 1).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information fles].

References

Ferkous, H. et al. Tailored α-hydroxyphosphonate derivatives: green synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, DFT analysis, and high-efficiency corrosion protection for copper in acidic media. Sustainable Mater. Technol. 43, e01282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2025.e01282 (2025).

Shehata, O. S., Korshed, L. A. & Attia, A. Green corrosion Inhibitors, Past, Present, and future. In: (ed Aliofkhazraei, M.) Corrosion Inhibitors, Principles and Recent Applications. InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72753 (2018).

Kumar, A. Corrosion Inhibition of mild steel in hydrochloric acid by sodium Lauryl sulfate (SLS). J. Chem. 5 (2), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/574343 (2008).

Syam, S. M., Nady, H., Eid, S. & El-Katori, E. E. Experimental and theoretical assessment to investigate the impact of Gast reg drug on the copper corrosion control in an acidic environment. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84041-8 (2025).

Murira, C. M., Punckt, C., Schniepp, H. C., Khusid, B. & Aksay, I. A. Inhibition and promotion of copper corrosion by CTAB in a microreactor system. Langmuir 24 (24), 14269–14275. https://doi.org/10.1021/la8024759 (2008).

Barker, R., Hu, X., Neville, A. & Cushnaghan, S. Inhibition of Flow-Induced corrosion and Erosion-Corrosion for carbon steel pipe work from an offshore oil and gas facility. Corrosion 69 (2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.5006/0422 (2013).

Huang, Y. & Chen, J. The development of an Anti-corrosion wrapping tape and its corrosion protection effect evaluation on mild steel in marine Splash zone. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 7 (8), 7121–7127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1452-3981(23)15772-5 (2012).

Stack, M. M. Mapping tribo-corrosion processes in dry and in aqueous conditions: some new directions for the new millennium. Tribol. Int. 35 (10), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-679X(02)00059-2 (2002).

Zhang, R., Yu, X., Yang, Q., Cui, G. & Li, Z. The role of graphene in anti-corrosion coatings: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 294, 123613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123613 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Efficient protection of Mg alloy enabled by combination of a conventional anti-corrosion coating and a superamphiphobic coating. Chem. Eng. J. 390, 124562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.124562 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Effect of al content on wear and corrosion resistance of Ni-based alloy coatings by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 412, 126976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2021.126976 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. A novel alcrfemoti high-entropy alloy coating with a high corrosion-resistance in lead-bismuth eutectic alloy. Corros. Sci. 187, 109524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109524 (2021).

Salleh, S. Z. et al. Plant extracts as green corrosion inhibitor for ferrous metal alloys: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 304, 127030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127030 (2021).

Tanwer, S. & Shukla, S. K. Recent advances in the applicability of drugs as corrosion inhibitor on metal surface: A review. Curr. Res. Green. Sustainable Chem. 5, 100227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100227 (2022).

Jain, P., Patidar, B. & Bhawsar, J. Potential of nanoparticles as a corrosion inhibitor: A review. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 6 (2), 43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-020-00335-0 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Frontiers and advances in N-heterocycle compounds as corrosion inhibitors in acid medium: recent advances. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 321, 103031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2023.103031 (2023).

Wahba, A. M., Shoueir, K. & Fouda, A. E. A. S. Prediction and evaluation of pyrimidinones derivatives: DFT analysis, corrosion inhibition, and bioactivity studies. Results Surf. Interfaces. 18, 100448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsurfi.2025.100448 (2025).

Alamiery, A. A. Comprehensive evaluation of 5-imino-1,2,4-dithiazolidine-3-thione as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 10349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95104-9 (2025).

Quraishi, M. A., Chauhan, D. S. & Saji, V. S. Heterocyclic biomolecules as green corrosion inhibitors. J. Mol. Liq. 341, 117265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117265 (2021).

Hafizi, H., Najafi Chermahini, A., Mohammadnezhad, G. & Teimouri, A. A theoretical study on the interaction of amphetamine and single-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 329, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.12.126 (2015).

Zhou, Z., Zhou, Y., Huang, Y., Zhu, Q. & Tang, Y. Adsorption and dissociation of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole on Cu (1 1 1): A DFT study. Surf. Sci. 720, 122054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2022.122054 (2022).

Sheetal, Batra, R. et al. Advancement of corrosion inhibitor system through N-heterocyclic compounds: a review. Corros. Eng., Sci. Technol. 58 (1), 73–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478422X.2022.2137979 (2023).

Alqarni, N., El-Gammal, B., Fargaly, T. A., Mohammed, A. A. K. & Fawzy, A. Experimental and computational explorations for the inhibitive performances of synthesized green surfactants against the corrosion of copper in nitric acid. J. Mol. Struct. 1319, 139439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.139439 (2025).

Verma, C., Abdellattif, M. H., Alfantazi, A. & Quraishi, M. A. N-heterocycle compounds as aqueous phase corrosion inhibitors: A robust, effective and economic substitute. J. Mol. Liq. 340, 117211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117211 (2021).

Tan, L., Li, J. & Zeng, X. Revealing the correlation between molecular structure and corrosion Inhibition characteristics of N-Heterocycles in terms of substituent groups. Materials 16 (6), 2148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16062148 (2023).

Orash, N. & Najafi Chermahini, A. A DFT study on 2X- imidazole derivatives (X = OH, NH2, and SH) as corrosion inhibitors on Cu surfaces: tautomerism effect. Colloids Surf., A. 677, 132336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132336 (2023).

Anwer, K. E., Farag, A. A., Mohamed, E. A., Azmy, E. M. & Sayed, G. H. Corrosion Inhibition performance and computational studies of pyridine and Pyran derivatives for API X-65 steel in 6 M H2SO4. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 97, 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2021.03.016 (2021).

Mehta, R. K., Gupta, S. K. & Yadav, M. Studies on pyrimidine derivative as green corrosion inhibitor in acidic environment: electrochemical and computational approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (5), 108499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.108499 (2022).

Asiri, A. M., Baghlaf, A. O., Abdel-Rahman, R. M., Khan, S. A. & Ishaq, M. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of Ru(II) complexes of 1,2,4-Triazoles, 1,2,4-Triazines and pyrimidine derivatives. Asian J. Chem. 25 (14), 7779–7782. https://doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2013.14604 (2013).

Abdel-rahman, R. M. CHEMISTRY OF UNCONDENSED 1,2,4-TRIAZINES: PART II-SULFUR CONTAINING 5-OXo-1,2,4-TRIAZIN-3-yl MOIETY AN OVERVIEW. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 166 (1), 315–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426500008076552 (2000).

Zhao, Q. et al. Investigation of two triazine derivatives as potential eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for copper in artificial seawater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 18 (9), 100285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoes.2023.100285 (2023).

Obot, I. B., Kaya, S., Kaya, C. & Tüzün, B. Theoretical evaluation of triazine derivatives as steel corrosion inhibitors: DFT and Monte Carlo simulation approaches. Res. Chem. Intermed. 42 (5), 4963–4983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-015-2339-0 (2016).

El-Faham, A., Osman, S., Al-Lohedan, H. & El-Mahdy, G. Hydrazino-methoxy-1,3,5-triazine derivatives’ excellent corrosion organic inhibitors of steel in acidic chloride solution. Molecules 21 (6), 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21060714 (2016).

Mkhonto, P. P. et al. Design, synthesis and investigating the interaction of novel s-triazine collector with pyrite surface: A DFT-D3 + U and experimental studies. Surf. Interfaces. 38, 102820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.102820 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Synthesis, experimental and theoretical studies of triazine derivatives with surface activity as effective corrosion inhibitors for medium carbon steel in acid medium. J. Mol. Liq. 315, 113711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113711 (2020).

Paul, P. K. & Yadav, M. Investigation on corrosion Inhibition and adsorption mechanism of triazine-thiourea derivatives at mild steel / HCl solution interface: Electrochemical, XPS, DFT and Monte Carlo simulation approach. J. Electroanal. Chem. 877, 114599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.114599 (2020).

Wang, X., Xu, W. L., Liu, Z. Y. & Zhang, G. A. Unraveling the corrosion Inhibition mechanism of triazine derivatives for carbon steel: experimental and theoretical insights into interfacial adsorption. Corros. Sci. 220, 111288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111288 (2023).

Jang, H., Lee, J., Chun, Y. J. & Soh, S. Y. Corrosion of Cu in antifreeze solutions with Triazine- or Triazole-Type corrosion inhibitors for 3 weeks. Metals 12 (7), 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12071192 (2022).

Santos, B. A. M. C. et al. Molecular modeling for the investigation of UV absorbers for sunscreens: triazine and benzotriazole derivatives. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 356, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.12.036 (2018).

John, S. & Joseph, A. Effective Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in 1 M hydrochloric acid using substituted triazines: an experimental and theoretical study. RSC Adv. 2 (26), 9944. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ra20663c (2012).

John, S., Joseph, A., Sajini, T. & James Jose, A. Corrosion Inhibition properties of 1,2,4-Hetrocyclic systems: Electrochemical, theoretical and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Egypt. J. Petroleum. 26 (3), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2016.10.005 (2017).

Ebenso, E. E. et al. Theoretical studies of some sulphonamides as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 110 (14), 2614–2636. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.22430 (2010).

Castillo-Robles, J. M., De Freitas Martins, E., Ordejón, P. & Cole, I. Molecular modeling applied to corrosion inhibition: a critical review. Npj Mater. Degrad. 8 (1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00478-2 (2024).

Burke, K., Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Derivation of a generalized gradient approximation: the PW91 density functional. In: (eds Dobson, J. F., Vignale, G. & Das, M. P.) Electronic Density Functional Theory. Springer US; :81–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0316-7_7 (1998).

Price, A. J. A., Bryenton, K. R. & Johnson, E. R. Requirements for an accurate dispersion-corrected density functional. J. Chem. Phys. 154 (23), 230902. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0050993 (2021).

Guo, L., Dong, W. & Zhang, S. Theoretical challenges in Understanding the Inhibition mechanism of copper corrosion in acid media in the presence of three Triazole derivatives. RSC Adv. 4 (79), 41956–41967. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA04931D (2014).

Gomes, J. R. B. & Gomes, J. A. N. F. Adsorption of the formate species on copper surfaces: a DFT study. Surf. Sci. 432 (3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6028(99)00605-6 (1999).

Tafreshi, S. S., Roldan, A. & De Leeuw, N. H. Density functional theory study of the adsorption of hydrazine on the perfect and defective copper (100), (110), and (111) surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118 (45), 26103–26114. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp5078664 (2014).

Bourzi, H. et al. Understanding of anti-corrosive behavior of some tetrazole derivatives in acidic medium: adsorption on Cu (111) surface using quantum chemical calculations and Monte Carlo simulations. Surf. Sci. 702, 121692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2020.121692 (2020).

Tüzün, B. & Bhawsar, J. Quantum chemical study of Thiaozole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors based on density functional theory. Arab. J. Chem. 14 (2), 102927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102927 (2021).

Mamand, D. M. & Qadr, H. M. Density functional theory and computational simulation of the molecular structure on corrosion of carbon steel in acidic media of some amino acids. Russ J. Phys. Chem. 96 (10), 2155–2165. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036024422100193 (2022).

Singh, A., Ansari, R., Quraishi, K. A. & Lin, M. Y. Investigation of Corrosion Inhibitors Adsorption on Metals Using Density Functional Theory and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. In: Singh A, ed. Corrosion Inhibitors. IntechOpen; (2019). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.84126.

Karthikaiselvi, R. & Subhashini, S. Study of adsorption properties and Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in hydrochloric acid media by water soluble composite Poly (vinyl alcohol-omethoxy aniline). J. Association Arab. Universities Basic. Appl. Sci. 16 (1), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaubas.2013.06.002 (2014).

Oguzie, E. E., Li, Y., Wang, S. G. & Wang, F. Understanding corrosion Inhibition mechanisms—experimental and theoretical approach. RSC Adv. 1 (5), 866. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1ra00148e (2011).

Kumar, D., Jain, V. & Rai, B. Imidazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for copper: A DFT and reactive force field study. Corros. Sci. 171, 108724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108724 (2020).

Kokalj, A., Peljhan, S., Finšgar, M. & Milošev, I. What determines the Inhibition effectiveness of ATA, BTAH, and BTAOH corrosion inhibitors on copper? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (46), 16657–16668. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja107704y (2010).

Inglezakis, V. J. & Zorpas, A. A. Heat of adsorption, adsorption energy and activation energy in adsorption and ion exchange systems. Desalination Water Treat. 39 (1–3), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2012.3000 (2012).

Kokalj, A. Corrosion inhibitors: physisorbed or chemisorbed? Corros. Sci. 196, 109939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109939 (2022).

Yadav, M. & Kumar, S. Experimental, thermodynamic and quantum chemical studies on adsorption and corrosion Inhibition performance of synthesized pyridine derivatives on N80 steel in HCl solution. Surf. Interface Anal. 46 (4), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/sia.5408 (2014).

Pavithra, M. K., Venkatesha, T. V., Punith Kumar, M. K. & Tondan, H. C. Inhibition of mild steel corrosion by Rabeprazole sulfide. Corros. Sci. 60, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.04.003 (2012).

Obi-Egbedi, N. O. & Obot, I. B. Adsorption behavior and corrosion inhibitive potential of Xanthene on mild steel/sulphuric acid interface. Arab. J. Chem. 5 (1), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.08.004 (2012).

Bilgiç, S. & Şahin, M. The corrosion Inhibition of austenitic chromium–nickel steel in H2SO4 by 2-butyn-1-ol. Mater. Chem. Phys. 70 (3), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0254-0584(00)00534-4 (2001).

Chiter, F., Costa, D., Maurice, V. & Marcus, P. Adsorption of 2-mercaptobenzimidazole corrosion inhibitor on copper: DFT study on model oxidized interfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167 (16), 161506. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/abcd4f (2020).

Tan, B. et al. Insights into the Inhibition mechanism of three 5-phenyltetrazole derivatives for copper corrosion in sulfuric acid medium via experimental and DFT methods. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 102, 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2019.06.005 (2019).

Di Felice, R., Selloni, A. & Molinari, E. DFT study of cysteine adsorption on Au(111). J. Phys. Chem. B. 107 (5), 1151–1156. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0272421 (2003).

Kasprzhitskii, A. et al. Theoretical evaluation of the corrosion Inhibition performance of aliphatic dipeptides. New. J. Chem. 45 (7), 3610–3629. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NJ05281G (2021).

Mrani, S. A. et al. Experimental, theoretical and MC simulation investigations of the inhibitory efficiency of novel non-toxic pyridazine derivatives Inhibition on carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution. J. Mol. Liq. 382, 122043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122043 (2023).

Kumar, H. & Kumari, M. Experimental and theoretical investigation of 3,3′-diamino Dipropyl amine: highly efficient corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in 2 N HCl at normal and elevated temperatures. J. Mol. Struct. 1229, 129598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129598 (2021).

Deshmukh, H. S. et al. Synthesis, spectroscopic (IR and NMR), HOMO-LUMO, NLO, molecular docking and ADME study of (E)-2-(2-((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)hydrazineyl)-4-(4-nitrophenyl)thiazole). J. Mol. Struct. 1305, 137745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.137745 (2024).

Deshmukh, H. S., Adole, V. A., Mali, S. N. & Jagdale, B. S. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and computational insights of 2-(Aryl)benzo[d]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole-7-sulfonamide derivatives as potent antitubercular and antibacterial agents. BMC Chem. 19 (1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-025-01405-5 (2025).

Kokalj, A. Is the analysis of molecular electronic structure of corrosion inhibitors sufficient to predict the trend of their Inhibition performance. Electrochim. Acta. 56 (2), 745–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2010.09.065 (2010).

Liu, S. Dynamic behavior of chemical reactivity indices in density functional theory: A Bohn-Oppenheimer quantum molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Sci. 117 (5), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02708352 (2005).

Kumar, D., Jain, N., Jain, V. & Rai, B. Amino acids as copper corrosion inhibitors: A density functional theory approach. Appl. Surf. Sci. 514, 145905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145905 (2020).

Obot, I. B., Macdonald, D. D. & Gasem, Z. M. Density functional theory (DFT) as a powerful tool for designing new organic corrosion inhibitors. Part 1: an overview. Corros. Sci. 99, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.01.037 (2015).

Murmu, M., Saha SKr, Bhaumick, P., Murmu, N. C., Hirani, H. & Banerjee, P. Corrosion Inhibition property of azomethine functionalized Triazole derivatives in 1 mol L – 1 HCl medium for mild steel: experimental and theoretical exploration. J. Mol. Liq. 313, 113508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113508 (2020).

Abdelsalam, M. M. et al. Green synthesis, electrochemical, and DFT studies on the corrosion Inhibition of steel by some novel Triazole schiff base derivatives in hydrochloric acid solution. Arab. J. Chem. 15 (1), 103491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103491 (2022).

Esmaeilzadeh Khabazi, M. & Najafi Chermahini, A. DFT study on corrosion Inhibition by tetrazole derivatives: investigation of the substitution effect. ACS Omega. 8 (11), 9978–9994. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07185 (2023).

Li, X., Deng, S., Lin, T., Xie, X. & Xu, X. Inhibition action of Triazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide on cold rolled steel corrosion in three chlorinated acetic acids. J. Mol. Liq. 274, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.10.066 (2019).

Hrimla, M. et al. Corrosion Inhibition performance of a structurally well-defined 1,2,3-triazole derivative on mild steel-hydrochloric acid interface. J. Mol. Struct. 1231, 129895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.129895 (2021).

Mi, H., Xiao, G. & Chen, X. Theoretical evaluation of corrosion Inhibition performance of three antipyrine compounds. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1072, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2015.08.023 (2015).

Rahimi, S., Najafi Chermahini, A., Farrokhpour, H. & Hajipour, A. R. Corrosion Inhibition of copper by Oxalohydrazide and its methylated derivatives: A theoretical study. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 138, 109038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2025.109038 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. DFT study of imidazoles adsorption on the grain boundary of Cu (100) surface. Corros. Sci. 137, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.03.009 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Insights into Triazole derivatives as potential corrosion inhibitors in CMP process: experimental evaluation and theoretical analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 602, 154165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.154165 (2022).

Sun, S. et al. Density functional theory study of imidazole, benzimidazole and 2-mercaptobenzimidazole adsorption onto clean Cu(111) surface. Corros. Sci. 63, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.05.024 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Corrosion Inhibition mechanisms of Triazole derivatives on copper chemical mechanical polishing: combined experiment and DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 654, 159469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.159469 (2024).

Khaled, K. F., Fadl-Allah, S. A. & Hammouti, B. Some benzotriazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for copper in acidic medium: experimental and quantum chemical molecular dynamics approach. Mater. Chem. Phys. 117 (1), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2009.05.043 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to convey their appreciation to the Isfahan University of Technology, particularly the Faculty of Chemistry, for their invaluable support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J.: was responsible for manuscript preparation, performing calculations, formal analysis, preparation of figures, and conceptualization. A.N.C.: as supervisor is responsible for project administration, project funding and validation of data. H.F.: Conceptualization; resources. M.M.M.S.: providing editing assistance, conceptualization; and resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jafarzadegan, Z., Najafi Chermahini, A., Farrokhpour, H. et al. A theoretical study on the corrosion inhibition of Cu surfaces using 4-amino-3-thioxo-6-methyl-1,2,4-triazine-5-one and its derivatives. Sci Rep 15, 37481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21527-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21527-z