Abstract

Debris flow is a geological process primarily triggered by factors such as rainfall or earthquakes, characterized by strong abruptness and significant destructive force. It poses a severe threat to human life and property. Exploring its formation, initiation mechanisms, and effective early warning measures is a reliable approach for disaster prevention and mitigation in mountainous regions. An indoor simulation experiment system was designed to study the initiation process of coarse-grained gravel-type debris flow under different particle sizes and slope angles. The interplay among the mean particle size, water flow, the slope angle of the material source, and the onset of debris flow has been elucidated to assess the dynamic changes in various characteristic parameters. This analysis formed initiation criteria specific to gravel-type debris flow. The combined particle size and slope angle of the material source were positively correlated with the water power required for debris flow initiation. A fitting relationship between the unit width flow rate, mean particle size, and slope angle was established. The humidity, seepage pressure, soil pressure, slope angle, and vibratory shock acceleration of the material source had characteristics such as mutability or asynchronism during the formation and initiation of debris flow. However, humidity and seepage pressure were not used as initiation criteria. The initiation criteria for debris flow included changes in characteristic parameters (e.g., soil pressure, slope angle, and vibration acceleration). The research findings can provide a reference for the characteristic identification and initiation early warning of similar types of debris flows, enhancing the safety management level of debris flow disasters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Debris flow is a rapid and destructive geological phenomenon involving the downslope movement of a mixture of water, sediment, and rock along mountainous valleys or slopes. It is characterized by sudden occurrence, high velocity, complex triggering mechanisms, and substantial destructive capacity. Under the influence of earthquakes, intense rainfall, rapid snowmelt, and human engineering activities1, the frequency and intensity of debris flow events have shown an increasing trend, leading to escalating impacts on socio-economic development and ecological stability2,3,4. As awareness of debris flow hazards continues to grow, studies on initiation mechanisms, scale evolution, early identification, monitoring, and early warning have gained increasing importance for disaster prevention and risk mitigation in mountainous towns and major infrastructure zones5.

Debris flow is a two-phase solid-liquid mixture flow consisting of components such as clay, boulders, fine sediment, and water6. Du et al.7 proposed that debris flow exhibits two essential characteristics: first, the mass in motion must display at least a solid-liquid phase or pseudomono phase; second, the movement of the mass relies on both solid and fluid forces. Takahashi8,9 classified the mechanical causes of debris flow initiation into three categories: (1) erosion of debris on the gully bed by water, leading to an increased solid concentration in surface runoff until the flow transitions into debris flow; (2) transformation of a landslide mass into debris flow during movement due to internal water storage or external water supply; and (3) the collapse of a debris flow dam. The initiation of debris flow is primarily influenced by water sources, topography, the physical properties of loose material, and the corresponding stress state. Takahashi constructed a model of landslide transformation into debris flow, as shown in Fig. 1, detailing the development of liquefaction layers and debris flow under the influence of water, thereby elucidating the formation mechanism of debris flows. Furthermore, a numerical model was developed based on this theoretical framework10. Takahashi11 calculated that the critical slope angle for debris flow occurrence is approximately 14.5° under mechanical equilibrium. Some researchers have observed that rainfall intensities as low as 10 mm/h may also trigger debris flow12. Hence, the properties of materials and their stress states are critical factors affecting the initiation mechanism of landslides. The particle composition of solid materials significantly impacts the porosity and permeability of soil layers. As the fine particle content increases, the permeability of the soil decreases, resulting in a notable reduction in effective stress. This condition allows the soil layer to reach a critical state with relatively low rainfall13,14. Iverson et al. further found that vibration caused by seismic activity or material movement on slopes reduces the cohesion of the soil, facilitating the occurrence of debris flow. In summary, rainfall intensity, slope angle, and material composition are key factors influencing the initiation of debris flow. The impact of vibrations on the initiation mechanism of debris flow also warrants further investigation.

Some researchers have explored the formation and initiation mechanism of debris flow15,16,17. Wu et al.18 analyzed the formation conditions of debris flow based on the topographic condition, water source condition, and soil source condition of the Jiangjiagou watershed. Chen19 described the formation process of storm debris flow by the artificial rainfall test of the debris flow source of Jiangjiagou. Rainfall causes changes in the water content, structure, and composition of soil. Then, changes in soil strength affect slope stability. Subsequently, slope debris flow occurs, which forms valley debris flow. Debris flow initiation is a crucial step in the whole process of occurrence, development, and disaster formation. The initiation mode is the core issue of debris flow research and the theoretical basis of early warning and disaster prevention. Iverson et al.20 conducted multiple large-scale experiments using the USGS flume, providing deep insights into the mechanisms by which soil particle size, porosity, and other factors affect debris flows. Hiroshi21 considered debris flow as a rapid mixing motion of large-scale solid particles and water. The mechanical behaviors of debris flow in the initiation, flow, and deposition are explored to quantitatively explain the main characteristics of debris flow by a simple idealized theory. Cui et al.22 studied the whole process of debris flow initiation to propose the mutation pattern theory. Liu et al.23 divided the evolution of debris flow into three stages: the antecedent rainfall, the accelerated initiation, and the long-distance movement stage.

Okuda24, Itakura25, and Suwa26 monitored the sound of debris flow by microphones and seismic instruments. Thus, debris flow initiation is determined in the high-frequency basins of debris flow. Du et al.7 summarized three basic methods for determining debris flow initiation: the safety factor method27, the rainfall indicator method, and the comprehensive assessment method. Inaba et al.28 proposed a method for monitoring the surface vector velocity of debris flow based on the spatiotemporal derivative space method. Arattano et al.29 measured the surface velocity of debris flow using oblique photography based on a method of directly calculating the mapping between points in a 2D image and points in a 3D space. He et al.30 derived the critical conditions of the sediment rolling initiation mode. The critical stress coefficient in the corresponding state is taken as the initiation standard for sediment particles. Muste et al.31 applied large-scale particle image velocimetry (LSPIV) to three water conservancy projects based on the basic principles of traditional particle image velocimetry (PIV), which verifies the feasibility of LSPIV in large-scale objects. Scheidl et al.32 demonstrated the effectiveness of using a small-scale modeling approach to study mud debris flows. Shu et al.33 initiated their research from the perspective of force exerted by source particles. The ratio of the shear force of water flow to the critical shear force required for particle initiation is utilized as the initiation parameter for debris flow. This parameter is used to establish a discriminant for the initiation of heterogeneous debris flow. Hu34 observed the whole process of debris flow initiation by numerical simulation. The particle motion speed and displacement of the landslide accumulation body increase when the moisture content exceeds the critical value. The loose debris material accelerates, which causes the chain destruction of landslide and debris flow.

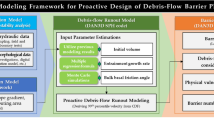

Substantial progress has been made in understanding the initiation mechanisms of debris flows and in the development of predictive models, especially for mud-type and sandy-type debris flows35,36. However, research on gravel-type debris flows, particularly in terms of experimental investigation and early warning (especially pre-warning), remains limited. Numerical simulations have been widely applied, but experimental validation is still relatively scarce. To address this research gap, an indoor debris flow simulation apparatus was independently developed in this study, aiming to replicate gravel-type debris flow scenarios in mountainous regions. Dynamic monitoring data and Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) techniques were employed to capture the variation patterns of key dynamic parameters before and after debris flow initiation. By analyzing the relationship between relevant indicators and triggering factors, a fitting linkage was established to support early identification and pre-warning. This discovery aims to provide a reference for early warning, prediction, efficient prevention, and mitigation strategies against debris flow.

Method

Research area

The Xishan region of Beijing is located in the southwestern part of the city, encompassing Fangshan District, Mentougou District, and the foothill areas, with a total area of approximately 2,954 km². Major roads in the region include National Highways 107 and 108, as well as the Beijing-Shijiazhuang Expressway. The region contains 197 potential debris flow hazard channels, with rainfall concentrated between late July and early August, accounting for 60% of the annual precipitation. The debris flow source areas predominantly consist of gravel, with a small amount of soil. The slope angles of the 197 potential debris flow gullies range from 15° to 45°. To ensure the safety of the mountainous areas of Beijing, it is essential to conduct early identification, monitoring, and early warning research on debris flows.

Experimental design

A test device providing different hydrodynamics, slope drop ratios, and particle size combinations was built indoors in the experiment. The changes in relevant source parameters were collected in real time by multiple sensing devices to determine the fitting relationship and early warning criteria between different factors (e.g., the rock-soil particle size of the debris flow source, groove water flow, and the channel slope) and debris flow initiation. The experimental system consisted of five parts.

(1) The water supply system provided water flow of different magnitudes;

(2) The experiment table provided a catchment area, adjustable source area, and circulation area;

(3) Material source provided different particle size combinations;

(4) The sensing system collected the relevant source characteristics;

(5) The acquisition system automatically collected data from the sensing system and saved them to the computer hard disk as the experiment progressed.

It should be noted that, due to laboratory constraints, it was not feasible to install pumps with larger flow capacities. Moreover, as debris flow water sources are typically dispersed rather than concentrated, multiple water pipes had to be arranged, which further limited both the achievable flow rate and the scale of the experimental design.

System device

Hydrodynamic conditions are significant external driving factors in the formation of debris flow. Although these conditions are not intrinsic parameters of debris flow, the effects of water, such as wetting, infiltration, and thrust on the material source, play a crucial role in determining the initiation of debris flow. Therefore, hydrodynamic conditions played a key role in the initiation experiment of debris flow in this study. A larger mean particle size in the grain size composition of the material source required greater hydrodynamic force for flow initiation. Submersible pumps, adjustable valves, porous water pipes, and customized water storage tanks were used to achieve water flow of different sizes. Two submersible pumps with flow rates of 65 and 40 m³/h and corresponding diameters of 100 and 80 mm are strategically placed in the reservoir, which is continuously supplied with water from external sources. This arrangement is designed to fulfill the hydrodynamic requirements for debris flow initiation. The flanges are welded with the water pump outlets to form two water supply lines. Water flow is controlled by adjusting valves 1 and 2. The values of two flow meters (where the flow range is 30–160 and 20–120 m3/h) are collected by computer in real time. The parameters of the water pumps and flow meters are provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Five pipes with equal spacing and diameter (50 mm) are formed at the rear of the water supply pipeline and welded behind the customized water storage tank. The customized water storage tank of 1.8 × 1.6 × 0.6 m is made of stainless steel. A slope baffle is set at the outlet of the water storage tank to ensure uniform flow output at a certain rate. The designed water supply system provides hydraulic power as illustrated in Fig. 2, with a total flow rate range of 20–130 m³/h.

The water storage tank is customized with the galvanized sheet to simulate the water source of the cofferdam for debris flow initiation (Fig. 3). The outlet holes are composed of equidistant circular holes with a diameter of 50 mm. An acrylic inclined plate with a slope angle of 20° is placed in the water tank. Water gathers in a certain amount and rushes out of the tank evenly at a certain flow rate after passing through the outlet hole. The experiment table adopts a three-stage sink of 6.0 × 2.0 × 0.6 m with an adjustable slope. It is divided into the catchment area, the source area, and the circulation area (Fig. 4).

The catchment area is the first tank where the customized water storage tank is placed, which can be lifted vertically with the hydraulic adjustment cylinder. The second tank where the material source area is located changes the slope from 0 to 45° with a hydraulic regulating cylinder. The horizontal railings and steel wire grids are laid at equal intervals while the coal cinder is paved as the bottom layer. The third tank where the circulation area is located moves back and forth with the hydraulic regulating cylinder.

Material source and the sensing and acquisition system

The rock-soil bodies of debris flow gully (e.g., gravel and a small amount of soil) are selected as the debris source. The material sources with different mean particle sizes are formed and accumulated in the source area of the experiment table after screening and mixing (Fig. 5). The sensing system consists of Micro Electromechanical Systems (MEMS) sensors, hygrometers, soil pressure gauges, osmometers, laser rangefinders, and cameras (Fig. 6). The hygrometers, soil pressure gauges, and osmometers are located at the bottom of the source. The MEMS sensors are inserted vertically into the upper material source in the same direction. Besides, a MEMS sensor is bonded to the outer wall of the experiment table.

The debris flow material source is stacked in a trapezoidal shape, measuring 2000 mm in length, 200 mm in height, 800 mm in width at the bottom, and 400 mm in width at the top. The top is positioned 50 mm above the bottom, and the bottom is 350 mm below the top. The sensors are arranged in a longitudinal and transverse array along the material source slope. The osmotic pressure gauges are arranged in two lateral rows, with five units in total: three units on the upper side, spaced 500 mm apart, and two units on the lower side, with 650 mm between the two on each side and 700 mm in the middle. Seven hygrometers are installed, with three units located on the upper side in the same position as the osmotic pressure gauges, and the remaining three units placed at equal intervals of 500 mm below, with one additional hygrometer installed adjacent to the right osmotic pressure gauge. Two soil pressure gauges are placed along the center of the slope, immediately adjacent to the hygrometers. Six MEMS sensors are arranged in two lateral rows, with three units placed above and three below, spaced 500 mm apart. A detailed layout of the sensor arrangement is shown in Fig. 5. The MEMS sensors, developed by the research team, can collect real-time vibration data at a frequency of 1000 Hz. The main monitoring parameters include tilt angle, tilt direction, horizontal tilt angles (X/Y/Z), and vibrational shock acceleration. The device photo is shown in Fig. 7, and the main technical parameters are listed in Table 3. It should be noted that the osmometer used is actually a pore water pressure sensor, which measures the water pressure between gravel particles and reflects the internal water accumulation and the infiltration process of the water flow within the material source.

The main technical parameters of other monitoring devices, including soil pressure gauges, osmotic pressure gauges, hygrometers, and laser distance meters, are shown in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7, respectively.

Two video cameras are positioned facing the debris flow material slope, located 5 m directly in front and 2 m diagonally above the slope, respectively, to monitor the surface deformation during the entire initiation process of the debris flow. To facilitate postprocessing of the video monitoring data, artificial light sources are used for supplemental illumination, and a calibration board is set up to provide a measurement standard for subsequent image analysis. Additionally, two laser distance meters are installed below the front-facing camera to monitor the movement characteristics of the debris flow material source. The main technical parameters of the cameras are listed in Table 8.

The sensor equipment types include RS485, vibration string, and analog quantity in the test. The automatic acquisition command is compiled and issued by Python and stored in Excel tables for the convenience of subsequent data analysis. Besides, the vibrating string type is equipped with acquisition module hardware for data conversion.

Experimental process and results

Experimental process

Gravel from the Xishan region was used as the material source for debris flow. Six particle size ranges were selected: ≤15 mm, 15–25 mm, 25–35 mm, 35–45 mm, 45–55 mm, and ≥ 55 mm. These were mixed in specific proportions to form four particle size combinations: combination 1, combination 2, combination 3, and combination 4. Statistical analyses of debris flow disasters in the Beijing area over recent decades revealed that the longitudinal slope angle of initiation gully beds was generally greater than 13°, with a minimum of approximately 10°. Considering experimental validity, four channel slope gradients of 12°, 16°, 20°, and 24° were selected for this study.

Four material sources with different mean particle sizes were prepared through indoor screening and proportional mixing. The mass percentages of various particle sizes were determined based on a curve resembling a normal distribution (Fig. 8). The specific mass percentage values for each particle size are listed in Table 9. Ultimately, four material sources with mean particle sizes of 17.75 mm, 25.25 mm, 33.75 mm, and 42.25 mm were formed. Based on the four slope gradients and the four mean particle size combinations, an orthogonal experimental design was implemented, resulting in 16 test groups. Details of the groupings are shown in Table 10. Then, water impounding could be initiated for the simulation test of debris flow initiation (Fig. 9).

The material source was weighed, mixed, and stacked, and then the sensor system was buried. The data acquisition of each sensor was debugged and zeroed, followed by the initiation of water impounding for the debris flow initiation simulation experiment. Three data acquisition points were set up in the experimental site. Point 1 mainly collected real-time monitoring data from MEMS sensors, piezometers, hygrometers, and soil pressure gauges; Point 2 mainly collected video data and laser rangefinder data; and Point 3 primarily collected data from two flowmeters and controlled the water supply switch, as shown in Fig. 9. The experiment began with the material source forming a stable slope body, with an initial water flow of 0. The water flow was gradually increased to enhance the water power until the material source gravel visibly slid and was eroded to the collection area, at which point the experiment was stopped.

In the experiment, Large-Scale Particle Image Velocimetry (LSPIV) was employed to measure the surface velocity of debris flow. LSPIV was first implemented in Japan and has been widely adopted due to its capability to accurately measure large-scale flow velocities using conventional video systems, making it particularly suitable for laboratory applications. This technique is based on image processing technology, which captures objects on the water surface and calculates surface velocity after undergoing image orthorectification and other processing steps31. The movement velocity of the source material can be calculated by capturing the source material itself as the target in the images.

Experimental results

Gravel particle size combination 1 is taken as the material source of debris flow at the slope angle of 24°. The material source makes a uniform motion at 16:39:03 based on the video data. This moment can be set as initiation time. Figure 10 shows the pre-start and post-start states.

Debris flow initiation refers to a critical state where multiple solid particles start to move from rest. The motion process exhibits the transition from translational motion to layered motion. Translational motion refers to solid particles transitioning from a stationary state into movement, exhibiting collective sliding either downward or along the slope as a whole. Layered motion refers to the movement of solid particles being more stratified, with particles sliding along the ground surface or slope and displaying characteristics of a velocity gradient during movement. The particles of layered motion have the largest surface motion speed. Therefore, it is a more scientific method to determine whether debris flow is initiated by the changing characteristics of the surface motion speed37. Preliminary experimental research shows that the surface motion speed changes from the accelerated motion stage to the uniform motion stage when debris flow starts to move from rest. Video data are processed by LSPIV to obtain the surface motion characteristics and the average surface motion rate, which determines the initiation time of the material source in this test38. The initiation time of debris flow occurs when the average motion speed on the surface of the debris source shifts from the acceleration stage to the uniform motion stage (Fig. 11).

Figure 12 shows the physical characteristic parameters of the material source initiation of debris flow in the test. The flow rate required for material source initiation is about 40.866 m3/h under an average particle size of 17.75 mm and a slope angle of 24° (Fig. 12(a)). The count value of humidity increases immediately when the water source is turned on (Fig. 12(b)). The other positions remain unchanged except for a large fluctuation at position 2. The seepage pressure value continuously increases, with a maximum of 0.11 MPa and a minimum of 0.02 MPa (Fig. 12(c)). The soil pressure value first decreases and then increases after material source initiation, with an amplitude of 0.005 MPa. The seepage pressure value gradually increases with the ascending osmometer numbers. In Fig. 5, the osmometer numbers in the first row (near the catchment area) are 1, 2, and 3 from left to right, while in the second row (in the origin catchment area), the osmometer numbers are 4 and 5 from left to right. Based on the source area destruction process shown in Fig. 10, the following conclusions can be drawn: (1) regions subjected to significant water erosion correspond to higher seepage pressure values; (2) the seepage pressure values at the front of the slope are higher than those at the rear, indicating that the debris flow initiated from the front part of the slope. In Fig. 12(d), monitoring points 1, 3, and 6 were the first to show changes in slope angle, with values ranging from 60° to 100°. Monitoring points 2 and 5 initially had a slope angle of 0°, but around the 6-second mark, the slope angles of points 2 and 5 rapidly increased to 99.9° and 73.3°, respectively. The slope angle at monitoring point 4 remained close to 0° until 71 s, after which it increased rapidly to 83.3°. Based on a comparison with the destruction process in the source area (Fig. 10), the following conclusions can be made: (1) regions subjected to significant water flow influence were the first to experience changes in slope angle; (2) as water mainly flowed along the right side of the slope, the slope angle at monitoring point 6 exhibited the largest change, with the highest final inclination value; (3) the central part of the rear slope demonstrated better stability than the left and right sides, not being immediately affected by the initial water flow; (4) since only a small amount of water passed through monitoring point 4, the slope angle at this point remained near 0° for a long time.

Figure 13 shows the time-domain and time-frequency curves of Y-axis vibration acceleration at monitoring points 2 and 7. The maximum acceleration at point 2 is 3,000 mg (3 g), which is significantly higher than 200 mg at point 7. The time-frequency curve slightly changes at point 2 and remains unchanged at point 7. In Figs. 11 and 13, the initiation time of the debris flow is determined from the flow velocity and vibration acceleration, respectively. In Fig. 11, during the acceleration motion phase, the solid particles exhibit collective movement with relatively stable interactions between particles, which is reflected in Fig. 13 by a stable vibration acceleration. As the curve in Fig. 11 enters the uniform motion phase, solid particles begin to slide along the slope and show characteristics of a velocity gradient. At this point, the interactions between the solid particles intensify, which is reflected in Fig. 13 by the onset of chaotic and rapid fluctuations in the vibration acceleration.

Fitting relationship and criteria of debris flow initiation

Fitting relationship of the material source initiation

The material sources of different particle sizes are mixed in a certain proportion to adjust the sliding slope. Water power required for the material source initiation is determined by constantly changing water flow to obtain the fitting relationship. A total of 16 sets of orthogonal test results are achieved, including 4 particle size combinations and 4 slope angles. Water flow for initiation is significantly different under different working conditions (Table 11).

Figure 14 shows the relationship between initiated water flow under the same particle size and different slope angles for gravel-type debris flow according to Table 11. Initiated water flow does not necessarily decrease with the increased slope angle under the same particle size combination. For example, initiated water flow is 72.2612 m3/h for a gravel source with particle size combination 2 when the slope angle is 12°. Initiated water flow is 78.9769 m3/h when the slope angle is 24°. Required water flow increases. Figure 15 shows the relationship curve of initiated water flow under different particle size combinations and the same slope angle. The larger mean particle size formed by the particle size combination of the material source indicates greater initiated water flow (water power) at the same slope angle.

Figure 16 shows the 2D initiation diagram of debris flow. The material source is provided with water power at a depth of H under water flow. The accumulated material source with the thickness of h initiates when the resistance of the source’s layer motion is exceeded under water power and the driving shear stress from self-gravity.

\(\theta\) is slope angle. Shear stress \(\tau\) driving the motion of the material can be expressed as Eq. (1) under stable flow. Layered motion resistance \(\tau_s\) is expressed as Eq. (2).

>

where SV is the average solid volume fraction of the material source. \({\gamma _S}\) is the unit weight of solid material (kN/m³). \(\gamma\) is the unit weight of water. tan \(\alpha\) is the internal friction coefficient of the particles. \(\tau_L\) is the critical shear resistance, determined primarily by internal friction and inter-particle contact forces within the unsaturated granular mixture.

Debris flow can be initiated when \(\tau \geq{\tau _L}\) (i.e., the driving shear stress exceeds the motion resistance). The condition for debris flow initiation is obtained according to Eqs. (1)–(2).

The size distribution and types of gravel particles are selected in the test. The bulk weight is 1.5 t/m3, and the friction coefficient of particles is 0.6. The fitting relationships among the gravel source particle size, type, slope angle, and debris flow initiation are obtained according to Eq. (3).

Equation (4) presents the initiation condition for debris flow under the same particle size and different slopes.

where A and k are empirical coefficients obtained from experimental fitting, representing the influence of permeability, slope, geological structure, and frictional resistance on water flow.

Equation (5) shows the initiation condition for debris flow under the same slope and different particle sizes.

where B is the width of slope. m is the mass of soil material source.

Equation (3) and Eq. (4) were derived from the fitting of the experimental results. The fitting relationship among single-width water flow q of debris flow, the mean particle size of the material source, and the surface (groove) slope can be fitted as Eq. (6) according to Refs15,16,17. Figure 17 shows the fitting diagram. Equation (6), derived from an orthogonal experiment, systematically investigates the interrelationship among particle size, slope angle, and hydrodynamic conditions. Based on 16 experimental groups with different combinations of particle size and slope angle, the effects of these factors on the water flow rate required for initiation were quantitatively analyzed, and a fitting equation was established between the unit-width flow rate, mean particle size, and slope angle. This relationship clearly reveals the coupling mechanism among the three parameters, providing both data support and a theoretical basis for further understanding the initiation characteristics of debris flows under different source material conditions.

Evolution law of physical characteristic parameters of debris flow initiation

The osmometer, soil pressure meter, and hygrometer are used to monitor the relevant physical characteristic parameters of the material source of debris flow in real time. The example is taken with a mean particle size of 17.75 mm and a slope angle of 24°. The parameters before and after initiation (Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15) are enlarged to obtain the detailed change curves of characteristic parameters including humidity, seepage pressure, and soil pressure (Figs. 12 and 18(c)). The seepage pressure at each point gradually increases from the minimum of 0.02 MPa to the maximum of 0.11 MPa.

The value of osmometer 3 remains unchanged when debris flow is initiated. The point is the initial instability position combined with video image data. The hygrometer reflects the water coverage condition around the material source. Debris flow is easily caused when the material source is eroded by water for some time. The force of the material source on the bottom changes with water power. The value of the soil pressure meter significantly decreases, with an amplitude of 0.005 MPa. Different points of the material source exhibit different deformations during the overall initiation process (Fig. 10). The first position subjected to water power firstly changes at a certain slope angle. However, the slope angles of the relevant points change concentratedly with the overall motion of the material source.

Particle materials typically exhibit various characteristics (e.g., dilatancy, separation) that significantly influence the movement of debris flows39. Yang et al.40 found that the particle composition has a considerable impact on the properties of debris flows, and when particle size distribution is uneven, higher pore pressures are more likely to occur. Additionally, there exists a feedback mechanism between the movement of the debris flow and the overlying coarse particle layer. Due to limitations in experimental equipment, this study did not analyze the motion characteristics of solid particles and the interaction mechanisms from a micromechanical perspective. Li et al.41 conducted a study on the influencing factors and dynamic development processes of debris flows based on numerical simulations. Dai et al.42 investigated the dynamic characteristics of debris flows, including flow velocity, runout distance, and energy, using numerical simulations. A combination of physical experiments and numerical simulations for further analysis of the initiation characteristics of debris flows should be a key focus for future research.

Evolution law of the dynamic characteristic parameters during debris flow initiation

The stress state of the internal structure of the debris flow material source changes with increased water power. The motion is generated to change the vibration characteristics (i.e., dynamic characteristics) when the driving force of the material source exceeds the resistance of particles. Therefore, the kinetic indicators reflect the changes in stability during the initiation process. The vibratory-impact acceleration intuitively reflects the vibration characteristics of the material source in the time domain according to the kinetic theory. The power spectral density can reflect the corresponding probability under a horizontal vibration response in the frequency domain43. The vibration observed during the debris flow process is induced by energy dissipation, primarily resulting from the impact of solid materials on the channel bed or the interactions among particles. Studies have shown that different particle compositions and motion states (e.g., sliding, collision, and rolling) generate distinct vibration frequency distributions and energy dissipation patterns, which reflect the dynamic evolution of the material source during the initiation process44. The energy ratio of the corresponding frequency range can be obtained to reflect the vibration characteristics of the material source. The vibratory-impact acceleration, vibration frequency, frequency band energy, and center-of-gravity frequency are taken as the dynamic characteristic parameters to discuss evolution law and the indicator criterion for the early warning of debris flow based on the preliminary results.

The result under a mean particle size of 17.75 mm and a slope angle of 20° is taken as an example. Figure 19 shows the changes in the acceleration and slope angle during the material source initiation. The impact acceleration changes greatly in the X-, Y-, and Z-axes before material source initiation. Point 6 begins to slide at first according to the video. The corresponding acceleration reaches 2,000 mg on the X-axis. Then, motion occurs at point 3, where the amplitude of the corresponding impact acceleration reaches 15,000 mg. The impact acceleration at point 2 reaches 2,000 mg. A sudden increase in the acceleration occurs on the Y- and Z-axes. Therefore, the change in the stable state of the material source near the point can be preliminarily judged by monitoring the change in the vibratory-impact acceleration at the point.

Figure 20 shows the Y-axis vibration data at point 2. The frequency with the highest energy is the vibration frequency in the time-frequency domain. The frequency domain curve can be obtained by selecting the time domain curve of a certain distance for a fast Fourier transform. Then, the peak is selected to determine the main frequency.

Figure 21 shows the main frequency characteristics and stage division of the material source. The main vibration frequency of the 19th group is between 6 and 7 Hz before initiation. Nevertheless, the frequency experiences a rapid decline after 150 s, ultimately coming to 0. Debris flow is divided into the stabilization and initiation stages according to the changing characteristics. The main frequency remains unchanged within a certain range in the stabilization stage. Debris flow enters the initiation stage when the main frequency drops sharply to a minimum. Whether debris flow initiates is determined based on the changes in the main frequency characteristics (Table 12).

Figure 22 shows the change curves of the third frequency band energy and center-of-gravity frequency based on the spectral density and monitored time domain data at point 2. The third frequency band energy ranges from 0.15 to 0.2 with increased water power in the stabilization stage of the material source. The center-of-gravity frequency is between 25 and 40 Hz. However, the third frequency band energy and center-of-gravity frequency plummet below 0.05 and 5 Hz when debris flow initiates at 150 s. Low-frequency band energy is suddenly released to sharply reduce the proportion of the third frequency-band energy due to the loosening of the overall structure during the initiation process of the material source. Meanwhile, the sensor deviates from the center-of-gravity position to a greater extent, and its center-of-gravity frequency value drops sharply.

Early warning criteria of debris flow initiation

The soil pressure, the slope angle of the material source, and the vibratory impact acceleration have the mutation or asynchronism characteristics before and after the material source initiation of debris flow according to the 16 groups of gravel-type test results (Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15).

(1) The material source with coarse particles is surrounded by water before and after material source initiation. Besides, the osmotic pressure continues to increase. Debris flow is easily caused when the hygrometer is maintained near 100%. Larger osmotic pressure indicates a higher probability of debris flow initiation. However, it cannot be used as a deterministic basis for judging debris flow initiation;

(2) The soil pressure meter is affected by the gravity of the material source and water power during material source initiation. The soil pressure drops abruptly, showing an exponential downward trend. It slowly rises to a certain extent in the initial stage after initiation. Therefore, the change characteristics of the soil pressure value can be used as a deterministic judgment basis for debris flow initiation;

(3) The slope angle of each point of the material source varies from 0 to 90° during material source initiation. The change of each point is mutant, within a few seconds. The mutability and asynchronism of slope angle change at multiple points can be used as the early warning criteria before debris flow initiation;

(4) The amplitudes of vibration impact acceleration at different monitoring points change greatly during material source initiation. The vibration acceleration reaches 2,000 mg in the areas where surface deformation is generated or nearby. The vibration acceleration also reaches 1,000 mg in distant or undeformed areas;

(5) The time-frequency spectrum is obtained after the short-term Fourier transform of the time domain curve during the material source initiation. The time-frequency spectrum at the monitoring point with surface deformation steps up and down in low-frequency and high-energy regions in the direction perpendicular and parallel to the surface of the material source, respectively. However, some sources have insignificant change characteristics of the time-frequency spectrum during debris flow initiation, which is closely related to the initiation process. The material source with larger particles has less obvious changes of the time-frequency spectrum;

(6) The variation patterns of parameters such as soil pressure and vibration acceleration at the moment of material initiation were obtained based on indoor experiments. It was determined that changes in soil pressure, slope angle, and vibration acceleration can serve as criteria for initiation of debris flow. However, due to the complexity of engineering practices, specific early warning thresholds need to be further established through extensive on-site monitoring and experiments.

(7) Although the time difference between the abrupt changes in pre-warning indicators and debris flow initiation is small, the variation patterns of multiple indicators can be used to determine whether an area is in a high-risk state. In large-scale regions, real-time monitoring of numerous potential debris flow areas can be achieved at relatively low cost, demonstrating substantial practical and engineering value.

Conclusion

An indoor simulation experiment system was designed to study the initiation process of coarse-grained gravel-type debris flow under different particle sizes and slope angles. The interplay among the mean particle size, water flow, the slope angle of the material source, and debris flow initiation has been elucidated to assess the dynamic changes in various characteristic parameters. This analysis formed initiation criteria specific to gravel-type debris flow.

(1) The slope angle was positively correlated with water power required for debris flow initiation under the same material source and the same combined particle size. The combined particle size of the material source had a positive correlation with water power required for debris flow initiation under the same material source and the same slope angle. Water power required for different material source types was different under the same combined particle size and the same slope angle;

(2) The physical characteristic parameters such as humidity, soil pressure, and osmotic pressure had certain characteristics during the material source initiation. Such law could be used as a reference for the early warning and discrimination of debris flow initiation. The initiation of coarse-particle debris flow required the moisture content to reach a saturated state, approximately 100%. The osmotic pressure steadily increased with increased water power. It remained unchanged or decreased when the point was activated. The soil pressure plummeted exponentially and then stabilized before and after debris flow initiation. This value might have a certain upward trend, not exceeding the initial soil pressure value. The slope angles at different positions varied from 0 to 90°. A closer distance to the initial position indicated a greater angle of change;

(3) Monitoring the dynamic characteristics of the material source through vibration phenomena was the most effective way to provide early warning for debris flow initiation. The amplitude and frequency domain characteristics of the vibration acceleration changed significantly at the initiation stage. The vibration acceleration changed from 2,000 to 6,000 mg during material source initiation. It also reached 500 mg at the position far away from the initial deformation point. Besides, the frequency characteristics of the material source remained unchanged at the stabilization phase. The vibration acceleration plummeted to near 0 in the initial stage of debris flow. The frequency band energy and center-of-gravity frequency had simultaneous plummet characteristics. Therefore, dynamic characteristic parameters such as the vibratory impact acceleration and main vibration frequency were used as early warning indicators for identifying debris flow initiation.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ma, C. et al. Radar monitoring and numerical simulation reveal the impact of underground blasting disturbance on slope stability. Remote Sens. 17 (15), 2649 (2025).

Li, Z. H. et al. Debris flow susceptibility assessment based on topo-hydrological factors at different unit scales: a case study of Mentougou district, Beijing. Environ. Earth Sci. 80 (9), 365 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Characteristics of debris flow dynamics and prediction of the hazardous area in Bangou Village, Yanqing District, Beijing, China. Open. Geosci. 16 (1), 20220655 (2024).

Zhou, W. T. et al. Extreme climate and human activities contribute to low-frequency, large-scale catastrophic debris flow: a case study in the Heishui gully. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 15 (1), 2316719 (2024).

Li, C. A. Study on Automatic Monitoring and Early Warning System of Debris Flow along Railway Line in Mountainous Area (Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, 2021).

Qian, N. & Wang, Z. Y. A preliminary study on the mechanism of debris flows. Acta Geogr. Sin. 39 (1), 33–43 (1984).

Du, J., Fan, Z. J., Xu, W. T. & Dong, L. Y. Research progress of initial mechanism on debris flow and related discrimination methods: A review. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 629567 (2021).

Takahashi, T. Mechanics-based approach toward the mitigation of debris flow disasters. In Landslides-Disaster Risk Reduction (eds Sassa, K. & Canuti, P.) 89–113 (Springer, 2008).

Takahashi, T. & Das, D. K. Debris Flow: Mechanics, Prediction and Countermeasures 2nd edn (CRC, 2014).

Takahashi, T., Satofuka, Y. & Kashimoto, S. Debris-Flow Hazard Mitigation (Mill, 2003).

Takahashi, T. A review of Japanese debris flow research. Int. J. Eros. Control Eng. 2 (1), 1–14 (2009).

Zhou, W. & Tang, C. Rainfall thresholds for debris flows occurrence in the Wenchuan earthquake area. Adv. Water Sci. 24 (06), 786–793 (2013).

Gao, B., Zhou, J. & Zhang, J. Macro-meso analysis of water-soil interaction mechanism of debris flow starting process. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 30 (12), 2567–2573 (2011).

Yang, J. B., Chen, X. Z., Wang, H., Tian, X. P. & Jia, L. R. An experimental study of relationship between fine grain content and permeability coefficient of debris flow deposits. Rock. Soil. Mech. 37 (11), 3184–3190 (2016).

Tognacca, C., Bezzola, G. R. & Minor, H. E. Threshold criterion for debris-flow initiation due to channel-bed failure. (2nd International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation, Taipei, China, (2000).

Gregoretti, C. The initiation of debris flow at high slopes: experimental results. J. Hydraul Res. 38 (2), 83–88 (2000).

Gregoretti, C. & Fontana, G. D. The triggering of debris flow due to channel-bed failure in some alpine headwater basins of the dolomites: analyses of critical runoff. Hydrol. Process. 22 (13), 2248–2263 (2008).

Wu, J., Kang, Z., Tian, L. & Zhang, S. Debris Flow Observation and Research in Jiangjiagou Yunnan (Science, 1990).

Chen, X. Q., Cui, P., Feng, Z. L., Chen, J. & Li, Y. Artificial rainfall experimental study on landslide translation to debris flow. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 25 (1), 106–116 (2006).

Iverson, R. M., Logan, M., LaHusen, R. G. & Berti, M. The perfect debris flow? Aggregated results from 28 large-scale experiments. J. Geophys. Res. -Earth Surf. 115 (F3), F03005 (2010).

Takahashi, T. Debris flow. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 13, 57–77 (1981).

Cui, P. Research on the Starting Mechanism of Mudslides (Beijing Forestry University, 1990).

Liu, X. L., Wang, F., Nawnit, K., Lv, X. F. & Wang, S. J. Experimental study on debris flow initiation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 1565–1580 (2020).

Okuda, S. et al. Synthetic observation on debris flow part. 5 observation at Valley Kamikamihori of Mt. Yakedake in 1978. Disaster Prev. Res. Inst. Annu. B. 22 (B-1), 157–204 (1979).

Itakura, Y., Koga, Y., Takahama, J. & Nowa, Y. Acoustic detection sensor for debris flow. (1st International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction, and Assessment, San Francisco, CA, (1997).

Suwa, H. & Sumaryono, A. Sediment discharge by storm runoff from a creek on Merapi volcano. J. JPN Soc. Eros. Control Eng. 48 (Special), 117–128 (1996).

Takahashi, T. Mechanical characteristics of debris flow. J. Hydraul Div. 104 (8), 1153–1169 (1978).

Itakura, Y., Inaba, H. & Sawada, T. A debris-flow monitoring devices and methods bibliography. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 5 (6), 971–977 (2005).

Arattano, M. & Grattoni, P. Using a fixed video camera to measure debris-flow surface velocity. (2nd International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation, Taipei, China, (2000).

He, W. S., Fang, D., Cao, S. Y., Yang, J. R. & Liu, X. N. Study on standards for incipient motion of sediment. Adv. Water Sci. 14 (2), 143–146 (2003).

Muste, M., Fujita, I. & Hauet, A. Large-scale particle image velocimetry for measurements in riverine environments. Water Resour. Res. 44 (4), W00D19 (2008).

Scheidl, C. et al. Analysing debris-flow impact models, based on a small scale modelling approach. Surv. Geophys. 34, 121–140 (2013).

Hu, M. J. & Wang, R. Testing study on the correlation among landslide, debris flow and rainfall in Jiangjia Valley. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 22 (5), 824–828 (2003). (in Chinese).

Zhao, C., Xie, M. W., Huang, Z. J. & Wu, Z. X. Research on reservoir water level change identification based on image matching. China Meas. Test. 50 (7), 10–16 (2024). (in Chinese).

Chmiel, M. et al. Machine learning improves debris flow warning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 (3), e2020GL090874 (2021).

Qiu, C. C., Su, L. J. & Geng, X. Y. A precipitation downscaling framework for regional warning of debris flows in mountainous areas. Nat. Hazards. 120, 1979–2004 (2024).

Li, Y., Liu, J. J., Hu, K. H. & Su, P. C. Probability distribution of measured debris-flow velocity in Jiangjia Gully, Yunnan Province, China. Nat. Hazards. 60, 689–701 (2012).

Tognacca, C. & Bezzola, G. R. Debris-flow initiation by channel-bed failure. (1st International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction, and Assessment, San Francisco, CA, (1997).

Pellegrino, A. M. & Schippa, L. A laboratory experience on the effect of grains concentration and coarse sediment on the rheology of natural debris-flows. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 749 (2018).

Yang, T. Q. et al. Grain configuration effect on pore water pressure in debris flow. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 660634 (2021).

Li, J., Chen, N. S., Zhao, Y. D., Liu, M. & Wang, W. Y. A catastrophic landslide triggered debris flow in china’s yigong: factors, dynamic processes, and tendency. Earth Sci. Res. J. 24 (1), 71–82 (2020).

Dai, Z. L., Xu, K., Wang, F. W., Yang, H. F. & Qin, S. W. Numerical investigation on the kinetic characteristics of the Yigong debris flow in Tibet, China. Water 13 (8), 1076 (2021).

Yu, Z. W., Mao, J. F., Guo, F. Q. & Guo, W. Non-stationary random vibration analysis of a 3D train-bridge system using the probability density evolution method. J. Sound Vibr. 366, 173–189 (2016).

Li, Z. D. et al. Vibration signal characteristics of debris flow initiation and motion experiments by considering clay content. Front. Earth Sci. 13, 1519353 (2025).

Funding

This research was funded by the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51974014), General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52374077), and “14th Five-Year Plan” National Key R&D Program (2022YFC2904102-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, visualization, Z.H., C.C., M.X. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H., C.C., C.M., Z.C. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.H., C.C., M.X. and C.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Chen, C., Xie, M. et al. The initiation mechanism of gravel-type debris flow based on laboratory simulation experiments. Sci Rep 15, 37482 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21533-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21533-1