Abstract

The family Pieridae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) is known for its ecological and conservation significance; however, little is known about its spatial distribution pattern and climate vulnerability in mainland China, complicating the formulation of effective conservation strategies. Pierinae and Coliadinae are widely distributed across most parts of the research zone, especially in the southern regions. Conversely, Dismorphiinae is mainly distributed in the west-central and northeastern parts. Pierinae and Coliadinae flourished over a wider range of elevations in open environments with warmer and more humid habitats, whereas Dismorphiinae is restricted to a narrow elevation range in forested areas with cooler and drier habitats. Therefore, it was necessary to study their distribution patterns separately. The MaxEnt model was applied to analyze the influence of bioclimatic variables on their distribution throughout three historical eras: the Last Interglacial (LIG), the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and the Current (1970–2000). Pierinae and Coliadinae showed a uniform increase in overall highly suitable habitats, while Dismorphiinae showed an initial increase and then a decrease. Due to global warming, all three subfamilies might experience contraction in highly suitable habitats. Most Pieridae species are projected to experience shrinkage in highly suitable habitats, leading to decreased species diversity. These findings highlight divergent historical distribution patterns and habitat preferences among Pieridae subfamilies, yet project a shared vulnerability to future habitat contraction under climate warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Butterflies are a well-known group of insects that provide significant ecological benefits, including pollination, and serve as biodiversity indicators. They are effective transition indicators for climatic change due to their short life span, high mobility, and specific habitat requirements1,2. Therefore, their conservation is important for sustaining biodiversity. Recently, the conservation status of butterflies has gained notable attention due to their ecological values and vulnerability to climate change. Different conservation projects across China safeguard multiple butterfly species from dangers like habitat destruction, anthropogenic activity, and climate change3,4.

Studies indicate that climate change has led to a considerable decline in the populations of some Pieridae species5. A study in the Hengduan Mountains, China, showed considerable habitat contraction and northward movement in numerous Parnassiinae species3. Additionally, research has revealed the adverse effects of ambient temperature and precipitation on the suitable habitats of different butterfly species3,6. A study conducted in Europe illustrated that, despite changes in distribution and suitable habitats, butterflies’ genetic diversity is also at risk7. Furthermore, climate change affects butterfly phenology8, elevational dynamics3,6, and flight-related morphological characteristics9. However, the absence of such information has hindered the formulation of effective conservation strategies3, owing to insufficient large-scale ecological studies on the potential distribution patterns of butterflies across different periods.

Examining butterfly distribution across various periods offers important insights into historical biogeographic trends, facilitating the identification of climate refugia, forecasting species susceptibility to environmental change, and defining naturally protected regions3,10. During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), numerous mild-climate species shrank their habitats toward glacial refugia11. Certain species survived glaciation by seeking shelter in non-glaciated regions, while others maintained their populations near the peripheries of glaciated regions12,13. Conversely, certain species thrived in cold environments and expanded their habitats during the LGM14. Ecological niche models (ENMs) assess species-environment associations by identifying and modeling key environmental variables that determine their suitable habitats3,15. Researchers commonly use the maximum entropy (MaxEnt) model in various fields of ecology and geography, including environmental monitoring and management, conservation of endangered species, and biodiversity preservation, by generating habitat suitability maps3,15.

Compared with other East Asian countries, mainland China has the highest butterfly diversity16. Pieridae, commonly known as whites and sulphurs, is a family of mostly moderate-sized butterflies that are globally distributed and contain approximately 1000 extant species. Pieridae is composed of four subfamilies: Pierinae (whites and yellows), Coliadinae (sulphurs and yellows), Dismorphiinae (mimic whites), and Pseudopontiinae. The subfamily Pseudopontiinae is endemic to Africa and consists of only one genus, while the other three subfamilies are widely distributed across various17,18,19,20 zoogeographic regions. Pierinae occupy diverse habitats18 ranging from arid lowland deserts (Euchloe)21,22 to elevated regions, including the Himalayas and Pamir (Baltia) ranges and the Andes Mountains (Tatochila)23,24,25,26. Several species within Coliadinae (Colias mongola, C. ladakensis) inhabit frigid environments27,28,29, whereas most Euremini species are found only in tropical and subtropical regions30,31. A limited number of Dismorphiinae (Leptideini) inhabit temperate zones32, while the predominant species belonging to Dismorphia and Lienix are strictly tropical, mainly found in the Americas33,34.

Despite acknowledging climate change as a critical determinant of butterfly distribution and diversity, its impact on Pieridae in mainland China remains inadequately understood. Moreover, habitat variations among Pieridae’s three subfamilies (Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae) across the study area remain poorly investigated. This knowledge gap poses significant threats to the diversity of Pieridae and their suitable habitats. Therefore, we compiled the inaugural comprehensive dataset for Pieridae to (1) conduct a comparative investigation of the distribution patterns among three subfamilies: Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae; (2) study the influence of environmental variables on the distribution of Pieridae and analyze the relationship between Pieridae species richness and environmental variables; (3) determine how the distribution of Pieridae changed across three historical eras, the Last Interglacial (LIG), the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and 1970–2000 (Current); and (4) investigate the impacts of climate change on the suitable habitat of Pieridae.

Materials and methods

Study site

Mainland China is located in East Asia35. The varied landscape of mainland China includes the Himalayan mountain range in the southwest and vast plains in the east. The elevation fluctuates significantly, ranging from sea level along the eastern coast to above 8,844 m (m) in the Tibetan Plateau. The climate of the study area features different conditions, ranging from temperate zones in the north to subtropical climates in the south35. The northern part of the study site experiences two long and distinct seasons (winter and summer), with brief transitional phases in between. Winters are dry and chilly, with temperatures frequently falling below freezing. Summers are hot with a high rate of precipitation. The southern region of the research zone is green throughout the year. Higher temperatures, heavy precipitation, and humidity create an ideal environment for the flora and fauna of the region. Winters are shorter (January to March), yet they can be frigid36,37.

Occurrence data

The distribution points of Pieridae were collected from the following sources: the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2024)), using the package ‘rgbif’ 38,88; China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, https://www.cnki.net/ (accessed on 22 June 2024)); iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025)), using the package89 ‘rinat’;39 Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/ (accessed on 15 April 2025)); and field collection records. Missing latitudes and longitudes were incorporated utilizing Google Earth (https://earth.google.com/), while ambiguous data were removed.

A total of 12,306 distribution points were collected for 164 Pieridae species, including 8,085 for Pierinae, 4,001 for Coliadinae, and 220 for Dismorphiinae. Out of the total species collected, 101 belong to Pierinae, 56 to Coliadinae, and 7 to Dismorphiinae. Notably, within the study area, Dismorphiinae was represented only by the genus Leptidea. The R package ‘spThin’ was utilized to conduct spatial autocorrelation analysis, which helps overcome the effects of model overfitting resulting from the clustering of species distributions. Additionally, it removes duplicate and spatially very close records (distance < 5 km)40. After preprocessing, the present study included 3,718 data points, with 2,195 attributed to Pierinae, 1,385 to Coliadinae, and 138 to Dismorphiinae.

Environmental variables

Nineteen bioclimatic variables from 1970 to 2000 (Current) (Fig. S1; Table 1), the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and elevation (Fig. S2a) with a resolution of 2.5′ (\~4.3 km) were obtained from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org/) 41. The Last Interglacial (LIG) variables were also downloaded from the WorldClim database with a resolution of 30 s (1 × 1 km2)40. The Community Climate System Model 4 (CCSM4) with a resolution of 2.5′ (\~4.3 km) was utilized for climate prediction40. Initially, Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) projections were examined; however, the RCPs were ultimately chosen for analysis as they provided more accurate and realistic outputs in alignment with observed patterns. The WorldClim database was accessed on 24 June 2024. Variables, including Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) (Fig. S2b), Net Primary Productivity (NPP) (Fig. S2c), human population (HP) (Fig. S2d), and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Fig. S2e), were obtained from the Resources and Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences website (RESDC, http://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 24 June 2024))42,43, with a resolution of 30 s (1 × 1 km2).

To prevent the risk of overfitting in the MaxEnt model due to strong associations between bioclimatic factors generally for each subfamily (Figs. S3–S5) and particularly for each species, the correlation among bioclimatic variables was comprehensively examined using the ‘corrplot’ package44. The percent contribution of bioclimatic variables generally for three subfamilies (Table 1) and specifically for each species was calculated using MaxEnt v3.4.4. The selection criteria used in the final MaxEnt model involved retaining the six most influential factors, generally for every subfamily and particularly for each species with high contribution rates between pairs of strongly correlated variables (|r| ≥ 0.8)40.

Future projections

Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) are defined trajectories established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for the concentrations of four greenhouse gases. RCPs are classified into four categories: RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5. They show the CO2 concentrations of 490, 650, 850, and 1370 mL/m3 and the overall radiation intensities of 2.6, 4.5, 6.0, and 8.5 W/m2 by the end of 2100, respectively45,46. In the present study, the suitable habitats for three subfamilies in general and each species in particular were projected under RCP4.5 for 2050s (average for 2041–2060) and 2070s (average for 2061–2080).

Analysis of species richness

The distribution of species richness in the study area was displayed using a grid of size 1 × 1 (~ 100 km × 100 km)40 in R v4.4.3. A presence (1) or absence (0) matrix for each species was generated utilizing the ‘letsR’ package, with rows indicating geographic locations (grid cells) and columns representing species47. Subsequently, we exported the resultant matrix into EstimateS 9.1 software, utilizing default settings to generate a cumulative curve. We assessed data accuracy using this curve.

The mean of environmental factors was calculated in 4.5 km x 4.5 km grid cells, using the R package ‘terra’ to obtain the values of each factor in a 1° grid. The correlation between each variable and species richness was examined using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method under the function ‘lm()’40.

Modeling and evaluation

‘ENMeval’ was used in R v4.4.3 to reduce model overfitting generally for three subfamilies and specifically for each species by modifying parameters of feature combinations, including linear (L), quadratic (Q), product (P), threshold (T), and hinge (H) 48,49. The regularization multiplier (RM) value was set from 1 to 3 in increments of 1. This configuration was combined with various feature types (L, H, LQ, LQH, LQHP, and LQHPT)48. The Akaike information criterion (AICc) values were calculated48 using ‘block’. For Pierinae, LQHPT and RM value 1, while for Coliadinae and Dismorphiinae, LQHP and RM value 1 correspond to the lowest delta AICc model50 (Fig. S6), which were chosen in the final MaxEnt model. 25% of the total points were selected for testing, while 75% were kept for training. A total of 10,000 background points were selected40. To achieve data normality for each subfamily, we decreased the temperature (Bio1, Bio2, and Bio3) and precipitation (Bio12, Bio15, Bio16, and Bio17) values in the original paleoclimatic variable layers by a factor of 10. This method was also applied for the corresponding six most influential variables of each species. The suitable survival areas were classified into four categories: unsuitable areas (0–0.2), less suitable areas (0.2–0.4), moderate suitable areas (0.4–0.6), and highly suitable areas (0.6–1)40. Finally, the habitat suitability maps were generated. The area corresponding to each suitability class was computed in million km2.

We employed area under the curve (AUC) and the true skill statistic (TSS) values to evaluate MaxEnt model performance for each subfamily40. The ROC (receiver operating characteristics) curve shows the true-positive rate (sensitivity) as the ordinate and the false-positive rate (1-specificity) across various thresholds as the abscissa. The AUC score was calculated by determining the area bounded by the curve and abscissa51,52. The TSS value is calculated as specificity + sensitivity – 1 40,53. Based on the AUC score, the model’s efficiency can be classified as failing (0.5–0.6), unacceptable (0.6–0.7), fair (0.7–0.8), excellent (0.8–0.9), or exceptional (0.9–1). Based on the TSS value, the model’s performance can be classified as unacceptable (< 0.4), bad (0.4–0.55), fair (0.55–0.7), good (0.7–0.85), or excellent (> 0.85)40.

Species-level stacked species distribution modeling (S-SDM)

We employed a species-level stacked species distribution modeling (S-SDM)3 method to analyze the distributions and species richness of Pieridae butterflies. Occurrence records for each species were filtered to include only those with a minimum of five spatially unique points. The corresponding six most significant, uncorrelated (|r| ≥ 0.8) 40 bioclimatic factors were chosen as predictors for each species. Spatial thinning was utilized to mitigate sampling bias by eliminating duplicate entries within the same raster cell. S-SDM was constructed in R v4.4.3, utilizing MaxEnt v3.4.4 via the ‘dismo’ package54. For every species, 75% of occurrence points were allocated for training and 25% for testing, and 10,000 background points were randomly selected40. Feature classes and regularization multipliers were implemented (see Modeling and evaluation) for each species.

The evaluation of model performance was conducted utilizing the AUC and TSS3,40. The threshold that optimized TSS was employed to transform continuous predictions into binary presence-absence maps. The species-specific binary maps were summed to produce a richness map3. The suitable habitats were further classified into four tiers40 (see Modeling and evaluation). For every species, the area corresponding to each suitability class was computed in million km240.

Results

Associations between species richness and environmental factors

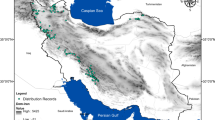

Our study reveals that the family Pieridae, with abundant geographic records, is widely distributed in mainland China. The subfamilies Pierinae and Coliadinae were particularly abundant in the southern part, whereas Dismorphiinae was widely distributed in the northern part (Fig. 1). The species accumulation curve revealed that the database contained 164 documented species of Pieridae; however, the bootstrap estimator suggests a total of 173 species. The proportion of collected species was 94.80%, showing that most species had been gathered (Fig. S7).

Geographic distribution of Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae in mainland China after removing spatially clustered (< 5 km) data points. The figure was generated using R software (version 4.4.3; https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/).

The species richness showed an irregular spatial distribution pattern. The Pierinae species exhibited a high concentration in Xishuangbanna (southern Yunnan) and the southern Hengduan Mountains (Fig. 2a). In contrast, Coliadinae species showed a high abundance in the southern Hengduan Mountains and the Wuling Mountains (Fig. 2b). The Dismorphiinae species were notably concentrated in the Qinling Mountains (Fig. 2c).

This study analyzed the correlation between species richness patterns and climatic factors using the OLS method. All subfamilies exhibited a significant positive correlation with temperature (Bio2, Bio4, and Bio7) and precipitation (Bio15). Pierinae and Coliadinae showed negative correlations with temperature and precipitation (excluding the above-mentioned variables). A similar negative association was observed with NDVI. Furthermore, elevation, GDP, HP, and NPP exhibited no significant impact. Dismorphiinae did not show any correlation with temperature (Bio5, Bio8, and Bio10), precipitation (Bio13), NDVI, GDP, HP, and NPP. In contrast, temperature (Bio1, Bio3, Bio6, Bio9, and Bio11), precipitation (Bio12, Bio14, Bio16, Bio17, and Bio19), and elevation showed a significant negative relationship (Table S1).

MaxEnt model evaluation and the influence of Climatic factors

The MaxEnt model performed well, with AUC values of 0.787 for Pierinae (Fig. S8a), 0.792 for Coliadinae (Fig. S8b), and 0.882 for Dismorphiinae (Fig. S8c). The TSS values recorded for Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae were 0.783, 0.749, and 0.729, respectively. The model was developed using six major bioclimatic factors for each subfamily (Table S2). Jackknife analysis indicates that, for Pierinae, Bio6 had the highest gain when employed independently and the greatest decline when excluded (Fig. 3a). For Coliadinae (Fig. 3b) and Dismorphiinae (Fig. 3c), Bio12 had the greatest gain when used alone and the highest drop when removed. Response curves were created for the six most influential bioclimatic variables for Pierinae (Fig. S9), Coliadinae (Fig. S10), and Dismorphiinae (Fig. S11).

We calculated AUC and TSS per species (Table S3): Pontia chloridice had the lowest AUC (0.544) and TSS (0.181), while Delias descombesi achieved the highest AUC (0.996) and TSS (0.986). The average AUC and TSS across all species were 0.900 and 0.750, respectively.

Distribution trends along the elevation gradients

Elevation significantly influenced the distribution of Pieridae. The populations of Pierinae and Coliadinae are primarily found at elevations ranging from 0 to 1000 m. However, as elevation increased beyond this range, species diversity decreased (Fig. 4). Notably, only a limited number of species were recorded over 5000 m. Pierinae species recorded above 5000 m were Aporia larraldei, Baltia butleri, Leptosia nina, Pieris aljinensis, P. brassicae, and P. canidia. Furthermore, Coliadinae species reported above 5000 m were Colias cocandica, C. eogene, C. ladakensis, C. nina, C. wiskoti, Dercas nina, and Gonepteryx amintha. The population of Dismorphiinae showed a pronounced decline above 1500 m (Fig. 4). Interestingly, only five occurrence points were recorded at elevations ranging from 3000 to 3500 m, representing four Leptidea species: L. amurensis, L. gigantea, L. morsei, L. sinapsis, and L. serrata.

Habitat suitability estimation across historical projections

Using historical climate data (LIG, LGM, and Current (1970–2000)), habitat suitability maps were created for Pierinae (Fig. 5a), Coliadinae (Fig. 5b), and Dismorphiinae (Fig. 5c). The prediction of suitable habitats for Pierinae showed that the regions identified as highly suitable during the LIG, LGM, and Current eras were mostly located in Shandong Province, Henan Province, the Qinling Mountains, and the southern part of the study area. The distribution of Pierinae across three historical eras showed notable shifts due to temperature changes. During the transition from the LIG to LGM, temperatures decreased, which subsequently increased the highly suitable regions for Pierinae from 1.147 to 1.939 million km2. Most highly suitable regions have expanded toward the southern and eastern parts of the study area. From the LGM to Current period, alongside rising temperatures, highly suitable regions increased from 1.939 to 2.413 million km2, mainly in the southern, eastern, and central regions of the research zone. The total area of suitable regions rose from 3.443 to 4.846 million km2, representing a 40.75% increase (Fig. 5a; Table 2).

Distribution of suitable regions for Pieridae butterflies: (a) Pierinae, (b) Coliadinae, and (c) Dismorphiinae, across three historical periods: the Last Interglacial, LIG; the Last Glacial Maximum, LGM; and Current, 1970–2000. Habitat suitability classes are represented by color gradients: white (0–0.2, unsuitable), green (0.2–0.4, less suitable), blue (0.4–0.6, moderate suitable), and red (0.6–1, highly suitable).

The simulation of suitable habitats for Coliadinae revealed that during the LIG, LGM, and Current periods, highly suitable habitats were mostly found in the southern part of the research zone, the Qinling Mountains, and parts of Shandong, Henan, and Liaoning provinces. Temperature fluctuations caused significant changes in their distribution over three historical periods. During the transition from the LIG to LGM, a decrease in temperatures led to an increase in highly suitable habitats from 1.199 to 1.841 million km2, which expanded toward Yunnan Province, Jiangxi Province, and the Qinling Mountains. During the transition from the LGM to Current period, the area of highly suitable habitats increased from 1.841 to 2.739 million km2 in response to rising temperatures. Moderate suitable areas changed into highly suitable ones. The total area of suitable habitats increased from 3.339 to 4.852 million km2, reflecting a 45.31% increase (Fig. 5b; Table 2).

The prediction of appropriate habitats for Dismorphiinae revealed that during the LIG, LGM, and Current periods, the highly appropriate habitats were mostly found in the Tibetan Plateau, the Qinling Mountains, Guizhou, Jiangsu, Anhui, Jilin, and Heilongjiang Provinces. As temperatures dropped from the LIG to LGM, the highly suitable habitats for Dismorphiinae increased from 0.313 to 0.942 million km2 and shifted toward the Qinling Mountains, Guizhou Province, Jiangsu Province, Anhui Province, and central China. Overall, the suitable areas expanded from 1.541 to 2.492 million km2, reflecting an increase of 61.71%. Due to rising temperatures during the transition from the LGM to Current period, the highly suitable areas decreased from 0.942 to 0.693 million km2. Moderate and high suitability areas disappeared from Guizhou Province and central and eastern China, with a distributional shift toward the Changbai Mountains (Fig. 5c; Table 2).

The prediction of suitable habitats for each species showed that, from the LIG to LGM, the number of highly suitable habitats for 13 Pierinae species decreased, while those for other species increased (Table S4). Four Coliadinae species—Catopsilia pyranthe, Colias erate, C. poliographus, and Eurema hecabe—had a significant drop in highly suitable habitats, whereas the remaining species saw a notable increase (Table S5). Notably, all Dismorphiinae species showed a significant increase in highly suitable habitats (Table S6).

During the transition from the LGM to Current period, the number of highly appropriate areas for 34 Pierinae species expanded, while those for 20 species decreased (Table S4). Six Coliadinae species—C. heos, C. ladakensis, Gonepteryx amintha, G. aspasia, G. mahaguru, and G. maxima—had a significant decline in highly suitable habitats, while the other species showed a significant increase (Table S5). Except for Leptidea serrata, all Dismorphiinae species showed a notable increase in highly suitable habitats (Table S6).

Distribution trends under future projections

The global climatic model RCP 4.5 for 2050s and 2070s predicted that, with an increase in temperature from mild to high, the area of highly suitable regions for Pierinae is expected to decrease from 1.945 to 1.682 million km2, a decrease of 13.52% (Table 2). The majority of the highly suitable regions in central and eastern China are expected to change into less suitable regions (Fig. 6a).

The area of highly suitable regions for Coliadinae is expected to decrease slightly, from 2.491 to 2.356 million km2, a decrease of 5.42% (Table 2). Some highly suitable regions in central and eastern China are expected to change into moderate suitable regions (Fig. 6b). As a result, less and moderate suitable areas are expected to increase from 3.209 to 3.506 million km2 (Table 2).

The area of highly suitable regions for Dismorphiinae is expected to decrease from 0.463 to 0.361 million km2, a decrease of 22.03% (Table 2). As a result, some of the highly suitable habitats in the Changbai and Khingan Mountains are expected to change into moderate suitable habitats (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, the areas of less and moderate suitable regions are predicted to decrease slightly, from 1.909 to 1.849 million km2, a decrease of 3.14% (Table 2).

Distribution of suitable regions for Pieridae butterflies: (a) Pierinae, (b) Coliadinae, and (c) Dismorphiinae, under Current (1970–2000) and global warming scenarios. Habitat suitability classes are shown by color gradients: white (0–0.2, unsuitable), green (0.2–0.4, less suitable), blue (0.4–0.6, moderate suitable), and red (0.6–1, highly suitable).

To identify suitable habitats for each species, the regions considered highly suitable for 17 Pierinae species are expected to expand by the 2070s, whereas areas classified as highly suitable for 37 species are predicted to shrink (Table S4). Similarly, in Coliadinae, highly suitable habitats for 10 species are expected to increase, while those for 14 species are expected to decline (Table S5). Notably, highly suitable habitats for all Dismorphiinae species are expected to decrease (Table S6).

Discussion

Determinants of species richness patterns

Climatic variables significantly influence the distribution patterns, population sizes, and habitat dynamics of butterflies3,5. This study examined the distribution patterns of Pieridae across mainland China. The southern part of the study area had a wide distribution of Pierinae and Coliadinae. Conversely, the central-western and northeastern regions exhibited a broad distribution of Dismorphiinae (Fig. 1). Pierinae diversity hotspots were located in Xishuangbanna and the southern Hengduan Mountains (Fig. 2a), while Coliadinae were located in the southern Hengduan and Wuling Mountains (Fig. 2b). The diversity hotspot of Dismorphiinae was predominantly found in the Qinling Mountains (Fig. 2c).

The southern part of the study area is known for its warm, subtropical climate, which promotes the growth of diverse vegetation35,37, especially Fabaceae and Brassicaceae species, providing important resources for Pierinae and Coliadinae17,18,55,56,57,58. Northern China, characterized by a temperate climate with pronounced seasonal variations and cold winters, influences local vegetation and the survival strategies of butterflies35,57. Flora of the region, particularly certain Fabaceae species, thrives under these conditions, supporting the larvae of Dismorphiinae (particularly Leptidea: Leptideini species)17,55,58,59. Pierinae, characterized by its white or pale coloration17,60, likely reflects sunlight, aiding in thermoregulation and enhancing its prevalence in warmer, sunnier regions60,61,62. Coliadinae, characterized by its yellow and orange colors17,60, likely regulates heat through coloration, favoring warmer habitats60,61,62. Dismorphiinae exhibit remarkable mimicry and cryptic coloration, and their distribution is significantly influenced by host plant availability and habitat type17,60.

Pierinae and Coliadinae are medium-to-large-sized butterflies, including both migratory and non-migratory species, recognized for their robust flight. In contrast, Dismorphiinae (Leptidea) are small-to-medium-sized butterflies, generally non-migratory, known for their slow and fluttering flight17,60. The strong and long-lasting flight of Pierinae and Coliadinae facilitates extensive migration, consequently enhancing their geographical distribution and enabling them to inhabit diverse environments19,60. Their robust flight decreases predation risk and facilitates access to diverse food sources. Furthermore, Pierinae and Coliadinae are chemically protected by glucosinolates and cyanogenic glucosides, respectively, making them taste hazardous or even toxic for predators58. In contrast, Dismorphiinae (particularly Leptidea: Leptideini species), due to their limited flying capabilities, primarily rely on local environments, resulting in limited distribution and increased vulnerability to predators17,60,63. However, they are chemically protected by cyanogenic glucosides, making them taste bad for predators58. Thus, the distributions of Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae are shaped by their size, flight capabilities, and both biotic and abiotic factors. To precisely assess the influence of environmental factors on the species richness of Pieridae in mainland China, we used spatial autocorrelation analysis (OLS method) (Table S1)40.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis found that Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae were positively correlated with temperature (Bio2, Bio4, and Bio7) and precipitation (Bio15). However, certain temperature and precipitation factors were negatively associated with all three subfamilies (Table S1), suggesting that higher temperatures and alterations in rainfall could render their habitats less suitable. These climate preferences probably indicate their adaptation to stable humidity levels that benefit their host plants and temperature conditions that match their life cycles. Such behavior highlights their susceptibility to climate change-induced variations in rainfall and temperature3,7,64.

The different responses of Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae to NDVI and elevation underscore their unique ways of adapting to the environment. Pierinae and Coliadinae flourished in open areas like fields, meadows, and gardens. Consequently, they tend to avoid areas with dense vegetation, which could limit their movement and access to food sources. Dismorphiinae (Leptidea), on the other hand, did not show any relationship with NDVI because they rely on specific local conditions and prefer forest edges. The elevation patterns further distinguished these groups: Pierinae and Coliadinae revealed no correlation with elevation, with species recorded from lowland habitats to high elevations exceeding 5000 m, showing broader climate adaptability. In contrast, Dismorphiinae showed a negative association with elevation, possibly due to temperature and precipitation constraints (Table S1). A similar study in the Hengduan Mountains found that Papilioninae preferred lower elevations (valleys) characterized by warmer and more humid conditions. In comparison, Parnassiinae thrives at higher elevations (subalpine to alpine) characterized by cooler and drier conditions3. Variables, including GDP, HP, and NPP, showed no significant correlation with all three subfamilies. These results showed that habitat preferences of Pieridae species are shaped by climate, types of vegetation, and land characteristics, which is important for targeted conservation strategies.

Association between bioclimatic factors and habitat suitability

The MaxEnt model revealed that temperature (Bio2, Bio4, Bio6, and Bio8) and precipitation (Bio15 and Bio16) (Fig. S9; Table S2) significantly influenced the distribution of Pierinae. Similarly, Coliadinae was extremely sensitive to temperature (Bio3, Bio4, and Bio5) and precipitation (Bio12, Bio15, and Bio17) (Fig. S10; Table S2). These results suggest that both Pierinae and Coliadinae primarily inhabit temperate, seasonally stable climates with adequate moisture. On the other hand, Dismorphiinae distribution was mainly driven by temperature (Bio1, Bio3, Bio4, and Bio5) and precipitation (Bio12 and Bio15) (Fig. S11; Table S2), suggesting their prevalence in areas characterized by moderate precipitation, low temperatures, and moderate climatic seasonality. This pattern reflects their adaptation to stable and temperate environmental conditions.

Temperature and precipitation are critical variables of butterflies distribution, affecting their natural habitat and distribution3,65. Increased precipitation promotes plant growth, increasing food availability and habitat suitability for insects6,66. Conversely, reduced precipitation results in drier soil and scarcity of host plants67,68. Global warming exerts two effects: it directly affects habitats through variations in temperature and precipitation, while indirectly restricting butterfly dispersion and growth6,65. For example, Nielsen and Nielsen69 identified a temperature-driven increase in flight activity in Ascia monuste, a response presumably associated with changed mate-seeking behaviors, habitat expansion, population growth, and enhanced breeding processes3,70,71. In contrast, extreme cold temperatures in the Nanling Mountains reduced temperate and tropical butterfly populations by 50% and 88%, respectively72, and cold environments negatively influenced Euphydryas editha populations73. Critically, thermal stability is crucial for reproductive success by generating phenological matches and resource availability74,75. These findings underscore the importance of considering microclimatic variation when examining butterfly populations in the context of climate change.

Modeling habitat suitability across three historical periods

During the transition from the LIG to LGM, the size of suitable habitats expanded considerably due to a decline in global temperature. During glaciation, lower temperatures facilitated cold-adapted species to migrate to the foothills and extend their ranges7,10. The current study revealed a general increase in highly suitable habitats across all subfamilies (Table 2), with a significant rise in highly suitable habitats for most species within Pierinae (Table S4) and Coliadinae (Table S5). The rise in habitats for both Pierinae and Coliadinae, which prefer warmer conditions, may result from shifts in host-plant distributions, micro-refugia establishment, and the study area’s complex landscape. Conversely, all cold-adapted Dismorphiinae species (Table S6) showed expansion in highly suitable habitat, which may be due to migration towards the foothills. After glaciation, global temperatures gradually increased. Consequently, Pierinae (Fig. 5a) and Coliadinae (Fig. 5b) expanded deeper into southern and northern regions of the study area. Most species showed an increase in highly suitable habitats, while some species showed a decrease (Tables S4,5). Conversely, Dismorphiinae generally experienced a reduction in highly suitable habitats and migrated further toward the north (Fig. 5c). However, upon examining individual species, three showed a slight increase in highly suitable habitats, while one species showed a decline (Table S6). These variations likely indicate species-specific migratory behaviors17,76, food availability, and larval host plants, exacerbated by temperature and precipitation fluctuations3,6,66,70,71. Our results correlate with previous ecological research documenting area and habitat appropriateness changes in butterfly species between the LGM and Current eras7,77,78.

Future shifts in distribution patterns

Future climate scenarios predict that most species are expected to experience range shifts toward higher altitudes and latitudes, potentially leading to suitable habitat loss3,40. This study suggests that Pierinae (Fig. 6a), Coliadinae (Fig. 6b), and Dismorphiinae (Fig. 6c) would generally face habitat contraction, with highly suitable habitats for all three subfamilies expected to decrease significantly (Table 2). By the 2070s, most species within Pierinae (Table S4) and Coliadinae (Table S5) would face habitat contraction, although certain species would face habitat expansion. Conversely, all Dismorphiinae species would face habitat contraction (Table S6). Such habitat loss may push certain species toward regional extinction, as their migratory abilities restrict them to novel appropriate habitats7,79, additionally limited by adverse climatic or vegetative conditions80. For example, 16 mountain-restricted butterfly species in Spain have already experienced more than 30% suitable habitat shrinkage over the past 30 years due to global warming81. Furthermore, Maclean and Wilson90 analyzed 188 anticipated and 130 observed responses to global warming and found extinction threats for 10–14% of examined species.

In contrast, some species might expand their habitats due to their remarkable dispersal capabilities, diverse food preferences, efficient use of transient habitats, and outstanding temperature tolerance3,76. Elevated temperatures may cause more frequent and efficient territorial and mating behaviors, which could increase suitable habitat availability. We hypothesized that the study area’s complex terrain would enable these species to locate new suitable habitats, assuming that habitat exploration is part of their behavior. Additionally, the expansion of food plants may add to their migration. Liang et al. 82 proposed that mountainous flora might expand their habitats due to global warming, as the complex landscape could provide shelter within particular elevation ranges. Consequently, specific Pieridae species may shift to higher elevations. This is not only in line with numerous cases from the Korean Peninsula, America, and Europe as documented by Taheri et al. 83 but also supported by the findings from other phyla, such as plants56, birds84, and mammals85.

Implications for ecological conservation

Identifying suitable habitats for flora82 and fauna3,40 across different climatic conditions is essential for improving conservation strategies. Advancements in ecological modeling have significantly improved our ability to predict the geographic distribution of plants82 and animals3,40, thereby enabling more effective conservation strategies. In this study, we employed the MaxEnt model to assess the potential habitats of Pieridae under different climatic conditions. The current study suggests that most Pieridae species’ suitable habitats are likely to decrease in response to global warming conditions. In contrast, some species showed an increase in suitable habitats. Furthermore, this study revealed that Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae have uneven geographical distribution patterns. Therefore, it is imperative to implement conservation strategies based on systematic conservation plans. This approach involves the identification of priority conservation areas by integrating butterfly diversity data with currently used flora and fauna2,64,82,86. To mitigate habitat contraction concerns, enhancing habitat connectivity and implementing ongoing population monitoring are crucial. Additionally, it is important to track population trends regularly and identify key natural and anthropogenic threats3,6,87. Owing to climate change, most Pieridae species would face substantial habitat reduction in the future, leading to an increased risk of local extinction. Surveys and research on the distribution patterns of Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae are crucial for identifying viable refugia or ex-situ restoration sites that can accommodate them. Prior to selecting refugia sites and establishing biodiversity reserves, it is important to conduct surveys on vegetation and food plants to guarantee the inclusion of optimal vegetation types. These measures will enhance the long-term survival of Pieridae.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined the geographic distribution patterns of Pieridae (Pierinae, Coliadinae, and Dismorphiinae) in mainland China and the relationship between their species richness and environmental variables. Pierinae and Coliadinae are primarily distributed in the southern part of the study, while Dismorphiinae is mainly located in the west-central and northeastern parts. Pierinae and Coliadinae flourished over a wider range of elevations in open areas with warmer and humid climates. In contrast, Dismorphiinae is comparatively restricted to a narrow elevation range in forested habitats with cooler and drier climates. We used the MaxEnt model to predict the potential suitable habitats for each subfamily based on their corresponding six major bioclimatic factors. From the LIG to LGM, the overall number of highly suitable habitats for each subfamily has increased. At least 13 Pierinae and 4 Coliadinae species experienced contraction in highly suitable habitats, while all species of Dismorphiinae showed expansion. From the LGM to Current period, the overall highly suitable habitats for Pierinae and Coliadinae have expanded, but those for Dismorphiinae have decreased. Overall, 20 Pierinae, 6 Coliadinae, and 1 Dismorphiinae species lost highly suitable habitat. The simulation results in global warming scenarios revealed a reduction in Pieridae’s highly suitable habitats due to rising temperatures. At least 37 Pierinae, 14 Coliadinae, and all Dismorphiinae species are projected to experience shrinkage in highly suitable habitats, leading to a decrease in species richness across the research zone. To conserve the diversity of Pieridae in the study area, it is crucial to enhance habitat connectivity and conduct regular species monitoring to obtain population trend information, mitigate the impact of climate change, and identify natural and anthropogenic threats. The current study provides valuable insights into Pieridae’s ecological requirements and future prospects in the face of climate change.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from both corresponding authors.

References

Wang, W. L. et al. Butterfly Conservation in China: From Science to Action. Insects 11, 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11100661 (2020).

Thomas, J. Monitoring change in the abundance and distribution of insects using butterflies and other indicator groups. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B. 360, 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1585 (2005).

Yu, X. T. et al. Species richness of papilionidae butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in the Hengduan mountains and its future shifts under climate change. Insects 14, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14030259 (2023).

Min, W. et al. Species diversity of butterflies in Shimentai nature Reserve, Guangdong. Biodiv Sci. 11, 441–453. https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2003052 (2003).

Pollard, E. Temperature, rainfall and butterfly numbers. J. Appl. Ecol. 25, 819–828. https://doi.org/10.2307/2403748 (1988).

Svancara, L., Abatzoglou, J. & Waterbury, B. Modeling current and future potential distributions of milkweeds and the monarch butterfly in Idaho. Front. ecol. evol. 7, 168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00168 (2019).

Minter, M. et al. Past, current, and potential future distributions of unique genetic diversity in a cold-adapted mountain butterfly. Ecol. Evol. 10, 11155–11168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6755 (2020).

Parmesan, C. Influences of species, latitudes and methodologies on estimates of phenological response to global warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 13, 1860–1872. (2007).

Gibbs, M., Wiklund, C. & Van Dyck, H. Temperature, rainfall and butterfly morphology: does life history theory match the observed pattern? Ecography 34, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06573.x (2010).

Bartonova, A. et al. Range dynamics of palaearctic steppe species under glacial cycles: the phylogeography of Proterebia Afra (Lepidoptera: nymphalidae: Satyrinae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 125, 867–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/bly136 (2018).

Taberlet, P., Fumagalli, L., Wust-Saucy, A. G. & Cosson, J. F. Comparative phylogeography and postglacial colonization routes in Europe. Mol. Ecol. 7, 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00289.x (2002).

Schoville, S., Stuckey, M. & Roderick, G. Pleistocene origin and population history of a neoendemic alpine butterfly. Mol. Ecol. 20, 1233–1247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05003.x (2011).

Sherpa, S. et al. Population decline at distribution margins: assessing extinction risk in the last glacial relictual but still functional metapopulation of a European butterfly. Divers. Distrib. 28, 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13460 (2022).

Kebaili, C., Sherpa, S., Rioux, D. & Després, L. Demographic inferences and Climatic niche modelling shed light on the evolutionary history of the emblematic cold-adapted Apollo butterfly at regional scale. Mol. Ecol. 31, 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16244 (2021).

Kumar, P. Assessment of impact of climate change on Rhododendrons in Sikkim Himalayas using maxent modelling: limitations and challenges. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 1251–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-012-0279-1 (2012).

Wu, C. S. & Hsu, Y. F. Butterflies of ChinaVol. 41442–2036 (The Straits Publishing & Distributing Group, 2017).

Simon, L. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. Vol. 1, 943Princeton university, Academic Press, (2013).

Powell, J. A., Resh, V. H. & Cardé, R. T. Lepidoptera. In Encyclopedia of Insects 2nd edn (Academic, 2009).

Vane-Wright, D. & de Jong, R. The butterflies of sulawesi: annotated checklist for a critical Island fauna. Zool. Verh Leiden. 343, 3–267 (2003).

Ding, C. & Zhang, Y. L. Phylogenetic relationships of Pieridae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in China based on seven gene fragments: phylogenetic relationships of Pieridae. Entomol. Sci. 20, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ens.12214 (2016).

Opler, P. A. A Field Guide To Western Butterflies 2nd edn (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998).

Brock, J. P. & Kaufman, K. Kaufman Field Guide To Butterflies of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003).

Shapiro, A. M. The biology and zoogeography of the legume-feeding Patagonian-Fuegian white butterfly Tatochila Theodice (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 251–260 (1991).

Shapiro, A. M., Forister, M. L. & Fordyce, J. A. Extreme high-altitude Asian and Andean Pierid butterflies are not each others’ closest relatives. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 39, 137–142 (2007).

Shapiro, A. M. Behavioral and ecological observations of Peruvian High-Andean Pierid butterflies (Lepidoptera). Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 20, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650528509360 (1985).

Shapiro, A. M. Developmental and phenotypic responses to photoperiod and temperature in an Equatorial montane butterfly, Tatochila xanthodice (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Biotropica 297–301. https://doi.org/10.2307/2387682 (1978).

Tshikolovets, V. V., Yakovlev, R. V. & Bálint, Z. The Butterflies of Mongolia (Tshikolovets, 2009).

Tshikolovets, V. V., Yakovlev, R. V. & Kosterin, O. E. The Butterflies of Altai, Sayans and Tuva (Tshikolovets, 2009). (South Siberia.

Laiho, J. & Ståhls, G. DNA barcodes identify central Asian Colias butterflies (Lepidoptera, Pieridae). Zookeys 30, 175–196. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.365.5879 (2013).

Yata, O. Butterflies of the South East Asian IslandsVol. 3 (Plapac Co. Ltd., 1985).

Leong, J. V. et al. Around the world in 26 million years: diversification and biogeography of Pantropical Grass-Yellow Eurema butterflies (Pieridae: Coliadinae). J. Biogeogr. 52, e15107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.15107 (2025).

Lukhtanov, V. A. Karyotype evolution and systematics of higher taxa of Pieridae (Lepidoptera) of the world. Ent Obozr. 70, 619–636 (1991).

Lamas, G. Twenty-five new Neotropical dismorphiinae (Lepidoptera-Pieridae). Rev. Peru Entomol. 44, 17–36 (2004).

Soberón, J. M., Llorente, J. B. & Oñate, L. The use of specimen-label databases for conservation purposes: an example using Mexican papilionid and Pierid butterflies. Biodivers. Conserv. 9, 1441–1466. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008987010383 (2000).

Zheng, P. China’s Geography142 (China Intercontinental, 2010).

Machine, W. Regions of Chinese food-styles/flavors of cooking. (2024). https://web.archive.org/web/20090416203009/http://www.kas.ku.edu:80/service-learning/projects/chinese_food/regional_cuisine. html.

Zhu, H. The tropical forests of Southern China and conservation of biodiversity. Bot. Rev. 83, 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Macro-evolutionary dynamics dominated by dispersal promote the formation of regional biodiversity hotspot‐insights from hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) in South China. Divers. Distrib. 31, e13916. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13916 (2025).

Forti, L. R. & Szabo, J. K. The iNaturalist platform as a source of data to study amphibians in Brazil. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 95, e20220828. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202320220828 (2023).

Su, J. et al. The distribution pattern and species richness of scorpionflies (Mecoptera: Panorpidae). Insects 14, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14040332 (2023).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km Spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Chen, Y., Guo, D., Cao, W. & Li, Y. Changes in net primary productivity and factor detection in china’s yellow river basin from 2000 to 2019. Remote Sens. 15, 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15112798 (2023).

Bai, W. et al. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal variation of vegetation NPP in Daning river basin and its driving forces. Int. J. Remote Sens. 44, 6194–6218. (2023).

Wei, T. et al. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 56, e24 (2017).

Moss, R. et al. Towards New Scenarios for Analysis of Emissions, Climate Change, Impacts, and Response Strategies: IPCC Expert Meeting Report (Noordwijkerhout). http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/supporting-material/expert-meeting-ts-scenarios.pdf.IP (2008) .

John, W. et al. Report of 2.6 Versus 2.9 Watts/m2 RCPP Evaluation Panel (University of Maryland, Joint Global Change Research Institute, 2009).

Vilela, B., Villalobos, F. & LetsR A new R package for data handling and analysis in macroecology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 1229–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12401 (2015).

Santana, P. A. Jr, Kumar, L., Da Silva, R. S., Pereira, J. L. & Picanço, M. C. Assessing the impact of climate change on the worldwide distribution of Dalbulus Maidis (DeLong) using maxent. Pest Manag. Sci. 75, 2706–2715. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5379 (2019).

Wei, J., Peng, L., He, Z., Lu, Y. & Wang, F. Potential distribution of two invasive pineapple pests under climate change. Pest Manag. Sci. 76, 1652–1663. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5684 (2020).

Warren, D. L., Wright, A. N., Seifert, S. N. & Shaffer, H. B. Incorporating model complexity and Spatial sampling bias into ecological niche models of climate change risks faced by 90 California vertebrate species of concern. Divers. Distrib. 20, 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12160 (2014).

Zhou, B. J., Ma, C. L., Gao, C., Han, D. N. & Chai, Y. Impacts of climate change on species distribution patterns of Polyspora sweet in China. Ecol. Evol. 12, e9516. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9516 (2022).

Yang, X., Kushwaha, S., Saran, S., Xu, J. & Roy, P. Maxent modeling for predicting the potential distribution of medicinal plant, Justicia Adhatoda L. in lesser Himalayan foothills. Ecol. Eng. 51, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.12.004 (2013).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x (2006).

Hijmans, R. J. & Elith, J. Spatial distribution models. Vol. 10, (2019).

Zhang, X. F., Nizamani, M. M., Jiang, C., Fang, F. Z. & Zhao, K. K. Potential planting regions of Pterocarpus Santalinus (Fabaceae) under current and future climate in China based on maxent modeling. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11409. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11409 (2024).

Lu, S. et al. Patterns of tree species richness in Southwest China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-08872-y (2021).

Xie, D. et al. Diversity of higher plants in China. J. Syst. Evol. 59, 1111–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12758 (2021).

Ômura, H. Plant secondary metabolites in host selection of butterfly. In Chemical Ecology of Insects. 3–27 (CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, (2018).

Castro-Gerardino, D. J. & Llorente-Bousquets, J. Comparative exploration of antennae in Pseudopontia, and antennal clubs of the tribes leptideini and dismorphiini (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Zootaxa 4347, 401–445 (2017).

Scott, J. A. The Butterflies of North America: A Natural History and Field Guide584 (Stanford University Press, 1992).

Shanks, K., Senthilarasu, S., ffrench-Constant, R. H. & Mallick, T. K. White butterflies as solar photovoltaic concentrators. Sci. Rep. 5, 12267. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12267 (2015).

Bladon, A. J. et al. How butterflies keep their cool: physical and ecological traits influence thermoregulatory ability and population trends. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 2440–2450. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13319 (2020).

Lamas, G. The dismorphiinae (Pieridae) of Mexico, central America and the Antilles. Mexi Soc. Lepi. 5, 3–37 (1979).

Hill, G. M., Kawahara, A. Y., Daniels, J. C., Bateman, C. C. & Scheffers, B. R. Climate change effects on animal ecology: butterflies and moths as a case study. Biol. Rev. 96, 2113–2126. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12746 (2021).

Oberhauser, K. & Peterson, A. Modelling current and future potential wintering distributions of Eastern North American monarch butterflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 14063–14068. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2331584100 (2003).

Zavaleta, E. S., Shaw, M. R., Chiariello, N. R., Mooney, H. A. & Field, C. B. Additive effects of simulated climate changes, elevated CO2, and nitrogen deposition on grassland diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 7650–7654. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0932734100 (2003).

Trotter, R. T., Cobb, N. S. & Whitham, T. G. Arthropod community diversity and trophic structure: a comparison between extremes of plant stress. Ecol. Entomol. 33, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2007.00941.x (2008).

Kishimoto-Yamada, K. & Itioka, T. Consequences of a severe drought associated with an El Niño-Southern Oscillation on a light-attracted leaf-beetle (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) assemblage in Borneo. J. Trop. Ecol. 24, 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467408004811 (2008).

Nielsen, E. T. & Nielsen, H. T. Temperatures preferred by the Pierid Ascia Monuste L. Ecology 40, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.2307/1930027 (1959).

Advani, N. K., Parmesan, C. & Singer, M. C. Takeoff temperatures in Melitaea Cinxia butterflies from latitudinal and elevational range limits: A potential adaptation to solar irradiance. Ecol. Entomol. 44, 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12714 (2019).

Hayes, M. P., Hitchcock, G. E., Knock, R. I., Lucas, C. B. H. & Turner, E. C. Temperature and territoriality in the Duke of Burgundy butterfly, Hamearis Lucina. J. Insect Conserv. 23, 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-019-00166-6 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Greater impacts from an extreme cold spell on tropical than temperate butterflies in Southern China. Ecosphere 7, e01315. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1315 (2016).

Ehrlich, P. R. et al. Extinction, reduction, stability and increase: the responses of checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas) populations to the California drought. Oecologia 46, 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00346973 (1980).

Huntley, B. et al. Explaining patterns of avian diversity and endemicity: climate and biomes of Southern Africa over the last 140,000 years. J. Biogeogr. 43, 874–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12714 (2016).

Alves, W. F. et al. Connectivity and climate influence diversity–stability relationships across Spatial scales in European butterfly metacommunities. Glob Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13896 (2024).

Chowdhury, S., Fuller, R. A., Dingle, H., Chapman, J. W. & Zalucki, M. P. Migration in butterflies: a global overview. Biol. Rev. 96, 1462–1483. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12714 (2021).

Kühne, G., Kosuch, J., Hochkirch, A. & Schmitt, T. Extra-Mediterranean glacial refugia in a mediterranean faunal element: the phylogeography of the chalk-hill blue Polyommatus Coridon (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae). Sci. Rep. 7, 43533. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43533 (2017).

Habel, J. C., Lens, L., Rödder, D. & Schmitt, T. From Africa to Europe and back: refugia and range shifts cause high genetic differentiation in the marbled white butterfly Melanargia Galathea. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-215 (2011).

Foster, P. The potential negative impacts of global climate change on tropical montane cloud forests. Earth Sci. Rev. 55, 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-8252(01)00056-3 (2001).

Cannone, N., Sgorbati, S. & Guglielmin, M. Unexpected impacts of climate change on alpine vegetation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 360–364. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295 (2007).

Wilson, R. J. et al. Changes to the elevational limits and extent of species ranges associated with climate change. Ecol. lett. 8, 1138–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00824.x (2005).

Liang, Q. et al. Shifts in plant distributions in response to climate warming in a biodiversity hotspot, the Hengduan mountains. J. Biogeogr. 45, 1334–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13229 (2018).

Taheri, S., Naimi, B., Rahbek, C. & Araújo, M. B. Improvements in reports of species redistribution under climate change are required. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe1110. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe1110 (2021).

Hu, R. et al. Shifts in bird ranges and conservation priorities in China under climate change. PLoS One. 15, e0240225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240225 (2020).

Lamsal, P., Kumar, L., Aryal, A. & Atreya, K. Future climate and habitat distribution of Himalayan musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster). Ecol. Inf. 44, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2018.02.004 (2018).

Yang, F., Hu, J. & Wu, R. Combining endangered plants and animals as surrogates to identify priority conservation areas in Yunnan, China. Sci. Rep. 6, 30753. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30753 (2016).

Ma, F. Z. et al. Progress in construction of China butterfly diversity observation network (China BON-Butterflies). J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 34, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.11934/j.issn.1673-4831.2018.01.004 (2018).

Chamberlain, S., Barve, V., Mcglinn, D., Oldoni, D., Desmet, P., Geffert, L., & Ram, K. rgbif: Interface to the global biodiversity informationfacility API. R package version 3.7.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgbif, (2022).

Barve, V. & Hart, E. rinat: Access ‘iNaturalist’ Data Through APIs. R package version 0.1.9. https://docs.ropensci.org/rinat/ (2025)

Maclean, I. M. D. & Wilson, R. J. Recent ecological responses to climate change support predictions of high extinction risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108,12337–12342. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017352108 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Rehan Zafar for providing invaluable guidance in the analysis of this study. We also thank Dr. Hashmat Khan and Dr. Haroon Khan for their thoughtful review and constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32471563).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. and Y.H: Conceptualization; R.H, Y.H, L.F, A.R, and P.M: methodology and experiments; R.H. and Y.H: data analysis; R.H: writing—original draft preparation; Y.H, L.F, and A.R: writing—review and editing; R.H: visualization; L.X. and Y.H: supervision; L.X: project administration; L.X: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussain, R., Miao, P., Rehman, A. et al. Species richness and Spatial distribution of three Pieridae subfamilies across mainland China under past and future climates. Sci Rep 15, 45685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21555-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21555-9