Abstract

Paleogenomics has recently expanded its applications, including studies on plant remains to trace evolution and domestication. However, recovering ancient DNA (aDNA) from archaeobotanical remains is challenging due to the highly fragmented nature of endogenous aDNA, low copy numbers and inhibitors that hinder further manipulation and analysis. In this study, we explored the application of a reagent optimized against soil inhibitors, typically used in sediment DNA extraction, coupled with an aDNA-specific silica binding step, to improve and maximize the recovery of processable aDNA. Ancient grape pips were used as starting material. The approach was evaluated in two archaeological contexts, assessing the suitability of extracts for downstream processing, including NGS library production and sequencing. In conclusion, we demonstrated the protocol was effective in recovering aDNA, achieving higher yields and more consistent performance across sites compared to previous extraction methods. It significantly improved the library production step, particularly in challenging sites. Finally, we have shown it successfully allowed to incorporate into sequencing libraries the highly fragmented and damaged endogenous aDNA from ancient samples, while preserving read yield, library complexity and other sequencing metrics. Future studies on historical and ancient plant remains will benefit from these advancements in high-quality aDNA recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Paleogenomics, the study of ancient genomes, has emerged as a crucial field at the intersection of evolutionary biology, archaeology, and molecular genetics. By extracting and analysing DNA from ancient biological remains (known as ancient DNA or aDNA), researchers can trace the genetic history of ancient populations, uncover extinct species, and gain insights into past ecosystems. The sequencing of ancient genomes has illuminated patterns of human migration1,2, admixture3, and extinction4, and is reshaping our understanding of evolution and adaptation5. While most studies have focused on vertebrates, particularly humans, fewer have concentrated on plant remains6,7. Despite that, paleogenomic methods have also proven highly effective in plants, enhancing our understanding of plant evolution and enabling the investigation of key bio-cultural processes, such as domestication, by supporting population genetic results8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Moreover, comparisons of ancient and modern plant species have improved our understanding of ecological and environmental history, reviving lost biodiversity16,17,18 and contributing to the identification of genetic traits essential for crop resilience, disease resistance and nutritional value19,20,21.

Advances in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have significantly expanded the applications of paleogenomics. While Sanger sequencing required longer and intact DNA fragments, recent developments in sequencing techniques have enabled researchers to also exploit highly fragmented aDNA in their studies22,23. Additionally, innovative strategies such as the establishment of specialized aDNA laboratories and pipelines, single-stranded library preparation methods minimizing the loss of short and damaged DNA, enrichment in endogenous aDNA by target capture hybridization-based approaches and non-conventional bioinformatics tools have enabled researchers to overcome many challenges in the field24,25,26,27. However, since aDNA in plant remains is typically highly degraded and present in low copy numbers, the development of highly efficient, dedicated DNA extraction methods, optimized to recover short DNA fragments while minimizing contamination, remains crucial. Interestingly, the endogenous DNA recovered from ancient remains exhibits some specificities. It is marked by an increased occurrence of purines (adenine and guanine residues) near strand breaks, likely due to DNA depurination28. Additionally it shows a higher frequency of cytosine-to-thymine misincorporations close to the ends of DNA fragments, probably caused by deamination in the single-stranded DNA overhangs29. These characteristic damage patterns can, in turn, be used to authenticate aDNA30,31.

In vertebrates, bones are typically the most abundant tissue occurring in ancient remains, and DNA extraction protocols from bones are well standardized and established. Most protocols make use of silica, either in solution or column, to capture short, highly fragmented aDNA32,33,34,35,36,37. In contrast, archaeobotanical remains can include a wide range of macrofossil tissue types, such as maize cobs, cereal seeds, fruit fragments, needles, sunflower heads, twigs, and hardwood, with seeds and hardwood samples being the most represented ones17,38,39,40,41. A few extraction protocols have been tested and compared, often using ancient grape seeds as common starting material9,20,42,43,44. In modern samples, plant DNA extraction is complicated by the presence of polyphenols, sugars and other secondary tissue-specific metabolites, that can affect downstream enzymatic reactions. In archaeological samples, humic acids from sediments, for example, are often co-extracted with DNA, inhibiting downstream analysis45,46. Additionally, plant remains from archaeological context are often charred, containing scarce amounts of exploitable endogenous DNA47,48. Due to these various challenges, no standard protocol for plant aDNA extraction has been established, and pilot studies are needed to determine the most suitable extraction reagents depending on sample types10,40,49.

Most protocols for aDNA extraction have been adapted from those originally developed for fresh tissues, with modifications aimed at improving the recovery of low-quality and highly fragmented DNA. One of the most widely used methods for DNA extraction from fresh plant tissues is based on cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)44, a reagent used to precipitate polysaccharides. This protocol has also been applied in aDNA research50,51. Wales et al.42 compared it with the standard bone aDNA extraction protocol used for vertebrates33 as well as with another protocol that uses a similar digestion buffer (including sodium dodecyl-sulfate (SDS), proteinase K, and dithiothreitol (DTT)) followed by classical phenol-chloroform extraction, as originally optimized for hairs52. According to their study, the latter outperformed the others, providing higher DNA yield and fewer inhibitors. An updated version of this method, which includes a silica purification step for the recovery of ultrashort DNA, has also been proposed53. Finally, commercial kits, such as the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), have been also applied and compared for aDNA recovery from ancient plant remains, generally showing lower efficiency13,42,54.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of sediments, also known as bulk sedaDNA, offers a novel approach for retrieving and analysing also ancient plant genomes (either partial or whole) as an alternative to more traditional paleogenomics. This approach relies on the simultaneous analysis of all organismal DNA from sediments, providing a comprehensive understanding of past environments55,56. In sedimentary aDNA field, a major challenge is the co-extraction of humic acids from soil, which can negatively impact enzymatic reactions and hinder further analysis45,46. A variety of methods have been explored for aDNA extraction from sediments, including the use of reagents developed for modern DNA extraction from soil, eventually combined with classical silica-based strategies to recover and concentrate highly degraded aDNA. Recently the use of the inhibitor-removal commercial buffer Power Beads Solution (Qiagen)42,57 followed by a silica-based aDNA purification strategy34,58 has proven effective in eliminating soil co-extracted inhibitors, while simultaneously yielding appropriate amounts of aDNA59. However, this protocol has only been applied on sediments thus far, while it was never tested to extract DNA directly from plant macrofossils.

In this study, we compared the sediment-optimized extraction method to those currently used for aDNA extraction from plant remains, including the phenol-chloroform protocol52, the CTAB-based protocol49, and the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit. Ancient waterlogged grape seeds were used as starting material, to facilitate comparisons. The primary objective was to carefully evaluate plant aDNA extraction using the sediment-optimized protocol. The method was assessed based on its efficiency in recovering aDNA, considering two different archaeological contexts. Additionally, we tested the suitability of the extracts for downstream processing and NGS sequencing.

Materials and methods

Archaeological plant remains

The study analyzed 84 ancient grapevine seeds, sourced from two excavation projects from two archaeological sites, as detailed in Table 1. Forty-five seeds were excavated from the Nogara site in the Veneto region of Italy, in Verona province (45° 10’ 45’’ N; 11° 03’ 32’’ E). Human settlement at this site is dated 8th −11th century CE. Seeds were retrieved from five distinct stratigraphic units (US 3024, US 3025, US 3028, US 3041, US 3045 and US 7012), indicating their usage, likely, for consumption.

Additionally, 39 grapevine seeds were sourced from the medieval site of Cologna Veneta, also located in the Veneto region and Verona Province (45° 18’ 35’’ N; 11° 23’ 0’’ E). This site is dated earlier than 13th century CE, and the seeds were recovered from two distinct stratigraphic units (US 341 and US 383). Large accumulation of remains at this site suggests connection to handcraft activities, making use of grape seeds, or winemaking activities.

More information on the sites and seed datation is available in the related sections, in the Supplementary Materials and Methods in the Supplementary Information online.

DNA extraction

All analyses were conducted in a dedicated ancient DNA (aDNA) laboratory at the University of Bologna (Department of Cultural Heritage, Campus of Ravenna), adhering to stringent standards established in the field24,27,60.

We mainly focused on well preserved waterlogged remains, which are more likely to contain DNA compared to charred samples. No charred samples were used here. Remains were selected based on their superficial integrity, according to a preliminary microscopic analysis. Fragmented and broken seeds were not used in this study. Contaminants on exterior surfaces were removed with sterile water and tools under microscope. Then seeds were subjected to a 20-minute UV treatment for surface decontamination before being extracted.

DNA extraction was performed using four different protocols. The extraction methods used in this work are listed in Table 2 and comprehensive protocols with all details and modifications are provided in the related Supplementary Materials and Methods section in the Supplementary Information online.

Briefly, to obtain a finer powder, all remains were first fragmented using a Dremel Fortiflex 9100 drill adapted with a 1.3 mm diameter drill bit, at a reduced speed of approximately 100 RPM, to minimize heat damage of DNA. Moreover, tweezers were used to block the sample. This approach proved more effective than grinding these types of samples with mortar and pestle. Blank controls were incorporated during the extraction process to ensure the absence of environmental contamination. A method originally developed on soil samples was implemented here on macrofossils (named Silica-Power Beads DNA Extraction - S-PDE method), based on previous protocols34,58. In this study 8 samples were extracted by using the Phe-chloroform (Phe-chl), 25 samples were extracted with the CTAB method, and 21 were extracted with the DNeasy extraction methods respectively, while the S-PDE method was applied all-together to 30 samples. After DNA extraction 1 µL aliquot of each extract was used for DNA quantification via fluorometric analysis, using the Qubit 2.0 High Sensitivity assay. Weights were only available for pips extracted with CTAB and DNeasy methods, since a weight balance was not available in the aDNA facility at the time of S-PDE extraction. We evaluated possible biases in DNA yield comparison due to no DNA yield normalization to pips weight by using available weight information. According to our data lack of weight normalization did not significantly affect DNA extraction comparison results (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Library production, indexing and evaluation

Library production from degraded aDNA is considered more challenging, due to low amounts of input DNA, short lengths of the DNA fragments, hydrolytic deamination of cytosine and other chemical damages. Several studies have aimed to improve library preparation from aDNA, by minimising template loss or maximising endogenous DNA inclusion into the library (reviewed by Orlando and colleagues61. Among others, one widely used strategy is to use single-stranded DNA as starting material (first introduced by Gansauge and Meyer26, which theoretically allows for the recovery of all DNA molecules in a sample.

A recent optimization of such strategy, based on the so-called Santa Cruz reaction (SCR), was used here for all samples62. The protocol uses a one-tube, one-reaction, single-stranded library preparation step that has been optimized for damaged and degraded DNA and was here slightly modified to avoid high final presence of adapter-dimers. Essentially, based on the amount of extracted DNA, we selected a lower concentration (one step below the recommended one in the original protocol) of splinted adapters and Extreme Thermostable Single-Stranded Binding Proteins (ET SSB, NEB). No enzymatic damage repair with the uracil-DNA-glycosylase enzyme was performed, to preserve the characteristic damage patterns of ancient DNA fragments. Before indexing, qPCR quantification was conducted to determine the appropriate number of amplification cycles for each library, minimizing the formation of PCR duplicates. Libraries were then double indexed using AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Invitrogen), and purified with SPRI beads at 1x concentration. The purified products, including samples and negative controls, were analyzed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for qualitative and quantitative assessment. Libraries negative controls were processed along each batch of samples.

Library sequencing

Indexed libraries meeting the sequencing company’s required criteria of at least 5 nM concentration and with low dimer percentage (< 12%) were equimolarly pooled. The pooled sample was pre-checked, showing a final concentration of 34 nM and average size of 214 bp. Pool was paired-end sequenced (2 × 150 bp) on an Illumina NovaSeq X platform (300 cycles) at Macrogen to get roughly 2.7 Gbp of sequence for each library. Resulting reads were de-multiplexed at Macrogen and delivered. Raw sequencing data are available for download at SRA database in NCBI, under Bioproject PRJNA1196955 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1196955).

Reads analysis

The bioinformatics processing of the sequencing reads was based on the nf-core/eager pipeline v. 2.4.6, implemented in Nextflow63,64. The sequencing reads underwent pre-processing steps for quality control, adapter removal, and merging of paired-end reads. Reads shorter than 30 base pairs were discarded, and the remaining ones were aligned to the Vitis vinifera PN40024.T2T (v5) reference genome, to chloroplast (NC007957.1)65 and mitochondrial (NC_012119.1)66 genome (https://grapedia.org/files-download/)67 using the BWA aln algorithm68, applying parameters optimized for ancient DNA (-l 1024, -n 0.01, -o 2) as recommended by Schubert et al.69. To mitigate the effects of post-mortem DNA damage during genotyping, five nucleotides were trimmed from the terminal ends of all retained reads. Additionally, standard quality control filters were applied, retaining only reads with a mapping quality score ≥ 25 and a base quality score ≥ Q30. Duplicate reads were removed using the Dedup tool64. To assess the extent of potential microbial or environmental contamination we have performed taxonomic assignment of unmapped reads using Kraken2 v.3.1.370 using the PlusPFP-16 database and default settings. The resulting report was visualized in RStudio v. 2023.12.1(Build402) with ggplot2 (v. 3.5.1) as a pie chart showing classification percentages at the domain level.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0. We compared sample values across different methods and sites (or their interaction), including total DNA extraction yield in nanograms (ng), CT-values in qPCR, percentage of retained reads post filtering (filter retained reads) vs total reads, deduplicated mapped reads amounts, percentage of endogenous DNA content (defined as the mapped reads passed post filter divided by the total number of filtered reads before duplicate removal), library clonality (defined as ratio of duplicated reads to mapped reads passed post filter), percentage GC content, library complexity (percentage of distinct reads as measured by the preseq curve function), mean length of mapped reads, and damage parameter (percentage of C→T substitutions at the 5’ position). Normality assumptions were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Both parametric and non-parametric tests were employed, including Two-way ANOVA and Aligned Rank Transform ANOVA (ART ANOVA). Multiple comparisons were performed using the Tukey Test and size effect were estimated either as Eta-squared test or by calculating the Cohen’s d value. Correlations between variables were evaluated using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation tests. Two-sample comparisons were conducted using the T-test or Wilcoxon Test. All graphical representations were generated using the ggplot2 package in R68.

Results

Evaluation of DNA recovery

In total DNA was extracted from 84 ancient samples in this study, represented by grape seeds (Table 1). Thirty of these samples were extracted using a method originally optimized for soil samples (S-PDE). The results from this method were compared to those obtained using three alternative extraction methods, which we have named Phe-chl, CTAB and DNeasy (Table 2). These alternative methods were applied to 25 (CTAB), 21 (DNeasy) samples as well as 8 samples for Phe-chl. For each method, nearly half of the samples were selected from the Nogara archaeological site, and half from the Cologna Veneta site, allowing us to assess the extraction performance across different conservation contexts.

DNA yield for each method was estimated through fluorometric quantification of DNA concentration in the raw extracts and raw data were directly used for comparisons (see Materials and Methods section for further details).

The analysis revealed differences in DNA recovery rates among the four methods. Notably, no DNA was detected in any of the eight extracts obtained using the Phe-chl method (Supplementary Fig S2). The other three methods-CTAB, DNeasy and the soil-optimized S-PDE protocols-successfully recovered DNA, with the only exception of DNAeasy which failed to recover DNA for 2 samples (CL83_B and CL84_B) from Cologna Veneta site. Total DNA yields per seed were varying widely, ranging from 7.4 (sample CL85_B extracted by DNeasy) to 1,071 ng (sample CL1_C extracted by S-PDE, Supplementary Table S1 online). No contamination was observed in any of the blanks included in each extraction batch. Interestingly, DNA yields were higher on average for the CTAB and the S-PDE extraction protocols compared to the DNeasy kit extraction method but showed wider variability (95.21 ± 104 and 236.08 ± 212 respectively vs. 24.30 ± 18, Fig. 1a). Two-way ANOVA confirmed significant differences across methods (p-value = 7,68E-06, see Supplementary Table S2 online for the full statistical analysis). In particular, S-PDE, despite variability, yields significantly higher amounts of DNA both compared to the CTAB and DNeasy kit methods (p-values = 0,002 and 0.0000091, Tukey test, Supplementary Table S2 online). In contrast, CTAB, despite its large size effect, didn’t yield significantly higher DNA compared to DNeasy.

Comparison of the DNA yields for the different extraction methods. (a) Violin plot for DNA yield for all samples extracted using the CTAB (n = 25), the DNeasy kit method (n = 21) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 30). (b) Violin plot for DNA yields for samples from the Cologna Veneta archaeological site extracted using the CTAB (n = 11), the DNeasy kit method (n = 11) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 13). (c) Violin plot for DNA yields for samples from the Nogara archaeological site extracted using the CTAB (n = 14), the DNeasy kit method (n = 10) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 17). Differences between S-PDE/CTAB and S-PDE/DNeasy were significant (p = 0.002 and 0.0000091 respectively) when considering all samples (a). Differences between S-PDE/DNeasy were significant also at Cologna Veneta site (p = 0.00048).

The two-way ANOVA analysis indicated extraction method as the only overall significant factor across all extractions. When plotting samples separately according to the archaeological site for each method (Fig. 1b, c), we observed no significant differences in DNA yield for CTAB and S-PDE and only a small effect of reduction for the more ancient site Nogara was shown (Cohen’s d = −0.45 and − 0.39 respectively). On the opposite DNeasy extraction method showed a slightly significant increase in DNA yield in Nogara vs. Cologna Veneta (p-value = 0.04, t-test, and d = 0.94; Supplementary Table S2 online). This indicates that the DNeasy extraction method is likely more sensitive to differences across archaeological sites compared to the other methods.

In conclusion, the S-PDE method yielded significantly higher amounts of DNA compared to both CTAB and DNeasy commercial kit. Additionally, this method as well as CTAB, proved to be more consistent across different contexts/sites compared to the DNeasy extraction method.

NGS DNA library production

All extracts from S-PDE extractions were used for NGS DNA library production. For the other two extraction methods only a representative subset of eight samples was chosen for testing NGS library preparation efficiency, equally distributed across sites (Table 1).

After library preparation, quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to determine, based on the cycle threshold (CT) values (Supplementary Table S3 online), the minimum number of PCR cycles required to amplify and index each library to the appropriate level for subsequent sequencing. The qPCR results provide both a comparative assessment of the efficiency of the extracts for library production step and a relative quantification of the number of molecules in each library. For example, a one-cycle difference between the CT-values of two libraries indicates that the concentration of starting molecules is twice as high in the library with the lower-cycle count compared to the other62,69.

Libraries prepared from DNA extracted using the S-PDE-based protocol or DNeasy had, on average, lower CT values compared to libraries from DNA extracted with CTAB (Supplementary Fig. S3 online; in detail S-PDE: 9 to 23 cycles [average 17.53]; DNeasy: 14 to 23 cycles [average 18.63]; CTAB: 16 to 29 cycles [average 21.50]), indicating a higher number of DNA molecules in the libraries. Statistical analysis (Supplementary Table S2 online) showed that these differences in CT-values among methods were not significant, but method had a medium size effect (d = 0.07 Cohen test). On the contrary, a clearly significant effect of DNA extraction method on CT-values was observed when considering the two archaeological sites separately, which was site-dependent (p = 0.0051). Indeed, surprisingly, the CTAB extraction method yielded libraries with significantly higher average CT-values (indicative of lower DNA molecule amounts) but only in the more recent Cologna Veneta archaeological site, while at the Nogara site it produced libraries with significantly lower CT values (indicative of higher DNA molecule amounts) (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S2 online). Interestingly, for CTAB, CT values were in general positively correlated with DNA input (higher CT-values were found particularly in samples with higher DNA input), unlike the other two extraction methods, which showed no correlation or, as expected, a slight negative correlation between CT-values and DNA input (Supplementary Fig. S4 online). For the other two methods, lower average CT-values (higher DNA molecule amounts) were consistently observed, as expected, at the more recent Cologna Veneta archaeological site (Supplementary Fig. S3 online).

In total, we successfully produced 31 libraries from 46 DNA samples with CT values lower than the relative negative control in qPCR (Supplementary Table S3 online). Different efficiencies were observed with each DNA extraction method (Fig. 2a). The CTAB method successfully produced four libraries from eight DNA extracts (50% efficiency in library production) The DNeasy yielded five libraries from eight DNA extracts (62.5% efficiency in library production). In contrast, the S-PDE method produced 22 libraries from 30 DNA extracts (73.3% efficiency in library production). When comparing the methods, the S-PDE method demonstrated a superior efficiency in library preparation.

Efficiency in library production for the different extraction methods. (a) Yield rate of successful libraries for all samples extracted using the CTAB (n = 8), the DNeasy kit method (n = 8) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 30). (b) Yield rate of successful libraries for Cologna Veneta samples extracted using the CTAB (n = 4), the DNeasy kit method (n = 4) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 13). (c) Yield rate of successful libraries for Nogara samples extracted using the CTAB (n = 4), the DNeasy kit method (n = 4) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 17).

It is noteworthy that the efficiency in library production with the different methods varied importantly between the two archaeological sites. For example, at the Cologna Veneta archaeological site (Fig. 2b), the S-PDE extract outperformed the other extracts in library production. Among the thirteen initial samples, the S-PDE method produced eleven libraries (84.6%). The CTAB protocol did not yield any library at this site and the DNeasy method produced three libraries, from four samples (75%). In contrast, at the Nogara site (Fig. 2c), the CTAB method exhibited surprisingly higher efficiency in library production. Among the four CTAB extracts, four libraries were produced. The seventeen S-PDE extracts yielded eleven libraries (58.8%), while the DNeasy method from four starting samples showed lower efficiency, producing two libraries (50%).

In conclusion, the good performance of the S-PDE extracts in library preparation appears strongly linked to the method’s ability to produce more uniform extracts suitable for successful library production from the different environments.

NGS sequencing results

To further evaluate the aDNA recovered from the different DNA extraction methods and its efficient incorporation into sequencing libraries, selected libraries for each method (libraries with molarity higher than 5 nM and dimer percentage lower than 12% of the total library) were pooled equimolarly and subjected to Illumina sequencing. Summary sequencing metrics are provided in Table 3.

On average, 13,578,223 total reads per sample were obtained, ranging from 3,184,240 for sample CL164_C to 51,679,107 for sample CL7_C.

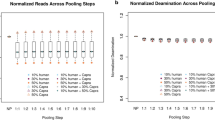

A comparative analysis was conducted among the different DNA extraction methods based on eight sequencing metrics parameters, using both parametric and non-parametric statistical analysis as appropriate (Supplementary Table S2 online). The DNA extraction method significantly affected the percentage of quality-filtered retained reads (p = 0.0102). In particular the S-PDE protocol showed significantly higher amounts of retained reads compared to DNeasy (p = 0.019) and a large effect, although not significant, was seen also vs. CTAB (Supplementary Fig. S5 online). Regarding the amount of deduplicated mapped reads (ranging from 7,213 to 444,122), no significant differences in yield were found for the S-PDE protocol compared to the other extraction methods (Supplementary Fig. S5 online). Site also was not significant, although we could see a large effect for site, with higher numbers of deduplicated mapped reads at the Cologna Veneta site compared to the Nogara site.

Endogenous DNA content varied across samples and extraction methods. The highest endogenous DNA content was found in a sample extracted with the S-PDE method (8.9% in sample CL164_C), while the highest content for the CTAB extraction method was 1.6% in sample NG35_A, and for DNeasy, it was 3.2% in sample CL107_B (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S5 online). Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences across the different DNA extraction methods or archaeological sites and a medium size-effect due to sites with higher percentage of endogenous DNA on average for the most recent Cologna Veneta site (in agreement with the greater number of mapped reads previously reported) compared to the Nogara site (2.22%±2.39 vs. 1.07%±0.74). A medium site-by-method effect was also found: focusing on the most ancient site, the CTAB and S-PDE methods provided the highest endogenous DNA content on average (1.27%±0.42 and 1.11%±0.81 respectively vs. 0.11% for DNeasy). We also examined library complexity and clonality to assess any putative negative effect of the DNA extraction method on library complexity. We found no significant differences across groups, but some effects due to methods leading to higher library complexity and reduced clonality for DNA extracts obtained using the S-PDE protocol were observed (Supplementary Fig. S5 online). Therefore, we concluded that the S-PDE protocol performs efficiently in terms of endogenous DNA retrieval and library complexity. The GC contents of mapped reads of libraries built from the DNA extracted with the three protocols were also not significantly affected, although a broader variability was found for the S-PDE method (Supplementary Fig. S5 online).

To better understand the origin of this variability, we also performed taxonomic assignment of unmapped reads in the attempt to reveal potential biological or environmental contaminations. The analysis did not indicate significant contamination from plant or microbial DNA; majority of reads were unclassified, with only a minor fraction assigned to the domains Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota (Supplementary Fig. S6 online).

Interestingly, the DNA extraction method had instead an impact on the mean fragment length of the libraries. For all three methods, mean read length was less than 100 base pairs, consistent with values expected for highly fragmented aDNA28 (Supplementary Fig. S7 online). Libraries built from CTAB DNA extracts had significantly average shorter reads compared to libraries from DNeasy and S-PDE DNA extracts (CTAB-DNeasy p = 4.02 e-05; CTAB-S-PDE p = 0.0325). However, the mean fragment size of libraries built from the S-PDE extracts was also significantly smaller compared to those built from DNeasy extracts (p = 0.0003275) (Fig. 3a and b). Notably, a difference in read length was also observed between the libraries from the two archaeological sites (Fig. 3c, d). Indeed, longer reads were recovered from the Cologna Veneta site compared to the Nogara site (Cologna Veneta-Nogara p = 0.00281), likely due to the different conservation conditions of the samples.

Comparison of mean length of mapped reads in libraries for the different extraction methods. (a) Histograms of mapped reads mean length for each library. Libraries are coloured according to the different extraction methods (b) Box-plot of mapped reads mean length for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the CTAB (n = 3), the DNeasy kit method (n = 3) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 18). (c) Box plot of mapped reads mean length for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the DNeasy kit method (n = 2) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 10) in the Cologna Veneta archaeological site. (d) Box-plot mapped reads mean length for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the CTAB (n = 3), the DNeasy kit method (n = 1) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 8) in the Nogara archaeological site. Differences between DNeasy-CTAB, S-PDE/CTAB, S-PDE/DNeasy were all significant (p = 4.02 e-05, 0.0325 and 0.0003275 respectively) when considering all samples (a). Differences between sites (b vs. c) were also significant (p = 0.0028).

We also analysed the frequency of DNA damage at the extremities of the reads, which can provide insights into the quality and properties of the recovered DNA. Previous ancient DNA studies have shown C→T and G > A substitutions at the 5’ and 3’ end of the reads as a typical pattern in ancient DNA28,29. All samples exhibited a percentage of C→T substitutions consistent with values expected for ancient samples. As expected, misincorporation was significantly higher for libraries prepared from the more ancient Nogara archaeological site (p = 0.0184) (Fig. 4b, c). Notably, the S-PDE extracts demonstrated a higher percentage of misincorporation in the recovered fragments, compared to the extracts obtained with other protocols (S-PDE-CTAB p = 0.0025732; S-PDE-DNeasy p = 0.0509454) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S8 online).

Probability of C→T misincorporation at the first and last positions of the fragments in the libraries obtained from DNA extracted using the different extraction methods. (a) Box-plot of the probability of C→T misincorporation for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the CTAB (n = 3), the DNeasy kit method (n = 3) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 18). (b) Box-plot of the probability of C→T misincorporation for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the DNeasy kit method (n = 2) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 10) in the Cologna Veneta archaeological site. (c) Box-plot of the probability of C→T misincorporation for libraries obtained from DNA extracts using the CTAB (n = 3), the DNeasy kit method (n = 1) and the S-PDE extraction method (n = 8) in the Nogara archaeological site. Differences between S-PDE/CTAB were significant (p = 0.00257) when considering all samples (a). Differences between sites (b vs. c) were also significant (p = 0.0279).

In aDNA research evolutionary questions are often investigated using genomic sequences from organelles like mitochondrial or chloroplast DNAs. Therefore, we investigated the ability of the S-PDE protocol to also retrieve these sequences. Our data demonstrate that the S-PDE protocol successfully retrieves these sequences too (Supplementary Fig. S9 online).

Altogether NGS sequencing of libraries indicates a high efficiency of the S-PDE protocol in recovering highly fragmented and damaged ancient DNA fragments, with no major biases in library production.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to evaluate a protocol originally developed for DNA extraction from soil sediments59 for aDNA extraction from botanical remains. Archaeobotanical remains are often associated with humic acids from soils, similarly as sediments, which can inhibit DNA extraction and subsequent analysis45,46. In this context, we specifically evaluated a modified extraction protocol that includes a reagent against soil inhibitors. We compared this approach with previously established protocols for plant aDNA extraction, including the phenol-chloroform method14,20,52, the CTAB protocol44, and a standard plant DNA extraction kit (DNeasy, Qiagen).

Ancient grape pips, which were also used in previous comparative tests, served as starting material for this study. Unfortunately, the previously reported Phe-chl high-performing protocol for grape pips52 was not successful in our hands, so we were unable to directly compare our results with this specific method. Notably, Phe-chl protocol has a significant drawback in that it relies on highly hazardous reagents that pose serious health risks73. Additionally, these reagents must be handled in fume hoods, which are often incompatible with the positive pressure systems required by fundamental guidelines for ancient DNA laboratories60. As for the other tested protocols, our results are consistent with previous findings from comparative studies. Total DNA yields per specimens were comparable to those reported in earlier work42 First, we confirmed that DNA extraction kits perform poorly for aDNA. Total DNA yield was lower when compared to both the CTAB plant protocol and the S-PDE extraction protocol. Furthermore, the DNA yield was varying significantly depending on the local context. In agreement with previous works, we can conclude that kits are not ideal and less recommended for aDNA studies42. Furthermore we showed that the S-PDE protocol yields significantly more DNA also compared to the classical CTAB protocol. A possible limitation in our analysis is the absence of normalization to seed weight, which remains pivotal for such comparative studies. Unfortunately, this was not feasible in our study due to technical reasons. However, we clearly showed no correlation between seed weight and yield on our samples, which indicates that aDNA yields in the different samples are likely more dependent on other aspects than weight mass, like sample preservation by instance, which is also consistent with previous findings74. Based on these observations we concluded that the absence of seed weight normalization did not significantly biased the study outcomes and conclusions remain reliable despite this limitation.

Since, total DNA yield in extracts from ancient specimens does not allow to discriminate between endogenous and exogenous DNA or to estimate the amount of co-extracted inhibitors and extracts processability, we proceeded to compare the protocols based on the preparation of genomic libraries for NGS sequencing. qPCR analysis, following adapters ligation, confirmed the results from fluorometric quantification, indicating that results were not biased by the quantification system or co-extracted compounds. However, the difference in CT values across samples was never significant when considering separately the different extraction methods. An expected negative correlation between the DNA extracts concentrations and the CT values in qPCR was found for DNeasy extracts, and this negative correlation was even more pronounced for the S-PDE extracts, suggesting an improved efficiency of this protocol in removing co-extracted inhibitors and enhancing sample processing. Surprisingly, for CTAB extracts, we observed an unexpected positive correlation (Supplementary Fig. S4 online). We thus hypothesized that, with CTAB protocol, DNA extracts with higher concentration also contain more DNA contaminants and enzyme inhibitors, which could hinder library preparation steps, such as adapter-splint ligation and amplification. Accordingly, a lower efficiency in library production was observed for the CTAB extracts when we further assessed the suitability of DNA extracts for subsequent enzymatic processing using the same ssDNA library protocol on all samples62. In conclusion, the S-PDE extracts proved to be the most suitable for further enzymatic processing, yielding the highest proportion of successful libraries.

Our results confirm previous preliminary findings about the advantage of using reagents optimized against soil co-extracted inhibitors. Wales and co-authors, in their study, also considered an extraction method under development for recovering aDNA from sediments42. Their protocol, similar to ours, included an inhibitor removal reagent from a soil-extraction kit, that they supposed could help to better manage humic-rich sediments. They demonstrated that this strategy allowed them to recover comparable amounts of aDNA, or in some cases, even higher yield, depending on specimens, compared to the best performing protocol52 in their hands. They concluded that the protocol might be particularly useful for samples from more contaminated sites. Since then, sediment-style extraction protocols have been further optimized to explore also aDNA in sediments55,57. Notably, the incorporation of a silica binding step-commonly used in aDNA protocols to mitigate DNA loss and efficiently recover short aDNA fragments34-following the usage of optimized reagents against soil co-extracted inhibitors, has favored their successful implementation in the sediment aDNA field58,59. Therefore, in this study, we sought to further expand the comparative testing of protocols for aDNA extraction in plants from macrofossils, by including also late improvements from sediments-style procedures. Based on our data, the newly optimized S-PDE protocol yielded higher amounts of total aDNA compared to other tested methods that was suitable for further processing.

To clarify the impact of the extraction protocols on library sequencing metrics and endogenous DNA content yield, similar to recent comparative studies on vertebrates35,75,76,we sequenced libraries produced with the S-PDE protocol along with some of the libraries produced from CTAB and DNeasy extracts. The libraries extracted with the S-PDE protocol yielded a significantly higher proportion of quality-filtered reads. For other parameters, the quality of the libraries appeared comparable across the different DNA extraction protocols, and no major issues were observed, including in terms of clonality and complexity. When comparing the average fragments sizes, we observed a cut-off size for the DNeasy kit, which recovered less efficiently fragments smaller than 65–70 bp. This result is expected, as the columns and reagent combinations used in the kit have been shown in the literature to result in the loss of shorter fragments, which do not efficiently bind to the kit’s columns78. Conversely, the S-PDE protocol, which includes an aDNA optimized silica binding step, demonstrated wider size range and a significantly improved cut-off size, allowing the recovery of smaller fragments compared to the DNeasy kit. Additionally, the percentage of C→T misincorporation in the sequenced reads was higher with the S-PDE aDNA extraction protocol compared to the other protocols. Finally, by mapping sequencing reads to the grape chloroplast and mitochondria, we also confirmed the suitability of the S-PDE protocol to recover also non-nuclear genomic DNA. Overall, the sequencing data demonstrate that the S-PDE protocol effectively maintains library complexity and recovers damaged and fragmented aDNA with good efficiency.

Some of the samples used in this study (e.g. CL7_C) showed relatively high amounts of DNA yield, which questioned their integrity and raised the possibility of environmental modern plant contamination or extraction of large amounts of exogenous DNA, e.g. microbial, a common issue in aDNA studies. Deep sequencing and especially hybridization capture are widely used as technical approaches following library preparation to overcome such environmental contaminations in aDNA studies, increasing the amount of endogenous aDNA. Still monitoring the level of sample contaminations is recommended. Also, extraction methods could be differently sensitive as concern contaminants. In our study, the authenticity of the obtained data was confirmed by the absence of contamination in the negative controls during extraction, the presence of characteristic damage patterns in sequenced libraries, and the short read length. Moreover, the analysis of unmapped sequencing reads did not reveal substantial contamination from plant or microbial DNA. Kraken2 results showed a predominance of unclassified reads, with only a small percentage taxonomically assigned to the domains Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota. Importantly we observed no differences across samples from the different extraction protocols.

A key aspect of the study was the comparison across different sites, which allowed us to better dissect the observed differences in the performance of the various aDNA extraction protocols and buffer the inherent environmental/micro-environmental variability that can severely affect outcomes of these studies. Specifically, we investigated whether the protocols performed differently in combination with specific archaeological contexts by considering two alternative sites-Cologna Veneta and Nogara-that date to different periods. We found that the aDNA yield from DNeasy extraction method was site-dependent, unlike the S-PDE and CTAB extraction protocols, that produced higher yield and more comparable results across sites. In terms of libraries, however, surprisingly, we observed a strong variable performance for CTAB extracts depending on the site. For example, despite good DNA yield from CTAB protocol at the Cologna Veneta archaeological site, no library could be built from CTAB DNA extracts. In contrast, at the Nogara site (which dates to a more ancient period), library production with CTAB extracts was more successful than with other protocols. Environmental factors such as soil pH, humic acid content, sediment texture and moisture, besides age may also contribute to site-dependent variability. The observation that more concentrated CTAB extracts were less efficient in DNA library production and amplification, raised also a concern about the CTAB protocol efficiency in removing co-extracted enzymatic inhibitors. Further site characterizations could aid potential explanations of the observed variability. Moreover, direct inhibition assays (e.g., spike-in controls or qPCR-based inhibition testing) would allow direct quantification of residual inhibitors in the different extracts and their impact on further processability of extracted DNA. So far, although the improved performance of S-PDE and DNeasy extracts in library production in challenging samples suggests more effective inhibitor removal, this interpretation remains speculative and should be further tested. Future studies should include dedicated aliquots and inhibition controls to directly test this hypothesis, as in Wales et al. (2014)42.

As conclusion, the incorporation of a soil reagent specifically optimized against soil co-extracted inhibitors, coupled with an aDNA-adapted silica binding step59 (slightly modified in this study, as detailed in the Materials and Methods section in the Supplementary Information online), proved advantageous compared to previously available aDNA extraction protocols for macrofossils. We demonstrated that this protocol significantly improved the library production process, particularly at certain sites, and allowed at the same time to recover highly fragmented and damaged aDNA, while preserving library complexity. Our results might be particularly relevant for challenging sites. Although this approach may be less necessary for other sites, it can provide a more uniform performance across different, previously untested sites.

Data availability

Data is provided either within the manuscript or available in Supplementary Information file online at Journal site or available in publicly available platforms. Raw sequence reads obtained from NGS sequencing was deposited as raw fastq files in the SRA database (Bioproject PRJNA1196955). BioProject and associated SRA metadata are available at [https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1196955?reviewer=57baaslmojdepgkv59q5kbg9c0] reviewer access link in read-only format for reviewers and are available to reviewers upon request. Data will be made publicly available upon publication.

References

Lazaridis, I. et al. A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia. Science 377, 940–951 (2022).

Fontani, F. et al. Bioarchaeological and paleogenomic profiling of the unusual neolithic burial from Grotta Di Pietra sant’angelo (Calabria, Italy). Sci. Rep. 13, 11978 (2023).

Skourtanioti, E. et al. Genomic history of neolithic to bronze age anatolia, Northern levant, and Southern Caucasus. Cell 181, 1158–1175e28 (2020).

Utzeri, V. J. et al. Ancient DNA re-opens the question of the phylogenetic position of the Sardinian Pika prolagus Sardus (Wagner, 1829), an extinct lagomorph. Sci. Rep. 13, 13635 (2023).

Marciniak, S. & Perry, G. H. Harnessing ancient genomes to study the history of human adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 659–674 (2017).

Gugerli, F., Parducci, L. & Petit, R. J. Ancient plant DNA: review and prospects. New Phytol. 166, 409–418 (2005).

Pont, C. et al. Paleogenomics: reconstruction of plant evolutionary trajectories from modern and ancient DNA. Genome Biol. 20, 29 (2019).

Mascher, M. et al. Genomic analysis of 6,000-year-old cultivated grain illuminates the domestication history of barley. Nat. Genet. 48, 1089–1093 (2016).

Ramos-Madrigal, J. et al. Genome sequence of a 5,310-Year-Old maize cob provides insights into the early stages of maize domestication. Curr. Biol. 26, 3195–3201 (2016).

Kistler, L. et al. Multiproxy evidence highlights a complex evolutionary legacy of maize in South America. Science 362, 1309–1313 (2018).

Scott, M. F. et al. A 3,000-year-old Egyptian emmer wheat genome reveals dispersal and domestication history. Nat. Plants. 5, 1120–1128 (2019).

Smith, O. et al. Ancient RNA from late pleistocene permafrost and historical Canids shows tissue-specific transcriptome survival. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000166 (2019).

Kistler, L. et al. Ancient plant genomics in Archaeology, Herbaria, and the environment. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 71, 605–629 (2020).

Ramos-Madrigal, J. et al. Palaeogenomic insights into the origins of French grapevine diversity. Nat. Plants. 5, 595–603 (2019).

Pérez-Escobar, O. A. et al. Genome sequencing of up to 6,000-year-old citrullus seeds reveals use of a bitter-fleshed species prior to watermelon domestication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac168 (2022).

Jaenicke-Després, V. et al. Early allelic selection in maize as revealed by ancient DNA. Science 302, 1206–1208 (2003).

Wagner, S. et al. High-throughput DNA sequencing of ancient wood. Mol. Ecol. 27, 1138–1154 (2018).

Wagner, S. et al. Tracking population structure and phenology through time using ancient genomes from waterlogged white oak wood. Mol. Ecol. 33, e16859 (2024).

Przelomska, N. A. S., Armstrong, C. G. & Kistler, L. Ancient plant DNA as a window into the cultural heritage and biodiversity of our food system. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8, 74 (2020).

Cohen, P. et al. Ancient DNA from a lost negev highlands desert grape reveals a late antiquity wine lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2213563120 (2023).

Meiri, M. & Bar-Oz, G. Unraveling the diversity and cultural heritage of fruit crops through paleogenomics. Trends Genet. 40, 398–409 (2024).

Briggs, A. W. & Heyn, P. Preparation of next-generation sequencing libraries from damaged DNA. In Ancient DNA Vol. 840 (eds Shapiro, B. & Hofreiter, M.) 143–154 (Humana, 2012).

Brown, T. A. et al. Recent advances in ancient DNA research and their implications for archaeobotany. Veget Hist. Archaeobot. 24, 207–214 (2015).

Cooper, A., Poinar, H. N. & Ancient, D. N. A. Do it right or not at all. Science 289, 1139–1139 (2000).

Ávila-Arcos, M. C. et al. Application and comparison of large-scale solution-based DNA capture-enrichment methods on ancient DNA. Sci. Rep. 1, 74 (2011).

Gansauge, M. T. & Meyer, M. Single-stranded DNA library Preparation for the sequencing of ancient or damaged DNA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 737–748 (2013).

Cilli, E. Archaeogenetics in Encyclopedia of Archaeology (eds Nikita, E. & Rehren, T. H. Elsevier). 2B, 1038-1047 (2024).

Briggs, A. W. et al. Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a neandertal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 14616–14621 (2007).

Brotherton, P. et al. Novel high-resolution characterization of ancient DNA reveals C > U-type base modification events as the sole cause of post mortem miscoding lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5717–5728 (2007).

Hofreiter, M. DNA sequences from multiple amplifications reveal artifacts induced by cytosine deamination in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4793–4799 (2001).

Jónsson, H., Ginolhac, A., Schubert, M., Johnson, P. L. F. & Orlando, L. mapDamage2.0: fast approximate bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 29, 1682–1684 (2013).

Yang, D. Y., Eng, B., Waye, J. S., Dudar, J. C. & Saunders, S. R. Improved DNA extraction from ancient bones using silica-based spin columns. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 105, 539–543 (1998).

Rohland, N. & Hofreiter, M. Comparison and optimization of ancient DNA extraction. BioTechniques 42, 343–352 (2007).

Dabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a middle pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, 15758–15763 (2013).

Gamba, C. et al. Comparing the performance of three ancient DNA extraction methods for high-throughput sequencing. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 459–469 (2016).

Rohland, N., Glocke, I., Aximu-Petri, A. & Meyer, M. Extraction of highly degraded DNA from ancient bones, teeth and sediments for high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 13, 2447–2461 (2018).

Puncher, G. N. et al. Comparison and optimization of genetic tools used for the identification of ancient fish remains recovered from archaeological excavations and museum collections in the mediterranean region. Intl J. Osteoarchaeology. 29, 365–376 (2019).

Kistler, L. Ancient DNA extraction from plants. In Ancient DNA Vol. 840 (eds Shapiro, B. & Hofreiter, M.) 71–79 (Humana, 2012).

Schmid, S. et al. Hy RAD -X, a versatile method combining exome capture and RAD sequencing to extract genomic information from ancient DNA. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 1374–1388 (2017).

Lendvay, B. et al. Improved recovery of ancient DNA from subfossil wood – application to the world’s oldest late glacial pine forest. New Phytol. 217, 1737–1748 (2018).

Schwörer, C., Leunda, M., Alvarez, N., Gugerli, F. & Sperisen, C. The untapped potential of macrofossils in ancient plant DNA research. New Phytol. 235, 391–401 (2022).

Wales, N., Andersen, K., Cappellini, E., Ávila-Arcos, M. C. & Gilbert, M. T. P. Optimization of DNA recovery and amplification from Non-Carbonized archaeobotanical remains. PLoS ONE. 9, e86827 (2014).

Wales, N. et al. The limits and potential of paleogenomic techniques for reconstructing grapevine domestication. J. Archaeol. Sci. 72, 57–70 (2016).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical. Bulletin. 19, 11-15 (1987).

Matheson, C. D., Gurney, C., Esau, N. & Lehto, R. Assessing PCR Inhibition from Humic Substances. (2010).

Oberreiter, V. et al. Maximizing efficiency in sedimentary ancient DNA analysis: a novel extract pooling approach. Sci. Rep. 14, 19388 (2024).

Bunning, S. L., Jones, G. & Brown, T. A. Next generation sequencing of DNA in 3300-year-old charred cereal grains. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 2780–2784 (2012).

Nistelberger, H. M., Smith, O., Wales, N., Star, B. & Boessenkool, S. The efficacy of high-throughput sequencing and target enrichment on charred archaeobotanical remains. Sci. Rep. 6, 37347 (2016).

Latorre, S. M., Lang, P. L. M., Burbano, H. A., Gutaker, R. M. & Isolation Library Preparation, and bioinformatic analysis of historical and ancient plant DNA. CP Plant. Biology. 5, e20121 (2020).

Japelaghi, R. H., Haddad, R. & Garoosi, G. A. Rapid and efficient isolation of High-Quality nucleic acids from plant tissues rich in polyphenols and polysaccharides. Mol. Biotechnol. 49, 129–137 (2011).

Palmer, S. A., Moore, J. D., Clapham, A. J., Rose, P. & Allaby, R. G. Archaeogenetic evidence of ancient Nubian barley evolution from six to Two-Row indicates local adaptation. PLoS ONE. 4, e6301 (2009).

Gilbert, M. T. P. et al. Ancient mitochondrial DNA from hair. Curr. Biol. 14, R463–R464 (2004).

Wales, N. & Kistler, L. Extraction of ancient DNA from plant remains. In Ancient DNA Vol. 1963 (eds Shapiro, B. et al.) 45–55 (Springer New York, 2019).

Bacilieri, R. et al. Potential of combining morphometry and ancient DNA information to investigate grapevine domestication. Veget Hist. Archaeobot. 26, 345–356 (2017).

Parducci, L. et al. Ancient plant DNA in lake sediments. New Phytol. 214, 924–942 (2017).

Alsos, I. G. et al. Plant DNA metabarcoding of lake sediments: how does it represent the contemporary vegetation. PLoS ONE. 13, e0195403 (2018).

Pedersen, M. W. et al. Postglacial viability and colonization in North america’s ice-free corridor. Nature 537, 45–49 (2016).

Hagan, R. W. et al. Comparison of extraction methods for recovering ancient microbial DNA from paleofeces. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 171, 275–284 (2020).

Rampelli, S. et al. Components of a neanderthal gut Microbiome recovered from fecal sediments from El salt. Commun. Biol. 4, 169 (2021).

Llamas, B. et al. From the field to the laboratory: controlling DNA contamination in human ancient DNA research in the high-throughput sequencing era. STAR: Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Res. 3, 1–14 (2017).

Orlando, L., Gilbert, M. T. P. & Willerslev, E. Reconstructing ancient genomes and epigenomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 395–408 (2015).

Kapp, J. D., Green, R. E. & Shapiro, B. A. Fast and efficient Single-stranded genomic library Preparation method optimized for ancient DNA. J. Hered. 112, 241–249 (2021).

Peltzer, A. et al. EAGER: efficient ancient genome reconstruction. Genome Biol. 17, 60 (2016).

Yates, J. A. et al. Reproducible, portable, and efficient ancient genome reconstruction with nf-core/eager. PeerJ 9, e10947 (2021).

Jansen, R. K. et al. Phylogenetic analyses of vitis (Vitaceae) based on complete Chloroplast genome sequences: effects of taxon sampling and phylogenetic methods on resolving relationships among Rosids. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 32 (2006).

Goremykin, V. V., Salamini, F., Velasco, R. & Viola, R. Mitochondrial DNA of vitis vinifera and the issue of rampant horizontal gene transfer. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 99–110 (2008).

Shi, X. et al. The complete reference genome for grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) genetics and breeding. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad061 (2023).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010).

Schubert, M. et al. Improving ancient DNA read mapping against modern reference genomes. BMC Genom. 13, 178 (2012).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 257 (2019).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. WIREs Computational Stats 3, 180–185 (2011).

Carøe, C. et al. Single-tube library Preparation for degraded DNA. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 410–419 (2018).

Molbert, N., Ghanavi, H. R., Johansson, T., Mostadius, M. & Hansson, M. C. An evaluation of DNA extraction methods on historical and roadkill mammalian specimen. Sci. Rep. 13, 13080 (2023).

Atmore, L. M. et al. Ancient DNA sequence quality is independent of fish bone weight. J. Arch. Sci. 149. 105703. (2023).

Marinček, P., Wagner, N. D. & Tomasello, S. Ancient DNA extraction methods for herbarium specimens: When is it worth the effort? Appl Plant Sci 10, e11477 (2022).

Nieves-Colón, M. A. et al. Comparison of two ancient DNA extraction protocols for skeletal remains from tropical environments. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 166, 824–836 (2018).

Glocke, I. & Meyer, M. Extending the spectrum of DNA sequences retrieved from ancient bones and teeth. Genome Res. 27, 1230–1237 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. Reactivation characteristics and hydrological inducing factors of a massive ancient landslide in the three Gorges Reservoir, China. Eng. Geol. 292, 106273 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. de Zuccato from “Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le province di Verona Rovigo e Vicenza” for providing some of the seeds used in the study and Dr Francesca Griggio at Centro Piattaforme Tecnologiche (CPT) at University of Verona for technical support and discussion.

Funding

This project was supported by “Fondazione Cariverona”, under the call “Bando Ricerca Scientifica di Eccellenza_2018” project “In Veronensium mensa. Food and Wine in ancient Verona – FaW” and under the call “Ricerca e Sviluppo 2022” project “Valutazione di selezioni di viti resistenti per la produzione viticola locale e sviluppo di nuovi processi di selezione assistita per le varietà del territorio” and by the MIUR Ministery, Italy under the call PRIN 2022, project “ArchaeoAdWines - Archaeology of Adriatic Wine” Code 20228C8EFW, PNRR, M4.C2.1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GB, EC, DB, DL and PB designed research; GB, EC performed research; AL, MM, AC, FF analysed data; DB, EC, DL, PB contributed reagents; FS, PB contributed materials; GB, DB, EC, FS wrote the paper; all authors reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolognesi, G., Latorre, A., Marini, M. et al. Optimizing ancient DNA recovery from archaeological plant seeds. Sci Rep 15, 36595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21743-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21743-7