Abstract

This article presents a novel augmented image encryption algorithm tailored for securing satellite images, addressing the critical need for robust protection of sensitive geographic data. Implementing Shannon’s principles of confusion and diffusion, the method begins by augmenting multiple plain images into a single large image, followed by a three-stage encryption process. Initially, the augmented image is separated into its three color channels, which are transformed into one-dimensional (1D) bit-streams, split and altered using the Gauss Circle map, and restructured via Fredkin Gates to enhance unpredictability. Subsequently, the bit-streams are converted into 1D bytes and \(2 \times 2\) matrices, processed through three systems incorporating hyperchaos-induced keys and dynamic Hill Cipher matrices for additional confusion and diffusion. The final stage combines these encrypted streams into one image while preserving the integrity of color data. The proposed method achieves strong security metrics, including an average Number of Pixels Change Rate (NPCR) of \(99.6115\%\), a Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) of \(31.71\%\), and high entropy values (e.g., 7.9989) for encrypted images, ensuring robust resistance to differential and statistical attacks. The encryption demonstrates computational efficiency with an encryption time of 0.2817s for \(256\times 256\) images and maintains a low Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) of 8.1 dB, reflecting effective data obfuscation. This multistage chaos-based approach, leveraging Fredkin logic gates and hyperchaos-induced keys, significantly enhances security, scalability, and efficiency, making it ideal for high-stakes satellite imagery applications where data integrity and confidentiality are paramount.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of satellite imaging, where the acquisition and transmission of high-resolution images play critical roles in diverse sectors such as national security, environmental monitoring, and urban planning, the safeguarding of this sensitive data is of utmost importance1. Traditional encryption algorithms such as the Data Encryption Standard (DES), Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), and International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA) have been instrumental in protecting data. However, these methods often do not fully meet the unique demands of satellite imagery, where both high security and minimal loss of image detail are required2. Satellite images can contain sensitive information ranging from strategic military installations to critical infrastructure details, making their security a top priority3. Satellite images differ from regular images in several critical aspects that influence encryption requirements. First, satellite images typically possess higher resolutions and larger file sizes, which necessitate encryption algorithms that are both computationally efficient and scalable4. Second, satellite data often contains sensitive geographic and strategic information (e.g., military installations, environmental monitoring zones), which raises the bar for security against statistical and differential attacks5. Third, satellite imagery is frequently used in real-time or near-real-time applications, such as disaster management and surveillance, demanding low-latency encryption and decryption6. Lastly, satellite images may undergo various pre-processing steps like radiometric correction and georeferencing, which require that the encryption process preserves data integrity and format compatibility. These requirements are more stringent than those for regular multimedia images, where minor losses and delays are more tolerable.

Unlike traditional approaches that encrypt each image individually in sequence, multiple image encryption schemes combine several images into a single augmented representation before encryption7,8. This strategy not only reduces the overall encryption time by enabling parallelized or batch processing, but also enhances security by increasing data complexity and entropy9. It is particularly beneficial in big data and remote sensing contexts, where handling multiple high-resolution satellite images simultaneously is common10.

In the field of multimedia security, the application of chaos theory has become particularly prominent, offering a robust framework for the encryption of diverse content forms11. Utilizing the inherent unpredictability and sensitivity to initial conditions characteristic of chaotic systems, chaos-based encryption methods introduce a high degree of non-linearity and complexity12,13,14. This is crucial for thwarting a variety of cryptographic attacks, enhancing the security of multimedia files. Specifically, in image encryption, these chaotic properties facilitate the generation of pseudo-random sequences that are used to permute and diffuse pixel values effectively, thus obscuring original image content15,16. The iterative nature of chaotic maps allows for dynamic and adjustable security layers, significantly enhancing protection. Additionally, chaos-based image encryption algorithms are known for their efficiency, making them ideal for real-time applications and suitable for environments with constrained computational resources17,18. This adaptability does not compromise the file size or format, which is essential for large-scale applications such as satellite imagery or streaming services1,7. Overall, the integration of chaos theory into multimedia encryption ensures robust security, maintaining both the integrity and confidentiality of digital media19.

The use of logical operators such as XOR (Exclusive OR)20, XNOR (Exclusive NOR)21, the Fredkin gate22, and the CNOT (Controlled NOT) gate23, plays a crucial role in the field of data encryption, particularly for multimedia content like satellite images. The reversible property of these gates, where the input can be derived from the output without any loss of information, is particularly appealing in multimedia encryption. This reversibility ensures that the original high-quality images can be perfectly reconstructed after decryption, an essential factor for applications where detail and accuracy are paramount21,24. The XOR and XNOR operators are favored in image encryption algorithms due to their simplicity and effectiveness in altering the image data to secure it against unauthorized access. The Fredkin gate and CNOT gate offer additional security benefits; the Fredkin gate performs controlled swaps based on the input condition, and the CNOT gate provides a bitwise conditional operation that is fundamental in quantum computing and adds a layer of complexity and robustness to the encryption process, enhancing its resistance to cryptographic attacks25.

This article significantly advances the field of multimedia encryption with several key contributions:

-

1.

Chaos theory application: It introduces a novel chaos-based image encryption scheme tailored specifically for satellite images, enhancing security through increased unpredictability.

-

2.

Augmented image encryption: The method combines multiple plain images into one before encryption, increasing process efficiency and security complexity.

-

3.

Three-stage encryption process: It details a sophisticated method involving transformation, manipulation using the Gauss Circle map, and restructuring via Fredkin gates, adding depth to the security measures.

-

4.

Hyperchaos keys and dynamic Hill cipher: The integration of these elements introduces additional layers of security, dynamically adapting to ensure consistent protection.

-

5.

Security and efficiency evaluation: The article provides a comprehensive analysis of the method’s security against various attacks (i.e. a key space of \(2^{4464}\)) and demonstrates its practicality for real-time applications (i.e. an encryption rate of 5.98 Mbps, essential for handling large-scale satellite image data.

-

6.

Overall, the contributions of this article improve the encryption of satellite images employing advanced cryptographic techniques and thorough security evaluations.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section "Related literature" discusses recent related literature. Section "Foundational mathematical constructs" outlines the foundational mathematical constructs. Section "Proposed algorithm" details the encryption and decryption processes. Section "Performance evaluation" showcases the outcomes of implementing the proposed cipher on different examples and evaluates its effectiveness through visual, statistical, and quantitative measures. Finally, Section "Conclusions and Future Works" provides the conclusions of this article and suggests possible future research directions that may be further pursued.

Related literature

The evolution of image encryption has witnessed remarkable developments over the past decade, driven by growing concerns about data security in various domains, including geographic information systems (GIS). While traditional cryptographic methods struggled with the unique challenges posed by large-scale satellite imagery, recent advances in chaos theory and quantum-inspired algorithms have opened new pathways for secure image transmission. This section examines key developments in image encryption techniques, focusing particularly on approaches that leverage multiple encryption stages and dynamic key generation. Special attention is given to methods incorporating Shannon’s confusion-diffusion principles26 and their applications in securing sensitive geographic data1. The following paragraphs attempt to portray the state of the current image encryption literature.

Chaos-based image encryption methods

Chaos-based methods have gained significant traction due to their inherent properties of unpredictability, sensitivity to initial conditions, and ergodicity. In20, the authors present an image encryption algorithm combining unique image transformations with chaotic and hyper-chaotic systems, leveraging the Chua and Chen systems for rescaling, rotation, and randomization. Their approach offers a vast key space of \(2^{5208}\), ensuring strong security. The work in21 introduces an encryption method using base-n Pseudo-Random Number Generators (PRNGs) and parallel base-n S-boxes, hybridizing chaotic systems (e.g., Chen and Chua) with memristor circuits. This method enhances resistance to attacks while achieving parallelization for faster processing. The authors of27 proposed a chaos-based encryption scheme using random chaos sequences for pixel permutation and diffusion. Sensitivity to initial conditions and control parameters ensures high security. In28, the authors introduced a hybrid scheme combining the Lorenz chaotic system with an inverse left almost semigroup structure. This multi-stage confusion-diffusion process demonstrated strong robustness against differential and linear attacks, making it suitable for multimedia security.

Chaotic map combinations for efficiency and security

Several works have explored the combination of chaotic maps to achieve simplicity, efficiency, and high-security margins. The combined use of Hénon and logistic chaotic maps was proposed in29. This permutation- and diffusion-based algorithm achieves high sensitivity to initial conditions, ensuring robustness against statistical and differential attacks. The authors of30 propose a confusion-diffusion encryption technique where image pixels are shuffled and then diffused by XORing with a secret key generated from multiple chaotic maps. Specifically, the Arnold cat map, the 2D logistic sine map, the linear congruential generator, the Bernoulli map, and the tent map. The work in31 employs multiple chaotic iterative maps, including the Hénon, Duffing, and circle chaotic maps, alongside the Rand block function. The confusion-diffusion mechanism enhances encryption strength and ensures secrecy.

S-box construction for cryptographic applications

S-boxes play a critical role in block ciphers and image encryption by introducing non-linearity and resistance to various attacks. In32, the authors propose constructing S-boxes using points on an elliptic curve over a prime field. These S-boxes are evaluated for resistance to linear, differential, and algebraic attacks, demonstrating strong cryptographic properties. The authors of33 introduced a method for constructing S-boxes using Gaussian distribution and linear fractional transform. The design employs the Box-Muller transform and central limit algorithm, achieving high cryptographic strength based on standardized tests. A secure image encryption scheme combining an algebraic S-box with the scrambling effect of the Arnold transform was presented in34. The algebraic structure of the multiplicative cyclic group of the Galois field enhances both security and computational efficiency. The work in35 proposes constructing S-boxes using cubic fractional transformation (CFT). Evaluated against criteria such as bijection, non-linearity, and avalanche effect, this method demonstrates strong potential for generating efficient S-boxes for block ciphers.

Multi-layer encryption, FPGA implementations and UAV-assisted networks

Recent advancements focus on multi-layer encryption schemes and secure transmission protocols for sensitive applications. To increase encryption efficiency, the authors of36 present an image encryption technique leveraging three hyperchaotic systems: a memristor system, a hyperchaotic 7D system, and an Erbium-doped fiber laser system, for a robust three-layer encryption process. Using PRNGs, it constructs S-boxes and encryption keys to secure image data. Implemented in software (Wolfram Mathematica® 13.1) and hardware (AMD Virtex-7 FPGA VC707), the scheme achieves encryption rates of 9.7 Mbps and 0.67 Gbps, respectively. In37, the authors propose a 2-layer image encryption cryptosystem for transmitting military reconnaissance images over UAV-assisted networks. The first layer employs a Genetic Algorithm (GA) with a Mersenne Twister (MT) key, followed by DNA coding for added security. The encrypted images are channel-coded (a convolutional or an LDPC code) and transmitted via multi-hop UAV relays, ensuring robust security and efficiency in hostile environments.

Summary and research gap

The reviewed literature highlights significant advancements in chaos-based image encryption, including multi-stage encryption, dynamic key generation, and the integration of chaotic maps and S-boxes to enhance security and efficiency. While these methods demonstrate robustness against various cryptographic attacks, they often lack a focus on augmenting multiple images into a single encryption process, which is critical for compressing and securing large-scale satellite data. Furthermore, the potential of quantum-inspired logic gates, such as Fredkin gates, remains largely unexplored in this domain. This research addresses these gaps by proposing a novel encryption scheme that combines image augmentation, chaos theory, and Fredkin logic to achieve enhanced security and scalability for satellite imagery applications.

Foundational mathematical constructs

Fredkin gate

Fredkin gate is one of the most flexible and reversible gate types. As shown in Fig. 1, the Fredkin gate takes a 3-bit input; each bit labelled as A, B and C, and generates a 3-bit output; each bit labelled as P, Q and R after processing. The output bit P in this gate has the same value as the input bit A. Based on the value of bit A, if it is zero, then Q will be equal to B and R will be equal to C. However, when A is one, Q will be equal to C and R will be equal to B. The values of Q and R are deduced from the value of A. In simple terms, the Fredkin gate only switches B and C when A is 1, keeping the value of A unchanged. It is referred to as the controlling swap gate, or CSWAP, because of the way it functions. The Truth table of the Fredkin gate is shown in Table 1.

Gauss circle chaotic map

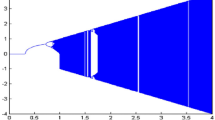

In38 the authors construct the Gauss Circle map. This map is a recursive function that integrates the Gauss map39, and the circle map40. From38 the equation of the Gauss Circle map is:

where \(\alpha =9\), \(\beta =0.481\), \(\lambda =10^6\), \(\Omega =0.5\) and \(x\in (0,1)\) are the best choices for a chaotic behaviour38, iterations of an initial value \(x_0\) result in chaotic rather than periodic trajectories over the interval \((0,1)\), due to the high precision of the system’s parameters. Permutation is achieved through the generation of highly chaotic sequences using Gauss Circle maps. The Gauss Circle map sequence successfully passed all 16 NIST tests and demonstrated a robust defense against entropy attacks38.

6D hyperchaotic system

The authors of41 construct a six-dimensional (6D) hyperchaotic system. The system is defined by the following set of differential equations:

where \(X=(x_1,x_2,x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6)\) represents the states of the hyperchaotic system, while \((\beta _1,\beta _2,\beta _3,\beta _4,\beta _5,\beta _6)\) are parameters that govern the chaotic behavior of the system. The system exhibits hyperchaotic behavior when \(\beta _1 \in [15, 4.273]\), \(\beta _2=2.7\), \(\beta _3=-3\), \(\beta _4=2\), \(\beta _5=100\), and \(\beta _6=1\). The chaotic behavior is verified through the calculation of the Lyapunov exponents, which are given as \(\lambda _1=1.3613\), \(\lambda _2= 0.0733\), \(\lambda _3= 0.0478\), \(\lambda _4=0.0189\), \(\lambda _5=0\) and \(\lambda _6=-14.201\). Since there are four positive Lyapunov exponents, this system is classified as hyperchaotic.

Additionally, the authors identified singularly degenerate heteroclinic cycles and bifurcations leading to hidden hyperchaotic attractors through analytical methods and numerical simulations. The dynamics have been confirmed through the 0-1 test and circuit testing41.

8D hyperchaotic system

The authors of42 analyzed the dynamic properties of a new 8D hyperchaotic system. The system is defined by the following set of differential equations:

where \(X=(x_1,x_2,x_3,x_4,x_5,x_6,x_7,x_8)\) indicates the 8D hyperchaotic system’s variables, \((\beta _1,\beta _2,\beta _3,\beta _4,\beta _5,\beta _6,\beta _7)\) are parameters that determine the chaotic behavior of the system when the initial values of the variables are set as \(X=(1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0)\), \(\beta _1=10\), \(\beta _2=76\), \(\beta _3=3\), \(\beta _4=0.2\), \(\beta _5=0.1\), \(\beta _6=0.1\) and \(\beta _7=0.2\). The characteristic Lyapunov exponents are computed as \(\lambda _1=1.4565\), \(\lambda _2=0.1176\), \(\lambda _3=0.0623\), \(\lambda _4=0.0433\), \(\lambda _5=0.0260\), \(\lambda _6= 0.0132\), \(\lambda _7=0\) and \(\lambda _8 =-12.6987\). Since there are 6 positive Lyapunov exponents, this system shows a good hyperchaotic behavior according to43. To evaluate the system’s physical feasibility, an equivalent electronic circuit was created using the Multisim® software in42. Using an 8D hyperchaotic system with 23 terms and 7 control parameters, the suggested algorithm produces a large key space and an extremely safe encryption technique that has a low time complexity.

Hill cipher

The Hill cipher, introduced by Lester S. Hill in 1929, marked a significant milestone in classical cryptography. Unlike traditional substitution ciphers that operate on individual characters, the Hill cipher utilizes linear algebra to encrypt entire blocks of text simultaneously through matrix operations44. By leveraging the mathematical properties of matrices, it became one of the earliest polygraphic ciphers, where each ciphertext character is influenced by multiple plaintext characters. The decryption process, which depends on matrix inversion, combines cryptographic robustness with mathematical sophistication. Its application in modern cryptographic analysis not only emphasizes its historical significance but also demonstrates the continued relevance of algebraic methods in fields like image encryption45.

In the Hill cipher, plaintext blocks are represented as vectors, which are transformed into ciphertext vectors through multiplication with an encryption matrix \(B\), followed by taking the result modulo \(m\), where \(m\) denotes the alphabet size. Let \(\textbf{X}\) represent the plaintext vector and \(\textbf{Y}\) the ciphertext vector. The encryption process can be expressed as:

Decryption reverses this process using the inverse of the encryption matrix, denoted as \(B^{-1}\), provided it exists modulo \(m\). This is possible only if the determinant of \(B\) satisfies \(\text {gcd}(\text {det}(B), m) = 1\). The decryption process is expressed as:

For both encryption and decryption, the matrices \(B\) and \(B^{-1}\) must have dimensions compatible with the length of the plaintext vector \(\textbf{X}\). The parameter \(m\) typically denotes the size of the alphabet (e.g., \(26\) for the English alphabet). This configuration ensures that each letter (or block of letters, depending on the matrix size) from the plaintext is methodically converted into ciphertext, utilizing matrix operations to achieve cryptographic transformation.

Proposed algorithm

Encryption process

In this section, the construction of the encryption process is explained in the following steps.

-

1.

Stage 1:

-

(a)

Multiple plain images are generated and then formed into a single augmented image \(I_{A}\).

-

(b)

Separate the augmented plain image into 3 color channels; Red, Green and Blue and convert them into 1D bit-streams giving \(I_{[A,1D,Red]}\), \(I_{[A,1D,Green]}\) and \(I_{[A,1D,Blue]}\).

-

(c)

Given \(Seed_{Gauss}\), 3 different bit-streams are generated from the Gauss circle chaotic map from (1) giving \(Key_{GaussRed}\), \(Key_{GaussGreen}\) and \(Key_{GaussBlue}\).

-

(d)

\(I_{[A,1D,Red]}\) is divided into halves to be inputs of B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussRed}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin]}\).

-

(e)

\(I_{[A,1D,Green]}\) is divided into halves to be inputs B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussGreen}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin]}\).

-

(f)

\(I_{[A,1D,Blue]}\) is divided into halves to be inputs B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussBlue}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin]}\).

-

2.

Stage 2:

-

(a)

Given \(Seed_{6D}\), 3 different S-boxes are constructed from the 6D hyperchaotic system in (2) giving \(Sbox_{6Dred}\), \(Sbox_{6Dgreen}\) and \(Sbox_{6Dblue}\), as shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

-

(b)

\(I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin]}\) is converted into bytes and invoked with \(Sbox_{6Dred}\) giving:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin,Sbox]}=Sbox\big (I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin]}\big ) \end{aligned}$$(6) -

(c)

\(I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin]}\) is converted into bytes and invoked with \(Sbox_{6Dgreen}\) giving:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin,Sbox]}=Sbox\big (I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin]}\big ) \end{aligned}$$(7) -

(d)

\(I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin]}\) is converted into bytes and invoked with \(Sbox_{6Dblue}\) giving:

$$\begin{aligned} I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox]}=Sbox\big (I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin]}\big ) \end{aligned}$$(8)

-

3.

Stage 3:

-

(a)

Given \(Seed_{8D}\), 3 different \(2\times 2\) Hill cipher matrices are generated from (3) giving \(Key_{HillCipherRed}\), \(Key_{HillCipherGreen}\) and \(Key_{HillCipherBlue}\).

-

(b)

\(I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) is converted into \(2\times 2\) matrices then matrix multiplication is applied with \(Key_{HillCipherRed}\) giving \(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\).

-

(c)

\(I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) is converted into \(2\times 2\) matrices then matrix multiplication is applied with \(Key_{HillCipherGreen}\) giving \(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\).

-

(d)

\(I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) is converted into \(2\times 2\) matrices then matrix multiplication is applied with \(Key_{HillCipherBlue}\) giving \(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\).

-

(e)

Finally, combine the 3 color channels together and reshape into an image. This produces an encrypted augmented image \(I'_{A}\).

An illustration of the encryption process is depicted in Fig. 2.

Decryption process

In this section, the construction of the decryption process is explained in the following steps.

-

1.

Stage 3:

-

(a)

Start with the encrypted augmented image, separate it into 3 color channels: Red, Green and Blue.

-

(b)

Convert the color channels into N \(2\times 2\) matrices \(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\),

\(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\) and

\(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2,Hill]}\).

-

(c)

Inverse matrices of Hill cipher are generated giving \(Key'_{HillCipherRed}\),

\(Key'_{HillCipherGreen}\) and \(Key'_{HillCipherBlue}\).

-

(d)

\(I_{[A,1D,Red,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) goes through matrix multiplication with \(Key'_{HillCipherRed}\) giving \(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\).

-

(e)

\(I_{[A,1D,Green,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) goes through matrix multiplication with \(Key'_{HillCipherGreen}\) giving \(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\).

-

(f)

\(I_{[A,1D,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox]}\) goes through matrix multiplication with \(Key'_{HillCipherBlue}\) giving \(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\).

-

2.

Stage 2:

-

(a)

The inverse of 3 S-boxes are generated, giving \(Sbox'_{6Dred}\), \(Sbox'_{6Dgreen}\) and \(Sbox'_{6Dblue}\).

-

(b)

\(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\) is converted into 1D byte-stream and invoked with \(Sbox'_{6Dred}\) giving \(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,1D]}\).

-

(c)

\(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\) is converted into 1D byte-stream and invoked with \(Sbox'_{6Dgreen}\) giving \(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,1D]}\).

-

(d)

\(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,Sbox,2\times 2]}\) is converted into 1D byte-stream and invoked with \(Sbox'_{6Dblue}\) giving \(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,1D]}\).

-

3.

Stage 1:

-

(a)

\(I_{[A,Red,Fredkin,1D]}\) is converted into a bit-stream and divided into 2 halves as inputs B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussRed}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Red]}\).

-

(b)

\(I_{[A,Green,Fredkin,1D]}\) is converted into a bit-stream and divided into 2 halves as inputs B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussGreen}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Green]}\).

-

(c)

\(I_{[A,Blue,Fredkin,1D]}\) is converted into a bit-stream and divided into 2 halves as inputs B and C for the Fredkin gate with \(Key_{GaussBlue}\) as input A giving \(I_{[A,1D,Blue]}\).

-

(d)

Finally, combine the 3 color channels into a single one and reshape back into an image forming the decrypted augmented image, which can split into multiple separate decrypted images.

An illustration of the decryption process is depicted in Fig. 3.

Performance evaluation

This section conducts an extensive analysis using a computer that is equipped with an Intel® CoreTM i7-7500U CPU at 2.7 GHz and 8 GB of RAM. Unless specified otherwise, the images used are enhanced and resized to \(256\times 256\) pixels. Test images are sourced from 2 online collections: the USC-SIPI database46 and the MAR20 database47. Performance evaluation metrics commonly used in the image encryption scientific community are utilized in this article. These are presented in Table 5 and serve to quantitatively assess the performance of the proposed encryption scheme. The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) measures the similarity between the original and encrypted images. In encryption, a low PSNR value is desirable, as it indicates that the encrypted image is significantly different from the original, ensuring strong obfuscation. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) quantify the average error between image pixels before and after encryption or decryption. Entropy evaluates the randomness of the encrypted image (with values close to 8 indicating high unpredictability, which is ideal for secure encryption). The Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) assesses the structural similarity between original and decrypted images; a value of 1 confirms perfect reconstruction. The Number of Pixels Change Rate (NPCR) and the Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) measure the encryption’s sensitivity to small changes in the input, representing the algorithm’s robustness against differential attacks. The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) provide frequency and pixel correlation analyses, respectively, helping to evaluate how well the encryption disrupts inherent image patterns.

Visual and histogram analyses

Figure 4 illustrates the transformation of a plain augmented image (a) into an encrypted noise-like augmented image (b) using the proposed encryption scheme. The histogram of the plain augmented image (c) exhibita distinct patterns in the RGB channels, reflecting the original content, while the histograms of the encrypted augmented image (d) shows uniform distributions, indicating successful diffusion and confusion. This uniformity ensures the obfuscation of all visual and statistical features, protecting the augmented data from cryptographic attacks. The results confirm the algorithm’s robustness in securing sensitive augmented images while preserving the integrity of the data format.

Statistical analyses

The results presented in Table 6 demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed image encryption algorithm through various statistical metrics. The SSIM is consistently 1 for all test images, indicating perfect similarity between the decrypted and the original plain images, ensuring no structural distortion during the decryption process. However, the high MSE values and low PSNR values reflect significant encryption-induced transformations, which are essential for security. The MAE values further confirm notable pixel-level alterations. Additionally, the entropy metrics (\(H_P\) and \(H_E\)) indicate high randomness in the encrypted images, with \(H_E\) values close to the ideal upper bound of 8, affirming strong encryption quality. These metrics collectively validate the robustness and security of the proposed algorithm.

Table 7 compares the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) values of plain and encrypted images across three directions: horizontal (H), diagonal (D), and vertical (V). The plain images exhibit high PCC values (averaging 0.91, 0.86, and 0.89 for H, D, and V, respectively), indicating strong pixel correlation and redundancy typical of natural images. In contrast, the encrypted images show near-zero PCC values (averaging \(-0.00396\), \(-0.001675\), and 0.000874 for H, D, and V, respectively), demonstrating that the proposed encryption algorithm effectively randomizes pixel relationships and eliminates structural dependencies. This highlights the algorithm’s robustness in ensuring image security by disrupting inherent correlations in the original images.

Differential attacks analysis

Differential attacks evaluate an encryption algorithm’s sensitivity to slight changes in plaintext, with strong algorithms producing significantly different ciphertexts for minimal input changes. Metrics like NPCR (Number of Pixels Change Rate) and UACI (Unified Average Changing Intensity) assess this sensitivity. High NPCR values indicate significant pixel changes, while UACI measures the average intensity of those changes. As shown in Tables 8 and 9, the proposed algorithm achieves an average NPCR of 99.6115 and UACI of 31.70622, demonstrating robust resistance to differential attacks and consistent performance across diverse images, including benchmarks like “Mandrill” and “Peppers.” The slight deviation of the UACI value from the theoretical ideal of \(33.46\%\) can be attributed to the structured nature of the augmented image and the deterministic components of the encryption process. While the method employs multiple chaotic layers and logical operations to enhance diffusion, components such as the structured Hill cipher and the need to preserve reversibility may slightly reduce pixel intensity variation. Nonetheless, the achieved UACI still reflects strong diffusion and confirms the robustness of the proposed scheme.

Discrete fourier transform analysis

Figure 5 illustrates the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) applied to both a plain and an encrypted augmented image. The DFT of the plain image (a) shows a distinct concentration of frequency components at the center, indicating a significant amount of low-frequency information typical of unencrypted images. In contrast, the DFT of the encrypted image (b) presents a uniform distribution of frequency components, suggesting effective diffusion and obscuration of the original image’s frequency characteristics. This uniformity is indicative of high entropy and randomness in the encrypted image, which are desirable properties in secure image encryption schemes, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed encryption algorithm in dispersing the spectral components and enhancing the security of satellite images.

Encryption time analyses

Table 10 presents the encryption time for augmented images of various dimensions, demonstrating the computational efficiency of the proposed algorithm. As the image size increases, the encryption time grows proportionally, ranging from 0.0727s for a \(128\times 128\) image to 4.2098s for a \(1024 \times 1024\) image. These results highlight the scalability of the method, making it suitable for encrypting high-resolution satellite images while maintaining practical processing times.

Big O complexity

The computational complexity of the proposed algorithm is \({\mathcal {O}}(M \times N)\), where M and N denote the dimensions of the input image. Table 11 presents a comparative analysis of the computational complexity of the proposed method with recent literature. The results indicate a comparable or superior performance to algorithms presented in recent literature.

S-box performance analysis

S-boxes are critical in image encryption, providing non-linearity and resistance to attacks like differential and linear cryptanalysis. Table 12 shows the proposed S-boxes exhibit strong cryptographic properties, with nonlinearity (NL) and bit independence criterion (BIC) values (108) close to the ideal (112), SAC (\(\approx 0.497\)) near 0.5, and DAP matching the ideal (0.015625). These metrics confirm the S-boxes’ robustness and contribution to secure, efficient encryption.

Occlusion and noise attack analyses

This section examines the resilience of the proposed encryption algorithm under various adverse conditions as depicted in Fig. 6, Fig. 7, and Fig. 8.

Fig. 6 focuses on the encryption’s performance against occlusion attacks, where black squares of varying sizes (\(10\%\), \(20\%\), and \(30\%\) of the image area) simulate blocked portions of the image. The analysis shows that despite substantial occlusion, the encrypted image’s content remains secure and visually obscured, demonstrating the algorithms’s effectiveness in preserving data confidentiality even when significant parts of the image are obstructed. Furthermore, Table 13 shows the numerical analysis of various occlusion attack results in various images in comparison with the literature. The results indicate that the proposed encryption scheme results in higher MSE and lower PSNR under occlusion compared to existing methods, reflecting stronger security but lower robustness. While this reduces image recoverability and favors confidentiality, it highlights a trade-off with resilience to partial data loss.

Fig. 7 evaluates the scheme’s robustness against salt and pepper noise at different intensities (\(1\%\), \(5\%\), and \(10\%\)). The results indicate that the encrypted images maintain a high level of disorder, with no visible patterns or leakage of information, thereby underscoring the encryption’s capability to withstand disruptions caused by such noise.

Fig. 8 presents the impact of Gaussian noise with standard deviations \(\sigma = 0.0001\), 0.0006, and 0.001 on the encrypted images. The images display a consistent preservation of visual integrity across increasing levels of noise, highlighting the scheme’s strong defense against statistical noise, which is typical in real-world scenarios involving signal transmission and storage.

Together, these figures effectively demonstrate the proposed algorithms’s substantial defensive properties against a range of occlusion and noise attacks, affirming its suitability for high-security satellite imaging applications where maintaining data integrity and confidentiality is paramount.

Key sensitivity analysis

To illustrate the key sensitivity of the proposed algorithm, Fig. 9 displays various decryption scenarios. The first scenario demonstrates successful decryption using the correct keys, resulting in a perfectly reconstructed image. In contrast, changing a single bit or two bits in the decryption keys leads to failed decryption, where the recovered image becomes corrupted and loses its original information. This highlights the sensitivity of the decryption process to minor key modifications.

NIST SP \(800-22\) analysis

Table 14 summarizes results from the NIST suite of tests, which evaluate the randomness of sequences crucial for cryptographic security. Each test assesses different randomness aspects, with p-values indicating the likelihood that a sequence is random. A p-value greater than 0.01 typically suggests acceptable randomness. The results consistently marked as ’Success’ across various tests, including Frequency, Block Frequency, Runs, Serial, Random Excursions, and their Variants, confirm the robust randomness of the tested sequences. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the encryption method in producing secure, random sequences essential for reliable cryptographic applications.

Key space analysis

Key space is a crucial measure for assessing the security of an encryption scheme against brute force attacks. The system is constructed from the hyperchaotic system in (3) which utilizes 15 parameters for each single color channel. In addition, the S-boxes generated come from the hyperchaotic system in (2) which utilizes 12 parameters for each color channel. Finally, the Gaussian map in (1) utilizes 5 parameters that generate a bit-stream for every color channel that is utilized in the Fredkin gate operation, where the total will be \(15\times 3 + 12\times 3+5\times 3=96\) and with a maximum machine precision of \(10^{-16}\), the key space is \(10^{16\times 96}=10^{1536}\), which is approximately \(2^{5102}\). This achieved key space is well above the literature-recommended threshold of \(2^{100}\)52.

Comparative analysis with the literature

A comparative analysis is shown in Table 15, where the performance of various image encryption algorithms is displayed, including the proposed one that is tailored specifically for satellite images. In particular, the proposed algorithm achieves a lower PSNR and a higher MAE compared to other methods, which is advantageous in this context as it suggests stronger encryption (lower PSNR indicates less similarity between the original and encrypted images, and higher MAE indicates more significant alterations). Entropy values close to the maximum and very low or negative correlation coefficients across the proposed method indicate robust randomness and minimal resemblance to the original, enhancing security against statistical attacks. Additionally, the high NPCR values and reasonable UACI values further confirm the sensitivity and intensity of the modifications, underscoring the effectiveness of the proposed method in securing sensitive geographic data through advanced encryption techniques. This analysis highlights the suitability of the proposed method for high-security applications such as satellite imagery, where data integrity and confidentiality are paramount.

The results in Table 16 highlight the superior computational efficiency of the proposed scheme, with an encryption time of 0.2817s, significantly faster than 0.7528s in20 and 3.0019s in30. All tests were conducted on relatively comparable hardware, demonstrating the practicality of the proposed algorithm for real-time satellite image encryption while maintaining robust security.

Table 17 shows that the proposed S-boxes demonstrate strong overall performance compared to those in the literature, with excellent results in Differential Approximation Probability (DAP), matching the ideal value of 0.015625, and competitive Linear Approximation Probability (LAP) values (0.07813), outperforming many referenced S-boxes. While the Non-Linearity (NL) values (108) are slightly below the ideal (112) and some top-performing S-boxes, they remain competitive. The Strict Avalanche Criterion (SAC) values \((\approx 0.497)\) are close to the ideal (0.5), and the Bit Independence Criterion (BIC) values (108) are consistent and comparable to most counterparts. Overall, the proposed S-boxes strike a strong balance between cryptographic strength and practical performance, making them viable for secure image encryption applications, with room for minor improvements in NL and SAC.

The key space of an encryption algorithm is a critical factor in determining its resistance to brute-force attacks. Table 18 compares the key space of various image encryption algorithms from the literature, highlighting the significant advantage of the proposed method. With a key space of \(2^{5102}\), the proposed algorithm surpasses most existing methods, including those with substantial key spaces such as36 \(2^{4624}\) and30 (\(2^{554}\)). Notably, some prior works, such as21, have considerably smaller key spaces (\(>2^{100}\)), making them more vulnerable to exhaustive search attacks. The formulation \(2^{8 \times M \times N}\) in29 suggests a dependency on image dimensions, which may offer scalability but also variability in security. Overall, the proposed algorithm’s exceptionally large key space provides a robust defense against brute-force attacks, reinforcing its suitability for secure image encryption.

Conclusions and future works

This work presented a multi-stage chaos-based encryption scheme designed specifically for satellite images. The proposed algorithm integrates classical cryptographic techniques with chaotic systems, including the Gauss Circle map, Fredkin gates, hyperchaotic key generation, and dynamic Hill Ciphers. By augmenting and encrypting multiple images simultaneously, the method enhances both security and processing efficiency.

The encryption process achieves high levels of confusion and diffusion, as evidenced by strong statistical metrics such as entropy values near the ideal of 8, NPCR rates exceeding \(99.6\%\), and low PSNR values, all indicating robust resistance to differential and statistical attacks. Additionally, the scheme maintains computational efficiency, with an encryption time of 0.2817 seconds for \(256 \times 256\) images, and demonstrates resilience to various attacks, including noise, occlusion, and brute-force attempts.

Despite its strengths, the proposed scheme has a few limitations. The image augmentation step increases memory usage, which may pose challenges for resource-constrained environments. The reliance on high-precision chaotic systems can complicate hardware implementation. Furthermore, while the algorithm performs well in software simulations, further validation on real-time hardware platforms is necessary to confirm its practical applicability in real-world satellite systems.

Future research will focus on addressing these limitations by exploring lightweight hardware implementations, adaptive parameter tuning, and optimizing the algorithm for deployment in constrained or real-time environments. Additionally, integrating the encryption scheme with secure transmission protocols and evaluating its performance on edge-processing satellite platforms are promising directions for further development.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Youssef, M. et al. Enhancing satellite image security through multiple image encryption via hyperchaos, svd, rc5, and dynamic s-box generation. IEEE Access 12, 123 921-123 945 (2024).

Alexan, W., Alexan, N. & Gabr, M. Multiple-layer image encryption utilizing fractional-order chen hyperchaotic map and cryptographically secure prngs. Fractal Fract. 7(4), 287 (2023).

Bentoutou, Y., Bensikaddour, E.-H., Taleb, N. & Bounoua, N. An improved image encryption algorithm for satellite applications. Adv. Space Res. 66(1), 176–192 (2020).

Lavanya, M., Sundar, K., & Saravanan, S. Simplified image encryption algorithm (SIEA) to enhance image security in cloud storage. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 61313–61345, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-17969-0 (2024).

Ukamaka, O. N., Nonyelum, O. F., Rajesh, P., & Sanusi, M. Multipurpose satellite image analysis for land cover classification, object detection, disaster classification and military spot identification. IUP Journal of Computer Sciences, 18(2), (2024).

Naim, M., Pacha, A. A. & Serief, C. A novel satellite image encryption algorithm based on hyperchaotic systems and josephus problem. Adv. Space Res. 67(7), 2077–2103 (2021).

Alexan, W., Hosny, K. & Gabr, M. A new fast multiple color image encryption algorithm. Clust. Comput. 28(5), 1–34 (2025).

Hu, L.-L., Chen, M.-X., Wang, M.-M. & Zhou, N.-R. A multi-image encryption scheme based on block compressive sensing and nonlinear bifurcation diffusion. Chaos Solit. Fractals 188, 115521 (2024).

Alexan, W. et al. A new multiple image encryption algorithm using hyperchaotic systems, svd, and modified rc5. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 9775 (2025).

Zhou, N.-R., Hu, L.-L., Huang, Z.-W., Wang, M.-M. & Luo, G.-S. Novel multiple color images encryption and decryption scheme based on a bit-level extension algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122052 (2024).

Qiao, L., Mei, Q., Jia, X. & Ye, G. Image encryption scheme based on pseudo-dwt and cubic s-box. Phys. Scr. 99(8), 085259 (2024).

Hosny, K. M., Zaki, M. A., Lashin, N. A., Fouda, M. M. & Hamza, H. M. Multimedia security using encryption: A survey. IEEE Access 11, 63 027-63 056 (2023).

Alexan, W. et al. Stegocrypt: A robust tri-stage spatial steganography algorithm using tlm encryption and dna coding for securing digital images. IET Image Process. 18, 4189-4206. (2024).

Long, G., Verma, V., Jiang, D., Yang, Y. & Ahmad, M. A le-controlled 4d non-degenerate hyperchaotic system and stp-cs model based efficient image encryption algorithm. PPhys. Scr. 100(2), 025228 (2025).

Alexan, W. et al. Anteater: When arnold’s cat meets langton’s ant to encrypt images. IEEE Access 11, 106 249-106 276 (2023).

Alexan, W., El-Damak, D. & Gabr, M. Image encryption based on fourier-dna coding for hyperchaotic chen system, chen-based binary quantization s-box, and variable-base modulo operation. IEEE Access 12, 21 092-21 113 (2024).

Fan, F., Verma, V., Long, G., Tsafack, N. & Jiang, D. Image encryption scheme using a new 4-d chaotic system with a cosinoidal nonlinear term in wmsns. Phys. Scr. 99(5), 055216 (2024).

Ge, B., Chen, X., Chen, G. & Shen, Z. Secure and fast image encryption algorithm using hyper-chaos-based key generator and vector operation. IEEE Access 9, 137 635-137 654 (2021).

Liu, X. & Yang, J. A novel multi-layer image encryption algorithm based on 2d drop-wave function. Nonlinear Dyn. 113(2), 1775–1797 (2025).

Gabr, M. et al. R3—rescale, rotate, and randomize: A novel image cryptosystem utilizing chaotic and hyper-chaotic systems. IEEE Access 11, 119 284-119 312 (2023).

Gabr, M., Elias, R., Hosny, K. M., Papakostas, G. A. & Alexan, W. Image encryption via base-n prngs and parallel base-n s-boxes. IEEE Access 11, 85 002-85 030 (2023).

Annaby, M., Mahmoud, M., Abdusalam, H., Ayad, H. & Rushdi, M. 2d representations of 3d point clouds via the stereographic projection with encryption applications. Multimed. Syst. 30(4), 173 (2024).

He, J., Zhu, H. & Zhou, X. Quantum image encryption algorithm via optimized quantum circuit and parity bit-plane permutation. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 81, 103698 (2024).

Perumalla, K. S. Introduction to reversible computing (CRC Press, Florida, 2013).

Soeken, M., & Roetteler, M. Quantum circuits for functionally controlled not gates. in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE). IEEE, pp. 366–371 (2020).

Shannon, C. E. Communication theory of secrecy systems. The Bell system technical journal 28(4), 656–715 (1949).

Pourasad, Y., Ranjbarzadeh, R., & Mardani, A. A new algorithm for digital image encryption based on chaos theory. Entropy, 23(3), (2021). [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/23/3/341

Younas, I. & Khan, M. A new efficient digital image encryption based on inverse left almost semi group and lorenz chaotic system. Entropy 20(12), 913 (2018).

Arab, A. A., Rostami, M. J. B., & Ghavami, B. An image encryption algorithm using the combination of chaotic maps. Optik, 261, 169122, (2022). [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0030402622004843

Elkandoz, M. T. & Alexan, W. Image encryption based on a combination of multiple chaotic maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81(18), 25 497-25 518 (2022).

Khan, M. & Masood, F. A novel chaotic image encryption technique based on multiple discrete dynamical maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 26 203-26 222 (2019).

Hayat, U., Azam, N. A., & Asif, M. A method of generating 8 \({\times }\) 8 substitution boxes based on elliptic curves. Wirel. Pers. Commun., 101(1), 439–451, (2018). [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-018-5698-1.

Khan, M. F., Ahmed, A. & Saleem, K. A novel cryptographic substitution box design using gaussian distribution. IEEE Access 7, 15 999-16 007 (2019).

Farwa, S., Muhammad, N., Shah, T., & Ahmad, S. A novel image encryption based on algebraic s-box and arnold transform. 3D Research 8(3), 26, (Jul 2017). [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13319-017-0135-x.

Zahid, A. H., Arshad, M. J., & Ahmad, M. A novel construction of efficient substitution-boxes using cubic fractional transformation. Entropy 21(3), (2019). [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/21/3/245

Alexan, W. et al. Triple layer rgb image encryption algorithm utilizing three hyperchaotic systems and its fpga implementation. IEEE Access 12, 118 339-118 361 (2024).

Alexan, W. et al. Secure communication of military reconnaissance images over uav-assisted relay networks. IEEE Access 12, 78 589-78 610 (2024).

Suryadi, M., Satria, Y., & Hadidulqawi, A. Implementation of the gauss-circle map for encrypting and embedding simultaneously on digital image and digital text. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1821(1). IOP Publishing, p. 012037 (2021).

Sahay, A., & Pradhan, C. Gauss iterated map based rgb image encryption approach. 2017 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP). pp. 0015–0018 (IEEE, 2017).

Boyland, P. L. Bifurcations of circle maps: Arnol’d tongues, bistability and rotation intervals. Commun. Math. Phys. 106, 353–381 (1986).

Sun, S. A new image encryption scheme based on 6d hyperchaotic system and random signal insertion. IEEE Access 11, 66009-66016. (2023).

M. E. Y. Khaled Benkouider, Toufik Bouden, & Vaidyanathan, S. A new family of 5d, 6d, 7d and 8d hyperchaotic systems from the 4d hyperchaotic vaidyanathan system, the dynamic analysis of the 8d hyperchaotic system with six positive lyapunov exponents and an application to secure communication design. Model. Identif. Control 35, 241-257. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIC.2020.114191 (2021).

Biban, G., Chugh, R. & Panwar, A. Image encryption based on 8d hyperchaotic system using fibonacci q-matrix. Chaos Solit. Fractals 170, 113396 (2023).

Hadi, H. H. & Neamah, A. A. An image encryption method based on modified elliptic curve diffie-hellman key exchange protocol and hill cipher. Open Eng. 14(1), 20220552 (2024).

VAMSI, D., & CH, P. R. Color image encryption based on arnold cat map-elliptic curve key and a hill cipher. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol., 102(9), 4116–4127 (2024).

Signal and Image Processing Institute. USC-SIPI image database. University of Southern California. [Online]. Available: http://sipi.usc.edu/database/ (2024).

Yu, W. et al. Mar20: A benchmark for military aircraft recognition in remote sensing images. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 27(12), 2688–2696. (2022).

Gao, X. et al. A fast and efficient multiple images encryption based on single-channel encryption and chaotic system. Nonlinear Dyn. 108(1), 613–636 (2022).

Kamal, S. T., Hosny, K. M., Elgindy, T. M., Darwish, M. M. & Fouda, M. M. A new image encryption algorithm for grey and color medical images. Ieee Access 9, 37 855–37 865 (2021).

Hwang, S. O., Waseem, H. M., & Munir, N. Billiard quantum chaos: A pioneering image encryption scheme in the post-quantum era. IEEE Access, 12, 85150–85164, (2024).

Şimşek, C., Erkan, U., Toktas, A., Lai, Q. & Gao, S. Hexadecimal permutation and 2d cumulative diffusion image encryption using hyperchaotic sinusoidal exponential memristive system. Nonlinear Dyn. 113(13), 17 177–17 208 (2025).

Alvarez, G. & Li, S. Some basic cryptographic requirements for chaos-based cryptosystems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 16(08), 2129–2151 (2006).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Wassim Alexan, Noha Ehab Methodology: Wassim Alexan Validation: Engy Aly Maher, Mohamed Youssef Supervision: Engy Aly Maher Software: Eyad Mamdouh, Mohamed Youssef, Noha Ehab Visualization: Eyad Mamdouh Writing Original Draft Preparation: Wassim Alexan, Engy Aly Maher, Eyad Mamdouh, Mohamed Youssef, Noha Ehab Writing Review and Editing: Wassim Alexan All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexan, W., Maher, E.A., Mamdouh, E. et al. A chaos-based augmented image encryption scheme for satellite images using Fredkin logic. Sci Rep 15, 37345 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22008-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22008-z