Abstract

Accurate active power prediction in photovoltaic (PV) systems installed at extreme altitudes above 3800 m a.s.l. faces critical challenges due to non-stationary climate variability, monitoring equipment failure, and limitations in conventional prediction models. This study developed a hybrid stacking metamodel to overcome these barriers through a four-stage process: adaptive preprocessing that reconstructs shifted time series, sequential feature selection (SFS), dimensionality reduction with PCA, and ensemble that integrates Lasso/Ridge mathematical regularization with the nonlinear capabilities of LightGBM/CatBoost. The results demonstrate exceptional accuracy: the LightGBM metamodel achieved R² = 99.9858%, MAE 6.76 and MSE 13.66, outperforming CatBoost and OLS models, with stable convergence in < 50 iterations and minimal training-validation discrepancy evidencing the synergy between robust dimensionality reduction (PCA/SFS) and dual stacking architecture (linear + boosting). Concluding that the LightGBM model is presented as the best option to solve the dual challenge of data fragmentation and environmental complexity in mountainous areas, future research could evaluate the generalizability of this model in other geographical contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The massive adoption of PV systems as a renewable energy source has transformed the global energy landscape1,2,3,4,5, driving studies on their performance under extreme weather conditions6,7,8,9. In particular, high-altitude environments > 3800 m a.s.l10,11,12. present unique challenges: high atmospheric variability, non-stationary irradiance, and accelerated component degradation6,7,8,13,14,15,16. Given this, conventional predictive models exhibit limitations in accuracy and generalization17,18, which has motivated the development of machine learning (ML)-based metamodels that combine multiple techniques19,20,21,22,23,24. Recent advances integrate adaptive preprocessing25,26, feature selection27,28,29, and regularization30,31 with algorithms such as LightGBM and CatBoost32,33,34,35,36,37, while stacking approaches leverage synergies between underlying models to improve robustness38,39,40,41,42. However, gaps in reliable prediction under extreme climate variability in mountainous areas persist43,44,45,46,47,48, where the scarcity of quality data exacerbates the problem16. Despite progress in PV metamodels38,39,40,41,42,47,48,49,50, existing studies suffer from three critical limitations in high-altitude environments: (i) insufficient handling of artifacts in monitoring data (losses, redundancies, and time shifts)16,51,52, (ii) underutilization of dimensionality reduction techniques to mitigate noise and spurious correlations27,28,29, and (iii) reliance on stacking architectures with homogeneous base models, limiting ensemble diversity39,40,41. This leads to overfitting in non-stationary weather conditions40,42 and high errors in active power prediction (MAE > 12.24 according to39, RMSE > 47.78 according to41). Furthermore, most models do not incorporate adaptive strategies for fragmented or incomplete data16,51,53, a recurring problem in systems monitored in remote areas14,15.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a robust methodology based on a four-stage process: (1) adaptive data preprocessing; (2) sequential feature selection (SFS), a key technique for overcoming the obstacles of missing data, a recurring problem in extreme climate monitoring; (3) principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction and model optimization; and (4) a hybrid stacking ensemble, designed to substantially improve prediction accuracy by combining the regularization of models such as Lasso and Ridge with the predictive agility of LightGBM and CatBoost. This approach not only seeks to contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge but also offers practical implications for improving the efficiency and planning of photovoltaic systems in the challenging conditions of mountainous regions. Therefore, the main objective of this research was:

To develop and validate a high-precision active power prediction metamodel for photovoltaic (PV) systems installed at extreme altitudes.

Methodology

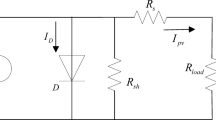

Photovoltaic array

The photovoltaic system was installed at 3,800 m above sea level and consists of a grid-tied photovoltaic system that uses SolarEdge P370 DC-DC optimizers on each of the 8 ERA SOLAR model ESPSC 370, 370 Wp monocrystalline photovoltaic modules, with an installed capacity of 2,960 watts, connected to a 3 kW SolarEdge model SE3000H HD-Wave single-phase inverter.

Data description and preprocessing

In order to guarantee data acquisition, the system was monitored using high standards such as “IEC 60904-154 “Measurement of photovoltaic current-voltage characteristics” and IEC 61724-155 “Monitoring of photovoltaic system performance”, which were key to ensuring adequate data acquisition. This system, to measure voltage and current on the direct current side, used ZELIO ANALOG transducers of the SCHNEIDER brand that sent the captured information to the PLC. For the metrics on the AC side, a HIKING TOMZN power meter was used that monitors information on current, voltage, active power, reactive power, COS, frequency, total energy in positive and inverse kWh with IEC 62053 − 2156 " The requirements for alternating current active energy meters”. This information was also sent to the SIEMENS LOGO PLC, via the RS 485 Modbus industrial communication protocol. Finally, the software was configured in LabVIEW, which received the information contained in the PLC via Modbus RS485.

The instantaneous prediction approach adopted in this study was specifically designed to address the operational requirements of grid-tied photovoltaic systems at extreme altitudes, where real-time power forecasting is essential for inverter control and grid stability. Unlike time series models that require continuous historical data sequences, our approach maintains functionality with incomplete datasets, a critical advantage in remote monitoring environments where communication failures and equipment malfunctions frequently occur. This design philosophy enables immediate deployment in new installations without historical data accumulation periods, while the computational efficiency (convergence in < 50 iterations) allows implementation on resource-constrained edge computing devices typical of remote mountainous installations.

Model description

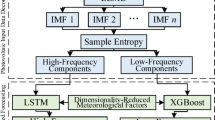

To carry out the two prediction metamodels for a PV system under extreme high-altitude conditions, four elements were used: Data Processing, Sequential Feature Selector (SFS), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Stacking using CatBoost and LightGBM, which are detailed in the general flowchart in Fig. 1.

As you can see in Fig. 1 First, we pre-processed the data acquired from the sensors into a single dataset so that everything was sorted before applying SFS and PCA. Then, with the SFS, we test the combinations to choose the most important variables and reduce the size of the dataset, which helps the regression model not drown in irrelevant data. Then, with the PCA, we transform everything into new, uncorrelated variables (the principal components) that capture the essence of the data, improving clarity and avoiding overfitting. And finally, we used stacking with CatBoost and LightGBM as level 2 models, but before that we trained level 1 models like Lasso and Ridge (with their regularizations) using PCA components.

The following metrics were used to determine the performance of the two proposed metamodels:

-

Score train and score test: which indicates at what level from 0 to 1 the generalized model or adjusted to the training and test data is obtained. If the model fits the data so well with a lot of variances, this causes an overfit, which leads to a bad result in the test score, as the model was too curved to fit the training data and generalized very poorly.

-

MAE: Represents the average of the absolute difference between the actual and predicted values in the dataset. It is calculated with Eq. (1) where N is the total number of data processed, is the actual data, and is the predicted data.\(\:{y}_{i}\)49.

-

MSE: Represents the average of the squared difference between the original and predicted values in the dataset. Measure the variance of residuals. Its value was calculated using Eq. (2)49.

-

RMSE: It represents a measure of the average magnitude of errors in a model’s predictions. It is calculated as the square root of the average of the squared errors and is calculated using the Eq. (3)49.

-

nRMSE: This is a unitless metric, allowing for a direct comparison of the accuracy of models, even if they are predicting variables with very different units or ranges. The following equation represents the normalization by the range of observed values and is calculated using Eq. (4)49.

-

Determination: represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the linear regression model. Its value was calculated using Eq. (5)49.

-

Adjusted Determination: It is adjusted according to the number of independent variables in the model and will always be less than or equal to R². Eq. (6) was used for calculation. In the following formula, n is the number of observations in the data and k is the number of independent variables in the data49.

Two important blocks to ensure the generalization of the model are the Sequential Feature Selector and the Principal Component Analysis. Both blocks are detailed in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2 the flowchart begins with the identification of the dependent variable: “AC_Power” and the independent variables: Date, Time, AC_Current, AC_Voltage, AC_Apparent_Power, AC_Reactive_Power, AC_Power_Factor, DC_Voltage, AC_Frequency, DC_Power, DC_Current”. Performance was evaluated to establish a benchmark for model development. The characteristics or variables were added to the model one by one, and the performance was evaluated. If there was improvement, the variable was selected, and the model was repeated until all the independent variables were exhausted. The process stopped when the optimal number of variables for the system was selected. PCA was then applied to reduce the dimensionality by considering the representation of the variability of the original data with respect to the new data generated by the PCA algorithm until an acceptable threshold in this variability was found. To do this, the data provided by the FSS were introduced and standardized by subtracting mean and dividing by the standard deviation, ensuring that each characteristic contributes equally to the analysis. The covariance matrix was calculated to determine the linear relationships between the features. The values and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix were calculated. Eigenvalues indicate the amount of variance that a principal component captures in the data. The eigenvalues were then sorted in descending order with their eigenvectors, to identify which components capture most of the variance in the data. Subsequently, the number of principal components was selected according to the criterion of variance. In addition, the original data was transformed into the space defined by the selected eigenvectors, resulting in a new dataset (number of components) that captures most of the relevant information from the original dataset. This transformation reduces dimensionality, improves performance, reduces noise, and improves visualization.

Figure 3 shows that the process to create the metamodel represented by the assembly stacking model block begins with feature selection with SFS, and then the dimensionality of the variables is reduced with PCA to train the Ridge and Lasso models. Training both models generates data that will be the input for the Level 2 stackup models: CatBoost and LightGBM. Finally, the results obtained were compared to determine the best metamodel to predict the data of the CC system.

Results

Data pre-processing

To implement the prediction metamodels, the hosted Google Colab Jupyter Notebook service was used with the following characteristics: Processor: Intel® Xeon® CPU @ 2.20 GHz, RAM: 12.7 GB and hard disk: 107.7 GB.

For the generation of the model, 92,964 records were used, which are made up of the following fields or variables: ‘Date’, ‘Time’, ‘AC_Current’, ‘AC_Voltage’, ‘AC_Power’, ‘AC_Frequency’, ‘AC_Apparent_Power’, ‘AC_Reactive_Power’, ‘AC_Power_Factor’, ‘DC_Current’, ‘DC_Voltage’, ‘DC_Power’, ‘Date’, ‘AC_Frequency’, ‘DC_Current’. The data were separated into 65% for training and 35% for testing, which corresponds to 60,426 data for training for each variable and 32,538 data for testing, also for each variable.

To develop the prediction metamodels, the data collected from the photovoltaic system were integrated, organized into daily directories generated by the monitoring system, resulting in a data hub presented in Fig. 4 This figure illustrates the initial structure of the dataset, highlighting its complexity and the specificities of the research case study, such as missing values (1.40% on average, according to Table 1), unnamed variables, data displaced by errors in the collection system, and redundancies. During preprocessing, unnamed variables were eliminated, and displaced data were corrected by imputing missing values. These anomalies, common in monitoring systems in extreme altitude conditions, were effectively addressed by combining adaptive preprocessing and dimensionality reduction (SFS and PCA), which allowed the generation of a clean and representative dataset for training predictive models. Figure 4, therefore, represents the starting point of the data cleaning and consolidation process, essential for the robustness of the proposed metamodels.

The complexity observed in Fig. 4 reflects the genuine challenges of data acquisition in extreme altitude environments rather than presentation artifacts. This visualization demonstrates several critical aspects: (i) irregular temporal structure with inconsistent timestamps typical of remote monitoring systems, (ii) variable data density showing periods with complete measurements alternating with significant gaps, and (iii) the necessity for sophisticated preprocessing techniques to handle data fragmentation effectively. The figure represents raw data collected under industrial standards (IEC 60904-1, IEC 61724-1, IEC 62053-21), illustrating why conventional electrical calculations (P = V×I) become unreliable and sophisticated prediction models are essential for maintaining system operability under such challenging conditions.

From Table 1, missing data were analyzed for all variables, with only 1.40% on average. Subsequently, records that did not have full value were deleted.

Table 2 describes the statistics of all the variables to be processed. As a selection criterion, it was determined that the threshold for each variable not to be eliminated is that its coefficient of variation is not greater than 100% and the coefficient of asymmetry does not exceed 4%. This criterion is considered from existing literature. Table 2 shows that all variables meet these two requirements.

The correlation matrix Fig. 5 quantifies interdependencies among electrical variables in the 3800 m.a.s.l. photovoltaic system, revealing critical redundancies that validate our dimensionality reduction strategy. Perfect multicollinearity (|r| = 1.00) between AC_Current, AC_Power, AC_Apparent_Power, and DC_Power confirm operational coupling where current measurements inherently dictate power outputs, justifying the Sequential Feature Selector’s (SFS) elimination of redundant variables to isolate 8 non-collinear predictors. Similarly, near-unity correlations between reactive power metrics (AC_Reactive_Power–AC_Power_Factor: r = 0.93; AC_Reactive_Power–DC_Voltage: r = 0.92) demonstrate harmonic distortion artifacts exacerbated by altitude-induced grid instability, necessitating Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to decompose these spurious relationships into orthogonal components capturing 99.999% variance. Crucially, AC_Frequency’s weak correlations (r ≤ 0.63) with other variables underscore its role as a unique indicator of grid transients, explaining its retention during adaptive preprocessing.

The strategic implementation of Sequential Feature Selection (SFS) directly addresses the multicollinearity challenges evident in Fig. 5 While perfect correlations (|r| = 1.00) between electrical parameters might suggest redundancy, the practical value of our approach becomes apparent in real-world scenarios where sensor failures, communication disruptions, and environmental artifacts create incomplete datasets. The SFS methodology systematically eliminates redundant variables while preserving predictive capability, enabling accurate power forecasting even when primary measurements (current/voltage) are unavailable. This capability is particularly crucial in extreme altitude installations where maintenance access is limited and sensor reliability is compromised by harsh environmental conditions.

Sequential feature selector

To reduce the number of variables, the Sequential Feature Selector was applied in the second stage. For this regularization method, the metric used to determine the optimal number of variables avg_score was used, seeking to find the lowest value in the iteration. The value found was − 165.20, so the optimal variables according to the SFS method were 8: ‘AC_Current’, ‘AC_Voltage’, ‘AC_Apparent_Power’, ‘AC_Reactive_Power’, ‘AC_Power_Factor’, ‘DC_Voltage’, ‘DC_Power’, ‘DC_Current’, as shown in Fig. 6.

Principal component analysis

In the third stage, the reduction of dimensionality was carried out by means of Principal Component Analysis. The result of the application of the analysis is shown in Fig. 7.

By reducing the dimensionality of the original data into principal components, it was verified that the last three components have a variability equal to the original data, so they were discarded, as shown in Fig. 6 and the values in Table 3.

Stacking level 1

Ridge

To obtain the base models (level 1) for stacking processing, the Ridge model was first generated on the components determined by PCA, with the results shown in Table 4.

The importance of the main components is shown in Fig. 8, where it can be seen that the PC3 (21.29%), PC4 (57.39%) and PC5 (20.97%) components are the components that have the greatest influence on the model.

Lasso

In the same way, to obtain the other base model (level 1) for stacking processing, the Lasso model was also generated on the components determined by PCA, the results of which are shown in Table 5.

Similarly, to show the importance of the principal components, Fig. 9 is shown, in which it can be seen that the components PC3(21.35%), PC4(57.53%) and PC5(20.77%) are the components that have the greatest influence on the Lasso model.

To verify that the results of the component analysis were consistent, the statistical analysis of the two models was performed and compared with the original dependent variable, as shown in Table 6.

From the table above, it can be seen that the behavior of the data predicted by Ridge, Lasso and the original dependent variable does not present any notable anomalies or differences. Based on the Lasso and Ridge Level 1 models, the Stacking Level 2 models were generated for the development of prediction metamodels for a photovoltaic system under extreme altitude conditions.

Stacking level 2

At this level see Fig. 10, the CatBoost model after applying the stacking shows that Ridge contributes 60% to the metamodel, while Lasso contributes 40%. Similarly, after applying level 2 stacking using LightGBM to generate the metamodel, the results show that the Lasso model contributes 55% to the metamodel, while the Ridge model contributes 45%.

Figure 11 shows the evolution of the MSE during training of the LightGBM model. Evidencing a rapid decline in the first 50 iterations, stabilizing around 13.66 (MSE) in the test set. The slightest discrepancy between the training curves (solid line) and validation (dotted line) confirms the robustness of the model against overfitting. Compared to CatBoost and OLS (Fig. 13), LightGBM not only achieves lower error values, but also requires fewer iterations to converge, thus optimizing computational resources. Additionally, the figure was manually validated to correct minor distortions generated by automated tools, guaranteeing the reliability of their graphical representation.

Figure 12 illustrates the evolution of the Coefficient Determination of the LightGBM model during training (blue line) and validation (orange line). The R2 reaches a stable value of 0.999858 in the test set after 150 iterations, explaining virtually all the variance in the data. The rapid convergence (before iteration 50) and the close proximity between the two curves confirm that the model is not only accurate, but also generalizable. Compared to CatBoost and OLS (Fig. 12), LightGBM outperforms R2 points by 0.0011 and 0.0071, respectively, highlighting its suitability for complex environments. It should be noted that the figure was manually refined to correct minor deviations in the axes, ensuring accurate interpretation.

Metamodel comparison

Comparing the performance of the two developed metamodels, as well as the reference or base OLS model, Fig. 13, where it shows the results for the following metrics: Score, Coef. of determination and Coef. and it can be observed that the LightGBM model has a score of 99.9858%, while the CatBoost has a lower performance with a score of 99.9848%, as well as the OLS model that reaches 99.9787%. It can also be seen that the LightGBM model exhibits a determination coefficient of 99.9858, while the CatBoost metamodel shows inferior performance with a score of 99.9848%. Similarly, the Ordinary Linear Regression (OLS) model achieves a lower score of 99.9787%. Finally, it can be seen that the LightGBM model exhibits an Adjusted Coefficient of Determination score of 99.9858%, while the CatBoost metamodel shows inferior performance with a score of 99.9848%, similar to the OLS model, whose score only reaches 99.9787%.

In Fig. 14 illustrates the comparative performance of the LightGBM, CatBoost, and ordinary least squares (OLS) models in predicting active power for photovoltaic systems under extreme high-altitude conditions. The LightGBM model demonstrates superior performance with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 6.7601, a mean squared error (MSE) of 13.6614, a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 14.24, and a normalized RMSE (nRMSE) of 0.01, outperforming the CatBoost metamodel, which exhibits an MAE of 7.2036, an MSE of 14.1517, an RMSE of 14.52, and an nRMSE of 0.01. In contrast, the OLS model achieves an MAE of 4.7180, an MSE of 16.24, and comparable RMSE and nRMSE values that reflect lower predictive accuracy. These metrics highlight LightGBM’s enhanced capability to fine-tune predictions and capture complex data patterns in challenging environmental contexts, underscoring its effectiveness for accurate power forecasting in high-altitude photovoltaic systems.

Therefore, it is concluded that the LightGBM metamodel is the most suitable for making predictions for the photovoltaic system because it has better values in the metrics, as well as shorter training and prediction time.

Discussion

Table 7 presents the results of previous studies related to this research work, providing details on the algorithms used, the performance metrics used, and the values obtained.

From Table 7, it is indicated that the analysis of the results obtained with the proposed metamodel based on LightGBM demonstrates its superiority over other models and approaches presented in the literature. The metamodel achieved a Test Score and an Adjusted Coefficient of Determination of 99.9858%, values significantly higher than those reported by other studies, such as the use of artificial neural networks combined with XGBoost and LSTM, which achieved an adjusted coefficient of determination of 0.9840, in the same way it exceeds the value of 90.58% obtained by50 that used a network combining XGBoost, CatBoost, LGBM and RF. Likewise, the proposed model exceeds the value obtained by47 of 96.2% obtained by combining the following algorithms: Stacked LSTM Sequence to Sequence Autoencoder hybrid DL. This result underscores the effectiveness of the LightGBM Stacking approach in accurately predicting energy production under extreme high-altitude conditions. In terms of mean square error (MSE), the LightGBM metamodel showed a value of 13.6614, considerably lower than the MSE of 29 reported in models combining convolutional neural networks and LSTM42, and much lower than the MSE of 2283.18 achieved by other models such as XGB, LGB, and RF41. This indicates a greater ability of the proposed metamodel to minimize prediction errors. In addition, the MAE of the LightGBM metamodel was 6.7601, which represents a marked improvement over the MAE of 12.24 observed in the studies using Random Forest, XGBoost and AdaBoost39 and also better than the 8.59 obtained with artificial neural networks combined with SVM and LSTM48.

Practical applications and model utility

Our model offers practical and valuable solutions for high-altitude solar systems. It enables smarter predictive maintenance by identifying critical sensors, reducing operating costs. Furthermore, the system is fault-tolerant, maintaining exceptional accuracy (R2 = 99.9858%) even with partial sensor data, thus ensuring continuous operation. This instantaneous prediction capability is crucial for real-time grid integration and management of mountainous microgrids, while its computationally lightweight design enables deployment on resource-constrained edge devices.

Data fragmentation challenges in extreme altitude monitoring

Photovoltaic systems above 3,800 m face unique monitoring challenges due to harsh environmental conditions and limited access, resulting in common data fragmentation (an 8.03% loss in our study). Traditional predictive approaches, which require comprehensive data sets, are ineffective in these circumstances. To overcome this, our hybrid stacking method is specifically designed to handle this incomplete information, maintaining high predictive accuracy and ensuring continuous system operation regardless of the sensor status.

Conclusions

Reliable active power prediction in photovoltaic systems at extreme altitudes above 3800 m a.s.l. faces critical limitations due to non-stationary climate variability, monitoring data loss (8.03% loss in AC_Frequency/DC_Current, temporal shifts), and overfitting in conventional models (MAE > 12.24 in previous studies). Faced with this, this study developed and validated a high-accuracy metamodel through a four-stage process: adaptive preprocessing for series reconstruction, sequential feature selection (SFS) that identified 8 optimal predictors, dimensionality reduction with PCA (capturing 99.999% of variance with 5 components), and hybrid stacking that integrates Lasso/Ridge regularization with the nonlinear capability of LightGBM/CatBoost. The results demonstrate exceptional accuracy: the LightGBM model achieved R² = 99.9858%, MAE = 6.7601 and MSE = 13.6614, significantly outperforming CatBoost (MAE: 7.2036) and OLS (MSE: 16.24), with stable convergence in < 50 iterations and minimal training-validation discrepancy. The novelty lies in the algorithmic synergy that combines mathematical rigor (PCA for component orthogonality) and computational flexibility (boosting for nonlinearities), solving the dual challenge of fragmented data and environmental complexity. This approach allows managing PV systems in mountains with climatic uncertainty (CV < 82.98% in key variables), optimizing grid integration in remote areas. Future research should validate the model in high-irradiation deserts, incorporate autoencoders for unsupervised fault detection, and develop fault-tolerant hardware to mitigate acquisition artifacts.

Data availability

The datasets produced and analyzed in this study are publicly available on Kaggle and can be accessed freely at [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/antony171060/photovoltaic-system-in-extreme-altitude-conditions] (https:/www.kaggle.com/datasets/antony171060/photovoltaic-system-in-extreme-altitude-conditions).

References

Ashraf, M. et al. Recent trends in sustainable solar energy conversion technologies: Mechanisms, Prospects, and challenges. Energy Fuels. 37, 6283–6301 (2023).

Khare, V., Chaturvedi, P. & Mishra, M. Solar energy system concept change from trending technology: A comprehensive review. e-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy. 4, 100183 (2023).

Victoria, M. et al. Solar photovoltaics is ready to power a sustainable future. Joule 5, 1041–1056 (2021).

Frehner, A., Stucki, M. & Itten, R. Are alpine floatovoltaics the way forward? Life-cycle environmental impacts and energy payback time of the worlds’ first high-altitude floating solar power plant. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 68, 103880 (2024).

Kay Lup, A. N. et al. Sustainable energy technologies for the global south: challenges and solutions toward achieving SDG 7. Environ. Sci. : Adv. 2, 570–585 (2023).

Tawalbeh, M. et al. Environmental impacts of solar photovoltaic systems: A critical review of recent progress and future outlook. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 143528 (2021).

L.T.A. & T., I. Environmental factors and the performance of PV panels: an experimental investigation. Afr. J. Environ. Nat. Sci. Res. 6, 231–247 (2023).

Shaik, F., Lingala, S. S. & Veeraboina, P. Effect of various parameters on the performance of solar PV power plant: a review and the experimental study. Sustainable Energy res. 10, 6 (2023).

Sweeney, C., Bessa, R. J., Browell, J. & Pinson, P. The future of forecasting for renewable energy. WIREs Energy Environ. 9, e365 (2020).

Zhang, L., Zhu, W., Du, H. & Lv, M. Multidisciplinary design of high altitude airship based on solar energy optimization. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 110, 106440 (2021).

Huaquipaco Encinas, S. et al. Latin American and caribbean consortium of engineering institutions,. modeling and prediction of a multivariate photovoltaic system, using the multiparametric regression model with shrinkage regularization and extreme gradient boosting. In Proceedings of the 19th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education, and Technology: Prospective and trends in technology and skills for sustainable social development Leveraging emerging technologies to construct the future https://doi.org/10.18687/LACCEI2021.1.1.557 (2021).

Cruz, J. et al. Predictive hybrid model of a grid-connected photovoltaic system with DC-DC converters under extreme altitude conditions at 3800 meters above sea level. PLoS One. 20, e0324047 (2025).

Chitturi, S. R. P., Sharma, E. & Elmenreich, W. Efficiency of photovoltaic systems in mountainous areas. in IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCON). 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ENERGYCON.2018.8398766 (IEEE, 2018).

Martinez-Martinez, Z. & Orellana-Lafuente, R. J. & Sempertegui- Tapia, D. F. Comparative Analysis of Power Generation Between Concentrated Solar Power and Photovoltaic Systems Under High Altitude Conditions. in International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET). 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECET58911.2023.10389354 (IEEE, 2023).

Quinde-Abril, M., Calle-Siguencia, J. & Amador Guerra, J. Design of a photovoltaic system for self-consumption in buildings at high-altitude cities located in the equator. In Communication, Smart Technologies and Innovation for Society (eds. Rocha, Á., López-López, P. C. & Salgado-Guerrero, J. P.) 252 433–443 (Springer, 2022).

Eyring, N. & Kittner, N. High-resolution electricity generation model demonstrates suitability of high-altitude floating solar power. iScience 25, 104394 (2022).

Krechowicz, A., Krechowicz, M. & Poczeta, K. Machine learning approaches to predict electricity production from renewable energy sources. Energies 15, 9146 (2022).

Iheanetu, K. J. Solar photovoltaic power forecasting: A review. Sustainability 14, 17005 (2022).

Brooks, J. D. & Mavris, D. N. Metamodels to enable renewable energy system consideration within thermal and electrical systems optimization. Energy Nexus. 10, 100190 (2023).

Pourmohammadi, P. & Saif, A. Robust metamodel-based simulation-optimization approaches for designing hybrid renewable energy systems. Appl. Energy. 341, 121132 (2023).

Li, P., Zhou, K., Lu, X. & Yang, S. A hybrid deep learning model for short-term PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy. 259, 114216 (2020).

Mubarak, H. et al. A hybrid machine learning method with explicit time encoding for improved Malaysian photovoltaic power prediction. J. Clean. Prod. 382, 134979 (2023).

Mayer, M. J. Benefits of physical and machine learning hybridization for photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 168, 112772 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Photovoltaic power forecasting with a hybrid deep learning approach. IEEE Access. 8, 175871–175880 (2020).

Macaire, J., Zermani, S. & Linguet, L. New feature selection approach for Photovoltaïc power forecasting using KCDE. Energies 16, 6842 (2023).

Mellit, A., Massi Pavan, A., Ogliari, E., Leva, S. & Lughi, V. Advanced methods for photovoltaic output power forecasting: A review. Appl. Sci. 10, 487 (2020).

Meyers, B. E. Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Analysis of Daily PV Power Signals. in IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC). 1217–1221 https://doi.org/10.1109/PVSC43889.2021.9518762 (IEEE, 2021).

Hao, P., Zhang, Y., Lu, H. & Lang, Z. A novel method for parameter identification and performance Estimation of PV module under varying operating conditions. Energy. Conv. Manag. 247, 114689 (2021).

Niu, D., Wang, K., Sun, L., Wu, J. & Xu, X. Short-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting based on random forest feature selection and CEEMD: A case study. Appl. Soft Comput. 93, 106389 (2020).

Shi, J., Li, C. & Yan, X. Artificial intelligence for load forecasting: A stacking learning approach based on ensemble diversity regularization. Energy 262, 125295 (2023).

Incremona, A. & Nicolao, G. D. Regularization methods for the short-term forecasting of the Italian electric load. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 51, 101960 (2022).

Zhang, L. & Jánošík, D. Enhanced short-term load forecasting with hybrid machine learning models: catboost and XGBoost approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 241, 122686 (2024).

Banik, R., Biswas, A. & Improving Solar, P. V. Prediction performance with RF-CatBoost ensemble: A robust and complementary approach. Renew. Energy Focus. 46, 207–221 (2023).

Peng, Y. et al. LightGBM-Integrated PV power prediction based on Multi-Resolution similarity. Processes 11, 1141 (2023).

Park, S., Jung, S., Jung, S., Rho, S. & Hwang, E. Sliding window-based LightGBM model for electric load forecasting using anomaly repair. J. Supercomput. 77, 12857–12878 (2021).

Liao, S. et al. Short-Term wind power prediction based on LightGBM and meteorological reanalysis. Energies 15, 6287 (2022).

Fraccanabbia, N. et al. Solar Power Forecasting Based on Ensemble Learning Methods. in. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN48605.2020.9206777 (IEEE, 2020).

Chakraborty, D., Mondal, J., Barua, H. B. & Bhattacharjee, A. Computational solar energy – Ensemble learning methods for prediction of solar power generation based on meteorological parameters in Eastern India. Renew. Energy Focus. 44, 277–294 (2023).

Abdellatif, A. et al. Forecasting photovoltaic power generation with a stacking ensemble model. Sustainability 14, 11083 (2022).

Khan, W., Walker, S. & Zeiler, W. Improved solar photovoltaic energy generation forecast using deep learning-based ensemble stacking approach. Energy 240, 122812 (2022).

Zhang, H. & Zhu, T. Stacking model for Photovoltaic-Power-Generation prediction. Sustainability 14, 5669 (2022).

Elizabeth Michael, N., Mishra, M., Hasan, S. & Al-Durra, A. Short-Term solar power predicting model based on Multi-Step CNN stacked LSTM technique. Energies 15, 2150 (2022).

El Bourakadi, D., Ramadan, H., Yahyaouy, A. & Boumhidi, J. A novel solar power prediction model based on stacked BiLSTM deep learning and improved extreme learning machine. Int. j. inf. Tecnol. 15, 587–594 (2023).

Alghamdi, A. A., Ibrahim, A., El-Kenawy, E. S. M. & Abdelhamid, A. A. Renewable energy forecasting based on stacking ensemble model and Al-Biruni Earth radius optimization algorithm. Energies 16, 1370 (2023).

Moon, J., Jung, S., Rew, J., Rho, S. & Hwang, E. Combination of short-term load forecasting models based on a stacking ensemble approach. Energy Build. 216, 109921 (2020).

Xia, M., Shao, H., Ma, X. & De Silva, C. W. A stacked GRU-RNN-Based approach for predicting renewable energy and electricity load for smart grid operation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 17, 7050–7059 (2021).

Ghimire, S. et al. Stacked LSTM Sequence-to-Sequence autoencoder with feature selection for daily solar radiation prediction: A review and new modeling results. Energies 15, 1061 (2022).

Lateko, A. A. H. et al. Stacking ensemble method with the RNN Meta-Learner for Short-Term PV power forecasting. Energies 14, 4733 (2021).

Gasser, P. et al. A review on resilience assessment of energy systems. Sustainable Resilient Infrastructure. 6, 273–299 (2021).

Guo, X., Gao, Y., Zheng, D., Ning, Y. & Zhao, Q. Study on short-term photovoltaic power prediction model based on the stacking ensemble learning. Energy Rep. 6, 1424–1431 (2020).

Cross-validation of. The operation of photovoltaic systems connected to the grid in extreme conditions of the highlands above 3800 meters above sea level. IJRER https://doi.org/10.20508/ijrer.v12i2.12570.g8490 (2022).

Soomar, A. M. et al. Solar photovoltaic energy optimization and challenges. Front. Energy Res. 10, 879985 (2022).

Cruz, J. et al. Multiparameter regression of a photovoltaic system by applying hybrid methods with variable selection and stacking ensembles under extreme conditions of altitudes higher than 3800 meters above sea level. Energies 16, 4827 (2023).

IEC. IEC 60904-1 Measurement of photovoltaic current-voltage characteristics. (2020).

IEC. IEC 61724 Monitoring of photovoltaic system performance. (2021).

IEC. IEC 62053-21 This standard defines the requirements for static meters for AC active energy. (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Escuela Profesional de Ingeniería en Energías Renovables de la Universidad Nacional de Juliaca, the Facultad FIMEES de la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, and the Escuela Profesional de Ingeniería de Sistemas e Informática de la Universidad Nacional de Moquegua for their contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saul Huaquipaco: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Wilson Mamani: Software, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation; Norman Beltran: Resources, Project administration; Jose Ramos: Investigation, Resources, Visualization; Vilma Sarmiento: Writing – original draft, Data curation; Pedro Puma: Software, Validation, Formal analysis; Reynaldo Condori: Formal analysis, Validation, Software; Henry Pizarro: Methodology, Visualization; Victor Yana-Mamani: Supervision, Funding acquisition; Jose Cruz: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huaquipaco, S., Mamani, W., Beltran, N. et al. Optimizing photovoltaic power prediction at extreme altitudes using stacking metamodels and dimensionality reduction. Sci Rep 15, 38423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22185-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22185-x