Abstract

Xinjiang is located in the hinterland of the Asia-Europe continent, neighboring Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and is a bridgehead for China’s eastward connection to the west, and the classification of Central Asian language emotions has become a development focus under the Belt and Road Initiative in Xinjiang. This paper takes the Kazakh versions of CHINA DAILY of Xinjiang News and SILK ROAD of Asia-Europe News as the source of the Central Asian language corpus and constructs an important corpus and online retrieval platform. Under the Transformer architecture, Word2Vec-TF-IDF and BERT models are used to train Central Asian regional language word vectors and construct word vector features, respectively. The word vector features obtained from the language pre-training model are used as inputs to obtain the local features of the Central Asian languages using multi-channel convolutional CNN, and the global features of the Central Asian languages are extracted by combining with the bi-directional GRU model. Then the fusion of local features and global features is carried out through the attention mechanism, and the SoftMax classifier outputs the classification results of sentiment tendency of Central Asian languages. The sentiment classification model designed in this paper achieves better classification results than other models on the Central Asian regional language corpus, and its accuracy can reach 92.78%, 91.45%, 93.54%, and the training time in classifying the sentiment of Central Asian regional languages using the model in this paper is 359.71 s. Using the language model as the basis of the Central Asian regional language sentiment classification can help Xinjiang Belt and Road Initiative implementation process to understand language sentiment changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sentiment classification, also known as viewpoint identification, sentiment mining and propensity analysis, is usually a process of analyzing and inferring texts with subjective emotional color1,2. With the rapid development of Internet technology and the popularization of Internet applications, today’s society has entered the era of information explosion, more and more users are accustomed to expressing their views and ideas on online platforms, which accumulates a huge amount of data, and sentiment classification of these data can better grasp people’s emotional tendencies and mine the potential information behind them, so that it can more effectively provide decision makers with opinions and suggestions for decision makers more effectively3,4,5,6,7. Currently, sentiment classification has been applied in the fields of public opinion analysis, recommendation system and business decision-making8,9.

In recent years, the languages of Central Asia have great potential for application, attracting extensive attention from many researchers and generating a large number of high-quality linguistic affective resources, thus laying a solid foundation for the rapid development of affective categorization in the field of English10,11,12,13,14,15. The uneven distribution of sentiment resources has led to constraints on the development of languages with scarce sentiment resources16,17,18,19. This status quo has led to the birth of linguistic sentiment classification models. Cross-language sentiment classification is to use the resource-rich source language to help the resource-poor target language to realize sentiment classification, i.e., to use labeled source language data to train sentiment classifiers and make this model well applicable to target language data sentiment classification, so as to solve the problem of imbalanced distribution of sentiment resources in different languages and to cross the gap between languages20,21,22,23,24,25.

Deep learning has become the backbone of multilingual sentiment analysis for under-resourced languages. Reference26 introduces a high-performance framework that bypasses machine translation entirely, enabling direct sentiment inference on low-resource corpora. Reference27 highlights how linguistic complexity and data scarcity limit prior work; to overcome this, the authors integrate transformer blocks and demonstrate superior predictive accuracy on mixed-language texts. Reference28 couples lexicon creation, expansion, annotation and fine-tuning into a unified pipeline; the resulting model attains high accuracy on a target-language tweet corpus and generalises well to other resource-poor settings. Reference29 develops and deploys transformer-based language models for diverse yet under-resourced languages, achieving reliable sentiment predictions and helping to narrow the global digital-language divide. Reference30 benchmarks transformer architectures across several low-resource scenarios, revealing that AfriBERTa delivers robust performance and high accuracy on curated datasets.

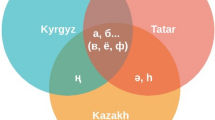

Central-Asian languages such as Kazakh, Uzbek and Urdu remain under-served in sentiment analysis. Recent studies have begun to close this gap. Annotated corpora for Uzbek31 and Turkish32 show that deep models outperform classical ones at the cost of longer training. Roman-Urdu, the third most used online language, has been analysed with unsupervised polarity lexicons after spelling normalisation33. Context-aware systems have improved Urdu sentiment capture beyond bag-of-words34. Benchmark datasets now allow fair comparison of n-gram, fastText and BERT encoders for Urdu35,36. Hybrid quantum–machine-learning pipelines have also shown promise on Arabic data37. These studies converge on two key requirements: high-quality annotated resources and context-sensitive architectures. Building on these insights, we focus on Kazakh—the lingua franca of China’s Xinjiang border region—and introduce a Transformer-based framework that fuses BERT-derived contextual embeddings with multi-channel CNN and bidirectional GRU encoders, setting a new state of the art for Central-Asian sentiment classification.

Uzbek, Turkish, Roman-Urdu, Urdu, and Arabic all face the same challenge: sentiment analysis can be biased when data is scarce. A research team created a richly annotated Uzbek corpus and trained polarity classifiers covering both classical machine learning and deep neural networks31. Another group of researchers compared these two paradigms on Turkish Twitter data; classical models completed training earlier, but deep architectures achieved higher accuracy32. Roman Urdu, as the third most widely used language online, now has an unsupervised vocabulary that annotates normalized stems and words before sentences are classified as positive, negative, or neutral33. Urdu sentiment analysis based on bag-of-words models and traditional learners struggles with subtle emotional nuances; thus, context-aware models were designed to capture a broader semantic scope and improve accuracy34. A carefully curated Urdu benchmark dataset enables systematic evaluation of n-grams, fastText, and BERT encoders; currently, models combining word-level n-grams with logistic regression lead the field35. A second manually annotated Urdu dataset covering various categories of user reviews compared four text representation methods—word n-grams, character n-grams, pre-trained fastText, and BERT embeddings—to identify the most powerful sentiment classifier36. Finally, a hybrid quantum-machine learning pipeline has been tested on Arabic sentiment tasks; quantum circuits perform excellently on large-scale corpora, while traditional learners remain robust on smaller datasets37.

Sentiment categorization based on Central Asian languages has become an important means to understand the change of sentiments in foreign communication, which is an important guarantee to promote the wide implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative in Xinjiang. The article chooses CHINA DAILY of Xinjiang News and SILK ROAD of Asia-Europe News as corpus sources, constructs a corpus of Central Asian languages through transcription and annotation of the corpus, and builds a web search platform for the corpus. Word2Vec is used to train the word vectors of Central Asian languages, and TF-IDF is used to optimize the word vector weight features, and the BERT language pre-training model is combined to construct the word vector features of Central Asian languages. A multi-channel convolutional neural network (CNN) is combined with a bidirectional recurrent unit (GRU) to extract local n-gram patterns and global sequence dependencies from Central Asian sentiment texts. An attention mechanism is then applied for feature fusion, and finally, a SoftMax classifier is used to generate sentiment labels. Comprehensive simulation experiments validate the excellent accuracy of the proposed language model-driven framework on Central Asian corpora.

Building a corpus of central Asian languages

The establishment of a Central Asian language corpus can help to enhance the precise categorization of linguistic emotions in Central Asia and promote the cross-cultural adaptability of linguistic communication in Central Asia.

Source and labeling of the corpus

Source and size of corpus

Reliable conclusions require a training corpus that is reasonably representative. Absolute representativeness is impossible to achieve, but the size of the corpus still needs to be considered. A corpus that is too small or poorly selected will reduce the accuracy of vocabulary annotation. Conversely, a corpus that is too small will force the inclusion of additional raw data.In general, the larger the size of the training corpus, the better. However, after the size of the training corpus reaches a certain level, when it is enlarged again, the phenomenon of multiple occurrences of partitives will appear, that is, the frequency of partitives will increase, which does not correctly reflect their actual situation in the language. Therefore it is very important to choose a training corpus that meets the actual requirements.

The corpus used in this paper is the corpus provided by CHINA DAILY of Xinjiang News and SILK ROAD of Asia-Europe News, whose specific size reaches more than 80,000 words. Among them, both corpora are in Kazakh. Moreover, the textual data collection is carried out, which is used as the corpus basis for constructing the Central Asian regional language corpus.

Transcription and labeling of the corpus

The establishment of corpus system is the prerequisite work for all corpus research, the design of corpus and the selection of corpus will affect the quality of corpus-based research work to be done later, and the merits of its results are related to the quality of its construction. Therefore, in order to standardize the construction of the corpus of Central Asian languages, this paper firstly formulates the principles of labeling specifications for the corpus of Central Asian languages as follows:

(1) Processing and depth specification.

Corpus processing involves two tasks: format conversion and detailed description. These steps are tailored to the linguistic traits of Central Asia. First, letter and word frequencies are computed. Next, morphological segmentation and reduction are applied. After that, stems and full word forms receive lexical labels. Finally, basic phrase boundaries are annotated. The resulting specifications provide users with rich linguistic information about the Central Asian region.

(2) Storage and encoding specifications.

This corpus has issues with inconsistent input methods and file formats. To achieve efficient management and seamless sharing, we use XML as the main container format and UTF-8 encoding as the standard. This choice ensures the complete description of metadata and enhances the reusability of Central Asian language resources. Each annotated file is stored in two parallel formats: XML for structural description and TXT for lightweight access.

General design of the corpus

Process of Building a central Asian corpus

A corpus of Central Asian languages has been created. Statistical methods were used to generate stem lists and suffix lists for each target language. The same statistical methods were also used to generate lexical analysis rules. These resources were then combined with natural language processing algorithms. The end result is an automated system capable of performing lexical analysis and suffix classification on Central Asian languages.Finally, we apply the Unified Juice Model to improve the program of lexical analysis and word-final classification of Central Asian languages. Finally, the automatic morphological analysis system of Central Asian languages and the corpus of Central Asian languages are established38. Figure 1 shows the construction process of the Central Asian language corpus.

(1) Manual entry to construct a lexicon of Central Asian languages and construct a stem list, and construct a list of Central Asian language affixes according to the grammar rules of Central Asian languages. The original corpus of Central Asian languages collected from sources such as CHINA DAILY of Xinjiang News and SILK ROAD of Asia-Europe News is used to preprocess the collected documents.

(2)We have developed a pipeline for automatic lexical analysis of Central Asian corpora. The program consults stem, suffix, and affix dictionaries, applies suffix stripping rules, and handles irregular variants. It outputs stem-suffix pairs with lexical tags in UTF-8 format TXT and XML files.

(3) Combining rules and statistical models to extract stems and cut word endings, and classify word endings in the original corpus copies of Central Asian languages using the two-way full cut method.

(4) Integrate the functions to realize the system of lexical annotation and word-final classification of the languages of Central Asia, establish a modern corpus of the languages of Central Asia, apply the established corpus to the grammatical research of the languages of Central Asia, and analyze the corpus of the languages of Central Asia in terms of sentiment classification.

Corpus web search platforms

The corpus of Central Asian languages is hosted by a MySQL relational database, and customized SQL enables automatic querying by virtue of MySQL’s excellent performance. In addition, the corpus has also built corresponding Web services, which can support accurate or fuzzy query of vocabulary. Its search function not only provides word and full-text search, but also develops an audio resource playback system, which mainly includes full-text indexing, indexing of words in context, word frequency statistics, text indexing, audio indexing, and so on. The retrieval results can simultaneously report the frequency of word usage, lexical properties, the corpus in which it is located, the metadata information of that corpus, etc. The web search platform consists of three pages: three tables query, vocabulary query, and text query.

The “timestamp” is equivalent to the search code of the utterance, and detailed information can be obtained by virtue of the search code. For example, when searching for a certain word, after entering the word in the search box, we can get the “timestamps” of all the sentences containing the word.The corpus model consists of three relational tables—characters, sentences, and analysis—each indexed by a unified timestamp. This identifier serves as the primary key, ensuring complete referential integrity across the entire dataset. By propagating the timestamp across the three tables, the system can accurately retrieve (i) all occurrences of the target lexical item in the text, (ii) the corresponding sentence-level context, and (iii) the speaker’s sociodemographic information. Additionally, by inserting the timestamp into the “text query” interface of the retrieval platform, the system can instantly return text segments associated with the original audio recording, thereby supporting integrated multimodal analysis.

Linguistic sentiment classification model for central Asia

Language plays an important role in maintaining national unity, ethnic identity, and preserving national independence and solidarity. Language development helps establish norms and shared values, enhance appeal, and ultimately shape a country’s cultural soft power.Under China’s Xinjiang Belt and Road Initiative, frequent exchanges between Xinjiang and countries in Central Asia help establish the Silk Road Economic Belt. Clarifying the emotional expression of Central Asian languages in the communication process can significantly enhance the effect of cross-cultural communication.

Language pre-training model

Word2Vec-TF-IDF

Word (stemmed) embeddings are real vectors based on the context in which the word occurs, generated from a corpus by Word2Vec technique. The stemmed vectors generated by Word2Vec training can be used for many natural language processing tasks. The semantic similarity between two stems can be easily determined by calculating the distance between the stemmed vectors of these two stems. There are two main learning algorithms in Word2Vec, i.e., CBOW and Skip-gram algorithms, and in this paper, we mainly use the CBOW algorithm for the training of Central Asian languages word vectors39.

CBOW is to predict the probability \(p\left( {{s_t}|{s_{t - c}}} \right.,\left. {{s_{(t - c) - 1}}, \cdots ,{s_{t - 1}},{s_{t+1}},{s_{t+2}}, \cdots ,{s_{t+c}}} \right)\) of the occurrence of the current stem \({s_t}\) based on the contextual stem \({s_{t - c}},{s_{(t - c) - 1}}, \cdots ,{s_{t - 1}},{s_{t+1}},{s_{t+2}}, \cdots ,{s_{t+c}}\). The CBOW model represents the current stem \({s_i}\) by means of \(c\) contextual stems, \(c\) is the size of the preselection window, and the stem vector for stem \({s_t}\) is obtained after training the text with the CBOW algorithm.

By calculating the cosine distance between the stem vectors formed using the Word2Vec tool to be able to determine the semantic similarity between the stems, the larger the value of the cosine distance between the stem vectors, the higher the semantic similarity of the stems, and vice versa, the lower the semantic similarity.

For the set \(D\) containing individual texts in package \(M\), where \({D_i}\left( {i=1,2, \cdots ,M} \right)\), the stem vectors are obtained by the CBOW model. For each stem in the text, its weight value \(tfidf(t,D)\) is calculated by the \(TF - IDF\) algorithm, which is the weight value of the stem \(t\) in the text \({D_i}\left( {i=1,2, \cdots ,M} \right)\). \(TF - IDF\) Considering the stem frequency \(tf\) in a single text and the stem frequency \(idf\) of the whole text set, \(TF - IDF\) the formula is:

where \(tf\left( {t,{D_i}} \right)\) is the frequency of occurrence of stem \(t\) in the \(i\)rd text and the denominator is the normalization factor. \(idf\left( f \right)\) is the inverse document frequency of stem \(t\), calculated as:

where \(M\) is the total number of texts in the training set and \({n_t}\) is the frequency of occurrence of the stem \(t\) in the training set.

The stem vector for each stem is weighted by \(tfidf\) values to represent a text, i.e.:

BERT Language model

The BERT model is a deep bidirectional language representation model based on Transformer, and its basic structure is shown in Fig. 2. BERT essentially constructs a multi-layer bidirectional encoding network by using the encoder part of the Transformer model structure.

The formula for the self-attention layer can be expressed as:

where \(Q\), \(K\), \(V\) are the query matrix, key matrix, and value matrix, respectively. It can be expressed as:

where \(X\) is the position coding matrix and \(W\) is the corresponding weight matrix.

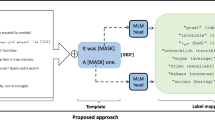

The BERT model employs the techniques of random masking (MLM) and predicting the next sentence (NSP). These two approaches allow the model to consider the context of the text and learn the correlation between the texts. Where BERT uses MLM is to randomly select 15% of the words in the sentence, out of this 15%, 80% of the words are replaced using MASK, 10% are replaced using random words, and 10% are kept unchanged. The NSP technique is to select two sentences, which are 50% likely to be adjacent and 50% likely to be non-adjacent, and let the model to determine whether the two sentences are adjacent or not40.

In order to be able to be applied to more downstream tasks, the inputs to BERT come in two forms, a single sentence alone and a pair of sentences. Each input starts with [CLS], and the output position corresponding to [CLS] serves as a marker for the classification task. For a pair of sentences, two sentences are spliced together to form a single sentence, separated by the [SEP] symbol. The model uses the Transformer architecture, which allows the model to be computed in parallel, greatly improving the computational efficiency. Therefore, the use of the word vector model can lead to a reduction in post-training costs, achieve fast convergence during training, and also improve the performance of the model substantially.

Language sentiment classification model

The overall architecture of the proposed model in this paper is shown in Fig. 3, where the initial text data first passes through the BERT word embedding layer and is converted into a vector form that can be utilized by the neural network. In the feature extraction stage, multi-channel convolutional neural networks capture local N-gram patterns, while bidirectional gated recurrent units encode sequence dependencies in both forward and reverse directions. This dual architecture jointly learns the positional and semantic representations of the input text. Meanwhile, a self-attention mechanism is introduced in each channel to capture the hidden long-distance dependencies and improve the model accuracy. Finally, we enter the classification layer and use SoftMax function to judge the final sentiment polarity through the fully connected network41.

Central Asian Language input layer

The initial text data cannot be directly utilized by the network model, so it is necessary to convert the initial text data into vector form by text word embedding operation. Suppose the original input to the model is a text \({T^c}=\left\{ {t_{1}^{c},t_{2}^{c}, \ldots ,t_{{t+1}}^{c} \ldots t_{{t+m}}^{c}, \ldots ,t_{N}^{c}} \right\}\) consisting of \(N\) consecutive words, where \(t_{i}^{c}\) is the \(i\)th word in the text. The initial text contains aspect words consisting of \(m\) words with subscripts in the text starting from \(t+1\). After obtaining the initial text sequence \({T^c}\), the text is converted into sequence \(se{q_c}=\left\{ {[CLS],t_{1}^{c},t_{2}^{c},t_{3}^{c}, \ldots ,t_{N}^{c},[SEP]} \right\}\) by inserting “\([CLS]\)” and “\([SEP]\)” markers at the beginning and end of the text, respectively. Further the Transformer encoder based BERT pre-trained model is used for word The initial text is converted into a mixture of word vectors, segmentation vectors and position vectors of each word, so that the positional coding information of each word is captured and the contextual information is mined.

The word vectors, segmentation vectors and position vectors of the textual vocabulary are all of the same dimensional size, and they are used to encode information about each vocabulary in the original text sequence. Specifically, the word vector represents a unique vector representation of each vocabulary word in the corpus. Segment vectors are used to determine the sentence or text passage to which each vocabulary belongs, and vocabularies in the same sentence or text passage share the same segment vectors. The position vector, on the other hand, encodes the positional information of each vocabulary word in the original text sequence to help the model learn the sequential relationship between words.

After performing the text-word embedding operation on the vocabulary, the overall text vector representation \({W^c} \in {R^{N \times emb}}\) is obtained, where \(N\) is the text length and \(emb\) is the BERT input layer dimension.

Multi-channel convolutional features

Usually convolutional neural network (CNN) consists of three parts, convolution, pooling and fully connected42.

The structure of the multi-channel CNN model used in this paper has four main layers: input, convolution, pooling and output. The details are as follows:

(1) Input layer.

The CNN network corresponds to the local feature extraction part, which has the same input as the whole sentiment analysis model, i.e., \({V_s}\epsilon {R^{n \times d}}\), where \(n\) represents the input text length and \(d\) represents the dimension of the transformed word vector.

(2) Convolutional layer.

If we assume that the length of the convolutional kernel in the convolutional layer is \(l\), then the space of the convolutional kernel is \({R^{l \times d}}\), for the words in the \(j\)th position in the text, we can derive the size of the window of the convolutional layer \(windo{w_j}\) as:

The setup of the convolution kernel passing through this window gives an eigenvalue \({c_j}=f\left( {{w_j} \circ m+b} \right)\), where \(\circ\) represents the convolution operation and \(f\) represents a nonlinear function. With the convolution kernel w, the output of the convolution layer can be obtained as:

Then it can be obtained that the output vector of multiple convolutional kernels is:

(3) Pooling layer.

In order to find the most valuable local features and reduce the parameters of the fully connected layer, the features extracted from the convolutional layer are maximally pooled using Global Max Pooling1D. Each convolutional kernel outputs a feature vector \(c\), which can be pooled to find a maximum value of \({c_{\hbox{max} }}\). After pooling the outputs of the \(m\) convolutional kernels, a new feature vector \(p \in {R^m}\) is obtained, which is composed of \(m\) and \({c_{\hbox{max} }}\). The entire pooling layer feature screening output feature result of the sentiment propensity analysis model in this chapter is:

(4) Output layer.

The local feature vectors \({p_2}\), \({p_3}\), \({p_4}\), obtained from the pooling layer, need to be spliced to get the final vector of the input text as:

Where \(\left[ : \right]\) represents the splicing operation on the output feature vector of the pooling layer. Finally, the vector \(P\) is then transformed into a high-level text feature vector \({h_{CNN}}\) by nonlinear transformation can be represented as:

where \(\delta\) stands for the sigmoid function, \(W\) stands for the nonlinear transformation parameter, and \(b\) stands for the bias in the nonlinear transformation.

Bidirectional GRU feature extraction

The parameters in GRU can be updated by the following equation, i.e43. :

The final output value of the bi-directional GRU model depends not only on the forward computation process but also on the backward computation process, making the output more accurate.

The formula for calculating each parameter in bi-directional GRU is the same as that of uni-directional GRU, except that the hidden layer feature \({h_t}\) is divided into forward hidden layer feature \(\overline {{{h_t}}}\) and backward hidden layer feature \(\overline {{{h_t}}}\), and the final hidden layer feature \({h_{BiGRU}}=\overline {{{h_t}}} \oplus \overleftarrow {{h_t}}\), \({h_{BiGRU}}\) combines forward and backward hidden layer features, \(\oplus\) is also a splicing operation, and \({h_{BiGRU}}\) is the final context semantic feature information extracted by bi-directional GRU.

The local feature \({h_{CNN}}\) and global feature \({h_{BiGRU}}\) of the Central Asian language text can be obtained after passing through two different feature extraction layers respectively.In this paper, the final feature vector \(h=[{h_{CNN}},{h_{BiGRU}}]\) of the Central Asian language text is obtained by splicing the two features.

Fully connected layer and classification layer

In order to accomplish the judgment of sentiment tendency of text in Central Asian languages, the model in this paper inputs the text representation vector \(h\) of sentence \(s\) into the SoftMax classifier, predicts the probability distribution of sentiment labels of the sentence, and selects the sentiment label with the maximum probability value as the sentiment polarity of sentence \(s\). The SoftMax classifier is computed in the following way:

where \(\tilde {y}\) denotes the probability value of the predicted sentiment label, and \(w_{o}^{T}\) and \({b_o}\) denote the learnable parameters. To train the models in this chapter, we use a cross-entropy loss function in the following form:

where \(N\) denotes the size of the training set, \(c\) denotes the number of different types of sentiment labels, \(y\) denotes the true distribution of sentiment labels, \({\lambda _r}\) denotes the coefficients of \({L_2}\) regularization, and \(\theta\) denotes the set of parameters to be optimized during the training process. All the learnable parameters of the model in this chapter are optimized by stochastic gradient descent strategy, which is defined as:

where \({\lambda _l}\) denotes the learning rate.

Validation of a model for categorizing linguistic sentiment in central Asia

Against the backdrop of the Belt and Road Initiative in Xinjiang, this study explores language development and emotional changes in Central Asia. By leveraging geographical and cultural advantages, we cultivate professional talent and construct a Central Asian language emotion classifier based on deep learning. Relying on previously proposed models and corpora, we conduct rigorous simulation experiments to verify its effectiveness. The research results provide empirical support for promoting the globalization and standardization of Central Asian languages.

Model training validation analysis

Comparative experiments on experimental parameters

In the Central Asian sentiment classification task, model performance is highly sensitive to three key hyperparameters: batch size, maximum sequence length, and training set size. To determine the optimal values for these hyperparameters, we conducted three controlled experiments while keeping all other settings at empirically determined default values.

The statistical results of the emotional corpus in this paper are shown in Supplementary Table S1 Self-built emotional corpus statistics. The corpus contains 11,652 provisions. The goal of this article is to distinguish the emotional polarity of different texts, namely, positive and negative.

In particular, the multivariate properties of the experimental data set are shown in Supplementary Table S2 Multivariate properties of experimental data sets. The experimental material properties are abundant enough to ensure the applicability of this article.

(1) Batch-size.

The batch size defines the number of samples processed in each forward propagation. During training, a small batch is input into the network, the loss between the predicted values and the true labels is calculated, and the gradients are backpropagated to update the model parameters; a complete cycle constitutes one iteration.When the next iteration is performed, the weights of the adjusted network are used as the initial values. The selection of the size of the data volume of each batch is more important and needs to be within a reasonable range; excessive increase in data volume will lead to generalization problems. The purpose of this comparative experiment is to test the effect of different sizes of data volume in each batch on the model effect by changing the size of the number of processes in each batch while other parameters remain unchanged. The maximum precision and recall in multiple trials are used as the main evaluation indexes, and the average time is used as the benchmark. The results of this comparison experiment are shown in Fig. 4.

As can be seen from the graph, although the shortest average time is 21.87s when the Batch-size is 1024, the accuracy and recall are not the highest at this time. The model has the highest sentiment classification accuracy and recall when Batch-size of 512 is selected, with values of 83.34% and 78.34% respectively. This is due to the low precision caused by the convergence difficulty of the model when the number of samples selected is small, and if the number of samples is too large, overfitting occurs and the precision decreases although the speed is accelerated. Therefore, in this experiment, the size of each batch of data volume of the model is set to 512, i.e., Batch-size = 512, while taking into account the model sentiment classification accuracy and time.

(2) Maximum text sequence length and iteration number comparison experiment.

The data used in this paper are the relevant text data of CHINA DAILY of Xinjiang News and SILK ROAD of Asia-Europe News, most of which have different text lengths, but the model requires the same length of utterances, so the length of the maximum text sequence must be handled in a way that is more than enough and less than enough. In the case of insufficient sentence length is supplemented with PAD, and the excess is eliminated. When other parameters are the same, the sentence length is changed through comparison experiments, and the sentence length is set to 90 ~ 220 respectively, with the intention of exploring the effect of different sentence lengths on the model effect, and the number of iterations is set to 1 ~ 20 Epochs to examine the effect of different iterations on the model effect. Taking the maximum accuracy of multiple experiments as the evaluation index, the comparative experimental results of the model are obtained as shown in Fig. 5, where Fig. 5(a)~(b) shows the comparative results of the maximum text sequence length and the number of iterations, respectively.

As can be seen from the figure, the accuracy rate is higher (81.98%) when the sentence length is 160, and most of the texts in the dataset are around 160, so the maximum text sequence length is set to 160 for this experiment.In addition, the accuracy rate is getting higher and higher with the increase of the number of iterations, but when the number of iterations is 14 Epochs, the accuracy rate reaches the maximum value of 67.93, so this experiment sets the number of iterations is set to 14 Epochs.

The optimum experimental parameters for the final determination are shown in Table 1. Experimental parameter design.

Model validation and testing process

For the effectiveness of the Central Asian language sentiment classification model designed in this paper, the model is utilized for the validation and testing process based on the Central Asian language corpus established in the previous paper. Figure 6 shows the validation and testing process of the Central Asian regional language sentiment classification model. For the Central Asian regional language corpus, the model validation accuracy increases steadily in the first 15 rounds, and the model fluctuates within a reasonable range in 16–20 rounds, and finally tends to stabilize. The model of this paper is tested on the Central Asian regional language corpus, and when running to the 18th Epochs, the model classification effect reaches the optimal, at this time, the accuracy of the model’s sentiment classification of the Central Asian regional language is 0.951. On the whole, the model of this paper has a high classification accuracy when carrying out the Central Asian regional language corpus for the sentiment classification, and in the process of the Central Asian region’s communication, it can clarify the sentiment changes of its language sentiment changes, providing reliable technical support for promoting the smooth implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative and expanding China’s international communication capacity.

Optimal integration strategy selection

In the feature fusion stage of GRU and CNN models, to select the optimal multi-feature fusion method, this paper adopted four feature fusion schemes, including concatenation, summation, multiplication (element-wise multiplication), and attention mechanism. Experiments were conducted under identical conditions on the Central Asian language corpus, with test results calculated for each batch of the test set. Accuracy, Macro-R, and Macro-F1 values were used as evaluation metrics to obtain the model performance curves for different feature fusion methods, as shown in Fig. 7, where Figs. 7(a) to (c) respectively display the comparison results for accuracy, Macro-R, and Macro-F1 values.

The experiments on the Central Asian regional language corpus show that when using the attention mechanism for feature fusion, the accuracy rate and Macro-F1 value of the model are optimized, while Macro-R also demonstrates an excellent performance index. The attention mechanism can effectively weight different features, highlight important features and suppress less important information, thus providing more accurate and detailed results when processing complex data. This approach can make full use of GRU’s advantage in time series analysis and CNN’s ability in spatial feature extraction to adapt to different data features by dynamically adjusting the weights, thus improving the overall performance and generalization ability of the model. Therefore, after comprehensively considering various factors, the model finally chooses the attention mechanism as the way of feature fusion.

Model comparison experiments and time consumption

Model comparison experiments

In order to verify the classification performance of the model proposed in this paper, we use Accuracy, Macro-R, and Macro-F1 as evaluation metrics to experimentally compare the Central Asian language sentiment classification model designed in this paper with nine other modeling approaches on the Central Asian language corpus, respectively.

The specific comparison models selected in this article are as follows:

1) SVM (Support Vector Machine): A common supervised learning algorithm that distinguishes different types of data by finding the maximum margin hyperplane in the feature space. It has excellent generalization ability and is particularly suitable for problems with small samples and high-dimensional data. In addition, SVM is relatively simple in model selection and parameter tuning, making it one of the preferred methods for many machine learning tasks.

2) Fast-Text classification model: Facebook open-sourced a fast and efficient text classification model in 2016, which adopts the structure of the Continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW) model and sets the classifier as a three-layer neural network structure. It is composed of an input layer, a hidden layer and an output layer.

3) CNN: This model has been elaborated in detail in the previous text.

4) MC-CNN (Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network): It is mainly used for stereo matching and inspection estimation tasks. It can handle features of different scales simultaneously, improve matching accuracy, and includes several key architectures such as feature extraction networks, matching cost calculation, cost aggregation, and disparity calculation.

5) RCNN (Region-based -Convolutional-Neural Network): Generates a large number of candidate boxes through methods such as selective search, which cover all possible Regions in the image. The algorithm generates a large number of candidate boxes through methods such as selective search. The candidate boxes cover all possible regions in the image, and then the candidate boxes enter the backbone feature extraction network for feature extraction. The extracted feature map is sent to the classifier for object recognition and detection.

6) C-LSTM (Convolutional Long Short-Term memory network): A hybrid deep learning model combining CNN and LSTM, mainly used for processing spatio-temporal data. The core lies in extracting spatial features using CNN and then modeling temporal dependencies through LSTM.

7) MC-CNN-LSTM: A hybrid deep learning model combining MC-CNN and LSTM, with the core lying in extracting spatial features using convolution kernels of different scales, is suitable for image or multi-dimensional spatiotemporal data modeling.

8) BiGRU: This model has been elaborated in detail in the previous text.

9) MC-CNN-BiGRU: A hybrid deep learning architecture combining MC-CNN and BiGRU, specifically designed for processing spatio-temporal sequence data, has higher computational efficiency compared to LSTM.

The comparison results of different models on the Central Asian language corpus are shown in Fig. 8. As can be seen from the figure, the sentiment classification model proposed in this paper achieves better classification results than other models on the Central Asian regional language corpus, and its accuracy, Macro-R, and Macro-F1 reach 92.78%, 91.45%, and 93.54%, respectively, which illustrates the superiority of the model proposed in this paper in Central Asian regional language sentiment classification.

Neural network model-based methods (CNN, RCNN, etc.) are still significantly better than the traditional machine learning modeling method SVM in terms of classification effect, because the SVM model is simply a weighted average of all word vectors in the sentence, and does not take into account the contextual semantics and some deeper information between sentences. So the classification effect is not good, and the accuracy of the neural network model-based method is about 12% higher than that of the SVM based on the traditional machine learning method, which shows that the deep learning method is more effective in the task of linguistic sentiment classification in Central Asia. In addition, the Fast-Text model classification accuracy (83.45%) is better than the SVM model (80.26%), which proves the excellent performance of the Fast-Text model in textual sentiment analysis because of its simple model and fast computing speed. The classification accuracies of CNN and BiGRU are similar in the Central Asian regional language corpus because both of them can extract certain semantic information, but the accuracy of CNN is slightly higher than that of BiGRU, which is due to the fact that the Central Asian regional language corpus is smaller in size and the texts are shorter, and CNN can extract the overall features of the sentence very well, while BiGRU can not give full play to its advantages on the short texts. The comparison experiments of MC-CNN, RCNN, C-LSTM and MC-CNN-LSTM show that the multi-channel model is able to extract richer sentiment feature information compared to the single-channel model, which helps to improve the performance of sentiment classification. By comparing MC-CNN-BiGRU with CNN and BiGRU for comparison, it can be seen that the multi-channel model incorporating CNN and BiGRU is still much better than CNN and BiGRU alone for classification.

The Central Asian language sentiment classification model proposed in this paper can not only extract the local feature information of consecutive words in a sentence, but also capture the sentence context semantic information, which gives full play to the respective advantages of CNN and BiGRU. Moreover, the introduction of the attention mechanism allows the model to pay more attention to the more important sentiment word information in the sentence in the process of feature extraction, and reduces the influence of those words that are not important for classification, so the model proposed in this paper can obtain the best results compared with several other baseline models.

Model time consumption comparison

Based on a model that ensures accuracy, this paper compares the model under the same conditions, i.e., by measuring the time spent on each iteration using an algorithm through a training time experiment comparison method to evaluate model performance. In addition, this paper also selects the IMDb dataset as a comparison object. The IMDb dataset comes from a well-known foreign movie review website and contains reviews of various movies and corresponding sentiment labels.The experimental operating system is Ubuntu 16.04 LTS, and the CPU is Inter® Xeon E3-1231 v3, with the memory of 12G. The TensorFlow was used as the development backend for writing. Figure 9 shows the results of the training time-consuming data comparison of each model.

From the results in the figure, it can be found that the iteration time consumed by the BiGRU method is much higher than that of the CNN group. For the Central Asian regional language corpus dataset produced in this paper, the single rounds of BiGRU and C-LSTM methods consume 286.43 s and 369.52 s, which are 4.2 times and 5.4 times longer than the corresponding CNN methods, respectively. On the IMDb dataset, the training time per round for BiGRU and C-LSTM models are 106.98 s and 138.54 s, which are 2.04 times and 2.65 times of the CNN methods, respectively. The reason for this is that the input data of CNN network is serialized, and the computation of its current state node depends on the output value of the previous moment, so the training time has a very large gap compared to the CNN network that receives parallelized input. From the above experimental data and the corresponding theoretical analysis, the model in this paper adopts the CNN-BiGRU structure, and the CNN method is used to extract different granularity features of the text before the BiGRU modeling, which in turn speeds up the training speed of the model in a way that is supported by theoretical basis and experiments. Overall, the training time of the Central Asian language sentiment classification model designed in this paper is relatively high, but the Central Asian language sentiment classification model combined with the language pre-training BERT model has a better sentiment classification effect when considering the effect of Central Asian language sentiment classification.

The impact of different training time predictions on model results is shown in Table 2 The impact of different training time predictions on model results.

It can be seen that as the training time increases, the model’s accuracy rate rises from 80.2% to 95.9%, and the recall rate increases from78.4% rose to 87.5%, while the F1 value also increased from 79.6% to 87.7%. The accuracy of model classification is also improving as the training time predicts. But when the training time reaches a certain length, the performance of the model reaches the limit.

Conclusion

By combining the BERT pre-trained encoder with a multi-channel convolutional neural network (CNN) and a bidirectional recurrent unit (GRU), followed by the addition of an attention-based feature fusion layer, an emotion classifier suitable for Central Asian languages was constructed. Three empirical results were obtained.

-

(1)

The accuracy reached its peak when the batch size was 512, the maximum sequence length was 160, and the model was trained for 14 epochs.

-

(2)

Among four fusion strategies (concatenation, summation, element-wise multiplication, and attention mechanism), the attention mechanism achieved the highest accuracy, Macro-R value, and Macro-F1 value.

-

(3)

On the Central Asian corpus, the model achieved an accuracy rate of 92.78%, a macro-R of 91.45%, and a macro-F1 of 93.54% in 359.71 s, surpassing existing baselines and providing a practical tool for monitoring sentiment changes in languages along the Belt and Road Initiative.

Future research will focus on three directions: corpora, models, and technology. The Kazakh corpus will be expanded, and Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Uyghur texts will be added to cover the entire Central Asian language family. Domain-specific continuous pre-training, parameter-efficient adapters, and cross-language prompts will be explored to reduce data requirements and enhance zero-shot transferability. Research will be conducted on lightweight transformers (DistilBERT, ALBERT) and edge device quantization techniques to enable real-time inference. Finally, the classifier will be integrated into a streaming analytics platform, combining real-time sentiment monitoring with an explainable AI dashboard to support policymakers and business stakeholders in Xinjiang and surrounding regions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Bilianos, D. & Mikros, G. Sentiment analysis in cross-linguistic context: how can machine translation influence sentiment classification? Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 38 (1), 23–33 (2023).

Abubakar, H. D., Umar, M. & Bakale, M. A. Sentiment classification: review of text vectorization methods: bag of words, Tf-Idf, Word2vec and Doc2vec. SLU J. Sci. Technol. 4 (1), 27–33 (2022).

Brauwers, G. & Frasincar, F. A survey on aspect-based sentiment classification. ACM Comput. Surveys. 55 (4), 1–37 (2022).

Sadr, H. & Nazari Soleimandarabi, M. ACNN-TL: attention-based convolutional neural network coupling with transfer learning and contextualized word representation for enhancing the performance of sentiment classification. J. Supercomputing. 78 (7), 10149–10175 (2022).

Aryal, S. & Prioleau, H. Howard university computer science at semeval-2023 task 12: A 2-step system design for multilingual sentiment classification with language identification. In Proceedings of the 17th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2023) (pp. 2153–2159). (2023).

Kyaw, K. S., Tepsongkroh, P., Thongkamkaew, C. & Sasha, F. Business intelligent framework using sentiment analysis for smart digital marketing in the E-commerce era. Asia Social Issues. 16 (3), e252965–e252965 (2023).

Ma, J., Rong, L., Zhang, Y. & Tiwari, P. Moving from Narrative To Interactive multi-modal Sentiment Analysis: A Survey (ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 2023).

Ghasemi, R., Ashrafi Asli, S. A. & Momtazi, S. Deep Persian sentiment analysis: Cross-lingual training for low-resource languages. J. Inform. Sci. 48 (4), 449–462 (2022).

Yusuf, A., Sarlan, A., Danyaro, K. U., Rahman, A. S. B. & Abdullahi, M. Sentiment Analysis in Low-Resource Settings: A Comprehensive Review of Approaches, Languages, and Data Sources (IEEE Access, 2024).

Kastrati, Z. et al. A deep learning sentiment analyser for social media comments in low-resource languages. Electronics 10 (10), 1133 (2021).

Mennecier, P., Nerbonne, J., Heyer, E. & Manni, F. A central Asian Language survey: collecting data, measuring relatedness and detecting loans. Lang. Dynamics Change. 6 (1), 57–98 (2016).

Khan, I. U. et al. A review of Urdu sentiment analysis with multilingual perspective: A case of Urdu and Roman Urdu Language. Computers 11 (1), 3 (2021).

Mengliev, D. B., Akhmedov, E. Y., Barakhnin, V. B., Hakimov, Z. A. & Alloyorov, O. M. Utilizing lexicographic resources for sentiment classification in Uzbek language. In 2023 IEEE XVI International Scientific and Technical Conference Actual Problems of Electronic Instrument Engineering (APEIE) (pp. 1720–1724). IEEE, 2023).

Altaf, A. et al. Deep learning based cross domain sentiment classification for Urdu Language. IEEE Access. 10, 102135–102147 (2022).

Meetei, L. S., Singh, T. D., Borgohain, S. K. & Bandyopadhyay, S. Low resource Language specific pre-processing and features for sentiment analysis task. Lang. Resour. Evaluation. 55 (4), 947–969 (2021).

Alayba, A. M. & Palade, V. Leveraging Arabic sentiment classification using an enhanced CNN-LSTM approach and effective Arabic text Preparation. J. King Saud University-Computer Inform. Sci. 34 (10), 9710–9722 (2022).

Chennafi, M. E., Bedlaoui, H., Dahou, A. & Al-qaness, M. A. Arabic aspect-based sentiment classification using Seq2Seq dialect normalization and Transformers. Knowledge 2 (3), 388–401 (2022).

Haque, R., Islam, N., Tasneem, M. & Das, A. K. Multi-class sentiment classification on Bengali social media comments using machine learning. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 4, 21–35 (2023).

Tesfagergish, S. G., Damaševičius, R. & Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė, J. Deep learning-based sentiment classification in amharic using multi-lingual datasets. Comput. Sci. Inform. Syst. 20 (4), 1459–1481 (2023).

Lo, S. L., Cambria, E., Chiong, R. & Cornforth, D. Multilingual sentiment analysis: from formal to informal and scarce resource languages. Artif. Intell. Rev. 48, 499–527 (2017).

Dhananjaya, V., Ranathunga, S. & Jayasena, S. Lexicon-based fine-tuning of multilingual language models for low-resource language sentiment analysis (CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology, 2024).

Ali, A., Khan, M., Khan, K., Khan, R. U. & Aloraini, A. Sentiment analysis of low-resource language literature using data processing and deep learning. Computers, Materials & Continua. 79(1), (2024).

Arbane, M., Benlamri, R., Brik, Y. & Alahmar, A. D. Social media-based COVID-19 sentiment classification model using Bi-LSTM. Expert Syst. Appl. 212, 118710 (2023).

Cheruku, R., Hussain, K., Kavati, I., Reddy, A. M. & Reddy, K. S. Sentiment classification with modified RoBERTa and recurrent neural networks. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (10), 29399–29417 (2024).

Ruskanda, F. Z., Abiwardani, M. R., Mulyawan, R., Syafalni, I. & Larasati, H. T. Quantum-enhanced support vector machine for sentiment classification. IEEE Access. 11, 87520–87532 (2023).

Mabokela, K. R., Celik, T. & Raborife, M. Multilingual sentiment analysis for under-resourced languages: a systematic review of the landscape. IEEE Access. 11, 15996–16020 (2022).

Roy, P. K. Deep ensemble network for sentiment analysis in Bi-lingual Low-resource languages. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inform. Process. 23 (1), 1–16 (2024).

Mohammed, I. & Prasad, R. Building lexicon-based sentiment analysis model for low-resource languages. MethodsX 11, 102460 (2023).

Raychawdhary, N., Das, A., Bhattacharya, S., Dozier, G. & Seals, C. D. Optimizing Multilingual Sentiment Analysis in Low-Resource Languages with Adaptive Pretraining and Strategic Language Selection. In 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI) (pp. 1–5). (IEEE, 2024).

Aliyu, Y., Sarlan, A., Danyaro, K. U. & Rahman, A. S. Comparative analysis of transformer models for sentiment analysis in Low-Resource languages. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 15(4), 375–383 (2024).

Kuriyozov, E., Matlatipov, S., Alonso, M. A. & Gómez-Rodríguez, C. Construction and evaluation of sentiment datasets for low-resource languages: The case of Uzbek. In Language and Technology Conference (pp. 232–243). (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Shehu, H. A. et al. Deep sentiment analysis: a case study on stemmed Turkish Twitter data. IEEE Access. 9, 56836–56854 (2021).

Rana, T. A., Shahzadi, K., Rana, T., Arshad, A. & Tubishat, M. An unsupervised approach for sentiment analysis on social media short text classification in Roman Urdu. Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inform. Process. 21 (2), 1–16 (2021).

Awais, D. M. & Shoaib, D. M. Role of discourse information in Urdu sentiment classification: A rule-based method and machine-learning technique. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inform. Process. (TALLIP). 18 (4), 1–37 (2019).

Khan, L., Amjad, A., Ashraf, N., Chang, H. T. & Gelbukh, A. Urdu sentiment analysis with deep learning methods. IEEE access. 9, 97803–97812 (2021).

Khan, L., Amjad, A., Ashraf, N. & Chang, H. T. Multi-class sentiment analysis of Urdu text using multilingual BERT. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 5436 (2022).

Omar, A. & Abd El-Hafeez, T. Quantum computing and machine learning for Arabic Language sentiment classification in social media. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 17305 (2023).

Gablasova, D. et al. Building a corpus of student academic writing in EMI contexts: Challenges in corpus design and data collection across international higher education settings. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 3(1), 45–68 (2024).

Rastogi, N., Verma, P. & Kumar, P. Query expansion based on word embeddings and ontologies for efficient information retrieval. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 12(11), 375–383 (2021).

Tawil, A. A. et al. Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for email phishing detection using TF-IDF, Word2Vec, and BERT. Computers Mater. Continua (2), 3395–3412 (2024).

Wu, D., Wang, Z. & Zhao, W. XLNet-CNN-GRU dual-channel aspect-level review text sentiment classification method. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83(2), 5871–5892 (2024).

Liu, Y., Wang, S. & Yu, S. A bullet screen sentiment analysis method that integrates the sentiment lexicon with RoBERTa-CNN. Electronics 13(20), 3984 (2024).

Bhart, G., Prakasam, P. & Velmurugan, T. Integrated BERT embeddings, BiLSTM-BiGRU and 1-D CNN model for binary sentiment classification analysis of movie reviews. Multimedia Tools Appl. 81(23), 33067–33086 (2022).

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my esteemed mentor, Professor Wushouer Silamu, for their invaluable guidance and support throughout the course of this research. Professor [Mentor’s Name]’s expertise and wisdom have been a beacon, illuminating the path through the complex landscape of Multilingual information processing.Their unwavering commitment to academic excellence has not only shaped the quality of this work but has also been instrumental in my personal and professional development. The insights and constructive criticism provided by Professor [Mentor’s Name] have been pivotal in refining my research methodology and in sculpting the final manuscript.I am particularly indebted to Professor Wushouer Silamu for their patience in discussing my ideas, for their encouragement during the challenging moments, and for their inspiration that has driven me to push the boundaries of my intellectual capabilities. Their dedication to fostering a stimulating and collaborative research environment has been a cornerstone of my academic journey.Moreover, I am grateful for the opportunities Professor [Mentor’s Name] has provided to engage with a diverse array of scholarly resources and to participate in academic conferences, which have enriched my understanding and expanded my network within the academic community.Finally, I would like to acknowledge the broader team at Xinjiang University, whose collaborative spirit and shared passion for discovery have contributed to a vibrant and nurturing research atmosphere. To Professor Wushouer Silamu and all those who have supported me, I offer my heartfelt thanks.Data Availability:Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Palidan Muhetaer Ph.D., Associate Professor 1. Conceived and designed the entire research project. 2. Led the development of a novel sentiment classification method utilizing language models.3. Provided linguistic expertise on the Central Asian news experimental corpus and its unique characteristics. 4. Oversaw the experimental design and data analysis processes. 5. Participated in drafting and revising the manuscript, with a focus on the methodology and results Sect. 6. Ensured the integrity of the research and supervised the final submission process.Guo Wenqiang Ph.D., Professor 1. Managed the data collection and preprocessing for sentiment analysis in Central Asian languages. 2. Researched and fine-tuned algorithms based on language models. 3. Executed computational experiments and prepared the initial draft of the results Sect. 4. Assisted in interpreting the research findings and their implications for the field of computational linguistics.5. Participated in the revision of the manuscript based on feedback from internal and external peers.Lu Chong Ph.D., Professor 1. Analyzed Central Asian languages and their unique characteristics.2. Provided consultation on adapting the sentiment classification method to accommodate linguistic nuances. 3. Analyzed the linguistic aspects of the data and participated in discussions of the results. 4. Participated in drafting sections concerning linguistic considerations and their impact on sentiment analysis. 5. Reviewed the manuscript for linguistic accuracy and provided critical feedback for improvement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhetaer, P., Wenqiang, G. & Chong, L. A Language model-based approach to sentiment classification of languages in central Asia. Sci Rep 15, 38392 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22198-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22198-6