Abstract

This study investigates the biogeographic barriers and environmental gradients that influence the distribution and niche segregation of seven Hynobius salamander species in South Korea. Using Ecological Niche Models (ENMs) developed with the Maxent software and 48 environmental variables, we conducted four niche overlap tests for each species pair: niche identity tests and background similarity tests to assess niche differentiation, lineage-breaking tests to evaluate species boundaries in relation to environmental shifts, and ribbon tests to determine whether unsuitable habitats serve as distributional barriers. The results indicated that significant biogeographic barriers, including both physical features such as rivers and mountains and environmental gradients, influence the range segregation of these salamanders. The study also identified distinct ecological niches among the species, with environmental gradients and unsuitable habitats acting as key factors shaping their distributions. These findings highlight the crucial role of biogeographic barriers in the distribution and speciation of Hynobius salamanders, emphasizing the need to consider these factors in conservation strategies aimed at preserving their ecological diversity and evolutionary trajectories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Elucidating biogeographic barriers between closely related species is critical for refining our comprehension of species distribution patterns1,2. Specifically, biogeographic barriers are shaped by a combination of abiotic and biotic factors such as dispersal capacity, interspecific competition, biological factors, temperature, precipitation, and climate3,4,5,6,7, often confining species’ dispersal and gene flow, which play a critical role in determining species distributions and promoting divergence and speciation8. For instance, two subspecies of smooth newt, Lissotriton vulgaris kosswigi, restricted to the southern Black Sea coast, and Lissotriton vulgaris vulgaris, with a broader European range, exhibit significant genetic differentiation due to barriers restricting gene flow between them, as evidenced by variation within eight nuclear and mitochondrial DNA gene fragments across multiple populations9. Similarly, climate change can act as a biogeographic barrier, influencing the distribution of species like the terrestrial slug Deroceras panormitanum10.

Due to the specific habitat requirements of many amphibian species during their adult life11,12, and the resulting limited mobility12, amphibians are suitable models for testing biogeographic barriers13,14. For instance, the closely distributed congeneric giant tree frogs (genus Leptopelis) in west and central Africa are segregated by both a riverine barrier and an environmental gradient15. To assess these barriers, an analysis of genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism data demonstrated that species-level divergence coincides with a prehistoric event. Furthermore, applying ecological niche modeling provided additional evidence highlighting the distinct environmental niches occupied by each of the three species of the giant tree frog15.

Ecological Niche Models (ENMs) integrate environmental and occurrence data to define a taxon’s environmental preferences and suitability16. In addition, ENMs can be used with occurrence data to identify the impact of ecological variables on the boundaries of species’ distribution and possible biogeographic barriers17,18. For instance, it is a challenge to understand the distributions of marine species, as there are often no physical barriers delineating these species8,19, and while ocean currents generally promote dispersal and connectivity among marine populations, they can also act as abrupt environmental gradients20. Besides marine ecology, distinct refugia of tailed frog populations of Ascaphus montanus in the Rocky Mountains were confirmed by combining ecological modeling and a nested clade analysis21.

Together with niche overlap tests, ENMs serve as valuable tools for examining ecological distinctions among taxa and assessing the influence of ecological factors on range boundaries, especially on broad geographic scales22. ENMs, used with occurrence data, identified that the climatic factors such as the minimum temperature of the coldest month were the ecological determinants delineating the parapatric range boundaries of these two closely related species2.

The Hynobiidae family is a diverse and ancient lineage of East Asian salamanders, comprising two main lineages distributed across the Eastern Palearctic: Onychodactylus, and Salamandrella together with Hynobius (Hynobiinae). Limited dispersal ability, likely linked to climatic variations over geological times, has fragmented the distribution of the Hynobiidae family across Eastern Asia23,24. Several factors have shaped the distribution of these salamanders, including the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and climatic changes associated with the establishment of the monsoon system24,25. Differentiating Hynobius species based solely on morphological characteristics can be challenging26, making it essential to understand the ecological factors influencing their distribution for accurately defining species identities and boundaries23,24,25,26,27,28. Although these insights have aided in developing salamander conservation strategies, our understanding of specific speciation events and biogeographic boundaries remains limited. This highlights the significance of studying Hynobius salamanders in South Korea, where diverse species and distinct range boundaries provide an ideal system for investigating speciation mechanisms and their implications for conservation.

This study employed ecological niche modeling (ENM) methods based on the framework proposed by Glor&Warren29 to evaluate niche overlap between congeneric Hynobius salamander pairs and identify potential biogeographic barriers associated with their sympatric ranges. We answered these questions through four hypotheses: (1) Whether Hynobius species have identical niche; (2) Whether they exhibit background similarity; (3) Whether these species encounter biogeographic barriers linked to abrupt environmental changes or steep environmental gradients; (4) Whether biogeographic boundaries are associated with regions of notably unsuitable habitat that separate two or more suitable regions. We first assessed the niche identity and background similarity for the seven Hynobius species pairs in South Korea. Next, we investigated the presence of potential biogeographic barriers for the same species pairs by conducting lineage-breaking tests and unsuitable ribbon tests. Our findings are suitable as a model for determining species boundaries, given the ongoing debate and lack of consensus on a universal definition of species.

Materials and methods

Species data and environmental niche modeling

Within the family Hynobiidae, Hynobius stands as the most species-rich genus, encompassing over 60 recognized species30,31. In South Korea, seven Hynobius species have been identified: H. leechii, H. unisacculus, H. notialis, H. perplicatus, H. quelpaertensis, H. yangi, and H. geojeensis. Except for H. leechii, which boasts a wide distribution across the Korean peninsula and extends into China, the remaining six species are primarily concentrated in the southern region of the Korean peninsula26. A diagonal along the hills and mountains in the southern region of the Korean peninsula, starting west of Iksan and extending to Ulsan, serves as a habitat and contact zone for H. leechii and other Hynobius species32,33. In addition to H. leechii, this diagonal, from west to east, also includes H. quelpaertensis, followed by H. unisacculus, H. perplicatus, H. notialis, and H. yangi. Finally, H. perplicatus overlaps with H. notialis in its range’s northern part and H. geojeensis on the southern edge, from which the latter species distributes further south (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic and phylogeographic studies show that H. unisacculus is deeply divergent from H. leechii, H. yangi, and H. quelpaertensis, with genetic distances near 10% across COI and cyt b34,35. In the case of H. quelpaertensis, the species shows a structure segregating Jeju and the mainland population36,37, and H. perplicatus is deeply divergent despite its interesting geographic location among the other clades38,39. Broader East Asian analyses have outlined several clades within the Hynobius genus, with all South Korean species clustered within the same one. We use these phylogenetic hypotheses solely as context for our overlap comparisons26,35.

Distribution of seven Hynobius species across the Korean peninsula, based on the occurrence data used for analysis. Each color corresponds to a species. The map was generated using ArcGIS Pro software (version 3.3, https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/3.3/get-started/release-notes.htm).

We relied on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database (GBIF, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.trnntk3, accessed 24 January 2023) to retrieve occurrence data for all Hynobius species across the Korean peninsula (see Supplementary Data S1 online). Following the literature26, the range of presence was delineated, and false localities due to geocoding errors and duplicates were discarded, resulting in 5,547 occurrence points. The number of occurrence points available for each species (minimum n = 33) exceeded the number of points typically considered sufficient for accurate ecological niche modeling40 (n > 18).

In this study, we initially tested 48 variables for potential inclusion in Ecological Niche Modeling (ENM). We combined the bioclimatic variables to define the fundamental niche and the recent anthropogenic variables to define the realized niche41. The latter captures pressures such as habitat fragmentation that prevent occupancy of climatically suitable areas42. This approach improves model performance in human-impacted landscapes and provides a more realistic evaluation of current niche configuration26,43,44.

We downloaded environmental layers at a spatial resolution of 30-arc-second (~ 1 km) resolution. The dataset included 19 bioclimatic variables, solar radiation, elevation, terrain derivatives from elevation, landscape variables, and anthropogenic layers such as distance to urban areas and distance to river. Bioclimatic variables and solar radiation data came from the Worldclim dataset (v. 2.0, www.worldclim.org). Elevation and terrain derivatives were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/). Landscape variables were extracted from World Land Cover 30 m BaseVue 2013 (https://landscape6.arcgis.com/arcgis/rest/services/World_Forests_30m_BaseVue_2013/ImageServer). https://landscape6.arcgis.com/arcgis/rest/services/World_Forests_30m_BaseVue_2013/ImageServer). For anthropogenic layers, we derived the distance by binarizing land cover and river raster (urban or river = 1, other = NoData), projecting to an equal-area coordinate system, computing Euclidean distance to the nearest target pixel and resampling the distance raster to the environmental grid. To reduce multicollinearity, we computed pairwise Pearson correlations and retained only variable with r < 0.845. For highly correlated pairs with r ≥ 0.8,, we retained the variable with a higher percentage of contribution in an initial full MaxEnt run across Hynobius species and removed the other45. Variable selection was guided by prior studies46,47,48,49 and by the known behavioral and ecological traits of Hynobius24. The final model used 15 variables including bioclimatic, landscape, and vegetation (Table 1).

To develop the ecological niche models, we utilized the MaxEnt v. 3.4.3 software (available at http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/, accessed on January 24, 2022). We constructed these models using occurrence records and environmental data with default settings50. This approach enabled us to assess the influence of individual bioclimatic variables on predictions as represented by the response curves. We evaluated the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) metric and true skill statistic (TSS) to assess the performance of each model51,52,53. An AUC value greater than 0.5 indicates that the model outperforms a null model51,52. MaxEnt output raster files were classified into suitable and unsuitable habitats using the maximum training sensitivity plus specificity (MTSS) threshold, which is insensitive to pseudo-absences54.

Testing whether species’ pairs have different niches

To test for differing niche requirements between species pairs, we utilized niche identity tests, which compare ENM predictions of habitat suitability for each grid cell in the study area. Ecological niche differentiation can be assessed using ENMs, niche identity tests, and background similarity tests. We used I and Schoener’s D metrics to measure niche overlaps, which range from (no overlap) to 1 (complete overlap) summarizing the amount of niche differentiation. Randomization tests comparing ENMs of paired species are employed to determine the degree of niche overlap between species, as outlined by Glor & Warren (2011) and Warren et al. (2008).

Testing whether species’ pairs have background similarity

The niche identity test assesses whether the niches of two species are equivalent to each other, and the background similarity test assesses whether the niches of two species are more similar than expected by chance, based on their environmental backgrounds. The identity test analyzes whether the ENMs generated for two species differ from ENMs calculated from pairs of samples drawn at random from a pooled dataset of the two species’ occurrence points. For the background similarity test, we compared models created using occurrence points of one species with models created using randomly placed points from the geographic range of the other species in the pairs. The observed niche overlap was then compared to the null distributions generated by the randomization tests. The test was run with 100 randomized pseudo-replicates using the R package ‘enmtools’55 (http://enmtools.blogspot.com.tr). If there were no significant difference between the ENMs and the randomized pseudo-replicates of each Hynobius pair, the pair was considered effectively identical in terms of niche.

Testing whether there is a sharp environmental transition or a significant environmental gradient between species pairs

We employed lineage-breaking tests to investigate whether species’ range boundaries coincided with sharp environmental transitions29. We generated null distributions for similarity metrics I and Schoener’s D by performing 100 random replicates. In the linear test, we pooled occurrences from both species and established a randomized dividing line within their shared range. The dividing line was positioned to ensure that the numbers of occurrences on either side of the line matched the numbers of respective occurrences for both species. We then generated ENMs for each side of the line. The null hypothesis (i.e., a sharp environmental gradient is not separating the two species) was rejected if observed I or Schoener’s D values were statistically significant in the one-tailed t-test against the null distribution. Observed values significantly lower than the null distribution allowed us to reject the null hypothesis. In each pseudo replicate, a line separating the ranges of the two populations was randomly placed and adjusted until the number of individuals in each population matched the observed sample sizes for each species. If a starting angle failed to create appropriate partitions, it was replaced with another line. This method prevented bias in I and Schoener’s D values due to sample size differences between pseudo-replicates. Duplicate partitions were excluded from the analysis.

Testing whether there is an unsuitable habitat between the species’ pair

To assess whether the contact zones between the two species are separated by unsuitable habitats, we conducted the “ribbon” test29. Initially, a single ecological niche model was created using the pooled occurrence data of the two species along the ribbon. Then, a ribbon was created as a polygon between the two species ranges. This ribbon was populated with random points of the same number of the pooled species’ occurrences. These random points were then used to create an ENM which was then tested against the pooled ENM for I and D. After the assessment of this overlap, we performed 100 replicates, each featuring a randomly generated ribbon within the combined occurrences of both species, with the same area as the original ribbon. By calculating I and D values from these pseudo-replicates, we generated a null distribution to determine whether the pooled niche for both species was more like the actual contact zone ribbon than a randomized ribbon.

Result

Habitat suitability model for hynobius species

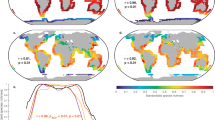

The final performance of the ENMs for each species, based on the provided occurrence data, was highly satisfactory. In all cases, the models achieved or surpassed the established AUC and TSS standard. The AUC and TSS values for each species were as follows: H. leechii (AUC = 0.742 ± 0.002 and TSS = 0.428 ± 0.0188), H. unisacculus (AUC = 0.990 ± 0.006 and TSS = 0.818 ± 0.1346), H. notialis (AUC = 0.978 ± 0.002 and TSS = 0.845 ± 0.0613), H. perplicatus (AUC = 0.989 ± 0.006 and TSS = 0.625 ± 0.4145), H. quelpaertensis (AUC = 0.942 ± 0.002 and TSS = 0.822 ± 0.0223), H. yangi (AUC = 0.989 ± 0.001 and TSS = 0.428 ± 0.0188), and H. geojeensis (AUC = 0.999 ± 0.001 and TSS = 0.799 ± 0.1117). The habitat suitability results were thresholded using the maximum training sensitivity plus specificity (MTSS) value to classify MaxEnt output raster files into suitable and unsuitable habitats (Fig. 2). We found that the variables with the highest contribution to the model differed among Hynobius species: human distance for H. leechii, annual precipitation (bio12) for H. unisacculus, December solar radiation (srad12) for H. notialis and H. perplicatus, August solar radiation (srad08) for H. quelpaertensis, temperature seasonality (bio4) for H. yangi, and river distance for H. geojeensis (Table 2).

MaxEnt habitat suitability models for seven Hynobius species. (a) H. leechii, (b) H. unisacculus, (c) H. notialis, (d) H. perplicatus, (e) H. quelpaertensis, (f) H. geojeensis, (g) H. yangi. Panel (h) shows predicted habitat suitability for all seven species across South Korea. In (h), areas above the MTSS threshold appear as colored regions. Each color indicates a different species, and all panels are labeled with species names. The map was generated using ArcGIS Pro software (version 3.3, https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/3.3/get-started/release-notes.htm).

Niche identity test and background similarity test

The ecological niche differentiation test revealed that the predicted niches for the 21 Hynobius species pairs were not identical (Supplementary Table S1). However, the background similarity test indicated that the ENM projections from every species pair were not identical and differed by pairs. For example, of the 21 pairs, H. leechii vs. H. perplicatus showed significant overlap (I = 0.9067 and Schoener’s D = 0.6702, both p < 0.05). In contrast, H. notialis vs. H. unisacculus was not significantly different (I = 0.9600 and Schoener’s D = 0.8010, both p > 0.05), so we did not reject the null hypothesis. Furthermore, H. yangi versus H. geojeensis, and H. unisacculus versus H. perplicatus pairs significantly differed in only one direction. For example, H. yangi and H. geojeensis were not more similar than expected by chance (I = 0.0997 and Schoener’s D = 0.022, p < 0.05/H. yangi vs. H. geojeensis background, I = 0.1252 and Schoener’s D = 0.03, p > 0.05/H. geojeensis vs. H. yangi background; Supplementary Table S2). These tests revealed distinct ecological niches among Hynobius salamander species, rejecting the null hypothesis stating that Hynobius pairs have identical niches. For some species pairs, we could reject the null hypothesis stating that species are more similar than expected by chance and have distinct biogeographic ranges (Fig. 3).

Summarized map for four hypotheses testing biogeographic barriers on seven Hynobius species. Each line and polygons represent each hypothesis. The total biogeographic barrier is shown in dot lines, and the linear barriers are shown in straight line. The approximate barriers on the map are based on occurrence points used for modelling (grey polygon). The map was generated using ArcGIS Pro software (version 3.3, https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/3.3/get-started/release-notes.htm).

Lineage-breaking test

Testing for the presence of an abrupt environmental transition or steep environmental gradient through the lineage-breaking test showed that the environmental divergence between most of the pairs was greater than that observed between pseudoreplicated null distribution generated randomly. From the 21 pairs, we did not reject the null hypothesis for three pairs: H. leechii versus H. notialis, H. leechii versus H. perplicatus, and H. notialis versus H. perplicatus (Supplementary Table S3). For example, between H. leechii versus H. notialis, there is no significant environmental gradient between the two species since the I and D values are not significantly different (I = 0.5216 and Schoener’s D = 0.2307, both p > 0.05). Overall, the lineage-breaking tests revealed a significant environmental divergence between most Hynobius species, supporting the existence of abrupt environmental transitions or steep environmental gradients that have contributed to their diversification (Fig. 3).

Ribbon test

The tests for the unsuitable habitat between two suitable regions through the ribbon test also differed by species pair. The null hypothesis was rejected if the flanking regions of the ribbon were significantly different from one another than expected by chance as indicated by the ribbon tests for these populations. From the 21 pairs, we did not reject the null hypothesis for two pairs: H. notialis versus H. geojeensis, and H. leechii versus H. perplicatus (Supplementary Table S4). For example, between H. leechii versus H. perplicatus, there was no perceived barrier between the two species since the I and D values are not significantly different (I = 0.6542 and Schoener’s D = 0.3309, both p > 0.05 for H. leechii sampling vs. ribbon/I = 0.8243 and Schoener’s D = 0.5499, both p > 0.05 for H. perplicatus sampling vs. ribbon). As such, the ribbon tests revealed unsuitable habitats between most pairs of Hynobius species (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our approach successfully investigated four key hypotheses: (i) Hynobius species have distinguish niches. (ii) These species have different biogeographical backgrounds. (iii) Biogeographic barriers linked to abrupt environmental changes or steep gradients are present between species. (ⅳ) These biogeographic boundaries coincide with regions of notably unsuitable habitat, effectively separating suitable regions for different Hynobius species. Applying a biogeographic barrier framework to the seven Hynobius species, we provide evidence supporting the presence of significant environmental biogeographic barriers to dispersal. These barriers come in the form of physical barriers and environmental gradients across the southern part of the South Korea, which are particularly unsuitable between some species pairs.

In this study, some species pairs, including H. leechii, H. yangi, H. notialis, H. perplicatus and H. unisacculus, were significantly segregated by existing physical barriers. The pairs H. leechii and H. yangi, and H. notialis and H. perplicatus, were separated by the Nakdong River, which has an average width of 500–600 m in both its upstream and downstream Sect56. The species pair H. unisacculus and H. notialis were separated by the Seomjin River, with an average width of up to 700 meters57. This segregation is similar to the one delineating the distribution of a Korean treefrog, D. flaviventris, by the Mangyeong River58, despite an average width of only 300 meters59. As another example, major rivers in North Dakota act as barriers, shaping the regional population of the northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens)60. Such geographic segregations are also common among salamander species, for instance, moderate levels of genetic differentiation are observed between individuals of the salamander Plethodon cinereus located on opposite sides of small streams (width ≤ 7 m)61.

Mountains, along with rivers and oceans, also serve as common barriers to the dispersal of species due to elevation and slope62,63,64. The Jiri Mountain range, with a peak of 1,696 m, separates H. leechii (mean elevation of 360 m) and H. unisacculus (mean elevation of 550 m)65,66. The Andes Mountain ranges, ranking as the second highest after the Himalayas and towering nearly 7000 m, have fostered lineage diversification67. They have also served as a conduit for species dispersal into adjacent biomes, a phenomenon supported by studies on lizards, emphasizing the role of Andean uplift in bolstering species diversity through allopatric fragmentation68. Not only do high-elevation mountains play a role, but lowland areas also contain isolated mountains with lower elevations, such as Bailing mountains, which have a peak of 546 m. These mountains, separated by deep valleys, can inhibit dispersal, and promote fragmentation, especially for taxa with limited dispersal abilities, like stream salamanders (Hynobiidae: Batrachuperus)69.

Interpreting the results of the applied framework revealed that the presence of a biogeographic barrier either corresponds to a current physical barrier or historical events70,71. Many studies support riverine barriers as significant limits to amphibians’ dispersal ability and barriers to gene flow60,72. For instance, the Amazon River separates the biogeographical regions in the north from those in the south, while the Madeira River divides the southeastern regions from the southwest, acting as strong barriers that impact the speciation of anuran species in these areas73. Similarly, the well-known ring species of salamanders, the Ensatina eschscholtzii complex, originated in northern California or southern Oregon and expanded southward along two paths: the coast ranges and the Sierra Nevada. Due to geographic variation acting as a barrier, these paths led to speciation, with the lineages reconnecting in southern California to form a ring around the Central Valley74.

While some species pairs may be separated by physical barriers, others may be the result of historical events or abiotic factors that have influenced their distributions2,75. Competition for resources like basking sites, nesting areas, and refuges can limit the range of a species, particularly for amphibians and reptiles2. In the case of Hynobius salamanders, their similar breeding behaviors can have led to intense competition upon contact, resulting in the formation of niche partitions and biogeographic barriers24. Research on the agile frog (Rana dalmatina) in its refugial range in the Italian Peninsula highlights greater diversity and phylogeographic structure compared to the rest of the species’ range in Europe76. Similarly, the Korean peninsula’s mountainous terrain and lack of glaciation during the Quaternary provided refuges for salamanders during periods of climatic upheaval, contributing to the peninsula’s high salamander diversity and endemism77. These studies suggest that climate-driven microevolutionary processes during glacial and interglacial periods have significantly contributed to genetic diversity in these regions76,78. Consequently, these historical events likely led to increased population densities in the Korean peninsula’s southern region, shaping salamanders’ current distribution and establishing biogeographic barriers.

Unlike the delineated distributions of other salamander species, Hynobius leechii is widely spread across the peninsula26. This can be because H. leechii dispersed before encountering the highest mountain barrier of the peninsula, Baekdudaegan, thus avoiding its effects79. Alternatively, H. leechii may exhibit greater genetic divergence among populations separated by Baekdudaegan26,34. For instance, the lizard Gonatodes humeralis and the tree frog Dendropsophus leucophyllatus, distributed across South America, show significant genetic differentiation associated with all Amazonian rivers80. Our tests highlight two informative contrasts within the same analytical framework. For H. leechii and H. perplicatus, the identity test indicated a difference, with I equal to 0.9067 and Schoener’s D equal to 0.6702 and both p values less than 0.05, yet the background, lineage break, and ribbon tests did not indicate strong environmental barriers between their distributions. These outcomes point to broadly similar environmental conditions and an absence of a pronounced contemporary barrier. The pair diverged about 5.3 million years ago34, and phylogenetic evidence indicates they are distinct lineages within the South Korean assemblage26,34,35,36,39. This combination suggests that species limits are maintained by processes such as reproductive isolation and ecological interactions. Similar dynamics are reported for large terrestrial salamanders, and for instance, interspecific competition in Plethodon glutinosus and P. jordani system appears to drive isolation more strongly than differences in altitude preferences81. Closely related species that occur in sympatry can also show reproductive isolation, leading to genetic divergence and even sympatric speciation, as documented in multiple groups including plants and insects82,83. In contrast, H. notialis and H. unisacculus showed high overlap with an identity outcome that was not significant, with I equal to 0.9600 and Schoener’s D equal to 0.8010 and both p values greater than 0.05, which aligns with niche conservatism among closely related or recently separated lineages84. A third pattern involves barrier-positive separations that coincide with spatial heterogeneity, for example H. yangi and H. quelpaertensis are separated by a corridor of low suitability, which is consistent with niche evolution in heterogeneous environments where divergence develops within varying conditions rather than across climatic dissimilarity85. Differences in microhabitat use along streams, breeding timing, and short-distance movements offer plausible mechanisms for these outcomes, and studies in frogs show that behavior can buffer environmental constraints in ways that shape contact and overlap86.

Conclusion

This study employed the framework developed by Warren et al. (2008) and Glor & Warren (2011) to elucidate the biogeographic barriers separating the seven Korean Hynobius salamander species. In contrast to previous studies that focused on only two congeneric species of Anolis lizards across the Hispaniola plain, our investigation encompassed seven closely distributed species and integrated both frameworks into four hypotheses tested using R studio software. Specifically, the comparative framework employed in this study corroborates the underlying mechanisms of speciation and evolution in the seven Hynobius salamanders by supporting the distinct distribution patterns arising from dispersal barriers identified in our results. Our findings contribute to the overall understanding of the large-scale drivers influencing species’ distribution patterns and evolution, enabling us to predict how environmental changes may affect distribution and conservation needs.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Pappalardo, P., Pringle, J. M., Wares, J. P. & Byers, J. E. The location, strength, and mechanisms behind marine biogeographic boundaries of the East Coast of North America. Ecography 38, 722–731 (2015).

Hu, J. & Jiang, J. Inferring ecological explanations for biogeographic boundaries of parapatric Asian mountain frogs. BMC Ecol. 18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0160-5 (2018).

Brown, J. H. On the relationship between abundance and distribution of species. Am. Nat. 124, 255–279 (1984).

Schluter, D. & Pennell, M. W. Speciation gradients and the distribution of biodiversity. Nature 546, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22897 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Influence of Climatic and geographic factors on the Spatial distribution of Qinghai Spruce forests in the dryland Qilian mountains of Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 612, 1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.180 (2018).

Devlin, J. J. et al. Simulated winter warming negatively impacts survival of Antarctica’s only endemic insect. 36, 1949–1960, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14089

Di Gregorio, C., Iannella, M. & Biondi, M. Revealing the role of past and current climate in shaping the distribution of two parapatric European bats, myotis daubentonii and M. capaccinii. Eur. Zoological J. 88, 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2021.1918275 (2021).

Haye, P. A. et al. Genetic and morphological divergence at a biogeographic break in the beach-dwelling brooder excirolana hirsuticauda menzies (Crustacea, Peracarida). BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1442-z (2019).

Nadachowska, K. & Babik, W. Divergence in the face of gene flow: the case of two newts (Amphibia: Salamandridae). Molecular Biology and Evolution 26, 829–841, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msp004%J Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Lee, J. E., Janion, C., Marais, E., van Jansen, B. & Chown, S. L. Physiological tolerances account for range limits and abundance structure in an invasive slug. Proceedings. Biological sciences 276, 1459–1468, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.1240

Semlitsch, R. D. & Bodie, J. R. Biological criteria for buffer zones around wetlands and riparian habitats for amphibians and reptiles. 17, 1219–1228, (2003). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02177.x

Alex Smith, M. & Green, M. D. Dispersal and the metapopulation paradigm in amphibian ecology and conservation: are all amphibian populations metapopulations? Ecography 28, 110–128 (2005).

Zeisset, I. & Beebee, T. J. C. Amphibian phylogeography: a model for Understanding historical aspects of species distributions. Heredity 101, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2008.30 (2008).

Penner, J. et al. A hotspot revisited: a biogeographical analysis of West African amphibians. Divers. Distrib. 17 (6), 1077–1088 (2011).

Jaynes, K. E. et al. Giant Tree Frog diversification in West and Central Africa: Isolation by physical barriers, climate, and reproductive traits. Mol. Ecol. 31 (15), 3979–3998 (2022).

Peterson, A. T. J. T. c. Predicting species’ geographic distributions based on ecological niche modeling. 103, 599–605 (2001).

Graham, C. H. et al. Integrating phylogenetics and environmental niche models to explore speciation mechanisms in dendrobatid frogs. Evolution 58 (8), 1781–1793 (2004).

Gür, H. J. Z. i. t. M. E. The Anatolian diagonal revisited: Testing the ecological basis of a biogeographic boundary. 62, 189–199 (2016).

Ameri, S., Pappurajam, L., Labeeb, K., Lakshmanan, R. & Ayyathurai, K. P. The role of the Sunda shelf biogeographic barrier in the cryptic differentiation of Conus litteratus (Gastropoda: Conidae) across the Indo-Pacific region. PeerJ 11, e15534 (2023).

Wares, J. P., Gaines, S. & Cunningham, C. W. A comparative study of asymmetric migration events across a marine biogeographic boundary. J. E. 55, 295–306 (2001).

Carstens, B. C. & Richards, C. L. Integrating coalescent and ecological niche modeling in comparative phylogeography. J. E. 61, 1439–1454 (2007).

Broennimann, O. et al. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 21 (4), 481–497 (2012).

Zhang, P. et al. Phylogeny, evolution, and biogeography of Asiatic Salamanders (Hynobiidae). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 (19), 7360–7365 (2006).

Borzée, A. J. B. E. & Conservation. Academic Press, E. Continental Northeast Asian Amphibians: Origins. (2024).

Lee, P. F., Lue, K. Y. & Wu, S. H. Predictive distribution of hynobiid salamanders in Taiwan. J. Z. S. 45, 244–254 (2006).

Borzée, A. & Min, M. S. J. A. Disentangling the impacts of speciation, sympatry and the island effect on the morphology of seven Hynobius sp. salamanders. 11, 187 (2021).

Matsui, M. et al. Invalid specific status of hynobius Sadoensis sato: electrophoretic evidence (Amphibia: Caudata). J. Herpetol. 308–315 (1992).

Peng, Y. et al. Estimation of habitat suitability and landscape connectivity for Liaoning and Jilin clawed salamanders (Hynobiidae: Onychodactylus) in the transboundary region between the people’s Republic of China and the Democratic people’s Republic of Korea. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 48, e02694 (2023).

Glor, R. E. & Warren, D. J. E. Testing ecological explanations for biogeographic boundaries. Evolution 65 (3), 673–683 (2011).

Sakai, Y. et al. Discovery of an unrecorded population of Yamato salamander (Hynobius vandenburghi) by GIS and eDNA analysis. Environ. DNA 1 (3), 281–289 (2019).

Frost, D. R. J. h. r. a. o. v. h. a. Amphibian species of the world: an online reference. Version 5.4. (2010).

Kim, L., Han, G. J. S. & Publisher, T. Chosun animal encyclopedia, herpetology volume. (2009).

Chang, M. H., Koo, K. S. & Song, J. Y. The list of amphibian species in 66 Islands in Korea. J. K J. O H. 3, 19–24 (2011).

Baek, H. J. et al. Mitochondrial DNA data unveil highly divergent populations within the genus hynobius (Caudata: Hynobiidae) in South Korea. Mol. Cell. 31(2), 105–112 (2011).

Moon, J. I. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of the small salamander in korea, hynobius unisacculus (Anura: Hynobiidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5(1), 530–531 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. An isolated and deeply divergent hynobius species from Fujian. China 13, 1661 (2023).

Suk, H. Y. et al. Genetic and phylogenetic structure of hynobius quelpaertensis, an endangered endemic salamander species on the Korean Peninsula. Genes Genom. 42 (2), 165–178 (2020).

Li, J., Fu, C., & Lei, G. Biogeographical consequences of cenozoic tectonic events within East Asian margins: a case study of hynobius biogeography. PloS one 6 (6), e21506 (2011).

Min, M. S., Baek, H., Song, J. Y., Chang, M. & Poyarkov, N. Jr A new species of salamander of the genus hynobius (Amphibia, Caudata, Hynobiidae) from South Korea. J. Z. 4169, 475–503 (2016).

Mateo, R. G., Felicísimo, Á. M. & Muñoz, J. Effects of the number of presences on reliability and stability of MARS species distribution models: the importance of regional niche variation and ecological heterogeneity. J. Veg. Sci. 21 (5), 908–922 (2010).

Guisan, A. & Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol. Lett. 8 (9), 993–1009 (2005).

Pearson, R. G., et al. Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: a test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J. Bogeogr. 34 (1), 102–117 (2007).

Niwa, K., Van Tran, D. & Nishikawa, K. J. P. Differentiated historical demography and ecological niche forming present distribution and genetic structure in coexisting two salamanders (Amphibia, Urodela, Hynobiidae) in a small Island. Japan 10, e13202 (2022).

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E. & Turelli, M. Environmental niche equivalency versus conservatism: quantitative approaches to niche evolution. Evolution 62 (11), 2868–2883 (2008).

Bradie, J. & Leung, B. A quantitative synthesis of the importance of variables used in maxent species distribution models. J. Biogeogr. 44 (6), 1344–1361 (2017).

Blank, L. & Blaustein, L. Using ecological niche modeling to predict the distributions of two endangered amphibian species in aquatic breeding sites. Hydrobiologia 693 (1), 157–167 (2012).

Hocking, D. J. et al. Effects of experimental forest management on a terrestrial, woodland salamander in Missouri. Forest Ecol. Manage. 287, 32–39 (2013).

O’Donnell Katherine, M. Predicting Variation in Microhabitat Utilization of Terrestrial Salamanders. (2014).

Seaborn, T., Goldberg, C. S. & Crespi, E. J. A. Drivers of distributions and niches of North American cold-adapted amphibians: evaluating both climate and land use. Ecol. Appl. 31 (2), e2236 (2021).

Phillips, S. J. & Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31 (2), 161–175 (2008).

Fielding, A. H. & Bell, J. F. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environ. Conser. 24 (1), 38–49 (1997).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 1223–1232 (2006).

Somodi, I., Lepesi, N. & Botta-Dukát, Z. J. E. & evolution. Prevalence dependence in model goodness measures with special emphasis on true skill statistics. 7, 863–872 (2017).

Liu, C., White, M. & Newell, G. J. Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J. O B. 40, 778–789 (2013).

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E. & Turelli, M. ENMTools: a toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography 33 (3), 607–611 (2010).

Kim, M. S., Chung, Y. R., Suh, E. H. & Song, W. S. J. Eutrophication Nakdong River Stat. Analtsis Envitonmental Factors 17, 105–115 (2002).

D. H., B., Jung, I. W. & Chang, H. J. Long-term trend of precipitation and runoff in Korean river basins. H P I J. 22, 2644–2656 (2008).

Borzée, A. et al. Yellow sea mediated segregation between North East Asian dryophytes species. PLOS ONE. 15, e0234299. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234299 (2020).

Kang, J. & Yeo, H. J. O. J. o. C. E. Survey and analysis of the sediment transport for river restoration: The case of the Mangyeong River. 5, 399–411 (2015).

Waraniak, J. M. et al. Landscape genetics reveal broad and fine-scale population structure due to landscape features and climate history in the Northern Leopard frog (Rana pipiens) in North Dakota. Ecol. Evolut 9 (3), 1041–1060 (2019).

Marsh, D. M. et al. Effects of roads on patterns of genetic differentiation in red-backed salamanders. Plethodon Cinereus. 9, 603–613 (2008).

Funk, W. C. et al. Population structure of Columbia spotted frogs (Rana luteiventris) is strongly affected by the landscape. Mol. Ecol. 14, 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02426.x (2005).

Zalewski, A., Piertney, S. B., Zalewska, H. & Lambin, X. J. M. E. Landscape barriers reduce gene flow in an invasive carnivore: geographical and local genetic structure of American Mink in Scotland. 18, 1601–1615, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04131.x

Sánchez-Montes, G., Wang, J. & Ariño, A. H. & Martínez-Solano, Í. Mountains as barriers to gene flow in amphibians: quantifying the differential effect of a major mountain ridge on the genetic structure of four sympatric species with different life history traits. 45, 318–331, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13132

Andersen, D. et al. Elevational distribution of amphibians: resolving distributions, patterns, and species communities in the Republic of Korea. Zoological Stud. 61, e25 (2022).

Choi, S. W. & Jang, B. J. J. J. o. A.-P. E. Effects of elevation and slope on the alpha and beta diversity of ground-dwelling beetles in Mt. Jirisan National Park, South Korea. 25, 101993 (2022).

Gregory-Wodzicki, K. M. J. G. s. o. A. b. Uplift history of the Central and Northern Andes: a review. 112, 1091–1105 (2000).

Esquerré, D., Brennan, I. G., Catullo, R. A., Torres-Pérez, F. & Keogh, J. S. J. E. How mountains shape biodiversity: the role of the Andes in biogeography, diversification, and reproductive biology in South america’s most species-rich Lizard radiation. (Squamata: Liolaemidae). 73, 214–230 (2019).

Lu, B. et al. Coalescence patterns of endemic Tibetan species of stream salamanders (Hynobiidae: Batrachuperus). Mol. Ecol. 21 (13), 3308–3324 (2012).

de Queiroz, K. J. P. o. t. C. A. o. S. A unified concept of species and its consequences for the future of taxonomy. (2005).

Rahel, F. J. Biogeographic barriers, connectivity and homogenization of freshwater faunas: it’s a small world after all. Freshwater Biol. 52 (4), 696–710 (2007).

Figueiredo-Vázquez, C., Lourenço, A. & Velo-Antón, G. Riverine barriers to gene flow in a salamander with both aquatic and terrestrial reproduction. Evol. Ecol. 35 (3), 483–511 (2021).

Godinho, M. B. D. C., & Da Silva, F. R. The influence of riverine barriers, climate, and topography on the biogeographic regionalization of Amazonian anurans. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 3427 (2018).

Devitt, T. J., Baird, S. J. & Moritz, C. Asymmetric reproductive isolation between terminal forms of the salamander ring species ensatina eschscholtzii revealed by fine-scale genetic analysis of a hybrid zone. BMC Evol. Biol. 11 (1), 1–15 (2011).

Potts, L. J. et al. Environmental factors influencing fine-scale distribution of antarctica’s only endemic insect. Oecologia 194 (4), 529–539 (2020).

Canestrelli, D. et al. What triggers the rising of an intraspecific biodiversity hotspot? Hints from the agile frog. Sci. Rep. 4, 5042 (2014).

Jeon, J. Y. et al. The Asian plethodontid salamander preserves historical genetic imprints of recent Northern expansion. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 9193 (2021).

Canestrelli, D. et al. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of the apennine yellow-bellied Toad bombina pachypus, with implications for conservation. Mol. Ecol. 15(12), 3741–3754 (2006).

Li, M. M. et al. Geochronology and petrogenesis of early pleistocene dikes in the Changbai mountain volcanic field (NE China) based on geochemistry and Sr-Nd-Pb-Hf isotopic compositions. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 729905 (2021).

Pirani, R. M. et al. Testing main Amazonian rivers as barriers across time and space within widespread taxa. J. Biogeogr. 46(11), 2444–2456 (2019).

Hairston, N. G., Nishikawa, K. C. & Stenhouse, S. L. The evolution of competing species of terrestrial salamanders: niche partitioning or interference? Evol. Ecol. 1 (3), 247–262 (1987).

Pansarin, E. R. & Ferreira, A. W. J. B. Elucidating cryptic sympatric speciation in terrestrial orchids. 828491 (2019).

Rosser, N. et al. Extensive range overlap between Heliconiine sister species: evidence for sympatric speciation in butterflies? BMC Evol. Biol 15 (1), 1–13 (2015).

Peterson, A. T., Soberón, J. & Sánchez-Cordero, V. Conservatism of ecological niches in evolutionary time. 285, 1265–1267, doi: (1999). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5431.1265

Soberón, J. & Miller, C. P. J. M. M. Evolución de los nichos ecológicos. 49, 83–99 (2009).

Encarnación-Luévano, A., Peterson, A. T. & Rojas-Soto, O. R. Burrowing habit in Smilisca frogs as an adaptive response to ecological niche constraints in seasonally dry environments. Front. Biogeogr. 13(4) (2021).

Acknowledgements

This project was financially funded by Rural Development Administration of Korea grant (RS-2024-00397542) to YJ. DB was supported by funding provided by the University of Arizona One Health Research Initiative and by the Technology and Research Initiative Fund/Water, Environmental, and Energy Solutions Initiative administered by the University of Arizona Office for Research, Innovation and Impact and the Arizona Institute for Resilience. This study did not require any specific permits or approvals from regulatory bodies, as all data used was obtained from open data sources, and no fieldwork was conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TEU: methodology, investigation, data curation, writing —original draft, visualization; DAB: methodology, investigation, writing —review, and editing, visualization; AB: methodology, investigation, writing—review, and editing; YKJ: investigation, writing—review, and editing. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Um, T.E., Bliss, D.A., Borzée, A. et al. Biogeographic barriers and environmental gradients reveal distribution limits in Hynobius salamanders. Sci Rep 15, 38345 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22226-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22226-5