Abstract

Inkjet printing has been extensively employed across various industrial applications due to its capability to produce high-resolution outputs and accommodate a diverse range of materials. However, its printing speed (volumetric printing rate or volumetric productivity) has remained a bottleneck for large-scale manufacturing. This study introduces a new strategy aimed at enhancing the speed of piezoelectric inkjet printing by optimizing waveform parameters. Expanding on our prior work, which analyzed the relationship between driving signal parameters and key factors like droplet volume and jetting frequency, we now focus on optimizing these parameters to maximize printing speed. To establish a fair comparison across different setups, an equivalent printing speed metric was first defined, normalizing for configuration differences such as nozzle size. Using this metric, a benchmark driving signal was designed to achieve the equivalent printing speed of a selected commercial printhead under comparable conditions. The benchmark driving signal was then optimized to enhance printing performance, and the results were validated experimentally with a custom-built setup equipped with a high-speed camera for real-time droplet formation analysis. Our findings demonstrate that the optimized signal achieves successful jetting and improves printing speed, showing up to a five-fold increase compared to the benchmark signal in our experimental setup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inkjet printing has been a prominent technology across various industries for several decades. Among its various forms, piezoelectric drop-on-demand (DOD) printing has garnered considerable interest due to its ability to precisely deposit a wide variety of materials1,2,3. This versatility has established piezoelectric DOD printing as an essential tool for applications such as printed electronic devices4, binder-based additive manufacturing5, biological printing6, and many other fields7,8,9,10.

Printing performance in inkjet technology is primarily determined by two key factors: quality and speed. The ability to precisely control droplet formation is fundamental for achieving high-quality prints. Numerous studies have shown that the driving signal’s waveform plays a pivotal role in determining inkjet print quality, as it directly controls printhead actuation and, consequently, droplet formation, influencing spatial accuracy, feature size, and consistency11,12,13. Recent studies have applied machine learning14,15,16 and multi-objective optimization techniques17,18,19,20 to improve the quality of additive manufacturing processes, including both inkjet and aerosol jet printing.

Despite extensive research on optimizing waveform parameters to improve inkjet printing quality, the enhancement of printing speed—defined as the volume of ink ejected per unit time—has received comparatively less attention. In this study, printing speed is quantified as the product of droplet volume V and jetting frequency f (defined as the number of droplets produced per second), representing the volumetric throughput from a single nozzle. For a printhead with multiple nozzles, the total output is given by:

Here, N represents the total number of active nozzles. This metric serves as the primary optimization objective in our waveform design framework. Key variables like droplet volume, jetting frequency, and driving waveform parameters all affect printing speed1,21,22. A common approach to increasing printing speed involves boosting droplet size, which can be accomplished by increasing the driving voltage or modifying the dwell time23,24,25. However, larger droplet volumes are generally associated with lower achievable ejection frequencies. This is because expelling a larger volume requires a longer actuation time and a longer nozzle refill duration, which slows the repetition rate of the jetting cycle. As a result, even though larger droplets can contribute to higher volumetric output per ejection, their slower cycle time can reduce overall throughput. Self and Wallace26 showed that increasing the time for energy input can produce droplets with radii reaching up to twice the radius of the nozzle. However, this technique significantly lengthens the jetting process, decreasing the jetting rate from 15 to 1 kHz, which in turn adversely impacts the overall printing speed. Studies have demonstrated that using a double-pulse waveform with extended time intervals can produce larger droplets compared to those generated by single-pulse signals. However, the droplets generated in these studies remained smaller than the nozzle diameter used in those experiments, and no improvement in the overall volumetric printing rate was observed27,28.

Increasing the jetting frequency is an alternative strategy to enhance inkjet printing speed. Khalate et al.29,30 and Ezzeldin et al.31 adopted an optimization-based feedforward control method aimed at rapidly reducing residual oscillations, thus maximizing the jetting frequency of DOD inkjet printers. In another study, Yang et al.32 employed multi-pulse crosstalk modulation to fine-tune the actuation waveform, enabling higher frequencies in DOD inkjet operations. Based on Iterative Learning and Equivalent Circuit Model, Wang et al.33 developed a waveform design method that suppressed residual vibrations and achieved a sevenfold increase in jetting frequency. Using the lumped element model of a recirculating piezoelectric inkjet printhead, Shah et al.12 enhanced bipolar waveforms and demonstrated that a second pulse voltage set to one-third of the first pulse could effectively minimize residual vibrations within the printhead channel, thereby enhancing jetting frequency. Additionally, Miers and Zhou34 demonstrated that it is possible to generate droplets at high frequencies by increasing the nozzle’s energy input to boost ejection velocity, which can provide a larger driving force than surface tension to break up the droplet and thus lead to higher jetting frequency.

In summary, numerous studies have explored how the driving signal affects both droplet volume and jetting frequency, both of which play significant roles in determining printing speed. Yet, a comprehensive investigation that simultaneously considers these factors with the aim of optimizing printing speed remains scarce. To address this gap, achieving an optimal balance between droplet volume and jetting frequency is crucial. It is important to note that the optimization does not aim to independently maximize both droplet size and ejection frequency, as these parameters are physically interdependent. Larger droplets inherently require more time for formation and pinch-off, which limits the maximum achievable frequency34. On the other hand, increasing the ejection frequency often necessitates smaller droplets to complete the formation process within each cycle. Therefore, the optimization framework seeks to balance these trade-offs by identifying waveform parameters that jointly maximize the volumetric throughput (printing speed), while ensuring stable droplet ejection. Since the number of nozzles mainly scales the overall speed, our research prioritizes optimizing the performance of a single nozzle, which can later be applied to multi-nozzle configurations. This focused strategy allows us to identify the main elements that impact printing speed and to better understand the dynamics of droplet formation.

Previously, we developed an analytical model that forecasts how the driving signal influences both droplet volume and jetting frequency, the two main determinants of inkjet printing speed35. A brief summary of the analytical model, including its governing equations and assumptions, is provided in the Supplementary Information (Section S1) for clarity and completeness. Building on this foundation, the present study focuses on optimizing the driving signal waveform to achieve higher printing speeds. Notably, we introduce the concept of ‘equivalent printing speed’ for a single nozzle, which considers variations in hardware configuration and their impact on droplet ejection. Equivalent printing speed is a comparative metric used to benchmark our system against commercial printheads under different configurations and printing conditions. It reflects the printing speed that a standard commercial system would achieve under similar nozzle size and printing conditions, allowing for a normalized comparison between different printheads. Using this approach, we benchmark our system against commercial printheads more accurately. Our findings demonstrate that the optimized signal achieves successful jetting and improves printing speed, showing up to a five-fold increase compared to the benchmark signal in our experimental setup.

This paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the optimization problem and establishes a reference driving signal to serve as the starting point for optimization. Section 3 describes the methodology for waveform optimization in detail. Section 4 presents the experimental validation of the optimized waveform parameters. Lastly, Sect. 5 concludes the study and discusses potential avenues for future research.

Methodology

The primary objective of this study is to fine-tune the driving signal waveform of an existing inkjet printhead to enhance its overall printing speed. To achieve this, a commercial inkjet printhead is selected as the benchmark. Observing the jetting process directly in commercial inkjet printheads is challenging due to their small nozzle sizes, typically below 100 µm. These nozzles are often housed in compact and opaque structures, limiting optical access. Moreover, the microscale nozzle dimensions and high-speed ejection dynamics impose significant constraints on high-speed imaging, including limited pixel resolution, shallow depth of field, the requirements of high framerate and bandwidth for data transfer, and the demanding requirements for lighting conditions that don’t impact the droplet formation dynamics. To address these challenges, we developed a custom-designed inkjet system featuring a larger 200-µm nozzle. This configuration enables high-resolution visualization of droplet formation, breakup, and satellite behavior, which is critical for validating the analytical model and enforcing the physical constraints in the waveform optimization process.

To establish comparability between the commercial inkjet printhead and our custom-designed inkjet system, the equivalent printing speed for both setups was determined. Next, a suitable waveform was identified to match this equivalent speed for the custom setup, which was then optimized using the analytical model developed in our previous work35, with the goal of improving the overall printing speed. To systematically determine the optimal waveform parameters, we employed a surrogate-based optimization solver in MATLAB. This solver iteratively evaluates candidate waveforms, relying on an analytical droplet formation model to maximize printing speed while maintaining droplet stability. Once the optimal driving signal is obtained, we will perform experimental validation to assess the speed improvement against the established benchmark. Figure 1 provides an overview of this process.

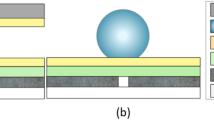

Benchmark commercial printhead

A DOD inkjet printing system, illustrated in Fig. 2, was previously developed featuring a 200 µm nozzle and utilizing a Newtonian ink composed of glycerin, water, and isopropanol (GWI) in weight proportions of 34%, 53%, and 13%, respectively. The ink exhibits a density of 1.05 g/cm3, a viscosity of 5 mPa·s, and a surface tension of 35 mN/m. The operation of the system begins with programming the driving signal on a computer, which is then sent to the control circuit. Once verified through an oscilloscope, the power supply is adjusted to transmit the signal to the piezoelectric transducer. The transducer’s deformation generates the force needed to eject droplets from the nozzle. A high-speed camera captures the ejection process in real-time, and the resulting images are analyzed on a computer to study the droplet formation dynamics. Detailed information about the experimental setup can be found in our earlier work. To evaluate printing speed improvements using the optimized waveform, a suitable commercial printhead must be selected as a benchmark first, ensuring compatibility with our operational conditions and accurately representing the fluid dynamics involved in droplet formation. Although the commercial printhead itself is not directly used in the experiments, it serves as a performance reference to contextualize the results. By establishing this reference point, we can assess the relative improvement achieved through waveform optimization while accounting for differences in nozzle size and hardware configuration.

Although various actuation methods can be used to generate droplets, studies indicate that jetting dynamics are mainly governed by the properties of the ink and the associated operational conditions36. For Newtonian fluids, the behavior of the ink can be effectively represented using dimensionless Ohnesorge number (Oh), which represents the balance between viscous force, inertial force, and surface tension force, and remains unaffected by droplet velocity:

Here \(\mu\), \(\rho\), \(\sigma\) are the ink properties (viscosity, density, and surface tension), and D refers to the characteristic length, which is typically represented by the nozzle diameter. To describe operational conditions, the dimensionless Weber number (We) is commonly employed:

Here \(u\) represents the characteristic droplet velocity. Together, the Ohnesorge and Weber numbers define the droplet generation regime, and maintaining both within appropriate ranges is essential for stable droplet formation, minimal satellite generation, and consistent printing quality. In our case (Table 1), the calculated values fall within well-established ranges associated with stable ejection37,38, confirming the reliability of our inkjet printing process.

To ensure comparable operational conditions and accurately represent the behavior of droplet formation in both setups, it is crucial that the two non-dimensional parameters, namely the Ohnesorge number (Oh) and the Weber number (We), exhibit similar values. By matching Oh and We values, the fluid dynamic regime of our custom setup remains representative of those observed in commercial printheads, even though the absolute nozzle diameter differs. This approach facilitates the transferability of the optimization results to other systems, enabling broader applicability of the findings across different nozzle sizes and printing conditions. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that the applicability of this approach to smaller nozzles—where viscous and thermal effects become more prominent—requires further investigation, which we aim to pursue in future work.

Table 1 provides a comparison of these parameters between our setup and representative commercial printheads. Our DOD inkjet setup utilizes a 200 µm nozzle that delivers a droplet velocity of approximately 2 m/s. While this velocity is moderate, the large nozzle produces a correspondingly large droplet with high inertia, which greatly enhances its directional stability. This is quantitatively supported by the calculated Weber number of 24, indicating that inertial forces are sufficiently dominant over surface tension to ensure a straight trajectory but not so high as to cause splashing. The directional stability is experimentally confirmed by high-speed imaging (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information), which shows no significant deviation of the droplet’s flight path from the nozzle axis. Among the commercial printheads considered, the Xaar 128/80W demonstrates the most similar Oh and We values to our system. Therefore, it is selected as the benchmark printhead, as both setups exhibit comparable droplet dynamics.

Equivalent printing speed concept

The nozzle size is a key factor affecting inkjet printing speed. Given that the nozzle diameters differ between our inkjet printing system and the chosen reference commercial printhead, directly comparing their inkjet printing speeds is impractical. To resolve this discrepancy, it is essential to develop a method for normalizing printing speed relative to nozzle dimensions, allowing for a fair and accurate comparison. To achieve this, we introduce the concept of "equivalent printing speed," which standardizes the printing speed across different nozzle sizes, enabling a fair evaluation of various setups.

The theoretical jetting frequency for a standard commercial piezoelectric DOD inkjet printhead can be approximated using the following equation34:

If the droplet size is assumed to be roughly equivalent to the nozzle size, the printing speed for a single nozzle can be estimated as:

According to this equation, the printing speed scales with D3/2, allowing it to be normalized relative to the nozzle size. For the chosen benchmark commercial printhead, its equivalent printing speed (\({W}_{equ}\)) corresponding to our setup nozzle (200 µm, \({D}_{equ}\)) can then be calculated as:

Here, \({W}_{equ}\) and \({W}_{0}\) represent the equivalent and actual printing speed, \({D}_{equ}\) and \({D}_{0}\) denote the equivalent and actual nozzle diameter, respectively. Thus, for the selected benchmark commercial printhead from previous section, Xaar 128/80W printhead that can generate an 80 pL drop volume with typical firing frequency of 5.5 kHz, its equivalent printing speed, when normalized to the same nozzle diameter as our inkjet setup, can be calculated as follows:

Benchmark driving signal identification

The optimization process for the driving signal begins with identifying a signal for our inkjet setup capable of matching the equivalent printing speed. This benchmark is critical and acts as the reference point for optimization. To derive it, we applied our previously established analytical model, which relates driving signal parameters to temporal changes in ejection velocity and necking radius. The general form of the model is as follows (the detailed equations are excluded for simplicity and are available in35).

where \(u\left(t\right)\) represents the jetting velocity, which is defined as the instantaneous velocity of the ink as it exits the nozzle during droplet ejection, T1-T5, are the time intervals of the signal, while E1 and E2 denote the applied voltages. Additionally, the filament radius at the nozzle exit is denoted as \(R(t)\). In the current formulation, R(t) is expressed as a function of jetting velocity and time under the assumption of constant ink properties. While viscosity, surface tension, and density inherently influence filament dynamics, they are not explicitly parameterized in this function. This simplification was adopted to isolate the effect of waveform parameters during optimization. Future extensions of the model will aim to incorporate material-dependent terms in R(t) for broader applicability. By integrating u(t) over time, the droplet volume can be determined, whereas droplet breakup occurs when R(t) approaches zero. These relationships facilitate the estimation of printing speed, expressed as:

By utilizing Eqs. (8), (9), and (10), it is possible to adjust the driving signal parameters and estimate the resulting printing speed.

The benchmark signal was identified through a systematic procedure leveraging this model: (1) Define the target printing speed to match the equivalent speed of the chosen commercial printhead; (2) Systematically generate a variety of driving signals; (3) Use our model to predict the printing speed for each signal; (4) Calculate the fractional relative error between the estimated printing speed—predicted from each generated driving signal—and the predefined target printing speed; (5) Retain signals with a relative error below 1%; (6) Experimentally validate the shortlisted signals; (7) Identify and designate the best-performing signal from the validated results as the benchmark. Figure 3 illustrates the final benchmark signal, with the corresponding ejection process depicted in Fig. 4. Although the Xaar 128/80W printhead was selected as a benchmark due to its similar Ohnesorge and Weber numbers, its proprietary waveform is not publicly available. As a result, a standard bipolar trapezoidal waveform—previously validated in our experimental setup—was used as the benchmark signal in this study. While this waveform does not replicate commercial signals, it provides a consistent and controllable baseline for evaluating the optimized waveform’s performance. Its parametric structure offers flexibility for tuning jetting dynamics and enables meaningful physical interpretation within the optimization framework. The experimentally produced droplet has a diameter of 146 ± 5 µm, with a measured droplet detachment frequency of approximately 2100 ± 20 Hz, resulting in a measured printing speed of (3.42 ± 0.35) × 106 pL/s, which closely matches the equivalent printing speed of the benchmark commercial printhead (3.23 × 10⁶ pL/s).

Waveform optimization

Given the complexity of droplet ejection physics and the numerous waveform parameters involved, conventional trial-and-error approaches prove inadequate for identifying the optimal waveform to maximize the printing speed. In our previous study, we developed an analytical model that predicts two critical factors influencing inkjet printing speed—droplet volume and jetting frequency—based on the bipolar driving signal parameters. However, the optimal parameters for achieving maximum printing speed remain undetermined.

In this section, we aim to determine the optimal bipolar driving signal using the analytical model, leveraging an optimization algorithm with appropriate constraints and boundaries for the driving signal parameters. Among various available optimization solvers, we have selected the surrogate optimization solver due to its effectiveness in evaluating complex and computationally demanding objective functions. The fundamental concept of surrogate optimization lies in building a simplified model that approximates the objective function using a limited number of evaluations. In this context, our previously developed analytical model will serve as the surrogate. Here, we will formulate the optimization problem to maximize inkjet printing speed while ensuring consistent droplet ejection and preventing the generation of satellites.

Objective function identification

The waveform optimization’s objective function (S) is defined as follows:

Here, W represents the estimated printing speed for a given driving signal, while \({T}_{b}\) denotes the pinch-off time. The optimization solver is designed to minimize the objective function, with a negative sign incorporated to ensure the maximization of printing speed.

Control variables

Control variables (also known as design variables or decision variables) are the parameters that can be manipulated during the optimization process to achieve an optimal solution. For this specific optimization, they are the parameters of the actuation signal, as depicted in Fig. 3. The benchmark driving signal from Section II.C serves as the initial condition for initializing these design variables.

Constraints

Constraints are essential in guiding the optimization process by ensuring that solutions satisfy specific requirements and avoid potential issues, such as the formation of satellite droplets. The specific constraints for this optimization, which encompass all design variables, are detailed below.

Here the aspect ratio, denoted as \({L}_{0}\), is defined as the ratio of the ejected filament’s length to its diameter. Derived from previously established ejection regimes 39,40,41, Eqs. (12-1) and (12-2) are formulated based on the properties of the ink examined in this work. Specifically, the filament length-to-diameter ratio was constrained to remain below 3.5, based on prior empirical observations that higher aspect ratios are associated with increased satellite formation40. This constraint was integrated into the optimization to ensure that all candidate waveforms supported stable, single-droplet ejection.

Additional constraints on the driving signal parameters are imposed to achieve maximum printing speed while avoiding undesirable ejections, such as satellite droplets or no ejection. These constraints are derived from prior research investigating the effects of driving signals on droplet formation dynamics19,42,43. Particularly, to ensure compatibility with our previous model, Eq. (12-3) enforces that the driving signal remains bipolar. Furthermore, Eqs. (12-4) and (12-5) impose reasonable bounds on signal timing, as discussed in43. During the ejection initiation phase, the velocity starts at zero, and the ink is expelled as the piezoelectric force overcomes surface tension, as expressed in Eq. (12-6).

Variable boundaries

Table 2 provides the boundaries for all variables in the bipolar driving signal waveform, determined based on the movement of the piezoelectric actuator and the dynamics of ejection. In T1, the piezo actuator moves downward under the influence of a positive voltage, creating a positive pressure within the ink chamber and pushing the ink out of the nozzle. In T2, the piezo actuator holds its position, allowing the liquid to continue its downward flow. In T3, the piezo actuator rises to the position corresponding to the negative voltage, slowing the fluid flow. The piezo actuator then holds this position through T4, before returning to its resting state in T5.

To stabilize the piezoelectric actuator effectively, the minimum limits for phases T1, T3, and T5 are established based on the actuator’s resonant/natural period (~ 55 us), which defines the shortest time necessary for the piezo to reach the target position. Setting a lower value would be unrealistic, as the piezoelectric actuator cannot react instantaneously to voltage shifts, resulting in unstable vibrations and unsuccessful ejection attempts44. The dwell time for phases T2 and T4 could theoretically be minimized to zero, if the T1 or T3 durations create adequate momentum for successful ink release or droplet formation. Nevertheless, to ensure reliable ejection performance, the minimum dwell time for the current study is constrained to a minimum of 1 µs. This value is empirically determined based on the dynamic response limits of the current actuator and experimental configuration. However, we acknowledge that with the development of faster piezoelectric actuators and more responsive driving electronics, it may be possible to achieve stable ejection with even shorter dwell times. Exploring this possibility could further enhance printing speed.

To ensure the generation of a bipolar trapezoidal signal for the input waveform, the lower bounds for voltage (E1 and E2) are fixed at ± 1 V, with the upper limit determined by the operational voltage capacity of the piezoelectric actuator (± 100 V). For other variables, the upper bounds are intentionally kept high to avoid overly restricting the design variables, thereby allowing the exploration of all possible solutions and ensuring that the potential optimal value is not inadvertently excluded.

After defining the objective function, design variables, and constraints, a surrogate-based optimization was conducted to efficiently determine the optimal waveform parameters (T1–T5, E1, and E2) that maximize inkjet printing speed. This process leverages an analytical model capable of predicting both droplet volume and jetting frequency. To reduce the computational cost associated with repeated evaluations of the analytical model, a surrogate model was constructed using radial basis function (RBF) interpolation. The optimization follows an iterative workflow (Fig. S2): it begins with an initial sampling of waveform configurations, which are evaluated using the full analytical model. These evaluations are used to construct the RBF-based surrogate model that approximates the objective function. The optimizer then searches for optima on this surrogate surface, selects promising candidates, evaluates them using the true analytical model, and incorporates the new results to refine the surrogate model. This iterative process continues until one of the stopping criteria is satisfied: either the total number of function evaluations reaches 1200, or the relative improvement in the objective function over recent iterations falls below a predefined convergence threshold of 0.1%. Throughout the optimization, all physical and operational constraints are strictly enforced. Only parameter sets that satisfy these constraints are accepted for both surrogate model construction and evaluation, ensuring that the final optimized waveform not only enhances printing speed but also maintains physical feasibility and stable droplet formation.

Optimization results and experimental validation

This section begins with the presentation of the optimization results, detailing the optimal driving signal waveform parameters and the corresponding printing speed. Subsequently, an experiment is conducted using the optimized parameters to validate the driving waveform, with the experimentally measured printing speed compared to the optimization results. Finally, an analysis of the optimal waveform parameters and the achieved printing speed is provided.

To evaluate the behavior of the optimization algorithm, we analyze the convergence curve shown in Fig. 5, which illustrates the evolution of the objective function across successive iterations. A sharp reduction is observed during the first 40 iterations, followed by a more gradual decline. Around iteration 70, the improvement rate slows significantly, suggesting that the optimization is nearing convergence. However, the relative improvement does not fall below the predefined threshold of 0.1%, and the total number of function evaluations does not reach the maximum limit of 1,200. Consequently, the algorithm continues until iteration 200, where the convergence criterion is finally satisfied. The optimized waveform achieves a maximum predicted printing speed of 1.97 × 10⁷ pL/s, demonstrating stable algorithm behavior and effective waveform optimization.

Figure 6 shows the final optimized driving waveform in comparison to the initial benchmark signal. The optimal driving waveform aims to achieve a balance between increasing droplet volume and maximizing breakup frequency. Notably, the optimized waveform exhibits a significant increase in the duration of T₁ and the amplitude of the positive driving voltage compared to the benchmark signal. T₁ corresponds to the downward motion of the piezoelectric actuator, which expels ink from the chamber. The emergence of T₁ extension and increased positive voltage amplitude as key factors can be attributed to enhanced fluid inertia and energy transfer from the piezoelectric actuator. Specifically, a longer T₁ duration facilitates sustained pressure buildup, while a higher voltage amplitude intensifies the actuation force, together resulting in more efficient droplet ejection and increased printing speed. This result is consistent with our model predictions and supported by previous studies24,45,46.

It is important to note that a longer T1 delays the onset of negative pressure during T3, increasing breakup time and reducing jetting frequency. However, the associated increase in droplet volume compensates for the lower frequency, resulting in improved volumetric throughput. This trade-off between droplet size and breakup time is consistent with the findings of Dong et al.47 and highlights a key optimization strategy: balancing waveform energy input with ejection timing to enhance throughput while maintaining stable jetting.

The optimized waveform was experimentally validated, as depicted in Fig. 7, which demonstrates the successful ejection of a 288 ± 7 µm droplet at a breakup frequency of 1428 ± 20 Hz. This optimized waveform led to a printing speed of (1.79 ± 0.13) × 107 pL/s, marking a fivefold improvement over the baseline waveform and demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy in enhancing droplet throughput. High-speed imaging further confirmed the clean ejection of a single, stable droplet without satellite formation, thereby validating the effectiveness of the applied waveform optimization constraints.

It is important to note that the optimized droplet size in this study is a characteristic of the 200 µm nozzle chosen for our validation experiments and exceeds typical requirements for high-resolution applications. The larger nozzle was intentionally selected to enable high-resolution visualization for validating our analytical model, while the fluid dynamics were kept representative of commercial systems by matching the Ohnesorge and Weber numbers. The optimization framework itself is generally applicable and does not inherently limit printing resolution. For applications requiring finer features, the same methodology would be applied to a system with a smaller nozzle than the desirable droplet size to enhance its volumetric throughput while maintaining its native high resolution. Thus, while the primary focus here was to demonstrate a fivefold enhancement in printing speed via waveform optimization, future work will explore the application of this validated framework to resolution-sensitive scenarios using smaller nozzles. It is worth noting that the generation of larger droplets contributes to increased volumetric throughput but may result in reduced ejection velocity, potentially influencing jetting consistency and droplet stability. Importantly, spatial resolution is not inherently compromised, as it is primarily determined by nozzle size—a design parameter that can be selected based on application requirements. Nevertheless, the impact of reduced velocity on droplet behavior should be carefully considered when applying the framework to high-precision or stability-sensitive printing tasks.

This study focused on a single Newtonian ink formulation, nozzle diameter, and actuation configuration to isolate and analyze the effects of waveform parameters on jetting performance. However, we recognize that the optimization framework should be validated under a broader set of conditions—including viscoelastic fluids and inks containing dispersed particulates, smaller nozzle diameters, and alternative system configurations. Future work will systematically explore these variables to evaluate the robustness, adaptability, and industrial relevance of the proposed methodology. Furthermore, while the current optimization framework effectively identified a high-performance waveform, convergence behavior from multiple initial conditions was not explored in this study. Future work will address this limitation by systematically evaluating the sensitivity of optimization outcomes to different initial parameter settings. Moreover, the ink used in this study exhibits a Z number of approximately 12.5, placing it near the upper boundary of the stable inkjet printing regime. While this choice enabled high-speed jetting, the effectiveness of the optimized waveform may vary for inks with different rheological properties. Future work will extend the current model and optimization framework to a wider range of Z values, particularly in the lower printable regime (Z ≈ 5–6), to further assess waveform robustness and adaptability across diverse ink types. Additionally, it is important to note that the present study was conducted using a single Newtonian ink formulation (glycerol–water–isopropanol). As such, the applicability of the optimized waveform to other ink types, particularly non-Newtonian fluids or particle-laden suspensions commonly used in industrial applications, need to be further validated. These inks often exhibit complex rheological behaviors that could influence droplet formation dynamics and require adaptation of the analytical model or adjustment of optimization constraints. Finally, since the surrogate optimization framework is grounded in an analytical model developed in our prior work35, the accuracy of its predictions inherently depends on the fidelity of that model. To enhance confidence in the optimization results, future work will include a sensitivity analysis of critical model parameters—such as ink viscosity, surface tension, density, and piezoelectric response time—to quantify their influence on predicted jetting behavior and optimized waveform performance. In parallel, we plan to implement multi-objective optimization strategies, such as Pareto front analysis, to explore trade-offs between printing speed and droplet consistency and to generate multiple candidate waveforms optimized for specific application needs.

Conclusion

This study introduces a physics-informed optimization framework to enhance piezoelectric inkjet printing throughput by tuning driving waveform parameters based on an analytical model of droplet formation dynamics. Using a surrogate-based optimization solver, we identified an improved waveform that achieved a fivefold increase in printing speed compared to the benchmark, validated experimentally. Unlike prior studies that primarily target droplet morphology, our approach emphasizes throughput and offers a systematic, computationally efficient optimization strategy. However, several limitations exist. The optimization was conducted from a single initial condition and did not consider morphology metrics such as tail length or roundness. The experimental validation employed a custom-built setup with Newtonian ink and a relatively large nozzle (200 µm), which, despite matching dimensionless parameters, may not fully represent high-resolution or industrial conditions. Future work will address these limitations by exploring sensitivity to initial conditions, integrating multi-objective optimization (e.g., speed vs. morphology), and extending validation to non-Newtonian and particle-laden inks and smaller nozzle sizes. Additionally, we will investigate multi-pulse waveform strategies to further enhance adaptability and performance in drop-on-demand inkjet systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aqeel, A. B., Mohasan, M., Lv, P., Yang, Y. & Duan, H. Effects of the actuation waveform on the drop size reduction in drop-on-demand inkjet printing. Acta. Mech. Sin. 36, 983–989 (2020).

Buga, C. & Viana, J. C. Optimization of print quality of inkjet printed PEDOT: PSS patterns. Flex. Print. Electron. 7(4), 045004 (2022).

Colton, T., Inkley, C., Berry, A. & Crane, N. B. Impact of inkjet printing parameters and environmental conditions on formation of 2D and 3D binder jetting geometries. J. Manuf. Process. 71, 187–196 (2021).

Zhang, C. J., McKeon, L., Kremer, M. P., Park, S.-H., Ronan, O., Seral-Ascaso, A., Barwich, S., Coileáin, C. Ó., McEvoy, N., and Nerl, H. C. Additive-free MXene inks and direct printing of micro-supercapacitors, MXenes, pp. 463–485: Jenny Stanford Publishing, (2023)

Cheng, T.-Y., Weng, Y.-C., Chen, C.-H. & Liao, Y.-C. Reactive binder-jet 3D printing process for green strength enhancement. Addit. Manuf. 74, 103734 (2023).

Zhao, D. et al. Sequential-crosslinking facilitated droplet-droplet collision inkjet 3D printing of soft biomaterials. Addit. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2025.104809 (2025).

Carey, T. et al. Fully inkjet-printed two-dimensional material field-effect heterojunctions for wearable and textile electronics. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1–11 (2017).

Derby, B. Inkjet printing of functional and structural materials: fluid property requirements, feature stability, and resolution. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 40, 395–414 (2010).

Evans, S. E. et al. 2D and 3D inkjet printing of biopharmaceuticals–A review of trends and future perspectives in research and manufacturing. Int. J. Pharm. 599, 120443 (2021).

Gibertini, E., Lissandrello, F., Bertoli, L., Viviani, P. & Magagnin, L. All-Inkjet-Printed Ti3C2 MXene Capacitor for Textile Energy Storage. Coatings 13(2), 230 (2023).

Kim, S., Cho, M. & Jung, S. The design of an inkjet drive waveform using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 4841 (2022).

Shah, M. A. et al. Actuating voltage waveform optimization of piezoelectric inkjet printhead for suppression of residual vibrations. Micromachines 11(10), 900 (2020).

Sui, C., and Zhou, W. A model for the effects of driving signal on piezoelectric inkjet printing speed, (2022)

Ng, W. L., Goh, G. L., Goh, G. D., Ten, J. S. J. & Yeong, W. Y. Progress and opportunities for machine learning in materials and processes of additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 36(34), 2310006 (2024).

Zhang, H., Hong, E., Chen, X. & Liu, Z. Machine learning enables process optimization of aerosol jet 3D printing based on the droplet morphology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15(11), 14532–14545 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. Machine learning in additive manufacturing: a review. Jom 72(6), 2363–2377 (2020).

Goh, G. L., Zhang, H., Goh, G. D., Yeong, W. Y. & Chong, T. H. Multi-objective optimization of intense pulsed light sintering process for aerosol jet printed thin film. Mater. Sci. Addit. Manuf. 1(2), 10–10 (2022).

Zhang, H., Choi, J. P., Moon, S. K. & Ngo, T. H. A hybrid multi-objective optimization of aerosol jet printing process via response surface methodology. Addit. Manuf. 33, 101096 (2020).

Wang, H. & Hasegawa, Y. Multi-objective optimization of actuation waveform for high-precision drop-on-demand inkjet printing. Phys. Fluids 35(1), 013318 (2023).

Zhang, H., Liu, Z., Yin, S. & Xu, H. A hybrid multi-objective optimization of functional ink composition for aerosol jet 3D printing via mixture design and response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2513 (2023).

Zhu, H. et al. Residual vibration suppression of piezoelectric inkjet printing based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. Micromachines 15(10), 1192 (2024).

Gan, H. Y., Shan, X., Eriksson, T., Lok, B. K. & Lam, Y. C. Reduction of droplet volume by controlling actuating waveforms in inkjet printing for micro-pattern formation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 19(5), 055010 (2009).

Hamad, A. H., Salman, M. I. & Mian, A. Effect of driving waveform on size and velocity of generated droplets of nanosilver ink (Smartink). Manuf. Lett. 24, 14–18 (2020).

Liou, T.-M., Chan, C.-Y. & Shih, K.-C. Effects of actuating waveform, ink property, and nozzle size on piezoelectrically driven inkjet droplets. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 8(5), 575–586 (2010).

Wang, T., Lin, J., Lei, Y., Guo, X. & Fu, H. Droplets generator: Formation and control of main and satellite droplets. Colloids Surf. A 558, 303–312 (2018).

Self, R., and Wallace, D. Method of drop size modulation with extended transition time waveform, USA,to MicroFab Tech, Inc. Plano, Tex, (2000).

Shin, P., and Sung, J. The effect of driving waveforms on droplet formation in a piezoelectric inkjet nozzle. In: Electronics Packaging Technology Conference, 2009. EPTC’09. 11th, Conference Proceedings, IEEE, pp. 158–162.

Liu, Y.-F., Tsai, M.-H., Pai, Y.-F. & Hwang, W.-S. Control of droplet formation by operating waveform for inks with various viscosities in piezoelectric inkjet printing. Appl. Phys. A 111(2), 509–516 (2013).

Khalate, A. A., Bombois, X., Babuška, R., Wijshoff, H. & Waarsing, R. Performance improvement of a drop-on-demand inkjet printhead using an optimization-based feedforward control method. Control. Eng. Pract. 19(8), 771–781 (2011).

Khalate, A. A. et al. A waveform design method for a piezo inkjet printhead based on robust feedforward control. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 21(6), 1365–1374 (2012).

Ezzeldin, M., van den Bosch, P. & Weiland, S. Experimental-based feedforward control for a DoD inkjet printhead. Control. Eng. Pract. 21(7), 940–952 (2013).

Yang, Z. et al. Actuation waveform optimization via multi-pulse crosstalk modulation for stable ultra-high frequency piezoelectric drop-on-demand printing. Addit. Manuf. 60, 103165 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Waveform design method for piezoelectric print-head based on iterative learning and equivalent circuit model. Micromachines 14(4), 768 (2023).

Miers, J. C. & Zhou, W. Droplet formation at megahertz frequency. AIChE J. 63(6), 2367–2377 (2017).

Sui, C. & Zhou, W. Modelling of the effects of driving signal parameters on the droplet formation dynamics in piezoelectric inkjet. Chem. Eng. Sci. 301, 120677 (2024).

Antonopoulou, E., Harlen, O., Walkley, M. & Kapur, N. Jetting behavior in drop-on-demand printing: Laboratory experiments and numerical simulations. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5(4), 043603 (2020).

Jang, D., Kim, D. & Moon, J. Influence of fluid physical properties on ink-jet printability. Langmuir 25(5), 2629–2635 (2009).

Zhang, H., Moon, S. K. & Ngo, T. H. 3D printed electronics of non-contact ink writing techniques: status and promise. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 7(2), 511–524 (2020).

Hoath, S., Jung, S. & Hutchings, I. A simple criterion for filament break-up in drop-on-demand inkjet printing. Phys. Fluids 25(2), 021701 (2013).

Castrejón-Pita, A. A., Castrejon-Pita, J. R. & Hutchings, I. M. Breakup of liquid filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108(7), 074506 (2012).

Liu, Y. & Derby, B. Experimental study of the parameters for stable drop-on-demand inkjet performance. Phys. Fluids 31(3), 032004 (2019).

Chang, J., Jiang, F., Liu, Z., Zhu, D. & Shen, T. Simulation and experimental study on droplet breakup modes and redrawing of their phase diagram. Phys. Fluids 33(8), 082105 (2021).

Yun, J. et al. Droplet property optimization in printable electronics fabrication using root system growth algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 125, 592–603 (2018).

Wu, H.-C., Shan, T.-R., Hwang, W.-S. & Lin, H.-J. Study of micro-droplet behavior for a piezoelectric inkjet printing device using a single pulse voltage pattern. Mater. Trans. 45(5), 1794–1801 (2004).

Oktavianty, O., Kyotani, T., Haruyama, S. & Kaminishi, K. New actuation waveform design of DoD inkjet printer for single and multi-drop ejection method. Addit. Manuf. 25, 522–531 (2019).

Tsai, M. H., Hwang, W.-S., Chou, H. H. & Hsieh, P. H. Effects of pulse voltage on inkjet printing of a silver nanopowder suspension. Nanotechnology 19(33), 335304 (2008).

Dong, H. Drop-on-Demand Inkjet Drop Formation and Deposition. Georgia Institute of Technology, (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our colleagues at the AM3 Lab for providing support and enabling environment for this work. We extend our gratitude to the University of Arkansas for its financial support, facilitated through the startup funding granted by the Vice Provost Office. The results, finding, conclusions, and recommendations articulated in this paper are exclusively those of the authors and do not necessarily align with the perspectives of the University of Arkansas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chao Sui: conducted the experiments, performed data analysis, prepared the figures, and drafted the manuscript; Wenchao Zhou: guidance on research design, secured funding and resources, supervised the project, and contributed to the critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. Both authors discussed the results and contributed to the overall interpretation and presentation of the findings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sui, C., Zhou, W. Optimizing driving waveforms to enhance inkjet printing speed. Sci Rep 15, 38358 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22254-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22254-1