Abstract

The valorization of potato peel byproducts, comprising approximately 14–40% of the total weight of fresh potatoes, through the extraction of cellulose nanofibers and their integration into starch-based biocomposites presents a sustainable strategy for enhancing the properties of biodegradable films for packaging applications. This study evaluated the physicochemical, barrier and mechanical properties of thermoplastic starch films incorporating cellulose nanofibers from potato peels (NCPP) at different concentrations (5%, 10%, and 15%). The addition of NCPP significantly increased the crystallinity index, with TPS-NCPP15 exhibiting the highest crystallinity (7.41%). Mechanical properties were significantly improved: Young’s modulus increased from 1.31 ± 0.09 MPa in TPS to 7.54 ± 0.82 MPa in TPS-NCPP5, and further to 12.40 ± 0.09 MPa and 14.45 ± 0.07 MPa in TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15, respectively. Tensile strength rose from 21.11 ± 3.42 MPa in TPS to 35.60 ± 3.04 MPa in TPS-NCPP5, and to 50.69 ± 0.42 MPa and 55.22 ± 0.09 MPa in TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15. NCPP-reinforced films exhibited lower water contact angles than the control, indicating greater surface wettability. Water vapor permeability was reduced from 6.37 × 10⁻¹⁰ g·s⁻¹·m⁻¹·Pa⁻¹ in the control film to 3.55 × 10⁻¹⁰ g·s⁻¹·m⁻¹·Pa⁻¹ and 4.54 × 10⁻¹⁰ g·s⁻¹·m⁻¹·Pa⁻¹ in TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15, respectively, indicating enhanced moisture barrier properties. The swelling capacity of the films was significantly enhanced with the addition of cellulose, with a more pronounced effect at 5% than at 10% and 15%. The films remained visually transparent, except at the highest cellulose concentration, where opacity increased. These findings highlight the potential of NCPP as a sustainable reinforcement material in biodegradable packaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum) are one of the most significant food crops globally, ranking as the fourth most cultivated crop after wheat, rice, and maize1. They are a staple food in many countries, providing essential carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals that contribute to food security and nutrition1,2,3. In addition to their nutritional value, potatoes also play a crucial role in the farming, family, and community agriculture, enhancing livelihoods and supporting local economies4,5.

Potato tubers are composed of several parts, including the flesh (or pulp), which is the primary edible portion, and the peels, which are often discarded but contain significant nutritional and bioactive compounds6. Studies have shown that the peel can account for approximately 14–40% of the total weight of fresh potatoes, depending on the variety and size of the tuber and the peeling method1,6. This biomass, often considered agro-industrial waste, represents a substantial opportunity for valorization.

Based on data reported for various cultivars, potato peels typically contain 68–88% carbohydrates, 2–17% protein, 4–22% dietary fiber, 0.5–2.6% fat, and 0.9–9.1% ash on a dry weight basis3. Besides, potato peels are rich in phenolic compounds, and other bioactive substances that can be repurposed for various applications, including food formulations, packaging, animal feed, and the extraction of valuable compounds7,8.

Potato peels are also known to contain a significant amount of cellulose (∼2.5%), hemicellulose (∼34.7%) and lignin (∼3.8%), which could be isolated for potential applications in biocomposites and other materials1,9,10. Some studies have focused on extracting cellulose nanofibers from potato peels using different methods, obtaining materials with desirable properties, such as high aspect ratio and good mechanical strength11,12.

Polysaccharides are promising candidates for the development of sustainable packaging due to their natural abundance, biodegradability, and minimal environmental footprint13. Among these, starch stands out as a cost-effective and versatile option for film production14. However, starch-based films often suffer from limitations such as weak mechanical strength, high moisture sensitivity, and structural changes over time due to retrogradation and crystallization13. To address these challenges, various strategies have been explored, including the incorporation of micro- and nanoscale reinforcements13,15. In this context, cellulose extracted from diverse plant sources and agro-industrial byproducts has gained attention as an eco-friendly filler due to its availability, low cost, and potential to enhance film performance13,16,17. However, the performance of starch–cellulose composites depend critically on the cellulose source and its extraction method, as differences in morphology, crystallinity, and residual components (such as hemicellulose or lignin) influence compatibility and reinforcement efficiency18,19,20,21,22. Besides, the processing methods and the technique of cellulose incorporation play crucial roles in achieving uniform films with optimized mechanical and barrier properties23. Therefore, assessing cellulose nanofibers obtained specifically from potato peel by-products is important, since their structural and functional features may differ from those of other reported cellulose nanofibers22. Such an evaluation can clarify whether potato peel-derived nanocellulose confers distinctive or comparable effects relative to cellulose nanofibers from other botanical sources.

Several works have studied the effect of the incorporation of cellulose nanomaterials into starch nanocomposites13. Daza-Orsini et al.15 reported that incorporating taro peel-derived cellulose nanofibers into taro starch films improved mechanical properties, decreased water vapor permeability, and increased opacity and water swelling of the films. Siriwong et al.17 obtained cellulose nanofibers from sugarcane bagasse using alkaline treatments and incorporated them into modified starch matrices. The addition of cellulose nanofibers improved the films’ mechanical properties, thermal stability, and moisture resistance, with the best performance observed at higher NaOH concentrations due to stronger filler–matrix interactions. Nandi et al.16 analyzed the incorporation of cellulose nanocrystals extracted from betel leaf petioles into potato starch–guar gum films. The nanocrystals, obtained via sulfuric acid hydrolysis, significantly enhanced the films’ tensile strength, elongation at break, and barrier properties, while exhibiting good compatibility with the polymer matrix.

The present study aims to extract cellulose nanofibers from potato peel waste and evaluate their effectiveness as reinforcing agents in starch-based nanocomposites. By systematically assessing the physicochemical properties and structural performance of these nanocomposites, this research contributes to the ongoing development of sustainable and biodegradable materials. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have specifically addressed the use of potato peel-derived cellulose nanofibers in potato starch matrices. This approach provides a consistent botanical origin for both the polymer and the reinforcement, while valorizing an abundant agro-industrial by-product.

Materials and methods

Potato starch isolation

Potato starch (Amylose content: 18.55 ± 1.3%) was extracted from tubers (Solanum tuberosum L.) following previously established protocols by Medina-Jaramillo et al.24 Briefly, cleaned and peeled tubers were mashed, mixed with water (1:2 w/w), and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. The slurry was filtered, and the starch was separated by decantation, dried at 40 °C (< 12% moisture), and milled.

Extraction of cellulose nanofibers from potato peels

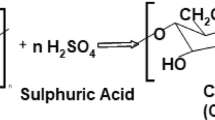

Cellulose nanofibers from potato peels (NCPP) were obtained as described in prior studies25,26. Briefly, peels were washed, dried (100 °C, 24 h), ground, and sieved. The resulting material was then treated with a 5 wt% KOH solution for 14 h under continuous stirring at ambient temperature.

The insoluble fraction was subjected to delignification using a 1 wt% NaClO₂ solution adjusted to pH 5.0 and heated to 70 °C for 1 h. This was followed by a second KOH treatment (5 wt%) and a subsequent acid hydrolysis using 1 wt% H₂SO₄ solution for 2 h. After each chemical step, the solid residues were thoroughly washed with distilled water until a neutral pH was attained. Finally, the cellulose fibers were mechanically refined using an ultrafine friction grinder (Masuko Sangyo, Supermasscolloider, Tokyo, Japan), with the disc gap set to −1. This process yielded nanofibers with an average diameter of 64.73 ± 14.50 nm, as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 1).

Preparation of the films

Starch-based films, with and without NCPP, were fabricated by casting as informed in previous works27,28. Films without NCPP (TPS) were prepared based on starch (2 g/100 mL), glycerol (0.6 g/100 mL), and water (97.4 g/100 mL). Nanocomposite films replaced water (5, 10, or 15 g) with an equivalent NCPP aqueous suspension (2 wt%). NCPP concentrations were chosen based on literature reports and preliminary trials, which showed that lower levels (below 5%) produced negligible effects, while higher loadings (above 15%) led to processing difficulties and excessive fiber agglomeration15,29.

Mixtures were stirred at 250 rpm for 40 min and heated until 82 ◦C with continuous stirring. All film-forming suspensions were homogenized at 18,000 rpm for 5 min (Ultra Turrax T25, IKA® WERKE, Germany), degassed with a vacuum system, and dried into polypropylene boxes at 50 °C for 24 h. The obtained films were maintained into desiccators conditioned at 57% of relative humidity for 24 h at room temperature.

The nanocomposites added of 5, 10–15 g/100 mL of NCPP aqueous suspension will be referred as “TPS-NCPP5”, “TPS-NCPP10” and “TPS-NCPP15”, respectively.

Films characterization

Morphological analysis

Surface and cross-sectional micrographs of the films were acquired using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6390LV, JEOL, Japan)30. Prior to observation, the specimens were cryofractured by immersion in liquid nitrogen. The fractured samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs and coated with a gold layer using a sputtering system. SEM imaging was carried out under an accelerating voltage of approximately 15 kV.

Infrared spectroscopy analysis

The spectra of the films were recorded using a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (Spectrum Two, Perkin Elmer, USA) equipped with an Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) module. Each spectrum was obtained by averaging 64 scans in the range of 4000 to 550 cm⁻¹, with a spectral resolution of 4 cm⁻¹31.

X-ray diffraction analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the films were obtained using a Rigaku MiniFlex600 diffractometer (Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a CuKα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å) and operated at 40 kV and 15 mA. Scans were conducted over a 2θ range of 5° to 45°, at a scanning rate of 5°/min. The relative crystallinity (RC) was calculated as the ratio of the area under the crystalline peaks to the total area (crystalline plus amorphous regions)32,33.

Thickness and water contact angle

Thickness was determined with a micrometer (Mitutoyo, Japan), which has an accuracy of ± 0.03 mm. The water contact angle of the films was measured using an optical tensiometer (RaméHart 250, USA), following the method reported by Valecia et al.27. A droplet of distilled water was carefully placed on the surface of the samples, and the contact angle formed between the tangent of the drop and the film surface was recorded. The measurements were analyzed using the DROPimage Advanced software34.

Water vapor permeability

Water vapor permeability (WVP) of the films was evaluated at room temperature according to the ASTM E96/E96M-16 standard method15. Film samples were sealed over a circular opening of 4 × 10⁻⁴ m² in a permeation cell containing anhydrous calcium chloride as the desiccant. The assembled cells were then placed in desiccators maintained at 75% relative humidity (RH) using a saturated sodium chloride solution to generate a controlled vapor pressure gradient. The weight of each cell was recorded every 24 h using an analytical balance with a precision of 0.0001 g. The increase in weight, corresponding to water vapor transmission through the film, was plotted as a function of time. The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) was determined from the slope of the resulting linear plot (g/s) normalized by the exposed area (m²). Finally, WVP (g·Pa⁻¹·s⁻¹·m⁻¹) was calculated using the following equation:

where WVTR is the water vapor transmission rate (g·s⁻¹·m⁻²), P is the saturation vapor pressure of water (Pa), RH is the relative humidity (expressed as a fraction), and d is the film thickness (m).

Moisture content, swelling and water solubility

The moisture content of the films was determined gravimetrically by drying pre-weighed samples in an oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. The moisture content (%) was calculated based on the weight loss during drying relative to the initial weight of the sample.

The swelling of the films was evaluated by immersing pre-weighed samples in distilled water (pH 6.0) at room temperature (22–25 °C) for 24 h. After immersion, the excess surface water was gently removed, and the samples were weighed to determine the water uptake. Subsequently, the films were oven-dried at 105 °C until constant weight to calculate the solubility, expressed as the percentage of mass lost relative to the initial dry weight.

Opacity and UV light transmittance

Film opacity was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (HITACHI U-1900, Japan). Samples were placed in the instrument’s sample holder to allow light to pass through them. Absorbance was recorded at 600 nm, and opacity was reported as absorbance units normalized by film thickness (a.u./mm).

The transmittance of UV light through the films was evaluated using the same UV–Vis spectrophotometer (HITACHI U-1900, Japan). Film samples were positioned in a quartz cuvette, and the percentage of transmitted light was recorded at a wavelength of 280 nm.

Tensile properties

Mechanical properties, including Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break, were determined in accordance with ASTM D882-1215. The tests were performed using a Brookfield CTX texture analyzer (Brookfield Engineering Lab, Inc., Middleboro, MA, USA) equipped with a 10 kg load cell. The measurements were conducted at a constant deformation rate of 5 mm/min. The film samples were prepared in strips measuring 40 mm in length, 5 mm in width, and approximately 0.14 mm in thickness. The mechanical parameters were derived from the stress–strain curves obtained during testing.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s test (95% confidence) in Minitab v.16 (PA, USA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation from triplicate experiments.

Results and discussion

Film morphology

The incorporation of cellulose into thermoplastic starch films caused changes in their morphological characteristics (Fig. 2). TPS films exhibits a smooth surface indicative of a homogeneous matrix (Fig. 2a). In contrast, films containing NCPP (TPS-NCPP5, TPS-NCPP10, and TPS-NCPP15) showed a rougher surface appearance with visible nanofibers agglomerates embedded within the starch matrix (Fig. 2b-d). This observation aligns with findings from previous studies that have reported similar morphological changes in nanocomposites incorporating cellulose reinforcements35,36. The cross-sectional SEM images of films without cellulose (Fig. 2e) and those containing 5% and 10% cellulose (Fig. 2f-g) reveal the presence of cracks. These cracks suggest that the cohesion within the starch matrix is compromised37. However, films with 15% cellulose demonstrate a marked reduction in crack formation, indicating improved interaction and compatibility between the starch and cellulose components (Fig. 2h). This behavior could be attributed to the increased cellulose content, which facilitates the formation of multiscale interactions between cellulose and the starch molecules. Such interactions promote a more integrated and stable film structure, thereby reducing the occurrence of cracks35,36.

SEM images of potato starch films without cellulose nanofibers (TPS) and with cellulose nanofibers from potato peels (NCPP) at 5% (TPS-NCPP5), 10% (TPS-NCPP10), and 15% (TPS-NCPP15). For each film, the top image (a–d) shows the surface and the bottom image (e–h) shows the cross-section, corresponding respectively to TPS (a, e), TPS-NCPP5 (b, f), TPS-NCPP10 (c, g), and TPS-NCPP15 (d, h).

FTIR and XRD analysis

ATR-FTIR spectra of the films showed characteristic absorption bands of starch and cellulose (Fig. 3). The broad band at 3280 cm⁻¹ corresponds to O–H stretching vibrations. The peak at 2923 cm⁻¹ is attributed to C–H stretching. The band at 1154 cm⁻¹ is associated with C–O–C asymmetric stretching, characteristic of glycosidic linkages in polysaccharides (Fig. 3)38. Additional bands at 1080 cm⁻¹, 996 cm⁻¹, and 928 cm⁻¹ correspond to C–O and C–C stretching vibrations33. Peaks at 1647 cm⁻¹ (O–H vending), 1422 cm⁻¹ (CH₂ scissoring) and 1324 cm−1 (C–H or O–H bending) were also detected and are typical of starch and NCPP31,39. The peak at 852 cm⁻¹ is attributed to – C–H bending.

Besides, the spectra showed some changes in peak intensity and bandwidth. In particular, the O–H stretching band (~ 3280 cm⁻¹) decreased in intensity as NCPP concentration increased, reflecting stronger hydrogen bonding interactions between starch and cellulose nanofibers40. The C–H stretching band (~ 2923 cm⁻¹) also showed a progressive reduction in intensity, suggesting rearrangements in the starch backbone upon reinforcement. Furthermore, slight sharpening in the 1154–928 cm⁻¹ region indicates a more compact network at higher NCPP loadings40.

Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffractograms of potato starch films without NCPP (TPS) and with NCPP at 5% (TPS-NCPP5), 10% (TPS-NCPP10), and 15% (TPS-NCPP15). TPS films exhibited a typical halo centered at 2θ ≈ 23.9º (3.72 Å), confirming complete starch gelatinization during film preparation. With the incorporation of NCPP, additional peaks appeared at 2θ ≈ 5.4º (16.35 Å), 17.3º (5.47 Å), and 21.6º (4.11 Å), together with well-defined peaks above 30º, which are characteristic of the crystalline domains of cellulose nanofibers41,42.

The incorporation of cellulose nanofibers into starch films resulted in a significant increase in the crystallinity index of the composite materials. While the thermoplastic starch (TPS) films were predominantly amorphous, the TPS-NCPP5, TPS-NCPP10, and TPS-NCPP15 films exhibited crystallinity percentages of 2.25%, 4.72%, and 7.41%, respectively. Because the broad starch halo partially overlaps with the main cellulose reflection at ~ 22°, the cellulose contribution is less apparent at lower nanofiber loadings but becomes progressively more discernible as the concentration increases. This trend indicates that the higher crystallinity values mainly reflect the increasing proportion of the more ordered cellulose phase within the composite43,44.

Visual appearance, thickness and surface hydrophilicity

Figure 5 shows the visual appearance of the films, both with and without NCPP. All films exhibited a uniform appearance, free from folds, wrinkles, or other defects.

On the other hand, the incorporation of cellulose nanofibers did not influence the thickness of the starch films, with all samples exhibiting a thickness of approximately 0.14 mm (Table 1).

The water contact angle (WCA) values of the films varied significantly depending on the concentration of cellulose nanofibers (Table 1). All films exhibited hydrophilic behavior, with WCA values below 90°. Besides, films containing cellulose showed significantly lower contact angles than those without nanocellulose, suggesting that cellulose enhances surface wettability. This effect could be attributed to the increase in surface roughness introduced by the incorporation of cellulose nanofibers. The rougher surface topography, as observed in SEM images (Fig. 2), promotes greater water spreading on the film surface. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies, where the addition of microfibrillated or nanofibrillated cellulose led to increased surface rugosity and, consequently, decreased water contact angles in starch-based composite films35.

Water vapor barrier properties

Table 2 shows the water vapor permeability (WVP) of the starch-based films with and without NPCC. Films containing 5% cellulose (TPS-NCPP5) exhibited WVP values similar to control ones (TPS), indicating that a low concentration of cellulose does not substantially alter the water barrier properties of the films. However, films with 10% and 15% NCPP (TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15) showed lower WVP values than control and TPS-NCPP5 films, with reductions of approximately 44% and 29%, respectively. These findings align with the observed increase in crystallinity associated with the addition of cellulose, as previously discussed. The enhanced crystallinity contributes to a more ordered structure within the films, which effectively restricts the movement of water molecules through the matrix45,46.

Moisture content, swelling, and water solubility

Table 2 shows the moisture content, swelling, and water solubility of potato starch films without cellulose nanofibers (TPS) and with cellulose nanofibers from potato peels (NCPP) at 5% (TPS-NCPP5), 10% (TPS-NCPP10) and 15% (TPS-NCPP15).

TPS-NCPP5 and TPS-NCPP10 exhibited lower moisture levels compared to the TPS films, whereas films with 15% cellulose displayed moisture levels comparable to the control, suggesting that at higher concentrations, the hydrophilic interactions between the NCPP and water may dominate, leading to increased moisture retention45.

The incorporation of cellulose nanofibers significantly affected the swelling behavior of the starch-based films (p < 0.05) (Table 2). TPS films showed the lowest swelling capacity, while TPS-NCPP5 showed the highest swelling capacity, significantly higher than all other formulations (p < 0.05). As the NCPP content increased from 5% to 15%, a progressive decrease in swelling was observed. Films with 10% NCPP (TPS-NCPP10) and 15% NCPP (TPS-NCPP15) exhibited intermediate swelling values, both significantly different from each other and from the 5% NCPP films. This reduction in swelling with higher NCPP content may be attributed to the formation of a more compact and interconnected network at increased fiber concentrations, which restricts water penetration.

Overall, these results suggest that at lower NCPP concentrations (5%), the fibers are more homogeneously dispersed within the starch matrix, facilitating water uptake and promoting film expansion37. In contrast, higher NCPP contents (10% and 15%) likely lead to fiber agglomeration and the formation of denser microstructures, thereby reducing the films’ swelling capacity.

On the other hand, films with 5% and 15% NCPP (TPS-NCPP5 and TPS-NCPP15) showed significantly lower solubility than the control, whereas TPS-NCPP10 did not differ significantly (p < 0.05) (Table 2). This behavior can be attributed to the increased crystallinity of the composite films, as crystalline regions are less accessible to solvent molecules compared to the more soluble amorphous regions. As a result, the observed decrease in water solubility can be explained by the greater presence of crystalline structures, which reduce the interaction between the solvent and the matrix.

Optical properties

The incorporation of cellulose nanofibers significantly influenced the optical properties of the starch-based films (p < 0.05) (Table 3). TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15 films showed higher opacity compared to TPS, whereas TPS-NCPP5 films showed intermediate opacity values. The increase in opacity was attributed to light-scattering effects caused by the presence of NCPP agglomerates, as confirmed by SEM micrographs (Fig. 2). These micrometric structures disrupt light transmission through the matrix, leading to greater scattering and reduced transparency. Consequently, TPS-NCPP15 films exceeded the threshold typically considered transparent (opacity < 5 a.u./mm)47.

Similarly, UV-light transmittance at 280 nm significantly decreased with increasing NCPP content (p < 0.05). The TPS films exhibited the highest transmittance, whereas TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15 films showed lower values (Table 3). The TPS-NCPP5 film showed intermediate transmittance, differing significantly from both the control and the higher NCPP concentrations. These results are consistent with those reported by Csiszár et al., who observed that the reduction in transparency of starch–nanocellulose composites was primarily due to the formation of nanocellulose aggregates, which act as light-scattering centers rather than UV absorbers48.

Uniaxial tensile properties

The incorporation of NCPP into starch films significantly influenced their mechanical properties (Table 4; Fig. 6). TPS-NCPP5 films exhibited a significant 475% increase in Young’s modulus compared to the control sample, whereas the formulations TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15 demonstrated even more substantial improvements, with increases of 924%. In addition to the improvements in Young’s modulus, the presence of cellulose also significantly enhanced the tensile strength of the films (Table 4; Fig. 6). TPS-NCPP5 samples showed an approximate increase of 68% in tensile strength compared to the control, while TPS-NCPP10 and TPS-NCPP15 exhibited even greater enhancements, with increases of 149%. However, the elongation at break for all cellulose-containing films was lower than that of the TPS sample, indicating a reduction in flexibility36,49.

Overall, the mechanical behavior of the films aligns with the X-ray diffraction results, which indicated an increase in the crystallinity index of the starch films containing NCPP. The strong hydrogen bonding interactions between cellulose and starch contribute to increased stiffness and tensile strength while reducing flexibility36,49. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting similar trends, where cellulose reinforcement led to higher tensile strength and Young’s modulus, along with decreased elongation at break in nanocomposites35,36.

Table 5 provides a comparative overview of the performance of potato peel–derived cellulose nanofiber composites with those reported for starch films reinforced with cellulose from other sources (taro peel, sugarcane bagasse, and betel leaf petioles). Previous studies highlight that the reinforcement effect of cellulose depends on its source, extraction process, and morphological features, which results in different balances of mechanical, barrier, and optical properties (Table 5). For instance, sugarcane bagasse nanofibers improve tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break in cassava starch films, with moisture barrier improvements at higher loadings50. Betel leaf nanocrystals enhance tensile strength, elongation, and UV resistance in potato–guar gum films at low concentrations16. Taro peel nanofibers increase tensile strength and modulus and reduce WVP at moderate contents, but higher loadings lead to increased permeability15,51.

In contrast, potato peel cellulose nanofibers obtained in this work enhanced Young’s modulus and tensile strength and reduced water vapor permeability by ≈ 44% at 10% loading. This balance of reinforcement and barrier improvement distinguishes potato peel cellulose nanofibers from other cellulose sources.

Conclusions

The incorporation of cellulose nanofibers extracted from potato peels into starch-based films enhanced their structural, barrier, mechanical, and optical properties in a concentration-dependent manner. Among the tested formulations, TPS-NCPP10 exhibited the most balanced performance, combining significant improvements in Young’s modulus and tensile strength with a ≈ 44% reduction in water vapor permeability, while maintaining visual transparency. At 15% loading, additional reinforcement was achieved, although transparency was compromised due to fiber agglomeration. All films remained hydrophilic, with wettability increasing at higher nanofiber concentrations. These improvements were attributed to hydrogen bonding, interfacial interactions, and physical entanglement between starch chains and nanocellulose.

Overall, potato peel–derived nanocellulose demonstrated potential as a sustainable reinforcement for starch films, providing a distinctive combination of mechanical strength, barrier enhancement, and optical preservation particularly relevant for biodegradable packaging applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ijaz, N. et al. Valorization of potato peel: a sustainable eco-friendly approach. CYTA - Journal of Food 22, 1-10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/19476337.2024.2306951

Chauhan, A. et al. A review on waste valorization, biotechnological utilization, and management of potato. Food Sci Nutr 11, 5773–5785 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3546

Vescovo, D. et al. The valorization of potato peels as a functional ingredient in the food industry: A comprehensive review. Foods 14, 1333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14081333

Saini, R., Kaur, S., Aggarwal, P., Dhiman, A. & Suthar, P. Conventional and emerging innovative processing technologies for quality processing of potato and potato-based products: A review. Food Control. 153, 109933 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2023.109933.

Devaux, A., Kromann, P. & Ortiz, O. Potatoes for sustainable global food security. Potato Res. 57, 185–199 (2014).

Kot, A. M. et al. Biotechnological Methods of Management and Utilization of Potato Industry Waste—a Review. Potato Res 63, 431–447 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-019-09449-6

Sampaio, S. L. et al. Potato peels as sources of functional compounds for the food industry: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 103, 118–129 (2020).

Khanal, S. et al. Sustainable utilization and valorization of potato waste: state of the art, challenges, and perspectives. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 23335–23360 (2024).

Tawila, M. A., Omer, H. A. A. & Gad, S. M. Partial replacing of concentrate feed mixture by potato processing waste in sheep rations. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 4, 156–164 (2008).

Liang, S. & McDonald, A. G. Chemical and thermal characterization of potato Peel waste and its fermentation residue as potential resources for biofuel and bioproducts production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 8421–8429 (2014).

Liu, X., Sun, H., Mu, T., Fauconnier, M. L. & Li, M. Preparation of cellulose nanofibers from potato residues by ultrasonication combined with high-pressure homogenization. Food Chem. 413, 135675 (2023).

Sadeghi-Shapourabadi, M., Elkoun, S. & Robert, M. Microwave-Assisted chemical purification and ultrasonication for extraction of Nano-Fibrillated cellulose from potato Peel waste. Macromol 3, 766–781 (2023).

Sabapathy, P. C. et al. Recent improvements in starch films with cellulose and its derivatives–A review. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 105920 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2024.105920 (2024).

Zhu, F. Starch based films and coatings for food packaging: interactions with phenolic compounds. Food Res. Int. 204, 115758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2025.115758.

Daza-Orsini, S. M., Medina-Jaramillo, C., Caicedo-Chacon, W. D., Ayala-Valencia, G. & López-Córdoba, A. Isolation of Taro Peel cellulose nanofibers and its application in improving functional properties of Taro starch nanocomposites films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 273, 132951 (2024).

Nandi, S., Nayak, P. P. & Guha, P. Valorization of betel leaf industry waste: extraction of cellulose nanocrystals and their compatibility with starch-based composite films. Biomass Bioenergy. 194, 107678 (2025).

Siriwong, C., Sae-oui, P., Chuengan, S., Ruanna, M. & Siriwong, K. Cellulose nanofibers from sugarcane Bagasse and their application in starch-based packaging films. Polym. Compos. 45, 15689–15703 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Effects of different sources of cellulose on mechanical and barrier properties of thermoplastic sweet potato starch films. Ind. Crops Prod. 194, 116358 (2023).

Kontturi, K. S. et al. Influence of biological origin on the tensile properties of cellulose nanopapers. Cellulose 28, 6619–6628 (2021).

Kashcheyeva, E. I. et al. Properties and hydrolysis behavior of celluloses of different origin. Polymers (Basel) 14, 3899 (2022).

Wang, T., McFarlane, H. E. & Persson, S. The impact of abiotic factors on cellulose synthesis. J Exp Bot 67, 543–552 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv488

Fang, Q., Sun, H. N., Zhang, M., Mu, T. H. & Garcia-Vaquero, M. Cellulose nanofibers: current status and emerging development of Sources, Pretreatment, Production, and applications. ACS Agricultural Sci. Technol. 5, 3–27 (2025).

Montoya, Ú., Zuluaga, R., Castro, C., Goyanes, S. & Gañán, P. Development of composite films based on thermoplastic starch and cellulose microfibrils from Colombian agroindustrial wastes. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 27, 413–426 (2014).

Medina-Jaramillo, C., Estevez-Areco, S., Goyanes, S. & López-Córdoba, A. Characterization of starches isolated from Colombian native potatoes and their application as novel edible coatings for wild Andean blueberries (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz). Polymers (Basel) 11, 1937 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11121937

Zuluaga, R. et al. Cellulose microfibrils from banana rachis: effect of alkaline treatments on structural and morphological features. Carbohydr. Polym. 76, 51–59 (2009).

Medina-Jaramillo, C., Quintero-Pimiento, C., Gómez-Hoyos, C., Zuluaga-Gallego, R. & López-Córdoba, A. Alginate-edible coatings for application on wild Andean blueberries (Vaccinium meridionale swartz): effect of the addition of nanofibrils isolated from cocoa by-products. Polymers (Basel) 12, 824 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12040824

Piñeros-Hernandez, D., Medina-Jaramillo, C., López-Córdoba, A. & Goyanes, S. Edible cassava starch films carrying Rosemary antioxidant extracts for potential use as active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll 63, 488-495 (2017).

López-Córdoba, A., Medina-Jaramillo, C., Piñeros-Hernandez, D. & Goyanes, S. Cassava starch films containing Rosemary nanoparticles produced by solvent displacement method. Food Hydrocoll. 71, 26–34 (2017).

Jeevahan, J., Chandrasekaran, M. & Sethu, A. Influence of nanocellulose addition on the film properties of the bionanocomposite edible films prepared from maize, rice, wheat, and potato starches. in AIP Conf Proc American Institute of Physics Inc. 2162, 020073 (2019).https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5130283

dos Santos Alves, M. J. et al. Starch nanoparticles containing phenolic compounds from green propolis: characterization and evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and digestibility properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 255, 128079 (2024).

Leandro, G. C., Laroque, D. A., Carciofi, B. A. M. & Valencia, G. A. Development of a freshness indicator packaging system using cold atmospheric plasma on LLDPE–PVA with Laponite–anthocyanin biohybrid. Polym. Int. 73, 1001-1012 https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.6679 (2024).

Capello, C., Leandro, G. C., Gagliardi, T. R. & Valencia, G. A. Intelligent films from Chitosan and biohybrids based on anthocyanins and Laponite®: physicochemical properties and food packaging applications. J. Polym. Environ. 29, 3988–3999 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-021-02168-5 (2021).

Leandro, G. C., Cesca, K., Monteiro, A. R. & Valencia, G. A. Morphological and physicochemical properties of pine seed starch nanoparticles. Starch/Staerke 2200225, 1–7 (2023).

Valencia, G. A., Luciano, C. G., Lourenço, R. V. & Sobral, P. J. A. Microstructure and physical properties of nano-biocomposite films based on cassava starch and laponite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 107, 1576–1583 (2018).

Żołek-Tryznowska, Z., Bednarczyk, E., Tryznowski, M. & Kobiela, T. A comparative investigation of the surface properties of Corn-Starch-Microfibrillated cellulose composite films. Materials 16, 3320 (2023).

Lomelí-Ramírez, M. G. et al. Thermoplastic starch biocomposite films reinforced with nanocellulose from Agave Tequilana Weber var. Azul Bagasse. Polymers (Basel) 15, 3793 (2023).

Cakmak, H. & Dekker, M. Optimization of Cellulosic Fiber Extraction from Parsley Stalks and Utilization as Filler in Composite Biobased Films. Foods 11, 3932 (2022).

Koop, B. L., Zenin, E., Cesca, K., Valencia, G. A. & Monteiro, A. R. Intelligent labels manufactured by thermo-compression using starch and natural biohybrid based. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 220, 964–972 (2022).

Tibolla, H., Czaikoski, A., Pelissari, F. M., Menegalli, F. C. & Cunha, R. L. Starch-based nanocomposites with cellulose nanofibers obtained from chemical and mechanical treatments. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 161, 132–146 (2020).

Capello, C. et al. Preparation and characterization of colorimetric indicator films based on Chitosan/Polyvinyl alcohol and anthocyanins from Agri-Food wastes. J. Polym. Environ. 29, 1616–1629 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-020-01978-3(2021).

Hemida, M. H. et al. Cellulose nanocrystals from agricultural residues (Eichhornia crassipes): extraction and characterization. Heliyon 9, e16436 (2023).

Orrabalis, C. et al. Characterization of nanocellulose obtained from cereus Forbesii (a South American cactus). Mater. Res. 22, e20190243 (2020).

Marques, G. S. et al. Production and characterization of Starch-based films reinforced by Ramie nanofibers (< i > Boehmeria Nivea). J Appl. Polym. Sci 136, 47919 (2019).

Balakrishnan, P., Gopi, S., Sreekala, M. S. & Thomas, S. UV resistant transparent Bionanocomposite films based on potato Starch/Cellulose for sustainable packaging. Starch - Stärke 70, 1700139 (2017).

El Halal, S. L. M. et al. The properties of potato and cassava starch films combined with cellulose fibers and/or nanoclay. Starch - Stärke. 70, 1700115 (2018).

Costa, S. S., Druzian, J. I., Machado, B. A. S., de Souza, C. O. & Guimarães, A. G. Bi-Functional biobased packing of the cassava Starch, Glycerol, licuri nanocellulose and red propolis. PLoS One. 9, e112554 (2014).

Guzman-Puyol, S., Benítez, J. J. & Heredia-Guerrero J. A. Transparency of polymeric food packaging materials. Food Research International 161, 111792 (2022).

Csiszár, E., Kun, D. & Fekete, E. The role of structure and interactions in thermoplastic starch–nanocellulose composites. Polymers (Basel) 13, 3186 (2021).

Santana, J. S. et al. Cassava starch-based nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanofibers extracted from Sisal. J Appl. Polym. Sci 134, 44637 (2017).

Ribeiro, T. S. M. et al. Using cellulose nanofibril from sugarcane Bagasse as an Eco-Friendly ductile reinforcement in starch films for packaging. Sustainability (Switzerland) 17, 4128 (2025).

Daza-Orsini, S. M., Medina-Jaramillo, C. & López-Córdoba, A. Physicochemical characterization of starch and cellulose nanofibers extracted from Colocasia esculenta cultivated in the Colombian Caribbean. Polymers (Basel) 17, 2354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17172354

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) and to Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) for their financial support.

Funding

This research was funded by ICETEX and Minciencias through project 82561 “TUBERPRO: VALORIZACIÓN INTEGRAL DE RAICES Y TUBÉRCULOS PARA LA OBTENCIÓN DE BIOPOLÍMEROS, ALIMENTOS Y BIOPLÁSTICOS”, under Call 890–2020 “CONV. PARA EL FORTALECIMIENTO DE CTeI EN INST. DE EDUCACIÓN SUPERIOR PÚBLICAS”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. M.-J.: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis. G. C. -L.: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis. G. A. -V.: Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. A. L. -C.: Writing – original draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Medina-Jaramillo, C., Coelho-Leandro, G., Ayala-Valencia, G. et al. Starch-based biocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanofibers from potato peel byproducts. Sci Rep 15, 38412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22303-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22303-9