Abstract

Long-term corticosteroid use, including dexamethasone, is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, leading to enhanced hepatic gluconeogenesis and peripheral insulin resistance. This study reveals that dexamethasone additionally acts as a potent inducer of the main intestinal glucose transporter, sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1). In differentiated human Caco-2/TC7 intestinal cell monolayers, dexamethasone dose-dependently increased glucose transport by upregulating SGLT1 mRNA despite a reduction in glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) mRNA. Dexamethasone similarly elevated SGLT1 expression in ileal enterocytes and induced GLUT2 mRNA in mice, supporting its role in enhancing intestinal glucose uptake. Given the extensive use of dexamethasone to treat COVID-19, we further assessed its impact on SARS-CoV-2 entry receptors in the intestine. Dexamethasone increased transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) mRNA expression while decreasing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) mRNA and protein levels, potentially exacerbating viral spread in the gut. Our findings suggest that dexamethasone promotes glucose absorption in the intestine, contributing to hyperglycaemia, and modulates expression of intestinal SARS-CoV-2 receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents used to treat various autoimmune disorders and inflammatory conditions1. Despite their broad clinical use, including the extensive use of dexamethasone to treat severely ill SARS-CoV-2 patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, their therapeutic efficacy is limited by a broad range of well-documented side effects, including impaired glucose tolerance and steroid-induced diabetes2. While the underlying cellular mechanisms for these effects remain incompletely understood, clinical studies suggest that increased hepatic glucose production, peripheral insulin resistance, and diminished insulin secretion are principal factors2,3. However, the role of the intestine, a central site of nutrient absorption and metabolic signalling, has received comparatively little attention.

Dexamethasone has been shown to modulate the expression and function of key glucose transporters (GLUTs), including GLUT1, GLUT2, GLUT4, GLUT5 and sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) in various tissues4,5,6. Animal studies show dexamethasone modulates intestinal glucose transporters SGLT1 and GLUT27,8,9, potentially enhancing gut glucose absorption and increasing plasma glucose levels10. In individuals with pre-existing metabolic dysfunction, such as obesity, insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes, steroid-induced increases in intestinal glucose uptake may further exacerbate hyperglycaemia. For example, dexamethasone administration increased blood glucose response in both healthy people and individuals with prediabetes, with the magnitude of increase in glucose area under the curve 13.5% higher in the latter11. Therefore, understanding how dexamethasone alters intestinal glucose transport under both healthy and inflammatory conditions is essential for predicting and managing steroid-associated metabolic complications.

Beyond glucose metabolism, the intestinal epithelium also serves as a primary site for SARS-CoV-2 viral entry, owing to its high expression of the viral entry receptors angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2)12. While dexamethasone is used to control systemic inflammation in critically ill COVID-19 patients, its effects on these entry receptors in the gut remain unclear. Importantly, ACE2 is not only a viral receptor but also plays a key role in modulating gut inflammation and glucose transporter expression via the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis13, suggesting a possible intersection between steroid therapy, inflammation, glucose metabolism, and viral susceptibility. Moreover, enhanced intestinal glucose absorption can impair glucose control, which may also contribute to poor prognosis in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Conflicting findings in animal studies, which report either increased, decreased, or unchanged transporter expression4,6,7,8, highlight the need for further research, as the effects in humans remain unknown. Moreover, the impact of dexamethasone on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the human gut remains unclear. Therefore, this study aims to investigate how dexamethasone affects glucose uptake, glucose transporter expression, and the expression of the viral entry receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the human intestinal epithelial cell model, Caco-2/TC7, under both normal and pro-inflammatory conditions. By integrating gene expression analysis, functional glucose transport assays, and comparison with in vivo transcriptomic data, this study provides new insights into the intestinal consequences of steroid therapy, especially relevant to patients with metabolic syndrome, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, and those receiving dexamethasone for COVID-19.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Caco-2/TC7 cells were a kind donation from Rousset Lab (U178 INSERM, Villejuif, France)14. Dexamethasone was purchased from Merck Life Science Pty Ltd (Bayswater, VIC, Australia) and dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 20 mM stock. Coomassie Plus Bradford assay kit, bovine serum albumin standard and all cell culture reagents, unless otherwise stated, were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Scoresby, VIC, Australia). High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA reverse transcription kits, and FAM- or VIC-labelled TaqMan primers for ACE2 (Hs01085333_m1), SGLT1 (Hs01573793_m1), GLUT2 (Hs01096908_m1), TMPRSS2 (Hs01122322_m1) and TBP (Hs00427620_m1) were also from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Human ACE2 (ab235649) ELISA kit was from Abcam Australia Pty Ltd. The human TMPRSS2 ELISA kit (NBP2-89171, manufactured by Novus Biologicals) was supplied by In Vitro Technologies (Noble Park North, VIC, Australia). Human IL-8 ELISA kits were procured from Abcam (ab100575) and EMD Millipore (IL-6 and IL-8 cytokine panel multiplex ELISA kit (HCYTMAG-60 K)) (Darmstadt, Germany). The Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit for RNA extraction from cells, the QX200 droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system, ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) and all other materials used for ddPCR were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (South Granville, NSW, Australia). Human IL-1β and TNF-α proteins and all cell culture vessels and other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Merck Life Science, unless specified otherwise. Heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) was used throughout the cell culture work and experiments, wherever FBS is stated. High-purity (18.2 MΩ/cm) milliQ water (Merck Life Science) was used throughout. All the chemicals and reagents used in the experiments were of the highest purity.

Culture of Caco-2/TC7 cells

The experiments were performed using the human colon carcinoma-derived Caco-2/TC7 cells as the intestinal model. The cells were cultured on 75 cm2 culture flasks, at a density of 0.2 × 105 cells/cm2, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) comprised of high glucose (4.5 g/L or 25 mM) and supplemented with 20% (v/v) FBS, 2% (v/v) nonessential amino acids, 2% (v/v) Glutamax and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin (final concentrations of 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin). Cells were subcultured upon reaching ~ 60% confluence, and were lifted from the flask using 0.25% (v/v) trypsin–EDTA solution. The cell culture medium was changed three times a week and cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2/90% air in an incubator at 37 °C. Cells were used in experiments between passages 32 and 40. A detailed report on Caco-2/TC7 culturing can be found in Barber et al.15.

Caco-2/TC7 cell monolayer differentiation

For differentiation, cells were seeded in the apical chamber of either 6-well or 12-well transwell plates with polyester filters, 0.4 µm pore size, 24 mm (6-well) or 12 mm (12-well) diameter, at a density of 0.1 × 105 cells/cm2 in complete DMEM medium (25 mM glucose) supplemented with 20% (v/v) FBS in both apical and basolateral compartments. Cells were examined under the microscope daily until they reached 100% confluence, and this was marked as day 0. Cells were differentiated in the same culture medium (complete DMEM containing 25 mM glucose and 20% (v/v) FBS) for the first 7 days, after which FBS-free medium was used in the apical compartment, while the basolateral side received either 10% (v/v) or 20% (v/v) FBS-containing medium, with 5.5 mM or 25 mM glucose, with regular media changes three times a week.

Transport of 2-deoxy-D-glucose across differentiated Caco-2/TC7 monolayers

Caco-2/TC7 cells were seeded and differentiated as described in Sections "Culture of Caco-2/TC7 cells" and "Caco-2/TC7 cell monolayer differentiation". The effect of dexamethasone on glucose transport was assessed by measuring transport of 2-deoxy-D-glucose (non-metabolisable analagoue used to measure glucose uptake specifically) across Caco-2/TC7 cells differentiated for 21 days, grown in either 5.5 mM glucose- (normal glucose) or 25 mM glucose-containing (high glucose) medium from day 7 of cell differentiation. On the basolateral side, 20% (v/v) FBS-containing DMEM media were used until day 14, after which 10% (v/v) FBS-containing media were utilised until day 20. During the last 24 h of the experiment, FBS-free 5.5 mM or 25 mM glucose-containing DMEM medium was used on both cell compartments. Dexamethasone was prepared (final concentrations of 5, 10 and 20 µM) for the experiment by adding appropriate volumes of the 20 mM stock to FBS-free 5.5 mM or 25 mM glucose-containing DMEM media. The dexamethasone doses were selected to resemble physiological conditions. All test samples and the DMSO vehicle control contained 0.1% (v/v) DMSO. Cells were treated with dexamethasone or DMSO (vehicle control) twice a day starting from day 19 (total treatment duration 60 h). On day 21, the cells were starved for 4 h using glucose- and FBS-free DMEM medium in the presence of dexamethasone or DMSO. After starvation, all media were removed. Fresh FBS- and glucose-free medium was added to the basolateral side, while fresh FBS- and glucose-free medium supplemented with 5.5 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose was added to the apical compartment, and the cells were incubated for 30 min. Immediately after 30 min, the apical and basolateral media were collected, snap-frozen and stored at − 80 °C for quantitative analysis of 2-deoxy-D-glucose later. The media samples were thawed and processed by thorough mixing with acetonitrile (1:1 v/v) and subsequent centrifugation (17,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) to remove protein, and then diluted in milliQ water (1:9 v/v) before analysis. The concentrations of 2-deoxy-D-glucose in the apical and basolateral media were measured by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) using the same method we developed for the analysis of α-glucosidase enzyme assays previously15, with culture medium containing a range of 2-deoxy-D-glucose concentrations, prepared in the same way as the samples, used to produce a standard curve (Fig. 1A). The concentration of 2-deoxy-D-glucose transported into the basolateral side was reported, while the concentration of 2-deoxy-D-glucose remaining on the apical side was confirmed.

Dexamethasone enhances 2-deoxy-D-glucose transport in Caco-2/TC7 cells. (A) Schematic diagram detailing the experimental protocol used to culture Caco-2/TC7 cells, treat the cells with dexamethasone (DEX) and perform the glucose transport assay. Cells were differentiated for 21 days in either 5.5 mM glucose (normal) or 25 mM glucose (high) from day 7 of differentiation and were treated with dexamethasone or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (vehicle control) twice a day, starting from day 19, for 60 h. On day 21, the cells were starved for 4 h in glucose- and FBS-free medium in the presence of dexamethasone or DMSO, then incubated with 5.5 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) added to the apical (AP) compartment for 30 min. The apical and basolateral (BL) media were collected immediately and 2-deoxy-D-glucose was measured by HPAEC-PAD. The concentration of 2-deoxy-D-glucose transported into the basolateral compartment in cells differentiated in (B) 5.5 mM glucose and (C) 25 mM glucose, and (D) a comparison of 2-deoxy-D-glucose transport in cells differentiated in normal (grey) or high (red) glucose conditions. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences in B and C determined by one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test; differences between normal and high glucose in D determined by two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. A—created with BioRender.com (https://BioRender.com/g24b801); B-D—created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1. ns, not significant.

Treatment of Caco-2/TC7 cells with dexamethasone and/or cytokines

The effect of dexamethasone on the expression of our target genes and proteins was assessed using standard (without cytokine exposure) and pro-inflammatory (with 25 ng/mL IL-1β and 50 ng/mL TNF-α exposure) Caco-2/TC7 models. For this work, cells were differentiated for 14 days, with cells seeded and differentiated as described in Sections "Culture of Caco-2/TC7 cells" and "Caco-2/TC7 cell monolayer differentiation". Cells were cultured in a medium containing 25 mM glucose and 20% (v/v) FBS for the first 7 days of differentiation and then switched to a medium containing 5.5 mM glucose until day 14 (with 10% (v/v) FBS until day 13 and with FBS-free medium for the final 24 h). To reflect clinically relevant dosing, dexamethasone was used at concentrations below 20 µM. Dexamethasone was prepared (final concentrations of 5, 10 and 20 µM) by adding appropriate volumes of the 20 mM stock to FBS-free 5.5 mM glucose-containing medium. Dexamethasone was introduced to the apical compartment, and the cells were treated with dexamethasone (or 0.1% v/v DMSO vehicle control) for 4 h, 24 h or 60 h twice daily (from the morning of day 12 for the 60 h treatment, from the evening of day 13 for the 24 h treatment, or only 4 h before the end of the experiment, with all treatments finishing simultaneously on the evening of day 14). These time points were chosen to model both acute and chronic dexamethasone exposure and to capture temporal changes in gene expression and functional responses. For the inflamed model, cells were stimulated with a cytokine cocktail, containing 25 ng/mL IL-1β and 50 ng/mL TNF-α, with dosages based on previous studies using Caco-2 cells16,17, added once daily for the final 72 h. This protocol was based on our previous work18, which demonstrated this duration induces robust and consistent changes in the target genes of interest. The pro-inflammatory cytokines were added to the basolateral compartment in a medium containing 5.5 mM glucose and 10% (v/v) FBS on the evenings of days 11 and 12, and in a medium containing 5.5 mM glucose but free of FBS on day 13 to avoid protein interference in IL-8 estimation. On day 14, cell culture media from the basolateral compartment was collected in the inflamed cell model for IL-8 estimation. Cells were washed with chilled PBS thrice, and RNA and protein were collected for gene and protein expression studies (Fig. 2A). The samples were stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

Inflammation upregulates SGLT1, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in Caco-2/TC7 cells. (A) Graphical illustration of the experimental protocol for the standard and inflamed Caco-2/TC7 cell models. Cells were differentiated in 25 mM glucose until day 7, then in 5.5 mM glucose until day 14. Cells were differentiated for 14 days from confluence and treated with dexamethasone (DEX) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO (vehicle control) up to twice daily for 60 h, 24 h, or 4 h. For the inflamed model, a cytokine cocktail containing IL-1β (25 ng/mL) and TNF-α (50 ng/mL) was added to the basolateral (BL) once daily for 72 h. Finally, cell culture media from both apical (AP) and BL compartments were collected from the inflamed cells for IL-8 quantification. mRNA and protein were extracted from cells in both the standard and inflamed models and analysed through ddPCR and ELISA, respectively. A comparison of (B) IL-8 secretion and (C) SGLT1, (D) GLUT2, (E) ACE2 and (F) TMPRSS2 mRNA expression between standard (grey) and inflamed (blue) Caco-2/TC7 cells is shown. Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and absolute copies of SGLT1, GLUT2, ACE2 or TMPRSS2 cDNA measured by ddPCR are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene TBP. For IL-8 detection, cell culture media were processed, and IL-8 measured using ELISA and corrected for total protein measured by Bradford assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences between cells in the standard and inflamed environments in B-F were determined by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; ns—not significant, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. A—created with BioRender.com (https://BioRender.com/r16s632); B-F—created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1.

Gene expression analysis by droplet digital PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Aurum™ Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of RNA were determined using a Nanodrop 2000ND spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription was performed using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA reverse transcription kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative gene expression (SGLT1, GLUT2, ACE2, TMPRSS2 and TBP) was performed using a QX200 droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system (Bio-Rad), as we have done previously19. Each assay (20 µL) contained 8 μL cDNA (34.1 ng) diluted with RNAse and DNAse-free milliQ water, plus 1 μL FAM-labelled TaqMan primer (SGLT1, GLUT2, ACE2 and TMPRSS2), 1 μL VIC-labelled TaqMan primer for TBP (TATA-box binding protein reference gene), and 10 μL ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP, Bio-Rad), or various controls with each component absent. The ddPCR reaction mix was partitioned into 1 nL-sized droplets using a QX200 droplet generator following the manufacturer’s instructions, which were transferred to a 96-well ddPCR plate for PCR on a C1000 Touch™ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) and reading on a QX200 droplet reader. TBP was used as the reference gene to ensure consistency across ddPCR runs, as its expression remained stable across all treatment conditions, including dexamethasone and cytokine exposure. In preliminary experiments, GAPDH was also shown to be relatively stable, but its very high expression in Caco-2/TC7 cells (~ 26,000 copies GAPDH per ng cDNA) required sample dilution prior to ddPCR, which introduced variability and prevented co-amplification and quantification of the target and reference gene in the same well. The data were analysed using the QuantaSoft programme (version 1.7.4, Bio-Rad). The number of accepted droplets was > 12,000 for all the samples. Target DNA concentration (copies/μL) was calculated using Poisson distribution analysis.

Measurement of IL-8 secretion

In the inflamed Caco-2/TC7 cell model, the cells were co-treated with the cytokine cocktail (72 h) and dexamethasone (4 h, 24 h and 60 h), as mentioned in Section "Treatment of Caco-2/TC7 cells with dexamethasone and/or cytokines". To prevent protein interference with IL-8 estimation, FBS-free DMEM medium was employed in both cell compartments for the final 24 h. At the end of treatment, basolateral media was collected and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. The samples were thawed on ice, centrifuged (0.5 × g, 5 min, 4 °C), and the cell debris-free supernatant was transferred into a pre-labelled fresh tube on ice. IL-8 secreted into the culture media was determined using either the human IL-8 ELISA kit (Abcam) or a magnetic bead-based multiplex ELISA system (Magpix, Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Measurement of ACE2 protein expression

The human ACE2 ELISA kit (Abcam) was used to quantify ACE2 protein. Caco-2/TC7 cells were seeded and differentiated in 6-well transwell plates, and cells were treated with dexamethasone. After the treatments, cells were washed thrice in ice-cold PBS and stored in situ at − 80 °C until analysis. Cells were lysed and scraped from transmembrane filters using chilled cell extraction buffer PTR (supplied in the ELISA kit). The cell lysates were centrifuged (14,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C), and the supernatants were transferred into a pre-labelled fresh tube on ice. ACE2 protein quantification was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol, with a Bradford assay used to determine the total protein concentration in the supernatant.

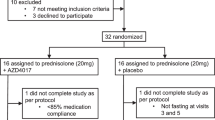

Data extraction from the NCBI gene expression omnibus (GEO) database and processing

We searched the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database for human or animal studies involving dexamethasone, with available transcriptomic data from the small intestine or colon. Our search yielded a single study utilising a mouse model with dexamethasone: GSE113691. This study investigated the role of glucocorticoid receptors in countering TNF-induced inflammation and the protective effects of dexamethasone in wild-type C57BL/6J mice and mice with diminished glucocorticoid receptor response. RNA-sequencing analysis of intestinal epithelial cells from the ileum was performed from wild-type and glucocorticoid receptor response diminished mice exposed to either PBS or 50 μg TNF for 8 h, with pre-treatment of PBS or dexamethasone (10 mg/kg) for 30 min. Our analysis specifically concentrated on data from the wild-type mouse group (standard and inflamed). A summary of the study details is presented in Fig. 8A; for a more complete overview of the methods, refer to the original papers20,21.

The raw counts from GSE113691 were processed and the trimmed mean of m-values (TMM) was used to normalise for library size using the Galaxy Australia platform (version 24.1; usegalaxy.org.au)22. Only genes with ≥ 1 count per million in at least 3 samples were carried forward. The genes were initially analysed individually using the normalised gene count in line with the approach used to analyse gene expression changes in Caco-2/TC7 cells. Subsequent analyses aimed to explore the effects of dexamethasone on the expression profiles of our target genes, SGLT1, GLUT2, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the intestinal epithelial cells isolated from the ileum of wild-type mice. Differential gene expression between control and treatment (dexamethasone) conditions was assessed using the limma-voom package (Galaxy Version 3.58.1 + galaxy0)23,24 on the Galaxy Australia platform. The Benjamini–Hochberg (1995) procedure was used to control multiple testing with the False Discovery Rate (FDR) set at 5%. Log2-fold change (log2FC) of at least 1 and FDR ≤ 0.05 was considered significant25. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using the GSEA software (version 4.3.3)26,27. Normalised counts from GSE113691 and the Hallmark gene set collection in the molecular signatures database28 for Mus musculus (mh.all.v2023.2.Mm.symbols.gmt) were utilised. Gene sets with sizes outside the range of 5 to 500 were excluded from the analysis. Enrichment significance was assessed based on a Normalised Enrichment Score (NES) greater than 1 and an FDR less than 0.2526,29, indicating significant enrichment magnitude and statistical significance, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Data were plotted, and all statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA). Welch’s t-test was employed to compare two independent groups with unequal variances. For comparisons between more than two groups, one-way or two-way ANOVA was employed, followed by Fisher’s LSD multiple comparison test. Associations between ACE2, SGLT1, GLUT2 and TMPRSS2 gene expression, and secreted IL-8 protein, were determined using Pearson correlation. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Dexamethasone increased glucose transport across Caco-2/TC7 cells

Given that dexamethasone administration has been associated with elevated postprandial blood glucose levels in both healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes2,30, we hypothesised that dexamethasone may directly enhance glucose absorption at the intestinal level. To investigate this, we used an in vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium consisting of fully differentiated Caco-2/TC7 monolayers, cultured under normal (5.5 mM) and high (25 mM) glucose conditions. Dexamethasone enhanced transcellular 2-deoxy-D-glucose transport dose-dependently in Caco-2/TC7 cells cultured in both normal and high concentrations of glucose (Fig. 1B and C). At the highest dexamethasone concentration, 2-deoxy-D-glucose transport was approximately 35% higher in the normal glucose environment compared to the high glucose condition (Fig. 1D).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines enhanced IL-8 secretion and SGLT1, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 mRNA expression

Understanding the effect of dexamethasone in both healthy and pro-inflammatory intestinal environments is important, particularly given the well-established links between chronic inflammation (including gut inflammation) and the development of type 2 diabetes31,32. To explore this, we investigated the effects of dexamethasone in both standard and inflamed Caco-2/TC7 cells. Inflammation was induced by treating Caco-2/TC7 cells with IL-1β and TNF-α, two key pro-inflammatory cytokines known to be elevated in people with type 2 diabetes and are major contributors to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease33,34,35,36. Following 72 h of cytokine treatment, IL-8 secretion into the basolateral compartment increased markedly (Fig. 2B), and this response was used to validate our inflammation model for subsequent experiments.

We initially assessed both IL-6 and IL-8 as markers of inflammation; however, IL-6 levels in Caco-2/TC7 cells remained consistently low and often below the detection limit, even after cytokine stimulation. Therefore, IL-8 was chosen as the inflammatory marker, as it is a well-characterised chemokine widely reported to be produced by intestinal epithelial cells in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β and TNF-α16,17. In unstimulated cells, IL-8 secretion was only 3.7 pg/mg of total protein, but increased to 16.9 pg/mg of total protein in cytokine-treated cells (P < 0.01). SGLT1, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 mRNA were considerably elevated in response to inflammation, whereas GLUT2 mRNA remained unchanged (Fig. 2).

Dexamethasone enhanced SGLT1 mRNA but reduced GLUT2 mRNA

We hypothesised that the increase in glucose transport was driven by dexamethasone-induced upregulation of glucose transporter expression, specifically SGLT1 and GLUT2, in Caco-2/TC7 cells. Dexamethasone exposure, both short- (4 h) and long-term (60 h) increased SGLT1 mRNA under both standard and inflamed conditions (Fig. 3), with the increase in the latter more profound after 60 h dexamethasone treatment (Fig. 3I). The increase in SGLT1 was > fivefold in the inflamed cells and nearly twofold in the standard cell model compared to the vehicle control . In contrast, GLUT2 expression was reduced considerably, by ~ 50% after 24 h and 60 h of dexamethasone treatment (Fig. 4). Between the two models, the reduction in GLUT2 expression did not differ substantially (Fig. 4, Panel 3).

Dexamethasone upregulates SGLT1 mRNA in Caco-2/TC7 cells. The acute and chronic effect of dexamethasone (DEX) on SGLT1 mRNA expression was assessed in 14-day differentiated Caco-2/TC7 cells, under either standard conditions (Panel 1) or an inflamed state induced by daily exposure to IL-1β and TNF-α during the final 72 h (Panel 2). Cells were treated with dexamethasone (5, 10, 20 µM) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle control for different time durations: (A, D) 4 h, (B, E) 24 h and (C, F) 60 h. A comparison of the effect of dexamethasone between standard (grey) and inflamed (blue) conditions is shown in Panel 3 (G—4 h, H—24 h, I—60 h). Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and absolute copies of SGLT1 cDNA measured by ddPCR are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene TBP. Values represent mean fold change compared to DMSO vehicle control (Panel 1) or cytokine-treated DMSO vehicle control (Panel 2). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences were determined as follows: A, D, G—unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; B-C, E–F—one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test; H, I—two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. ns—not significant, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Graphs created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1.

Dexamethasone downregulates GLUT2 mRNA in Caco-2/TC7 cells. The acute and chronic effect of dexamethasone (DEX) on GLUT2 mRNA expression was assessed in 14-day differentiated Caco-2/TC7 cells, under either standard conditions (Panel 1) or an inflamed state induced by daily exposure to IL-1β and TNF-α during the final 72 h (Panel 2). Cells were treated with dexamethasone (5, 10, 20 µM) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle control for different time durations: (A, D) 4 h, (B, E) 24 h and (C, F) 60 h. A comparison of the effect of dexamethasone between standard (grey) and inflamed (blue) conditions is shown in Panel 3 (G—4 h, H—24 h, I—60 h). Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and absolute copies of GLUT2 cDNA measured by ddPCR are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene TBP. Values represent mean fold change compared to DMSO vehicle control (Panel 1) or cytokine-treated DMSO vehicle control (Panel 2). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences were determined as follows: A, D, G—unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; B-C, E–F—one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test; H, I—two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. ns—not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001. Graphs created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1.

Dexamethasone reduced ACE2 mRNA and protein

Since dexamethasone is widely used to treat severely ill SARS-CoV-2 patients, we hypothesised that the drug could modulate the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 to reduce viral entry. To investigate this, we examined the effect of dexamethasone on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in both standard and inflamed Caco-2/TC7 cell models. Dexamethasone reduced ACE2 mRNA in the standard and inflamed cell models (Fig. 5), with the decrease being more significant in the standard cell model, particularly after 60 h (Fig. 5I). To confirm our findings at the protein level, ACE2 protein in Caco-2/TC7 cells was measured using ELISA. Dexamethasone reduced ACE2 protein in both models, more pronounced after 60 h of treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although the mRNA data point to an enhanced reduction in ACE2 in the standard cell model, there were no substantial differences in the effect on ACE2 protein between the two models (Fig. S1, Panel 3).

Dexamethasone downregulates ACE2 mRNA in Caco-2/TC7 cells. The acute and chronic effect of dexamethasone (DEX) on ACE2 mRNA expression was assessed in 14-day differentiated Caco-2/TC7 cells, under either standard conditions (Panel 1) or an inflamed state induced by daily exposure to IL-1β and TNF-α during the final 72 h (Panel 2). Cells were treated with dexamethasone (5, 10, 20 µM) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle control for different time durations: (A, D) 4 h, (B, E) 24 h and (C, F) 60 h. A comparison of the effect of dexamethasone between standard (grey) and inflamed (blue) conditions is shown in Panel 3 (G—4 h, H—24 h, I—60 h). Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and absolute copies of ACE2 cDNA measured by ddPCR are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene TBP. Values represent mean fold change compared to DMSO vehicle control (Panel 1) or cytokine-treated DMSO vehicle control (Panel 2). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences were determined as follows: A, D, G—unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; B-C, E–F—one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test; H, I—two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. ns—not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Graphs created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1.

Dexamethasone increased TMPRSS2 mRNA

In both standard and inflamed models, dexamethasone significantly increased TMPRSS2 mRNA (Fig. 6). The increase was evident from 4 h of dexamethasone stimulation and was more profound in the standard model than inflamed; dexamethasone doubled TMPRSS2 mRNA in the standard model compared to the control, while the increase in inflamed cells was around 1.5-fold. However, the differences between the two models were not substantial in the longer term (Fig. 6, Panel 3).

Dexamethasone upregulates TMPRSS2 mRNA expression in Caco-2/TC7 cells. The acute and chronic effect of dexamethasone (DEX) on TMPRSS2 mRNA expression was assessed in 14-day differentiated Caco-2/TC7 cells, under either standard conditions (Panel 1) or an inflamed state induced by daily exposure to IL-1β and TNF-α during the final 72 h (Panel 2). Cells were treated with DEX (5, 10, 20 µM) or 0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle control for different time durations: (A, D) 4 h, (B, E) 24 h and (C, F) 60 h. A comparison of the effect of DEX between standard (grey) and inflamed (blue) conditions is shown in Panel 3 (G—4 h, H—24 h, I—60 h). Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and absolute copies of TMPRSS2 cDNA measured by ddPCR are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene TBP. Values represent mean fold change compared to DMSO vehicle control (Panel 1) or cytokine-treated DMSO vehicle control (Panel 2). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 technical replicates from N = 3 biological replicates). Differences were determined as follows: A, D, G—unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction; B-C, E–F—one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test; H, I—two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. ns—not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Graphs created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1.

Dexamethasone had little effect on inflammation-induced IL-8 secretion

Since dexamethasone is a well-known anti-inflammatory drug, we assumed it to reduce cytokine-induced IL-8 secretion. However, neither acute nor chronic dexamethasone treatment decreased cytokine-induced IL-8 secretion in Caco-2/TC7 cells, except those exposed to 5 µM dexamethasone for 24 h (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Correlation analysis

The correlations between dexamethasone-induced changes in SGLT1, GLUT2, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 mRNA, and secreted IL-8 protein, were analysed using Pearson correlation. A significant positive association was seen between the magnitude of changes in the glucose transporters and TMPRSS2 (Fig. 7). Further, changes in GLUT2 were positively correlated with IL-8 secretion. No association was seen between ACE2 and the other genes or IL-8.

Pearson correlation analysis. (A) Pearson correlation matrix showing the association between variables. Blue represents a positive correlation, and red represents a negative correlation. (B) Table showing the statistical significance of the relationship between variables examined by Pearson correlation analysis. ACE2, TMPRSS2, SGLT1 and GLUT2 are mRNA expression levels; IL-8 is a secreted protein. The correlation matrix was created with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.1. ns—not significant; ***P < 0.001.

Dexamethasone-induced transcriptional changes in intestinal epithelial cells in vivo (GSE113691)

To evaluate whether the transcriptional effects of dexamethasone observed in Caco-2/TC7 cells are also evident in vivo, we analysed publicly available RNA-sequencing data from GSE113691, a murine study in which wild-type and glucocorticoid receptor-deficient mice were pre-treated with dexamethasone before TNF-α-induced inflammation. We initially aimed to validate our findings using human intestinal transcriptomic datasets, but we were unable to identify a suitable dataset that included both clear steroid treatment metadata and appropriately matched inflamed controls. Our current aim was to determine whether dexamethasone modulates the expression of intestinal glucose transporters (SGLT1 and GLUT2) and viral entry factors (ACE2 and TMPRSS2) in the ileal epithelium of wild-type mice under both standard and inflamed conditions.

In wild-type mice treated with TNF-α, dexamethasone administration significantly increased SGLT1, GLUT2 and ACE2 in the ileal enterocytes under both standard and inflamed conditions using normalised gene count data (Fig. 8). TMPRSS2 was only increased in the standard mice treated with dexamethasone, with no significant elevation in the inflamed (Fig. 8C). Using differential gene expression analysis, dexamethasone treatment resulted in the upregulation of 407 and the downregulation of 503 genes in standard mice, and the upregulation of 206 genes and the downregulation of 180 in inflamed mice (FDR ≤ 0.05 and log2FC ≥ 1.0, Fig. 8G and J). Specifically, dexamethasone treatment significantly increased SGLT1, TMPRSS2 and GLUT2 mRNA in wild-type mice compared to controls (Fig. 8H). However, except for GLUT2, no significant alterations in the expression of other genes were observed in the inflamed group in response to dexamethasone (log2FC ≤ 1). GLUT2 expression was notably upregulated in both groups following dexamethasone treatment, with log2FC values of 3.2 and 2.2, respectively (Fig. 8H). Despite a significant increase in ACE2 expression observed in both models based on normalised gene counts (Fig. 8E), the change in ACE2 mRNA was not significant according to differential gene expression analysis (log2FC ≤ 1).

Gene expression changes in dexamethasone-treated and untreated normal and inflamed enterocytes from wild-type C57BL/6 J mice. (A) A summary of the GSE113691 study and the samples considered for analysis. Raw counts obtained from the NCBI GEO database (GSE113691) were filtered (< 1 count per million in at least 3 samples) and were normalised using the trimmed mean of m-values (TMM). Differences in (B) SGLT1, (C) TMPRSS2, (D) GLUT2, (E) ACE2 gene expression in enterocytes from normal mice (NM) and inflamed mice (IF) between dexamethasone-treated (NM-D, IF-D) and untreated mice (NM-C, IF-C). Volcano plot showing (F) 910 differentially expressed genes between NM-D and NM-C and (I) 386 differentially expressed genes between IF-D and IF-C. Venn diagrams depicting upregulated and downregulated genes in (G) NM-D and (J) IF-D treatment groups compared to controls NM-C and IF-C, respectively. Red indicates upregulation and blue indicates downregulation (log2FC ≥ 1, FDR ≤ 0.05), overlapping indicates the unchanged number of genes. (H) Log2FC of SGLT1, TMPRSS2, GLUT2, and ACE2 between NM-D vs. NM-C and IF-D vs. IF-C (*indicates significantly differentially expressed genes (log2FC ≥ 1, FDR ≤ 0.05)). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis on the mouse Hallmark signature collection, showing positively and negatively enriched gene sets in (K) NM-D vs. NM-C and (L) IF-D vs. IF-C. Orange bars indicate gene sets enriched in both groups. (M) Pearson correlation matrix showing associations between SGLT1, TMPRSS2, GLUT2, and ACE2 mRNA expression in mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Blue represents positive correlation, red represents negative correlation. (B-E) Data are presented as mean ± SD (N = 3). (B-E) Significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test. ns—not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DEX—dexamethasone, NM-C—normal mouse control, NM-D—normal mouse treated with dexamethasone, IF-C—inflamed mouse control, IF-D—inflamed mouse treated with dexamethasone, NES—normalised enrichment score.

GSEA identified specific gene sets that were differentially enriched between the experimental groups. Overall, 13 gene sets were positively/negatively enriched in the dexamethasone-treated standard mice, while 16 gene sets showed enrichment in the dexamethasone-treated inflamed mice compared to their respective controls (FDR ≤ 0.25 and NES ≥ 1, Fig. 8K and L). Gene sets associated with pancreatic β-cells, KRAS signalling downregulation, interferon-α and -γ responses, E2f. targets, and G2m checkpoints displayed similar enrichment patterns in both groups (orange bars in Fig. 8K and L).

A significant positive association using Pearson correlation analysis was observed between SGLT1 and TMPRSS2 (P < 0.001), but not between GLUT2 and TMPRSS2, in intestinal enterocytes isolated from murine ileum (Fig. 8M). SGLT1 and GLUT2 significantly positively associated with ACE2 (P < 0.01).

Discussion

This study examined the effects of dexamethasone on glucose transporters and SARS-CoV-2 viral entry receptors in the intestine in both standard and cytokine-treated conditions. Our findings reveal that dexamethasone dose-dependently increases 2-deoxy-D-glucose transport in differentiated human intestinal Caco-2/TC7 monolayers, primarily through upregulation of SGLT1.

The intestinal mechanism seen in our work aligns with clinical observations showing dose-dependent increases in blood glucose and related markers with both oral and intravenous dexamethasone administration2,3,30,37. Our data indicate that SGLT1 mRNA expression and glucose transport activity rise significantly in response to dexamethasone, and this response is amplified under inflammatory conditions, a finding particularly relevant to people with type 2 diabetes and obesity, where low-grade chronic inflammation is prevalent31,32,38. These individuals are more susceptible to steroid-induced hyperglycaemia11, and inflammation may exacerbate glucocorticoid-induced increases in SGLT1. Additionally, insulin resistance in such patients may impair insulin-mediated internalisation of GLUT239 and downregulation of SGLT140 on the intestinal brush border membrane, compounding glucose absorption and glycaemic burden.

Interestingly, while SGLT1 mRNA expression was enhanced by dexamethasone, GLUT2 expression decreased in both standard and inflamed models. The reason for this differential regulation is not entirely clear, but it likely reflects distinct regulatory mechanisms. SGLT1 is known to be transcriptionally regulated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) via glucocorticoid response elements (GREs)9. In contrast, dexamethasone has been shown to repress GLUT2 transcription in pancreatic β-cells via GR-mediated downregulation of the key transcription factors HNF1α and HNF1β41. In the context of the gut, the downregulation of GLUT2 might also reflect an adaptive response aimed at limiting glucose transport resulting from enhanced SGLT1 activity, thereby protecting enterocytes from further metabolic and oxidative stress. Supporting this idea, studies in mice have shown that intestinal GLUT2 knockdown can help preserve gut barrier function, reduce susceptibility to infection, modulate gut microbiota composition, and dampen systemic inflammation42,43.

In parallel, we explored the effect of dexamethasone on the SARS-CoV-2 viral entry proteases, ACE2 and TMPRSS2. TMPRSS2 mRNA expression increased in both standard and inflammatory conditions, suggesting glucocorticoid-responsive regulation independent of inflammation. TMPRSS2 facilitates viral entry by priming the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein44, and higher TMPRSS2 expression has been linked to greater susceptibility and severity of infection45,46. Our findings suggest that dexamethasone may enhance intestinal vulnerability to viral entry through TMPRSS2 upregulation.

We also observed short-term (4 h) dexamethasone exposure did not substantially affect ACE2 mRNA or protein expression in either cell model. However, longer-term (60 h) dexamethasone exposure led to a marked decrease in both ACE2 mRNA and protein, with protein levels reduced by approximately 20% in both models, pointing to a chronic effect of dexamethasone on gut ACE2. While reduced ACE2 expression might theoretically lower susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, ACE2 downregulation is also associated with adverse outcomes47, including the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, making it a complex and potentially unfavourable therapeutic target. Beyond its role in SARS-CoV-2 entry44, ACE2 also plays a protective anti-inflammatory role in the gut via the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis13. Its activity is linked to amino acid transport, gut barrier integrity, incretin hormone release, and the gut microbiome13. In our previous study, we found that ACE2 increased with cytokine exposure duration in Caco-2/TC7 cells, while IL-8 levels decreased concurrently18, suggesting that ACE2 may have an anti-inflammatory function in intestinal cells. Consistent with this, despite the known systemic anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone, we did not observe any reduction in IL-8 expression in our model. These findings raise concern that dexamethasone-induced suppression of ACE2 could impair gut homeostasis and potentially worsen outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes or COVID-19.

To assess whether our in vitro findings extend to an in vivo context, we analysed transcriptomic data from the GSE113691 mouse study20,21. Consistent with our Caco-2/TC7 cell model, dexamethasone increased SGLT1 and TMPRSS2 expression in ileal epithelial cells from wild-type mice. Similar to what was seen in Caco-2/TC7 cells, in both murine models, SGLT1 showed a more robust upregulation than TMPRSS2. This effect was more pronounced in standard animals treated with dexamethasone compared to their inflammation-induced counterparts. Similar results were observed in Caco-2/TC7 cells treated with dexamethasone for 4 h; however, after 24 h, SGLT1 upregulation became more pronounced in the inflamed Caco-2/TC7 cells. It is important to note that in the GSE113691 study, the animals were exposed to dexamethasone for only ~ 8 h, suggesting that the acute and chronic effects of dexamethasone on SGLT1 may vary depending on inflammatory status.

The number of genes differentially expressed was higher in the dexamethasone-treated standard mice compared to the inflamed mice, suggesting a blunted response during inflammation. Common enrichment patterns related to pancreatic β-cells, KRAS signalling, interferon responses, E2f targets, and the G2m checkpoint were evident in both dexamethasone-treated groups. It is challenging to definitively ascertain which specific gene sets or individual genes contribute to the observed increases in SGLT1, TMPRSS2, and GLUT2 expression in response to dexamethasone. Investigating the six commonly enriched gene sets between the two groups may provide a valuable starting point for elucidating the underlying mechanisms.

The strong correlation between the expression of SGLT1, GLUT2, and TMPRSS2, both in vitro and in the dexamethasone-treated mouse dataset (GSE113691), raises the possibility of a shared regulatory mechanism. While SGLT1 is known to be regulated through dimerization-dependent binding of the GR to GREs9, the mechanism by which TMPRSS2 responds to glucocorticoids remains unclear. Several intersecting pathways may contribute to the co-regulation of SGLT1 and TMPRSS2, with one key element being serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), a GR-responsive kinase that promotes sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) and SGLT1 transcription and modulates inflammatory signalling in epithelial tissues9,48. A central pathway in this context is the PI3K-Akt-SGK1 signalling cascade, which is activated downstream of HGF/c-Met signalling49. While a direct link between this pathway and SGLT1 expression has not been established, previous studies have demonstrated that activation of pro-hepatocyte growth factor (pro-HGF), a substrate of TMPRSS250, increases SGLT1 expression in the gut51, suggesting that TMPRSS2, by activating pro-HGF, may indirectly enhance SGLT1 transcription via this pathway. In relation to GLUT2, HGF/c-Met signalling has been implicated in reduced GLUT2 expression in pancreatic β-cells52. Additionally, protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2), another TMPRSS2 substrate53, has been implicated in hepatic GLUT2 regulation and glucose homeostasis54. Moreover, SGK1 has been shown to modulate NF-κB activity48, and PAR-2 activation is also known to stimulate NF-κB signalling55. Together, these findings support the existence of a shared signalling network, in which TMPRSS2 activity may enhance glucose absorption via SGK1-mediated SGLT1 expression, while concurrently modulating inflammation through NF-κB-associated pathways.

Although these mechanisms remain to be confirmed, our study offers a foundation for future research. Future studies should employ knockdown or knockout models of TMPRSS2, SGLT1 and potentially SGK1, to determine whether these genes are functionally linked, that is, whether one directly influences the other, or if their coordinated expression is due to regulation by a shared upstream pathway. Inhibition of c-Met or PI3K-Akt-SGK1 signalling would help clarify the role of this pathway in mediating the effects of dexamethasone. Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR and promoter-reporter assays would help determine whether these genes are directly regulated by GR or its co-factors.

Limitations of the study

This study provides valuable insight into the regulation of intestinal glucose transporters and SARS-CoV-2 viral entry receptors by dexamethasone; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. A key limitation is that we measured only the mRNA expression of SGLT1, GLUT2 and TMPRSS2; mRNA levels do not always correlate with protein abundance or functional activity, and future studies should validate these findings at the protein and functional levels. Additionally, glucose uptake was assessed using 2-deoxy-D-glucose, a non-metabolised glucose analogue with limited affinity for SGLT156, which may not accurately reflect sodium-coupled glucose transport. The use of Caco-2/TC7 cells, while well-established, presents further limitations due to their cancer-derived origin and colonic phenotype, which only partially reflect the function of the human small intestine. In addition, this study did not investigate the potential role of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis, which is known to influence both glucose transporter and inflammation, and may represent a key mechanistic link between inflammation, glucocorticoid signalling, and epithelial transport function. Future studies should focus on elucidating the underlying mechanisms by which dexamethasone and inflammation regulate SGLT1 and TMPRSS2 expression, particularly by investigating the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis, GR-SGK1 axis, HGF/c-Met signalling, and NF-κB-associated inflammatory pathways described above. Despite these limitations, our findings offer a strong foundation for future investigations into the intestinal effects of glucocorticoids.

Conclusions

Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycaemia is a frequent complication often requiring regular blood glucose monitoring and glycaemic management in patients. This study demonstrates that dexamethasone increases intestinal glucose uptake by upregulating SGLT1 expression in both healthy and inflamed human intestinal epithelial cells, potentially exacerbating impaired glucose control in susceptible individuals. In parallel, dexamethasone modulates the expression of key viral entry factors, notably downregulating ACE2 with prolonged exposure and upregulating TMPRSS2, which may partly explain the adverse outcomes observed with early glucocorticoid use in COVID-19 patients. Importantly, our findings suggest a potential co-regulation of SGLT1 and TMPRSS2, indicating a broader functional role for TMPRSS2 in the gut beyond viral priming, possibly linked to metabolic and inflammatory regulation. These observations may be particularly relevant in individuals with obesity or type 2 diabetes, where chronic inflammation and glucose dysregulation are common. In such contexts, glucocorticoid therapy may not only exacerbate hyperglycaemia but also increase epithelial susceptibility to infection. These findings highlight the need to consider intestinal responses when evaluating the risks and benefits of steroid treatment in metabolically vulnerable populations.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and additional data is available upon reasonable request from Prof Gary Williamson (gary.williamson1@monash.edu).

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS:

-

Heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- GLUT2:

-

Glucose transporter 2

- HPAEC-PAD:

-

High-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1 beta

- log2FC:

-

Log2-fold change

- NEAA:

-

Nonessential amino acids

- NES:

-

Normalised Enrichment Score

- NHE3:

-

Sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3

- SGK1:

-

Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1

- SGLT1:

-

Sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1

- TBP:

-

TATA-box binding protein reference gene

- TMM:

-

Trimmed mean of m-values

- TMPRSS2:

-

Transmembrane protease, serine 2

- α-TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Li, J.-X. & Cummins, C. L. Fresh insights into glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus and new therapeutic directions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 540–557 (2022).

Abdelmannan, D., Tahboub, R., Genuth, S. & Ismail-Beigi, F. Effect of dexamethasone on oral glucose tolerance in healthy adults. Endocr. Pract. 16, 770–777 (2010).

Hans, P., Vanthuyne, A., Dewandre, P. Y., Brichant, J. F. & Bonhomme, V. Blood glucose concentration profile after 10 mg dexamethasone in non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Br. J. Anaesth 97, 164–170 (2006).

Douard, V., Choi, H., Elshenawy, S., Lagunoff, D. & Ferraris, R. P. Developmental reprogramming of rat GLUT5 requires glucocorticoid receptor translocation to the nucleus. J. Physiol. 586, 3657–3673 (2008).

Sakoda, H. et al. Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is due to inhibition of glucose transport rather than insulin signal transduction. Diabetes 49, 1700–1708 (2000).

Niu, L. et al. Effects of chronic dexamethasone administration on hyperglycemia and insulin release in goats. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 26 (2018).

Grahammer, F. et al. Intestinal function of gene-targeted mice lacking serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 290, 1114–1123 (2006).

Liu, H., Liu, L. & Li, F. Effects of glucocorticoids on the gene expression of nutrient transporters in different rabbit intestinal segments. Animal 14, 1693–1700 (2020).

Reichardt, S. D. et al. Glucocorticoids enhance intestinal glucose uptake via the dimerized glucocorticoid receptor in enterocytes. Endocrinology 153, 1783–1794 (2012).

Stojanovska, L., Rosella, G. & Proietto, J. Dexamethasone-induced increase in the rate of appearance in plasma of gut-derived glucose following an oral glucose load in rats. Metabolism 40, 297–301 (1991).

Taheri, N., Aminorroaya, A., Ismail-Beigi, F. & Amini, M. Effect of dexamethasone on glucose homeostasis in normal and prediabetic subjects with a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Pract. 18, 855–863 (2012).

Gkogkou, E., Barnasas, G., Vougas, K. & Trougakos, I. P. Expression profiling meta-analysis of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, the putative anti-inflammatory receptor and priming protease of SARS-CoV-2 in human cells, and identification of putative modulators. Redox Biol. 36, 101615 (2020).

Penninger, J. M., Grant, M. B. & Sung, J. J. Y. The role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in modulating gut microbiota, intestinal inflammation, and coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology 160, 39–46 (2021).

Caro, I. et al. Characterisation of a newly isolated Caco-2 clone (TC-7), as a model of transport processes and biotransformation of drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 116, 147–158 (1995).

Barber, E., Houghton, M. J., Visvanathan, R. & Williamson, G. Measuring key human carbohydrate digestive enzyme activities using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2882–2919 (2022).

Van De Walle, J., Hendrickx, A., Romier, B. & Larondelle, Y. Schneider YJInflammatory parameters in Caco-2 cells: Effect of stimuli nature, concentration, combination and cell differentiation. Toxicol. in Vitro 24, 1441–1449 (2010).

Hollebeeck, S. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) husk ellagitannins in Caco-2 cells, an in vitro model of human intestine. Food Funct. 3, 875 (2012).

Visvanathan, R., Houghton, M. J. & Williamson, G. Impact of glucose, inflammation and phytochemicals on ACE2, TMPRSS2 and glucose transporter gene expression in human intestinal cells. Antioxidants 14, 253 (2025).

Houghton, M. J., Kerimi, A., Tumova, S., Boyle, J. P. & Williamson, G. Quercetin preserves redox status and stimulates mitochondrial function in metabolically-stressed HepG2 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 129, 296–309 (2018).

Van Looveren, K. et al. Glucocorticoids limit lipopolysaccharide-induced lethal inflammation by a double control system. EMBO Rep. 21, e49762 (2020).

Ballegeer, M. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor dimers control intestinal STAT1 and TNF-induced inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3265–3279 (2018).

Afgan, E. et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W3–W10 (2016).

Law, C. W., Chen, Y., Shi, W. & Smyth, G. K. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome. Biol. 15, R29 (2014).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Chen, W. et al. Live-seq enables temporal transcriptomic recording of single cells. Nature 608, 733–740 (2022).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Powers, R. K., Goodspeed, A., Pielke-Lombardo, H., Tan, A.-C. & Costello, J. C. GSEA-InContext: identifying novel and common patterns in expression experiments. Bioinformatics 34, i555–i564 (2018).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Liu, S. et al. ZNF384: A potential therapeutic target for psoriasis and alzheimer’s disease through inflammation and metabolism. Front Immunol. 13, 892368 (2022).

Limbachia, V. et al. The effect of different types of oral or intravenous corticosteroids on capillary blood glucose levels in hospitalized inpatients with and without diabetes. Clin. Ther. 46, e59–e63 (2024).

Jess, T., Jensen, B. W., Andersson, M., Villumsen, M. & Allin, K. H. Inflammatory bowel diseases increase risk of type 2 diabetes in a nationwide cohort study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 881-888.e1 (2020).

Tsalamandris, S. et al. The role of inflammation in diabetes: Current concepts and future perspectives. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 14, 50–59 (2019).

Domazet, S. L. et al. Low-grade inflammation in persons with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes: The role of abdominal adiposity and putative mediators. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 2092–2101 (2024).

Okdahl, T. et al. Low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study from a Danish diabetes outpatient clinic. BMJ Open 12, e062188 (2022).

Mesia, R. et al. Systemic inflammatory responses in patients with type 2 diabetes with chronic periodontitis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 4, e000260 (2016).

Liso, M. et al. Interleukin 1β blockade reduces intestinal inflammation in a murine model of tumor necrosis factor-independent ulcerative colitis. CMGH 14, 151–171 (2022).

Tien, M. et al. The effect of anti-emetic doses of dexamethasone on postoperative blood glucose levels in non-diabetic and diabetic patients: a prospective randomised controlled study. Anaesthesia 71, 1037–1043 (2016).

Ellulu, M. S. & Samouda, H. Clinical and biological risk factors associated with inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocr. Disord. 22, 16 (2022).

Tobin, V. et al. Insulin internalizes GLUT2 in the enterocytes of healthy but not insulin-resistant mice. Diabetes 57, 555–562 (2008).

Pennington, A. M., Corpe, C. P. & Kellett, G. L. Rapid regulation of rat jejunal glucose transport by insulin in a luminally and vascularly perfused preparation. J. Physiol. 478, 187–193 (1994).

Ono, Y. & Kataoka, K. Glucocorticoids reduce Slc2a2 (GLUT2) gene expression through HNF1 in pancreatic β-cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 74, e240077 (2024).

Thaiss, C. A. et al. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science 1979(359), 1376–1383 (2018).

Schmitt, C. C. et al. Intestinal invalidation of the glucose transporter GLUT2 delays tissue distribution of glucose and reveals an unexpected role in gut homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 6, 61–72 (2017).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271-280.e8 (2020).

David, A. et al. A common TMPRSS2 variant has a protective effect against severe COVID-19. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 70, 103333 (2022).

Iwata-Yoshikawa, N. et al. TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 93, 10–1128 (2019).

Banu, N., Panikar, S. S., Leal, L. R. & Leal, A. R. Protective role of ACE2 and its downregulation in SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to Macrophage Activation Syndrome: Therapeutic implications. Life Sci 256, 117905 (2020).

Gong, R., Rifai, A., Ge, Y., Chen, S. & Dworkin, L. D. Hepatocyte growth factor suppresses proinflammatory NFκB activation through GSK3β inactivation in renal tubular epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7401–7410 (2008).

Shelly, C. & Herrera, R. Activation of SGK1 by HGF, Rac1 and integrin-mediated cell adhesion in MDCK cells: PI-3K-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1985–1993 (2002).

Lucas, J. M. et al. The androgen-regulated protease TMPRSS2 Activates a proteolytic cascade involving components of the tumor microenvironment and promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Discov. 4, 1310–1325 (2014).

Kato, Y., Yu, D. & Schwartz, M. Z. Hepatocyte growth factor up-regulates SGLT1 and GLUT5 gene expression after massive small bowel resection. J. Pediatr. Surg. 33, 13–15 (1998).

Roccisana, J. et al. Targeted inactivation of hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-met in β-cells leads to defective insulin secretion and GLUT-2 downregulation without alteration of β-cell mass. Diabetes 54, 2090–2102 (2005).

Wilson, S. et al. The membrane-anchored serine protease, TMPRSS2, activates PAR-2 in prostate cancer cells. Biochem. J. 388, 967–972 (2005).

Shearer, A. M. et al. PAR2 promotes impaired glucose uptake and insulin resistance in NAFLD through GLUT2 and Akt interference. Hepatology 76, 1778–1793 (2022).

Johnson, J. J. et al. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2)-mediated Nf-κB activation suppresses inflammation-associated tumor suppressor MicroRNAs in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6936–6945 (2016).

Wright, E. M., Hirayama, B. A. & Loo, D. F. Active sugar transport in health and disease. J. Intern. Med. 261, 32–43 (2007).

Acknowledgements

RV would like to acknowledge a Monash Graduate Scholarship and a Monash International Tuition Scholarship from Monash University for PhD funding. This work is supported by Galaxy Australia, a service provided by Australian BioCommons and its partners. The service receives NCRIS funding through Bioplatforms Australia, as well as The University of Melbourne and Queensland Government RICF funding.

Funding

GW received funding from Monash University for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing–original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualisation. MJH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. EB: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. KD: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. NJK: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. GW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Visvanathan, R., Houghton, M.J., Barber, E. et al. Dexamethasone enhances intestinal glucose absorption and TMPRSS2 expression with implications for hyperglycaemia and infection risk. Sci Rep 15, 38329 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22312-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22312-8