Abstract

Social cognition processes are essential for social interaction. Theory of Mind (ToM) is a complex component of social cognition involved in understanding one’s own and others’ thoughts and feelings, relying on well-established brain networks (ToM hardware). Interindividual differences emerge in how people recruit brain resources for mentalizing operations (ToM software), revealing a gap between brain status and cognitive performance. The present research aimed to test the role of cognitive reserve (CR) in explaining this gap. Fifty-seven adults underwent an MRI to evaluate neural integrity, and a neuropsychological assessment including ToM measures, and a retrospective interview on lifetime experiential factors. The tri-component model of CR was considered: neural integrity (both coarse-grained intracranial volume, and fine-grained ToM network volume indexes), experiential factors, and ToM performance. Multiple regression and mediation models confirmed the CR hypothesis, highlighting the predictive role of both ToM neural integrity and experiential factors (Work and Leisure time) on ToM performance, and the mediating role of the experiential factors on the link between ToM neural integrity and performance. The study suggested the role of CR in social cognition. Future studies may explore the implications of this relationship in clinical and rehabilitation settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social cognition refers to the set of cognitive processes involved in understanding, interpreting, and responding to social cues1. It is essential for effective social interaction and forms the foundation for a satisfying social life1. In the DSM-5, social cognition is recognized as one of the six key domains of cognitive function, comprising three subdomains: emotion recognition, insight, and Theory of Mind (ToM)2. Of these, ToM ability is defined as a complex and central component. Also known as mentalizing, ToM is fundamental for understanding one’s own and others’ thoughts, feelings, and intentions to influence and predict behavior3. ToM is also defined as a multidimensional construct. Cognitive ToM refers to the understanding of cognitive mental states, e.g., intentions, beliefs, and thoughts, while affective ToM pertains to affective mental state comprehension, such as emotions4. Moreover, two levels of complexity in mental state attribution, defined as first- and second-order ToM, concern the adoption of a single-person perspective and the perspective of a person on another individual, respectively5. It has been hypothesized that ToM continues to develop across the lifespan, involving behavioral abilities and neural plasticity3. The literature identifies essential ToM neural hubs including a core circuit that relies on temporo-parietal junction, precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, and superior temporal sulcus; limbic-paralimbic areas, such as the amygdala, temporal pole, anterior cingulate cortex, striatum; and frontal loops, including the dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the orbitofrontal and inferolateral frontal cortex6.

Although the integrity of these neural networks is recognized as ToM hardware, interindividual differences emerge in how people efficiently recruit these brain areas for mentalizing operations, through functional neural activations, referred to as ToM software. These interindividual differences help explain a gap between neural integrity (i.e., ToM hardware), also named brain reserve, and cognitive performance (i.e., ToM software). Various factors might play a role in explaining the extent to which people’s performance depends on structural integrity, such as environmental contributors. The cognitive reserve (CR) paradigm explains the role of environmental factors in shaping different trajectories of the brain’s ability to maximize cognitive performance7. In particular, it can be argued that individuals who spend more time on mental activities show greater efficiency in recruiting brain networks to sustain cognitive functions, activating protective mechanisms against the effects of pathology and age-related cognitive impairment8,9. In this framework, cognitively stimulating activities accrued during the lifespan, i.e., high educational attainment, elevated cognitive-load working activity, and cognitively engaging hobbies, indeed, represent a reserve buffer accumulated across the lifespan able to enhance resilience7,10,11.

Given the complexity of evaluating CR taking account of all related factors (brain status, experiential/genetic factors, cognition), a direct measure of CR is not feasible. Instead, several psychosocial variables, such as an individual’s lifetime mental activities (i.e., education, working and leisure-time activities), are collected as informative CR proxies12. Educational attainment is the proxy most widely adopted in the literature13,14, yet it is also the most criticized as a partial measure of lifetime experience typically accumulated in early life. In contrast, standardized scales assessing multidimensional lifetime mental activity are increasingly used12,15, capturing past complex cognitively engaging activities encompassing education, working activities and leisure time pursuits.

Several previous studies demonstrated the protective role of CR proxies on neurocognitive domains, such as overall cognition, memory, language, and attention, in older adults14,15,16. This body of evidence suggests that the degree to which individuals engaged in mentally stimulating activities during life may explain individual differences also in social cognitive abilities. Thus, engaging in cognitively stimulating experiences can enhance social cognitive skills, such as the ability to interact with others, understand their perspectives, and navigate social situations. In this regard, for example, recent findings have shown a positive effect of long-term exposure to cognitive-stimulating activities, such as to both literary and popular fiction, on mentalizing16,17. These mental activities may enhance individuals’ proficiency in understanding others’ points of view and emotional experiences, enhancing the efficiency of social brain networks in complex social situations.

However, the literature reports contrasting findings regarding the role of CR proxies in the domain of social cognition. Recent studies have found no association between social cognition and experiential factors in healthy older adults18,19, suggesting that cognitively stimulating experience accumulated across the lifespan does not act as a buffer to sustain social cognition abilities. In contrast, studies by Li et al.20 and Salas et al.21 supported the link of educational attainment level with ToM by including both young and older adults. An aspect to be considered is that these studies mainly focused on two components of CR, cognitive performance and CR proxies, without assessing the brain changes. As suggested by Stern et al.5, to properly operationalize the CR model, the effect of CR proxies should be examined on the link between brain change and cognitive level.

Recently, Machado et al.18 explored the roles of CR proxy (education level) and brain reserve in relation to social cognition levels in Multiple Sclerosis and revealed a protective effect of brain reserve, but not the CR proxy on social cognition. The brain reserve index considered was the total intracranial volume, which, although the most commonly adopted proxy of brain reserve, offers limited insight into brain changes driven by lifestyle, aging, and pathology19, and may not accurately reflect functional brain capacity.

Given the contrasting evidence regarding the CR hypothesis in social cognition abilities, the present study employed a multidomain CR proxy assessment and a multi-component CR model to address the following research questions:

-

Do cognitively stimulating experiential factors, such as education, working activities, and leisure time, mediate the link between neural integrity and complex social cognition ability in healthy adults?

-

Does a specific domain of lifetime experiential factors best explain the link between social cognition ability and neural integrity?

-

Does fine-grained (social cognition network volume) compared to coarse-grained (total intracranial volume) neural index best operationalize brain status in this CR model?

Results

Participants

Fifty-seven individuals took part in the research. Table 1 presents the participants’ demographic characteristics, along with their clinical and neural profiles. Overall, participants demonstrated a medium level of CR proxy (CRI-q score > 85), and exhibited high levels of both global cognitive functioning and ToM abilities.

CR hypothesis

Correlations

To test the CR hypothesis, bivariate correlations were conducted between the ToM performance (Yoni ACC score) and neural integrity (measured through the ToM networks volume and the Total Intracranial Volume); as well as between ToM performance (Yoni ACC score) and experiential factors (CRIq scores).

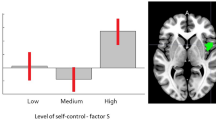

As shown in Fig. 1 (panel A), a statistically significant association emerged between ToM performance and the integrity of the ToM network (r = 0.341, p = 0.009, 95%CI = 0.09–0.55) and particularly with the cognitive execution loop network (r = 0.420, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 0.18–0.61, pFDR = 0.004). By contrast, no significant association emerged between ToM performance and the Total Intracranial Volume (r = 0.061, p = 0.598, 95%CI = −0.20-0.32). A partial correlation analysis (controlling for age) revealed a significant association between ToM performance and experiential factors, as indicated by the CRIq total score (r = 0.296, p = 0.027, 95% CI = 0.03–0.51) (Fig. 1, panel B). Specifically, significant associations were found for CRI-q Working Activity (r = 0.271, p = 0.043, 95%CI = 0.01–0.49, pFDR = 0.067) and Leisure Time (r = 0.270, p = 0.045, 95%CI = 0.01–0.49, pFDR = 0.067) subscores.

As a supplementary analysis, the CRI-q index, and especially the CRI-q Education subscore, was significantly associated with global cognitive level (MoCA score) (partial correlations controlling for age as a covariate between CRI-q and MoCA: r = 0.350, p = 0.008, 95%CI = 0.98 − 0.56; CRI-q Education and MoCA: r = 0.347, p = 0.009, 95%CI = 0.095–0.56, pFDR = 0.033). No statistically significant correlation was observed between the global cognitive level and the Total Intracranial Volume.

Multiple regression models

We conducted a multiple regression analysis testing on the predictive role of neural integrity and CRI-q on the ToM performance. Predictors were entered hierarchically in two blocks (first block: age, sex, neural integrity; second block: age, sex, neural integrity, CRI-q score).

CR hypothesis: total intracranial volume, experiential factors, and ToM performance

When testing the CR hypothesis using Total Intracranial Volume as brain reserve index, the two models showed low R2 values and differed significantly from each other (F = 4.09, p = 0.048), with only the second model approaching statistical significance. In particular, only the CRI-q total score, rather than neural integrity, emerged as a significant predictor of ToM performance (see Table 2).

CR hypothesis: ToM networks, experiential factors, and ToM performance

By testing the CR hypothesis including the ToM network as a brain reserve index, two statistically significant models were obtained (Model 1: p = 0.036; Model 2: p = 0.005), which differed significantly from one other (F = 6.50, p = 0.014), with a higher R2 in the second model than in the first (R2 = 0.243 vs. R2 = 0.148). The ToM network was the only predictor of ACC in the first model (p = 0.035), while both the ToM network (p = 0.009) and the CRI-q total score (p = 0.013) significantly predicted the ACC score in the second model. A higher volume of the ToM circuit and more cognitively stimulating activities accumulated across the lifespan (CRI-q total) were associated with better ToM performance (see Table 3).

The analysis was then replicated using CRI-q sub-indices, separately entering CRI-q Education, CRI-q Working Activity, and CRI-q Leisure Time in the second block (first block: age, sex, ToM network index; second block: age, sex, ToM network index, Cri-q Education, Cri-q Working Activity, Cri-q Leisure Time). Results showed a predictive effect of CRI-q Leisure Time (p = 0.036) and CRI-q Working Activity (p = 0.047) on ToM performance, whereas CRIq Education was not a significant predictor (p = 0.578) (see Table 4).

Then, the multivariate regression was conducted by considering separately the four ToM circuits (First block: age, sex, the core ToM network, the limbic-paralimbic network, the cognitive execution loop, and the affective execution loop; Second block: age, sex, the core ToM network, the limbic-paralimbic network, the cognitive execution loop, and the affective execution loop, CRI-q total). A significant effect of the cognitive execution loop integrity on ToM performance was observed in the first model (p = 0.020), although the overall model did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.098). The second model, by contrast, was statistically significant (p = 0.016) and identified both the cognitive execution loop integrity (p = 0.014) and the CRI-q total score (p = 0.012) as predictors of ToM performance (see Table 5).

As an additional analysis, we tested the role of different ToM circuits and the CRI-q total score on specific ToM components (i.e., affective ToM score and cognitive ToM score) and levels (i.e., first-order ToM score and second-order ToM score). An effect of both ToM circuit integrity and CRI-q was found only for a specific ToM component (i.e., cognitive ToM) and level (i.e., second-order ToM). More specifically, cognitive ToM was predicted by cognitive execution loop integrity and CRI-q total score (R2 = 0.238, p = 0.006; see Supplementary Materials, S1), and second-order ToM was influenced by the same predictors (R2 = 0.252, p = 0.004; see Supplementary Materials, S2). Conversely, neither the cognitive reserve proxy nor ToM neural integrity showed effect on affective or first-order ToM scores.

Finally, the mediating role of the CR proxy on the link between ToM network integrity and the ToM performance was tested. The results confirmed the mediation hypothesis: a significant indirect effect on ToM performance, suggesting that CRI-q mediated the relationship between ToM network integrity and ToM performance (Table 6; Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study aimed to disentangle the relationship between experiential factors and social cognition by adopting a multi-component operationalization of cognitive reserve (CR). A group of healthy adults underwent a neuropsychological evaluation, a MRI scanning, and a retrospective interview on mentally stimulating experiences accumulated across their lifespan, in order to examine the associations among brain status, experiential factors, and social cognition abilities.

The first question we addressed was " Do cognitively stimulating experiential factors, such as education, working activities, and leisure time, mediate the link between neural integrity and complex social cognition ability in healthy adults?“. Our findings supported the predictive role of both experiential factors and brain status (i.e., ToM hardware) in ToM performance (i.e., ToM software). Notably, when further exploring whether and to what extent the effect of brain status on mentalizing abilities was explained by the lifespan experience, we observed a mediating effect of experiential factors, accounting for 27.3% of the relationship. These findings suggest that engagement in cognitively stimulating activities throughout life contributes to the enhancement and refinement of social cognitive abilities and, plausibly, supports their preservation over time. By remaining mentally active, individuals may enhance the cognitive processes involved in social interaction, such as understanding others’ perspectives and navigating complex social situations. Our results contrast with prior studies that did not find an association between CR proxies and social cognition, such as the contributions of Lavrencic et al.29,30 and Guerrini et al.31. This discrepancy may be partially explained by differences in the social cognition measures employed. For instance, Lavrencic et al.30 and Guerrini et al.31 used measures of emotion recognition and perception to test the role of CR proxies on social cognition. In contrast, our study adopted a multidimensional assessment of ToM, a complex domain of social cognition. In particular, the Yoni task evaluates performance across multiple components (affective and cognitive), and levels (first- and second-order) of ToM. This comprehensive approach aligns with the extended network model of ToM correlates6, which distinguishes between cognitive and affective ToM neural pathways. Interestingly, our findings revealed a prominent role of the cognitive execution loop in supporting both second-order ToM level and the cognitive ToM component. Given our focus on the relationship between cognitively stimulating (including both social and non-social) activities and social interactions mental operations, it is plausible that neural circuits usually involved in complex cognitive tasks act as a functional buffer. Indeed, the cognitive loop network supports both ToM and executive function. In this regard, this neural buffer likely bears everyday complex social cognitive operations, such as the ones related to the second-order ToM ability. The predominant involvement of cognitive ToM may reflect the nature of our CR proxy tool, which assesses engagement in global cognitive-stimulating activities, rather than exclusively social ones. It is plausible that focusing more specifically on social reserves might reveal stronger association with the affective ToM.

The second question we explored was “Does a specific domain of lifetime experiential factors (education, work, leisure time activities) best explain the link between social cognition ability and brain integrity?”. Interestingly, and in contrast with previous studies32,33, we did not observe a significant role of educational attainment in predicting social cognition. Instead, our results highlighted a specific predictive role of cognitively demanding working experiences and mentally stimulating leisure activities on ToM performance. These findings suggest that social cognition abilities may be more strongly influenced by experiences accrued during middle and late adulthood, rather than early-life CR proxies34. In adulthood, both work and leisure experiences represent modifiable lifestyle factors, differently from educational attainment, which is generally earlier in life and less amenable to change. The work of Yang et al.35 identified reduced late-life leisure activity as a marker of Mild Cognitive Impairment, suggesting that continued engagement in such activities might help prevent age-related cognitive decline.

Given the inherently social nature of many adult work and leisure experiences, it is plausible that these activities will likely offer opportunities for social interaction that can help stimulate and enhance social cognitive skills. In particular, high levels of occupational complexity may be linked to leadership or coordination roles, which rely on and reinforce social skills. Likewise, extensive leisure activity may involve participation in socially enriching contexts, such as dinners or lunches with friends, book clubs, volunteering, and travels. Previous studies have supported an association between social isolation and poorer cognitive functions36. However, it is worth noting that the questionnaire used to evaluate CR proxies in this study was not specifically designed to cognitively stimulating social activities. Future research may benefit from employing measures focused explicitly on lifetime social engagement, to more precisely evaluate the relationship between social activities exposure on social cognition performance.

Finally, we examined the third research question: “Does fine-grained (social cognition network volume) compared to coarse-grained (total intracranial volume) neural index best operationalize brain status in this CR model?”. By testing both total intracranial volume and specific ToM neural networks volumes in our multi-component CR model, we found that only the domain-specific neurocognitive index was significantly associated with ToM performance. This finding aligns with prior literature highlighting the central role of the neural hubs we included, regions consistently implicated in mentalizing processes. Although the total intracranial volume is among the most widely used indicators of brain reserve (see van Loenhoud et al.19 for a review), it offers limited sensitivity in detecting age-related brain changes over a lifetime in areas specifically involved in social cognition. In fact, previous work has emphasized the need for more refined, theory-driven measures of brain reserve that better reflect domain-specific functions19. In the framework of social cognition, our findings support the adoption of a region-of-interest approach focusing on networks explicitly associated with neuro-social processing. In particular, the model proposed by Shamay-Tsoory et al.37,38 posits that cognitive ToM is a prerequisite for affective ToM, assigning a foundational role of the former. Based on this perspective, cognitive ToM may serve as a key component with a prominent role in its neural correlates as mentalizing hardware in healthy adults. Conversely, in older age, as suggested by previous works39,40, the role of cognitive and affective ToM may be switched. In fact, it has been suggested that when cognitive ToM declines, affective ToM may assume a compensatory function, preserving aspects of social cognition. We might argue that distinct CR mechanisms are implied in adult lifespan. A future study investigating the CR model, with a tri-component perspective (brain, experiential factor, cognition), in young and older people may confirm this hypothesis.

Moreover, social cognition abilities may play a key role in various clinical conditions, serving as a potential signature of the disease, as seen in in Multiple Sclerosis41,42, Parkinson’s Disease43, and Alzheimer’s Disease44. In these populations, the contribution of cognitive reserve, as well as long-term social exposure, remains underexplored, nor is the role of reserve in cognitive rehabilitation. In this direction, social reserve may act as a protective factor against cognitive decline and potentially enhance the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions.

This study is not without limitations. Firstly, we included young and middle-aged healthy adults, and therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution and cannot be generalized to older or clinical populations. Similarly, we focused exclusively on one component of social cognition, the ToM, without addressing other relevant domains, such as insight and emotion recognition. Future works adopting a broader assessment of social cognition are warranted to validate and extend these findings. Another limitation concerns the educational background of our sample, which presented a relatively high education level, with few participants having only a middle-school education, and a prominence of individuals with high-school diploma. However, this demographic distribution reflects national education statistics in Italy, where approximately 80% of the adult population holds at least a high-school qualification45. Moreover, the study employed a cross-sectional rather a longitudinal design, which limits causal interpretations and restricts the generalizability of the findings over time. Finally, the sample size was relatively small, particularly for analyses involving sub-scores (e.g., CRI-q sub-scores and ToM sub-networks). Future research should confirm these findings in a larger and more diverse populations.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the role of life experiential factors on social cognition, with a mediating effect on the link between the ToM brain network status and performance in healthy adults. Future studies may explore the clinical impact of this relationship on cognitive impairment, preventive measures, personalized medicine and rehabilitation strategies.

Methods

This is a prospective study conducted at the IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi ONLUS (Milan). The study was reviewed and approved by the Fondazione Don Gnocchi Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the revised guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Participants

Healthy subjects were enrolled in the research. They were volunteers who worked in the IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi ONLUS as research and administrative staff or who accessed the institute as patients’ caregiver. They were considered eligible as study participants whether they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) age ≥ 18; (ii) absence of neurologic and/or major psychiatric conditions; (iii) absence of hearing and/or visual impairment able to impact the behavioral assessment; (iv) absence of MRI contraindications (i.e., pacemaker, metal implants, crystalline surgery in the last month, etc.). The inclusion criteria were carefully assessed during a clinical interview, that investigated remote and current pathologies, surgery operations, pharmacological treatment, and MRI examination eligibility. All participants read and signed the written informed consent.

Procedure

The study participation included a neuropsychological evaluation and a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) exam (3 Tesla Siemens PRISMA scanner). The order participants were administered neuropsychological assessment and MRI examination was counterbalanced. Subjects were involved in research in an individual session lasting approximately 1 h and a half.

Materials

Neuropsychological evaluation

The neuropsychological battery included the following measures:

-

The Yoni-48 task20 to assess ToM performance using a comprehensive multi-component approach to social cognition: affective ToM, cognitive ToM, first-order ToM, and second-order ToM were evaluated using the same visual-spatial stimuli. Particularly, stimuli consist of colored cartoon-like pictures in which a face (Yoni) is at the center of the screen surrounded by elements (fruits, animals, means of transport, or other faces). Yoni refers to one of the elements with a specific gaze direction and/or facial expression. Each stimulus provides an instruction (e.g., “Yoni loves…” for first-order affective ToM items; “Yoni is thinking of…” for first-order cognitive ToM items”; “Yoni is thinking about the fruit that … wants” for second-order cognitive ToM items; “Yoni loves the fruit that … wants” for second-order affective ToM items). A global standardized accuracy score (ACC, range 0–1, the higher the score, the greater the performance) was computed according to Isernia et al.20 instructions. Additionally, separate scores for affective ToM, cognitive ToM, first-order ToM, and second-order ToM accuracy were computed20.

-

The Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire (CRI-q12), as a CR proxy, measuring cognitive-stimulating activities accrued during the life-span: both CRI-q total index and sub-scores on working, leisure time, and education activities (CRI-q Working Activity, CRI-q Leisure Time, CRI-q Education) were extracted;

-

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA21 to evaluate the global cognitive level and exclude eventual cognitive impairment conditions.

MRI exam

The MRI acquisition protocol included a T1-3D (MPRAGE, isotropic resolution: 0.8 mm3, TR/TE: 2,300/3.1, FOV: 256 × 240 mm) sequence to study the brain morphometry, the FLAIR (resolution: 0.4 × 0.4 × 1 mm3, TR/TE, 5,000/394 ms, FOV, 256 × 230 mm) sequence to evaluate white matter hyper-intensities, and a T2-weighted sequence to exclude gross brain abnormalities. The white matter hyperintensities were manually segmented on the FLAIR image by an experienced operator using a semi-automatic tool (Jim, https://www.xinapse.com/)22. Then, the T1-3D images were lesion-filled and analyzed using the recon-all pipeline of Freesurfer software (v. 6.0) to extract morphometric data. Quality controls were performed23, and manual corrections were performed when necessary. Brain parcellation was performed according to Desikan et al.24 and Fischl et al.25 atlases to extract brain volumes in cortical and subcortical areas respectively. Data extracted for second-level statistics were total intracranial volume (TIV, mm3) and ToM neural hubs’ volumes (mm3): supramarginal, inferiorparietal, precuneus, posterior cingulate, banks superior temporal, temporal pole, caudal anterior cingulate, pars orbitalis, caudal middle frontal, rostral middle frontal, and medial orbital frontal, amygdala, caudate, and putamen volumes (mm3). Based on previous works26,27,28, these parcels were summed up to obtain a composite ToM network index (parcels were summed and normalized by TIV), the core ToM network (sum of the supramarginal, inferiorparietal, precuneus, posterior cingulate, banks superior temporal normalized by TIV), the limbic-paralimbic network (sum of the temporal pole, caudal anterior cingulate , caudate, putamen, amygdala normalized by TIV), the cognitive execution loop (sum of the caudal middle frontal and rostral middle frontal normalized by TIV), the affective execution loop (sum of the medial orbital frontal and pars orbitalis normalized by TIV).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using Jasp software (0.18.3. version, retrieved from https://jasp-stats.org/).

The normal distribution of variables was evaluated by inspecting quantile-quantile plots and histograms. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, and 95% confidence intervals, were extracted to explore the participants’ demographic characteristics and cognitive and neural profiles.

To test the CR hypothesis, correlations were run between experiential factors (CRIq scores), ToM performance (Yoni-48 score), and neural integrity (coarse-grained brain reserve index: TIV; social cognition fine-grained brain reserve index: ToM networks’ volumes). False Discovery Rate (FDR) multiple comparison correction was adopted when subindexes (such as the CRIq sub-scores) were included in the analysis. Then, multiple regression models were run to test the predictive role of neural integrity and experiential factors on the ToM performance. Finally, a mediation analysis was performed to explore the mediating role of the experiential factors on the link between neural integrity and ToM performance, using the bootstrap method to enhance results reliability. A type I error = 5% threshold was set to observe statistically significant results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arioli, M., Crespi, C. & Canessa, N. Social cognition through the lens of cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Biomed Res Int 2018, 4283427. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4283427 (2018).

Sachdev, P. S. et al. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.181 (2014).

Baglio, F., Marchetti, A. & Editorial When (and How) is theory of Mind useful? Evidence from Life-Span research. Front. Psychol. 7, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01425 (2016).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. & Aharon-Peretz, J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective theory of mind: a lesion study. Neuropsychologia 45, 3054–3067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.021 (2007).

Duval, C., Piolino, P., Bejanin, A., Eustache, F. & Desgranges, B. Age effects on different components of theory of Mind. Conscious. Cogn. 20, 627–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.10.025 (2011).

Abu-Akel, A. & Shamay-Tsoory, S. Neuroanatomical and neurochemical bases of theory of Mind. Neuropsychologia 49, 2971–2984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.07.012 (2011).

Stern, Y. et al. A framework for concepts of reserve and resilience in aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 124, 100–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2022.10.015 (2023).

Stern, Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 8, 448–460 (2002).

Valenzuela, M. J. & Sachdev, P. Brain reserve and cognitive decline: a non-parametric systematic review. Psychol. Med. 36, 1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291706007744 (2006).

Di Tella, S. et al. Cognitive reserve proxies can modulate motor and non-motor basal ganglia circuits in early parkinson’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-023-00829-8 (2023).

Isernia, S. et al. Exploring cognitive reserve’s influence: unveiling the dynamics of digital telerehabilitation in parkinson’s disease resilience. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01113-9 (2024).

Nucci, M., Mapelli, D. & Mondini, S. Cognitive reserve index questionnaire (CRIq): a new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 24, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.3275/7800 (2012).

Harrison, S. L. et al. Exploring strategies to operationalize cognitive reserve: A systematic review of reviews. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 37, 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2014.1002759 (2015).

Pinto, J. O., Peixoto, B., Dores, A. R. & Barbosa, F. Measures of cognitive reserve: an umbrella review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 38, 42–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2023.2200978 (2024).

Valenzuela, M. J. et al. Cognitive lifestyle in older persons: the population-based Sydney memory and ageing study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 36, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-130143 (2013).

Castano, E., Martingano, A. J. & Perconti, P. The effect of exposure to fiction on attributional complexity, egocentric bias and accuracy in social perception. PLoS One. 15, e0233378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233378 (2020).

Kidd, D. C. & Castano, E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of Mind. Science 342, 377–380. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918 (2013).

Machado, R. et al. Protective effects of cognitive and brain reserve in multiple sclerosis: differential roles on social cognition and ‘classic cognition’. Mult Scler. Relat. Disord. 48, 102716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102716 (2021).

van Loenhoud, A. C., Groot, C., Vogel, J. W., van der Flier, W. M. & Ossenkoppele, R. Is intracranial volume a suitable proxy for brain reserve? Alzheimers Res. Ther. 10, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0408-5 (2018).

Isernia, S., Rossetto, F., Shamay-Tsoory, S., Marchetti, A. & Baglio, F. Standardization and normative data of the 48-item Yoni short version for the assessment of theory of Mind in typical and atypical conditions. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1048599. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.1048599 (2022).

Conti, S., Bonazzi, S., Laiacona, M., Masina, M. & Coralli, M. V. Montreal Cognitive Assessmen (MoCA)-Italian version: regression based norms and equivalent scores. Neurol Sci. 36, 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-10014-11921-10073 (2015).

Battaglini, M., Jenkinson, M. & De Stefano, N. Evaluating and reducing the impact of white matter lesions on brain volume measurements. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 2062–2071. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21344 (2012).

Klapwijk, E. T., van de Kamp, F., van der Meulen, M., Peters, S. & Wierenga, L. M. Qoala-T: A supervised-learning tool for quality control of freesurfer segmented MRI data. Neuroimage 189, 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.014 (2019).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31, 968–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 (2006).

Fischl, B. et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 33, 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x (2002).

Isernia, S. et al. Resting-state functional brain connectivity for human mentalizing: biobehavioral mechanisms of theory of Mind in multiple sclerosis. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 17, 579–589. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab120 (2022).

Isernia, S. et al. Theory of Mind network in multiple sclerosis: A double Disconnection mechanism. Soc. Neurosci. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2020.1766562 (2020).

Isernia, S. et al. Human reasoning on social interactions in ecological contexts: insights from the theory of Mind brain circuits. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1420122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2024.1420122 (2024).

Lavrencic, L. M., Kurylowicz, L., Valenzuela, M. J., Churches, O. F. & Keage, H. A. Social cognition is not associated with cognitive reserve in older adults. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 23, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2015.1048773 (2016).

Lavrencic, L. M., Churches, O. F. & Keage, H. A. D. Cognitive reserve is not associated with improved performance in all cognitive domains. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult. 25, 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2017.1329146 (2018).

Guerrini, S., Hunter, E. M., Papagno, C. & MacPherson, S. E. Cognitive reserve and emotion recognition in the context of normal aging. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 30, 759–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2022.2079603 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Aging of theory of mind: the influence of educational level and cognitive processing. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 715–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.673724 (2013).

Salas, N., Escobar, J. & Huepe, D. Two sides of the same coin: fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence as cognitive reserve predictors of social cognition and executive functions among vulnerable elderly people. Front. Neurol. 12, 599378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.599378 (2021).

Liu, Y., Lu, G., Liu, L., He, Y. & Gong, W. Cognitive reserve over the life course and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 16, 1358992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2024.1358992 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Contributions of early-life cognitive reserve and late-life leisure activity to successful and pathological cognitive aging. BMC Geriatr. 22, 831. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03530-5 (2022).

Evans, I. E. M. et al. Social isolation, cognitive reserve, and cognition in healthy older people. PLoS One. 13, e0201008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201008 (2018).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Harari, H., Aharon-Peretz, J. & Levkovitz, Y. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in affective theory of Mind deficits in criminal offenders with psychopathic tendencies. Cortex 46, 668–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2009.04.008 (2010).

Sebastian, C. L. et al. Neural processing associated with cognitive and affective theory of Mind in adolescents and adults. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsr023 (2012).

Rossetto, F. et al. Social cognition in rehabilitation context: Different evolution of affective and cognitive theory of mind in mild cognitive impairment. Behav Neurol 2020, 5204927. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5204927 (2020).

Rossetto, F. et al. Affective theory of Mind as a residual ability to preserve mentalizing in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A 12-months longitudinal study. Front. Neurol. 13, 1060699. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.1060699 (2022).

Rossetto, F., Isernia, S., Smecca, G., Rovaris, M. & Baglio, F. Time efficiency in mental state reasoning of people with multiple sclerosis: the double-sided affective and cognitive theory of Mind disturbances. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2024.2446026 (2024).

Chalah, M. A. & Ayache, S. S. Deficits in social cognition: an unveiled signature of multiple sclerosis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 23, 266–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617716001156 (2017).

Palmeri, R. et al. Nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson disease: A descriptive review on social cognition ability. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 30, 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988716687872 (2017).

Demichelis, O. P., Coundouris, S. P., Grainger, S. A. & Henry, J. D. Empathy and theory of Mind in alzheimer’s disease: A Meta-analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 26, 963–977. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617720000478 (2020).

Report, I. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/127792.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who take part in the research. They also acknowledge the financial support of the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente program 2025-2027, project ID: RRC-2025-3686061; and 5x1000 program)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SI: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft; FR: Data curation, Writing- review & editing; GS: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing; AP: Writing- review & editing; FB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Isernia, S., Rossetto, F., Smecca, G. et al. Experiential factors mediate the link between brain status and theory of mind in building-up cognitive reserve. Sci Rep 15, 37491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22531-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22531-z