Abstract

How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact mental health across different (a) pandemic stages, (b) mental-health aspects, (c) people, and (d) life circumstances? Answering these questions will identify ongoing mental health needs and could inform mitigation strategies for future large-scale stressors. However, answers to these questions remain elusive because studies have often focused on a single, early stage of the pandemic (without appropriate pre-pandemic baselines) or single facets of mental health. This preregistered, multisite study addressed these gaps by examining clinical symptoms (depressive and anxiety) and well-being (life satisfaction) among emerging adults in college (primarily first-year students) from shortly before the pandemic (Fall 2019) through initial (Spring 2020) (N = 760) and later (Fall 2020) stages (n = 194), and the role of sociodemographic factors and life circumstances. Though depressive symptoms were stable overall, they increased among White, but not Asian, participants. Anxiety symptoms initially decreased but later returned to pre-pandemic levels. Life satisfaction was initially stable but later decreased, particularly for participants negatively impacted by the pandemic. Socioeconomic status, gender, and COVID-19 virus risk did not predict mental-health impacts. Thus, at least in our sample, resilience was common, but mental-health impacts varied across pandemic stages, mental-health aspects, some sociodemographic factors, and life circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was a “unique, compounding, and multidimensional stressor” that upended peoples’ lives and persisted for years1. Understanding how, why, and whose mental health was affected throughout the pandemic and beyond is crucial for at least three reasons. First, it will provide insight into which aspects of mental health (e.g., clinical symptoms, well-being, or both) were affected and how, thus providing nuanced insights into the pandemic’s impacts. Second, it will provide insight into the time course of people’s responses and mental health throughout the pandemic, thus revealing whether vulnerabilities were temporary or sustained. And third, it will help identify ongoing mental health needs and inform approaches to mitigate the impact of future large-scale stressors. For example, mental health disorders and their common recurrence2,3 substantially contribute to global disease, disability, and undermine peoples’ daily functioning4,5, thereby creating significant burdens and costs for people and, ultimately, societies6,7. Thus, understanding who was impacted, how and why they were impacted, and the extent of those impacts across multiple stages of the pandemic will reveal who might remain vulnerable in the post-pandemic world and inform ways to better protect people and societies against future large-scale stressors.

However, to accurately gauge the pandemic’s mental health impacts, mental health during the pandemic needs to be compared to mental health that was assessed as close to, but prior to the initial COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020 (at least among North American populations) as well as across multiple stages of the pandemic and different facets of mental health (e.g., clinical symptoms and well-being). Given the unexpectedness of the pandemic, only a small subset of studies satisfy the former requirement8,9,10,11,12,13 and even fewer have examined multiple stages of the pandemic and multiple facets of mental health. For example, numerous studies examining children and adolescents compared mental health (largely depressive and anxiety symptoms) during the pandemic to mental health measured up to six years before March 2020 with the latest measurement occurring almost two years before14,15,16,17. Similar assessments of pre-pandemic mental health (most focusing on clinical symptoms) characterize studies examining emerging adults18,19,20,21, adults22, and older adults23. Because mental health can fluctuate over time, across critical developmental stages (e.g., adolescence, puberty) and life events and milestones (e.g., losing jobs, marriage), and facets of mental health, we cannot be certain that the pre-pandemic mental health assessment in these studies can be confidently claimed as an accurate or true “baseline”. Further, we also cannot draw strong insights into whether any observed impacts were temporary or sustained due to them generally only examining one specific pandemic stage and one facet of mental health.

The present, preregistered investigation (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MWDKF) addressed these critical limitations by using a multisite approach to examine the pandemic’s mental health impacts on North American emerging adults in college over multiple stages of the pandemic, across clinical symptoms and well-being, and for different subpopulations and life circumstances. We examined emerging adults because their risk of developing mental health disorders is particularly high24,25,26,27, and worrisome declines in their mental health have been observed over the past decade28,29,30. We examined those in college because university closures also prevented this population from easily accessing campus mental health resources and engaging in a variety of social relationships that foster their mental health31,32. These heightened vulnerabilities among emerging adults in college underscore the critical need to deepen our understanding of how they were impacted by the pandemic. Importantly, we measured pre-pandemic mental health relatively close to the pandemic’s onset (assessed between August 2019 and February 2020). Our study, therefore, extends the small subset of studies using a relatively accurate pre-pandemic mental health assessment to examine North American emerging adults in college10,33 while simultaneously being the first to examine multiple stages of the pandemic (Spring 2020 & Fall 2020) among this population. This latter and novel contribution enabled us to examine whether initial mental health impacts were temporary or persisted. We next review literature relevant to emerging adults and our research questions.

Given the paucity of studies that examined emerging adults with a relatively accurate pre-pandemic assessment of mental health, research among all populations is relevant. Several reviews that examined studies with pre-pandemic mental health assessments (measured at any point prior to the pandemic) indicate that mental health generally worsened during the pandemic’s initial stages (i.e., first few months) among people globally34,35,36,37. This research, however, also indicates that individuals varied in their degree of resilience and vulnerability. Specifically, among North American adolescents, college students, and young and middle-aged adults, Asian (vs. White) people, interestingly, had less adverse mental-health impacts12,16,33,38 despite some studies indicating that the mental health of Asian people was negatively impacted during this time due to being targets of ethnic discrimination38. Further, people with lower (vs. higher) socioeconomic status12, women (vs. men)12,16,33, and people with more (vs. less) negative life circumstances (e.g., negative work/social life changes, exposure/vulnerability to the COVID-19 virus)15,17,34 had more adverse mental-health impacts.

An additional nuance of the pandemic’s impacts that we do not yet fully understand lies in how sustained its initial impacts were. For example, a review by Robinson et al.36 examined 65 longitudinal studies that compared post- to pre-pandemic mental health measured any time before the pandemic. They found that although mental health worsened between March and April 2020, it rebounded to pre-pandemic levels between May and July 2020. However, given that May through July 2020 was still a relatively early stage of the pandemic and many of Robinson et al.’s36 studies and others39 measured pre-pandemic mental health years before the pandemic, it is difficult to make confident conclusions about how mental health changed across different pandemic stages relative to pre-pandemic levels. Another review of 28 studies by Schäfer et al.40 examined whether initial mental health impacts were sustained into 2021. Their results extended those of Robinson et al.36 by indicating that the pandemic’s initial impacts were generally not sustained into 2021, but because only 28.6% of their studies included a pre-pandemic assessment of mental health, their results do not provide clear insights into whether mental health returned to pre-pandemic levels. Willroth et al.12 addressed some of the noted limitations of these reviews and observed results that generally were consistent with them. Specifically, they found that, compared to pre-pandemic levels measured just prior to pandemic’s initial outbreak, negative emotions increased and positive emotions decreased among U.S. adults during the initial stages. However, in a display of resilience, negative emotions decreased to pre-pandemic levels shortly after and remained there through their last assessment in September 2020. Positive emotions increased and similarly persisted, but they did not return to pre-pandemic levels. Still, because the results of Willroth et al.12 are specific to emotional experiences, their results might not extend to other facets of mental health such as clinical symptoms or life satisfaction judgments. For example, studies conducted in Europe that examined clinical symptoms and life satisfaction found that mental health during Fall 2020 was worse among Dutch adolescents (vs. levels reported between October 2019 and January 2020)13 and U.K. older adults (vs. levels reported in 2018 and 2019)23. Although these discrepant results could relate to pandemic rules governing people’s social lives varying across countries41, a recent study by Reutter et al.22 was consistent with Willroth et al.12 resilience trajectories insofar as they observed an initial increase of anxiety during the pandemic’s initial stages (vs. levels reported between June 2013 and March 2020) followed by a decrease in anxiety during Fall 2021 among German adults.

Taken together, we know that the pandemic impacted mental health generally, and that these impacts likely varied across stages of the pandemic, different aspects of mental health, and different people and life circumstances. Yet, important empirical gaps remain. First, we do not fully understand how the pandemic impacted people’s mental-health trajectories from before and across multiple stages of the pandemic, especially later ones, and among North American emerging adults in college. Second, we do not fully understand how the pandemic impacted different aspects of mental health, including clinical symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms) and well-being (e.g., life satisfaction)42,43. Third, we do not fully understand whether and how these changes varied across different people and life circumstances during later pandemic stages.

This preregistered study (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MWDKF) addressed these gaps by examining the mental health of primarily first-year emerging adult students enrolled at five North American universities (N = 760). To better understand how the pandemic impacted mental health trajectories across the pandemic, we examined participants’ mental health shortly before the pandemic (T1; measured between August 2019 and February 2020), through the initial stages (T2; April/May 2020) and, in a subset of participants (n = 194) at two universities, a later stage (T3; Fall 2020). This design allowed us to test linear and non-linear changes in mental health (e.g., decreases followed by a rebound). To better understand how the pandemic impacted different aspects of mental health, we examined clinical symptoms (depressive and anxiety symptoms) and well-being (life satisfaction). To better understand how mental health changes varied across different people and life circumstances, we examined whether factors identified as resilience and risk factors in prior research predicted a better or worse mental health trajectory. Specifically, we examined socioeconomic status, ethnicity in terms of Asian vs. White people because these were the largest ethnic groups in our sample, gender (man vs. woman), and pandemic life circumstances (e.g., how much life was negatively impacted by the pandemic such as by losing one’s job, one’s COVID-19 virus exposure risk such as being exposed to the virus or health vulnerabilities).

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations

Descriptive statistics for all measures across the full sample, ethnicity (White, Asian, not White or Asian), and gender (men and women) are reported in Table 1, and Table 2 reports the intercorrelations among all measures across the full sample. Not White or Asian was included as an ethnic group due to the relatively small ethnic samples size of people who were not White or Asian (see demographics reported in Table 3).

Question 1: How did mental health change across the pandemic?

Depressive symptoms

Changes in depressive symptom did not exhibit a linear (β = 0.02, p = 0.220) or quadratic (β = 0.08, p = 0.123) pattern. In other words, depressive symptoms were stable across the pandemic (T1 to T2 β = -0.00, p = 0.921; T2 to T3 β = 0.13, p = 0.056; T1 to T3 β = 0.13, p = 0.062; Fig. 1, Panel A).

Question 1: How Did Mental Health Change Across the Pandemic? T1 = August 2019-February 2020; T2 = April/May 2020; T3 = Fall 2020; No = the referenced effect was not significant; Yes = the referenced effect was significant; Error bars reflect 95% confidence interval of the mean. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Anxiety symptoms

Changes in anxiety symptoms did not exhibit a linear pattern (β = -0.03, p = 0.097) but they did exhibit a positive quadratic pattern (β = 0.17, p = 0.001; Fig. 1, Panel B). Specifically, anxiety symptoms decreased from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.13, p = 0.001) and increased from T2 to T3 (β = 0.16, p = 0.020) such that they returned to T1 levels (β = 0.03, p = 0.705).

Life satisfaction

Changes in life satisfaction exhibited a negative linear (β = -0.06, p < 0.001) and quadratic (β = − 0.14, p < 0.001) pattern (Fig. 1, Panel C). Specifically, although life satisfaction did not change from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.03, p = 0.326), it decreased from T2 to T3 (β = − 0.26, p < 0.001) to lower levels than T1 (β = − 0.29, p < 0.001).

Question 2: Did mental health changes depend on sociodemographic factors or pandemic life circumstances?

Table 3 reports whether linear mental health changes from before and across the pandemic depended on (i.e., whether there were significant interactions) sociodemographic factors and/or life circumstances. Figure 2 visually depicts significant interactions. The interaction effect sizes reported in Table 4 were largely unaffected when controlling for mental health before the pandemic (T1; see Methods for additional information), indicating that T1 mental health differences across levels of our sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances did not account for the results reported below.

Question 2: Mental-Health Changes Across the Pandemic Depended on Ethnicity (White vs. Asian; Panels 1A-1B) and Negative Life Impacts (Less vs. More; Panels 2A-2B) Note. T1 = Before Pandemic (August 2019-February 2020); T2 = Pandemic’s initial stages (April/May 2020); T3 = Later pandemic stage (Fall 2020); Error bars reflect 95% confidence interval of the mean. Only significant interactions are depicted here. For results for all interactions, see Table 4. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Results indicated that changes in depressive (β = -0.20, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = − 0.11, p = 0.028) symptoms depended on participants’ ethnicity (White vs. Asian), and changes in anxiety symptoms (β = 0.04, p = 0.039) and life satisfaction (β = − 0.03, p = 0.043) depended on participants’ negative life impacts (i.e., extent their work/professional, family, and finances were impacted by the pandemic). However, mental-health changes did not depend on socioeconomic status, gender, or COVID-19 virus exposure risk. Next, we describe how these factors affected mental-health changes over time.

Ethnicity (White vs. Asian)

Depressive symptoms

Whereas depressive symptoms increased across the pandemic among White participants (β = 0.09, p < 0.001), depressive symptoms decreased among Asian participants (β = − 0.10, p = 0.010) (Fig. 2, Panel 1A). Specifically, among White participants, depressive symptoms increased from T1 to T2 (β = 0.17, p = 0.002) and although symptoms did not change from T2 to T3 (β = 0.07, p = 0.360), symptoms remained higher at T3 than T1 (β = 0.24, p = 0.003). In contrast, among Asian participants, depressive symptoms decreased from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.25, p = 0.001) and although symptoms non-significantly increased from T2 to T3 (β = 0.17, p = 0.326), they returned to T1 levels (β = − 0.08, p = 0.664).

Anxiety symptoms

Whereas anxiety symptoms were stable across the pandemic among White participants (β = 0.01, p = 0.721; T1 to T2 β = 0.01, p = 0.886; T2 to T3 β = 0.06, p = 0.519; T1 to T3 β = 0.05, p = 0.580), anxiety symptoms decreased among Asian participants (β = − 0.12, p = 0.003) (Fig. 2, Panel 1B). Specifically, anxiety symptoms among Asian participants decreased from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.31, p < 0.001) and although symptoms non-significantly increased from T2 to T3 (β = 0.26, p = 0.153), they increased to T1 levels (β = − 0.05, p = 0.764).

Negative life impacts

Simple slope analyses were based on participants with less (− 1SD; n = 102) versus more (+ 1SD; n = 139) negative life impacts.

Anxiety symptoms

Whereas anxiety symptoms decreased across the pandemic among participants with less negative life impacts (β = − 0.18, p < 0.001), anxiety symptoms were stable among participants with more negative life impacts (β = 0.03, p = 0.494; T1 to T2 β = 0.05, p = 0.536; T2 to T3 β = 0.02, p = 0.893; T1 to T3 β = 0.07, p = 0.606) (Fig. 2, Panel 2A). Specifically, among participants with less life impacts, anxiety symptoms decreased from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.37, p < 0.001), did not change from T2 to T3 (β = − 0.06, p = 0.753), and remained lower at T3 than T1 (β = − 0.43, p = 0.029).

Life satisfaction

Whereas life satisfaction was stable across the pandemic among participants with less life impacts (β = 0.01, p = 0.716; T1 to T2 β = 0.09, p = 0.138; T2 to T3 β = -0.17, p = 0.133; T1 to T3 β = − 0.08, p = 0.504), life satisfaction decreased among participants with more life impacts (β = -0.09, p = 0.005) (Fig. 2, Panel 2B). Specifically, among participants with more life impacts, life satisfaction did not change from T1 to T2 (β = − 0.06, p = 0.310), but it decreased from T2 to T3 (β = − 0.28, p = 0.008) such that levels at T3 were lower than T1 (β = − 0.34, p = 0.001).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the mental health of people globally during its initial stages36. However, we need to better understand how, why, and whose mental health was affected beyond the initial stages of the pandemic generally and among particularly vulnerable populations specifically using pre-pandemic mental health assessments that occurred relatively close to the pandemic’s onset and multiple facets of mental health. Thus, we examined mental-health changes (depressive and anxiety symptoms, life satisfaction) among North American primarily first-year emerging adults in college (a particularly vulnerable population) from shortly before the pandemic (August 2019-February 2020) through the pandemic’s initial (April/May 2020) and later (Fall 2020) stages. We next discuss our results and their implications with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic and large-scale stressors more generally.

Overall, our sample of emerging adults were surprisingly resilient across most aspects of mental health, though mental health changes were nuanced insofar as they varied by the pandemic stage, mental-health aspect, and sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances. For example, depressive symptoms were, overall, stable through Fall 2020 (Fig. 1, Panel A), but these changes depended on ethnicity (Fig. 2, Panel 1A). Specifically, whereas depressive symptoms among White participants initially increased and remained elevated during Fall 2020, depressive symptoms among Asian participants initially decreased but returned to pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020. In contrast, anxiety symptoms, overall, initially decreased, but they returned to pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020 (Fig. 1, Panel B). Anxiety symptom changes also depended on ethnicity (Fig. 2, Panel 1B) in addition to negative life impacts (Fig. 2, Panel 2A). Specifically, whereas anxiety symptoms were stable among White participants, anxiety symptoms among Asian participants initially decreased but returned to pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020 (the same pattern as depressive symptoms). Further, among participants with less negative life impacts, anxiety symptoms initially decreased and remained lower than pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020, but symptoms were stable among participants with more negative life impacts. Finally, life satisfaction was, overall, initially stable but decreased below pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020 (Fig. 1, Panel C). However, these changes depended on negative life impacts (Fig. 2, Panel 2B): life satisfaction was stable among participants with less life impacts, and while life satisfaction was initially stable among participants with more life impacts, it decreased below pre-pandemic levels during Fall 2020.

Overall, our results indicate that the pandemic impacted the well-being, but not clinical symptom severity, of our primarily first-year emerging adult college students from before the pandemic through Fall 2020. However, because clinical symptoms captured the past 2 weeks and life satisfaction judgments were global, participants may have had elevated symptoms at points across the pandemic that were missed because of the narrow 2-week reference. In contrast, because life satisfaction during Fall 2020 presumably considered all pandemic negative experiences (e.g., no in-person social events, entirely remote classes), maintaining pre-pandemic life satisfaction was likely very challenging, at least through Fall 2020. This pattern differs from studies on Dutch adolescents13 and U.K. older adults23 in which clinical symptoms and well-being worsened through Fall 2020, but these differences might relate to country-level variations in social life restrictions such as differences in the duration of lockdowns and the scope of social distancing restrictions41.

It is important to consider how characteristics of our sample may have influenced our overall results. First, our sample was primarily comprised of first-year college students. Since beginning college often coincides with independent living and decision making for the first time, and students often need to establish new friends and social networks, first-year students are especially at risk for numerous mental health disorders44,45. These increased mental health risks may have led to artificially low pre-pandemic mental health assessments in our sample, thus increasing the likelihood that our sample’s mental health would “rebound” having been lower to begin with. However, post hoc t-tests indicated that pre-pandemic mental health did not differ between first-year students and all non-first-year students. Thus, the unique challenges associated with first-year students did not result in lower pre-pandemic mental health in our sample. Second, college students generally, and first-year students in particular, could have been “relieved” to some extent to go back home after the pandemic began. This “relief” could explain the stability/rebounding clinical symptom effects we observed. Although we cannot fully rule this explanation out, it seems unlikely because life satisfaction worsened rather than remaining stable at our Fall 2020 follow-up. Further, additional post-hoc analyses indicated that first-year and non-first-year students did not differ in reported changes in anxiety symptoms or life satisfaction from before (T1) to the initial pandemic stages (T2). While reported T1 to T2 changes in depressive symptoms did differ, first-year students reported no change and non-first-year students reported a significant decrease in depressive symptoms. Additionally, as we detail next, sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances moderated some of mental health changes, thus limiting the likelihood of a general “relief” based explanation.

Our results also revealed sociodemographic factors related to resilience and risk trajectories. Specifically, clinical symptoms among Asian participants were not negatively impacted (they even initially decreased), while White participants had sustained increases in depressive symptoms. Our results among our Asian participants are especially interesting when one considers that the mental health of this ethnic group was found to be negatively impacted during this time due to ethnic discrimination38. Because interdependence and family support are generally more central to values typically associated with Asian (vs. White) people46, living with one’s family while campuses were closed may have provided a buffer for our Asian participants generally and compared to White participants. This might also account for similar results among Asian vs. White North American adolescents16, college students33, and adults12, but it is clear that not all Asian people had mental health protections38. Further, more negative life impacts only being a risk factor for decreases in life satisfaction during Fall 2020 is consistent with our earlier suggestion. Specifically, because life satisfaction judgments during Fall 2020 for those with more negative life impacts presumably considered the greatest amount of pandemic negative experiences when making their judgments, it was a tall order for pre-pandemic life satisfaction to be maintained. This suggestion is also consistent with studies that have linked negative mental-health changes to pandemic-related stressors among people in North America12,14,17 and globally9,19,47. Interestingly, mental-health changes did not depend on socioeconomic status, gender, or COVID-19 virus exposure risk. Because similar results have been observed among adolescents, college students, and young adults10,13,14,33, perhaps the economic and social support younger people were afforded by living with their families shielded them from the vulnerabilities that some of these factors imposed on middle-aged and older adults12,36. Although our participants were enrolled at colleges with a history of prestige and wealth, the 6.7/10 sample mean indicates that subjective socioeconomic status was not extremely high and speaks against ceiling effects. In addition, four of our five sampled universities were large public universities, thus increasing the socioeconomic heterogeneity of our sample. Further, we were able to consider financial impacts of the pandemic through our negative life impacts variable in which students were generally negatively impacted by the pandemic (3.4/5 sample mean). This sample mean indicates that our sample was not completely isolated from pandemic-related challenges (i.e., impacts to one’s job, family life, and finances) even if they were considered better off than most, and we did indeed find that this variable (which is partially a function of socioeconomic status) moderated some of the mental health changes across the pandemic. These latter, moderation findings indicate that socioeconomic status did have an influence on mental health changes and highlights the importance of including multiple socioeconomic measures to capture its varying nuances. By measuring pre-pandemic mental health near the pandemic’s onset, we were able to address key limitations of past studies. It also allowed us to extend previous research suggesting that some of the initial negative mental health impacts of the pandemic were not sustained12,36,40 to a particularly vulnerable population—emerging adults in college—during a later pandemic stage (Fall 2020). Additionally, our study is among the first to examine multiple mental-health aspects (clinical symptoms and well-being) and specific North American subpopulations.

Given that resilient mental health trajectories (unchanged or recovery after initial worsening) are common across diverse large-scale and individual stressors48,49, it is perhaps unsurprising that they may have been common during the COVID-19 pandemic as well. However, our findings point to subpopulations of emerging adults that did not display resilience trajectories; for instance, increases in depressive symptoms persisted among White participants, and life satisfaction declined as the pandemic progressed among people will more negative life impacts. These findings underscore the need to examine mental health trajectories throughout the entire pandemic and into the post-COVID world to fully understand its long-term mental health impacts. These findings could also inform ways to mitigate the impacts of future large-scale stressors, at least among college students. For example, universities (or perhaps governments) could communicate messages that because humans are generally resilient, even during previous large-scale stressors, any mental health challenges they are experiencing are likely to be temporary. Such messaging could help individuals positively reappraise their situations and/or believe there is hope for them in the future. Optimistic and hopeful outlooks (when they are realistic and accompanied by tangible support) are linked to beneficial mental health outcomes50. Additionally, given that those who experienced more (vs. less) negative life impacts generally experienced worse mental health changes in our study (e.g., students who worked as frontline workers), mental health outreach and interventions could be more efficient during future large-scale stressors by focusing their efforts on identifying and targeting individuals whose lives put them most at risk.

We note several limitations of our study. First, mental health was not measured explicitly in reference to the pandemic. Since mental health trajectories can vary depending on whether assessments focus on general emotions or pandemic-related emotions12, future research might incorporate both approaches. Second, given that our depression and anxiety measures included only 2–3 items, they were unable to capture all of the symptoms and features characteristic of these disorders. Still, because these measures have been empirically linked to clinician rated symptoms51, they are clinically relevant. Third, although life circumstances during the pandemic’s initial stages influenced some mental health changes, these circumstances likely changed throughout the pandemic, meaning their impact may have varied across time52. Fourth, clinical symptoms in our sample were, on average, only mild to slight in severity and, therefore, might not be representative of populations with more severe clinical symptoms. However, even “subthreshold” clinical levels can be consequential insofar as they are longitudinally linked with worse psychosocial functioning and increased risk of mental health disorder onset53,54. Fifth, given our sample was predominantly White and Asian, it remains unclear how the pandemic impacted the mental health of other racial and ethnic groups in our sample (e.g., Latinx/e, Black). Finally, because there was substantial attrition at our Fall 2020 follow-up (T3), our T3 results could have been biased. However, as detailed in Appendix B of the online supplemental materials, these concerns are somewhat mitigated given that those who did (vs. did not) participate at T3 did not differ (a) on any mental health outcome, (b) in how mental health changed from T1 to T2, and (c) several important sociodemographic factors.

Ongoing concerns about the mental health of emerging adults in college are warranted, yet, our results suggest that, overall, many of our emerging adults were surprisingly resilient across most aspects of mental health. Future work is essential to fully unpack the pandemic’s long-term mental-health impacts over time and across diverse populations, geographical regions, and socioeconomic and life circumstance contexts.

Methods

Participants and procedure

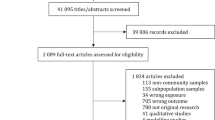

Participants were emerging adults aged 18–25 from five North American universities (University of Colorado, Boulder; University of California, Berkeley; University of British Columbia; Northwestern University; University of California, Irvine) that were part of a larger multi-site study of 1,934 emerging adults (see,55, for additional details related to recruitment procedures and full list of sites). The 794 participants in the current study consented to participating and completed an online survey before the pandemic (T1; August 2019-Februrary 2020) and a second survey during the initial stages of the pandemic (T2; April 2020/May 2020). In addition, a third survey was completed during a later stage of the pandemic (T3; August 2020-December 2020) in a subset of students from two universities (University of Colorado, Boulder and University of British Columbia). Except for University of California, Berkeley in which students of any class year could participate, only first-year students could participate at each of the other four universities. Participants were compensated with course credit or financial compensation for completing each survey. After removing participants who failed multiple attention checks (e.g., choose “4” for this item, write “EMERGE” for this response) at any time point, the final sample comprised 760 participants for T1 and T2 and 194 participants for T3 (see Table 4 for demographic information for the full sample and each university). All participants provided informed consent and were treated in accordance with APA ethical standards and all procedures that were approved by CU Bouler’s IRB.

Although students who did (vs. did not) participate at T3 differed in terms of some sociodemographic factors, they did not differ in terms of pandemic life circumstances or any T1 or T2 mental health measures, and changes in mental health were largely consistent across these two groups of students. This suggests that the influence of attrition/missing data on mental health changes from T2 to T3 as well as T1 to T3 were likely limited. See Appendix B of the online supplemental materials for a detailed description of all group comparisons conducted.

Measures

Mental health (Assessed at T1-T3)

Clinical symptoms

Clinical symptoms were measured with the DSM-5 Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure51. Specifically, depressive [2 items (T1 α = 0.76, T2 α = 0.78, T3 α = 0.80); e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things?”] and anxiety [3 items (T1 α = 0.78, T2 α = 0.82, T3 α = 0.84); e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious, frightened, worried, or on edge?”] symptoms were measured by asking students to indicate how often they’ve been bothered by symptoms over the past two weeks [0 = None (not at all), 1 = Slight (rare, less than a day or two), 2 = Mild (several days), 3 = Moderate (more than half the days), 4 = Severe (nearly every day)]. Items for each symptom were averaged and higher scores reflected greater symptoms, and test–retest reliabilities were adequate (Table 2). The results for anger and mania symptoms (two additional preregistered outcomes) are reported in Appendix C of the online supplemental materials.

Well-being

Well-being was measured with the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale56. Students indicated the extent to which they agreed (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with each item (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) (T1 α = 0.88, T2 α = 0.89, T3 α = 0.88). Items were averaged and higher scores reflected higher life satisfaction and well-being, and test–retest reliabilities were very high (Table 2).

Sociodemographic factors (Assessed at T1)

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status was measured by participants indicating where they stood in terms of their perceived standing in society on a ladder with 10 rungs from 1 (bottom of ladder; lowest perceived socioeconomic status) to 10 (top of ladder; highest perceived socioeconomic status) (McArthur ladder)57.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity was included via two dummy coded variables. Since the largest ethnic group among participants was White (47.6%), White participants were used as the comparison group in each dummy coded variable. Specifically, the first dummy coded variable contrasted White participants to Asian participants (White = 0, Asian = 1) since Asian participants comprised the second largest ethnic group (28.7%). The second dummy coded variable contrasted White participants to all remaining participants who were not Asian or White (23.7%; White = 0, Not Asian/White = 1) since the remaining groups were too small to include as standalone groups (e.g., Latino; n = 53 or 7.0% of sample; Middle Eastern; n = 21 or 2.8% of sample). Although our focus was on White vs. Asian participants, both dummy coded variables were always simultaneously included because this enabled our models to retain the entire sample of participants.

Gender

Gender was coded as Man = 0, Woman = 1 since over 99% of participants denoted one of these two binary gender identities. The remaining 1% of participants reported their gender as nonbinary/trans but were omitted in all models that included gender due to their small sample sizes.

Pandemic life circumstances (Assessed at T2)

Our pandemic life circumstances were based on measures used by Zion et al.58.

Negative life impacts

Negative life impacts were assessed with three items that asked participants the extent to which their 1) work/professional life, 2) personal/family life, and 3) finances were impacted by the coronavirus outbreak (1 = not at all, 5 = a great deal). Items were averaged and higher scores reflected greater life impacts (α = 0.56). Although the alpha reliability coefficient of 0.56 was below our preregistered 0.65 cut-off for averaging the three items, we chose to average them for three reasons. First, averaging the three items reduced the number of tests and the Type I error rate. Second, post-hoc analyses indicated that the effect sizes for each individual item were generally consistent with those observed using the average. Third, averaging the items captured negative life impacts more broadly.

COVID-19 virus exposure risk

A COVID-19 virus exposure risk index was created by summing the total number of “yes” responses in response to seven questions (score range = 0–7) concerning whether participants had personally been diagnosed with COVID (e.g., “Have you been diagnosed with the coronavirus?”), had been exposed to COVID or knew someone who had been exposed (e.g., “Have you come in contact with someone who has a possible or confirmed case of the coronavirus?”), or were part of a high risk population (e.g., “Are you immunocompromised or have other health conditions that would make you at higher risk for the coronavirus?”). Higher scores reflected greater exposure risk.

Data-analytic plan

Though we deviated in minor from our preregistered data-analytic plan, these deviances (1) adjusted the number and phrasing of our research questions, (2) streamlined our analytical procedures, models, and results, and (3) increased the conservatism of our models by controlling for several covariates. All deviances are described and justified in Appendix A of the online supplemental materials.

Linear mixed-effects models were conducted in R (v4.3.3; R Core Team, 2024) using the “lmer4” package59 and standardized betas and p-values were obtained from the “sjPlot” package60. To reveal the unique effects of the pandemic on mental health across time, we controlled for each of our sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances as well as students’ university in all models. Since some of these factors were correlated with whether participants did vs. did not participate at T3 (see Footnote 2), this also controlled for potential missing data bias61. Students’ university was included as four separate dummy coded variables comparing University of Colorado, Boulder (the highest n and coded as 0) to each of the other universities (each coded as 1). Because Little’s missing completely at random test62 indicated that our missing data were missing completely at random (p = 0.615; i.e., not missing systematically), we used maximum likelihood estimation for all models.

Question 1: How did mental health change across the pandemic?

For each mental health outcome, we first coded a linear Time factor as 0, 1, 2 to reflect T1, T2, and T3, respectively, and used the ∆χ2 test to compare a random intercept model to a random slope model. A significant ∆χ2 for life satisfaction, but not depressive nor anxiety symptoms, indicated that the linear life satisfaction change from T1 in T3 varied across participants. We, therefore, included random slopes in all subsequent models for life satisfaction. To assess whether the outcome being examined linearly changed from T1 to T3, we examined the linear Time factor. To assess whether the outcome quadratically changed from T1 to T3, we added a quadratic Time factor that was coded as 0, 1, 4, to reflect T1, T2, and T3, respectively, to our linear Time factor model and examined the quadratic Time factor. We then examined whether the T1 to T2 and T1 to T3 changes were significant by replacing the linear and quadratic Time factors with two dummy coded Time factors (T1 = 0, T2 = 1 and T1 = 0, T3 = 1, respectively) and examining these Time factors. Finally, we examined whether the T2 to T3 changes were significant by recoding the two dummy coded Time factors as T2 = 0, T1 = 1 and T2 = 0, T3 = 1 and examining the latter Time factor.

Question 2: Did mental health changes across the pandemic depend on sociodemographic factors or pandemic life circumstances?

To assess whether mental health changes from before and across the pandemic depended on (i.e., were moderated by) sociodemographic factors or pandemic life circumstances, we added main effects for each sociodemographic factor and pandemic life circumstance as well as separate 2-way interaction terms between the linear Time factor and each of the sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances (i.e., linear Time × Gender + linear Time × Ethnicity + …etc.) to our models that only included a linear Time factor. This conservative model accounted for the significant intercorrelations among some of the sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances (see Table S1), limited inflation of the Type I error rate due to multiple tests relative to if we examined each factor individually and revealed which factors the mental health changes across the pandemic uniquely depended on. However, the results from examining each factor in separate models were generally consistent. Significant interactions were probed by conducting simple slope analyses to examine whether the linear Time factor was significant, respectively, at different levels of the factor involved in the significant interaction. We then examined whether the T1 to T2, T2 to T3, and T1 to T3 mental health changes were significant at each level of the factor using the procedures noted above to examine Question 1 among the full sample. We did not examine whether quadratic changes depended on sociodemographic factors or pandemic life circumstances to ease interpretation and reduce model complexity.

There were some significant mental health differences at T1 across the levels of some our sociodemographic factors and pandemic life circumstances (e.g., Asian > White on T1 depressive and anxiety symptoms, people with more (+ 1SD) vs. less (− 1SD) negative life impacts reported higher T1 anxiety symptoms and lower T1 life satisfaction). Therefore, we reran each of the Question 2 models noted above by including mental health at T1 as a fixed effect to control for mental health differences at T1. Because the effect sizes of the significant interactions reported in Table 4 were generally consistent regardless of whether we controlled for mental health at T1, our results for Question 2 were not due to mental health differences at T1 and we, therefore, report the results from the models not controlling for T1 mental health.

Data availability

All data reported in this manuscript, R code script for our primary analyses, and a full list of variables assessed but not mentioned in this manuscript are available at [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8UB37] (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8UB37).

References

Gruber, J. et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am. Psychol. 76, 409–426 (2021).

Scholten, W. et al. Recurrence of anxiety disorders and its predictors in the general population. Psychol. Med. 53, 1334–1342 (2023).

Hardeveld, F., Spijker, J., De Graaf, R., Nolen, W. A. & Beekman, A. T. F. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 122, 184–191 (2010).

Prince, M. et al. No health without mental health. Lancet 370, 859–877 (2007).

Smith, K. A world of depression. Nature 515, 180–181 (2014).

Christensen, M. K. et al. The cost of mental disorders: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579602000075X (2020).

Knapp, M. & Wong, G. Economics and mental health: The current scenario. World Psychiatry 19, 3–14 (2020).

Evans, S., Alkan, E., Bhangoo, J. K., Tenenbaum, H. & Ng-Knight, T. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Res. 298, 113819 (2021).

Elmer, T., Mepham, K. & Stadtfeld, C. Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 15, 0236337 (2020).

Giuntella, O., Hyde, K., Saccardo, S. & Sadoff, S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, 2016632118 (2021).

Lee, C. M., Cadigan, J. M. & Rhew, I. C. Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 714–717 (2020).

Willroth, E. C. et al. Emotional responses to a global stressor: Average patterns and individual differences. Eur. J. Pers. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070221094448 (2022).

Stevens, G. W. J. M. et al. Examining socioeconomic disparities in changes in adolescent mental health before and during different phases of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Stress. Health 39, 169–181 (2023).

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G. & Nelson, B. D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005358 (2021).

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Olino, T. M., Nelson, B. D. & Klein, D. N. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences; A longitudinal study of youth in New York during the spring-summer of 2020. Psychiatry Res. 298, 113778 (2021).

Barendse, M. E. A. et al. Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Adolesc. 33, 74–91 (2022).

Rosen, M. L. et al. Promoting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 16, 0255294 (2021).

van den Berg, Y. H. M., Burk, W. J., Cillessen, A. H. N. & Roelofs, K. Emerging adults’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective longitudinal study on the importance of social support. Emerg. Adulthood 9, 618–630 (2021).

Wiedemann, A. et al. The impact of the initial COVID-19 outbreak on young adults’ mental health: A longitudinal study of risk and resilience factors. Sci. Rep. 12, 16659 (2022).

Alzueta, E. et al. Risk for depression tripled during the COVID-19 pandemic in emerging adults followed for the last 8 years. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004062 (2021).

Preetz, R., Filser, A., Brömmelhaus, A., Baalmann, T. & Feldhaus, M. Longitudinal changes in life satisfaction and mental health in emerging adulthood during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and protective factors. Emerg. Adulthood 9, 602–617 (2021).

Reutter, M. et al. Mental health improvement after the COVID-19 pandemic in individuals with psychological distress. Sci. Rep. 14, 5685 (2024).

Zaninotto, P., Iob, E., Demakakos, P. & Steptoe, A. Immediate and longer-term changes in the mental health and well-being of older adults in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiat. 79, 151–159 (2022).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Biol. Psychiatry 58, 668–676 (2005).

Kessler, R. C. & Wang, P. S. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 29, 115–129 (2008).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 593–602 (2005).

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R. & Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 569–576 (2014).

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G. & Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Serv. 70, 60–63 (2019).

Oswalt, S. B. et al. Trends in college students’ mental health diagnoses and utilization of services, 2009–2015. J. Am. Coll. Health 68, 41–51 (2020).

Xiao, H. et al. Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychol. Serv. 14, 407–415 (2017).

Lederer, A. M., Hoban, M. T., Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S. & Eisenberg, D. More than inconvenienced: The unique needs of U.S. college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Edu. Behav. 48, 14–19 (2021).

Gruber, J., Hinshaw, S. P., Clark, L. A., Rottenberg, J. & Prinstein, M. J. Young adult mental health beyond the COVID-19 era: Can enlightened policy promote long-term change?. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 10, 75–82 (2023).

Zimmermann, M., Bledsoe, C. & Papa, A. Initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health: A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors. Psychiatry Res. 305, 114254 (2021).

Witteveen, A. B. et al. COVID-19 and common mental health symptoms in the early phase of the pandemic: An umbrella review of the evidence. PLoS Med 20, 1004206 (2023).

Blendermann, M., Ebalu, T. I., Obisie-Orlu, I. C., Fried, E. I. & Hallion, L. S. A narrative systematic review of changes in mental health symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 54, 43–66 (2023).

Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M. & Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 296, 567–576 (2022).

Kauhanen, L. et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 32, 995–1013 (2023).

Wu, C., Qian, Y. & Wilkes, R. Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-white mental health gap during COVID-19. Ethn. Racial. Stud. 44, 819–835 (2021).

Foster, S., Estévez-Lamorte, N., Walitza, S. & Mohler-Kuo, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young adults’ mental health in Switzerland: A longitudinal cohort study from 2018 to 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 2598 (2023).

Schäfer, S. K., Kunzler, A. M., Kalisch, R., Tüscher, O. & Lieb, K. Trajectories of resilience and mental distress to global major disruptions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 1171–1189 (2022).

Van Damme, W. et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: Diverse contexts; Different epidemics—How and why? BMJ Glob. Health 5, (2020).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 31, 33–46 (2020).

Manwell, L. A. et al. What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey. BMJ Open 5, 007079 (2015).

Cleary, M., Walter, G. & Jackson, D. ‘Not always smooth sailing’: Mental health issues associated with the transition from high school to college. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 32, 250–254 (2011).

Fruehwirth, J. C., Mazzolenis, M. E., Pepper, M. A. & Perreira, K. M. Perceived stress, mental health symptoms, and deleterious behaviors during the transition to college. PLoS ONE 18, 0287735 (2023).

Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V. & Lam, M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Dev. 70, 1030–1044 (1999).

Shanahan, L. et al. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Med. 52, 824–833 (2022).

Bonanno, G. A., Chen, S., Bagrodia, R. & Galatzer-Levy, I. R. Annual review of psychology resilience and disaster: Flexible adaptation in the face of uncertain threat. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 75, 573–599 (2024).

Bonanno, G. A., Westphal, M. & Mancini, A. D. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 7, 511–535 (2011).

Gallagher, M. W. & Lopez, S. J. Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 548–556 (2009).

Narrow, W. E. et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part III: Development and reliability testing of a cross-cutting symptom assessment for DSM-5. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 71–82 (2013).

Whiting, K. & Wood, J. Two years of COVID-19: Key milestones in the pandemic. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/covid19-coronavirus-pandemic-two-years-milestones/ (2021).

Lee, Y. Y. et al. The risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Psychol. Med. 49, 92–102 (2019).

Lewinsohn, P. M., Solomon, A., Seeley, J. R. & Zeiss, A. Clinical implications of ‘subthreshold’ depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109, 345–351 (2000).

Ibonie, S. G. et al. Bipolar spectrum risk and social network dimensions in emerging adults: Two social sides?. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 44, 1–28 (2025).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess 49, 71–75 (1985).

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G. & Ickovics, J. R. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 19, 586–592 (2000).

Zion, S. R. et al. Making sense of a pandemic: Mindsets influence emotions, behaviors, health, and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 301, 114889 (2022).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. Preprint at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (2022).

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L. & Kam, C. M. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol. Methods 6, 330–351 (2001).

Little, R. J. A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 1198–1202 (1988).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Y. wrote the manuscript, and G.Y., I.M., and J.G. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafts of the manuscript. E.J., J.L., J.B., R.N., S.I., and C.V. made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data and study design as well as provided feedback on manuscript drafts.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, G., Mauss, I.B., Jopling, E. et al. A Multi-site, longitudinal investigation of emerging adult mental health across multiple stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 15, 42030 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22792-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22792-8