Abstract

Salmonella typhimurium, a leading cause of global foodborne illness, demands rapid, on-site detection to combat its widespread contamination in food supplies—where delayed diagnosis contributes to thousands of annual fatalities. Here, we present a novel colorimetric biosensing platform that exploits the intrinsic antimicrobial properties of silver ions (Ag+) to enable instrument-free, visual quantification of Salmonella typhimurium. The sensor relies on the controlled growth of gold@silver core–shell nanorods (Au@AgNRs), whose localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak undergoes a vivid, concentration-dependent color shift as silver shell deposition modulates their aspect ratio. In the absence of bacteria, Ag+ ions are reduced by ascorbic acid (AA) and uniformly coat AuNRs, inducing a blue shift. However, when Salmonella typhimurium is present, bacterial cells sequester Ag+ through interactions with surface biomolecules, inhibiting complete shell formation and resulting in a measurable red shift in the LSPR peak accompanied by visually discernible color transitions from red to magenta, purple, violet, dark blue, and teal. The system achieves a linear dynamic range of 18.75 × 106 to 112.5 × 106 CFU mL−1 and a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.0 × 106 CFU mL−1. Prior to detection, target bacteria are isolated from complex matrices using anti-Salmonella aptamer-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), ensuring specificity and minimizing matrix interference. Successful validation in spiked chicken bouillon samples (recovery: 93.3%, RSD: 3.5%) confirms practical utility under real-world conditions. This strategy uniquely merges microbiology with nanomaterials science, offering a low-cost, rapid, and visually interpretable solution for decentralized pathogen screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salmonella, a Gram-negative bacterium belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family, is among the most prevalent etiological agents of foodborne illness worldwide, with over 2,500 identified serotypes1. Human infections, collectively termed salmonellosis, typically manifest as acute gastroenteritis but can progress to life-threatening systemic conditions such as bacteremia and typhoid fever2. Transmission occurs primarily via the fecal–oral route3, including consumption of contaminated water4 or crops irrigated with wastewater. Alarmingly, Salmonella exhibits remarkable environmental persistence, particularly in low-moisture foods such as spices5, chocolate6, dried milk7, and peanut butter8, where it can survive for months. According to the World Health Organization, diarrheal diseases—for which Salmonella is a leading contributor—affect approximately 550 million people annually and result in nearly 42,000 deaths9,10. The infectious dose varies significantly depending on the bacterial strain, host susceptibility, and food matrix11, underscoring the need for sensitive, rapid, and field-deployable detection methods to mitigate outbreaks and reduce mortality.

Current detection approaches include traditional culture-based methods12, miniaturized biochemical assays13, immunoassays (e.g., ELISA14, latex agglutination15, nucleic acid amplification techniques (e.g., PCR16, hybridization17, CRISPR-based systems18, Raman spectroscopy19, phage-based detection20, biosensors21, and microfluidic platforms22. While effective in controlled settings, these methods often suffer from prolonged analysis times, high costs, requirement for specialized equipment or trained personnel, and limited suitability for on-site applications. To address these limitations, plasmonic nanoparticles—particularly gold (AuNPs) and silver (AgNPs)—have emerged as powerful transducers in colorimetric sensing due to their strong, tunable optical responses governed by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)23,24,25,26. LSPR arises from the collective oscillation of conduction electrons upon light excitation, resulting in intense light scattering and absorption in the visible spectrum27,28,29,30,31,32. Critically, the LSPR wavelength is exquisitely sensitive to nanoparticle size, shape, composition, and local dielectric environment33.

Among plasmonic nanostructures, gold nanorods (AuNRs) are particularly advantageous due to their dual LSPR peaks: a transverse mode (~ 520 nm) and a longitudinal mode that can be precisely tuned across the visible to near-infrared range by modulating the aspect ratio34,35. A reduction in aspect ratio—for instance, via conformal silver shell growth to form Au@Ag core–shell nanorods—induces a pronounced blue shift in the longitudinal peak36. This phenomenon has been leveraged for multicolor sensing applications37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Simultaneously, silver ions (Ag+) are well-established antimicrobial agents, exerting their effects through interactions with vital cellular components, including thiol-containing proteins, respiratory enzymes, and nucleic acids44,45,46. These interactions disrupt microbial metabolism, inhibit ATP synthesis, and induce oxidative stress. In this work, we introduce a novel sensing paradigm that strategically exploits this antimicrobial activity for analytical purposes.

For the first time, we demonstrate that Salmonella typhimurium can be detected by its ability to sequester Ag+ ions, thereby inhibiting the formation of Au@Ag core–shell nanorods. This “anti-formation” mechanism results in a concentration-dependent red shift of the LSPR peak, accompanied by visually discernible color transitions—from red to magenta, purple, violet, dark blue, and teal—enabling semi-quantitative, instrument-free readout (Fig. 1). Prior to detection, target bacteria are selectively captured from complex samples using commercially available anti-Salmonella aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), ensuring high specificity and compatibility with real-world matrices (Fig. 2). This approach represents a significant conceptual and practical advance: it transforms a biological defense mechanism into a quantifiable optical signal, eliminating the need for enzymatic amplification, antibody labeling, or sophisticated instrumentation. The result is a robust and user-friendly platform ideally suited for point-of-need applications in resource-limited settings.

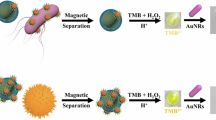

Schematic representation of the colorimetric sensing mechanism based on the inhibition of Au@Ag core-shell nanorod (Au@AgNR) formation by Salmonella typhimurium. (a) In the absence of bacteria, ascorbic acid (AA) reduces free silver ions (Ag+) to metallic silver (Ag0), which deposits uniformly around gold nanorods (AuNRs) to form complete Au@AgNRs. (b) In the presence of Salmonella, bacterial cells sequester free Ag+ ions via interactions with surface biomolecules, reducing their availability for reduction and thereby inhibiting the formation of a complete Ag shell on the AuNRs. This results in incomplete or thinner coatings. (c) This inhibition leads to a concentration-dependent increase in the aspect ratio of the resulting nanostructures, causing a red shift in the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak, as demonstrated by the spectral shift in the UV-Vis absorption profiles.

Schematic illustration of the two-step protocol for detecting Salmonella typhimurium using aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles and the designed colorimetric sensor. (a) Immunomagnetic separation: Aptamer-capped Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles selectively bind Salmonella cells from a complex sample containing other bacteria and matrix components. A magnet is used to isolate the nanoparticle-bacteria complexes, while unbound contaminants are removed by washing. (b) Colorimetric detection: Isolated Salmonella cells sequester silver ions (Ag+) via surface interactions. The residual, unbound Ag+ is then reduced by ascorbic acid (AA) in the presence of gold nanorods (AuNRs), leading to the formation of Au@Ag core-shell nanostructures. This process induces a concentration-dependent color shift (from red to teal) that can be visually interpreted without instrumentation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate(III) (HAuCl4.3H2O), 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (5-BrSA), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), ascorbic acid (AA), silver nitrate (AgNO3), 2-(n-morpholino) ethane sulfonic acid (MES), luciferase and luciferin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC 14028) was prepared from Iran Scientific-Industrial Research Center. All microbial culture media and components include tryptic soy broth (TSB), nutrient broth, peptone, and agar were purchased from Merck.

Instrumentation

A Lambda (PerkinElmer, USA) spectrophotometer was used for absorbance spectral recording at room temperature. To determine the size of the nanoparticles, a PHILIPS MC 10 TH microscope was used recording the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. The color images were captured using a Samsung Galaxy a73 smartphone.

Synthesis of AuNRs

Gold nanorods were synthesized through a previously reported seed-mediated approach with a few alterations47. Firstly, 0.125 mL of HAuCl4 (0.01 mol L− 1) and then, 0.30 mL of fresh NaBH4 (0.01 mol L− 1) were added to 4.7 mL of CTAB solution (0.10 mol L− 1) to prepare the seed solution. At this point, the tint of the solution started to change from yellow to brownish-yellow within a min. Afterward, the solution was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. To prepare AuNRs, 50 mg of 5-BrSA was added to 25.0 mL of 0.1 mol L− 1 CTAB solution and dissolved. Then, 480 µL of 0.01 mol L− 1 AgNO3 was mixed with the solution and mildly stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 25.0 mL of 0.001 mol L− 1 HAuCl4 solution was added to the mixture. After 120 min of pre-reduction, 130 µL of 0.1 mol L− 1 ascorbic acid solution was added under vigorous stirring. Eventually, 80 µL of the seed solution was injected into the growth solution and the stirring was stopped after 30 s. The mixture was left undisturbed at room temperature for at least 4 h to gradually change its color to brown. The synthesized AuNRs were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. After removing the supernatant, the AuNRs were redispersed in 0.05 mol L− 1 CTAB.

Bacterial culture

Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC 14028) was revived from stock by inoculating tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubating overnight at 37 °C. A single colony from the resulting culture was then transferred to fresh TSB and grown for 4 h at 37 °C to obtain mid-log phase cells. The optical density (OD₆₀₀) of the culture was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, and cultures with an OD₆₀₀ between 0.5 and 0.6 were selected for sensor experiments.

Sensing procedure

First, bacterial suspensions at varying concentrations were incubated with AgNO3 (final concentration: 300 µmol L−1) for 30 min to allow Salmonella typhimurium to sequester free Ag+ ions via surface interactions (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, this mixture was added to a reaction solution containing 0.15 mL of AuNRs, 10 mmol L−1 MES buffer (pH 7.0), and 200 µmol L−1 ascorbic acid, bringing the total volume to 1.0 mL. The mixture was vortexed vigorously to initiate the reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 and the subsequent growth of the silver shell on the AuNRs. After 60 min of incubation at room temperature, the resulting colorimetric response was quantified by recording UV–Vis absorbance spectra across the range of 400–800 nm.

All measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. AuNRs demonstrated optical stability for > 12 months when stored at 4 °C in CTAB solution. Commercial MNPs retained full functionality for > 6 months under refrigerated storage. Due to the irreversible nature of the silver reduction and shell growth reaction, each colorimetric assay is designed as a single-use, disposable format.

Real sample analysis

Anti-Salmonella magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) with a core–shell structure (Fe3O4/Au; diameter: 150 nm; saturation magnetization: 10.15 emu/g) were commercially obtained from Fanavar Zist Farma (FZF) Co., Iran. These MNPs were pre-conjugated with anti-Salmonella aptamers by the manufacturer and used directly without further modification to ensure reproducibility.

For pathogen isolation, food samples (25 g) were homogenized in 225 mL buffered peptone water and pre-enriched at 37 °C for 6–8 h. After centrifugation (3,000 × g, 10 min) to remove debris, the supernatant was incubated with 150 µL of MNP suspension per mL of sample under gentle rotation (25 rpm, 30 min, room temperature) to allow target binding. Magnetic separation was then performed using a permanent rack (5 min), followed by three washes with PBS (3 washes, pH 7.4) to eliminate non-specifically bound material (Fig. 2a).

Results and discussion

Principles of sensing

Ascorbic acid (AA, C₆H₈O₆) serves as a mild and effective reducing agent, capable of reducing silver ions (Ag+) to metallic silver (Ag0) through electron donation (Eq. 1). In the presence of gold nanorods (AuNRs), which act as nucleation sites, the reduced silver atoms preferentially deposit onto the AuNR surface, leading to the controlled formation of an Au@Ag core–shell nanostructure48. This shell growth modifies the surface composition, dimensions, and aspect ratio of the original AuNRs, thereby inducing a measurable shift in their localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) band.

In the present work, the synthesized AuNRs exhibited distinct transverse and longitudinal localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peaks at 525 nm and 760 nm, respectively (Fig. 3a). Upon addition of ascorbic acid (AA) and Ag+ ions, silver atoms were reduced and deposited onto the AuNR surface, forming gold@silver core–shell nanorods (Au@AgNRs). This shell growth increased the nanoparticle aspect ratio, resulting in a pronounced blue shift of the longitudinal LSPR peak (Fig. 3b, black spectrum). Crucially, when Salmonella typhimurium was present prior to shell formation, bacterial cells sequestered free Ag+ ions via interactions with surface biomolecules—thereby inhibiting the reduction and deposition of silver onto the AuNR surface. To exploit this phenomenon, we developed a two-solution sensing strategy: one containing Salmonella typhimurium pre-incubated with AgNO3(to allow ion sequestration), and the other containing AuNRs, MES buffer, and AA. Upon mixing, the residual unbound Ag+ was insufficient to support complete shell growth, leading to a measurable red shift in the LSPR peak (Fig. 3b, red spectrum) due to suppressed core-shell formation.

TEM images confirmed that Au@AgNRs formed in the absence of bacteria exhibited smaller aspect ratio (Fig. 3c), whereas those formed in the presence of Salmonella typhimurium retained a larger aspect ratio indicative of incomplete silver coating (Fig. 3d). These results validate our novel “anti-formation” mechanism—a unique enzyme-free strategy for colorimetric pathogen detection based on inhibition of nanoparticle growth.

(a) UV–Vis absorption spectrum of as-synthesized gold nanorods (AuNRs), showing transverse and longitudinal localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peaks at ~ 525 nm and ~ 760 nm, respectively. (b) Absorption spectra of the colorimetric sensor in the absence (black line, blank) and presence (red line) of Salmonella typhimurium. The presence of bacteria induces a red shift in the LSPR peak due to inhibition of silver shell formation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of Au@Ag nanostructures formed (c) in the absence of bacteria, showing Au@Ag NRs with uniform silver shells, and (d) in the presence of Salmonella typhimurium, revealing larger aspect ratio indicative of incomplete shell growth.

Regarding the interaction of silver ions with bacteria, research has revealed multiple mechanisms by which microorganisms respond to Ag+ exposure. In Gram-negative bacteria such as Salmonella spp., a primary defense strategy involves sequestering Ag+ ions within the periplasmic space, thereby preventing their entry into the cytoplasm and subsequent disruption of vital intracellular processes49. Additionally, some strains harbor plasmid-encoded resistance systems; for example, Salmonella typhimurium carries the pMG101 plasmid, which contains the sil gene cluster encoding nine proteins essential for active efflux and detoxification of silver ions50. Beyond these specific resistance mechanisms, Ag+ ions can directly interact with bacterial membranes, leading to inhibition of ATP synthesis, blockade of DNA replication, impairment of ribosomal function, and induction of reactive oxygen species51. Bragg and Rainnie demonstrated that Ag+ at concentrations as low as 15 µmol L−1 suppresses the oxidation of key metabolic substrates—glucose, glycerol, fumarate, succinate, and lactate—in E. coli, while also altering the composition and function of respiratory chain proteins52. Furthermore, Ag+ exhibits high affinity for functional groups in biomolecules, including thiol (-SH) moieties in proteins and nitrogenous bases in DNA, disrupting enzyme activity and genetic integrity45,53,54,55. In the context of this study, we propose that the antimicrobial action of Ag+ in our sensing system arises from its selective binding and accumulation within structural components of the Salmonella cell wall—potentially via interaction with purine-rich membrane channels or porins—thereby depleting free Ag+ available for reduction and shell formation on AuNRs (Fig. 3d).

Optimization of key sensing parameters

To improve the system’s stability and sensitivity, several crucial factors, i.e., silver nitrate concentration, ascorbic acid concentration, bacteria and silver mixture incubation time, and analysis time were optimized (Fig. 4). The analytical signal was defined as the wavelength shift (Δλ = λ – λ₀), where λ₀ is the longitudinal LSPR peak maximum in the absence of bacteria and λ is the peak maximum in its presence.

Optimization of key sensing parameters. (a) Effect of AgNO3concentration on sensor response (AuNR = 0.15 mL, AA = 200 µmol L−1, MES buffer = 50 mmol L−1). (b) Effect of ascorbic acid concentration on sensor response (AuNR = 0.15 mL, AgNO3= 300 µmol L−1, MES buffer = 50 mmol L−1, pH 7.0). (c) Influence of incubation time between Salmonella and Ag+ ions on sensor response (AuNR = 0.15 mL, AgNO3= 300 µmol L−1, AA = 200 µmol L−1, MES buffer = 10 mmol L−1, pH 7.0). (d) Time-dependent evolution of the sensor response after mixing components.

Effect of pH on sensor response

The reduction of silver ions (Ag+) by ascorbic acid (AA) and the subsequent deposition of metallic silver (Ag0) onto gold nanorods (AuNRs) are fundamentally pH-dependent processes, governed by both thermodynamic and kinetic principles. Simultaneously, the physiological state and surface chemistry of Salmonella typhimurium—the target analyte—are profoundly influenced by environmental pH. Therefore, selecting the right assay pH balances the kinetics of the plasmonic transduction with the biological integrity of the target pathogen.

The redox reaction between AA and Ag+ involves proton consumption (Eq. 1), implying that the reaction rate should theoretically increase under alkaline conditions according to Le Chatelier’s principle. Based on our preliminary investigations, at pH values above 7.0, we observed rapid, uncontrolled nucleation of Ag0 in solution, leading to the formation of spherical silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) alongside the desired conformal shell growth on AuNRs. This was evidenced by the emergence of a distinct, broad plasmon peak at ~ 400 nm in UV-Vis spectra, characteristic of free AgNPs. These nanoparticles contribute significant background absorption and scattering, obscuring the precise, aspect-ratio-dependent LSPR shift of the Au@AgNRs and drastically reducing the signal-to-noise ratio and reproducibility of the assay.

Conversely, at lower pH values, the reduction kinetics of Ag+ by AA become prohibitively slow. Even in the absence of bacteria, the formation of a complete, uniform silver shell required significantly longer incubation times (> 90 min) to reach optical equilibrium, making the assay impractical for rapid detection. Furthermore, suboptimal pH levels may induce physiological stress or alter the membrane permeability of Salmonella typhimurium. While Salmonella typhimurium thrives optimally near neutral pH (7.0–7.5), exposure to acidic conditions (pH < 6.5) can trigger its acid tolerance response (ATR), potentially upregulating efflux pumps or altering the expression and accessibility of key surface ligands involved in Ag+ sequestration, such as thiol-containing proteins and lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Such changes could artificially reduce the efficiency of Ag+ binding, leading to an underestimation of bacterial concentration and compromised sensitivity.

Therefore, pH 7.0 was rigorously established as the optimal condition. It enables the controlled formation of Au@AgNRs in the absence of bacteria, while simultaneously preserving the natural Ag+ sequestration capability of Salmonella typhimurium in its presence. This dual optimization ensures that the observed LSPR red shift is a direct, reliable, and physiologically relevant readout of bacterial load, minimizing artifacts and maximizing analytical fidelity. All subsequent experiments were conducted at this pH to ensure consistency, robustness, and biological relevance.

Optimization of Ag+ concentration

In our colorimetric sensing platform, the transduction mechanism relies on the controlled formation of Au@Ag core-shell nanorods (Au@AgNRs) via the reduction of Ag+ ions (from AgNO₃) by ascorbic acid (AA) on the surface of gold nanorods (AuNRs). In the absence of bacteria, this process proceeds homogeneously, leading to a uniform silver shell deposition. However, in the presence of Salmonella typhimurium, Ag+ ions are competitively sequestered by bacterial surface biomolecules—including thiol (-SH) groups in membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharides, and nucleic acids. This sequestration effectively reduces the concentration of free, reducible Ag+ ions available for shell formation on AuNRs. Consequently, the silver shell becomes thinner or discontinuous, preserving a higher aspect ratio in the resulting nanostructure and leading to red shift—compared to the bacteria-free control.

To rigorously optimize the Ag+ concentration for maximum sensor response, we systematically evaluated five concentrations of AgNO3 (150, 300, 450, 600, and 750 µmol L−1) under controlled conditions (Fig. 4a, Figure S1). At low Ag+ concentration (150 µmol L−1); the sensor response was suboptimal. The limited availability of Ag+ ions resulted in incomplete shell formation even in the absence of bacteria, yielding a smaller baseline LSPR shift. Consequently, the relative inhibition caused by bacterial sequestration was not in its maximum. At intermediate concentrations (300–450 µmol L−1); a significant and reproducible LSPR shift was observed in the absence of bacteria, indicating robust shell formation. In the presence of a fixed concentration of Salmonella typhimurium, a pronounced inhibition of this shift occurred, as bacterial cells effectively sequestered a substantial fraction of the available Ag+. Notably, the responses at 300 and 450 µmol L−1 were comparable (Figure S1b, c and Fig. 4a), suggesting that within this range, the system operates near its optimal sensitivity—where the amount of Ag+ is sufficient for full shell formation in the control, yet low enough that the bacterial biomass can meaningfully inhibit it. At high concentrations (> 450 µmol L−1, i.e., 600 and 750 µmol L−1); the sensor response decreased significantly. The excess Ag+ ions overwhelm the sequestration capacity of the bacterial cells. Even after bacterial binding, a large surplus of free Ag+ remains in solution, which is then reduced by AA to form a near-complete silver shell. This diminishes the spectral difference (Δλ) between the “bacteria-present” and “bacteria-absent” samples, thereby reducing the sensor’s sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio.

Although 300 and 450 µmol L−1 yielded similar absolute responses, 300 µmol L−1 was selected as the optimal concentration for the following refined reasons. (i) At 300 µmol L−1, the baseline shift (without bacteria) is sufficiently large for easy detection, while the relative inhibition by bacteria is maximized, leading to the highest contrast between negative and positive signals. (ii) A lower [Ag+] enables detection of lower bacterial concentrations—because even a small number of Salmonella typhimurium cells can sequester a significant fraction of the limited Ag+ pool, effectively inhibiting shell formation. This results in a lower limit of detection (LOD) and enhances sensitivity at low pathogen loads, which is critical for early-stage contamination screening. Conversely, higher Ag+ concentrations (e.g., 450 µmol L−1) require a much larger bacterial load to achieve comparable inhibition, reducing sensitivity and pushing the LOD upward. Therefore, selecting the minimal effective Ag+ concentration optimizes both sensitivity and practical utility for real-world applications.

Optimization of ascorbic acid concentration

Ascorbic acid (AA) serves as the mild, biocompatible reducing agent responsible for the controlled reduction of Ag+ ions to metallic silver (Ag0) on the surface of gold nanorods (AuNRs). The kinetics and spatial control of this reduction are critical. In the presence of Salmonella typhimurium, a fraction of Ag+ ions is sequestered by bacterial surface ligands (e.g., -SH, -NH₂, -PO₄³⁻), rendering them unavailable for reduction. Therefore, the concentration of AA must be carefully tuned to ensure that: (i) In the absence of bacteria, sufficient reducing power exists to drive complete, uniform Ag shell formation—yielding a large, reproducible LSPR blue shift. (ii) In the presence of bacteria, the reduction process remains sensitive to the decreased availability of free Ag+, resulting in a measurable inhibition of shell growth and a smaller LSPR shift. To achieve this balance, we evaluated five concentrations of AA (100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 µmol L−1) while keeping all other parameters constant (Fig. 4b, Figure S2).

At low AA concentration (100 µmol L−1); the reduction kinetics were slow to achieve complete shell formation within the reaction time—even in the absence of bacteria. This resulted in a small baseline LSPR shift and consequently, a weak analytical signal upon bacterial addition. The system was reduction-limited. At optimal concentration (200 µmol L−1); the reduction rate was perfectly matched to the experimental timeframe. A complete, uniform Ag shell formed in the absence of bacteria, yielding the maximum possible LSPR blue shift. In the presence of bacteria, sequestration of Ag+ significantly inhibited this process, leading to the largest differential signal—i.e., maximum sensor contrast. At high concentrations (≥ 400 µmol L−1); sensor performance degraded progressively. While the baseline LSPR shift (without bacteria) continued to increase slightly, the inhibited signal (with bacteria) decreased. This convergence of signals reduced the net analytical response. At [AA] ≥ 400 µmol L−1, nucleation of spherical Ag nanoparticles in solution becomes thermodynamically favorable. This is evident in Figure S2c-e by the emergence of a secondary, broad plasmon peak around ~ 400 nm—characteristic of spherical Ag nanoparticles. These free AgNPs contribute to background absorption, increase scattering, and reduce the specificity of the LSPR signal originating from Au@AgNRs.

Concentration 200 µmol L−1 was selected as the optimal concentration of AA because: (i) this concentration yielded the largest difference in LSPR shift between “with bacteria” and “without bacteria” conditions—the true measure of sensor sensitivity. (ii) At 200 µmol L−1, reduction is predominantly heterogeneous (surface-limited on AuNRs), as confirmed by the absence of a ~ 400 nm AgNP peak in Figure S2b. This ensures signal specificity and minimizes background noise.

Optimization of Ag+–bacteria incubation time

The incubation time between Salmonella typhimurium cells and silver ions (Ag+) is a critical kinetic parameter that governs the efficiency of Ag+ sequestration by bacterial surface biomolecules. As outlined in Sect. 3.1, Ag+ ions interact with multiple cellular targets—including thiol (-SH) groups in membrane proteins, phosphate moieties in lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and nitrogenous bases in exposed DNA—leading to their immobilization within the bacterial envelope. These interactions are not instantaneous; they require sufficient contact time for diffusion, binding, and internalization (or surface complexation) to occur.

To systematically evaluate the impact of incubation duration on sensor performance, we tested five time intervals: 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 min (Figure S3). The sensor response, defined as Δλ = λ (with bacteria) – λ₀ (without bacteria), exhibited a clear positive correlation with incubation time. This trend is mechanistically intuitive: longer incubation allows more Ag+ ions to interact with a greater number of bacterial binding sites, thereby reducing the pool of free Ag+ available for subsequent reduction and deposition onto AuNRs. Consequently, the inhibition of core–shell formation becomes more pronounced, resulting in a larger red shift in the LSPR peak—and thus a stronger analytical signal. However, the incremental gain in sensor response diminished significantly beyond 30 min. As shown in Fig. 4c, the difference in Δλ between 30 and 40 min was statistically negligible, indicating that the system approaches equilibrium within this timeframe. At 30 min, the majority of accessible binding sites on the bacterial surface are saturated, and further extension of incubation yields minimal additional sequestration. Therefore, 30 min was selected as the optimal incubation time. This choice represents a scientifically justified compromise: it ensures near-maximal Ag+ sequestration (and thus maximal sensor sensitivity) while avoiding unnecessary prolongation of the assay.

Optimization of reaction analysis time

Following the incubation and mixing of all components—AuNRs, residual Ag+, ascorbic acid (AA), and MES buffer—the transduction phase of the assay commences: the controlled reduction of free Ag+ ions and their deposition as a metallic silver shell onto the surface of AuNRs. This heterogeneous nucleation and growth process directly modulates the aspect ratio of the nanorods, inducing a visually observable color transition. To ensure that spectral measurements are taken at the point of maximum signal differentiation, we monitored the evolution of the LSPR peak shift over one hour, recording absorbance spectra every 2 min under optimized conditions.

The results, presented in Fig. 4d, reveal that the LSPR shift (Δλ) increases progressively over time, reaching a plateau at approximately 60 min. This plateau signifies the completion of the silver shell formation process: all available free Ag+ has been reduced and deposited, and the nanostructure’s optical properties have stabilized. Measurements taken before 60 min would capture the system in a transient, kinetically controlled state, leading to underestimation of the true analytical signal and poor reproducibility. Conversely, measurements taken beyond 60 min offer no analytical benefit, as the signal remains constant while unnecessarily extending the total assay time. Thus, 60 min was established as the optimal analysis time. This duration guarantees that the system has reached thermodynamic and optical equilibrium, ensuring maximum signal stability, reproducibility, and sensitivity. It also aligns with practical constraints, enabling a total assay time (including incubation and analysis) of approximately 90 min—a highly competitive timeframe for an instrument-free colorimetric biosensor.

Calibration and visual response of the sensor to Salmonella typhimurium. (a) UV–Vis absorption spectra showing progressive red shifts in the longitudinal LSPR peak with increasing bacterial concentrations (18.75 × 106 to 112.5 × 106 CFU mL−1), demonstrating inhibition of Au@AgNR shell formation. (b) Linear calibration curve correlating the LSPR peak shift (Δλ = λ – λ₀) with bacterial concentration (CFU mL−1; R² = 0.997). (c) Representative color changes observed visually under optimized conditions, ranging from orange-red to teal as bacterial load increases.

Quantitative performance

To establish the quantitative performance of the sensor, a series of Salmonella typhimurium suspensions at known concentrations were analyzed using the optimized sensing protocol. UV–Vis spectrophotometry revealed a progressive red shift in the longitudinal LSPR peak with increasing bacterial concentration, directly reflecting the dose-dependent inhibition of Ag shell formation on AuNRs (Fig. 5a). A linear calibration curve was constructed by plotting the LSPR peak shift (Δλ = λ – λ₀) against bacterial concentration (CFU mL−1), yielding the equation: Y = 0.45X + 108 (R² = 0.997), where Y is the wavelength shift (nm) and X is the bacterial concentration (×106 CFU mL−1) (Fig. 5b). The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated using the standard formula LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of ten blank measurements (no bacteria) and S is the slope of the calibration curve, resulting in an LOD of 2.0 × 106 CFU mL−1. Critically, this quantitative spectral shift corresponds to distinct, naked-eye-visible color transitions—from orange-red through magenta, purple, and violet to teal—as bacterial concentration increases, enabling intuitive, instrument-free detection (Fig. 5c).

Application in complex matrices

To evaluate the sensor’s performance in complex real-world matrices, Salmonella typhimurium was detected in spiked samples of both chicken bouillon and tap water. The chicken bouillon matrix was prepared by dissolving a commercial bouillon cube in hot water, followed by filtration through qualitative filter paper to remove insoluble particulates; tap water served as a low-complexity aqueous control. A known concentration of purified Salmonella typhimurium suspension was then added to each clarified matrix to achieve targeted spiking levels. After processing all samples through the full detection protocol—including immunomagnetic separation and colorimetric analysis—the recovery rates and relative standard deviations (RSD) were calculated to assess accuracy and precision. As summarized in Table 1, the system achieved recoveries of 93.3% (chicken bouillon) and 96.0% (tap water), with RSD values of 3.5% and 2.5%, respectively, demonstrating robust applicability, reliability, and minimal matrix interference under practical conditions.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive comparison of our sensor with previously reported plasmonic and magnetic nanoparticle-based colorimetric platforms for Salmonella detection. While our LOD is higher than enzyme-amplified or PCR-coupled methods56, it is fully competitive—and in some cases superior—to other label-free, enzyme-free, visual-readout plasmonic sensors. Notably, our LOD is 3.3× lower than the aptamer-based AuNP aggregation sensor57, 1.5× lower than the commercial lateral flow assay format58—despite our system being completely enzyme-free and requiring no gold nanoparticle surface modification. Unlike the highly sensitive surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor59—which achieves a low LOD of 7.4 × 10³ CFU mL−1 through complex immobilization on functionalized chips and requires expensive optical instrumentation—our platform achieves acceptable sensitivity within a vastly simpler, instrument-free framework.

Beyond analytical performance, our platform offers distinct practical advantages as follows: (1) Low cost per test (~ 1.0–3.0 USD); our sensor is among the most cost-effective plasmonic platforms, leveraging inexpensive, unmodified AuNRs and common reagents—unlike antibody-conjugated systems56,58 or enzymatic assays60,61 that incur high reagent costs. (2) True visual readout with rainbow-like color transitions; Unlike most colorimetric assays that rely on binary red-to-blue shifts57,58, our sensor produces a concentration-dependent spectral gradient (red → magenta → purple → violet → dark blue → teal), enabling semi-quantitative naked-eye estimation without instrumentation. (3) Minimal sample preparation complexity; While pre-enrichment is standard for all culture-compatible methods, our integrated magnetic separation using aptamer-MNPs streamlines sample-to-answer workflow—eliminating the need for antibody conjugation, enzymatic labeling, or nucleic acid extraction.

Within this framework, our platform’s combination of low cost, visual readout, instrument-free operation, and compatibility with standard microbiological practice makes it uniquely suited for decentralized screening in resource-limited settings—where complex instrumentation, trained personnel, or expensive reagents are unavailable.

Mechanistic basis of detection

Building upon the observed inhibition of Au@AgNR formation described in Sect. 3.1, we now dissect the molecular basis of this phenomenon to establish its validity as a specific recognition event. The core innovation of this work lies in transforming the innate biochemical interaction between Salmonella typhimurium and silver ions (Ag+)—a phenomenon well-documented in microbial toxicology—into a quantifiable, visually interpretable optical signal. Unlike conventional biosensors that rely on antibody–antigen binding, aptamer hybridization, or enzymatic amplification, our platform exploits the passive, non-specific, yet highly reproducible adsorption and internalization of Ag+ by bacterial surface biomolecules. This interaction serves as the primary recognition event, functionally replacing traditional biorecognition elements and enabling a label-free, enzyme-free detection paradigm. To elucidate the molecular underpinnings of this “anti-formation” mechanism, we systematically dissect three critical stages: (i) the sequestration of Ag+ by bacterial surface components, (ii) the quantitative inhibition of Au@Ag nanorod shell growth, and (iii) the role of magnetic pre-enrichment in conferring operational specificity.

Ag+ sequestration by bacterial surface biomolecules

Upon exposure to AgNO₃, Salmonella typhimurium rapidly binds and internalizes silver ions through multivalent interactions with structurally abundant ligands on its Gram-negative envelope. The outer membrane, peptidoglycan layer, and periplasmic space are enriched with functional groups possessing high affinity for Ag+. Thiol (–SH) groups in membrane proteins (e.g., thioredoxin, peroxiredoxins) and low-molecular-weight thiols (e.g., glutathione) form exceptionally stable linear Ag–S bonds, effectively immobilizing Ag+ at the cell surface and within the periplasm45. Simultaneously, nitrogenous bases—particularly purines (adenine, guanine) and pyrimidines—in exposed extracellular DNA fragments, RNA, or nucleotide-binding domains coordinate with Ag+ via N–Ag Lewis acid-base interactions, as validated in prior studies of Ag–DNA complexation52,53,54. Carboxylate (–COO⁻) groups from lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and amine (–NH₂) groups in peptidoglycan subunits further contribute to ion trapping through electrostatic and coordination bonding44,51. Crucially, these interactions are not merely superficial; Ag+ penetrates the porous peptidoglycan meshwork and accumulates in the periplasm, where it disrupts respiratory chain complexes (e.g., cytochrome oxidases) by displacing essential metal cofactors, inhibits ATP synthase by binding to proton channels, and induces oxidative stress by catalyzing Fenton-like reactions.

This multi-target sequestration depletes the free Ag+ pool in solution in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, as confirmed by our optimization data (Fig. 4c, S3). Critically, this depletion is the triggering event for our sensing mechanism: the more Ag+ is sequestered, the less remains available to be reduced and deposited onto AuNRs. We validated this directly using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), which demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in supernatant Ag+ concentration after bacterial incubation—providing unequivocal evidence that Salmonella acts as a biological sink for silver ions.

Quantifiable Inhibition of core–shell formation

In the absence of bacteria, ascorbic acid (AA) reduces Ag+ ions homogeneously in solution, and the resulting Ag0 atoms nucleate and grow epitaxially along the longitudinal axis of the AuNRs, forming a smooth, continuous, and conformal silver shell. This process increases the nanoparticle’s overall diameter thereby reducing its aspect ratio—a geometric change that induces a large, reproducible blue shift (~ 100–150 nm) in the longitudinal LSPR peak (Fig. 3b, black spectrum). However, in the presence of Salmonella, the sequestered Ag+ is no longer bioavailable for reduction. Consequently, the amount of Ag0 generated during the 60-minute growth period is insufficient to fully coat the AuNRs. This leads to three interrelated outcomes: (i) Silver deposition becomes spatially heterogeneous, forming patchy, discontinuous, or island-like structures rather than a uniform shell; (ii) The underlying AuNR core retains a larger effective aspect ratio because its original dimensions are less masked by the incomplete silver overgrowth; and (iii) The resulting nanostructures exhibit a smaller degree of plasmonic coupling along their long axis, manifesting as a measurable red shift in the LSPR peak relative to the control (Fig. 3b, red spectrum). This red shift is not an artifact but a direct, proportional readout of the extent of Ag+ sequestration: higher bacterial concentrations lead to greater Ag+ depletion, more incomplete shells, and thus larger red shifts.

TEM imaging provides definitive structural confirmation: control samples show thick, uniform silver shells enveloping elongated rods (Fig. 3c), whereas samples with bacteria reveal thinner coatings with visible AuNR cores exposed (Fig. 3d). This “incomplete growth” phenomenon is the central transduction mechanism—it converts a biochemical event (ion binding) into a physical nanoscale modification (aspect ratio change) that is optically amplified and visually discernible.

Magnetic pre-enrichment enables operational specificity

While Ag+ sequestration by bacterial surfaces is a general phenomenon observed across many Gram-negative species, our sensor achieves operational specificity for Salmonella typhimurium through an integrated, pre-analytical enrichment step: immunomagnetic separation using anti-Salmonella aptamer-conjugated Au/Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs). This step ensures that only target cells—captured via high-affinity aptamer binding to Salmonella-specific surface antigens—are present during the critical Ag+ incubation phase. Background microbiota (e.g., E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes) and matrix components (e.g., proteins, fats, particulates from chicken bouillon) are efficiently removed during magnetic washing, preventing them from contributing to non-specific Ag+ binding or optical interference.

To rigorously quantify this selectivity, we evaluated the recovery efficiency of the MNP-based capture protocol against a panel of common foodborne pathogens. Equal suspensions (1000 CFU mL− 1) of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes were subjected to the same magnetic capture protocol optimized for Salmonella typhimurium. As shown in Table 3, the MNPs achieved a recovery rate of 85 ± 3% for Salmonella typhimurium, while exhibiting minimal cross-reactivity: 7 ± 1% for E. coli, 4 ± 1% for Staphylococcus aureus, and 3 ± 1% for Listeria monocytogenes. When normalized to Salmonella recovery (set at 100%), the relative responses were 8%, 5%, and 4%, respectively. These results demonstrate exceptional target specificity (> 90% discrimination over non-target species), confirming that the observed LSPR red shift originates exclusively from captured Salmonella cells and not from background flora or matrix interferents.

The near-complete absence of cross-reactivity validates that the sensor’s specificity is conferred by the molecular recognition of aptamer–antigen interactions, not by inherent chemical affinity of Ag+ for other bacteria. Thus, the magnetic pre-enrichment does not merely improve sensitivity; it transforms a non-specific biochemical interaction (Ag+ binding) into a highly specific analytical signal by ensuring that the observed LSPR response is attributable solely to the target pathogen. This integration of sample preparation and detection chemistry represents a paradigm shift: the sensor’s specificity is engineered into the workflow itself, not the nanomaterial surface, making the platform robust, scalable, and suitable for real-world deployment.

Conclusion

In summary, we presented a novel colorimetric sensor for Salmonella typhimurium that repurposes the bacterium’s innate Ag+ sequestration ability into a visual detection signal. By inhibiting the conformal growth of a silver shell on gold nanorods, bacterial presence induces a concentration-dependent red shift in the LSPR peak—accompanied by a vivid, naked-eye-distinguishable rainbow transition—enabling instrument-free, semi-quantitative detection. The platform achieves a limit of detection of 2.0 × 106 CFU mL−1 and a linear range of 18.75–112.5 × 106 CFU mL−1, outperforming many existing enzyme-free plasmonic sensors and rivaling commercial lateral flow assays—all without antibody conjugation or enzymatic amplification.

Crucially, integration with aptamer-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles enables specific capture from complex matrices (e.g., chicken bouillon), yielding > 93% recovery and minimal interference. This pre-enrichment step aligns with regulatory workflows (ISO/FDA) and is not a limitation, but a strategic advantage ensuring real-world applicability. With an estimated cost of $1–3 per test and no need for specialized equipment, our sensor offers unprecedented accessibility for decentralized screening in low-resource settings. It transforms a microbial defense mechanism into a simple, scalable diagnostic tool. While further reduction of the LOD remains a valuable objective for our future work, the current performance, robustness, and simplicity position this platform as a highly viable solution for immediate deployment in field-based food safety and public health screening programs.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ehuwa, O., Jaiswal, A. K. & Jaiswal, S. Salmonella, food safety and food handling practices. Foods 10, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10050907 (2021).

Eng, S. K. et al. Salmonella: A review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front. Life Sci. 8, 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/21553769.2015.1051243 (2015).

Guerrero, T., Calderón, D., Zapata, S. & Trueba, G. Salmonella grows massively and aerobically in chicken faecal matter. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 1678–1684. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13624 (2020).

Santiago, P. et al. High prevalence of Salmonella and Enterococcus faecium spp. In wastewater reused for irrigation assessed by molecular methods. Int. J. Hyg. Environ Health. 221, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.007 (2018).

Xie, Y. et al. Survivability of Salmonella and Enterococcus faecium in chili, cinnamon and black pepper powders during storage and isothermal treatments. Food Control. 137, 108935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108935 (2022).

Sun, S. et al. Survival and thermal resistance of Salmonella in chocolate products with different water activities. Food Res. Int. 172, 113209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113209 (2023).

Sekhon, A. S. et al. Survival and thermal resistance of Salmonella in dry and hydrated nonfat dry milk and whole milk powder during extended storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 337, 108950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108950 (2021).

Sithole, T. R., Ma, Y. X., Qin, Z., Wang, X. D. & Liu, H. M. Peanut butter food safety concerns—Prevalence, mitigation and control of Salmonella spp., and aflatoxins in peanut butter. Foods 11, 1874. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11131874 (2022).

Organization, W. H. Salmonella (non-typhoidal), (2018).

Tokunaga, Y., Wakabayashi, Y., Yonogi, S. & Yamaguchi, N. Rapid quantification of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella typhimurium in lettuce using immunomagnetic separation and a microfluidic system. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 47, 1931–1936. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b24-00352 (2024).

Konstantinou, L. et al. A Novel Application of B. EL. D™ Technology: Biosensor-based detection of Salmonella spp. in Food. Biosensors 14, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios14120582 (2024).

Van der Zee, H. Conventional methods for the detection and isolation of Salmonella enteritidis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 21, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1605(94)90198-8 (1994).

Lee, K. M., Runyon, M., Herrman, T. J., Phillips, R. & Hsieh, J. Review of Salmonella detection and identification methods: Aspects of rapid emergency response and food safety. Food Control. 47, 264–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.07.011 (2015).

Di Febo, T. et al. Development of a capture ELISA for rapid detection of Salmonella enterica in food samples. Food. Anal. Methods. 12, 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-018-1363-2 (2019).

Rastawicki, W., Formińska, K. & Zasada, A. A. Development and evaluation of a latex agglutination test for the identification of Francisella tularensis subspecies pathogenic for human. Pol. J. Microbiol. 67, 241. https://doi.org/10.21307/pjm-2018-030 (2018).

Kasturi, K. N. & Drgon, T. Real-time PCR method for detection of Salmonella spp. In environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00644–e00617. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00644-17 (2017).

Yu, S. et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella in milk based on hybridization chain reaction and graphene oxide fluorescence platform. J. Dairy Sci. 104, 12295–12302. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20713 (2021).

Cai, Q. et al. Sensitive detection of Salmonella based on CRISPR-Cas12a and the tetrahedral DNA nanostructure-mediated hyperbranched hybridization chain reaction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 16382–16389. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c05831 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Rapid identification of Salmonella serovars by using Raman spectroscopy and machine learning algorithm. Talanta 253, 123807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123807 (2023).

Phothaworn, P., Meethai, C., Sirisarn, W. & Nale, J. Y. Efficiency of bacteriophage-based detection methods for non-Typhoidal Salmonella in foods: A systematic review. Viruses 16, 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16121840 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. An overview of rapid detection methods for Salmonella. Food Control 110771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2024.110771 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. A microfluidic biosensor for quantitative detection of Salmonella in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Biosensors 15, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15010010 (2024).

Putri, L. A. et al. Review of noble metal nanoparticle-based colorimetric sensors for food safety monitoring. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 19821–19853. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.4c04327 (2024).

Tang, L. & Li, J. Plasmon-based colorimetric nanosensors for ultrasensitive molecular diagnostics. ACS Sens. 2, 857–875. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.7b00282 (2017).

Ghasemi, F., Abbasi-Moayed, S., Ivrigh, Z. J. N. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. in Gold and Silver Nanoparticles (eds Suban Sahoo & M. Reza Hormozi-Nezhad) 165–204 (Elsevier, 2023).

Koushkestani, M., Ghasemi, F. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. Ratiometric dual-mode optical sensor array for the identification and differentiation of pesticides in vegetables with mixed plasmonic and fluorescent nanostructures. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 2764–2774. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c04982 (2024).

Olson, J. et al. Optical characterization of single plasmonic nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CS00131A (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Recent advances of plasmonic nanoparticles and their applications. Materials 11, 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11101833 (2018).

Taefi, Z., Ghasemi, F. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. Selective colorimetric detection of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) using arginine-mediated aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 228, 117803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2019.117803 (2020).

Mohammadi, A., Ghasemi, F. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. Development of a paper-based plasmonic test strip for visual detection of methiocarb insecticide. IEEE Sens. J. 17, 6044–6049. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2017.2731418 (2017).

Sepahvand, M., Ghasemi, F. & Hosseini, H. M. S. Thiol-mediated etching of gold nanorods as a neoteric strategy for room-temperature and multicolor detection of nitrite and nitrate. Anal. Methods. 13, 4370–4378. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1AY01117K (2021).

Abdali, M., Ghasemi, F., Hosseini, S., Mahdavi, V. & H. M. & Different sized gold nanoparticles for array-based sensing of pesticides and its application for strawberry pollution monitoring. Talanta 267, 125121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2023.125121 (2024).

Hemmati, M., Selakjan, A. H. Q. & Ghasemi, F. Iron (III) edta-accelerated growth of gold/silver core/shell nanoparticles for wide-range colorimetric detection of hydrogen peroxide. Sci. Rep. 15, 4050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88342-4 (2025).

Chen, J., Jackson, A. A., Rotello, V. M. & Nugen, S. R. Colorimetric detection of Escherichia coli based on the enzyme-induced metallization of gold nanorods. Small 12, 2469–2475. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201503682 (2016).

Zhao, P., Li, N. & Astruc, D. State of the Art in gold nanoparticle synthesis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 638–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.002 (2013).

Sahu, A. K., Das, A., Ghosh, A. & Raj, S. Understanding blue shift of the longitudinal surface plasmon resonance during growth of gold nanorods. Nano Express. 2, 010009. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.06365 (2021).

Awiaz, G., Lin, J. & Wu, A. Recent advances of Au@Ag core–shell SERS-based biosensors. Exploration 3, 20220072. https://doi.org/10.1002/EXP.20220072 (2023).

Lu, L., Burkey, G., Halaciuga, I. & Goia, D. V. Core–shell gold/silver nanoparticles: Synthesis and optical properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 392, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2012.09.057 (2013).

Ghorbanian, E., Ghasemi, F., Tavabe, K. R. & Sabet, H. R. A. Formation of plasmonic core/shell nanorods through ammonia-mediated dissolution of silver (I) oxide for ammonia monitoring. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 3229–3238. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NA00216D (2024).

Naseri, A. & Ghasemi, F. Analyte-restrained silver coating of gold nanostructures: an efficient strategy to advance multicolorimetric probes. Nanotechnology 33, 075501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ac3704 (2021).

Orouji, A., Ghasemi, F. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. Machine learning-assisted colorimetric assay based on Au@ ag nanorods for chromium speciation. Anal. Chem. 95, 10110–10118. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c01904 (2023).

Shirzad, M., Anbarestani, M. & Ghasemi, F. Ion-mediated etching of Au–Ag core-shell nanorods for LSPR-based discrimination of hazardous ions. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1357, 344066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2025.344066 (2025).

Sepahvand, M. & Ghasemi, F. Colorimetric silver ion detection based on silver metallization of gold nanorods. ChemistrySelect 9 (e202400080). https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202400080 (2024).

Slawson, R., Lee, H. & Trevors, J. Bacterial interactions with silver. Biology Met. 3, 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01140573 (1990).

Jung, W. K. et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of the silver ion in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2171–2178. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02001-07 (2008).

Hamad, A., Khashan, K. S. & Hadi, A. Silver nanoparticles and silver ions as potential antibacterial agents. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 30, 4811–4828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-020-01744-x (2020).

Scarabelli, L., Grzelczak, M. & Liz-Marzán, L. M. Tuning gold Nanorod synthesis through prereduction with Salicylic acid. Chem. Mater. 25, 4232–4238. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm402177b (2013).

Miryousefi, N., Varmazyad, M. & Ghasemi, F. Synthesis of Au@Ag core-shell nanorods with tunable optical properties. Nanotechnology 35, 395605. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ad572b (2024).

Randall, C. P., Gupta, A., Jackson, N., Busse, D. & O’Neill, A. J. Silver resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: a dissection of endogenous and exogenous mechanisms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1037–1046. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dku523 (2015).

Terzioğlu, E., Arslan, M., Balaban, B. G. & Çakar, Z. P. Microbial silver resistance mechanisms: recent developments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38, 158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-022-03341-1 (2022).

Rieger, K. A., Cho, H. J., Yeung, H. F., Fan, W. & Schiffman, J. D. Antimicrobial activity of silver ions released from zeolites immobilized on cellulose nanofiber Mats. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 3032–3040. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b10130 (2016).

Bragg, P. & Rainnie, D. The effect of silver ions on the respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 20, 883–889. https://doi.org/10.1139/m74-135 (1974).

Furr, J. R., Russell, A., Turner, T. & Andrews, A. Antibacterial activity of actisorb Plus, actisorb and silver nitrate. J. Hosp. Infect. 27, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6701(94)90128-7 (1994).

Yakabe, Y., Sano, T., Ushio, H. & Yasunaga, T. Kinetic studies of the interaction between silver ion and deoxyribonucleic acid. Chem. Lett. 9, 373–376. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.1980.373 (1980).

Gruen, L. C. Interaction of amino acids with silver (I) ions. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Protein Struct. 386, 270–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2795(75)90268-8 (1975).

Wu, W. et al. Gold nanoparticle-based enzyme-linked antibody-aptamer sandwich assay for detection of Salmonella typhimurium. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 16974–16981. https://doi.org/10.1021/am5045828 (2014).

Du, J. et al. A low pH-based rapid and direct colorimetric sensing of bacteria using unmodified gold nanoparticles. J. Microbiol. Methods. 180, 106110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2020.106110 (2021).

Yahaya, M. L., Zakaria, N. D., Noordin, R. & Abdul Razak, K. Development of rapid gold nanoparticles based lateral flow assays for simultaneous detection of Shigella and Salmonella genera. Biotechnol. Appl. Chem. 68, 1095–1106. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2029 (2021).

Vaisocherová-Lísalová, H. et al. Low-fouling surface plasmon resonance biosensor for multi-step detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens in complex food samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 80, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2016.01.040 (2016).

Daramola, O. B., Torimiro, N. & George, R. C. Colorimetric-based detection of enteric bacterial pathogens using chromogens-functionalized iron oxide-gold nanocomposites biosynthesized by Bacillus subtilis. Discover Biotechnol. 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44340-025-00008-z (2025).

Park, J. Y., Jeong, H. Y., Kim, M. I. & Park, T. J. Colorimetric detection system for Salmonella typhimurium based on peroxidase-like activity of magnetic nanoparticles with DNA aptamers. J. Nanomater. 527126 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/527126 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.: Investigation, Methodology; A.H.Q.S: Validation, Writing – original draft, F.G.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing; E.S.: Resources, Validation, Writing – review and editing; P.K.Z.: Investigation; M.A.: Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soleimani, S., Selakjan, A.H.Q., Ghasemi, F. et al. Exploiting silver ions’ antimicrobial properties for colorimetric detection of Salmonella via suppressed formation of Au@Ag nanorods. Sci Rep 15, 39237 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22852-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22852-z